Highlights

-

•

Phosphoprotein phosphatases are members of the PPP sequence family.

-

•

PPP sequence family enzymes share their most recent common ancestry with the metallophosphoesterases.

-

•

We uncover key sequence changes in the transition from metallophosphoesterase to bacterial PPPs.

-

•

We trace the evolution of the substrate binding “2-Arginine Clamp”.

Keywords: Protein phosphatase, Metallophosphoesterase, Phylogenetic analysis, Molecular dynamics simulation, Bacterial origin, Phosphomonoesterase

Abstract

Background

Phosphoprotein phosphatases (PPP) belong to the PPP Sequence family, which in turn belongs to the broader metallophosphoesterase (MPE) superfamily. The relationship between the PPP Sequence family and other members of the MPE superfamily remains unresolved, in particular what transitions took place in an ancestral MPE to ultimately produce the phosphoprotein specific phosphatases (PPPs).

Methods

We use structural and sequence alignment data, phylogenetic tree analysis, sequence signature (Weblogo) analysis, in silico protein-peptide modeling data, and in silico mutagenesis to trace a likely route of evolution from MPEs to the PPP Sequence family. Hidden Markov Model (HMM) based iterative database search strategies were utilized to identify PPP Sequence Family members from numerous bacterial groups.

Results

Using Mre11 as proxy for an ancestral nuclease-like MPE we trace a possible evolutionary route that alters a single active site substrate binding His-residue to yield a new substrate binding accessory, the “2-Arg-Clamp”. The 2-Arg-Clamp is not found in MPEs, but is present in all PPP Sequence family members, where the phosphomonesterase reaction predominates. Variation in position of the clamp arginines and a supplemental sequence loop likely provide substrate specificity for each PPP Sequence family group.

Conclusions

Loss of a key substrate binding His-in MPEs opened the path to bind novel substrates and evolution of the 2-Arg-Clamp, a sequence change seen in both bacterial and eukaryotic phosphoprotein phosphatases.

General significance: We establish a likely evolutionary route from nuclease-like MPE to PPP Sequence family enzymes, that includes the phosphoprotein phosphatases.

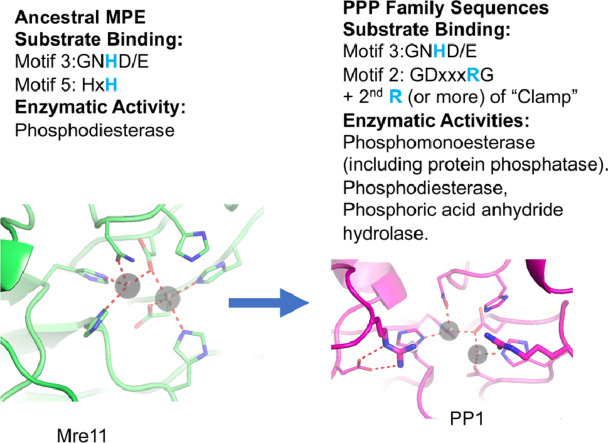

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Reversible covalent modification of proteins is recognized as a simple means to control their function, either through altering enzyme properties, changing subcellular location, controlling degradation or altering protein-protein interactions [1]. The prevalence of protein covalent modifications has only come to light in the age of mass spectrometry and proteomics. It is now widely accepted that human proteins are highly modified with many thousands of modification sites now mapped [2,3]. Of these modifications, protein phosphorylation is most common and is known to occur on a minimum of 75% of the human proteome [3]. The protein phosphorylation machinery (protein kinases and phosphatases) has expanded in metazoans, with the protein kinase superfamily being one of the largest gene families in multicellular organisms [4,5]. The recognized prevalence of protein covalent modifications in Eukaryotes and the growth of tools available to perform proteomics and genomics have led to a re-examination of these modifications in non-eukaryotic species (Archaea and Bacteria). These studies have uncovered a previously unrecognized abundance of archaeal and bacterial protein modifications [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. The molecular machinery related to the eukaryotic enzymes needed for protein serine, threonine and to some extent tyrosine (de)phosphorylation, including the protein phosphatases, appears to be present in many non-eukaryotic species. These recent advances highlight the need for better understanding of the evolutionary origin of protein phosphorylation in Bacteria, particularly its control and regulation by dephosphorylating enzymes.

In Eukaryotes, serine/ threonine dephosphorylation is dominated by the Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent type 2C protein phosphatases (PPM) and phosphoprotein phosphatases (PPP). Recently we explored the evolution of the PPM sequence family and found evidence strongly suggesting that this group originated in Bacteria, arriving in Eukaryotes with the mitochondrial endosymbiosis [12]. The PPPs belong to the larger PPP Sequence Family, and this family belongs to the broader metallophosphoesterase (MPE) (also called metallophosphatase (MPP)) superfamily. These all share a common fold, consisting of a double beta-sheet sandwich that coordinates two divalent metal ions in the active site [13]. In addition to the PPP Sequence Family, this broader superfamily (MPE) includes phospholipases, exonucleases, RNA lariat debranching enzymes, cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, and purple acid phosphatases [14].

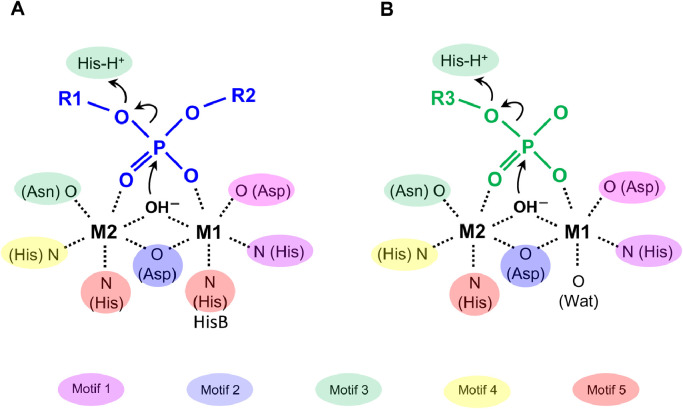

The two divalent metal ions comprise an essential catalytic element common to all MPEs that fulfills at least three critical functions. First, they coordinate to an hydroxide ion, stabilizing the activated, deprotonated state to form a strong nucleophile. Second, the divalent metal ions coordinate to oxygen atoms of the substrate phosphoryl group, positioning the phosphorus atom electrophile close to the oxygen atom of the hydroxide ion for nucleophilic attack. Third, the positively charged divalent metal ions electrostatically stabilize the buildup of negative charge in the high-energy transition state. The importance of these three elements for catalyzing the hydrolysis of the wide range of phosphate monoester and diester substrates processed by MPEs helps to explain the universal requirement for the pair of divalent metal ions at the active sites of MPEs. A generalized phosphodiesterase reaction catalyzed by many MPEs (Panel A) and the phosphomonoesterase reaction catalyzed by many PPP Sequence Family members (Panel B) is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagrams showing the reactions catalyzed by phosphomonoesterase, phosphodiesterase and phosphoric acid anhydride hydrolase enzymes. The approximate spatial arrangement of (A) phosphoric acid diester or phosphoric acid anhydride substrates (blue lines and letters) and (B) phosphoric acid monoester substrates (green lines and letters) bound to the divalent metal ions (M1 and M2), as well as key enzyme residues, water molecule and the activated hydroxide ions at the active sites are shown. The atoms in the side chains from the highly conserved residues of metallophosphoesterase (MPE) and PPP sequence family enzymes coordinating to the divalent metal ions are coloured according to the highly conserved sequence motifs 1–5 and discussed in the text. HisB refers to the second His-of motif 5 of MPEs (GHxH). Curved arrows indicate the flow of electrons occurring during the nucleophilic substitution reactions. Dashed lines indicate metal ion coordination bonds.

Following the breakdown of the high energy transition state, an alcohol leaving group is produced by all MPEs, with the second product being either a free phosphate anion for phosphomonoesterases or a phosphate monoester for phosphodiesterases. The specificity of individual MPEs for substrates containing phosphate monoesters versus diesters is only partially understood, with some structural evidence for the roles of secondary elements adjacent to the divalent metal ion binding site in forming binding interactions specific for the additional groups present in a phosphodiester substrate and perhaps preferentially stabilizing the formation of a phosphate group in phosphomonesterases as opposed to the phosphate monoester product in phosphodiesterases [14]. Elegant studies of the alkaline phosphatase family of MPE phosphomonoesterases and phosphodiesterases indicate that the introduction of a variety of accessory structural elements into multiple distinct ancestral enzyme architectures can alter enzyme specificity for phosphate monoesters versus phosphate diesters, as well as for other types of substrates, e.g., sulfate esters [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Such findings suggest that the evolution of similar enzyme specificities within the alkaline phosphatase family has arisen from multiple ancestral forms through the incorporation of a variety of distinct modifications that converge to achieve similar functional effects on specificity. Structure-function relationships between phosphomonoesterase-specific PPPs and other branches of the MPE superfamily appear to reflect in part the modification of ancestral forms to confer specificity for phosphoserine, phosphothreonine and phosphotyrosine phosphate monoester substrates over cyclic and linear phosphate diesters.

Sequences similar to eukaryotic PPPs have been described in both Bacteria and Archaea. Comparisons based on relatively small datasets have led to the proposal that the phosphoprotein phosphatases are ancient, perhaps having arisen in the last common ancestor of all cellular life [14,[20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. The precise relationship between the PPP Sequence Family (which the phosphoprotein phosphatases belong) and other members of the far-flung MPE superfamily remains unresolved.

We assemble previously published and original structural and sequence alignment data, in silico protein-peptide modeling data, and in vitro mutagenesis data to show that model PPPs (phage lambda phosphatase and eukaryotic PP1) use a set of two spaced Arg-residues to bind substrate in a “2-Arginine Clamp”. This is a substrate binding mode distinct from that used by MPEs. We simulate substrate binding with a proxy structure for an ancestral nuclease-like MPE (Mre11), then utilize in silico mutagenesis to reveal how substitutions at a critical substrate binding residue may have opened up an evolutionary pathway which led to the PPP Sequence Family.

We next utilized Hidden Markov Model (HMM) based iterative database search strategies to assemble candidate sequences for various bacterial sequence groups within the PPP Sequence Family and demonstrate that they have a widespread distribution within Bacteria. We show that the presence of a “2-Arginine Clamp” is a ubiquitous feature within these various sequence classes and using sequence variants infer the pattern of radiation of this sequence family within Bacteria. Finally, we reconcile the possible position of putative clamp residues within sequence alignments with their active site placement within solved or homology modeled structures. We find that a supplementary sequence loop containing one of the clamp Arg-residues is a common feature of many bacterial PPP Sequence Family members, and also eukaryotic members such as PP1.

Results

“Phosphoprotein phosphatases” (PPPs) use a “2-Arginine clamp” to bind substrate

Henceforth in this report we will restrict the term “Phosphoprotein Phosphatases” (PPPs) to those proteins from Bacteria and Eukaryotes which have been biochemically characterized and which cleave phosphomonoester bonds in phosphorylated amino acids (p-Ser, p-Thr, p-Tyr) in protein and peptide substrates. These are members of a broader family defined by patterns of sequence similarity, collected in the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) as cd00144 (MPP_PPP_Family), which we will term here the “PPP Sequence Family”. This is in turn part of the even broader cd00838 (MPP or MPE) superfamily. We have recently characterized a novel eukaryotic PPP from Arabidopsis (AtRLPH2) which preferentially dephosphorylates p-Tyr-residues [25]. AtRLPH2 is a “Rhizobiales/Rhodobacterales/Rhodospirillaceae-like Phosphatase”, a descendant of the bacterial RLPH sequence family which entered Eukaryotes with the mitochondrial endosymbiosis [26]. We have also determined the crystal structure of AtRLPH2 [27] and through mutagenesis experiments showed the importance of two conserved Arg-residues (Arg51, Arg245) to the phospho-tyrosine phosphatase activity. The likely importance of similar pairs of spaced Arg-residues to substrate binding has previously been recognized in the solved structures of eukaryotic PP1 [28]), PP5 [29] and the phage lambda phosphatase [30]. We first sought to examine how general these sequence features might be by examining the solved structures of other bacterial and eukaryotic PPPs. We used the structure of AtRLPH2 as a query in DALI to search the PDB ID, and obtained a structural alignment with CAPTP (cold-active protein tyrosine phosphatase of Shewanella [31], the effector WipA of Legionella [32], the bacteriophage lambda phosphatase [30], PP1 [33], PP2A [34] and PP5 [35]. A structure-guided alignment containing all of these sequences is presented as Supplemental Figure S1 (the corresponding FASTA formated alignment is available as Supplemental File S1). The set of six sequence motifs typically conserved in PPPs [36,37] are labeled. An Arg-residue conserved in all the sequences is present in Motif 2 (downward arrow). Domain 3, which extends between sequence Motif 4 and Motif 5, contains two further conserved Arg-residues. The first (downward arrow) is conserved in sequences from Bacteria. The second (upward arrow) is conserved in the eukaryotic sequences (PP1, PP2A, PP5). The latter is situated in what is predicted to be a sequence loop which is not present in the bacterial sequences. Mutagenesis experiments published by our laboratory and by others (summarized in Supplemental Table S1) have shown that changes to one or the other of these two conserved Arg-residues in both bacterial and eukaryotic proteins have substantial effects on enzymatic activity. This combination of sequence/structure and biochemical evidence suggests that the presence of a “2-Arginine Clamp”, composed of conserved residues in Motif 2 and between Motif 4 and Motif 5, is important for the PPP reaction.

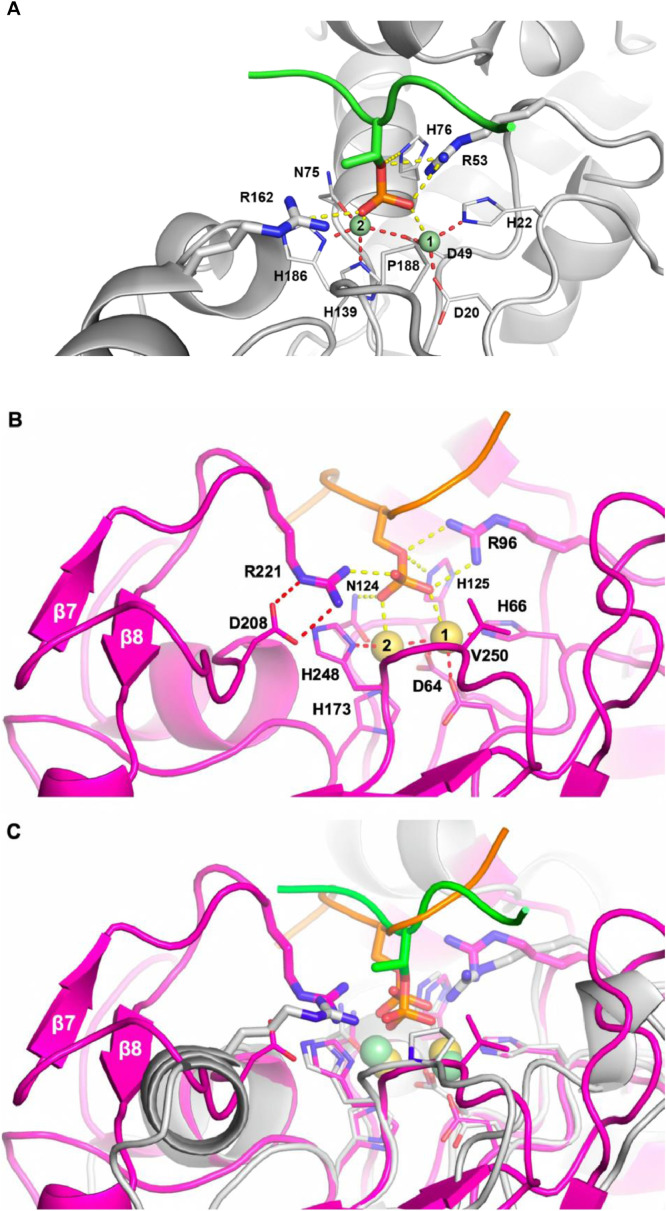

We next sought to test the hypothesis of substrate binding by the “2-Arginine Clamp” by using in silico docking and molecular dynamic simulation with the solved structure of either the phage lambda phosphatase or eukaryotic PP1 together with a phosphorylated peptide substrate. The results are summarized in Fig. 2. In the phage lambda phosphatase (Panel A) the substrate phosphate group is bracketed by interactions between R53 (Motif 2) and R162 (between Motif 4 and Motif 5). In human PP1 (Panel B) the corresponding interactions occur between R96 (Motif 2) and R221 (between Motif 4 and Motif 5). In each case these are the same pair of residues implicated in substrate binding through previous analysis of solved structures [28,30]. The sequence loop predicted by the alignment in Supplemental Figure S1 (dashed line) is readily apparent when the bacterial and eukaryotic structures are superimposed (Panel C). This includes the secondary structure elements β7 and β8 of the PP1 sequence. The clamp Arg162 of the lambda phosphatase is spatially equivalent to Asp208 of PP1 (Panel C), which is also predicted by the previous sequence alignment. The second clamp residue in PP1 is Arg221, whose side chain residues nearly precisely replicate the placement seen in the clamp residue Arg162 in the lambda phosphatase. In PP1, Asp208 interacts with Arg221 (Panel B), an interaction important in stabilizing its position, as pointed out previously in the analysis of the solved PP1 structure [28]. These data confirm the postulated role of the “2-Arginine Clamp” residues in substrate binding in both PPPs and indicate the importance of a supplemental sequence loop in the Eukaryotic PP1 structure.

Fig. 2.

Structural models of PPP enzymes with phosphorylated substrate peptides. Panel A: A combination of molecular docking and MD simulation, as detailed in Methods, was used to refine a structural model of the phage lambda phosphatase (PDB ID:1G5B) and a peptide containing the sequence “RRA(pT)VA”. A stable conformation of the peptide was first produced by MD simulation. The protein binding pocket is shown in a cartoon mode (gray), while the phosphorylated residue is shown in a stick mode. The metals present in the active site (“M1” and “M2”) are shown in CPK mode (green spheres). In the model these are Zn2+ (see Methods). The metal coordination interactions are illustrated by the red dashed lines. Protein-substrate interactions are shown as yellow dashed lines. The side chains of residues involved in the “2-Arginine Clamp” discussed in the text (Arg53 and Arg162) are shown in a stick mode for clarity and emphasis. Panel B: Structural model of human protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (PDB ID:3E7B) and a phopsho-peptide containing the sequence “11KQIpSVRG17” derived from the classic PP1 substrate human glycogen phosphorylase-a (PDB ID: 1Z8D). The protein is shown in a cartoon mode (pink), the phosphorylated residue in stick mode. The metals within the active site (“M1” and “M2”) are shown as CPK spheres (yellow). In the model these are Zn2+ (see Methods). Metal coordination interactions are illustrated by dashed lines. Protein-substrate interactions are shown as yellow dashed lines. The side chains of residues involved in the “2-Arginine Clamp” discussed in the text (Arg96 and Arg221) are represented as sticks for clarity and emphasis. Panel C: Superposition of structural models for phage lambda phosphatase (1G5B, gray) and human protein phosphatase PP1 (3E7B, pink) with their respective substrate peptides.

The “PPP sequence family” is nested within the “MPE superfamily”

PPPs such as the phage lambda phosphatase and PP1 are placed by patterns of sequence similarity into the broader group which we call here the “PPP Sequence Family”. We will be focusing for the remainder of this report on the bacterial members of this family which are gathered into the following groups at NCBI CDD: cd07413 (PA3087), cd07421 (Rhilphs), cd07422 (ApaH), cd07423 (PrpLike), PrpA-PrpB (cd07424), and Shelphs (cd07425). We will henceforth use the sequences and nomenclature for the “Rhizobiales-Like Phosphatases” (RLPH) and “Shewanella-Like Phosphatases” (SLP) which we have previously characterized [36] and which we will present in later sections. Both of these sequence groups, though possessing numerous eukaryotic representatives, have evolved from bacterial ancestors. Representatives of some of the other PPP Sequence Family members have been examined and their biochemical characteristics presented – they are by no means all active as protein phosphatases, with some likely having novel phospho-substrates. In this report we will be concerned primarily with their patterns of sequence evolution. As mentioned above, the entire PPP Sequence Family is one member of a larger assemblage of sequences which share a common protein fold, and which are collectively called MPEs (metallophosphoesterases) or MPPs (metallophosphatases). These comprise a collection at NCBI CDD under the heading cd00838 (MPP_superfamily).

MPEs bind substrate differently than PPPs

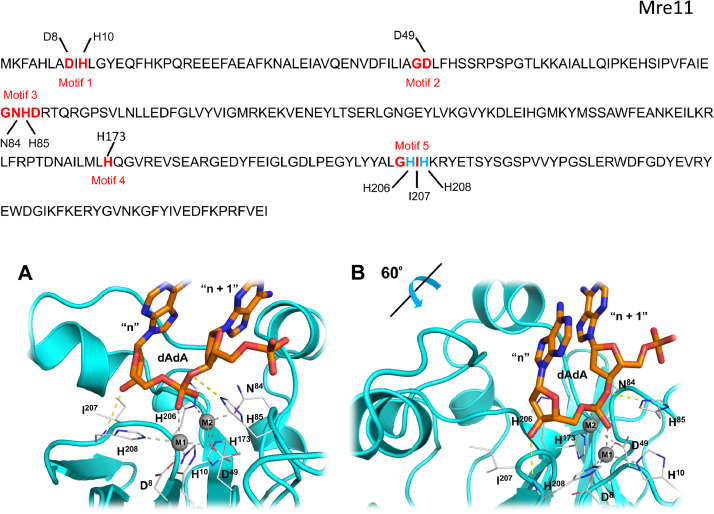

Evidence from our sequence/structure alignments and in silico analyses, presented above, in addition to the previous structural and biochemical work by others that we cite, together have established the importance of a “2-Arginine Clamp” for enzyme substrate interaction amongst PPPs. Our chief aims in the remainder of this report will be: first, to establish how this mode of enzyme-substate interaction might have evolved in bacterial sequences; and second, how widespread it may be among members of the broader PPP Sequence Family. As a baseline for that effort it is important to consider briefly how an important class of MPE (which we will show later is likely of an ancestral type) interacts with substrate. Such a protein would be exemplified by the DNA repair nuclease Mre11. This protein has neither of the two Arg-clamp residues seen in the PPPs. Instead, substrate is contacted and bound in part between two prominent residues: a His-at Motif 3 and a His-at Motif 5. In fact, it is the second of two His-residues [GHxH] at Motif 5 (which we will refer to as HisB) which assists in binding substrate [38] (see Fig. 1, Panel A and Fig. 3) while the first His-aids in metal ion binding [13]. These characteristics are shared by other related MPEs. The substrate interaction utilizing a conserved His-at Motif 3 has been retained through evolution by the PPPs (see His76 in the phage lambda phosphatase interacting with the substrate phosphate group in Fig. 2A). However, the MPE HisB residue at Motif 5 has been lost in PPP Sequence Family enzymes, and with it this mode of substrate interaction. The “2-Arginine Clamp” evolved to serve in this role instead. We will begin next to trace this transition from ancestral MPE to descendant PPP Sequence Family architecture.

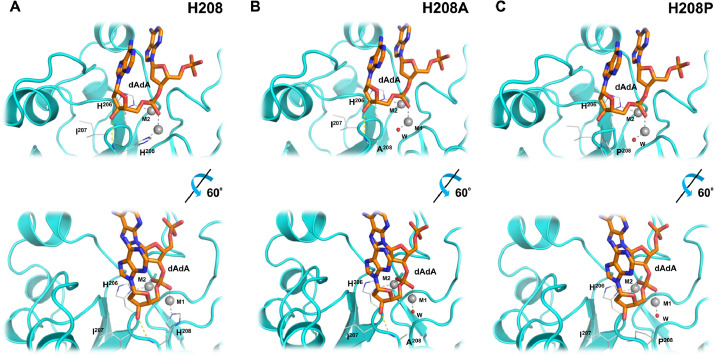

Fig. 3.

Sequence, motifs and models of Mre11 with substrate dAdA. The amino acid sequence of P. furiosus Mre11 is shown above the two panels. Key amino acids from each of the 5 MPE motifs is indicated and corresponds to the residues shown in panels A and B. Panel (A): Mre11:dAdA complex was generated through homology modeling by using the structure of Mre11 with bound dAMP (PDB ID: 1II7) as a starting model (see Methods). Metal ions (“M1” and “M2”) are represented in CPK sphere mode. These ions were Zn2+ in the modeling process (see Methods). Protein-metal ion coordination interactions are shown as dashed gray lines. Key hydrogen bonds between the protein (side chain of His85 in Motif 3 and backbone carbonyl of His208 in Motif 5) and bound ligand are shown as yellow dashed lines. A view rotated 60° with respect to this image is shown in Panel (B). The terminal nucleotide (“n”) corresponds to the dAMP in the solved structure complex with the nuclease Mre11 (PDB ID:1II7). The penultimate nucleotide (“n + 1”) corresponds to the upstream portion of a linear polynucleotide substrate.

Strategic mutations open a path for evolution of the PPP sequence family

A recent review of the MPE superfamily [14] noted that DNA repair proteins and phosphoprotein phosphatases (PPPs) are very widespread, and found across all domains of life, including viruses. This implies that both these structural and functional groups have ancient origins. In the Evolutionary Classification of Protein Domains (ECOD) database [39] (http://prodata.swmed.edu/ecod/) the Family “Metallophos_2_1” includes structures for a variety of PPP Sequence Family members and the DNA double-strand break repair nuclease Mre11. Metange et al. [14] also noted that in conserved sequence Motif 5, the second His (GHxH, or HisB) of MPEs is altered to A/P/V/L/I in PPP Sequence Family members with unknown consequences. We examined the issue of the composition of Motif 5 in MPEs vs PPP Sequence Family members by comparing sequences from a large starting set presented in Supplemental Table 2. We constructed a multiple sequence alignment as detailed in Methods, which is presented as Supplemental Figure 2. It can be readily seen that HisB of Motif 5 (green boxed region) is very widespread amongst MPE sequence groups but lacking in the members of the PPP Sequence Family aligned above them. In particular, HisB is conserved in the cd00840 group, which includes Mre11. Based on these initial observations, we resolved to examine in more detail the structure and substrate interactions of Mre11 (1II7) and the possible implications of substitution at the HisB position of Motif 5 and acquisition of a substrate binding “2-Arginine Clamp” for the evolution of the PPP Sequence Family.

The structure of the exonuclease Mre11 contains a bound dAMP (dA), corresponding to a terminal nucleotide product (“nucleotide n”) following its hydrolysis from a linear polynucleotide substrate. The conserved second His-in Motif 5 of Mre11 (His208) has two roles: its side chain ring helps coordinate Metal 1 at the active site (see Panel A, Fig. 1 and Fig. 3), and its backbone N forms a hydrogen bond with the 3′ oxygen of the dAMP (this would correspond to the downstream portion (nucleotide “n”) of a dinucleotide substrate (nucleotide “n + 1”, nucleotide “n”). This interaction is thought to stabilize the substrate in the binding pocket.

As noted above, a recent review reported that the ancestral second His-position in Motif 5 (HisB) is replaced by various substitutions (H to A/P/V/L/I) in PPP Sequence Family members, with unknown functional consequences [14]. Our sequence alignment data confirm this observation and extend it to a broader set of residues. We modeled the effects of these substitutions on the behavior of the Mre11-dAdA complex, as a proxy of a nuclease-like MPE ancestor of the PPP Sequence Family, by residue replacement followed by energy minimization to attain a stable conformation (Supplemental Figure S3). Our results are presented as Supplemental Table S3, and a subset of them graphically as Fig. 4. We assessed three parameters: coordination of Metal 1 at the catalytic center; hydrogen bonding between the protein and the 3′-oxygen of the terminal dA residue (nucleotide “n”); and possible steric interference between the protein and the substrate. Substitution of Tyr-at position 208 leads to a steric clash and a loss of coordination of Metal 1. We infer that a Tyr-substitution in Mre11 or an ancestral nuclease-like MPE might have led to loss of enzymatic activity secondary to metal loss. The substitution of Ala, Gly, Ser, or Cys-leads to insertion of a water molecule coordinating Metal 1, and likely the retention of an enzymatically competent conformation. In addition, hydrogen bonds are predicted to be formed between the protein and the substrate to help stabilize binding, and no steric clashes are expected between the protein and the substrate. In combination, then, we infer that substitution of these residues could be tolerated without significant changes in the substrate specificities and enzymatic activities of these ancestral proteins (nuclease-like MPEs). The substitution of Pro-would allow for the insertion of a water molecule, full coordination of Metal 1, and thus presumably an enzymatically active conformation. However, significantly, we predict that this substitution would result in loss of hydrogen bonding between the protein and the 3′-oxygen of the terminal deoxynucleotide with polynucleotide substrates, likely preventing substrate docking to the protein. To explore this further we used MD simulation and the MM-PB(GB)SA method to estimate binding enthalpy for the substrate dAdA binding Mre11 and Mre11 with His208 changed to Ala-or Pro (Table 1). Remarkably, the MM-PB(GB)SA method estimated 90 or 76 and 9565 or 8097-fold increases in Km for the Ala208 and Pro208 versions of Mre11, respectively. We infer therefore, that the presence of one of these substitutions, in particular Pro, in a nuclease-like ancestral MPE could favor the binding of alternative substrates, hence opening a new evolutionary path which could have ultimately led to the PPP Sequence Family, all of which lack HisB in Motif 5.

Fig. 4.

Effects of residue substitution variants for His208 in the complex of Mre11 with a deoxyadenosine dinucleotide (dAdA) ligand. Mre11:dAdA complex was generated through homology modeling by using the structure of Mre11 with bound dAMP (PDB ID: 1II7) as a starting model (see Methods). (Fig. 3). This Figure illustrates a subset of stable structures observed for His208 substitutions listed in Supplemental Table S3 in comparison to the original structure featuring His208. Metal ions (”M1” and “M2”) are represented as gray spheres. These ions were Zn2+ in the modeling process (see Methods). Protein-metal ion coordination interactions are represented as dashed gray lines. The position of a water molecule coordinating Metal 1 is shown by a red sphere and labeled as “W”. Key hydrogen bond interactions between the protein and ligand are represented as yellow dashed lines. In Panel C the H-bond between amino acid 208 and the substrate is lost between the dAdA ligand and the substituted Pro-side chain.

Table 1.

Impact of H208X mutation on enthalpy of dAdA binding to Mre11.

| Mre11 | ΔHo (kcal/mol) | ΔΔHo (kcal/mol) | Km (mut) / Km (wt) |

|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type | −24.6/ −24.9 | – | – |

| H208A | −21.9/ −22.3 | 2.7/ 2.6 | ~90/ ~76 |

| H208P | −19.1/ −19.5 | 5.5/ 5.4 | ~9565/ ~8097 |

The binding enthalpies for each system are reported from two independent calculations performed with Molecular-Mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann Solvent Accessible Area (MM-PBSA) and Molecular-Mechanics/Generalized Born and Surface Area (MM-GBSA) methods, respectively. The change in binding enthalpy relative to wild-type (WT) due to mutation (ΔΔHo) was used to estimate the effect on Km for substrate dAdA.

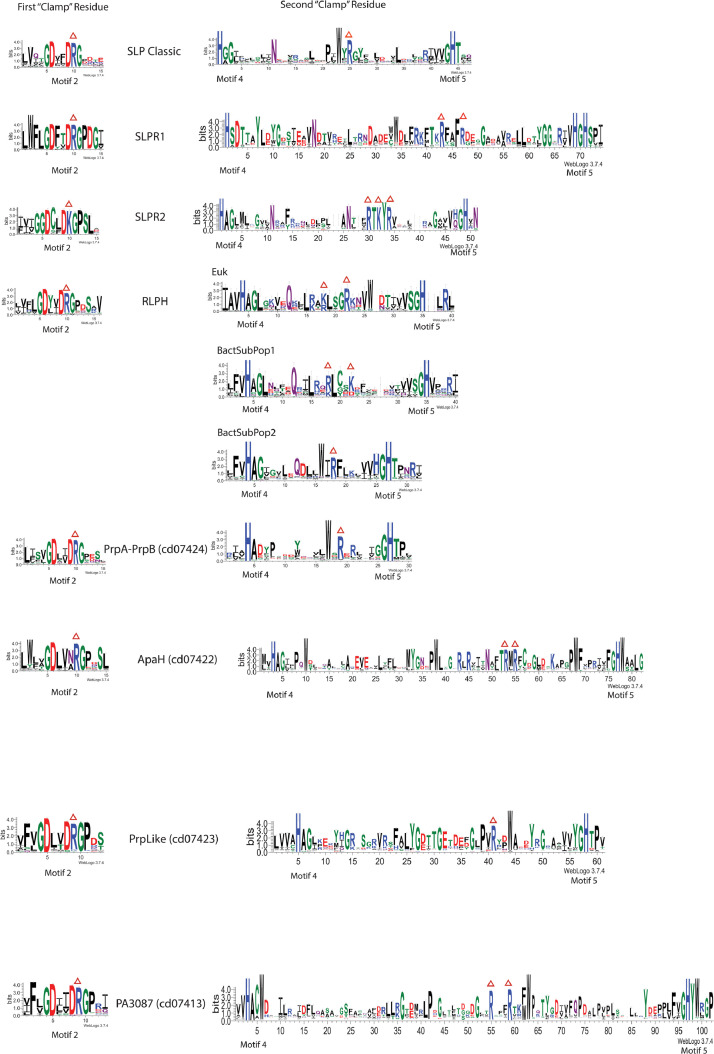

In the sections below we will explore the evolution of the substrate binding “2-Arginine Clamp” whose appearance correlates with the loss of the second His-in Motif 5 (HisB) in PPP Sequence Family members. This is presented visually as WebLogos (Fig. 5) derived from Motif 2 and sequences spanning Motif 4 to Motif 5 of PPP Sequence Family members. We will use that information here, in combination with the underlying alignments of PPP Sequence Family members used for tree analysis (Supplemental Figures S4–16) to first explore the altered HisB residue of Motif 5 in these sequences. As shown in Fig. 5, a variety of amino acids can occupy the HisB position (GHxH) of PPP Sequence Family members, with Pro, Ala, Val-and Ile-being common, and Pro-being predominant. Among the RLPH proteins, phylogenetic analysis (Supplemental Figures S12, S13) indicates that the bacterial RLPH variants and RLPH subpopulation 2 are most basal with all members having Pro-in the HisB position, while the most derived member (Eukaryotic RLPH) has Gly (Supplemental Figures S12, S13). For the PrpLike protein the overall percentage of Pro-in Motif 5 in the WebLogo alignment is 93%. Thus, it would be reasonable to propose that the PrpLike group retained the ancestral Pro-character at HisB of Motif 5. With the exception of the member group we call ‘basal variants’ (Supplemental Figures S10, S11), PrpA-PrpB is most basal or ancient in our phylogenetic trees of all PPP Sequence Family groups (Supplemental Figure S11). Again, Pro-is conserved in the HisB position in the PrpA-PrpB group with PrpA sequences having 80% Pro. This is true for lambda phosphatase, a member of that group (Fig. 2). Notably, the most ancient enzymes, or the ‘basal variants’ are all Pro-at this position. Overall, this analysis, in combination with the MPE molecular simulation data suggest that conversion of HisB to Pro-was likely ancestral and allowed for the evolution of the PPP sequence family members and their ability to dephosphorylate new substrates.

Fig. 5.

Conservation of Potential Substrate-Binding “Clamp” Residues in PPP Family Member Groups. Candidate sequences were harvested for each PPP Family member group by HMM (Hidden Markov Model) based database searching, as detailed in Methods. Sequences were aligned as detailed in Methods. Full-length alignments were edited to comprise two alignments per PPP Family member type, one centered at Motif 2 and the other between Motif 4 and Motif 5. Residue conservation in these alignments was then visualized by construction of sequence WebLogos, as detailed in Methods. The y-axis depicts the degree of conservation in “bits” of information. Taller characters indicate higher conservation. The metal-binding His-residues in Motif 4 and Motif 5 are 100% conserved. The red triangles above the sequences designate potential substrate-binding conserved clamp residues. The percent conservation of these residues is as follows:

SLPR1: First “Clamp” Residue (R10 [99.9]); Second “Clamp” Residue (R43 [99.4]; R47 [86.4]).

SLPR2: First “Clamp” Residue (K10 [99.7]); Second “Clamp” Residue (R30 [100]; K32 [98.7]; R34 [99.3])

RLPH: First “Clamp” Residue (R10 [90.7]);

Second “Clamp” Residue [Euk]: K18 [63.9], R18 [36.1]; R22 [100]

Second “Clamp” Residue [BactSubPop1]: R18 [75.6], K18 [22.2]; K22 [75.0]

Second “Clamp” Residue [BactSubPop2]: R18 [86.2]

PrpA_B (cd07424): First “Clamp” Residue (R10 [98.5]); Second “Clamp” Residue (R19 [91.2])

ApaH (cd07422): First “Clamp” Residue (R10 [99.1]); Second “Clamp” Residue (R53 [98.9]; R55 [99.7])

PrpLike (cd07423): First “Clamp” Residue (R9 [91.3]); Second “Clamp” Residue (R41 [95.9])

PA3087 (cd07413): First “Clamp” Residue (R9 [95.2]); Second “Clamp” Residue (R55 [97.4]; R59 [99.7])

The relationship between SLP Classic, SLPR1 and SLPR2 is illustrated in the sequence alignment presented as Supplemental Figure S7. The relationship between SLP Classic and all the other PPP Family member groups is illustrated in the structure-guided alignment presented as Supplemental Figure S4. The individual alignments on which these WebLogos are based (in FASTA format) are presented as Supplemental Files S8 – S25.

Comparison of PPP sequence family members reveals alternative patterns of possible “Clamp” residues between Motif 4 and Motif 5

The data presented to this point has first established the likely functional importance in substrate binding of a “2-Arginine Clamp” in proteins characterized as protein phosphatases (PPPs). Secondly, we have shown through in silico mutagenesis with Mre11 how loss of the second conserved His-residue in Motif 5 and substitution with certain amino acid alternatives (in particular Pro) could have retained metal binding and enzymatic activity but favored a change of substrate binding. We will spend the remainder of this report examining the descendants of nuclease-like MPEs in Bacteria, the PPP Sequence Family. We will consider their sequence and structural architecture, their phylogenetic distribution and evolutionary radiation, and in particular the presence and possible significance of residues constituting various versions of a substrate binding “2-Arginine Clamp”.

We constructed the large structure-guided alignment shown as Supplemental Figure S4 (the underlying alignment is available in FASTA format as Supplemental File S2, sequence names and accessory information are provided in Supplemental Table S4). A downward arrow in Motif 2 designates a very highly conserved Arg-residue present in the solved structures and all the sequence groups, which would be predicted to constitute the first residue in a substrate binding “2-Arginine Clamp”. Between Motif 4 and Motif 5 is a more heterogeneous area with limited similarity across the various groups. A second downward arrow denotes an Arg-residue which shows apparent conservation across PrpA-PrpB (cd07424), SLP and many RLPH sequences. In addition, however, are other basic sequence columns which have been highlighted in purple. There is a basic column upstream of the second downward arrow which has a Lys-residue present in the solved structure of AtRLPH2 (5VJW) [27,36] from Arabidopsis thaliana (a eukaryotic protein phosphatase in a group derived from bacterial ancestors [37]) and either a Lys-or an Arg-throughout the various RLPH sequences below it. There is an Arg-column downstream of the 2nd arrow which corresponds to the basic residue displayed in the solved structure 4J6O (PnkP, or polynucleotide kinase phosphatase) which is a member of the PrpLike (cd07423) group, and all other members of that group plus the PA3087 (cd07413) group. In addition, there is another basic residue in the PA3087 group four residues upstream. Finally, there is a last purple highlighted column in close proximity to the second downstream arrow. This is found in ApaH (cd07422) sequences, where it is two residues away (i.e. RxR). Hence there are some PPP Sequence Family member groups which possess a single downstream conserved Arg-residue (PrpA-PrpB (cd07424), SLP, PrpLike (cd07423)), some with two apparent basic residues (ApaH (cd07422), PA3087 (cd07413)) and one group with heterogeneity within its ranks (RLPH). This raises the possibility that across all the sequence groups there might be non-equivalent downstream (between Motif 4 and Motif 5) basic residues participating in a “2-Arginine Clamp”.

Discovery of an “SLP family” within the PPP sequence family

Inspection of a large second stage sequence alignment derived from an SLP HMM search of the UniProt bacterial protein database revealed distinct sequence subpopulations, which differed from previously characterized SLPs in the region downstream of Motif 4 near the putative 2nd “Clamp” Arg-residue. We adopted the terminology of “SLPClassic” for previously studied SLP sequences, and “SLPR1” (SLP-Related1) and “SLPR2” (SLP-Related2) for the sequence types obtained. We next sought to clarify the relationships between the sequences of this putative “SLP Family” through multiple sequence alignment and Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree inference. The “SLP Family” sequences were compared to an outgroup composed of sequences of the cd00841 group, and RLPH sequences obtained through HMM searching of the UniProt Bacterial sequence database. The resulting tree is presented as Supplemental Figure S5 and the underlying alignment as Supplemental Figure S6 (sequences in aligned FASTA format in Supplemental File S3). The most critical branches have been labeled A through E. Support is strong for all of them except branch D where support is low.

The strong support for branches A and B indicates the distinctiveness of the Outgroup (cd00841) and RLPH sequences, respectively. The strong support for branch C plus its relatively long length indicate that the SLP sequences form a distinct group from the preceding RLPH and Outgroup clusters. This confirms that SLPR1 and SLPR2 are indeed specifically related to the traditional SLPs (SLPClassic) rather than representing another PPP sequence type detected by the SLP HMM as “cross-hits”.

The very short length for branch D indicates that there is relatively little difference between the SLPR1 group and the SLPR2 group, as compared to their differences with the preceding RLPH group. Placement of SLPR2 in the Maximum Likelihood tree as shown is supported by inspection of the sequence alignment. SLPClassic and SLPR1 sequences contain the typical GDxxDRG at Motif 2, whereas SLPR2 sequences have GDxxDKG. Close inspection of this alignment also reveals that in addition to the common Arg-residue between Motif 4 and Motif 5 which aligns in all three sequence groups, there are indications of additional basic residues in this area in SLPR1 and SLPR2 sequences.

In order to investigate the possibility of additional basic residues downstream of Motif 4 in SLPR1 and SLPR2 sequences, an alignment was made of a much larger number of sequences of all three types and is presented in Supplemental Figure S7 (aligned FASTA version in Supplemental File S4). The location of a basic sequence position is indicated by a triangle symbol. SLPClassic sequences (those from Eukaryotes and Bacteria) contain a single aligned Arg-residue in a WxR motif in this region. In contrast, SLPR1 sequences contain two (RFAFR typical sequence) while SLPR2 sequences contain three (RTKYR typical sequence).

The question of the inheritance pattern of the downstream (between Motif 4 and Motif 5) basic residue(s) in this sequence family is examined by reference to a cartoon version (Supplemental Figure S8) of the same Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree presented previously. Sequences in the Outgroup (cd00841) have no downstream basic residues (“N” for None in the Figure). RLPH sequences from Bacterial SubPopulation 2 have a single Arg-residue in a WxR motif (“S” for Single in the Figure). SLPClassic sequences also have a single Arg-residue in a WxR motif (“S” for Single in the Figure). In contrast SLPR1 and SLPR2 sequences have multiple basic residues (“M” for Multiple in the Figure). Hence the simplest interpretation is that the single Arg-residue pattern (indicated by a colored symbol in the Figure) is ancestral for the last common ancestor of all the SLP Family, having been inherited from the common ancestor with RLPH sequences. This pattern was then retained in the SLPClassic sequences, whereas SLPR1 and SLPR2 have diverged in the acquisition of additional basic residues. Furthermore, the possession of a single Arg-residue downstream of Motif 4 in sequences of the PrpA-PrpB group (cd07424) (of which the phage lambda phosphatase is a member) (see Supplemental Figure S4) is consistent with this being a defining feature of the common ancestor of all PPP Family sequences.

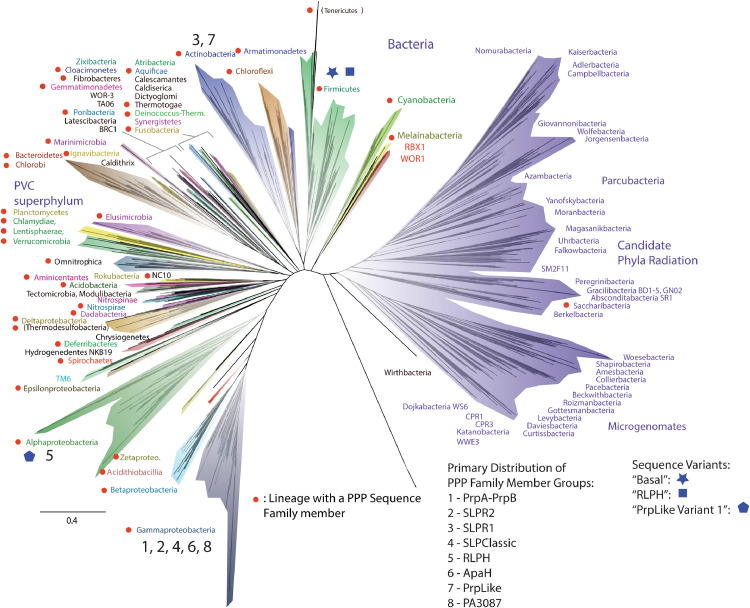

PPP sequence family members are widely distributed in bacteria and a preponderance in proteobacteria

We examined second stage HMM searches for PPP Sequence Family members in Bacteria to determine their taxonomic distribution. The family is quite widespread, with representatives in 47 phyla (overall graphic summary presented in Fig. 6). There is a preponderance in Proteobacteria, with just over 70 percent of the total and substantial representation in Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes (summary in Supplemental Table S5). Of the eight characterized groups in the PPP Sequence Family in Bacteria five of them have their primary representation in the Gammaproteobacteria (PrpA-PrpB (cd07424), SLPR2, SLPClassic, ApaH (cd07422), PA3087 (cd07413)), one in the Alphaproteobacteria (RLPH), and two in Actinobacteria (SLPR1, PrpLike (cd07423)) (Fig. 6). Of these eight groups the most widespread is RLPH (28 phyla) and the least is SLPR2 (3 phyla). Detailed graphical summary data for the various individual PPP Sequence Family member groups is presented in Supplemental Figure S9. The underlying distribution data is available in Supplemental Tables S6–S15.

Fig. 6.

PPP Sequence Family Members – Graphical Summary Taxonomic Distribution. This Figure depicts in a graphical format the distribution of PPP Sequence Family member sequences in Bacteria. A red dot denotes a taxonomic group which contains a PPP Sequence Family member. These are generally phylum-level groups with a few exceptions, such as the Proteobacteria, which are broken down into classes. The PPP Sequence Family member groups described in this report are numbered (1–8) and their primary distribution (i.e. taxonomic group with the highest number of sequences for each) is indicated. Colored symbols denote the taxonomic distribution of sequence variants, which are described in the text. Summary information for the phylum-level representation of the various PPP Sequence Family member groups is presented in Supplemental Table S5. Detailed pie-chart and bar-graph summary information on taxonomic distribution of the various sequence groups is presented in Supplemental Figure S9. The present Figure is adapted from Fig. 1 in the published report of Hug et al. 2016. That material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. International License.

WebLogo analysis of PPP sequence family member groups reveals conserved putative “2-Arginine clamp” residues in Motif 2 and between Motif 4 and Motif 5

We constructed large alignments (i.e. hundreds or thousands) of sequences within various PPP Sequence Family member groups in order to study the pattern of conservation of putative candidate residues which might participate in a “2-Arginine Clamp”. These were then edited to comprise either the region centered on Motif 2 or that between Motif 4 and Motif 5. WebLogos were then constructed as detailed in Methods. A graphic summary figure containing this dataset is presented as Fig. 5. The underlying sequence alignments are available as aligned FASTA format in Supplemental Files S5-S22. It is readily apparent that in all the PPP Sequence Family member groups there is a well-conserved basic residue at Motif 2: generally GDxxDRG (all groups except ApaH where there is GDxx(N/A)RG and SLPR2 where there is GDxxDKG). In all cases the level of conservation of the basic residue is at least 90%, and generally much higher (see Legend, Fig. 5). The conservation here is lowest in the RLPH sequences (90.7%). This is due to the presence of sequence variants which lack the conserved Arg-residue in Motif 2. These variants have been analyzed in a different section of this report. The situation is more complex downstream, between Motif 4 and Motif 5. As first suggested by the structural alignment presented as Supplemental Figure S4, some PPP Sequence Family member groups have a single basic residue in this region (PrpA-PrpB, SLPClassic, RLPH Bacterial Subpopulation 2, and PrpLike) whereas the others have more than one (SLPR1, SLPR2, Eukaryotic RLPH, RLPH Bacterial Subpopulation 1, ApaH and PA3087). Once again, the level of conservation of these downstream basic residues is generally quite high, usually above 90 percent (see Legend, Fig. 5). The exception is in the RLPH sequences, where there are subpopulations which have differing numbers of downstream (between Motif 4 and Motif 5) basic residues and where conservation levels for the basic residue alternatives are lower.

Sequence variants suggest clues about evolution of the “2-Arginine clamp”

To gain possible insight into the origin and evolution of the “2-Arginine Clamp” we scrutinized our set of sequence alignments produced by the various second-stage PPP Sequence Family group HMM searches for apparent sequence variants. The ApaH (cd07422) alignment revealed a set of sequences with alterations in the composition of both Motif 2 and downstream (i.e. between Motif 4 and Motif 5) clamp residues. Preliminary alignment and phylogenetic tree analysis revealed a small set of five sequences with NRG (rather than the typical DRG) at Motif 2 and a lack of the typical Arg-residue downstream. We made an alignment of these sequences, generated a new HMM and searched the UniProt bacterial sequence database. This produced a set of 30 sequences, restricted to the order Bacillales of the Firmicutes, which possess NRG in Motif 2 and no R downstream. An alignment of these sequences with representatives of the various PPP Sequence Family member groups plus an Outgroup composed of sequences from the cd00841 (YfcE family) is presented in Supplemental Figure S10 (the sequences are presented in aligned FASTA format in Supplemental File S26). A Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree corresponding to this alignment is presented in Supplemental Figure S11. This set of variants is most basal in the tree, with strong branch support (These are the ‘basal variants’ referred to when examining the HisB residue previously). The PPP Sequence Family member group sequences in the tree have a topology that is broadly compatible with the trees presented earlier (cf Supplemental Figures S5 and S8): PA3087 (cd07413), PrpLike (cd07423) and ApaH (cd07422) are located distally in the tree (i.e. farthest from the root); whereas PrpA-PrpB (cd07424), SLP and RLPH are more basal (i.e. closer to the tree root). The only weakly supported branch is that which leads to the clustering of PrpA-PrpB (cd07424) together with the RLPH plus SLPgroup (support given in brackets in the Figure). Manual inspection of 200 bootstrap trees revealed the reason for this – the PrpA-PrpB group shows mobility in the tree, alternating in position between that of the consensus tree (shown in the Figure) and other tree positions (most often in a separate branch closer to the root than the RLPH plus SLP group). The topology of this tree is consistent with the possibility that the variant sequences are descendants of an ancestral sequence population intermediary between the last common ancestor of the cd00841 group and the bacterial PPP Sequence Family and the subsequent radiation of that family.

The RLPH alignment revealed variant sequences which have an Asp-residue at Motif 2 but not the typical RG, but with the typical WxR motif downstream between Motif 4 and Motif 5. Alignment of these sequences with the cd00841 Outgroup and sequences from “RLPH Bacterial Subpopulation 2” (which has WxR downstream), RLPHs from Eukaryotes and “Bacterial Subpopulation 1” (which have a downstream R which aligns with that of other PPP Sequence Family member group sequences but also another basic residue upstream) produces the basis of the phylogenetic tree presented as Supplemental Figure S12. The variant sequences form three clusters basal to the RLPH subsets, with the first (Branch A) and the third (Branch B) being strongly supported. In order to investigate whether these three variant clusters are distinct from each other, more phylogenetic depth was added to the alignment by the addition of PrpA- PrpB sequences (cd07424). This expanded alignment is presented as Supplemental Figure S13 (aligned FASTA sequences are in Supplemental File S27), and the corresponding Maximum Likelihood tree as Supplemental Figure S14. In this tree the variant sequences form a unified group, with strong branch support. The position of the variant sequences in this tree is consistent with them being descendants of sequences which gave rise to the RLPH sequence populations.

The PrpLike (cd07423) alignment yielded two sets of variant sequences, which were aligned with typical PrpLike sequences and Outgroup (cd00841) sequences to produce the data presented as Supplemental Figure S15 (aligned FASTA sequences are in Supplemental File S28). The corresponding Maximum Likelihood tree is presented as Supplemental Figure S16. “Typical PrpLike” sequences possess DRG at Motif 2 and P(I/V)R downstream. “Variant 1” sequences have D(Y/H)G in Motif 2 and PER downstream. These sequences lie basal to the other PrpLike sequences, consistent with being descendants of ancestral sequences. In contrast, “Variant 2” sequences possess DKG at Motif 2 and no PxR motif downstream. These sequences lie in a derivative position, suggesting that they are secondary offshoots of ancestors of the “Typical PrpLike” sequence group. Taken together the results with these several variant sequence groups suggest that the “upstream” (i.e. Motif 2) and “downstream” (i.e. between Motif 4 and Motif 5) components of the “2-Arginine Clamp” may have evolved in a different order in different PPP Sequence Family member groups.

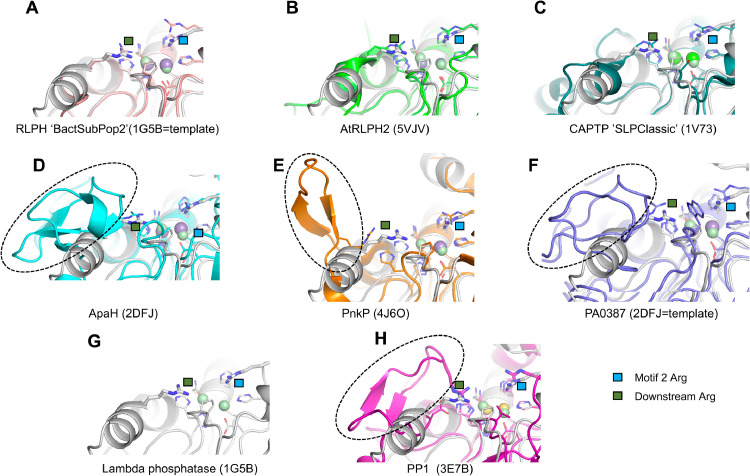

Solved structures clarify the identity of putative downstream “Clamp” residues

In our structure-guided alignment of all of the various bacterial PPP Sequence Family members (Supplemental Figure S4) there are two groups in which there are closely spaced Arg-residues which might conceivably be involved in the “2-Arginine Clamp” - ApaH (cd07422) and PA3087 (cd07413). In addition, in the RLPH group there are subpopulations of sequences with different possible downstream candidate residues for participation in the clamp. We sought to critically examine the plausibility of our alignments and the architecture of putative clamp residues by examination of solved structures, where available, and construction of homology models where no appropriate solved structure exists. In our alignments, ApaH sequences contain the characteristic motif RMR, and the second Arg-is predicted to participate in the clamp. Examination of the solved structure of the ApaH from Shigella flexneri (2DFJ) confirms that R184 (RMR) points across the active site at R41, the Motif 2 clamp residue (see Fig. 7). In contrast, R182 is pointed away from the active site pocket. For the PA3087 (cd07413) group, our alignments predict the involvement of a downstream Arg-residue in the clamp rather than another Arg-four positions upstream. Since no solved structure is available, we constructed a homology model based on the template structure 2DFJ (ApaH) as detailed in Methods for the UniProt sequence AAG06475.1 which is one of our PA3087 set. This has a downstream sequence YTRAFFRT where our alignments predict the second rather than the first Arg-as a member of the clamp (i.e. RAFFR). An examination of a refined homology model in Fig. 7 shows that it is indeed this second Arg (R217) which is pointed appropriately across the active site at the Arg-of Motif 2 (R54). In contrast, the preceding Arg-residue (R213) is in an entirely inappropriate position to interact with the substrate phosphoryl oxygen in the active site pocket. RLPH “Bacterial Subpopulation 2” sequences contain a WIR motif downstream. Since there is no solved structure for this group, we constructed a homology model of the RLPH sequence A0A529C6H2_9RHIZ using as template 1G5B (lambda phosphatase). As shown in Fig. 7, the appropriate downstream residue (R192) is pointing across the active site at the Arg-of Motif 2 (R62) as is predicted by our alignments.

Fig. 7.

Structures of PPP Sequence family members identify accessory loops and second clamp arginine residues. Structures are presented to confirm the identity of the downstream arginine between Motif 4 and Motif 5 of the “2-Arginine Clamp” where multiple arginines could play this role. The identity of this arginine is confirmed for (D) ApaH (2DFJ), (E) PnkP (4J6O) and (F) PA3087 and is shown with the green square (the first arginine of the clamp is shown with a blue square). Superimposing each structure on lambda phosphatase (shown alone in (G)) revealed sequence inserts between Motif 4 and Motif 5 (D-F, H; dashed ovals) that are absent in (A) RLPH ‘BactSubPop2, (B) AtRLPH2, (C) CAPTP ’SLPClassic, and (G) the lambda phosphatase. Each was superimposed onto the structure of the lambda phosphatase by minimizing the least-squares differences in the coordinates for the conserved residues coordinating to the divalent metal ions. The structure of the RLPH-family phosphatase (RLPH BactSubPop2; UniprotKB accession number A0A529C6H2) was generated using the coordinates of the lambda phosphatase (1G5B) as a template for homology modeling using Modeller (v.9.24). The structure of the phosphatase from P. aeruginosa, PA3087 (UniprotKB accession number Q9HZC1) was generated using the coordinates of the diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase from Shigella flexneri 2a (2DFJ) as a template for homology modeling using Modeller (v. 9.24). Metal ions are shown as coloured spheres. PDB ID codes are shown brackets.

Sequence loops downstream of Motif 4 occur in multiple PPP sequence family members

Inspection of an alignment of solved PPP Sequence Family structures generated by the DALI server (data not shown) indicates that the phage lambda phosphatase (1G5B) has a relatively simple sequence and structure, which appears to be elaborated in other Family members. Eukaryotic PPPs appear to have a supplemental sequence loop in the neighborhood of the 2nd Arg-of the clamp, as shown in the structure-guided alignment containing bacterial and eukaryotic PPPs (Supplemental Figure S1) and our structural models of protein-substrate complexes (Fig. 2). We investigated the generality of this phenomenon by examination of the structures of other PPP Sequence Family members, and by use of a homology model (see Methods) where no solved structure is available. Our results are summarized in Fig. 7, where structures are oriented in a similar fashion to that of our previous Fig. 2. Each of the structures has a pair of Arg-residues (one contributed by Motif 2 [typically GDxxDRG] and one downstream between Motif 4 and Motif 5), which are oriented in a fashion pointed toward the active site pocket which is consistent with their possible importance in substrate recognition and binding. For ApaH, PnkP, PA3087 and PP1, in the vicinity of the downstream Arg-residue there is also a sequence elaboration forming a loop not seen in the lambda phosphatase. Hence the presence of such a loop seems to be typical of many members of the PPP Sequence Family and we postulate that these loops evolved to recruit specific substrates and exclude others.

Discussion

A key mutational change fundamentally alters substrate binding and the enzymatic reaction in the transition of ancestral MPEs to the PPP sequence family

PPP Sequence Family members belong to the broader MPE superfamily, utilize a common alpha-beta sandwich fold featuring a bimetallic catalytic center to mediate a variety of enzymatic reactions [14]. Metals are coordinated by sets of conserved His, Asp-and Asn, arranged in a characteristic multi-motif pattern [36,37]. In the ancestral MPE nuclease-like protein, the linear polynucleotide substrate is bound through a combination of the actions of a conserved His-residue in Motif 3 (interacting with the penultimate “upstream residue” of the chain) and the conserved HisB of Motif 5 (interacting with the terminal “downstream” residue). The phosphodiesterase reaction leads to cleavage of the phosphate group bridging these two substrate regions (Panel A, Fig. 1). Using the structure of the Mre11 protein modelled with substrate dAdA (Fig. 3) we showed that mutational substitution of the HisB at Motif 5 with certain alternatives (A, P) could lead to retention of active site metal binding and probable retention of enzymatic capability, but with a requirement for an alteration in substrate geometry (Supplemental Table S3, Fig. 4). Pro-in particular is predicted to have profound effects on the Km of Mre11 (Table 1). This alteration could have pre-adapted a mutated protein to manifest the derived properties observed in the PPP Sequence Family where the enzymatic activities are predominantly monophosphoesterase reactions. Keppetipola [40] noted that diesterase Mre11 lacks an Arg-equivalent to Pnkp Arg237 (Clamp Arg 1) and when the Pnkp Arg237 is changed to an Ala, the phosphomonoesterase activity plummets. They further speculate that the phosphomonoesterase reaction requires neutralization by the arginine side chain due the additional negative charge on the phosphomonoester.

With the loss of HisB at Motif 5 there can be no downstream substrate binding as seen with the terminal nucleotide of a polynucleotide substrate. However, with a terminal phosphate group such binding is now unnecessary. The resulting enzymatic reaction is very similar, except that now the terminal phosphate alone is cleaved (Panel B, Fig. 1). In addition, however, a new mode of substrate binding arose in the PPP Sequence Family, the “2-Arginine Clamp”. The significance of this innovation is shown in the enzyme-substrate interactions observed in solved structures generated by our laboratory and others [[28], [29], [30],40], in the substrate-peptide interactions for the phage lambda phosphatase and eukaryotic PP1 modeled in this report (Fig. 2), and through the in vitro mutagenesis data generated by our laboratory and others showing alteration in enzymatic parameters with clamp residue substitutions (Supplemental Table S1).

Sequence variants reveal the radiation pattern of PPP sequence family members

Our finding that five PPP Sequence Family groups have their greatest concentration in the Gammaproteobacteria is consistent with the description of the prototype sequence for four of them in Escherichia coli (PrpA-PrpB, ApaH), Shewanella species (SLPClassic) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA3087) (the fifth is a new group presented in this study [SLPR2]). Similarly, the primary representation of RLPH sequences in Alphaproteobacteria is consistent with the description of the prototype representatives. However, the question arises as to whether the present location of the preponderance of a PPP Sequence Family member group sequence type corresponds to their point of origin within Bacteria or to a point of secondary radiation. Valuable clues in this regard are presented by analysis of the taxonomic distribution of the several variant sequence groups also utilized to dissect the evolution of the “2-Arginine Clamp”. The “Basal Variant” sequences which lie closest to the root of a phylogenetic tree encompassing all the PPP Sequence Family member groups (Supplemental Figure S11) are restricted to the Firmicutes (Fig. 6). This is also true of the variant sequences which lie basal to RLPHs in their common phylogenetic tree (Fig. 6, Supplemental Figure S14). In contrast, the PrpLike Variant 1 population of sequences, which lie basal to typical PrpLike sequences in their common phylogenetic tree (Supplemental Figure S16) are restricted to the Alphaproteobacteria (Fig. 6). Thus, in these several cases there is evidence suggesting that precursor sequence types to later PPP Sequence Family member groups arose first in a bacterial phylum distinct from that which contains their present predominant representation. This suggests a pattern of gene and sequence flow from one bacterial phylum to another. The exception to this pattern appears to be the SLP Sequence Family. The most basal group there (SLPR2) and the most derived (SLPClassic) (Supplemental Figure S5) are found primarily distributed within the same bacterial group (Gammaproteobacteria) (Fig. 6), indicating evolution “in place” within this phylum.

Fig. 6 is adapted from a recent publication [41] and was originally derived as a phylogenetic tree from concatenated ribosomal protein sequences. Though in that study the statistical support for the placement of the basal branches of the various phyla in Bacteria is not strong, there is other evidence suggesting that the relative branching order shown here between bacterial phyla is accurate. Two other phylogenetic trees have recently been published [42,43] which show a substantially similar relative branching order, and which were derived by two additional independent inference methods. Therefore, it appears that there is a genuinely considerable evolutionary distance between the Firmicutes and the Gammaproteobacteria, for example. One possible interpretation of this distance would reflect a difference in time – that is, that the Gammaproteobacteria arose at a later time than the Firmicutes. This cannot be affirmed unequivocally at present due to difficulties in rooting phylogenetic sequence trees from Bacteria [44]. However, it is consistent with the patterns we observe for the diversification of PPP Sequence Family members. Whether the Gammaproteobacteria are a late-diverging group or not, the concentration of PPP Sequence Family members within them is striking (41% of all Family sequences in Bacteria, Supplemental Table S5). This suggests that these sequences may be particularly important to the physiology of these organisms. This may well relate to another interesting aspect of the overall distribution of sequences shown in Fig. 6. The large radiation of organisms on the right of the Figure (in purple) represents the “Candidate Phyla Radiation”. This has a large grouping of recently proposed (hence “Candidate”) phyla, based on metagenomic and single cell genomics data from presently unculturable organisms. These constitute a large-scale organismal radiation distinct from conventional Bacteria with predicted genome characteristics (often reduced size and limited metabolic pathways, but with concentrations of distinctive gene families) consistent with an often symbiotic lifestyle [41,43]. PPP Sequence Family members are nearly totally absent in this radiation, in marked contrast to their widespread representation amongst more traditionally characterized Bacteria (i.e. the left side of the tree in Fig. 6). Taken together, these data suggest that PPP Sequence Family members may be important in complex metabolic, environmental response and independent lifestyle pathways.

PPP sequence family members generally have highly conserved basic residues positioned to function within a “2-Arginine clamp”

Our WebLogo analysis and the underlying large-scale alignments of PPP Sequence Family members of various groups revealed that there is a widespread pattern of basic residues: a single very highly conserved upstream residue (at Motif 2 [generally DGxxDRG]) and one or more downstream residues (between Motif 4 and Motif 5). This strongly suggests that the possibility of formation of a “2-Arginine Clamp” that aids the catalytic mechanism is a widespread characteristic of PPP Sequence Family member groups.

PPP sequence family variants suggest bidirectional and repeated evolution of the “2-Arginine clamp”

The observation of a widespread pattern of conserved basic residues consistent with participation in a “2-Arginine Clamp” within various PPP Sequence Family members raises the question of how such a joint feature might have evolved. A very simple evolutionary model of PPP Sequence Family diversification might posit that the last common ancestor with the nuclease-like MPE activity might have generated a prototypical version of the clamp which would then be elaborated in turn by each of the subsequent family members for specialized substrate binding. However, our data with sequence variants suggests the possibility of a more complex picture. We found a population of variants which have GDxxNRG at Motif 2 and no downstream Arg-residue. These variants were basal in our phylogenetic tree to all PPP Sequence Family groups, suggesting descent from ancestral sequences which would have existed prior to group diversification (it is notable that these basal variants all contain Pro-at the ‘HisB position’, as do the majority of sequences recognized as basal within each group (for instance, see RLPH variant) allowing for evolution of the clamp and docking of new substrates). This suggests that the clamp might have been initially constructed from the “upstream end” first to the “downstream end” later. In addition, we found variants which are basal to the RLPH sequence assemblage, suggesting that they have descended from ancestors which would have existed prior to radiation of this particular group. These variants have D but no RG at Motif 2, but the typical WxR motif downstream. This suggests that the ancestor immediately prior to RLPH diversification had a clamp which was constructed from the “downstream end” first, then the “upstream end”. Finally, we identified two sets of variant sequences related to the PrpLike (cd07423) sequence group. The first variant group, located basal in our trees to the typical PrpLike sequences, has D(Y/H)G in Motif 2 and PER downstream. This again suggests construction of the clamp in the immediate precursors of the PrpLike group as occurring “downstream end” first, then “upstream end” second. The second variant group is clearly a derived group, with DKG in Motif 2 and no PxR downstream. Hence it would appear that this sequence group has lost both components of the typical clamp, with the upstream end replacing Arg-with Lys. Taken together, these data suggest that rather than a simple model as introduced above, there may have been multiple instances of “re-invention” of the clamp to arrive at the typical forms found in the various PPP Sequence Family member groups. This suggests a remarkable degree of convergence toward equivalent sequence and structural solutions.

The existing data on the effect of mutations at one or the other of the two clamp residues in PPPs (summarized in Supplemental Table S1) indicate that alteration of a single residue may produce profound (e.g. PP1) or more moderate (e.g. AtRLPH2, WipA) effects. This makes it plausible that sequences with only one functioning clamp residue might, in at least some cases, have enzymatic activity. This might render them capable of interaction with certain substrates to the exclusion of others and be sufficient to foster further adaptation to their new substrates and subsequent acquisition of the second clamp residue thereafter.

At this point it might be objected that it is not certain that the variant sequences faithfully reproduce the characteristics of their distant ancestors. Suppose they are of ancient origin but have instead been more recently modified to lose typical clamp characteristics? Even if this were so, and a simpler PPP Sequence Family diversification model were therefore plausible, it is nevertheless remarkable that such variant sequences have survived to the present, given their lack of the clamp which appears to be universal and likely important in characterized PPPs. Surely it would be expected that such sequences would not have been retained in Bacteria if they were functionally inactive. A recent review of the metallophosphoesterase (MPE) superfamily [14] emphasized the “structural fidelity and functional promiscuity” of the group (i.e. a common fold mediating a great diversity of specific enzymatic activities). These variants might indicate that much the same could be said for the PPP Sequence Family fold – that in addition to the several different known biochemistries there could be others, represented by these variants, which await functional characterization.

Generality of downstream sequence loops in PPP sequence family members

Our structure-guided sequence alignments, protein-substrate structural models, and examination of solved or modeled structures have demonstrated the presence of a supplementary sequence loop in representatives of most PPP Sequence Family groups. The phage lambda phosphatase (1G5B) has the simplest structure. This is consistent with the topology of our largest most detailed phylogenetic tree (Supplemental Figure S11) derived from a sequence alignment between members of the various PPP Sequence Family groups. The PrpA-PrpB group lies in the most basal position, consistent with it being the most deeply diverging PPP Sequence Family type. The phage lambda phosphatase is very closely related to E. coli PrpA, both being members of the PrpA-PrpB (cd07424) group. It displays “generalist” enzymatic activity, cleaving the phosphomonester bonds of p-Ser/p-Thr-and p-Tyr-containing protein substrates, and also the phosphodiester bonds of 2′,3′ cyclic nucleotides [45]. Proteins derived from other PPP Sequence Family member groups have extended sequence loops in the neighborhood of the downstream 2nd clamp Arg-residue (i.e. between Motif 4 and Motif 5) (Fig. 7), which are associated with a diversity of enzymatic activities. An example is provided by the structure 4J6O for the polynucleotide kinase phosphatase domain of Clostridium thermocellum (see Fig. 7). This domain is one part of a multidomain protein which performs RNA end-healing and end-sealing, with the phosphatase reaction cleaving 2′,3′ cyclic phosphate RNA ends. Here the second clamp residue lies in a sequence region (YGLPV R) which forms part of an extended loop, visible on the protein surface. In this structure bound citrate extends this loop, and the authors suggest that in the presence of the natural RNA substrate the loop makes contact and closes. Hence it appears that during the diversification of PPP Sequence Family members sequence loop elaboration was a common strategy employed to increase the sequence space available for accommodation of diverse substrates as part of various enzymatic mechanisms.

It is intriguing that such sequence loops containing the downstream 2nd clamp Arg-residue also appear to be present in well-studied eukaryotic PPPs (such as PP1, PP2A and PP5), as indicated by our structure-guided sequence alignment (Supplemental Figure S1) and protein-substrate structural models (Fig. 2, Panel C). These considerations suggest that the loops and Arg-residues they contain are functionally significant. A recent structural analysis of human PP5 with a bound phosphomimetic substrate confirmed the importance to substrate binding of Arg400, a downstream Arg-residue corresponding to PP1 Arg221. Furthermore, analysis of a large set of eukaryotic structures strongly suggested that this role is universal in other PPPs [29]. Our results agree with this analysis. Several MPEs also have additional sequence regions (sometimes called caps) that aid in substrate specificity. This is exemplified by Mre11 where the cap sequence controls recruitment of its partner Rad50 which establishes if Mre11 acts as an exo- or endo-nuclease [14,46]. Additional data supporting a conserved and functionally significant role for residues in this loop is the observation that the binding of the PPP inhibitor okadaic acid (OA) to PP1 occurs at Asp220 and Arg221 in this loop [47]. The architectural similarity between loops and putative substrate-binding Arg-residues adopted in bacterial PPP Sequence Family members and eukaryotic PPPs begs the question of the relationship between the two. We will examine the evolution of eukaryotic PPP members in a future report (Kerk et al., in preparation).

Summary

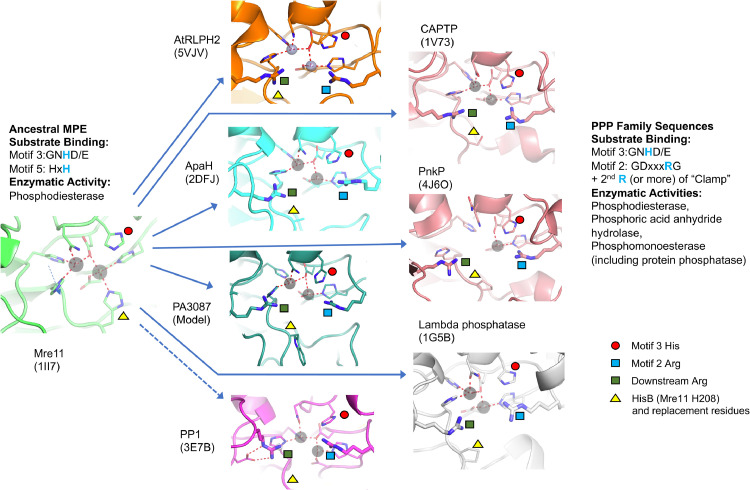

A summary appreciation of our findings in this report can be gained by examination of the combination of Fig. 1 and Fig. 8. A nuclease-like phosphodiesterase ancestor (here represented by the solved structure of the DNA-repair protein Mre11 (left side of Fig. 8)) interacted with its polynucleotide substrate utilizing the His-of Motif 3 and one of the two His-residues (HisB) in Motif 5 (Fig. 8 and also Panel A in Fig. 1). Mutational loss of the HisB residue and substitution with certain amino acid alternatives (likely Pro) would have allowed continued enzymatic activity but required a change in substrate geometry to dock the active site. This key mutational change would have opened up the evolutionary trajectory leading to the phosphomonoesterases of the PPP Sequence Family (Panel B, Fig. 1; Panel B, Fig. 8). Two Arg-residues (one in a remodeled Motif 2 [typically GDxxDRG] and one between Motif 4 and Motif 5) were added as a “Clamp” to assist the unchanged His-in Motif 3 in substrate binding. The downstream Arg-residue often resides in the context of a supplementary sequence loop (seen in all PPP Sequence Family members except those of the PrpA-PrpB group having the simplest phosphatase domain architecture) (Panel B, Fig. 8). This elaboration apparently adds critical sequence space important for specialized accommodation to a more diverse substrate set and enzymatic activities.

Fig. 8.

Substrate binding residues in an ancestral nuclease MPE and derived PPP sequence family members. The figure shows the solved structure of an ancestral nuclease MPE (Mre11 [1II7]) and solved structures or homology model for derived PPP sequence family members, all in equivalent orientation. The ancestral substrate binding pattern in Mre11 features use of the His-residue of Motif 3 and HisB in Motif 5. In the derivative PPP sequence family members HisB has been substituted with other residues (the most frequent being proline) which has apparently allowed enzyme adaptation to bind alternative substrates [see also Fig. 4]. This adaptation has encompassed a diversification of enzymatic activities from the ancestral phosphodiesterase to the addition of phosphoric acid anhydride hydrolase and phosphomonoesterase (including protein phosphatase) activities. Substrate binding in the derived PPP sequence family structures retains the ancestral Motif 3 His-residue but replaces the lost Motif 5 HisB with a “2-Arginine Clamp” featuring a conserved Arg-in Motif 2 and a downstream Arg-between Motif 4 and Motif 5. The dashed arrow between Mre11 and PP1 reflects the occurrence of a distinct evolutionary pathway for the derivation of the closely related set of eukaryotic PPPs (PP1, PP2A/4/6, PP2B, PP5, PP7), which will be the subject of a future communication from our group. Dashed red lines indicate ion-coordination bonds, and key catalytic and metal ion-coordinating residues are drawn in stick representation. Metal ions are shown as semi-transparent gray spheres. PDB ID codes are shown brackets.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic procedures

Database search and retrieval of initial candidate MPE and PPP sequence family member sequences

Sequences were collected from a broad set of subgroups (39 in all) across the metallophosphatase superfamily (cd00838) of the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) [48] (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd). The “most diverse” sequences (generally ten) from each subgroup were collected. In addition, a set of 30 representative sequences from solved structures in the CATH [49] (http://www.cathdb.info/) protein structure database were collected from family 3.60.21.10. These two sets were then merged to form a non-redundant set containing approximately 350 sequences. This set was used to begin exploration of sequence interrelationships between bacterial PPP Sequence Family members and the rest of the MPE superfamily.

Multiple sequence alignment

The MAFFT server [50] (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) was used to generate candidate multiple sequence alignments. For moderate sized alignments (up to several hundred sequences) the BLOSUM45 (BL45) scoring matrix, and the LINSI or EINSI alignment option were used. Some alignments were made by addition of new sequences to existing alignments using MAFFT-Add (addition of full-length sequences; BL45; l-INSI). Some alignments were made by aligning component sequence groups then combining them together using MAFFT-Merge (BL45, E-INSI). For very large alignments (many hundreds or thousands of sequences) the MAFFT-Auto feature was used (FFT-NS-2). Sequence alignments were visualized and edited in GeneDoc (http://www.softpedia.com/get/Science-CAD/GeneDoc.shtml). Duplicate (i.e. 100% identical) sequences were removed using the “ElimDups” feature at https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/elimdupesv2/elimdupes.html. Alignments were evaluated for intact presence of previously characterized sequence motifs [14,26,37]). Alignments sometimes required regional re-alignment around sequence Motif 5. This was done using a regional re-alignment capability of MAFFT (Ruby script kindly supplied by Dr. Kazutaka Katoh, modified for Windows by Justin Kerk) (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/regionalrealignment.html) using the following parameters (realign –localpair –maxiterate 100 –bl 45 –op 3.0; treeoption –6merpair).

Structural alignments and structure-guided multiple sequence alignments

The structure of AtRLPH2 (PDB ID: 5VJW) [27] or the phage lambda phosphatase (1G5B) was used to search the DALI database [51] (http://ekhidna2.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali/oldstyle.html) to obtain structural alignments with bacterial and eukaryotic members of the PPP Sequence Family (CAPTP [cold active protein tyrosine phosphatase, PDB ID: 1V73]), the WipA effector of Legionella (PDB ID: 5N6X), ApaH (2DFJ), PnkP (4J6O), PP1 (3E7B), PP2A (3FGA), PP5 (1S95). These structural alignments were sometimes used as a constraint for sequence alignment at the MAFFT server (BL45, E-INSI).

Phylogenetic tree inference