Abstract

Fallopian tube epithelial cells (FTEC) are thought to be the cell of origin of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. FTEC organoids can be used as research models for the disease. Nevertheless, culturing organoids requires a medium supplemented with several expensive growth factors. We proposed that a combined conditioned medium based on the composition of the fallopian tubes, including epithelial, stromal, and endothelial cells could enhance FTEC organoid formation. We derived two primary culture cell lines from the fimbria portion of the fallopian tubes. The organoids were split into conventional or combined medium groups based on what medium they were grown in and compared. The number and size of the organoids were evaluated. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were used to evaluate gene and protein expression (PAX8, FOXJ1, beta-catenin, and stemness genes). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure Wnt3a and RSPO1 in both mediums. DKK1 and LiCl were added to the mediums to evaluate their influence on beta-catenin signaling. The growth factor in the combined medium was evaluated by the growth factor array. We found that the conventional medium was better for organoids regarding proliferation (number and size). In addition, WNT3A and RSPO1 concentrations were too low in the combined medium and needed to be added making the cost equivalent to the conventional medium. However, the organoid formation rate was 100% in both groups. Furthermore, the combined medium group had higher PAX8 and stemness gene expression (OLFM4, SSEA4, LGR5, B3GALT5) when compared with the conventional medium group. Wnt signaling was evident in the organoids grown in the conventional medium but not in the combined medium. PLGF, IGFBP6, VEGF, bFGF, and SCFR were found to be enriched in the combined medium. In conclusion, the combined medium could successfully culture organoids and enhance PAX8 and stemness gene expression. However, the conventional medium was a better medium for organoid proliferation. The expense of both mediums was comparable. The benefit of using a combined medium requires further exploration.

Keywords: organoid, Wnt/beta-catenin, fallopian tube epithelial cells, endothelial cells, stromal cells, medium

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer is responsible for a fifth of all cancer deaths among women1. The most lethal type is high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC)1. More than 220,000 new cases of ovarian cancer are diagnosed worldwide every year2. The 5-year survival rate is only 30%–40% often due to patients discovering the disease in its late stage1. Therefore, identifying how to detect the disease at an early stage and effective interventions for its carcinogenesis is critical.

Fallopian tube epithelial cells (FTEC) are regarded as the cell origin of HGSOC3. Cancer progression of these cells is characterized by a p53 signature caused by the expansion of TP53-mutated progenitor cells which is defined as the first stage of carcinogenesis4,5. This p53 signature can progress to serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and HGSOC6. Previous studies have indicated FTEC may follow the classical cancer evolution model from precancerous to cancerous lesions by clonal expansion and accumulation of driver mutations3.

The current research model for ovarian cancer includes patient-derived xenografts and tumor cell lines7. Nevertheless, those models owned disadvantages: construction of a cell line is time-consuming, loss of genetic characteristics after long-term culture, and animal care facilities require an investment7–9. Therefore, the organoid is developed for cancer research10. 3D organoid models can provide micro-anatomies with similar elements and structures to primary tissues11. They also offer models corresponding to the in vivo status of organs and a steady system for long-term culturing11. Tumor organoids can conquer the disadvantages mentioned above of current research models7.

The conventional culture medium for organoids consists of a lot of growth factors, including Wnt3a, RSPO1, N2, B27, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)1012. We estimated the expense for 50 ml of conventional culture medium to be US$646. Therefore, organoid experiments are extremely expensive. For this reason, we aimed to develop an economic and effective medium for culturing organoids. We previously developed an organoid model using cocultured FTEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), and fallopian tube stromal cells (FTMSC)13. The combined cell cultures mimicked the fallopian tube microenvironment. We derived the conditioned medium from the typical mediums of the three cells to create adequate coculturing conditions (the estimated expense was US$80 for 50 ml).

This study aimed to compare the conventional culture medium to our condition medium in the formation and differentiation of organoids. The content of both organoid culture medias, Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, and stemness gene and protein expression of the organoids were assessed.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Concern

All experiment protocols were proved by the Research Ethical Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital (IRB 109-221-A). The experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants provided informed consent.

FTEC Derivation

We derived two primary culture FTEC lines (A01 and A03) from the fallopian tubes of 2 patients who visited our hospital between January 2021 to December 2021 and underwent a hysterectomy accompanied by a salpingectomy or adnexal removal surgery for a benign gynecologic indication. The inclusion criteria were premenopausal patients who underwent a hysterectomy accompanied by a salpingectomy or adnexal removal surgery for a benign gynecologic indication. The exclusion criteria were women experiencing uterine or ovarian benign pathologies that were not suitable for surgical exploration or refused to join this experiment.

The fimbria portion of the fallopian tubes was used. For FTEC culturing, the fimbriae were rinsed with 5 mM EDTA and cultured in 1% trypsin for 45 min (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). To separate the epithelial and stromal layers, the fallopian tubes were put in a digest medium consisting of 0.8 mg/ml of collagenase in DMEM (Gibco, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biological Ind., Kibbutz, Israel) and 5 μg/ml of insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37oC for 45 min. After digestion, the dissociated epithelial layer was cultured in prewarmed 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen). A 22-gauge needle was used to dissociate the tissue into single cells that were bypassed five times. Trypsinization was stopped by adding DMEM containing 10% FBS. The derived FTEC were cultured on wells coated with gelatin for the following experiments (2D cell culture).

FTMSCs Derivation

The protocol for FTMSC derivation was described in our previously published paper13. Briefly, the fallopian tube stroma was dissociated from the epithelium layer, washed with 5mM EDTA and then incubated in 1% trypsin for 45 min. For digestion, the stroma layer was placed in 0.8 mg/ml collagenase, DMEM-low glucose, 10% FBS, and 5 μg/ml insulin and incubated for 45 min at 37oC. A 22-gauge needle was used for dissociation of the pellet into single cells that were bypassed five times. DMEM-low glucose and 10% FBS were added to stop digestion. The FTMSCs were plated into 10 cm dishes, grown and passaged in a 1:3 ratio.

HUVEC Cultures

The HUVEC were purchased from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC, Hsinchu, Taiwan)13. Endothelial Cell Medium was used to culture the cells (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany), which was replaced every 2–3 days.

Combined Medium Collection

The combined medium consisted of the conditioned medium derived from the FTEC, FTMSC, and HUVEC. The medium for culturing FTEC consisted of DMEM with 10% FBS and 5 μg/ml of insulin. The basal medium for FTMSC consisted of DMEM-low glucose and 5% FBS. The medium for culturing HUVEC was Endothelial Cell Medium (Promocell) which was changed every 2–3 days. After the cells proliferated to 80% confluence of the area of a 15-cm dish, the culture medium was changed to a serum-free medium (20 ml) and then collected after 24 hours. The combined medium was derived from mixing the conditioned medium from the FTEC, FTMSC, and HUVEC in a ratio of 10:7:2 according to the previous studies13,14.

Conventional Medium

The conventional medium was composed of DMEM supplemented with 1000 ng/ml of Wnt3a, 200 ng/ml of RSPO1 (R & D, Minneapolis, MN, USA), 1% glutamax, 12 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid), 1% N2, 2% B27, 10 ng/ml of EGF (Invitrogen), 100 ng/ml of FGF10 (Peprotech), 100 ng/ml of noggin, 1 mM of nicotinamide, 0.5 μM of TGF-β R kinase inhibitor IV (SB431542, Sigma), and 9 μM of ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, Sigma).

Organoid Culturing

For organoid culturing, we adopted the protocol from a previous report but with slight modifications12. A total of 25,000 fresh isolated FTECs were cultured in one of six well dishes, mixed with 50 μl of 1% Matrigel (BD Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix), and overlaid with 500 μl of the specified organoid culture medium and placed in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. The medium was replaced every other day. The organoid cultures were divided into two experimental groups based on the combined and conventional mediums.

Organoid Numbers and Sizes

An organoid with a diameter of more than 100 μm was categorized as large. An organoid diameter of <100 μm was categorized as small. The number and size of the organoids from each group were counted and compared on day 21 (average of six, 40× field views).

To measure proliferation, the six largest organoids from each group were measured for diameter on days 7, 14, and 21. The mean diameter plus standard deviation was calculated and compared.

Immunohistochemistry

Organoids were embedded in an optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and stored at −80oC. The OCT-embedded organoids were sectioned at 5 μm thickness. The sections were removed from the OCT, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. The sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked with 5% FBS, and treated with primary antibodies (1:100, FOXJ1 [ciliated cell marker], 1:100, PAX8 [secretory cell marker], and 1:100, beta-catenin, all purchased from Abcam) for 1.5 h. The sections were washed with PBS and 0.1% Tween 20, then treated with secondary antibodies [Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE); Abcam] for 1 h. The sections were then mounted in antifade solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and washed with PBS plus 0.1% Tween 20. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and the slides were subjected to confocal laser-scanning microscopy (LSM5 PASCAL; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The concentrations of Wnt3a and RSPO1 in the combined and conventional mediums were evaluated and compared using human enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Wnt3a and RSPO1, Aviva Systems Biology Corp., San Diego, CA, USA).

Growth Factor Array

The combined conditioned medium was collected and passed through a 0.22-μm cell strainer to remove cell debris. The growth factors secreted from the combined medium were measured using a growth factor array kit (AAH-GF-1-8, human growth factor array C1; Raybiotech, Peachtree Corners, GA, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. A total of 41 growth factors were analyzed.

Adding DKK1 or LiCl to Inhibit or Promote Beta-Catenin Expression

A total of 25,000 FTEC were cultured in one of the 6-well plates, mixed with 50 μl matrigel and overlaid with 500 μl of combined or conventional culture medium. In the inhibition assay, the culture medium was treated with 250 ng/ml of DKK1 (inhibitor of Wnt signaling, R & D system) for 7 days. In the activation assay, 10 μM of LiCl (Wnt signaling stimulator, Sigma-Aldrich) was added for 7 days. The medium was replaced every 2 days. The number and size of the organoids were observed after 7 days.

Quantification of Stemness Marker Expression of FTEC Organoids after DKK1 or LiCl Treatment

The total RNA of the organoids after treatment for 7 days [control (combined or conventional medium only), DKK1, or LiCl] were extracted using an RNEasy® kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stemness genes were evaluated using real-time PCR. The genes and their primer sequences were as followed15: OLFM4 (olfactomedin 4, forward: 5’-A C T G T C G A A T T G A C A T C A T G G-3’ and reverse: 5’-T T C T G A G C T T C C A C C A A A A C T C-3’ ), LGR6 (leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein–coupled receptor 6, forward: 5’-C C T C C T C A G C T T C A C C T T G-3’ and reverse: 5’-C T T C C A G G C C T T T C T C T G T G-3’), b3GalT5 [SSEA3 (stage-specific embryonic antigen-3), forward: 5’-GCAGATCTATGGCTTTCCCGAAGATG-3’ and reverse: 5’-GTCTCGAGTCAGACAGGCGGACAAT-3’], LGR5 (forward: 5’-ACCCGCCAGTCTCCTACATC-3’ and reverse: 5’-GCATCTAGGCGCAGGGATTG-3’), ALDH1 (aldehyde dehydrogenase isoform 1, forward: 5’-CTGCTGGCGACAATGGAGT-3’ and reverse: 5’-GTCAGCCCAACCTGCACAG-3’), 3SSEA4 synthase (forward: 5’-TGGACGGGCACAACTTCATC-3’ and reverse: 5’-GGGCAGGTTCTTGGCACTCT-3’), Notch signaling gene HES1 (Hes family bHLH transcription factor 1, forward: 5’-T T C T G A G C T C C A C C A A A A C T C-3’ and reverse: 5’-A G G C G C A A T C C A A T A T G A A C-3’ ); PAX8 (forward: 5’-CAACAGCACCCTGGACGAC-3’ and reverse: 5’-AGGGTGAGTGAGGATCTGCC-3’); FOXJ1 (forward: 5’-G G A G G G G A C G T A A A T C C C T A -3’ and reverse: 5’-G G T C C C A G T A G T T C C A G C A A -3’); beta-catenin (forward: 5’-CACAAGCAGAGTGCTGAAGGTG-3’ and reverse: 5’-GATTCCTGAGAGTCCAAAGACAG-3’). The SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, United States) was used for complementary DNA synthesis. PCR with AmpliTaq Gold Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) was used for amplification. The FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master kit (Rox) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, United States) and ABI Step One Plus system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) were used for performing real-time PCR. The GAPDH gene (forward: 5’-TCT CCT CTG ACT TCA ACA GCG AC-3’ and reverse: 5’-CCC TGT TGC TGT AGC CAA ATT C-3’) was used as an internal control. The expression levels of the genes were quantified by comparison to the internal control and calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method16. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

The Student t test was used for the analysis of continuous variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Tukey analysis was used for categorical variables. All statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 24 (IBM, New York, USA). Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise indicated. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Wnt3a and RSPO1 Combined Medium Concentration

Table 1 shows the concentration of Wnt3a and RSPO1 in each medium measured by ELISA. Wnt3a and RSPO1 concentrations were very low in the combined medium. Therefore, to maintain the Wnt signaling during organoid formation, the same concentration of Wnt3a and RSPO1 that was in the conventional medium (Wnt3a: 1000 ng/ml, RSPO1: 200 ng/ml) was added to the combined medium.

Table 1.

The Concentration of Wnt3a and RSPO1 in the Combined and Conventional Mediums Assessed by ELISA.

| Combined | Conventional | |

|---|---|---|

| Wnt3a (ng/ml) | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 0 |

| RSPO1 (ng/ml) | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 0 |

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The Expense of Both Culture Mediums

The final expense for 50 ml of conventional culture medium was US$646 (US$1 = 29.28 New Taiwan Dollars). The original expense for the combined medium was US$80 for 50 ml. Nevertheless, due to the necessary Wnt3a (1000 ng/ml) and RSPO1(200 ng/ml) addition, the final expense for 50 ml came to US$534.

The Efficiency of Organoid Formation

We successfully derived two organoid lines from three patient specimens using the conventional medium. The derivation efficiency was 66%. After adding Wnt3a and RSPO1 to the combined medium, a 66% organoid formation success rate was also achieved.

The Proliferation of the Organoids

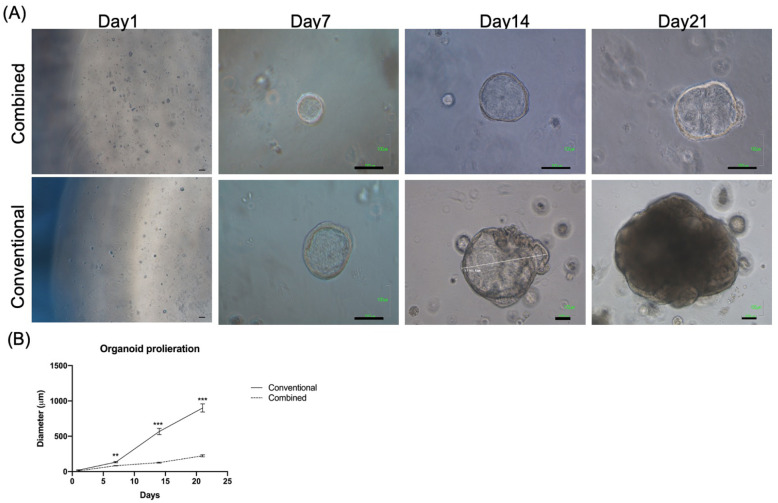

Organoid morphology and proliferation were monitored from day 1 to 21. The morphology of the organoids from both groups from day 1 to 21 is illustrated in Fig. 1A. The proliferation rate of the organoids cultured in the conventional medium was faster than that of the combined medium (P < 0.01 on day 7, P < 0.001 on days 14 and 21) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Gross pictures and the proliferation rates of organoids cultured with different mediums from day 1 to 21. (A) Upper panel: combined medium, lower panel: conventional medium. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) The proliferation rate of the organoids. The mean diameter (μm) of the largest organoids (n = 6 in each group) was calculated at each time point. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 when compared with the combined medium group.

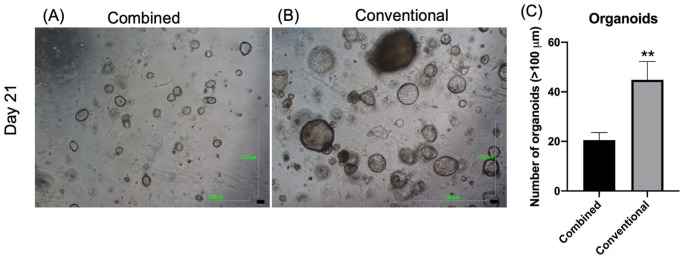

After 21 days of culture, the number of organoids measuring >100 μm was recorded and compared between the two groups. The morphology of the organoids in the combined and conventional medium on day 21 is illustrated in Fig. 2A, B, respectively. The number of >100 μm organoids was significantly higher in the conventional group than in the combined group (P < 0.01, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

The number of large organoids (>100 μm) cultured in the different mediums after 21 days. Organoids were cultured in the combined medium (A) and conventional medium (B) after 21 days. Scale bar = 1000 μm. (C) The number of large organoids (>100 μm) in the combined and conventional medium groups (average count for six 40× fields). **P < 0.01.

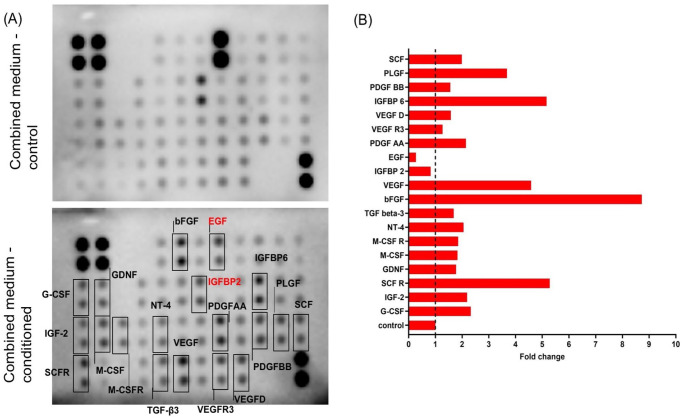

The Growth Factor in the Combined Medium

To further investigate the composition of the combined medium, the growth factor array was used to characterize. PLGF, IGFBP6, VEGF, bFGF, and SCFR were the five most expressed growth factors (Fig. 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Identification of growth factors from the combined medium. (A) The proteins in the combined medium were analyzed using a growth factor array. The boxes indicated higher protein expression including PLGF, IGFBP6, VEGF, bFGF, and SCFR, and lower protein expression including EGF and IGFBP2. (B) The quantification results of fold change in each protein were expressed as a histogram. PLGF: placental growth factor; IGFBP6: insulin growth factor binding protein-6; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; bFGF: beta-fibroblast growth factor; SCFR: stem cell factor receptor; EGF: epidermal growth factor; IGFBP2: insulin growth factor binding protein-2; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IGF-2: insulin growth factor-2; GDNF: glial-derived neurotrophic factor; M-CSF: macrophage colony-stimulating factor; M-CSFR: macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor; NT-4: Neurotrophin-4; TGF-β3: transforming growth factor-β3; EGF: epidermal growth factor; PDGF-AA: platelet-derived growth factor-AA; VEGFD: vascular endothelial growth factor D; VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; SCF: stem cell factor; PDGF-BB: platelet-derived growth factor-BB.

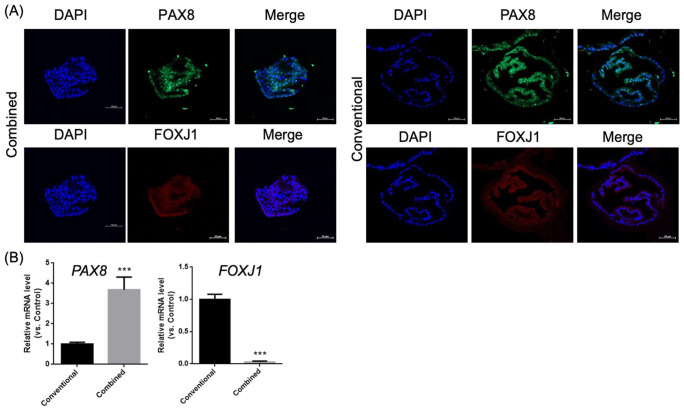

PAX8 and FOXJ1 Expression

To characterize FTEC-related protein and gene expression, we measured PAX8 and FOXJ1 expression (markers for secretory and ciliated cells, respectively)13. IHC revealed PAX8 and FOXJ1 expression in the organoids cultured in the combined (Fig. 4A) and conventional medium (Fig. 4B). Fig. 3C contains the qPCR results of PAX8 and FOXJ1 expression for both groups. Increasing PAX8 and decreasing FOXJ1 expression were noted in the combined group when compared with the conventional group (p < .001, Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of organoids cultured in different mediums. PAX8 and FOXJ1 staining in the organoids cultured in the combined (A) and conventional medium (B). Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) qRT-PCR showing PAX8 and FOXJ1 expression in the organoids cultured in both mediums. qRT-PCR: Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. ***P < 0.001.

The combined medium promoted secretory cell differentiation more than the conventional medium.

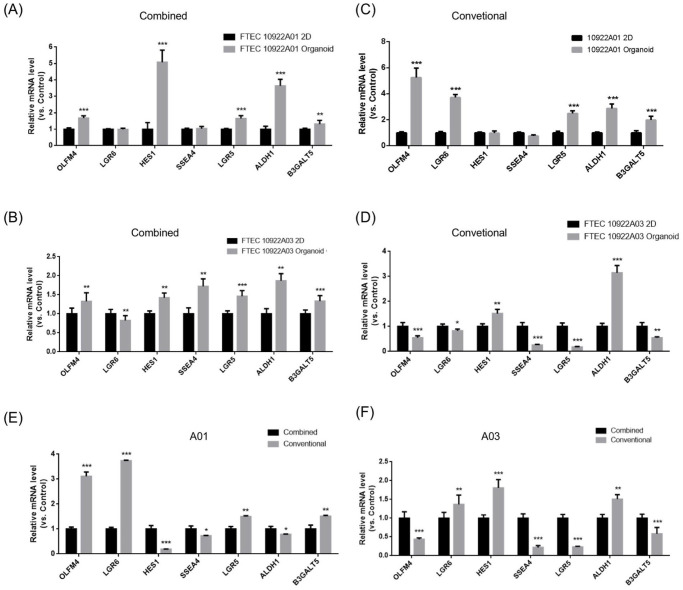

Stemness Genes Expression

Stemness markers (OFLM4, LGR5, and LGR6), a Notch signaling gene (HES1), and stem cell markers (β3GALT5, SSEA4, and ALDH1) were quantified in the different culture conditions12,15. The gene expression of the two cell lines (A01 and A03) grown in 2D cultures or as organoids are compared in Fig. 5A–D. In the combined medium, the A01 and A03 organoids had greater expression of OLFM1, HES1, LGR5, ALDH1, and β3GALT5 than the 2D cultured cells (Fig. 5A, B). A03 organoids expressed more SSEA4 and less LGR6 than the 2D cultured cells (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Quantitative mRNA expression of stemness genes in the 2D cultured cells and the organoids in two FTEC lines. Stemness markers (OFLM4, AXIN2, and LGR6), a Notch signaling gene (HES1), and stem cell markers (SSEA3, SSEA4, ALDH1, and LGR5) were quantified. (A) FTECA01 (combined medium, 2D vs organoids). (B) FTECA03 (combined medium, 2D vs organoids). (C) FTECA01 (conventional medium, 2D vs organoids). (D) FTECA03 (conventional medium, 2D vs organoids). (E) Combined vs conventional medium cultured FTECA01 organoids. (F) Combined vs conventional medium cultured FTECA03 organoids. FTEC: fallopian tube epithelium cell. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

In the conventional medium, ALDH1 was the commonly greater expression than in 2D culture. The expression of other genes was different between the two groups. In A01 organoid, OLFM4, LGR5, LGR6, and β3GALT5 (SSEA3) also increased expression (Fig. 5C). HES1 and ALDH1 expression in the A03 organoids were more significant than in the 2D cultured cells (Fig. 5D). However, A03 organoid expression of all other genes was decreased when compared with the expression of the 2D cultured cells (Fig. 5C).

Compared with conventional medium, combined medium cultured A03 organoids expressed more OLFM4, SSEA4, LGR5, and β3GALT5 (SSEA3) (Fig. 5E, F). Stemness marker expressions were enhanced in organoids when compared with 2D cultured cells in the combined medium. Furthermore, combined medium-cultured organoids expressed more stemness genes than conventional medium-cultured organoids.

We found organoid culture under a combined medium expressing more stemness markers (OLFM4, HES1, LGR5, ALDH1, and β3GALT5) than 2D culture. Conversely, in organoid culture under a conventional medium, only two stemness markers (HES1 and ALDH1) were expressed more than in 2D culture.

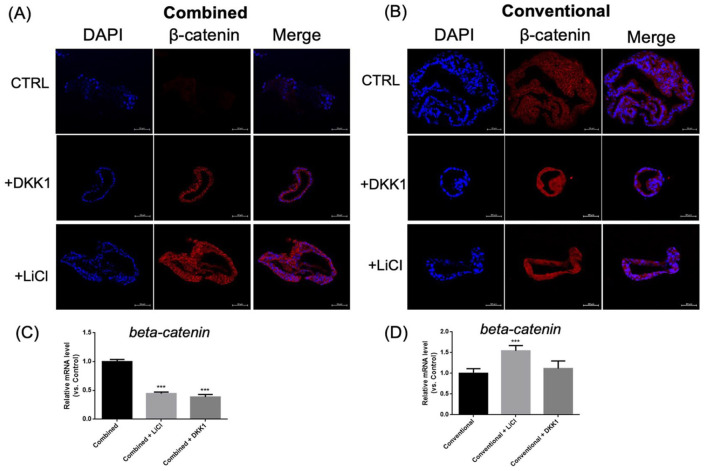

The Influence of Stemness Genes Expression After Wnt Signaling Manipulating

Beta-catenin expression was noted for both culture mediums (Fig. 5). After LiCl (stimulator) and DKK1 (inhibitor) addition, beta-catenin was expressed in both the cell nucleus and cytoplasm of the organoids in the conventional group, but not in the combined group (Fig. 5B). qPCR showed beta-catenin expression was inhibited after adding DKK1 or LiCl to the combined medium. However, for the conventional medium, the expression of beta-catenin could be manipulated by adding DKK1 or LiCl (Fig. 5C, D).

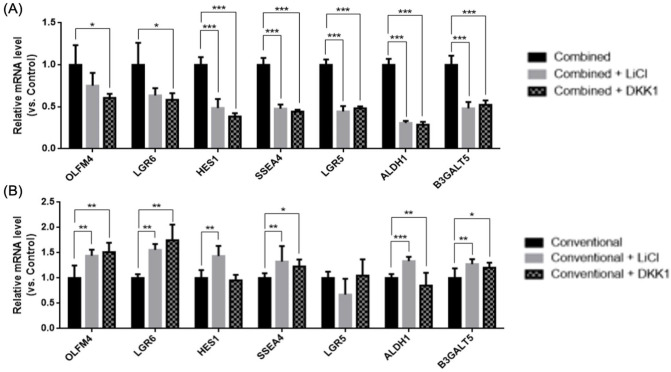

Stemness marker expression was quantified using qPCR. In the combined medium, LiCl or DKK1 had no effect and the expression of all the stemness genes was decreased (Fig. 6A). On the contrary, in the conventional medium LiCl promoted the expression of the stemness genes and DKK1 inhibited it (Fig. 6B). The Wnt signaling pathway was evident in the organoids cultured in the conventional medium which could be manipulated by adding a stimulator or inhibitor.

Figure 6.

The IHC and quantitative mRNA results for beta-catenin expression in organoids cultured in the different mediums and with or without DKK1 or LiCl. Beta-catenin IHC of organoids cultured in combined (A) or conventional medium (B) with or without DKK1 or LiCl. Scale bar = 50 μm. β-catenin entered the nucleus after adding DKK1 or LiCl for organoids grown in the conventional medium, but not in the combined medium. (C-D) qPCR revealed beta-catenin gene expression with or without DKK1 or LiCl in the organoids cultured in the combined (C) or conventional medium (D) for 7 days. IHC: immunohistochemistry; qPCR: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction. ***P < 0.01 when compared with the combined medium cultured organoids.

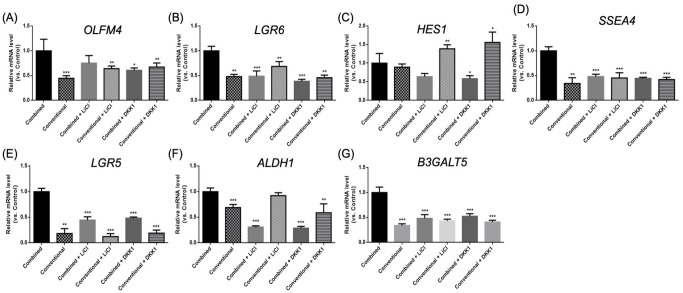

The expression of the stemness genes of the organoids in each group was compared (Fig. 7). The expression of the stemness genes of the organoids cultured in different culture mediums with or without LiCl or DKK1 in each gene was compared (Fig. 8). Expression was increased for organoids in the combined medium; however, not for organoids in the conventional medium.

Figure 7.

Quantitative mRNA expression of stemness genes in organoids cultured in different culture mediums with or without LiCl or DKK1. Stemness markers (OLFM4, LGR5, LGR6), a Notch signaling gene (HES1), and stem cell markers (B3GALT5, SSEA4, ALDH1) were evaluated by qPCR in the organoids cultured in the combined (A) and conventional mediums (B). qPCR: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 when compared with the control.

Figure 8.

Quantitative mRNA expression of stemness genes in organoids cultured in combined and conventional culture medium with or without LiCl or DKK1 after 7 days of treatment. (A) OLFM4, (B) LGR6, (C) HES1, (D) SSEA4, (E) LGR5, (F) ALDH1, and (G) B3GALT5. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 when compared with the combined medium cultured organoids.

Stemness gene expression of the organoids cultured in the combined medium was increased when compared with that of 2D cultured cells.

Discussion

In this study, conventional medium cultured organoids exhibited faster proliferation rates resulting in larger sizes when compared with those cultured in the combined medium. The cost of both mediums was comparable. Organoids in the combined medium showed more secretory cell differentiation (increased PAX8 expression) than organoids in the conventional medium. Organoid culture with a combined medium expressed more stemness markers (OLFM4, HES1, LGR5, ALDH1, and β3GALT5) than the 2D culture and conventional medium. Conventional medium-cultured organoids exhibited Wnt signaling, which was influenced by adding a Wnt signaling stimulator or inhibitor.

HGSOC has been hypothesized to originate from FTEC5,17. Knowing the cause of HGSOC carcinogenesis is important for the prevention and therapy of ovarian cancer. The Organoid is an ideal research model for oncogenesis investigation and drug screening7. Therefore, developing an ideal cost-effectiveness culturing method would be extremely beneficial. The current study explored the possibility of lowering the cost of FTEC culturing medium. The effectiveness was not comparable between the two mediums; more studies exploring culture medium cost reduction are needed to improve results.

We found organoid culture under a combined medium expressing more stemness markers (OLFM4, HES1, LGR5, ALDH1, and β3GALT5) than the 2D culture. These genes covered fallopian tube stemness genes, Notch signaling pathway, and stem cell markers. Organoid culture is nearing the in vivo status, and the gene expression is also mimicking in vivo7,18. Conversely, conventional medium-cultured organoids only increased the expression of two genes (HES1 and ALDH1) more than the 2D culture. The combined medium promoted more organoid stemness than the conventional and 2D cultures.

We found PLGF, IGFBP6, VEGF, bFGF, and SCFR were the prominent five growth factors in the combined medium. PLGF/c-MYC/miR-19a axis was reported to be associated with gallbladder cancer stemness and metastasis19. The crosstalk between GPR81/IGFBP6 promotes breast cancer progression20. VEGF/neuropilin signaling was associated with cancer stem cell functions21. bFGF enhances the stemness of apical papilla stem cells22. SCFR (c-Kit) is the receptor for SCF binding and activates signaling, including cell survival, proliferation, and migration23. Taken together, these enriched growth factors in the combined medium might promote stemness gene expressions of the organoids.

Kessler et al. reported the first study of FTEC forming organoids and found that Wnt3a and RSPO1 were important for organoid formation. Wnt3a and RSPO1 are critical components of the Wnt signaling pathway, where Wnt3a binds to LGR4, 5, or 6 to proceed with signaling, and RSPO1 acts as an LGR agonist12. They also found that Wnt and Notch signaling pathways were important for organoid formation. After this discovery, the long-term culture method of FTEC organoids was published24. The organoid culture medium invented by Kessler is called conventional medium which is composed of 25% of conditioned medium taken from cells that secrete WNT3A and RSPO112. Other organoid cultured mediums are composed of 600 ng/ml RSPO1 and 100 ng/ml WNT3A24, or 200 ng/ml WNT3A and 10% RSPO125. In our previous research, organoids were cultured in a medium composed of 50 ng/ml WNT3A and 50 ng/ml RSPO113. In the current study, we changed the concentration of Wnt3a and RSPO1 to 1000 ng/ml and 200 ng/ml, respectively.

Our previous study showed that the Wnt pathway could affect organoid formation by coculturing three kinds of cells (FTEC, FTMSCs, and HUVEC)13. After adding DKK1, the organoids could not be formed and the expressions of FOXJ1 and LGR5 were decreased13. The combination of the three different cells mimics the fallopian tube microenvironment. That is why we used the combined medium in the hopes of supporting organoid proliferation and differentiation. However, in this study when DKK1 was added to inhibit the Wnt signaling pathway, it did not inhibit organoid formation. This may be because the organoids were formed from FTEC in this current study, which is different from the previous study that used three kinds of cells.

Different cell densities can be used to evaluate organoid proliferation26. It was found that 2000 cells in a single well of a 96-well plate could achieve the best proliferation curve when compared with any other cell density. Bode et al.27 used propidium iodide and Hoechst dye to calculate the death rate of organoids treated with cisplatin or 5-FU. However, this method can be affected by enhanced background noise due to potential dye incorporation into the matrigel. Consequently, we used a microscopic imaging technique to measure proliferation and to calculate the size and number of organoids.

The Wnt pathway plays an important role in the stemness regulation of FTEC. A previous study showed that Wnt receptors, LGR5 and LGR6, are associated with FTEC stem cell characteristics15. RSPO1-4 respond to LGR 4, 5, and 6 and are positive regulators of Wnt signaling28. Therefore, adding Wn3a and RSPO1 upregulates Wnt signaling in organoid cultures. Another study showed that LGR5 is expressed in FTEC stem cells and LGR6 is expressed in FTE organoids stem cells12. LGR6+ cells in the organoid are represented as multipotent cell population12. Blocking LGR6 expressions causes stem cell differentiation12. In our study, LGR5 expression in the organoids was increased compared with the 2D cells in the combined medium. LGR6 expression in the organoids was decreased in the 2D cells in both mediums. The above results indicated that combined medium organoid cells stayed in FTEC stem cell status but reduced organoid stem cell characteristics.

OLFM4 is a stem and cancer cell marker of intestinal cells and FTEC12,29. OFM4 deletion in ApcMin/+ mice induces colon adenocarcinoma30. We previously found that FTEC treated with progesterone could increase OLFM4 expression15. OLFM4 loss expression after gamma-radiation-induced small intestinal organoid damage31. After interferon gamma addition, LGR5 decreased expression, and OLFM4 increased expression in organoids derived from colitis patients32. The interaction reaction was mediated by interleukin-2232. In the current study, OLFM4 expression was increased in the combined medium organoids more than that of the combined medium 2D cells. Conversely, OLFM4 expression decreased in the conventional medium organoids more than that of the combined medium 2D cells. The OLMF4 expression of organoids cultured by the conventional medium might be influenced by cytokines in the medium or organoid damage.

HES1 is a Notch signaling protein related to the stemness of FTEC12,24. We previously found that hormone treatment of FTEC could increase HES1 expression15. HES1 is also associated with other organoid formations, including the retina33, hepato-biliary-pancreatic34, and intestine35. In the current study, HES1 increased expression in both combined and conventional medium cultured organoids more than that of the 2D cultured cells.

SSEA3 and SSEA4 are key embryonic and pluripotent stem cell markers36. Both genes are also markers for cancer stem cells37. After hormone treatment, the expression of these genes is increased in FTEC15. Compared with 2D cells, SSEA3 and SSEA4 expression in the organoids were increased in the combined medium but decreased in the conventional medium. The expressions of SSEA3 and SSEA4 in organoids were higher in the combined medium than in the conventional medium. The combined medium could enhance SSEA3 and SSEA4 expression in the organoids. However, both self-renewal gene expressions did not reflect on organoid proliferation38.

ALDH1 is expressed in cancer stem cells and is related to prognosis39. ALDH1 is also a stemness marker for FTEC12. Progesterone treatment increases ALDH1 expression in FTEC15. In our study, ALDH1 expression in the organoids was increased compared with the 2D cells in the combined medium. We speculated that ALDH1 expression higher in the conventional medium than that in the combined medium might be due to the activation of the glycolytic pathway40.

Wnt signaling manipulated by DKK1 and LiCl was only evident in the organoids cultured by the conventional medium. The difference between combined and conventional mediums was a different component. The defined growth factors in the conventional medium were explored in the previous research which was correlated with Wnt and Notch signaling12. The component of the combined medium was largely unknown except Wnt3a and RSPO1. Therefore, Wnt signaling can be manipulated in the organoids cultured by the conventional medium.

This study was the first study to compare combined medium to conventional medium regarding cost-effectiveness in FTEC organoid formation. A limitation of this study was the small case number. Larger studies are required in the future to reinforce our results.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the combined medium could successfully culture organoids. The combined medium organoids also showed enhanced stemness genes expression. The conventional medium is more suitable for organoid proliferation. The benefit of using the combined medium needs further exploration.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: D.C.D. designed the experiment; D.C.D. performed the experiments; D.C.D., Y.H.C., K.C.W., and T.H. analyzed the data; D.C.D. and Y.H.C. wrote the paper and all authors gave final approval.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent: The experimental protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital (IRB 109-221-A). Informed consent was obtained from every patient.

Availability of Data and Material: All data generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC (MOST 110-2314-303-007), Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital (TCRD 110–25), and Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (TCMF-EP 111-01).

ORCID iD: Dah-Ching Ding  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5105-068X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5105-068X

References

- 1. Arora N, Talhouk A, McAlpine JN, Law MR, Hanley GE. Long-term mortality among women with epithelial ovarian cancer: a population-based study in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perrone MG, Luisi O, De Grassi A, Ferorelli S, Cormio G, Scilimati A. Translational theragnosis of ovarian cancer: where do we stand? Curr Med Chem. 2020;27(34):5675–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shih IM, Wang Y, Wang TL. The origin of ovarian cancer species and precancerous landscape. Am J Pathol. 2021;191(1):26–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu NY, Fang C, Huang HS, Wang J, Chu TY. Natural history of ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma from time effects of ovulation inhibition and progesterone clearance of p53-defective lesions. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang Y-H, Chu T-Y, Ding D-C. Spontaneous transformation of a p53 and Rb-defective human fallopian tube epithelial cell line after long passage with features of high-grade serous carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Labidi-Galy SI, Papp E, Hallberg D, Niknafs N, Adleff V, Noe M, Bhattacharya R, Novak M, Jones S, Phallen J, Hruban CA, et al. High grade serous ovarian carcinomas originate in the fallopian tube. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang YH, Wu KC, Harnod T, Ding DC. The organoid: a research model for ovarian cancer. Tzu Chi Med J. 2022;34(3):255–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thu KL, Papari-Zareei M, Stastny V, Song K, Peyton M, Martinez VD, Zhang Y-A, Castro IB, Varella-Garcia M, Liang H, Xing C, et al. A comprehensively characterized cell line panel highly representative of clinical ovarian high-grade serous carcinomas. Oncotarget. 2017;8(31):50489–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kreuzinger C, Gamperl M, Wolf A, Heinze G, Geroldinger A, Lambrechts D, Boeckx B, Smeets D, Horvat R, Aust S, Hamilton G, et al. Molecular characterization of 7 new established cell lines from high grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;362(2):218–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RG, Van Es JH, Van den Brink S, Van Houdt WJ, Pronk A, Van Gorp J, Siersema PD, Clevers H. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1762–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA. Organogenesis in a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science. 2014;345(6194):1247125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kessler M, Hoffmann K, Brinkmann V, Thieck O, Jackisch S, Toelle B, Berger H, Mollenkopf H-J, Mangler M, Sehouli J, Fotopoulou C, et al. The Notch and Wnt pathways regulate stemness and differentiation in human fallopian tube organoids. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang Y-H, Chu T-Y, Ding D-C. Human fallopian tube epithelial cells exhibit stemness features, self-renewal capacity, and Wnt-related organoid formation. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takebe T, Sekine K, Enomura M, Koike H, Kimura M, Ogaeri T, Zhang R-R, Ueno Y, Zheng Y-W, Koike N, Aoyama S, et al. Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature. 2013;499(7459):481–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang YH, Ding DC, Chu TY. Estradiol and progesterone induced differentiation and increased stemness gene expression of human fallopian tube epithelial cells. J Cancer. 2019;10(13):3028–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hong M-K, Chu T-Y, Ding D-C. The fallopian tube is the culprit and an accomplice in type II ovarian cancer: a review. Tzu Chi Med J. 2013;25(4):203–205. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang Q, Liberali P. Collective behaviours in organoids. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2021;72:81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li H, Jin Y, Hu Y, Jiang L, Liu F, Zhang Y, Hao Y, Chen S, Wu X, Liu Y. The PLGF/c-MYC/miR-19a axis promotes metastasis and stemness in gallbladder cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(5):1532–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Longhitano L, Forte S, Orlando L, Grasso S, Barbato A, Vicario N, Parenti R, Fontana P, Amorini AM, Lazzarino G, Li Volti G, et al. The crosstalk between GPR81/IGFBP6 promotes breast cancer progression by modulating lactate metabolism and oxidative stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(2):275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mercurio AM. VEGF/neuropilin signaling in cancer stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu J, Huang GT, He W, Wang P, Tong Z, Jia Q, Dong L, Niu Z, Ni L. Basic fibroblast growth factor enhances stemness of human stem cells from the apical papilla. J Endod. 2012;38(5):614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lennartsson J, Rönnstrand L. Stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit: from basic science to clinical implications. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(4):1619–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xie Y, Park ES, Xiang D, Li Z. Long-term organoid culture reveals enrichment of organoid-forming epithelial cells in the fimbrial portion of mouse fallopian tube. Stem Cell Res. 2018;32:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boretto M, Maenhoudt N, Luo X, Hennes A, Boeckx B, Bui B, Heremans R, Perneel L, Kobayashi H, Van Zundert I, Brems H, et al. Patient-derived organoids from endometrial disease capture clinical heterogeneity and are amenable to drug screening. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(8):1041–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xie B-Y, Wu A-W. Organoid culture of isolated cells from patient-derived tissues with colorectal cancer. Chin Med J. 2016;129(20):2469–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bode KJ, Mueller S, Schweinlin M, Metzger M, Brunner T. A fast and simple fluorometric method to detect cell death in 3D intestinal organoids. Biotechniques. 2019;67(1):23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carmon KS, Gong X, Lin Q, Thomas A, Liu Q. R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(28):11452–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Flier LG, Haegebarth A, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. OLFM4 is a robust marker for stem cells in human intestine and marks a subset of colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):15–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu W, Li H, Hong S-H, Piszczek GP, Chen W, Rodgers GP. Olfactomedin 4 deletion induces colon adenocarcinoma in ApcMin/+ mice. Oncogene. 2016;35(40):5237–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Montenegro-Miranda PS, van der Meer JHM, Jones C, Meisner S, Vermeulen JLM, Koster J, Wildenberg ME, Heijmans J, Boudreau F, Ribeiro A, van den Brink GR, et al. A novel organoid model of damage and repair identifies HNF4α as a critical regulator of intestinal epithelial regeneration. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;10(2):209–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Neyazi M, Bharadwaj SS, Bullers S, Varenyiova Z, Oxford IBD Cohort Study Investigators, Travis S, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, Powrie F, Geremia A. Overexpression of cancer-associated stem cell gene OLFM4 in the colonic epithelium of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(8):1316–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brooks MJ, Chen HY, Kelley RA, Mondal AK, Nagashima K, De Val N, Li T, Chaitankar V, Swaroop A. Improved retinal organoid differentiation by modulating signaling pathways revealed by comparative transcriptome analyses with development in vivo. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;13(5):891–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koike H, Iwasawa K, Ouchi R, Maezawa M, Giesbrecht K, Saiki N, Ferguson A, Kimura M, Thompson WL, Wells JM, Zorn AM, et al. Modelling human hepato-biliary-pancreatic organogenesis from the foregut-midgut boundary. Nature. 2019;574(7776):112–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Serra D, Mayr U, Boni A, Lukonin I, Rempfler M, Challet Meylan L, Stadler MB, Strnad P, Papasaikas P, Vischi D, Waldt A, et al. Self-organization and symmetry breaking in intestinal organoid development. Nature. 2019;569(7754):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim WT, Ryu CJ. Cancer stem cell surface markers on normal stem cells. BMB Rep. 2017;50(6):285–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Asano S, Pal R, Tanaka H-N, Imamura A, Ishida H, Suzuki KGN, Ando H. Development of fluorescently labeled SSEA-3, SSEA-4, and Globo-H glycosphingolipids for elucidating molecular interactions in the cell membrane. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24):6187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruscito I, Darb-Esfahani S, Kulbe H, Bellati F, Zizzari IG, Rahimi Koshkaki H, Napoletano C, Caserta D, Rughetti A, Kessler M, Sehouli J, et al. The prognostic impact of cancer stem-like cell biomarker aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 (ALDH1) in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(1):151–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mori Y, Yamawaki K, Ishiguro T, Yoshihara K, Ueda H, Sato A, Ohata H, Yoshida Y, Minamino T, Okamoto K, Enomoto T. ALDH-dependent glycolytic activation mediates stemness and paclitaxel resistance in patient-derived spheroid models of uterine endometrial cancer. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;13(4):730–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]