Abstract

Objective: The frontal QRS-T angle (fQRS-T) is associated with myocardial ischemia and ventricular arrhythmias. On the other hand, acute pulmonary embolism (APE) is a major risk factor for cardiac adverse events. This research aimed to determine whether the fQRS-T, a marker of ventricular heterogeneity, can be used to predict successful thrombolytic therapy in patients with APE.

Methods: This was a retrospective observational study. Patients diagnosed with APE and hospitalized in the intensive care unit between 2020 and 2022 were included in the research. A total of 136 individuals with APEs were enrolled in this research. The patients were divided into two groups: thrombolytic-treated (n=64) and non-treated (moderate to severe risk, n=72). An ECG was conducted for each patient, and echocardiography was performed.

Results: The mean age of the thrombolytic group was 58.2±17.6 years, with 35 females (55.1% of the group) and 29 males (44.9%). The non-thrombolytic group had a mean age of 63.1±16.2, with 41 females (56.5%) and 31 males (43.5%). Respiratory rate, heart rate, and fQRS-T were higher in the thrombolytic group, and oxygen saturation ratio and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were higher in the non-thrombolytic group (p=0.006, p<0.001, p=0.021; p<0.001, p=0.015, p<0.001, respectively). In the thrombolytic therapy group, comparing pre- and post-treatment ECG data revealed a statistically significant change in the fQRS-T value (p=0.019).

Conclusion: The fQRS-T may provide important clues for the successful treatment of APEs.

Keywords: hemodynamic instability, frontal qrs-t angle, echocardiography, thrombolysis, acute pulmonary embolism

Introduction

Acute pulmonary embolism (APE) is a life-threatening cardiovascular disease worldwide [1]. The incidence increases with advancing age [2]. Since it causes occlusion in the pulmonary vascular bed and causes mortality with right ventricular (RV) overload, diagnosis and treatment require urgency [3].

Dilatation in the ventricles due to afterload causes the remodeling of myocytes [4]. The resulting remodeling affects the cardiac conduction system and changes the cardiac axis. The QRS-T angle in the frontal plane (fQRS-T), which is the difference between the QRS and T axes, is a new indicator of ventricular repolarization diversity [5]. The increased fQRS-T score has been linked to adverse cardiac events [6].

In normotensive patients, anticoagulant therapy prevents thrombus growth and pulmonary embolism (PE) recurrence. In patients with hemodynamic instability, thrombolytic therapy should be administered to reduce PE-related mortality unless contraindicated [7,8]. Successful thrombolytic treatment has been described using transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) measurements, but there is no sufficient data regarding the relationship between ECG parameters and thrombolytic therapy.

This research aimed to reveal the effect of thrombolytic therapy on the fQRS-T and to determine its association with successful thrombolytic therapy.

Materials and methods

Study design and subject

This retrospective investigation was performed in a tertiary hospital. Patients diagnosed with APE and who were admitted to the intensive care unit between January 2020 and June 2022 were included in the research. A total of 136 patients with APE were enrolled in this research. Patients with submassive or massive PE were treated with thrombolytics. The patients were divided into two groups: thrombolytic-treated (n=64) and non-treated patients (moderate to severe risk, n=72). Patients with coronary artery disorders, active cancer, hyperthyroidism, mild or severe valve disease, heart failure, chronic renal failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congenital heart disease were excluded. Patients whose data were inaccessible and whose analysis was unsuccessful were excluded from this study. The local ethics committee (Gazi Yaşargil Training and Research Hospital) approved the study protocol (No: 2022-131). It adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki's ethical guidelines for human experimentation (date: 22/07/2022) (2013).

Study protocol

A 12-lead ECG was obtained using an electrocardiograph (model ECG-1350K, Nihon-Kohden Corporation) at a rate of 25 mm/s and an amplitude of 10 mm/mV. To digitize the existing ECGs, a scanner was used. At 400x magnification, two cardiologists calculated and analyzed the TpTe time. A significant and practically total agreement was observed between the analyses of the two cardiologists (κ=0.861). The QT interval and TpTe time for heart rate were adjusted using the Bazett formula. During ECG analysis, the QT interval, corrected QT (QTc) interval, QRS, and T axis were automatically identified and recorded. TTE was performed according to the American Society of Echocardiology [9]. The examinations were performed using a Philips ultrasonography device (EPIQ 7). Alteplase was administered as a thrombolytic agent. Alteplase (patients 65 kg or more) was given a 10 mg intravenous (IV) bolus, followed by a 90 mg IV infusion over 2 hours. In patients weighing less than 65 kg, the total dose was adjusted not to exceed 1.5 mg/kg. On average, a total of 10 mg IV bolus and 90 mg IV infusion doses (over 2 hours) were given. In combination with thrombolytics, a loading dose of 80 U/kg unfractionated heparin was administered intravenously, followed by an activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)-adjusted infusion of 18 U/kg/h according to the guidelines [10].

Definitions

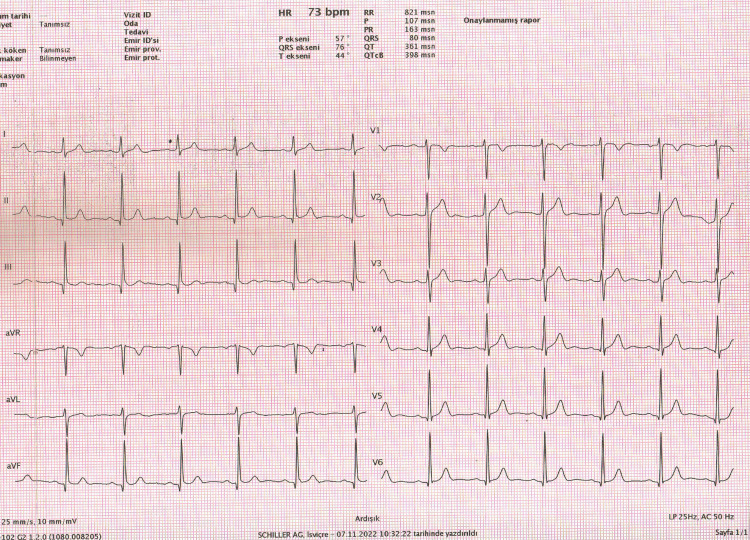

The fQRS-T is the angle formed by the difference between the QRS and T axes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Calculation of frontal QRS-T angle from automated surface ECG report.

Frontal plane QRS-T angle (fQRS-T)=QRS axis-T axis (QRS°-T°)=76°-44°=32°

When the angle surpassed 180 degrees, it was changed to the lowest possible angle (360 degrees). The fQRS-T was generated from automatically obtained ECG data.

The P dispersion (Pd) was calculated by subtracting the shortest P wave length from the longest P wave duration. The QT and QTc distributions were determined in the same method [11].

Massive PE is defined as acute PE with obstructive shock or systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mmHg. Submassive PE is acute PE without systemic hypotension (SBP≥90 mm Hg) but with either right ventricular (RV) dysfunction or myocardial necrosis [12].

Statistics

IBM SPSS software (version 24.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used for all the analyses. Initial continuous variables are shown as mean standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Applying Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, the normality distribution of the variables was determined. Categorical variables were represented with frequencies and percentages. Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was utilized for categorical variables. The Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous variables. If the p-value was less than 0.05, tests were judged statistically meaningful.

Results

The mean age of the thrombolytic group was 58.2±17.6 years, with 35 females (55.1% of the group) and 29 males (44.9%). The non-thrombolytic group had a mean age of 63.1±16.2, with 41 females (56.5%) and 31 males (43.5%). The baseline of the patients is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients.

Data are expressed as mean SD, number (percentage), or median (interquartile range) as appropriate.

DL: dyslipidemia; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; fQRS-T: frontal plane QRS-T angle.

| Thrombolytic group N=64 | Non-thrombolytic group N=72 | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 58.2±17.6 | 63.1±16.2 | 0.131 |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 35 (55.1) | 41 (56.5) | 0.712 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 10 (16.4) | 12 (16.8) | 0.866 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 5 (8.3) | 7 (9.8) | 0.628 |

| DL, n (%) | 8 (12.7) | 9 (12.8) | 0.910 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 10 (16.8) | 11 (15.7) | 0.821 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.3±0.6 | 36.3±0.3 | 0.869 |

| SatO2 (%) | 82.65±7.03 | 86.69±4.82 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate | 26.4±10.92 | 22±2.83 | 0.006 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 104.7±12.6 | 112.5±11.2 | 0.015 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 65.6±8.7 | 71.6±6.0 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 111.3±10.8 | 101.2±13.2 | <0.001 |

| fQRS-T (0) | 62.4±35.6 | 48.3±31.1 | 0.021 |

Respiratory rate, heart rate, and fQRS-T were higher in the thrombolytic group; oxygen saturation ratio and SBP and diastolic blood pressure were higher in the non-thrombolytic group (p=0.006, p<0.001, p=0.021; p<0.001, p=0.015, p<0.001, respectively). The RV TTE measurements demonstrated worsened RV functions in the thrombolytic group (p<0.05, Table 2).

Table 2. Echocardiographic measurements of the groups.

Data are expressed as mean SD, number (percentage), or median (interquartile range) as appropriate.

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LAD: left atrial diameter; RA: right atrium; TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; RVGLS: right ventricular global longitudinal strain; PASP: pulmonary artery systolic pressure.

| Thrombolytic group N=64 | Non-thrombolytic group N=72 | p-Value | |

| LVEF (%) | 52.1±5.6 | 55.3±6.2 | 0.568 |

| LAD (mm) | 39.2±3.8 | 40.2±3.6 | 0.783 |

| RA major diameter (mm) | 48.1±8.4 | 40.3±9.2 | <0.001 |

| RA minor diameter (mm) | 37.4±7.3 | 30.2±5.2 | <0.001 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 16.5±1.3 | 18.8±3.2 | <0.001 |

| RVGLS (%) | -11.2±2.3 | -15.3±2.8 | <0.05 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 55.1±12.9 | 39.2±15.1 | <0.001 |

Heart rate and fQRS-T demonstrated statistically significant group differences (p<0.05). Patients' electrocardiographic parameters were analyzed and evaluated (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparisons of ECG parameters before and after treatment.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and median (interquartile range).

Pd: P-wave dispersion; QTd: QT dispersion; QTcd: corrected QT dispersion; TpTe: T-peak to T-end; TpTec: corrected TpTe.

| Thrombolytic group N=64 | Non-thrombolytic group N=72 | |||||

| Before | After | p-Value | Before | After | p-Value | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 111.3±10.8 | 94.7±12.7 | <0.001 | 101.2±13.2 | 93.4±11.6 | 0.108 |

| Pd (ms) | 51.1±9.1 | 48.3±13.6 | 0.329 | 47.2±11.4 | 46.8±9.2 | 0.508 |

| QTd (ms) | 54.0±6.6 | 51.3±8.1 | 0.204 | 52.8±9.5 | 51.6±6.7 | 0.412 |

| QTcd (ms) | 68.6±8.1 | 66.0±8.8 | 0.214 | 66.8±6.4 | 65.9±7.1 | 0.387 |

| TpTe/QT | 0.2±0.04 | 0.2±0.02 | 0.786 | 0.2±0.06 | 0.2±0.03 | 0.674 |

| TpTe/QTc | 0.19±0.05 | 0.19±0.33 | 0.954 | 0.18±0.12 | 0.18±0.07 | 0.908 |

| fQRS-T (0) | 62.4±18.6 | 48.8±16.7 | 0.019 | 48.3±21.5 | 45.9±20.9 | 0.387 |

In the thrombolytic therapy group, comparing pre- and post-treatment ECG data revealed a statistically significant change in the fQRS-T value (p=0.019).

Discussion

This research revealed that the fQRS-T, which increased as a result of ventricular loading due to APE, decreased both clinically and statistically after successful thrombolytic therapy.

Thromboembolism causes an increasing afterload after dilatation in the right ventricle. The echocardiographic findings in our study support right ventricle dilatation in the thrombolytic group. Higher oxygen consumption is caused by shear stress in the ventricular wall, neurohormonal activation, and tachycardia [13]. Hypoxemia and hypotension may result in mortality [14]. There is neither a specific ECG finding to diagnose acute PE nor an ECG finding describing the effect and success of thrombolytic therapy. However, it can be expected that the change in the heart axis due to the enlargement of the right ventricle will be reflected in the ventricular repolarization parameters in the ECG recording.

In clinical practice, discovering novel ECG characteristics, such as fQRS-T, may be valuable for defining massive and submassive PE and predicting the effect and success of thrombolytic treatment in patients with APE. The fQRS-T, an indication of heterogeneity in ventricular activation and conduction, is the angle between ventricular depolarization and repolarization [15]. There are two methods for calculating the QRS-T angle. These are known as the spatial and fQRS-T, respectively. Calculating the spatial QRS-T angle is very difficult and requires advanced computer techniques [16]. In contrast, fQRS-T can be easily measured from the automatic report section of the ECG equipment and well matches the spatial QRS-T angle for risk calculation. Although there is no traditional upper limit for fQRS-T intervals, this value is often reported between 30 and 45 degrees [17]. Over the past decade, several observational studies have connected the QRS-T angle with sudden death and other fatal and pathological results [18,19]. Compared to electrocardiographic risk factors such as cQTd, a higher fQRS-T angle is recognized as a substantial and independent risk factor for adverse cardiac events [20].

In a study, fQRS-T was shown to be a predictor for mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome [21]. Gül et al. reported that the prognostic value of the fQRS-T in individuals with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTMI) and atrial arrhythmia was 81 degrees [22]. Colluoglu et al. stated that the fQRS-T was higher in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients with unsuccessful fibrinolytic therapy than in successful therapy [23]. Zehir et al. showed that individuals with sluggish coronary flow and fQRS-T >93 degrees were more likely to have arrhythmic events [24]. The fQRS-T estimates mortality in heart failure patients, as reported by Gotsman et al. [25]. Usalp et al. highlighted that the fQRS-T was raised in subclinical hypothyroidism individuals who developed arrhythmia [26]. On the other hand, Günlü et al. revealed that the fQRS-T was not associated with arrhythmia in individuals with vertigo, brucellosis, and fibromyalgia [27-30].

Limitations

The population of the study was small. In this study, the estimated fQRS-T values for both groups were observed to be lower than those previously reported in studies on cardiovascular disorders. This difference is due to the exclusion of participants with severe cardiovascular disease. The absence of a significant change in the frontal QRS-T angle in the non-thrombolytic patient group in the intensive care unit may be explained by the negligible effects of PE on the right ventricle or by the fact that the therapy had no impact on the right ventricle.

Conclusions

This research indicated that the fQRS-T is an important indicator of ventricular loading in patients with APE. However, the non-invasive and comprehensible fQRS-T method in clinical follow-ups may provide important clues for the successful treatment of APE. Adverse events could be prevented by using this novel marker.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Gazi Yaşargil Training and Research Hospital issued approval no 2022-131, dated July 7th, 2022. The local ethics committee approved the study. It adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki's ethical guidelines for human experimentation (2013).

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.Modified model for end-stage liver disease score predicts 30-day mortality in high-risk patients with acute pulmonary embolism admitted to intensive care units. İdin K, Dereli S, Kaya A, Yenerçağ M, Yılmaz AS, Tayfur K, Gülcü O. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2021;55:237–244. doi: 10.1080/14017431.2021.1876912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global burden of thrombosis: epidemiologic aspects. Wendelboe AM, Raskob GE. Circ Res. 2016;118:1340–1347. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kronik Obstrüktif Akciğer Hastalığı Ciddiyeti ile Sağ VentrikülStrain İlişkisi [Correlation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and right ventricular strain] Günlü S, Akkaya S, Polat C, Ede H, Öztur O. https://search.trdizin.gov.tr/yayin/detay/446195/ MN Kardiyol. 2021;28:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Excitation-contraction coupling and relaxation alteration in right ventricular remodelling caused by pulmonary arterial hypertension. Antigny F, Mercier O, Humbert M, Sabourin J. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;113:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Electrocardiographic QRS-T angle and the risk of incident silent myocardial infarction in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Zhang ZM, Rautaharju PM, Prineas RJ, Tereshchenko L, Soliman EZ. J Electrocardiol. 2017;50:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.QRS-T angle: a review. Oehler A, Feldman T, Henrikson CA, Tereshchenko LG. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2014;19:534–542. doi: 10.1111/anec.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comparison of tenecteplase versus alteplase in STEMI patients treated with ticagrelor: a cross-sectional study. Günlü S, Demir M. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;58:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1901647. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al. Circulation. 2011;123:1788–1830. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simple electrocardiographic markers for the prediction of paroxysmal idiopathic atrial fibrillation. Dilaveris PE, Gialafos EJ, Sideris SK, et al. Am Heart J. 1998;135:733–738. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resveratrol attenuates chronic pulmonary embolism-related endothelial cell injury by modulating oxidative stress, inflammation, and autophagy. Liu X, Zhou H, Hu Z. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2022;77:100083. doi: 10.1016/j.clinsp.2022.100083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CHEST: Mnemonic approach to manage pulmonary embolism. El Hussein MT, Habib J. Nurse Pract. 2022;47:22–30. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000841924.43458.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.T wave axis deviation and QRS-T angle - controversial indicators of incident coronary heart events. Dilaveris P, Antoniou CK, Gatzoulis K, Tousoulis D. J Electrocardiol. 2017;50:466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reproducibility of global electrical heterogeneity measurements on 12-lead ECG: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Haq KT, Lutz KJ, Peters KK, et al. J Electrocardiol. 2021;69:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2021.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frontal plane QRS-T angle predicts early recurrence of acute atrial fibrillation after successful pharmacological cardioversion with intravenous amiodarone. Eyuboglu M, Celik A. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46:1750–1756. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evaluation of mortality among patients of acute coronary syndrome with frontal QRS-T angle; 100 presenting to tertiary care hospital. Hassan H, Arshad E, Musharraf M, Ahmad Z, Aslam M, Anwer Z. Ann Punjab Med Coll. 2020;14:196–199. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The relationship between in-hospital mortality and frontal QRS-T angle in patients with COVID-19. Tastan E, İnci Ü. Cureus. 2022;14:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assessment of electrocardiographic parameters in patients with electrocution injury. Karataş MB, Onuk T, Güngör B, et al. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Association of frontal QRS-T angle--age risk score on admission electrocardiogram with mortality in patients admitted with an acute coronary syndrome. Lown MT, Munyombwe T, Harrison W, et al. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ST Segment Yükselmesiz Myokard İnfarktüsünde Gensini Skoru ile Elektrokardiyografik Frontal QRS-T Açısı Arasındaki İlişki [The relationship between electrocardiographic frontal QRS-T angle and Gencini score in non-ST segment elevated myocardial infarction] Gül S, Erdoğan G, Yontar OC, Arslan U. Kafkas J Med Sci. 2021;11:268–274. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The role of baseline and post-procedural frontal plane QRS-T angles for cardiac risk assessment in patients with acute STEMI. Colluoglu T, Tanriverdi Z, Unal B, Ozcan EE, Dursun H, Kaya D. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2018;23:0. doi: 10.1111/anec.12558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evaluation of Tpe interval and Tpe/QT ratio in patients with slow coronary flow. Zehir R, Karabay CY, Kalaycı A, Akgün T, Kılıçgedik A, Kırma C. Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:463–467. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Usefulness of electrocardiographic frontal QRS-T angle to predict increased morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Gotsman I, Keren A, Hellman Y, Banker J, Lotan C, Zwas DR. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Is there any relationship between frontal QRS-T angle and subclinical hypothyroidism? Usalp S, Altuntaş E, Bağırtan B, Bayraktar A. Cukurova Med J. 2021;46:1117–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assessment of palpitation complaints in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Günlü S, Aktan A. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:6979–6984. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202210_29880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evaluation of the heart rate variability in cardiogenic vertigo patients. Gunlu S, Aktan A. Int J Cardiovasc Acad. 2022;8:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evaluation of the cardiac conduction system in fibromyalgia patients with complaints of palpitations. Günlü S, Aktan A. Cureus. 2022;14:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardiac arrhythmias, conduction system abnormalities, and autonomic tone in patients with brucellosis. Günlü S, Aktan A. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:9473–9479. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202212_30699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]