Abstract

This systematic review synthesizes the findings of quantitative studies examining the relationships between Health Belief Model (HBM) constructs and COVID-19 vaccination intention. We searched PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Scopus using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and identified 109 eligible studies. The overall vaccination intention rate was 68.19%. Perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and cues to action were the three most frequently demonstrated predictors of vaccination intention for both primary series and booster vaccines. For booster doses, the influence of susceptibility slightly increased, but the impact of severity, self-efficacy, and cues to action on vaccination intention declined. The impact of susceptibility increased, but severity’s effect declined sharply from 2020 to 2022. The influence of barriers slightly declined from 2020 to 2021, but it skyrocketed in 2022. Conversely, the role of self-efficacy dipped in 2022. Susceptibility, severity, and barriers were dominant predictors in Saudi Arabia, but self-efficacy and cues to action had weaker effects in the USA. Susceptibility and severity had a lower impact on students, especially in North America, and barriers had a lower impact on health care workers. However, cues to action and self-efficacy had a dominant influence among parents. The most prevalent modifying variables were age, gender, education, income, and occupation. The results show that HBM is useful in predicting vaccine intention.

Keywords: health belief model, HBM, COVID-19, vaccination intention, primary series vaccines, boosters, systematic review

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has affected the world severely. As of 9 March 2023, over 759 million global cases and over 6.8 million deaths have been reported [1]. The virus still poses serious health threats, especially to older adults and those with underlying comorbidities. People’s acceptability and demand for COVID-19 vaccines and their intentions to take the COVID vaccine are slowly fading away, and this trend is even worse in the case of booster doses.

Since vaccination intention is pivotal to the success of mass vaccination campaigns as well as to the attaining of herd immunity, it is essential to understand the health beliefs that influence vaccination intention against COVID-19. Some reviews have been conducted focusing on the factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intention. These reviews analyzed COVID-19 vaccination intentions across genders [2] and healthcare workers [3], and between healthcare workers and the general adult population [4]. Two studies conducted rapid reviews, a simplified approach to systematic reviews [5,6]. Two studies performed scoping reviews to explore broad factors such as demographic, social, and contextual factors that influenced the intention to use COVID-19 vaccines [7,8]. Wang et al. [9] and Chen et al. [10] estimated the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate and identified predictors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. However, these studies did not focus on the health belief model (HBM) and its constructs (i.e., perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers). To date, only one study has systematically reviewed the extant literature on HBM [11], but it focused on vaccine hesitancy. In conclusion, prior systematic reviews have focused on narrow topics and rapid and scoping reviews. As of yet, no systematic review has addressed HBM’s utility in predicting COVID-19 vaccination intention.

Hence, the purpose of the current systematic review was to analyze the research that used the HBM as a theoretical framework for understanding vaccination intention against COVID-19. We reported the prevalence of HBM constructs influencing COVID-19 vaccination intention. These results were further broken down by vaccine type (primary series versus booster doses), data collection year, country, continent, and sample type. In addition, we provided an up-to-date and comprehensive review of the literature by including articles published during 2020–2023, and those studies covering booster/third dose and parents’ or caregivers’ vaccination intention to vaccinate their young children for COVID-19. Finally, we reported the prevalence of HBM modifying variables, including demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, income, marital status) and structural variables (e.g., knowledge about a given disease, prior contact with the disease) that were significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccination intention.

2. Methodology

This systematic review was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [12,13]. The ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews) tool [14] was used to evaluate the quality of included studies and the risk of bias.

2.1. Eligibility

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

We included quantitative studies that used the HBM framework and statistical methods to examine associations between HBM constructs and COVID-19 vaccination intention for both primary series and booster doses. To ensure the quality of scientific investigation, we included only studies published in peer-reviewed journals. Other inclusion criteria were articles published in English between December 2019 and February 2023.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

We excluded (1) studies that reported only vaccination intention against COVID-19 without applying HBM constructs; (2) studies that reported vaccination intention against COVID-19 with HBM constructs but which did not perform a quantitative analysis; (3) qualitative studies, non-peer reviewed studies, and conference proceedings; (4) reviews, comments, case reports, editorials and letters; and (5) grey literature.

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search for published literature was conducted in the selected databases: PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Scopus using various key words such as “health belief model” or “HBM”, “vaccination intention” or “vaccine acceptance”, “COVID-19” or “coronavirus” or “SARS-CoV-2”, “first or second dose” or “primary series”, “booster shot or dose” or “third dose”.

The search was conducted from 1 January 2022 to 28 February 2023. Full length papers published between December 2019 and February 2023 were retrieved for analysis. Initially, the titles and abstracts of all articles identified by the search were screened by two researchers independently in line with the inclusion criteria; any disagreements were resolved by consensus. The titles and abstracts of non-quantitative studies and studies that did not apply the health belief model framework to predict vaccination intention were excluded. Full-text articles were obtained for studies whose titles and abstracts met inclusion criteria. All full-text articles were then evaluated to confirm if they reported necessary statistics of HBM constructs–vaccination intention relationships.

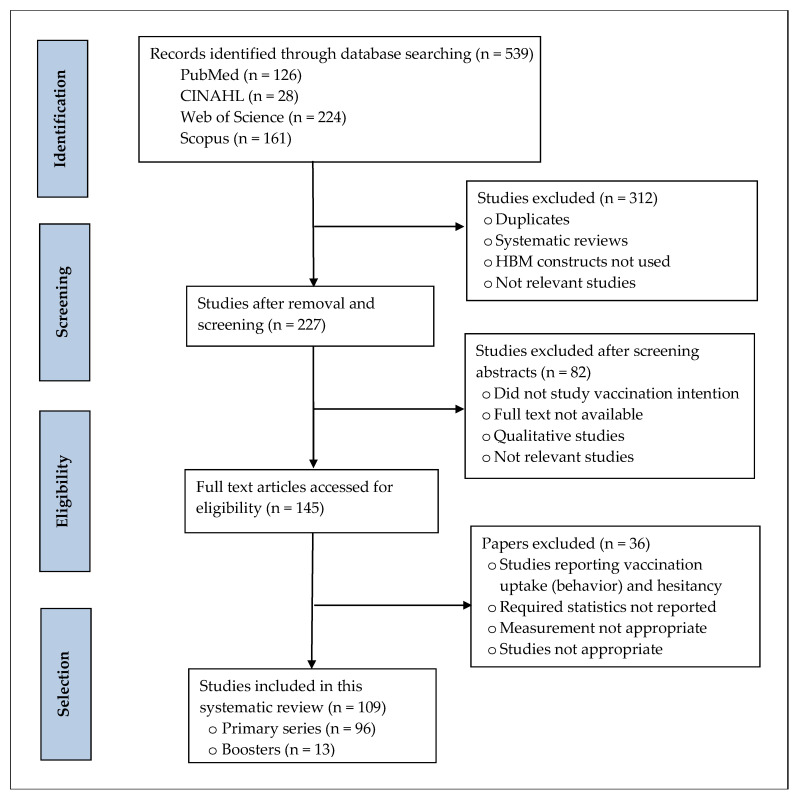

A PRISMA flow diagram was drawn to demonstrate the study selection process, the number of records identified, screened, and excluded, and the reasons for exclusion (see Figure 1). A total of 539 records were retrieved from the four electronic databases. Of them, 312 records were removed for duplicates, systematic reviews, and studies not using HBM constructs. A total of 82 articles were excluded after screening the abstracts as they were irrelevant or did not study vaccination intention or qualitative studies. The remaining 145 full-text papers were further assessed for eligibility. We included 109 studies that met all inclusion criteria after excluding studies not reporting vaccination intention or acceptance, reporting vaccination uptake (behavior) and hesitancy, not reporting required statistics, or not meeting other criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating literature search.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

The same two researchers extracted data from the studies independently. The information extracted consist of the author’s name, data collection year, publication year, study objective, study design, population, sample size, sampling method, measure, statistical analysis technique, the country where the study was conducted, and vaccination rate. We also extracted information on HBM constructs associated with vaccination intention (susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, cues to action, self-efficacy, and modifying variables). The outcome variable was COVID-19 vaccination intention.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27. First, the characteristics of studies included in the review were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Next, we reported average vaccination intention rates by country, data collection year, and population. Finally, the prevalence of HBM constructs significantly related to vaccination intention was presented by data collection year, population, and geographic locations (country and continent).

2.4. Risk of Bias

To ensure the methodological quality as well as to evaluate the level of bias and to assess specific concerns about potential biases in the database search, selection, data extraction, and synthesis, the ROBIS tool was used as per the guidelines of Whiting et al. [14]. The ratings were used to judge the overall risk of bias. The signaling questions were answered as “yes”, “probably yes”, “probably no”, “no”, or “no information”. The subsequent level of concern about bias associated with each domain was then judged as “low”, “high”, or “unclear”. If the answers to all signaling questions for a domain were “yes” or “probably yes”, the level of concern was judged as low. If any signaling question was answered “no” or “probably no”, then bias exists.

The same two researchers independently used the ROBIS tool to evaluate risk of bias and to identify studies to be included in the present investigation. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or a decision made by an expert, a third umpire. Similarly, the selection of databases or digital libraries was also decided with consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

This systematic review included 109 studies comprising 96 primary series vaccines and 13 booster vaccines. Fifty-seven articles were published in 2022, forty-two in 2021, eight in 2023, and three in 2020 (see Table 1). Thirty-three (33%) were published in Vaccines, a peer-reviewed journal, and eight studies appeared in Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. Over half of the studies (58/109) collected data in 2021, thirty in 2020, eight in 2022, and eight in 2020–2021. Fifty-nine studies were conducted in Asia, nineteen in North America, fourteen in Europe, and ten in Africa. These studies represent 21 countries, with twenty-one studies from China and eighteen from the USA.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review.

| Author(s) | Year of Publication | Journal | Country | Vaccine Intention % | Population | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Hasan et al. [15] | 2021 | Frontiers in Public Health | NR* | 75 | General population | 372 |

| Al-Metwali et al. [16] | 2021 | Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice | Iraq | 62 | HCW | 1680 |

| Almalki et al. [17] | 2022 | Frontier in Public Health | Saudi Arabia | 38 | Parents | 4135 |

| Alobaidi [18] | 2021 | Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare | Saudi Arabia | 72 | General population | 1333 |

| Alobaidi and Hashim [19] | 2022 | Vaccines | Saudi Arabia | 71 | HCW | 2059 |

| Alobaidi et al. [20] | 2023 | Vaccines | Saudi Arabia | 78 | Patients | 179 |

| An et al. [21] | 2021 | Health Services Insights | Vietnam | 81 | Patients | 462 |

| Ao et al. [22] | 2022 | Vaccines | Malawi | 61 | General population | 758 |

| Apuke and Tunca [23] | 2022 | Journal of Asian and African Studies | Nigeria | 55 | General population | 385 |

| Arabyat et al. [24] | 2023 | Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy | Jordan | - | General population | 3116 |

| Banik et al. [25] | 2021 | BMC Infectious Diseases | Bangladesh | 66 | General population | 682 |

| Barattucci et al. [26] | 2022 | Vaccines | Italy | 84 | General population | 1095 |

| Berg and Lin [27] | 2021 | Translational Behavioral Medicine | USA | 71 | General population | 350 |

| Berni et al. [28] | 2022 | Vaccines | Morocco | 71 | General population | 3800 |

| Burke et al. [29] | 2021 | Vaccine | Australia, Canada, England, New Zealand, USA | 73 | General population | 4303 |

| Cahapay [30] | 2022 | Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment | Philippine | - | Teachers | 1070 |

| Caple et al. [31] | 2022 | PeerJ | Philippines | 63 | General population | 7193 |

| Chu and Liu [32] | 2021 | Patient Education and Counseling | USA | 80 | General population | 934 |

| Coe et al. [33] | 2022 | Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy | USA | 63 | General population | 1047 |

| Duan et al. [34] | 2022 | Vaccines | China | 80 | Patients | 645 |

| Dziedzic et al. [35] | 2022 | Frontiers in Public Health | Poland | 75 | HCW | 443 |

| Ellithorpe et al. [36] | 2022 | Vaccine | USA | 60 | Parents | 682 |

| Enea et al. [37] | 2022 | Health Communication | Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malaysia, Netherlands, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, UK, USA | 73 | General population | 6697 |

| Getachew et al. [38] | 2022 | Frontier in Public Health | Ethiopia | 36 | HCW | 417 |

| Getachew et al. [39] | 2023 | BMJ Open | Ethiopia | 55 | Patient | 412 |

| Ghazy et al. [40] | 2022 | IJERPH | EMR | 75 | General population | 2327 |

| Goffe et al. [41] | 2021 | HVI | UK | 62 | General population | 1660 |

| Goruntla et al. [42] | 2022 | Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine | India | 89 | General population | 2451 |

| Guidry et al. [43] | 2021 | American Journal of Infection Control | USA | 60 | General population | 788 |

| Guidry et al. [44] | 2022 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | USA | 80 | Evangelicals | 531 |

| Guillon and Kergall [45] | 2021 | Public Health | France | 31 | General population | 1146 |

| Handebo et al. [46] | 2021 | PLOS ONE | Ethiopia | 67 | Teachers | 301 |

| Hawlader et al. [47] | 2022 | International Journal of Infectious Diseases | Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nepal | 68 | General population | 18,201 |

| Hossian et al. [48] | 2022 | PLOS ONE | Pakistan | 73 | Students | 2865 |

| Hu et al. [49] | 2022 | Vaccines | China | 84 | General population | 898 |

| Huang et al. [50] | 2023 | Journal of Environmental and Public Health | China | 92 | General population | 525 |

| Huynh et al. [51] | 2022 | Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine | Vietnam | 76 | HCW | 410 |

| Iacob et al. [52] | 2021 | Frontiers in Psychology | Romania | 45 | General population | 864 |

| Jahanshahi-Amjazi et al. [53] | 2022 | JEHP | Iran | 72 | General population | 2365 |

| Jiang et al. [54] | 2021 | HVI | China | 72 | HCW | 1039 |

| Jin et al. [55] | 2021 | Vaccines | Pakistan | General population | 320 | |

| Kasting et al. [56] | 2022 | JMIR Public Health and Surveillance | USA | 80 | General population | 1643 |

| Khalafalla et al. [57] | 2022 | Vaccines | Saudi Arabia | 84 | General population | 1039 |

| Kabir et al. [58] | 2021 | Vaccines | Bangladesh | 69 | General population | 697 |

| Lai et al. [59] | 2021 | Vaccines | China | 85 | General population | 1145 |

| Le An et al. [60] | 2021 | HVI | Vietnam | 77 | Students | 854 |

| Le et al. [61] | 2022 | BMC Public Health | Vietnam | 58 | HCW | 911 |

| Lee et al. [62] | 2022 | JHCPF | Hong Kong | 29 | General population | 800 |

| Li, J.-B. et al. [63] | 2022 | Vaccine | Hong Kong | - | Parents | 11,141 |

| Li, G. et al. [64] | 2022 | Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology | Thailand | 67 | HCW | 226 |

| Liao et al. [65] | 2022 | Vaccine | Hong Kong | 61 | General population | 4055 |

| Lin et al. [66] | 2020 | PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases | China | 83 | General population | 3541 |

| Lin et al. [5] | 2021 | HVI | China | 78 | Parents | 2026 |

| Liu et al. [67] | 2022 | IJERPH | China | 63 | General population | 3389 |

| Lopez-Cepero et al. [68] | 2021 | HVI | Puerto Rico | 83 | General population | 1911 |

| Lyons et al. [69] | 2023 | Vaccines | Trinidad | 60 | Patients | 272 |

| Mahmud et al. [70] | 2021 | Vaccines | Saudi Arabia | 58 | General population | 1387 |

| Mahmud et al. [71] | 2022 | Vaccines | Jordan | 84 | General population | 2307 |

| Maria et al. [72] | 2022 | Vaccines | Indonesia | 89 | HCW | 1684 |

| Mercadante and Law [73] | 2021 | Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy | USA | 67 | General population | 525 |

| Miyachi et al. [74] | 2022 | Vaccines | Japan | 91 | Students | 1776 |

| Mohammed et al. [75] | 2022 | Vaccine | Iraq, Jordan, UAE, Oman, Yemen | 56 | Parents | 1154 |

| Morar et al. [76] | 2022 | IJERPH | Romania | 51 | General population | 110 |

| Nguyen et al. [77] | 2021 | Risk Management and Healthcare Policy | Vietnam | 78 | Students | 412 |

| Okai and Abekah-Nkrumah [78] | 2022 | PLOS ONE | Ghana | 63 | General population | 362 |

| Okmi et al. [79] | 2022 | Cureus | Saudi Arabia | 73 | General population | 1939 |

| Okuyan et al. [80] | 2021 | International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy | Turkey | 75 | HCW | 961 |

| Otiti-Sengeri et al. [81] | 2022 | Vaccines | Uganda | 98 | HCW | 300 |

| Patwary et al. [82] | 2021 | Vaccines | Bangladesh | 85 | General population | 543 |

| Qin et al. [83] | 2022a | Vaccines | China | 94 | General population | 3119 |

| Qin et al. [84] | 2022b | Frontiers in Public Health | China | 88 | Parents | 1724 |

| Qin et al. [85] | 2022c | Frontiers in Public Health | China | 83 | 60 or older | 3321 |

| Qin et al. [86] | 2023 | HVI | China | 81 | General population | 3224 |

| Quinto et al. [87] | 2021 | Philippine Journal of Health Research and Development | Philippine | 93 | Teachers | 707 |

| Rabin and Durta [88] | 2021 | Psychology, Health & Medicine | USA | 76 | General population | 186 |

| Reindl and Catma [89] | 2022 | Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research | USA | 66 | Parents | 30 |

| Reiter et al. [90] | 2020 | Vaccine | USA | 69 | General population | 2006 |

| Rosental and Shmueli [91] | 2021 | Vaccines | Israel | 82 | Students | 628 |

| Rountree and Prentice [92] | 2022 | Irish Journal of Medical Science | Ireland | 32 | General population | 1995 |

| Seangpraw et al. [93] | 2022 | Frontiers in Medicine | Thailand | General population | 1024 | |

| Seboka et al. [94] | 2021 | Risk Management and Healthcare Policy | Ethiopia | 65 | General population | 1160 |

| Shah et al. [95] | 2022 | Vaccine | Singapore | - | General population | 1009 |

| Shmueli [96] | 2021 | BMC Public Health | Israel | 80 | General population | 398 |

| Shmueli [97] | 2022 | Vaccines | Israel | 65 | General population | 461 |

| Short et al. [98] | 2022 | Families, Systems and Health | USA | 37 | Students | 526 |

| Sieverding et al. [99] | 2023 | Psychology, Health & Medicine | UK and Germany | 88 | General population | 1425 |

| Spinewine et al. [100] | 2021 | Vaccines | Belgium | 58 | General population | 1132 |

| Ştefănuţ et al. [101] | 2021 | Frontiers in Psychology | Romania | 45 | Students | 432 |

| Su et al. [102] | 2022 | Frontiers in Psychology | China | 73 | General population | 557 |

| Suess et al. [103] | 2022 | Tourism Management | USA | 71 | Travelers | 1478 |

| Tran et al. [104] | 2021 | Pharmacy Practice | Russia | 42 | General population | 876 |

| Ung et al. [105] | 2022 | BMC Infectious Diseases | Macao | 62 | General population | 552 |

| Vatcharavongvan et al. [106] | 2023 | Vaccine | Thailand | 90 | Parents | 1056 |

| Wagner et al. [107] | 2022 | Vaccines | USA | 38 | General population | 1012 |

| Walker et al. [108] | 2021 | Vaccines | China | 36 | Students | 330 |

| Wang [109] | 2022 | Health Communication | China | 80 | General population | 460 |

| Wang et al. [110] | 2021 | HVI | China | 64 | Students | 833 |

| Wijesinghe et al. [111] | 2021 | Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health | Sri Lanka | 54 | General population | 895 |

| Wirawan et al. [112] | 2022 | Vaccines | Indonesia | 56 | General population | 2674 |

| Wong et al. [113] | 2020 | HVI | Malaysia | 94 | General population | 1159 |

| Xiao et al. [114] | 2021 | Vaccines | China | 56 | General population | 2528 |

| Yan et al. [115] | 2021 | Vaccines | Hong Kong | 42 | General population | 1255 |

| Yang et al. [116] | 2022 | IJERPH | China | 82 | General population | 621 |

| Youssef et al. [117] | 2022 | PLOS ONE | Lebanon | 58 | HCW | 1800 |

| Yu et al. [118] | 2021 | HVI | China | 72 | HCW | 2254 |

| Zakeri et al. [119] | 2021 | Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research | USA | 62 | Parents | 595 |

| Zampetakis and Melas [120] | 2021 | Appl Psychol Health Well-Being | Greece | 44 | Employees | 1165 |

| Zhang et al. [121] | 2023 | Vaccines | China | 86 | General population | 1472 |

| Zhelyazkova et al. [122] | 2022 | Vaccines | Germany | 84 | HCW | 2555 |

NR* = Country is not reported, but the regions are (North America, the Middle East, Europe, Asia); HCW = Health care workers; IJERPH = International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; HVI = Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics; JHCPF = INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing.

All studies were cross-sectional in design. The studies included in this review consisted of 174,490 respondents with a sample size ranging from 110 to 18,201 (mean = 1601, SD = 2234.20). Sixty-six articles studied general adult populations, fourteen health care workers, nine parents, and nine college students. Other populations included patients, teachers, employees, and travelers. All studies recruited participants aged 18 years and above. The vast majority of the studies (87.16%) used non-random sampling (convenience sampling); the remaining fourteen used random sampling techniques. Except for two studies that conducted experiments, all other studies collected data using the survey method. Forty-nine studies used SPSS to analyze their data, twenty-three used STATA, and seven used R. Most studies (70%) used regression analysis and ten used structural equation modeling.

3.2. Vaccination Intention Rate by Country, Population, and Year

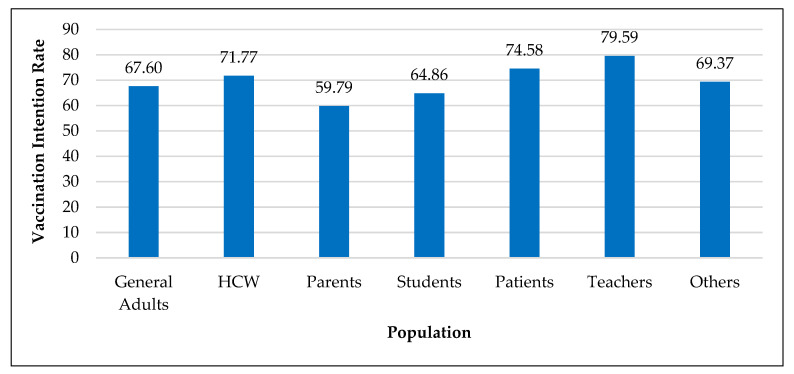

Overall COVID-19 vaccination intention rate was 68.19% (Std. = 17.58), which ranged from 31% to 97.6%. Average vaccination intention percentages for COVID-19 by country were: Malaysia (94.3%), India (89.3%), Puerto Rico (82.7%), Philippines (77.50%), China (76.34%), Israel (75.72%), UK (74.23%), Vietnam (73.48%), Bangladesh (73.17%), Saudi Arabia (66.18%), USA (65.21%), Ethiopia (55.64%), Sri Lanka (54%), and Romania (46.95%). The overall acceptance rate for the COVID-19 vaccine across all studies increased from 63.68% in 2020 to 70% in 2021 and then remained flat in 2022 (69%). As shown in Figure 2, average vaccination intention rate was highest among teachers (80%), followed by patients (75%), health care workers (72%), and general adults (68%). Only 60% of the parents intended to get their children vaccinated against COVID-19.

Figure 2.

Vaccination intention rate by population.

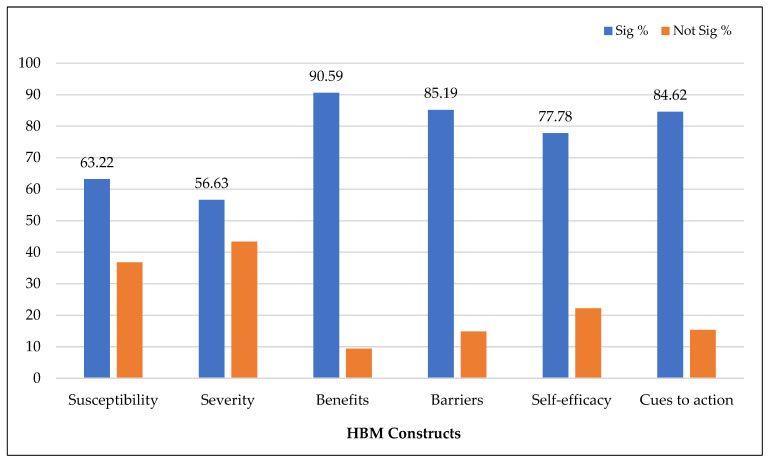

3.3. HBM Constructs Associated with Vaccination Intention

Table 2 presents the studies that reported significant associations between HBM constructs and COVID-19 vaccination intention. As shown in Figure 3, perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccination, the most commonly demonstrated HBM construct, predicted vaccination intention in eighty-seven studies (90.59%) for primary series vaccines. Perceived barriers to accepting the vaccine against COVID-19 were found to be inversely associated with vaccination intention in seventy-seven studies (85.19%). Cues to action were found to be positively associated with vaccination intention in fifty-eight studies (84.61%), perceived susceptibility to develop COVID-19 infection in fifty-five studies (63.22%), perceived severity of COVID-19 infection in fifty-one studies (56.63%), and self-efficacy in twenty-nine studies (77.78%). Surprisingly, thirty-six studies (43.37%) reported insignificant associations between perceived severity and vaccination intention. Similarly, over one-third of the studies (36.78%) that examined perceived susceptibility and over one-fifth of the studies (22.22%) that examined self-efficacy were not significant predictors of vaccination intention.

Table 2.

Health belief model constructs significantly associated with vaccination intention.

Figure 3.

Health belief model constructs predicting primary series vaccination intention.

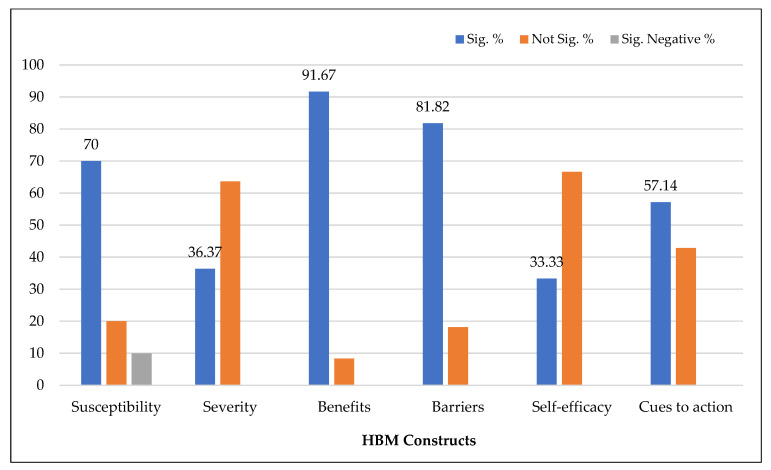

Only thirteen articles used the health belief model to explore the predictors of COVID-19 booster vaccination intention. As presented in Figure 4, perceived benefits, the most commonly demonstrated HBM factor, predicted booster vaccination intention in eleven studies (91.67%). Perceived barriers were negatively related to booster vaccination intention in nine studies (81.82%). Susceptibility was positively associated with booster intention in seven studies (70%). On the contrary, Hu et al. [49] found a negative effect of susceptibility on booster acceptance. Of the eleven studies that examined severity, only four reported perceived severity as a significant determinant of booster intention; however, such an effect was not evident in seven articles (63.64%). In addition, self-efficacy was not significantly associated with booster intention in three out of four studies. Similarly, cues to action did not predict booster intention in three studies (42.86%).

Figure 4.

Health belief model constructs predicting booster vaccination intention.

In conclusion, the influence of perceived severity, self-efficacy, and cues to action on vaccination intention declined for boosters. However, the impact of perceived susceptibility slightly increased for boosters.

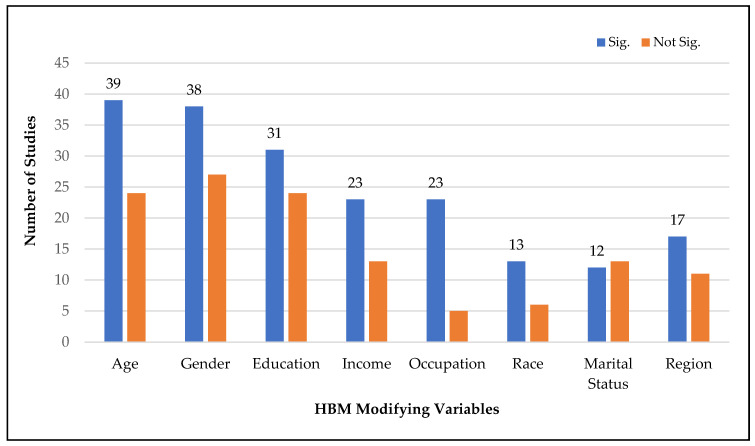

3.4. Modifying HBM Constructs Associated with Vaccination Intention

As shown in Figure 5, the most prevalent modifying variable significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccination intention was age (39 studies), followed by gender (38), education (31), income (23), occupation (23), region (17), race (13 studies), and marital status (12). Other frequently explored modifying variables significantly influencing vaccination intention were religion, nationality, political leaning, history of flu or COVID-19 vaccination, history of COVID infection, knowledge of disease or COVID-19, trust in healthcare system, science or media, sources of information, and health status.

Figure 5.

Major HBM modifying variables associated with vaccination intention.

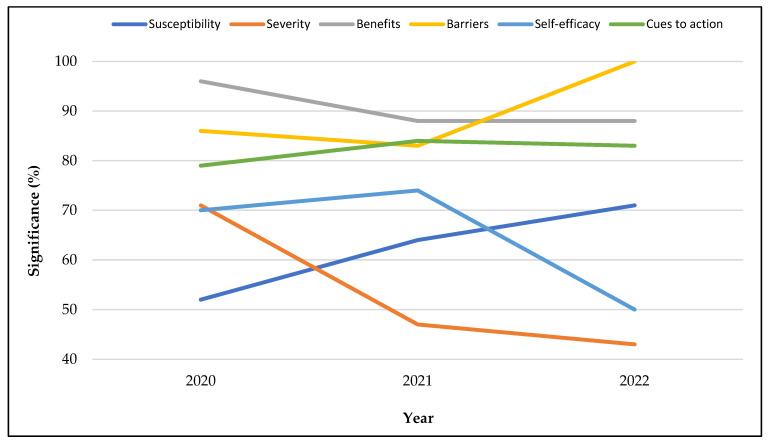

3.5. HBM Constructs Associated with Vaccination Intention by Data Collection Year, Country, Continent, and Sample

3.5.1. Data Collection Year

While the effects of perceived susceptibility on vaccination intention increased significantly from 2020 to 2022, the influence of perceived severity declined sharply (see Figure 6). The significant association of perceived barriers with vaccination intention slightly declined from 2020 to 2021, but it skyrocketed in 2022. Conversely, the effect of self-efficacy dipped in 2022. In addition, the role of perceived benefits declined from 2020 to 2021 but remained flat in 2022. Conversely, the influence of cues to action increased in 2021, but slightly declined in 2022.

Figure 6.

Health belief model constructs associated with vaccination intention by data collection year.

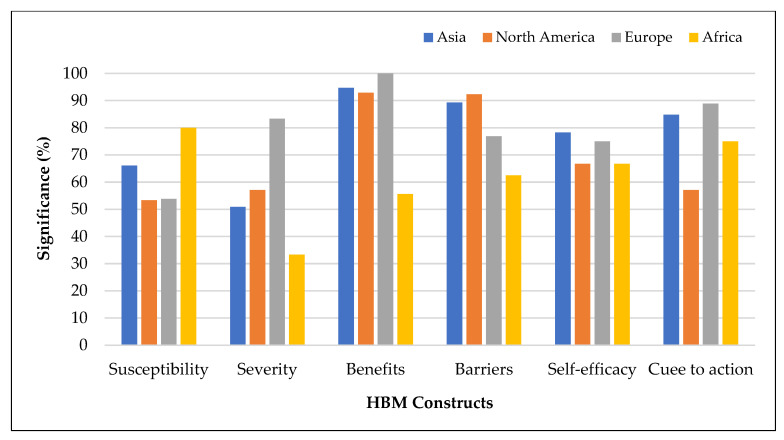

3.5.2. Geographic Location

Figure 7 presents the associations between HBM factors and vaccination intention by continent with five or more studies. All other HBM constructs, except perceived susceptibility, were associated with vaccination intention less frequently in Africa compared to Asia, Europe, and North America. In addition, perceived susceptibility was a less prevalent significant predictor in North America and Europe, compared to Africa and Asia.

Figure 7.

Health belief model constructs associated with vaccination intention by continent with five or more studies.

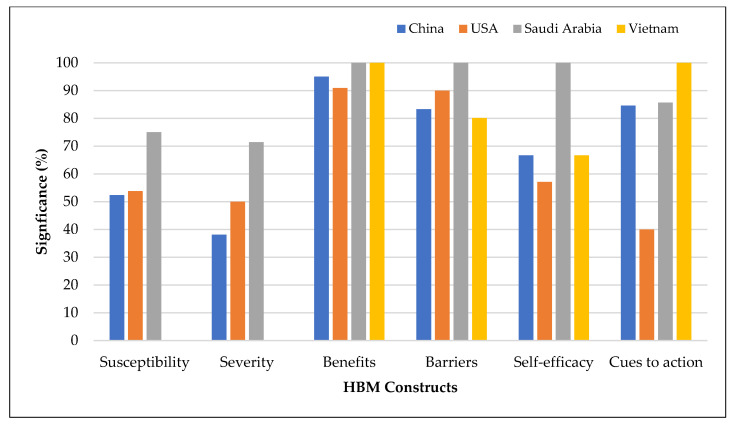

Figure 8 presents the relationships between HBM dimensions and vaccination intention by countries with five or more studies. Perceived susceptibility and perceived severity were more common determinants of vaccination intention in Saudi Arabia than in China and the USA. Perceived severity was the least frequently demonstrated predictor of vaccination intention in China. Self-efficacy and cues to action were less frequently demonstrated predictors in the USA than in China, Saudi Arabia, and Vietnam. Perceived barriers were the more dominant factor influencing vaccination intention in Saudi Arabia than in other countries.

Figure 8.

Health belief model constructs associated with vaccination intention by country with five or more studies.

3.5.3. Study Population

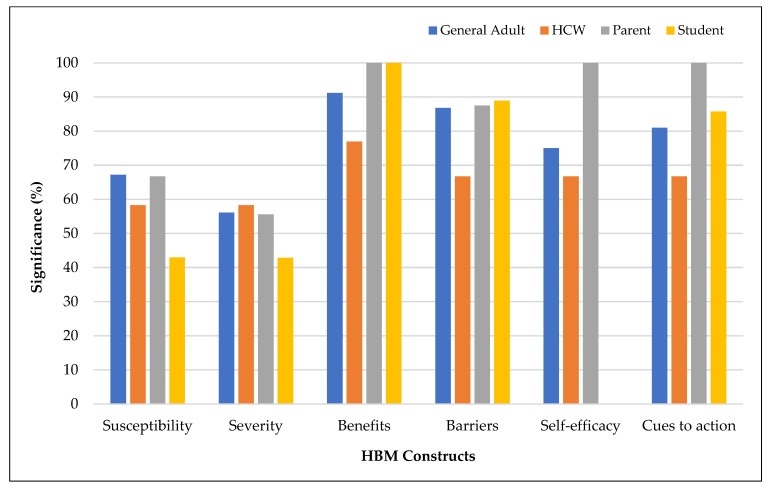

Figure 9 shows the associations between HBM constructs and vaccination intention by the study population. The effects of perceived susceptibility and perceived severity on vaccination intention were lower among students. Perceived barriers were the least frequently demonstrated predictor among health care workers. Cues to action and self-efficacy had a dominant influence among parents.

Figure 9.

Health belief model constructs associated with vaccination intention by study population.

4. Discussion and Implications

The results suggest that perceived benefits of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was the most common HBM construct predicting vaccination intention. Other dominant HBM constructs were perceived barriers to receiving the vaccine and cues to action (i.e., information, people, and events that guided them to be vaccinated). However, perceived susceptibility to developing COVID-19 infection, perceived severity of COVID-19 infection, and perceived self-efficacy of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine were weaker determinants of vaccination intention. The findings of this systematic review provide some support for the health belief model as a useful framework for understanding the facilitators and barriers to COVID-19 vaccination intention. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which suggested similar evidence in the context of influenza vaccination [123,124,125].

Our results indicate that perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and cues to action were the three most frequently demonstrated HBM constructs predicting vaccination intention for both primary series and booster vaccines. Hence, COVID-19 vaccine promotional campaigns should emphasize the benefits of vaccinating against COVID-19. Providing truthful and up-to-date information about the benefits of vaccines can encourage individuals to get vaccinated. Therefore, COVID-19 vaccination communication campaigns may need to progressively shift emphasis from addressing risk perceptions and concerns to stressing the benefits of vaccination for the individual and the community [126].

The results also highlight the importance of identifying the barriers to vaccination (e.g., lack of trust in the government or healthcare system, insufficient knowledge about the benefits of vaccines, misinformation about the coronavirus and vaccines, lack of affordability or shortage of vaccines) and ensuring a course of action to overcome them. In addition, making the vaccine easily accessible (e.g., offering walk-in clinics and mobile vaccination units) can reduce barriers to vaccination and increase uptake. Similarly, offering incentives, such as free or discounted products or services, can motivate individuals to accept vaccines.

The results also show that increasing the vaccination cue to action is crucial. For example, vaccine recommendations or reminders by trusted authorities, government agencies, public health officials, and healthcare experts can effectively persuade people to accept vaccines. In addition, social media and the social influence of celebrities, politicians, friends, family members, or community leaders can play a crucial role in educating, persuading, and influencing people’s vaccination decisions.

This review reveals that the influence of susceptibility on vaccination intention increased from 2020 to 2022 and was higher for booster doses than for primary series vaccines. On the contrary, severity was a less common predictor of vaccination intention for boosters. These results imply that people were increasingly concerned about being infected by COVID-19. Simultaneously, an increasing number of individuals perceived COVID-19 as a less severe disease. One reason is that the virus might have infected several people after receiving primary series vaccines, and they might have experienced mild systems, similar to traditional viruses such as the common cold and influenza. These counterintuitive beliefs pose a significant obstacle to vaccination. Therefore, the government and other concerned parties promoting vaccines should focus on increasing people’s perceptions of the seriousness of COVID infections.

In conclusion, to combat the ongoing pandemic and to increase vaccine uptake against COVID-19, agencies such as the government, policymakers, and the WHO should take account of health beliefs when designing interventions and public health campaigns encouraging vaccination. However, such initiatives should take into account not only the HBM constructs but also geographic (e.g., country, regions), socioeconomic status (e.g., income, education), and other demographic (e.g., age, gender, and occupation) factors that can influence an individual’s vaccination decision.

5. Directions for Future Research

This systematic review synthesized the literature that investigated the relationships between HBM constructs and vaccine intention against COVID-19. However, the findings are mixed. Several studies reported strong correlations between HBM constructs and vaccination intention, but others did not; this is true for both primary series and booster doses. These contradictory results may have been due to several limitations (e.g., research design, study population, data collection approach, measures, analytical approach, and theoretical frameworks) that can be addressed by future studies.

Our results show that the vast majority of studies that utilized theoretical models were based on HBM and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Hence, future research can examine the applicability of other theories such as the Theory of Reasoned Action, Protection Motivation Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Determination Theory, Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills Model, Cognitive Behavioral Theory, Theory of Triadic Influence, Social Network Theory, Diffusion of Innovation Theory, and Social Support Theory.

All the studies included in this systematic review used cross-sectional data. Thus, future research should apply a longitudinal approach because people’s opinions and health beliefs on COVID-19 and vaccines may change over time [127].

Furthermore, this review shows that the vast majority of the studies included in this review used a descriptive/correlational study design and relied on survey methodology. Hence, we recommend causal research and experiments to establish cause-and-effect relationships between the predictors and outcomes. In addition, machine learning techniques and secondary data can be utilized. Finally, qualitative methods such as focus group studies, in-depth interviews, and case studies can provide important insights into vaccine hesitancy and help understand the nuances of vaccination intention across different populations and geographic regions [128].

The studies included in this review used various measures to assess people’s intentions and hesitancy using a slider or a Likert scale. Some of them were dichotomized into vaccine intention and hesitancy. These measures can be misleading and unreliable as they can oversimplify complex attitudes and behaviors related to vaccination against COVID-19. In addition, these measures may not capture the nuances of individuals’ vaccine intentions and hesitancy. Hence, alternative measures (e.g., multiple-item scales that assess different aspects of vaccination attitudes and behaviors) can be developed and used for future research.

A vast majority of studies included in this systematic review used regression analysis, especially logistic regression using dichotomous dependent variables. Thus, we recommend using other statistical analyses (e.g., SEM, linear regression) with a continuous outcome variable.

Our results indicate that the HBM has been primarily applied to study vaccine intentions of the general adult population, parents, students, and health care workers. Future research should focus on specific and under-represented populations such as deprived communities, ethnic and racial minorities, rural and aged populations, and people with multiple chronic conditions. Likewise, more research is needed to explore understudied regions or countries, especially Australia, Oceania, South America, and African countries. Similarly, comparing high-income versus low-income countries, Western versus non-Western countries, and developed versus developing regions/countries may provide additional insights into the conflicting literature.

Finally, it is also essential to consider the cultural and social context in which vaccine intention and hesitancy are assessed. Different cultures and social groups may have unique beliefs, values, and experiences related to COVID-19 and vaccination, and these factors can influence attitudes and behaviors towards vaccination. Therefore, it is crucial to use culturally sensitive and culturally appropriate measures when assessing vaccine intention and hesitancy.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review synthesizes the findings of quantitative studies examining the associations between HBM constructs and vaccination intention against COVID-19. Our results indicate that perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and cues to action are the most common determinants of vaccination intention. However, perceived susceptibility to developing COVID-19 infection, perceived severity of COVID-19 infection, and perceived self-efficacy of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine were weaker predictors of vaccination intention. In addition, the associations between HBM factors and vaccination intention differed across vaccine type, study year, geographic location, and study population. The results show that the health belief model can be helpful for understanding the facilitators and barriers to COVID-19 vaccination intention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, validation, formal analysis, and writing original draft, Y.B.L. and R.K.G.; investigation, R.K.G.; resources, R.K.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.B.L. and R.K.G.; visualization, R.K.G. and Y.B.L.; supervision, Y.B.L.; project administration, R.K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated in this study is available by contacting the first author, Yam B. Limbu, if requested reasonably.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [(accessed on 12 March 2023)]; Available online: https://covid19.who.int.

- 2.Zintel S., Flock C., Arbogast A.L., Forster A., Von Wagner C., Sieverding M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Public Health. 2022:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10389-021-01677-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galanis P., Vraka I., Fragkou D., Bilali A., Kaitelidou D. Intention of healthcare workers to accept COVID-19 vaccination and related factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2021;14:543. doi: 10.4103/1995-7645.332808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Amer R., Maneze D., Everett B., Montayre J., Villarosa A.R., Dwekat E., Salamonson Y. COVID-19 Vaccination Intention in the First Year of the Pandemic: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022;31:62–86. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin Y., Hu Z., Zhao Q., Alias H., Danaee M., Wong L.P. Chinese Parents’ Intentions to Vaccinate Their Children against SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccine Preferences. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:4806–4815. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1999143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y., Liu Y. Multilevel Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid Systematic Review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022;25:101673. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AlShurman B.A., Khan A.F., Mac C., Majeed M., Butt Z.A. What demographic, social, and contextual factors influence the intention to use COVID-19 vaccines: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:9342. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas M., Alzubaidi M.S., Shah U., Abd-Alrazaq A.A., Shah Z. A scoping review to find out worldwide COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its underlying determinants. Vaccines. 2021;9:1243. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Q., Yang L., Jin H., Lin L. Vaccination against COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Acceptability and Its Predictors. Prev. Med. 2021;150:106694. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H., Li X., Gao J., Liu X., Mao Y., Wang R., Zheng P., Xiao Q., Jia Y., Fu H., et al. Health Belief Model Perspective on the Control of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and the Promotion of Vaccination in China: Web-Based Cross-sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021;23:e29329. doi: 10.2196/29329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limbu Y.B., Gautam R.K., Pham L. The Health Belief Model Applied to COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Systematic Review. Vaccines. 2022;10:973. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10060973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Moher D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021;134:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiting P., Savović J., Higgins J.P., Caldwell D.M., Reeves B.C., Shea B., Davies P., Kleijnen J., Churchill R., ROBIS Group ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Hasan A., Khuntia J., Yim D. Does Seeing What Others Do Through Social Media Influence Vaccine Uptake and Help in the Herd Immunity Through Vaccination? A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Front. Public Health. 2021;9:715931. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.715931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Metwali B.Z., Al-Jumaili A.A., Al-Alag Z.A., Sorofman B. Exploring the Acceptance of COVID -19 Vaccine among Healthcare Workers and General Population Using Health Belief Model. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021;27:1112–1122. doi: 10.1111/jep.13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almalki O.S., Alfayez O.M., Al Yami M.S., Asiri Y.A., Almohammed O.A. Parents’ Hesitancy to Vaccinate Their 5–11-Year-Old Children Against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: Predictors From the Health Belief Model. Front. Public Health. 2022;10:842862. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.842862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alobaidi S. Predictors of Intent to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccination Among the Population in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Survey Study. JMDH. 2021;14:1119–1128. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S306654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alobaidi S., Hashim A. Predictors of the Third (Booster) Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine Intention among the Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia: An Online Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines. 2022;10:987. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alobaidi S., Alsolami E., Sherif A., Almahdy M., Elmonier R., Alobaidi W.Y., Akl A. COVID-19 Booster Vaccine Hesitancy among Hemodialysis Patients in Saudi Arabia Using the Health Belief Model: A Multi-Centre Experience. Vaccines. 2023;11:95. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An P.L., Nguyen H.T.N., Dang H.T.B., Huynh Q.N.H., Pham B.D.U., Huynh G. Integrating Health Behavior Theories to Predict Intention to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine. Health Serv. Insights. 2021;14:117863292110601. doi: 10.1177/11786329211060130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ao Q., Egolet R.O., Yin H., Cui F. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccines among Adults in Lilongwe, Malawi: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on the Health Belief Model. Vaccines. 2022;10:760. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apuke O.D., Asude Tunca E. Modelling the Factors That Predict the Intention to Take COVID-19 Vaccine in Nigeria. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2022 doi: 10.1177/00219096211069642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arabyat R.M., Nusair M.B., Al-Azzam S.I., Amawi H.A., El-Hajji F.D. Willingness to Pay for COVID-19 Vaccines: Applying the Health Belief Model. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023;19:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banik R., Islam M.S., Pranta M.U.R., Rahman Q.M., Rahman M., Pardhan S., Driscoll R., Hossain S., Sikder M.T. Understanding the Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intention and Willingness to Pay: Findings from a Population-Based Survey in Bangladesh. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:892. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barattucci M., Pagliaro S., Ballone C., Teresi M., Consoli C., Garofalo A., De Giorgio A., Ramaci T. Trust in Science as a Possible Mediator between Different Antecedents and COVID-19 Booster Vaccination Intention: An Integration of Health Belief Model (HBM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) Vaccines. 2022;10:1099. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10071099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg M.B., Lin L. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions in the United States: The Role of Psychosocial Health Constructs and Demographic Factors. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021;11:1782–1788. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berni I., Menouni A., Filali Zegzouti Y., Kestemont M.-P., Godderis L., El Jaafari S. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Morocco: Applying the Health Belief Model. Vaccines. 2022;10:784. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burke P.F., Masters D., Massey G. Enablers and Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: An International Study of Perceptions and Intentions. Vaccine. 2021;39:5116–5128. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cahapay M.B. To Get or Not to Get: Examining the Intentions of Philippine Teachers to Vaccinate against COVID-19. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2022;32:325–335. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2021.1896409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caple A., Dimaano A., Sagolili M.M., Uy A.A., Aguirre P.M., Alano D.L., Camaya G.S., Ciriaco B.J., Clavo P.J.M., Cuyugan D., et al. Interrogating COVID-19 Vaccine Intent in the Philippines with a Nationwide Open-Access Online Survey. PeerJ. 2022;10:e12887. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu H., Liu S. Integrating Health Behavior Theories to Predict American’s Intention to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021;104:1878–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coe A.B., Elliott M.H., Gatewood S.B.S., Goode J.-V.R., Moczygemba L.R. Perceptions and Predictors of Intention to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022;18:2593–2599. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan L., Wang Y., Dong H., Song C., Zheng J., Li J., Li M., Wang J., Yang J., Xu J. The COVID-19 Vaccination Behavior and Correlates in Diabetic Patients: A Health Belief Model Theory-Based Cross-Sectional Study in China, 2021. Vaccines. 2022;10:659. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dziedzic A., Issa J., Hussain S., Tanasiewicz M., Wojtyczka R., Kubina R., Konwinska M.D., Riad A. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Hesitancy (VBH) of Healthcare Professionals and Students in Poland: Cross-Sectional Survey-Based Study. Front. Public Health. 2022;10:938067. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.938067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellithorpe M.E., Aladé F., Adams R.B., Nowak G.J. Looking Ahead: Caregivers’ COVID-19 Vaccination Intention for Children 5 Years Old and Younger Using the Health Belief Model. Vaccine. 2022;40:1404–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enea V., Eisenbeck N., Carreno D.F., Douglas K.M., Sutton R.M., Agostini M., Bélanger J.J., Gützkow B., Kreienkamp J., Abakoumkin G., et al. Intentions to Be Vaccinated Against COVID-19: The Role of Prosociality and Conspiracy Beliefs across 20 Countries. Health Commun. 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2021.2018179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Getachew T., Lami M., Eyeberu A., Balis B., Debella A., Eshetu B., Degefa M., Mesfin S., Negash A., Bekele H., et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine and Associated Factors among Health Care Workers at Public Hospitals in Eastern Ethiopia Using the Health Belief Model. Front. Public Health. 2022;10:957721. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.957721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Getachew T., Negash A., Degefa M., Lami M., Balis B., Debela A., Gemechu K., Shiferaw K., Nigussie K., Bekele H., et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Associated Factors among Adult Clients at Public Hospitals in Eastern Ethiopia Using the Health Belief Model: Multicentre Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e070551. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghazy R.M., Abdou M.S., Awaidy S., Sallam M., Elbarazi I., Youssef N., Fiidow O.A., Mehdad S., Hussein M.F., Adam M.F., et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Doses Using the Health Belief Model: A Cross-Sectional Study in Low-Middle- and High-Income Countries of the East Mediterranean Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:12136. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goffe L., Antonopoulou V., Meyer C.J., Graham F., Tang M.Y., Lecouturier J., Grimani A., Bambra C., Kelly M.P., Sniehotta F.F. Factors Associated with Vaccine Intention in Adults Living in England Who Either Did Not Want or Had Not yet Decided to Be Vaccinated against COVID-19. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:5242–5254. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.2002084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goruntla N., Chintamani S., Bhanu P., Samyuktha S., Veerabhadrappa K., Bhupalam P., Ramaiah J. Predictors of Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for the COVID-19 Vaccine in the General Public of India: A Health Belief Model Approach. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2021;14:165. doi: 10.4103/1995-7645.312512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guidry J.P.D., Laestadius L.I., Vraga E.K., Miller C.A., Perrin P.B., Burton C.W., Ryan M., Fuemmeler B.F., Carlyle K.E. Willingness to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine with and without Emergency Use Authorization. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2021;49:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guidry J.P.D., Miller C.A., Perrin P.B., Laestadius L.I., Zurlo G., Savage M.W., Stevens M., Fuemmeler B.F., Burton C.W., Gültzow T., et al. Between Healthcare Practitioners and Clergy: Evangelicals and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:11120. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191711120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guillon M., Kergall P. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions and Attitudes in France. Public Health. 2021;198:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Handebo S., Wolde M., Shitu K., Kassie A. Determinant of Intention to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine among School Teachers in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0253499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawlader M.D.H., Rahman M.L., Nazir A., Ara T., Haque M.M.A., Saha S., Barsha S.Y., Hossian M., Matin K.F., Siddiquea S.R., et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in South Asia: A Multi-Country Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022;114:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hossian M., Khan M.A.S., Nazir A., Nabi M.H., Hasan M., Maliha R., Hossain M.A., Rashid M.U., Itrat N., Hawlader M.D.H. Factors Affecting Intention to Take COVID-19 Vaccine among Pakistani University Students. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0262305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu D., Liu Z., Gong L., Kong Y., Liu H., Wei C., Wu X., Zhu Q., Guo Y. Exploring the Willingness of the COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shots in China Using the Health Belief Model: Web-Based Online Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2022;10:1336. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang C., Yan D., Liang S. The Relationship between Information Dissemination Channels, Health Belief, and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Public Health. 2023;2023:6915125. doi: 10.1155/2023/6915125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huynh G., Tran T., Nguyen H.N., Pham L. COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among Healthcare Workers in Vietnam. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2021;14:159. doi: 10.4103/1995-7645.312513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iacob C.I., Ionescu D., Avram E., Cojocaru D. COVID-19 Pandemic Worry and Vaccination Intention: The Mediating Role of the Health Belief Model Components. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:674018. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.674018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jahanshahi-Amjazi R., Rezaeian M., Abdolkarimi M., Nasirzadeh M. Predictors of the Intention to Receive the COVID 19 Vaccine by Iranians 18–70 Year Old: Application of Health Belief Model. J. Edu. Health Promot. 2022;11:175. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_647_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang T., Zhou X., Wang H., Dong S., Wang M., Akezhuoli H., Zhu H. COVID-19 Vaccination Intention and Influencing Factors among Different Occupational Risk Groups: A Cross-Sectional Study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:3433–3440. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1930473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin Q., Raza S.H., Yousaf M., Zaman U., Siang J.M.L.D. Can Communication Strategies Combat COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy with Trade-Off between Public Service Messages and Public Skepticism? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan. Vaccines. 2021;9:757. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kasting M.L., Macy J.T., Grannis S.J., Wiensch A.J., Lavista Ferres J.M., Dixon B.E. Factors Associated With the Intention to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine: Cross-Sectional National Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8:e37203. doi: 10.2196/37203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khalafalla H.E., Tumambeng M.Z., Halawi M.H.A., Masmali E.M.A., Tashari T.B.M., Arishi F.H.A., Shadad R.H.M., Alfaraj S.Z.A., Fathi S.M.A., Mahfouz M.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Prevalence and Predictors among the Students of Jazan University, Saudi Arabia Using the Health Belief Model: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2022;10:289. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kabir R., Mahmud I., Chowdhury M.T.H., Vinnakota D., Jahan S.S., Siddika N., Isha S.N., Nath S.K., Hoque Apu E. COVID-19 Vaccination Intent and Willingness to Pay in Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2021;9:416. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lai X., Zhu H., Wang J., Huang Y., Jing R., Lyu Y., Zhang H., Feng H., Guo J., Fang H. Public Perceptions and Acceptance of COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2021;9:1461. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le An P., Nguyen H.T.N., Nguyen D.D., Vo L.Y., Huynh G. The Intention to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine among the Students of Health Science in Vietnam. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:4823–4828. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1981726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Le C.N., Nguyen U.T.T., Do D.T.H. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among health professions students in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:854. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee L.Y., Chu K., Chan M.H., Wong C.T., Leung H.P., Chan I.C., Ng C.K., Wong R.Y., Pun A.L., Ng Y.H., et al. Living in a Region With a Low Level of COVID-19 Infection: Health Belief Toward COVID-19 Vaccination and Intention to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine in Hong Kong Individuals. INQUIRY. 2022;59:004695802210827. doi: 10.1177/00469580221082787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li J.-B., Lau E.Y.H., Chan D.K.C. Why Do Hong Kong Parents Have Low Intention to Vaccinate Their Children against COVID-19? Testing Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior in a Large-Scale Survey. Vaccine. 2022;40:2772–2780. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li G., Zhong Y., Htet H., Luo Y., Xie X., Wichaidit W. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Associated Factors among Unvaccinated Workers at a Tertiary Hospital in Southern Thailand. Health Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiol. 2022;9:233339282210830. doi: 10.1177/23333928221083057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao Q., Cowling B.J., Xiao J., Yuan J., Dong M., Ni M.Y., Fielding R., Lam W.W.T. Priming with social benefit information of vaccination to increase acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine. 2022;40:1074–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin Y., Hu Z., Zhao Q., Alias H., Danaee M., Wong L.P. Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Demand and Hesitancy: A Nationwide Online Survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14:e0008961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu R., Huang Y.-H.C., Sun J., Lau J., Cai Q. A Shot in the Arm for Vaccination Intention: The Media and the Health Belief Model in Three Chinese Societies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:3705. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.López-Cepero A., Cameron S., Negrón L.E., Colón-López V., Colón-Ramos U., Mattei J., Fernández-Repollet E., Pérez C.M. Uncertainty and Unwillingness to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine in Adults Residing in Puerto Rico: Assessment of Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behaviors. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:3441–3449. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1938921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lyons N., Bhagwandeen B., Edwards J. Factors Affecting COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions among Patients Attending a Large HIV Treatment Clinic in Trinidad Using Constructs of the Health Belief Model. Vaccines. 2022;11:4. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahmud I., Kabir R., Rahman M.A., Alradie-Mohamed A., Vinnakota D., Al-Mohaimeed A. The Health Belief Model Predicts Intention to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine in Saudi Arabia: Results from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines. 2021;9:864. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mahmud I., Al Imam M.H., Vinnakota D., Kheirallah K.A., Jaber M.F., Abalkhail A., Alasqah I., Alslamah T., Kabir R. Vaccination Intention against COVID-19 among the Unvaccinated in Jordan during the Early Phase of the Vaccination Drive: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines. 2022;10:1159. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10071159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maria S., Pelupessy D.C., Koesnoe S., Yunihastuti E., Handayani D.O.T.L., Siddiq T.H., Mulyantini A., Halim A.R.V., Wahyuningsih E.S., Widhani A., et al. COVID-19 Booster Vaccine Intention by Health Care Workers in Jakarta, Indonesia: Using the Extended Model of Health Behavior Theories. Trop. Med. 2022;7:323. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7100323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mercadante A.R., Law A.V. Will they, or Won’t they? Examining patients’ vaccine intention for flu and COVID-19 using the Health Belief Model. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021;17:1596–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miyachi T., Sugano Y., Tanaka S., Hirayama J., Yamamoto F., Nomura K. COVID-19 Vaccine Intention and Knowledge, Literacy, and Health Beliefs among Japanese University Students. Vaccines. 2022;10:893. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10060893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mohammed A.H., Hassan B.A.R., Wayyes A.M., Gadhban A.Q., Blebil A., Alhija S.A., Darwish R.M., Al-Zaabi A.T., Othman G., Jaber A.A.S., et al. Parental Health Beliefs, Intention, and Strategies about COVID-19 Vaccine for Their Children: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from Five Arab Countries in the Middle East. Vaccine. 2022;40:6549–6557. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Morar C., Tiba A., Jovanovic T., Valjarević A., Ripp M., Vujičić M.D., Stankov U., Basarin B., Ratković R., Popović M., et al. Supporting Tourism by Assessing the Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccination for Travel Reasons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:918. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen V.T., Nguyen M.Q., Le N.T., Nguyen T.N.H., Huynh G. Predictors of Intention to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine of Health Science Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. RMHP. 2021;14:4023–4030. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S328665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Okai G.A., Abekah-Nkrumah G. The Level and Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0270768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okmi E.A., Almohammadi E., Alaamri O., Alfawaz R., Alomari N., Saleh M., Alsuwailem S., Moafa N.J. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among the General Adult Population in Saudi Arabia Based on the Health Belief Model: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2022;14:28326. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Okuyan B., Bektay M.Y., Demirci M.Y., Ay P., Sancar M. Factors Associated with Turkish Pharmacists’ Intention to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine: An Observational Study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022;44:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s11096-021-01344-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Otiti-Sengeri J., Andrew O.B., Lusobya R.C., Atukunda I., Nalukenge C., Kalinaki A., Mukisa J., Nakanjako D., Colebunders R. High COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Eye Healthcare Workers in Uganda. Vaccines. 2022;10:609. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10040609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patwary M.M., Bardhan M., Disha A.S., Hasan M., Haque M.Z., Sultana R., Hossain M.R., Browning M.H.E.M., Alam M.A., Sallam M. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among the Adult Population of Bangladesh Using the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Vaccines. 2021;9:1393. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Qin C., Yan W., Du M., Liu Q., Tao L., Liu M., Liu J. Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Dose and Associated Factors among the Elderly in China Based on the Health Belief Model (HBM): A National Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health. 2022;10:986916. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.986916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qin C., Wang R., Tao L., Liu M., Liu J. Acceptance of a Third Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine and Associated Factors in China Based on Health Belief Model: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2022;10:89. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qin C., Wang R., Tao L., Liu M., Liu J. Association Between Risk Perception and Acceptance for a Booster Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine to Children Among Child Caregivers in China. Front. Public Health. 2022;10:834572. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.834572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Qin C., Du M., Wang Y., Liu Q., Yan W., Tao L., Liu M., Liu J. Assessing acceptability of the fourth dose against COVID-19 among Chinese adults: A population-based survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023;19:2186108. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2186108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quinto J.C.D., Balderrama A.N.C., Hocson F.N.Z., Salanguit M.B., Palatino M.C., Gregorio E.R., Jr. Association of knowledge and risk perceptions of Manila City school teachers with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Philipp. J. Health Res. Dev. 2022;25:8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rabin C., Dutra S. Predicting Engagement in Behaviors to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19: The Roles of the Health Belief Model and Political Party Affiliation. Psychol. Health Med. 2022;27:379–388. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1921229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reindl D., Catma S. A Pre-Vaccine Analysis Using the Health Belief Model to Explain Parents’ Willingness to Vaccinate (WTV) Their Children in the United States: Implications for Vaccination Programs. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2022;22:753–761. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2022.2045957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reiter P.L., Pennell M.L., Katz M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38:6500–6507. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosental H., Shmueli L. Integrating Health Behavior Theories to Predict COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: Differences between Medical Students and Nursing Students. Vaccines. 2021;9:783. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rountree C., Prentice G. Segmentation of Intentions towards COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance through Political and Health Behaviour Explanatory Models. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2022;191:2369–2383. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02852-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seangpraw K., Pothisa T., Boonyathee S., Ong-Artborirak P., Tonchoy P., Kantow S., Auttama N., Choowanthanapakorn M. Using the Health Belief Model to Predict Vaccination Intention Among COVID-19 Unvaccinated People in Thai Communities. Front. Med. 2022;9:890503. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.890503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Seboka B.T., Yehualashet D.E., Belay M.M., Kabthymer R.H., Ali H., Hailegebreal S., Demeke A.D., Amede E.S., Tesfa G.A. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccination demand and intent in resource-limited settings: Based on health belief model. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy. 2021;14:2743–2756. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S315043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shah S., Gui H., Chua P.E.Y., Tan J.-Y., Suen L.K., Chan S.W., Pang J. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination Intent in Singapore, Australia and Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2022;40:2949–2959. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shmueli L. Predicting Intention to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine among the General Population Using the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior Model. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:804. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10816-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shmueli L. The Role of Incentives in Deciding to Receive the Available COVID-19 Vaccine in Israel. Vaccines. 2022;10:77. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Short M.B., Marek R.J., Knight C.F., Kusters I.S. Understanding factors associated with intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Fam. Syst. Health. 2022;40:160. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sieverding M., Zintel S., Schmidt L., Arbogast A.L., von Wagner C. Explaining the Intention to Get Vaccinated against COVID-19: General Attitudes towards Vaccination and Predictors from Health Behavior Theories. Psychol. Health Med. 2023;28:161–170. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2022.2058031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spinewine A., Pétein C., Evrard P., Vastrade C., Laurent C., Delaere B., Henrard S. Attitudes towards COVID-19 Vaccination among Hospital Staff—Understanding What Matters to Hesitant People. Vaccines. 2021;9:469. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ştefănuţ A.M., Vintilă M., Tomiţă M., Treglia E., Lungu M.A., Tomassoni R. The Influence of Health Beliefs, of Resources, of Vaccination History, and of Health Anxiety on Intention to Accept COVID-19 Vaccination. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:729803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.729803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Su L., Du J., Du Z. Government Communication, Perceptions of COVID-19, and Vaccination Intention: A Multi-Group Comparison in China. Front. Psychol. 2022;12:783374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Suess C., Maddock J.E., Dogru T., Mody M., Lee S. Using the Health Belief Model to Examine Travelers’ Willingness to Vaccinate and Support for Vaccination Requirements Prior to Travel. Tour. Manag. 2022;88:104405. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tran V.D., Pak T.V., Gribkova E.I., Galkina G.A., Loskutova E.E., Dorofeeva V.V., Dewey R.S., Nguyen K.T., Pham D.T. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in a High Infection-Rate Country: A Cross-Sectional Study in Russia. Pharm. Pract. 2021;19:2276. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2021.1.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ung C.O.L., Hu Y., Hu H., Bian Y. Investigating the Intention to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccination in Macao: Implications for Vaccination Strategies. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022;22:218. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07191-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vatcharavongvan P., Boonyanitchayakul N., Khampachuea P., Sinturong I., Prasert V. Health Belief Model and Parents’ Acceptance of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Sinopharm COVID-19 Vaccine for Children Aged 5–18 Years Old: A National Survey. Vaccine. 2023;41:1480–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wagner A.L., Wileden L., Shanks T.R., Goold S.D., Morenoff J.D., Sheinfeld Gorin S.N. Mediators of Racial Differences in COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Uptake: A Cohort Study in Detroit, MI. Vaccines. 2021;10:36. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Walker A.N., Zhang T., Peng X.-Q., Ge J.-J., Gu H., You H. Vaccine Acceptance and Its Influencing Factors: An Online Cross-Sectional Study among International College Students Studying in China. Vaccines. 2021;9:585. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang X. Putting Emotions in the Health Belief Model: The Role of Hope and Anticipated Guilt on the Chinese’s Intentions to Get COVID-19 Vaccination. Health Commun. 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2078925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang H., Zhou X., Jiang T., Wang X., Lu J., Li J. Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among Overseas and Domestic Chinese University Students: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17:4829–4837. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1989914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wijesinghe M.S.D., Weerasinghe W.M.P.C., Gunawardana I., Perera S.N.S., Karunapema R.P.P. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine in Sri Lanka: Applying the Health Belief Model to an Online Survey. Asia Pac. J. Public Health. 2021;33:598–602. doi: 10.1177/10105395211014975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wirawan G.B.S., Harjana N.P.A., Nugrahani N.W., Januraga P.P. Health Beliefs and Socioeconomic Determinants of COVID-19 Booster Vaccine Acceptance: An Indonesian Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2022;10:724. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wong L.P., Alias H., Wong P.-F., Lee H.Y., AbuBakar S. The Use of the Health Belief Model to Assess Predictors of Intent to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine and Willingness to Pay. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16:2204–2214. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Xiao Q., Liu X., Wang R., Mao Y., Chen H., Li X., Liu X., Dai J., Gao J., Fu H., et al. Predictors of Willingness to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine after Emergency Use Authorization: The Role of Coping Appraisal. Vaccines. 2021;9:967. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yan E., Lai D.W.L., Lee V.W.P. Predictors of Intention to Vaccinate against COVID-19 in the General Public in Hong Kong: Findings from a Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines. 2021;9:696. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yang X., Wei L., Liu Z. Promoting COVID-19 Vaccination Using the Health Belief Model: Does Information Acquisition from Divergent Sources Make a Difference? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:3887. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19073887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Youssef D., Abou-Abbas L., Berry A., Youssef J., Hassan H. Determinants of acceptance of Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) vaccine among Lebanese health care workers using health belief model. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0264128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yu Y., Ling R.H.Y., Ip T.K.M., Luo S., Lau J.T.F. Factors of COVID-19 Vaccination among Hong Kong Chinese Men Who Have Sex with Men during Months 5–8 since the Vaccine Rollout—General Factors and Factors Specific to This Population. Vaccines. 2022;10:1763. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10101763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zakeri M., Li J., Sadeghi S.D., Essien E.J., Sansgiry S.S. Strategies to Decrease COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy for Children. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2021;12:539–544. doi: 10.1093/jphsr/rmab060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zampetakis L.A., Melas C. The Health Belief Model Predicts Vaccination Intentions against COVID-19: A Survey Experiment Approach. Appl. Psychol. Health Well. 2021;13:469–484. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang R., Yan J., Jia H., Luo X., Liu Q., Lin J. Policy Endorsement and Booster Shot: Exploring Politicized Determinants for Acceptance of a Third Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine in China. Vaccines. 2023;11:421. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11020421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhelyazkova A., Kim S., Klein M., Prueckner S., Horster S., Kressirer P., Choukér A., Coenen M., Adorjan K. COVID-19 Vaccination Intent, Barriers and Facilitators in Healthcare Workers: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Study on 2500 Employees at LMU University Hospital in Munich, Germany. Vaccines. 2022;10:1231. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Brewer N.T., Chapman G.B., Gibbons F.X., Gerrard M., McCaul K.D., Weinstein N. D Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26:136–145. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tsutsui Y., Benzion U., Shahrabani S. Economic and behavioral factors in an individual’s decision to take the influenza vaccination in Japan. J. Socio Econ. 2012;4:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2012.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]