Abstract

Anemia is a largely preventable and curable medical disease if detected intime. This study aimed to assess maternal knowledge of anemia and its prevention strategies in the public health facilities of Pawi district, Northwest, Ethiopia. A health facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from February 1/2020 to March 2/2020, among 410 antenatal care attendees in the public health facilities of the Pawi district. The data was collected by systematic random sampling technique and analyzed using SPSS 25.0 version. Logistic regression analyses were done to estimate the crude and adjusted odds ratio with a CI of 95% and a P-value of less than .05 considered statistically significant. Less than half, 184 (44.9%) [95% CI = 40.0-49.8] and almost half, 216 (52.7%) [95% CI = 47.8-57.5] of the pregnant women had good knowledge of anemia and good adherence to its prevention strategies respectively. Women who are found in the age group of 15 to 19, 20 to 24, and 25 to 29 years, rural residency, secondary, and above educational level, vaginal bleeding, third trimester of pregnancy, and medium and high minimum dietary diversification score were significantly associated with knowledge of anemia. On the other hand: women who are found in the age group of 15 to 19 years, secondary above educational level, primigravida women, having ≤2 and 3 to 4 family sizes, second and third trimester of pregnancy, high minimum dietary diversification score, and good knowledge of anemia were significantly associated with adherence to anemia prevention strategies. Maternal knowledge of anemia and adherence to its prevention strategies were low. Nutritional counseling on the consumption of iron-rich foods and awareness creation on the effects of anemia in pregnant women must be strengthened to increase the knowledge of anemia and adherence to its prevention strategies.

Keywords: anemia, antenatal care, adherence, Ethiopia, knowledge, prevention strategies, iron folate supplementation, maternity, nutritional counseling, pregnant women

What do we already know about this topic?

Anemia is the known indirect cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, however, it is largely preventable and easily treatable, if detected in time.

How does your research contribute to the filed?

Our study showed that both the knowledge and adherence to anemia prevention strategies were low in the study area, which indicates a need of continuing taking appropriate action to reduce the effects of the problem.

What are your research implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

The finding of this study helps to identify the gap and strengthen the action to increase the knowledge level of pregnant women about anemia and its prevention strategies.

Introduction

Anemia is considered the most common blood disorder which affects about one-third of the global population. 1 It is characterized by a decline in the number or size of red blood cells and hemoglobin concentration and results in an impaired capacity to transport oxygen. 2 Globally, the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy is estimated to be approximately 38.2%. 3 In South-East Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Africa, 38.9% to 48.7% of pregnant women were anemic. 3 In Ethiopia, based on a systematic review and meta-analysis report, around 32% of pregnant women were affected by anemia. 4 Anemia is considered a public health problem when the prevalence is higher than 40%. 3 It is estimated to contribute to more than 115 000 or 20% of all maternal deaths and is also responsible for 591 000 prenatal deaths globally per year. 2

Anemia in pregnancy is identified by the World Health Organization as hemoglobin levels less than 11 gm/dl. 3 Iron deficiency anemia is the most common nutritional problem in the world today, accounting for approximately 50% of cases worldwide, 5 and it is the cause of 75% of anemia cases during pregnancy. 6 In a non-pregnant state, an adult woman has about 2000 mg of iron in her body. However, when she becomes pregnant, the demand for iron increases by an additional 1000 mg. Overall, normal pregnancy increases the iron requirement by 2 to 3 fold and the folate requirement by 10 to 20 fold.7-9

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend screening for anemia in pregnant women and universal iron supplementation to meet the iron requirements of pregnancy. 10 The WHO also recommends that all pregnant women receive iron supplements of 60 mg daily combined with a pill that also contains 400 μg of folic acid. 11 In Ethiopia, based on a mini Ethiopia demography health survey 2019 report, among women with a live birth in the past 5 years, 60% took iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS) tablets during pregnancy, and only 11% took them for the recommended period of 90 or more days. 12 Pregnant women suffering from anemia and their neonates encounter negative consequences, including experience of general fatigue, fetal anemia, low birth weight, preterm delivery, increased risk of post-partum hemorrhage, intrauterine growth restriction, perinatal mortality stillbirth, reduced work capacity, low tolerance to infections, shortness of breath, reduced physical, and mental performance.13,14

In pregnant women, anemia remains one of the most intractable major public health problems, especially in developing countries due to various socio-cultural problems like shortage of essential nutrients, iron folate, vitamins, poverty, lack of knowledge, poor dietary habits, parasitic infestation, acute or chronic blood loss, human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis, malaria, short inter-pregnancy interval, high parity, cultural beliefs and practices regarding nutrition, non-usage of an insecticide-treated bed net, and late booking of pregnant women at antenatal care (ANC) units.14-18

Anemia can be prevented by implementing the strategies of anemia prevention methods. The strategies of anemia prevention are iron supplementation, regular de-worming, control, and prevention of parasitic infections in pregnancy, such as by using insecticide-treated bed net consistently, intake of iron-rich foods, nutritional counseling such as not taking coffee, tea, or milk with meals, accessing clean and adequate water, and by treating the underlying causes and complications.19-24

Adherence to anemia prevention strategies plays a major role in the prevention and treatment of anemia among pregnant women whose iron requirement increases due to physiologic demands. 7 Having knowledge of anemia and following through with the proper practice of anemia prevention methods are vital to reducing the prevalence of anemia. 25 In 2012, the World Health Assembly planned the second global nutrition target and one of these targets was a 50% reduction of anemia among women of reproductive age by the year 2025. 1 Anemia has devastating effects on both the mother’s and child’s health. However, it is a largely preventable and curable medical disease if detected at times. Therefore, this study aimed to assess maternal knowledge of anemia and adherence to its prevention strategies. Additionally, it also identified the factors associated with the knowledge of anemia and its prevention strategies among ANC attendees in the public health facilities of Pawi district, North-west, Ethiopia.

Methods

Study Design and Period

A health facility-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from February 1/2020 to March 2/2020 in the public health facilities of the Pawi district.

Study Setting

Pawi district is located about 526 km away from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, and 421 km from Benishangul Gumuz regional state, Assosa city. The district has 20 Kebeles with a total population of 89 807 (44 960 males and44 847 females). 26 Regarding the health facilities, the district has one public hospital, 2 health centers, 3 private clinics, and 6 drug shops. The total number of pregnant women who visited Pawi general hospital, Felege Selam, and Mender 14 health center ANC units per day on average was 30, 4, and 6, respectively.

Source Population

The study included randomly selected consenting pregnant women who attended ANC in the public health facilities of the Pawi district. During the data collection period, pregnant women who revisited the ANC unit re excluded.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula using the prevalence estimate of good knowledge of anemia (P1) and good adherence to anemia prevention strategy (P2). Knowledge of anemia (P1) was calculated by considering the following assumptions: prevalence of good knowledge of anemia (P1) in Harar town was 61.0%, 27 Zα/2 = critical value for normal distribution at 95% confidence level, which is equal to 1.96 (Z value of α = 0.05) or 5% level of significance (α = .05) and a 5% margin of error (ω = .05).

The sample size was adjusted by adding a 10% non-response rate and it was 403.

For the second objective (P2), the sample size was calculated by taking adherence to an anemia prevention strategy from a study conducted in Harar town, which was 41.4%. 27

The sample size was adjusted by adding a 10% non-response rate and it was 410. We used the largest sample size obtained from adherence to anemia prevention strategy and it was 410.

Sampling Procedure and Technique

After considering 3 of the public health facilities in the district, the total sample size was proportionally allocated for each health facility in the district based on their quarterly ANC flow. The number of pregnant women who have attended the ANC unit quarterly at Pawi hospital, Mender 14 health, and Felege Selam health center were 2640, 320, and 480 respectively. The total sample size was proportionally allocated for each health facility in the district, based on their population size. The total sample size after proportional allocation was 315, 38, and 57 pregnant women for Pawi hospital, Mender 14, and Felege Selam health center respectively. Then eligible pregnant women in each facility were selected by using systematic random sampling techniques based on their monthly ANC visits. The numbers of ANC flow monthly in Pawi Hospital, Mender 14, and Felege Selam health center were 660, 80, and 120, respectively. The sampling interval (Kth units) was obtained by dividing the number of pregnant women who attended ANC monthly in the Paw public district facilities by the sample size (860/410), which was approximately 2. The starting unit was selected using the lottery method among the first kth units in each health facility.

Dependent Variable

Knowledge of anemia, and adherence to its prevention strategies

Independent Variables

Socio-demographic factors (maternal age, residency, marital status, religion, educational level and occupation of mothers and husbands, and family size), obstetric characteristics of the mothers (gravidity, history of abortion, gestational age, and history of antepartum hemorrhage), and nutritional related characteristics (hemoglobin level, MUAC, and MDDS).

Operational Definitions

Knowledge of anemia: refers to the knowledge of pregnant women about anemia and it was assessed using 25 composite variables. Those who responded “yes” were scored “+1,” and those who responded “no” were scored “0” The mother was considered to have good knowledge if she correctly answered greater than or equal to the mean score of the total knowledge assessing questions. 23

Adherence to anemia prevention strategies: refers to the adherence of pregnant women to anemia and it was assessed using 8 composite variables. Those who responded “yes” were scored “+1” and those who responded “no” were scored “0.” The mother was considered to have good adherence if she correctly answered greater than or equal to the mean score of the total knowledge assessing questions. 23

Mid Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC): it was assessed by measuring the MUAC of pregnant women. It was measured halfway between the olecranon and acromion process using non-stretchable tape to the nearest 0.1 cm. Pregnant women were considered undernutrition if the MUAC measurement was less than <23 cm. 28

Minimum dietary diversity score (MDDS): it was assessed using a 24-h recall method. The women were asked whether they had taken any food from 9 pre-defined groups, which include; cereals, pulses, dark green leafy vegetables, vitamin A-rich fruit, meats and fish, eggs, nuts and seeds, milk and milk products, and oils and fats). A woman who had consumed (at least once) the food within each subgroup scored “1” unless “0” was given. Finally, the mother’s dietary intake was categorized as poor, medium, and high if she consumed ≤3 food groups, 4 to 5 food groups, and ≥6 food groups, respectively. 29

Data Collection Tools

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect the quantitative data which was adapted from relevant works of literature and modified to the local context.23,27,28,30 The questionnaire was first prepared in the English language, then it was translated into Amharic by an individual who has a good working knowledge of these languages, and finally retranslated back into English to check the consistency. The questionnaire consisted of socio-demographic, obstetric, nutritional, knowledge, and adherence to anemia prevention strategies related questions.

Data Quality Control

The data collectors and supervisors were trained for 2 days by the investigators. The questionnaire was pre-tested before the actual data collection period on 5% (21) mothers at Gilgelbelles health center, which has similar characteristics to the study population, to ensure the clarity of the questionnaire, to check the wording, and confirm the logical sequence of the questions. After necessary modifications and corrections were done to standardize and ensure its reliability and validity, additional adjustments were made based on the results of the pre-test.

Data Collection Procedures

The data were collected by 3 diploma midwives, and 3 laboratory technicians, and supervised by one BSc midwife and one laboratory technologist. A venous blood sample was taken from the study participants using a heparinized hematocrit tube and labeled with an identification number. The collected blood was placed on proper anticoagulant EDTA and analyzed within an hour. The nutritional status of the participants was assessed by measuring the MUAC halfway between the olecranon and acromion process using non-stretchable tape to the nearest 0.1 cm. During the data collection period, daily supervision was done for data completeness.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data were entered into Epi data 3.5, edited and cleaned for inconsistencies, missing values, and outliers, then exported to the SPSS 25.0 version for analysis. During the analysis, all explanatory variables which had a significant association in bivariate analysis with a P-value of <.20 were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model to get an adjusted odds ratio (AOR). Those variables with 95% confidence intervals and a P-value of <.05 were considered statistical significance with the knowledge of anemia and adherence to anemia prevention strategies. The multicollinearity test was done using the variance inflation factor and no collinearity exists between the independent variables. The model goodness of the test was checked using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of the fit test and its P-value was .907 for knowledge of anemia prevention and .604 for adherence to anemia prevention strategies. Frequency tables, figures, and descriptive summaries were used to describe the study variables.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

In this study, a total of 410 pregnant women participated with a response rate of 100%. The mean age of the women was 25.00 years with a standard deviation of ±4.68 and ranging from 15 to 42 years. Of the women, 153 (37.2% were found in the age group of 25 to 29 years and 225 (54.9%) lived in urban areas. About 406 (99.0%) of the women married and 261 (63.7%) were Orthodox Christian religion followers. Four out of the 9 women, 182 (44.4%) attended primary education and 261 (63.7%) were housewives. Regarding their partners, 127 (31.3%) had attended primary education, and 196 (48.3%) are farmers. About half, 213 (52.0%) of the women had a family size of 2 to 4 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Pregnant Women Who Attended ANC in the Public Health Facilities of Pawi District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age in years | |

| 15-19 | 40 (9.8) |

| 20-24 | 129 (31.5) |

| 25-29 | 153 (37.2) |

| 30-34 | 88 (21.5) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 225 (54.9) |

| Rural | 185 (45.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 406 (99.0) |

| Others* | 4 (1.0) |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox | 261 (63.7) |

| Muslim | 91 (22.2) |

| Protestant | 53 (12.9) |

| Catholic | 5 (1.2) |

| Maternal educational level | |

| Had no formal education | 123 (30.0) |

| Primary education | 182 (44.4) |

| Secondary education | 63 (15.4) |

| Diploma and above | 42 (10.2) |

| Maternal occupation | |

| Housewives | 261 (63.7) |

| Merchant/self-employee | 114 (27.8) |

| Government employed | 35 (8.5) |

| Educational status of partner (n = 406) | |

| Had no formal education | 73 (18.0) |

| Primary education | 127 (31.3) |

| Secondary education | 119 (29.3) |

| Diploma and above | 87 (21.4) |

| Occupation of the partner (n = 406) | |

| Farmer | 196 (48.3) |

| Merchants/self-employee | 131 (32.3) |

| Government employee | 79 (19.4) |

| Family size | |

| <2 | 83 (20.2) |

| 2-4 | 213 (52.0) |

| >5 | 114 (27.8) |

Single and divorced.

Obstetric Characteristics

Seven out of the ten women, 287 (70.0%) were multigravida and 66 (16.1%) had a history of abortion. About 228 (55.6%) were interviewed in their second trimester of pregnancy, and 45 (11.0%) had a history of antepartum hemorrhage in the current pregnancy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric Characteristics of Pregnant Women Who Attended ANC in the Public Health Facilities of Pawi District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gravida | |

| Primigravida | 123 (30.0) |

| Multigravida | 287 (70.0) |

| History of abortion | |

| Yes | 66 (16.1) |

| No | 344 (83.9) |

| Gestational age in a trimester | |

| First | 60 (14.6) |

| Second | 228 (55.6) |

| Third | 122 (29.8) |

| History of antepartum hemorrhage in a current pregnancy | |

| Yes | 45 (11.0) |

| No | 365 (89.0) |

Nutritional Characteristics

Based on the predetermined criteria, 184 (44.9%) and 105 (25.6%) of the women had medium and high dietary diversity scores respectively. Of the women, 117 (28.5%) had MUAC <23 cm, and nearly two-thirds, 272 (66.3%) had ≥11 g/dl hemoglobin level (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nutritional Characteristics of Pregnant Women Who Attended ANC in the Public Health Facilities of Pawi District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Minimum Dietary Diversity Score food groups (multiple responses were possible) | |

| Cereal/starchy staples | 321 (78.3) |

| Pulses (beans, peas, and lentils) | 271 (66.1) |

| Dark green leafy vegetables | 181 (44.2) |

| Vitamin A-rich fruit | 125 (30.5) |

| Egg | 53 (12.9) |

| Meat and fish | 60 (14.6) |

| Nuts and seeds | 134 (32.7) |

| Milk and milk product | 106 (25.9) |

| Oils and fats | 385 (93.9) |

| Minimum dietary diversity score | |

| Poor | 121 (29.5) |

| Medium | 184 (44.9) |

| High | 105 (25.6) |

| MUAC | |

| Undernourished (<23 cm) | 117 (28.5) |

| Normal (≥23 cm) | 393 (71.5) |

| Hemoglobin level (anemia status) | |

| Non anemic (Hb ≥ 11 g/dl) | 272 (66.3) |

| Anemic (Hb <11 g/dl) | 138 (33.7) |

Knowledge of Anemia

Approximately 4 in 9 women, 184 (44.9%) [95% CI = 40.0-49.8] had good knowledge of anemia. More than half, 216 (52.7%) of the women know that anemia is a decrease in the concentration of red blood cells or hemoglobin in the blood, and 225 (55.1%) identified acute or chronic blood loss as a major risk factor of anemia. Nearly one-third, 134 (32.7%) mentioned physical weakness or fatigue as symptoms of anemia, and 212 (51.7%) know that anemia can be treated. About 199 (48.5%) of the women know that pregnant women are at risk for anemia, and 183 (44.6%) know that anemia may lead to serious health problems for the mother and the expected baby. Of the women, 259 (63.2%) know that anemia can be prevented by taking iron and folic acid supplementation, and 103 (25.1%) responded that drinking coffee, tea, or milk with meals or immediately after meals reduces iron absorption in the body (Table 4).

Table 4.

Knowledge of Anemia Among Pregnant Women Who Attended ANC in the Public Health Facilities of Pawi District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| What does anemia mean? | |

| A decrease in the concentration of red blood cells or Hb level in the blood | 216 (52.7) |

| I don’t know | 194 (47.3) |

| Causes/risk of anemia in pregnancy (multiple responses were possible) | |

| Malnutrition | 192 (46.8) |

| Parasitic infestations | 119 (29.0) |

| Malaria | 95 (23.2) |

| Acute/chronic blood loss | 225 (55.1) |

| Chronic medical illness | 134 (32.7) |

| High parity | 113 (27.6) |

| Short inter-pregnancy interval | 120 (29.3) |

| How can one know that she is suffering from anemia (multiple responses were possible) | |

| Paleness of the skin | 80 (19.5) |

| Shortness of breathing | 26 (6.3) |

| Physical weakness/fatigue | 134 (32.7) |

| Poor appetite | 56 (13.7) |

| Fainting | 117 (28.5) |

| Headaches | 104 (25.4) |

| Can anemia be treated | |

| Yes | 212 (51.7) |

| I don’t know | 198 (48.3) |

| Does pregnant woman are at risk for anemia | |

| Yes | 199 (48.5) |

| No | 211 (51.5) |

| Can anemia cause a serious problem in maternal health | |

| Yes | 183 (44.6) |

| No | 227 (55.4) |

| Can anemia cause a serious problem for the expected baby | |

| Yes | 183 (44.6) |

| No | 227 (55.4) |

| How can one protect herself from getting anemia (multiple responses were possible) | |

| Eating food enriched with iron sources | 143 (34.9) |

| Taking IFAS | 259 (63.2) |

| Drinking or eating fruits | 103 (25.1) |

| Spacing childbirth | 129 (31.5) |

| Deworming | 86 (21.0) |

| Sleeping under ITNs | 65 (15.9) |

| Drinking tea, coffee, and milk after meals reduces iron absorption in the body | |

| Yes | 103 (25.1) |

| No | 307 (74.9) |

| Knowledge of anemia | |

| Good knowledge | 184 (44.9) |

| Poor knowledge | 226 (55.1) |

Adherence to Anemia Prevention Strategies

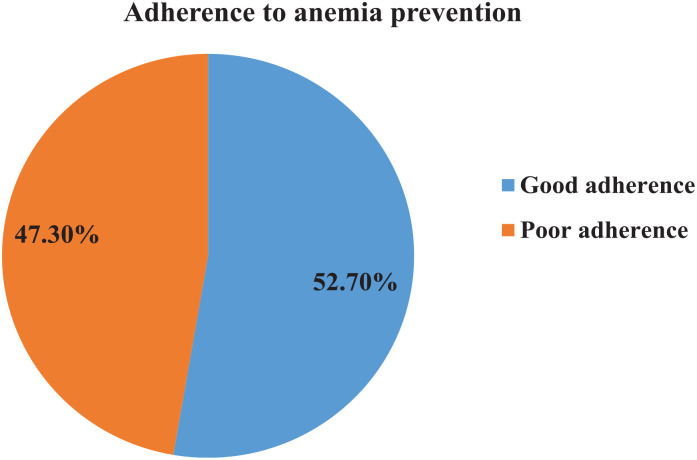

In this study, 216 (52.7%) [95% CI = 47.8-57.5] pregnant women had good adherence to anemia prevention strategies (Figure 1). About 334 (81.5%) of women drink coffee, tea, or milk with meals, and 286 (69.8) take IFAS consistently. Of the women, 289 (70.5%) have consumed meals more than 3 times per day and, 157 (38.3%) consume meat at least once per week. About 186 (45.4%) women drink or eat fruit at least once per week, and 272 (66.3%) include vegetables in their meals. Four out of ten 165 (40.2%) of the women were dewormed regularly, and 185 (45.4%) slept under an insecticide-treated bed net regularly (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Adherence to anemia prevention strategies among pregnant women who attended ANC in the public health facilities of Pawi district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

Figure 2.

Anemia prevention strategies among pregnant women who attended ANC in the public health facilities of Pawi district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

Factors Associated With Anemia in Pregnant Women

In bivariate analysis: maternal age, residence, maternal educational status, gravidity, history of abortion, trimester of pregnancy, history of vaginal bleeding in the current pregnancy, MDDS, and anemia status of the mothers was significantly associated with knowledge of anemia at a P-value of less than .2.

In multivariable analysis women who are found in the age group of 15 to 19, 20 to 24, and 25 to 29 years (AOR = 3.80, 95% CI = 1.52-9.51), (AOR = 3.00, 95% CI = 1.51-5.94) and (AOR = 2.32, 95% CI = 1.20-4.49) respectively, rural residency (AOR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.14-2.99), secondary education and diploma and above (AOR = 4.28, 95% CI = 2.03-9.06), and (AOR = 5.58, 95% CI = 2.31-13.43) respectively, having a history of vaginal bleeding in current pregnancy (AOR = 3.25, 95% CI = 1.44-7.33), third trimester of pregnancy (AOR = 3.43, 95% CI = 1.55-7.60), medium and high MDDS (AOR 4.26, 95% CI = 2.35-7.71), and (AOR = 5.10, 95% CI = 2.63-9.89) respectively were significantly associated with knowledge of anemia at a P-value of less than .05 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Logistic Regression Analysis for Maternal Knowledge of Anemia Among Women Who Attended ANC in the Public Health Facilities of Pawi District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

| Variables | Knowledge of anemia | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | ||||

| Maternal age in years | |||||

| 15-19 | 25 | 15 | 4.20 (1.91-9.26) | 3.80 (1.52-9.51) | .004* |

| 20-24 | 66 | 63 | 2.64 (1.48-4.71) | 3.00 (1.51-5.94) | .002* |

| 25-29 | 68 | 85 | 2.02 (1.15-3.54) | 2.32 (1.20-4.49) | .013* |

| >30 | 25 | 63 | 1 | 1 | |

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 121 | 104 | 2.25 (1.51-3.67) | 1.85 (1.14-2.99) | .012* |

| Rural | 63 | 122 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maternal educational level | |||||

| Had no formal education | 26 | 97 | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary education | 91 | 91 | 3.73 (2.21-6.28) | 3.67 (2.06-6.54) | .001 |

| Secondary education | 38 | 25 | 5.67 (2.92-11.03) | 4.28 (2.03-9.06) | .001* |

| Diploma and above | 29 | 13 | 8.32 (3.80-18.24) | 5.58 (2.31-13.45) | .001* |

| Gravidity | |||||

| Primigravida | 62 | 61 | 1.38 (0.90-2.10) | 1.30 (0.76-2.21) | .338 |

| Multigravida | 122 | 165 | 1 | 1 | |

| History of abortion | |||||

| Yes | 148 | 196 | 1.59 (0.94-2.70) | 1.68 (0.89-3.18) | .112 |

| No | 36 | 30 | 1 | 1 | |

| Trimester of pregnancy | |||||

| First | 16 | 44 | 1 | 1 | |

| Second | 102 | 126 | 2.23 (1.19-4.17) | 1.90 (0.91-3.96) | .087 |

| Third | 66 | 56 | 3.24 (1.65-6.36) | 3.43 (1.55-7.60) | .002* |

| History of vaginal bleeding | |||||

| Yes | 31 | 14 | 3.07 (1.58-5.96) | 3.25 (1.44-7.33) | .004* |

| No | 153 | 212 | 1 | 1 | |

| MDDS | |||||

| High | 64 | 41 | 5.99 (3.32-10.81) | 5.10 (2.63-9.89) | .001* |

| Medium | 95 | 89 | 4.10 (2.42-6.94) | 4.26 (2.35-7.71) | 9.001* |

| Poor | 25 | 96 | 1 | 1 | |

| Anemia status | |||||

| Non anemic (Hb ≥ 11 g/dl) | 139 | 133 | 2.16 (1.41-3.31) | 1.61 (0.95-2.71) | .079 |

| Anemic (Hb < 11 g/dl) | 45 | 93 | 1 | 1 | |

Significant at a P-value of less than .05.

The bold has been used to highlight significantly associated factors during analysis with the outcome variable.

Factors Associated With Adherence to Anemia Prevention Strategies

In bivariate analysis: maternal age, residence, maternal educational status, family size, gravidity, history of abortion, trimester of pregnancy, history of vaginal bleeding in the current pregnancy, MUAC, MDDS, anemia status of the mothers, and knowledge of anemia was significantly associated with anemia prevention at P-value of less than .2.

In multivariable analysis women who are found in the age group of 15 to 19 years (AOR = 2.66, 95% CI = 1.06-6.66), having secondary, and diploma and above educational level (AOR = 2.25, 95% CI = 1.08-4.70), and (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI = 1.39-4.11) respectively, primigravida women (AOR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.18-3.42), having less than two and 3 to 4 family size (AOR = 2.83, 95% CI = 1.38-5.78), (AOR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.01-2.91) respectively, second and third trimester of pregnancy (AOR 2.10, 95% CI = 1.05-4.18), (AOR = 3.67, 95% CI = 1.73-7.78) respectively, high MDDS (AOR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.07-3.75), knowledge of anemia (AOR = 2.54, 9% CI = 1.57-4.11) were significantly associated with adherence to anemia prevention strategies at a P-value of less than .05 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Logistic Regression Analysis for Maternal Adherence to Anemia Prevention Strategy Among Women Who Attended ANC in the Public Health Facilities of Pawi district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020, (n = 410).

| Variables | Adherence to anemia prevention strategies | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | ||||

| Age of the mother | |||||

| 15-19 | 28 | 12 | 2.80 (1.26-6.21) | 2.66 (1.06-6.66) | .037* |

| 20-24 | 68 | 61 | 1.34 (0.78-2.30) | 1.10 (0.58-2.09) | .764 |

| 25-29 | 80 | 73 | 1.32 (0.78-2.23) | 1.06 (0.57-1.96) | .851 |

| >30 | 40 | 48 | 1 | 1 | |

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 131 | 94 | 1.64 (1.11-2.43) | 1.33 (0.84-2.11) | .224 |

| Rural | 85 | 100 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maternal educational level | |||||

| Had no formal education | 41 | 82 | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary education | 106 | 76 | 2.79 (1.73-4.49) | 1.95 (0.86-4.44) | .111 |

| Secondary education | 42 | 21 | 4.00 (2.10-7.62) | 2.25 (1.08-4.70) | .031* |

| Diploma and above | 27 | 15 | 3.60 (1.73-7.50) | 2.39 (1.39-4.11) | .002* |

| Gravidity | |||||

| Primigravida | 85 | 38 | 2.66 (1.70-4.17) | 2.01 (1.18-3.42) | .010* |

| Multigravida | 131 | 156 | 1 | 1 | |

| History of abortion | |||||

| Yes | 40 | 26 | 1.47 (0.86-2.51) | 1.66 (0.89-3.08) | .108 |

| No | 176 | 168 | 1 | 1 | |

| Family size | |||||

| <2 | 60 | 22 | 3.72 (2.02-6.83) | 2.83 (1.38-5.78) | .004* |

| 3-4 | 109 | 104 | 1.49 (0.94-2.37) | 1.72 (1.01-2.91) | .045* |

| >5 | 47 | 67 | 1 | 1 | |

| Trimester of pregnancy | |||||

| First | 17 | 43 | 1 | 1 | |

| Second | 117 | 111 | 2.67 (1.44-4.95) | 2.10 (1.05-4.18) | .035* |

| Third | 82 | 40 | 5.19 (2.64-10.20) | 3.67 (1.73-7.78) | .001 * |

| History of vaginal bleeding | |||||

| Yes | 30 | 15 | 1.93 (1.01-3.70) | 1.56 (0.70-3.47) | .277 |

| No | 186 | 179 | 1 | 1 | |

| MDDS | |||||

| High | 66 | 39 | 2.76 (1.61-4.73) | 2.01 (1.07-3.75) | .030 * |

| Medium | 104 | 80 | 2.12 (1.33-3.39) | 1.70 (0.99-2.93) | .054 |

| Poor | 46 | 75 | 1 | 1 | |

| MUAC | |||||

| Normal (>23 cm) | 163 | 130 | 1.51 (0.98-2.33) | 1.36 (0.83-2.25) | .229 |

| Undernourished (≤22 cm) | 53 | 64 | 1 | 1 | |

| Anemia status | |||||

| Non anemic (Hb ≥11 g/dl) | 155 | 117 | 1.67 (1.11-2.53) | 1.03 (0.61-1.75) | .902 |

| Anemic (Hb <11 g/dl) | 61 | 77 | 1 | 1 | |

| Knowledge of anemia | |||||

| Good knowledge | 130 | 54 | 3.92 (2.59-5.94) | 2.54 (1.57-4.11) | .001* |

| Poor knowledge | 86 | 140 | 1 | 1 | |

Significant at a P-value of less than .05.

The bold has been used to highlight significantly associated factors during analysis with the outcome variable.

Discussion

Reducing anemia is recognized as an important component of the health of women and children. 31 The second global nutrition target was a 50% reduction of anemia among women of reproductive age by the year 2025. 1 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) focus on the reduction of the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births or no country has no more than 140 maternal mortality ratio, reducing neonatal deaths to 12 per 1000 live births, and under-five deaths to less than 25 per 1000 live births through eliminating preventable maternal, neonatal and child deaths by the year 2030. 32 In this study, 44.9% of the mothers had good knowledge of anemia. To achieve the above targets, it is needed to know the level of pregnant women’s knowledge of anemia and adherence to its preventive strategies.

In this study, 44.9% of the mothers had good knowledge of anemia. This finding is in line with studies done in southern Ethiopia (44.3%), 33 and Kathmandu, Nepal (48.7%). 34 However, the finding of our study is higher than studies done in Ghana 86.5%, 23 and Tanzania (65.0%) 35 had insufficient (low/fair) knowledge. The possible reason for the higher knowledge level of anemia in this study might be due to the time gap and increasing numbers of women who utilized maternity services from time to time. Because of this, they may get adequate information about anemia in the form of counseling or education.

On the other hand, this finding is lower than studies done in Harar, Ethiopia (61.0%), 27 West Shewa zone Ethiopia (57.3%), 30 Nigeria (68.9%), 36 Tamil Nadu, India (76.5%), 37 Pune, India (69.0%), 38 Baghdad (84.5%), 39 and Bangladesh (56.0% 40 had fair/good knowledge of anemia. The possible reason for this discrepancy in the knowledge of anemia among pregnant women might be the setting of the study area and the socio-economic characteristics of the study participants. The majority of these studies were conducted in town sitting and pregnant women from town sitting might have adequate information about anemia and because of this, they might become more knowledgeable. Furthermore, the result of our study is much lower than a study done in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia reported that 94% of the pregnant women had good knowledge of anemia. 41 This possible reason for this difference in the knowledge of anemia might be due to the difference in the socio-economic status and educational level of the study participants.

In our study, almost half (52.7%) of the women had good adherence to anemia prevention strategies. It is in line with a study done in the West Shewa zone, Ethiopia (50.0%). 30 It is also nearly consistent with the study done in Pune, India (59.5%) had good practices of anemia prevention. 38 However, it is lower than a study done in Nigeria (73.9%). 36 Moreover, this finding is higher than studies done in Harar, Ethiopia (41.4%), 27 Ghana (39.1%), 23 and Kathmandu, Nepal (34.0%) 34 had adherence to anemia prevention strategies. The possible reason for this difference in the adherence to anemia prevention strategies among pregnant women may be due to the difference in nutritional habits of the study participants.

Socio-demographic, obstetric, and nutritional-related factors were significantly associated with both the knowledge and prevention strategies of anemia. Our study shows that young aged pregnant women were more likely to have knowledge of anemia than women who are found in the age group greater than 30 years old. This finding is in contrast with a study done in Baghdad that shows women who are found in the age group of <25 years have poor knowledge of anemia. 39 The possible difference for this discrepancy might be the difference in the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. Additionally, in our study, the majority of the younger aged women had at least a primary educational level (72.7%) than women who are found in the age group of greater than 30 years (60.3%). Education is known to have the advantage of improving the knowledge of people regarding their health. This may account for the higher knowledge of anemia in young aged pregnant women. Additionally, pregnant women who were found in the age group of 15 to 19 years were more likely to have good adherence to anemia prevention strategies. This might have been because they become pregnant for the first time, and because of this, they may have good nutritional habits. They may also properly practice health care providers’ advice, like taking the IFAS regularly and avoiding using coffee, tea, or milk with their meals.

Having a secondary, and diploma and above an educational level increases the knowledge of anemia. This is supported by studies done in southern Ethiopia, 33 West Shewa zone, Ethiopia, 30 Ghana, 23 India, 42 Kathmandu, Nepal, 34 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 41 and Baghdad. 39 Similarly, secondary and diploma, and above educational level also increase the adherence to anemia prevention strategies by 2.25 and 2.39 times respectively. It agrees with studies done in the West Shewa zone, Ethiopia, 30 and India. 42 This could be explained by the fact that education increases access to getting information regarding health and nutritional habits. Pregnant women who lived in urban areas were 1.85 times more likely to know about anemia. This finding is consistent with a study done in the West Shewa zone, Ethiopia. 30 This could be due to the reason that pregnant women from urban areas might have adequate information about nutrition during pregnancy, as well as that having the more educational status of study participants and accessibility of health care facilities may contribute to their being more knowledgeable.

Women who have less than 2 and 3 to 4 family sizes were 2.83 and 1.38 times more likely to adhere to anemia prevention strategies than women who have greater than 5 family sizes. Moreover, primigravida pregnant women were 2.01 times more likely to adhere to anemia prevention strategies than multigravida women. This indicates that pregnant women who have lower family sizes and who become pregnant for the first time may have adequate supplies to feed their families and themselves. A family who has a good income was more likely to adhere to anemia prevention strategies. 38 Having a history of vaginal bleeding in a current pregnancy increases the knowledge of anemia by 3.25 times. Bleeding is one of the causes of anemia, and because of the bleeding, when pregnant women visit the health facility they may get information regarding the complication of the bleeding in the form of counseling and health education at the time of treatment.

Pregnant women who are found in their third trimester of pregnancy were 3.43 times more likely to know about anemia relative to those who are found in the first trimester of pregnancy. Similarly, pregnant women who are found in the second, and third trimesters of pregnancy were 2.10 and 3.67 times more likely to adhere to anemia prevention strategies than those who are found in the first trimester of pregnancy. The possible reason is that pregnant women who are found in their second and third trimesters of pregnancy may have more ANC visits than pregnant women who are in the first trimester of pregnancy. During the repeated ANC visits, they may get adequate information regarding anemia and its preventive methods during the ANC counseling sessions. This is supported by studies done in southern Ethiopia, 33 and Kathmandu, Nepal 34 showing that there is a significant relationship between knowledge of anemia and its prevention with the frequency of ANC visits.

Having medium and high MDDS increases the odds of knowing anemia by 4.26 and 5.10 times respectively. Similarly, pregnant women who have high MDDS were 2.01 times more likely to adhere to anemia prevention strategies than women who have poor MDDS. This indicates that pregnant women who have good knowledge of anemia may also have good dietary practices and prevention of anemia. There is supporting evidence from studies done in Ethiopia, 43 and America. 44 Women with good nutritional status have less risk of getting anima.45-47 Furthermore, women who had good knowledge of anemia were 2.54 times more likely to adhere to anemia prevention strategies. This is in line with studies done in the West Shewa zone, Ethiopia, 30 Ghana, 23 Pune, India, 38 and Iraq. 48 This indicates that pregnant women who know about anemia may also have adequate information about its prevention methods.

Strength and Limitations

This study used primary data to analyze both the knowledge of anemia and adherence to its prevention strategies in the public health facilities of the Pawi district, which increases the external validity of the study. But there was recall bias regarding requesting the MDDS. To avoid this recall bias, we tried to remind them to remember their eating habits before the pregnancy and during their current pregnancy.

Conclusions

In this study, the knowledge of anemia and its preventive strategies was low. Maternal socio-demographic, obstetrics, and nutritional-related factors were associated with maternal knowledge of anemia and its preventive strategies. It is important to continue to give information about the risk factors, signs and symptoms, and preventive methods of anemia for pregnant women when they use maternity and child health care services. Additionally, nutritional counseling on the consumption of iron-rich foods and awareness creation on the effects of taking coffee, tea, or milk with meals are highly recommended.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Department of Midwifery for allowing us to do this research. We would also like to extend our thanks to the Pawi district health office and health facilities staff for giving the necessary information. Moreover, we would like to thank the data collectors, supervisors, and study participants for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution: WFB, TE, AAT, and BAA were responsible for the conception of the research idea, study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and supervision. WFB and TE participated in the data collection, entry, analysis, and manuscript write-up. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement: All related data have been presented within the manuscript. The data set supporting the conclusion of this article is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Bahir Dar University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences with Institutional Review Board protocol number 0061/2020. Permission letters were received from each health facility. The study was conducted according to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. Confidentiality was kept by using anonymous codes and de-identified study participants’ identifiers. All respondents were assured that the data would not have any negative consequence on any aspects of their life.

Informed Consent: Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects before data collection.

ORCID iD: Wondu Feyisa Balcha  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7639-3363

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7639-3363

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global nutrition targets 2025: anemia policy brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.4). World Health Organization, 2014. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://apps.who.int . . .. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Serum and Red Blood Cell Folate Concentrations for Assessing Folate Status in Populations. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The Global Prevalence of Anemia in 2011. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassa GM, Muche AA, Berhe AK, Fekadu GA.Prevalence and determinants of anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia; a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Hematol. 2017;17(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The Global Prevalence of Anemia in 2011. WHO; 2015:2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. WHO global database on vitamin a deficiency. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bothwell TH.Iron requirements in pregnancy and strategies to meet them. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(1):257S-264S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallberg L, Rossander-Hultén L.Iron requirements in menstruating women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(6):1047-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee SWRT. Regional Template/Guideline for the Management of Anemia in Pregnancy and Postnatally. South West RTC Management of Anemia in Pregnancy. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Guideline: daily iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnant women. World Health Organization; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ephi I.Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. EPHI and ICF; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanamala VG, Rachel A, Pakyanadhan S.Incidence and outcome of anemia in pregnant women: a study in a tertiary care centre. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2018;7(2):462-466. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frayne J, Pinchon D.Anaemia in pregnancy. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48(3):125-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adam I, Ibrahim Y, Elhardello O.Prevalence, types and determinants of anemia among pregnant women in Sudan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Hematol. 2018;18(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimiywe J, Ahoya B, Kavle J, Nyaku A.Barriers to Maternal Iron_Folic Acid Supplementation & Compliance in Kisumu and Migori, Kenya. USAID Maternal and Child Survival Program; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aderoba AK, Iribhogbe OI, Olagbuji BN, Olokor OE, Ojide CK, Ande AB.Prevalence of helminth infestation during pregnancy and its association with maternal anemia and low birth weight. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;129(3):199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Özaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV.Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2123-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morey SS.CDC issues guidelines for prevention, detection and treatment of iron deficiency. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(6):1475-1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Strategies to Prevent Anemia: Recommendations from an expert group consultation, New Delhi, India, December5-6, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acheampong K, Appiah S, Baffour-Awuah D, Arhin YS.Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of a selected hospital in Accra, Ghana. Int J Health Sci Res. 2018;8(1):186-193. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbule MA, Byaruhanga YB, Kabahenda M, Lubowa A.Determinants of anaemia among pregnant women in rural Uganda. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13(2):2259-2315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Appiah PK, Nkuah D, Bonchel DA.Knowledge of and adherence to anaemia prevention strategies among pregnant women attending antenatal care facilities in Juaboso district in Western-north region, Ghana. J Pregn. 2020;2020:2139892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Insecticide-Treated Nets Reduce the Risk of Malaria in Pregnant Women. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009. Apr;12(4):444-54. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002401. Epub 2008 May 23. PMID: 18498676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ababa A.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions at Wereda Level From 2014–2017. Central Statistical Agency; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oumer A, Hussein A.Knowledge, attitude and practice of pregnant mothers towards preventions of iron deficiency anemia in Ethiopia: Institutional Based Cross Sectional Study. Health Care Curr Rev. 2019;07(01):1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abriha A, Yesuf ME, Wassie MM.Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women of Mekelle town: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):888-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FAO. Minimum dietary diversity for women: a guide for measurement. FAO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayanthigopal M, Demisie MDB. Assessment of knowledge and practice towards prevention of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care at government hospitals in West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing, 2018;50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Global Anemia Reduction Efforts Among Women of Reproductive Age: Impact, Achievement of Targets and the Way Forward for Optimizing Efforts. World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duko B, Tadesse B, Gebre M, Teshome T.Awareness of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care, South Ethiopia. J Womens Health Care. 2017;06:409. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghimire N, Pandey N.Knowledge and practice of mothers regarding the prevention of anemia during pregnancy, in teaching hospital, Kathmandu. J Chitwan Med Coll. 2013;3(3):14-17. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margwe JA, Lupindu AM.Knowledge and attitude of pregnant women in rural Tanzania on prevention of Anaemia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2018;22(3):71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ademuyiwa IY, Ayamolowo SJ, Oginni MO, Akinbode MO.Awareness and Prevention of Anemia Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic at a University Teaching Hospital In Nigeria. Calabar J Health Sci. 2020;4(1):20-6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balasubramanian T, Aravazhi M, Sampath SD.Awareness of anemia among pregnant women and impact of demographic factors on their hemoglobin status. Int J Scient Study. 2016;3(12):303-305. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivapriya S, Parida L.A study to assess the knowledge and practices regarding the prevention of anemia among antenatal women attending a tertiary-level hospital in Pune. IJSR NET. 2015;4(3):1210-1214. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Sattam Z, Hassan S, Majeed B, Al-Attar Z.Knowledge about anemia in pregnancy among females attending primary health care centers in Baghdad. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2022;10(B):785-792. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizwan AAM, Hasan F, Huda MS, Talukder N, Siddique RAH, Anwar A, et al. Knowledge and attitude on anemia among the women attending a government tertiary level hospital at cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Res. 2021;10(12):84-94. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alosaimi AA, Alamri SA, Mohammed M. Dietary knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding prevention of iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced Nursing Studies. 2020;9 (1): 29-36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yadav RK, Swamy M, Banjade B. Knowledge and Practice of Anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Dr. Prabhakar Kore hospital, Karnataka-A Cross-sectional study. Literacy. 2014;30:34-18. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alemayehu MS, Tesema EM.Dietary practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Gondar Town North West, Ethiopia, 2014. Int J Nutr Food Sci. 2015;4(6):707-712. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Latifa M, Manal H, Nihal S.Nutritional awareness of women during pregnancy. J Am Sci. 2012;8(7):494-502. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abay A, Yalew HW, Tariku A, Gebeye E.Determinants of prenatal anemia in Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2017;75(1):51-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okube OT, Mirie W, Odhiambo E, Sabina W, Habtu M. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in the second and third trimesters at Pumwani maternity hospital, Kenya. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;6:16-27. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Argaw D, Hussen Kabthymer R, Birhane M.Magnitude of anemia and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Blood Med. 2020;11:335-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.AlAbedi GA, Arar AA, Alridh MSA. Assessment of pregnant women knowledge and practices concerning iron deficiency anemia at Al-Amara City/Iraq. Med Leg Update. 2020;20(3):151. [Google Scholar]