Abstract

Chronic disease pandemics have challenged societies and public health throughout history and remain ever-present. Despite increased knowledge, awareness and advancements in medicine, technology, and global initiatives the state of global health is declining. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has compounded the current perilous state of global health, and the long-term impact is yet to be realised. A coordinated global infrastructure could add substantial benefits to public health and yield prominent and consistent policy resulting in impactful change. To achieve global impact, research priorities that address multi-disciplinary social, environmental, and clinical must be supported by unified approaches that maximise public health. We present a call to action for established public health organisations and governments globally to consider the lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and unite with true collaborative efforts to address current, longstanding, and growing challenges to public health.

Keywords: Global Public health, Health policy research, Healthy living behaviours international collaboration

Key Messages

The state of global health is perilous, and more due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes a widening of health inequalities that burden social injustice.

Development of effective COVID-19 vaccinations demonstrates the true international collaboration that prevented millions of deaths worldwide. Whilst a single intervention will not resolve the prominent rise in non-communicable diseases, the impact of united approaches, in resolving threats to population health could and should be used by key decision-makers to address the biggest global health challenges.

We must move towards adopting international standardisation of policies and approaches to addressing public health between governmental and international agencies is needed.

This approach should engage key stakeholders that represent public health, precision medicine, health care systems, national government organisations, policymakers, corporations, and quasi-governmental agencies.

Introduction

Challenges to global health and wellbeing have reached historically disconcerting levels, to a large degree paralleling changes in human behaviour [1]. Despite increased knowledge and advances in medicine, technology, and an array of global initiatives over several decades, the gap between the ‘health poor’ and the ‘health rich’ continues to widen [2]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) attributes the increase in health-Inequalities gap to changes in human behaviours [3]. Seven of the top ten causes of mortality listed by the WHO are related to non-communicable diseases [4]. Non-communicable diseases are those resulting from a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental, and behavioural factors. Tobacco use, excessive alcohol use, physical inactivity, and unhealthy diets are key lifestyle contributors to non-communicable diseases which now account for 71% (41 million) of global deaths annually [4, 5]. With the WHO identifying unhealthy lifestyle and chronic disease crises themselves as pandemics [6, 7].

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has compounded the current perilous state of global health. Not only the disease, but enforced social distancing and repeated lockdowns also adversely and severely impacted population health and wellbeing [8, 9]. Whilst the broader impacts of COVID-have taken an unprecedented toll on global health, the lasting impact, combined with the non-communicable disease pandemic, has yet to be fully felt. We foresee a worsening of health outcomes for many in the future [7, 10]. An unintended consequence of the lockdown was a deterioration in aspects of both physical and mental health in some populations [11]. Regular exercise, and by consequence increased cardiorespiratory fitness, offers protection against the most severe COVID-19 outcomes [12]. As the COVID-19 pandemic progressed, however, it became clear that restricted settings for exercise and enforced lockdowns prompted and exacerbated an increase in chronic disease risk factors and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours, including prevalence of sedentary behaviour and poor dietary choices [13, 14]. We are already seeing the effects of increased unhealthy lifestyle behaviours (decreased physical activity, increased sedentary time, poorer dietary choices) during the COVID-19 pandemic through an alarming increase in weight gain at a population level [15].

If we do not prioritise and reverse these trends, we will likely see further catastrophic increases in chronic disease incidence and prevalence [16, 17]. Clear evidence indicates that individuals who lead unhealthy lifestyles, or who already have one or more chronic disease diagnoses, are associated with a higher risk for poor outcomes if infected with COVID-19 [18]. Infections spread freely due to removal of social distancing policies, limited free testing, and lapsing of laws by governments globally to enforce isolation of those infected. The long-established unhealthy lifestyle and chronic disease pandemics, combined with the COVID-19 pandemic have created a troubling new situation, where two or more health conditions or diseases that could interact and negatively affect health outcomes [17, 19].

The burden and pressure upon healthcare services adds another dimension of complexity to an already challenging situation. Recent estimates in the United Kingdom (UK) indicate that over 6 million people are waiting for routine treatment and services, a backlog that could take several years to resolve. Healthcare systems around the world remain chronically understaffed, and with funding disproportionate relative to demand and utilisation [20]. A plethora of initiatives and international strategies have attempted to improve and promote healthy living behaviours to mitigate the risk of developing chronic health issues. Proactive and preventive approaches are the most effective [18, 21]. Historically, lack of differentiation, acceptability, and scalability have hindered these efforts [22, 23]. Policymakers and their associated health departments have generally published agendas that actively support and promote positive healthy living behaviours at local, regional, and national levels. However, given the scale of the challenges we are currently facing, now is the time to establish international policies. Pronk, Mabry et al. call for cutting across national borders to incorporate life, behavioural, implementation and system sciences in coordinating responses to current and future global health threats [24]. In the wake of COVID-19, international collaborative efforts pioneered development of efficacious vaccines in a matter of months, rather than years– and the largest and most successful vaccination strategy to mitigate serious illness and prevent millions of deaths [25]. This illustrates the advantages of uniting agendas worldwide to address global challenges to health and wellbeing, and prepare better for the next global pandemic [7]. With demand increasing at an alarming pace and with immense pressure on healthcare services, we must unite to develop coordinated approaches to promote healthy living behaviours, achieve global change, and confront a growing health and wellbeing pandemic.

Awareness of public health and the need for public health infrastructure investment and data modernization for improved surveillance are transient as reflected by mass media coverage. As we progress through the ongoing pandemic towards endemic status, media coverage and airtime have waned, resulting in reduced visibility and public awareness. The stark reality of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates we need break this reactive cycle and establish sustained approaches and investments to make progress against the social determinants of health and increase the recognition and implementation of precision public health [26].

Lessons learnt from COVID-19

Whilst the pace at which the knowledge, understanding and impacts of COVID-19 have developed is unprecedented, as illustrated by the sheer volume of COVID-19-related publications indexed on PubMed since 2020 (342,380 as of the 28th February 2023), several reflective pieces highlight lessons learnt [27]. Among them are key lessons:

Pandemic preparedness: It is abundantly clear that we were not adequately prepared for a global pandemic. Responses around the world have been largely reactive and we lack international consensus in how to prevent viral transmission and mitigate the consequences. We must now prepare appropriately for the long-term impacts of COVID-19 and prepare for inevitable future health crises [28].

Long COVID: We still do not understand the extent to which COVID-19 and Long COVID will impact healthcare provision. In January 2019, the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK published a document entitled the ‘Long Term Plan’ [29]. It contains over 120 pages of strategic planning to improve healthcare provision in the UK. It addresses reducing health inequalities, reducing pressure on staff and the most urgent service areas, increasing digital infrastructure and capability, improving staff training and development, and ensuring investment of public money to achieve maximum benefit. At first glance, this appears to be a panacea document paving the way for a revolutionary reform of healthcare services. Whilst the document provides a comprehensive approach to tackling long-standing health issues and threats to public health, a simple search returns no mention of the term pandemic, because a global pandemic was not on the agenda.

We need to revisit and rethink such strategies to include important lessons from the pandemic. Even after more than three years since the first confirmed cases, clinical specialists and scientists still do not fully understand COVID-19 nor its long-term impacts on healthcare services and population health [30]. The challenge to healthcare services will not abate, despite governments having relaxed restrictions to ‘live with’ COVID-19. We see a disproportionate allocation of research funding favouring infectious disease(s) compared to chronic health conditions which are historically underfunded. Governments direct the lion's share of funding to conduct primary research to develop mechanistic understanding and treatments for infectious diseases. But we face a causality dilemma between lifestyle behaviours and chronic disease and severity; undoubtedly, they are interconnected. We see increased disease severity in those who demonstrate unhealthily lifestyle behaviours (sedentary lifestyles, consuming unhealthy diets, smoking or have excess body mass) [31]. Those with unhealthy lifestyle characteristics run greater risks of severe outcomes during acute infection [32] and increased risks of developing long-term sequelae [33].

COVID-19 has widened health inequalities and exacerbated social injustice, with disadvantaged groups bearing the brunt of unnecessary disease and suffering caused by inequalities in health and access to healthcare services [34]. Like the UK NHS Long Term Plan, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals established in 2015 amount to a landmark initiative: a global blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all by 2030. Its ambitious targets promote healthy lifestyles for all and include pledges for all economies to promote prosperity, protect the environment, tackle climate change, and most importantly, improve equity to meet the needs of women, children, and disadvantaged populations. The drafters intended to ensure that “no one is left behind” [35]. Persistence and enormity of entrenched health inequalities, and the resultant injustices challenge achievement of the targets.

Evidence from the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that those from disadvantaged groups were most adversely affected, not only through disease outcomes and mortality [36] but also from social and economic hardship, and limited social mobility [37]. Health inequalities related to unhealthy lifestyle behaviours and chronic disease will likely be exacerbated globally for years to come, particularly in underserved communities. There, risk of poor health behaviours is coupled with danger that future variants and vaccine hesitancy will have greater adverse effects than in more advantaged communities [38]. Much remains to be done if Governments are to address and reduce international health equity gaps and improve health outcomes for pre-COVID-19 health conditions.

Is unified collaboration a potential solution?

The global response to progress COVID-19 vaccinations demonstrated the potential of international collaboration. This saw sharing of technologies and knowledge to produce effective vaccinations in record time that undeniably prevented millions of deaths and reduced the risk of serious illness in millions more [25, 39, 40]. Although it is unlikely that any single intervention will resolve the prominent rise in non-communicable diseases, this extraordinary feat demonstrates the potential and power of international and unified collaborations to resolve important threats to population health. Adopting unified and collaborative approaches, where the focus is placed on individuals to take responsibility for their health, could and should be used by key decision makers and policymakers to address proactively the biggest global health challenges. Furthermore, to ensure parity and prevent a further widening of the health inequalities gap, socio-economic factors such as access to appropriate resources to promote increased health must also be addressed [41]. A lot has been learnt about human behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic and this learning is important to obtain a broader understanding of ‘why’ people adopt unhealthy lifestyles. We propose greater efforts to achieve global changes in population health through coordinating based on these principles. We acknowledge that adopting such approaches would be complex. Key organisations and stakeholders such as the United Nations, World Health Organisation and World Bank who have a contested record of success, and some failure will need to be engaged from the onset. But if key organizations could help us to achieve united approaches to addressing the biggest health challenges, the impact on global public health could be universal for generations to come.

Any organisation seeking to maximise benefits of international collaboration needs to empower local authorities and communities. Public health interventions and promotion of healthy living behaviours need to build trust and reflect the needs of local communities, consider cultural identities, and foster local leadership. This is important for interventions and research [42]. International collaborations must ensure that international partnerships do not rely on one size fits all’ strategies, and encourage input from different countries and cultures and share best practices on how to engage local communities.

The time to adopt a global standardisation to improve public health?

Achieving standardisation in response to the biggest threats to public healthbetween governmental and international agencies will require engaging stakeholders that broadly represents the public health agenda and includes, governenments and policymakers, health care system, national government organisations, corporations, and quasi-governmental agencies [43]. Organizers of such efforts must assure established roles for key stakeholders and consider their roles and responsibilities in a coordinated model that is underpinned with systems science approaches to identify the interconnectedness of key stakeholders. This will help to better understand the impact that the work of key stakeholders has on a local and national level and how this interacts with other moving pieces [43]. Encouraging collaborative and interdisciplinary working of professional organisations and stakeholders to develop and engage with a shared vision will amplify public health policy and the development of an international health system infrastructure. Such approaches need embed collaborative thinking and working to generate shared ownership and the development of momentum in pursuit ofstandardized approaches to address a global and growing burden upon public health. Such approaches may include joint mission statements, longitudinal plaaning which exisit alongside operational opportunities such as sharing of data across ecosystems, coordination of biomedical research priorities as well as quality and performance measures for health care and public health.

How best to refine and unify funding opportunities for progress and commonality in design, development, implementation, and evaluation to promote healthy living behaviours? Only coordination will provide a focused and directed approach to uniting health research policy to drive international collaboration and implementation. Realising this ambition will require substantial investment in time and resources. Establishing an effective and global infrastructure would benefit public health in major ways, and yield prominent and consistent policy to drive more impactful and sustainable change [23]. Such infrastructure would improve our preparedness for future global health emergencies.

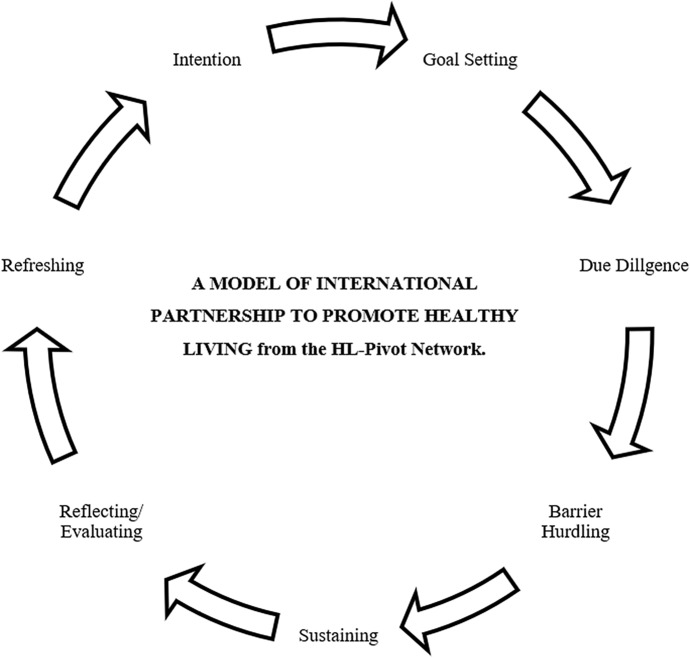

Below we present a model of international collaboration for consideration alongside other such models. The model offers a basis for dialogue among organisations and institutions seeking unified change in international public health. We intend this model to compliment official policy and criteria, including that from the WHO (see WHO Collaboration: Partnerships [44]). As with the WHO initiatives our model stresses the importance of clear goals and evaluation. We also aim to promote more debate on overcoming barriers, sustaining, and refreshing international partnerships. These three factors may be increasingly important in the context of the pandemic and climate change. We propose the following elements for debate:

Intention: International partnership does not happen by accident, is challenging to establish, and requires a long-term commitment. Inception calls for serious intent on behalf of the founding partners. Intent must come from Executive Boards of the partners and be formalised in a legally binding contract (although this can be difficult given international partnerships across legal jurisdictions) or a non-binding memorandum of understanding.

Goal Setting: International partnerships are not an end in themselves but a mechanism to promote healthy living to the biggest population possible, and to develop and share best practices, research, and professional development opportunities. Ideally, goals should be quantitative and include threshold measures. Failures to meet them signal either that the partnership requires more investment or should be terminated. Successful partnerships could support failing ones.

Due Diligence: International partnerships can be extremely rewarding, but the potential for high return on the investment of time and money also carries risks from reputation to financial. Seeking recompense from an international partner after something has gone wrong can be very difficult. Therefore, qualified and experienced professionals must conduct legal and financial due diligence in advance.

Barrier Hurdling: Barriers to success may include conflicts of interest among governments, power imbalances amongst governments being represented, resource and capacity to fulfil commitments and potential misunderstanding based on language and cultural differences; administrative and regulatory burdens; and unrealistic expectations. Arguably the best hurdling technique is patience and taking a long-term view.

Sustaining: Even the best planned and mutually beneficial international partnerships require sustaining. All parties must stay focused on agreed goals, act in good faith, and when problems occur work constructively together to resolve them.

Reflecting and evaluating: International partnerships need to be evaluated regularly. Is the partnership delivering the agreed goals? If the time and money had been invested in a different project (perhaps a national partnership) would it have yielded a better return? Ideally, such evaluations should be conducted by a third, independent party, not by participants in the partnership.

Refreshing: Even a positively evaluated partnership needs to be refreshed to keep it vibrant, contemporary, and energised. Long-term partnerships can be re-animated by rotating contact people for the respective institutions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A life-cycle model that can apply to partnerships between legally constituted bodies with an agenda to promote collaboration and change in global health areas

Previous initiatives derived by organisations such as the World Health Organisation and the United States National Institutes of Health bring together stakeholders from multiple agencies, healthcare, science, academic, and policy representatives. But outside of the COVID-19 vaccination development, we lack compelling evidence for their effectiveness at uniting and resolving any of the established global health crisis. Whilst a shared ambition to improve global health and wellbeing is assumed, a missing and arguably most important piece of the jigsaw is a lack of global and united approaches to engage with such agencies to inform the decision making and implementation processes. We also see a lack of awareness and cross-national thinking from key health agencies to promote widespread adoption and implementation of unified health agendas effective for addressing longstanding issues with global health.

Prevention as a leading directive

The complexity and interactive nature of infectious and chronic diseaseswe must consider the design, development and implementation of prevention and optimal management efforts to ensure broad efficacy and effectiveness. This remains true in the global response to COVID-19 which is complex in its pathophysiology and epidemiology [45]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, lifestyle factors (physical activity, alcohol consumption, obesity, and smoking) have been closely associated with disease severity, patient outcomes and even mortality [18, 46]. As with other chronic diseases, the aetiology and disease outcomes are affected by multi-dimensional factors as demonstrated by ethnic minority groups who were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 [47]. Their experience highlights racial and economic inequalities and social justice considerations [48, 49]. Those planning prevention efforts must consider influences coming from the larger system levels and represent the upstream determinants of health risk across society and encompass time [50]. And planners need to address interactions of multiple chronic conditions, infectious diseases, and healthy living factors: how can we use knowledge to generate the most effective treatments and optimal outcomes?

Research priorities and funding

The challenge to public health amidst unhealthy living and chronic disease pandemics is more prominent now than ever before. Contemporary health crises have accelerated the COVID-19 pandemic. The need to establish research priorities in response to COVID-19 must be used effectively to address health and wellbeing, and social and economic impacts for the future [51]. To achieve universal impact, research priorities that address multi-disciplinary social, environmental, and clinical priority areas should be bolstered by unified and collaborative approaches that maximise the benefit to public health. We propose that this can be achieved with considered and coordinated approaches as follows:

Data capture and sharing

A House of Lords report from the UK Government highlighted a lack of unified approaches to capturing an accurate picture of how people participate in sports and recreation activities to inform policy development and key decision-making [52]. A recommendation followed: to create a national physical activity observatory as a centre for independent research and analysis of data related to sport and recreation policy and practice. But why stop at a national level? International observatories for healthy living behaviours would be immensely advantageous to international understanding. And they could provide universal oversight for those formulating policy initiatives. Such surveillance mechanisms could create a supportive environment for sharing experiences and using learning in all aspects of public health for developing interventions, effective implementation, evaluation, and, later, refining all. These shared attributes could contribute to a global step-change in making public health approaches more effective. Technology, mobile phone data and wearable smart technologies, has accelerated our capability and opportunity to monitor health status remotely and independently. Using data from these non-traditional surveillance mechanisms could provide important insight into behavioural approaches to inform the implementation of precision medicine approaches which should be used to identify and address important determinants of public health and health-inequalities. In the development of such observatories, we acknowledge the barriers that inhibit data and research sharing. Often these are differences in data governance and data protection laws. A move to international collaboration requires buy-in from all ‘key stakeholders and must be championed by leading governments and health organisations.

Evaluation, metrics of success, and impact

In the context of global health, in contrast to international relations and politics, collaboration is not an end in itself. Is the collaboration succeeding or failing? Even modest international partnerships have a duty to their stakeholders to evaluate this with honesty and transparency. Evaluation and reflection must be built into all aspects of a project for any international collaboration from its conception. This begins with:

A clear statement of the goals of the partnership;

Agreement on measures to use to determine if the collaboration has succeeded in meeting these goals;

Deciding how often and when these measures will be taken, and

Determining what actions will be taken if the measures indicate success and what action will be taken if they indicate failure.

Ideally, these points would be represented in a legal contract or a memorandum of understanding. Following the implementation of these four steps, best practice would ensure that the evaluation be submitted simultaneously to the Boards of the partners and followed by open dialogue and consultation. Regular evaluation and a subsequent action plan should be published in the interests of openness and transparency (Table 1).

Table 1.

An indication of commonly encountered problems with evaluating international partnerships and how they might be overcome

| Common problems with evaluations | Possible solutions |

|---|---|

| Changing the ‘goal posts’ or having no ‘goal posts’ at all | Goals need to be formally ‘signed off’ < by whom > and only changed with Board level approval |

| Getting the timing wrong | A realistic view needs to be taken about how long it is going to take to achieve the agreed goals of the partnership. Arguably everything tends to take at least twice as long as originally thought(?) |

| Ignoring the opportunity cost | If investing $100 in an international collaboration result in a return of $200 in health benefits. It is tempting to see this as a success, but this ignores what could have been achieved if this $100 had been spent ‘in the country’—if it could have led to a $500 return that puts the return on the international project in a very different context. So always ask could we have spent the money on something better? |

| The ‘Blame game | Even the best-planned, best led and most strategically important partnerships can fail. Evaluations should be about learning lessons and holding people to account but never ‘witch hunts. Those conducting the evaluation should create a culture of openness, fairness, and transparency |

| Not staying ‘grounded’ | International collaborations can be perceived as rather ‘glamorous’ and somewhat removed from the humdrum day-to-day grind of the organisations. Therefore, evaluations need to ensure that they stay grounded and focus on what is being achieved |

| Forgetting climate change | International collaborations should be good for the health of the planet as well as people. Every partnership should understand its carbon footprint and aim for Net-Zero. It is worth noting that flying business class from London to Hong Kong return costs around 10 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions whilst a one-hour zoom call on a laptop cost around 50 grammes (Mike Berners—Lee. 2020. How Bad are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything. Profile Books—replace with ref citation) |

| Looking inward not outward | It is entirely legitimate for organisations to enter partnerships for internal benefit. This might include, for example, increasing their reputation or sharing staff development opportunities. However, it is also important that evaluations ask how the collaboration is improving public health. How does this partnership, for example, help more people be more active more often? How many people benefit? What is the mechanism by which this benefit occurs? Could the benefit have been achieved more cost-effectively? |

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine and started a war in Europe, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine sent an open letter to the global scientific and educational community asking for support. This reasonable request from our colleagues suffering under, as they state, a ‘completely shameful military attack’ illustrates the complexity of international collaboration and of evaluation. A holistic review of the global public health infrastructure, investment in public health from international governments and key agencies which includes the WHO and NIH, must be conducted to document variations in public health operations and the capacity to address key public health challenges across nations. Together we need to consider global coordination, including how to overcome barriers to sharing data and research. We could use insights obtained from this work to inform development of public health strategies that identify the measures for evaluating the impact of public health investments, including calculation of the value or return on such investments.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated unprecedented health and healthcare challenges for countries around the world. Unhealthy living behaviours, already rampant for decades, moved again the forefront of public health. The consequences have contributed considerably to poor outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing and reversing the unhealthy living—chronic disease—COVID-19 syndemic must occur through global collaboration and distribution of research funds. We must prioritse healthy living behaviours as a global theme stimulating global collaboration. Taking lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic and through mutually beneficial and effective global collaborations, we can perhaps create a healthier world for all.

Biographies

Mark A. Faghy,

Ph.D., is a associate professor in respiratory physiology in the Biomedical and Clinical Research Theme, School of Human Sciences, University of Derby, Derby, UK; visiting researcher in Department of Physical Therapy, College of Applied Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA; and core member of the Healthy Living for Pandemic Event Protection (HL – PIVOT) Network, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Laurie Whitsel,

Ph.D., is National Vice President-Policy Research and Translation Senior Advisor-Physical Activity Alliance American Heart Association and and member of the Healthy Living for Pandemic Event Protection (HL – PIVOT) Network, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Ross Arena,

Ph.D., Professor and Department Head, Physical Therapy University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA and lead of the Healthy Living for Pandemic Event Protection (HL – PIVOT) Network, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Andy Smith,

Ph.D., retired professor of sport and exercise science and member of the Healthy Living for Pandemic Event Protection (HL – PIVOT) Network, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Ruth E. M. Ashton,

Ph.D., a lecturer in exercise physiology in the Biomedical and Clinical Research Theme, School of Human Sciences, University of Derby, Derby, UK; visiting researcher in Department of Physical Therapy, College of Applied Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA; and core member of the Healthy Living for Pandemic Event Protection (HL – PIVOT) Network, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Smith A, Broom D, Murphy M, Biddle S. A Manifesto for exercise science—a vision for improving the health of the public and planet. J Sports Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1080/02640414.2022.2049083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinker S. Enlightenment Now. Penguin UK; 2018. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Enlightenment_Now/J6grDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Pinker,+Enlightenment+Now&printsec=frontcover. Accessed 18 May 2022

- 3.World Health Organization. Behavioural Sciences for Better Health. https://www.who.int/initiatives/behavioural-sciences. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

- 4.World Health Organisation. Non communicable diseases. Noncommunicable diseases. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. Accessed 8 Mar 2022

- 5.Bertram MY, Sweeny K, Lauer JA, Chisholm D, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, et al. Investing in non-communicable diseases: an estimation of the return on investment for prevention and treatment services. The Lancet. 2018;391(10134):2071–2078. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, et al. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):294–305. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen L. Are we facing a noncommunicable disease pandemic? J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2017;7(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connor RC, Wetherall K, Cleare S, McClelland H, Melson AJ, Niedzwiedz CL, et al. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;218(6):326–333. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernández YAT, Parente F, Faghy MA, Roscoe CM, Maratos FA. Influence of the COVID-19 lockdown on the physical and psychosocial well-being and work productivity of remote workers: cross-sectional correlational study. JMIRx Med. 2021;2(4):e30708. doi: 10.2196/30708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atun R, Jaffar S, Nishtar S, Knaul FM, Barreto ML, Nyirenda M, et al. Improving responsiveness of health systems to non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. 2013;381(9867):690–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basterfield L, Burn NL, Galna B, Batten H, Goffe L, Karoblyte G, et al. Changes in children’s physical fitness, BMI and health-related quality of life after the first 2020 COVID-19 lockdown in England: a longitudinal study. J Sports Sci. 2022;40(10):1088–1096. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2022.2047504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harber MP, Peterman JE, Imboden M, Kaminsky L, Ashton RE, Arena R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign of CVD risk in the COVID-19 era. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Mattioli AV, Sciomer S, Cocchi C, Maffei S, Gallina S. Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(9):1409–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laddu DR, Biggs E, Kaar J, Khadanga S, Alman R, Arena R. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular health behaviors and risk factors: a new troubling normal that may be here to stay. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bhutani S, vanDellen MR, Cooper JA. Longitudinal weight gain and related risk behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in adults in the US. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):671. doi: 10.3390/nu13020671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall G, Laddu DR, Phillips SA, Lavie CJ, Arena R. A tale of two pandemics: how will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;64:108. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arena R, Hall G, Laddu DR, Phillips SA, Lavie CJ. A tale of two pandemics revisited: physical inactivity, sedentary behavior and poor COVID-19 outcomes reside in the same Syndemic City. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Arena R, Lavie CJ, Network HP. The global path forward-healthy living for pandemic event protection (HL-PIVOT). Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;S0033–0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.O’Connor SM, Taylor CE, Hughes JM. Emerging infectious determinants of chronic diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(7):1051–1057. doi: 10.3201/eid1207.060037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ndugga N, Artiga S. Disparities in health and health care: 5 key questions and answers. KFF. 2021 . https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/disparities-in-health-and-health-care-5-key-question-and-answers/. Accessed 8 Mar 2022

- 21.Amerzadeh M, Salavati S, Takian A, Namaki S, Asadi-Lari M, Delpisheh A, et al. Proactive agenda setting in creation and approval of national action plan for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in Iran: The use of multiple streams model. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 10.1007/s40200-020-00591-4

- 22.Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC, et al. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1337–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pronk NP, Faghy MA. Causal systems mapping to promote healthy living for pandemic preparedness: a call to action for global public health. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022;19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12966-022-01255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pronk NP, Mabry PL, Bond S, Arena R, Faghy MA. Systems science approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention and management in the era of COVID-19: a humpty-dumpty dilemma? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033062022001554. Accessed 10 Jan 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed | NEJM. 10.1056/NEJMp2005630. Accessed 8 Mar 2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Whitsel LP, Ajenikoko F, Chase PJ, Johnson J, McSwain B, Phelps M, et al. Public policy for healthy living: how COVID-19 has changed the landscape. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Faghy M, Arena R, Hills AP, Yates J, Vermeesch AL, Franklin BA, et al. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic: with hindsight what lessons can we learn? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Smith A, de Oliveira R, Faghy M, Ross M, Maxwell N. BASES’ Position stand on the ongoing pandemic. 2021

- 29.NHS. NHS Long Term Plan » The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/. Accessed 12 May 2020

- 30.Yelin D, Wirtheim E, Vetter P, Kalil AC, Bruchfeld J, Runold M, et al. Long-term consequences of COVID-19: research needs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(10):1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30701-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arena R, Lavie CJ, Faghy MA, Network HP. What comes first, the behavior or the condition? In the COVID-19 era, it may go both ways. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;100963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Hashim MJ, Alsuwaidi AR, Khan G. Population risk factors for COVID-19 mortality in 93 countries. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;10(3):204. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.200721.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmot M. Health in an unequal world. The Lancet. 2006;368(9552):2081–2094. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee BX, Kjaerulf F, Turner S, Cohen L, Donnelly PD, Muggah R, et al. Transforming our world: implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J Public Health Policy. 2016;37(1):13–31. doi: 10.1057/s41271-016-0002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez-Barranco M, Rivas-García L, Quiles JL, Redondo-Sánchez D, Aranda-Ramírez P, Llopis-González J, et al. The spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain: hygiene habits, sociodemographic profile, mobility patterns and comorbidities. Environ Res. 2021;192:110223. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah GH, Shankar P, Schwind JS, Sittaramane V. The detrimental impact of the COVID-19 crisis on health equity and social determinants of health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020;26(4):317–319. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harder T, Külper-Schiek W, Reda S, Treskova-Schwarzbach M, Koch J, Vygen-Bonnet S, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection with the Delta (B. 1.617. 2) variant: second interim results of a living systematic review and meta-analysis, 1 January to 25 August 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26(41):2100920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Rashedi R, Samieefar N, Masoumi N, Mohseni S, Rezaei N. COVID-19 vaccines mix-and-match: the concept, the efficacy and the doubts. J Med Virol. 2022;94(4):1294–1299. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lahelma E, Martikainen P, Laaksonen M, Aittomäki A. Pathways between socioeconomic determinants of health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(4):327–332. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas JR, Martin P, Etnier J, Silverman SJ. Research methods in physical activity. Human kinetics; 2022.

- 43.Arena R, Guazzi M, Lianov L, Whitsel L, Berra K, Lavie CJ, et al. Healthy lifestyle interventions to combat noncommunicable disease—a novel nonhierarchical connectivity model for key stakeholders: a policy statement from the American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, and American College of Preventive Medicine. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(31):2097–2109. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization. WHO Collaboration: Partnerships. https://www.who.int/about/collaboration/partnerships Accessed 28 Feb 2023

- 45.Parasher A. COVID-19: current understanding of its pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatment. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1147):312–320. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li S, Hua X. Modifiable lifestyle factors and severe COVID-19 risk: a Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12920-021-00887-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lassalle PP, Meyer ML, Conners R, Zieff G, Rojas J, Faghy MA, et al. Targeting sedentary behavior in minority populations as a feasible health strategy during and beyond COVID-19: on behalf of ACSM-EIM and HL-PIVOT. Transl J Am Coll Sports Med. 2021;6(4):e000174. doi: 10.1249/tjx.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magesh S, John D, Li WT, Li Y, Mattingly-App A, Jain S, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2134147–e2134147. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jayasinghe S, Faghy MA, Hills AP. Social justice equity in healthy living medicine—an international perspective. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022 Apr 28. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033062022000378. Accessed 5 May 2022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Arena R, Faghy M, Laddu D. A perpetual state of bad dreams: The prevention and management of cardiovascular disease in the COVID-19 pandemic era and beyond. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Faghy MA, Arena R, Babu AS, Christle JW, Marzolini S, Popovic D, et al. Post pandemic research priorities: a consensus statement from the HL-PIVOT. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.House of Lords. National Plan for Sport and Recreation Committee - Summary - Committees - UK Parliament. United Kingdom: House of Lords; 2021, p. 150. https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/482/national-plan-for-sport-and-recreation-committee/. Accessed 18 May 2022