Abstract

The current literature has mainly focused on the biology of tendons and on the characterization of the biological properties of tenocytes and tenoblasts. It is still not understood how these cells can work together in homeostatic equilibrium. We put forward the concept of the “tendon unit” as a morpho-functional unit that can be influenced by a variety of external stimuli such as mechanical stimuli, hormonal influence, or pathological states. We describe how this unit can modify itself to respond to such stimuli. We evidence the capability of the tendon unit of healing itself through the production of collagen following different mechanical stimuli and hypothesize that restoration of the homeostatic balance of the tendon unit should be a therapeutic target.

Keywords: Tendon unit, Tenocyte, Tenoblast, Tendon healing

Introduction

Most of the recent work on the biology of tendons has concentrated on the characterisation of the mechanical, biochemical and biological properties of tenocytes and tenoblasts. It still remains unclear how these cells interact among themselves and are in homeostatic balance with the extracellular matrix (ECM) in which they are embedded in. Focusing on the interactions that occur during mechanical stimuli, under the influence of hormones or growth factors and in pathological states, this brief article aim to explain how this can take place [1]. Tendons connect muscle to bone and allow transmission of forces generated by muscle to bone, resulting in joint movement. Tendon injuries produce considerable morbidity, and the disability that they cause may last for several months de- spite what is considered appropriate management [2].

Regretfully, the pathophysiology of tendon tissue is still poorly understood, and the interactions between the various cell types present in tendons, and between them and the ECM have still not been thoroughly explored. Tendons are multicellular tissue, interposed between bone and muscles, allowing joint movement and stabilisation [3, 4]. Extensive mechanical loads imposed on tendons can lead to acute and chronic injuries [5]. Tendinopathies represent major medical problems associated with overuse, dysmetabolic disorders, inflammation, genetic and familial predisposition, and age-related alteration [1, 6–10]. All these multifactorial agents can contribute to the failed healing response typical of tendinopathic lesions [11, 12].

Aim

We put forward the concept of a ‘Tendon Unit’ as a metabolic and functional unit of the various cellular components of tendons to at least partially explain how changes in different physiological and pathological conditions may arise from metabolic or (bio)mechanical disarray of such Tendon Unit [13, 14].

Microanatomical features of the tendon unit

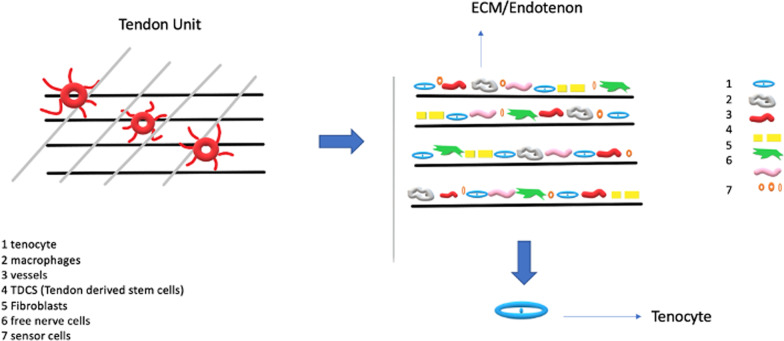

Tendons are a multi-unit hierarchical structure composed of collagen molecules, fibrils, and fascicles that run parallel to its long axis [15]. Tenoblasts and tenocytes, constitute about 90% of the cellular elements of a tendon [16–18] (Table 1). The other 10% is composed of chondrocytes close to the insertion of the tendon to bone, synovial cells of the tendon surface, vascular cells, such as endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells of the arterioles [3, 19], nerve cells, tendon derived stem cells (TDCS), immune cells [20–22]. Tendons are also surrounded by cell-produced proteins and polysaccharides: collagen (mostly type I collagen) [19, 23, 24], elastin (1–5%) embedded in a proteoglycan (1–5%) and water matrix (70–80%) [24]. The ECM acts as a scaffold, defining the tissue shape and structure, and as a substrate for cell adhesion, growth, and differentiation [25]. Signal transmission of the tendon unit is mediated by the cytoskeleton, integrins, g proteins and stretching-activated ion channel [26]. The cytoskeleton is composed of microfilaments and microtubules and plays a central role in mechanotransduction [27, 28]. Integrins are transmembrane protein heterodimers composed of two subunits. Integrins have three domains: an extracellular matrix domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain [29], playing a role in the signalling interface between the extracellular matrix and the cell [29]. With the integrins, the G proteins are another family of membrane proteins involved in mechanotransduction and are activated by mechanical forces [29]. In addition to the activation of signal proteins, mechanical forces also trigger stretch-activated ion channels [30]. Mechanical stretching induced Ca++ signal transmission appears to involve actin filaments, as actin polymerization inhibitors abolished Ca++ responses [13] (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of tenocytes and tenoblasts

| TENOCYTE | TENOBLAST |

|---|---|

| In the middle of the primary fiber bundle | In the periphery of the primary fiber bundle |

| Spindle or stellate shape | Round shape cells |

| Elongated nuclei | Large ovoid nuclei |

| Condensed cromatin, low concentration of pinocynotic vescicles | High concentration of pinocynotic vescicles |

| Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum well developed | Golgi and rough endoplasmic reticulum well developed |

| Many free ribosomes | Few lysosomes |

| Few mitochondria | Few mitochondria |

| Predominant in normal tendon | Predominant in young tendon |

Fig. 1.

The tendon unit

Mechanical load and mechanical transduction of the tendon unit

Tendons are exposed to different types of loads during normal function [31], and are subjected mainly to cyclical tensile loads, often working as elastic tissue to decrease the metabolic costs of high-level muscle contraction, exhibiting different behaviours in response to different forces [31, 32]. The tendon unit can adapt to mechanical loading modifying its structure and composition. In particular, the ECM transmits mechanical loads, and stores and dissipates loading-induced elastic energy mediating various cellular functions including DNA and protein syntheses [33]. The adaptative mechanisms whereby tendon units detect mechanical stimuli and modify themselves have only been investigated in vitro [34].

To understand this response, it is important to better define how tendons detect, respond and transduce mechanical stimuli [34]. The changes perceived after mechanical loading are transmitted by gap junctions, which allow between-cell communications: these permit rapid exchange of ions and signalling molecules between cells, inducing stimulatory and inhibitory responses to tensile loads [26], effecting change in the various cellular components of tendons. For example, compressive loading in vitro downregulates SCX, alfa 1 and alfa 2 integrin [35]. These proteins are also significantly downregulated in vivo when tendons are loaded. Short duration compressive loads lead to an increase in the production of type II collagen, aggrecan and lumican [35], while tensile loads lead to an increase of collagen I and III [36]. Hence, modulating both compressive and tensile loads on tendons may prevent a deleterious tendon response modifying collagen production. This should be probably a therapeutic target, but further studies are needed to clarify it [37]. Loading can also influence the production of ECM protein, causing the release of growth factors, such as TGF-b1, bFGF, and PDGF [38]. TGF- b mediates collagen production induced by mechanical loading [39], and also modulates ECM turnover by regulating the expression and activity of MMPs [21, 40–42]. Finally, TGF- b also interacts with growth factors/cytokines to regulate ECM homeostasis in various tissues [43]. Hence, the tendon unit responds to mechanical forces by altering gene expression, protein synthesis, and cell phenotype. These early adaptive responses may influence and lead to long-term tendon structure modifications and thus produce measurable changes in the mechanical properties of tendons [44]. These modified cellular components include the extracellular matrix, cytoskeleton, integrins, G proteins, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and stretching-activated ion channels [25].

Hormones and hormonal disorders

Hormones and hormonal disorders may influence the behavior of the tendon unit [10, 45–47].

A central role is played by oestrogens, thyroid hormones, and relaxin. All the pathological states can influence the tendon healing process and the collagen production.

Sexual hormones

Oestrogens play an important role in the homeostasis of the tendon unit in pre-menopausal women, who exhibit a lower risk of tendinopathies [48, 49]. Oestrogen levels can influence tendon metabolism, morphology and biomechanical properties [50–52]. Postmenopausal oestrogen deficiency is linked to the down-regulation of the turnover of collagen fibres and a decrease in the elasticity in tendon [53]. Low oestrogen levels are associated with impaired tendon healing with lower cell proliferation, altered metabolism, MMP overexpression, and ECM protein loss [22, 48, 51, 54]. In in vitro models, a decrease in oestrogen levels downregulated collagen turnover and reduced elasticity of tendons [50], and may account for the less favourable outcome experienced by women following surgery for Achilles tendinopathy [55].

Thyroid hormones

Thyroid hormones (THs) can influence the tendon unit [45, 56]. TH-receptor isoforms are expressed in tendons [46, 47, 57]. Moreover, triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) contrast apoptosis in healthy tenocytes [46, 58]. THs (especially T3) stimulate cellular proliferation and type I collagen formation, the major fibrillar collagen in tendons [46, 58], with an additive effect of ascorbic acid (AA) on T3, increasing collagen expression, ECM protein secretion, and the expression of COMP (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein) and tendon cells proliferation [46, 58]. In addition, AA can stimulate the proliferation of tendon cells [58].

Relaxin

The role of relaxin and how it may influence the tendon unit is not completely clear. Relaxin is a member of a family of peptide hormones structurally similar to insulin, but which diverged from insulin to form a distinct peptide family based on a two-chain structures [59]. Relaxin is antifibrotic and can downregulate fibroblast activity, increase collagenase synthesis, and inhibit collagen I, which is stimulated by transforming growth factor-β (TGFB) [60]. However, the effect of relaxin on tendon and ligament healing remains unclear, although it appears that relaxin inhibits tendon healing [59].

Glucose metabolism

Diabetes mellitus may be a predisposing factor for tendinopathy [13]. The chronic nature of diabetes demonstrates the long-term effects of elevated glucose levels on tendon cells [13]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) negatively impacts tendon homeostasis in the absence of acute injury [61, 62]. In general, diabetic patients experience an augmented incidence of tendon rupture and tendinopathy [63], with structural abnormalities including calcification [64]. T2DM is a multifactorial pathology, and it is difficult to assess the relative contributions of each factor to diabetic tendinopathy. Elevated serum haemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) levels are strongly associated with the development of the tendinopathy [65, 66]. In terms of the efficacy of tendinopathy treatments, T2DM modifies the response to treatment, with decreased effectiveness [67].

Growth factors

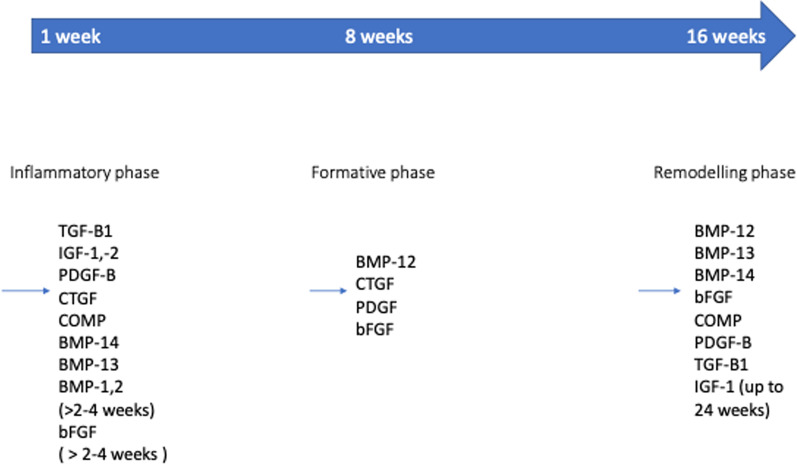

Numerous growth factors are involved in the repair processes of the tendon unit [68]. These include BMPs, EGF, FGF1, FGF2, IGF-1, IGF-2, PDGF-AA, PDGF-BB, PDGF-AB, TGF-β, which can influence the tendon unit acting separately or in concert with one another. The expression of the various growth factors is different in each phase of the tendon unit healing process (Fig. 2) [69–72]. The repair process is influenced by inflammation [6, 73].

Fig. 2.

The process of tendon healing goes through three phases. GF is expressed in each phase, promoting the proliferation of cells, ECM and the tendon healing process

Basic fibroblastic growth factor

bFGF is a single-chain polypeptide of 146 amino acids and is a member of the heparin-binding GF family. bFGF is angiogenic [74], and has mitogenic effects on many mesenchymal cells such as ligament fibroblasts [75]. bFGF is involved in wound healing and exhibits a stimulatory effect on human rotator cuff tendon cells in vitro, though it suppresses collagen synthesis [76].

Bone morphogenetic proteins

BMPs (bone morphogenetic proteins) are a group of factors of the TGF-β superfamily that can stimulate formation of bone and stimulate cell mitogenesis and healing in the tendon unit [77], though their mechanism remains unclear [78, 79].

Insulin-like growth factor

IGF-1 is found in different cell types, including cartilage, bone, muscle and tendon cells [80]. During the process of tendon healing, IGF-1 seems to stimulate the proliferation and migration of the tenoblasts during the inflammatory phase [81]. In addition to its mitogenic effect, IGF-1 can also stimulate selected components of matrix synthesis and its expression, as seen in vitro in tenocytes [82]. Moreover, in a rat model of Achilles tendon injury, IGF-1 induced tenocyte migration, division, matrix expression and accelerated functional recovery [83, 84].

Transforming growth factor-β

Originally known as a tumour transformation factor, it is now clear that TGF-β has a wide range of physiological effects on the tendon unit [85, 86]. The expression of TGF-β seems closely associated with the expression of a differentiated phenotype in some different cell lines, including mesenchymal precursor cells [87]. The formation of tendons and ligaments is directly influenced by the TGF-β superfamily [88]. TGF-β can stimulate tendon cell migration and mitogenesis, but it cannot stimulate robust expression of extracellular matrix [87, 89]. TGF-β, moreover, may control the switching point in the healing process from normal to pathological [90]. All three TGF-β isoforms significantly increase collagen I and III production in cultured tendon fibroblasts [91] with TGF-β1 inducing scar tissue formation, whereas TGF-β3 reduces it [92].

Vascular endothelial growth factors

Vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) are two families of proteins resulting from alternate splicing of mRNA from a single, 8 exon, VEGF gene [93]. Probably the most important member is VEGF-A, composed of two subunits. Other members are placenta growth factor, VEGF-B, VEGF-C and VEGF-D [93]. All members of the VEGF family stimulate cellular responses by binding to tyrosine kinase receptors (the VEGFRs) on the cell surface, causing their activation through transphosphorylation [93]. In a canine model of tendon injury, researchers identified a repair site expressing a message for VEGF, suggesting a potential for organizing the angiogenic response during the early postoperative phase of tendon healing [94, 95].

Neuropeptides and the tendon unit

The role of substance P (SP) on tendon healing has recently become apparent [96]. Most studies performed on SP and tendons focus on healing after the transection of a tendon [97, 98], but SP may play a role in tendinopathy. In addition to its established role in peripheral pain, SP has pro-inflammatory effects and effects on vasodilation and vascular permeabilization, and also reparative effects including angiogenesis and cell proliferation of the tendon unit [98] (Table 2).

Table 2.

The main modification of tendon unit according to physiological and pathological states

| EXTERNAL STIMULI | CHANGES IN THE TENDON UNIT |

|---|---|

| Mechanical force | ECM modifier/ TGF B → augmented collagen production |

| Tyrode hormones | T3: stimulate cellular proliferation, and type I collagen formation, ECM protein secretion, in pathological patterns inhibit tendon healing |

| Oestrogens | Low: altered ECM metabolism, overexposes MMP and reduce collagen production and tendon healing |

| Relaxin | Antifibrotic, downregulate fibroblast activity, increase collagenase synthesis, and inhibit collagen I, inhibits tendon healing |

| Diabetes | Lowers collagen production, inhibits tendon healing |

| Neuropeptides (P substance) | Accelerates tendon healing, and induces greats angiogenesis |

Future perspectives

Tissue engineering has emerged as a promising approach for tendon healing, with the potential to regenerate functional tendon tissue and improve patient outcomes. Potential future perspectives in tissue engineering for tendon healing include:

Advances in biomaterials: Biomaterials play a critical role in tissue engineering by providing structural support and promoting tissue regeneration. New biomaterials are being developed with enhanced mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and bioactivity, which could improve tendon healing outcomes [99].

Cellular therapies: Stem cells and other cell-based therapies have shown promise in promoting tendon healing. Researchers are exploring new cell sources and developing new delivery methods to enhance the effectiveness of cellular therapies [100, 101].

Bioprinting: 3D bioprinting enables the precise placement of cells and biomaterials to produce complex tissue structures, making it a promising technology for tendon tissue engineering, with new bioprinting techniques and materials to optimize tendon regeneration [102].

Gene therapy: Gene therapy has the potential to enhance the healing process by promoting the expression of growth factors and other factors involved in tendon regeneration. Researchers are developing new gene delivery systems to safely and effectively deliver therapeutic genes to damaged tendon tissue [103].

Conclusions

The tendon unit ensures biosynthesis and the maintenance of the tendon structure. Starting from a mechanical or biochemical stimulus, a series of changes occur in the ECM and the cellular part of the tendon unit. These affect the production of collagen, proteins etc., influencing the tendon healing with a feedback mechanism. Further studies are needed to clarify the molecular mechanism involved in the process of tendon healing and homeostasis. We have concentrated on tenocytes, but tendons are 'organs' with a complex anatomical structure and even more complex physiology. Tissue engineering just using one cell type will have some success, but it is possible that the future will be co-culture of the various cellular components of tendons, coupled with appropriate biochemical and mechanical stimuli, keeping in mind that the tendon unit also contains vascular and neural components.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- TDCS

Tendon derived stem cells

- RTKs

Receptor tyrosine kinases

- MAPKs

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- TH

Thyroid hormone

- T3

Triiodothyronine

- T4

Thyroxine

- AA

Ascorbic acid

- COMP

Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein

- TGFB

Transforming growth factor-β

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- HbA1c

Serum haemoglobin A1C

- BMPs

Bone morphogenetic proteins

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factors

- the VEGFRs

Tyrosine kinase receptors

- SP

Substance P

Author contributions

FC conceptualization, writing, revision; FM: revision; FO: revision; NM: conceptualization, supervision, revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no external funding.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nicola Maffulli, Email: n.maffulli@qmul.ac.uk.

Francesco Cuozzo, Email: fra.cuoz@gmail.com.

Filippo Migliorini, Email: migliorini.md@gmail.com.

Francesco Oliva, Email: olivafrancesco@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. Tendons and ligaments—an overview. Histol Histopathol. 1997;12:1135–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almekinders LC, Almekinders SV. Outcome in the treatment of chronic overuse sports injuries: a retrospective study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;19:157–161. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.19.3.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannus P. Structure of the tendon connective tissue. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:312–320. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2000.010006312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowson D, Knight MM, Screen HR. Zonal variation in primary cilia elongation correlates with localized biomechanical degradation in stress deprived tendon. J Orthop Res. 2016;34:2146–2153. doi: 10.1002/jor.23229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan KM, Maffulli N. Tendinopathy: an Achilles' heel for athletes and clinicians. Clin J Sport Med. 1998;8:151–154. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chisari E, Rehak L, Khan WS, Maffulli N. Tendon healing is adversely affected by low-grade inflammation. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16:700. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02811-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Addona A, Somma D, Formisano S, Rosa D, Di Donato SL, Maffulli N. Heat shock induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human Achilles tendon tenocytes. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2016;30:115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Buono A, Battery L, Denaro V, Maccauro G, Maffulli N. Tendinopathy and inflammation: some truths. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:45–50. doi: 10.1177/03946320110241S209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battery L, Maffulli N. Inflammation in overuse tendon injuries. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19:213–217. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e31820e6a92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elli S, Schiaffini G, Macchi M, Spezia M, Chisari E, Maffulli N. High-fat diet, adipokines and low-grade inflammation are associated with disrupted tendon healing: a systematic review of preclinical studies. Br Med Bull. 2021;138:126–143. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldab007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rees JD, Maffulli N, Cook J. Management of tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1855–1867. doi: 10.1177/0363546508324283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chisari E, Rehak L, Khan WS, Maffulli N. The role of the immune system in tendon healing: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2020;133:49–64. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley G. The pathogenesis of tendinopathy. A molecular perspective. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:131–142. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuen FS, Chuk CY, Ping WY, Nar WW, Kim HL, Ming CK. Immunohistochemical characterization of cells in adult human patellar tendons. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:1151–1157. doi: 10.1369/jhc.3A6232.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang JH. Mechanobiology of tendon. J Biomech. 2006;39:1563–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doral MN, Alam M, Bozkurt M, Turhan E, Atay OA, Donmez G, Maffulli N. Functional anatomy of the Achilles tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:638–643. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migliorini F, Tingart M, Maffulli N. Progress with stem cell therapies for tendon tissue regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20:1373–1379. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2020.1786532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maffulli N, Wong J, Almekinders LC. Types and epidemiology of tendinopathy. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22:675–692. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(03)00004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jozsa L, Kannus P. Histopathological findings in spontaneous tendon ruptures. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1997;7:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1997.tb00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seifert O, Baerwald C. Interaction of pain and chronic inflammation. Z Rheumatol. 2021;80:205–213. doi: 10.1007/s00393-020-00951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Buono A, Oliva F, Osti L, Maffulli N. Metalloproteases and tendinopathy. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3:51–57. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Del Buono A, Oliva F, Longo UG, Rodeo SA, Orchard J, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Metalloproteases and rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freiberger H, Grove D, Sivarajah A, Pinnell SR. Procollagen I synthesis in human skin fibroblasts: effect on culture conditions on biosynthesis. J Investig Dermatol. 1980;75:425–430. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12524080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karousou E, Ronga M, Vigetti D, Barcolli D, Passi A, Maffulli N. Molecular interactions in extracellular matrix of tendon. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2010;2:1–12. doi: 10.2741/e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silver FH, Freeman JW, Seehra GP. Collagen self-assembly and the development of tendon mechanical properties. J Biomech. 2003;36:1529–1553. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magra M, Hughes S, El Haj AJ, Maffulli N. VOCCs and TREK-1 ion channel expression in human tenocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1053–1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00053.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longo UG, Berton A, Khan WS, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Histopathology of rotator cuff tears. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19:227–236. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318213bccb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingber DE. Mechanical signaling and the cellular response to extracellular matrix in angiogenesis and cardiovascular physiology. Circ Res. 2002;91:877–887. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000039537.73816.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sackin H. Mechanosensitive channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:333–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Docking S, Samiric T, Scase E, Purdam C, Cook J. Relationship between compressive loading and ECM changes in tendons. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3:7–11. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleischhacker V, Klatte-Schulz F, Minkwitz S, Schmock A, Rummler M, Seliger A, Willie BM, Wildemann B. In vivo and in vitro mechanical loading of mouse Achilles tendons and tenocytes-a pilot study. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijms21041313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nichols AEC, Settlage RE, Werre SR, Dahlgren LA. Novel roles for scleraxis in regulating adult tenocyte function. BMC Cell Biol. 2018;19:14. doi: 10.1186/s12860-018-0166-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh JL, Jou IM, Wu CL, Wu PT, Shiau AL, Chong HE, Lo YT, Shen PC, Chen SY. Estrogen and mechanical loading-related regulation of estrogen receptor-beta and apoptosis in tendinopathy. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gumucio JP, Schonk MM, Kharaz YA, Comerford E, Mendias CL. Scleraxis is required for the growth of adult tendons in response to mechanical loading. JCI Insight. 2020 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliva F, Gatti S, Porcellini G, Forsyth NR, Maffulli N. Growth factors and tendon healing. Med Sport Sci. 2012;57:53–64. doi: 10.1159/000328878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frizziero A, Fini M, Salamanna F, Veicsteinas A, Maffulli N, Marini M. Effect of training and sudden detraining on the patellar tendon and its enthesis in rats. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skutek M, van Griensven M, Zeichen J, Brauer N, Bosch U. Cyclic mechanical stretching modulates secretion pattern of growth factors in human tendon fibroblasts. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;86:48–52. doi: 10.1007/s004210100502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mullender M, El Haj AJ, Yang Y, van Duin MA, Burger EH, Klein-Nulend J. Mechanotransduction of bone cellsin vitro: Mechanobiology of bone tissue. Med Biol Eng Compu. 2004;42:14–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02351006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Von Offenberg Sweeney N, Cummins PM, Cotter EJ, Fitzpatrick PA, Birney YA, Redmond EM, Cahill PA. Cyclic strain-mediated regulation of vascular endothelial cell migration and tube formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castagna A, Cesari E, Garofalo R, Gigante A, Conti M, Markopoulos N, Maffulli N. Matrix metalloproteases and their inhibitors are altered in torn rotator cuff tendons, but also in the macroscopically and histologically intact portion of those tendons. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3:132–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciardulli MC, Marino L, Lovecchio J, Giordano E, Forsyth NR, Selleri C, Maffulli N, Porta GD. Tendon and cytokine marker expression by human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a hyaluronate/poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA)/fibrin three-dimensional (3D) scaffold. Cells. 2020 doi: 10.3390/cells9051268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heinemeier K, Langberg H, Olesen JL, Kjaer M. Role of TGF-beta1 in relation to exercise-induced type I collagen synthesis in human tendinous tissue. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2003(95):2390–2397. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00403.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narici MV, Maffulli N, Maganaris CN. Ageing of human muscles and tendons. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1548–1554. doi: 10.1080/09638280701831058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliva F, Piccirilli E, Berardi AC, Frizziero A, Tarantino U, Maffulli N. Hormones and tendinopathies: the current evidence. Br Med Bull. 2016;117:39–58. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldv054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliva F, Piccirilli E, Berardi AC, Tarantino U, Maffulli N. Influence of thyroid hormones on tendon homeostasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;920:133–138. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-33943-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oliva F, Berardi AC, Misiti S, Maffulli N. Thyroid hormones and tendon: current views and future perspectives. Concise review. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3:201–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torricelli P, Veronesi F, Pagani S, Maffulli N, Masiero S, Frizziero A, Fini M. In vitro tenocyte metabolism in aging and oestrogen deficiency. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:2125–2136. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9500-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai WC, Chang HN, Yu TY, Chien CH, Fu LF, Liang FC, Pang JH. Decreased proliferation of aging tenocytes is associated with down-regulation of cellular senescence-inhibited gene and up-regulation of p27. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1598–1603. doi: 10.1002/jor.21418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Irie T, Takahata M, Majima T, Abe Y, Komatsu M, Iwasaki N, Minami A. Effect of selective estrogen receptor modulator/raloxifene analogue on proliferation and collagen metabolism of tendon fibroblast. Connect Tissue Res. 2010;51:179–187. doi: 10.3109/03008200903204669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nogara PRB, Godoy-Santos AL, Fonseca FCP, Cesar-Netto C, Carvalho KC, Baracat EC, Maffulli N, Pontin PA, Santos MCL. Association of estrogen receptor beta polymorphisms with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Mol Cell Biochem. 2020;471:63–69. doi: 10.1007/s11010-020-03765-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pontin PA, Nogara PRB, Fonseca FCP, Cesar Netto C, Carvalho KC, Soares Junior JM, Baracat EC, Fernandes TD, Maffulli N, Santos MCL, et al. ERalpha PvuII and XbaI polymorphisms in postmenopausal women with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: a case control study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13:316. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-1020-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Circi E, Akpinar S, Balcik C, Bacanli D, Guven G, Akgun RC, Tuncay IC. Biomechanical and histological comparison of the influence of oestrogen deficient state on tendon healing potential in rats. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1461–1466. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0778-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma P, Maffulli N. Basic biology of tendon injury and healing. Surgeon. 2005;3:309–316. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(05)80109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maffulli N, Testa V, Capasso G, Oliva F, Panni AS, Longo UG, King JB. Surgery for chronic Achilles tendinopathy produces worse results in women. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1714–1720. doi: 10.1080/09638280701786765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berardi AC, Oliva F, Berardocco M, la Rovere M, Accorsi P, Maffulli N. Thyroid hormones increase collagen I and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) expression in vitro human tenocytes. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4:285–291. doi: 10.32098/mltj.03.2014.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oliva F, Berardi AC, Misiti S, Verga Falzacappa C, Iacone A, Maffulli N. Thyroid hormones enhance growth and counteract apoptosis in human tenocytes isolated from rotator cuff tendons. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e705. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oliva F, Maffulli N, Gissi C, Veronesi F, Calciano L, Fini M, Brogini S, Gallorini M, Antonetti Lamorgese Passeri C, Bernardini R, et al. Combined ascorbic acid and T3 produce better healing compared to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in an Achilles tendon injury rat model: a proof of concept study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:54. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1098-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu T, Bai J, Xu M, Yu B, Lin J, Guo X, Liu Y, Zhang D, Yan K, Hu D, et al. Relaxin inhibits patellar tendon healing in rats: a histological and biochemical evaluation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:349. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2729-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sasser JM. The emerging role of relaxin as a novel therapeutic pathway in the treatment of chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R559–565. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00528.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ames PR, Longo UG, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Achilles tendon problems: not just an orthopaedic issue. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1646–1650. doi: 10.1080/09638280701785882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ceravolo ML, Gaida JE, Keegan RJ. Quality-of-life in Achilles tendinopathy: an exploratory study. Clin J Sport Med. 2020;30:495–502. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenbloom AL. Limitation of finger joint mobility in diabetes mellitus. J Diabet Complicat. 1989;3:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0891-6632(89)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mavrikakis ME, Drimis S, Kontoyannis DA, Rasidakis A, Moulopoulou ES, Kontoyannis S. Calcific shoulder periarthritis (tendinitis) in adult onset diabetes mellitus: a controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:211–214. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vance MC, Tucker JJ, Harness NG. The association of hemoglobin A1c with the prevalence of stenosing flexor tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1765–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stevens J, Couper D, Pankow J, Folsom AR, Duncan BB, Nieto FJ, Jones D, Tyroler HA. Sensitivity and specificity of anthropometrics for the prediction of diabetes in a biracial cohort. Obes Res. 2001;9:696–705. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin YC, Li YJ, Rui YF, Dai GC, Shi L, Xu HL, Ni M, Zhao S, Chen H, Wang C, et al. The effects of high glucose on tendon-derived stem cells: implications of the pathogenesis of diabetic tendon disorders. Oncotarget. 2017;8:17518–17528. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oliva F, Via AG, Maffulli N. Role of growth factors in rotator cuff healing. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19:218–226. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3182250c78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharma P, Maffulli N. Tendinopathy and tendon injury: the future. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1733–1745. doi: 10.1080/09638280701788274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sharma P, Maffulli N. Biology of tendon injury: healing, modeling and remodeling. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6:181–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharma P, Maffulli N. The future: rehabilitation, gene therapy, optimization of healing. Foot Ankle Clin. 2005;10:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharma P, Maffulli N. Tendon injury and tendinopathy: healing and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:187–202. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.D'Addona A, Maffulli N, Formisano S, Rosa D. Inflammation in tendinopathy. Surgeon. 2017;15:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Majima T, Marchuk LL, Sciore P, Shrive NG, Frank CB, Hart DA. Compressive compared with tensile loading of medial collateral ligament scar in vitro uniquely influences mRNA levels for aggrecan, collagen type II, and collagenase. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:524–531. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gabra N, Khayat A, Calabresi P, Khiat A. Detection of elevated basic fibroblast growth factor during early hours of in vitro angiogenesis using a fast ELISA immunoassay. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:1423–1430. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takahashi S, Nakajima M, Kobayashi M, Wakabayashi I, Miyakoshi N, Minagawa H, Itoi E. Effect of recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on fibroblast-like cells from human rotator cuff tendon. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2002;198:207–214. doi: 10.1620/tjem.198.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dale TP, Mazher S, Webb WR, Zhou J, Maffulli N, Chen GQ, El Haj AJ, Forsyth NR. Tenogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2018;24:361–368. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2017.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu Y, Bliss JP, Bruce WJ, Walsh WR. Bone morphogenetic proteins and Smad expression in ovine tendon-bone healing. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eliasson P, Fahlgren A, Aspenberg P. Mechanical load and BMP signaling during tendon repair: a role for follistatin? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1592–1597. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0253-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trippel SB, Wroblewski J, Makower AM, Whelan MC, Schoenfeld D, Doctrow SR. Regulation of growth-plate chondrocytes by insulin-like growth-factor I and basic fibroblast growth factor. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:177–189. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Molloy T, Wang Y, Murrell G. The roles of growth factors in tendon and ligament healing. Sports Med. 2003;33:381–394. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsuzaki M, Brigman BE, Yamamoto J, Lawrence WT, Simmons JG, Mohapatra NK, Lund PK, Van Wyk J, Hannafin JA, Bhargava MM, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I is expressed by avian flexor tendon cells. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:546–556. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Banes AJ, Tsuzaki M, Hu P, Brigman B, Brown T, Almekinders L, Lawrence WT, Fischer T. PDGF-BB, IGF-I and mechanical load stimulate DNA synthesis in avian tendon fibroblasts in vitro. J Biomech. 1995;28:1505–1513. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kurtz CA, Loebig TG, Anderson DD, DeMeo PJ, Campbell PG. Insulin-like growth factor I accelerates functional recovery from Achilles tendon injury in a rat model. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:363–369. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270031701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sporn MB, Roberts AB. Transforming growth factor-beta: recent progress and new challenges. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1017–1021. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chan KM, Fu SC, Wong YP, Hui WC, Cheuk YC, Wong MW. Expression of transforming growth factor beta isoforms and their roles in tendon healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:399–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsubone T, Moran SL, Subramaniam M, Amadio PC, Spelsberg TC, An KN. Effect of TGF-beta inducible early gene deficiency on flexor tendon healing. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:569–575. doi: 10.1002/jor.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wolfman NM, Hattersley G, Cox K, Celeste AJ, Nelson R, Yamaji N, Dube JL, DiBlasio-Smith E, Nove J, Song JJ, et al. Ectopic induction of tendon and ligament in rats by growth and differentiation factors 5, 6, and 7, members of the TGF-beta gene family. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:321–330. doi: 10.1172/JCI119537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Anaguchi Y, Yasuda K, Majima T, Tohyama H, Minami A, Hayashi K. The effect of transforming growth factor-beta on mechanical properties of the fibrous tissue regenerated in the patellar tendon after resecting the central portion. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2005;20:959–965. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF. Role of transforming growth factor beta in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klein MB, Yalamanchi N, Pham H, Longaker MT, Chang J. Flexor tendon healing in vitro: effects of TGF-beta on tendon cell collagen production. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:615–620. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.34004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Campbell BH, Agarwal C, Wang JH. TGF-beta1, TGF-beta3, and PGE(2) regulate contraction of human patellar tendon fibroblasts. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2004;2:239–245. doi: 10.1007/s10237-004-0041-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ferrara N, Gerber HP. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in angiogenesis. Acta Haematol. 2001;106:148–156. doi: 10.1159/000046610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bidder M, Towler DA, Gelberman RH, Boyer MI. Expression of mRNA for vascular endothelial growth factor at the repair site of healing canine flexor tendon. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:247–252. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tol JL, Spiezia F, Maffulli N. Neovascularization in Achilles tendinopathy: have we been chasing a red herring? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:1891–1894. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Andersson G, Backman LJ, Scott A, Lorentzon R, Forsgren S, Danielson P. Substance P accelerates hypercellularity and angiogenesis in tendon tissue and enhances paratendinitis in response to Achilles tendon overuse in a tendinopathy model. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:1017–1022. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.082750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bring DK, Reno C, Renstrom P, Salo P, Hart DA, Ackermann PW. Joint immobilization reduces the expression of sensory neuropeptide receptors and impairs healing after tendon rupture in a rat model. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:274–280. doi: 10.1002/jor.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carlsson O, Schizas N, Li J, Ackermann PW. Substance P injections enhance tissue proliferation and regulate sensory nerve ingrowth in rat tendon repair. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21:562–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Freedman BR, Kuttler A, Beckmann N, Nam S, Kent D, Schuleit M, Ramazani F, Accart N, Rock A, Li J, et al. Enhanced tendon healing by a tough hydrogel with an adhesive side and high drug-loading capacity. Nat Biomed Eng. 2022;6:1167–1179. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00810-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leong NL, Kator JL, Clemens TL, James A, Enamoto-Iwamoto M, Jiang J. Tendon and ligament healing and current approaches to tendon and ligament regeneration. J Orthop Res. 2020;38:7–12. doi: 10.1002/jor.24475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen W, Sun Y, Gu X, Cai J, Liu X, Zhang X, Chen J, Hao Y, Chen S. Conditioned medium of human bone marrow-derived stem cells promotes tendon-bone healing of the rotator cuff in a rat model. Biomaterials. 2021;271:120714. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Makuku R, Werthel JD, Zanjani LO, Nabian MH, Tantuoyir MM. New frontiers of tendon augmentation technology in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: a concise literature review. J Int Med Res. 2022;50:3000605221117212. doi: 10.1177/03000605221117212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tang JB, Zhou YL, Wu YF, Liu PY, Wang XT. Gene therapy strategies to improve strength and quality of flexor tendon healing. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16:291–301. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2016.1134479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.