Abstract

Purpose of review:

This scoping review of reviews aimed to detail the breadth of violence research about sexual and gender minorities (SGM) in terms of the three generations of health disparities research (i.e., documenting, understanding, and reducing disparities).

Recent findings:

Seventy-three reviews met inclusion criteria. Nearly 70% of the reviews for interpersonal violence and for self-directed violence were classified as first-generation studies. Critical third-generation studies were considerably scant (7% for interpersonal violence and 6% for self-directed violence).

Summary:

Third-generation research to reduce or prevent violence against SGM populations must account for larger scale social environmental dynamics. Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data collection has increased in population-based health surveys, but administrative datasets (e.g., health care, social services, coroner and medical examiner offices, law enforcement) must begin including SOGI to meet the needs of scaled public health interventions to curb violence among SGM communities.

Keywords: violence, suicide, sexual and gender minorities, health inequities

INTRODUCTION

Violence, both interpersonal and self-directed, is an enduring public health problem in the United States. In 2019 alone, 66,652 people died from violence, incurring approximately $672 billion in costs to society.(1) However, violence does not affect all communities equally, and a considerable amount of research reveals disproportionate rates of violence affecting people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). In recent years, the LGBT abbreviation has broadened to sexual and gender minority (SGM) to encompass the heterogeneity of identities and experience, such as people who identify as gender non-binary or gender non-conforming or identify as queer or pansexual.(2) For the purposes of this review, SGM will be used unless referring to studies that focused on specific sub-populations.

Interpersonal violence against SGM people, driven by bias, is a well-known phenomenon,(3) but most research has been limited to convenience-based sampling. From Miller & Humphries’ initial attempt in 1980 to stoke empirical study in gay men’s victimization,(4) nearly four decades would pass before sexual orientation data were gathered in the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) for the first time 2017. The results from the NCVS,(5) utilizing robust nationally-representative sampling, corroborated findings from numerous studies about interpersonal violence among sexual minorities gathered through convenience samples.

Similarly for self-directed violence, in 1999 Remafedi questioned whether the scientific community could end equivocal questions about disparities in suicide risk for sexual minorities, with the evidence at that time seemingly compelling and concordant.(6) Here again, it would take 16 years for sexual orientation data collection to be added to the National Survey of Drug Use and Health,(7) the only ongoing population-based survey in the U.S. that includes surveillance of suicidal ideation and attempt. Concomitantly, additions of sexual orientation items to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Survey in 2015 finally equipped researchers to examine both suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and peer victimization among sexual minority adolescents.(8)

Thus, disparities in violence have been clarified through the gold standard of probability-based sampling, but largely only within the last 5 years in the U.S. and after decades of research by scientists forced to use convenience samples due to lack of available data from national surveys.(9) Consequently, framing violence research among SGM populations remains unclear despite a flurry of individual studies and seemingly numerous reviews of them.

One framework for health disparities research created by Kilbourne and colleagues, outlines a three-generation approach.(10) In the first generation, disparities are detected – i.e., evidence that a disparity exists. Subsequent second-generation studies aim to understand the factors driving disparities, which then informs third-generation studies that target those driving forces through interventions to reduce the disparities. By placing research studies along this continuum, one can observe both where progress occurs and where research seemingly has stalled.

This scoping review was guided with the question “What is the breadth of research reviews about violence among SGM populations?” There were two main reasons for conducting a scoping review rather than a systematic review of reviews. First, the intent of the review was not to answer specific questions about prevalence or incidence of violence or effectiveness of interventions. Second, within the two main categories of interpersonal and self-directed violence, there are further categories of violence, (e.g., within interpersonal violence, there is intimate partner violence, peer victimization, childhood abuse). Thus a scoping review aligned best with an endeavor “to provide an overview or map of the evidence.”(11)

METHODS

The author conducted an initial search on December 1, 2021 to review titles and abstracts and repeated the search on February 1, 2022 to assure no new reviews had been published in the time during the manuscript development. January 1, 1990 was selected as the starting point because it was unlikely that the literature on SGM individuals was populated or developed enough by that time point to lend itself for reviews. A simultaneous search of several databases was conducted, including Scopus, IngentaConnect, Medline, ProQuest, SAGE Premier, Web of Science, JSTOR, LGBTQ+ Source.

Based on the overarching research question, the literature search consisted of three main terms for: population (“sexual minority” OR “sexual minorities” OR “gender minority” OR “gender minorities” OR transgender OR nonconform* OR lesbian* OR gay* OR bisexual* OR lgb* OR “men who have sex with men” OR “women who have sex with women” OR MSM OR WSW OR “same-sex” OR “sexual orientation” OR “gender identity”), type of study (review OR meta-analysis), and topical focus (violen* OR abuse OR victim* OR suic* OR harm OR injury OR assault OR crime OR injury OR homicide).

Inclusion criteria were: (a) must be a scientific review (e.g., systematic, meta-analysis, scoping); (b) explained search criteria (e.g., databases, search terms, time period searched); (c) written in English; (d) published in a peer-reviewed journal. Despite limiting inclusion to studies published in English, there was no exclusion based on country or locale. The references of included articles were scanned for any studies potentially missed in the initial search.

In addition to key characteristics of each review to assess the breadth of research (e.g., years of search, number of studies included, countries included in the review), each review was coded regarding whether its scope aligned with first generation (i.e., documenting), second generation (i.e., understanding), or third generation (i.e., reducing) health disparities research.(10) Lastly, key findings of each review are summarized based on data supplied in each original study: for first generation studies, summaries of prevalence were extracted; for second generation studies, examples of risk factors identified by each review were extracted; for third generation studies, narrative summaries of findings were extracted.

RESULTS

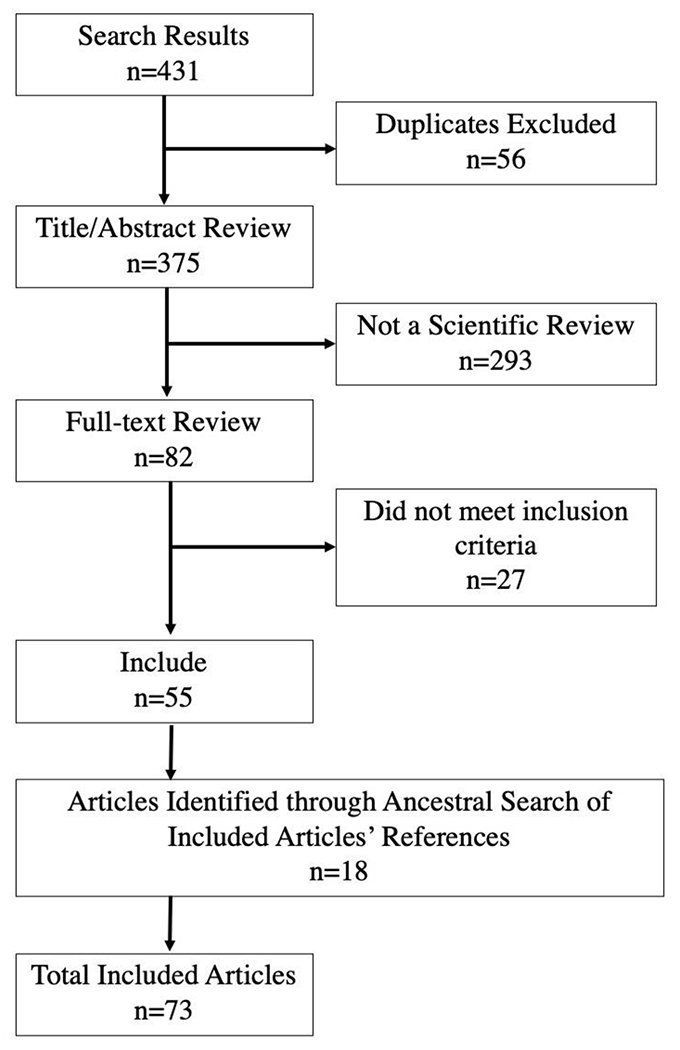

The search produced 431 results, and after de-duplication there were 375 unique citations to review. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 293 were not scientific reviews (e.g., book reviews), leaving 82 papers for full-text review of which 29 did not meet inclusion criteria. Fifty-three reviews met inclusion criteria, and 18 additional reviews were recovered from those papers’ reference lists and met inclusion criteria, producing a total of 73 review studies (Figure 1). One review included outcomes for both interpersonal and self-directed violence,(12) so that study was included within both of the two major categories of violence. In total there were 32 reviews related to self-directed violence(12–43) and 42 reviews related to interpersonal violence(12, 44–84).

Figure 1.

Search and Screening Process

In terms of the type of disparities research, the majority of reviews focused on summarizing first generation research (Tables 1 and 2). For self-directed violence, 69% were first generation, 53% were second generation, and 6% were third generation. Interpersonal violence reviews followed a similar cascade, with 67% first generation, 43% second generation, and 7% third generation. Within the interpersonal violence reviews, 6 reviews (14%) could not be categorized within the generations of disparities research framework because their foci were either summaries of methodologies (rather than prevalence, risk factors/correlates, or interventions) or theoretical synthesis of reviews.(53, 65, 71, 75, 82, 83)

Table 1.

Reviews of self-directed violence among sexual and gender minority populations, 1990-2022

| Lead Author | Year Published | Years Searched | # of Articles Included | Outcome | Focus Population | Disparities Research Generation | Countries Included in Review | Brief Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams | 2019 | 1997-2017 | 108 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 1 | Canada, U.S. | Average across studies: lifetime SI 47% (18-95%); lifetime SA 27% (9-52%) |

| Batejan | 2015 | 2005-2012 | 15 | NSSI | Sexual Minority | 1 | England, U.S. | Average lifetime NSSI across studies: 40% (9-75%) |

| Coulter | 2019 | 2000-2019 | 9 | SI/SA | SGM | 3 | England, Netherlands, New Zealand, U.S. | Most (5/9) interventions used 1-group pre/post design; findings showed efficacy but rigor of methodology was weak |

| Di Giacomo | 2018 | 1986-2017 | 22 | SA | Sexual Minority | 1 | Canada, China, Iceland, Ireland, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Taiwan, U.S. | Weighted odds of SA: transgender OR=5.87, 95% CI=3.51-9.82; gay/lesbian OR=3.71, 95% CI=3.15-4.37; bisexual OR=3.69, 95% CI=2.96-4.61 |

| Dunlop | 2020 | 2005-2019 | 24 | NSSI | Bisexual | 1,2 | Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom, U.S. | Odds (outliers removed) for bisexuals of past-year NSSI OR=5.52, 95%CI=4.34-7.03; lifetime NSSI OR=3.85, 95%CI=3.00-4.94; Risk factors: perceived heterosexism, restricted eating, substance use, being bullied, physical assault, depression, anxiety |

| Gorse | 2020 | 2009-2019 | NS | SI/SA | SGM | 2 | U.S. | Examples of risk factors: stress from coming out, peer victimization, depression, low self-esteem, hopelessness, partner violence |

| Gosling | 2021 | 2017-2021 | 28 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 2 | Australia, New Zealand, Pakistan, U.S. | Examples of risk factors: victimization, discrimination, perceived stigma, internalized trans-negativity, lack of access to care, substance use, lack of social support |

| Hatchel | 2021 | 1990-2017 | 44 | SI/SA | SGM | 2 | Netherlands, New Zealand, U.S. | Examples of risk factors: stigma, discrimination, victimization, depression, substance use, hopelessness |

| Hottes | 2016 | 1994-2014 | 30 | SA | Sexual Minority | 1 | Australia, Austria, France, Canada, Netherlands, New Zealand, United Kingdom, U.S. | Pooled estimates of lifetime SA for sexual minorities: 17% (14-20%) |

| Jackman | 2016 | 2005-2015 | 26 | NSSI | SGM | 1,2 | Canada, England, Japan, United Kingdom, U.S. | Range of NSSI among sexual minority 5-47% and among gender minority 17-42%; risk factors: victimization, discrimination, concealing identities, heterosexism/homophobia |

| Kaniuka | 2020 | 2015-2019 | 11 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 2 | U.S. | Discrimination, victimization, harassment |

| King | 2008 | 1966-2005 | 28 | SI/SA | Sexual Minority | 1 | Australia, Canada, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, United Kingdom, U.S. | Lifetime SA (pooled): OR=2.47, 95%=1.87-3.28 |

| Liu | 2019 | 2007-2019 | 51 | NSSI | SGM | 1,2 | NS | Average across studies: for LGB, lifetime NSSI 30% (24-36%) and past-year NSSI 25% (19-33%); for transgender, lifetime NSSI for transgender 47% (39-54%) and past-year NSSI 47% (35-58%); risk factors: aggression/hostility, depression, anxiety, stigma, discrimination, victimization |

| Luo | 2017 | 2000-2017 | 51 | SI | MSM | 1 | Burkina Faso, Canada, China, Estonia, Gambia, Laos, Nepal, Netherlands, Switzerland, Togo, Uganda, United Kingdom, U.S. | Lifetime SI (pooled): 35% (28-42%) |

| Luong | 2018 | 2000-2017 | 14 | SI/SA | MSM | 1,2 | NS | Range of SI 10-71% and SA 4-44%; risk factors: substance use, peer victimization, physical and sexual abuse |

| Mann | 2019 | 2000-2017 | 7 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 1 | United Kingdom | Range of lifetime SI/SA 18-96% |

| Marshal | 2011 | 1995-2009 | 24 | SI/SA | Sexual Minority | 1 | NS | Average across studies lifetime SI/SA 28% (15-49%) |

| Marshall | 2016 | 1966-2015 | 31 | SI/SA/NSSI | Gender Minority | 1 | Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom, U.S. | Range of NSSI 5-66%; SI 45-81%, SA 5-41% |

| Matarazzo | 2014 | 1991-2012 | 117 | SI/SA | SGM | 1,2 | NS | Range of lifetime SI 21-91%; lifetime SA 5-42%; risk factors: victimization, lack of social support, trauma, mental health disorders, substance use |

| McNeil | 2017 | 2003-2016 | 30 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 1,2 | Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Japan, Germany, Italy, Norway, United Kingdom, U.S. | Range of SI 37-83%; lifetime SA 10-44%; risk factors: history of incarceration, low SES, abuse, substance use, discrimination, peer victimization |

| Miranda-Mendizabal | 2017 | 1995-2015 | 14 | SA | Sexual Minority | 1 | New Zealand, Norway, United Kingdom, U.S. | SA for LGB (pooled): OR=2.26, 95%CI=1.60-3.20 |

| Pellicane | 2022 | 2000-2021 | 85 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 2 | NS | Risk factors: distal stressors (e.g., providers lack competence or knowledge in gender-affirming care; insurance denial of gender-affirming care), expectations of rejection, internalized transphobia, and concealment |

| Phillip | 2022 | 2000-2020 | 30 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 1,2 | NS | Risk factors: thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomness, discrimination, family rejection |

| Pompili | 2014 | 1987-2012 | 19 | SI/SA | Bisexual | 1,2 | NS | Bisexuals had greater SI/SA than heterosexuals in in 13/15 studies; risk factors: victimization, family rejection, discrimination |

| Rogers | 2020 | 2015-2020 | 97 | SI/SA | SGM | 1,2 | Australia, Canada, China, Iceland, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, South Korea, United Kingdom, U.S. | For sexual minorities, range of past-year SI 31-46%; past-year SA 10-30%; for gender minorities past-year SA 15-36%; risk factors: peer victimization, family rejection, depression, substance use |

| Russon | 2021 | 2000-2020 | 3 | SI/SA | SGM | 3 | U.S. | Identified 3 SGM-tailored interventions with efficacy data |

| Salway | 2019a | 1995-2016 | 46 | SI/SA | Bisexual | 1 | NS | Lifetime SI (pooled): OR=4.31, 95%CI=3.23-5.74 Past-year SI (pooled): OR=3.96, 95%CI=3.17-4.95 Lifetime SA (pooled): OR=4.44, 95%CI=3.52-5.60 Past-year SA (pooled): OR=4.81, 95%CI=3.68-6.29 |

| Salway | 2019b | 1985-2013 | 39 | SA | Sexual Minority | 1 | Australia, Austria, Canada, Demark, France, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, U.S. | Lifetime SA RR=3.38, 95%CI=2.65, 4.32 |

| Surace | 2021 | 2007-2018 | 10 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 1 | Australia, Japan, United Kingdom, U.S. | Average across studies: NSSI 28% (15-47%); SI 28% (15-46%); SA 15% (8-26%) |

| Vigny-Pau | 2021 | 1990-2020 | 52 | SI/SA/NSSI | Gender Minority | 2 | Argentina, Australia, Canada, China, Japan, Thailand, Sweden, United Kingdom, U.S. | Risk factors: discrimination, victimization, transphobic experiences, exposure to gender identity conversion efforts, peer victimization, family rejection, depression, housing instability, substance use, internalized transphobia |

| Williams | 2021 | 2002-2020 | 40 | SI/SA | SGM | 2 | China, United Kingdom, U.S. | Risk factors: victimization, low self-esteem, bullying, depression, substance use, anxiety, parental rejection |

| Wolford-Clevenger | 2018 | 1991-2017 | 45 | SI/SA | Gender Minority | 2 | Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, U.S. | Risk factors: substance use, harassment, discrimination, internalized transphobia, family rejection, depression, PTSD |

Note: SI=suicidal ideation; SA=suicide attempt; NSSI=non-suicidal self-injury; SGM=sexual and gender minority; MSM=men who have sex with men; NS=not specified

Table 2.

Reviews of interpersonal violence among sexual and gender minority populations, 1990-2022

| Lead Author | Year Published | Years Searched | # of Articles Included | Outcome | Focus Population | Disparities Research Generation | Countries Included in Review | Brief Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alessi | 2021 | 2000-2020 | 26 | Violence | SGM | 1 | U.S. | Only 8 quantitative studies; Prevalence of sexual violence ranged 23-66% |

|

|

||||||||

| Badenes-Ribera | 2015 | 1990-2013 | 8 | IPV | Lesbians | 1 | U.S. | Average across studies: lifetime IPV 48% (44-52%); current IPV 15% (5-30%) |

|

|

||||||||

| Badenes-Ribera | 2016 | 1990-2013 | 14 | IPV | Lesbians | 2 | U.S. | Risk factors: alcohol use, low self-esteem, fusion levels, family history of violence |

|

|

||||||||

| Badenes-Ribera | 2019 | 2005-2015 | 8 | IPV | Sexual Minority | 2 | Canada, China, U.S. | Risk factor: internalized homophobia |

|

|

||||||||

| Bermea | 2019 | 2000-2017 | 36 | IPV | Bisexual Women | 1,2 | NS | Narrative summary of findings indicated consistent increased prevalence of IPV for bisexual women. Risk factor: internalized homophobia, substance use, risky sexual behavior, mental illness, discrimination |

|

|

||||||||

| Blondeel | 2018 | 2000-2016 | 76 | Violence | SGM | 1 | Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cote d’Iviore, Croatia, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Netherlands, Rwanda, Singapore, Spain, United Kingdom, U.S. | Range physical violence 6-25%; range sexual violence 6-11% |

|

|

||||||||

| Buller | 2014 | 2000-2013 | 19 | IPV | MSM | 1 | Canada, China, South Africa, U.S. | Pooled prevalence of any violence (physical, sexual, emotional) 48% (32-82%) |

|

|

||||||||

| Burke | 1999 | 1978-1994 | 19 | IPV | Lesbian & Gay | 1,2 | U.S. | Narrative summary that “prevalence rates of same-sex partner abuse are high and its correlates [are similar to heterosexuals]” |

|

|

||||||||

| Callan | 2021 | 1931-2019 | 28 | IPV | Gay & Bisexual Men | 1,2 | Australia, Canada, China, Namibia, United Kingdom, U.S. | Range sexual violence 4-73% Risk factor: internalized homophobia, substance use, risky sexual behavior, mental illness, discrimination |

|

|

||||||||

| Collier | 2013 | 1995-2012 | 39 | Peer Violence | SGM | 0 | Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Israel, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, United Kingdom, U.S. | Did not summarize prevalence or risk factors; “peer victimization is correlated with a variety of negative psychosocial and health outcomes” |

|

|

||||||||

| Coulter | 2019 | 2000-2019 | 9 | Violence | SGM | 3 | England, Netherlands, New Zealand, U.S. | Most (5/9) interventions used 1-group pre/post design; findings showed efficacy but rigor of methodology was weak; only one intervention focused on victimization |

|

|

||||||||

| Dame | 2020 | 2009-2019 | 10 | Sexual Violence | MSM | 2 | Mongolia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, U.S. | Risk factors: age, belonging to a minoritized group, prejudice, history of sexual abuse or violence |

|

|

||||||||

| Decker | 2018 | 2015-2018 | 35 | IPV | SGM | 1,2 | NS | Narrative summary of prevalence; risk factors: belonging to a minoritized group, risky sexual behavior, history of abuse, housing instability, discrimination |

|

|

||||||||

| Edwards | 2015 | 1999-2014 | 96 | IPV | Sexual Minority | 1,2 | NS | IPV prevalence varied based on definition, from 1% for forced sex perpetration to 97% for any lifetime IPV; risk factors: belonging to a minoritized group, low SES, age, disability status, substance use, low self-esteem, risky sexual behavior |

|

|

||||||||

| Fedewa | 2011 | 1980-2010 | 18 | School Violence | Sexual Minority | 1 | Canada, U.S. | Bullying/peer victimization for LGB (pooled): OR=2.24, 95%CI=1.63-3.08 |

|

|

||||||||

| Feijoo | 2021 | 2008-2020 | 24 | School Violence | SGM | 1 | Spain | Bullying victimization (pooled) 51% (40-62%) |

|

|

||||||||

| Finneran | 2012 | 1990-2011 | 28 | IPV | MSM | 1,2 | U.S. | Range of lifetime IPV 30-78%; risk factors: substance use, belonging to a minoritized group |

|

|

||||||||

| Friedman | 2009 | 1980-2009 | 37 | Childhood & School Violence | Sexual Minority | 1 | Canada, U.S. | CSA OR=3.94, 95% CI=3.45-4.57; Physical abuse OR=2.34, 95% CI=2.11-2.60; Peer victimization OR=2.68, 95% CI=2.40-2.98 |

|

|

||||||||

| Jeffries | 2008 | 1996-2006 | 26 | IPV | Same-sex Partnered Men | 1,2 | Australia, Canada, Venezuela, United Kingdom, U.S. | Range emotional abuse 34-83%; range physical violence 22-44%; range sexual violence 5-57%; Risk factors: substance use, historical abuse, internalized homophobia, mental health conditions |

|

|

||||||||

| Katz-Wise | 2012 | 1992-2009 | 386 | Violence | Sexual Minority | 1 | NS | Range of victimization 5-55%; in US studies only, victimization range 9-56% |

|

|

||||||||

| Kimmes | 2019 | 1980-2016 | 24 | IPV | Sexual Minority | 2 | NS | Risk factors: internalized homophobia, substance use, history of abuse, level of outness, stigma consciousness, relationship fusion |

|

|

||||||||

| Kirk-Provencher | 2021 | through 2020 | 28 | Sexual Violence | SGM | 3 | NS | Three studies include SGM content; no study reported outcomes specifically among SGM individuals |

|

|

||||||||

| Laskey | 2019 | 2006-2016 | 106 | IPV | SGM | 0 | NS | Only 9/100 articles include SGM samples |

|

|

||||||||

| Longobardi | 2017 | 2005-2015 | 10 | IPV | Sexual Minority | 2 | Canada, China, U.S. | Risk factors: internalized homophobia, discrimination, stigma consciousness, outness |

|

|

||||||||

| Martin-Castillo | 2020 | 2009-2018 | 19 | School Violence | Gender Minority | 1,2 | Netherlands, New Zealand, U.S. | Narrative summary that peer victimization is higher among transgender than cisgender youth; risk factors: lack social support, family rejection, depression |

|

|

||||||||

| Mason | 2014 | 1997-2013 | 44 | IPV | Sexual Minority | 1,2 | NS | Range of psychological aggression GB men 12-100%, LB women 3-92%; risk factors: discrimination, relationship satisfaction, victimization |

|

|

||||||||

| McGeough | 2018 | 1980-2016 | 32 | Family Violence | Sexual Minority | 1,2 | U.S. | SM higher rates of physical abuse in 12/14 studies, sexual abuse in 13/13 studies, emotional abuse in 6/7 studies; risk factors: sexual orientation disclosure, gender non-conformity, parental substance use |

|

|

||||||||

| Mendes | 2020 | 2000-2019 | 16 | Homicide | SGM | 1 | Australia, Brazil, Italy, England/Wales, Mexico, U.S. | Reviewed characteristics of 2,921 LGBT homicides; no comparisons with non-LGBT homicides |

|

|

||||||||

| Murray | 2009 | 1995-2006 | 17 | IPV | Sexual Minority | 0 | NS | Assessed methodological strengths/weaknesses |

|

|

||||||||

| Myers | 2020 | 1998-2018 | 55 | School Violence | SGM | 1 | Canada, Belgium, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, U.S. | Overall mean effect size across studies for LGBTQ .15 (.13-.17); LGBTQ identification is moderate, consistent risk factor for school victimization |

|

|

||||||||

| Nadal | 2016 | 2010-2015 | 35 | Microaggressions | SGM | 1 | NS | Narrative summary of studies on microaggressions against LGBTQ individuals |

|

|

||||||||

| Peitzmeier | 2020 | 2000-2019 | 85 | IPV | Gender Minority | 1,2 | Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Haiti, India, Jamaica, Latin America, Mexico, Spain, South Africa, Thailand, U.S. | Any IPV (RR=1.66, 95%CI= 1.36-2.03); physical IPV (RR= 2.19, 95%CI=1.66-2.88); sexual IPV (RR=2.46, 95%CI= 1.64-3.69); risk factors: disability, housing instability, immigration status, race/ethnicity, victimization, discrimination |

|

|

||||||||

| Penone | 2018 | 2000-2018 | 100 | IPV | Same-sex Partnered People | 0 | NS | Narrative summary; prevalence estimates/ranges not specified |

|

|

||||||||

| Rolle | 2018 | 1995-2017 | 119 | IPV | Sexual Minority | 2,3 | NS | Few studies on treatments and interventions for LGB IPV comprised of counseling and therapy; heterosexism is major barrier |

|

|

||||||||

| Rothman | 2011 | 1989-2009 | 75 | Sexual Violence | Sexual Minority | 1 | U.S. | Range lifetime sexual assault for LB women 16-85%, for GB men 12-54% |

|

|

||||||||

| Schneeberger | 2014 | 1990-2013 | 73 | Childhood Violence | Sexual Minority | 1 | Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, Italy, Turkey, U.S. | Median prevalence in non-probability sampling of child sexual abuse 33%, child physical abuse 24%, child emotional abuse 49%; in probability sampling child sexual abuse 21%, child physical abuse 29%, child emotional abuse 48% |

|

|

||||||||

| Stile-Shields | 2015 | 1998-2014 | NS | IPV | Sexual Minority | 1,2 | NS | Narrative summary; prevalence of same-sex domestic violence are similar to slightly higher than opposite-sex domestic violence; internalized and externalized stressors elevate risk for sexual minorities |

|

|

||||||||

| Tobin | 2019 | 1989-2018 | 14 | Childhood Violence | Gender Minority | 1 | NS | Narrative summary: transgender and gender nonconforming identities are associated with greater risk for child abuse |

|

|

||||||||

| Toomey | 2016 | 1993-2011 | 18 | School Violence | Sexual Minority | 1 | Austria, Canada, Ireland, United Kingdom, U.S. | School-based victimization greater for sexual minorities than heterosexuals d = 0.33, 95%CI=0.23-0.42 |

|

|

||||||||

| Tran | 2022 | 2010-2020 | 18 | Microaggressions | SGM | 0 | Australia, Canada, U.S. | Narrative summary: power dynamics drive in-group microaggressions within LGBTQ+ communities |

|

|

||||||||

| Westwood | 2019 | 2010-2017 | NS | Elder Abuse | SGM | 0 | NS | Narrative summary: multiple vulnerabilities can intersect to create complex forms of abuse for older LGBT people |

|

|

||||||||

| Xu | 2015 | 1980-2013 | 65 | Childhood Violence | Sexual Minority | 1 | Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, Netherland, New Zealand, U.S. | Pooled Pprevalence child sexual abuse among LB 28% (26-31%) among GB 24% (21-27%) |

Note: IPV=Intimate partner violence; SGM=sexual and gender minority; MSM=men who have sex with men; NS=not specified; LB = lesbian/bisexual; GB=gay/bisexual

For specific topics within each of the two major types of violence, most reviews in self-directed violence combined suicidal ideation and attempt (n=18; 56%), and most reviews of interpersonal violence focused on intimate partner violence (n=20; 48%). The majority of reviews across both major types of violence included studies between 2000-2020. To better depict the breadth of current reviews, Supplemental Figures 2 and 3 illustrate reviews according to type of violence and timespans of the review by specific population.

Tables 1 and 2 also depict that, although there was a varied landscape of risk factors identified across reviews, some risk factors were applicable to all populations (e.g., substance use, depression, history of victimization). Other reviews highlighted risk factors that were more unique to SGM populations, which most centered around minority stressors (e.g., family rejection, internalized homophobia or transphobia, discrimination). The scant reviews of intervention studies were concordant in emphasizing the overall lack of research for addressing violence-related health disparities for SGM populations.

DISCUSSION

This scoping review of reviews of both interpersonal and self-directed violence, illustrates many key points about the breadth of research reviews on violence among SGM populations. First, the reviews included in this scoping review contained a total of 1,148 articles on self-directed violence and 1,895 articles on interpersonal violence, suggesting a substantial amount of research, most of which being first generation disparity research. Some of these studies are likely repeated because of reviews’ overlapping topics and time spans, but it was beyond the scope of the present review to critically analyze all of the reference lists across the 73 reviews for duplication. Still, the concordance across studies, which substantiates disparities across multiple forms of violence, from microaggressions to intimate partner violence to suicide attempt, echoes a simple question posed by Fish in a recent commentary: what now?(85) There is ample epidemiologic evidence of violence disparities – 72 reviews’ worth of hundreds of studies – so how does the field of health equity sail beyond the eddies of documenting prevalence and risk factors and into the uncharted waters of reducing disparity?

Future Directions

The reviews by Coulter et al.(12) and Russon et al.(38) are the rare examples that summarized the literature about intervention studies to reduce or prevent violence for SGM individuals; both of which found sparse results. There are three main challenges that may be scientific barriers to developing and testing violence intervention and prevention efforts for SGM populations.

First, despite minority stress being a major theoretical underpinning for the production of SGM-related health disparities,(86) specific measurement of SGM minority stress to operationalize it in research has been a relatively recent development.(87, 88) Thus, with the proliferation of more specific measurement of key intervenable risk factors, researchers can identify salient prevention points.

Second, in terms of interpersonal violence, the majority of research focuses on victims or survivors, and there is a clear paucity of research about perpetrators and primary prevention efforts.(89) Moreover, extant programs and efforts to combat intimate partner violence are too frequently limited by not understanding dynamics of or adequately serving individuals who are in same-sex relationships or in relationships that are not characterized with socially constructed binary gender identities.(90–92) For self-directed violence, the scope of inquiry has historically relied on individual-level psychopathology (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder),(93) with considerably less focus on the role of life disruption and other social environmental factors germane to distress in SGM populations (i.e., family rejection, discrimination).

Third, the roots of violence often trace to “wicked problems,” such as intergenerational poverty, historical abuse and trauma, and institutionalized racism, homophobia, sexism, and heterosexism. Thus attacking the roots of violence require broader application of monetary, social, and intellectual resources to foster the interdisciplinary capacity to meet such lofty challenges.(94, 95) However, large-scale public health interventions for violence are few in comparison to individual-level interventions.(94) By bolstering efforts in these arenas, new avenues of intervention and prevention – at both individual and structural levels – may eventually build a critical mass to answer the disparities in violence experienced by SGM communities.

Related to interventions, there remains a clear unmet need for ongoing population-base surveillance of violence for SGM individuals. For instance, the NCVS, YRBS, and NSDUH surveys only added sexual orientation and gender identity to their data collection relatively recently; thus, monitoring national prevalence of interpersonal and self-directed violence for SGM individuals – a population with known disparities in risk for violence – has scant data to estimate population-level trends over time. However, there is a more insidious consequence of historical exclusion of SOGI data from federal health surveillance. The lack of data to monitor trends of violence among SGM communities leaves prevention without a benchmark: even if the aforementioned need for interventions could be fulfilled, how would their effectiveness be evaluated without data to determine if rates of violence decrease?

In addition to violence as outcomes, epidemiologic data help to uncover novel risk and protective factors, necessary second-generation studies. One example to underscore the necessity of inclusion of SOGI information is Clark and colleagues’ analysis of the General Social Survey (GSS),(96) a robust dataset used to learn about Americans’ attitudes about firearms as well as their ownership of firearms.(97, 98) When the GSS added sexual orientation to the survey in 2008, it finally afforded an opportunity to examine potential sexual orientation-related differences in the presence of firearms in the home, which is of crucial importance for suicide prevention because access to firearms is a major moderator of suicide fatality.(99) The results of Clark et al.’s investigation revealed an interesting negative association of sexual orientation and firearms; sexual minorities were less likely to report having a firearm in the home.(96) These findings were recently replicated with BRFSS data from two U.S. states (California and Texas), which both happened to gather SOGI and firearms ownership data in 2017.(100) Together, the findings raise important future directions for violence prevention research. For example, does less access to firearms protect sexual minority populations from suicide? Would suicide prevention efforts focused on firearm safety(101) be less impactful for sexual minority populations?

As much as self-reported survey data play a role in population health surveillance, so too do administrative datasets, which largely lack SOGI data. For example, the CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program gathers emergency department data to monitor national trends in suicide attempt injuries,(102) but because SOGI data are largely missing in health care, these data cannot provide information about SGM communities. Thus, to fill gaps in intervention work to reduce violence among SGM communities, various sectors that generate administrative data – health care, social service agencies, and law enforcement – must begin to gather SOGI data alongside other demographic data they currently collect, such as age and race/ethnicity, that are typically used to monitor trends in indicators of population risk and health.

A specific form of administrative data that is paramount for monitoring violence outcomes for SGM communities is mortality surveillance. Because SOGI data are not identified in a standardized way at the time of a violent death,(103) there is currently no way to determine if homicide and suicide rates are greater for SGM communities than their non-SGM peers; despite hundreds of articles suggesting SGM individuals have disproportionate rates of major predictors of violent deaths (e.g., rates of assault, rates of suicide attempt). Limited evidence from the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) suggests that, among youth, SGM people may die by suicide at higher rates,(104) but importantly, NVDRS is missing SOGI data for nearly 80% of decedents. Can key questions about potential mortality disparities among SGM people be answered with only 20% of data? Efforts are underway to increase the likelihood for SOGI data to enter the mortality information pipeline by training death investigators to collect SOGI data, but this endeavor is still in its pilot phase.(105) Equal efforts will be needed across the aforementioned sectors (e.g., health care, social services, law enforcement) to discover ways to structurally change data systems, as well as the training and institutional culture around SOGI data collection.

Limitations

As with any scoping review, there are several limitations to note. Principally, relevant reviews may have been missed due to search criteria and parameters. For example, some highly-cited review papers, such as Haas et al.(106) and Stotzer(107), were excluded due to a priori decisions for inclusion criteria requiring articles explain their search methodology. Additionally, because publication bias is a threat to review studies, this review of reviews may inherently have publication bias encoded within it due both to the original reviews’ methodologies and the inclusion criterion of reviews published in peer-reviewed journals. The restriction of studies to being published in English limited discovering the broader international scope of studies.

Conclusion

Violence is perhaps the most infuriating and puzzling threats to public health because rather than the culprit being a virus, bacterium, environmental toxin or disaster, cells that have turned against the body, or internal organs that fail, we only have ourselves and each other to hold to account. This first review of reviews about violence research on SGM communities revealed a surprising breadth of studies, albeit mostly focused on identifying disparities. There is some progress in second-generation studies to help understand disparities and identify potential targets for intervention, but the field clearly has quite far to go for generating evidence about efficacious and effective interventions to reduce violence. Researchers are quickly capitalizing on newly available population-based datasets that include SOGI data and violence-related outcomes.(5, 7) However, we must also focus attention to developing collection of SOGI data in administrative datasets, which are necessary to foster data infrastructures that facilitate evaluation for interventions at scale.

Supplementary Material

Competing Interests and Funding:

JRB was supported by research awards from the National Institutes of Health New Innovators Award and the National Institute of Mental Health (DP2MH129967; R21MH125360).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the institutions, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peterson C, Miller GF, Barnett SBL, Florence C. Economic cost of injury: United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(48):1655–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander R, Parker K, Schwetz T. Sexual and gender minority health research at the National Institutes of Health. LGBT health. 2016;3(1):7–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herek GM. The context of anti-gay violence: Notes on cultural and psychological heterosexism. Journal of interpersonal violence. 1990;5(3):316–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller B, Humphreys L. Lifestyles and violence: Homosexual victims of assault and murder. Qualitative sociology. 1980;3(3):169–85. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender AK, Lauritsen JL. Violent victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations in the United States: Findings from the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017–2018. American journal of public health. 2021;111(2):318–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remafedi G Sexual orientation and youth suicide. Jama. 1999;282(13):1291–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramchand R, Schuler MS, Schoenbaum M, Colpe L, Ayer L. Suicidality among sexual minority adults: gender, age, and race/ethnicity differences. American journal of preventive medicine. 2022;62(2):193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johns MM, Lowry R, Haderxhanaj LT, Rasberry CN, Robin L, Scales L, et al. Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR supplements. 2020;69(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sell RL, Holliday ML. Sexual orientation data collection policy in the United States: public health malpractice. American Public Health Association; 2014. p. 967–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. American journal of public health. 2006;96(12):2113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology. 2018;18(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coulter RW, Egan JE, Kinsky S, Friedman MR, Eckstrand KL, Frankeberger J, et al. Mental health, drug, and violence interventions for sexual/gender minorities: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batejan KL, Jarvi SM, Swenson LP. Sexual orientation and non-suicidal self-injury: A meta-analytic review. Archives of Suicide Research. 2015;19(2):131–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunlop BJ, Hartley S, Oladokun O, Taylor PJ. Bisexuality and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI): A narrative synthesis of associated variables and a meta-analysis of risk. Journal of affective disorders. 2020;276:1159–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackman K, Honig J, Bockting W. Nonsuicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations: an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2016;25(23-24):3438–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu RT, Sheehan AE, Walsh RF, Sanzari CM, Cheek SM, Hernandez EM. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review. 2019;74:101783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Giacomo E, Krausz M, Colmegna F, Aspesi F, Clerici M. Estimating the risk of attempted suicide among sexual minority youths: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics. 2018;172(12):1145–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hottes TS, Bogaert L, Rhodes AE, Brennan DJ, Gesink D. Lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among sexual minority adults by study sampling strategies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of public health. 2016;106(5):e1–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salway T, Ross LE, Fehr CP, Burley J, Asadi S, Hawkins B, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of disparities in the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among bisexual populations. Archives of sexual behavior. 2019;48(1):89–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Z, Feng T, Fu H, Yang T. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. BMC psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams NJ, Vincent B. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among transgender adults in relation to education, ethnicity, and income: A systematic review. Transgender health. 2019;4(1):226–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.E Mann G, Taylor A, Wren B, de Graaf N. Review of the literature on self-injurious thoughts and behaviours in gender-diverse children and young people in the United Kingdom. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry. 2019;24(2):304–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salway T, Plöderl M, Liu J, Gustafson P. Effects of multiple forms of information bias on estimated prevalence of suicide attempts according to sexual orientation: An application of a Bayesian misclassification correction method to data from a systematic review. American journal of epidemiology. 2019;188(1):239–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surace T, Fusar-Poli L, Vozza L, Cavone V, Arcidiacono C, Mammano R, et al. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors in gender non-conforming youths: a meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021;30(8):1147–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorse M Risk and Protective Factors to LGBTQ+ Youth Suicide: A Review of the Literature. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2020:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gosling H, Pratt D, Montgomery H, Lea J. The relationship between minority stress factors and suicidal ideation and behaviours amongst transgender and gender non-conforming adults: a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatchel T, Polanin JR, Espelage DL. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ youth: meta-analyses and a systematic review. Archives of suicide research. 2021;25(1):1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaniuka AR, Bowling J. Suicidal self-directed violence among gender minority individuals: A systematic review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2021;51(2):212–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pellicane MJ, Ciesla JA. Associations between minority stress, depression, and suicidal ideation and attempts in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review. 2021:102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams AJ, Jones C, Arcelus J, Townsend E, Lazaridou A, Michail M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of victimisation and mental health prevalence among LGBTQ+ young people with experiences of self-harm and suicide. PloS one. 2021;16(1):e0245268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolford-Clevenger C, Frantell K, Smith PN, Flores LY, Stuart GL. Correlates of suicide ideation and behaviors among transgender people: A systematic review guided by ideation-to-action theory. Clinical psychology review. 2018;63:93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luong CT, Rew L, Banner M. Suicidality in young men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. Issues in mental health nursing. 2018;39(1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matarazzo BB, Barnes SM, Pease JL, Russell LM, Hanson JE, Soberay KA, et al. Suicide risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender military personnel and veterans: What does the literature tell us? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2014;44(2):200–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeil J, Ellis SJ, Eccles FJ. Suicide in trans populations: A systematic review of prevalence and correlates. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2017;4(3):341. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillip A, Pellechi A, DeSilva R, Semler K, Makani R. A plausible explanation of increased suicidal behaviors among transgender youth based on the interpersonal theory of suicide (IPTS): case series and literature review. Journal of Psychiatric Practice®. 2022;28(1):3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pompili M, Lester D, Forte A, Seretti ME, Erbuto D, Lamis DA, et al. Bisexuality and suicide: a systematic review of the current literature. The journal of sexual medicine. 2014;11(8):1903–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers ML, Taliaferro LA. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth: a Systematic Review of Recent Research. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russon J, Washington R, Machado A, Smithee L, Dellinger J. Suicide among LGBTQIA+ youth: A review of the treatment literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2021:101578. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall E, Claes L, Bouman WP, Witcomb GL, Arcelus J. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality in trans people: A systematic review of the literature. International review of psychiatry. 2016;28(1):58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vigny-Pau M, Pang N, Alkhenaini H, Abramovich A. Suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury among transgender populations: A systematic review. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2021;25(4):358–82. [Google Scholar]

- 41.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC psychiatry. 2008;8(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, et al. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of adolescent health. 2011;49(2):115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miranda-Mendizábal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco M, et al. Sexual orientation and suicidal behaviour in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. The british journal of Psychiatry. 2017;211(2):77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Badenes-Ribera L, Frias-Navarro D, Bonilla-Campos A, Pons-Salvador G, Monterde-i-Bort H. Intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbians: A meta-analysis of its prevalence. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2015;12(1):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Badenes-Ribera L, Bonilla-Campos A, Frias-Navarro D, Pons-Salvador G, Monterde-i-Bort H. Intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbians: A systematic review of its prevalence and correlates. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016;17(3):284–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Badenes-Ribera L, Sanchez-Meca J, Longobardi C. The relationship between internalized homophobia and intimate partner violence in same-sex relationships: a meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2019;20(3):331–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alessi EJ, Cheung S, Kahn S, Yu M. A scoping review of the experiences of violence and abuse among sexual and gender minority migrants across the migration trajectory. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2021;22(5):1339–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bermea AM, van Eeden-Moorefield B, Khaw L. A systematic review of research on intimate partner violence among bisexual women. Journal of Bisexuality. 2018;18(4):399–424. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blondeel K, De Vasconcelos S, García-Moreno C, Stephenson R, Temmerman M, Toskin I. Violence motivated by perception of sexual orientation and gender identity: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2018;96(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buller AM, Devries KM, Howard LM, Bacchus LJ. Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2014;11(3):e1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burke LK, Follingstad DR. Violence in lesbian and gay relationships: Theory, prevalence, and correlational factors. Clinical psychology review. 1999;19(5):487–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Callan A, Corbally M, McElvaney R. A scoping review of intimate partner violence as it relates to the experiences of gay and bisexual men. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2021;22(2):233–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collier KL, Van Beusekom G, Bos HM, Sandfort TG. Sexual orientation and gender identity/expression related peer victimization in adolescence: A systematic review of associated psychosocial and health outcomes. Journal of sex research. 2013;50(3-4):299–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dame J, Oliffe JL, Hill N, Carrier L, Evans-Amalu K. Sexual violence among men who have sex with men and two-spirit peoples: A scoping review. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2020;29(2):240–8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Decker M, Littleton HL, Edwards KM. An updated review of the literature on LGBTQ+ intimate partner violence. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2018;10(4):265–72. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edwards KM, Sylaska KM, Neal AM. Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5(2):112. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fedewa AL, Ahn S. The effects of bullying and peer victimization on sexual-minority and heterosexual youths: A quantitative meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2011;7(4):398–418. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feijóo S, Rodríguez-Fernández R. A meta-analytical review of gender-based school bullying in Spain. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(23):12687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finneran C, Stephenson R. Intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2013;14(2):168–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, Wei C, Wong CF, Saewyc EM, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. American journal of public health. 2011;101(8):1481–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeffries S, Ball M. Male same-sex intimate partner violence: a descriptive review and call for further research. eLaw Journal: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law. 2008;15(1):134–79. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of sex research. 2012;49(2-3):142–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kimmes JG, Mallory AB, Spencer C, Beck AR, Cafferky B, Stith SM. A meta-analysis of risk markers for intimate partner violence in same-sex relationships. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2019;20(3):374–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirk-Provencher KT, Spillane NS, Schick MR, Chalmers SJ, Hawes C, Orchowski LM. Sexual and gender minority inclusivity in bystander intervention programs to prevent violence on college campuses: a critical review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2021:15248380211021606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Laskey P, Bates EA, Taylor JC. A systematic literature review of intimate partner violence victimisation: An inclusive review across gender and sexuality. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2019;47:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Longobardi C, Badenes-Ribera L. Intimate partner violence in same-sex relationships and the role of sexual minority stressors: A systematic review of the past 10 years. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2017;26(8):2039–49. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martín-Castillo D, Jiménez-Barbero JA, Pastor-Bravo MdM, Sánchez-Muñoz M, Fernández-Espín ME, García-Arenas JJ. School victimization in transgender people: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;119(C). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mason TB, Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, Minifie JB, Derlega VJ. Psychological aggression in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals’ intimate relationships: A review of prevalence, correlates, and measurement issues. Aggression and violent behavior. 2014;19(3):219–34. [Google Scholar]

- 69.McGeough BL, Sterzing PR. A systematic review of family victimization experiences among sexual minority youth. The journal of primary prevention. 2018;39(5):491–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mendes WG, Duarte MJdO, Andrade CAFd, Silva CMFPd. Systematic review of the characteristics of LGBT homicides. Ciencia & saude coletiva. 2021;26:5615–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murray CE, Mobley AK. Empirical research about same-sex intimate partner violence: A methodological review. Journal of homosexuality. 2009;56(3):361–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Myers W, Turanovic JJ, Lloyd KM, Pratt TC. The victimization of LGBTQ students at school: A meta-analysis. Journal of school violence. 2020;19(4):421–32. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, Davidoff KC. Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. The journal of sex research. 2016;53(4-5):488–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peitzmeier SM, Malik M, Kattari SK, Marrow E, Stephenson R, Agénor M, et al. Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. American journal of public health. 2020;110(9):e1–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Penone G, Guarnaccia C. Intimate Partner Violence within same sex couples: a qualitative review of the literature from a psychodynamic perspective. International Journal of Psychoanalysis and Education. 2018;10(1):32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rollè L, Giardina G, Caldarera AM, Gerino E, Brustia P. When intimate partner violence meets same sex couples: A review of same sex intimate partner violence. Frontiers in psychology. 2018;9:1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rothman EF, Exner D, Baughman AL. The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United States: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2011;12(2):55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schneeberger AR, Dietl MF, Muenzenmaier KH, Huber CG, Lang UE. Stressful childhood experiences and health outcomes in sexual minority populations: a systematic review. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2014;49(9):1427–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stiles-Shields C, Carroll RA. Same-sex domestic violence: Prevalence, unique aspects, and clinical implications. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2015;41(6):636–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tobin V, Delaney KR. Child abuse victimization among transgender and gender nonconforming people: A systematic review. Perspectives in psychiatric care. 2019;55(4):576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Toomey RB, Russell ST. The role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization: A meta-analysis. Youth & society. 2016;48(2):176–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tran D, Sullivan CT, Nicholas L. Lateral violence and microaggressions in the LGBTQ+ community: a scoping review. Journal of homosexuality. 2022:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Westwood S Abuse and older lesbian, gay bisexual, and trans (LGBT) people: a commentary and research agenda. Journal of elder abuse & neglect. 2019;31(2):97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu Y, Zheng Y. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual people: a meta-analysis. Journal of child sexual abuse. 2015;24(3):315–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fish JN. Sexual minority youth are at a disadvantage: what now? The Lancet Child & adolescent health. 2020;4(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological bulletin. 2003;129(5):674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schrager SM, Goldbach JT, Mamey MR. Development of the sexual minority adolescent stress inventory. Frontiers in psychology. 2018;9:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goldbach C, Knutson D. Gender-related minority stress and gender dysphoria: Development and initial validation of the Gender Dysphoria Triggers Scale (GDTS). Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wells L, Fotheringham S. A global review of violence prevention plans: Where are the men and boys? International Social Work. 2021:0020872820963430. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cannon CE. What services exist for LGBTQ perpetrators of intimate partner violence in batterer intervention programs across North America? A qualitative study. Partner abuse. 2019;10(2):222–42. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Donovan C, Barnes R. Help-seeking among lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender victims/survivors of domestic violence and abuse: The impacts of cisgendered heteronormativity and invisibility. Journal of Sociology. 2020;56(4):554–70. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brooks D, Wirtz AL, Celentano D, Beyrer C, Hailey-Fair K, Arrington-Sanders R. Gaps in science and evidence-based interventions to respond to intimate partner violence among Black gay and bisexual men in the US: a call for an intersectional social justice approach. Sexuality & Culture. 2021;25(1):306–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nock MK, Ramirez F, Rankin O. Advancing our understanding of the who, when, and why of suicide risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(1):11–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Decker MR, Wilcox HC, Holliday CN, Webster DW. An integrated public health approach to interpersonal violence and suicide prevention and response. Public Health Reports. 2018;133(1_suppl):65S–79S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Uehara E, Flynn M, Fong R, Brekke J, Barth RP, Coulton C, et al. Grand challenges for social work. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2013;4(3):165–70. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clark KA, Blosnich JR, Coulter RWS, Bamwine P, Bossarte RM, Cochran SD. Sexual orientation differences in gun ownership and beliefs about gun safety policy, General Social Survey 2010-2016. Violence and Gender. 2020;7(1):6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smith TW, Son J. Trends in gun ownership in the United States, 1972–2014. Chicago, IL: NORC. 2015:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miller SV. What Americans think about gun control: Evidence from the General Social Survey, 1972–2016. Social Science Quarterly. 2019;100(1):272–88. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mann JJ, Michel CA. Prevention of firearm suicide in the United States: what works and what is possible. American journal of psychiatry. 2016;173(10):969–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Blosnich JR, Clark KA, Mays VM, Cochran SD. Sexual and gender minority status and firearms in the household: Findings from the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys, California and Texas. Public Health Reports. 2020;135(6):778–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Anestis MD, Bryan CJ, Capron DW, Bryan AO. Lethal means counseling, distribution of cable locks, and safe firearm storage practices among the Mississippi National Guard: A Factorial randomized controlled trial, 2018–2020. American journal of public health. 2021;111(2):309–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zwald ML, Holland KM, Annor F, Kite-Powell A, Sumner SA, Bowen D, et al. Monitoring suicide-related events using National Syndromic Surveillance Program data. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2019;11(1). [Google Scholar]

- 103.Haas AP, Lane AD, Blosnich JR, Butcher BA, Mortali MG. Collecting sexual orientation and gender identity information at death. American journal of public health. 2019;109(2):255–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ream GL. What’s unique about lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth and young adult suicides? Findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019;64(5):602–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Blosnich JR, Butcher BA, Mortali MG, Lane AD, Haas AP. Training Death Investigators to Identify Decedents’ Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: A Feasibility Study. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of homosexuality. 2010;58(1):10–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stotzer RL. Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14(3):170–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.