Abstract

Enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose feedstocks has been observed as the rate-limiting stage during anaerobic digestion. This necessitated the need for pretreatment before anaerobic digestion for an effective and efficient process. Therefore, this study investigated the impact of acidic pretreatment on Arachis hypogea shells, and different conditions of H2SO4 concentration, exposure time, and autoclave temperature were considered. The substrates were digested for 35 days at a mesophilic temperature to assess the impact of pretreatment on the microstructural organization of the substrate. For the purpose of examining the interactive correlations between the input parameters, response surface methodology (RSM) was used. The result reveals that acidic pretreatment has the strength to disrupt the recalcitrance features of Arachis hypogea shells and make them accessible for microorganisms' activities during anaerobic digestion. In this context, H2SO4 with 0.5% v. v−1 for 15 min at an autoclave temperature of 90 °C increases the cumulative biogas and methane released by 13 and 178%, respectively. The model's coefficient of determination (R2) demonstrated that RSM could model the process. Therefore, acidic pretreatment poses a novel means of total energy recovery from lignocellulose feedstock and can be investigated at the industrial scale.

Keywords: Lignocellulose, Arachis hypogea shells, Pretreatments, Anaerobic digestion, Biogas, RSM

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

AD of Arachis hypogea shells was investigated with H2SO4 pretreatment.

-

•

H2SO4 pretreatment has a significant effect on the structural composition.

-

•

The pretreatment method enhances methane yield effectively.

-

•

Optimum methane yield was recorded at lower treatment conditions.

-

•

RSM model predicted biogas yield with R2 of 0.7892

1. Introduction

Due to the imminent energy challenges of non-renewable fossil fuel sources depleting and environmental concerns due to greenhouse gas emissions, sourcing for clean and sustainable energy origins has gained global attention. Recently, several researchers have focused on renewable energy production because of its eco-friendly and feedstock availability [1]. Global warming, environmental conditions, and sustainable energy development prompt researchers to explore the opportunities to produce cost-efficient and environmentally benign alternative energies [2]. The anaerobic digestion process transforms organic wastes into biogas, a renewable fuel that can serve as an electricity source, vehicle fuel, and heat generation. Recently, the anaerobic digestion of agricultural residues and wastes, organic portions of municipal wastes, sewage sludge, and industrial wastes has been adjudged to be one of the most economical and attractive renewable and sustainable energy origins [3]. This process is a practical and engaging means to recover energy from biomass due to its economy and green energy production advantages. Anaerobic digestion of manure minimizes greenhouse gas emitted to the environment by reducing methane release from natural biodegradation during storage. The use of wastes in renewable energy production will assist in reducing the total reliance on fossil fuels and reduce environmental degradation. Aside from its economic benefits as an energy and fuel source, the anaerobic digestion process provides other environmental advantages.

The biogas released can be upgraded to biomethane through proper purification to remove gases like CO2, H2S, N2, and water and added to the national grid or employed as transport fuel [4] Pig slurry, food, and yard waste were co-digested, releasing high-quality methane gas [5]. Fruit waste and macroalgae were experimented with during the anaerobic digestion, and they were discovered to have a good biogas production potential [6]. Two-fraction of anaerobic digestion was used to recover energy from phytomass waste, and the gas produced was substituted for fossil fuels [7]. The efficient use of biogas could be a vital ingredient for the growth of each geographical location, which can translate into improvement in economic and social cohesion in a country [8]. Producing and using biogas can reduce emissions costs throughout the entire society, promote investment in green and low-carbon industries, and direct capital flows [9]. The digestate from the biogas production process has been observed to have rich nutrients and can be used as a nutrient source in agriculture and provide additional income [10].

Lignocellulose feedstock is one of the most abundant biogas substrates on earth and has been identified to have good potential for biogas production [11]. They are the most attractive alternatives for the anaerobic digestion (second-generation feedstock) because they are abundant, have minimal cost, and do not compete with the food supply [12]. Enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose feedstocks produces different reducing sugars that are highly important in generating biofuels like biogas, bioethanol, phenols, aldehydes, and other organic acids. Nevertheless, due to their microstructural arrangement, lignocellulose feedstocks are difficult to degrade during anaerobic digestion. Most of the lignocellulose feedstock consists of biological polymers like lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose that are firmly arranged through hydrogen and covalent bonds, thereby becoming a highly recalcitrant structure. Lignin present in the lignocellulose materials makes them biopolymeric. It hinders the solubilization rate, restricting the breaking down of hemicellulose and cellulose. Because of these resistant properties of lignocellulose materials, a substantial percentage of the feedstock remains undigested, and biogas is released from only around 50–70% of the volatile solids (VS) of the feedstock [13]. The efficiency of biogas generation from lignocellulose feedstocks relies on the availability of digestible components to exo-exymes released by anaerobic microbes. Therefore, applying pretreatment before digestion can enhance the digestion and increase the biogas and methane release [14] Pretreatments focus is to improve the lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose availability to the enzymes, increasing feedstock's digestion rate. Hence, applying pretreatment to catalyze lignocellulose is profitable for generating economic and eco-benign fuels [15]. The methane yield of sweet potato root waste was improved by 22%, and retention time was reduced by 6 days when pretreated with the thermochemical method compared to the control [16]. Hot air oven was employed to pretreat Water hyacinth, and it was noticed that the COD elimination was 82% and methane generated was between 68 and 71% [17]. Pretreatment with steam explosion was observed to increase the micropore area and the methane released from oat straw, but the pretreatment conditions must be ascertained to lower the inhibitor formation [18].

Nevertheless, pretreatment methods have been observed to release harmful compounds like furan derivatives and furfural, organic acids (acetic, levulinic, and formic), and phenol compounds that can hinder the whole-cell arrangement and mostly reduce the quality and biogas yield [19]. Various pretreatment techniques have been investigated, dependent on the structural properties of the lignocellulose substrate. Biological, thermal, chemical, mechanical/physical, thermochemical, or combination have been studied widely. Some new and improved methods have recently been reported for lignocellulose pretreatment [20].

Chemical pretreatment techniques are a pretreatment technique that is widely studied, and this is due to their efficiency and strength to enhance the digestion of sturdy substrates [21]. Several chemicals like HCl, KOH, H2SO4, H2O2, CH3COOH, and NaOH have been experimented with during the pretreatment of lignocellulose feedstocks before anaerobic digestion [15]. Acidic pretreatment is one of the common methods for lignocellulose feedstock that has been studied widely. Strong and dilute acids (H2SO4, HNO3, or HCl) pretreatment techniques have been investigated at high temperatures, either as a single treatment or in combination with other treatments such as particle size reduction, steam explosion, etc. [22]. Strong acids solubilized lignin and hemicelluloses of lignocellulose substrates, but acid recovery is required. When dilute acid is applied, the lignin portion of the lignocellulose is not solubilized but redistributed. There is also a need to ensure that the substrate's pH is neutral before anaerobic digestion [23]. Despite this pretreatment method's popularity and widespread use, the release of inhibitory compounds makes it unappealing. The toxic and corrosive nature of acids is another challenge associated with the acidic pretreatment method. It requires special digesters with high resistance to corrosion and other acid properties. It was reported that the influence of acidic pretreatments is determined by the structural arrangements of the pretreated feedstock, and it does not have a universal effect [15].

Acidic pretreatment has its advantages and disadvantages. Only when pretreatment methods match substrate structural compositions correctly can the essence of pretreatment be achieved. When hydrochloric acid (2% v/v) was used to pretreatment corn straw, biogas released was improved from 100.6 to 216.7 ml/g VSadded [24]. Using H2SO4 pretreatment experimented on sorghum bicolor stalk, a 545% increase in methane released was noticed. But when the same sorghum bicolor stalk was pretreated with H2O2 and digester under the same anaerobic conditions, a 615% increase in methane yield was recorded [25] Despite many investigations about acidic pretreatment methods, including agricultural residues with fibers, only a few reports the effect on the microstructural arrangement of lignocellulose materials.

Arachis hypogea (groundnut) shells are abundant lignocellulose materials [26], and it is made up of three significant compositions, which include lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose [27]. However, the Arachis hypogea shells' recalcitrant nature cannot be easily digested during the anaerobic digestion process except when it is pretreated before digestion. Previous reports have shown that pretreatment varied with feedstocks. It is impossible to assume that pretreatment methods experimented with on other lignocellulose feedstocks will apply to Arachis hypogea shells [15]. With the available information, there are limited/no literature reports on the acidic pretreatment of Arachis hypogea shells at laboratory or industrial scales. Some available reports affect specific lignocellulose feedstocks with a structural arrangement that differs from that of Arachis hypogea shells. Furthermore, most of these reports focused only on biogas and methane yields without considering their impacts on the microstructural composition of the feedstock.

Therefore, this study aims to understand and elucidate the impacts of acidic pretreatment on the microstructure and biogas released from Arachis hypogea shells. The main objectives can be elaborated further as follows: (i) pretreatment of Arachis hypogea shells with H2SO4, (ii) study the effects of pretreatment on microstructure, crystallinity, and functional groups, (ii) compare the effects of the different treatment conditions on biogas and methane from anaerobic digestion of the pretreated and untreated Arachis hypogea shells, and optimization of the processing parameters using RSM. The investigations included microscopy (SEM), spectroscopy (FTIR and XRD), and anaerobic digester. It is worth mentioning that to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to perform such a study in terms of the feedstock considered and the pretreatment method used. The results from this research are expected to be helpful as a baseline for further research on lignocellulose feedstocks and subsequent application on the industrial scale.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Substrate collection

Arachis hypogea (groundnut) was sourced locally, and the shells were removed, dried at room temperature, and kept in a well-ventilated environment at 4 °C for further use. The untreated and pretreated substrate were then examined for lignin, celluloses, hemicelluloses, total solids, ash contents, volatile solids, carbon, nitrogen, and Sulphur using the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) standard method [28].

2.2. Inoculum

Stabled inoculum from a previous digester where cow manure and kitchen wastes were co-digested at ambient conditions was collected and used for this study. Physicochemical analysis to determine the total solids, ash contents, volatile solids, Sulphur, nitrogen, and carbon. The inoculum was put in bottles and kept at 4 °C before anaerobic digestion.

2.3. Experimental design of pretreatment and analysis for response surface methodology

Response Surface Methodology (RSM), which has been adjudged to be dependable and efficient for designing experiments in bioprocess, was utilized to study process optimization [29]. RSM can predict the optimum process conditions for the experiment [30] and shows the interactive effects of the selected individual parameters. The Central Composite Design (CCD) of the RSM was utilized to design the acidic pretreatment used in the study. Acid (H2SO4) concentration (% v. v−1), exposure time (minutes), and autoclave temperature (°C) were the process variables that served as inputs for the pretreatment. The interactive influence of the independent parameters and biogas and the optimum conditions for the yield were also studied with the RSM model developed [31]. RSM model was introduced through Design-Expert software (13.0 version), and retention time, acid concentration, exposure time, and autoclave temperatures were represented with R, X, Y, and Z, respectively. The preliminary information was used to vary the independent process parameters across levels between −1 and +1 using the experimental ranges [32]. Thirty experimental runs for the selected process parameters (F) were determined using equation (1), and equation (2) was used to calculate the response. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was utilized to generate a polynomial equation of second order used to forecast the biogas yield [33].

| (1) |

Where: e = the number of factors (e = 4), and 6 is a constant factor.

| (2) |

Where: X is the measured response, is the intercept term, are quadratic coefficient, are interaction coefficient, and are the coded independent variables.

2.4. Acidic pretreatment

Sulphuric acid (H2SO4), which has been reported to reduce lignin and remove almost all the hemicellulose components of lignocellulose materials [25,34], was adopted for this work. The main merit of this technique is that it requires small energy, and the quantity of acid needed makes it economical. Therefore, it is a profitable and efficient means of converting Arachis hypogea shells into enhanced biogas and methane. In an autoclave, moist steam was used to apply concentrated H2SO4 to the substrate (SIGMA-ALDRICH, ACS Reagent, 95.0–98.0%, purchased for the experiment from Sigma-Aldrich (pty) Limited, Johannesburg, South Africa). The input factors were H2SO4 concentration (% v. v−1), exposure time (min), and autoclave temperature (°C). The values for H2SO4 concentration were 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2% v. v−1, with exposure times 15, 25, 35, and 45 min, and autoclave temperatures of 90, 100, 110, and 120 °C. These values were adopted based on previous reports on similar research with slight modifications [25,34]. The pretreatment was carried out using a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1: 10 for all the treatment conditions because of the substrate moisture contents, as reported in previous studies [35].

2.5. Substrate microstructural characterization

Under a scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the microstructural characterization of the H2SO4 treated and untreated feedstock was looked at (VEGA 3 TESCAN X-Max, Czech Republic). The SEM analysis was replicated twice, and the images were picked at 400× magnification. Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) system (EDAX, Smart Insight, Australia) was also employed to verify the impacts of treatment techniques on the elemental composition of the substrate during the SEM analysis. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) (IRAfinity-1, Japan) was utilized to observe the influence of pretreatment on the substrate's functional group, which was observed between 4000 and 500 cm−1. The level of the substrate cellulose crystallinity after pretreatment was studied under X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) (D-8 Advance, Indiana, USA) and studied at ranges 5–35 °C with 5 °C/min speed and diffraction angle (2Ө). The crystallinity index was determined from the empirical XRD results using equation (3) [36].

| (3) |

Where: Ic = Crystallinity index, Imax = Highest diffraction at peak position at 2Ө = 22.23°, and Ix = intensity at 2Ө = 18°

2.6. Experimental setup

Anaerobic digestion of the substrates was examined in a laboratory-scale batch digester following the European standard technique [37]. Round bottom narrow neck bottles (Schott Duran 10,091,871, Germany) with 1000 ml capacity were utilized as digesters. 500 ml ultra-clear calibrated polypropylene (LMS Boro 3.3, Germany) was mounted on the digesters for gas storage. The gas yield was measured through water displacement techniques; therefore, the gas storage bottles were connected with the laboratory glass bottles of 500 ml inner volume with silicon pipes (Schott Duran 10,093,435, Germany). The digesters were charged with the recommended mass of stabled inoculum. Each digester was charged with the calculated quantity of substrate using 2: 1 of the substrate to inoculum (S: I) using equation (4) [37]. The treatments were duplicated twice. Before the commencement of the digestion process, lime water was introduced to the digesters to adjust the pH to 7.0. Helium gas was used for flushing each digester for 3 min to get rid of oxygen and set anaerobic digestion. The experiment was carried out at a mesophilic temperature; reactors were arranged in a 40-L thermostatic water bath preset at 37 ± 2 °C and maintained throughout the digestion process. The same mass of inoculum without substrate was also run parallel in two digesters, and the gas released was subtracted from gas generated by the reactors with both substrate and inoculum to determine the actual gas yield. To remove gas trap, break lump and scum, digesters were manually shaken daily, and the process was discontinued when it was observed that the daily biogas generated was less than 1% of the cumulative biogas released by day 35.

| (4) |

where: Ms stands for mass of substrate (g), Mi for mass of inoculums (g), Cs for substrate concentration (%), and Ci for inoculum concentration (%). 80% of the reactor's volume was filled with inoculum [37].

2.7. Analytical methods

The physicochemical characteristics of the substrate and inoculum were analyzed to determine their level of composition. Total solids (TS), percentage ash, volatile solids (VS), and moisture content were investigated according to the methods set forth by the Organization of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) [28]. Percentage cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose were ascertained using the process reported by Van Soest et al. [38]. Elemental analyzer, (Vario Elcube, Germany) was utilized to study the percentage of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and Sulphur, while oxygen was calculated using the assumption of O + C + N + H = 99.50% [39]. The calculation was carried out on a volatile basis. The quantity of gas generated was taken daily through the water displaced in the calibrated ultra-polypropylene gas storage bottles. The quality of gas generated was investigated at intervals based on gas released using a gas analyzer BioGas 5000 gas analyzer (Geotech, GA5000, UK). The following information was also noted down daily: atmospheric temperature and pressure, day, date, and time. Equations (4)–(7) was applied to normalize the gas generated [37].

| (5) |

| (6) |

Where F = Gas factor, P = Air Pressure, t = Gas temperature (°C) Po = Atmospheric Pressure (1013.25 mbar), To = Atmospheric Temperature (273.15 K).

| (7) |

Where: yo = −4.3905; a = 9.762 and b = 0.0521

| (8) |

2.8. Theoretical methane yield (TMY)

The theoretical methane concentration was calculated using the substrate's stoichiometry composition with equations (8), (9)) [40].

| (9) |

| (10) |

2.9. Biodegradability

The biodegradability (Bd) of the anaerobic digestion process was determined on theoretical methane yield (TMY) and experimental methane yield (EMY) following Elbeshbishy equation (10) [41].

| (11) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Feedstock characterization

3.1.1. Physicochemical characteristics of untreated feedstock and inoculum

Table 1 presents the physicochemical properties of untreated substrate and inoculum. It can be noticed from the table that the substrate consists of 99.87% VS and 100%, which implies 99.87% VS to TS portion. This implies that the feedstock has a very high organic content that can be translated into biogas during anaerobic fermentation. It can be observed that the substrate has higher biogas production potential compared to volatile solids of some lignocellulose feedstocks: dairy manure (84.7 ± 2.4%), rice straw (74.9 ± 0.2%), and corn straw (75.05 ± 0.3%) [42]. It can be noticed from Table 1 that the feedstock consist of 27.67% lignin, 17.80% hemicellulose, and 37.30% cellulose which represents 82.77% lignocellulose. It has been observed that lignocellulose content above 75% will restrict hydrolysis, requires longer retention time, and produce low biogas, making the process uneconomical [43]. The lignocellulose content of this substrate is above 75%, and it will require appropriate pretreatment techniques for effective digestion. The organic content of the substrate was calculated to be C27·55H43·55O30·55N when the elemental components of the substrate were considered, and the TMY was calculated using equation (9).

Table 1.

Proximate Analysis of the feedstock and Inoculums.

| Parameter (%) | Feedstock | Inoculum |

|---|---|---|

| Lignin | 27.67 | NA |

| Cellulose | 37.30 | NA |

| Hemicellulose | 17.80 | NA |

| Volatile Solid (VS) | 99.87 | 99.51 |

| Total Solid (TS) | 100.00 | 3.57 |

| Ash content | 0.12 | 0.47 |

| C/N ratio | 26.23 | 8.45 |

| Moisture content | 0.00 | 96.43 |

| Crude fibre | 9.46 | 0.45 |

| Protein | 20.05 | 4.26 |

| Sulphur | 0.53 | 0.60 |

| Hydrogen | 4.79 | 5.50 |

| Oxygen | 53.81 | 46.93 |

| Crude lipid | 0.63 | 6.15 |

NA – Not Applicable.

Where x = 43.55, a = 27.55, y = 30.55 and z = 1

TMY = 286.08 mLCH4/gVSadded

3.1.2. Physicochemical properties of pretreated feedstock

The total and volatile solids of pretreated Arachis hypogea shells were also determined following the official Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) methods [28]. The TS recorded was 99.00, 75.00, 98.50, and 66.67% for treatments A, B, C, and D, respectively. The investigation also revealed that acid pretreatment affected the feedstocks' VS. The VS recorded was 100, 100, 85.71, 100, and 82.23% for treatments A, B, C, D, and E, respectively. Compared with the untreated substrate, H2SO4 pretreatment influences the VS of the feedstocks. The results indicate that with the rise in the H2SO4 concentration, the VS decreases, which means some percentage of VS was lost during the pretreatment process.

The result here supports what was previously noticed that pretreatment with H2SO4 has a significant influence on VS of lignocellulose materials [44]. During the SEM analysis, the elemental composition was investigated with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) system (EDAX, Smart Insight, Australia), and the results are reported in Table 2. The results indicate that pretreatment with H2SO4 reduces the carbon content of Arachis hypogea shells by between 6.51 and 37.16%. It can be inferred from the effect that the lowest carbon content was recorded when the acid: water was 1:1 and showed that as the percentage of H2SO4 keeps increasing, it reduces the available carbon. In the same way, the available oxygen was higher when the acid: water was 1:2, which is a sign that the water added to the acid added some percentage of oxygen to the substrate, making it higher than that of the control that had no moisture content shown in its TS. It can be reported from the result that a higher concentration of H2SO4 reduces the available oxygen in the substrate, as shown in Table 2. The percentage of the sulphur present was increased with H2SO4, indicating that a certain percentage of sulphur from the acid was used to form a compound with the substrate during the pretreatment process. Substrate carbon content determines the rate of food available for the methanogens during digestion, and it dictates the biogas and methane release [45]. During the anaerobic digestion of lignocellulose materials, the substrate with lower oxygen has been adjudged to generate the best biogas and methane. This is because the system operates in anaerobic digestion, and oxygen is not required as it will harm the microorganisms. Higher sulphur content in the substrate signifies that the biogas composition will have higher hydrogen sulphide (H2S), reducing methane yield. The sulphur will react with some of the hydrogens expected to be used by methanogens to produce methane and release H2S instead of methane. Biogas with higher content of H2S is regarded as impure fuel, and it will require further processing before usage, which may make the process uneconomical [46].

Table 2.

Elemental composition of pretreated and untreated Arachis hypogea shells (%wt).

| Treatments | Carbon | Oxygen | Sulphur |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 56.80 | 38.66 | 3.87 |

| B | 44.11 | 37.56 | 17.53 |

| C | 54.01 | 31.92 | 12.94 |

| D | 54.86 | 31.86 | 12.52 |

| E (Control) | 60.50 | 36.70 | 0.30 |

3.2. Alterations in microstructural characteristics

3.2.1. Morphological alterations analysis

The effect of H2SO4 on the morphological arrangement was studied under Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The morphological images of acid pretreated and untreated feedstock picked from the SEM analysis are illustrated in Fig. 1 for comparison. The SEM image of the untreated substrate (E) showed a more intact and smoother surface with several fiber layers resisting microbial activity during anaerobic digestion. The cell walls of untreated Arachis hypogea shells were significantly changed when H2SO4 was applied as pretreatment. The original intact and smooth surfaces were destroyed, loose, and separated, which can be noticed from morphological images after pretreatment (Fig. 1A–D). Coarseness and defibrillation of the substrate surface reduced as the volume of acid increased. Defibrillation and coarseness of the feedstock improved when the ratio of acid to water was 1: 2.

Fig. 1.

SEM images of (A) 0.5 v. v−1 H2SO4 for 15 min, (B) 1.0 v. v−1 H2SO4 for 25 min, (C) 1.5 v. v−1 H2SO4 for 35 min, (D) 2.0 v. v−1 H2SO4 for 45 min, and (E) untreated substrate.

Most importantly, the image in Fig. 1A was more swollen and showed higher fiber fragments on its surface. The images from treatment B (Fig. 1B) damaged the morphological structure of Arachis hypogea shells. Still, its internal tissue exposure was minimal, which may hinder the microorganisms' activities during the digestion process. Other pretreated groups (Fig. 1C and D) produced salient results that imply that they can improve biogas yield. The performances from these pretreatment groups showed that a certain percentage of lignin was removed during the process, and improvement in cellulose and hemicellulose exposure to microbial degradation was observed. This result is consistent with what was recorded when the proximate characteristics of the pretreated feedstock were considered. The result indicates that pretreatment of Arachis hypogea shells with a lower concentration (1:2) of H2SO4: water for 15 min at a temperature of 90 °C produced a better morphological result compared to other treatment conditions. The results here corroborate what was previously observed in the literature that pretreatment of lignocellulose materials significantly affects their morphological structure [47]. Structural disruption was noticed from SEM images when sugarcane bagasse was treated with dilute sulphuric acid [48]. Pretreatment with H2SO4 was reported to alter the morphological structure of the oil palm's front [49].

3.2.2. Analysis of crystallinity modifications

Lignocellulose materials are composed of crystalline and non-crystalline microstructures, lignin and hemicellulose are considered amorphous structures, and cellulose is regarded as a crystalline structure [50,51]. X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD) was utilized to investigate the crystalline arrangement of pretreated and untreated Arachis hypogea shells. Fig. 2a illustrates the diffraction pattern of pretreated and untreated substrates. Fig. 2a shows that the cellulose diffraction peak of the processed feedstock was sharper than the untreated feedstock, indicating that the acid pretreatment increased the intensity. A similar XRD pattern trend was noticed from all the pretreated feedstocks, and changes were recorded at 2Ө of 22.23° and 18° due to crystalline differences. The salient peak of all the samples was noticed at 22.23° for 2Ө, respectively. The principal peak from Imax planes shows the crystal region's diffraction intensity.

Fig. 2.

(a) XRD patterns of untreated and pretreated Arachis hypogea shells. (b) FTIR spectra of pretreated and untreated Arachis hypogea shells.

The crystallinity index (Ic) of H2SO4 pretreated and untreated samples were 59.15, 41.49, 37.77, 32.08, and 55.79% for A, B, C, D, and E, respectively. This shows that pretreatment with 1: 2 of acid: water improved the crystallinity of the feedstock by 6.02%. It can be noticed that other treatment conditions harmed the crystalline structure of the feedstock. This implied that diluting H2SO4 acid with 200% water for 15 min at an autoclave temperature of 90 °C had a synergetic effect of separating non-crystalline lignin and hemicellulose from other treatment conditions. Therefore, treatment A recorded the highest Ic values and is expected to enhance the digestion of Arachis hypogea shells. Previous research also observed that pretreatment enhanced the Ic of feedstock [48]. This is due to the reduction in lignin facing the region, making the crystal region better and improving the crystallinity Ic. The lower crystallinity values reported for treatments B, C, and D against the untreated substrate showed a decrease in cellulose content, indicating that higher concentration of H2SO4, longer treatment time, and higher autoclave temperatures decrease the crystallinity index of the feedstock.

In addition, the increase in diffraction intensity recorded in the amorphous portion and diminution is noticed in the crystalline region (treatments B, C, and D) can be traced to the ability of the strong acid with higher treatment time and temperature to recrystallize the cellulose crystal region [52]. The XRD results also showed a partial reduction of amorphous contents like lignin and hemicellulose through lower concentrations of H2SO4, treatment time, and temperature. Still, the higher concentrations of H2SO4, treatment time, and autoclave temperature increased the lignin and hemicellulose structure. Zhao et al. [53] noticed that crystalline cellulose hinders microbial attack more than amorphous cellulose. The results support what was previously observed that dilute H2SO4 has a significant influence on the crystallinity of lignocellulose feedstocks [25]. It also buttressed what was previously recorded: the structural arrangement of lignocellulose materials determines the influence of acidic pretreatment [15]. The impact of crystallinity on the enzymatic degradation of lignocellulose materials has been examined in some literature. There is no agreement on the impact of crystallinity on enzymatic degradation since other factors are the same or more vital. For instance, hydrolysis of lignocellulose materials pretreated with dilute acid was investigated. It was reported that Ic values do not directly relate to the enzymatic digestion of the materials [54]. But an indicative negative relationship between microbial hydrolysis and Ic values at high enzyme loadings was reported in a similar study. The study also noted that the influence of Ic on enzymatic degradation could be studied without enzymes being a hindrance factor [55].

3.2.3. Analysis of functional group modifications

The influence of dilute Sulphuric acid pretreatment on the functional group composition of Arachis hypogea shells and untreated feedstock was investigated using FTIR spectra. The detailed characterization and the spectroscopy outcomes are illustrated in Fig. 2b, and Table 3 shows the spectrum peak assignments according to the literature [56]. Similar trends were observed in all the samples until 3402 cm−1 wavenumbers were reached (Fig. 2b). The vibration intensity found at 3402 cm−1 can be linked to O–H vibration in the untreated substrate became weaker as acidic pretreatment was applied. This indicates that the cellulose's intramolecular and extra molecular hydrogen bonds were disintegrated, which improves the digestion of cellulose since the breakdown of hydrogen bonding can modify the arrangement of the feedstock and enhance the availability of cellulose content during the anaerobic fermentation process. The nutation at 2927 cm−1 indicated –CH and –CH2 straining nutation in the same vein. This is a sign of partial destruction of the carbon chain leading to the loss of some cellulose after acidic pretreatment. Around 2372 cm−1, carbonyl bands are found and can be linked to the hydroxyl C O distortion palpitation. The ester functional groups are linked to hemicelluloses and celluloses associated with ketones and carboxylic compounds [57].

Table 3.

FTIR spectrum peak assignments of Arachis hypogea shells after H2SO4 pretreatment under different conditions.

| Number | Wavenumber (cm−1) | Functional group | Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3402 | O–H stretching oscillation | Cellulose hydrogen link bond. |

| 2. | 2927 | CH and CH2 up stretching oscillation. | Methyl/methylene cellulose |

| 3. | 2372 | C=O asymmetric deflecting oscillation of xylan. | Lignin and hemicellulose elimination. |

| 4. | 1652 | C=C aromatic ring strenuous oscillation. | Lignin removal |

| 5. | 1623 | C=C aromatic ring oscillation. | Structural changes in lignin. |

| 6. | 1154 | C–O–C distortion oscillation. | Acetyl-lignin group segmentation. |

| 7. | 1017 | C–O twisting oscillation. | Hemicellulose and cellulose. |

| 8. | 869 | -CH deflecting oscillation in the plane. | Amorphous cellulose. |

This characteristic can be easily identified in the untreated substrate, and it was noticed that it disappeared little by little in all the treated samples. It showed that eliminating a substantial content of lignin could be linked to the extinction of the carbonyl. The strength of oscillations at 1625 cm−1 and 1623 cm−1 is attributed to the C C straining of the aromatic ring and the C C aromatic structure oscillation in lignin. After acidic pretreatment, the strength was reduced at various stages within the substrate samples. The palpitation strength at 1154 cm−1 indicates the C–O–C elongating vibration is more visible in the untreated substrate and comparably reduced as the concentration of H2SO4 was improved, which confirmed the elimination of lignin.

Nevertheless, the strength of the oscillation at 1017 cm−1 represents the C–O elongating palpitation in hemicellulose and cellulose. The moderately reduced strength indicated that the hemicellulose and cellulose portions were debased by acid pretreatment. There was no noticeable variation to consider the peak at 869 cm−1 for treatments A, C, and E, other than treatments B and D. This portion presents the C–H deflecting vibration in the plane of the cellulose and is most influenced by the higher acid concentration.

3.3. Biogas and methane potential

The pretreated and untreated Arachis hypogea shells were subjected to anaerobic digestion to study the effect of pretreatment on biogas and methane yields. The cumulative biogas released was 134.38, 92.02, 119.02, 85.07, and 60.56 ml g−1VSadded for treatments A, B, C, D, and E, as presented in Fig. 3a. Compared to the untreated substrate, this result showed a biogas yield increase of 122, 52, 85, and 40% for treatments A, B, C, and D, respectively. It can be inferred from Fig. 3a that all the treatments showed slow improvement in biogas production at the beginning, a substantial improvement in the mid-phase, and a progressive lower yield in the later phase until it managed to be gentle for total biogas released during anaerobic digestion. There was a very small (8.17%) increase in biogas yield between treatments B and D total biogas yield, while treatment A showed an apparent disparity due to its pretreatment conditions. Fig. 3b shows the total methane released from the pretreated and untreated substrate. Cumulative methane yields recorded are 105.22, 60.64, 84.97, 61.42, and 37.85 ml g−1VSadded for treatments A, B, C, D, and E. Compared to the untreated substrate, this represents 178, 60, 124, and 62% improvement for treatments A, B, C, and D. This findings tallies with what was previously observed that acid pretreatment enhances the biogas generated from lignocellulose feedstocks [58,59]. Palm fiber was pretreated with a 5% concentration of H2SO4 at 120 °C for 30 min, and a 14% improvement in yield was observed, much less than the efficiency observed in this study [60].

Fig. 3.

Total biogas yield of acid pretreated and untreated substrate. Total methane yield of acid-pretreated and untreated feedstock.

The variations in the pretreatment effect can be traced to the higher concentration of H2SO4, exposure time, and temperature applied. It can be noticed from this research also that the optimum yield was recorded when the lower concentration of acid, time, and temperature was combined. This shows that a lower concentration of H2SO4 at low temperatures and exposure time is required during acidic pretreatment of Arachis hypogea shells. Likewise, this research results support what was observed by Taherdana et al. [61] when 1% v/v of H2SO4 was used to pretreat wheat plants at room temperature for 60 min. Their findings established that a low concentration of H2SO4 increases the biogas and methane yield better than a higher concentration, and this result from this work confirmed that too. When rice straw was pretreated with H2SO4 before anaerobic digestion, the reducing sugar increased by 91%, implying that the pretreatment technique could eliminate lignin and hemicellulose from the substrate and enhance the biogas yield [62]. This result further justified the necessity to pretreat lignocellulose feedstocks before anaerobic digestion to enhance the biogas and methane generated and shorten retention time, as observed in the previous literature [27]. On the contrary, when the same pretreatment conditions for H2SO4 were applied to the sorghum bicolor stalk, methane yield reduced from 55% to 54.5% [25]. This finding validates what was earlier observed: the effect of pretreatment methods on lignocellulose materials relies on the microstructural arrangement of the feedstock [15].

Pretreatment with dilute H2SO4 can be seen to have the ability to lower the concentration of hemicellulose in all the treatment conditions used for this experiment. It implies that the acid broke down some critical bonds like hydrogen and covalent bonds. Likewise, van der Waals in the substrate improves hemicellulose solubilization and incomplete cellulose solubilization during anaerobic digestion, as Baadhe et al. [52] reported. Acid pretreatment hydrolyzed the xylose portion of the Arachis hypogea shells to monosaccharides, leading to higher hemicellulose depolymerization seen in the biogas and methane yield of this experiment. The previous reports indicated a substantial loss of hemicellulose and incomplete removal of cellulose from corn stalk when it was pretreated with acid [63]. When sunflower oil residue was also pretreated with H2SO4, it was reported that a vast amount of hemicellulose was dissolved [64]. The optimum condition for the most effective acidic pretreatment of the Arachis hypogea shells was applying an H2SO4 concentration of 0.5% v. v−1, an exposure time of 15 min, and an autoclave temperature of 90 °C. The result of this study can be compared with the observations of Cai et al. [65] and Li et al. [66], who also applied a lower concentration of H2SO4 with a more low exposure time to produce the optimum results. Compared to other lignocellulose materials, the yield reported in this study is higher. The wheat plant was pretreated with H2SO4 for 60 min, and the methane yield was enhanced by 8.9% [67], and cassava residues pretreated with thermal-diluted sulphuric acid improved the methane yield by 56.96% [68]. In another related study, Salvinia molesta pretreated with H2SO4 was enhanced by 82% compared to the control experiment [69]. These results are not the same as the ones from this study due to the variation in the microstructural arrangement of the substrates used. The concentration, autoclave temperature, and purity of the acid used could also be attributed to these differences. The major limitations of this process are the huge investment cost, the need for equipment with high corrosion resistance, the toxicity of the process, and the production of inhibitory compounds. Compared with other pretreatment methods, it can be observed that there is a significant difference in biogas yield. A methane production of 410.9 ± 17.9 m3 tVS−1 was recorded when greenhouse waste was pretreated with a disintegrated macerator in 75–95 °C hot water [70]. Rapeseed straw pretreated with the steam explosion at 80–90 °C released an optimum methane yield of 345.3 m3 tVS−1 [71]. The comparison is not that easy due to the variation in the feedstock. Likewise, it should be noticed that the result here is at the laboratory scale, whereas some of these results have been experimented with at the industrial scale. This method could be improved by adding other pretreatment techniques, as reported that the combination of two or more methods produces better yields than individual pretreatment methods. The process can be duplicated on other lignocellulose feedstocks, especially the materials that have a similar structural arrangement with Arachis hypogea shells. The impacts of pretreatment on the biogas and methane yields can be predicted before the experiment using artificial intelligence models [72,73].

Biodegradability (Bd) is the ultimate indicator for stable optimum anaerobic digestion. Bd of 37, 21, 30, 21, and 13% was noticed for treatments A, B, C, D, and E. Bd of pretreated Arachis hypogea shells was significantly improved by 64, 38, 55, and 38% for treatments of A, B, C, and D, compared to the untreated substrate. This result shows that the pretreatment technique significantly increased the Bd of Arachis hypogea shells. The process was steady, and the methane generation rate was excellent. Improved methane yield generation from lignocellulose materials will reduce the effect of international oil market prices on many countries' macroeconomics, especially developing countries [74]. Effective and efficient biogas production from relatively cheap and available lignocellulose feedstocks can reduce oil importation and lower the pressure on the country's foreign exchange [75].

3.4. Optimization of biogas yield with RSM

RSM's central composite design (CCD) was used to make 30 runs based on experimental results. The result of the RSM predicted value for biogas and methane to inputs variables is illustrated in Table 4a. The result in the table implies that all the input parameters influence the biogas and methane yields. For example, runs 20, 22, and 25 have the same retention time with differences in other input parameters; the biogas and methane yields are different. Runs 1, 3, and 16 have the same acid concentration, exposure time, and temperature, but different retention times show differences in biogas and methane yields.

Table 4a.

Experimental and RSM model biogas and methane yields of Arachis hypogea shells.

| Run | R | X | Y | Z | Biogas yields (ml) |

Methane yields (ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. | Pred. | Exp. | Pred. | |||||

| 1 | 3 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 147.05 | 137.78 | 93.08 | 102.85 |

| 2 | 8 | 2.00 | 45 | 120 | 129.15 | 126.69 | 87.75 | 93.21 |

| 3 | 9 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 97.93 | 108.90 | 66.70 | 60.83 |

| 4 | 5 | 1.00 | 25 | 100 | 154.80 | 167.10 | 100.20 | 100.97 |

| 5 | 11 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 106.80 | 72.97 | 75.70 | 51.00 |

| 6 | 9 | 2.00 | 45 | 120 | 106.88 | 104.01 | 82.35 | 77.33 |

| 7 | 4 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 160.09 | 179.61 | 149.33 | 136.52 |

| 8 | 3 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 124.57 | 121.78 | 81.56 | 67.63 |

| 9 | 5 | 2.00 | 45 | 120 | 180.68 | 179.72 | 141.53 | 131.23 |

| 10 | 8 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 106.80 | 138.50 | 73.92 | 101.54 |

| 11 | 10 | 2.00 | 45 | 120 | 81.00 | 84.94 | 55.80 | 65.31 |

| 12 | 3 | 2.00 | 45 | 120 | 146.93 | 146.91 | 87.08 | 94.35 |

| 13 | 12 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 80.95 | 81.85 | 112.94 | 105.59 |

| 14 | 19 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 63.62 | 59.59 | 46.02 | 42.63 |

| 15 | 5 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 215.02 | 181.29 | 155.66 | 134.62 |

| 16 | 10 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 94.45 | 89.10 | 38.81 | 56.69 |

| 17 | 4 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 133.45 | 165.37 | 87.42 | 115.43 |

| 18 | 5 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 189.20 | 191.40 | 135.83 | 140.48 |

| 19 | 9 | 1.00 | 25 | 100 | 53.40 | 112.73 | 75.60 | 85.45 |

| 20 | 6 | 1.00 | 25 | 100 | 198.00 | 167.79 | 112.60 | 109.17 |

| 21 | 12 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 71.97 | 61.11 | 57.57 | 45.13 |

| 22 | 6 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 207.02 | 177.63 | 148.73 | 133.91 |

| 23 | 16 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 54.02 | 70.07 | 55.80 | 71.23 |

| 24 | 9 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 89.03 | 113.81 | 77.83 | 81.16 |

| 25 | 6 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 198.00 | 182.50 | 130.53 | 125.74 |

| 26 | 7 | 2.00 | 45 | 120 | 146.93 | 149.86 | 115.65 | 110.28 |

| 27 | 17 | 2.00 | 45 | 120 | 89.10 | 88.54 | 55.35 | 53.80 |

| 28 | 10 | 1.00 | 25 | 100 | 135.00 | 93.58 | 89.20 | 82.00 |

| 29 | 7 | 0.50 | 15 | 90 | 164.64 | 161.17 | 103.54 | 102.06 |

| 30 | 7 | 1.50 | 35 | 110 | 151.22 | 161.39 | 104.84 | 120.80 |

3.4.1. Interactive influence of input variables on biogas yield

As presented in Table 4b, the F-value recorded is 4.61, implying that the model is significant for biogas yield from pretreated Arachis hypogea shells. The possibility that an F-value this big could be recorded due to noise is 0.25%. The P-values below 0.0500 shows that the model terms are significant, and values above 0.1000 mean the model terms are insignificant. The signal-to-noise ratio is calculated for sufficient precision measure by isolating the difference between the variables' highest and lowest predictive responses. A ratio above 4 is required [76], and the adequate signal ratio recorded is 6.643, which indicates a sufficient signal. This implies that this model can be employed to boycott the design space [77]. The linear process parameters of retention time (A), acid concentration (B), exposure time (C), and autoclave temperature (D) were not significant (P < 0.05). But the quadratic model term of retention time (A2) showed that the process parameter had an individual influence on biogas yield. The interactive effect of the entire process parameters was insignificant (p < 0.05), as illustrated in Table 4b. The final regression terms can be presented in second-order polynomial equation (11) to interpret the biogas yield. Equation (11) can assist in studying the relative impact of the factors compared to the coefficients.

| (12) |

Table 4b.

Regression analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the model for biogas yield.

| Sources | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-R | 2732.44 | 1 | 2732.44 | 3.24 | 0.0908 | |

| B-X | 35.47 | 1 | 35.47 | 0.0420 | 0.8401 | |

| AB | 273.26 | 1 | 273.26 | 0.3239 | 0.5772 | |

| BC | 3.72 | 1 | 3.72 | 0.0044 | 0.9479 | |

| A2 | 4769.29 | 1 | 4769.29 | 5.65 | 0.0302 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| Model | 50542.83 | 13 | 3887.91 | 4.61 | 0.0025 | Significant |

| Residual | 13499.76 | 16 | 843.74 | - | - | - |

| Cor Total | 64042.60 | 29 | - | - | - | - |

| Std. Dev. | 29.05 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mean | 129.26 | - | - | - | - | - |

| C·V. % | 22.47 | - | - | - | - | - |

| R2 | 0.7892 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adj. R2 | 0.6179 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pred. R2 | 0.6504 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adeq. Precision | 6.6427 | - | - | - | - | - |

A – Retention time, B – concentration of acid, C – exposure time, D – autoclave temperature.

The polynomial equation's correlative coefficient (R2) for biogas yield was 0.7892. The value of R2 indicated the measure of variability in the observed response values, which independent factors could determine. R2 values between 0.7 and 1 are the best value for the statistical model [78]. The R2 value recorded (0.7892) from this study fits into the recommended range, lower than what is reported in a similar report [79] but higher than what was noticed (0.698 and 0.6371) in another biogas experiment [80]. The difference in this value can be traced to the variation in the substrate and input variables considered. The higher value of R2 is a sign of good agreement between the predicted and observed data from the experiments. A tolerable accord exists between the Predicted R2 (0.6504) and Adjusted R2 (0.6179) since the difference between them is below 0.2. A lower CV value means higher model reliability, and a low value (22.47) signifies better model reliability. The standard deviation and mean values recorded from the model are 29.05 and 129.26, respectively.

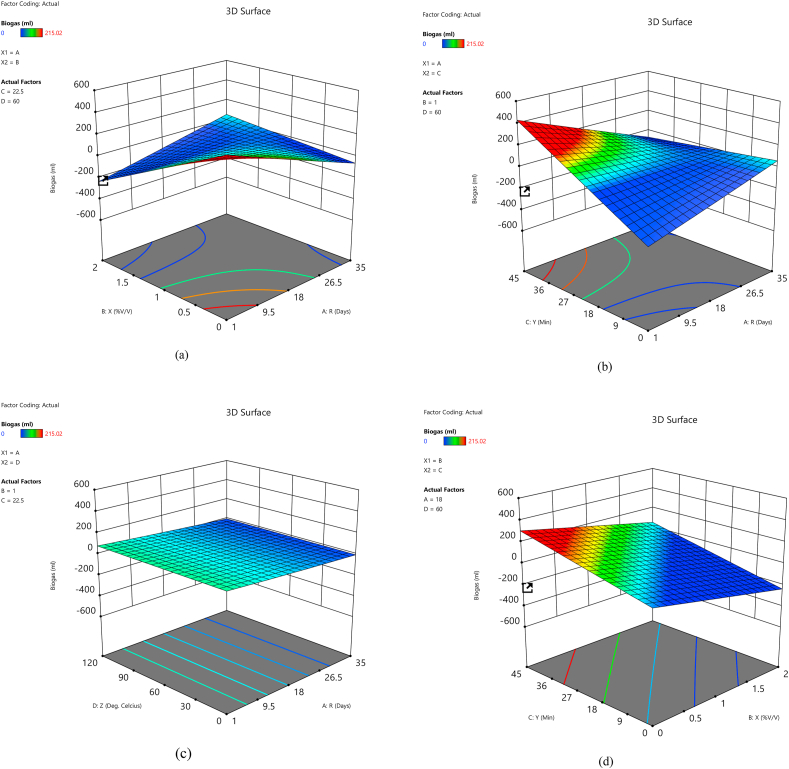

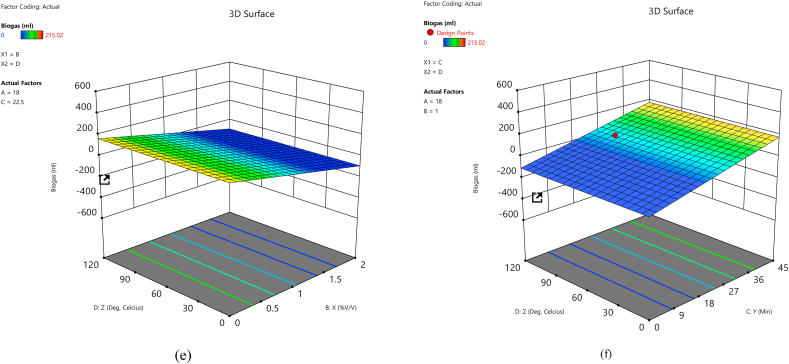

Three-dimensional response surface plots were produced by holding two variables at their central level and varied other experimental ranges. The 3D surface plot was utilized to study the interactive influence of the input variables on biogas yield. The 3D surface plot of the calculated response (biogas yield) of the interaction between the input variables is shown in Fig. 4a–f. Fig. 4a–c indicated that the dependency of biogas yield improved with an increase in the retention time until day 18. After that day, the biogas yield declined as the retention time increased. In the earlier days of biogas production, there was sufficient feedstock that the methanogens fed on to release biogas. Still, as time increases, the lesser feedstock will limit methanogens' activities [81]. Previous research [61] reported that lower concentrations of H2SO4 produce optimum biogas yield because a higher concentration of acid may produce inhibitory compounds that can hinder the activities of methanogens. The same trend was noticed in Fig. 4a, d, and e, which showed the dependency of biogas production on the concentration of acid used during the pretreatment process. The biogas release was improved with a rise in the concentration of acid to 1% v/v, and after that, the biogas produced started to decline with a further increase in acid concentration. Fig. 4b, d, and f show the dependency of biogas yield on the exposure time during pretreatment. From the plots, it can be inferred that there was a biogas increase until the exposure time of 22.50 min, but after this time, the biogas yield started declining. From the dependency of biogas on autoclave temperature in Fig. 4c, e, and f, the biogas yield improved with temperatures of 60 °C. After that, the biogas yields declined with increased autoclave temperatures. The optimum condition for the optimal biogas yield is determined by response surface analysis and is also predicted using an optimization tool, “Design Expert 13.0”. The optimal experimental conditions for Arachis hypogea shells pretreated with H2SO4 acid are retention time (18 days), acid concentration (1% v/v), exposure time (22.5 min), and autoclave temperature (60 °C).

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional response surface plot for biogas yield showing the interactive effects of (a) acid concentration and retention time, (b) exposure time and retention time, (c) autoclave temperature and retention time, (d) exposure time and acid concentration, (e) autoclave temperature and acid concentration, and (f) autoclave temperature and exposure time.

4. Conclusion

Four different conditions of acidic pretreatment were experimented with on Arachis hypogea shells to evaluate their influence on modifying lignocellulose arrangement, enhancing digestion, and improving biogas and methane released. Arachis hypogea shells was noticed to be a more helpful feedstock pretreatment candidate as they showed apparent differences across the different conditions. Acidic pretreatment efficiently altered the recalcitrant characteristics and strong arrangement of lignocellulosic Arachis hypogea shells and enhanced the cumulative biogas and methane released. With low acid concentration, autoclave temperature, and exposure time, pretreatment produced the highest methane (178% increase) yield. Acidic pretreatment with H2SO4 is a possible method to overturn the lignocellulosic arrangement and improve the digestion of Arachis hypogea shells for the future anaerobic digestion industry. The application of RSM to optimize the biogas yield showed an R2 of 0.7892, which implies that the model can be employed to optimize and forecast the process.

Author contribution statement

Kehinde O. Olatunji: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Daniel M. Madyira: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

There is no funding received for this study.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. Material/referenced in article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sewsynker-Sukai Y., Faloye F., Kana G. Artificial neural networks: an efficient tool for modelling and optimization of biofuel production (a mini review) Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2016;31 doi: 10.1080/13102818.2016.1269616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das S., Bhattacharya A., Haldar S., Ganguly A., Gu S., Ting Y.P., Chatterjee P.K. Optimization of enzymatic saccharification of water hyacinth biomass for bio-ethanol: comparison between artificial neural network and response surface methodology. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2015;3:17–28. doi: 10.1016/J.SUSMAT.2015.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarlat N., Dallemand J.F., Fahl F. Biogas: developments and perspectives in europe. Renew. Energy. 2018;129:457–472. doi: 10.1016/J.RENENE.2018.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piechota G. Removal of siloxanes from biogas upgraded to biomethane by cryogenic temperature condensation system. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;308 doi: 10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2021.127404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pongsopon M., Woraruthai T., Anuwan P., Amawatjana T., Tirapanampai C., Prombun P., Kusonmano K., Weeranoppanant N., Chaiyen P., Wongnate T. Anaerobic co-digestion of yard waste, food waste, and pig slurry in a batch experiment: an investigation on methane potential, performance, and microbial community. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2023;21 doi: 10.1016/J.BITEB.2023.101364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pardilhó S., Boaventura R., Almeida M., Maia Dias J. Anaerobic co-digestion of marine macroalgae waste and fruit waste: effect of mixture ratio on biogas production. J. Environ. Manag. 2022;322 doi: 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2022.116142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marousek J. Two-fraction anaerobic fermentation of grass waste. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013;93:2410–2414. doi: 10.1002/JSFA.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bencoova B., Grosos R., Gomory M., Bacova K., Michalkova S. Use of biogas plants on a national and international scale. Acta Montan. Slovaca. 2021;26:139–148. doi: 10.46544/AMS.v26i1.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Y., Gou X., Skare M., Xu Z. Carbon pricing mechanism for the energy industry: a bibliometric study of optimal pricing policies funding information: carbon pricing mechanism for the energy industry: a bibliometric study of optimal pricing policies. Acta Montan. Slovaca. 2022;27:49–69. doi: 10.46544/AMS.v27i1.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mardoyan A., Braun P. Analysis of Czech subsidies for solid biofuels. Int. J. Green Energy. 2015;12:405–408. doi: 10.1080/15435075.2013.841163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogunkunle O., Olatunji K.O., Jo A. 2018. Comparative Analysis of Co-digestion of Cow Dung and Jatropha Cake at Ambient Temperature. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badshah M., Lam D.M., Liu J., Mattiasson B. Use of an Automatic Methane Potential Test System for evaluating the biomethane potential of sugarcane bagasse after different treatments. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;114:262–269. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsapekos P., Kougias P.G., Frison A., Raga R., Angelidaki I. Improving methane production from digested manure biofibers by mechanical and thermal alkaline pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;216:545–552. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2016.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambusiti C., Ficara E., Malpei F., Steyer J.P., Carrere H. Effect of sodium hydroxide pretreatment on physical, chemical characteristics and methane production of five varieties of sorghum. Energy. 2013;55:449–456. doi: 10.1016/J.ENERGY.2013.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olatunji K.O., Ahmed N.A., Ogunkunle O. Optimization of biogas yield from lignocellulosic materials with different pretreatment methods: a review. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2021;14(1):1–34. doi: 10.1186/S13068-021-02012-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catherine C., Twizerimana M. Biogas production from thermochemically pretreated sweet potato root waste. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barua V.B., Kalamdhad A.S. Biogas production from water hyacinth in a novel anaerobic digester: a continuous study. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2019;127:82–89. doi: 10.1016/J.PSEP.2019.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marousek J. Prospects in straw disintegration for biogas production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2013;20:7268–7274. doi: 10.1007/S11356-013-1736-4/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandel A.K., da Silva S.S., Singh O.V. 2011. Detoxification of Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates for Improved Bioethanol Production, Biofuel Production-Recent Developments and Prospects. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan M.U., Usman M., Ashraf M.A., Dutta N., Luo G., Zhang S. A review of recent advancements in pretreatment techniques of lignocellulosic materials for biogas production: opportunities and Limitations. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2022;10 doi: 10.1016/J.CEJA.2022.100263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou S., Zhang Y., Dong Y. Pretreatment for biogas production by anaerobic fermentation of mixed corn stover and cow dung. Energy. 2012;46:644–648. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2012.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bondesson P.M., Galbe M., Zacchi G. Ethanol and biogas production after steam pretreatment of corn stover with or without the addition of sulphuric acid. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2013;6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellera F.M., Gidarakos E. Chemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic agroindustrial waste for methane production. Waste Manag. 2018;71:689–703. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Z., Yang G., Liu X., Yan Z., Yuan Y., Liao Y. Comparison of seven chemical pretreatments of corn straw for improving methane yield by anaerobic digestion. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahunsi S.O., Adesulu-Dahunsi A.T., Osueke C.O., Lawal A.I., Olayanju T.M.A., Ojediran J.O., Izebere J.O. Biogas generation from Sorghum bicolor stalk: effect of pretreatment methods and economic feasibility. Energy Rep. 2019;5:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2019.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faostat, (n.d.). http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize (accessed July 20, 2021).

- 27.Olatunji K.O., Ahmed N.A., Madyira D.M., Adebayo A.O., Ogunkunle O., Adeleke O. Performance evaluation of ANFIS and RSM modeling in predicting biogas and methane yields from Arachis hypogea shells pretreated with size reduction. Renew. Energy. 2022;189:288–303. doi: 10.1016/J.RENENE.2022.02.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Official Methods of Analysis. twenty-first ed. AOAC INTERNATIONAL; 2019. https://www.aoac.org/official-methods-of-analysis-21st-edition-2019/ (n.d.) (accessed October 15, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sathish S., Vivekanandan S. Parametric optimization for floating drum anaerobic bio-digester using response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Alex. Eng. J. 2016;55:3297–3307. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2016.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayakumar V., Govindaradjane S., Senthil Kumar P., Rajamohan N., Rajasimman M. Sustainable removal of cadmium from contaminated water using green alga – optimization, characterization and modeling studies. Environ. Res. 2021;199 doi: 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2021.111364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olatunji K.O., Madyira D.M., Ahmed N.A., Jekayinfa S.O., Ogunkunle O. Waste Management and Research; 2022. Modelling the Effects of Particle Size Pretreatment Method on Biogas Yield of Groundnut Shells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akintunde A.M., Ajala S.O., Betiku E. Optimization of Bauhinia monandra seed oil extraction via artificial neural network and response surface methodology: a potential biofuel candidate. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015;67:387–394. doi: 10.1016/J.INDCROP.2015.01.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Douglas J.W., Montgomery C. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2001. Design and Analysis of Engineering Experiments. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venturin B., Frumi Camargo A., Scapini T., Mulinari J., Bonatto C., Bazoti S., Pereira Siqueira D., Maria Colla L., Alves S.L., Paulo Bender J., Luis Radis Steinmetz R., Kunz A., Fongaro G., Treichel H. Effect of pretreatments on corn stalk chemical properties for biogas production purposes. Bioresour. Technol. 2018;266:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olatunji K.O., Madyira D.M., Ahmed N.A., Ogunkunle O. Influence of alkali pretreatment on morphological structure and methane yield of Arachis hypogea shells. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022:1–12. doi: 10.1007/S13399-022-03271-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atalla R.H., VanderHart D.L. The role of solid state 13C NMR spectroscopy in studies of the nature of native celluloses. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 1999;15:1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0926-2040(99)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.V. organischer Stoffe Substratcharakterisierung . 2016. VEREIN DEUTSCHER INGENIEURE Characterisation of the Substrate, Sampling, Collection of Material Data, Fermentation Tests VDI 4630 VDI-RICHTLINIEN. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Soest P.J., Robertson J.B., Lewis B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/JDS.S0022-0302(91)78551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rincon B., Heaven S., Banks C.J., Zhang Y. Anaerobic digestion of whole-crop winter wheat silage for renewable energy production. Energy Fuel. 2012;26:2357–2364. doi: 10.1021/EF201985X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buswell A.M., Mueller H.F. Mechanism of methane fermentation. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2002;44:550–552. doi: 10.1021/IE50507A033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elbeshbishy E., Nakhla G., Hafez H. Biochemical methane potential (BMP) of food waste and primary sludge: influence of inoculum pre-incubation and inoculum source. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;110:18–25. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ajayi-Banji A.A., Rahman S., Sunoj S., Igathinathane C. Impact of corn stover particle size and C/N ratio on reactor performance in solid-state anaerobic co-digestion with dairy manure. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2020;70:436–454. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2020.1729277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siddhu M.A.H., Li J., Zhang J., Huang Y., Wang W., Chen C., Liu G. Improve the anaerobic biodegradability by copretreatment of thermal alkali and steam explosion of lignocellulosic waste. BioMed Res. Int. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/2786598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jonsson L.J., Martin C. Pretreatment of lignocellulose: formation of inhibitory by-products and strategies for minimizing their effects. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;199:103–112. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khayum N., Rout A., Deepak B.B.V.L., Anbarasu S., Murugan S. Application of fuzzy regression analysis in predicting the performance of the anaerobic reactor Co-digesting spent tea waste with cow manure. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2020;11:5665–5678. doi: 10.1007/s12649-019-00874-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das A.K., Nandi S., Behera A.K. vol. I. 2017. Experimental study of different parameters affecting biogas production from kitchen wastes in floating drum digester and its optimization. (Management & Applied Science (IJLTEMAS) 3 Rd Special Issue on Engineering and Technology). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C., Shao Z., Qiu L., Hao W., Qu Q., Sun G. The solid-state physicochemical properties and biogas production of the anaerobic digestion of corn straw pretreated by microwave irradiation. RSC Adv. 2021;11:3575–3584. doi: 10.1039/D0RA09867A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pereira S.C., Maehara L., Machado C.M.M., Farinas C.S. Physical–chemical–morphological characterization of the whole sugarcane lignocellulosic biomass used for 2G ethanol production by spectroscopy and microscopy techniques. Renew. Energy. 2016;87:607–617. doi: 10.1016/J.RENENE.2015.10.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kristiani A., Abimanyu H., Setiawan A.H., Sudiyarmanto, Aulia F. Effect of pretreatment process by using diluted acid to characteristic of oil palm's frond. Energy Proc. 2013;32:183–189. doi: 10.1016/J.EGYPRO.2013.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarbishei S., Goshadrou A., Hatamipour M.S. Mild sodium hydroxide pretreatment of tobacco product waste to enable efficient bioethanol production by separate hydrolysis and fermentation. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2021;11:2963–2973. doi: 10.1007/S13399-020-00644-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim S., Holtzapple M.T. Effect of structural features on enzyme digestibility of corn stover. Bioresour. Technol. 2006;97:583–591. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2005.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang S., Dai G., Ru B., Zhao Y., Wang X., Xiao G., Luo Z. Influence of torrefaction on the characteristics and pyrolysis behavior of cellulose. Energy. 2017;120:864–871. doi: 10.1016/J.ENERGY.2016.11.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao X., Zhang L., Liu D. Biomass recalcitrance. Part I: the chemical compositions and physical structures affecting the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining. 2012;6:465–482. doi: 10.1002/BBB.1331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moutta R.D.O., Ferreira-Leitao V.S., Bon E.P.D.S. Enzymatic hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse and straw mixtures pretreated with diluted acid. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2014;32:93–100. doi: 10.3109/10242422.2013.873795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li L., Zhou W., Wu H., Yu Y., Liu F., Zhu D. Relationship between crystallinity index and enzymatic hydrolysis performance of celluloses separated from aquatic and terrestrial plant materials. Bioresources. 2014;9:3993–4005. doi: 10.15376/BIORES.9.3.3993-4005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shahid M.K., Kashif A., Rout P.R., Aslam M., Fuwad A., Choi Y., Banu J R., Park J.H., Kumar G. A brief review of anaerobic membrane bioreactors emphasizing recent advancements, fouling issues and future perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;270 doi: 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2020.110909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heredia-Guerrero J.A., Benitez J.J., Dominguez E., Bayer I.S., Cingolani R., Athanassiou A., Heredia A. Infrared and Raman spectroscopic features of plant cuticles: a review. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2014.00305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonen C., Deveci E.U., Akter Onal N. Evaluation of biomass pretreatment to optimize process factors for different organic acids via Box–Behnken RSM method. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021;23:2016–2027. doi: 10.1007/S10163-021-01276-7/TABLES/8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amnuaycheewa P., Hengaroonprasan R., Rattanaporn K., Kirdponpattara S., Cheenkachorn K., Sriariyanun M. Enhancing enzymatic hydrolysis and biogas production from rice straw by pretreatment with organic acids. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016;87:247–254. doi: 10.1016/J.INDCROP.2016.04.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riansa-ngawong W., Suwansaard M., Prasertsan P. Kinetic analysis of xylose production from palm pressed fiber by sulfuric acid. KMUTNB Int. J. Appl. Sci. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.14416/J.IJAST.2014.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taherdanak M., Zilouei H., Karimi K. The influence of dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment on biogas production from wheat plant. Int. J. Green Energy. 2016;13:1129–1134. doi: 10.1080/15435075.2016.1175356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim J.W., Kim K.S., Lee J.S., Park S.M., Cho H.Y., Park J.C., Kim J.S. Two-stage pretreatment of rice straw using aqueous ammonia and dilute acid. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:8992–8999. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song Z., Zhang C. Anaerobic codigestion of pretreated wheat straw with cattle manure and analysis of the microbial community. Bioresour. Technol. 2015;186:128–135. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun C., Liu R., Cao W., Yin R., Mei Y., Zhang L. Impacts of alkaline hydrogen peroxide pretreatment on chemical composition and biochemical methane potential of agricultural crop stalks. Energy Fuel. 2015;29:4966–4975. doi: 10.1021/ACS.ENERGYFUELS.5B00838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai D., Li P., Chen C., Wang Y., Hu S., Cui C., Qin P., Tan T. Effect of chemical pretreatments on corn stalk bagasse as immobilizing carrier of Clostridium acetobutylicum in the performance of a fermentation-pervaporation coupled system. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;220:68–75. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2016.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li P., Cai D., Luo Z., Qin P., Chen C., Wang Y., Zhang C., Wang Z., Tan T. Effect of acid pretreatment on different parts of corn stalk for second generation ethanol production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;206:86–92. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2016.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taherdanak M., Zilouei H. Improving biogas production from wheat plant using alkaline pretreatment. Fuel. 2014;115:714–719. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.07.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Q., Tang L., Zhang J., Mao Z., Jiang L. Optimization of thermal-dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment for enhancement of methane production from cassava residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:3958–3965. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Syaichurrozi I., Villta P., Nabilah N., Rusdi R. Effect of sulfuric acid pretreatment on biogas production from Salvinia molesta. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018;7 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2018.102857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marousek J., Kondo Y., Ueno M., Kawamitsu Y. Commercial-scale utilization of greenhouse residues. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2013;60:253–258. doi: 10.1002/BAB.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marousek J. Study on commercial scale steam explosion of winter Brassica napus STRAW. Int. J. Green Energy. 2013;10:944–951. doi: 10.1080/15435075.2012.732158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zvarikova K., Rowland M., Krulicky T. Smart factory performance, and cognitive automation in cyber-physical system-based manufacturing. J. Self Govern. Manag. Econ. 2021;9:7–20. doi: 10.22381/jsme9420211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olatunji K.O., Madyira D.M., Ahmed N.A., Adeleke O., Ogunkunle O. Modeling the biogas and methane yield from anaerobic digestion of Arachis hypogea shells with combined pretreatment techniques using machine learning approaches. Waste and Biomass Valorization. 2022:1–19. doi: 10.1007/S12649-022-01935-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vochozka M., Horak J., Krulicky T., Pardal P. Predicting future Brent oil price on global markets. Acta Montan. Slovaca. 2020;25:375–392. doi: 10.46544/AMS.v25i3.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vochozka M., Rowland Z., Suler P., Marousek J. The influence of the international price of oil on the value of the EUR/USD exchange rate. J. Compet. 2020;12:167–190. doi: 10.7441/JOC.2020.02.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jimenez J., Guardia-Puebla Y., Romero-Romero O., Cisneros-Ortiz M.E., Guerra G., Morgan-Sagastume J.M., Noyola A. Methanogenic activity optimization using the response surface methodology, during the anaerobic co-digestion of agriculture and industrial wastes. Microbial Community Diversity, Biomass Bioenergy. 2014;71:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yan Z., Song Z., Li D., Yuan Y., Liu X., Zheng T. The effects of initial substrate concentration, C/N ratio, and temperature on solid-state anaerobic digestion from composting rice straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2015;177:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reungsang A., Pattra S., Sittijunda S. Optimization of key factors affecting methane production from acidic effluent coming from the sugarcane juice hydrogen fermentation process. Energies. 2012;5:4746–4757. doi: 10.3390/en5114746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gopal L.C., Govindarajan M., Kavipriya M.R., Mahboob S., Al-Ghanim K.A., Virik P., Ahmed Z., Al-Mulhm N., Senthilkumaran V., Shankar V. Optimization strategies for improved biogas production by recycling of waste through response surface methodology and artificial neural network: sustainable energy perspective research. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021;33 doi: 10.1016/J.JKSUS.2020.101241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abubakar I.K., Ibrahim A. Optimization of biogas production from cow dung using response surface methodology | asian journal of research in biosciences. Asian J. Res. Bio. 2021;3:14–20. https://globalpresshub.com/index.php/AJORIB/article/view/1047 (accessed October 16, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haryanto A., Triyono S., Wicaksono N. Effect of hydraulic retention time on biogas production from cow dung in A semi continuous anaerobic digester. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2018;7:93. doi: 10.14710/ijred.7.2.93-100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. Material/referenced in article.