Abstract

Shorea macrophylla belongs to the Shorea genus under the Dipterocarpaceae family. It is a woody tree that grows in the rainforest in Southeast Asia. The complete chloroplast (cp) genome sequence of S. macrophylla is reported here. The genomic size of S. macrophylla is 150,778 bp and it possesses a circular structure with conserved constitute regions of large single copy (LSC, 83,681 bp) and small single copy (SSC, 19,813 bp) regions, as well as a pair of inverted repeats with a length of 23,642 bp. It has 112 unique genes, including 78 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes, and four rRNA genes. The genome exhibits a similar GC content, gene order, structure, and codon usage when compared to previously reported chloroplast genomes from other plant species. The chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla contained 262 SSRs, the most prevalent of which was A/T, followed by AAT/ATT. Furthermore, the sequences contain 43 long repeat sequences, practically most of them are forward or palindrome type long repeats. The genome structure of S. macrophylla was compared to the genomic structures of closely related species from the same family, and eight mutational hotspots were discovered. The phylogenetic analysis demonstrated a close relationship between Shorea and Parashorea species, indicating that Shorea is not monophyletic. The complete chloroplast genome sequence analysis of S. macrophylla reported in this paper will contribute to further studies in molecular identification, genetic diversity, and phylogenetic research.

Keywords: Shorea macrophylla, Dipterocarpaceae, Chloroplast genome, Phylogenetic analysis, Monophyletic

Specifications Table

| Subject | Biological Sciences |

| Specific subject area | Omics: Chloroplast Genome |

| Type of data | Sequencing raw reads, assembly, Table, Figure, Graph |

| How data were acquired | Sequencing |

| Data format | Raw Reads |

| Description of data collection | The leaf pieces were washed in sorbitol buffer (0.35 M sorbitol, 1% PVP 40,000, 100 mM Tris-HCL pH 8, 5 mM EDTA pH 8) before bringing resuspended in 500 μL homogenization buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCL pH 8, 25 mM EDTA). Approximately 100 ng of the gDNA, as quantified by the Denovix high sensitivity kit (Denovix) was fragmented to 350 bp using a Bioruptor. Then, library preparation was performed using the NEB Ultra II Illumina library preparation kit. On a NovaSEQ6000, the generated library was sequenced with a read configuration of 2 × 150 bp, yielding about 1 Gb of sequencing data. |

| Data source location | The collection of engkabang leaves is under the permission of Sarawak Forestry Corporation (Reference Number: SFC.810-4/6/1(2022)). The engkabang leaves are provided by the ranger of the Sarawak Forestry Corporation. The collection of leaves is carried out at Semenggoh Wildlife Center, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia (1.402258002376039, 110.31446195505569). |

| Data accessibility | All relevant data are included in this manuscript. The chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla were deposited on GenBank with accession number ON321899 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON321899.1). |

Value of Data

-

•

Complete chloroplast genome is important for improving our understanding of chloroplast biology and for engineering of chloroplast transgenes to enhance plant agronomic features or to develop high-value agricultural or biomedical products.

-

•

As the distributions of Shorea macrophylla is limited to some rainforests in Southeast Asia, the genomic data availability of Shorea spp. is very valuable for future analyses.

-

•

The identification and analysis of the chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla could help researchers better understand the species’ variety and evolutionary links.

1. Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to sequence, assemble and annotate the complete chloroplast genome of the Shorea macrophylla which is deemed an important species for reforestation purpose and provide canopy for many primary rainforests in Southeast Asia region. The improved understanding of the chloroplast genome allows deeper understanding into their photosynthesis capacity and may potentially serves as template for genetic markers identification which further our knowledge on the species distribution and evolution.

2. Data Description

Shorea macrophylla, also known as Engkabang, is a woody tree native to the rainforests. It's mainly found in Kalimantan and Borneo Malaysia [1]. With 196 species spread across 16 genera, Shorea is one of the largest genera in the Dipterocarpaceae family [2]. The chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla has been submitted to GenBank of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with accession number of ON321899. The assembly of S. macrophylla was conducted using NOVOPlasty. The chloroplast genome size of S. macrophylla is 150,778 bp. The assembled chloroplast genome had a typical circular structure and conserved constitute regions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gene map of S. macrophylla chloroplast genome. The genes inside and outside the outer circle are transcribed in clockwise and anticlockwise directions. Genes belonging to different functional groups are coloured with different colours. The inner circle indicates the four regions of the chloroplast genome. IRa, inverted repeat region A; IRb, inverted repeat region B; LSC, large single-copy region; SSC, small single-copy region. The line chart in grey colour shows GC content along the genome.

The chloroplast genome is organized in four separate regions: a large single copy (LSC) segment with a length of 83,681 bp and a small single copy (SSC) region of 19,813 bp. A pair of inverted repeats with a length of 23,642 bp separate the SSC and LSC. A total of 112 genes were discovered as unique genes with only one copy in the genome, including 78 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes and four rRNA genes. Around 17 genes are labelled as duplicate copies in the inverted repeats portions of the genome (six protein-coding genes, seven tRNA genes, four rRNA genes). Among all the genes, 12 genes have one intron, and three genes have two introns (two rps12 and one ycf3 gene). The gene content of S. macrophylla chloroplast genome is shown in Table 1. Content (%) of the four bases was A (31.75%)> T (30.96%) > G (19.02%) > C (18.27%). The genome's GC content is 37.3%, which is comparable to other chloroplast genomes previously published [3,4]. The IR region has a higher GC content (43.3%) than the LSC (35.2%) and SSC regions (31.5%). The IR region's high GC concentration is due to the high GC content of the four ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes found here.

Table 1.

Gene content in chloroplast genomes of Shorea macrophylla.

| Category | Gene groups | Gene Names |

|---|---|---|

| RNA genes | Ribosomal RNA genes (rRNA) | rrn4.5*, rrn5*, rrn16*, rrn23* |

| Transfer RNA genes (tRNA) | trnA-UGC+*, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-GCC, trnG-UCC+, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU*, trnI-GAU+*, trnK-UUU+, trnL-CAA*, trnL-UAA+, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU*, trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG*, trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-UGA, trnS-GGA, trnT-UGU, trnT-GGU, trnV-GAC*, trnV-UAC+, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA, trnfM-CAU. | |

| Ribosomal proteins | Small ribosome subunit | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7*, rps8, rps11, rps12++*, rps14, rps15, rps16+, rps18, rps19 |

| Transcription | Large ribosomal subunit | rpl2+*, rpl14, rpl16, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23*, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| DNA dependent RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1+, rpoC2 | |

| Protein-coding genes | Photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ, pafI/ycf3++ |

| Photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbT, psbZ, pbf1 | |

| Subunit of cytochrome | petA, petB+, petD+, petG, petL, petN, | |

| Subunit of synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF, atpH, atpI, | |

| Large subunit of rubisco | rbcL | |

| NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA+, ndhB+*, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| ATP dependent protease subunit P | clpP1 | |

| Chloroplast envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Other genes | Maturase | matK |

| Subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase | accD | |

| C-type cytochrome synthesis | ccsA | |

| Hypothetical proteins | ycf2*, ycf4/pafII | |

| Component of TIC complex | ycf1. |

Gene with one intron

Gene with two introns

Gene with multiple copies

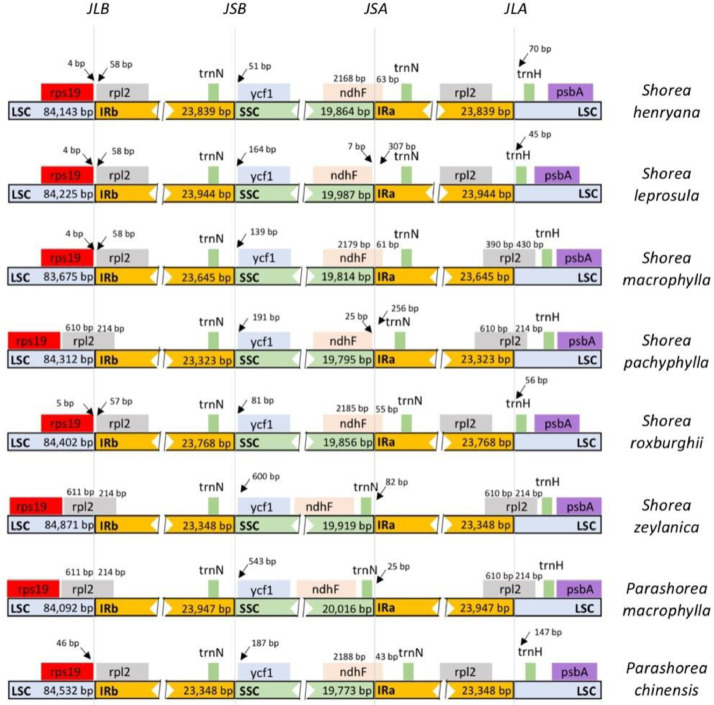

The IR region contraction and expansion are evolutionary events that are assumed to be the major drivers of size differences in chloroplast genomes, making them excellent for studying the phylogeny and evolution of chloroplast genomes in early land plant lineages. We compared the IR boundaries of six Shorea species, including Shorea macrophylla and two closely related Parashorea species, based on phylogenetic analyses. Fig. 2 shows that the majority of them share a similar structure. In all the eight species, the psbA, trnH and rps19 genes are completely covered by LSC regions. The rpl2 gene are found fully embedded in IR region for S. henryana, S. leprosula, S. roxburghii and P. chinensis, however the rpl2 gene expanded to LSC region for S. macrophylla, S. pachyphylla, S. zeylanica and P. macrophylla. ndhF gene of S. leprosula, S. pachyphylla, S. zeylanica and P. macrophylla are found completely in SSC region; but in some of the species, ndhF gene are embedded to the IR region. The IRb/SSC boundary is the most conserved, since all the ycf1 gene of all the observed species are all completely located in the SSC region, however the location of ycf1 gene to the boundary varies in all the species, ranging from 51 to 600 bp.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the borders of the LSC, SSC and IR regions among the eight chloroplast genomes.

Based on protein-coding genes, the frequency of codons in the cp genome of S. macrophylla was estimated. The coding sequences for protein-coding genes were 78,654 bp long, with 26,218 codons encoded. AUU (ILE) was the most common codon (1,075 codons), whereas UGC (CYS) was the least common (77 codons). This may be due to their high sensitivity to physiological and environmental factors. With the exception of Methionine (AUG) and Tryptophan (UGG), whose relative value of synonymous codon usage (RSCU) was one, the usage of most codons was biased. Five codons were overrepresented (RSCU > 1.6) while the majority were underrepresented (RSCU < 0.6). The codon is strongly favoured if the RSCU is more than one, and it is used more frequently than expected. If the value is less than one, it is considered less preferred and is utilised less frequently than expected. Table 2 shows the codon usage in further detail. In the chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla, a study of codon use revealed a preference for T and A at the third codon position (Table 3).

Table 2.

Codon usage of S. macrophylla chloroplast genomes.

| Amino acid | Codon | Count | RSCU | tRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phe | UUU | 1008 | 1.35 | |

| Phe | UUC | 490 | 0.65 | trnF-GAA |

| Leu | UUA | 844 | 1.83 | trnL-UAA |

| Leu | UUG | 572 | 1.24 | trnL-CAA |

| Leu | CUU | 586 | 1.27 | |

| Leu | CUC | 195 | 0.42 | |

| Leu | CUA | 377 | 0.82 | trnL-UAG |

| Leu | CUG | 194 | 0.42 | |

| Ser | AGU | 943 | 1.51 | |

| Ser | AGC | 307 | 0.49 | trnS-GCU |

| Ser | UCU | 581 | 1.73 | |

| Ser | UCC | 314 | 0.94 | trnS-GGA |

| Ser | UCA | 394 | 1.17 | trnS-UGA |

| Ser | UCG | 186 | 0.55 | |

| Tyr | UAU | 774 | 1.60 | |

| Tyr | UAC | 194 | 0.40 | trnY-GUA |

| STOP | UAA | 41 | 1.48 | |

| STOP | UAG | 27 | 0.98 | |

| STOP | UGA | 41 | 1.48 | |

| Cys | UGU | 774 | 1.60 | |

| Cys | UGC | 194 | 0.40 | trnC-GCA |

| Trp | UGG | 27 | 0.98 | trnW-CCA |

| Pro | CCU | 425 | 1.56 | |

| Pro | CCC | 201 | 0.74 | |

| Pro | CCA | 309 | 1.14 | trnP-UGG |

| Pro | CCG | 153 | 0.56 | |

| His | CAU | 468 | 1.52 | |

| His | CAC | 146 | 0.48 | trnH-GUG |

| Gln | CAA | 719 | 1.51 | trnQ-UUG |

| Gln | CAG | 231 | 0.49 | |

| Arg | CGU | 353 | 1.32 | trnR-ACG |

| Arg | CGC | 116 | 0.43 | |

| Arg | CGA | 374 | 1.40 | |

| Arg | CGG | 99 | 0.37 | |

| Arg | AGA | 468 | 1.75 | trnR-UCU |

| Arg | AGG | 191 | 0.72 | |

| Ile | AUU | 1075 | 1.46 | |

| Ile | AUC | 465 | 0.63 | trnI-GAU |

| Ile | AUA | 672 | 0.91 | |

| Met | AUG | 582 | 1.00 | trnM-CAU |

| Thr | ACU | 497 | 1.56 | |

| Thr | ACC | 235 | 0.74 | trnT-GGU |

| Thr | ACA | 396 | 1.25 | trnT-UGU |

| Thr | ACG | 143 | 0.45 | |

| Asn | AAU | 943 | 1.51 | |

| Asn | AAC | 307 | 0.49 | trnN-GUU |

| Lys | AAA | 1043 | 1.47 | trnK-UUU |

| Lys | AAG | 377 | 0.53 | |

| Val | GUU | 516 | 1.46 | |

| Val | GUC | 182 | 0.52 | trnV-GAC |

| Val | GUA | 497 | 1.41 | trnV-UAC |

| Val | GUG | 214 | 0.61 | |

| Ala | GCU | 628 | 1.77 | |

| Ala | GCC | 224 | 0.63 | |

| Ala | GCA | 382 | 1.08 | trnA-UGC |

| Ala | GCG | 184 | 0.52 | |

| Asp | GAU | 884 | 1.58 | |

| Asp | GAC | 232 | 0.42 | trnD-GUC |

| Glu | GAA | 1051 | 1.46 | trnE-UUC |

| Glu | GAG | 388 | 0.54 | |

| Gly | GGU | 577 | 1.31 | |

| Gly | GGC | 176 | 0.40 | trnG-GCC |

| Gly | GGA | 697 | 1.58 | trnG-UCC |

| Gly | GGG | 310 | 0.70 |

Table 3.

The S. macrophylla chloroplast genome features.

| Regions | Positions | Length (bp) | T/U (%) | C (%) | A (%) | G (%) | AT/U (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome | 150,778 | 31.7 | 19.0 | 31.0 | 18.3 | 62.7 | |

| LSC | 83,681 | 32.9 | 18.1 | 31.7 | 17.3 | 64.6 | |

| IRa | 23,642 | 27.8 | 20.4 | 28.8 | 23.0 | 56.6 | |

| SSC | 19,813 | 34.5 | 16.8 | 34.0 | 14.7 | 68.5 | |

| IRb | 23,642 | 28.8 | 23.0 | 27.8 | 20.4 | 56.6 | |

| Protein coding genes | 78654 | 31.3 | 17.7 | 30.5 | 20.5 | 61.8 | |

| 1st position | 26218 | 23.5 | 18.9 | 30.4 | 27.2 | 53.9 | |

| 2nd position | 26218 | 32.4 | 20.0 | 29.8 | 17.8 | 62.2 | |

| 3rd position | 26218 | 37.9 | 14.1 | 31.6 | 16.4 | 69.5 | |

| tRNA | 2791 | 24.9 | 23.6 | 22.1 | 29.4 | 47.0 | |

| rRNA | 9050 | 18.7 | 23.6 | 26.1 | 31.6 | 44.8 |

SSRs were detected in abundance across S. macrophylla’s chloroplast genome. SSRs from chloroplast genomes can be used to explore evolutionary relationships and population genetics because of their high polymorphism rates and consistent repetition. Most SSRs are made up of A or T units, contributing to the AT richness of the chloroplast genome. The chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla contained 262 SSRs, and their distribution was studied. The most common SSR was A/T (61.83%), followed by AAT/ATT (11.45%) and AAG/CTT (9.54%) (Table 4). Furthermore, depending on the number of repeats, mononucleotide and dinucleotide SSRs prefer bases that include A/T units. The details of the SSR annotations are available as supplementary document (Supplementary table 1).

Table 4.

The frequency of identified microsatellite motifs in S. macrophylla chloroplast genome.

| Repeats | Number of SSRs identified |

|---|---|

| A/T | 162 |

| C/G | 5 |

| AT/AT | 18 |

| AAC/GTT | 3 |

| AAG/CTT | 25 |

| AAT/ATT | 30 |

| ACT/AGT | 1 |

| AGC/CTG | 3 |

| ATC/ATG | 2 |

| AAAT/ATTT | 3 |

| AATC/ATTG | 1 |

| AATG/ATTC | 2 |

| ATCC/ATGG | 1 |

| AAAAT/ATTTT | 1 |

| AATAT/ATATT | 5 |

Forward (F), palindromic (P), reverse (R) and complement (C) are the four forms of long repeat sequences, and the repetition length should be larger than 30 bp. A total of 43 long repeat sequences have been discovered. The size of repetitive sequences in the chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla in between 30 and 56 bp are the majority, and almost all are F- or P-type long repeats, with two R- and one C-type long repeats.

Furthermore, the findings of the DNAsp sliding window analysis revealed numerous regions with significantly varied nucleotide sequences between the complete chloroplast genome of six Shorea species and two Parashorea species. The IR regions have substantially less nucleotide variability than the SSC and LSC regions. The determined average nucleotide diversity (Pi) value was 0.01297. There are 7 mutational hotspots discovered in the LSC region with remarkably high Pi values (>0.04) which include ycf2, psbI-trnG, ndhA-ndhI, psbZ-trnG, rps12-ndhB, rpl33-rpoA, rpoA-psbB. In the SSC area, no mutational hotspots have been observed. The rpoC1 gene, on the other hand, is accommodated in the IR regions high Pi values (>0.04). These regions approximate species-level nucleotide substitutions, allowing researchers to investigate and develop molecular markers that are critical for plant taxonomy and identification. Fig. 3 depicts the nucleotide diversity (Pi) graph.

Fig. 3.

Nucleotide diversity analysis of the whole chloroplast genome. Window length: 600 bp; Step size: 200 bp. X-axis: midpoint positions of a window; Y-axis: nucleotide diversity between S. macrophylla and five other Shorea and two Parashorea species.

PREPACT was used to predict RNA editing sites in chloroplast genomes. The first nucleotide of the first codon was used in all analyses. The amino acids Serine and Leucine were shown to be the most frequently transformed in the codon site, according to findings. With Gossypium hirsutum as a reference, the algorithm revealed 178 editing sites in the genome of S. macrophylla, dispersed across 83 protein-coding genes, but no editing sites in the tRNA or rRNA genes. Table 5 lists the details for RNA editing sites. The ycf1 gene has the most editing sites (20 sites), followed by rpoC2 which has 13 editing sites, and ycf2 and matK, which both have ten editing sites. There are 50 genes with 1 to 8 editing sites. The remaining genes (psbA, psbK, psbI, atpH, atpI, petN, psbM, psbD, psbZ, ycf3, ndhJ, atpE, atpB, rbcL, psbL, psbE, petG, psaJ, rps18, rps12, clpP, petD, rps11, rpl14, rpl16, rps19, rpl2, rps15, ndhI, ndhE, psaC, rpl32) do not have predicted RNA editing sites in the first nucleotide of the first codon. About 60 (33.71%) RNA editing events were predicted to occur in the first position of the codon, 118 (66.29%) in the second position, and none in the third position. With 35 sites (19.66%), conversion of serine (polar) to leucine (non-polar) was the most observed amino acid modification because of RNA editing. This was followed by Alanine to Valine (25 sites, 14.04%) and Serine to Phenylalanine (24 sites, 13.48%). By using Gossypium hirsutum as reference genome, 50 genes were predicted to have RNA editing sites.

Table 5.

Conversion of amino acids at RNA editing sites.

| Conversion of amino acid (Single-Letter Amino Acid Code) | Conversion of amino acid | Number of RNA editing sites |

|---|---|---|

| A -> V | Alanine -> Valine | 25 |

| H -> Y | Histidine -> Tyrosine | 10 |

| L -> F | Leucine -> Phenylalanine | 21 |

| P -> F | Proline -> Phenylalanine | 3 |

| P -> L | Proline -> Leucine | 15 |

| P -> S | Proline -> Serine | 20 |

| S -> F | Serine -> Phenylalanine | 24 |

| S -> L | Serine -> Leucine | 35 |

| R -> C | Arginine -> Cysteine | 4 |

| R -> W | Arginine -> Tryptophan | 3 |

| T -> I | Threonine -> Isoleucine | 13 |

| T -> M | Threonine -> Methionine | 5 |

By using the annotation of Shorea macrophylla as a reference, the mVISTA program was used to align the chloroplast genomes and visualise the pattern of sequence identity among closely related species with S. macrophylla, including S. henryana, S. leprosula, S. pachyphylla, S. roxburghii, S. zeylanica, P. chinensis and P. macrophylla. Overall, coding regions were more conserved than non-coding regions, with most variations were detected in non-coding sequences. The sequences of exons and UTRs were nearly identical throughout the eight taxa since they had a similar structure and gene order (Fig. 4). In addition, as shown in other taxa's chloroplast genome research, the LSC and SSC regions diverged more than the IR regions [5], [6], [7]. In the LSC, the majority of exons are conserved in intergenic spacers with a high amount of divergence (>50%, as determined by the white space seen across alignments).

Fig. 4.

The shuffle-LAGAN program analyzed the comparative analysis of S. macrophylla with Shorea and Parashorea species. The percentage of identity is shown on the vertical axis, which ranges from 50 to 100%, while the horizontal axis represents the position in the chloroplast genome. Each arrow indicates the annotated gene in the reference genome and the direction of its transcription. Genomic regions are color-coded into exons(purple), UTR (neon blue) and CNS (pink).

To investigate the evolutionary position of S. macrophylla in the Dipterocarpaceae family, protein coding genes from 24 species under Dipterocarpaceae family and two species from outgroup families (Gossypium thurberi and Bixa orellana) were chosen for phylogenetic analysis. The phylogenetic tree is shown in Fig. 5. From the phylogenetic tree, we discovered that the S. macrophylla was isolated from these wild relative species in the tree. Outgroups were segregated from Dipterocarpaceae species, which constituted a clade. Hopea species from the Dipterocarpaceae family made up the first subclade. Neobalanocarpus species made up the second subclade. Shorea and Parashorea species make up the third and fourth subclades respectively. While the fifth and the sixth clade are consisting of Dipterocarpus and Vatica species. Among the 25 Dipterocarpaceae species, Dryobalanops aromatica is the furthest away. Except for Shorea, which formed a clade with Parashorea species, each genus clustered together to create a single subclade. The whole chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla provides insight into tree plants for future evolutionary studies on this species, as well as a reference to help tree species conservation and improve desirable traits in S. macrophylla breeding.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic relationships of S. macrophylla with other Dipterocarpaceae family species and two outgroups based on their protein-coding genes. The bootstrap value based on 1000 replicates is shown on each node. The subclades are drawn with Shorea sp. subclade drawn in red colour and Parashorea sp. subclade drawn in green colour. The result shown Shorea genus is not monophyletic.

3. Experimental Design, Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant material, DNA extraction, and sequencing

The DNA was extracted from 50 mg of Engkabang leaves. Experimental research and field studies on plants in this study, including the collection of plant material are all complied with the ethical standards and legislation. The leaf pieces were washed in sorbitol buffer (0.35 M sorbitol, 1% PVP 40,000, 100 mM Tris-HCL pH 8, 5 mM EDTA pH 8) before bringing resuspensed in 500 μL homogenization buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCL pH 8, 25 mM EDTA) [8]. A 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing 2 mL steel beads was filled with 500 μL of the resuspended material. Homogenization took 30 minutes on a vortexer spinning at 4,000 rpm. After that, ⅔ vol of saturated NaCl was added to the homogenate, followed by 5 minutes incubation on ice to precipitate proteins [9]. The cells are then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 x g. To precipitate the DNA pellet, the supernatant was combined with 1x volume of isopropanol and centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 10 minutes. The DNA pellet was resuspended in 0.1 X TE buffer (1 mM Tris-HCL pH 8, 0.1 mM EDTA) after being washed twice with 75% ethanol. Approximately 100 ng of the gDNA, as quantified by the Denovix high sensitivity kit (Denovix) was fragmented to 350 bp using a Bioruptor. Then, library preparation was performed using the NEB Ultra II Illumina library preparation kit. On a NovaSEQ6000, the generated library was sequenced with a read configuration of 2 × 150 bp, yielding about 1 Gb of sequencing data. With a total base of 1.7 Gb, 2 × 5.83 million paired-end reads were generated. The fastq file contained raw data that is without adapter and had not been quality trimmed. The filtered readings were assembled into complete chloroplast genomes using NOVOPlasty with Gossypiodes kirkii rbcL sequence as the seed sequence. The chloroplast genome was then mapped to the Shorea pachyphylla complete chloroplast genome.

3.2. Genome annotation and codon usage analysis

Using the complete chloroplast genome sequences of Shorea pachyphylla and Shorea zeylanica as references, GeSeq was used to annotate the chloroplast genomes of Shorea macrophylla [10]. The GeSeq software tool was used to execute BLAST searches against S. pachyphylla NCBI RefSeq data. Comparative analysis between S. pachyphylla, S. zeylanica, S. roxburghii, S. henryana and S. leprosula was conducted to further verify the manual annotation. To ensure functionality, all protein-coding nucleotide sequences (CDS) were checked in their amino acids using MEGA X to fix premature and truncated stop codons [11]. tRNA genes were identified by the trnAscan-SE server [12]. Gene homologies and ontologies were verified using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [13]. Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) was used to create and illustrate the structural characteristics of the chloroplast genome map of S. macrophylla [14]. MEGA 11.0 was used to examine the relative synonymous codon usage (RCSU) values, base composition and codon usage [11].

3.3. Short Sequence repeats (SSRs) and long repeat structure

The MIcroSAtellite (MISA) web tool was utilised to identify short sequence repeats (SSRs) [15]. The minimal repeat unit criteria for mononucleotide SSRs were established at eight, for dinucleotide SSRs at five, and for trinucleotide, tetranucleotide, pentanucleotide, and hexanucleotide SSRs at three. Complement, palindromic, reverse and forward repeat sequences were identified and located using REPuter [16]. The repeat sizes were kept to a minimum of 30 bp, with sequence identities of over 90%.

3.4. Internal repeat contraction and expansion

The expansion and contraction of the IR regions (IRa and IRb) at four junction sites (namely LSC/IRb, IRb/SSC, SSC/IRa and IRa/LSC) between five different Shoreas and two Parashoreas from Dipterocarpaceae family (S. henryana, S. leprosula, S. pachyphylla, S. roxburghii, S. zeylanica, P. chinensis, P. macrophylla) were verified and plotted manually.

3.5. Comparative and divergence analysis of chloroplast genomes of S. macrophylla and closely related species

To compare against S. henryana, S. leprosula, S. pachyphylla, S. roxburghii, S. zeylanica, P. chinenesis and P. macrophylla sequences from GenBank, the complete chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla was used as a reference genome. mVISTA program was used to align the sequences in Shuffle-LAGAN mode [17,18]. Nucleotide variability was calculated using DNAsp software with a 200 bp step size and a 600 bp window length [19].

3.6. RNA editing analysis

The PREPACT online tool was used to anticipate potential RNA editing sites present in the CDS of S. macrophylla with the default search option and Gossypium hirsutum as the reference genome [20].

3.7. Phylogenetic analysis

All protein-coding genes in the chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla, as well as 24 species under the Dipterocarpaceae family (Dipterocarpus alatus, Dipterocarpus gracilis, Dipterocarpus intricatus, Dipterocarpus turbinatus, Dryobalanops aromatica, Hopea chinensis, Hopea dryobalandoides, Hopea hainanensis, Hopea mollissima, Hopea odorata, Hopea reticulata, Neobalanocarpus heimii, Parashorea chinensis, Parashorea macrophylla, Shorea henryana, Shorea leprosula, Shorea pachyphylla, Shorea roxburghii, Shorea zeylanica, Vatica guangxiensis, Vatica mangachapoi, Vatica odorata, Vatica rassak, Vatica xishuangbannaensis) and two outgroup gymnosperms (Gossypium thurberi and Bixa orellana) were selected as input for phylogenetic analysis. The sequences were first aligned using Clustal W in MEGA 11.0 [11]. This was followed by running a Model Test via MEGA 11.0 to select the best model for the maximum likelihood tree construction [11]. MEGA 11.0 constructed the maximum likelihood family tree, with parameter GTR + I + G nucleotide substitution model and 1000 bootstrap replications [11].

Ethics Statement

Experimental research and field studies on plants in this study, including the collection of plant material complied with the guidelines and legislation. The collection of engkabang leaves is under the permission of Sarawak Forestry Corporation (Reference Number: SFC.810-4/6/1(2022)). The engkabang leaves are provided by the ranger of the Sarawak Forestry Corporation.

Availability of Data and Materials

All relevant data are included in this manuscript. The chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla were deposited on GenBank with accession number ON321899 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON321899.1).

Credit Author Statement

Ivy Yee Yen Chew: Collected and analysed all data and wrote the manuscript; Hung Hui Chung: Supervised the experimentation process, edited the manuscript as well as provided the funding for this research; Leonard Whye Kit Lim, Melinda Mei Lin Lau and Han Ming Gan: Assisted with the interpretation of results, review and edited the manuscript; Boon Siong Wee and Siong Fong Sim: Reviewed and edited the manuscript as well as supplied funding for this research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged Tun Zaidi Chair had fully funded this research with grant number F07/TZC/2164/2021 to Dr. Chung Hung Hui.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.dib.2023.109029.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Chai E.O.K. University of Edinburgh; Malaysia: 1998. Aspects of a Tree Improvement Programme for Shorea Macrophylla (de Vriese) Ashton in Sarawak. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashton P.S. Dipterocarpaceae. Flora Malesiana. 1982;9:237–552. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu Y., Han Y., Peng Y., Tian Z., Zeng P., Zong H., Zhou T., Cai J. Comparative and phylogenetic analyses of eleven complete chloroplast genomes of Dipterocarpoideae. Chinese Med. (United Kingdom) 2021;16:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13020-021-00538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alzahrani D., Albokhari E., Abba A., Yaradua S. The first complete chloroplast genome sequences in Resedaceae: Genome structure and comparative analysis. Sci. Prog. 2021;104:1–18. doi: 10.1177/00368504211059973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian J., Song J., Gao H., Zhu Y., Xu J., Pang X., Yao H., Sun C., Li X., Li C., Liu J., Xu H., Chen S. The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Medicinal Plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim L.W.K., Chung H.H., Hussain H. Complete chloroplast genome sequencing of sago palm (Metroxylon sagu Rottb.): Molecular structures, comparative analysis and evolutionary significance. Gene Reports. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2020.100662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.L. Gu, Ti. Su, M.-T. An, G.-X. Hu, The Complete Chloroplast Genome of the Vulnerable Oreocharis esquirolii (Gesneriaceae): Structural Features, Comparative and Phylogenetic Analysis, Plants. 9 (2020). 10.3390/plants9121692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Inglis P.W., Marilia de Castro R.P., Resende L.V., Grattapaglia D. Fast and inexpensive protocols for consistent extraction of high quality DNA and RNA from challenging plant and fungal samples for high-throughput SNP genotyping and sequencing applications. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller S.A., Dykes D.D., Polesky H.F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tillich M., Lehwark P., Pellizzer T., Ulbricht-Jones E.S., Fischer A., Bock R., Greiner S. GeSeq - Versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2017;45:W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamura K., Stecher G., Kumar S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe T.M., Chan P.P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2016;44:W54–W57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanehisa M., Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greiner S., Lehwark P., Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2019;47:W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beier S., Thiel T., Münch T., Scholz U., Mascher M. MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtz S., Choudhuri J.V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frazer K.A., Pachter L., Poliakov A., Rubin E.M., Dubchak I. VISTA: Computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2004;32:273–279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brudno M., Malde S., Poliakov A., Do C.B., Couronne O., Dubchak I., Batzoglou S. Glocal alignment: Finding rearrangements during alignment. Bioinformatics. 2003;19 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozas J., Ferrer-Mata A., Sanchez-DelBarrio J.C., Guirao-Rico S., Librado P., Ramos-Onsins S.E., Sanchez-Gracia A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenz H., Hein A., Knoop V. Plant organelle RNA editing and its specificity factors: Enhancements of analyses and new database features in PREPACT 3.0. BMC Bioinf. 2018;19:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in this manuscript. The chloroplast genome of S. macrophylla were deposited on GenBank with accession number ON321899 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON321899.1).