Abstract

Objective

To compare the learning curve of clinicians with different levels of embryo transfer (ET) experience using the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) Embryo Transfer Simulator.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Single large university-affiliated in vitro fertilization center.

Patient(s)

Participants with 3 levels of expertise with ET were recruited: “group 1” (Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility attendings), “group 2” (Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility nurses, advance practice providers, or medical assistants), and “group 3” (Obstetrics and Gynecology resident physicians).

Intervention(s)

All participants completed ET simulation training using uterine cases A, B, and C (easiest to most difficult) of the ASRM ET Simulator. Participants completed each case 5 times for a total of 15 repetitions.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

The primary outcome was ET simulation scores analyzed at each attempt for each uterine case, with a maximum score of 155. Secondary outcomes included self-assessed comfort levels before and after the completion of the simulation and total duration of ET. Comfort was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale.

Result(s)

Twenty-seven participants with 3 different levels of expertise with ET were recruited from December 2020 to February 2021. For cases A and B, median total scores were not significantly different between groups 1 and 3 at first or last attempts. Group 2 did not perform as well as group 3 at the beginning of case A or group 1 at the end of case B. All groups demonstrated a decrease in total time from the first attempt to the last attempt for both cases. For case C, the “difficult” uterus, groups 2 and 3 exhibited the greatest improvement in total median score: from 0 to 75 from the first to last attempt. Group 1 scored equally well from first through last attempts. Although no one from group 2 or 3 achieved a passing score with the first attempt (80% of the max score), approximately 30% had passing scores at the last attempt. Groups 1 and 3 showed a significant decrease in total time across attempts for case C. Following simulation, 100% of groups 2 and 3 reported perceived improvement in their skills. Group 3 showed significant improvement in comfort scores with Likert scores of 1.71 ± 0.76 and 1.0 ± 0.0 for the “Easy” and “Difficult” cases, respectively, before simulation and 4.57 ± 0.53 and 2.4 ± 1.1 after simulation.

Conclusion(s)

The ASRM ET Simulator was effective in improving both technical skill and comfort level, particularly for those with little to no ET experience and was most marked when training on a difficult clinical case.

Key Words: Simulation, embryo transfer, training, education

Embryo transfer (ET) is the last crucial step of an in vitro fertilization (IVF) process. The goal of ET is to deliver the embryo into the optimal location within the uterine cavity without traumatizing the endometrium. The ET procedure is a key determinant of implantation success and thus, overall IVF success. Several causes of ET failure have been described including embryo quality and ploidy status, uterine receptivity, mechanical factors, and experience of the providers (1, 2, 3, 4).

Several studies have shown a significant variation in pregnancy rates among physicians performing ETs (5, 6, 7). This difference has even been seen with physicians within the same practice using similar protocols, demonstrating the need for standardization of training (8). Recent studies have also highlighted large differences in the adequacy of ET training across fellowship programs (9). A recent survey of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility (REI) fellowship programs in the United States revealed that 21% of fellows had never performed an ET and nearly half of third year fellows had performed fewer than 10 ETs in their fellowship (10). Other surveys have demonstrated similar findings (10, 11, 12).

In response to the accumulating evidence regarding the lack of standardization and the clinical gap in training in regards to the ET procedure, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) formed an Embryo Transfer Advisory Panel (13). In 2017, this panel developed a “common practice” document based on a systematic review of the literature on the various steps of the ET (13). In addition, ASRM partnered with VirtaMed AG (Zurich, Switzerland) to create a high-fidelity virtual reality ET simulator to aid clinicians in attaining proficiency in the ET procedure.

Simulation training has the potential to improve the clinician’s ability to gain critical medical knowledge and skills that will enable them to deliver safer and more proficient medical care (14). There has been accumulating evidence in recent years across nearly all medical specialties demonstrating the effectiveness of simulation-based training for trainees of all levels (15, 16, 17, 18). Designed medical simulators have helped trainees improve their efficiency and skills for various procedures (19). Given the importance of the ET procedure and lack of adequate training, there has been a recent focus on ET simulation with recent studies demonstrating the effectiveness of ET simulation training for REI fellows (20, 21).

The present study aims to evaluate the impact of embryo transfer simulation training on performance and confidence in 3 groups with differing ET skill level.

Materials and methods

Study Participants

This study was conducted during a 3-month period between December 2020 and February 2021. Participants were recruited from a single large IVF center and its affiliated university teaching hospital. We aimed to recruit at least 10 participants in each of 3 categories of expertise with ET: “group 1” (REI attendings whom perform ETs routinely), “group 2” (REI nurses, advance practice providers, or medical assistants who routinely perform intrauterine inseminations [IUIs]), and “group 3” (resident physicians in Obstetrics and Gynecology who have rarely or never performed IUIs or ET). For simplicity, the 3 groups will be referred to as “group 1,” “group 2,” and “group 3.” The exclusion criterion was any previous training or experience on the ASRM ET simulator. No REI fellows were included in this study as all fellows in our program have completed the ASRM ET Stimulator Course. Participants were recruited by E-mail and verbal consent was given to participate in the study. Participation was completely voluntary and no compensation was provided. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Protocol # 2019P000777).

Simulation Protocol

A single study investigator (A.Q.L.) ran all simulation sessions with the study participants. The participants scheduled a 1-hour one-on-one session to complete the simulation. At the beginning of the simulation session, participants were asked to fill out a presimulation survey with questions about demographics, experience, and presumed comfort level with ET. Comfort level questions were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 being very uncomfortable and 5 being very comfortable. Group 1 was assessed on ET preferences including type of catheter used (Wallace vs Rocket) and technique (Afterload vs Direct). All data were deidentified and participants were assigned a numerical ID to link survey data with simulator data. Each participant then received an identical 5-minute didactic training on the steps of ET, troubleshooting tips, and how the simulator worked. Metric scoring and key goals of the ET were clearly explained. No additional verbal training or tips were given during the remainder of the simulator session.

Participants completed 3 cases, in a single session, which represented increasing levels of difficulty: case A was a short axial uterus with a straight cervix, case B was an anteverted uterus with a cervical canal that initially angled downward then sharply upward, and case C was an anteverted uterus with a tortuous cervix. Each case was completed 5 times, for a total of 15 repetitions. Due to the fact that case C could be extremely challenging, a time limit of 3 minutes was given to successfully navigate the cervical canal (from time of simulation start to time the catheter passes the internal cervical os). Further details on the simulator and uterine cases have been previously described (22). If the time limit was exceeded, the simulation was manually ended and the procedure was deemed incomplete with a score of 0.

Every simulation was performed in an identical manner. All participants were taught the afterload technique using a Wallace transfer catheter. The afterload technique involves inserting an empty soft catheter into the uterine cavity before loading the embryo(s) into the transfer catheter, then threading the loaded catheter through the outer sheath of the positioned catheter already in place. This technique was chosen as it is the preferred method for ET at our institution. The simulator options were set to automatic ultrasound scanning, no narration, and no visual “cheats” allowed (eg, cartoon depictions of the catheter location). The research investigator played the role of the “embryologist” and assisted the participant by running the simulation machine and supporting the catheter when necessary. The participant performed all steps of the ET, including the plunge of the embryo. The simulator has numerous sensors throughout and records the movement of the catheter through the case, assigning points for accuracy in positioning and timing the procedure from start to finish.

After each attempt, the simulator reported a score with details where deductions were made, if any. The total score (maximum 155) was a summation of 5 different metrics: (1) number of touches to the fundus; (2) transfer catheter tip in the ideal zone during embryo expulsion; (3) transfer catheter tip is >1 cm from fundus; (4) duration of ET; and (5) number of times the inner catheter passes the internal cervical os. The passing score was defined as 80% (124 of a possible 155 points) in accordance with prior studies of REI fellows. The participant was instructed to use the feedback obtained from the score report to adjust their technique for the next attempt. After completion of the simulation session, the participant then filled out a postsimulation survey.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report demographic and survey data on study participants. Medians were calculated with interquartile ranges (IQR) and nonparametric tests were used to test for statistical significance. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare independent data between groups and Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for paired data. A P value below 0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

Study Participants

Twenty-seven participants were recruited during the study period. Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the participants. Of these participants, there were 10 (37.0%) in group 1, 10 (37%) in group 2, and 7 (26%) in group 3. All participants completed the simulation session and the anonymous pre- and postsimulation survey. Group 1 had the most years of work experience in their current role with an average of 18.2 ± 8.3 years. Group 2 and group 3 had fewer average years of professional practice, 13.2 ± 10.8 and 2.6 ± 0.8 years, respectively. All of group 3 had used simulation training for other obstetrics and gynecology procedures in the past, whereas approximately half of group 2 (50%) and group 1 (40%) had used simulation to learn another task. All of group 1 had experience performing both ET and IUIs before the simulation. Neither group 2 nor group 3 had experience with ET before the simulation training. All of group 2 had performed IUIs compared with few in group 3 (14%).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and survey outcomes for ET simulation.

| Characteristics | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 10 | 10 | 7 |

| Years of experience | 18.2 (8.3) | 13.2 (10.8) | 2.6 (0.8) |

| Experience with simulation | 40% | 50% | 100% |

| Found simulation useful | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Has performed IUIs | 100% | 100% | 14% |

| Has performed ETs | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Preferred catheter for ET | |||

| Wallace | 70% | - | - |

| Rocket | 30% | - | - |

| Preferred ET technique | |||

| Afterload | 90% | - | - |

| Direct | 10% | - | - |

| Do you think simulation will improve your skills | 70% | 100% | 100% |

| Do you think simulation did improve your skills | 40% | 100% | 100% |

| Should simulation be a routine part of training | 60% | 100% | 71% |

Notes: Data are shown as mean (standard deviation) or percentage. Only group 1 answered the questions “preferred catheter for ET” and “preferred ET technique.” ET = embryo transfer; IUI = intrauterine insemination.

Seventy percent of group 1 reported a preference for the Wallace catheter compared with the Rocket catheter (30%) for ET. Nearly all of group 1 preferred to use the afterload ET technique (90%) instead of the direct ET technique (10%).

Uterine Cases Simulation Outcomes

Case A

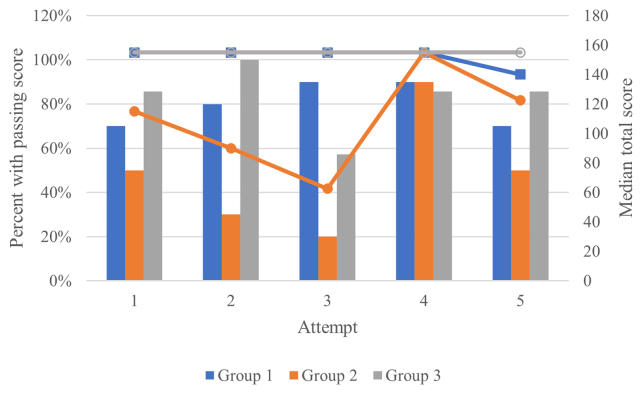

Median total scores and percentage of passing scores across attempts for case A can be seen in Figure 1. Median total scores for all attempts were similar between groups: 155 (IQR, 140–155) versus 102.5 (IQR, 78.75–155) versus 155 (IQR, 155–155) for group 1, group 2, and group 3, respectively. Group 3 and group 1 did not score significantly differently at the first attempt; however, group 2 scored significant lower compared with group 3 (115 vs 155, P=.01). By the last attempt, median total scores were similar across all groups (140 [IQR, 121.3–155], 122.5 [IQR, 90–155], 155 [IQR, 155–155], P=not significant). There was no significant increase in total score seen over time for any of the groups. Over 80% of group 3 and group 1 were able to achieve a passing score (80% of the maximum score) at both the first and last attempt.

Figure 1.

Median total score and percentage with passing score (80% of max, or 124) for case A, short axial uterus.

Median total time of ET at the first and last attempt for the cases can be seen in Supplemental Figure 1 (available online). All groups decreased in median total time from the first to last attempt (P=.02,.01,.02). Group 1 spent the longest time performing ET throughout all attempts.

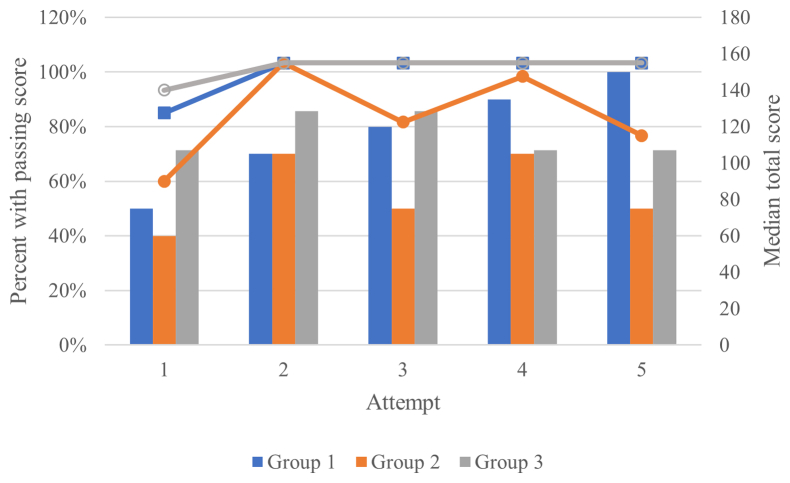

Case B

In case B, median total scores between the groups for all attempts were again similar: 155 (IQR, 140–155) versus 140 (IQR, 90–155) versus 155 (IQR, 132.5–155) for group 1, group 2, and group 3, respectively. Median total scores and percentage of passing scores across attempts for case B can be seen in Figure 2. There were no differences in total score between the groups at the first attempt (127.5, 90, 140, P=not significant). However, group 1 had a significantly higher median score at last attempt compared with group 2 (155 vs 115, P=.008). Only group 1 showed a statistically significant improvement of total score over time (127.5 to 155, P=.01). While only half of group 1 had passing scores with their first attempt, all of group 1 had a passing score with their last attempt. In contrast, 40% of group 2 had passing scores at the first attempt and 50% by the last attempt. Similarly, 71% of group 3 had passing scores at the first and last attempt.

Figure 2.

Median total score and percentage with passing score (80% of max, or 124) for case B, anteverted uterus.

Again, all groups had a decrease in total time of ET from the first to last attempt (P=.01,.02,.03). Similar to case A, group 1 consistently spent a longer time performing the ET compared with groups 2 and 3 (eg, 92.6, 47.0, 62.7 seconds, P=.01,.04).

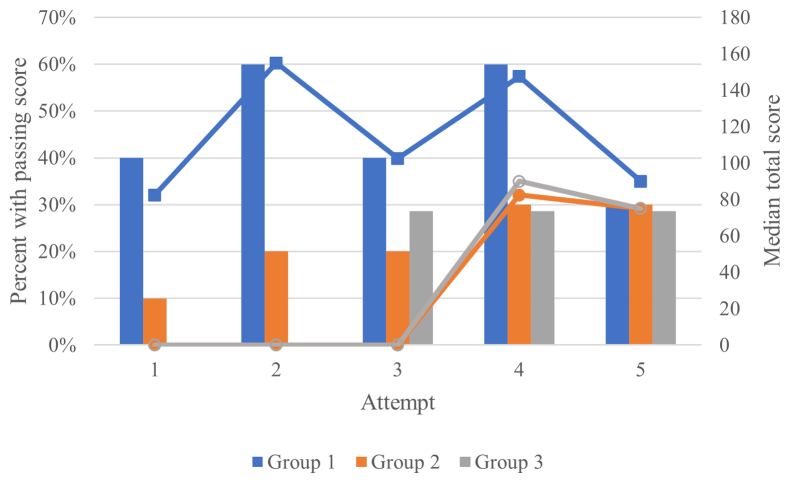

Case C

For case C, median total score for group 1, group 2, and group 3 were 115 (IQR, 0–155), 0 (IQR, 0–90), and 45 (IQR, 0–90), respectively. Median total scores and percentage of passing scores across attempts for case C can be seen in Figure 3. Group 1 had higher median scores with the first attempt compared with group 3 and group 2, however, this only trended but did not reach significance (82.5, 0, 0, P=.06). Groups 2 and 3 improved from a median total score of 0 with first attempt to 75 at last attempt for both groups (P=.09 and P=.07, respectively). Forty percent of group 1 achieved a passing score at first attempt with no improvement over time. Although no one from group 3 and only 10% of group 2 achieved a passing score with their first attempt, approximately 30% had passing scores at the last attempt from both groups. Group 1 received a score of 0 for incomplete procedure secondary to inability to navigate the cervix in the allotted time on 13 of the total number of attempts. Groups 2 and 3 received a score of 0 on 15 and 27 of the total number of attempts, respectively.

Figure 3.

Median total score and percentage with passing score (80% of max, or 124) for case C, anteverted uterus with tortuous cervix.

Both group 1 and group 3 showed significant decreases in total time across the attempts (213.1 to 97.4 seconds, P=.005; 203.8 to 185.3 seconds, P=.03). The total time was similar between all groups at the first attempt. With the last attempt, group 1 was able to perform ET on this case faster compared with group 2 and group 3 (97.4, 177.3, 185.3 seconds), however, this did not reach statistical significance (P=.09,.06).

Survey Outcomes

Survey outcomes can be seen in Table 1. Prior to the simulation, all of group 2 and group 3 and the majority of group 1 (70%) reported they felt simulation training would improve their technical skills. After the simulation, all of group 2 and group 3 reported their technical skills improved with the simulation. Nearly half of group 1 reported improvement. The majority of group 1 (60%), group 2 (100%), and group 3 (71%) felt simulation should be a routine part of training.

The survey also assessed perceived comfort levels with “Easy” and “Difficult” uteri before and after the simulation. Group 1 consistently reported feeling “very comfortable” with the “Easy Uterus” both before and after the simulation, with no changes on the Likert scale score. Group 3 initially reported being neutral to uncomfortable with the “Easy Uterus” with a mean Likert score of 1.71 ± 0.76 (“very uncomfortable” to “uncomfortable”). However, all of group 3 reported being comfortable with a mean score of 4.57 ± 0.53 (P=.01) after the simulation. The majority of group 2 reported being neutral to comfortable with the “Easy Uterus” both before and after the simulation, with no significant improvement in comfort level (3.5 to 3.8, P=.2).

Group 1 again reported feeling consistently comfortable with the “Difficult Uterus” both before and after the simulation (4.7 to 4.8). Group 3 unanimously reported being “very uncomfortable” before simulation for the “Difficult Uterus” with a mean score of 1.0 ± 0.0. Following the simulation, group 3 significantly improved their comfort levels with a mean comfort score of 2.4 ± 1.1 (P=.015). Similar to the “Easy Uterus “simulation, group 2 reported varied levels of comfort before and after the simulation for the “Difficult Uterus” with 30% reporting increased comfort level, 30% reporting unchanged comfort level number, and 40% reporting a decrease in comfort level after the simulation.

Discussion

This study represents one of the first published reports characterizing the performance and confidence in 3 groups as a function of their preexisting ET skill level using the ASRM ET simulator. Improvements in both technical skills of ET and comfort levels were seen, particularly for groups with less clinical experience. The most significant improvement was seen in the most difficult case, with the less experienced groups, groups 2 and 3, attaining nearly the same median scores as the most experienced group, group 1, by the end of the exercise. Additionally, perceptions of comfort increased significantly for the least comfortable group, group 3, across both the “Easy” and “Difficult” cases. These findings are consistent with prior study of the ASRM Embryo Transfer Certificate Course by Ramaniah et al. (22) that demonstrated improvement in technical skills and confidence after simulation-based training for ET for REI fellows.

Technical skill development with the ET procedure is of particular importance as studies have demonstrated that differences in pregnancy rates are dependent on the skill of the individual performing the procedure (5, 6, 7). Furthermore, nearly half of all REI fellows complete their fellowship training performing few to no live ETs (9, 10, 12). Some training programs cite the high-stakes nature of the procedure as the reason for why trainees are not allowed to perform live ETs (10). This highlights the importance of high-fidelity simulation training for this procedure, and the need to verify efficacy of simulation training. Our study shows that ET simulation is effective at improving both technical skills and comfort level with the procedure.

All participants completed the simulation-based training in this study in the same progressive manner: the training was initiated with case A, the “Easy” case with a short axial uterus with a straight cervical canal, then followed by case B, a slight variation with an anteverted uterus, and ultimately case C, the “Difficult” case with a tortuous cervix. This was intentional as it would theoretically allow participants to build on skills learned from prior repetitions. The participant was also able to use the feedback obtained from the detailed score report from each attempt to adjust their technique for future attempts. The total score was made up of 5 different metrics of the ET procedure measured by the simulator and was used as a marker of technical skill. A passing score was defined as 80% of the total possible score in concordance with prior studies using the ASRM ET Simulator. Interestingly, all groups performed relatively well on cases A and B, with a majority scoring above “passing” on all attempts. case C is where the most dramatic learning occurred for groups 2 and 3, although statistical significance was not found because of small numbers. Case C also had the highest number of incomplete attempts with a score of 0 across all groups because of participant inability to navigate the cervix in the allotted time. A secondary outcome metric of time to perform ET was used as a marker of efficiency of the learned skill. All groups significantly decreased their total time in cases A and B with both group 1 and group 3 also decreasing in total time for case C. These data demonstrate that simulation-based training the ASRM ET Simulator allows acquisition of technical skill based on improving total median scores and percentage of passing scores across different levels of difficulty.

Improvements in technical skill with simulation have also been shown to increase confidence levels of trainee’s at all different levels. A prior cross-sectional analysis of fellows partaking in the ET Certificate Course by Barsky et al. (23) demonstrated increases in both technical skills and confidence levels after completion of the course. Ramaiah et al. (22) assessed the ASRM ET Certificate Course through a 2-day simulation workshop for REI fellows. This study showed improvement in both technical skill and confidence among fellows, with the highest increase in reported self-confidence levels in those with the least amount of prior experience with live ETs. The data presented here demonstrates similar findings with group 3 showing the biggest increase in confidence levels throughout the simulation.

Group 1 did well across the simulations with little improvement in scores over time and reported consistently high comfort levels throughout the cases. However, nearly half of group 1 felt the simulator resulted in improvement of their skills, highlighting a benefit to use of simulation even among skilled providers. Of note, the participants in this study from group 1 not only had many years of experience in their roles, but also were recruited from a single high-volume center, each performing greater than 200 ETs per year. Thus, simulation training may show a higher margin of improvement in both ability and comfort of experienced providers at lower volume centers or those with fewer years of clinical experience.

Group 2 had no prior experience with live ET but had other relevant prior experience including routinely performing IUIs. This group universally reported perceived improvement in skills and improved scores in case C, although it did not reach statistical significance. Despite having relevant experience and high perceived levels of comfort before simulation, most of group 2 reported a decrease in comfort after the “Difficult” case. This group highlights that relevant experience with IUI may not translate to technical skill and comfort with the ET procedure, highlighting the need for further simulation-based training specific for ET. These findings are consistent a prior study by Shah et al. (24) showing the pregnancy rate for ETs performed by fellows after a training requirement of 100 IUIs was unchanged.

Group 3 showed the most significant improvement with respect to improvements in scores, time, and perceived comfort. Group 3 were the most facile and comfortable with simulation-based training before this study compared with the other groups as seen in the survey results. This may have contributed to their ability to learn ET by simulation quickly and achieve high scores on early attempts with the easier cases. Additionally, despite not routinely performing IUIs, this group frequently performs other procedures that involve traversing the cervical canal that may explain why this group often scored higher than group 2. Although group 3 in this study consisted of residents rather than fellows, who are the main target audience for ET simulation training, residents are an excellent proxy for fellows as they exhibit the same baseline skillset.

Strengths of this study include reporting the effectiveness of the ASRM ET Simulator in training those of varying levels of expertise, in contrast to studies including only REI fellows. All simulation sessions were conducted by a single investigator, which minimized variability in teaching between participants. All participants performed the simulated ETs in the exact same way. The results were described by both concrete and perceived levels of skill development. These results confirm the value of simulation-based training, particularly in those with the least amount of experience.

Limitations include the small number of participants available to participate in the study, which was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. No REI fellows were included in this study as all eligible fellows had previously completed the ASRM ET Simulator Course. Additionally, no feedback was provided to participants during the training which likely would have resulted in further improved scores over time for trainees with less experience. The outcomes were assessed only during a single session. The primary outcome of ET simulator score is also not validated to pregnancy outcomes. A larger study with more participants would allow better power to detect differences between median total scores. The inclusion of REI fellows, naïve to the ET simulator, would provide an additional group with some prior ET experience compared with group 1 in this study who has a high level of expertise.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the effectiveness of simulation-based training in regard to technical skill development and comfort level for ET, an essential component of successful IVF treatment. Although prior studies have demonstrated that simulation training is effective in other areas of medicine and ET simulation training specifically is effective in training REI fellows, this study shows effectiveness across 3 different skill sets. Many REI fellowships do not provide fellows with the opportunity to perform live ETs leading to new attendings with little to no live experience. This data provides further evidence of the value of simulation training before live procedures.

Acknowledgments

The ASRM ET simulator was on loan to the investigators by Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

K.M.B. has nothing to disclose. A.Q.L. has nothing to disclose. J.S.S. has nothing to disclose. A.K. has nothing to disclose. D.S. has nothing to disclose. A.P. has nothing to disclose. T.L.H has nothing to disclose.

K.M.B. and A.Q.L. should be considered similar in author order.

Supplementary data

Total time to complete embryo transfer for A) Case A, B) Case B, and C) Case C)

References

- 1.Grygoruk C., Sieczynski P., Pietrewicz P., Mrugacz M., Gagan J., Mrugacz G. Pressure changes during embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:538–541. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kovacs G.T. What factors are important for successful embryo transfer after in-vitro fertilization? Hum Reprod. 1999;14:590–592. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sallam H.N. Embryo transfer: factors involved in optimizing the success. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:289–298. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000169107.08000.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoolcraft W.B., Surrey E.S., Gardner D.K. Embryo transfer: techniques and variables affecting success. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:863–870. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hearns-Stokes R.M., Miller B.T., Scott L., Creuss D., Chakraborty P.K., Segars J.H. Pregnancy rates after embryo transfer depend on the provider at embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00582-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelini A., Brusco G.F., Barnocchi N., El-Danasouri I., Pacchiarotti A., Selman H.A. Impact of physician performing embryo transfer on pregnancy rates in an assisted reproductive program. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2006;23:329–332. doi: 10.1007/s10815-006-9032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin S.J., Franasiak J.M., Juneau C.R., Scott R.T. Live birth rate following embryo transfer is significantly influenced by the physician performing the transfer: data from 2707 euploid blastocyst transfers by 11 physicians. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:e25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karande V.C., Morris R., Chapman C., Rinehart J., Gleicher N. Impact of the “physician factor” on pregnancy rates in a large assisted reproductive technology program: do too many cooks spoil the broth? Fertil Steril. 1999;71:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toth T.L., Lee M.S., Bendikson K.A., Reindollar R.H. American Society for Reproductive Medicine Embryo Transfer Advisory Panel. Embryo transfer techniques: an American Society for Reproductive Medicine survey of current Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology practices. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McQueen D.B., Robins J.C., Yeh C., Zhang J.X., Feinberg E.C. Embryo transfer training in fellowship: national and institutional data. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:1006–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brezina P.R., Yates M.M., Wallach E.E., Garcia J.E., Kolp L.A., Zacur H.A. Fellowship training in embryo transfer: the Johns Hopkins experience. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:S284. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittenberger M.D., Catherino W.H., Armstrong A.Y. Role of embryo transfer in fellowship training. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:1014–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penzias A., Bendikson K., Butts S., Coutifaris C., Falcone T., Fossum G., et al. ASRM standard embryo transfer protocol template: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:897–900. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziv A., Wolpe P.R., Small S.D., Glick S. Simulation-based medical education: an ethical imperative. Acad. Med. 2003;78:783–788. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deering S., Auguste T., Lockrow E. Obstetric simulation for medical student, resident, and fellow education. Semin. Perinatol. 2013;37:143–145. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks E.H., Chudnoff S., Karmin I., Wang C., Pardanani S. Does a surgical simulator improve resident operative performance of laparoscopic tubal ligation? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:541.e1–541.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Issenberg S.B., McGaghie W.C., Petrusa E.R., Lee Gordon D., Scalese R.J. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27:10–28. doi: 10.1080/01421590500046924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayton J.D., Groves A.M., Glickstein J.S., Flynn P.A. Effectiveness of echocardiography simulation training for paediatric cardiology fellows in CHD. Cardiol Young. 2018;28:611–615. doi: 10.1017/S104795111700275X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Ziegler D., De Ziegler N., Sean S., Bajouh O., Meldrum D.R. Training in reproductive endocrinology and infertility and assisted reproductive technologies: options and worldwide needs. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López M.J., García D., Rodríguez A., Colodrón M., Vassena R., Vernaeve V. Individualized embryo transfer training: Timing and performance. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1432–1437. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heitmann R.J., Hill M.J., Csokmay J.M., Pilgrim J., DeCherney A.H., Deering S. Embryo transfer simulation improves pregnancy rates and decreases time to proficiency in reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:1166–1172.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramaiah S.D., Ray K.A., Reindollar R.H. Simulation training for embryo transfer: findings from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Embryo Transfer Certificate Course. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barsky M., Valdes C.T., Gibbons W.E., Schutt A.K. Fellow confidence assessment after completion of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine embryo transfer simulation certificate course. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:e373–e374. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah D.K., Missmer S.A., Correia K.F.B., Racowsky C., Ginsburg E. Efficacy of intrauterine inseminations as a training modality for performing embryo transfer in reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellowship programs. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Total time to complete embryo transfer for A) Case A, B) Case B, and C) Case C)