Abstract

Violence victimization has been associated with low-grade inflammation. Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) individuals are at greater risk for victimization in childhood and young adulthood compared to heterosexuals. Moreover, the intersection of LGB identity with gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment may be differentially associated with victimization rates. However, no previous study has examined the role of cumulative life-course victimization during childhood and young adulthood in the association between 1) LGB identity and low-grade inflammation during the transition to midlife, and 2) intersection of LGB identity with gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment and low-grade inflammation during the transition to midlife. We utilized multi-wave data from a national sample of adults entering midlife in the United States– the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health; n = 4573) - and tested four bootstrapped mediation models. Results indicate LGB identity, LGB and White, and LGB and Black identities were indirectly associated with low-grade inflammation during the transition to midlife via higher levels of cumulative life-course victimization. Moreover, among LGB adults, the association between 1) less than college education and 2) some college education, and low-grade inflammation was mediated by cumulative life-course victimization. For LGB females, there was a direct association between identity and low-grade inflammation and this association was mediated by cumulative life-course victimization. Reducing accumulation of victimization could be critical for preventing biological dysregulation and disease onset among LGB individuals, particularly for those with multiple marginalized identities.

Keywords: Sexual minority, Intersectionality, Violence victimization, Inflammation

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth experience higher rates of victimization in childhood than their heterosexual peers (Inwards-Breland et al., 2022; Sterzing et al., 2017; Sterzing et al., 2019; Schwab-Reese et al., 2021). To illustrate, in a population study of LGB and gender diverse youth, 40% of the sample experienced multiple victimization in the past year and experienced high levels of physical and sexual victimization as well as child maltreatment (Sterzing et al., 2017; Sterzing et al., 2019). Substantial research has demonstrated that violence victimization in childhood (e.g., community violence, physical and sexual abuse by a caregiver) is associated with inflammation (Heard-Garris et al., 2020; Finegood et al., 2020; Ehrlich et al., 2021; Baldwin et al., 2018). Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein or CRP, play a key role in the body’s immune response against infections and disease (Sproston and Ashworth, 2018; Du Clos and Mold, 2004; Dinarello, 2000; Healy and Freedman, 2006; Freire and Van Dyke, 2013). However, the presence of low-grade inflammation in the absence of infection has been linked to accelerated biological aging leading to increased risk for the onset of premature chronic illnesses (e.g., cardiovascular disease, obesity, cancer) (Chung et al., 2019; Singh and Newman, 2011; Franceschi and Campisi, 2014; Esser et al., 2014; Ben-Neriah and Karin, 2011).

Moreover, the increased risk for victimization in childhood among LGB individuals cascades into early adulthood such that LGB adults with childhood victimization also experience disproportionately higher rates of victimization in early adulthood (Inwards-Breland et al., 2022; Sterzing et al., 2017; Sterzing et al., 2019; Schwab-Reese et al., 2021; Flores et al., 2020). For instance, in a national sample, childhood physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, criminal assault, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault were more commonly reported by LGB young adults compared to heterosexual young adults (Schwab-Reese et al., 2021). Although understudied, evidence also suggests that exposure to violence in early adulthood is linked to low-grade inflammation (Heath et al., 2013; Newton et al., 2011). However, few studies have examined the link between LGB identity, cumulative life-course victimization (i.e., accumulation of victimization in childhood and early adulthood), and inflammation, even though based on the aforementioned evidence, individuals who identify as LGB are at greater risk of victimization both in childhood and early adulthood (Inwards-Breland et al., 2022; Sterzing et al., 2017; Sterzing et al., 2019; Schwab-Reese et al., 2021; Flores et al., 2020).

The hypothesized links between cumulative life-course victimization and inflammation are positioned within the cumulative adversity model wherein accumulation of victimization among LGB individuals may be consequential for “biological embedding” leading to dysregulation of key biological systems (e.g., immune system and inflammation) linked with health and well-being (Kuh et al., 2003; Danese et al., 2009; Hertzman and Boyce, 2010; Turner, 2009). Moreover, the hypothesized role of victimization in the association between sexual orientation and low-grade inflammation is also positioned within the minority stress theory and the biopsychosocial minority stress framework for understanding LGB health disparities (Meyer, 2003; Christian et al., 2021). Specifically, health disparities among marginalized groups can be attributed to experiences of discrimination, exclusion, stigma, and prejudice (Meyer, 2003; Christian et al., 2021). However, not all experiences of victimization can be attributable to minority stress (Diamond and Alley, 2022; Diamond et al., 2021). Recently, researchers have suggested that “chronic social threat” and the lack of “social safety” among LGB adults can lead to poorer health outcomes via the dysregulation of stress-linked biological systems such as the immune system (Diamond and Alley, 2022; Diamond et al., 2021). To elaborate, chronic accumulation of life-course victimization that threaten feelings of safety can lead to biological dysregulation of key systems such as the immune system over time in response to such chronic threat exposures (e.g., presence of low-grade inflammation in the absence of disease or infection) (Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022). And this biological dysregulation in response to social threat can in turn be the critical explanatory link for health disparities in LGB populations (Diamond and Alley, 2022;Diamond et al., 2021).

Moreover, among LGB individuals, intersectional identities based on sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, and socio-economic position may be differentially related to cumulative early life-course victimization compared to heterosexuals. For example, in one study, LGB adults who had less than college education, regardless of gender, had higher victimization rates than heterosexuals (Flores et al., 2020). In comparison, being Hispanic or having a college education were protective against heightened risk for victimization among LGB reposndents (Flores et al., 2020). In another study, African American LGB individuals were more likely to experience higher rates of life-time violence victimization compared to Caucasian youth (Sterzing et al., 2017). Such differences among LGB individuals in rates of victimization based on intersectional identities can be understood within intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1991; Alexander-Floyd, 2012; Guan et al., 2021; Bauer et al., 2021; Crenshaw, 2018). With its origins in the black feminist movement to address the inequities faced by black women as a combined function of racism and sexism (Crenshaw, 1991; Crenshaw, 2018), in recent years, intersectionality theory has been used to understand the divergent lived experiences of individuals by simultaneously examining multiple facets of identity that are framed by sociocultural, political, and historical contexts that lead to inequities, disparities, and minority status (Crenshaw, 1991; Crenshaw, 2018; Guan et al., 2021 Alexander-Floyd, 2012; Bauer et al., 2021). Moreover, research also suggests that these intersectional identities may differentially describe distinct social experiences, health, and well-being (Bauer et al., 2021; Gattamorta et al., 2019; Kapilashrami and Hankivsky, 2018; Guan et al., 2021). However, few studies try to unpack how intersecting multiple identities are linked to cumulative stressors across the life-course. Based on intersectionality theory and the social safety perspectives for sexual and gender minority health, individuals may be at an increased risk for trauma and “social threat” based on their intersectional identities. (Hertzman and Boyce, 2010; Christian et al., 2021; Meyer, 2003; Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022; Crenshaw, 2018; Bauer et al., 2021; Gattamorta et al., 2019; Katz-Wise and Hyde, 2012; Langenderfer-Magruder et al., 2016; Bluthenthal, 2021; Agadullina et al., 2021; Chapleau et al., 2008; Allen et al., 2009; Blondeel et al., 2018; Guan et al., 2021; Turner, 2009) For instance, the combination of homophobia and racism against individuals who identify both as LGB and racial/ethnic minorities or homophobia and sexism towards LGB females could be linked to increased risk for life-course violence victimization (Hertzman and Boyce, 2010; Christian et al., 2021; Meyer, 2003; Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022; Crenshaw, 2018; Bauer et al., 2021; Gattamorta et al., 2019; Katz-Wise and Hyde, 2012; Langenderfer-Magruder et al., 2016; Bluthenthal, 2021; Agadullina et al., 2021; Chapleau et al., 2008; Allen et al., 2009; Blondeel et al., 2018; Guan et al., 2021; Turner, 2009). Therefore, such intersectional identities can increase the frequency of threats experienced (i.e., cumulative life-course victimization) and may exacerbate health disparities (Diamond and Alley, 2022; Diamond et al., 2021).

Utilizing multiple theoretical frameworks, the present study examines the association between cumulative life-course victimization over childhood and young adulthood – life-stages during which victimization rates are highest (Morgan and Oudekerk, 2019) - and 1) low-grade inflammation for those with LGB identity during the transition to midlife (Aim 1) and 2) low-grade inflammation at the intersection of LGB identity with identities previously linked to higher rates of victimization (gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment) during the transition to midlife (Aim 2) in a national sample of LGB and heterosexual adults.

1. Methods

Data come from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health; n = 20,745). Add Health is a national panel study in the U.S. of individuals who were followed from adolescence (grades 7–12 at Wave I: 1994–95) to early midlife (ages 33–43 at Wave V: 2016–2018) (Harris et al., 2019). Add Health includes an oversample of ethnic minorities and used a multi-stage stratified design with individuals clustered within schools (Harris et al., 2019).

At Wave V, a subsample from Add Health (n = 5377) agreed to participate in the biomarker study, and venous blood samples were collected from this subsample to assay for various biomarkers, including for low-grade inflammation. The present research includes a sample of individuals (n = 4573) from the biomarker study who had a valid hsCRP/low-grade inflammation measure and who also reported on their sexual orientation. The study uses secondary data from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) that was reviewed and deemed as exempt Category 4 by Human Subjects Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill.

1.1. Measures

1.1.1. Cumulative life-course victimization (Waves I-V). Cumulative life-course victimization (Waves I-V)

Cumulative life-course cumulative victimization was a count variable that was created by pooling across victimization types – a) criminal assault (ages: 11–43), c) partner violence (ages 18–43), d) Sexual assault (ages 0–40), and e) childhood sexual and physical abuse by a caregiver (before age 18). Due to sample size considerations, 10 or more lifetime exposures were coded as 10 (see supplement for details).

1.1.2. LGB identity (Wave V)

LGB identity was coded as 1 if individuals self-reported sexual identity that was different from 100% heterosexual (i.e., homosexual, mostly homosexual but somewhat attracted to members of the opposite sex, bisexual, mostly heterosexual but somewhat attracted to members of the same sex). LGB identity was coded as 0 (reference group) for individuals whose self-reported sexual identity was 100% heterosexual.

1.1.3. Intersectional identities (Wave V)

Intersectional identities were created for the intersection of 1) LGB identity and gender (male or female) and included four categories - 1) LGB male, 2) LGB female, 3) heterosexual female, and 4) heterosexual male (reference). Sex assigned at birth in Add Health corresponded with self-identified gender of all participants, except a very small number of respondents who reported a gender identity discordant from reported sex assigned at birth. These values are suppressed in the released data set to prevent deductive disclosure. Similarly, race/ethnicity at Wave V was used to create intersectional LGB and race/ethnicity identities and comprised of the following categories – 1) LGB and White, 2) LGB and Black, 3) LGB and Hispanic, 4) heterosexual and Black, 5) heterosexual and Hispanic, and 4) heterosexual and White (reference). Asian, Native American, and Mixed-Race groups were excluded due to small sample sizes for these groups. Finally, intersectional LGB and educational attainment (Wave V) identities were created based on self-reported education level completed and LGB identity and included – 1) LGB with less than college education, 2) LGB with some college education, 3) LGB with college education or higher, 4) heterosexual with less than college education, 5) heterosexual with some college education and 6) heterosexual with college education or higher (reference).

1.1.4. Inflammation (Wave V)

High sensitivity CRP or hsCRP was assayed at Wave V from venous blood samples (see reference for details) (Whitsel et al., 2020). hsCRP has been established as a stable indicator of low-grade inflammation (Sproston and Ashworth, 2018). hsCRP was capped at 3 SD from mean for high values and log-transformed (natural log units) to account for non-normality (skewness) (McDonald, 2014).

1.1.5. Covariates

Several covariates were included in mediation models and included gender (1 = male, 0 = female), years of parent education, years of respondent’s education, respondent’s age. Race/ethnicity was also accounted in models as three dummy variables – Black, Hispanic, and Other with White as reference. Covariates related to race/ethnicity, gender, and years of education/schooling completed by the respondent were not accounted for in models estimating intersectional identities based on LGB and race/ethnicity identities, LGB identity and gender, and LGB and educational attainment identities respectively. Objectively measured body mass index at Wave V and recent infections (1 = yes, 0 = no) were also included as covariates for hsCRP (Freire and Van Dyke, 2013; Forsythe et al., 2008).

1.2. Analytic strategy

Survey means and regression procedures were used to obtain population descriptive statistics and test bivariate association between 1) the identity groups and hsCRP and 2) identity groups and life-course violence victimization using SAS version 9.4 (Institute SAS, 2015). Following this, four mediation models were tested to evaluate direct and indirect effects of 1) LGB identity (model 1) and the intersectional identity groups based on 2) gender (model 2), 3) race/ethnicity (model 3), and 4) educational attainment (model 4) on hsCRP via cumulative life-course victimization. Mplus version 8.7 (Muthén and Muthén, 2020) was used to test mediation models using 1000 bootstraps. All models were corrected for complex sampling features - unequal selection probability and clustering of individuals within schools (Binder, 1983; Chen and Harris, 2020). Additionally, full information maximum likelihood was used to account for missing data after sub-setting for non-missing on sexual orientation and hsCRP, since FIML improves the precision of estimate (Acock, 2012; Arbuckle, 2013). The use of FIML retained the same analytic sample across models.

2. Results

Population descriptive statistics by sexual orientation are presented in Table 1. Approximately 16.52% individuals identified as LGB (n = 787). Moreover, 5.18% were LGB males (n = 186), 11.35% were LGB females (n = 601), and 44.79% were heterosexual females (n = 1649), and 38.69% were heterosexual males (n = 2137).

Table 1.

Population descriptive statistics (Weighted; n = 4573).

| LGB (n = 787) | Heterosexual (n = 3786) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||

| Proportions | % | SE | % | SE |

|

| ||||

| Biological sex: Male | 31.33% | 0.03 | 53.65% | 0.01 |

| Biological sex: Female | 68.67% | 0.03 | 46.35% | 0.01 |

| Race: Black | 10.59% | 0.02 | 16.49% | 0.02 |

| Race: White | 71.88% | 0.03 | 65.59% | 0.03 |

| Race: Hispanic | 10.59% | 0.02 | 10.98% | 0.02 |

| Race: Other | 6.94% | 0.01 | 6.93% | 0.01 |

| Recent infection: Yes | 35.33% | 0.03 | 31.46% | 0.01 |

| Continuous | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Age | 37.04 | 0.16 | 37.29 | 0.12 |

| Parent education in years | 13.55 | 0.16 | 13.34 | 0.11 |

| Responden’s education in years | 14.98 | 0.16 | 14.61 | 0.11 |

| Body mass index (wave 5) | 30.53 | 0.41 | 31.04 | 0.23 |

| Cumulative life-course victimization | 2.88 | 0.13 | 2.31 | 0.07 |

| hsCRP | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.60 | 0.03 |

Note: LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual; hsCRP - high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein;

Similarly, 12.79% were LGB and White (n = 497), 1.88% were LGB and Black (n = 107) 1.88% were LGB and Hispanic (n = 107), 58.81% were heterosexual and White (n =2292), 14.79% were heterosexual and Black (n = 694) and 9.85% were heterosexual and Hispanic (n = 467).

For intersectional identities based on educational attainment and LGB identity, 2.15% were LGB with less than college education (n = 98), 6.89% were LGB with some college education (n = 322), 7.49% LGB with college education or higher (n = 366), 16.03% heterosexual with less than college education (n = 606), 34.19% heterosexual with some college education (n = 1458), 33.25% heterosexual with college education or higher (n = 1716).1

Table 2 includes population means and bivariate survey regression results by identity groups. Heterosexual females and LGB females had higher hsCRP compared to heterosexual males. Similarly, heterosexual Blacks compared to heterosexual Whites had higher hsCRP. Less than college education and some college education for both LGB and heterosexual individuals was associated with higher hsCRP. Moreover, all identity groups except heterosexual females and LGB males had higher victimization rates compared to their respective reference groups. LGB males did not differ significantly from heterosexual males in cumulative life-course victimization and heterosexual females had lower rates of victimization compared to heterosexual males.

Table 2.

Population means (weighted) and survey regression results for bivariate associations by identity groups.

| LGB | |||||||||||||||

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| N | Mean | SE | UL | LL | b | t | p | Mean | SE | UL | LL | b | t | p | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| LGB | 787 | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.56 | 0.85 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.212 | 2.88 | 0.13 | 2.62 | 3.15 | 0.57 | 0.13 | <0.0001 |

| Heterosexual | 3786 | 0.60 | 0.03 | 0.53 | 0.67 | Reference | 2.31 | 0.07 | 2.17 | 2.45 | Reference | ||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| LGB and biological sex groups | |||||||||||||||

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| N | Mean | SE | UL | LL | b | t | p | Mean | SE | UL | LL | b | t | p | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| LGB male | 186 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.995 | 2.75 | 0.25 | 2.25 | 3.26 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.359 |

| LGB female | 601 | 0.83 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.10 | <0.0001 | 2.94 | 0.13 | 2.68 | 3.20 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.006 |

| Heterosexual female | 2137 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.42 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | 2.06 | 0.08 | 1.91 | 2.21 | −0.46 | 0.12 | 0.000 |

| Heterosexual male | 1649 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.49 | Reference | 2.52 | 0.11 | 2.31 | 2.73 | Reference | ||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| LGB and race/ethnicity groups | |||||||||||||||

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| N | Mean | SE | 95% CI | b | t | p | Mean | SE | 95%CI | b | t | p | |||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| LGB and white | 497 | 0.66 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.84 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.228 | 2.65 | 0.14 | 2.36 | 2.93 | 0.58 | 0.16 | 0.001 |

| LGB and black | 107 | 0.79 | 0.14 | 0.50 | 1.08 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.092 | 3.82 | 0.33 | 3.16 | 4.49 | 1.75 | 0.33 | <0.0001 |

| LGB and Hispanic | 107 | 0.85 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 1.19 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.076 | 3.15 | 0.38 | 2.38 | 3.91 | 1.08 | 0.38 | 0.005 |

| Heterosexual and black | 694 | 0.87 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.000 | 2.81 | 0.16 | 2.49 | 3.13 | 0.74 | 0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Heterosexual and Hispanic | 467 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.71 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.683 | 2.61 | 0.18 | 2.25 | 2.96 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.004 |

| Heterosexual and white | 2292 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.62 | Reference | 2.07 | 0.07 | 1.92 | 2.22 | Reference | ||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| LGB and educational attainment groups | |||||||||||||||

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| N | Mean | SE | 95%CI | b | t | p | Mean | SE | 95% CI | b | t | p | |||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| LGB with less than college education | 98 | 1.012 | 0.18 | 0.65 | 1.38 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.003 | 3.99 | 0.42 | 3.13 | 4.84 | 2.21 | 0.42 | <0.0001 |

| LGB with some college education | 322 | 0.93 | 0.10 | 0.73 | 1.14 | 0.50 | 0.12 | <0.0001 | 3.24 | 0.20 | 2.85 | 3.64 | 1.47 | 0.22 | <0.0001 |

| LGB with college education or higher Heterosexual with less than college | 366 | 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.56 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.695 | 2.23 | 0.17 | 1.89 | 2.57 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.006 |

| education | 606 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.42 | 0.08 | <0.0001 | 2.85 | 0.17 | 2.51 | 3.18 | 1.07 | 0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Heterosexual with some college education | 1458 | 0.64 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.001 | 2.57 | 0.09 | 2.39 | 2.76 | 0.80 | 0.12 | <0.0001 |

| Heterosexual with college education or higher | 1716 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.53 | Reference | 1.78 | 0.08 | 1.63 | 1.93 | Reference | ||||

Note: LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual.

hsCRP - high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; CI - Confidence Interval; se - Standard Error.

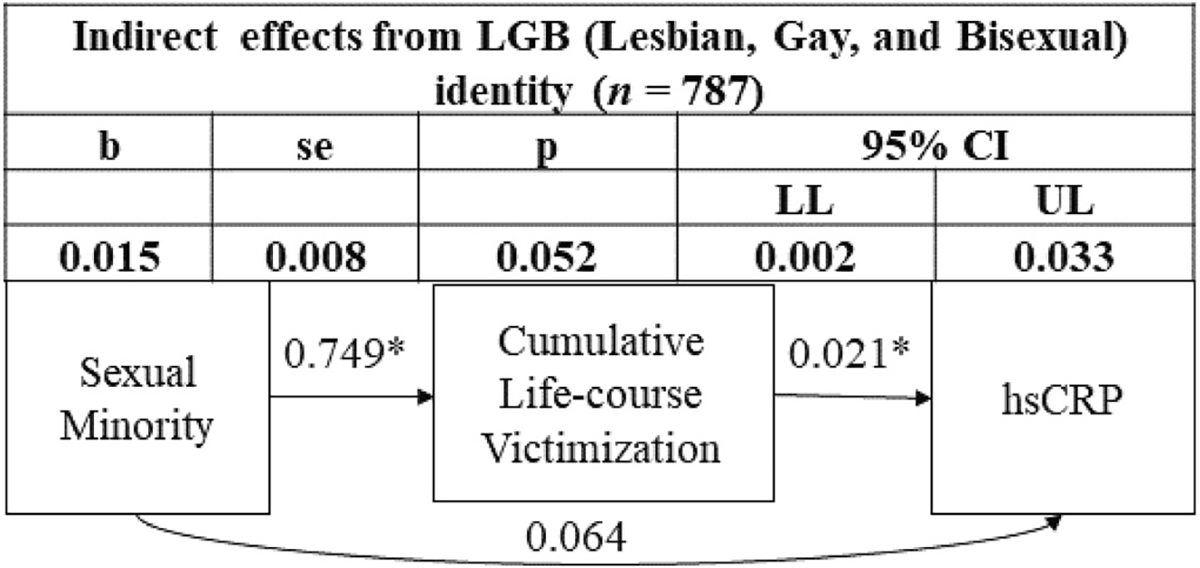

2.1. Associations between LGB identity, cumulative life-course victimization, and hsCRP

Table 3 summarizes direct effects and Fig. 1 summarizes results for indirect effects from model 1. LGB individuals did not have higher hsCRP compared to heterosexuals. However, LGB individuals did have higher cumulative life-course victimization and there was an indirect effect via cumulative life-course victimization on hsCRP for LGB individuals. Specifically, among LGB adults, higher burdens of cumulative life-course victimization were associated with increased hsCRP levels compared to heterosexuals.

Table 3.

Direct effects model for the association among cumulative life-course victimization, sexual orientation, and hsCRP (n = 4573).

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Predictors |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Biological sex: Male1 | −0.36 | 0.04 | 0.000 | −0.45 | −0.27 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.020 | 0.03 | 0.47 |

| Race: Black2 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.447 | −0.09 | 0.19 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.000 | 0.42 | 1.01 |

| Race: Hispanic2 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.051 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.050 | 0.02 | 0.66 |

| Race: Other2 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.953 | −0.22 | 0.21 | 0.81 | 0.26 | 0.002 | 0.32 | 1.34 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.660 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.326 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| Parent education in years | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.015 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.263 | −0.08 | 0.02 |

| Respondent education in years | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.009 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.02 | 0.000 | −0.22 | −0.14 |

| LGB: Yes3 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.348 | −0.07 | 0.20 | 0.75 | 0.14 | 0.000 | 0.48 | 1.00 |

| Recent infection: Yes4 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.27 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Body mass index | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.09 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cumulative life-course victimization | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.032 | 0.00 | 0.04 | – | – | – | – | – |

Note:

Female (Reference)

White (Reference)

Heterosexual (Reference)

No (Reference); LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual; hsCRP - high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; CI - Confidence Interval; se - Standard Error; LL-Lower Limit; UL-Lower Limit.

Fig. 1.

Indirect effects from LGB (Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual) identity to high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) via cumulative life-course victimization (Reference group: Heterosexual; n = 3786). * - p < 0.05.

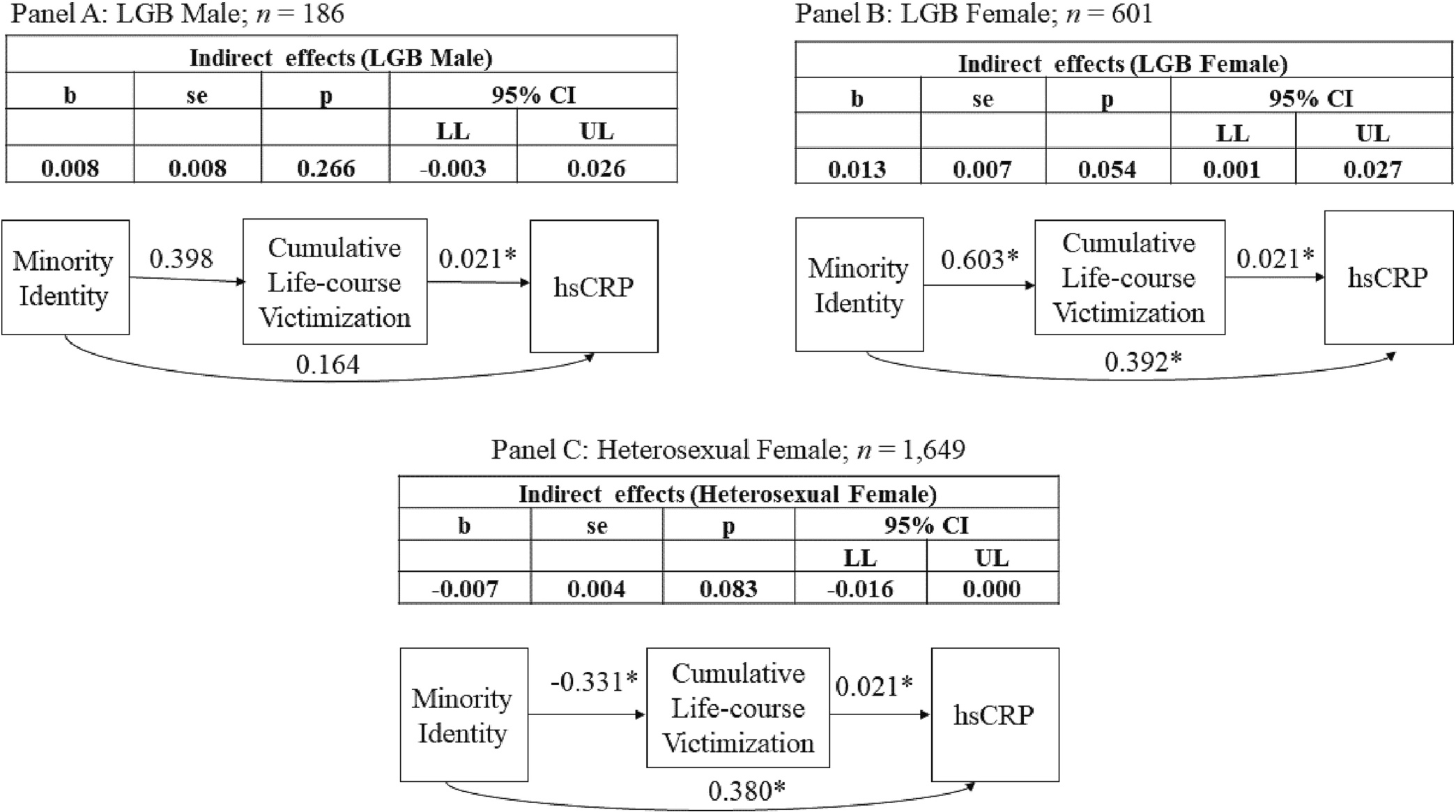

2.2. Associations between the intersection of LGB and gender, cumulative life-course victimization, and hsCRP

Table 4 and Fig. 2 summarize results from model 2 (direct and indirect effect respectively). Findings suggest that LGB females experienced higher rates of victimization and had higher levels of hsCRP (1.476 md/dl higher or exp0.390). Cumulative life-course victimization mediated the association between intersecting LGB and female identity and hsCRP. The intersection of LGB and female identity was associated with more cumulative life-course victimization which partially explained the observed direct association between LGB and female identity and higher hsCRP levels.

Table 4.

Direct effects model for the association among cumulative life-course victimization, sexual orientation by gender, and hsCRP (n = 4573).

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Predictors |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Race: Black1 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.458 | −0.09 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.000 | 0.42 | 1.02 |

| Race: Hispanic1 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.049 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 0.65 |

| Race: Other1 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.952 | −0.22 | 0.21 | 0.81 | 0.26 | 0.002 | 0.33 | 1.33 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.618 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.286 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| Parent education in years | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.016 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.256 | −0.08 | 0.02 |

| Respondent education in years | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.008 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.17 | 0.02 | 0.000 | −0.22 | −0.13 |

| LGB Male2 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.168 | −0.09 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.142 | −0.15 | 0.90 |

| LGB Female2 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 0.000 | 0.23 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.13 | 0.000 | 0.34 | 0.85 |

| Heterosexual Female2 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.29 | 0.48 | −0.33 | 0.11 | 0.004 | −0.56 | −0.11 |

| Recent infection: Yes3 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.27 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Body mass index | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.09 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cumulative life-course victimization | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.028 | 0.00 | 0.04 | – | – | – | – | – |

Note:

White (Reference)

Heterosexual and Male (Reference)

No (Reference); LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual; hsCRP - high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; CI - Confidence Interval; se - Standard Error; LL-Lower Limit; UL-Lower Limit.

Fig. 2.

Indirect effects from identity based on sexual orientation and gender to high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) via cumulative life-course victimization. Reference: Heterosexual and Male; (n = 2137). * - p < 0.05; LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual.

In contrast, heterosexual females had lower cumulative life-course victimization but high hsCRP (by a factor of 1.460 mg/dl or e0.379) and cumulative life-course victimization did not mediate the association between heterosexual female identity and hsCRP. LGB males did not differ on their cumulative life-course victimization from heterosexual males and there was no indirect association via cumulative life-course victimization for this group.

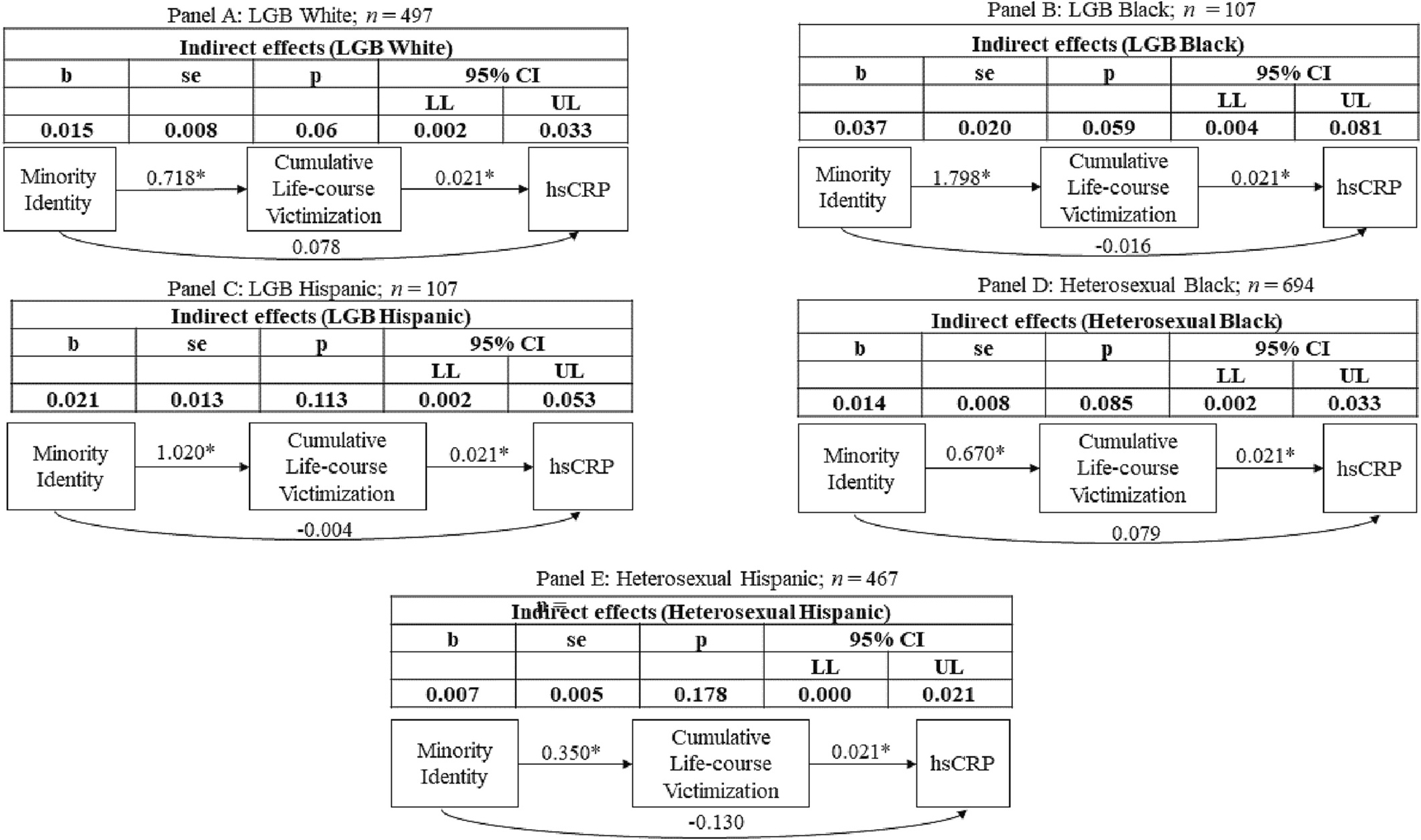

2.3. Associations between the intersection of LGB and race/ethnicity, cumulative life-course victimization, and hsCRP

Direct effects and indirect effects from model 3 are summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 3 respectively. The intersection of LGB identity with race/ethnicity was not associated with overall elevated levels of hsCRP. All intersectional groups based on race/ethnicity experienced higher levels of cumulative life-course victimization when compared to heterosexual and White individuals. Moreover, there was a marginally significant indirect effects through cumulative life-course victimization for hsCRP for adults who were LGB and White, and those that were LGB and Black. Specifically, for members of both groups, intersectional identity was associated with greater exposure to cumulative life-course victimization which in turn was associated with higher levels of hsCRP.

Table 5.

Direct effects model for the association among cumulative life-course victimization, sexual orientation by race/ethnicity, and hsCRP (n = 4573).

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Predictors |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Biological sex: Male1 | −0.36 | 0.04 | 0.000 | −0.45 | −0.27 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.013 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.670 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.338 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| Parent education in years | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.014 | −0.05 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.321 | −0.08 | 0.03 |

| Respondent education in years | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.010 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.17 | 0.02 | 0.000 | −0.22 | −0.13 |

| LGB and White2 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.391 | −0.10 | 0.24 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 0.000 | 0.39 | 1.03 |

| LGB and Black2 | −0.02 | 0.16 | 0.923 | −0.35 | 0.28 | 1.80 | 0.37 | 0.000 | 1.04 | 2.47 |

| LGB and Hispanic2 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.978 | −0.26 | 0.27 | 1.02 | 0.39 | 0.008 | 0.28 | 1.82 |

| Heterosexual and Black2 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.324 | −0.08 | 0.23 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.000 | 0.38 | 1.05 |

| Heterosexual and Hispanic2 | −0.13 | 0.07 | 0.070 | −0.28 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.052 | 0.01 | 0.70 |

| Recent infection: Yes3 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.27 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Body mass index | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.09 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cumulative life-course victimization | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.031 | 0.00 | 0.04 | – | – | – | – | – |

Note:

Female(Reference)

Heterosexual and White (Reference)

No (Reference); LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual; hsCRP - high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; CI - Confidence Interval; se - Standard Error; LL-Lower Limit; UL-Lower Limit.

Fig. 3.

Indirect effects from identity based on sexual orientation and race/ethnicity to high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) via cumulative life-course victimization.

Reference: Heterosexual White; (n = 2292). * - p < 0.05; LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual.

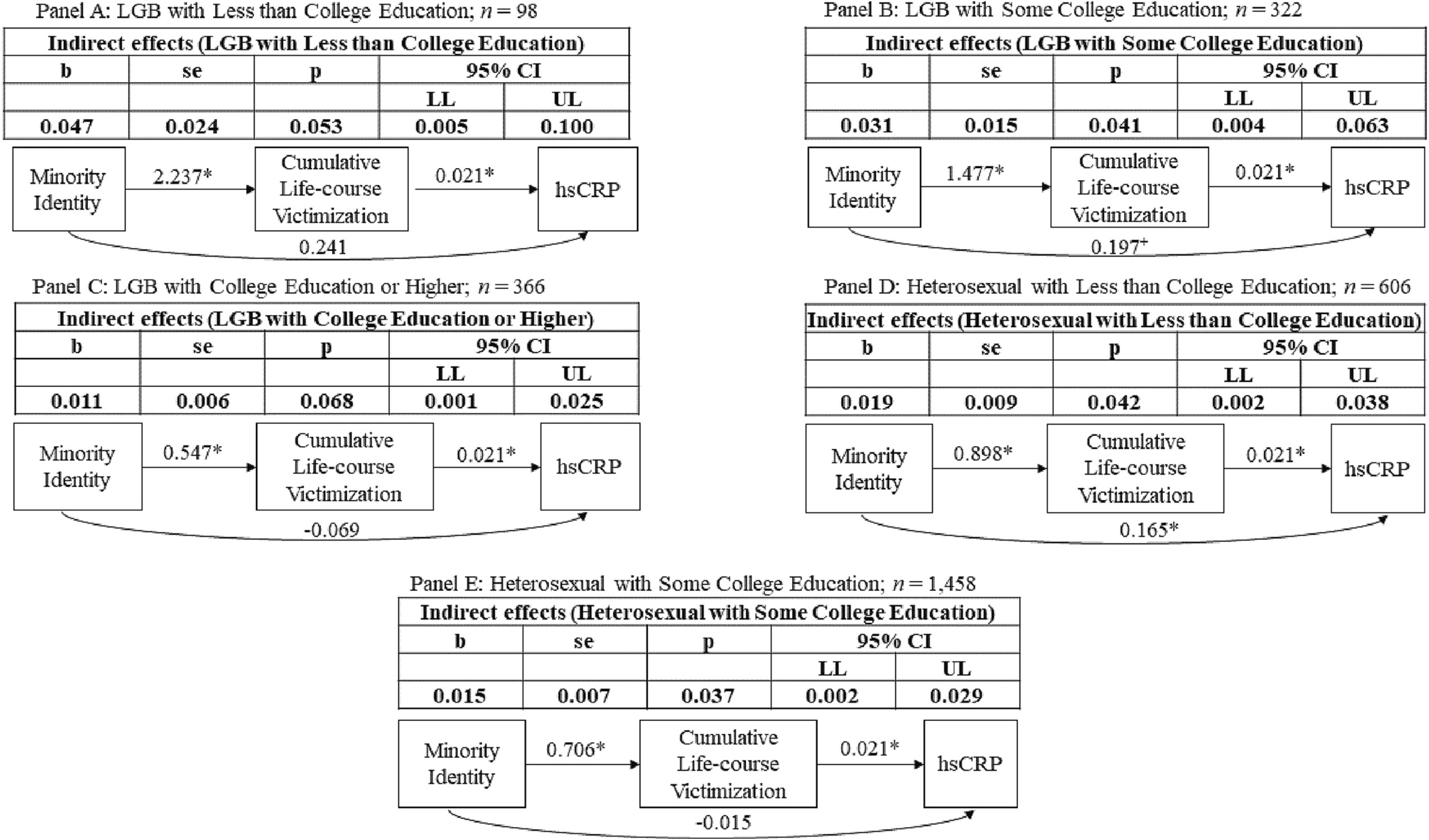

2.4. Associations between the intersection of LGB and educational attainment, cumulative life-course victimization, and hsCRP (Table 6 and Fig. 4)

Table 6.

Direct effects model for the association among cumulative life-course victimization, sexual orientation by educational attainment, and hsCRP (n = 4573).

| hsCRP | Cumulative life-course victimization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Predictors |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

b |

SE |

p |

95% CI |

||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Biological sex: Male1 | −0.36 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.45 | −0.27 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.49 |

| Race: Black2 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.42 | −0.09 | 0.19 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 1.02 |

| Race: Hispanic2 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.68 |

| Race: Other2 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.97 | −0.22 | 0.21 | 0.82 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 1.35 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.62 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.37 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Parent education in years | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.21 | −0.08 | 0.02 |

| LGB with less than college Education3 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.12 | −0.10 | 0.52 | 2.24 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 3.05 |

| LGB with some college Education3 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.39 | 1.48 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 1.92 |

| LGB with college education or Higher3 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.38 | −0.23 | 0.08 | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.88 |

| Heterosexual with less than college Education3 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 1.26 |

| Heterosexual with some college Education3 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.75 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.71 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.93 |

| Recent infection: Yes4 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.27 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Body mass index | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.09 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cumulative life-course victimization | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | – | – | – | – | – |

Note:

Female (Reference)

White (Reference)

Heterosexual with College Education or Higher (Reference)

No (Reference); LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual; hsCRP - high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; CI - Confidence Interval; se - Standard Error; LL-Lower Limit; UL-Lower Limit.

Fig. 4.

Indirect effects from identity based on sexual orientation and educational attainment to high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) via cumulative life-course victimization.

Reference: Heterosexual with College Education or Higher; (n = 1716). * - p < 0.05; + - p < 0.10; LGB - Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual.

All intersectional groups based on educational attainment were at greater risk for cumulative life-course victimization compared to heterosexuals with a college degree. Moreover, heterosexuals with less than college education had higher levels of inflammation (hsCRP) by a factor of 1.18 mg/dl (e0.17). Similarly, LGB individuals with some college education also had elevated hsCRP (1.22 mg/dl or e0.20) trending towards significance. Cumulative life-course victimization mediated the association between the following three groups and hsCRP:1) LGB with less than college education (trending, p = 0.06), 2) LGB with some college education, and 3) heterosexual with less than college education. There was an indirect association between heterosexual with some college education and hsCRP via cumulative life-course victimization. There was also a trending indirect association via cumulative life-course victimization for LGB adults with college or higher education.

3. Discussion

Utilizing a multi-theoretical framework two main aims were addressed. First, we examined cumulative life-course victimization as a mediator between LGB identity and low-grade inflammation during the transition to midlife. The second aim was to understand how the intersection of 1) LGB identity and gender, 2) LGB identity and race/ethnicity, and 3) LGB identity and educational attainment was associated with low-grade inflammation during the transition to midlife via cumulative life-course victimization.

Findings reveal that LGB identity was associated with higher cumulative life-course victimization which indirectly influenced the association between LGB identity and low-grade inflammation. Minority stress theory and the biopsychosocial minority stress framework supported by findings from previous research have proposed that victimization experiences among LGB individuals may be a function of exclusion, stigma, and discrimination (Christian et al., 2021; Meyer, 2003; Blondeel et al., 2018; Katz-Wise and Hyde, 2012; Langenderfer-Magruder et al., 2016) which then influence biological dysregulation such as low-grade inflammation and ultimately the untimely onset of diseases (Turner, 2009; Kuh et al., 2003; Danese et al., 2009; Hertzman and Boyce, 2010; Christian et al., 2021; Meyer, 2003; Danese et al., 2009). However, an examination of discrimination and stigma was beyond the scope of the present research and needs to be directly evaluated in future research to disentangle the role of discrimination in the victimization-inflammation associations observed.

Nonetheless, our findings are supported by the social safety perspectives for sexual and gender minority health. In line with this perspective, minority groups such as LGB adults may experience threats such as victimization that may result in biological responses such as elevated inflammatory responses, which become dysregulated over time as the threat (e.g., victimization) becomes chronic and more frequent (Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022). To elucidate, the body may initially respond with increased inflammatory response as a biological protective mechanism against victimization; however as the victimization (i.e., “social threat”) becomes chronic over time, the body’s natural inflammatory response remains active as an anticipation of the “social threat” even when there is no imminent threat (Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022).

Additionally, we found that the intersection of LGB identity with race/ethnicity (both Black and White), gender (female), and educational attainment (less than college education, some college education) was associated with greater frequency of cumulative life-course victimization. Based on the cumulative adversity model, social safety perspectives for sexual and gender minority health, and intersectionality theory, our results suggest that the intersection of multiple minority identities can lead to a greater accumulation of “social threats” over time including chronic victimization. (Turner, 2009; Kuh et al., 2003; Danese et al., 2009; Hertzman and Boyce, 2010; Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022) Specifically in this study, LGB females and LGB individuals with some college education were most vulnerable to low-grade inflammation during the transition to midlife, and cumulative life-course victimization partially explained this vulnerability for inflammation in both groups. These findings could be attributable to a combination of risks such as homophobia and sexism, or homophobia and income-related structural barriers that arise from low educational attainment (e.g., living in unsafe neighborhoods) that may lead to greater risk for “social threat” exposure and accumulation of victimization over time. (Turner, 2009; Kuh et al., 2003; Danese et al., 2009; Hertzman and Boyce, 2010; Christian et al., 2021; Meyer, 2003; Guan et al., 2021; Bauer et al., 2021; Blondeel et al., 2018; Katz-Wise and Hyde, 2012; Langenderfer-Magruder et al., 2016; Bluthenthal, 2021; Agadullina et al., 2021; Chapleau et al., 2008; Allen et al., 2009; Antai et al., 2014; Sallis et al., 2011; Guan et al., 2021) Such multiple identities linked to higher incidence of “social threats” like life-course violence victimization then contribute to even greater dysregulation of key stress-linked biological systems such as the immune system (Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022).

Findings from this research provide several critical avenues for future prevention and policy efforts. To elaborate, programmatic and prevention endeavors could focus on reducing exposure to violence and improving social safety (Diamond and Alley, 2022) among LGB individuals particularly those with additional vulnerabilities (females, Blacks, less than college education). Such programs and policies could include campaigns to increase awareness of the problem of victimization among LGB individuals particularly those disproportionately affected due to socio-political and cultural injustices (Crenshaw, 2018; Crenshaw, 1991; Guan et al., 2021). Moreover, greater access to community based resources for LGB individuals that are most vulnerable (e.g., LGB females), and interventions that identify victimization among LGB individuals from diverse backgrounds and address it urgently by providing safety and rehabilitation to victims (Pynoos and Nader, 1988; Voisin, 2007). Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting better mental health among LGB youth in states with policies that acknowledge the vulnerability of LGB individuals towards violence exposure (Meyer et al., 2019). Overall, prevention and policy efforts should be focused on preventing the negative impact of victimization among LGB individuals with multiple intersecting identities and reducing overall exposure to victimization among LGB individuals.

Additionally, factors such as mental health and substance use that have previously been linked to inflammation (Beurel et al., 2020; García-Calvo et al., 2020), violence victimization (Bhavsar and Ventriglio, 2017; Porcerelli et al., 2003), and LGB identity (Mendoza-Pérez and Ortiz-Hernández, 2019; Fish and Baams, 2018), should also be examined to better understand the victimization, and inflammation associations. Interestingly, we find that our proposed model from identity to low-grade inflammation via life-course cumulative victimization was not supported for individuals with LGB and Hispanic identity. The results replicate findings from previous research for Hispanic LGB individuals (Flores et al., 2020) and could be indicative of resilience mechanisms among LGB Hispanic individuals which need further examination.

3.1. Study limitations

There are several limitations to the current research. First, LGB identity was based on reports in adulthood, making it difficult to establish a causal link between LGB identity and violence victimization. Second, due to issues relating to statistical power, we were not able to distinguish among LGB individuals (e.g., Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual) and were not able to estimate associations within intersectional groups (e.g., examining race/ethnicity or educational attainment differences between males and females). Second, the use of secondary data limited the types of cumulative life-course victimization types that could be included in the analytic models. Third, the measurement of inflammation is restricted to one time point, and it may be important to understand change over time in inflammation levels as a function of cumulative life-course victimization to understand the role of victimization on chronic inflammation. Fourth, this study was limited to the examination of cumulative life-course victimization that combines childhood and early adulthood. However, differences may emerge as a function of development during childhood such as in infancy or during puberty, and future research should examine victimization exposure at sensitive developmental periods.

Even with these limitations the present research is unique and examines how divergent LGB identities influence cumulative life-course victimization and inflammation during the transition to midlife. This is the first study to examine the accumulation of victimization during childhood and early adulthood and its potential role in linking LGB intersectional identities to biological dysregulation and embedding. Such victimization related “biological embedding” during the transition to midlife among LGB adults with multiple minority identities can be critical for life-long health and well-being. (Turner, 2009; Kuh et al., 2003; Danese et al., 2009; Hertzman and Boyce, 2010; Diamond et al., 2021; Diamond and Alley, 2022)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

“This research uses data from Add Health, funded by grant P01 HD31921 (Harris) from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Add Health is currently directed by Robert A. Hummer and funded by the National Institute on Aging cooperative agreements U01AG071448 (Hummer) and U01AG071450 (Aiello and Hummer) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Add Health was designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F32HD103400 awarded to Aura Ankita Mishra. Harris and Halpern also received support from grant P01HD31921 (Harris) and R01HD087365 (Halpern).

We are also grateful to the Carolina Population Center for Training Support (T32HD091058) and for general support (P2CHD050924).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aura Ankita Mishra: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Carolyn T. Halpern: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Laura M. Schwab-Reese: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Kathleen Mullan Harris: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Ethical approval

The study uses secondary data from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) that was reviewed and deemed as exempt Category 4 by the Human Subjects Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107455.

Data availability

“Add Health adheres to the NIH policy on data sharing but due to the sensitive nature of Add Health data access is limited and governed by the Add Health data management security plan; therefore, authors are unable to provide Add Health data to journal editors. While authors may not provide Add Health data to the editors, they may provide the program code used to construct variables and analyze the data. Editors may obtain a copy of the data under the terms and conditions as described on the Add Health website at: https://addhealth.cpc.unc.edu/data/”.

References

- Acock AC, 2012. What to Do about Missing Values. [Google Scholar]

- Agadullina E, Lovakov A, Balezina M, Gulevich OA, 2021. Ambivalent sexism and violence toward women: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 819–859. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander-Floyd NG, 2012. Disappearing acts: reclaiming intersectionality in the social sciences in a post—black feminist era. Fem. Form. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Allen CT, Swan SC, Raghavan C, 2009. Gender symmetry, sexism, and intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence. 24 (11), 1816–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antai D, Antai J, Anthony DS, 2014. The relationship between socio-economic inequalities, intimate partner violence and economic abuse: a national study of women in the Philippines. Glob. Publ. Health. 9 (7), 808–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, 2013. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA., Schumacker RE. (Eds.), Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques, 1996. Psychology Press, pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JR, Arseneault L, Caspi A, et al. , 2018. Childhood victimization and inflammation in young adulthood: a genetically sensitive cohort study. Brain Behav. Immun. 67, 211–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Churchill SM, Mahendran M, Walwyn C, Lizotte D, Villa-Rueda AA, 2021. Intersectionality in quantitative research: a systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM-Popul. Heal. 14, 100798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Neriah Y, Karin M, 2011. Inflammation meets cancer, with NF-κB as the matchmaker. Nat. Immunol. 12 (8), 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Toups M, Nemeroff CB, 2020. The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: double trouble. Neuron. 107 (2), 234–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar V, Ventriglio A, 2017. Violence, victimization and mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 63 (6), 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder DA, 1983. On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. Int. Stat. Rev. Int. Stat. 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeel K, De Vasconcelos S, García-Moreno C, Stephenson R, Temmerman M, Toskin I, 2018. Violence motivated by perception of sexual orientation and gender identity: a systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 96 (1), 29–41L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, 2021. Structural racism and violence as social determinants of health: conceptual, methodological and intervention challenges. Drug Alcohol Depend. 222, 108681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapleau KM, Oswald DL, Russell BL, 2008. Male rape myths: the role of gender, violence, and sexism. J. Interpers. Violence. 23 (5), 600–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Harris KM, 2020. Guidelines for Analyzing Add Health Data. Carolina Popul Cent Univ North Carolina Chapel Hill. 10.17615/C6BW8W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christian LM, Cole SW, McDade T, et al. , 2021. A biopsychosocial framework for understanding sexual and gender minority health: a call for action. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 129, 107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HY, Kim DH, Lee EK, et al. , 2019. Redefining chronic inflammation in aging and age-related diseases: proposal of the senoinflammation concept. Aging Dis. 10 (2), 367–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K, 1991. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43 (6), 1241–1299. 10.2307/1229039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K, 2018. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989]. In: Feminist Legal Theory. Routledge, pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, et al. , 2009. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 163 (12), 1135–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Alley J, 2022. Rethinking minority stress: a social safety perspective on the health effects of stigma in sexually-diverse and gender-diverse population. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 138, 104720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Dehlin AJ, Alley J, 2021. Systemic inflammation as a driver of health disparities among sexually-diverse and gender-diverse individuals. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 129, 105215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA, 2000. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 118 (2), 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Clos TW, Mold C, 2004. C-reactive protein. Immunol. Res. 30 (3), 261–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KB, Miller GE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D, 2021. Maltreatment exposure across childhood and low-grade inflammation: considerations of exposure type, timing, and sex differences. Dev. Psychobiol. 63 (3), 529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser N, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J, Scheen AJ, Paquot N, 2014. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 105 (2), 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegood ED, Chen E, Kish J, et al. , 2020. Community violence and cellular and cytokine indicators of inflammation in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 115, 104628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Baams L, 2018. Trends in alcohol-related disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from 2007 to 2015: findings from the youth risk behavior survey. LGBT Heal. 5 (6), 359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores AR, Langton L, Meyer IH, Romero AP, 2020. Victimization rates and traits of sexual and gender minorities in the United States: results from the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017. Sci. Adv. 6 (40), eaba6910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe LK, Wallace JMW, Livingstone MBE, 2008. Obesity and inflammation: the effects of weight loss. Nutr. Res. Rev. 21 (2), 117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Campisi J, 2014. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 69 (Suppl_1), S4–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire MO, Van Dyke TE, 2013. Natural resolution of inflammation. Periodontology. 63 (1), 149–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Calvo X, Bolao F, Sanvisens A, et al. , 2020. Significance of markers of monocyte activation (CD163 and sCD14) and inflammation (IL-6) in patients admitted for alcohol use disorder treatment. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 44 (1), 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattamorta KA, Salerno JP, Castro AJ, 2019. Intersectionality and health behaviors among US high school students: examining race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and sex. J. Sch. Health 89 (10), 800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan A, Thomas M, Vittinghoff E, Bowleg L, Mangurian C, Wesson P, 2021. An investigation of quantitative methods for assessing intersectionality in health research: a systematic review. SSM-Popul. Heal. 16, 100977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel EA, et al. , 2019. Cohort profile: the National Longitudinal Study of adolescent to adult health (add health). Int. J. Epidemiol. 48 (5) 10.1093/ije/dyz115, 1415-1415k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy B, Freedman A, 2006. Infections. BMJ. 332 (7545), 838–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard-Garris N, Davis MM, Estabrook R, et al. , 2020. Adverse childhood experiences and biomarkers of inflammation in a diverse cohort of early school-aged children. Brain Behav. Immun. Health. 1, 100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath NM, Chesney SA, Gerhart JI, et al. , 2013. Interpersonal violence, PTSD, and inflammation: potential psychogenic pathways to higher C-reactive protein levels. Cytokine. 63 (2), 172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C, Boyce T, 2010. How experience gets under the skin to create gradients in developmental health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 31, 329–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute SAS, 2015. Base 9.4 Procedures Guide. SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Inwards-Breland DJ, Johns NE, Raj A, 2022. Sexual violence associated with sexual identity and gender among California adults reporting their experiences as adolescents and young adults. JAMA Netw. Open 5 (1), e2144266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapilashrami A, Hankivsky O, 2018. Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. Lancet. 391 (10140), 2589–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS, 2012. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: a meta-analysis. J. Sex Res. 49 (2–3), 142–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C, 2003. Life course epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 57 (10), 778–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenderfer-Magruder L, Walls NE, Whitfield DL, Brown SM, Barrett CM, 2016. Partner violence victimization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth: associations among risk factors. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 33 (1), 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, 2014. Handbook of Biological Statistics 3rd ed Sparky House Publishing. Balt MD. Available. http://www.biostathandbook.com/transformation.html. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Pérez JC, Ortiz-Hernández L, 2019. Violence as mediating variable iń mental health disparities associated to sexual orientation among Mexican youths. J. Homosex. 66 (4), 510–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129 (5), 674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Luo F, Wilson BDM, Stone DM, 2019. Sexual orientation enumeration in state antibullying statutes in the United States: associations with bullying, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts among youth. LGBT Heal. 6 (1), 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RE, Oudekerk BA, 2019. Criminal Victimization. 2018, 845. Bureau of Justice Statistics, pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B, 2020. Mplus. Compr Model Progr Appl Res User’s Guid, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Newton TL, Fernandez-Botran R, Miller JJ, Lorenz DJ, Burns VE, Fleming KN, 2011. Markers of inflammation in midlife women with intimate partner violence histories. J. Women’s Health 20 (12), 1871–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcerelli JH, Cogan R, West PP, et al. , 2003. Violent victimization of women and men: physical and psychiatric symptoms. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 16 (1), 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, Nader K, 1988. Psychological first aid and treatment approach to children exposed to community violence: research implications. J. Trauma. Stress. 1 (4), 445–473. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Slymen DJ, Conway TL, et al. , 2011. Income disparities in perceived neighborhood built and social environment attributes. Health Place 17 (6), 1274–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Reese LM, Currie D, Mishra AA, Peek-Asa C, 2021. A comparison of violence victimization and polyvictimization experiences among sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents and young adults. J. Interpers. Violence. 36 (11–12), NP5874–NP5891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Newman AB, 2011. Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 10 (3), 319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ, 2018. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front. Immunol. 9, 754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterzing PR, Ratliff GA, Gartner RE, McGeough BL, Johnson KC, 2017. Social ecological correlates of polyvictimization among a national sample of transgender, genderqueer, and cisgender sexual minority adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 67, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterzing PR, Gartner RE, Goldbach JT, McGeough BL, Ratliff GA, Johnson KC, 2019. Polyvictimization prevalence rates for sexual and gender minority adolescents: breaking down the silos of victimization research. Psychol. Violence 9 (4), 419. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, 2009. Understanding health disparities: The promise of the stress process model. In: Advances in the Conceptualization of the Stress Process. Springer, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, 2007. The effects of family and community violence exposure among youth: recommendations for practice and policy. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 43 (1), 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Whitsel EA, Angel R, O’hara R, Qu L, Carrier K, Harris KM, 2020. Add Health Wave V Documentation: Measures of Inflammation and Immune Function. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

“Add Health adheres to the NIH policy on data sharing but due to the sensitive nature of Add Health data access is limited and governed by the Add Health data management security plan; therefore, authors are unable to provide Add Health data to journal editors. While authors may not provide Add Health data to the editors, they may provide the program code used to construct variables and analyze the data. Editors may obtain a copy of the data under the terms and conditions as described on the Add Health website at: https://addhealth.cpc.unc.edu/data/”.