Abstract

Objective

The amount of online medical information available is rapidly growing and YouTube is considered as the most popular source of healthcare information nowadays. However, no study has been conducted to comprehensively evaluate YouTube videos related to temporomandibular disorders (TMD). So this study aimed to evaluate the content and quality of YouTube videos as a source of medical information on TMD.

Method

A total of 237 YouTube videos that were systematically searched using five keywords (temporomandibular disorders, tmd, temporomandibular joint, tmj, and jaw joint) were included. Included videos were categorized by purpose and source for analysis. The quality (DISCERN, Health on the Net (HON), Ensuring Quality Information for Patients (EQIP), and Global Quality Scale (GQS)) and scientific accuracy of video contents were evaluated.

Results

Total content, DISCERN, HON, EQIP, and GQS scores were 7.5%, 38.9%, 35.2%, 53.0%, and 48.6% of the maximum possible score, respectively. Only 69 videos (29.1%) were considered as “useful” for patients. News media, physician, and medical source videos showed higher evaluation scores than others. Quality evaluation scores were not significantly correlated or negatively correlated with public preference indices. In the ROC curve analysis, content and DISCERN score showed above excellent discrimination ability for high-quality videos based on GQS (P < 0.001) and total score (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

YouTube videos related to TMD contained low quality and scientifically inaccurate information that could negatively influence patients with TMD.

Keywords: YouTube, videos, temporomandibular disorders, content assessment, global quality scale, DISCERN

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a functional disorder that affects up to 60% of the adult population and is the second most common cause of pain in the orofacial area only behind tooth pain.1,2 Many TMD patients experience symptoms of an acute nature and generally respond well to conventional treatment, however, 10% of TMD proceeds to become chronic even with treatment leading to a significant decrease in quality of life.3 Chronic pain is closely related to psychological conditions that renders the patient dependent and vulnerable to outside information.4 More than half of chronic pain patients rely on the Internet to gain pain-related medical information and over 50% believed the information to be trustworthy. This usage rate is twice as high compared to the general population.5

Worldwide access to the Internet has increased exponentially and 68% of the adult users have been reported to gain health-related information online.6 YouTube is a video-based social media that is gaining popularity due to its open environment that allows interactive communication and is now ranked as the second most commonly accessed website with 30 million users employing it daily.7–9 Along with the increasing number of YouTube videos carrying medical information, concern has risen related to the quality of the videos and the negative health consequences that may be caused by the dissemination of incorrect knowledge10–13 leading to the development of valid evaluation methods.14–16 In spite of the increasing popularity of YouTube as a source of medical information, there has been no attempt to comprehensively analyze the quality of YouTube videos as a source of information on TMD except for one previous attempt based on a single search word without applying validated assessment tools.17 Considering the fact that TMD prevalence peaks in early adults known to be highly digital friendly, the current lack of validated data is even more concerning.1,18 Health Information Seeking Behavior on the Internet is considered to influence patient–doctor relationship hence affecting treatment prognosis, which further underlines the need to provide recommendations on online video selection and future strategies to enhance the quality of videos on TMD.19

Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a comprehensive investigation of the content and quality of YouTube videos as a source of medical information on TMD by applying five different validated scoring instruments to distribute consolidated data for future guideline development.

Materials and methods

Data collection

In this cross-sectional study, YouTube (YouTube, YouTube LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) was searched on 11 August 2020 using frequently used terms by the public decided by Google Ads; “temporomandibular disorders,” “tmd,” “temporomandibular joint,” “tmj,” and “jaw joint.”20 A manual search of the “suggested videos” list from the result pages was also performed to verify additional pertinent videos. Through previous research it is known that search results from over five pages do not relate well to the search term.21,22 Hence, only the first 100 videos of results retrieved against each keyword by default YouTube algorithm (5 pages of 20 videos per page in decreasing order of relevance) were screened and included in this study. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were followed to ensure quality in the data extraction process.23 The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) duplicated videos; (2) non-English videos without English subtitles; (3) video content not related to TMD; (4) videos which were too short (< 30 s) or too long (> 1 h); (5) videos without audio. Basic information including title, uniform resource locator, upload date, duration, uploader identity, license type, origin country, view count (view counts increase each time videos are loaded when a viewer intentionally plays it), number of likes/dislikes, mean daily view count (total view count determined during viewing of the video by the reviewers/date of viewing the video by the reviewers-upload date of the video to YouTube (days)), and number of comments were recorded. All advertisements in the beginning of videos were not considered.

Popularity of the videos were determined by the Video Power Index (VPI, like count/[dislike count + like count] × 100).24 The videos were grouped according to uploader identity as academic (affiliated with a medical journal, or a medical society, or research groups or universities/colleges), physician (independent physicians or physician groups without research or academic institution affiliations), non-physicians (health professionals who are not licensed medical doctors), medical sources (content from health websites), patients, commercial (industry funded, displayed advertisements, or included products for sale), and those that did not meet any of the above groupings.

The videos were divided into four categories by purpose which were differentiated based on the primary themes of the actual content irrespective of the title: education (medical courses or academic videos); entertainment (comedies and talk shows); news & politics (videos from government agencies and news reports); people blogs (videos of personal experiences or opinions).25,26

Each reviewer went through a standardized education session and was given identical instructions on the scoring criteria. The kappa coefficient of agreement was used to determine the degree of agreement between the two reviewers who are both proficient in English, trained in the same training hospital with each having more than 10 years of clinical experience in TMD treatment. Any discrepancies in grouping were resolved by a third reviewer who is proficient in English and has more than 15 years of clinical experience in the field.

Creation of content topics and analysis of scientific accuracy

The main contents and points within themes for TMD were synthesized by a panel of three orofacial pain specialists, all with more than 10 years of clinical experience based on book chapters for dental school students and dentists.27 The scoring system to evaluate the content and its accuracy were established based on previous methods.28–30 The categories and relative values (total score 100) are presented in Table 1. Information not included in the designated topics and therapeutic advertisement were awarded 0 points. The time spent on each category was also recorded in relation to the total video duration.

Table 1.

Evaluation criteria for the content of YouTube videos on temporomandibular disorders.

| Topic | Maximum points | Points per check point | Checkpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomy of temporomandibular joint | 10 | 2 | Temporal bone, mandible, articular disc, translation movement, masticatory muscles |

| Signs and symptoms | 20 | 2.5 | Pain, mouth-opening limitation, biting or chewing difficulty, joint noise, headache, ear pain, malocclusion, muscle weakness |

| Etiology | 10 | 1 | Injury, parafunctional habit, skeletal malformation, bruxism, poor posture, stress, depression, anxiety, malocclusion, overuse of temporomandibular joint |

| Evaluation and diagnosis | 10 | 1 | Joint palpation, muscle palpation, history taking, mouth opening measurement, radiographic examination, joint noise evaluation, intraoral evaluation, magnetic resonance imaging, psychological assessment, diagnostic injection |

| Treatment options | 30 | 4 | Stabilization splint, oral anti-inflammatory medications, physical therapy, home-based exercise |

| 2 | Behavioral modification, joint injection, botulinum toxin injection, joint manipulation, biofeedback, arthrocentesis, temporomandibular joint surgery | ||

| Complications of treatment | 10 | 2 | Tooth pain, malocclusion, acute mouth-opening limitation, skin irritation, pain |

| Prognosis and outcomes | 10 | 5 | Prognosis and treatment outcomes of non-surgical treatment Prognosis and treatment outcomes of surgical treatment |

Quality assessment

DISCERN,14 Health on the Net (HON) criteria15 as a customized tool,28 and Ensuring Quality Information for Patients (EQIP)16,31 were applied. The Global Quality Scale (GQS)32 was applied to evaluate the medical quality of the posted videos based on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all useful, 2 = very limitedly useful, 3 = somewhat useful, 4 = useful, and 5 = very useful) following the classification of Qi et al.33

Videos were finally classified as useful (scientifically accurate information on any aspect of the disease) or misleading (scientifically unproven or inaccurate information according to current scientific literature).34,35 A video was classified as neither nor when it did not fit any group. Misleading videos were further divided into “potentially harmful” and “not harmful.” Based on this classification, a total score (1 = misleading, potentially harmful, 2 = misleading, not harmful, 3 = useful) was assigned to each video.

Statistical analysis

Because data were not normally distributed based on Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, non-parametric tests were applied. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to calculate cut-off values of quality assessment instruments for qualified YouTube videos according to GQS and total score (each score ≥ 3). The role of area under the curve (AUC) as discriminating cut-off value was considered acceptable 0.7–0.8; excellent 0.8–0.9; or outstanding >0.9. Results were considered statistically significant at a level of P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

General characteristics of YouTube videos

A flow diagram of the screening and selection process of TMD-related videos is shown in Figure 1. A total of 237 YouTube videos were reviewed in the study which were uploaded from 17 countries, mostly Anglo-American countries (70.9%).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the screening and selection process of temporomandibular disorders related videos on YouTube.

TMD: temporomandibular disorders; tmj: temporomandibular joint.

Table 2 shows general characteristics of the included videos. The most common source of video was physician (n = 109, 46.0%). The purpose of the majority of videos was education (n = 219, 92.4%). The number of likes of videos was remarkably higher compared to the number of dislikes, resulting in a high VPI value for most videos.

Table 2.

Summary of included YouTube videos on temporomandibular disorders.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 237) |

|---|---|

| Sourcea | |

| Academic | 32 (13.5) |

| Physician | 109 (46.0) |

| Non-physician | 56 (23.6) |

| Medical sources | 21 (8.8) |

| News media | 4 (1.7) |

| Patient | 8 (3.4) |

| Commercial | 4 (1.7) |

| Miscellaneous | 3 (1.3) |

| Purposea | |

| Education | 219 (92.4) |

| Entertainment | 3 (1.3) |

| News & Politics | 3 (1.3) |

| People & Blogs | 12 (5.0) |

| Posted daysb | 1160 (510, 1931) |

| Duration (sec)b | 300 (160, 534) |

| Viewsb | 6157 (1718, 33238) |

| Views/dayb | 5.57 (1.65, 42.10) |

| Likesb | 44 (11, 283) |

| Dislikesb | 2 (0, 10) |

| VPIb | 96.82 (92.86, 100) |

| Commentsb | 6 (1, 34) |

VPI, Video Power Index.

n (%).

Median (quartile range).

Content and quality assessment of videos

Content scoring results are presented in Table 3. The quality and accuracy of the content of the included videos were relatively poor. The total content point was only 7.5% of the maximum possible score. The mean number of topics covered by each YouTube video was only 2.7. “Treatment option” was covered in more than half of the videos, whereas the mean score was only 6.4% of the possible maximum score. “Complication of treatment” was rarely addressed. The mean kappa value of agreement on content scoring results between the two reviewers was 0.825, indicating nearly perfect agreement.

Table 3.

Evaluation scores of included YouTube videos on temporomandibular disorders.

| Scoring method | Score | % (among total videos or of maximum points) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content score | |||

| Anatomy of temporomandibular joint | Topic | 94 | 39.7 |

| Point (0–10) | 2.00 (3.05) | 20.0 | |

| Time | 70.90 (233.10) | ||

| Signs and symptom | Topic | 86 | 36.3 |

| Point (0–20) | 2.31 (3.79) | 11.6 | |

| Time | 18.40 (47.20) | ||

| Etiology | Topic | 51 | 21.5 |

| Point (0–10) | 0.36 (0.90) | 3.6 | |

| Time | 9.20 (32.90) | ||

| Evaluation and diagnosis | Topic | 62 | 26.2 |

| Point (0–10) | 0.44 (1.23) | 4.4 | |

| Time | 51.50 (233.9) | ||

| Treatment options | Topic | 162 | 68.4 |

| Point (0–30) | 1.93 (3.13) | 6.4 | |

| Time | 112.70 (192.10) | ||

| Complications of treatment | Topic | 4 | 1.7 |

| Point (0–10) | 0.03 (0.20) | 0.3 | |

| Time | 0.90 (8.80) | ||

| Prognosis and outcomes | Topic | 38 | 16.0 |

| Point (0–10) | 0.40 (0.92) | 4.0 | |

| Time | 3.60 (15.90) | ||

| Therapeutic advertisement | Topic | 14 | 5.9 |

| Time | 2.20 (15.00) | ||

| Unclear or other topics | Topic | 137 | 57.8 |

| Time | 110.20 (189.70) | ||

| Total points (0–100) | Point | 7.50 (7.80) | 7.5 |

| DISCERN score (16–80) | 31.10 (4.16) | 38.9 | |

| HON score (0–16) | 5.64 (1.00) | 35.2 | |

| EQIP score (0–100) | 53.01 (5.07) | 53.0 | |

| GQS score (1–5)a | 2.43 (0.64) | 48.6 | |

| Total score (1–3)b | 1.97 (0.78) | 65.7 | |

| Useful | 69 | 29.1 | |

| Misleading, not harmful | 93 | 39.2 | |

| Misleading, potentially harmful | 75 | 31.7 |

HON: Health on the Net; EQIP: Ensuring Quality Information for Patients; GQS: Global Quality Scale.

Topic: number of videos handling the topic; Point: mean (SD) of total points (number of checkpoints X allocated points per checkpoint) for each category; Time: mean (SD) of seconds handling the topic; SD: standard deviation.

GQS: 1 point, not at all useful; 2 points, very limitedly useful; 3 points, somewhat useful; 4 points, useful; 5 points, very useful.

Total score: 1 point (misleading, harmful), scientifically unproven or inaccurate, and potentially harmful information according to currently available scientific evidence; 2 points (misleading, not harmful), scientifically unproven or inaccurate, but not harmful information according to currently available scientific evidence; 3 points (useful), scientifically correct and accurate information about any aspect of the disease.

The mean scores of other quality assessment instruments, DISCERN, HON, EQIP, and GQS were around or below 50% of the maximum possible score. Such results mean that the majority of included videos were of poor quality. Additionally, the mean kappa values for agreement of the three quality assessment instruments (DISCERN, HON, and EQIP) were less than 0.3, indicating poor agreement among the two reviewers.

Evaluation scores and characteristics of videos according to uploader source are shown in Table 4. News media videos showed the highest content and DISCERN score. Physician videos showed the highest HON score while EQIP score was highest in miscellaneous videos. Medical source videos showed the lowest HON and EQIP score. The content score was lowest in commercial videos, and the DISCERN score was lowest in the videos uploaded by patients. GQS was highest in news media videos, with the videos uploaded by patients showing the lowest score. The total score was highest in the videos from medical sources, with the miscellaneous videos showing the lowest score. Views/day and number of comments were highest in the miscellaneous videos, while videos uploaded from the news media showed the lowest value.

Table 4.

Evaluation scores and characteristics of videos according to source.

| Academic | Physician | Non-physician | Medical sources | News media | Patient | Commercial | Miscellaneous | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 32) | (n = 109) | (n = 56) | (n = 21) | (n = 4) | (n = 8) | (n = 4) | (n = 3) | ||

| Evaluation scorea | |||||||||

| Content (0–100) | 9.05 (9.06) | 6.92 (7.50) | 5.52 (5.25) | 11.90 (10.19) | 18.44 (13.05) | 6.44 (5.08) | 4.88 (8.47) | 7.33 (9.24) | 0.009 |

| DISCERN (16–80) | 31.91 (4.92) | 31.02 (3.83) | 30.12 (3.92) | 33.00 (4.86) | 34.75 (4.33) | 28.75 (3.05) | 30.50 (3.54) | 32.67 (2.02) | 0.078 |

| HON (0–16) | 5.86 (1.30) | 5.90 (0.83) | 5.28 (0.87) | 4.83 (1.03) | 5.88 (1.55) | 5.62 (0.69) | 5.63 (1.44) | 5.67 (0.29) | <0.001 |

| EQIP (0–100) | 52.75 (4.53) | 53.01 (4.88) | 53.69 (5.62) | 50.21 (3.73) | 55.63 (9.11) | 53.98 (3.75) | 52.66 (5.39) | 56.67 (7.94) | 0.139 |

| GQS (1–5) | 2.59 (0.71) | 2.33 (0.55) | 2.21 (0.46) | 3.24 (0.70) | 3.25 (0.96) | 2.00 (0.53) | 2.50 (0.58) | 2.33 (0.58) | <0.001 |

| Total (1–3) | 2.34 (0.70) | 1.79 (0.75) | 1.82 (0.70) | 2.76 (0.62) | 2.75 (0.50) | 1.88 (0.64) | 1.75 (0.96) | 1.67 (1.15) | <0.001 |

| Characteristicsb | |||||||||

| Views/day | 2.4 (1.2, 11.9) | 2.8 (0.6, 10.9) | 16.7 (4.4, 89.4) | 48.7 (11.4, 96.8) | 2.0 (0.6, 3.2) | 30.5 (11.4, 112.3) | 23.0 (2.9, 47.1) | 498.7 (249.8, 1053.3) | <0.001 |

| Total views (%) | 421015 (2.3) | 6458742 (34.7) | 5353879 (28.7) | 3042169 (16.3) | 10562 (0.1) | 1328249 (7.1) | 228405 (1.2) | 1780362 (9.6) | - |

| VPI | 99.0 (93.6, 100.0) | 96.3 (91.0, 100.0) | 97.3 (94.5, 98.9) | 96.6 (94.1, 98.4) | 86.1 (62.5, 91.7) | 97.3 (94.9, 98.7) | 94.5 (92.1, 96.8) | 98.5 (96.1, 98.6) | 0.604 |

| Comments | 6.0 (0.0, 17.8) | 3.0 (1.0, 16.0) | 18.0 (4.8, 71.5) | 17.0 (3.0, 36.0) | 2.5 (0.0, 5.3) | 69.5 (24.0, 162.3) | 15.5 (0.0, 37.0) | 643.0 (321.5, 1356.0) | <0.001 |

HON: Health on the Net; EQIP: Ensuring Quality Information for Patients; GQS: Global Quality Scale; VPI: Video Power Index; SD: standard deviation.

Results were obtained through Kruskal–Wallis test.

Mean (SD).

Median (quartile range) or n (%).

Evaluation scores and characteristics of videos according to video purpose are shown in Table 5. Scores for all quality assessment instruments were highest in news and politics videos, with people and blog videos showing the lowest score. On the other hand, views/day and number of comments were highest in the people and blogs and lowest in news and politics videos. However, the difference was not statistically significant. VPI value was highest in education and lowest in news and politics videos.

Table 5.

Evaluation scores and characteristics of videos according to purpose.

| Education | Entertainment | News & politics | People & blogs | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 219) | (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 12) | ||

| Evaluation scorea | |||||

| Content (0–100) | 7.28 (7.67) | 18.58 (6.26) | 20.42 (15.23) | 4.92 (4.43) | 0.033 |

| DISCERN (16–80) | 31.17 (4.06) | 34.83 (6.25) | 35.67 (4.80) | 27.71 (3.24) | 0.007 |

| HON (0–16) | 5.63 (0.99) | 6.17 (1.04) | 6.17 (1.76) | 5.38 (1.00) | 0.575 |

| EQIP (0–100) | 53.01 (5.00) | 55.42 (6.17) | 56.67 (10.87) | 51.51 (4.30) | 0.462 |

| GQS (1–5) | 2.42 (0.62) | 3.00 (1.00) | 3.33 (1.15) | 2.08 (0.67) | 0.028 |

| Total (1–3) | 1.97 (0.78) | 2.67 (0.58) | 2.67 (0.58) | 1.67 (0.65) | 0.088 |

| Characteristicsb | |||||

| Views/day | 5.7 (1.6, 42.6) | 3.2 (1.7, 76.9) | 0.7 (0.4, 2.0) | 7.7 (3.7, 19.3) | 0.274 |

| Total views (%) | 17192199 (92.3) | 124605 (0.7) | 8707 (0.0) | 1297890 (7.0) | - |

| VPI | 97.2 (93.6, 100.0) | 83.7 (66.9, 91.9) | 83.3 (41.7, 86.1) | 95.9 (88.5, 98.7) | 0.015 |

| Comments | 7.0 (1.0, 32.5) | 6.0 (6.0, 173.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 2.5) | 11.0 (1.5, 78.3) | 0.293 |

HON: Health on the Net; EQIP: Ensuring Quality Information for Patients; GQS: Global Quality Scale; VPI: Video Power Index; SD: standard deviation.

Results were obtained through Kruskal–Wallis test.

Mean (SD).

Median (quartile range) or n (%).

Correlation between evaluation scores and general characteristics of videos

All quality assessment instruments were significantly correlated with each other. However, content score did not show a significant correlation with HON score. Indices such as views/day, VPI, and number of comments were significantly correlated with each other. However, VPI was negatively correlated with views/day (β = −0.261, P < 0.001) and number of comments (β = −0.155, P < 0.05). In the correlation between quality evaluation scores and general video characteristics DISCERN score was correlated with views/day (β = 0.131, P < 0.05), HON score was negatively correlated with views/day (β = −0.137, P < 0.05), and EQIP score was significantly correlated with views/day (β = 0.256, P < 0.001) and number of comments (β = 0.271, P < 0.001). Content score did not show any significant correlations with any general video characteristic.

Effectiveness of evaluation scores to predict high-quality videos

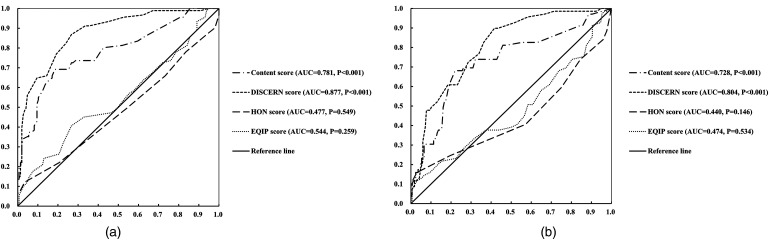

As in Table 6 and Figure 2, ROC curve analyses for determining high-quality videos based on GQS indicated that content (cut-off 5.625, AUC 0.781) and DISCERN (cut-off 31.250, AUC 0.877) scores showed meaningful results. Also for classification based on total score, content (cut-off 6.875, AUC 0.728) and DISCERN (cut-off 31.250, AUC 0.804) score showed significant results. Both showed above excellent discrimination ability for high-quality videos.

Table 6.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analyses for evaluation scores to discriminate qualified YouTube videos.

| AUC (95% CI) | Cut off value | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | LR + | LR- | Error rate (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GQS score ≥ 3 | ||||||||||

| Content | 0.781 (0.718–0.843) | 5.625 | 0.725 | 0.726 | 0.623 | 0.809 | 2.647 | 0.378 | 0.274 | <0.001 |

| DISCERN | 0.877 (0.832–0.922) | 31.250 | 0.824 | 0.760 | 0.682 | 0.874 | 3.438 | 0.231 | 0.215 | <0.001 |

| HON | 0.477 (0.398–0.555) | 5.750 | 0.495 | 0.459 | 0.363 | 0.593 | 0.914 | 1.102 | 0.527 | 0.549 |

| EQIP | 0.544 (0.466–0.621) | 53.438 | 0.495 | 0.507 | 0.385 | 0.617 | 1.003 | 0.997 | 0.498 | 0.259 |

| Total score ≥ 3 | ||||||||||

| Content | 0.728 (0.653–0.803) | 6.875 | 0.696 | 0.738 | 0.522 | 0.855 | 2.656 | 0.412 | 0.274 | <0.001 |

| DISCERN | 0.804 (0.746–0.862) | 31.250 | 0.768 | 0.661 | 0.482 | 0.874 | 2.264 | 0.351 | 0.308 | <0.001 |

| HON | 0.440 (0.350–0.530) | 5.750 | 0.406 | 0.429 | 0.226 | 0.637 | 0.710 | 1.386 | 0.578 | 0.146 |

| EQIP | 0.474 (0.388–0.560) | 52.813 | 0.449 | 0.435 | 0.246 | 0.658 | 0.795 | 1.267 | 0.561 | 0.534 |

AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; LR + : positive likelihood ratio; LR−: negative likelihood ratio; GQS: global quality scale; HON: Health on the Net; EQIP: Ensuring Quality Information for Patients.

Sensitivity was obtained from TP/(TP + FN) × 100, Specificity was obtained from TN/(TN + FP) × 100, PPV was obtained from TP/(TP + FP) × 100, NPV was obtained from TN/(TN + FN) × 100, Error rate was obtained from (FN + FP)/(TN + TP + FN + FP).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for evaluation scores to discriminate good quality YouTube videos based on GQS (a) and total score (b). Content and DISCERN score show good discrimination ability for high-quality YouTube videos.

Discussion

This first investigation to comprehensively report on the content and quality of YouTube videos for TMD based on multiple validated evaluation tools showed that most of the analyzed videos were of low credibility and information quality. Two-third of all YouTube videos contained scientifically unproven or inaccurate information, of which half were potentially harmful to viewers. This is in line with a previous study that analyzed the content and quality of websites for TMD based on identical evaluation tools showing that most sites were poorly organized and maintained.36 The quality of the evaluated videos was even inferior compared to the websites related to TMD. The DISCERN and HON score of TMD related websites were approximately 1.32 and 1.29 times higher compared to TMD related YouTube videos. One point to take into account when interpreting the results is that the agreement between the two reviewers was poor for videos compared to that for websites. Considering the fact that both reviewers had abundant experience with the tools, such a discrepancy may indicate the incompatibility of the tools in evaluating video contents. The DISCERN, HON, and EQIP tool were initially developed for written online healthcare information and later used as assessment instruments in studies analyzing YouTube videos.31,37,38 Although many YouTube videos come with subtitles, written and video instructions are known to result in different levels of understanding of the receiver and this may result from inherent differences in the form of information.39 Since the name of the video uploader and the date of update are always indicated due to the policy of the YouTube system this may have caused an overall inflation of evaluation scores.

The content score of the evaluated videos was low because the mean number of topics covered per video was only 2.7 among the seven topics assessed and this may have been caused by the short duration of the videos (median video length, 300 s). Several videos with high content scores were too long or aimed for professionals or dental students, so the content was difficult for the general population to understand and take interest in. This may further aggravate the problem of bias in the information the viewers actually encounter. Therefore, further studies are needed to develop and verify a novel assessment tool that is optimized for the evaluation of video contents and can comprehensively evaluate the credibility, scientific accuracy, and understandability of YouTube videos.

The most common video source was physicians, however the evaluation scores for such videos were lower compared to most other sources. This could have a significant negative impact since the viewer will naturally consider the information offered by physicians more reliable.40 Patient videos were generally of a low evaluation score, however views per day and number of comments was the highest among all videos. This could result in a rapid spread of low-quality information which would eventually cause unnecessary barriers in patient–doctor communication.41 The mismatch between video quality and public preference was also evident in the correlation analysis results of this study. Interestingly, evaluation scores were not significantly correlated or negatively correlated with public preference indices. Especially, VPI did not show a significant correlation with any of the evaluation scores. Future content developers should try to understand the characteristics of popular videos on YouTube and combine them with accurate information on TMD that will be easily understood and accepted by the general population. On the other hand, the clinician should be able to inform the inquiring patient on the low quality of the information related to TMD that can be currently found on YouTube. A similar trend could be found when the YouTube videos were grouped according to production purpose. News and politics videos had the highest evaluation scores but the number of views per day, VPI, and number of comments were the lowest showing that high quality is not connected to efficient knowledge distribution.

The scientific content of videos was rarely assessed in previous studies. The most frequently mentioned topic in the TMD related YouTube videos was introduction of treatment options. However, many videos suggested treatments that were not well-proven or lacked evidence to support their use.1,42 Furthermore, the topic of complications of treatment was the least handled with the lowest content score among all topics. Deciding on a specific treatment option unaware of its possible complications is known to affect the actual consent rate of a patient.43 The patient should be fully aware of all possible prognosis before decision making and such a biased picture offered by the current YouTube videos could lead to unneeded medicals costs that are generated on the request of the patient.44 Another topic that is rarely included (3.6% of maximum points) in TMD YouTube videos is etiology-related contents. Patient education is a central component of the management of patients with chronic pain including TMD. Through this process, patients with TMD are able to better understand their condition and control persistent contributing factors that could aggravate TMD symptoms.45 Several previous studies have reported the impact of patient education on TMD symptoms.46,47 Online health information could be an important tool for patient education, and may positively affect patients with chronic illnesses.48,49 However, 70.9% of all evaluated videos included misleading information on TMD and 32% had potentially harmful contents. Patient exposure to misleading information may have a secondary negative impact on the clinician in providing appropriate treatment for patients with TMD. Also, as medical health providers themselves heavily rely on online search engines, online medical information may have a dual impact on the decision making of the clinician.50

ROC curve analyses showed that content and DISCERN score are both effective in indicating high-quality YouTube videos on TMD and the cut-off value is suggested here for the first time in literature. Such values could be directly applied in selecting appropriate videos for patient education and guidance until a better standardized evaluation tool specific for online video content is developed. Based on the above findings, the source of videos will help select a useful and trustworthy video. In general, videos produced by dental/medical personnel affiliated to organizations operated by public trusts such as news and academic organizations without the purpose of advertisement could be recommended to patients.

The strong points of this study are a large sample size and application of various validated evaluation tools for online content. Also, the content evaluation system developed for this study allowed comprehensive assessments of the included videos along with comparison among scores. In spite of such strengths, this study has some limitations. The viewer comments, which may contain detailed opinions were not analyzed. Also, the visual and instructional design of the videos were not evaluated and its impact on the viewers may not have been understood. Our study is specific for a time point. The online environment and viewer responses may change due to circumstances including the worldwide pandemic and future research is planned to compare characteristics of related videos according to time period. Lastly, the scoring system for scientific accuracy may result in videos on a narrower subject within TMD having low scores in spite of the accuracy of its content. The system was however appropriate in analyzing the trend of what topics are mainly dealt with in YouTube videos. And it was also possible to check whether the related contents within the topic were sufficiently and accurately covered. The current score is appropriate in differentiating videos that offer a high-quality overview on the subject of TMD for those that do not possess in-depth knowledge on the subject. Future studies should consider analyzing the score achievement of each subcategory to overcome such limitations.

Conclusions

The quality of TMD-related YouTube videos are low and the majority of videos contained scientifically inaccurate information that could negatively influence TMD management when viewed by a patient. Organizational efforts of TMD specialists are needed to provide scientifically accurate information within YouTube and develop assessment instruments appropriate for online video content which can be easily recognized in order to allow the general population to access accurate information on TMD without difficulty.

Footnotes

Contributorship: MJK: acquisition and analysis of data, drafting the article, final approval of the version to be published, agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work if questions arise related to its accuracy or integrity. JRK: conception and design, acquisition and analysis of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work if questions arise related to its accuracy or integrity. JHJ: analysis and interpretation of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work if questions arise related to its accuracy or integrity. JSK: analysis and interpretation of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work if questions arise related to its accuracy or integrity. JWP: analysis and interpretation of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work if questions arise related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Ji Woon Park https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0625-7021

Data availability statement: Raw data were generated at Seoul National University Dental Hospital. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (JWP) on request.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study is based on the analysis of data extracted from the Internet hence, ethical approval is not required.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor: JWP

References

- 1.Gauer RL, Semidey MJ. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Am Fam Physician 2015; 91: 378–386.. [Medline: 25822556]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SB, Maixner DW, Greenspan JD, et al. Potential genetic risk factors for chronic TMD: genetic associations from the OPPERA case control study. J Pain 2011; 12: T92–T101.. [Medline: 22074755]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resende CM, Alves AC, Coelho LTet al. et al. Quality of life and general health in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Braz Oral Res 2013; 27: 116–121.. [Medline: 23459771]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiter S, Emodi-Perlman A, Goldsmith Cet al. et al. Comorbidity between depression and anxiety in patients with temporomandibular disorders according to the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2015; 29: 135–143.. [Medline: 25905531]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinchuk LM, Chiou P, Czarnowski Vet al. et al. Demographics and attitudes of chronic-pain patients who seek online pain-related medical information: implications for healthcare providers. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 89: 141–146.. [Medline: 19966558]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nölke L, Mensing M, Krämer Aet al. et al. Sociodemographic and health-(care-) related characteristics of online health information seekers: a cross-sectional German study. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 31.. [Medline: 25631456]. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1423-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuel N, Alotaibi NM, Lozano AM. YouTube as a source of information on neurosurgery. World Neurosurg 2017; 105: 394–398.. [Medline: 28599904]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexa. Website traffic analysis. 2020. URL: https://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/youtube.com [accessed 2020-08-11]

- 9.Omnicore. YouTube by the Numbers: Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts. 2020. URL: https://www.omnicoreagency.com/youtube-statistics/ [accessed 2020-08-11].

- 10.Mueller SM, Jungo P, Cajacob Let al. et al. The absence of evidence is evidence of non-sense: cross-sectional study on the quality of psoriasis-related videos on YouTube and their reception by health seekers. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e11935.. [Medline: 30664460]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JSet al. et al. Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Informatics J 2015; 21: 173–194.. [Medline: 24670899]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlsen R, Borrás Morell JE, Fernández Luque Let al. et al. A domain-based approach for retrieving trustworthy health videos from YouTube. Stud Health Technol Inform 2013; 192: 1008.. [Medline: 23920782]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bora K, Das D, Barman Bet al. et al. Are internet videos useful sources of information during global public health emergencies? A case study of YouTube videos during the 2015-16 Zika virus pandemic. Pathog Glob Health 2018; 112: 320–328.. [Medline: 30156974]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham Get al. et al. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999; 53: 105–111.. [Medline: 10396471]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer C, Selby M, Scherrer JRet al. et al. The health on the net code of conduct for medical and health websites. Comput Biol Med 1998; 28: 603–610.. [Medline: 9861515]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moult B, Franck LS, Brady H. Ensuring quality information for patients: development and preliminary validation of a new instrument to improve the quality of written health care information. Health Expect 2004; 7: 165–175.. [Medline: 15117391]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basch CH, Yin J, Walker NDet al. et al. TMJ Online: investigating temporomandibular disorders as “TMJ” on YouTube. J Oral Rehabil 2018; 45: 34–40.. [Medline: 28965355]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbosa Neves B, Fonseca JRS, Amaro Fet al. et al. Social capital and internet use in an age-comparative perspective with a focus on later life. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0192119.. [Medline: 29481556]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan SS, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e9.. [Medline: 28104579]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Google Adwords Keyword Planner. URL: https://adwords.google.com/KeywordPlanner [accessed 2020-07-31]. 2020.

- 21.Murugiah K, Vallakati A, Rajput Ket al. et al. YouTube as a source of information on cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2011; 82: 332–334.. [Medline: 21185643]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azer SA, Algrain HA, AlKhelaif RAet al. et al. Evaluation of the educational value of YouTube videos about physical examination of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e241.. [Medline: 24225171]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff Jet al. et al. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses; the PRISMA statement. Br Med J 2009; 339: b2535.. [Medline: 19622551]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erdem MN, Karaca S. Evaluating the accuracy and quality of the information in kyphosis videos shared on YouTube. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018; 43: E1334–E1339.. [Medline: 29664816]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abedin T, Ahmed S, Al Mamun M, , et al. YouTube as a source of useful information on diabetes foot care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015; 110: e1–e4.. [Medline: 26303266]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delli K, Livas C, Vissink Aet al. et al. Is YouTube useful as a source of information for Sjogren’s syndrome? Oral Dis 2016; 22: 196–201.. [Medline: 26602325]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okeson J. Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion. 8th ed. St Louis: Elsevier: Mosby, 2019, ISBN:9780323676748. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starman JS, Gettys FK, Capo JAet al. et al. Quality and content of internet-based information for ten common orthopaedic sports medicine diagnoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 1612–1618.. [Medline: 20595567]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soot LC, Moneta GL, Edwards JM. Vascular surgery and the internet: a poor source of patient-oriented information. J Vasc Surg 1999; 30: 84–91.. [Medline: 10394157]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, Steinberg DRet al. et al. Evaluating the source and content of orthopaedic information on the internet. The case of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82: 1540–1543.. [Medline: 11097441]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray MC, Gemmiti A, Ata A, , et al. Can you trust what you watch? An assessment of the quality of information in aesthetic surgery videos on YouTube. Plast Reconstr Surg 2020; 145: 329e–336e.. [Medline: 31985630]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes Set al. et al. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the world wide web. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2070–2077.. [Medline: 17511753]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi J, Trang T, Doong Jet al. et al. Misinformation is prevalent in psoriasis-related YouTube videos. Dermatol Online J 2016; 22: 13030. qt7qc9z2m5. [PubMed: 28329562]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh AG, Singh S, Singh PP. YouTube for information on rheumatoid arthritis–a wakeup call? J Rheumatol 2012; 39: 899–903.. [PubMed: 22467934]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong K, Doong J, Trang Tet al. et al. YouTube videos on botulinum toxin A for wrinkles: a useful resource for patient education. Dermatol Surg 2017; 43: 1466–1473.. [PubMed: 28877151]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park MW, Jo JH, Park JW. Quality and content of internet-based information on temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 2012; 26: 296–306. PubMed: 23110269]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bopp T, Vadeboncoeur JD, Stellefson Met al. et al. Moving beyond the gym: a content analysis of YouTube as an information resource for physical literacy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 3335.. [PubMed; 31510001]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuru T, Erken HY. Evaluation of the quality and reliability of YouTube videos on rotator cuff tears. Cureus 2020; 12: e6852.. [Pubmed: 32181087]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoek AE, Bouwhuis MG, Haagsma JA, , et al. Effect of written and video discharge instructions on parental recall of information about analgesics in children: a pre/post-implementation study. Eur J Emerg Med 2021 Jan 1; 28: 43–49.. [PMID: 32842041]. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayden JA, Wilson MN, Riley RDet al. et al. Individual recovery expectations and prognosis of outcomes in non-specific low back pain: prognostic factor review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 2019: CD011284.. [PMID: 31765487; PMCID: PMC6877336]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishikawa H, Yano E, Fujimori S, et al. Patient health literacy and patient-physician information exchange during a visit. Fam Pract 2009; 26: 517–523.. [PMID: 19812242]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaffer SM, Brismée JM, Sizer PSet al. et al. Temporomandibular disorders. Part 2; conservative management. J Man Manip Ther 2014; 22: 13–23.. [Pubmed: 24976744]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergus GR, Levin IP, Elstein AS. Presenting risks and benefits to patients. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17: 612–617.. [PMID: 12213142; PMCID: PMC1495093]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyu H, Xu T, Brotman D, , et al. Overtreatment in the United States. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0181970.. [PMID: 28877170; PMCID: PMC5587107]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winocur E, Littner D, Adams Iet al. et al. Oral habits and their association with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in adolescents: a gender comparison. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 102: 482–487.. [Pubmed; 16997115]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dworkin SF. Behavioral and educational modalities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997; 83: 128–133.. [PubMed 9007936]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cleland J, Palmer J. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy, therapeutic exercise, and patient education on bilateral disc displacement without reduction of the temporomandibular joint: a single-case design. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2004; 34: 535–548.. [PubMed: 15493521]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nolan T, Dack C, Pal K, , et al. Patient reactions to a web-based cardiovascular risk calculator in type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2015; 65: e152–e160.. [PubMed: 25733436]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riva S, Camerini AL, Allam Aet al. et al. Interactive sections of an internet-based intervention increase empowerment of chronic back pain patients: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16: e180.. [Pubmed: 25119374]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hermes-DeSantis ER, Hunter RT, Welch Jet al. et al. Preferences for accessing medical information in the digital age: health care professional survey. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e25868.. [Pubmed: 36260374]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]