Abstract

Background:

Community pharmacies in the United States are beginning to serve as patient care service destinations addressing both clinical and health-related social needs (HRSN). Although there is support for integrating social determinant of health (SDoH) activities into community pharmacy practice, the literature remains sparse on optimal pharmacy roles and practice models.

Objective:

To assess the feasibility of a community pharmacy HRSN screening and referral program adapted from a community health worker (CHW) model and evaluate participant perceptions and attitudes toward the program.

Methods:

This feasibility study was conducted from January 2022 to April 2022 at an independent pharmacy in Buffalo, NY. Collaborative relationships were developed with three community-based organizations including one experienced in implementing CHW programs. An HRSN screening and referral intervention was developed and implemented applying a CHW practice model. Pharmacy staff screened subjects for social needs and referred to an embedded CHW, who assessed and referred subjects to community resources with as-needed follow-up. Post intervention, subjects completed a survey regarding their program experience. Descriptive statistics were used to report demographics, screening form, and survey responses.

Results:

Eighty-six subjects completed screening and 21 (24.4%) an intervention and referral. Most participants utilized Medicaid (57%) and lived within a ZIP Code associated with the lowest estimated quartile for median household income (66%). Eighty-seven social needs were identified among the intervention subjects, with neighborhood and built environment (31%) and economic stability challenges (30%) being the most common SDoH domains. The CHW spent an average of 33 minutes per patient from initial case review through follow-up. All respondents had a positive perception of the program, and the majority agreed that community pharmacies should help patients with their social needs (70%).

Conclusions:

This feasibility study demonstrated that embedding a CHW into a community pharmacy setting can successfully address HRSN and that participants have a positive perception toward these activities.

Community pharmacies in the United States play a major role in public health and have opportunities to address disparities in health care delivery.1,2 Their close location to at-risk groups, including individuals in rural areas or with lower socioeconomic status, and their strong relationships with patients make pharmacies ideal locations for patient-centered services.2–5 Community pharmacy practice is expanding, with pharmacies pioneering innovative services and providing team-based patient care services to their communities.5,6 Pharmacy services have primarily focused on clinical interventions such as immunizations, point-of-care testing, and chronic disease management.1,7 As health care moves toward whole-person care, community pharmacies are beginning to serve as patient care service destinations addressing both clinical and health-related social needs (HRSNs).8,9

Recently, the American Pharmacists Association House of Delegates adopted a policy statement focusing on social determinants of health (SDoH) that supports the integration of SDoH screening into pharmacy services and encourages the integration of community health workers (CHWs) into pharmacy practice.10 A recent American Society of Health Systems Pharmacists statement provided additional support for pharmacists’ roles in public health and in addressing SDoH.7 Although there is organizational support for integrating SDoH activities into pharmacy practice, there is only sparse literature on pharmacy roles and the most suitable practice models. For example, a community pharmacy in Iowa screened patients with complex medication regimens for unmet social needs.11 The pharmacists conducted verbal SDoH screening and used motivational interviewing to identify unmet social needs and to evaluate subjects’ medication regimens. This study helped to show that community pharmacies have an opportunity to deliver social needs screening given their unique position in the community and relationship with their patients. In 2019, Humana, working with OutcomesMTM, completed a SDoH screening study in 2162 pharmacies and reported significant reductions in average medical spending and a total net decrease in per member spending.12 In another example, CVS pharmacies, working with Aetna and supported by the Unite Us platform, completed the HealthTag program in 47 stores, with the results of the pilot program still awaited.13 The limited information about these programs makes it difficult to infer program success and whether expansion would be valuable, and even less is known about SDoH programs and activities in other pharmacy practice settings. Livet et al. performed an exploratory study in four primary care clinics in rural and underserved North Carolina communities that evaluated the expansion of comprehensive medication management to include SDoH support.14 The pharmacist identified and addressed 26 unresolved COVID-prompted SDoH concerns in 66 patients. More information are clearly needed regarding pharmacy practice models that address social needs.

We previously described two SDoH practice models implemented within community pharmacy settings.15,16 Briefly, the first model was the SDoH specialist model, implemented in Community Pharmacy Enhanced Services Network (CPESN) New York pharmacies, where a pharmacy staff member was selected as the main program facilitator and was given additional training in the five SDoH domains. This individual was then involved with the development, implementation, and oversight of the pharmacy’s SDoH program. The second was a CHW model, implemented in a CPESN Missouri pharmacy, where a pharmacy technician obtained CHW certification and became the program’s main facilitator. The technician-CHW was the point person within the pharmacy and with any patients completing social needs screening. Although these studies provided important information regarding novel community pharmacy social needs programs, additional insights are needed on these models to better define pharmacy’s role. Therefore, our next step was to develop and test an SDoH screening and referral program in Western New York (WNY) with the goal of collecting information regarding community engagement, intervention development and implementation, and patient satisfaction within a pharmacy-driven social needs screening program. The objectives of this study were to: 1) assess the feasibility of a community pharmacy social needs screening and referral program, adapting the CHW model and 2) evaluate participant perceptions and attitudes toward a community pharmacy HRSN screening program.

Methods

Study design, setting, and community-based participation

This feasibility study was conducted over 12 weeks from January 2022 to April 2022 at an independent pharmacy in Buffalo, NY. The pharmacy was affiliated with the CPESN and was located in an urban setting with a high social vulnerability index (0.83).17,18 The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention developed the social vulnerability index to determine the social vulnerability of each census tract using 14 social factors.19 These factors link directly to SDoH such as socioeconomic status, household composition, and housing or transportation status. The participating pharmacy provides several clinical services to the community including retail and institutional prescription services, durable medical equipment, and specialty compounded prescriptions. These services are supported by 3 pharmacists, 7 pharmacy technicians, and 3 additional pharmacy staff members. The University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board approved this study (approval #5903).

Collaborative relationships were developed with three community-based organizations (CBOs) during program development, which were vital for program success. First, the Community Network for Engagement, Connection, and Transformation (CoNECT) provided CHW training to select pharmacy and research staff. The training included techniques on effective communication and working as collaborative partners to assist individuals with specific social needs. Next, we worked with the Buffalo Urban League (BUL), which is a historic civic rights and urban advocacy organization serving the Buffalo community. BUL has extensive experience in developing and implementing CHW programs within the Buffalo community. Finally, we teamed up with a local health care organization that provided an IT referral platform (Holon) between the pharmacy and select local CBOs.

Participants

Participants were patients presenting to the pilot pharmacy and willing to complete a social needs screening form. Inclusion criteria were age 18 or older, English speaking, and able to provide consent to participate. The pharmacy recruited participants between January 2022 and March 2022 with an additional 2 weeks provided for intervention follow-up.

Intervention

The interdisciplinary social needs intervention followed a multistep approach aligned with the CPESN care model workflow (identify, screen, assess, refer, and follow-up). Each step of the intervention and related workflow is provided in Supplementary Figure 1. First, a screening form was adapted from the Health Leads Social Needs Screening Tool.20 This 12-question screening tool encompasses all five SDoH domains (economic stability; education access and quality; health care access and quality; neighborhood and built environment; and social and community context) and has previously been applied in community pharmacy settings. Buffalo Pharmacies staff within the retail pharmacy and durable medical equipmentdepartments were trained to ask subjects whether they were interested in completing social needs screening. Potential participants provided consent and completed the screening tool. As part of the form, the participant indicated if they would like to receive assistance for any of the needs identified within the tool. The screening form was then passed to the CHW within the pharmacy. Each week, a CHW would come to the pharmacy during a designated four-hour period to navigate patient cases. At the pharmacy, the CHW would review completed screening forms from the previous week and then develop a plan for patient follow-up. The CHW would reach out to participants telephonically for further assessment and determine whether an unmet social need required referral to a local community organization. Typically, subjects had multiple social needs, so a shared decision-making approach was undertaken to prioritize social needs. Referral resources were mainly sent to the participant by mail, along with a patient-friendly written action plan. These local CBOs and resources were selected from the United Way 211 platform, which is a comprehensive source of information about both local and national social resources and services. The alternative referral IT platform, Holon, was utilized for referrals if a patient was already part of a local accountable care organization (ACO) connected with Holon. Once the referral was sent from the CHW via Holon to the ACO, an ACO caseworker would assist the patient in addressing their social health needs. The action plan was a patient-friendly summary of prioritized social needs, information for the referral organizations, and an anticipated follow-up date. The CHW followed up with the participant regarding their outreach to the referral organizations within one to 2 weeks of the initial patient interaction.

The intervention was adaptive during the study period based on patient and pharmacy needs. For instance, one of the screening form questions asked about interpersonal safety. Given the urgency related to this question, a designated pharmacy staff member was assigned to review the screening forms daily to check if a participant answered “yes” and also marked that they would like to receive assistance. If this occurred, the pharmacy staff member would alert the CHW and pharmacy staff utilizing an on-call protocol. The team included trained staff with experience working with individuals that may have personal safety concerns, such as domestic violence or relationship abuse. Those team members acted as the point person for contact and interaction for any safety concerns.

Participant perception and attitudes survey

The pharmacy team followed up with participants by telephone during a 4-week period after the intervention was completed. Participants were asked to complete a survey about their experience of the social needs screening and referral program. Preliminary survey items were developed from a previous survey that evaluated patient attitudes toward social needs screening in a large integrated health system.21 Changes were made to ensure questions were pertinent to a community pharmacy setting. Additional questions were developed in an iterative process and included their experience with the community pharmacy social needs screening program and their attitudes toward a community pharmacy addressing social needs. The final survey instrument included twelve 5-point Likert scale items.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report patient demographics and screening form responses. Social needs identified on the screening forms were related back to the five SDoH domains as defined by Healthy People 2030 and the specific social condition within those domains. The identified social needs were linked to the applicable HRSN Z code. The Z codes are a subset of International Classifications of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes specific to assessing social needs, introduced in 2015.22 To assess the program’s reach within the WNY area, we performed a geospatial analysis that identified the frequency of completed screening forms based on ZIP Code and its related annual median household income using U.S. Census data.23,24 Survey responses were provided descriptively, and the 5-point Likert scale was merged into the following three categories: agree, neutral, and disagree. Analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and geospatial mapping was completed using Tableau Desktop – Public Edition 2022 (Salesforce, Seattle, WA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of total screened participants (n = 86) and those that completed an intervention and referral (n = 21) are included in Table 1. For participants completing the screening process, the average age was 50 ± 18 years, with a majority identifying as female (73%) and Black (63%). Most participants utilized Medicaid (57%) and lived within a ZIP Code that had the lowest estimate quartile for median household income (66%). For participants that completed the intervention and referral process, characteristics were similar except a higher percentage used Medicaid and they were more likely to be in a ZIP Code within the lower income quartile (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the screened and intervention participants

| Characteristics | All screened participantsa No. (%) |

Intervention participantsb No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| n = 86 | n = 21 | |

|

| ||

| Age, mean ± SD | 50 ± 18 | 51 ± 17 |

| 18–64 | 63 (73.3) | 17 (81.0) |

| >65 | 19 (22.1) | 4 (19.0) |

| Unknown | 4 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 63 (73.3) | 18 (85.7) |

| Male | 15 (17.4) | 2 (9.5) |

| Unknown | 8 (9.3) | 1 (4.8) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 54 (62.8) | 15 (71.4) |

| White | 11 (12.8) | 1 (4.8) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 (1.2) | 1 (4.8) |

| Multiracial | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 19 (22.1) | 4 (19) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 45 (52.3) | 10 (47.6) |

| Divorce | 14 (16.3) | 2 (9.5) |

| Separated | 12 (14.0) | 3 (14.3) |

| Widowed | 7 (8.1) | 2 (9.5) |

| Married | 5 (5.8) | 2 (9.5) |

| Unknown | 3 (3.5) | 2 (9.5) |

| Insurance type | ||

| Medicaid | 49 (57.0) | 17 (81.0) |

| Medicare | 8 (9.3) | 2 (9.5) |

| Commercial/private | 8 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 8 (9.3) | 2 (9.5) |

| No insurance | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 12 (14.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Annual median household income quartile by ZIP Codec | ||

| $1-$49,999 | 57 (66.3) | 15 (71.4) |

| $50,000–564,999 | 8 (9.3) | 3 (14.3) |

| $65,000–585,999 | 4 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| > $86,000 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (4.8) |

| Unknown | 16 (18.6) | 2 (9.5) |

Abbreviation used: SVI, social vulnerability index; SD, standard deviation.

Participants that were screened and completed a screening form.

Participants that had an intervention based upon shared decision-making between the subject and a community health worker.

Quartiles were determined from the Health care Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) - 2020 quartile classification system for annual median household income. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/.

Participants completing the social needs screening process

A total of 232 social needs were initially identified among the 86 screened participants (Table 2). Common SDoH domains identified by participants included economic stability challenges (29%), neighborhood and built environment challenges (24%), and healthcare access and quality challenges (17%). Among the 86 subjects that completed a screening form, 42 (49%) indicated that they wanted assistance in addressing their social need. The CHW followed up with these subjects and, after a one-on-one discussion, it was determined that 21 subjects required a SDoH intervention and referral. Common reasons for the subjects not receiving an intervention included: unable to contact the subject after three attempts (n = 9), subject was already resolving their social need appropriately and did not require further assistance (n = 8), and lack of a working phone number or did not require any further assistance (n = 4).

Table 2.

Participant responses to the screening form categorized by social determinant of health domain

| Healthy people 2030 social determinant of health Domain | Social need | All screened participants (n =

86) |

Intervention participants (n =

21) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | ||

|

| |||||||

| Economic stability | Food | 29 (33.7) | 54 (62.8) | 3 (3.5) | 10 (47.6) | 11 (52.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Utilities | 23 (26.1) | 59 (68.8) | 4 (4.7) | 12 (57.1) | 8 (38.1) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Employment | 15 (17.4) | 66 (76.7) | 5 (5.8) | 4 (19.0) | 17 (81.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Health care access and quality | Health literacy | 19 (22.8) | 62 (72.1) | 5 (5.8) | 5 (23.8) | 15 (71.4) | 1 (4.8) |

| Provider access | 18 (20.9) | 64 (74.4) | 4 (4.7) | 6 (28.5) | 15 (71.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Medical costs | 19 (22.1) | 63 (73.3) | 4 (4.7) | 4 (19.0) | 16 (76.2) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Neighborhood and built environment | Housing | 32 (37.2) | 49 (57.0) | 5 (5.8) | 18 (85.7) | 3 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Transportation | 29 (33.7) | 55 (64.0) | 2 (2.3) | 9 (42.9) | 12 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Social and community context | Safety | 15 (17.4) | 67 (77.9) | 4 (4.7) | 7 (33.3) | 14 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Daily activities | 25 (29.1) | 56 (65.1) | 5 (5.8) | 9 (40.9) | 13 (59.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Has an urgent needa,b | 8 (9.3) | 73 (84.9) | 5 (5.8) | 3 (14.3) | 18 (85.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Requests assistance for need(s)c | 42 (48.8) | 34 (39.5) | 7 (8.1) | 21 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

Abbreviation used: N/A, no response.

These questions were posed to allow patients to note the severity of their social needs and provide autonomy in seeking further help in addressing their social needs.

Urgent need was identified as a need that required immediate attention (eg, no food tonight or no place to sleep tonight).

Three participants (3.5%) responded not ready when asked if they would like to receive assistance.

Participants completing the social needs intervention and referral process

Twenty-one intervention subjects indicated a total of 87 social needs on the screening form (Table 2). The most common SDoH domains identified by the subjects were neighborhood and built environment challenges (31%) and economic stability challenges (30%). During the subject interview, the CHW applied a shared decision-making approach and confirmed 34 social need challenges that required a referral. Most subjects (84%) ultimately had one or two social needs that they were interested in resolving and required a referral. Many patients had a similar SDoH domain but a diverse set of social needs. We developed a visual representation of the interconnectedness between the SDoH domains and the unique social needs presented by the subjects (Supplementary Figure 2). For example, it was common for subjects to have housing issues but the specific social needs identified included homelessness, difficulty affording rent, and interpersonal concerns. The results for economic stability were similar, where subject cases included past due bills and challenges navigating government assistance. We further quantified these specific social needs and linked them to 11 applicable HRSN Z codes. Many of the 34 social needs addressed during the interventions mapped to a total of 63 Z codes (Supplementary Table 1). There were more Z code mappings than interventions as some of the social needs applied to more than one Z code. The most frequent Z codes included Z59.6 – Low Income (22, 35%) followed by Z59.7 – Inadequate Welfare Support (9, 14%). Community resources were identified, primarily using United Way 211, and the majority (75%) received referrals to one to two CBOs. Follow-up by the CHW was completed in 91% of cases, with no further assistance requested.

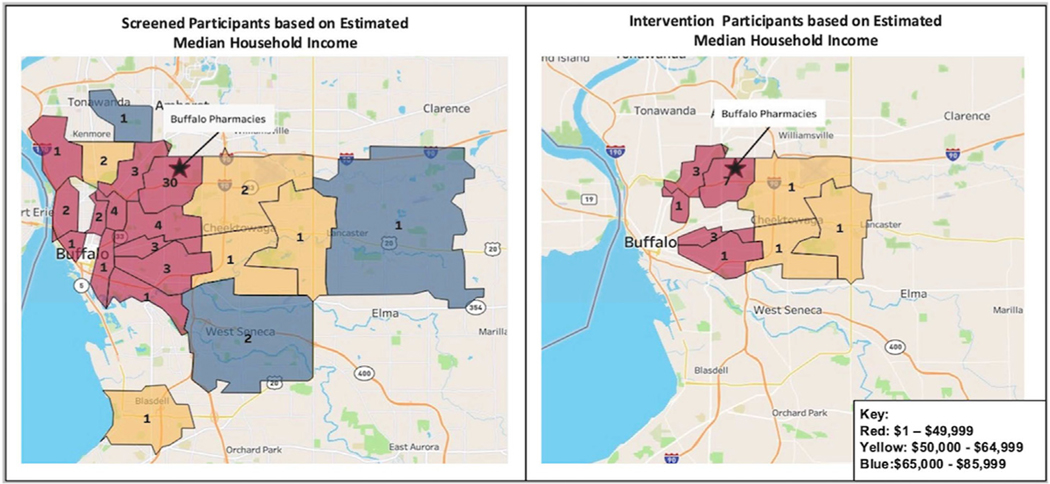

We further evaluated the program’s reach in the WNY community by completing a geospatial analysis stratifying based on screening and intervention subjects (Figure 1). Many patients completing the initial social needs screening form or intervention were within the same location as the pilot pharmacy. The program was able to reach individuals throughout the WNY community and primarily reach those in the city of Buffalo, where the income and socioeconomic status is estimated to be lower.

Figure 1.

Screening and intervention participants within the community pharmacy health-related social needs program by estimated annual median household income. The areas outlined are ZIP Code designations with the frequency of participants. Shading represents the annual median household income quartile for each ZIP Code as defined based on U.S. Census Bureau and AHRQ’s HCUP 2020 quartile classification system for annual median household income.

Social needs screening and referral program: Process measures

We evaluated the time spent by the CHW on each workflow step. Initial case review, which included assessing the patient’s screening form and preparing potential resources, took on average 7 ± 5.9 minutes per patient (n = 86). Initial patient screening and assessment, including discussing screening form responses and creating a shared decision care plan, took on average 12 ± 4.5 minutes (n = 42). Next, generating referrals, which involved the CHW writing out the individualized care plan summary and preparing the referral mailings, took on average 11 ± 5.7 minutes (n = 21). The follow-up calls to check in with patients regarding their social needs status were 3 ± 3.5 minutes long (n = 21). Overall, the CHW spent an average of 33 ± 13.2 minutes on the intervention per patient.

Participant attitudes and perceptions survey

Twenty-seven subjects completing a screening form participated in the survey, equating to a response rate of 31% (Table 3). Subjects that did not move forward to the intervention and referral part of the program completed a subset of applicable questions. All respondents that completed an intervention found the social needs program helpful, and most subjects felt comfortable discussing their social needs and concerns with pharmacy staff (88%). Most respondents would recommend the program to a family member or friend (83%). Interestingly, only half of respondents (52%) agreed that a pharmacy was a convenient place to talk about their social needs. However, almost all subjects supported pharmacies collecting social needs information to improve patient care (96%) and over two-thirds agreed that pharmacy should help patients with their social needs (70%).

Table 3.

Patient perceptions and attitudes survey results (N=27)

| Survey questions | No. of responsesa | Agree | Neutral | Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Participant perceptions and attitudes regarding their SDoH program experience | ||||

| Overall, I felt that the social health services offered were helpful. | 11 | 11 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| I felt that the social health program pharmacy staff were respectful of me when speaking about my social needs. | 23 | 21 (91.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) |

| I felt comfortable talking to pharmacy staff about my social needs and concerns. | 25 | 22 (88.0) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| I felt that Buffalo pharmacies provided a safe environment to talk about my social needs. | 25 | 22 (88.0) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| I was able to prioritize my social needs as part of the social health program. | 12 | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| I better understand that my social needs effect my wellbeing after participating in the social health program. | 11 | 11 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| I would recommend this program to a family member or friend. | 23 | 19 (82.6) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.7) |

| I felt that the social health program did its best to meet my social needs. | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (9.1) |

| I felt that the community organization I was referred to was able to address my social health needs. | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| Participant attitudes toward SDoH programs within community pharmacy | ||||

| A pharmacy is a convenient place for me to talk about my social needs. | 27 | 14 (51.9) | 6 (22.2) | 7 (25.9) |

| Pharmacies should help patients with their social needs. | 27 | 19 (70.4) | 5 (18.5) | 3 (11.1) |

| I support pharmacies collecting social needs information to improve care for their patients. | 27 | 26 (96.3) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviation used: SDoH, social determinants of health.

Questions were not all applicable to survey respondents if they did not request assistance or needed an intervention.

Discussion

This feasibility study demonstrated that a CHW can be embedded into a community pharmacy to address HRSN. The program’s success was primarily due to the pharmacy’s interest in developing patient-centered services focused on HRSN and the collaboration with local CBOs. A social needs screening workflow was adapted within the pharmacy, and the program champion was able to engage and motivate the pharmacy staff throughout the study period. Local CBOs provided CHW training to select staff and broader programmatic training to the pharmacy staff. Additionally, an experienced CHW guided our program staff on a weekly basis, which was instrumental to program success. Overall, the pharmacy program screened 86 subjects and referred 21 of them to community organizations for assistance with their social needs. Regarding service area of the program, the geospatial analysis revealed that a majority of subjects lived within low socioeconomic areas beyond just the pharmacy’s geographic area.

There is increasing recognition by the pharmacy community that social needs should be integrated into pharmacy practice; however, there remains a lack of evidence regarding applicable models. Our previous work described two community pharmacy practice models involving social needs screening within CPESN pharmacies.16 This project examined a similar CHW model, but the pharmacy workflow and involvement of community organizations differed from the initial models reviewed. First, an experienced CHW from a partner organization was directly involved in the program from development to implementation. We leveraged their experience in working with the community and knowledge of local resources. Second, the CHW team was at the pharmacy during a designated four-hour time block to navigate patient cases. The pharmacy staffs were responsible for screening subjects, and then each week the CHW team would review eligible subjects and troubleshoot where needed. We found that this approach was helpful to balance the CHW time but could still provide the pharmacy support in-person and virtually. Next, the CHW teams provided a list of local resources using the online platform United Way 211. This platform provided individuals and families with a list of social-related services within their locality. The importance of addressing HRSNs continues to grow, and pharmacy can play a major role. Community pharmacy has led the way in developing HRSN screening and referral programs, but more research is needed in other pharmacy settings. In addition, best practices and financial sustainability models need to be developed for widespread adaptability of pharmacy-based HRSN screening and referral programs

One financial consideration for pharmacies contemplating this model is external CHW labor costs. During this intervention, the external CHW spent an average of 33 ± 13.2 minutes per patient and was on site at the pharmacy 4 hours per week. Per the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the United States mean hourly wage for CHWs is $22.97.25 Therefore, the CHW’s wages for this intervention would have been approximately $91.88 per week or $4777.76 annually. Currently, a direct reimbursement method for addressing HRSN at pharmacies does not exist. One option for pharmacies to support CHW wages may be to partner with organizations focusing on value-based care and decreasing overall health care costs, including managed care organizations, ACOs, or state Medicaid programs. These organizations are beginning to recognize the importance of addressing social health and may be interested in partnering to support CHW wages for a social needs screening and referral program in the community pharmacy setting. A second option, pending staffing availability, would be to create a hybrid CHW-technician role, utilizing a current technician and their already-budgeted wages similar to the Missouri CHW model previously discussed.15 If this second option is chosen, it should be noted that there will need to be an investment from the pharmacy to train the technician as a CHW.

Pharmacy staff training is a vital component of a successful social needs screening and referral program, regardless of their specific program role. Social needs assessments deal with a wide range of complex factors, and staff may be uncomfortable discussing these sensitive topics. One specific area where pharmacy staff may require additional training is in addressing physical safety and interpersonal violence (IPV). We set up an educational session for our program staff with the YWCA, which is a nonprofit organization working to address racism and violence. The educational session provided an overview of the topic and discussed relevant scenarios and best practices for approaching this highly sensitive situation.

IPV is associated with a variety of physical and mental health consequences, and survivors have high rates of health care utilization.26,27 For our pilot, we developed a designated workflow for screenings that indicated physical safety or IPV concerns and were interested in receiving assistance. We had a designated IPV staff member that had extensive experience of working in domestic violence and personal safety concerns Furthermore, it should be noted that while the number of IPV interventions within this study was low, the impact should not be overlooked. This is due to efforts to provide educational awareness and allow patients to anonymously pick up IPV resources from the pharmacy counter. Therefore, more IPV concerns may have been addressed outside of the intervention. Lastly, it should be noted that simply asking an IPV question lets survivors know that violence is not condoned and that resources are available. Inclusion of personal safety questions is critical to a person’s overall health; however, additional training should be provided to increase confidence when responding to disclosures.

Currently, there is sparse literature on patients’ perceptions and attitudes toward a pharmacy social needs screening and referral program. Kiles et al. performed a qualitative study utilizing the principles of grounded theory and Charmaz’s approach to theory development in constructing the SDoH Patient Communication Framework.28 The researchers found that clearly providing the rationale as to why the pharmacy is conducting HRSN screening, and more particularly what is being done with this screening information, is the foundational step to successfully working with patients on resolving their SDoH.28 The next step is to create and maintain a positive working relationship between pharmacy staff and patients, as perceived by the patient.28 Overall, the participants of our intervention were positive about the services provided and felt comfortable discussing social needs and concerns with pharmacy staff. Almost all respondents supported pharmacies collecting social needs information to improve patient care. Addressing a patient’s social needs within community pharmacies is relatively new, and patient acceptability is a high priority for program success. Not only did patients feel comfortable speaking about their social needs but they also felt that the community pharmacy setting was a safe environment to discuss these delicate topics.

Based on participant feedback, areas of improvement may include whether pharmacies should help patients with their social needs (70% agree) and whether the pharmacy is a convenient place for these interactions (52% agree). This response is not surprising, given that this was a pilot program and pharmacies typically do not address these concerns in their day-to-day activities. Kiles et al. noted similar results, making resources and perceived benefit of a pharmacy HRSN screening program the third and final step of their communication framework.28 They found that the patients interviewed were more likely to have buy-in to a pharmacy HRSN screening program if they were aware that the pharmacy staff had resources available to help address their social needs.28 Community pharmacy practice is actively transforming, and pharmacies will need to continue to develop innovative programs that incorporate whole-person health care. Continuous feedback from participants will be required to ensure program success as these programs are developed and continue to expand.

This study had several limitations. First, this study was only 3 months long, which may not be long enough to evaluate patient social needs resolution or program sustainability. Most participants had complex circumstances that required multiple CBO referrals. Typically, social needs cannot easily be resolved and require longitudinal assistance and follow-up. In many cases, participants were unaware that resources were available and only required a soft hand-off in the form of informational materials. Moving forward, pharmacies should consider their program’s duration and consider involving other local organizations if further follow-up is needed. Another limitation is that we did not collect downstream health care utilization or economic endpoints. Most studies investigating social needs interventions have primarily focused on process or social outcomes rather than health or health care utilization outcomes.29 A next step will be to include clinical and economic outcomes within a larger study to further support community pharmacy social needs screening and referral programs. Finally, this program was implemented in a CPESN independent pharmacy in WNY. This limits the study’s generalizability, as findings may be different in other retail or chain pharmacies. However, given CPESN’s focus on enhancing services for high-risk patients, these pharmacies are ideal partners for a social needs pilot study.

Conclusions

This feasibility study demonstrated that embedding a CHW into a community pharmacy setting can be successful in addressing HRSN. The program was able to reach subjects throughout the Buffalo area, primarily in low socioeconomic areas. Community engagement including collaboration with local organizations was pivotal for program success, and pharmacy relationships with community organizations should be developed prior to implementing a social needs program. Participants had a positive perception and attitude toward a social needs pharmacy program and support pharmacies collecting social information to improve patient care. Moving forward, research is needed to evaluate the clinical and economic impact of providing pharmacy-based social needs services.

Supplementary Material

Key Points

Background:

As healthcare moves towards whole-person care, community pharmacies are beginning to serve as patient care service destinations addressing both clinical and HRSNs.

Although there is organizational support from APhA and ASHP for integrating SDoH activities into pharmacy practice, there is only sparse literature on pharmacy roles and the most suitable practice models.

Findings:

This HRSN screening and referral intervention applied a CHW practice model and leveraged new collaborative relationships with three community-based organizations.

Embedding a CHW into a community pharmacy setting successfully addressed HRSN and was found to especially assist low socioeconomic groups.

Participants had a positive perception and attitude towards a social needs pharmacy program and support pharmacies collecting social information to improve patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the pharmacy staff and patients of Buffalo Pharmacies for conducting and participating in this important pharmacy service project. They would also like to thank Grace Tate, Maribel Irizarry, and Ericka Townsend of BUL for providing their time and expertise as CHWs. In addition, they would like to acknowledge the CoNECT of Buffalo for providing community health worker training as well as Mary Brennan Taylor of the YWCA of the Niagara Frontier and Jennifer Stoll for providing IPV education to the pharmacy staff involved in this project.

Funding:

DMJ is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under award number K23HL153582. This study was supported by a pilot award from the University at Buffalo Clinical and Translational Science Institute through the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under award number UL1TR001412.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The author declares no conflicts of interest or financial interests in any product or service mentioned in this article.

Contributor Information

Amanda A. Foster, Postdoctoral Clinical Research Fellow, University at Buffalo School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Buffalo, NY.

Christopher J. Daly, University at Buffalo School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Buffalo, NY.

Richard Leong, Postdoctoral Clinical Research Fellow, University at Buffalo School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Buffalo, NY.

Jennifer Stoll, University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Department of Family Medicine, Buffalo, NY.

Matthew Butler, Pharmacy Department, Middleport Family Health Center, Middleport, NY.

David M. Jacobs, University at Buffalo School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Buffalo, NY.

References

- 1.Strand MA, DiPietro Mager NA, Hall L, Martin SL, Sarpong DF. Pharmacy contributions to improved population health: expanding the public health roundtable. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strand MA, Bratberg J, Eukel H, Hardy M, Williams C. Community pharmacists’ contributions to disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qato DM, Zenk S, Wilder J, Harrington R, Gaskin D, Alexander GC. The availability of pharmacies in the United States: 2007–2015. PLoS One. 2017;12(8), e0183172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Zenk SN, Qato DM. Assessment of pharmacy closures in the United States from 2009 through 2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluml BM, Watson LL, Skelton JB, Manolakis PG, Brock KA. Improving outcomes for diverse populations disproportionately affected by diabetes: final results of Project IMPACT: diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2014;54(5):477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly CJ, Verrall K, Jacobs DM. Impact of community pharmacist interventions with managed care to improve medication Adherence. J Pharm Pract. 2021;34(5):694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron G, Chandra RN, Ivey MF, et al. ASHP statement on the Pharmacist’s role in public health. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2022;79(5):388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly CJ, Costello J, Mak A, Quinn B, Lindenau R, Jacobs DM. Pharmacists’ perceptions on patient care services and social determinants of health within independent community pharmacies in an enhanced services network. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021;4(3):288–295. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly CJ, Quinn B, Mak A, Jacobs DM. Community pharmacists’ perceptions of patient care services within an enhanced service network. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020;8(3):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Social determinants of Health. American Pharmacists association house of delegates. Available at: https://www.pharmacist.com/Portals/0/PDFS/HOD/NBI%207%20-%20Social%20Determinants%20of%20Health_1.pdf?ver=ZPyZUI7fbpvE0kS8PYc_Vw%3D%3D . Accessed July 15, 2022.

- 11.Yard R Screening for unmet social needs: a conversation with a community pharmacist. Center for Health Care Strategies. Available at https://www.chcs.org/screening-for-unmet-social-needs-a-conversation-witha-community-pharmacist/. Accessed September 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markus D, Dean S. Tackling Social Determinants of Health by Levergaing Community Pharmacies in a National, Scalable Model. Alexandria, VA: Pharmacy Quality Alliance; 2020 Annual Meeting; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham G, Briscione R. Addressing social determinants of health at the phamacy. US News and World Report. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2020-11-18/addressing-social-determinants-of-health-at-the-pharmacy . Accessed September 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livet M, Levitt JM, Lee A, Easter J. The pharmacist as a public health resource: expanding telepharmacy services to address social determinants of health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2021;2:100032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster AA, Daly CJ, Logan T, et al. Addressing social determinants of health in community pharmacy: innovative opportunities and practice models. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(5):e48–e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster AA, Daly CJ, Logan T, et al. Implementation and evaluation of social determinants of health practice models within community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2022;62(4):1407–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Community pharmacy enhanced services network. Available at: https://www.cpesn.com/. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- 18.PolicyMap. Available at: https://buffalo.policymap.com/maps. Accessed May 20, 2022.

- 19.CDC/ATSDR social vulnerability index. Centers for disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html. Accessed April 15, 2022.

- 20.Health Leads. The health leads screening toolkit. Available at: https://healthleadsusa.org/resources/the-health-leads-screening-toolkit/. Accessed October 18, 2021.

- 21.Rogers AJ, Hamity C, Sharp AL, Jackson AH, Schickedanz AB. Patients’ attitudes and perceptions regarding social needs screening and navigation: multi-site survey in a large integrated health system. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1389–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Z codes utilization among Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries in 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-omh-january2020-zcode-data-highlightpdf.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2022.

- 23.United States census Bureau. Income. Available at: https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/income.html. Accessed May 18, 2022.

- 24.Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP). Agency for healthcare research and quality. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/. Accessed May 19, 2022. [PubMed]

- 25.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wages, may 2021: 21–1094 community health workers. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes211094.htm. Accessed January 3, 2023.

- 26.Elliott L Interpersonal violence: improving victim recognition and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):871–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(2):89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiles TM, Cernasev A, Leibold C, Hohmeier K. Patient perspectives of discussing social determinants of health with community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2022;62(3):826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A Systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(5): 719–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.