Abstract

Lycorine (Lyc) and its hydrochloride (Lyc∙HCl) as effective drugs can fight against many diseases including novel coronavirus (COVID-19) based on their antiviral and antitumor mechanism. Beta-cyclodextrin (β-CD) is considered a promising carrier in improving its efficacy while minimizing cytotoxicity due to the good spatial compatibility with Lyc. However, the detailed mechanism of inclusion interaction still remains to be further evaluated. In this paper, six inclusion complexes based on β-CDs, Lyc and Lyc∙HCl were processed through ultrasound in the mixed solvent of ethanol and water, and their inclusion behavior was characterized after lyophilization. It was found that the inclusion complexes based on sulfobutyl-beta-cyclodextrin (SBE-β-CD) and Lyc∙HCl had the best encapsulation effect among prepared inclusion complexes, which may be attributed to the electrostatic interaction between sulfonic group of SBE-β-CD and quaternary amino group of Lyc∙HCl. Moreover, the complexes based on SBE-β-CD displayed pH-sensitive drug release property, good solubilization, stability and blood compatibility, indicating their potential as suitable drug carriers for Lyc and Lyc∙HCl.

Keywords: Beta-cyclodextrins, Lycorine, Lycorine hydrochloride, Inclusion behavior, Electrostatic interaction

1. Introduction

Amaryllidaceae alkaloids with diverse skeleton structures were mainly divided into 17 types. Lycorine (Lyc) with isoquinoline structure was the most typical amaryllidaceae alkaloids, which was highly-contained in Lycoris radiata [1]. Lyc was firstly isolated from the roots of safflower in 1897 and its hydrochloride (Lyc∙HCl) was discovered in 1976. They had been developed into effective drugs against many diseases based on their revealed antitumor and antivirus mechanisms [2]. Recently, it had been verified that Lyc can induce apoptosis of liver cancer [3] and oral cancer [4] cells through mitochondria mediated apoptosis pathway. It can also lead to the apoptosis of oral cancer [4] cells and cervical cancer [5] cells through regulating the Janus Kinase (JAK) signal path, and the apoptosis of colorectal cancer [6], [7] cells through regulating the agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase (ATK) signal path. In addition, Lyc can improve the function of diabetic patients’ peripheral nerve by activating adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signal path and inhibiting the expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP9) [8]. It can also forbid proliferation and promote apoptosis of renal carcinoma [9] cells through inducing oxidative stress mediated ferroptosis. Remarkably, Lyc could be used as a suitable candidate to target RNA replication enzymes within COVID-19 [10]. Besides, Anoop et al. found that Lyc∙HCl can restrain the activity of COVID-19 protease (Mpro) since the binding process of Mpro with Cys145 residue at the active site was blocked [11]. Therefore, it was expected that Lyc and Lyc∙HCl with unique isoquinoline structure could address the problem of vaccine resistance and may be developed into broad-spectrum anti-coronavirus drugs.

Intelligent drug delivery systems (DDS) can deliver appropriate dose of drugs to the exact location of lesion at the right time, thus minimizing their toxic and side effects while improving drug efficacy [12]. Currently, few anti-tumor DDS for Lyc had been exploited to improve its pharmacokinetics and bioavailability. Guo et al. [13] prepared mannosylated lipid nano-emulsion based on the complex of Lyc and oleic acid, which could realize the targeted delivery of Lyc to lung cancer cells. Although it had a high drug loading level of more than 80%, the system could not achieve sustained release to enhance the accumulation of Lyc in the cytoplasm following endocytosis. Liu et al. [14] synthesized mesoporous silica labeled with polyethylene glycol, which can be used as DDS for Lyc to target human prostate cancer cells. It can achieve pH-independent release of Lyc, but the drug loading level was only 3.57%. Recently, Shao et al. [15] prepared fluorescent carbon dots using the residue of mulberry leaf, and then loaded Lyc for both intracellular imaging and drug delivery. However, the Lyc loaded was unstable since the interaction between Lyc and carbon dots was dominated by physical adsorption. Additionally, the Lyc adsorbed outside the surface of carbon dots had potential side-effects on normal cells. Therefore, it was urgent to develop novel efficient DDS for Lyc and Lyc∙HCl to overcome these shortcomings, which can maximize medicinal value while minimize toxic side effects of Lyc and Lyc∙HCl.

Macrocyclic hosts beta-cyclodextrins (β-CDs) had become one of the important building block candidates in the fabrication of smart self-assembled nanomaterials [16], [17], [18]. During the inclusion processes, few distortions occurred in β-CDs [19]. Based on dynamic activity of the hydrophobic cavity and the reversible host–guest inclusion interactions, internal or external stimuli can trigger release of encapsulated drugs [20], [21], [22]. Generally, the non-covalent intermolecular interactions in the reversible encapsulation of the host β-CDs and the guest drugs mainly included van der Waals force, hydrogen bond, hydrophobic interaction, electrostatic interaction and π-π interaction [23]. The basic enthalpy driving force of hydrophobic interaction was that the guest molecules can replace the high-energy water in the hole of β-CDs [24]. As reported previously, the electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged β-CDs and guest molecules can attribute to effective drug encapsulation and aggregation of assemblies [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. Liu et al. assembled negative charged supramolecular nanoparticle based on sulfobutyl-beta-cyclodextrin (SBE-β-CD) showed good encapsulation efficiency and pH-responsive release property towards cationic berberine [30]. It was further demonstrated that native β-CD was spatially compatible with Lyc and their complex exhibited higher cytotoxicity than free Lyc [31]. Recently, the negative charged sulfonated CDs had been revealed broad-spectrum antiviral capability with the nature of the sulfonated linkers [32], mimicking the highly conserved target of viral attachment ligands (VALs), heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) [33]. Therefore, SBE-β-CD with negative sulfobutyl substituents was supposed to have favorable encapsulation effect for Lyc/Lyc∙HCl with positive nitrogen heterocycle.

In this work, the inclusion complexes based on β-CDs (native β-CD, netural hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) and negative charged SBE-β-CD) and Lyc/Lyc∙HCl were prepared through simple freeze-drying method and characterized by fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrophotometry, thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry (TG-DSC), scanning electron microscope (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Their inclusion behavior was evaluated by classical Job’s plot assay and phase solubility study using ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometry. In addition, the popular calculation of molecular docking simulation was employed to further investigate their inclusion interactions. As expected, SBE-β-CD had the best encapsulation effect for Lyc and Lyc∙HCl. The inclusion complexes based on SBE-β-CD also appeared pH-sensitive drug release and good blood compatibility in vitro. Combining antiviral capability of sulfonated linkers, SBE-β-CD will be promising anti-viral and anti-tumor DDS for Lyc/Lyc∙HCl.

2. Experimental sections

2.1. Materials

Lyc was purchased from Chengdu Herbpurify Co., Ltd. and Lyc∙HCl was purchased from Shanghai Xianding Biotechnology Co., Ltd. β-CD, HP-β-CD and SBE-β-CD were shopped from Tianjin Sciens Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Sodium chloride (NaCl) was bought from Tianjin Jiangtian Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. and ethyl alcohol (C2H5OH) was bought from Tianjin Chemart Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. All reagents were analytically pure and ultrapure water (UPW) was used in all experiments.

2.2. Preparation of six inclusion complexes and physical mixtures

All inclusion complexes were prepared by freeze-drying method. Lyc and Lyc∙HCl were dissolved in ethanol (1 mg/mL, 15 mL) and β-CDs’ aqueous (15 mL) was added at the molar ratio of 1:1. The solution was turbid during mixing and was treated with ultrasound for 1 h. When reaching inclusion balance, the solution turned to clear. Then, it was lyophilized for 2 days and the white products were obtained.

All physical mixtures of corresponding inclusion complexes were prepared by mechanically mixing. Similarly, the molar ratio of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl to β-CDs was 1:1.

2.3. Evaluation of inclusion behavior

2.3.1. Stoichiometry by Job’s plot assay

The inclusion ratio of all inclusion complexes was determined by the Job’s polt method (continuous variation method) to recognize the stoichiometry of the host–guest inclusion complexes [34]. The stoichiometric ratio (R) referred to the proportion of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl concentration to the total concentration varying from 0 to 1 [35]. To simplify the experimental process, ethanol and water were used as the mixed solvent at the volume ratio of 1:1, and the total volume was fixed at 2 mL. β-CDs (2.0, 1.8, 1.6, 1.4, 1.2, 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2, 0 mL) was added to Lyc or Lyc∙HCl (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, 2.0 mL) at the molar ratio of 1:1, and the controlled samples without β-CDs were prepared under the same conditions. All the above solutions were treated with ultrasound for 1 h and their absorbance at 289 nm were determined by an UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The concentration ratio corresponding to the maximum variation in absorption (Δ Abs) gave the R of these inclusion complexes (i.e., the R value of the guest Lyc or Lyc∙HCl and the host β-CDs was 2:1 if R = 0.66, 1:1 if R = 0.5, 1:2 if R = 0.33) [36].

2.3.2. Phase solubility study

Phase solubility study was carried out to determine the host–guest inclusion constant (K) of all complexes and to investigate the influence of β-CDs on the solubility of Lyc and Lyc∙HCl, according to the method of Higuchi and Connors with minor modifications [37]. Excessive amounts of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl were added into aqueous β-CDs solutions at different concentrations (0–8 mM). In order to ensure an overdose of drugs, the ratio of CLyc: Cβ-CDs or CLyc∙HCl: Cβ-CDs was controlled at 2:1. After reaching inclusion equilibrium through ultrasound for 1 h, the suspensions were filtered through 0.22 μm membrane filters to remove the undissolved Lyc or Lyc∙HCl. The concentration of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl in the filtrates was determined by measuring their absorbance at 298 nm using UV–Vis spectrophotometer [38], [39], [40]. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Finally, the stability of all inclusion complexes were evaluated by the K, which were calculated from the phase solubility diagram using the Eq. (1).

| (1) |

Here, k and b represented the slope and the intercept of phase solubility diagram, respectively.

2.4. Characterization

FT-IR spectroscopy of all complexes and physical mixtures were obtained on an AVATR360 supplied by Thermo Nicolet (USA). TG and DSC analysis were performed using STA 409 PC/PG (NETZSCH, Germany) under nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C·min−1 from room temperature to 600 °C. The morphology of inclusion complexes was assessed using the field emission scanning electron microscope (Apreo S LoVac, USA). XRD patterns were characterized by X-ray diffraction device (D8-Focus, Bruker, Germany) with Cu radiation at a range of 2 theta = 5-50°. 1D and 2D 1H NMR spectra were collected on Bruker ACF400 (400 MHz) supplied by Bruker Biospin (Fällanden, Switzerland). All experiments were carried out under the same conditions.

2.5. pH-sensitive release of drugs

The release property of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl was determined by the semi-permeable dialysis bag diffusion technique using UV–Vis spectroscopy [14], [41]. About 5 mg of SBE-β-CD@Lyc or SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl were dispersed in 5 mL of PBS (pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.5). Then, these release mediums were placed in semipermeable dialysis bags and immersed into 10 mL each of PBS at 37 °C with gentle shaking (150 rpm), respectively. At different time intervals (1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 h), 2 mL of the release mediums in different conditions were taken to measure the ultraviolet absorption of released Lyc or Lyc∙HCl at a wavelength of 289 nm. After taking measurement, an equal amount (2 mL) of fresh mediums were added to the corresponding semipermeable dialysis bags.

2.6. Assessment of blood compatibility in vitro

The hemolytic test was employed to assess the blood compatibility in vitro [42], [43]. Here, the purchased fresh anticoagulant pig blood replaced human blood, which was diluted with normal saline into a reserve solution for subsequent usage. Moreover, ultrapure water was served as the positive (100% hemolysis rate) control and normal saline was assigned as the negative controls (0% hemolysis rate), respectively [44]. Diluted anticoagulant pig blood (200 μL) and normal saline (10 mL) were sequentially added to each sample bottles in order to obtain red blood cell suspensions (2%). Subsequently, each inclusion complex (50 μL, 500 μg/mL) was added to the above red blood cell suspensions. These prepared samples were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h and centrifugated at 2000 r/min for 5 min in order to separate unruptured red blood cells. All separated supernatants were taken up to measure the optical density (OD) value of released hemoglobinat at 540 nm on a microplate reader [45]. The experiments were repeated three times. The hemolysis rate (%) was calculated based on the Eq. (2).

| (2) |

Here, nc represented the negative control, pc represented the positive control, and t represented the test group.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Characterization of inclusion complexes

3.1.1. FT-IR analysis

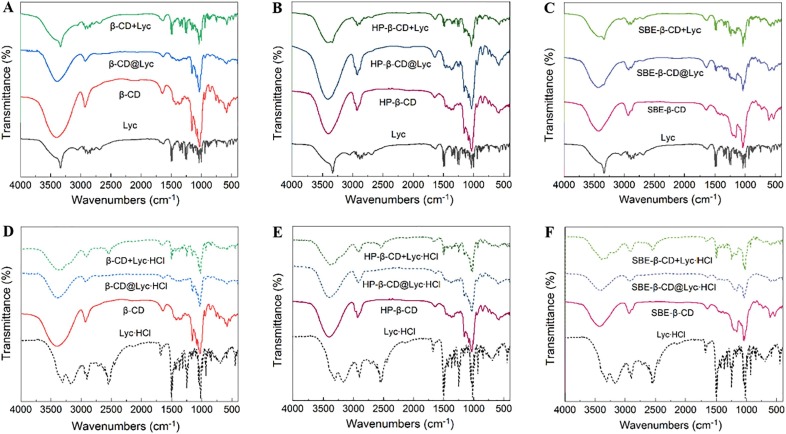

Infrared spectroscopy can provide a quick insight into the formation of inclusion complexes [46]. The FT-IR spectra of all inclusion complexes and their corresponding physical mixtures were shown in Fig. 1 . For three types of β-CDs, the peak at about 3750–3000 cm−1 was attributed to the characteristic of the —OH stretching vibration, which was large and wide due to the presence of intramolecular hydrogen bond, and the peak at about 2900 cm−1 was the stretching vibration peak of C—H [47]. The absorption at about 1600 cm−1 was the bending vibration peak of water molecules in the cavity of β-CDs [48] and the peaks of 1200–1000 cm−1 came from the C—O stretching vibration of glucose ring and the skeletal vibration of α-1,4 glycosidic linkage [49]. For Lyc or Lyc∙HCl, the peak located at about 3700–3000 cm−1 was attributed to the absorption of Lyc’s or Lyc∙HCl’s hydroxyl and amino groups. Take β-CD@Lyc as an example, the —OH stretching vibration peak of β-CD moved slightly to the lower wavenumber of 3350 cm−1 in β-CD@Lyc, which suggested that parts of intramolecular hydrogen bonds of β-CD may be broken ( Fig. 1 A). The absorption peaks of β-CD@Lyc at about 1200–1000 cm−1 was narrower than that of β-CD, attributing to the change of conformation in β-CD. In addition, the FT-IR spectrum of β-CD + Lyc was extremely similar to that of Lyc, indicating that the skeleton structure of Lyc remained unchanged in the physical mixture. All the characteristic absorption peaks of Lyc were weakened in β-CD@Lyc, which indicated that Lyc was included and the absorption peaks were covered by β-CD. The FT-IR spectra of HP-β-CD@Lyc, SBE-β-CD@Lyc, β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl ( Fig. 1 B, C, D, E, F) showed similar results to that of β-CD@Lyc ( Fig. 1 A). In brief, all inclusion complexes’ FT-IR spectra were distinct from the corresponding physical mixtures, indicating the formation of inclusion complexes based on β-CDs for Lyc and Lyc∙HCl.

Fig. 1.

The FT-IR spectra of (A) β-CD@Lyc (blue) compared with β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), β-CD (red), (B) HP-β-CD@Lyc (blue) compared with HP-β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), HP-β-CD (red), (C) SBE-β-CD@Lyc (blue) compared with SBE-β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), SBE-β-CD (red), (D) β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue) compared with β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), β-CD (red), (E) HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue) compared with HP-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), HP-β-CD (red), (F) SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue) compared with SBE-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), SBE-β-CD (red). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.1.2. TG-DSC analysis

The thermal properties of all inclusion complexes were analyzed by TG [50]. The results of mass changes of all inclusion complexes were different from β-CDs, Lyc, Lyc∙HCl and their corresponding physical mixtures, as presented in Fig. 2 . Take β-CD as an example, the weight loss of β-CD was 20% from 75 to 100 °C due to water molecules encapsulated in the cavity of β-CD. Meanwhile, the weight loss of β-CD@Lyc fell to 10% and that of β-CD@Lyc∙HCl fell to 5%, which indicated that partial water molecules in the cavity of β-CD were displaced by Lyc or Lyc∙HCl. Also, the maximum weight loss of Lyc and Lyc∙HCl was 50% and 40%, respectively. The maximum weight loss of HP-β-CD@Lyc and HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl decreased to 70% and 60%, and that of SBE-β-CD@Lyc and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl declined to 50% and 40%, respectively. The maximum weight loss of SBE-β-CD@Lyc and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl was closer to Lyc and Lyc∙HCl compared with that of HP-β-CD@Lyc and HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, which suggested that SBE-β-CD had stronger inclusion interaction for Lyc and Lyc∙HCl than that of HP-β-CD. In addition, the weight loss temperatures of β-CDs@Lyc can reach 300 °C (Fig. 2 A), which was higher than that of β-CDs@Lyc∙HCl (250 °C) as shown in Fig. 2 B. Therefore, the higher thermal stability of β-CDs@Lyc∙HCl than that of β-CDs@Lyc indicated by the greater temperature at which weight loss occurred [39].

Fig. 2.

The TG curves of (A) β-CDs@Lyc (β-CD@Lyc (purple, solid), HP-β-CD@Lyc (green, solid), SBE-β-CD@Lyc (pink, solid)) compared with β-CDs + Lyc (β-CD + Lyc (purple, break), HP-β-CD + Lyc (green, break), SBE-β-CD + Lyc (pink, break)), Lyc (black), β-CD (red), HP-β-CD(grown), SBE-β-CD (blue) and (B) β-CDs@Lyc∙HCl (β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue, solid), HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (green, solid), SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (pink, solid)) compared with β-CDs + Lyc∙HCl (β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (blue, break), HP-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green, break), SBE-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (pink, break)), Lyc∙HCl (black), β-CD (red), HP-β-CD(grown), SBE-β-CD (gray). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The heat involved in the exothermic and endothermic transitions were determined with DSC technique [51]. DSC curves of all inclusion complexes were shown in Fig. 3 . An endothermic peak at about 280 °C was observed in the DSC curve of Lyc, while an exothermic peak at about 225 °C appeared in the DSC curve of Lyc∙HCl. Three types of β-CDs had two endothermic peaks. β-CD presented a double splitting peak at about 320–330 °C. HP-β-CD had a sharp peak at about 310 °C and a wide peak at about 490 °C, while two peaks existed at about 270 °C and 360 °C in SBE-β-CD, respectively. Compared with Lyc, the endothermic temperature of inclusion complexes based on Lyc reduced by about 50 °C in β-CD@Lyc, 30 °C in HP-β-CD@Lyc and 20 °C in SBE-β-CD@Lyc (Fig. 3 A, 3B, 3C). While the endothermic temperature of inclusion complexes based on Lyc∙HCl slightly increased by about 20 °C in β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, 20 °C in HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl and 30 °C SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl compard with Lyc∙HCl (Fig. 3 D, E, F). Therefore, all inclusion complexes had higher decomposition temperatures than corresponding physical mixtures, indicating their good thermal stability.

Fig. 3.

The DSC curves of (A) β-CD@Lyc (red) compared with β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), β-CD (blue), (B) HP-β-CD@Lyc (red) compared with HP-β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), HP-β-CD (blue), (C) SBE-β-CD@Lyc (red) compared with SBE-β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), SBE-β-CD (blue), (D) β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (red) compared with β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), β-CD (blue), (E) HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (red) compared with HP-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), HP-β-CD (blue), (F) SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (red) compared with SBE-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), SBE-β-CD (blue). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.1.3. SEM analysis

The surface morphologies of all inclusion complexes were qualitatively observed to determine the influence of inclusion behavior on the microstructure and surface morphology changes of β-CDs after encapsulating Lyc or Lyc∙HCl [52]. β-CD had a regular rectangular sheet structure (Fig. 4 A). A spherical shell structure with holes existed in HP-β-CD (Fig. 4 B). SBE-β-CD exhibited the doping state of smooth and defective spherical shells (Fig. 4 C). Meanwhile, β-CD@Lyc had a rhomboidal structure (Fig. 4 D), while β-CD@Lyc∙HCl was fragment mixed with some irregular sheets (Fig. 4 G). HP-β-CD@Lyc and HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl appeared in the form of large lamellar and membrane structures, respectively (Fig. 4 E, 4H). Both SBE-β-CD@Lyc and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl showed massive structures with distinct defects (Fig. 4 F, 4I). Therefore, the morphology of original β-CDs completely disappeared in all resulting amorphous inclusion complexes, which suggested the formation of these complexes based on the host–guest inclusion interactions [53].

Fig. 4.

The SEM images of (A) β-CDs, (B) HP-β-CD, (C) SBE-β-CD, (D) β-CD@Lyc, (E) HP-β-CD@Lyc, (F) SBE-β-CD@Lyc, (G) β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, (H) HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, (I) SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl.

3.1.4. XRD analysis

XRD is a reliable technique in identifying the formation of new crystalline phase in inclusion complexes based on β-CDs. As demonstrated in Fig. 5 , the XRD spectrum of Lyc, Lyc∙HCl and β-CD presented a series of sharp diffraction peaks suggesting their crystalline nature, while no crystalline peak was observed in the XRD spectrum of HP-β-CD and SBE-β-CD suggesting their amorphous nature [54]. The peaks corresponding to Lyc or Lyc∙HCl were observed in the corresponding physical mixtures (β-CD + Lyc (A, green), HP-β-CD + Lyc (B, green), SBE-β-CD + Lyc (C, green), β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (D, green), HP-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (E, green), SBE-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (F, green)). In contrast, no sharp peaks were observed in the XRD spectrum of β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (D, blue), HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (E, blue) and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (F, blue), and peaks with less intensity were observed in the XRD spectrum of β-CD@Lyc (A, blue), HP-β-CD@Lyc (B, blue) and SBE-β-CD@Lyc (C, blue). The crystalline nature of Lyc∙HCl or Lyc disappeared or weakened in the inclusion complexes but preserved in the corresponding physical mixtures, indicating the different degree of inclusion interactions in β-CDs@Lyc∙HCl and β-CDs@Lyc.

Fig. 5.

The XRD spectra of (A) β-CD@Lyc (blue) compared with β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), β-CD (red), (B) HP-β-CD@Lyc (blue) compared with HP-β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), HP-β-CD (red), (C) SBE-β-CD@Lyc (blue) compared with SBE-β-CD + Lyc (green), Lyc (black), SBE-β-CD (red), (D) β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue) compared with β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), β-CD (red), (E) HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue) compared with HP-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), HP-β-CD (red), (F) SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue) compared with SBE-β-CD + Lyc∙HCl (green), Lyc∙HCl (black), SBE-β-CD (red). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Evaluation of inclusion behavior

3.2.1. Determination of stoichiometric ratio

The stoichiometric ratio (R) of all inclusion complexes was measured using the Job’s plot method [55], [56]. As displayed in Fig. 6 , the value of △Abs increased and then decreased with increasing R values showing a parabolic trend and the peak values for each plot appeared at 0.5, suggesting that the R values of all inclusion complexes were 1:1 [57]. In addition, the enhancement effect of ultraviolet absorption for all inclusion complexes was ranked in the order of SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl > HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl > β-CD@Lyc∙HCl > SBE-β-CD@Lyc > HP-β-CD@Lyc > β-CD@Lyc. Therefore, SBE-β-CD had the best solubilization effect on Lyc∙HCl, which indicated that SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl had the maximum solubility among all inclusion complexes. This may be due to the electrostatic interaction between the quaternary amino group of Lyc∙HCl and the sulfonic group of SBE-β-CD.

Fig. 6.

The Job’s working curve of β-CD@Lyc (gray), β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (black), HP-β-CD@Lyc (purple), HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (blue), SBE-β-CD@Lyc (pink) and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (red). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2.2. Determination of inclusion constant

The inclusion constant (K) and thermodynamic parameter () of all inclusion complexes were determined by the phase solubility method using UV–Vis spectrophotometer [38]. All phase solubility curves of Lyc ( Fig. 7 A) and Lyc∙HCl ( Fig. 7 B) belonged to the typical AL type, and the aqueous solubility of Lyc and Lyc∙HCl increased linearly with the increasing concentration of β-CDs. This linear host–guest correlation indicated that the R values of all inclusion complexes were 1:1 according to Higuchi and Connors’s theory [37]. The order of inclusion stability of all inclusion complexes corresponding to the K values was SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl > SBE-β-CD@Lyc > β-CD@Lyc∙HCl > HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl > β-CD@Lyc > HP-β-CD@Lyc. It was proved that the inclusion complexes based on SBE-β-CD was the most stable among the three β-CDs, and the inclusion stability of β-CDs for Lyc∙HCl was stronger than that of Lyc. Unexpectedly, β-CD had better inclusion stability than that of HP-β-CD, which may be attributed to the steric hindrance coming from hydroxypropyl substituents. Also, the spontaneity of the complexing process was demonstrated by negative ΔG values [39]. The ΔG of the complexation based on β-CDs with Lyc∙HCl was 3.72–4.88 kJ/mol lower than that with Lyc, as shown in Table 1 . Also, the complexation of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl with SBE-β-CD was lower than that with HP-β-CD and β-CD. The more negative ΔG suggested that SBE-β-CD could provide a more favorable environment for Lyc or Lyc∙HCl [40].

Fig. 7.

The phase solubility curves of β-CD@Lyc (A, green), HP-β-CD@Lyc (A, blue), SBE-β-CD@Lyc (A, red), β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (B, green), HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (B, blue) and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (B, red). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

The slope (k) and intercept (b) as well as the calculated binding constant (K) and thermodynamic parameter (△ G) of β-CD@Lyc, β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, HP-β-CD@Lyc, HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, SBE-β-CD@Lyc and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl.

| Inclusion complexes | k | b | K (M−1) | △ G (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBE-β-CD@Lyc | 0.04627 | 0.0293 | 1655.80 | −18.36 |

| HP-β-CD@Lyc | 0.04159 | 0.05936 | 731.04 | −16.34 |

| β-CD@Lyc | 0.03833 | 0.0519 | 767.97 | −16.46 |

| SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl | 0.04932 | 0.00428 | 11911.24 | –23.24 |

| HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl | 0.04827 | 0.01617 | 3330.73 | −20.06 |

| β-CD@Lyc∙HCl | 0.04539 | 0.01252 | 3856.23 | −20.42 |

3.2.3. Determination of inclusion modes

The possible interactions and inclusion modes of all inclusion complexes were investigated by 1D and 2D 1H NMR [58]. To begin with, the chemical shifts of all inclusion complexes, β-CDs, Lyc and Lyc∙HCl were observed by 1D 1H NMR. As showed in Fig. 8 and Fig. S1, the 3-H inside SBE-β-CD/HP-β-CD/β-CD moved from 3.80/3.96/3.90 ppm to the lower field of 3.85/3.99/3.93 ppm (△δ = 0.05/0.03/0.03 ppm), and the 5-H shifted from 3.65/3.87/3.81 ppm to 3.79/3.90/3.85 ppm (△δ = 0.06/0.03/0.04 ppm) for the inclusion complexes based on Lyc∙HCl. While the 3-H inside SBE-β-CD/HP-β-CD/β-CD moved from 3.80/3.96/3.90 ppm to the higher field of 3.79/3.95/3.88 ppm (△δ = 0.01/0.01/0.02 ppm), and the 5-H shifted from 3.65/3.87/3.81 ppm to 3.64/3.85/3.80 ppm (△δ = 0.01/0.02/0.01 ppm) for the inclusion complexes based on Lyc. The changes in chemical shifts (△δ) of β-CDs@Lyc∙HCl were greater than that of β-CDs@Lyc, illustrating that the inclusion interaction between β-CDs and Lyc∙HCl was stronger than that of Lyc. In addition, the 7-H in Lyc∙HCl moved from 6.86 ppm to 6.85/6.857/6.88 ppm (△δ = -0.02/-0.02/0.02 ppm), and the 12-H shifted from 2.88 ppm to 2.85/2.87/2.92 ppm (△δ = -0.03/0.01/0.04 ppm) after encapsulating by SBE-β-CD/HP-β-CD/β-CD. While the 7-H in Lyc moved from 6.76 ppm to 6.75/6.77/6.77 ppm (△δ = -0.01/0.01/0.01 ppm), and the 12-H shifted from 2.77 ppm to 2.75/2.78/2.80 ppm (△δ = -0.02/0.01/0.03 ppm), as shown in Table S2. All these chemical shifts of inclusion complexes were probably caused by the inclusion interactions between the hydrophobic cavities of β-CDs with Lyc and Lyc∙HCl.

Fig. 8.

The 1D 1H NMR spectrum of (A) SBE-β-CD@Lyc (red) compared with Lyc (blue), SBE-β-CD (green) and (B) SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (red) compared with Lyc∙HCl (blue), SBE-β-CD (green). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Then, the binding interactions and further encapsulation mode were predicted by 2D 1H NMR [59]. As illustrated in Fig. 9 , the spatial interactions between SBE-β-CD and drugs were slightly stronger than that of β-CD and HP-β-CD. Also, compared with β-CDs and Lyc, there existed more significant spatial correlations between β-CDs and Lyc∙HCl, as displayed in Fig. S3. Take SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl as an example (Fig. 9 A), 10, 7, 11, 12-H and dioxane’s hydrogen of Lyc∙HCl had strong spatial correlations with the 3, 5-H of SBE-β-CD (Fig. 9 B, 9D). Their also existed spatial correlation between 10b, 4a-H of Lyc∙HCl and 5-H of SBE-β-CD which indicated that all the ring structures of A, B, C, D and dioxane in Lyc∙HCl may be encapsulated in the cavity of SBE-β-CD (Fig. 9 C). However, only partial structures of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl had week spatial interactions with β-CDs in β-CD@Lyc, β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, HP-β-CD@Lyc, HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl and SBE-β-CD@Lyc (Figure S3 ). Thus, only the ring of C in Lyc and the ring of B, C in Lyc∙HCl may be encapsulated in the cavity of β-CD, and the ring of A, B, C of Lyc and the ring of C, D of Lyc∙HCl may be encapsulated in the cavity of HP-β-CD. While all the ring of Lyc may also be encapsulated in the cavity of SBE-β-CD, but the spatial correlations were weaker than that of Lyc∙HCl. In brief, it was proved that the inclusion effect of SBE-β-CD on Lyc∙HCl was indeed the best.

Fig. 9.

The 2D 1H NMR spectrum of (A) SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl and (B, C, D) partial enlarged details of (A).

Moreover, computational molecular docking studies were carried out to obtain further insight into the binding mode of SBE-β-CD to Lyc∙HCl, revealing an orientational preference of Lyc∙HCl in SBE-β-CD cavity (Fig. 10 A). Based on Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) and semi-flexible docking method, the simulation was carried out using AutoDock software and the binding free energy was used as the basis to evaluate the docking results [60]. It was turned out that their existed electrostatic interaction and three hydrogen bonds in SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl. The three hydrogen bonds were oriented in dioxane of Lyc∙HCl and 6-OH of SBE-β-CD, hydroxyl of Lyc∙HCl and 1, 4-glycoside of SBE-β-CD, quaternary amino of Lyc∙HCl and 1, 4-glycoside of SBE-β-CD. Meanwhile, the intermolecular spatial interactions between the characteristic hydrogen of Lyc∙HCl and the 3, 5-H in the cavity of SBE-β-CD were consistent with the results of 2D 1H NMR (Fig. 10 B). Thus, Lyc∙HCl was inserted deep into SBE-β-CD from the secondary surface, and the whole structure of Lyc∙HCl was completely encapsulated in SBE-β-CD. The possible inclusion modes of other inclusion complexes were described in Fig. S3.

Fig. 10.

(A) The molecular docking model and (B) the predicted inclusion mode of SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl.

3.3. pH-sensitive release of drugs

In this study, UV–Vis spectroscopy was used to determine the release property of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl with a semi-permeable dialysis bag diffusion technique [14], [48]. The cumulative release profiles of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl from SBE-β-CD@Lyc or SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl in PBS of different pH values (7.4, 6.5 and 5.5) were shown in Fig. 11 . For all tested pH values, the release of Lyc or Lyc∙HCl occurred quickly for the initial period of 4 h and gradually reached release balance after this time interval. The maximum cumulative release rate of Lyc and Lyc∙HCl at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.5 was determined to be 44.4% and 47.6%, 58.2% and 69.9%, 65.7% and 71.1%, respectively. Therefore, the release rate at pH 5.5 and 6.5 was faster than that of pH 7.4, indicating the cumulative release of Lyc and Lyc∙HCl was acid-dependent. As shown in Fig. 4 S, the increasing release of Lyc and Lyc∙HCl with the pH decreasing from 7.4 to 5.5 was attributed to the strengthened electrostatic repulsion between protonated sulfonic groups and the positively charged amino groups.

Fig. 11.

The release profile of Lyc from SBE-β-CD@Lyc in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at pH ∼ 7.4 (green), pH ∼ 6.5 (blue), pH ∼ 5.5 (red), and Lyc∙HCl from SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at pH ∼ 7.4 (purple), pH ∼ 6.5 (pink), pH ∼ 5.5 (black). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

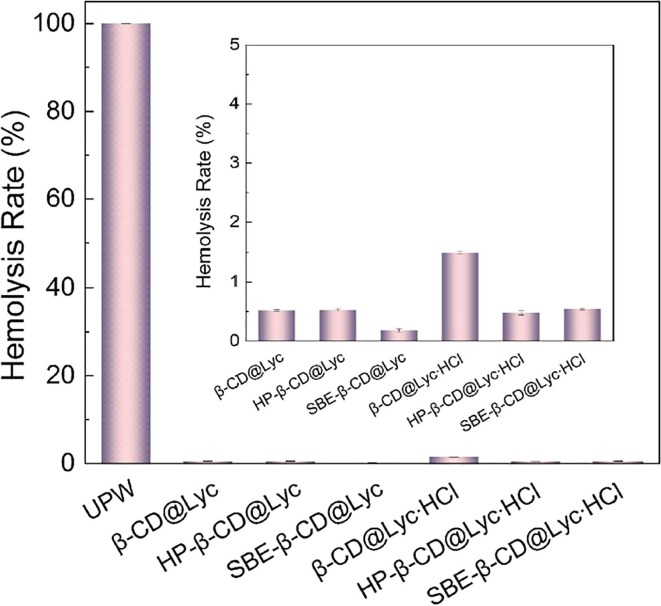

3.4. Assessment of blood compatibility in vitro

The hemolysis test in vitro was conducted to evaluate the blood compatibility of all inclusion complexes using red cells of anticoagulant pig blood, as shown in Fig. 12 . Compared to the positive control of ultrapure water, all inclusion complexes showed excellent blood compatibility. After quantitative calculations, the hemolysis rate of all inclusion complexes was less than 5%, which indicated that they had good blood compatibility and qualified to be non-hemolytic materials according to national biological safety [44], [45]. Moreover, the hemolysis rate of SBE-β-CD@Lyc and SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl was nearly three times lower than that of β-CD@Lyc and β-CD@Lyc∙HCl (Table S3 ). The results suggested that the inclusion complexes based on SBE-β-CD had better blood compatibility than that of β-CD. Because the reabsorption of SBE-β-CD was reduced and their urine excretion was faster than that of β-CD due to the presence of polar sulfonic groups. As a matter of fact, SBE-β-CD was mainly distributed in the extracellular fluid, and its elimination rate through urine was close to the filtration rate of glomerular [61].

Fig. 12.

The hemolysis rate of β-CD@Lyc, β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, HP-β-CD@Lyc, HP-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl, SBE-β-CD@Lyc, SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl and ultrapure water.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, six inclusion complexes based on β-CDs, Lyc and Lyc∙HCl were prepared by lyophilization. Their inclusion behavior was characterized by FT-IR, TG-DSC, SEM, XRD, 1H NMR and molecular docking. Results indicated that β-CDs with hydrophobic cavity had a solubilization effect on Lyc and Lyc∙HCl through host–guest inclusion interactions, and all inclusion complexes had good thermal stability. In addition, Job’s working curve and phase solubility methods were used to prove that the inclusion ratio of all inclusion complexes were 1:1. Compared with β-CD and HP-β-CD, the inclusion complexes based on SBE-β-CD had the best binding stability. Moreover, 1H NMR and molecular docking characterization further showed that the electrostatic interaction in SBE-β-CD@Lyc∙HCl induced their good encapsulation effect. Finally, the inclusion complexes based on SBE-β-CD appeared pH-sensitive drug release for Lyc and Lyc∙HCl in vitro, and the hemolysis rate was less than 5%, indicating their potential in assembling anti-tumor DDS responding to acidic tumor microenvironment, and their great blood compatibility. In a word, this work can provide support for the future construction of novel DDS based on β-CDs with Lyc and its Lyc∙HCl.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xinyue Sun: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Yuan Li: Software, Formal analysis. Haiyang Yu: Resources, Supervision. Xiaoning Jin: Investigation. Xiaofei Ma: Validation. Yue Cheng: Supervision, Visualization. Yuping Wei: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Yong Wang: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: [Yong Wang reports financial support was provided by the National Key R&D Program of China. Yong Wang reports financial support was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Yuping Wei reports financial support was provided by Tianjin National Science Foundation. Yuping Wei reports financial support was provided by the Seed Foundation of Tianjin University.].

Acknowledgments

This work was financially funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1905500) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21922409 and 21976131). In addition, this work was supported by Tianjin National Science Foundation (20JCYBJC01440) and the Seed Foundation of Tianjin University (2022XYY-0009).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.121658.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Berkov S., Torras-Claveria L., Viladomat F., Suárez S., Bastida J. GC-MS of some lycorine-type amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Mass Spectrom. 2021;56(3):e4704. doi: 10.1002/jms.4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasca-Silva C.A., Gomes J.V.D., Gomes-Copeland K.K.P., Fonseca-Bazzo Y.M., Fagg C.W., Silveira D. Recent updates on Crinum latifolium L. (Amaryllidaceae): a review of ethnobotanical, phytochemical, and biological properties. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022;146:162–173. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z., Ye X.M., Yuan K.R., Liu W., Liu K., Li Y.Y., Huang C.B., Yu Z.Q., Wu D.D. Lycorine nanoparticles induce apoptosis through mitochondrial intrinsic pathway and inhibit migration and invasion in HepG2 cells. IEEE T. NanoBiosci. 2021 doi: 10.1109/TNB.2021.3132104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li M.H., Liao X., Li C., Wang T.T., Sun Y.S., Yang K., Jiang P.W., Shi S.T., Zhang W.X., Zhang K., Li C., Yang P. Lycorine hydrochloride induces reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis via the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and the JNK signaling pathway in the oral squamous cell carcinoma HSC-3 cell line. Oncol. Lett. 2021;21(3):263. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shang H., Jang X.N., Shi L.Y., Ma Y.F. Lycorine inhibits cell proliferation and induced oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis via regulation of the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway in HT-3 cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxic. 2021;35(10):e22882. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang P., Yuan X.H., Yu T.T., Huang H.K., Yang C.M., Zhang L.L., Yang S.D., Luo X.J., Luo J.Y. Lycorine inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and primarily exerts in vitro cytostatic effects in human colorectal cancer via activating the ROS/p38 and AKT signaling pathways. Oncol. Lett. 2021;45(4):19. doi: 10.3892/or.2021.7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao L., Feng Y.L., Ge C.C., Xu X.J., Wang S.Z., Li X.N., Zhang K.M., Wang C.J., Dai F.J., Xie S.Q. Identification of molecular anti-metastasis mechanisms of lycorine in colorectal cancer by RNA-seq analysis. Phytomedicine. 2021;85 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan Q.Q., Zhang X., Wei W.D., Zhao J.L., Wu Y.H., Zhao S., Zhu L., Wang P.R., Hao J. Lycorine improves peripheral nerve function by promoting Schwann cell autophagy via AMPK pathway activation and MMP9 downregulation in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Pharmacol. Res. 2022;175 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du Y., Zhao H.C., Zhu H.C., Jin Y., Wang L. Ferroptosis is involved in the anti-tumor effect of lycorine in renal cell carcinoma cells. Oncol. Lett. 2021;22(5):781. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.13042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan S., Banwell M.G., Ye W.C., Lan P., White L.V. The inhibition of RNA viruses by amaryllidaceae alkaloids: opportunities for the development of broad-spectrum anti-coronavirus drugs. Chemistry. 2022;17(4):e202101215. doi: 10.1002/asia.202101215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayanan A., Narwal M., Majowicz S.A., Varricchio C., Toner S.A., Ballatore C., Brancale A., Murakami K.S., Jose J. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors targeting Mpro and PLpro using in-cell-protease assay. Commun. Biol. 2022;5(169):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao X.K., Mu J., Zeng L.L., Lin J., Nie Z.H., Jiang X.Q., Huang P. Stimuli-responsive cyclodextrin-based nanoplatforms for cancer treatment and theranostics. Mater. Horiz. 2019;6:846. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Y.M., Liu X., Sun X., Zhang Q., Gong T., Zhang Z.R. Mannosylated lipid nano-emulsions loaded with lycorine-oleic acid ionic complex for tumor cell-specific delivery. Theranostics. 2012;2(11):1104–1114. doi: 10.7150/thno.4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X.N., Kang J.J., Wang H., Huang T. Construction of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled MSNs/PEG/Lycorine/Antibody as drug carrier for targeting prostate cancer cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018;18(7):4471–4477. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2018.15292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao Y.Y., Zhu C.Y., Fu Z.F., Lin K. Green synthesis of multifunctional fluorescent carbon dots from mulberry leaves (Morus alba L.) residues for simultaneous intracellular imaging and drug delivery. J. Nanopart. Res. 2020;22(8):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Y., Aimetti A.A., Langer R., Gu Z. Bioresponsive materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017:16075. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu H.T.Z., Shangguan L.Q., Shi B.B., Yu G.C., Huang F.H. Recent progress in macrocyclic amphiphiles and macrocyclic host-based supra-amphiphiles. Mater. Chem. Front. 2018;2:2152–2174. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oo A., Kerdpol K., Mahalapbutr P., Rungrotmongkol T. Molecular encapsulation of emodin with various β-cyclodextrin derivatives: a computational study. J. Mol. Liq. 2022;347(1) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cova T.F., Milne B.F., Pais A.A.C.C. Host flexibility and space filling in supramolecular complexation of cyclodextrins: a free-energy-oriented approach. Carbohyd. Polym. 2019;205:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahiro K., Tada-aki Y., Tomoki O. Stimuli-responsive supramolecular assemblies constructed from Pillar[n]arenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018;51(7):1656–1666. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian B.R., Liu Y.M., Liu J.Y. Smart stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems based on cyclodextrin: A review. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021;251 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z.X., Lin W.J., Liu Y. Macrocyclic supramolecular assemblies based on hyaluronic acid and their biological applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022:2c00462. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma X., Zhao Y.L. Biomedical applications of supramolecular systems based on host-guest interactions. Chem. Rev. 2015;115(15):7794–7839. doi: 10.1021/cr500392w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biedermann F., Nau W.M., Schneider H.-J. The hydrophobic effect revisited-studies with supramolecular complexes imply high-energy water as a noncovalent driving force. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53(42):11158–11171. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai X., Zhang B., Zhou W., Liu Y. High-efficiency synergistic effect of supramolecular sanoparticles based on cyclodextrin prodrug on cancer therapy. Biomacromolecules. 2020;21:4998–5007. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.0c01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan X., Chen Y., Wu X., Li P., Liu Y. Enzyme-responsive sulfatocyclodextrin/prodrug supramolecular assembly for controlled release of anti-cancer drug chlorambucil. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:953–956. doi: 10.1039/c8cc09047e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu Q., Zhang Y.M., Liu Y.H., Xu X., Liu Y. Magnetism and photo dual-controlled supramolecular assembly for suppression of tumor invasion and metastasis. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaat2297. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J.J., Chen Y., Yu J., Cheng N., Liu Y. A supramolecular artificial light-harvesting system with an ultrahigh antenna effect. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1701905. doi: 10.1002/adma.201701905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z.X., Liu Y. Multicharged cyclodextrin supramolecular assemblies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022;51:4786–4827. doi: 10.1039/d1cs00821h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X.M., Chen Y., Hou X.F., Wu X., Gu B.H., Liu Y. Sulfonato-β-cyclodextrin mediated supramolecular nanoparticle for controlled release of berberine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:24987–24992. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b08651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu D.D., Guo Y.F., Zhang J.Q., Yang Z.K., Lia X., Yang B., Yang R. Inclusion of lycorine with natural cyclodextrins (α-, β- and γ-CD): experimental and in vitro evaluation. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1130(15):669–676. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones S.T., Cagno Va, Janeček M., Ortiz D., Gasilova N., Piret J., Gasbarri M., Constant D.A., Han Y., Vuković L., Král P., Kaiser L., Huang S., Constant S., Kirkegaard K., Boivin G., Stellacci F., Tapparel C. Modified cyclodextrins as broad-spectrum antivirals. Sci. Adv. 2020;6(15):aax9318. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax9318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cagno V., Andreozzi P., Alicarnasso M.D’., Silva P.J., Mueller M., Galloux M., Go-c R.L., Jones S.T., Vallino M., Hodek J., Weber J., Sen S., Janeček E.-R., Bekdemir A., Sanavio B., Martinelli C., Donalisio M., Welti M.-A.R., Eleouet J.-F., Han Y.X., Kaiser L., Vukovic L., Tapparel C., Král P., Krol S., Lembo D., Stellacci F. Broad-spectrum non-toxic antiviral nanoparticles with a virucidal inhibition mechanism. Nat. Mater. 2018;17:195–203. doi: 10.1038/nmat5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Job P. Formation and stability of inorganic complexes in solution. Ann. Chim. Phys. 1928;9:113–203. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renny J.S., Tomasevich L.L., Tallmadge E.H., Collum D.B. Method of continuous variations: applications of job plots to the study of molecular associations in organometallic chemistry. Angew. Chemie. Int. Ed. 2013;52:11998–12013. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha S., Roy A., Roy K., Roy M.N. Study to explore the mechanism to form inclusion complexes of β-cyclodextrin with vitamin molecules. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep35764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higuchi T., Connors K.A. Phase-solubility techniques. Adv. Anal. Chem. Instrum. 1965;4:117–212. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z.H., Li K., Teng M.L., Li M., Sui X.F., Liu B.Y., Tian B.C., Fu Q. Functionality-related characteristics of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin for the complexation. J. Mol. Liq. 2022;365 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oo A., Mahalapbutr P., Krusong K., Liangsakul P., Thanasansurapong S., Reutrakul V., Kuhakarn C., Maitarad P., Silsirivanit A., Wolschann P., Putthisen S., Kerdpol K., Rungrotmongkol T. Inclusion complexation of emodin with various β-cyclodextrin derivatives: Preparation, characterization, molecular docking, and anticancer activity. J. Mol. Liq. 2022;367 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J.Y., Zhang S.D., Zhao X.Y., Lu Y., Song M., Wu S.Z. Molecular simulation and experimental study on the inclusion of rutin with β-cyclodextrin and its derivative. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1254 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J.W., Guo Z.H., Xiong J.X., Wu D.T., Li S., Tao Y.X., Qin Y., Kong Y. Facile synthesis of chitosan-grafted beta-cyclodextrin for stimuli-responsive drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;125:941–947. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh D.K., Ray A.R. Graft copolymerization of 2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate onto chitosan films and their blood compatibility. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1994;53(8):1115–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu D.Q., Zhu J., Han H., Zhang J.Z., Wu F.F., Qin X.H., Yu J.Y. Synthesis and characterization of arginine-NIPAAm hybrid hydrogel as wound dressing: in vitro and in vivo study. Acta Biomater. 2018;65:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shafiei-Irannejad V., Rahimkhoei V., Molaparast M., Akbari A. Synthesis and characterization of novel hybrid nanomaterials based on β-cyclodextrine grafted halloysite nanotubes for delivery of doxorubicin to MCF-7 cell line. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1262 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J., Li N.N., Zhang D.M., Dong M.J., Wang C.H., Chen Y.S. Construction of cinnamic acids derived β-cyclodextrins and their emodin-based inclusions with enhanced water solubility, excellent antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Colloid. Surf. A. 2020;606(5) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X.Y., Su J.Q., Wang X.Y., Wang X.Y., Liu R.X., Fu X., Li Y., Xue J.J., Li X.L., Zhang R., Chu X.L. Preparation and properties of cyclodextrin inclusion complexes of hyperoside. Molecules. 2022;27(9):2761. doi: 10.3390/molecules27092761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dou Z., Chen C., Fu X. The effect of ultrasound irradiation on the physicochemical properties and α-glucosidase inhibitory effect of blackberry fruit polysaccharide. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;96:568–576. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song X., He G., Ruan H., Chen Q. Preparation and properties of octenyl succinic anhydride modified earlyIndica rice starch. Starch Stärke. 2006;58:109–117. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2006.B0800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miao M., Li R., Jiang B., Cui S.W., Zhang T., Jin Z. Structure and physicochemical properties of octenyl succinic esters of sugary maize soluble starch and waxy maize starch. Food Chem. 2014;151:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira A.M., Kaya A., Alves D., Fard N.A., Tolaymat I., Arafat B., Najlah M. Preparation and characterization of disulfiram and beta cyclodextrin inclusion complexes for potential application in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 via nebulization. Molecules. 2022;27(17):5600. doi: 10.3390/molecules27175600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Souza D.F.D.J., Dos Santos S.M.D., Julia D.N.F.R., Monti B.M., Baggio D.F., Hummig W., Araya E.I., Paula E.D., Chichorro J.G., Ferreira L.E.N. Antinociceptive effects of bupivacaine and its sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in orofacial pain. N.-S. Arch. Pharmacol. 2022;395:1405–1417. doi: 10.1007/s00210-022-02278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang P.X., Li S.S., Wang L.L., Yang H.Q., Yan J., Li H. Inclusion complexes of chlorzoxazone with β- and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin: Characterization, dissolution, and cytotoxicity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;131:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kapoor M.P., Moriwaki M., Minoura K., Timm D., Abe A., Kito K. Structural investigation of hesperetin-7-o-glucoside inclusion complex with β-Cyclodextrin: A spectroscopic assessment. Molecules. 2022;27(17):5395. doi: 10.3390/molecules27175395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao X., Qiu N., Ma Y.Y., Liu J.D., An L.Y., Zhang T., Li Z.Q., Han X., Chen L.J. Preparation, characterization and biological evaluation of β-cyclodextrin-biotin conjugate based podophyllotoxin complex. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021;160 doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2021.105745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H., Chang S.L., Chang T.R., You Y., Wang X.D., Wang L.W., Yuan X.F., Tan M.H., Wang P.D., Xu P.W., Gao W.B., Zhao Q.S., Zhao B. Inclusion complexes of cannabidiol with β-cyclodextrin and its derivative: physicochemical properties, water solubility, and antioxidant activity. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;334 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bensouiki S., Belaib F., Sindt M., Rup-Jacques S., Magri P., Ikhlef A., Meniai A.H. Synthesis of cyclodextrins-metronidazole inclusion complexes and incorporation of metronidazole-2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex in chitosan nanoparticles. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1247 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu P.W., Yuan X.F., Li H., Zhu Y., Zhao B. Preparation, characterization, and physicochemical property of the inclusion complexes of Cannabisin A with β-cyclodextrin and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1272 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khin S.Y., Soe H.M.S.H., Chansriniyom C., Pornputtapong N., Asasutjarit R., Loftsson T., Jansook P. Development of fenofibrate/randomly methylated β-cyclodextrin-loaded Eudragit® RL 100 nanoparticles for ocular delivery. Molecules. 2022;27(15):4755. doi: 10.3390/molecules27154755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lopalco A., Manni A., Keeley A., Haider S., Li W.L., Lopedota A., Altomare C.D., Denora N., Tuleu C. In vivo investigation of (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin-based formulation of spironolactone in aqueous solution for paediatric use. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(4):780. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14040780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun X.W., Zhu J.X., Liu C.Q., Wang D.F., Wang C.Y. Fabrication of fucoxanthin/2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex assisted by ultrasound procedure to enhance aqueous solubility, stability and antitumor effect of fucoxanthin. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2022;90 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang H., Xie X.X., Zhang F.Y., Zhou Q., Tao Q., Zou Y.N., Chen C., Zhou C.L., Yu S.Q. Evaluation of cholesterol depletion as a marker of nephrotoxicity in vitro for novel β-cyclodextrin derivatives. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011;49(6):1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.