PURPOSE

To review the complex concerns of oncofertility created through increased cancer survivorship and the long-term effects of cancer treatment in young adults.

DESIGN

Review chemotherapy-induced ovarian dysfunction, outline how fertility may be addressed before treatment initiation, and discuss barriers to oncofertility treatment and guidelines for oncologists to provide this care to their patients.

CONCLUSION

In women of childbearing potential, ovarian dysfunction resulting from cancer therapy has profound short- and long-term implications. Ovarian dysfunction can manifest as menstrual abnormalities, hot flashes, night sweats, impaired fertility, and in the long term, increased cardiovascular risk, bone mineral density loss, and cognitive deficits. The risk of ovarian dysfunction varies between drug classes, number of received lines of therapy, chemotherapy dosage, patient age, and baseline fertility status. Currently, there is no standard clinical practice to evaluate patients for their risk of developing ovarian dysfunction with systemic therapy or means to address hormonal fluctuations during treatment. This review provides a clinical guide to obtain a baseline fertility assessment and facilitate fertility preservation discussions.

INTRODUCTION

The global cancer incidence in women of childbearing potential (WCBP; women age 15-39 years who experience menstruation, are capable of becoming pregnant, and are premenopausal) is 52.32 per 100,000 per year.1 In the United States, more than 45,000 WCBP are diagnosed with cancer each year,2 and although occurrence is substantial, treatment advancements have resulted in increased survivorship. The 5-year survival for cancer in WCBP is now >80% owing in part to novel targeted therapies.3-6 As advancements continue, focus has increased on issues of survivorship, particularly in younger patients (including the effects on fertility and future childbearing).

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To provide an overview of the challenges faced by women of childbearing potential regarding oncofertility during cancer treatment and throughout survivorship.

Knowledge Generated

Increased awareness is needed around oncofertility and related fertility-preservation resources among health care practitioners and women undergoing cancer treatment. Patient treatment plans should be collaborative, review gonadotoxic potential of various treatments, offer options for fertility counseling, and consider the individual tumor type and health status of a patient, as well as their future fertility goals.

Relevance (S. Bhatia)

This review serves as a clinical guide for all available options and resources to preserve fertility among women with cancer.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH, FASCO.

The demand for oncofertility care has been increasing.7 This care encompasses counseling for fertility preservation and providing these procedures, assessing the timing and modality of future childbearing, managing sexual dysfunction, addressing hormonal alterations, providing contraceptive counseling, and facilitating fertility-related psychosocial support. However, oncofertility-related care remains a challenge. Several systematic reviews report that oncologists lack knowledge of fertility evaluation, preservation, counseling, and referral resources.8-10 Despite patients' desire for future fertility, few are offered or receive counseling and timely fertility preservation before starting oncologic treatment (15.8%-57.0%),11-14 and utilization of fertility preservation remains low (15%-25%).11,13 Patients report concerns regarding urgency in starting cancer treatment, relationship status, vertical transmission of cancer genes, mental and physical demands, and cost as reasons against pursuing fertility preservation.14 Here, we review ovarian dysfunction observed in patients undergoing treatment in the context of oncofertility. This review is intended to aid clinical oncologists in providing comprehensive care to WCBP throughout cancer treatment and survivorship.

DESIGN: OVARIAN DYSFUNCTION RESULTING FROM SYSTEMIC TREATMENTS

Definition

Ovarian dysfunction in WCBP secondary to gonadotoxic agents has been described as premature menopause, premature ovarian failure, chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea, and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). Generally, POI is the preferred term, as ovarian follicular activity may intermittently recover, and the term premature implies a biologically arbitrary (but statistically significant) age cutoff of 40 years for cessation of menses. The term POI distinguishes an impairment that is intrinsic to the ovary (primary), as opposed to other nonovarian or endocrine dysfunctions (secondary), such as hypothalamic-pituitary disorders and adrenal disease. Clinically, it is defined by menstrual irregularity for at least 3 consecutive months and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism with sex steroid deficiency and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) >40 IU/L on two separate measurements spaced at least 1 month apart.15-17

In this review, the term ovarian dysfunction will be used to discuss the complex ovarian impairments related to systemic oncologic treatment because there is no consensus on the clinical definition that captures the spectrum of ovarian impairments resulting from treatment. Ovarian dysfunction can manifest beyond POI and encompass additional factors that affect fertility. The degree of ovarian dysfunction and its reversibility can vary by patient age, individual predisposition, and current treatment and previous treatment.18-21 This variability highlights the potential challenges in evaluating ovarian dysfunction, which is rarely assessed during drug development trials.19

Pathophysiology

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed regarding the underlying pathophysiology of chemotherapy-induced gonadotoxicity. Ovarian tissue ischemia may be caused by vasoconstriction or inhibition of angiogenesis.16 Follicular apoptosis directly results from DNA cross-linking/intercalation or inhibition of protein synthesis through DNA methylation inhibition. Follicular death may also arise from disruption to follicular cycling, as inhibition of microtubule assembly can arrest follicles in metaphase.22 Destruction of larger follicles results in a loss of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), which is responsible for the suppression of the primordial follicular pool. Primordial follicles are then activated and subsequently recruited in an effort to replace the loss of growing follicles.23 The primordial follicular pool represents a finite, nongrowing population; therefore, once it is depleted, follicles are not replaced.

Risk of Ovarian Dysfunction

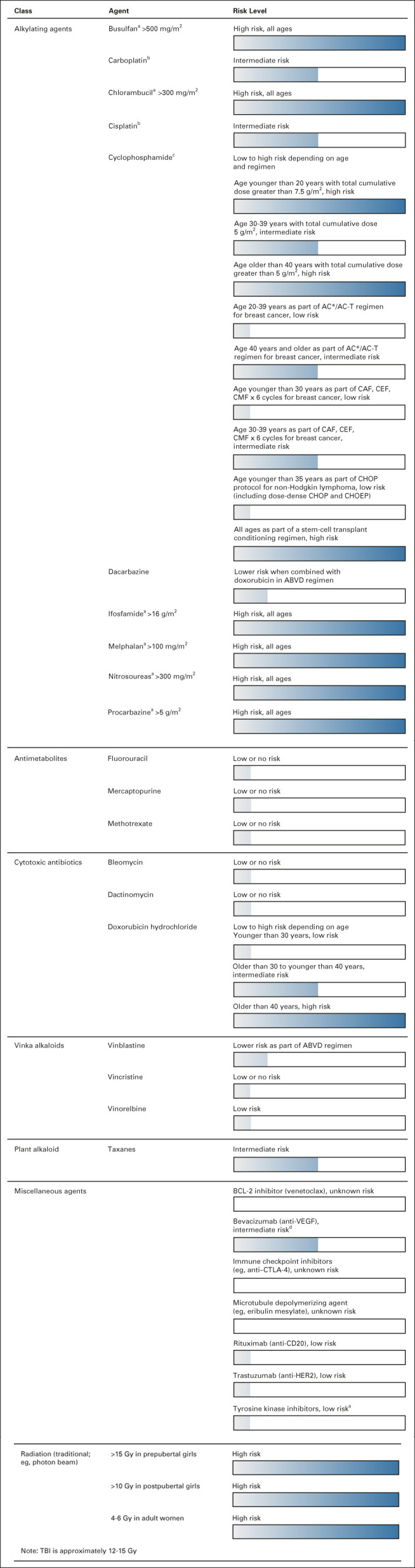

The various therapies used during treatment confer differing risks of ovarian dysfunction. An overview of the risk of amenorrhea associated with various agents throughout the literature is summarized in Figure 1. Chemotherapy administration may result in permanent amenorrhea, although recently, the results from the CANTO cohort indicate that chemotherapy-related amenorrhea (CRA) has variable persistence.38 In 1,676 women, the incidence of CRA decreased across years of post-treatment follow-up (year 1, 83.1%; year 2, 72.8%; year 4, 66.7%), and persistence was age-dependent. At 4 years after treatment, the risk for patients age 44 years and younger ranged from 23% to 73% across age subgroups, whereas CRA risk was roughly 90% across all 4 years for patients age 45 years and older. Patient-related factors such as age and baseline fertility, cumulative dose, and cycle schedule affect this risk.39 These factors can be compared at various dosages across patient populations with the cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED) calculator, specifically in the case of alkylating agents.40 A CED ≥4,000 mg/m2 is associated with a significant risk of infertility. Among traditional chemotherapies, alkylating agents pose the highest risk for deleterious effects on fertility secondary to direct primordial follicle toxicity by the induction of double-stranded DNA breaks in oocytes and germ cells.22,24 By contrast, the antimetabolites and vinca alkaloids, such as vincristine and methotrexate, are classified as low risk for primordial follicle toxicity.22,25 Platinum agents (cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin) carry a risk for oocyte damage through accumulation of ABL and TAp-63-α, which activates proapoptotic promoters.41 Specific therapies also vary in their fertility impact. For example, the risk for doxorubicin ranges from low to high, depending on treatment regimen and patient age. Patients who are older than 40 years are at highest risk, whereas those younger than 30 years are at low risk. Taxanes are associated with moderate risk for amenorrhea.26,27

FIG 1.

Risk of permanent amenorrhea associated with chemotherapeutic agents.20,21,24-37 These are general guidelines only. Additional factors such as specific age at time of treatment, baseline ovarian reserve, and specific treatment regimen will determine the individual risk for ovarian toxicity. aDose is based on cyclophosphamide equivalent dose. bDegree of gonadotoxic potential debated. cOn the basis of traditional dosing regimen. Dose-dense administration may be more gonadotoxic. dSuspected moderate risk on the basis of limited data. eLimited data. Increased malformation risk in offspring noted with female exposure to tyrosine kinase inhibitors during conception/pregnancy. ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; AC, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide; AC-T, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, taxol regimen; CAF, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and fluorouracil; CD20, cluster of differentiate 20; CEF, cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil; CHOEP, CHOP plus etoposide; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen-4; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; TBI, total-body irradiation; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

The impact of radiation on fertility can be high,42 as oocytes are extremely sensitive to radiation, and radiation effects can lower chances for a successful pregnancy.43 Direct, high doses of uterine radiation can lead to irreversible vascular and muscular damage, reducing a woman's ability to conceive and carry a child. Whole-body radiation is associated with increased risk for miscarriage, preterm labor, and low birth weight. However, below 4 Gy, radiation does not appear to affect fertility.

Surgical treatment could result in diminished ovarian reserve and premature ovarian dysfunction,44,45 and if ovaries are removed, surgically induced menopause.46 Some fertility-sparing surgeries can allow for conservation of the uterus and portions of a single ovary.46 However, treatment options are highly dependent on tumor histology and a patient's age and reproductive plans.

Evidence of gonadotoxicity from immunotherapy and targeted agents, such as small-molecule inhibitors, is limited and mixed. Immunotherapies, particularly ipilimumab, are linked to risk of hypophysitis, which can lead to secondary hypogonadism.47-49 Small-molecule inhibitors, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors50-52 and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors,27,53,54 have demonstrated varied effects on ovarian reserve in animal studies, but human data (although limited) suggest associations with decreased ovarian reserve. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have shown varied ovarian effects preclinically,50-52,55-57 whereas most clinical case series show reversible POI.58,59 In animal studies, mTOR inhibitors have demonstrated ovarian protection, as rapamycin attenuated cyclophosphamide-induced follicular apoptosis and maintained normal AMH levels.27,53,54 Rapamycin also helped prevent primordial follicle loss after cryopreservation.53 Primordial, secondary, and antral follicle counts were increased with the combination of everolimus and cisplatin.54 Unfortunately, these preclinical models did not translate to improved outcomes in humans. Clinical observational studies show association with menstrual disorders and ovarian cysts during treatment with mTOR inhibitors, specifically sirolimus.60-62 Reassuringly, normal menstrual cycles were restored a few months after treatment cessation.

Clinical Presentation

Systemic cancer treatments can lead to primary and secondary hypogonadism.47-49 For women, the resultant hypoestrogenic state often presents as menstrual irregularities (oligomenorrhea and amenorrhea) and vasomotor symptoms, including hot flashes and night sweats. Ovarian dysfunction may present initially as biochemical abnormalities such as an increase in FSH or decrease in AMH before progressing into clinical symptoms of irregular or absent menses. However, FSH can be a delayed marker of ovarian dysfunction,63 and abnormal results may appear after the ability for fertility preservation has passed. Currently, there is no standard clinical practice to monitor reproductive hormone status in patients at baseline or during systemic treatment.15 Consequently, these types of events may be under-reported if they are not associated with clinical symptoms. To appropriately assess for ovarian dysfunction, providers must maintain a high clinical suspicion and rely on patient history with regard to menstrual changes and abnormalities. Patients who note alterations in menstrual flow, regularity, cycle length and duration, or other characteristics should undergo further laboratory testing of ovarian function. In earlier stages of ovarian dysfunction, women may be able to conceive as a result of intermittent ovarian function. However, persistent hypoestrogenic state may lead to decreased sexual function and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, bone mineral density loss, and neurocognitive deficits.15 Cognitive function and memory decline have also been associated with ovarian insufficiency and can increase the risk for anxiety, depression, parkinsonism, or dementia in women experiencing hypogonadism.15

FERTILITY MANAGEMENT BEFORE INITIATION OF CHEMOTHERAPY

Fertility Preservation Counseling

Guidelines from both the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and American Society of Clinical Oncology state that health care providers should discuss infertility risks and fertility preservation options with all reproductive-aged patients before they undergo oncology treatment.64,65 Such discussions typically address associated infertility risk, desire for future childbearing, complications of delaying or altering treatment for fertility preservation, life stage (eg, age and partner status), options for fertility preservation, costs, and potential long-term risks of treatment to future offspring.64 Despite these recommendations, many women do not receive fertility counseling because oncologists often report discomfort in having these conversations with patients owing to their lack of knowledge and the perception that it may not be of benefit to the patient.66-69 In a recent systematic review, providers' knowledge of fertility preservation options was found to be as low as 22%, depending on provider type and specific methods of preservation.10 Additional barriers to counseling include a lack of training and resources, time constraints, and the need for timely referral options to reproductive specialists. Time-sensitive fertility discussions can be overwhelming in the context of a new cancer diagnosis, but they are an important component of cancer-related care.14,64,66

The reports from young adult female cancer survivors have shown that receiving fertility preservation counseling reduces long-term regret and dissatisfaction.14,66,67 Improved quality of life was observed in patients who received external fertility preservation counseling and in patients who chose to preserve fertility, compared with patients counseled by an oncology team alone.66,67 Optimally, patients should be informed about the effect of cancer treatment on their reproductive future, even when fertility preservation may not be feasible, because the counseling and an increased understanding of the treatment plan carries a demonstrated benefit.66

Ovarian Reserve Testing

Baseline ovarian reserve testing is recommended for all WCBP who are receiving treatment for a cancer diagnosis to assess future fertility and track post-treatment ovarian function. Baseline testing may help identify those at risk for diminished ovarian reserve and can provide a benchmark for assessing changes through the course of treatment. Biochemical assessments include basal FSH and estradiol, AMH, and antral follicular count (AFC) via transvaginal ultrasonography (Table 1). Of these, AMH is considered to have the greatest clinical value for determining ovarian reserve because it is a more sensitive marker than FSH for diagnosing ovarian dysfunction63 and a better correlate to primordial follicle pool and successful oocyte retrieval than AFC.63,77-79 However, AFC should be implemented in addition to AMH, as AFC can provide additional data regarding baseline ovarian reserve.80 It is important to note the limitations of these measures: FSH testing must be obtained early in the menstrual cycle (typically cycle days 2-5) in conjunction with an estradiol level to provide meaningful information.63 Additionally, some assessments (FSH and estradiol in particular) can be altered by concomitant use of oral contraceptives.63,64,76 Measurements of AMH and AFC should be interpreted carefully, as reference values of these markers change with increasing age.81 In addition, ovarian reserve markers have predictive value for response to ovarian stimulation but do not necessarily reflect the future ability to conceive or to attain a live birth.63 Prognostic scoring systems have been proposed to predict the duration and likelihood of post-treatment ovarian function recovery. For example, in a model by Su et al,82 one point each is allocated on the basis of age younger than 40 years, pretreatment AMH >0.7 ng/mL, and BMI ≥25 kg/m2. The highest score of three points indicates best prognosis, with 75% recovering ovarian function within 160 days after chemotherapy, compared with a score of one point, which has an estimated best prognosis of 75% recovery of ovarian function within 570 days of treatment cessation.82

TABLE 1.

Ovarian Reserve Assessment

Fertility Preservation Options

Guidelines from American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend consideration of oocyte or embryo cryopreservation before initiation of any treatment.64,83 Timing of cryopreservation no longer depends on the stage of the menstrual cycle, but patients and providers must consider whether cancer treatment can be delayed the requisite 2-3 weeks to facilitate a cycle of ovarian stimulation.83,84 Ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC) is an option for prepubertal female patients or patients for whom treatment delay is unacceptable.64,84 Although OTC is recommended for adult patients if treatment initiation is urgent, it is not recommended for patients age 36 years and older.20 Additional considerations of OTC include the risk of reimplanting malignant tissue.85 Ovarian cortex tissue can be screened by polymerase chain reaction testing to identify markers of malignant cells before reimplantation, but screening cannot determine the malignant potential of these cells once reimplanted. Histologic examination of cryopreserved tissue or in vitro maturation of oocytes can help avoid the risk of implanting tumor cells. Although OTC results in successful live births, it is not available at all centers and may not be suitable for all patients.86

Menstrual suppression with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) is a proposed and controversial fertility protection method that can be used concurrently with cancer treatment.87 The primary proposed mechanism of gonadoprotection by GnRHa suggests that by inducing a temporary and reversible prepubertal state, the ovaries are theoretically more resistant to chemotherapy-induced toxicity. This approach appears to have no adverse effect on disease-free survival. GnRHa is a standard option provided in several countries. Although the preponderance of literature suggests some degree of protection with GnRHa,87-89 data regarding efficacy are mixed. A meta-analysis found GnRHa to be associated with a significant reduction (P = .013) in the risk of ovarian dysfunction.88 However, the decreased risk provided by GnRHa was dependent on cancer type, with the highest risk reduction observed in patients with breast and ovarian cancers and no effect identified in studies of patients with lymphoma. GnRHa also significantly increased the number of pregnancies and the probability of becoming pregnant in patients receiving chemotherapy but had no effect on menstrual status or AMH and FSH levels after chemotherapy treatment was complete.89 An additional meta-analysis of clinical trials reported similar findings of GnRHa benefit, citing a significant decrease in ovarian dysfunction rates in patients, decreased follicular decline, increased return of regular menses, return of cyclic ovarian function, and increased pregnancy rates.87 Despite these findings, the utility and efficacy of GnRHa remains controversial, given conflicting results among publications assessing efficacy.88,89

Utilization of different fertility preservation methods varies widely. In one retrospective study, Letourneau et al67 surveyed 918 patients who underwent treatment that had the potential to affect their fertility. Of these patients, 61% (n = 560) received fertility counseling from their oncology team; 90% (n = 505) of those counseled did not continue to visit a specialist or take action to preserve fertility. Among women who did choose to preserve fertility (36 of 918 patients), half used ovarian suppression therapy, and most of the remainder (17 of 18) chose to preserve either their embryos or their eggs.67 One patient pursued bilateral oophoropexy. Of the women surveyed in this study, those who were more likely to preserve their fertility included patients without children and those younger than 35 years at the time of cancer diagnosis.

Barriers to Oncofertility Care and Solutions

Despite the need, reports from cancer survivors show that the rate of fertility counseling is relatively low among women undergoing cancer treatment, with 16%-59% of female patients reporting that they did not have a conversation related to fertility concerns with treatment. Additionally, 4%-25% reported a lack of access to fertility preservation options,13,67 and only 27% reported receiving sufficient fertility preservation information at the time of diagnosis.11

A systematic review identified six key themes that hindered the ability of females with cancer to decide about fertility preservation.90 Barriers included a lack of timely information, fear of the perceived risk of delaying treatment or exacerbating their cancer, lack of referral for fertility preservation from their oncology care team, emotional burden from cancer diagnosis, personal situation, and cost. Although barriers included both internal and external factors, oncology care teams can support patients through referral for counseling, assurance about timing of treatment, and discussion of fertility concerns when reviewing treatment plans. Improvements in patient awareness are needed, and providing information regarding oncofertility and fertility preservation via pamphlets or online decision aids can facilitate patient decision making.7,91 Additionally, patients can be offered consults or referrals to discuss fertility preservation treatment options with a reproductive endocrinology and infertility physician or advanced practice provider who specializes in oncofertility. No outside referral is required before consultation with a fertility specialist, and many fertility clinics have expedited pathways to accommodate immediate referral in this patient population. General gynecologists can also discuss the basics of fertility preservation with patients newly diagnosed with cancer; however, treatment depends on the specialized field of reproductive endocrinology and infertility. Fertility navigators may be instituted within cancer treatment centers to help patients navigate fertility preservation counseling before the initiation of treatment.

Continuing medical education for the health care team regarding fertility preservation options, available resources, referral systems, and shared decision-making conversations will ensure that patients receive the most up-to-date information in the rapidly developing field of oncofertility.8,91 Improved communication between care providers would benefit the patient, particularly when assessing the time constraints related to treatment initiation.

MANAGEMENT DURING SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

Management of Ovarian Dysfunction During Systemic Treatment

Patients should be assessed to identify concerns and symptoms related to ovarian dysfunction during treatment. For vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes that are secondary to estrogen deficiency, behavioral and lifestyle changes to reduce temperature (eg, layered clothing) should be suggested as a first step.92 Pharmacologic interventions include nonhormonal options for those at risk of exacerbation or recurrence of cancer with hormonal therapy (eg, breast cancer). Second-line treatments after patient education and behavioral modification are venlafaxine, gabapentin, or clonidine, which are frequently used as nonhormonal interventions if lifestyle modifications fail. Fluoxetine and paroxetine should not be used with tamoxifen, as these and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are potent inhibitors of CYP2D6 and can reduce efficacy of some treatments by impairing drug metabolism in certain patients. Oxybutynin showed preliminary efficacy in reducing vasomotor symptoms in a recent clinical trial.93 For non–hormone-sensitive tumors, hormone replacement can provide substantial symptomatic relief. Hormone-replacement therapy options include oral contraceptive pills, estrogen pills or patches with oral progesterone, progesterone implants, or intrauterine devices for uterine protection.94 The method of choice depends on patient history, preference, and risk factors. The decision to start hormonal replacement during systemic treatment should be discussed with both the oncologist and the gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist managing the patient's care. There is no standard of care regarding the testing of hormone levels (FSH or AMH) in patients during treatment; however, if a patient presents with symptoms consistent with ovarian dysfunction, these tests could be considered. Specifically, AMH testing may be useful for assessing ovarian reserve and confirming ovarian dysfunction in patients already on treatment, as it shows little susceptibility to alteration with hormone replacement therapy.73-75,95 Although AMH is not considered a reliable indicator of ovarian function in patients actively using GnRHa,75 it can be informative as early as 3 months after treatment cessation.75

Ovarian/Gonadal Protection During Systemic Treatment

Although GnRHa is most commonly used for gonadoprotection, medroxyprogesterone and oral contraceptives may be used for menstrual suppression.83 GnRHa treatment should begin before initiation of chemotherapy,83,96 is administered monthly or every 12 weeks via intramuscular injection (Table 2),97 and is typically limited to duration of chemotherapy. If a patient has thrombocytopenia, GnRHa can be administered subcutaneously. GnRHa induces a hypoestrogenic state within 2 weeks of initiation. Vaginal bleeding is expected approximately 2 weeks after the first injection, followed by amenorrhea. The most common adverse effects are vasomotor symptoms and bone density loss with extended therapy.

TABLE 2.

Dosing of Menstrual Suppression Therapies97

SURVEILLANCE OF SURVIVORS/POSTCHEMOTHERAPY

Guidelines for Management

After completion of gonadotoxic cancer treatment, an inquiry regarding signs of hypoestrogenism, including menstrual irregularities (amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea), vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, and dyspareunia is warranted. Assessment of ovarian function should be considered by testing FSH and estradiol or AMH regularly for at least 12-18 months after completion of chemotherapy.98 Serial assessment of AMH and FSH after treatment is important, as altered levels have been observed for up to 2 years after treatment cessation.99 Although AMH levels may not return to pretreatment baseline, they are considered a useful predictor of ovarian reserve 2 years after treatment. Referral to a reproductive endocrinologist, medical endocrinologist, or gynecologist is recommended for consideration of sex steroid–replacement therapy if patients exhibit signs of ovarian dysfunction, as extended periods of hypoestrogenism are associated with increased risk of dementia, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease.

Pregnancy is generally not recommended within 2 years after completion of therapy, when risk of relapse is highest.100 Across cancer types, the risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and infants who are small for their gestational age are lowest between 2 and 5 years after treatment. These risks increase in pregnancies conceived ≥5 years after treatment cessation. Additionally, initiating pregnancy too soon after treatment may impose adverse outcomes secondary to post-therapy implications such as poor wound healing, inflammation, insufficient weight gain, immunosuppression, and cardiovascular effects. Complications associated with longer intervals may be attributed to poor cancer prognosis and fertility challenges related to treatment or other individual predispositions. The decision to initiate pregnancy after treatment is complex, and special consideration should be given to the types of prior treatments on pregnancy, delivery, and obstetric complications, as well as congenital abnormalities, hereditary conditions, the need for additional treatments, risk for recurrence (particularly in hormone-driven tumors), and patient age.20,100 Patients should consult with the oncology care team, fertility specialists, and/or maternal fetal medicine specialists to evaluate the risks to personal and fetal health.

Role of Oncologists in Post-Treatment Surveillance

Oncologists are uniquely positioned as first-line providers to assess ovarian dysfunction. However, adverse effects of chemotherapy are known to be under-reported during clinical trials and post-treatment oncologic follow-up,101-103 as the FDA does not require investigation or reporting of adverse events related to ovarian dysfunction for approval of treatments.19,104 In early phases, ovarian dysfunction may be missed because clinical manifestations (eg, menstrual irregularities) are not easily observable to the clinician and patients may not report them. The incidence may also be underappreciated, given the under-representation of women across oncology clinical trials.105 Assessment of patient-reported symptoms allows for optimization of long-term outcomes, including a survival benefit and quality of life for the patient.102

DISCUSSION

In conclusion, the detrimental effect of cancer treatment regimens on reproductive health has been well established.21,47-49,57,60,61 Chemotherapy-induced ovarian dysfunction has significant health consequences, and potential risks should be recognized in this patient population. Short-term effects include vasomotor symptoms and sexual dysfunction, and longer-term effects include low bone mass, osteoporosis, and increased cardiovascular risks. Patients should be counseled regarding the potential negative reproductive consequences.7,21,24,47-49,64,83,91

An assessment of baseline ovarian function and counseling regarding fertility preservation are recommended before initiation of systemic therapy for all reproductive-aged patients who desire future fertility.63,98 Counseling about fertility preservation options has been shown to reduce long-term regret and dissatisfaction among cancer survivors and may be associated with improvements in physical and psychologic quality of life.63,65-67 Physicians should be proactive in discussing ovarian dysfunction risk and related health sequelae when reviewing treatment plans with patients. Oncologists should also be vigilant in assessing patients for symptoms and signs of ovarian dysfunction during and after treatment. By offering fertility counseling and proactive surveillance for ovarian dysfunction, oncologists can provide the best opportunity for patients to improve quality of life in survivorship, including future reproductive success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Writing and editorial assistance was provided under the direction of the authors by Dorothy Dobbins, PhD, and Claire Levine, MS, ELS, MedThink SciCom.

SUPPORT

Supported by SpringWorks Therapeutics (Stamford, CT). SpringWorks had the opportunity to review and provide input on the manuscript, but the final decision on content was exclusively retained by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Laurie J. McKenzie

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: Laurie J. McKenzie

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Cancer Treatment-Related Ovarian Dysfunction in Women of Childbearing Potential: Management and Fertility Preservation Options

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.You L, Lv Z, Li C, et al. : Worldwide cancer statistics of adolescents and young adults in 2019: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. ESMO Open 6:100255, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols HB, Baggett CD, Engel SM, et al. : The Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Horizon study: An AYA cancer survivorship cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 30:857-866, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen PB, Savas H, Evens AM, et al. : Pembrolizumab followed by AVD in untreated early unfavorable and advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 137:1318-1326, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. : PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 372:311-319, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, et al. : Five-year outcomes from the randomized, phase III trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 39:723-733, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. : Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 381:1535-1546, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anazodo A, Laws P, Logan S, et al. : How can we improve oncofertility care for patients? A systematic scoping review of current international practice and models of care. Hum Reprod Update 25:159-179, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krouwel EM, Birkhoff EML, Nicolai MPJ, et al. : An educational need regarding treatment-related infertility and fertility preservation: A national survey among members of the Dutch Society for Medical Oncologists. J Cancer Educ 38:106-114, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorfman CS, Stalls JM, Mills C, et al. : Addressing barriers to fertility preservation for cancer patients: The role of oncofertility patient navigation. J Oncol Navig Surviv 12:332-348, 2021 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor JF, Ott MA: Fertility preservation after a cancer diagnosis: A systematic review of adolescents', parents', and providers' perspectives, experiences, and preferences. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 29:585-598, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Mersereau JE, Su HI, et al. : Young female cancer survivors' use of fertility care after completing cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 24:3191-3199, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schover LR, Rybicki LA, Martin BA, et al. : Having children after cancer. A pilot survey of survivors' attitudes and experiences. Cancer 86:697-709, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stal J, Yi SY, Cohen-Cutler S, et al. : Fertility preservation discussions between young adult rectal cancer survivors and their providers: Sex-specific prevalence and correlates. Oncologist 27:579-586, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshpande NA, Braun IM, Meyer FL: Impact of fertility preservation counseling and treatment on psychological outcomes among women with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 121:3938-3947, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vos M, Devroey P, Fauser BC: Primary ovarian insufficiency. Lancet 376:911-921, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mauri D, Gazouli I, Zarkavelis G, et al. : Chemotherapy associated ovarian failure. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 11:572388, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson LM: Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med 360:606-614, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark RA, Mostoufi-Moab S, Yasui Y, et al. : Predicting acute ovarian failure in female survivors of childhood cancer: A cohort study in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) and the St Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE). Lancet Oncol 21:436-445, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui W, Stern C, Hickey M, et al. : Preventing ovarian failure associated with chemotherapy. Med J Aust 209:412-416, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambertini M, Peccatori FA, Demeestere I, et al. : Fertility preservation and post-treatment pregnancies in post-pubertal cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol 31:1664-1678, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 24:2917-2931, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bedoschi G, Navarro PA, Oktay K: Chemotherapy-induced damage to ovary: Mechanisms and clinical impact. Future Oncol 12:2333-2344, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roness H, Gavish Z, Cohen Y, et al. : Ovarian follicle burnout: A universal phenomenon? Cell Cycle 12:3245-3246, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S, Kim SW, Han SJ, et al. : Molecular mechanism and prevention strategy of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced ovarian damage. Int J Mol Sci 22:7484, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCollam S, Shipman C, Bubalo J, et al. : Preventing chemotherapy-induced infertility in female patients. J Hematol Oncol Pharm 9:192-198, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gast KC, Cathcart-Rake EJ, Norman AD, et al. : Regimen-specific rates of chemotherapy-related amenorrhea in breast cancer survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr 3:pzk801, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou L, Xie Y, Li S, et al. : Rapamycin prevents cyclophosphamide-induced over-activation of primordial follicle pool through PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in vivo. J Ovarian Res 10:56, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson MH, Mertens AC, Spencer JB, et al. : Menses resumption after cancer treatment-induced amenorrhea occurs early or not at all. Fertil Sterility 105:765-772.e4, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avastin [Package Insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cozmuta R, Merkel PA, Fraenkel L: Variability in experts' opinions regarding risks and treatment choices in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. J Clin Rheumatol 19:426-431, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine J: Gonadotoxicity of cancer therapies in pediatric and reproductive-age females, in Gracia C, Woodruff TK. (eds): Oncofertility Medical Practice: Clinical Issues and Implementation. New York, NY, Springer Science, 2012, pp 3-14 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munoz M, Santaballa A, Segui MA, et al. : SEOM Clinical Guideline of fertility preservation and reproduction in cancer patients (2016). Clin Transl Oncol 18:1229-1236, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poorvu PD, Frazier AL, Feraco AM, et al. : Cancer treatment-related infertility: A critical review of the evidence. JNCI Cancer Spectr 3:pkz008, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rambhatla A, Strug MR, De Paredes JG, et al. : Fertility considerations in targeted biologic therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A review. J Assist Reprod Genet 38:1897-1908, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva C, Ribeiro Rama AC, Reis Soares S, et al. : Adverse reproductive health outcomes in a cohort of young women with breast cancer exposed to systemic treatments. J Ovarian Res 12:102, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livestrong Foundation : Fertility Risks for Women. https://www.livestrong.org/content/fertility-risk-chart-women [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oktay K, Oktem O, Reh A, et al. : Measuring the impact of chemotherapy on fertility in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:4044-4046, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabirian R, Javas K, Franzoi MA, et al. : Factors associated with chemotherapy (CT)-related amenorrhea (CRA) and its relationship with quality of life (QOL) in premenopausal women with early breast cancer (BC): Results from the prospective CANTO cohort study. Ann Oncol 33:S713-S742, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arecco L, Ruelle T, Martelli V, et al. : How to protect ovarian function before and during chemotherapy? J Clin Med 10:4192, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, et al. : The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 61:53-67, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonfloni S, Di Tella L, Caldarola S, et al. : Inhibition of the c-Abl-TAp63 pathway protects mouse oocytes from chemotherapy-induced death. Nat Med 15:1179-1185, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao W, Liang JX, Yan Q: Exposure to radiation therapy is associated with female reproductive health among childhood cancer survivors: A meta-analysis study. J Assist Reprod Genet 32:1179-1186, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teh WT, Stern C, Chander S, et al. : The impact of uterine radiation on subsequent fertility and pregnancy outcomes. BioMed Res Int 2014:482968, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asgari Z, Tehranian A, Rouholamin S, et al. : Comparing surgical outcome and ovarian reserve after laparoscopic hysterectomy between two methods of with and without prophylactic bilateral salpingectomy: A randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Res Ther 14:543-548, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gelbaya TA, Nardo LG, Fitzgerald CT, et al. : Ovarian response to gonadotropins after laparoscopic salpingectomy or the division of fallopian tubes for hydrosalpinges. Fertil Sterility 85:1464-1468, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crafton SM, Cohn DE, Llamocca EN, et al. : Fertility-sparing surgery and survival among reproductive-age women with epithelial ovarian cancer in 2 cancer registries. Cancer 126:1217-1224, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozdemir BC: Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hypogonadism and infertility: A neglected issue in immuno-oncology. J Immunother Cancer 9:e002220, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bai X, Lin X, Zheng K, et al. : Mapping endocrine toxicity spectrum of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A disproportionality analysis using the WHO adverse drug reaction database, VigiBase. Endocrine 69:670-681, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barroso-Sousa R, Barry WT, Garrido-Castro AC, et al. : Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 4:173-182, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong YH, Kim SJ, Kim SK, et al. : Impact of imatinib or dasatinib coadministration on in vitro preantral follicle development and oocyte acquisition in cyclophosphamide-treated mice. Clin Exp Reprod Med 47:269-276, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim SY, Cordeiro MH, Serna VA, et al. : Rescue of platinum-damaged oocytes from programmed cell death through inactivation of the p53 family signaling network. Cell Death Differ 20:987-997, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morgan S, Lopes F, Gourley C, et al. : Cisplatin and doxorubicin induce distinct mechanisms of ovarian follicle loss; imatinib provides selective protection only against cisplatin. PLoS One 8:e70117, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Celik S, Ozkavukcu S, Celik-Ozenci C: Altered expression of activator proteins that control follicle reserve after ovarian tissue cryopreservation/transplantation and primordial follicle loss prevention by rapamycin. J Assist Reprod Genet 37:2119-2136, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka Y, Kimura F, Zheng L, et al. : Protective effect of a mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitor on an in vivo model of cisplatin-induced ovarian gonadotoxicity. Exp Anim 67:493-500, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bildik G, Acılan C, Sahin GN, et al. : C-Abl is not actıvated in DNA damage-induced and Tap63-mediated oocyte apoptosıs in human ovary. Cell Death Dis 9:943, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kerr JB, Hutt KJ, Cook M, et al. : Cisplatin-induced primordial follicle oocyte killing and loss of fertility are not prevented by imatinib. Nat Med 18:1170-1172, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salem W, Ho JR, Woo I, et al. : Long-term imatinib diminishes ovarian reserve and impacts embryo quality. J Assist Reprod Genet 37:1459-1466, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Sanctis R, Lorenzi E, Agostinetto E, et al. : Primary ovarian insufficiency associated with pazopanib therapy in a breast angiosarcoma patient: A CARE-compliant case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e18089, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zamah AM, Mauro MJ, Druker BJ, et al. : Will imatinib compromise reproductive capacity? Oncologist 16:1422-1427, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boobes Y, Bernieh B, Saadi H, et al. : Gonadal dysfunction and infertility in kidney transplant patients receiving sirolimus. Int Urol Nephrol 42:493-498, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Triana P, López-Gutierrez JC: Menstrual disorders associated with sirolimus treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68:e28867, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braun M, Young J, Reiner CS, et al. : Low-dose oral sirolimus and the risk of menstrual-cycle disturbances and ovarian cysts: Analysis of the randomized controlled SUISSE ADPKD trial. PLoS One 7:e45868, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tal R, Seifer DB: Ovarian reserve testing: A user's guide. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217:129-140, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine : Fertility preservation and reproduction in cancer patients. Fertil Steril 83:1622-1628, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. : Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 36:1994-2001, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benedict C, Thom B, Kelvin JF: Young adult female cancer survivors' decision regret about fertility preservation. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 4:213-218, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, et al. : Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer 118:1710-1717, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, King L, et al. : Impact of physicians' personal discomfort and patient prognosis on discussion of fertility preservation with young cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 77:338-343, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goossens J, Delbaere I, Van Lancker A, et al. : Cancer patients' and professional caregivers' needs, preferences and factors associated with receiving and providing fertility-related information: A mixed-methods systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 51:300-319, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Letourneau JM, Cakmak H, Quinn M, et al. : Long-term hormonal contraceptive use is associated with a reversible suppression of antral follicle count and a break from hormonal contraception may improve oocyte yield. J Assist Reprod Genet 34:1137-1144, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sinha N, Letourneau JM, Wald K, et al. : Antral follicle count recovery in women with menses after treatment with and without gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist use during chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Assist Reprod Genet 35:1861-1868, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee opinion no. 605: Primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol 124:193-197, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kruszynska A, Slowinska-Srzednicka J: Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a good predictor of time of menopause. Menopausal Rev 16:47-50, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liberty G, Ben-Chetrit A, Margalioth EJ, et al. : Does estrogen directly modulate anti-mullerian hormone secretion in women? Fertil Sterility 94:2253-2256, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yin WW, Huang CC, Chen YR, et al. : The effect of medication on serum anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) levels in women of reproductive age: A meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord 22:158, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christin-Maitre S, Laveille C, Collette J, et al. : Pharmacodynamics of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) in postmenopausal women during pulsed estrogen therapy: Evidence that FSH release and synthesis are controlled by distinct pathways. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:5405-5413, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson RA, Rosendahl M, Kelsey TW, et al. : Pretreatment anti-Müllerian hormone predicts for loss of ovarian function after chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 49:3404-3411, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dillon KE, Sammel MD, Prewitt M, et al. : Pretreatment antimüllerian hormone levels determine rate of posttherapy ovarian reserve recovery: Acute changes in ovarian reserve during and after chemotherapy. Fertil Sterility 99:477-483.e1, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grisendi V, Mastellari E, La Marca A: Ovarian reserve markers to identify poor responders in the context of poseidon classification. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10:281, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Penzias A, Azziz R, Bendikson K, et al. : Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: A committee opinion. Fertil Sterility 114:1151-1157, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gunasheela D: Age-specific distribution of serum anti-mullerian hormone and antral follicle count in Indian infertile women. J Hum Reprod Sci 15:97, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Su HCI, Haunschild C, Chung K, et al. : Prechemotherapy antimullerian hormone, age, and body size predict timing of return of ovarian function in young breast cancer patients. Cancer 120:3691-3698, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L, et al. : Adolescent and young adult oncology, version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 16:66-97, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mikhael S, Punjala-Patel A, Gavrilova-Jordan L: Hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis disorders impacting female fertility. Biomedicines 7:5, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rosendahl M, Greve T, Andersen CY: The safety of transplanting cryopreserved ovarian tissue in cancer patients: A review of the literature. J Assist Reprod Genet 30:11-24, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Donnez J, Dolmans MM: Fertility preservation in women. N Engl J Med 377:1657-1665, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blumenfeld Z: Fertility preservation using GnRH agonists: Rationale, possible mechanisms, and explanation of controversy. Clin Med Insights: Reprod Health 13:1179558119870163, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Del Mastro L, Ceppi M, Poggio F, et al. : Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian failure in cancer women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cancer Treat Rev 40:675-683, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Behringer K, Thielen I, Mueller H, et al. : Fertility and gonadal function in female survivors after treatment of early unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) within the German Hodgkin Study Group HD14 trial. Ann Oncol 23:1818-1825, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jones G, Hughes J, Mahmoodi N, et al. : What factors hinder the decision-making process for women with cancer and contemplating fertility preservation treatment? Hum Reprod Update 23:433-457, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van den Berg M, Baysal O, Nelen WLDM, et al. : Professionals' barriers in female oncofertility care and strategies for improvement. Hum Reprod 34:1074-1082, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Boekhout AH, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH: Symptoms and treatment in cancer therapy-induced early menopause. Oncologist 11:641-654, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leon-Ferre RA, Novotny PJ, Wolfe EG, et al. : Oxybutynin vs placebo for hot flashes in women with or without breast cancer: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial (ACCRU SC-1603). JNCI Cancer Spectr 4:pkz088, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee opinion no. 698: Hormone therapy in primary ovarian insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol 129:e134-e141, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kallio S, Puurunen J, Ruokonen A, et al. : Antimullerian hormone levels decrease in women using combined contraception independently of administration route. Fertil Sterility 99:1305-1310, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martin-Johnston MK, Okoji OY, Armstrong A: Therapeutic amenorrhea in patients at risk for thrombocytopenia. Obstetrical Gynecol Surv 63:395-402, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Adolescent Health Care : Options for prevention and management of menstrual bleeding in adolescent patients undergoing cancer treatment: ACOG committee opinion, number 817. Obstet Gynecol 137:e7-e15, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van Dorp W, Mulder RL, Kremer LC, et al. : Recommendations for premature ovarian insufficiency surveillance for female survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: A report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group in collaboration with the PanCareSurFup Consortium. J Clin Oncol 34:3440-3450, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Anderson RA, Mansi J, Coleman RE, et al. : The utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in the diagnosis and prediction of loss of ovarian function following chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 87:58-64, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hartnett KP, Mertens AC, Kramer MR, et al. : Pregnancy after cancer: Does timing of conception affect infant health? Cancer 124:4401-4407, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, et al. : How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol 22:3485-3490, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lizán L, Pérez-Carbonell L, Comellas M: Additional value of patient-reported symptom monitoring in cancer care: A systematic review of the literature. Cancers (Basel) 13:4615, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pavlović Mavić M, Šeparović R, Tečić Vuger A, et al. : Difference in estimation of side effects of chemotherapy between physicians and patients with early-stage breast cancer: The use of patient reported outcomes (PROs) in the evaluation of toxicity in everyday clinical practice. Cancers (Basel) 13:5922, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cui W, Phillips KA, Francis PA, et al. : Understanding the barriers to, and facilitators of, ovarian toxicity assessment in breast cancer clinical trials. Breast 64:56-62, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee E, Wen P: Gender and sex disparity in cancer trials. ESMO Open 5:e000773, 2020. (suppl 4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]