Abstract

Adopting health preventive actions is one of the most effective ways to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the theory of planned behavior and the orientation–stimulus–orientation–response model, this study investigated the mechanisms by which health information exposure influenced individuals to adopt self-protective behaviors in the context of infectious disease. In this research, a convenience sampling was used and 2265 valid samples (Male = 843, 68.9% of participants aged range from 18 to 24) were collected in China. Structural equation modeling analysis was performed, and the analysis showed that health consciousness positively influenced the subsequent variables through interpersonal discussions and social media exposure to COVID-19-related information. The interaction between interpersonal discussion and social media exposure was found to be positively associated with the elements of the theory of planned behavior and risk perception. The findings also revealed that self-protective behavior was positively predicted by the components of the theory of planned behavior and risk perceptions, with subjective norms serving as the main predictor, followed by attitudes and self-efficacy.

Keywords: Preventive behaviors, COVID-19, Health information exposure, O-S–O-R model, The theory of planned behavior

Introduction

The long-lasting COVID-19 pandemic has become a public health threat, posing significant challenges to the global disease prevention and control system (World Health Organization, 2020). By the end of 2022, there were over 645 million confirmed cases, and the pandemic had caused more than 6 million deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2022). The data, which behind it are fresh lives, has not announced the end of the COVID tragedy. For most population, the self-proactive behavior becomes crucial for ending the pandemic, as it can prevent the spread of the virus and lower the chance of the medical system collapsing (Figueroa, 2017). Especially, the importance of self-protective behaviors is emphasized again in the global trend of increasing openness rather than closure.

However, advocating self-initiated health protective measures in public is not an easy task. Although the government urges the masses to take self-protective measures, many people refuse to comply with the disease-control regulations (Kemmelmeier & Jami, 2021). Different from the west, the Chinese people are highly cooperative and supportive of these measures. This happens whether the zero-COVID policy lasts or is coming to an end (Mallapaty, 2022). It provides a meaningful and unique context for the investigation of whether and how communicative messages affect the adoption of self-protective behaviors among the Chinese population. Despite the mandatory aspects in the Chinese social norms, the extent to which individuals engage in preventive actions remains volitional and is influenced by individual antecedent factors (e.g., values, motivation, ideology) and exposure to COVID-19-related information (Cheng et al., 2021). Because self-protective measures are an effective way of dealing the COVID-19 infection, we used the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the orientation-stimulus-orientation-response model (O-S–O-R-M) in the current study to empirically examine the links among various variables that may influence people’s intention to take self-protective health measures (Meier et al., 2020). The current studies may shed light on the theoretical model development of health communication as well as provide valuable practical implications for health campaign practice and subsequent health education in the prevention of virus transmission.

Literature review

Theoretical basics: Integrating the TPB and the O-S–O-R-M

The parallels between the TPB and the O-S–O-R-M should not be ignored, despite the fact that they place different emphasis on understanding people’s behavioral intentions. First, both the TPB and O-S–O-R-M addressed the influence of preexisting individual attributes including the demographic characters, ideologies, consciousness, and values on individuals’ behavioral intentions. These preexisting attributes were defined as intrinsic factors in the TPB, and as pre-orientation factors in the O-S–O-R-M. Second, both two theoretical frameworks emphasized the effect of external information as critical stimuli influencing human’s behaviors. According to the TPB, an individual’s attitude is formed by stimuli from external environment, particularly through the information they have acquired (Connor & Sparks, 2005). Similarly, the O-S–O-R-M considers the extrinsic information stimuli to be a critical factor in determining audience’s behavioral decisions. As the media is an important carrier of information dissemination, both the TPB and O-S–O-R-M believe that information transmitted from the media will be an essential factor in stimulating specific behaviors of the audience. Due to the commonalities shared by these two theories, the relationship between the TPB and the O-S–O-R-M has been demonstrated in prior studies on health communication. For example, Huansuriya et al. (2014) investigated the impact of parental advertising exposure on adolescent marijuana use intentions and discovered that advertising exposure influenced parental intentions to initiate drug discussions with their children. By influencing parents’ attitudes and subjective norms toward drugs, and it will ultimately reduce adolescent marijuana use intentions. The essential variables of TPB have been consistently theorized in the O-S–O-R-M to mediate the effects of distal influencing factors from the media.

Although earlier research has shown the potential of combining the O-S–O-R-M with the TPB (Namkoong et al., 2017; Paek, 2008), there are limited studies that examines health issue in various circumstances. Besides, in terms of stimulus design, the previous studies mainly took the media and interpersonal communication factors separately, failing to capture the interaction effects of the two factors. As a result of the Chinese government’s severe control during the COVID-19 pandemic, people began transferring their offline interactions online. Accordingly, the interactive feature of communication with individuals’ interpersonal network and social media will be fully considered in this study to examine its influence on people’s cognition and intention toward the self-protective behaviors. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have employed the O-S–O-R-M and TPB integrated model to analyze the health issues in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hopefully, this study will help us to better understand the mechanism of health information exposure and its influence on people’s health cognition and self-protective behaviors.

The O-S–O-R-M

The O-S–O-R-M proposes that audience’s preexisting orientation and attitude will determine the extent to which it perceives and responds to an external stimulus (e.g., media message); the attitude and orientation generated by this stimulus, in turn, influences the effect of the stimulus on the audience’s response (Markus & Zajonc, 1985). The O-S–O-R-M considers both the direct and mediating effects of information exposure, as well as the antecedents and consequences of media information processing. It is particularly useful for explaining how people’s preexisting orientation influences their message reception or processing and how their post-orientation leads to intended outcomes (Paek et al., 2014).

The first O (O1) in the O-S–O-R-M refers to the set of cognitive and motivational characteristics that an audience perceives from its living environment, including the audience’s ideologies, worldviews, personal values, and psychological orientations, which may influence audience’s exposure to specific information (McLeod et al., 2009). The O1 represents people’s subjective responses to their cognition with regard to themselves and their social environments which can influence people’s information selection. Stimulus (S) encompasses media use and interpersonal communication, both of which influence audience cognition and perception, as well as their attitude and behavioral intention (Cho et al., 2009).The second O (O2) refers to a series of mediated cognitive and attitudinal factors (e.g., perceptions, attitudes, and subjective norms) stimulated by the external information (Lee & Kwak, 2014). The response (R) reflects how an individual intended and behaved in response to a particular social issue.

In the area of health communication, the O-S–O-R-M has been applied to explain issues such as organ donation (Yoo & Tian, 2011), weight control (Yoo, 2013), antismoking campaigns (Namkoong et al., 2017), physical activity (Wirtz et al., 2017), and childhood vaccination (Hwang & Shah, 2019). By utilizing the O-S–O-R-M to analyze the effects of antismoking media campaigns, Paek (2008) discovered people’s sensation-seeking and anti-smoking education (O1) influenced their exposure to anti-smoking messages (S), which in turn affected their smoking intentions (R) via the mediation of perceived peer smoking norms (O2). Wirtz et al. (2017) applied the O-S–O-R-M to physical activity and found that exercise identity (O1) influenced people’s selection of exercise-related media content (S), which ultimately influenced their physical activity (R) by affecting their conversations about media content (O2).

However, few studies have used the O-S–O-R-M to examine how people cope with the COVID-19 pandemic by engaging in personal self-protective behaviors. By using the O-S–O-R-M, this research therefore aims to investigate the process by which health information exposure affects people's adoption of health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, this study operationalized the O-S–O-R-M’s O1 as health consciousness; S as communication mediation elements including the communication with interpersonal network and social media information exposure; O2 as risk perception, self-efficacy, and subjective norms and attitudes, which contains a set of cognitive elements triggered by information stimuli; and R as the actual self-protective behaviors in coping with the COVID-19.

The TPB model

The TPB is one of the most influential and widely used models for predicting human behavior. According to the TPB, individual behavioral intentions are frequently explained by three factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

An individual’s attitude can be defined as their general evaluation of whether they are in favor of or against engaging in a particular behavior (Doll & Ajzen, 1992). Subjective norms refer to the perceived social pressures when the individual performs a behavior (Reinecke et al., 1996). The term “perceived behavioral control” (PBC) refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing an behavior, which reflects both prior experiences and any potential obstacles (Ajzen & Driver, 1992). As both self-efficacy and PBC are beliefs about one's capability to perform a behavior, Ajzen (2020) suggested that the two notions are conceptually indistinguishable. Moreover, a meta-analytic review of the efficacy of the TPB concluded that self-efficacy and PBC had equivalent impacts on intention and behavior and self-efficacy is more clearly defined (Armitage & Conner, 2001).Overall, the TPB explains that an individual is more likely to perform a behavior in reality if they have a positive dispositional attitude, a high level of perceived approval from other, and a strong self-efficacy.

The TPB is frequently used in health communication to investigate health-promoting behaviors and interventions in a variety of situations, such as the COVID-19 (Ahmad et al., 2020; Mueller et al., 2020). Ahmad et al. (2020) applied the TPB to examine the factors influencing individuals’ intention to take preventive measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. In their study, the government guidelines, risk perception, and pandemic knowledge were found to be the three most significant influences on people’s intention to take preventive measures. Additionally, Sumaedi et al. (2020) examined factors influencing people’s intention to comply with a “stay home” policy during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that the attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC were significantly associated with one’s intention to implement the policy.

In order to better understand the information exchanged during the COVID-19 pandemic and predict people’s adoption of self-protective behaviors, we applied the key components of TPB into the O2 in the current study. For developing the model, we used self-efficacy rather than PBC to assess its effects on people’s behavioral performance as previous research have confirmed its efficacy for predicting behavior in coping with health crises (Paek et al., 2010). Additionally, we combined the TPB elements with the risk perception on COVID-19 since people’s intentions for prevention are primarily influenced by their perceptions of the health risks posed by COVID-19.

Path from health consciousness to health information exposures (O1—S)

Health consciousness as pre-orientation

Health consciousness is defined as an individual’s awareness of his or her health conditions (Hong, 2009). A person with a higher level of health consciousness is more likely to recognize the importance of health, value health behaviors, and engage in them (Krishnan & Zhou, 2019). Moreover, the health consciousness is regarded as an important motivator for individuals to seek and exchange online health information via media technologies. It has been discovered that people who are more concerned about their health conditions would utilize the internet more frequently to seek the information they need. It further supports their health decisions (Cho et al., 2014). Next, we will use health consciousness as an antecedent in the O1 of our cognitive mediation model to see its association with COVID-19-related information exposure via social media and interpersonal network.

Health information exposure via social media as stimulus

During the pandemic (especially during a large-scale lockdown), social media has become an important channel for people to acquire COVID-19-related information. In the meantime, health consciousness played a crucial role in the Chinese public’s health information-seeking behaviors on social media (Zhang et al., 2020a). More specifically, Hong (2011) found that individuals with health consciousness are highly concerned about their own health conditions. This would motivate more health information seeking online. Therefore, we proposed the Hypothesis 1:

H1: Health consciousness positively influences individuals’ exposure to COVID-19-related health information via social media.

Health information exposure via interpersonal discussion as stimulus

In a stressful time like COVID-19 pandemic, people increasingly depend on each other (usually close friends and family members) for support (McKinley, 2020). Hence, aside from the information accessed via social media, exchanging information through interpersonal networks is another notable channel for health information acquisition (Dutta-Bergman, 2005). Given the interactive features of online and offline communication, individuals’ health consciousness may simultaneously influence both ways. However, the role of health consciousness in information seeking through offline channel were not sufficiently discussed in previous studies. Recently, Lee (2019) found that health consciousness will positively influence people’s access to health information through their interpersonal resources, whether online or offline. Thus, individuals with greater health consciousness are more likely to participate in offline interpersonal discussion with their families, friends, relatives, and beloved ones in their social life. Therefore, we therefore put up the Hypothesis 2:

H2: Health consciousness positively influences individuals’ interpersonal discussion on COVID-19.

The mediating path (S—O2)

From health information exposures to attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy

Information exposure from the media and interpersonal sources is considered an essential aspect in examining the effects on individuals’ cognition (Chernick et al., 2022), which can change or shape an individual’s beliefs on specific actions (Kim & Tandoc, 2022). The previous meta-analysis revealed that information exposure from social media significantly influences individuals’ subjective norms, attitudes, self-efficacy, and intentions for adopting health behaviors (Ridout & Campbell, 2018). For example, Yang and Wu (2021) explored the relationship between exposure to the health information on social media and Chinese people’s adoption of health protective behaviors in response to air pollution from the TPB perspective. They found that exposure to the health information on Weibo will lead to positive attitudes toward health protection, and the people’s attitudes and subjective norms will significantly predict their intention for mask-wearing. Similarly, the study by Namkoong et al. (2017), which examined the effectiveness of anti-smoking social media campaign, suggested that increased exposure to social media information will positively affect individuals’ attitudes and perceived social norms toward anti-smoking, leading to a decrease in their smoking intention. Besides the attitudes and perceived social norms, Niu et al. (2021) emphasized that usage of social media will help individuals in coping with uncertainty for health problems mediated by the self-efficacy. Regarding the COVID-19 pandemic context, exposure to the COVID-19-related information on social media may reinforce public’s attitudes, subjective social norms, and self-efficacy toward the self-protective behaviors. Therefore, we propose the Hypothesis 3:

H3: The extent of social media exposure on COVID-19-related information positively influences individuals’ (a) attitude, (b) subjective norm, (c) self-efficacy toward adopting the self-protective behaviors.

In addition to the social media exposure, past research has shown that interpersonal interaction with friends, colleagues and families will significantly affects the people’s perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs. To some extent, interpersonal communication serves as a way of reducing uncertainty during the health decision-making, which reflects individuals’ greater concerns about health issues (Jeong & Bae, 2018). Furthermore, Li and Li (2020) applied the extended TPB to examine Chinese women’s intentions to uptake the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, revealing that interpersonal discussion positively influenced people’s attitudes and intentions to accept the HPV vaccine. Moreover, Yee et al. (2019) introduced the factor of interpersonal communication between parents and children into the TPB model to predict children’s intentions of eating fruits and vegetables. Their research findings indicated a significant correlation between the TPB components and the active parental guidance during the parent–child conversation, which encourage youngsters to eat healthily.

Regarding the background of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is reasonable to assume that interpersonal discussions on the COVID-19-related topics may play an important role in shaping individual’s attitudes, subject norms and self-efficacy toward adopting self-protective behaviors. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: The extent of interpersonal discussion about COVID-19 positively influences individuals’ (a) attitude, (b) subjective norm, (c) self-efficacy toward adopting the self-protective behaviors.

From health information exposures to risk perception

To further improve the TPB model, we also consider risk perception as a necessary cognitive factor that is influenced by social media exposure and offline interpersonal discussion. It is because risk perception is an indispensable aspect of carrying out effective health campaigns, which highlights the public’s psychological tension when facing health threats. Several studies have examined the effect of media usage, particularly social media usage, on risk perception regarding infectious diseases, such as H1N1, MERS, and COVID-19 (Chang, 2012; Choi et al., 2017; Zeballos Rivas et al., 2021). It was found that social media exposure to related information about infectious diseases significantly enhanced individuals’ self-protective behaviors by positively influencing their risk perception (Chan et al., 2018). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: The extent of social media exposure on COVID-19-related information positively influences individuals’ risk perception of COVID-19.

Previous studies have also demonstrated that interpersonal discussion correlates with risk perception (Vyncke et al., 2017). For example, Lin et al. (2017) discussed how communication channels (e.g., media, interpersonal discussions) influence Singaporeans’ risk perception of haze and found that interpersonal discussion is tightly associated with risk perception. The study of Vyncke et al. (2017) also supported the relationship between interpersonal discussion and risk perception by comparing the impacts of 12 different information sources (e.g., media, interpersonal communication) on people’s health-related risk perception in the background of the Fukushima nuclear leak incident. Accordingly, we posit a positive relationship between the interpersonal discussion of COVID-19-related information and people’s risk perception toward the pandemic. Thus, we put up Hypothesis 6:

H6: The extent of interpersonal discussion on COVID-19-related topics positively influences individuals’ risk perception of COVID-19.

Predicting self-protective behaviors (O2—R)

Attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy as post-orientations

The TPB has been widely used in previous studies to explain factors that influence individuals’ intention to adopt healthy behaviors. For instance, Zhang et al. (2020b) applied the TPB to evaluate the intention of people who are at risk of being infected on self-quarantine, and the TPB was effective in predicting behavioral intention. A study by Aschwanden et al. (2021) examined the adoption of self-protective behaviors during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak and found the TPB showed a strong explanatory power on people’s behavioral intention as well. Hence, we posit that the elements of TPB will positively predict people’s self-protective behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic and propose the following hypotheses:

H7: Individuals’ (a) attitudes, (b) subjective norms, and (c) self-efficacy will positively influent their adoption of self-protective behaviors.

Risk perception as post-orientation

Moreover, protective motivation theory believes that risk perception is a key driver of health behaviors, which can motivate the individual to adopt protective behaviors amid health risks (Gong et al., 2020). As a result, when people have an adequate understanding of the risk posed by a disease, they are more likely to adopt health behaviors. Previous studies have confirmed that the effect of risk perception on people’s adoption of self-protective behaviors (Choi et al., 2018; de Bruin & Bennett, 2020). For example, Choi et al. (2018) found a negative relationship between risk perception toward the MERS and people’s intention to participate in outdoor activities in Korea. Wang et al. (2018) confirmed that the risk perception significantly influenced people’s intention to take actions in coping with the H7N9. With regard to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we propose the H8:

H8: Individuals’ risk perception of COVID-19 will positively influent their adoption of self-protective behaviors.

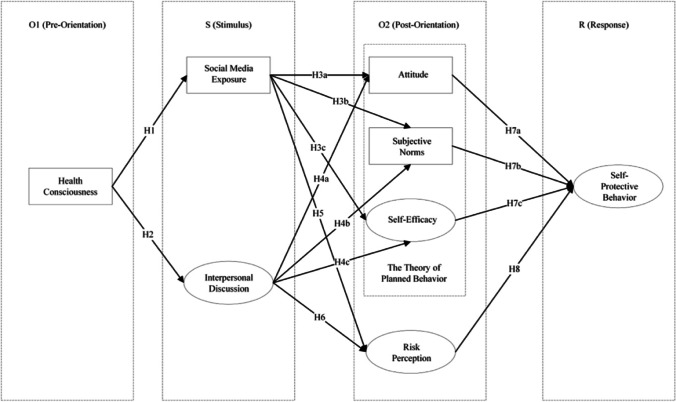

The theoretical model is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model

Method

Procedures and participants

The data was collected in Guangzhou, China from March 22 to March 31, 2022, when the city was undergoing a severe wave of COVID-19 outbreaks. Because of the strict lockdown at that time, this study cannot recruit participants face-to-face. Therefore, we a posted an online questionnaire weblink (supported by an online survey platform wjx.cn) in a university’s social networking site to recruit participants. Before proceeding to the survey questions, the participants provided informed consent. After finishing the questionnaire, every respondent was given a random amount of e-cash as a reward. To ensure the quality of data, samples with incomplete answers or questionnaire filling time less than 60 s were excluded by the online survey platform. This study finally received 2265 valid samples for the data analysis. This study was ethically approved by the corresponding author’s university to ensure the research project meets ethical requirements and privacy protection for the participants. The demographic characteristics of respondents were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample (N = 2265)

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 843 | 37.2 |

| Female | 1422 | 62.8 | |

| Age | Under 18 | 20 | 0.9 |

| 18–24 | 1560 | 68.9 | |

| 25–44 | 487 | 21.5 | |

| 45–64 | 186 | 8.2 | |

| Over 64 | 12 | 0.5 | |

| Education | High school or below | 171 | 7.5 |

| Undergraduate or college | 1794 | 79.2 | |

| Postgraduate or above | 300 | 13.3 |

Measures

Health consciousness

The measurement of health consciousness consists of seven items, which is adopted from a previous study (Hong, 2009). A 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) was used to evaluate the degree to which the respondents were concerned about their health conditions (e.g., “I’m very self-conscious about my health”) (α = 0.89, M = 5.81, SD = 0.99).

Interpersonal discussion

By referring to the previous research on interpersonal discussion (Yang et al., 2018), this study measured interpersonal discussion about COVID-19 by four items with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (all the time) to assess how often people discussed COVID-19-related information with others. For instance, “During the past month, how often did you receive information about COVID-19 in conversation with friends or family” (α = 0.72, M = 4.80, SD = 1.40).

Social media exposure

We used a single question to measure how often the respondents received COVID-19-related information from social media platforms with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (all the time) (Choi et al., 2018). For example, “During the past month, how often did you expose to information about COVID-19 on social media platforms” (M = 6.35, SD = 1.09).

Risk perception

The scale for assessing risk perception consists of seven items adapted from previous research (Oh et al., 2015). A 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used to evaluate the audience’s perceived severity and susceptibility to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., “I have felt risk from COVID-19 pandemic”) (α = 0.82, M = 5.57, SD = 1.05).

Self-efficacy

Drawing on previous research (Lee, 2019), self-efficacy towards COVID-19 was measured by four items with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely conform), evaluating the audience’s confidence in their ability to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., “I have the capability to cope with COVID-19 pandemic”) (α = 0.88, M = 5.87, SD = 1.02).

Subjective norms

Subjective norms was measured with a four-item scale adopted from the previous research (Rhodes et al., 2006). A 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used to evaluate whether closed others (e.g., families, friends, and beloved ones) will influence the respondents’ decisions to adopt self-protective behaviors (α = 0.92, M = 6.26, SD = 0.94).

Attitude

The attitude was measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) with seven semantic differential items (e.g. extremely unpleasant-extremely pleasant, extremely foolish- extremely wise) by asking a common stem (“For me the current social measures to prevent COVID-19 is …”) adopted by Chan et al. (2015) and White et al. (2009), which evaluated respondents’ mindsets and perceptions about adopting self-protective behaviors (α = 0.94, M = 6.24, SD = 0.94).

Self-protective behaviors

Respondents’ actual self-protective behaviors concerning COVID-19 were measured on 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (all the time) with thirteen items representing different self-protective behaviors (e.g. washing hands, wearing mask) recommended by the WHO and National Health Commission of China (Lin et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2021). For instance, participants will be required to evaluate the frequency on “how well did you implement the mask wearing during the latest three months” (α = 0.93, M = 6.44, SD = 0.79).

Results

Preliminary analysis

Before the hypothesis tests, we first performed the preliminary analyses to check missing data, normality, collinearity and detect outliers. There is no apparent pattern of missing data was found in this study. Regarding the detecting outliers, we used the Mahalanobis distance test to identify the multivariate outliers and did not find outliers in the current study. In terms of the normality, due to the larger sample (n = 2265) of this study we performed the normality test by adopting the indicators of skewness and kurtosis. According to the suggestion from Kim (2013), it is suggested to use the skew and kurtosis values to test normality for sample size larger than 300. The study variables were normally distributed because the values of kurtosis and skewness for each concept item were identified within the range (skew: < 2; kurtosis: < 7) (Curran et al., 1996). Moreover, we used the variance inflation factor (VIF) to test the multicollinearity among independent variables and did not find apparent collinearity among independent variables of this study (VIF range: 1.34 to 2.64).

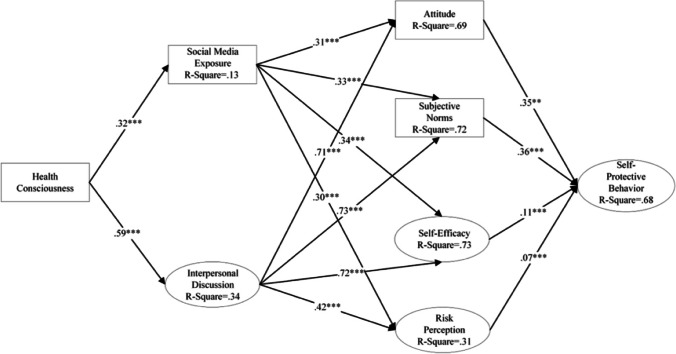

SEM analysis

Bivariate correlation test presented the associations between all variables (see Table 2) and revealed significant associations among the proposed variables. To test the proposed relationships, we further employed the structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 24. The resulting model is significant at the 0.001 level and explained 67.7% of the variance in individuals’ self-protective behavior. On referring to recommended index value, the other statistics all indicate that the data fit the model well: χ2/df= 1.44 < 5, GFI = 0.99 > 0.95, TLI = 0.99 > 0.95, CFI = 0.99 > 0.95, RMSEA = 0.01 < 0.08, and SRMR = 0.04 < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The overall results of SEM analysis are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations of model variables (N = 2265)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. health consciousness | - | |||||||

| 2. risk perception | .38** | - | ||||||

| 3. interpersonal discussion | .34** | .31** | - | |||||

| 4. social media exposure | .34** | .35** | .28** | - | ||||

| 5. self-efficacy | .53** | .35** | .29** | .43** | - | |||

| 6. subjective norm | .50** | .37** | .25** | .48** | .63** | - | ||

| 7. attitude | .49** | .37** | .22** | .45** | .63** | .73** | - | |

| 8. self-protective behavior | .47** | .31** | .23** | .43** | .54** | .66** | .64** | - |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Table 3.

SEM Results

| H | Path | Std β | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Health Consciousness | - > | Social Media Exposure | .32*** | 0.13 |

| H2 | - > | Interpersonal Discussion | .59*** | 0.34 | |

| H3a | Social Media Exposure | - > | Attitude | .31*** | 0.69 |

| H4a | Interpersonal Discussion | - > | .71*** | ||

| H3b | Social Media Exposure | - > | Subjective Norms | .33*** | 0.72 |

| H4b | Interpersonal Discussion | - > | .73*** | ||

| H3c | Social Media Exposure | - > | Self-Efficacy | .34*** | 0.73 |

| H4c | Interpersonal Discussion | - > | .72*** | ||

| H5 | Social Media Exposure | - > | Risk Perception | .30*** | 0.31 |

| H6 | Interpersonal Discussion | - > | .42*** | ||

| H7a | Attitude | - > | Self-Protective Behavior | .35*** | 0.68 |

| H7b | Subjective Norms | - > | .72*** | ||

| - > | |||||

| H7c | Self-Efficacy | - > | .73*** | ||

| - > | |||||

| H8 | Risk Perception | - > | .31*** | ||

| - > | |||||

***Path estimate is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed)

H1 and H2 posit that health consciousness will positively influence both social media exposure and interpersonal discussion. Our research findings support both of the hypotheses and suggest that health consciousness is positively associated with social media exposure (β = 0.32, p < 0.001) and interpersonal discussion (β = 0.59, p < 0.001).

H3 assumes that social media exposure will positively influence individual’s attitude, subjective norm, and self-efficacy toward self-protective behaviors. The results indicate that social media exposure is a positive predictor of attitude (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), subjective norm (β = 0.33, p < 0.001), and self-efficacy (β = 0.34, p < 0.001). Thus, H3 is supported.

In terms of H4, our results reveal that interpersonal discussion has a strong positive predictive power on attitude (β = 0.71, p < 0.001), subjective norm (β = 0.73, p < 0.001), and self-efficacy (β = 0.72, p < 0.001).

H5 proposes that social media exposure leads to increased risk perception of COVID-19. The results show that social media exposure has a positive influence on risk perception level (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). Hence, H5 is accepted.

Regarding the hypothesis that interpersonal discussion will positively influence risk perception, this study found that interpersonal discussion positively affects risk perception of COVID-19 (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), supporting H6.

Expectedly, attitude (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), subjective norm (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), and self-efficacy (β = 0.11, p < 0.001) are found to be positive predictors of self-protective behaviors. Therefore, H7 is supported.

When it comes to H8, a positive relationship between risk perception and self-protective behaviors (β = 0.07, p < 0.001) is found in our results. Thus, H8 is supported.

The visualized pathways of SEM are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

SEM of self-protective behaviors concerning COVID-19 (N = 2265). Note: All paths were found to be significant at p < .001

Discussion

This study has combined the frameworks from TPB and O-S–O-R-M to investigate the relationship between individuals’ cognitive factors, social media information exposure, interpersonal discussion, and individual’s self-protective behaviors in coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings demonstrated that health consciousness, risk perception, and TPB elements have significant positive associations with individuals’ self-protective behaviors. On the other hand, we have identified a correlation between interpersonal discussion and social media exposure (r = 0.28, p < 0.01), which mediated the path from health consciousness to risk perception and TPB elements. The health information exposure via social media/interpersonal discussion further posed an indirect, positive impact on individuals’ self-protective behaviors during the pandemic.

Health consciousness is an important factor affecting people’s health behaviors. It represents the degree to which people are concerned about their health. However, it has not received enough attention in the research of the COVID-19 context. Our findings firstly confirmed the influence of health consciousness on individuals’ active exposure to health information, which is consistent with previous research (Chang, 2020). Specifically, people who give more considerations of their health conditions are more likely to adjust their behaviors to prevent infections by frequent communications with others or extensively exposing themselves to COVID-19-related information on social media. Therefore, it is necessary to cultivate one’s health consciousness. This will encourage the public to adopt health preventive actions for against infection, especially in the context of global re-openness.

In light of the O-S–O-R-M, this research found that social media exposure and interpersonal communication play an important role in mediating the influence of individuals’ pre-oriented factors on their cognitive outcomes. Specifically, our findings revealed that social media exposure to COVID-19-related information and interpersonal discussion both have a positive impact on people’s risk perceptions and the three key elements of the TPB (attitude, subjective norm, and self-efficacy). The findings supported previous research that the richness of health information to which people are exposed during public health crises has a significant impact on people’s risk perception, self-efficacy, subjective norms, and attitudes (Zeballos Rivas et al., 2021). In other words, the masses’ health perceptions and behaviors are mainly shaped by the received information (Yang & Wu, 2021), whether from the media or from the interpersonal communication. Thus, it is a wise choice to increase one’s communication frequency in both online and offline ways. However, at the same time, individuals should identify health mis-/dis-information during the active information-seeking, reducing the negative impacts on their cognitions (Bin Naeem & Kamel Boulos, 2021).

Our findings then supported a positive pathway from health information exposure (both from social media and interpersonal discussion) to risk perception toward the COVID-19. According to Yang et al. (2018), the public’s risk perception is associated with information environment. In terms of Chinese context, the information environment (whether online or offline) was flooded with information about the severity of COVID-19 and the requirement of taking preventive measures in most of the time. This kind of information exposure of course would foster a higher level of risk perception among Chinese people.

This study also confirmed previous research findings that risk perception, self-efficacy, subjective norms, and attitudes positively predicted people’s health self-protective behaviors (de Bruin & Bennett, 2020; Li et al., 2021). With regard to the risk perception of COVID-19, individuals with higher risk perceptions are more likely to cope with uncertainty and anxiety by taking precautionary measures, which is consistent with the role of risk perception in promoting health behaviors under the health belief model. In terms of relationship between core elements of the TPB and self-protective behaviors, we found the subjective norm was the most powerful predictor. Tracing it to its cause, Chinese government has taken mandatory measures to restrict population movement and has mobilized people through various communication channels in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Gradually, the long-lasting compulsory regulations formed a social norm, creating invisible pressures on behavioral change in society. In addition, our findings as well confirmed the positive influence of self-efficacy and attitude on self-protective behaviors. Overall, the effectiveness of TPB in explaining individuals’ health cognitions and behaviors in the context of COVID-19 pandemic was proved in this research.

Implications and limitation

This study aims to provide novel insights for future research on health campaigns in tackling public health crises. To the best of our knowledge, this research pioneered the combination of extended TPB and the O-S–O-R-M for examining the integrated mechanisms that influence individuals’ self-protective behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hopefully, this study tries to help researchers better understand how social media, interpersonal communication, and post-oriented variables influence people’s health behaviors. Our resulting model explained 68% of variance change, which demonstrated a great explanatory power in researching the individuals’ health behaviors in the context of the pandemic. Overall, our study offers an orientation for the health communication research by intergrading different behavioral theories and models to address complex health problems.

Furthermore, this study improved the understanding of interactive communication and its effects in health prevention. Different form the existing studies which have mainly discussed the singular effect of social media (First et al., 2020; Melki et al., 2022), this study bridged both social media exposure and offline interpersonal discussion, illustrating the joint influence on individual’s cognition and adoption of self-protective behaviors.

Additionally, the findings of this study may provide practical insights for public health promotion and disease prevention. Given the importance of health consciousness as a pre-orientation factor in an individual’s health communication behavior, it is critical to employ effective strategies to raise people’s health awareness and draw public attention to adopting healthy lifestyle. In order to raise people’s confidence, knowledge, and risk awareness about COVID-19, it is necessary to improve health information transmission and utilize social media to generate more public discussion about the health topic. The interactive communication strategy that combines online and offline can potentially prompt the public to perceive the severity of external situations and take self-prevention measures.

While this study provided some insights, limitations of this research should be also pointed out. First, restricted to the cross-sectional study, we were unable to reach a general inference. The future studies should consider applying the longitudinal or experimental methods to examine the causal relationships of the variables in the OSOR model. Second, the study’s use of a student sample makes it difficult to reach a generalizable result to the whole population, but Basil et al. (2002) found no distinct gap between the results of multivariate relationships from a student sample and that of a random sample of the general population. Lastly, regarding our measurement of health information on social media, this study only took the most popular social media platform (WeChat) into account and did not consider the information from different social media types. For future studies, it is a good practice to include multiple types of social media to examine the divergent effects of different information sources on audiences.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge for the support from the foundation for Macao Higher Education Institutions in the Area of Research in Humanities and Social Science (Number: DSEDJ-23-005-FA). We are grateful for the financial support from the Government of the Macao Special Administrative Region Education and Youth Development Bureau.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to restriction of research foundation but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ehical Statement

We declare that the submitted work is original and ethically approved by the Faculty of Humanities and Arts at Macau University of Science and Technology. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The confidentiality and privacy of participants is well protected. The work is financially supported by the foundation for Macao Higher Education Institutions in the Area of Research in Humanities and Social Science (Number: DSEDJ-23–005-FA). There are no other conflicts of interest in the materials discussed in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmad M, Iram K, Jabeen G. Perception-based influence factors of intention to adopt COVID-19 epidemic prevention in China. Environmental Research. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2020;2(4):314–324. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Driver BL. Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. Journal of Leisure Research. 1992;24(3):207–224. doi: 10.1080/00222216.1992.11969889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschwanden, D., Strickhouser, J. E., Sesker, A. A., Lee, J. H., Luchetti, M., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2021). Preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with perceived behavioral control, attitudes, and subjective norm. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 662835. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.662835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Basil MD, Brown WJ, Bocarnea MC. Differences in univariate values versus multivariate relationships. Human Communication Research. 2002;28(4):501–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00820.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bin Naeem, S., & Kamel Boulos, M. N. (2021). COVID-19 Misinformation online and health literacy: A brief overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15). 10.3390/ijerph18158091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chan DK, Yang SX, Mullan B, Du X, Zhang X, Chatzisarantis NL, Hagger MS. Preventing the spread of H1N1 influenza infection during a pandemic: Autonomy-supportive advice versus controlling instruction. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;38(3):416–426. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9616-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MS, Winneg K, Hawkins L, Farhadloo M, Jamieson KH, Albarracin D. Legacy and social media respectively influence risk perceptions and protective behaviors during emerging health threats: A multi-wave analysis of communications on Zika virus cases. Social Science & Medicine. 2018;212:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. News coverage of health-related issues and its impacts on perceptions: Taiwan as an example. Health Communication. 2012;27(2):111–123. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.569004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. Self-control-centered empowerment model: Health consciousness and health knowledge as drivers of empowerment-seeking through health communication. Health Communication. 2020;35(12):1497–1508. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1652385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ZJ, Zhan Z, Xue M, Zheng P, Lyu J, Ma J, Zhang XD, Luo W, Huang H, Zhang Y, Wang H, Zhong N, Sun B. Public health measures and the control of COVID-19 in China. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernick, L. S., Konja, A., Gonzalez, A., Stockwell, M. S., Ehrhardt, A., Bakken, S., Westhoff, C. L., Dayan, P. S., & Santelli, J. (2022). Designing illustrative social media stories to promote adolescent peer support and healthy sexual behaviors. Digital Health, 8. 10.1177/20552076221104660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cho, J., Park, D., & Lee, H. E. (2014). Cognitive factors of using health apps: Systematic analysis of relationships among health consciousness, health information orientation, eHealth literacy, and health app use efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5), e125. 10.2196/jmir.3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cho J, Shah DV, McLeod JM, McLeod DM, Scholl RM, Gotlieb MR. Campaigns, reflection, and deliberation: Advancing an OSROR model of communication effects. Communication Theory. 2009;19(1):66–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.01333.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.-H., Shin, D.-H., Park, K., & Yoo, W. (2018). Exploring risk perception and intention to engage in social and economic activities during the South Korean MERS outbreak. International Journal of Communication, 12, 3600–3621. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/8661.

- Choi DH, Yoo W, Noh GY, Park K. The impact of social media on risk perceptions during the MERS outbreak in South Korea. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;72:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor, M., & Sparks, P. (2005). Theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour. In: Conner, M., Paul, N. (Eds.), Predicting Health Behaviour (2nd ed., pp. 170–222). Open University Press.

- Curran, P., West, S., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(16). 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16.

- de Bruin WB, Bennett D. Relationships between initial COVID-19 risk perceptions and protective health behaviors: A national survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020;59(2):157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll J, Ajzen I. Accessibility and stability of predictors in the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(5):754–765. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.5.754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman MJ. Developing a profile of consumer intention to seek out additional information beyond a doctor: The role of communicative and motivation variables. Health Communication. 2005;17(1):1–16. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1701_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa ME. A theory-based socioecological model of communication and behavior for the containment of the Ebola epidemic in Liberia. Journal of Health Communication. 2017;22(sup1):5–9. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1231725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First JM, Shin H, Ranjit YS, Houston JB. COVID-19 stress and depression: Examining social media, traditional media, and interpersonal communication. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2020;26(2):101–115. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1835386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Veuthey J, Han Z. What makes people intend to take protective measures against influenza? Perceived risk, efficacy, or trust in authorities. American Journal of Infection Control. 2020;48(11):1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H. (2009). Scale development for measuring health consciousness: Re-conceptualization . The 12th Annual International Public Relations Research Conference, Coral Gables, Florida. https://bit.ly/3R499Wh.

- Hong H. An extension of the extended parallel process model (EPPM) in television health news: The influence of health consciousness on individual message processing and acceptance. Health Communication. 2011;26(4):343–353. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.551580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huansuriya T, Siegel JT, Crano WD. Parent–child drug communication: Pathway from parents' ad exposure to youth's marijuana use intention. Journal of Health Communication. 2014;19(2):244–259. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.811326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Shah DV. Health information sources, perceived vaccination benefits, and maintenance of childhood vaccination schedules. Health Communication. 2019;34(11):1279–1288. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1481707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong M, Bae RE. The effect of campaign-generated interpersonal communication on campaign-targeted health outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health Communication. 2018;33(8):988–1003. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1331184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmelmeier, M., & Jami, W. A. (2021). Mask wearing as cultural behavior: An investigation across 45 US states during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim H-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics. 2013;38(1):52–54. doi: 10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Tandoc EC., Jr Wear or not to wear a mask? Recommendation inconsistency, government trust and the adoption of protection behaviors in cross-lagged TPB models. Health Communication. 2022;37(7):833–841. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1871170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Zhou X. Modeling the effect of health antecedents and social media engagement on healthy eating and quality of life. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2019;47(4):365–380. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2019.1654124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Kwak N. The affect effect of political satire: Sarcastic humor, negative emotions, and political participation. Mass Communication and Society. 2014;17(3):307–328. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2014.891133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. “Self” takes it all in mental illness: Examining the dynamic role of health consciousness, negative emotions, and efficacy in information seeking. Health Communication. 2019;34(8):848–858. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1437528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liu X, Zou Y, Deng Y, Zhang M, Yu M, Wu D, Zheng H, Zhao X. Factors affecting COVID-19 preventive behaviors among university students in Beijing, China: An empirical study based on the extended theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(13):7009. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18137009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Li J. Factors affecting young Chinese women's intentions to uptake human papillomavirus vaccination: An extension of the theory of planned behavior model. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2020;16(12):3123–3130. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1779518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TTC, Li L, Bautista JR. Examining how communication and knowledge relate to Singaporean youths’ perceived risk of haze and intentions to take preventive behaviors. Health Communication. 2017;32(6):749–758. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1172288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C., Imani, V., Majd, N. R., Ghasemi, Z., Griffiths, M. D., Hamilton, K., Hagger, M. S., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). Using an integrated social cognition model to predict COVID‐19 preventive behaviours. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25(4). 10.1111/bjhp.12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mallapaty S. China is relaxing its zero-COVID policy — here’s what scientists think. Nature. 2022;612:383–384. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-04382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H., & Zajonc, R. B. (1985). The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology (3rd ed., pp. 137–230). Random House.

- McKinley, G. P. (2020). We need each other: Social supports during COVID 19. Social Anthropology, 28(2). 10.1111/1469-8676.12828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McLeod, D. M., Kosicki, G. M., & McLeod, J. M. (2009). Political communication effects. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media Effects:Advance in Theory and Research (3rd ed., pp. 228-251). Routledge.

- Meier, K., Glatz, T., Guijt, M. C., Piccininni, M., van der Meulen, M., Atmar, K., Jolink, A. T. C., Kurth, T., Rohmann, J. L., Najafabadi, A. H. Z., & Grp, C. S. S. (2020). Public perspectives on protective measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands, Germany and Italy: A survey study. PLoS One, 15(8), e0236917. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Melki, J., Tamim, H., Hadid, D., Farhat, S., Makki, M., Ghandour, L., & Hitti, E. (2022). Media exposure and health behavior during pandemics: The mediating effect of perceived knowledge and fear on compliance with COVID-19 prevention measures. Health Commun,37(5), 586–596. 10.1080/10410236.2020.1858564 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mueller J, Davies A, Jay C, Harper S, Todd C. Evaluation of a web-based, tailored intervention to encourage help-seeking for lung cancer symptoms: a randomised controlled trial. Digital Health. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2055207620922381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkoong, K., Nah, S., Record, R. A., & Van Stee, S. K. (2017). Communication, reasoning, and planned behaviors: Unveiling the effect of interactive communication in an anti-smoking social media campaign. Health Communication,32(1), 41–50. 10.1080/10410236.2015.1099501 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Niu, Z., Willoughby, J., & Zhou, R. (2021). Associations of health literacy, social media use, and self-efficacy with health information–seeking intentions among social media users in China: Cross-sectional survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research,23(2), e19134. 10.2196/19134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.-H., Paek, H.-J., & Hove, T. (2015). Cognitive and emotional dimensions of perceived risk characteristics, genre-specific media effects, and risk perceptions: the case of H1N1 influenza in South Korea. Asian Journal of Communication,25(1), 14–32. 10.1080/01292986.2014.989240

- Paek, H.-J. (2008). Mechanisms through which adolescents attend and respond to antismoking media campaigns. Journal of Communication,58(1), 84–105. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00375.x

- Paek, H.-J., Hilyard, K., Freimuth, V., Barge, J. K., & Mindlin, M. (2010). Theory-based approaches to understanding public emergency preparedness: Implications for effective health and risk communication. Journal of Health Communication,15(4), 428–444. 10.1080/10810731003753083 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Paek H-J, Lee H, Hove T. The role of collectivism orientation in differential normative mechanisms: A cross-national study of anti-smoking public service announcement effectiveness. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2014;17(3):173–183. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke J, Schmidt P, Ajzen I. Application of the theory of planned behavior to adolescents' condom use: A panel study1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26(9):749–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Matheson DH. A multicomponent model of the theory of planned behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11(1):119–137. doi: 10.1348/135910705X52633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout, B., & Campbell, A. (2018). The use of social networking sites in mental health interventions for young people: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research,20(12), e12244. 10.2196/12244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sumaedi, S., Bakti, I. G. M. Y., Rakhmawati, T., Widianti, T., Astrini, N. J., Damayanti, S., Massijaya, M. A., & Jati, R. K. (2020). Factors influencing intention to follow the “stay at home” policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Health Governance, 26(1), 13–27. 10.1108/IJHG-05-2020-0046

- Vyncke B, Perko T, Van Gorp B. Information sources as explanatory variables for the health-related risk perception of the Fukushima nuclear accident. Risk Analysis. 2017;37(3):570–582. doi: 10.1111/risa.12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Wei J, Shi X. Compliance with recommended protective actions during an H7N9 emergency: a risk perception perspective. Disasters. 2018;42(2):207–232. doi: 10.1111/disa.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KM, Smith JR, Terry DJ, Greenslade JH, McKimmie BM. Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;48(1):135–158. doi: 10.1348/014466608X295207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, J. G., Wang, Z., & Kulpavarapos, S. (2017). Testing direct and indirect effects of identity, media use, cognitions, and conversations on self-reported physical activity among a sample of hispanic adults. Health Communication,32(3), 298–309. 10.1080/10410236.2016.1138377 [DOI] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2020). 10 global health issues to track in 2021. Retrieved March 2022, from: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/10-global-health-issues-to-track-in-2021

- World Health Organization. (2021). Advice for Public. Retrieved March 2022, from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved December 2022, from: https://covid19.who.int

- Yang, C., Dillard, J. P., & Li, R. B. (2018). Understanding fear of Zika: Personal, interpersonal, and media influences. Risk Analysis,38(12), 2535–2545. 10.1111/risa.12973 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q., & Wu, S. (2021). How social media exposure to health information influences Chinese people’s health protective behavior during air pollution: A theory of planned behavior perspective. Health Communication,36(3), 324–333. 10.1080/10410236.2019.1692486 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yee, A. Z. H., Lwin, M. O., & Lau, J. (2019). Parental guidance and children’s healthy food consumption: Integrating the theory of planned behavior with interpersonal communication antecedents. Journal of Health Communication, 24(2), 183–194. 10.1080/10810730.2019.1593552 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J. H. (2013). No clear winner: Effects of the biggest loser on the stigmatization of obese persons. Health Communication, 28(3), 294–303. 10.1080/10410236.2012.684143 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J. H., & Tian, Y. (2011). Effects of entertainment (mis) education: exposure to entertainment television programs and organ donation intention. Health Communication, 26(2), 147–158. 10.1080/10410236.2010.542572 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zeballos Rivas, D. R., Lopez Jaldin, M. L., Nina Canaviri, B., Portugal Escalante, L. F., Alanes Fernandez, A. M. C., & Aguilar Ticona, J. P. (2021). Social media exposure, risk perception, preventive behaviors and attitudes during the COVID-19 epidemic in La Paz, Bolivia: A cross sectional study. PLoS One, 16(1), e0245859. 10.1371/journal.pone.0245859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Jung, E. H., & Chen, Z. (2020a). Modeling the pathway linking health information seeking to psychological well-being on wechat. Health Communication, 35(9), 1101–1112. 10.1080/10410236.2019.1613479 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., Wang, F., Zhu, C., & Wang, Z. (2020b). Willingness to self-isolate when facing a pandemic risk: Model, empirical test, and policy recommendations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1). 10.3390/ijerph17010197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to restriction of research foundation but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.