Abstract

Face identification is particularly prone to error when individuals identify people of a race other than their own – a phenomenon known as the other-race effect (ORE). Here, we show that collaborative “wisdom-of-crowds” decision-making substantially improves face identification accuracy for own- and other-race faces over individuals working alone. In two online experiments, East Asian and White individuals recognized own- and other-race faces as individuals and as part of a collaborative dyad. Collaboration never proved more beneficial in a social setting than when individual identification decisions were combined computationally. The reliable benefit of non-social collaboration may stem from its ability to avoid the potential negative outcomes of group diversity such as conflict. Consistent with this benefit, the racial diversity of collaborators did not influence either general or race-specific face identification accuracy. Our findings suggest that collaboration between two individuals is a promising strategy for improving cross-race face identification that may translate effectively into forensic and eyewitness settings.

Keywords: collaboration, face-identity matching, group diversity, other-race effect, wisdom-of-crowds

BACKGROUND

People recognize faces of their own race more accurately than faces of “other” races (Malpass & Kravitz, 1969). This “other-race-effect” (ORE) occurs in laboratory (Meissner & Brigham, 2001) and real-world settings (e.g. eyewitness identification; Innocence Project, 2020). Potential strategies for improving other-race face recognition include individuated training (DeGutis et al., 2011; Lavrakas et al., 1976; Lebrecht et al., 2009; McGugin et al., 2011; Tanaka & Pierce, 2009), increased developmental exposure (Anzures et al., 2012; Heron-Delaney et al., 2011; Sangrigoli & De Schonen, 2004), caricatured exemplars (Rodrguez et al., 2008), increased learning time (Marcon et al., 2010), and learning identities from multiple images (Cavazos, Noyes, & O'Toole, 2019). However, there are limitations to each of these strategies. For example, individuated training is time-consuming (Lebrecht et al., 2009; McGugin et al., 2011; Tanaka & Pierce, 2009) and learning identities from caricatured exemplars or multiple images is impractical in applied scenarios (e.g. eyewitness identification). Increased developmental exposure cannot be leveraged to help adults. Consequently, there remains a need to explore ways to improve other-race face recognition.

One promising strategy is to exploit collaborative “wisdom-of-crowds” decision-making (Surowiecki, 2005). In general, face identification is more accurate when decisions are made by pairs/groups of people than when they are made individually (Bruce et al., 2001). Collaboration improves face-identification accuracy in both social (Dowsett et al., 2015; Jeckeln et al., 2018) and non-social scenarios (Jeckeln et al., 2018; White et al., 2013, 2015). In social collaboration, two or more individuals work together to produce a single response. In non-social collaboration, individual item responses are averaged to obtain a group judgement without social interaction (i.e. blind fusion). Previous research shows that social and non-social collaboration yield equivalent benefits (Jeckeln et al., 2018). However, to date, collaborative decision-making for other-race face identification has not been studied.

Social and non-social collaboration operate via distinct mechanisms. In social collaboration, performance is driven by the higher-performing individual (Dowsett et al., 2015; Jeckeln et al., 2018). Because social dyads rely on the more accurate member of a pair (Jeckeln et al., 2018), low-performing individuals benefit more than high-performing individuals (Dowsett et al., 2015). Jeckeln et al. (2018) implemented computational models (Bahrami et al., 2010) to explore the potential strategies used during social collaboration. Specifically, the authors used responses from individuals when they completed the task alone to model the observed social collaboration accuracy using three models. The coin-flip model averaged individual overall accuracy scores, the behaviour-feedback model selected the individual accuracy score of the more accurate member, and the confidence-sharing model selected the individual accuracy score of the more confident member. The authors found that the behaviour-feedback model best approximated the social dyads performance. These findings suggest that dyads depend on implicit social feedback to determine the more accurate member of the dyad (cf. behaviour-feedback model, [Bahrami et al., 2010]). Non-social collaboration typically combines individual responses at the item level and considers each dyad member and each stimulus item equally (Phillips et al., 2018; White et al., 2013, 2015). This collaboration approach exploits strengths of both individuals. Blind fusion works best when individual strategies are both different and effective (O'Toole et al., 2007; Phillips et al., 2018). For example, fusing algorithms based on different computational strategies (O'Toole et al., 2007), as well as fusing algorithms and humans strategies, yields face identification performance improvements (Phillips et al., 2018).

Although the effect of diversity (including racial diversity) in group decision-making has been considered previously, to date, no study has examined the role of racial diversity in face identification accuracy. Our main goal is to examine whether racial diversity impacts face identification accuracy and collaboration benefits, and if so to what extent. We explore the question of how the racial diversity of the individuals in a dyad affects both social and non-social collaboration on a face-identification task. Exploring how same- and different-race dyads perform a task of own- and other-race face identification allows us to examine the relationship between dyad diversity and dyad face identification ability for same- and other-race face. Specifically, the well-established finding of higher ability for own- versus other-race face recognition complicates the collaborative task when the dyads are diverse. This complexity is increased, because diversity and ability often compete with one another (Hong & Page, 2004; Luan et al., 2012; Moreland et al., 2013). High-ability groups tend to be inherently less diverse, and highly-diverse groups tend to have a greater range of individual ability. From a social perspective, racial diversity in groups increases creativity and thoughtful responses (McLeod et al., 1996; Sommers, 2006), but also conflict and distrust, compared to homogeneous groups (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; Moreland et al., 2013). Combined, the literature suggests that the effect of race on collaboration may be complex. For example, we might expect that the combination of two different-race individuals with strategies of recognition tuned, each for faces of their own race, would yield greater overall compared to same-race dyads. Specifically, different-race dyads might perform more accurately than same-race dyads, because they benefit from (1) diverse individual strategies and (2) different specialized strategies for own-race faces. In addition, the combination of two individuals of the same race, may result in a dyad that has specialized skills for identifying faces of one racial group (i.e. greater ability). Thus, same-race dyads might have greater race-specific face identification accuracy compared to different-race dyads. Notably, any combination of two or more individuals increases both diversity and ability to a certain extent. Here we aim to explore whether we can tease diversity and ability apart by considering accuracy differences across dyads (same vs. different-race dyads) and by comparing overall and race-specific face identification accuracy.

In Experiment 1, we evaluated the benefits of collaboration for own- and other-race face identification. We hypothesized that collaboration would benefit performance in social and non-social situations for own- and other-race face identification. In Experiment 2, we compared racially diverse (East Asian and White) dyads versus racially homogeneous dyads (two East Asian or two White participants). If the ability is a stronger factor than diversity, performance for race-specific face stimuli should be better in homogeneous dyads. If strategy diversity is a stronger factor than ability, performance would be better in racially diverse dyads.

EXPERIMENT 1

In Experiment 1, we examined whether social and non-social collaboration improves own- and other-race face identification accuracy. In a previous study, which did not control for the race of the participant or the face stimulus, social and non-social collaboration yielded similar face identification accuracy improvements (Jeckeln et al., 2018). However, the complex effects of race on face identification suggest that collaboration might impact own- and other-race face identification differently. Although initially designed as an in-person study, the Covid-19 pandemic altered this plan. All experimental procedures were conducted online.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 116) were recruited in same-race dyads (East Asian dyads; N = 27)/(White dyads; N = 31) from The University of Texas at Dallas online research participant pool, SONA. One research exposure credit was given as compensation for participation. A power analysis using PANGEA (v0.2; Westfall, 2015) revealed that a total of 108 participants (54 dyads) was needed in order to detect a medium effect size (d = 0.5) with a power of .80. This power was selected to detect the full 2 (within-subjects: stimulus race) × 3 (within-subjects: group) × 2 (between-subjects: participant race) interaction. Eligible participants self-identified as either East Asian or White (but not both), had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and were at least 18 years old. Race eligibility was determined based on self-report via an eligibility survey using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, 2019). Race inclusion criteria were determined based on available images in the Notre Dame dataset used here (see Stimuli). Three White participants' (and their partners') data were removed because once they completed the experiment, they reported that they did not identify as White. Three participants (two White participants and one East Asian participant) and their partner's data were removed due to low performance (less than 2 SD below the mean). The final analysis included 104 participants or 52 dyads (26 East Asian dyads, and 26 White dyads).

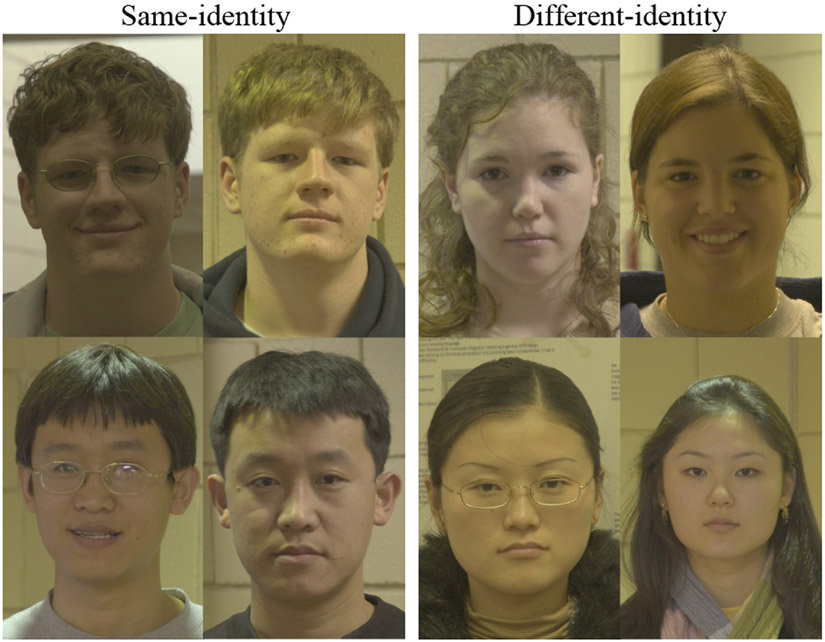

Stimuli

Face images (40 East Asian and 40 White) were selected from the Notre Dame dataset (Phillips et al., 2011, 2012; see Figure 1). This dataset was selected because it provided us with face images partitioned by difficulty level. A face recognition algorithm based on Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, A2017b (Ranjan et al., 2019), was used to screen for challenging image stimuli, and has similar identification accuracy for both East Asian and White faces (Cavazos, Phillips, et al., 2019). Challenging image pairs were selected by choosing same-identity pairs with the lowest similarity scores, and different-identity pairs with the highest similarity scores. The A2017b algorithm had comparable accuracy for East Asian (AUC = 0.403) and White faces (AUC = 0.403) on the final image pairs. Image pairs were divided into two sets: Set A (20 East Asian/20 White) and Set B (20 East Asian/20 White) and were used to counterbalance the images across conditions (individual and social-dyad). All images were cropped to reveal the face and neck area only.

FIGURE 1.

Experiments 1 and 2: stimuli of White (top panel) and East Asian (bottom panel) same-identity pairs (left panel), and different-identity pairs (right panel).

Procedure

Participants were recruited in same-race dyads (see Experiment 2 for different-race pairs). After signing up, participants received a Webex Meetings link to join the study virtually. The experimental session began once both participants joined the Webex meeting (experiment). Participants were encouraged to turn on their webcam and were required to have a working microphone/speaker. After completing the consent process, participants received verbal instructions for the experimental task. The “screen share” and the “screen control” Webex features were used to complete all experimental tasks virtually. These functions enabled participants to view the researchers' computer screen and use their own mouse and keyboard to navigate the experiment. Participants saw two faces (image pairs) on the screen side-by-side at a time, and were then asked if the image pairs represented the same person, or two different people. Responses were made using a 5-point Likert scale (+2: Sure they are the same person, +1: Think they are the same person, 0: Do not know, −1: Think they are different people, −2: Sure they are different people). Participant responses were recorded by clicking on the rating scale on the computer screen. This task was completed twice, once individually (individual) and once with a partner (social dyad). Task order was counterbalanced, such that half of the participants completed the individual task and then the social-collaboration task, and half completed the social-collaboration task first and then the individual task.

Set A and Set B were counterbalanced also, such that half the participants completed the individual task on Set A (and the partner task with Set B) and half completed the individual task with Set B (and the partner task with Set A). The task was self-paced and all responses were recorded using mouse clicks on the screen. After completing both tasks, a demographic and social dyad experience questionnaire was administered.

Individual

While one member of the pair completed the individual task, their study partner was transferred to the Webex Meeting “lobby” where the study partner could not hear or see any of the research activities, but they were not removed from the Webex call. There was no social interaction between participants at this time.

Social collaboration

During the social-collaboration condition, both participants were invited back into the Webex meeting where they were able to see the screen and virtually interact with each other. Because the Webex screen control feature could only be granted to one user at a time, “clicker” duties were randomly assigned, before the experiment began. Participants were instructed to work together to come up with a single decision for each image pair. There were no instructions on how participants should select the final answer or how rating disagreements should be resolved.

Non-social collaboration

Item-by-item responses completed in the individual condition were fused, or averaged, together for each dyad. This fusion created a composite fused score for each dyad on every item. The new fused score was used to compute performance on the non-social collaboration condition.

Social dyad experience questionnaire

To measure participants' experience completing the task with a partner and virtually, a 10-question survey was administered after the demographic survey including five questions related to the participant's experience working with their partner (e.g. ‘My partner and I worked well together’, and “I felt comfortable voicing my opinion to my partner’) rated from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. Participants were asked also to rate their contribution and their partner's contribution on the task (a 50%–50% response denoted equal contribution) and to report which facial features (eyes, nose, mouth, other, etc.) they focused on when making responses on their own, and with their partner. Given the virtual nature of this study, three additional questions were asked to gauge participants' experience completing the task virtually (e.g. ‘Taking the experiment online made it difficult to complete the task’, ‘Connectivity or internet issues made it difficult to complete the task’ and ‘Overall, my experience completing the task online was enjoyable’).

Analysis and results

The data were submitted to a 2 (stimulus race: East Asian/White) × 2 (participant race: East Asian/White) × 3 (group: Individual/Non-Social Dyad/Social Dyad) mixed-ANOVA design with stimulus race and groups as within-subjects factors and participant race as a between-subjects factor. The dependent variable (performance) was measured as the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). A post-collaboration survey was administered to gauge participants' online experience with their partner.

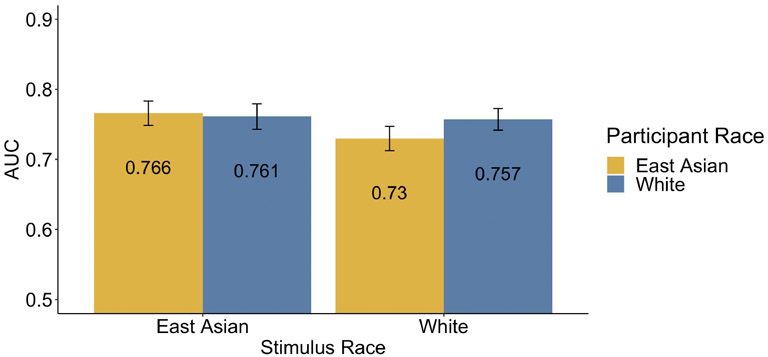

Race effects

Results showed no effect of participant race. However, there was an effect of stimulus race, F(1, 102) = 7.84, MSe = 0.008, p = .006, . Face identification accuracy was greater for East Asian faces (M = 0.76, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.75, 0.78]) than for White faces (M = 0.74, SD = 0.10, 95% CI [0.73, 0.76]). This stimulus effect was qualified by the presence of a significant interaction between stimulus and participant race, i.e. a partial other-race effect; F(1, 102) = 5.03, MSe = 0.008, p = .03, . East Asian participants had a greater accuracy for East Asian faces (M = 0.77, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.75, 0.78]) compared to White faces (M = 0.73, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.71, 0.75]). In contrast, White participants had comparable accuracy for White faces (M = 0.76, SD = 0.10, 95% CI [0.74, 0.77]) and East Asian faces (M = 0.76, SD = 0.10, 95% CI [0.74, 0.78]; see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Face-identification accuracy for own- and other-race faces. Accuracy (AUC) results for East Asian participants (yellow) and White participants (blue). East Asian participants had a greater identification accuracy for East Asian faces compared to White faces. White participants had comparable accuracy for White faces and East Asian faces. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

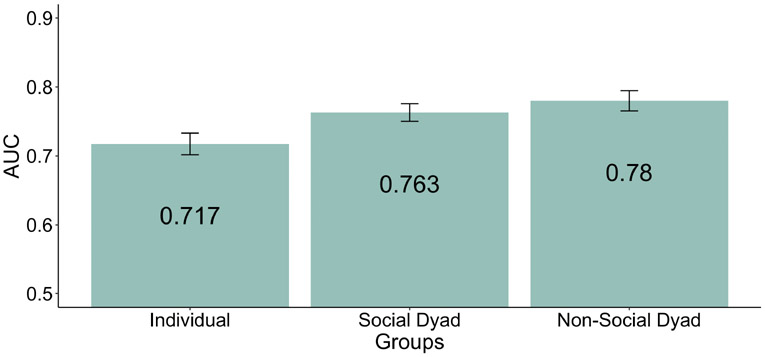

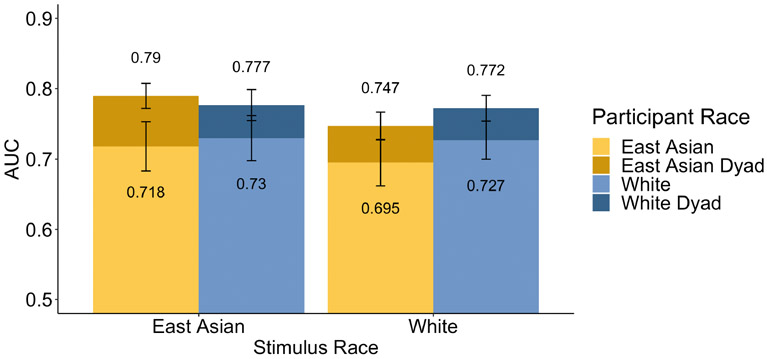

Collaboration benefits

Overall accuracy was measured across three conditions: individuals, non-social dyads and social-dyads. As expected, there was an effect of group condition, F(2, 204) = 2.71, MSe = 0.008, p < .0001, ; see Figure 3. Planned comparisons revealed that non-social dyads (M = 0.78, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.77, 0.79]) had greater accuracy than individuals (M = 0.72, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.70, 0.73]; t(204) = 7.12, p < .0001). Similarly, social-dyads (M = 0.76, SD = 0.09, 95% CI [0.75, 0.78]) had a greater accuracy than individuals, t(204) = 5.19, p < .0001. There were no differences between social and non-social dyads, t(204) = 1.92, p = .1675. No other collaboration interactions were significant, which suggests comparable collaboration benefits for own- and other-race faces (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Face-identification accuracy (AUC) for individuals, social dyads, and non-social dyads. Social and non-social dyad accuracy was greater than individual performance. There were no performance differences between social and non-social collaboration. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 4.

Collaboration benefits for own- and other-race faces collapsed across collaboration type (social and non-social collaboration). Face-identification accuracy for East Asian individuals (yellow), East Asian dyads (dark yellow), White individuals (blue) and White dyads (dark blue) on own- and other race faces. Collaboration improved accuracy for both East Asian and White individuals for both race face stimulus. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Order effects

Task order was counterbalanced so that half of the participants completed the task first on their own and then with partner, and half of participants completed the task with a partner first and then on their own. When task order was included in the model, there was an interaction between order and collaboration type, F(2, 200) = 12.13, MSe = 0.007, p < .0001, . When participants completed the task individually first, their non-social dyad performance (M = 0.76, SD = 0.09, 95% CI [0.78, 0.73]) was similar to their social dyad performance (M = 0.78, SD = 0.08, 95% CI [0.76, 0.80]; t(200) = −1.94, p = .13). However, when participants completed the task with a partner first, their non-social dyad performance (M = 0.79, SD = 0.10, 95% CI [0.82, 0.76]) was more accurate than their social-dyad performance (M = 0.74, SD = 0.08, 95% CI [0.76, 0.72]; t(200) = 4.80, p < .0001). For completeness, we also explored the relationship between task order and confidence. Confidence was measured by the dyads' use of the five-point rating scale on same- and different-identity image pairs. A post hoc chi-square test of Independence revealed a significant relationship between task order and use of the rating scale, χ2(8, N = 4160) = 29.99, p = .0002, only for same-identity pairs. Pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of .005 (.05/9), showed that participants who completed the task individually first were more likely to select, “sure they are the same” (p = .0009) compared to participants who completed the task with a partner first.

Social experience survey

The majority (87%–94%) of participants agreed with the following statements: “My partner and I worked well together” (37%: Agree; 57%: Strongly agree), “I would gladly work with my partner again on other tasks” (33%: Agree; 54%: Strongly agree), and “I felt comfortable voicing my opinion to my partner” (30%: Agree; 61%: Strongly agree). On average, participants reported that their partner and themselves contributed equally to the task (self: 50%, partner: 40%). Although participants worked well with their partner, about a third of participants strongly disagreed with the statement “I felt comfortable letting my partner know when I disagreed” (31%: Agree; 30%: Strongly disagree). For questions related specifically to completing the task online, most participants disagreed with the following statements: “Taking the experiment online made it difficult to complete the task” (36%: Disagree; 43%: Strongly disagree),“Connectivity or internet issues made it difficult to complete the task” (30%: Disagree; 53%: Strongly disagree) and agreed with “Overall, my experience completing the task online was enjoyable” (42%: Agree; 52%: Strongly Agree).

Experiment 1: Discussion

Collaboration improves identification accuracy for both own- and other race faces. Thus, it is a robust strategy for increasing face-identification accuracy, both within and across race. Social and non-social modes of collaboration proved equally beneficial, consistent with a previous study (Jeckeln et al., 2018). Social interaction between individuals is not a prerequisite for collaborative decision-making improvements, for either own- and other-race individuals. However, the benefits of social collaboration were maximized when participants completed the task on their own before completing the task with a partner. Although this finding suggests that social versus non-social collaboration may be more susceptible to experimental factors (e.g. task order), task order accuracy effects were not found for Exp. 2 (see Analysis and Results section). Task order was also related to confidence but only for the extreme end of the scale for same-identity image pairs. The majority of participants reported generally positive interactions with their same-race social dyad partner, though a third of participants were not comfortable telling their partner when they disagreed. Participants' hesitation to express disagreement may have been due to factors associated with working in dyads (e.g. personality differences and feeling intimidated by their partner).

EXPERIMENT 2

Group diversity in decision-making tasks can produce both positive and negative outcomes (Mannix & Neale, 2005; Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). Diversity promotes innovative and thoughtful solutions/responses (Moreland et al., 2013; Sommers, 2006), but can heighten distrust and conflict (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; Moreland et al., 2013). In Experiment 2, we explored how group racial diversity impacts collaboration benefits during face identification decisions. We also explored the impact of other-race experience via an individuated experience survey (see Supporting Information). Once again, all experimental procedures were conducted online.

Methods

Participants

Participant recruitment, materials and restrictions were the same as in Experiment 1, except for the demographic composition of the dyads. For Experiment 2, recruitment included both same-race (East Asian/East Asian and White/White) and different-race dyads (East Asian/White). A power analysis using PANGEA (v0.2; Westfall, 2015) indicated that a total of 162 participants (81 dyads) was needed in order to detect a medium effect size (d = 0.5) with a power of .80. This power was selected to detect the full 2 (within-subjects: stimulus race) × 3 (within-subjects: group) × 3 (between-subjects: dyad race) interaction. Eligibility requirements were the same as in Experiment 1 and again determined based on self-report via an eligibility survey using Qualtrics (2019). Two East Asian participants' (and their partners') data were removed, because they reported that they did not identify as East Asian after they completed the experiment. The final analysis was computed on 154 participants or 77 dyads (24 East Asian Dyads, 25 East Asian/White Dyads and 28 White Dyads).

Stimuli and materials

The stimuli used in Experiment 2 were identical to those used in Experiment 1.

Procedure

The procedure for Experiment 2 was identical to that used in Experiment 1 with the addition of the individual other-race experience survey (see Supporting Information). Participants completed both individual and social dyad face identifications (counterbalanced), the demographic and social dyad experience survey, and an individuation experience survey. During the Webex meeting, as one participant completed the individual face identification task, their study partner completed the individuation survey. The non-social dyad condition was created “synthetically” after data collection was completed.

Analysis and results

The data were submitted to a 2 (stimulus race: East Asian/White) × 3 (dyad race groups: East Asian/East Asian, White/White, East Asian/White) × 3 (group: individual/non-social dyad/social dyad) mixed-ANOVA design with stimulus race and groups as within-subject factors and dyad race groups a between-subject factor. Again, face-identification accuracy (dependent variable) was measured by AUC.

Race effects

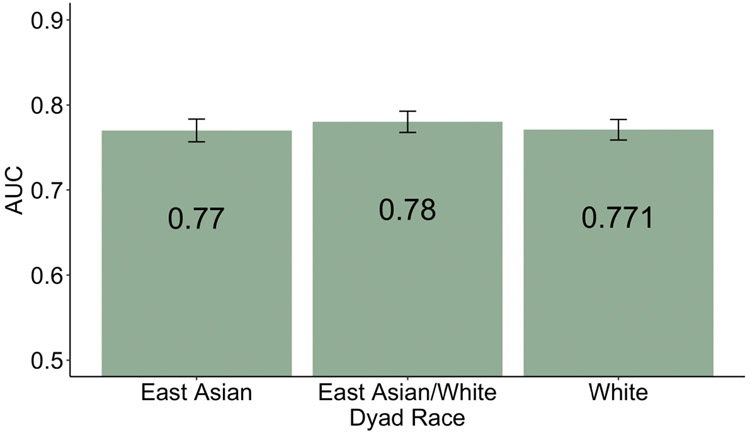

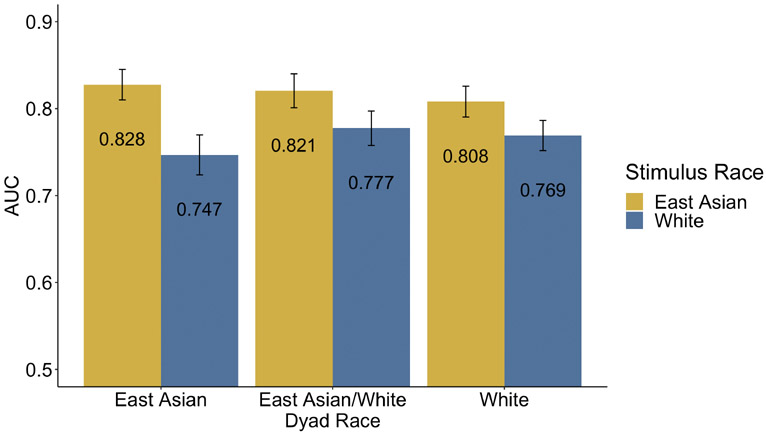

There was no effect of dyad composition, such that accuracy for different-race dyads (East Asian/White dyads; M = 0.78, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.77, 0.79]) was comparable to both types of same-race dyads (East Asian/East Asian; M = 0.77, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.76, 0.78] and White/White; M = 0.77, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.76, 0.78]; see Figure 5). As with Experiment 1, there was an effect of stimulus race, F(1, 151) = 6.06, MSe = 0.01, p < .0001, . Face-identification accuracy was greater for East Asian faces (M = 0.80, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.79, 0.81]) than for White faces (M = 0.75, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.74, 0.76]). This stimulus effect was qualified again by the presence of a significant interaction between stimulus race and dyad composition, F(2, 151) = 3.56, MSe = 0.010, p < .03, ; see Figure 6. Again a partial ORE was mostly likely caused by East Asian dyads' difficulty with White face images. The combination of two East Asian individuals working together to identify White faces resulted in the lowest performance accuracy (M = 0.75, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.72, 0.77]). Performance for East Asian faces was equivalent across the three different racial dyad compositions. No other interactions were significant.

FIGURE 5.

Overall accuracy for different-race (East Asian/White) and same-race dyads (East Asian/East Asian and White/White) was comparable. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 6.

Accuracy for different-race (East Asian/White) and same-race dyads (East Asian/East Asian and White/White) on White (blue) and East Asian (yellow) faces. This shows that differences across dyad race depend on the stimulus race. East Asian same-race dyads have greater accuracy for same-race faces, but this is not true for White same-race dyads. For White dyads accuracy is also greater for East Asian faces. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Collaboration benefits

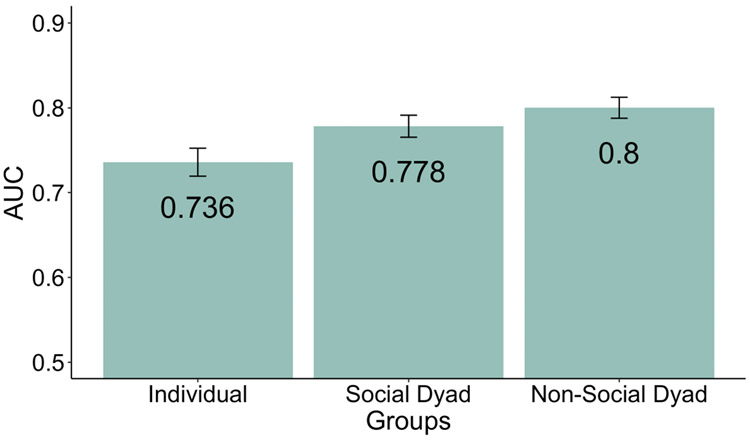

As expected, there was an effect of collaboration type, F(2, 302) = 3.45, MSe = 0.010, p < .0001, ; see Figure 6. Pair-wise comparisons showed that once again, social dyads (M = 0.78, SD = 0.08, 95% CI [0.77, 0.79]) and non-social dyads (M = 0.80, SD = 0.08, 95% CI [0.79, 0.81]) were more accurate than individuals (M = 0.74, SD = 0.10, 95% CI [0.72, 0.75]; p < .0001). Surprisingly, and in contrast to Experiment 1, there was a difference between social dyads and non-social dyads, such that overall accuracy was greater for non-social dyads compared to social dyads (p = .01; see Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Collaboration benefits for overall accuracy. Both non-social dyads and social dyads had greater identification accuracy than individuals. In addition, non-social dyads had greater identification accuracy than social dyads. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Given that this result was inconsistent with Experiment 1, and given that the primary difference between Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 is the inclusion of different-race dyads, one additional exploratory analysis was conducted. An analysis of social versus non-social collaboration without the different-race dyads revealed that the advantage of the non-social dyad had disappeared. For completeness, and to explore this post-hoc analysis finding, the dyad composition means as a function of collaboration type are as follows: East Asian Social Dyads (M = 0.77, SD = 0.13, 95% CI [0.75, 0.79]) and Non-Social Dyads (M = 0.81, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.78, 0.83]); East Asian/White Social Dyads (M = 0.79, SD = 0.11, 95% CI [0.76, 0.81]) and Non-Social Dyads (M = 0.81, SD = 0.10, 95% CI [0.79, 0.73]); White Social Dyads (M = 0.78, SD = 0.09, 95% CI [0.77, 0.80]) and Non-Social Dyads (M = 0.79, SD = 0.10, 95% CI [0.77, 0.81]). These results replicate Experiment 1 and suggest that the benefit of non-social collaboration in Experiment 2 may have been due to different-race dyads benefiting from non-social collaboration to a greater extent than same-race dyads.

The results indicate comparable performance for same-race and different-race dyads, though it remains unclear whether dyads used different strategies when completing the task. Notably, the main goal of this paper was to establish the impact of racial diversity in collaborative face identification decisions. Although for completeness, and in order to begin to explore potential strategies differences for dyad types, we examined computational models of social collaboration similar to those considered in a previous study (Jeckeln et al., 2018). We adapted the methods used in that study for same versus different-race face stimuli. We tested multiple models, including (a) whether people in different-race dyads deferred judgements to the dyad member with the same-race as the face stimulus, (b) whether different-race dyads deferred judgements to the more confident dyad member, and (c) whether same-race dyads deferred to the more confident dyad member. Given we found no clear strategic approach for different-race dyads versus same-race dyads, these simulations are presented in detail in the Supporting Information. In short, in the absence of a significant finding based on the diversity of the dyad, we conclude that individuals may employ stimuli-specific strategies that cannot be summarized as one single strategy.

Order effects

Once again, task order was counterbalanced. However, there was no effect of task order on collaboration type, F(2, 296) = 0.006, MSe = 0.009, p = .99, . A post hoc chi-square test of independence revealed a significant relationship between task order and use of the rating scale (confidence), χ2 (8, N = 6160) = 56.52, p ≤ .00001, only for same-identity pairs. Pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of .005 (.05/9), showed that participants who completed the task with a partner first were more likely to select, “Think they are different” (p = .0006) compared to participants who completed the task with an individually first.

Social experience survey

The majority of participants agreed with the following statements: “My partner and I worked well together” (51%: Strongly agree; 41%: Agree), “I would gladly work with my partner again on other tasks” (52%: Strongly agree; 35%: Agree), and “I felt comfortable voicing my opinion to my partner” (55%: Strongly agree; 34%: Agree). Furthermore, on average, participants reported that both themselves and their partner contributed equally to the task, and a majority of participants agreed with the statement “I felt comfortable letting my partner know when I disagreed” (21%: Strongly disagree; 43%: Agree). For questions related specifically to completing the task online, most participants disagreed with the following statements: “Taking the experiment online made it difficult to complete the task” (36%: Disagree; 38%: Strongly disagree), “Connectivity or internet issues made it difficult to complete the task” (23%: Disagree; 55%: Strongly disagree) and agreed with “Overall, my experience completing the task online was enjoyable” (40%: Agree; 48%: Strongly Agree).

Experiment 2: Discussion

Collaboration increased overall face identification performance, regardless of dyad composition. The lack of interaction between dyad composition and collaboration type (social and non-social dyads) supports the claim that collaboration increases accuracy for both own- and other-race faces. The interaction between dyad composition and stimulus race was driven mostly by differences in identification accuracy for White faces. Across all dyad compositions, accuracy for East Asian faces was consistent. Both collaboration types resulted in greater face identification accuracy compared to individual performance. Seemingly inconsistent with Experiment 1, non-social collaboration accuracy was greater than social collaboration. However, Experiment 2 included different-race dyads. When different-race dyads were removed from the analysis, collaboration type differences disappeared. This result would suggest that social collaboration may be less helpful for different-race dyads than for same-race dyads. Again, participants reported positive interactions with their partner. However, task order did impact how participants used the rating scale but this did not translate to differences in accuracy due to task order.

DISCUSSION

Collaborative decision-making improved own- and other-race face identification accuracy for both social and non-social collaboration. Its effectiveness in racially homogeneous and diverse dyads demonstrates the robustness of wisdom-of-crowds as a recognition strategy. Our results have theoretical and practical implications for understanding other-race face recognition. In particular, we consider the implications for generalizability across social and non-social collaboration and across race.

Despite utilizing distinctive mechanisms, social and non-social collaboration increased face identification accuracy for both own- and other-race face recognition in an online setting. Social collaboration takes advantage of the social feedback between the individuals (Jeckeln et al., 2018) and is driven by the more accurate member of the dyad (Dowsett et al., 2015; Jeckeln et al., 2018). In non-social collaboration, individual item-level responses combine input equally from both members of the dyad (Phillips et al., 2018; White et al., 2013, 2015). Social and non-social collaboration improved performance for same-race dyads equally (Exp. 1), consistent with Jeckeln et al. (2018). The slight advantage of non-social collaboration found in Exp. 2 disappeared when only same-race dyads were retained in the analysis. Notably, the online format of the task still resulted in strong collaboration benefits. These results align with previous research that has explored in-person collaboration for face identification performance (Dowsett et al., 2015; Jeckeln et al., 2018). Although we can speculate about the role of dyad diversity in the advantage for non-social collaboration, the lack of a significant interaction between dyad-composition and collaboration type does not support a strong interpretation. We can conclude, however, that in the conditions tested, social collaboration never proved more effective than non-social collaboration. However, the benefits of non-social collaboration were more consistent than the benefits of social collaboration across experimental factors, such as task order. In Exp. 1, social collaboration benefits were maximized when participants completed the task on their own first and then with a partner. One possibility for this finding is that participants benefited from first working through the task alone to develop their own strategies, and then refining their strategies with their partner. Given we did not find an effect of task order in Experiment 2, we cannot make strong claims about the influence order on these social interactions. Task order impacted levels of confidence, but did not translate consistently to differences in accuracy across the two experiments. The impact of task order on accuracy supports the notion that the benefits of social collaboration can be less predictable than the benefits of non-social collaboration.

The consistently strong benefit of non-social collaboration has been demonstrated in student populations (Jeckeln et al., 2018; White et al., 2013, 2015), with face identification specialists (Phillips et al., 2018; White et al., 2015) and in face recognition algorithms (O'Toole et al., 2007; Phillips et al., 2018). The benefits of non-social collaboration may stem from its ability to avoid the possible negative outcomes of group diversity, such as conflict (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; Moreland et al., 2013). Non-social collaboration can exploit the strengths of different individuals, while avoiding conflict, personality differences and social awkwardness. The overall improvement across collaboration type did not lessen the ORE, suggesting that the mechanisms by which collaboration improves the identification of same-race faces applies also to other-race faces. Therefore, in practical terms, collaboration will not likely improve individual accuracy to the level of own-race recognition.

Racial diversity did not benefit general or race-specific face identification. Its potential for benefiting collaboration may be complicated by a trade-off between diversity and ability (Hong & Page, 2004; Luan et al., 2012; Moreland et al., 2013), in decision-making tasks. The strong and consistent effects of collaboration across the dyad conditions indicate that different and effective strategies among individual participants (rather than groups) are primarily responsible for collaborative benefits. Thus, wisdom of a multiracial crowd is not necessarily more effective than the wisdom of a homogeneous racial crowd.

As a tool for improving face identification accuracy, collaboration has advantages over previous approaches. First, it can be applied to any image. Second, collaboration is more feasible/practical than other approaches used to improve other-race face identification such as learning from individuation training (Tanaka et al., 2004), multiple images (Cavazos, Noyes, & O'Toole, 2019) or caricatured faces (Rodrguez et al., 2008). Third, here we demonstrate that wisdom-of-crowds approaches can yield benefits across different racial groups. The ability for collaborative face identification to improve accuracy in other-race contexts demonstrates its versatility as a tool that can improve performance across various face identification scenarios. These findings suggest that collaboration can be a useful tool that can be implemented in both lab (Jeckeln et al., 2018; White et al., 2013) and applied settings (e.g. forensic facial examiners [Phillips et al., 2018; White et al., 2015]). Finally, previous research demonstrates that collaborative benefits extend to combinations of various identification sources such as human-machine fusion (O'Toole et al., 2007; Phillips et al., 2018) and machine–machine fusion (Phillips et al., 2018) which may prove useful for improving accuracy for other-race faces.

It is possible that the online nature of the task affected the presence or magnitude of collaboration benefits. Participants were encouraged to turn on their webcam, but this was not a perquisite for participating in the task. Given the data were collected at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not feasible to require participants to have access to a camera or a stable internet connection to keep their camera on throughout the experiment. Still, the vast majority of participants used their camera for the entire duration of the study. The lack of visual social cues for some participants had the potential to impact social dyad interactions; however, our results were consistent with previous research conducted in-person (Dowsett et al., 2015; Jeckeln et al., 2018). Notwithstanding, it would be advisable to replicate these findings in an in-person setting where all dyads are exposed to visual information about their partner. Also, the study was limited to two racial groups to enable the selection of images with controlled difficulty measures. Although there is no reason to believe the results would not generalize to other racial groups, this remains to be demonstrated empirically. In addition, future studies would benefit from including stimuli of a different race than both participant groups. This addition would help explore how individuals perform when neither participant has prior “expertise” with a given racial group of face stimuli. Collaboration benefits across age, gender and image property variations should also be explored. Finally, the comparable results across dyad composition suggest that individuals within racial groups may have been using different, but equally efficient, strategies for identifying faces. Given that the main goal of this study was to examine the impact of collaborative face identification decisions in the context of racial diversity, we did not focus on exploring the collaborative process itself beyond the simulated models found in the Supporting Information. Future work may consider how these individual and team approaches differ.

In summary, collaboration produces robust effects across diverse groups, working together socially or through combinations of their judgements, in recognizing faces of their own-race and of other races. This has implications for the usefulness of collaborative decision-making in face identification tasks and addresses a gap in our knowledge about the scenarios in which collaboration is an effective strategy for improving face identification accuracy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health RO1 EY 029692-04 to A.O.T.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

OPEN RESEARCH BADGES

This article has earned an Open Data badge for making publicly available the digitally-shareable data necessary to reproduce the reported results. The data is available at https://osf.io/bvfs7/?view_only=ff4eddeb8a1d438e8d3b12d89d3a1a4e.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available to view in Open Science Frame (OSF) at https://osf.io/bvfs7/?view_only=ff4eddeb8a1d438e8d3b12d89d3a1a4e. Images used in the experiment can be requested via https://cvrl.nd.edu/projects/data/. OSF repository will be made publicly accessible upon manuscript acceptance.

REFERENCES

- Anzures G, Wheeler A, Quinn PC, Pascalis O, Slater AM, Heron-Delaney M, Tanaka JW, & Lee K (2012). Brief daily exposures to Asian females reverses perceptual narrowing for Asian faces in Caucasian infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 112(4), 484–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami B, Olsen K, Latham PE, Roepstorff A, Rees G, & Frith CD (2010). Optimally interacting minds. Science, 329(5995), 1081–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce V, Henderson Z, Newman C, & Burton AM (2001). Matching identities of familiar and unfamiliar faces caught on cctv images. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 7(3), 207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos JG, Noyes E, & O'Toole AJ (2019). Learning context and the other-race effect: Strategies for improving face recognition. Vision Research, 157, 169–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos JG, Phillips PJ, Castillo CD, & O'Toole AJ (2019). Accuracy comparison across face recognition algorithms: Where are we on measuring race bias? arXivpreprint arXiv:1912.07398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu CKW, & Weingart LR (2003). Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGutis J, DeNicola C, Zink T, McGlinchey R, & Milberg W (2011). Training with own-race faces can improve processing of other-race faces: Evidence from developmental prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia, 49(9), 2505–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett AJ, & Burton AM (2015). Unfamiliar face matching: Pairs out-perform individuals and provide a route to training. British Journal of Psychology, 106(3), 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron-Delaney M, Anzures G, Herbert JS, Quinn PC, Slater AM, Tanaka JW, Lee K, & Pascalis O (2011). Perceptual training prevents the emergence of the other race effect during infancy. PLoS One, 6(5), e19858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L, & Page SE (2004). Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(46), 16385–16389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocence Project. (2020). Dna exonerations in the United States. https://www.innocenceproject.org/dna-exonerations-in-the-united-states/

- Jeckeln G, Hahn CA, Noyes E, Cavazos JG, & O'Toole AJ (2018). Wisdom of the social versus non-social crowd in face identification. British Journal of Psychology, 109, 724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavrakas PJ, Buri JR, & Mayzner MS (1976). A perspective on the recognition of other-race faces. Perception & Psychophysics, 20(6), 475–481. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrecht S, Pierce LJ, Tarr MJ, & Tanaka JW (2009). Perceptual other-race training reduces implicit racial bias. PLoS One, 4(1), e4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan S, Katsikopoulos KV, & Reimer T (2012). When does diversity trump ability (and vice versa) in group decision making? A simulation study. PLoS One, 7(2), e31043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malpass RS, & Kravitz J (1969). Recognition for faces of own and other race. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(4), 330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannix E, & Neale MA (2005). What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6(2), 31–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcon JL, Meissner CA, Frueh M, Susa KJ, & MacLin OH (2010). Perceptual identification and the cross-race effect. Visual Cognition, 18(5), 767–779. [Google Scholar]

- McGugin RW, Tanaka JW, Lebrecht S, Tarr MJ, & Gauthier I (2011). Race-specific perceptual discrimination improvement following short individuation training with faces. Cognitive Science, 35(2), 330–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod PL, Lobel SA, & Cox TH Jr. (1996). Ethnic diversity and creativity in small groups. Small Group Research, 27(2), 248–264. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner CA, & Brigham JC (2001). Thirty years of investigating the own-race bias in memory for faces: A meta-analytic review. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 70(1), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Moreland RL, Levine JM, & Wingert ML (2013). Creating the ideal group: Composition effects at work. Understanding Group Behavior, 2, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole AJ, Abdi H, Jiang F, & Phillips PJ (2007). Fusing face-verification algorithms and humans. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics—Part B: Cybernetics, 37(5), 1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PJ, Beveridge JR, Draper BA, Givens G, O'Toole AJ, Bolme D, Dunlop J, Man Lui Y, Sahibzada H, & Weimer S (2012). The good, the bad, and the ugly face challenge problem. Image and Vision Computing, 30(3), 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PJ, Beveridge JR, Draper BA, Givens G, O'Toole AJ, Bolme DS, Dunlop J, Man Lui Y, Sahibzada H, & Weimer S (2011). An introduction to the Good, the Bad, & the Ugly Face Recognition Challenge Problem. International Conference on Automatic Face Gesture Recognition. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PJ, Yates AN, Hu Y, Hahn CA, Noyes E, Jackson K, Cavazos JG, Jeckeln G, Ranjan R, Sankaranarayanan S, Chen J-C, Castillo CD, Chellappa R, White D, & O'Toole AJ (2018). Face recognition accuracy of forensic examiners, superrecognizers, and face recognition algorithms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(24), 6171–6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. (2019). Qualtrics. https://www.qualtrics.com/

- Ranjan R, Bansal A, Zheng J, Xu H, Gleason J, Lu B, Nanduri A, Chen J-C, Castillo CD, & Chellappa R (2019). A fast and accurate system for face detection, identification, and verification. IEEE Transactions on Biometrics, Behavior, and Identity Science, 10(2), 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrguez J, Bortfeld H, & Gutiérrez-Osuna R (2008). Reducing the other-race effect through caricatures. In 2008 8th IEEE international conference on automatic face & gesture recognition (pp. 1–5). IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, & De Schonen S (2004). Recognition of own-race and other-race faces by three-month-old infants. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(7), 1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers SR (2006). On racial diversity and group decision making: Identifying multiple effects of racial composition on jury deliberations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 20(4), 597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surowiecki J (2005). The wisdom of crowds. Anchor. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JW, Kiefer M, & Bukach CM (2004). A holistic account of the own-race effect in face recognition: Evidence from a cross-cultural study. Cognition, 93(1), B1–B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JW, & Pierce LJ (2009). The neural plasticity of other-race face recognition. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 9(1), 122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall J (2015). Pangea: Power analysis for general ANOVA designs. [Google Scholar]

- White D, Burton AM, Kemp RI, & Jenkins R (2013). Crowd effects in unfamiliar face matching. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27(6), 769–777. [Google Scholar]

- White D, Phillips PJ, Hahn CA, Hill M, & O'Toole AJ (2015). Perceptual expertise in forensic facial image comparison. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1814), 20151292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KY, & O'Reilly CA (1998). Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research. Research in Organizational Behavior, 20(20), 77–140. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available to view in Open Science Frame (OSF) at https://osf.io/bvfs7/?view_only=ff4eddeb8a1d438e8d3b12d89d3a1a4e. Images used in the experiment can be requested via https://cvrl.nd.edu/projects/data/. OSF repository will be made publicly accessible upon manuscript acceptance.