Abstract

Photo-induced toxicity of petroleum products and polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) is the enhanced toxicity caused by their interaction with ultraviolet radiation and occurs by two distinct mechanisms: photosensitization and photomodification. Laboratory approaches for designing, conducting, and reporting of photo-induced toxicity studies are reviewed and recommended to enhance the original Chemical Response to Oil Spills: Ecological Research Forum (CROSERF) protocols which did not address photo-induced toxicity. Guidance is provided on conducting photo-induced toxicity tests, including test species, endpoints, experimental design and dosing, light sources, irradiance measurement, chemical characterization, and data reporting. Because of distinct mechanisms, aspects of photosensitization (change in compound energy state) and photomodification (change in compound structure) are addressed separately, and practical applications in laboratory and field studies and advances in predictive modeling are discussed. One goal for developing standardized testing protocols is to support lab-to-field extrapolations, which in the case of petroleum substances often requires a modeling framework to account for differential physicochemical properties of the constituents. Recommendations are provided to promote greater standardization of laboratory studies on photo-induced toxicity, thus facilitating comparisons across studies and generating data needed to improve models used in oil spill science.

1. Introduction

The original focus of the Chemical Response to Oil Spills: Ecological Research Forum (CROSERF) (see Loughery et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2023) was to standardize methods to allow greater comparability of dispersants and dispersed oil toxicity data (Aurand and Coelho, 2005). Photo-induced toxicity was not a factor addressed by CROSERF because at the time, the potential effects of sunlight exposure were considered limited under field situations. Subsequent calls for improving existing protocols (see Barron and Ka’aihue, 2003) alongside a growing body of scientific knowledge (Alloy et al., 2016, 2017; Barron et al., 2008, 2017; Finch et al., 2016, 2017; Finch and Stubblefield, 2016; Niles et al., 2019; Ward and Overton, 2020; Zito et al., 2020; Freeman and Ward, 2022) have highlighted the importance of addressing photo-induced toxicity as a component of oil spill hazard and risk assessment. The primary objective of this article is to promote greater standardization of laboratory studies on photo-induced toxicity, thus facilitating comparisons across studies and generating data needed to improve models used in oil spill science.

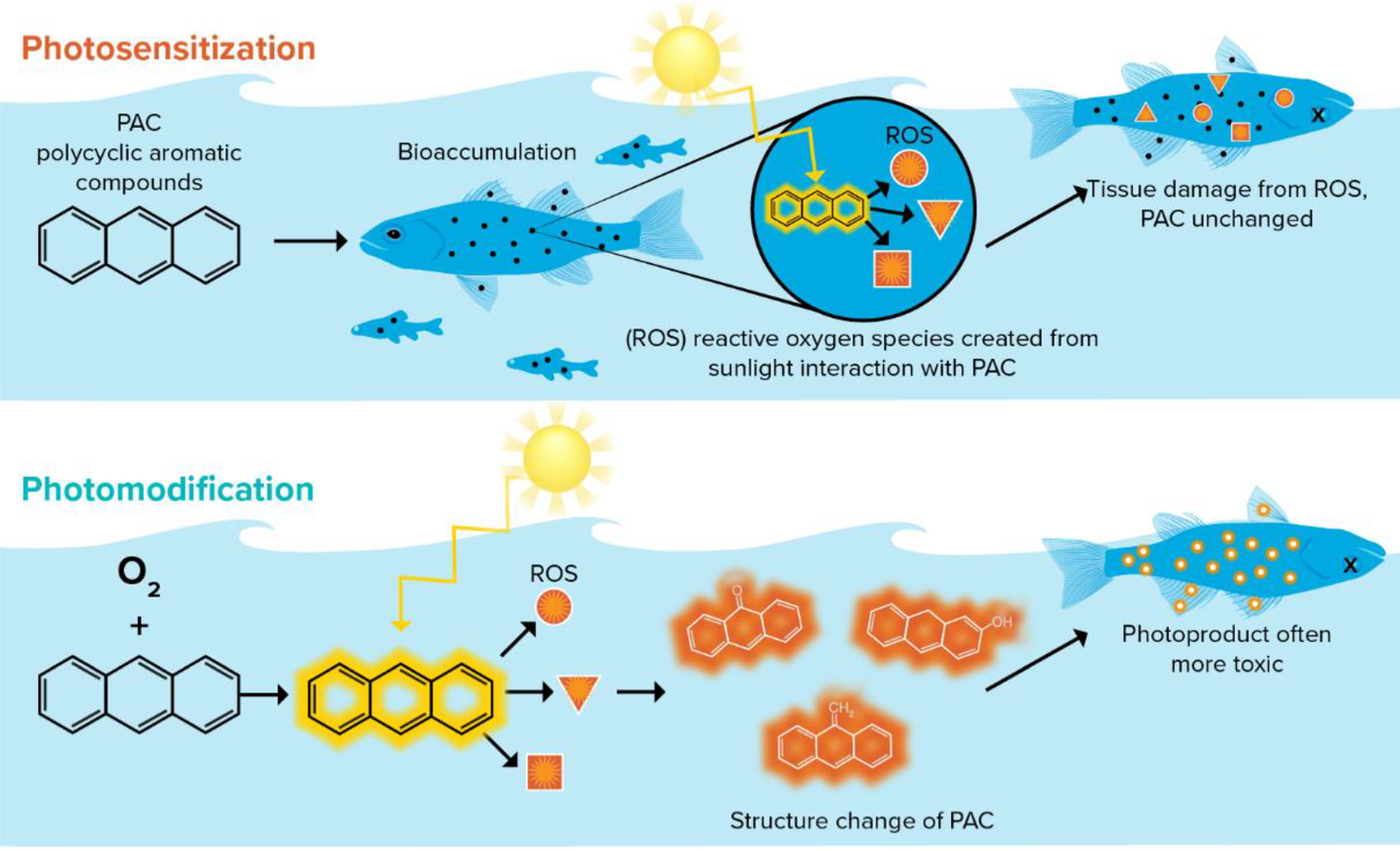

Photo-induced toxicity is the product of an interaction between solar irradiation and compounds that can either act as a photosensitizer or be photomodified. Photo-induced toxicity occurs by two distinct mechanisms, referred to as photosensitization and photomodification, that differ in the sequence of exposure to solar irradiation and phototoxic compounds that changes in molecular structure or energy state (NRC, 2003, 2005; Barron, 2007; Barron, 2017; Roberts et al., 2017); a conceptual diagram is given in Fig. 1. In both mechanisms, photochemical effects require the absorption of light energy. Many classes of compounds absorb light; however, the focus of this article is only on petroleum substances and petroleum components such as polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual diagram of photo-induced toxicity mechanisms using the polycyclic aromatic compound (PAC) anthracene as the example petroleum compound. Photosensitization (top) occurs separate from the organism, and photomodification (bottom) occurs within the organism.

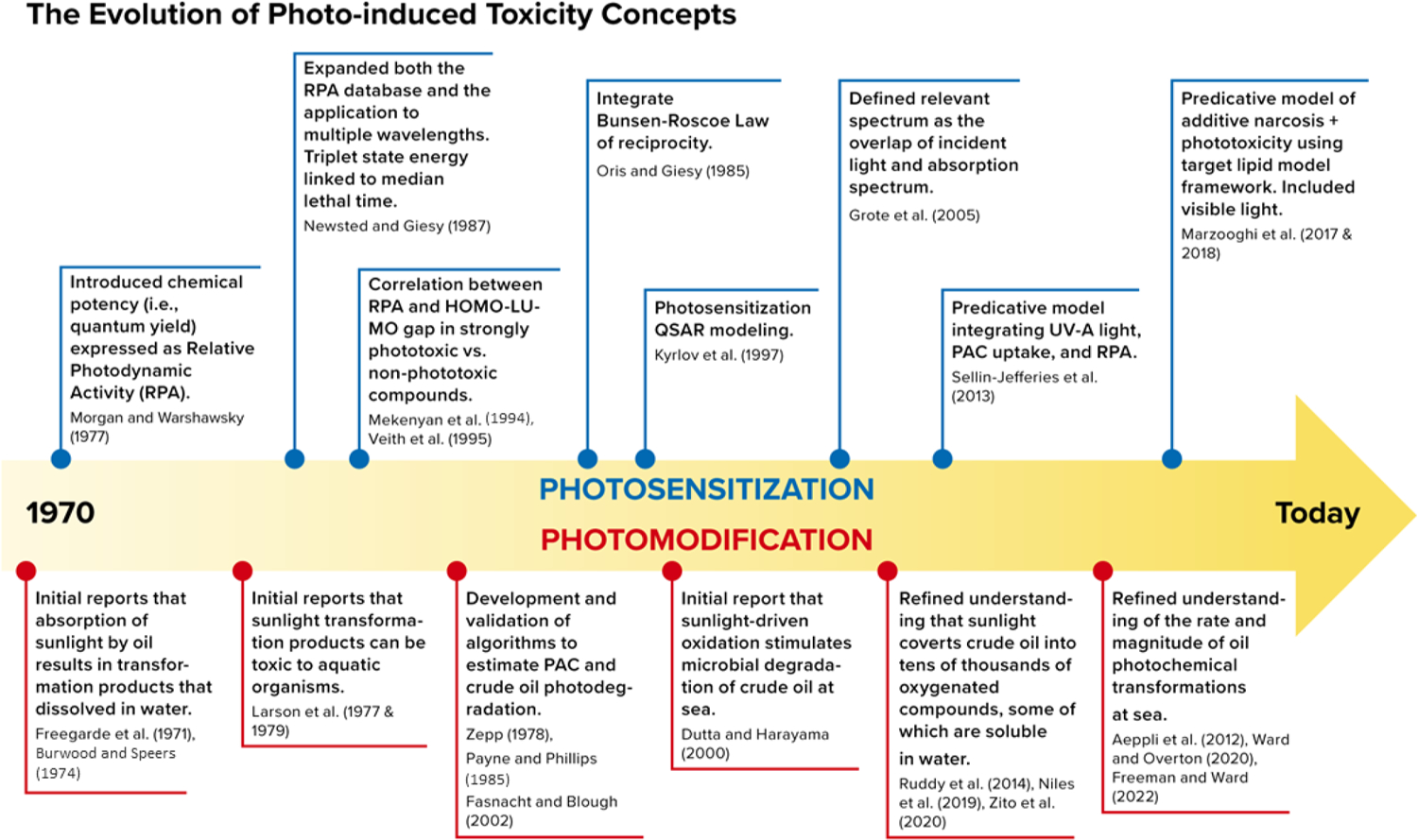

Photosensitization requires accumulation of a photosensitizing chemical in an organism and exposure to wavelengths of light specific to each compound’s structure. The result of photosensitization is a transient change in energy state but no structural change in the compound. Photosensitization has been well studied in both mammals and aquatic organisms across a broad range of compounds, including alkaloids, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and petroleum (Barron, 2017), and is a mode of toxicity that is dependent on the simultaneous co-occurrence of the photosensitizing compound in organism tissues that are also exposed to light. There are several models of photosensitization reviewed by Marzooghi et al. (2017) and summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

General time sequence of the development and evolution of predictive phototoxicity models (Aeppli et al., 2012; Dutta and Harayama, 2000; Grote et al., 2005; Krylov et al., 1997; Larson et al., 1979; Mekenyan et al., 1994; Newsted and Giesy, 1987; Oris and Giesy, 1985; Veith et al., 1995).

Photomodification differs from photosensitization in that during photomodification light exposure often occurs first outside of the organism, where the spatial-temporal gap between the modification event and organism exposure can be significant and there is a structural change in the chemical such as the formation of photooxidized compounds. While the basic photochemical framework underlying photomodification of oil substances and PACs has been known for decades (Burwood and Speers, 1974; Zepp, 1978; Fasnacht and Blough, 2002) it is less understood than photosensitization. However, there is an emerging interest and growing body of literature on the fate of photomodified oil and the generation, persistence, and toxicity of photomodified products (Niles et al., 2019; Ward and Overton, 2020; Zito et al., 2020; Freeman and Ward, 2022).

The objectives of this article are to further advance CROSERF methods by recommending approaches for designing, conducting, and reporting studies of the photo-induced toxicity of petroleum products and petrogenic PACs. Greater standardization of laboratory studies on both mechanisms of photo-induced toxicity will further advance comparisons across studies and the utility of study results in the development of predictive photo-induced toxicity models used in oil spill hazard and risk assessment. Standardized study conditions and data reporting guidelines on chemical exposure and toxicity endpoints will support lab-to-field extrapolations. Guidance is provided for the types of data that need to be reported to support photochemical modeling-based extrapolations.

2. Background

2.1. Solar radiation in aquatic environments

Sunlight is a natural component of all surface water systems (Williamson et al., 2001), and light exposures to aquatic organisms is dependent on the spectra and quantity of solar radiation reaching the organism. The more energetic wavelengths of light (i.e., all ultraviolet C (UV-C; 200–280 nm) and most of UV-B (280–320 nm)) are attenuated by atmospheric components before reaching surface waters, whereas the less energetic wavelengths (i.e., UV-A; 320–400 nm) and visible (400–700 nm) are attenuated less before reaching surface waters. Atmospheric attenuation is largely dependent on the season and latitude, which collectively determine the total pathlength of light due to solar angles throughout the year. The amount of light reaching surface waters is dependent on both daytime length (i.e., photoperiod) and the wavelength. Photoperiod and irradiation intensity generally resemble a bell-shaped curve with typical maxima at solar noon (e.g., Barron et al., 2000). High latitude areas have the highest range of photoperiod as well as the greatest base atmospheric attenuation due to solar angle, while low latitude areas have the lowest base atmospheric attenuation and smallest variation in photoperiod. Beyond these spatial-temporal factors, various weather conditions can further attenuate incident light prior to reaching oil slick and water surfaces (Baker et al., 1980). For example, environmental conditions such as daily changes in cloud cover and precipitation can reduce surface irradiance to less than 10% of expected maxima (e.g., Barron et al., 2008). Sunlight can be further attenuated at the water surface (e.g., reflectance) and by the light blocking properties of slick oil and aquatic vegetation.

Within the water column, solar radiation is attenuated by light absorbing (e.g., water molecules, dissolved organic carbon; DOC), and scattering (e.g., particulates) constituents. These water characteristics determine the maximum penetration depth (Barron et al., 2000; Barron et al., 2008; Barron et al., 2009). In natural waters, the rate of attenuation with depth is wavelength dependent and is unique to the conditions and characteristics of each body of water. This means that two spectra that are identical at the surface can attenuate differently in water bodies with changes in depth. Different wavelengths of light are absorbed at different rates, creating a depth gradient of light throughout the water column. UV-B light is readily attenuated, whereas UV-A and visible light penetrate deeper into the water column. In oligotrophic waters, UV light can penetrate tens of meters, whereas in some coastal waters and freshwaters UV can be attenuated completely in less than one meter (Tedetti and Sempere, 2006; Barron et al., 2008; Barron et al., 2009; Barron, 2017).

UV radiation can cause toxicity to organisms through direct exposure; however, many species have evolved various strategies to mitigate UV stress. A review by Dahms and Lee (2010) provides an overview of the wavebands of sunlight that can act as a stressor to aquatic life. Some adaptations are physiological and morphological such as armoring, pigmentation, and intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging mechanisms, while others are behavioral such as vertical migration, shade seeking, burrowing, light avoidance or occupying habitats with minimal exposure to solar radiation (Zagarese and Williamson, 1994; Leech and Johnsen, 2003; Barron, 2007; Finch et al., 2016; Finch and Stubblefield, 2016).

Key adaptations in some organisms include repair mechanisms essential for recovery after photodamage has occurred (Zagarese and Williamson, 1994). The toxicity of light to organisms is dependent on wavelength, intensity, and exposure duration. Exposure to shorter wavelength (i.e., UV) light prompts photoprotection (e.g., increased pigment production), photorepair (e.g., ROS scavenging and repair enzymes) (Williamson et al., 2001), and genomic repair processes (as reviewed by Kienzler et al., 2013). These are similar to some response mechanisms to photosensitization such the induction of ROS scavenging enzymes (e.g., glutathione). High energy light exposure can also induce responses observed in photosensitization such as DNA methylation, DNA strand breaks, and base pair dimerization (reviewed by Brem and Karan, 2012). Organisms have various adaptations to light exposure and exhibit similar range of tolerance based on latitude, life history, and niche (Calkins and Thordardottir, 1980), although this tolerance can be reduced if kept under low-UV or generally low light conditions over time.

Species sensitive to photosensitization include those with translucent life stages that are deficient in pigmentation and have an epidermis of only a few layers (Hunter et al., 1982; Finch and Stubblefield, 2016), early life stages residing in shallow waters (Alloy et al., 2015), and species with reproductive strategies that involve external fertilization with free-floating embryos on the ocean’s surface (Alloy et al., 2016, 2017). Consequently, an analysis of susceptible species in an aquatic community based on organism life history is essential for evaluating photo-induced toxicity.

2.2. Mechanisms of photo-induced toxicity

For photosensitization to occur, a light absorbing compound must first be taken up by the organism via absorption through ingestion, sorption through skin, and passive diffusion across the gill epithelium (Barron, 1995). Sufficient light of relevant wavebands must also be able to penetrate the water column deep enough to reach the organism. Then location of the photodynamic compound must be such that relevant wavebands of light readily reach its sites within the organism.

Upon absorbing the photon, the compound enters an excited state. This instability is relieved by reaction with either cellular components (type 1 photosensitization) or dissolved oxygen (type 2 photosensitization) resulting in one of many forms of ROS and lipid peroxidation chain reactions (reviewed in Roberts et al., 2017). The half-life of these reactive species varies from microseconds to nanoseconds. Intracellular defenses scavenge ROS and halt lipid-peroxidation chain reactions, but the capacity of these compensatory mechanisms varies by species (Alloy et al., 2016; Alloy et al., 2017; Alloy et al., 2015; Finch and Stubblefield, 2016; Roberts et al., 2017), as well as other factors moderating exposure or exposure sensitivity such as maternal transfer in embryos and larva before endogenous feeding (Damare et al., 2018; Pelletier et al., 2000), and developmental windows (Finch and Stubblefield, 2016; Sweet et al., 2017).

The phototoxic dose is a function of both the tissue concentration of photodynamic compounds and the amount of relevant light reacting with the bioaccumulated chemical. Toxicity occurs when ROS stress exceeds the capacity of an organism’s compensatory abilities. When light exposure ends the production of photochemical-origin ROS stops, but any peroxidation-chain reactions continue until compensatory mechanisms stop the reactions. This can lead to a delay in the manifestation of full effects until a period after the end of the last light exposure but prior to the start of the following light exposure (Choi and Oris, 2000). While photo-induced toxicity of petroleum products and PACs is largely attributed to enhanced toxicity caused by their interaction with ultraviolet radiation, the role of visible light in photosensitization is an area in need of further investigation (Ward et al., 2018).

In contrast, photomodification of petroleum substances may take several pathways. One pathway is direct oxidation, where the absorption of photons causes a chemical modification of the light-absorbing constituents of the oil. Another is indirect oxidation, where the absorption of photons yields ROS, which then modify a wide range of oil constituents, not just those that directly absorb light. Regardless of the formation pathway, the structure of the resulting photoproducts and their toxicities are poorly characterized. Moreover, the photoproducts are generally assumed to be less volatile, more water-soluble, and more bioavailable due to their increased oxygen content.

Under field conditions, sunlight rapidly modifies crude oil on the surface of water into new oxygenated compounds. While research on this topic dates nearly a half a century (Freegarde et al., 1971; Larson et al., 1977; Payne and Phillips, 1985; Sydnes et al., 1985), substantial progress has been made over the past decade (Ward and Overton, 2020). Initial estimates suggest that nearly 10% of the floating oil in the Gulf of Mexico after the Deepwater Horizon spill was transformed into new, oxygenated compounds that dissolved into seawater, an amount that compares to environmental fates of surface oil through other pathways including biodegradation and stranding on shorelines (Freeman and Ward, 2022). The chemical composition of these water-soluble products has been characterized using a wide range of analytical methods, broadly finding that they are a complex mixture of tens of thousands of oxygenated compounds (Ruddy et al., 2014; Niles et al., 2019; Zito et al., 2019). The oxygen containing functional groups include alcohols, acids, ketones, aldehydes, quinones and peroxides (reviewed by Payne and Phillips, 1985). The partitioning of photoproducts from oil to water proceeds systematically as a function of the molecular weight and number of oxygen atoms photochemically added to the hydrocarbon molecule (Zito et al., 2020). That is, the smaller and more oxidized the photoproduct, the more readily it partitions into the water phase. The complex nature of oil photoproducts, as well as numerous associated analytical challenges (e.g., poor GC amenability), limits the ability to quantify such photoproducts, with <1% quantified to date (Aeppli et al., 2018; Benigni et al., 2017).

Despite current limitations in identifying photoproducts, photomodification has direct implications for toxicity. While photomodified compounds span the oil, oil-to-water interfacial, and water phases, the latter is of particular interest to toxicity studies because photoproducts can have higher bioavailability. Consistently, studies have shown that oxy-hydrocarbons are more water-soluble relative to the parent compounds (Duxbury et al., 1997; Lampi et al., 2006; Mallakin et al., 1999), resulting in higher aqueous concentrations of less hydrophobic chemicals. Furthermore, some oxygenated compounds are sufficiently hydrophobic to partition into biological membranes (Duxbury et al., 1997). While there is evidence of the greater toxicity of photomodified compounds relative to their parent forms (Choi and Oris, 2000; Lampi et al., 2007; reviewed in Roberts et al., 2017), there is less known about the overall importance of photomodification as a mode of toxicity to aquatic organisms compared to photosensitization. Moreover, photomodification reactions can co-occur in photosensitivity tests, and the relative contributions of photomodified compounds to toxicity can be difficult to parse from photosensitivity. For this reason, some dosing methods such as passive dosing, and microdroplet forming water accommodated fractions (Stubblefield et al., 2023) may be more prone to mixed modes of action than others, such as exposure to light in clean water after oil or PAC exposure (see Section 3.3 below for details).

2.3. Photo-induced toxicity under field conditions

The photo-induced toxicity of oil under field conditions is complex as there are several processes and factors that modulate interactions between oil, sunlight and their exposure to aquatic organisms. In addition to inherent differences in species sensitivity, incident solar irradiation and atmospheric and water column attenuation determine maximum light exposures within an aquatic organism. Once light has reached and propagated below the water surface it can interact with petroleum compounds and aquatic organisms. However, water quality characteristics such as turbidity (Ireland et al., 1996), the presence of chromophoric dissolved organic carbon (Gensemer et al., 1998; Nikkila et al., 1999; Weinstein and Oris, 1999), and chlorophyll (Smith and Baker, 1979) can affect light penetration in the water column and decrease the likelihood of photo-induced toxicity.

Weathering through processes such as evaporation, photolysis, microbial degradation, and emulsification can alter the composition and physical and chemical properties of petroleum (Sivadier and Mikolaj, 1973; Larson et al., 1977; Jordan and Payne, 1980). Weathering generally leads to the loss of lighter compounds (1–2 ring PACs) and the enrichment of heavier compounds, some of which are known to be photosensitizers (3–5 ring PACs; Riley et al., 1980; Barron et al., 1999). The starting oil composition and the interplay of weathering processes determines the extent of photosensitization and photomodification reactions.

Crude oils vary in their chemical composition and, as a result, differ in their phototoxic potential. For example, Wernersson (2003) found that middle distillates containing a higher number of tricyclic PACs are phototoxic by photosensitization, whereas oil products that contain primarily mono- and di-aromatics have less phototoxic potential. Heavier petroleum such as Alaskan North Slope crude oil (ANSCO) and residual fuel oils such as bunker oil are generally more phototoxic by photosensitization due to a larger fraction of 3–5 ringed PACs (Wernersson, 2003; Hatlen, 2010; Incardona et al., 2012).

Attempting laboratory to field experimental extrapolation requires careful consideration of the factors that can modulate photo-induced toxicity (Section 2.1). In particular, behavioral adaptations to light stress such as photo-avoidance should be considered. When expressions of these behaviors are restricted by the constraints of experimental design (i.e., confinement without sufficient depth or shade available), toxicity purely attributed to light exposure can occur. Another consideration is a decrease in light tolerance in some species after multiple generations cultured in low (i.e., indoor lighting) light conditions (Calfee et al., 1999). Dietary components (e.g., carotenoids, and mycosporine-like amino acids) can influence the UV tolerance of some species (Moeller et al., 2005) and some vertebrates can synthesize these compounds de novo (Osborn et al., 2015).

Because of the complexities described above, it is important that photo-induced toxicity tests follow experimental designs appropriate for each mechanism of toxicity. Study outcomes could then be used in hazard evaluations and to develop, improve, and validate mechanistic models which if coupled with oil fate and exposure models (French-McCay, 2002, 2003, 2004) could evaluate the effects of photo-induced toxicity under field conditions (e.g., French-McCay et al., 2023).

3. Guidance for conducting photo-induced toxicity studies

3.1. Test species

Early life stages of aquatic vertebrates and invertebrates, and plankton are particularly susceptible to photosensitization, attributable to their relative transparency. In addition, aquatic species at risk of photosensitization include those that are translucent, occupy the surface or upper water column, live in transparent waters, require shallow water habitats, or exhibit positive phototaxis. The organism life history and behavior must be considered in context with light exposure and life history in determining ecological relevance and risk. When conducting toxicity testing in support of environmental assessments, the environmental variables (i.e., water type, location, aquatic community) unique to the area where oil contamination has occurred should be considered. The water type (i.e., freshwater, estuary, or marine) for which oil contamination has occurred should be the basis for selecting freshwater or marine organisms for testing. Ideally, photo-induced toxicity studies would emulate the natural water quality conditions from the oil spill area or use natural sea water that has been sterilized.

There are a limited number of model test organisms with established laboratory culture methods. Standard test organisms are often used as surrogate species. Common saltwater test organisms include, but are not limited to, mysid shrimp (Americamysis bahia), grass shrimp (Palaemontetes sp.), larval eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica), inland silverside (Menidia beryllina), and sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus). Common freshwater test organisms include, but are not limited to, fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), rainbow trout (Oncoryhynchus mykiss), amphipod (Hyaella azteca), water flea (Daphnia sp.), and zebrafish (Danio rerio). New aquaculture methods can be developed if more site-specific aquatic species are of interest (e.g., Gulf killifish – Finch and Stubblefield, 2016; Blue Crab and Mahi Mahi – Alloy et al., 2015, 2016). However, when considering the available and common test organisms, testing in support of environmental assessments should focus on organisms that are pertinent to the oil spill area, including sensitive species and life stages, or are consistent with the scientific questions and objectives of the particular study (Bejarano et al., 2023; Stubblefield et al., 2023).

Unlike photosensitization, photomodification of petroleum substances occurs prior to chemical absorption by aquatic organisms, and thus this mechanism is not affected by many organism characteristics that might mitigate photosensitization. By these criteria, early life stages of fish and invertebrates, and in particular larvae, may be the first choice for assessing photomodification of petroleum under laboratory conditions.

3.2. Response endpoints

Standard acute toxicity tests, including 48 h for invertebrates and 96 h for vertebrates (US EPA, 2002; ASTM, 2014), are more frequently used in photo-induced toxicity testing than chronic tests because short term exposures to petroleum substances and light are generally more consistent with field conditions (see Section 2.3). Acute toxicity studies typically focus on limited duration studies with medium to high light exposures at environmentally relevant concentrations. Light exposures in a 96-h acute photo-induced toxicity testing can include up to four photoperiods (e.g., 4, eight-hour illuminated times over 96 h), but may be as short as a single photoperiod. Ideally, light exposure will mimic natural light intensity and duration; however, another common method is to average light intensity observed in a single day over the photoperiod relevant to the location of interest. If organism life history characteristics suggest limited light exposures during the day, then the light exposure duration should be reduced, or the light dosing treatments should span the expected range of possible light exposures to provide a more ecologically relevant examination of phototoxic effects.

Most apical endpoints are the same across short-term and chronic durations, and between photosensitization and photomodification toxicity tests (e.g., survival, malformations, cardiac condition, growth). However, direct comparisons of photosensitization and photomodification may not be appropriate for some endpoints such as fertilization success or fecundity. For example, photosensitizing compounds can be maternally transferred to offspring (Nielsen et al., 2020). In maternal transfer of photosensitizing compounds, toxicity only manifests when embryos or larva are exposed to light. In contrast, photomodified compounds would not be expected to have latent toxicity, complicating direct comparisons of reproductive endpoints such as fecundity or hatching success.

3.3. Experimental design and dosing

Test designs should generally align to guidance given in Stubblefield et al. (2023) where possible, with specific exceptions unique to photo-induced toxicity evaluations. Experimental design of photosensitization and photomodification studies can vary substantially based on the specific study objective and data needs, and it is not possible to design experimental systems that represent every exposure scenario. Therefore, a Tables 1 and 2 are offered here to provide guidance for conducting photo-induced toxicity studies and generating data with considerations of experimental design goals and the instrumentation specific to photo-induced toxicity testing. The following guidance for developing and reporting toxicity testing is applicable to petroleum, single compounds, and well characterized mixtures of petrogenic compounds.

Table 1.

Recommendations for designing an acute (indoor or outdoor) and chronic photosensitization studies.

| Test Design | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute tests | Chronic tests | ||

| Variable | Indoor | Outdoor | |

| Treatment levels | Minimum of 5 | Minimum of 5 | Minimum of 3 |

| Light treatment levels | Minimum of 2L | ||

| Light intensity | Medium to high* | Natural sunlight | Low to medium or natural sunlight |

| Light duration | One photoperiod or shorter | Natural photoperiod | (1) Natural photoperiod (2) Environmentally relevant exposure based on organism behavior |

| Controls | Negative, solvent, positive, light, oil, or single compound | Negative, solvent, positive, light, oil, or single compound | Negative, positive, light |

| Test Duration | 48 or 96 h | 48 or 96 h | ≥7 days, depending on species |

| Equilibration period | 8 h** | ||

| Resting period Endpoints | 8 h** Survival, behavior, cardiac condition | Survival, behavior, cardiac condition | Growth, survival, reproduction, hatching success, deformities |

Minimum 100% light and a reduced light (e.g., 10%) or dark (0%) treatment.

High intensity not to exceed relevant seasonal and latitude solar maximum.

Fresh oils have high benzene, toluene, ethyl-toluene, and xylene (BTEX) components, which have high narcotic toxicity. It is recommended to use a dark control even with weathered oils and single compound testing.

Unless the impact of uptake or recovery period is being investigated as part of the study design.

Table 2.

Considerations for conducting and reporting photosensitization and photomodification experiments. Specific factors to consider should be fit for purpose and will depend on the specific objectives of the study. See Table 1 for details

| Test Parameter | Photosensitization | Photomodification |

|---|---|---|

| Test species | Susceptible species: translucent organisms, early life stages of fish and invertebrates, plankton; standard test species are recommended | Susceptible species: early life stages of fish and invertebrates, plankton; standard test species are recommended |

| Test type | Acute, followed by chronic | Acute and chronic to address data gaps |

| Endpoint | Mortality, growth/development, behavior | Mortality, growth/development, behavior |

| Exposure duration | Time dependent, standard test duration | Time dependent, standard test duration |

| Endpoint metric | LC50, EC50, LT50, time-varying, use integrated phototoxic dose unit (Σ μM/L·mWs/cm2) | LC50, EC50, LT50, time-varying |

| Test material | Single compounds; fresh/weathered oil | Intact/oxy-hydrocarbon (if available) compounds |

| Light exposures | Light intensity, spectra distribution and duration; irradiation source must be reported; recommended units W/m2/nm, W/cm2/nm | Light intensity, spectra distribution and duration; irradiation source must be reported; recommended units W/m2/nm, W/cm2/nm |

| Controls | Positive and negative controls, solvent, light and oil controls | Positive and negative controls, solvent and oil controls |

| Chemical analyses | 2–7 ring PACs and alkylated PACs at test at test initiation and termination | Intact/oxy-hydrocarbon compounds at test initiation and termination |

| Analytical methods | GC-MS*, FT-ICR-MS**, GCxGC-MS***, and others. | Method development may be needed (see Section 3.4.2 Photomodification)** |

| Risk factors during spills | Light dynamics/UV penetration in the water column, photoperiod, atmospheric conditions, latitude, water quality conditions; animal behavior and vertical distribution within the water column | Light dynamics/UV penetration in the water column, photoperiod, atmospheric conditions, latitude, water quality conditions |

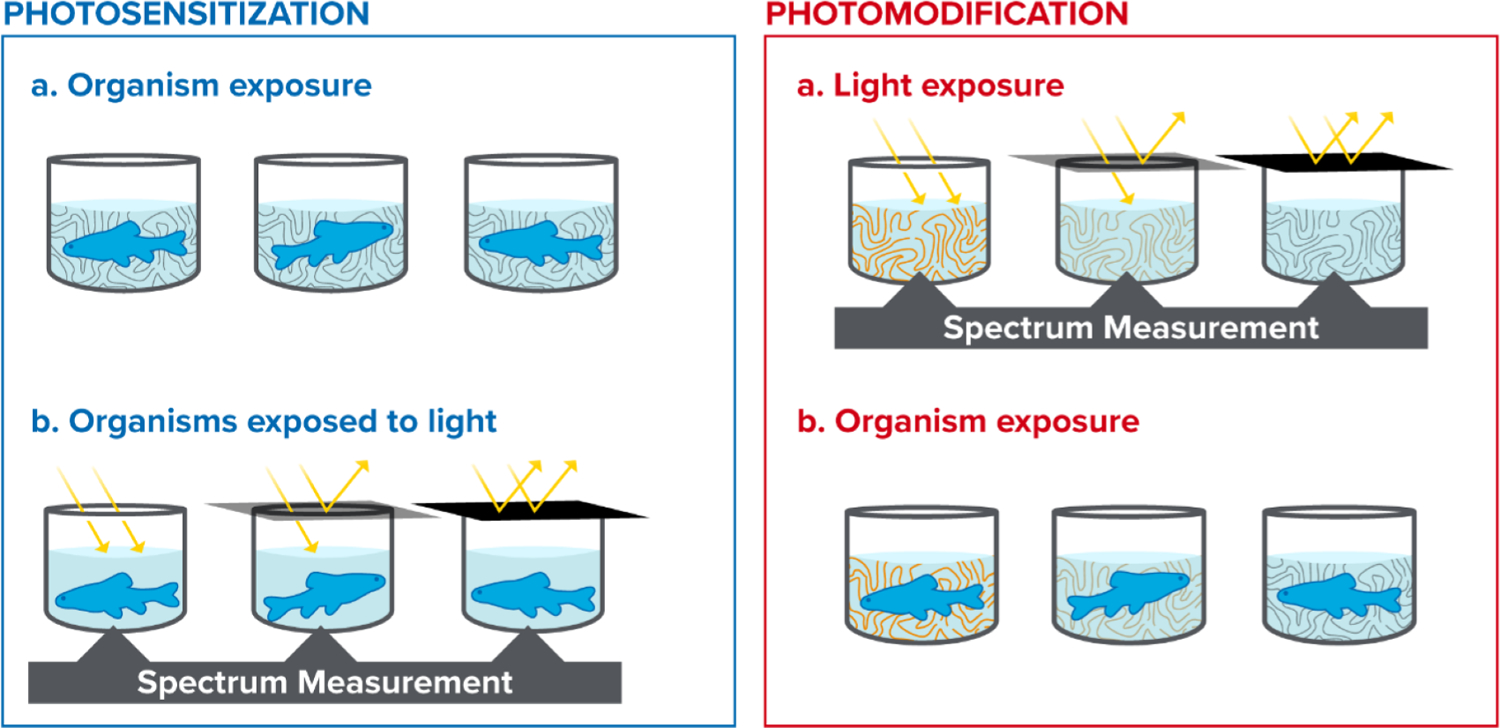

3.3.1. Photosensitization tests

Photosensitization testing is fundamentally a co-exposure of two stressors (photodynamic compounds and solar irradiation) and their synergistic effect (photosensitization). This is regardless of whether the exposure compound is a single petroleum compound, a known mixture of petroleum substances, or an oil. The inherent stress of solar irradiation can cause toxicity, particularly in organisms cultured under standard laboratory fluorescent lighting for generations. UV light can be toxic to early life stages of many invertebrate organisms, and laboratory acclimation may be needed to achieve acceptable control survival (e.g., Calfee et al., 1999). Photosensitization studies require additional control treatments to ensure that the highest tested light treatment does not cause significant toxicity in the absence of petrogenic hydrocarbons (Fig. 3). To separate photo-induced toxicity from other mechanisms of petroleum toxicity (e.g., narcosis), a high UV-only control is needed in addition to standard controls with a no UV or low UV light treatment.

Fig. 3.

General sequence of light and oil exposure in photosensitization (left) and photomodification (right) experiments.

Acute photosensitization testing includes an initial exposure of the organism to the test substance to allow for the bioaccumulation of compounds into the organism’s tissues before light exposure. This initial exposure period (hereafter termed equilibration period) is the exposure of organisms to test solutions without significant light exposure for a time period. By limiting light exposure, this allows the partitioning of test substances from the solution into the organism’s tissues without photosensitization reactions occuring. While the bioaccumulation phase varies depending on the test organism and study objectives, it is recommended to use an eight-hour or overnight equilibration period unless the effect of various exposure times is under investigation. At least eight hours is recommended for practical considerations. Research demonstrates that while specific compound uptake rates are influenced by many factors (e.g., organism life stage, organism species, logkow of the compound, binding competition with dissolved organic matter, and others) in controlled laboratory conditions rapid accumulation occurs for two and three ringed PACs within the first eight hours of exposure (Morgan and Warshawsky, 1977; Spacie et al., 1983; Duxbury et al., 1997; Petersen and Kristensen, 1998). Specific research aims may require a different compound and light exposure periods. Exposure dynamics should be considered in the experimental design. For example, a one-hour oil equilibration period in the dark followed by eight hours of simulated sunlight will likely have a different degree of photo-induced toxicity than eight hours of oil equilibration paired with the same eight hours of light exposure. Monitoring and data reporting of both chemical analyses and light exposures are crucial in making comparisons among experiments with different -or absent- petrogenic and light exposure regimes. Acute photosensitization testing should also include monitoring for latent effects or delayed injuries. Guidance on developing a standard practice indoor and outdoor acute photo-induced toxicity studies is provided in Table 1. Fig. 3 (left) is a conceptual diagram depicting sequential oil and light exposures and irradiance monitoring during light exposures.

Chronic photo-induced toxicity testing is used to assess longer durations of substance and or light exposure, typically at lower levels used in acute toxicity tests. Similar to acute tests, chronic photosensitization testing includes either sequential (oil, then light) or co-exposures of oil or PACs and light. Chronic studies also allow for petroleum exposure toxicity effects, such as the disruption of the vertebrate stress axis (Cartolano et al., 2021), that may not manifest in acute durations or may be overshadowed by photosensitization and narcotic effects from the higher concentrations used in acute testing. The possibility of photomodification occurring during chronic photosensitization exposures has not been studied. Guidance on developing a standard practice chronic photo-induced toxicity study is provided in Table 1.

3.3.2. Photomodification tests

Generally, a photomodification test employs a controlled exposure of a solution of compounds to a known light source at known intensity and duration that should include specific analytical methods to track the dynamics of photochemical reactions. These reactions can be controlled, to some degree, by manipulating light spectra, and the duration of irradiation. The most important experimental design difference between photosensitization and photomodification toxicity testing is the absence of the initial hydrocarbon exposure of the test organism and the difference in light exposure timing. Petroleum substance exposure solutions -or thin oil films- are exposed to a light source (natural sunlight or simulated sunlight) without test organisms present. After the test solution (or thin oil film) has been irradiated, the resulting solutions are used to expose organisms without significant light present. Fig. 3 (right) is a conceptual diagram depicting the solution irradiation and monitoring period without test organisms, and the following exposure period with organisms without the light treatments.

Toxicity testing in a photomodification experiment can be generalized into the requirements for testing single chemicals (e.g., relevant photo-oxidation products), and testing of irradiated oil substances. Testing of single chemicals can follow existing guidance for toxicity testing, including clear reporting of exposure concentrations during the test, and the biological endpoints. Testing of irradiated oil and thin oil films are less clear because the composition of the oil photoproducts has not been widely characterized (Ward and Overton, 2020). This remains a research need to develop appropriate characterization and toxicity assessment methods. Quantitative and semi-quantitative methods can be used to characterize relevant constituents or groups of constituents as well as implementation of total bioavailability measurements techniques with as non-depletive solid phase microextraction (Letinski et al., 2014; Redman et al., 2017a,b).

Experimental approaches to photomodify oil constituents in preparation for toxicity testing largely depend on the phase that oil constituents are being exposed to sunlight (i.e., dissolved compounds vs. liquid crude oil). It is recommended to perform photochemical exposures of dissolved petroleum compounds, as a baseline scenario, following methodological steps described in OECD 316 (OECD, 2006; see Section 3.3.3 Indoor light sources). Chemical analyses and toxicological assays should be conducted on both the dark-control and light-exposed treatments, affording a link between photochemical changes to the constituents and their potential toxicities.

In the present work, recommendations are that photochemical exposures of oil largely follow the same approach as OECD 316 (OECD, 2006), however, research into the toxicity of photomodified substances is less standardized. Testing of irradiated oils could employ standard CROSERF WAF techniques (e.g., Parkerton et al., 2023) or well characterized thin oil films, if they are combined with chemical compositional data to support the interpretation of the observations (e.g., Dettman et al., 2023). Regardless of the oil substance preparation technique chosen there are a few considerations common to all photomodification testing. First, given the strong attenuation of light by crude oil, the most important control of photo-oxidation rates is pathlength in the oil phase (Freeman and Ward, 2022). Therefore, creating a uniform oil film of known thickness or a well characterized WAF is critical to ensure comparisons across oil types and studies. Second, molecular oxygen is readily consumed by crude oil during light exposure (Ward et al., 2018) and is the primary oxidant (Lichtenthaler et al., 1989; Ward et al., 2019). Therefore, ensuring abundant oxygen availability during light-exposure is critical to facilitate oxidation, guidance that applies to dissolved phase photochemistry as well. Finally, it is prudent to evaporatively weather the oil before sunlight exposure to avoid oxidation of constituents that readily evaporate at sea (Gros et al., 2014), providing a more accurate chemical representation of surface oil susceptible to modification by sunlight. The extent of pre-weathering will depend on the oil type and spill conditions (e.g., temperature and wind speed). Two common approaches to artificial weathering are heating oil until mass loss from evaporating the lighter compounds reaches an asymptote (Forth et al., 2017) or evaporating at ambient temperature under dry nitrogen flow until the same mass loss asymptote is achieved. Analytical characterization of water-soluble photoproducts for toxicity assaying can be done using liquid/liquid extraction, solid-phase extraction, or passive sampling (Benigni et al., 2017; Redman et al., 2018a; Redman et al., 2018b; Zito et al., 2019, 2020). Dettman et al. (2023) provides guidance on instrumentation selection and analytical methods.

Testing of transient photoproducts during irradiation needs additional investigation to determine rates of formation, degradation, and bioaccumulation. During a photomodification test, the overall exposure concentrations and composition of oil constituents are changing, resulting in a very complex exposure system that requires characterization to understand any observed effects.

3.3.3. Indoor light sources

In laboratory studies, the ideal light source will either be natural sunlight or a solar simulator that is intended to mimic natural sunlight by using full spectrum light lamps. OECD 316 recommends either natural sunlight or a filtered Xenon lamp as a light source (OECD, 2006). All lighting should be tested for spectral output prior to use. Many commercially available lights do not emulate the natural spectrum of sunlight, and a mixture of lamps may be needed to approximate sunlight. Even with adequate emulation of the solar spectrum at the waters’ surface, the organism of interest may occur at greater depths. In such cases the study design should account for expected attenuation by water depth in choosing the scope of their light regimes and treatment levels. UV light sources can present a particular challenge as commercial tanning lamps, blacklights, and many LED arrays contain sharp peaks or troughs that are out of proportion to natural sunlight. The challenges of particular UV light sources are detailed in Shankar et al. (2015). Some UV sources, such as curing lamp and germicidal lights, can emit more short-wavelength UV than occurs in the environment, thus invalidating test results. Recent advances in LEDs do show promise in allowing for fine control of exposure spectra (Ward et al., 2021; Freeman and Ward, 2022).

The spectrum of light is an essential variable that must always be reported for the light source. Conducting toxicity tests under similar light regimes provides the most comparable data. Natural sunlight that emulates the location of the oil contamination is ideal, but also requires a far greater measurement frequency to capture variation due to weather.

By some models toxicity is assumed to be proportional to the product of the light spectra and the chemical absorption spectra (Marzooghi et al., 2017, see Mechanism of Toxicity section). Marzooghi et al. (2017) compiled a list of lamp spectra in their Supporting Information from several common lamp sources and have provided a mechanistic framework for evaluating these data to support consistent toxicity testing and interpretation that is compatible with the general risk assessment. Importantly, manufacturer specifications should not substitute for spectral measurements and monitoring.

3.3.4. Measurement of test irradiance

When reporting light doses, power (watts) per unit area (m2 or cm2) per unit wavelength (nm) are preferred (e.g., W/m2/nm). Moles of photons per unit area-time can be converted to power if the wavelengths of the photons are known. Full monitoring between wavelengths 280 nm to 800 nm would cover the relevant wavebands with a large margin on the high and low energy tails.

Approaches for monitoring irradiance differ for natural and simulated exposure scenarios. For example, while continuous monitoring is required for outdoor experiments due to rapidly changing sky conditions, it is reasonable to assume that simulated light sources emit constant irradiation levels. This assumption, however, should be validated by monitoring simulated irradiance throughout the initial study period. Moreover, irradiance measurements for outdoor exposures need not be taken at the exact location of the samples (provided certain factors such as shade are the same). This step is critical for indoor exposures where spatial variability of simulated light, both vertically and horizontally, can be considerable.

While the approaches for monitoring irradiance differ between natural and simulated scenarios, the recommended methods are largely the same. The advantage of spectral radiometry is that it can more easily test spatial and temporal variation of irradiance in the exposure chamber. Moreover, the spectral data provided by the radiometer affords wavelength-resolved comparisons of simulated light to natural sunlight and to other study systems. The disadvantage of spectral radiometry is that in some scenarios it may be less representative of the light conditions “seen” by the samples, merely because light reflection or scattering off experimental apparatuses may increase irradiation levels compared to incident irradiance measured by a radiometer. An alternative approach that can better capture the light conditions “seen” by the samples is chemical actinometry, where an aqueous chemical system is exposed in the same experimental apparatuses as samples. Suitable actinometry systems for sunlight wavelengths include nitrate and nitrite (Jankowski et al., 1999), p-Nitroanisole/pyridine, p-nitroacetophenone/pyridine, and ferrioxalate (Laszakovits et al., 2017). In many cases, spectral radiometry measures of irradiance have compared favorably to those determined by chemical actinometry (e.g., Ward et al., 2018, 2021). Provided that spectral radiometry measures of irradiance are cross validated with chemical actinometry, we recommend using radiometry.

3.4. Chemical characterization

3.4.1. Photosensitization tests

Target analytes should include any positive control chemicals (e.g., anthracene, fluoranthene) as well as surrogate compounds or exposure metrics such as total PAC or selected phototoxic PACs that are associated with photo-induced toxicity. An example list of fifty PAC analytes is given in Appendix B. PAC concentrations in exposure media should be measured at test initiation and termination as noted in by Stubblefield et al. (2023). Reporting analytical results should follow the recommendations of Bejarano et al. (2023).

The photoactivated components of petroleum differ by petroleum product and weathering state and have not been fully characterized for any oil. This data gap is due to the complexity of oil as a mixture and the number of PACs and alkylated homologues in any one oil. Where data gaps exist, a common practice in the case of alkylated PACs is to use the parent PAC’s photodynamic potential. The phototoxic PACs to be measured in test media should include at least those identified to exhibit photosensitization or some UV absorbance (Appendix B; Marzooghi et al., 2018). Databases of absorption spectra are being compiled (Marzooghi et al., 2018).

3.4.2. Photomodification tests

Photoproducts have received relatively little attention in the published literature relative to the efforts used to characterize the parent hydrocarbons in oils, and other environmental media. However, relatively new analytical approaches (high resolution mass spectrometry, or multidimensional separation methods) have potential for improving our understanding of the environmental and ecotoxicity properties of photoproducts (Ward and Overton, 2020). Dissolved photoproducts are likely to be most bioavailable, and thus are the focus of this section.

The tools available to characterize water-soluble photoproducts vary from bulk- to molecular-level analyses. The specific application of analytical methods will vary with the study objectives (e.g., Dettman et al., 2023), but some minimum characterization is required to promote inter-study comparisons. One low-resolution quantitative bulk measurement that should be included in all photomodification studies is dissolved organic carbon (DOC), operationally defined as organic carbon that passes through a 0.2 μm filter. DOC analysis can provide a quantitative estimate the concentration of photoproducts in the dissolved phase (relative to the dark controls). DOC is a low-resolution method that allows for simple comparisons in dissolved phase oil compound among light treatments but does not have compound specificity (Roman-Hubers et al., 2022). More advanced high-resolution methods may be necessary provided that oil photoproducts exhibit notable toxicity. For example, ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry can semi-quantitatively fingerprint the elemental compositions (Ruddy et al., 2014; Benigni et al., 2017; Zito et al., 2019, 2020). This information can then be used to support inference of the likely structures of the thousands of daughter compounds produced by sunlight (Zito et al., 2020). Finally, while traditional gas-chromatographic methods are well developed for crude oil compounds, established protocols are not optimized for the quantification of individual oil photoproducts (Dettman et al., 2023).

The challenges characterizing and quantifying water-soluble oil photoproducts are largely related to composition and complexity of the chemical mixture. One of the substantial analytical challenges is that oil photoproducts are largely non-GC amenable, and thus require derivatization to analyze on a GC (Benigni et al., 2017). Even with derivatization, quantification is extremely low, with only <1% of possible photo products quantified in the oil-soluble fraction (Aeppli et al., 2018).

To date, few studies have attempted a comprehensive GC-based assessment of water-soluble oil photoproducts (Benigni et al., 2017). To circumvent the GC-amenability issue, many have adopted direct infusion ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry, which expands the analytical window of analysis far beyond 40 carbon atoms, including heteroatom containing products (Zito et al., 2020). This tool has greatly improved our understanding of the pathways of photo-oxidation and the chemical composition of oil photoproducts, but like all tools, it has its unique limitations. Namely, the ionization sources commonly used (e.g., ESI or APPI) are semi-quantitative, meaning that the relative abundance of an ion is not necessarily proportional to its concentration. Moreover, the structural information is limited unless tandem mass spectrometry approaches are employed. Adoption of chromatographic approaches on the front-end of ultra-high mass resolution detectors represents a promising next step towards simplifying and quantifying the chemical mixture (Rodgers et al., 2019).

In addition to these bulk, or high-resolution methods, it may be possible to measure total bioavailable chemicals, including photomodified products, using a non-depletive solid phase microextraction (SPME) technique (coupled with GC-FID detection) that mimics the aquatic exposure to test organisms (Redman et al., 2018a; Redman et al., 2018b). This method provides an operationally defined measurement of all constituents using an area under the curve approach that are correlated with toxicity data, and consistent with bioaccumulation theory (Redman et al., 2018a). While this method will not provide information on structure identity, it is a promising metric for evaluating the toxic potency of a photomodification exposure system, before or after irradiation. Dettman et al. (2023) provides a greater focus and detail on the complexities of photomodified petroleum compounds and recommendations on chemical analysis relevant to toxicity testing.

3.5. Data reporting

Initial guidance for endpoint and data reporting is given by Bejarano et al. (2023) and Stubblefield et al. (2023). Data reporting should include details on the exposure system (endpoints and duration), chemical composition of test substance and exposure solutions, and the characterization of the intensity and wavelength distribution of the light sources used in the studies, and duration of exposure is needed. For photosensitization studies, detailed reporting of the composition of photoactive compounds in the exposure media is highly recommended as this would facilitate assessments of their relative contributions to the overall toxicity. In addition, reporting all appropriate controls from photo-induced toxicity studies is important to ensure that experimental variables are not affecting study results. These include controls for the testing medium (i.e., negative control), the solvent (if any) used to dissolve exposure compounds (i.e., solvent/vehicle control), 100% light treatment with no photoactive compounds (i.e., light control), the highest compound exposure treatment with no light (i.e., exposure control; fresh oil or exposure solution only), and the phototoxic compounds under 100% light to validate the testing system (i.e., positive control). Standards for reporting water quality monitoring (e.g., dissolved oxygen, temperature, pH, etc.) are given in the experimental conduct paper (Stubblefield et al., 2023).

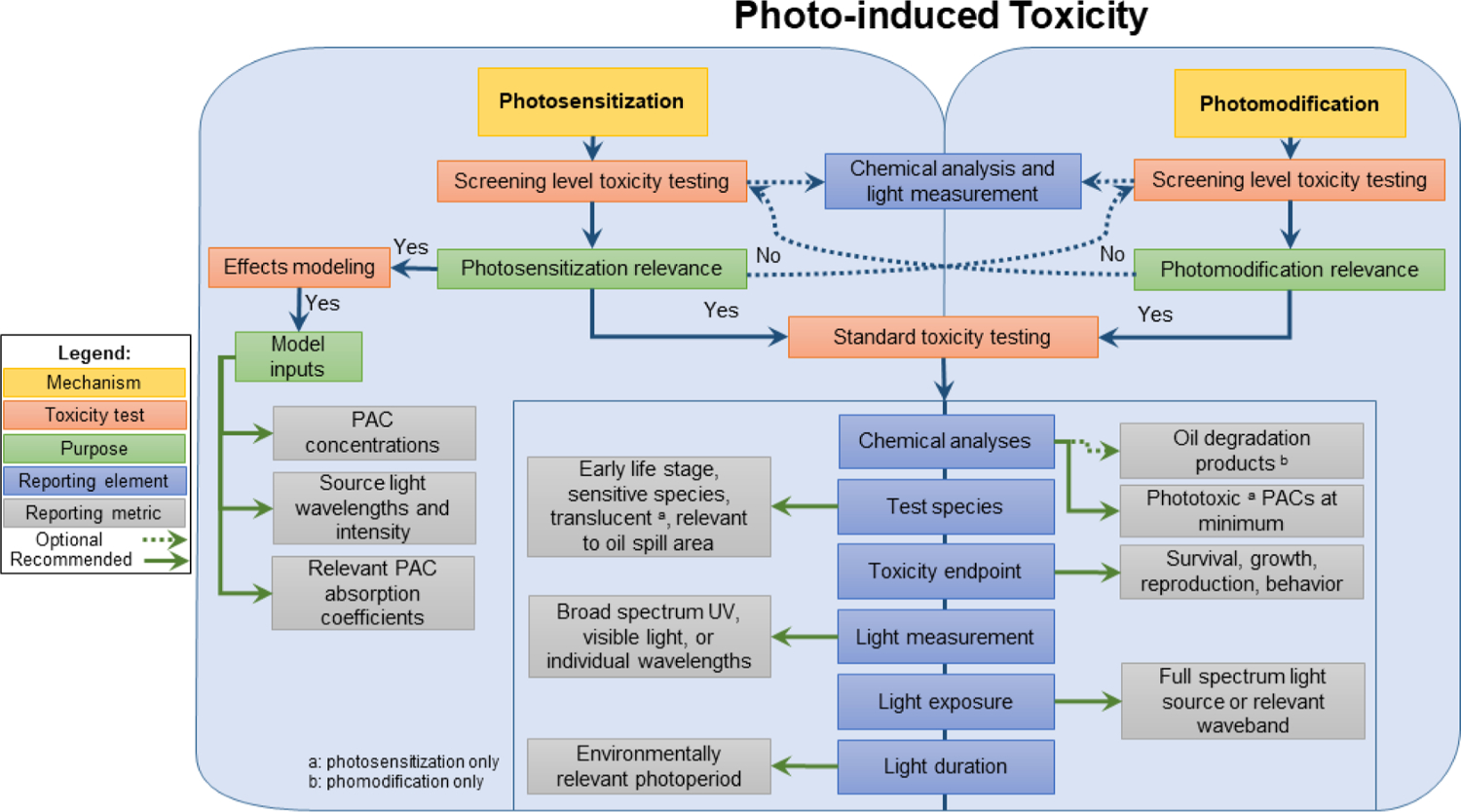

For photomodification studies, there are significant analytical challenges to elucidating all possible degradation products and pathways. Clear communication of the uncertainties and decision rationales around analytical approaches used in quantifying degradation products is equally as critical as reporting chemicals that were quantified. A decision framework is given in Fig. 4 covering both photosensitization and photomodification.

Fig. 4.

Phototoxicity decision framework for photosensitization and photomodification experiments with petroleum substances and polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs).

4. Practical applications

4.1. Laboratory and field studies

Laboratory studies are particularly useful for controlling environmental variables, facilitating comparisons across studies, addressing data gaps in hazard and risk assessments, and validating model predictions. Controlling the concentration of compounds, light intensity, and spectrum composition in laboratory studies allows for focused objectives to be investigated. For example, if an organism’s behavior suggests that exposure to incident light is limited to particular times of the day or is limited to pulsed or short-term exposures, then risk can be better evaluated by controlling these variables. Furthermore, laboratory studies allow examination and comparison of different species and organism life stages to determine sensitivity when little information is available. There is no single field or laboratory-based test system capable of being representative of all relevant exposure scenarios. The modeling approaches discussed in French-McCay et al. (2023) may provide a basis for lab-to-field-extrapolation and comparability between studies as detailed below.

The ecological significance of photo-induced toxicity to aquatic organisms under field conditions depends on three key factors described in Section 2.3. Taking those into account, species sensitivity would depend on the relative capacity to accumulate and eliminate photo-activated compounds; susceptibility to oxidative stress; presence of pigments or armoring that attenuates tissue penetration of light; and behavioral adaptations that reduce light exposure such as avoidance. Under field conditions, photosensitization, photomodification, and light-independent toxicity (e.g., narcosis, cardiotoxicity) are likely to play a combined role in aquatic toxicity.

One approach to photomodification testing for model development is to generate empirical toxicity data for photoproducts in blocks (i.e., petroleum compounds grouped by ranges of boiling point, or LogKOW range, ring number, or some other characteristic). Block testing following the standards of data reporting given in this document and the associated CROSERF guidance would include light composition, intensity, and substance absorption properties in association with toxicity. Any photomodification experiment must collect compound concentration data at a fine enough resolution to characterize loss of exposure due to photodegradation. The difference in toxicity could then be used to parameterize the block of photoproduct toxicity.

Field studies are often employed to confirm laboratory results or provide additional context for natural resource damage assessments. Conducting a photo-induced toxicity-based field or in situ study could involve designing a custom test system that houses environmentally relevant test organisms and includes exposure to natural incident light and ambient water. Field studies can also be useful for collecting site-specific characteristics to evaluate environmental relevance and the likelihood of photo-induced toxicity. Specifically, field studies can provide information on the aquatic community composition, light intensity and extinction coefficients in ambient waters, water quality influences on light exposure, and environmentally relevant concentrations. Collecting relevant field information can be used to inform the test design for laboratory studies, provide inputs for predictive modeling, and assist in determining phototoxic risk for environmental risk assessment. Many factors mitigating photo-induced toxicity are typically not accounted for under controlled laboratory conditions, and thus, laboratory exposures may represent worst-case scenarios with results representing conservative assessments of photo-induced toxicity. Data reporting requirements for field studies should be equivalent to laboratory testing so results can be compared. Application of the modeling frameworks can provide approaches for extrapolating quantitative data from controlled laboratory exposures to dynamic field conditions.

4.2. Photo-induced toxicity models

Diamond (2003), and Marzooghi et al. (2017) reviewed the history and development of photosensitization modeling from the initial investigations of the early 1900s into the carcinogenicity of oil substances when exposed to ultraviolet light, through the expansion of model parameters over the decades. Early investigations used single compounds in conjunction with single wavelength exposures. Studies in the 1970s and 1980s made it clear that photosensitization potential differed among compounds by their specific absorption spectra as well as the quantity of light available to be absorbed, leading to the concept of relative photodynamic activity. Fig. 2 illustrates the evolution of photo-induced toxicity modeling.

Early attempts to develop quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) models for PAC photosensitivity relied on the Highest energy Occupied Molecular Orbital and its Lowest energy Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO-LUMO) band gap to predict phototoxic potential. In the 1980s the concept of photochemical reciprocity, first developed in the 19th century by Bunsen and Roscoe (1863), was incorporated into photo-induced toxicity models, allowing for the prediction of photo-induced toxicity of mixtures of PACs with varying amounts of light and compounds. Further refinement came with the direct measurement of tissue concentrations in relationship with observed photo-induced toxicity at known light intensities and durations. This work also produced compound-specific relative potencies. Photosensitization models since the 1990s have converged on the conceptual framework of photo-induced toxicity being a product of photodynamic compound tissue concentrations rather than aqueous, light dosing in those same tissues, and the molecular properties of the compound(s) (i.e., ring structure, substitutions, stability, and specific light absorption spectrum). More work is needed to develop relevant data investigating factors controlling organism sensitivity and the capability of organisms to recover from phototoxic exposures varying in periodicity and intensity.

Two established models of photosensitization are the anthracene relative model (Sellin-Jefferies et al., 2013), and the phototoxic target lipid model (Marzooghi et al., 2018), each having different data input needs and arrays of assumptions. Model choice is often limited to data availability. There is a need for more research to facilitate incorporation of these photosensitization models into oil toxicity models (e.g., PETROTOX). Photomodification modeling is far less developed than photosensitization. Models incorporating photomodification require more data on the direct linkage between irradiation of oil substances and the formation of specific photoproducts, which is a significant limitation for their implementation into the fate and effects models.

4.3. Predictive modeling needs

The CROSERF review by French-McCay et al. (2023) highlights current needs for model development including those applicable to photo-induced toxicity. Oil spill fate and effects models may be used to integrate fate processes (i.e., oil compound partitioning, evaporation, dissolution, and others) to predict exposures and toxicity of oil components under field conditions, providing the means for including photosensitization and photomodification data from standardized tests. Furthermore, an interconnected framework could provide a basis for evaluating the occurrence and relative importance of photosensitization or photomodification under different conditions.

One of the objectives of this document was to provide guidance on how to generate photo-induced toxicity data that would support future model development and validation. Additionally, incorporation of photo-induced toxicity into decision frameworks for oil spill response would allow for consideration of potentially enhanced toxicity in the water column. The factors that control photosensitization are recognized in scientific literature and have existing model frameworks to organize the experimental design and data interpretation. Issues specific to photo-induced toxicity include characterization of the intensity and wavelength distribution of the light sources used in laboratory and field studies. There are approaches to estimate the availability of sunlight at depths from field radiometer data (Barron et al., 2000; Barron et al., 2008; Neilsen et al., 2018), by remote sensing (Werdell and Bailey, 2005), and by models using remote sensing as inputs (Barron et al., 2009; Smyth, 2011; Lee et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021). Additional research is needed on incorporating complex and varying light intensity and spectra changes with depth as inputs into predictive environmental photo-induced toxicity models.

The direct linkage between irradiation of oil substances and the formation of specific photoproducts is not well characterized and is currently a significant limitation for implementation of photomodification into the integrated fate and effects models. Similarly, the toxic potency and relative toxicity of photomodified products (e.g., oxy-hydrocarbons) have not been extensively studied, and there remains substantial knowledge gaps on their chemical and physical properties including solubility, volatility, and degradation rates. While future research should continue to develop models to predict formation and lability of photo-oxidation products, this is challenging as the range of photo-oxidation products is as complex as the underlying hydrocarbon chemistry and will include small, soluble molecules to large, insoluble molecules. An interim goal could be to focus on blocks (see Section 4.1) of photo-oxidation products that are relevant for toxicity assessments. Another challenge is the relationship of photon wavelength to structure-specific photomodification. The visible portion of the spectrum appears to have a greater influence on photomodification than in photosensitization (e.g., Freeman and Ward, 2022). Future studies might focus on filling these data gaps as longer wavelengths of light penetrate deeper into the water column which may be important to capture in photomodification models (i.e., photomodification of surface sediment associated petroleum substances and oil droplets at depths greater than the penetration of UV light). Addressing these gaps has direct implications for hazard assessment and modeling.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The set of recommendations for conducting photo-induced toxicity studies herein are intended to create consistency among researchers to maximize the utility of experimental results that can be used in comparisons across studies and hazard assessments and integrated into tools and effects models used to support oil spill response and planning, and natural resource damage assessments. Following a set of guidelines and considerations when designing photo-toxicity studies should result in improvement of protocols and the quality of information produced in this field.

This review provides minimum requirements for petroleum and light treatment levels, test duration, controls, compound equilibration periods, resting periods, light exposure duration, light measurements, and endpoints (Table 1), including reporting recommendations for data consistency and utility (Table 2). A summarization of considerations is provided to encapsulate the basic requirements and aspects in designing a photo-induced toxicity study. When conducting toxicity testing in support of oil spill assessments, a characterization of environmentally relevant field conditions in the impacted area should be assessed to determine relevant test organisms, light exposures and intensity ranges, water quality information, and the appropriate oil preparation methods.

Photo-induced toxicity studies to date have been instrumental in developing a set of guidelines that can be used to assist researchers in answering hypothesis driven questions related to phototoxic risk and appropriate test design. Photo-induced toxicity studies will continue to evolve as more in-depth research examines individual molecules that drive photo-induced toxicity and as more information is provided on environmentally relevant exposure scenarios. The complexity of oils will continue to lead to uncertainties when attempting to characterize individual contributions of oil-based chemicals to overall toxicity, especially under a transient environment in which solar irradiation transforms individual molecules. There is a need to identify and characterize the toxicity of oil-based compounds with substituted functional groups as well as photoproducts from oxidation during light exposure, which will improve our understanding of the drivers of toxicity and the dynamics of light exposure as it relates to changes in the chemical content of oil.

This paper provides guidance on the necessary components to conduct a photo-induced toxicity study and minimum data reporting requirements, representing an important step towards the standardization of photo-induced toxicity studies. The incorporation of these recommendations into future photo-induced toxicity studies would ultimately harmonize study results making them more consistent and usable in efforts related to oil spill hazard and risk assessments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been subjected to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency review and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents reflect the views of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This project was supported in part by an appointment M. Alloy to the Research Participation Program at the Office or Research and Development, US Environment Protection Agency, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an inter-agency agreement between the US Department of Energy and EPA.

Funding sources

This work was supported through the Government of Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans Multi-Partner Research Initiative. The authors were not compensated for their contributions to this work.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Matthew M. Alloy: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Bryson E. Finch: Writing – original draft. Collin P. Ward: Writing – original draft. Aaron D. Redman: Writing – original draft. Adriana C. Bejarano: Writing – original draft. Mace G. Barron: Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2022.106390.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Aeppli C, Swarthout RF, O’Neil GW, Katz SD, Nabi D, Ward CP, Nelson RK, Sharpless CM, Reddy CM, 2018. How persistent and bioavailable are oxygenated Deepwater Horizon oil transformation products? Environ. Sci. Technol 52 (13), 7250–7258. 10.1021/acs.est.8b01001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aeppli C, Carmichael CA, Nelson RK, Lemkau KL, Graham WM, Redmond MC, Valentine DL, Reddy CM, 2012. Oil weathering after the Deepwater Horizon disaster led to the formation of oxygenated residues. Environ. Sci. Technol 46, 8799–8807. 10.1021/es3015138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy MM, Boube I, Griffitt RJ, Oris JT, Roberts AP, 2015. Photo-induced toxicity of Deepwater Horizon slick oil to blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) larvae. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 34 (9), 2061–2066. 10.1002/etc.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy M, Baxter D, Stieglitz J, Mager E, Hoenig R, Benetti D, Grosell M, Oris J, Roberts A, 2016. Ultraviolet radiation enhances the toxicity of Deepwater Horizon oil to mahi-mahi (Coryphaena hippurus) embryos. Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 2011–2017. 10.1021/acs.est.5b05356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy M, Garner TR, Neilsen K, Mansfield C, Carney M, Forth H, Krasnec M, Lay C, Takeshita R, Morris J, 2017. Co-exposure to sunlight enhances the toxicity of naturally weathered Deepwater Horizon oil to early lifestage red drum (Sciaenops ocellatus) and speckled seatrout (Cynoscion nebulosus). Environ. Toxicol. Chem 36, 780–785. 10.1002/etc.3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASTM, 2014. Standard Guide for Conducting Acute Toxicity Tests on Test Materials with Fishes, Macroinvertebrates, and Amphibians. ASTM International, Philadelphia, PA, USA. 10.1520/E0729-96R14. ASTM E 729–96. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aurand D, Coelho G, 2005. Cooperative aquatic toxicity testing of dispersed oil and the “Chemical response to Oil Spills: Ecological Effects Research Forum (CROSERF)”. Technical Report. EM&A Inc., Lusby, MD, p. 79. Technical Report 07–03, 105 pages + Appendices. Downloaded from the archives of the Bureau of Safety and Evironmental Enforcement (BSEE) https://www.bsee.gov/sites/bsee.gov/files/osrr-oil-spill-response-research/296ac.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Baker KS, Smith RC, Green AES, 1980. Middle ultraviolet radiation reaching the ocean surface. Photochem. Photobiol 32 (3), 367–374. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1980.tb03776.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, Hoffman DJ, Rattner BA, Burton GA, Cairns J, 1995. Bioaccumulation and bioconcentration in aquatic organisms. Handbook of Ecotoxicology. Lewis Publ., Boca Raton, pp. 652–666 eBook ISBN 9780429137464. [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, Podrabsky T, Ogle S, Ricker RW, 1999. Are aromatic hydrocarbons the primary determinant of petroleum toxicity to aquatic organisms? Aquat. Toxicol 46 (3–4), 253–268. 10.1016/S0166-445X(98)00127-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, 2007. Sediment-associated phototoxicity to aquatic organisms. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess 13 (2), 317–321. 10.1080/10807030701226285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, 2017. Photoenhanced toxicity of petroleum to aquatic invertebrates and fish. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 73, 40–46. 10.1007/s00244-016-0360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, Vivian D, Yee SH, Diamond S, 2008. Temporal and spatial variation in solar radiation and photoenhanced toxicity risks of spilled oil in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 27, 227–236. 10.1897/07-317.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, Ka’aihue L, 2003. Critical evaluation of CROSERF test methods for oil dispersant toxicity testing under subarctic conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull 46, 1191–1199. 10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, Little EE, Calfee RD, Diamond S, 2000. Quantifying solar spectral irradiance in aquatic habitats for the assessment of photoenhanced toxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 19, 920–925. 10.1002/etc.5620190419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron MG, Vivian DN, Yee SH, Santavy DL, 2009. Methods to estimate solar radiation dosimetry in coral reefs using remote sensed, modeled, and in situ data. Environ. Monit. Assess 151, 445–455. 10.1007/s10661-008-0288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano AC, Adams JE, McDowell J, Parkerton TF, Hanson ML., 2023. Recommendations for improving the reporting and communication of aquatic toxicity studies for oil spill planning, response, and environmental assessment. Aquat. Toxicol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benigni P, Sandoval K, Thompson CJ, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Gardinali P, Fernandez-Lima F, 2017. Analysis of photoirradiated water accommodated fractions of crude oils using tandem TIMS and FT-ICR MS. Environ. Sci. Technol 51 (11), 5978–5988. 10.1021/acs.est.7b00508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem R, Karran P, 2012. Multiple forms of DNA damage caused by UVA photoactivation of DNA 6-thioguanine. Photochem. Photobiol 88 (1), 5–13. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunsen RW, Roscoe HE, 1863. VII. Photo-chemical researches.—Part V. On the direct measurement of the chemical action of sunlight. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond Vol. 153, pg. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Burwood R, Speers GC, 1974. Photo-oxidation as a factor in the environmental dispersal of crude oil. Estuar. Coast. Mar. Sci 2 (2), 117–135. 10.1016/0302-3524(74)90034-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calfee RD, Little EE, Cleveland L, Barron MG, 1999. Photoenhanced toxicity of a weathered oil on Ceriodaphnia dubia reproduction. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 6, 207–212. 10.1007/BF02987329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins J, Thordardottir T, 1980. The ecological significance of solar UV radiation on aquatic organisms. Nature 283 (5747), 563–566. 10.1038/283563a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cartolano MC, Alloy MM, Milton E, Plotnikova A, Mager EM, McDonald MD, 2021. Exposure and recovery from environmentally relevant levels of waterborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from Deepwater Horizon oil: effects on the gulf toadfish stress axis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 40 (4), 1062–1074. 10.1002/etc.4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Oris JT, 2000. Anthracene photoinduced toxicity to plhc-1 cell line (Poeciliopsis lucida) and the role of lipid peroxidation in toxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 19, 2699–2706. 10.1002/etc.5620191113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahms HU, Lee JS, 2010. UV radiation in marine ectotherms: molecular effects and responses. Aquat. Toxicol 97 (1), 3–14. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damare LM, Neilsen KN, Alloy MM, Curran TE, Soulen BK, Forth HP, Lay CR, Morris JM, Stoeckel JA, Roberts AP, 2018. Photo-induced toxicity in early life stage fiddler crab (Uca longisignalis) following exposure to Deepwater Horizon oil. Ecotoxicology 27, 440–447. 10.1007/s10646-018-1908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman H, Wade TL, French-McCay DP, Bejarano AC, Hollebone BP, Faksness L, Mirnaghi FS, Yang Z, Loughery JR, Pretorius T, de Jourdan B, 2023. Recommendations for the advancement of oil-in-water media and source oil characterization in aquatic toxicity studies. Aquat. Toxicol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond SA., Helbling EW, Zagarese H, 2003. Photoactivated toxicity in aquatic environments. UV Effects in Aquatic Organisms and Ecosystems. The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK, pp. 219–250. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta TK, Harayama S, 2000. Fate of crude oil by the combination of photooxidation and biodegradation. Environ. Sci. Technol 34 (8), 1500–1505. 10.1021/es991063o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury CL, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM, 1997. Effects of simulated solar radiation on the bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by the duckweed Lemna gibba. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 16, 1739–1748. 10.1002/etc.5620160824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fasnacht MP, Blough NV, 2002. Aqueous photodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ. Sci. Technol 36 153 (20), 4364–4369. 10.1021/es025603k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BE, Marzooghi S, Di Toro DM, Stubblefield WA, 2017. Evaluation of the phototoxicity of unsubstituted and alkylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to mysid shrimp (Americamysis bahia): validation of predictive models. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 36, 2043–2049. 10.1002/etc.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BE, Stubblefield WA, 2016. Photo-enhanced toxicity of fluoranthene to Gulf of Mexico marine organisms at different larval ages and ultraviolet light intensities. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 35, 1113–1122. 10.1002/etc.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BE, Stefansson ES, Langdon CJ, Pargee SM, Blunt SM, Gage SJ, Stubblefield WA, 2016. Photo-enhanced toxicity of two weathered Macondo crude oils to early life stages of the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Mar. Pollut. Bull 113 (1–2), 316–323. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freegarde M, Hatchard CG, Parker CA, 1971. Oil spilt at sea: its identification, determination, and ultimate fate. Lab. Pract 20 (1), 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman DH, Ward CP, 2022. Sunlight-driven dissolution is a major fate of oil at sea. Sci. Adv 8 (7), eabl7605. 10.1126/sciadv.abl7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French McCay DP, 2002. Development and application of an oil toxicity and exposure model, OilToxEx. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 21 (10), 2080–2094. 10.1002/etc.5620211011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French-McCay DP, 2003. Development and application of damage assessment modeling: example assessment for the North Cape oil spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull 47 (9–12), 341–359. 10.1016/s0025-326X(03)00208-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French-McCay DP, 2004. Oil spill impact modeling: development and validation. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 23 (10), 2441–2456. 10.1897/03-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French-McCay DP, Parkerton TF, de Jourdan B, 2023. Bridging the lab to field divide: advancing oil spill biological effects models requires revisiting aquatic toxicity testing. Aquat. Toxicol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensemer RW, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM, 1998. Amelioration of the photo-induced toxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by a commercial humic acid. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf 39 (1), 57–64. 10.1006/eesa.1997.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]