Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease characterized by progressive skin fibrosis. It has 2 main clinical subtypes—diffuse cutaneous scleroderma and limited cutaneous scleroderma. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is defined as presence of elevated portal vein pressures without cirrhosis. It is often a manifestation of an underlying systemic disease. On histopathology, NCPH may be found to be secondary to multiple abnormalities such as nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) and obliterative portal venopathy. There have been reports of NCPH in patients with both subtypes of SSc secondary to NRH. However, simultaneous presence of obliterative portal venopathy has not been reported. We present a case of NCPH due to NRH and obliterative portal venopathy as a presenting sign of limited cutaneous scleroderma. The patient was initially found to have pancytopenia and splenomegaly and was erroneously labeled as cirrhosis. She underwent workup to rule out leukemia, which was negative. She was referred to our clinic and diagnosed with NCPH. Due to pancytopenia, she could not be started on immunosuppressive therapy for her SSc. Our case describes the presence of these unique pathological findings in the liver and highlights the importance of an aggressive search for an underlying condition in all patients diagnosed with NCPH.

Keywords: idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, systemic sclerosis, elastography, Raynaud phenomenon

Introduction

Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is defined as a syndrome characterized by elevated portal pressures in the absence of cirrhosis. 1 It is a complication of systemic, often extrahepatic, diseases.1,2 Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare systemic autoimmune disease characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin. 3 It is a heterogeneous disease with 2 major clinical subtypes—diffuse cutaneous scleroderma (associated with positive anti-Scl-70 antibodies, skin involvement extending proximally to the upper arms, thighs, and/or trunk, with more frequent renal, cardiac, and lung involvement) and limited cutaneous scleroderma (associated with positive anticentromere antibodies, skin sclerosis mostly involving the digits and occasionally the neck and face, higher frequency of pulmonary hypertension, and involvement of gastrointestinal tract). 4 Previous reports have suggested that SSc may lead to development of nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) in the liver, which is a well-known cause of NCPH. 2 Most patients have an established diagnosis of SSc prior to presentation with NRH. 5 Here, we present a case of NCPH secondary to NRH and obliterative portal venopathy as a presenting sign of limited cutaneous scleroderma.

Case

A 37-year-old Hispanic female was referred to our clinic for evaluation of cryptogenic cirrhosis. She had a history of multiple episodes of melena and hematemesis, requiring several esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD) and blood transfusions for the past 2 years. During prior EGDs, she was noted to have esophageal varices that were banded. Her hemoglobin (Hgb) had dropped to as low as 5.7 g/dL, requiring blood transfusions. Iron studies were suggestive of iron deficiency and she was started on iron supplementation. Ultrasonography of the liver as well as a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed a coarsened liver and splenomegaly, with a spleen size of about 19 cm. Laboratory studies showed normal liver enzymes but pancytopenia. She underwent extensive workup to rule out leukemia, which was negative. She was diagnosed with cirrhosis of unknown etiology and referred to our clinic for further care. On presentation, the patient complained of multiple patchy areas of hyperpigmentation on the bilateral legs for the past 5 years, with pruritus worse at night. She had applied topical moisturizers without any significant relief. She also complained of blue discoloration of her fingers and toes on exposure to cold. Her review of systems was otherwise unremarkable. She had been healthy most of her life, denied drinking alcohol, cigarette smoking, use of illicit drugs, or high-risk sexual behavior. Past medical history was otherwise unremarkable with no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, clotting disorders, or miscarriages. The patient had not undergone any surgeries in the past and family history was noncontributory. Apart from omeprazole 20 mg twice a day, iron tablets, and topical moisturizers, she did not take any medications or herbal supplements.

Vital signs were normal except for bradycardia with a heart rate of 55 beats per minute. Her body mass index was 29.1 kg/m2. Physical examination was significant for multiple telangiectasias on the mucosal aspect of her lower lip, tightening of the skin on the bilateral upper extremities distal to the elbow (most significant in hands and fingers) and hyperpigmented thickened plaques on lower left abdomen and both legs (Figure 1). The patient underwent an extensive workup to delineate the etiology of her symptoms. Laboratory results showed pancytopenia with positive anticentromere antibodies as shown in Table 1. The skin biopsy from the abdominal plaque revealed a chronic inflammatory infiltrate with sclerotic dermal collagen and dermal mucin. The CT scan of the chest showed ground glass opacities of the bilateral lower lobes. Vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) showed transient elastography of 9.3 kPa with interquartile range of 19% and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) of 190. Ultrasonography of the liver showed normal liver size, smooth liver surface, but diffuse heterogeneous and coarse echotexture, suggestive of cirrhosis. Shear-wave elastography (SWE) was 1.55 m/s (equivalent to echo time [TE] of about 7.2 kPa). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen revealed splenomegaly, recanalized paraumbilical vein, gastroesophageal varices, and minimal ascites but no liver nodularity or mass. The patient underwent transjugular liver biopsy that showed hepatic venous pressure gradient of 11 mm Hg. Pathology identified obliterative portal venopathy and NRH with no inflammation and minimal perisinusoidal fibrosis (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Physical examination findings: (A) telangiectasias on mucosal aspect of lower lip; (B) sclerotic hyperpigmented plaque on the abdomen; (C) edematous swelling of hands; and (D) multiple sclerotic plaques on the bilateral lower extremities.

Table 1.

Laboratory Values.

| Parameter | Result | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count (×103/µL) | 2.31 | 3.98-10.04 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.3 | 11.2-15.7 |

| Platelet count (×103/µL) | 71 | 173-369 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 | 3.5-5.2 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.59 | 0.55-1.02 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 86 | 40-150 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) | 23 | 0-55 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) | 28 | 5-34 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 | 0.2-1.2 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 | <0.5 |

| Serum gamma glutamyl transferase (U/L) | 30 | 9-36 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.14 | ≤1.1 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 1.8 | 0.9-8.8 |

| Iron (µg/dL) | 12 | 50-170 |

| Transferrin (mg/dL) | 335 | 180-382 |

| Iron saturation (%) | 3 | 20-50 |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | 7 | 10-120 |

| Antinuclear antibody (U) | 10.4 | ≤1 |

| Rheumatoid factor (IU/mL) | 24 | <13 |

| Anti-Ro/SSA antibody (U) | >8.0 | ≤1 |

| Anti-centromere antibody (U) | >8.0 | ≤1 |

| Anti-mitochondrial antibody (U) | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Anti-smooth muscle antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody (U) | <5.0 | ≤20.0 |

| Anti-cardiolipin antibody, IgG (U) | <15.0 | <9.4 |

| Anti-cardiolipin antibody, IgM (U) | <15.0 | 11.1 |

| Anti-dsDNA antibody (IU/mL) | 16.5 | <30.0 |

| Anti-SS-B/La antibody (U) | <0.2 | <1.0 |

| Anti-ribonucleoprotein antibody | 0.2 | <1.0 |

| Anti-Scl-70 antibody | <0.2 | <1.0 |

| Anti-Jo1 antibody | <0.2 | <1.0 |

| Tissue transglutaminase antibody, IgA (U/mL) | <1.2 | <4.0 |

| Anti-beta-2-glycoprotein antibody, IgG (U/mL) | <9.4 | <15.0 |

Abbreviations: U, units; IU, international units; dL, deciliter; mg, milligram; ng, nanogram; µg, microgram; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

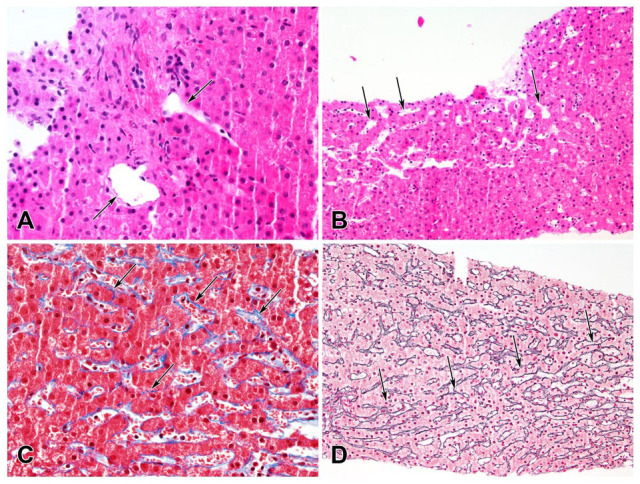

Figure 2.

Changes of obliterative portal venopathy and nodular regenerative hyperplasia. (A) Portal area with small portal veins displaced out of the portal area (H&E, 400×). (B) Sinusoidal dilation (H&E, 200×). (C) Delicate perisinusoidal fibrosis (Masson trichrome, 400×). (D) Vague nodularity with zone of narrowed liver cell plates (arrows; Reticulin, 200×).

Abbreviation: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Based on her clinical presentation and autoantibody profile, the patient was diagnosed with limited cutaneous scleroderma complicated by NRH and obliterative portal venopathy leading to NCPH. She was started on carvedilol and iron supplements. Due to her pancytopenia, she could not be started on immunosuppressive therapy. After 1 year of follow-up, she remained stable with no further episodes of variceal bleeding but continued to have pancytopenia. She is being managed conservatively with follow-up every 6 months.

Discussion

There have been multiple reports of NCPH and NRH in patients with SSc, with 1 study reporting that, out of 26 patients with NRH, about 55% had diffuse and 36% had limited SSc.5-9 Affected patients typically present with a history of SSc along with signs of portal hypertension, such as ascites or variceal bleeding, and normal liver enzymes. A majority of these patients have positive anti-centromere antibodies, suggestive of limited scleroderma. Management includes treatment of SSc with immunosuppressive medications, EGD for screening or treatment of varices, paracentesis and/or diuretics for ascites, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in refractory circumstances.

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia and obliterative portal venopathy are 2 common histopathological patterns seen in liver biopsies in patients with NCPH. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is believed to be due to an imbalance between arterial and portal venous blood flow, leading to nodular areas of hepatic regeneration. 10 In obliterative portal venopathy (also known as hepatoportal sclerosis), which may be associated with NRH, the portal veins are abnormally small or missing. 11 In our case, the liver biopsy showed both NRH and obliterative portal venopathy with minimal fibrosis.

As part of the workup, the patient underwent both VCTE and SWE measurement. It is interesting to note that both VCTE and SWE were elevated but not suggestive of cirrhosis. There are no clear guidelines regarding VCTE and SWE cutoffs for patients with NCPH. One study assessing the utility of VCTE in NCPH patients found that up to 50% patients with NRH and 31% patients with portal venous thrombosis had liver stiffness measurement >10 kPa. 12 These findings suggest that even patients with NCPH can have significantly elevated transient elastography. In contrast, in another recent study, patients with portosystemic vascular disease (PSVD), or idiopathic NCPH, were found to have lower VCTE as compared with those with cirrhosis, although some patients did not have clinically significant portal hypertension. 13 The study demonstrated the utility of VCTE in distinguishing PSVD patients from those with cirrhosis. Shear-wave elastography has similar mechanism and performance as VCTE and therefore can be beneficial in a similar manner. 14 Overall, the exact cutoffs for VCTE and SWE in patients with NCPH are debatable. Regardless, these techniques can aid in earlier diagnosis of NCPH and possibly any underlying condition, which is essential to prevent complications.

In our case, the patient’s skin findings were not brought to attention until she was suspected to have NCPH, when another underlying systemic disease was sought. Due to significant portal hypertension and splenomegaly, the patient had developed pancytopenia, and immunosuppressive therapy could not be initiated. In addition to reporting simultaneous presence of NRH and obliterative portal venopathy, our case highlights the importance of early diagnosis in these patients as delayed diagnosis can lead to worsening portal hypertension, splenomegaly, and pancytopenia, precluding the use of immunosuppressive therapy, which may lead to disease progression and worse outcomes. Diagnosis or suspicion of NCPH should prompt an aggressive search for another underlying condition because NCPH is often a manifestation of another systemic illness. Vibration-controlled transient elastography and SWE can help distinguish cirrhosis from NCPH although a liver biopsy is needed for definitive diagnosis.

Future research in elucidating etiopathogenesis, improving diagnosis, and management of patients with NCPH can help improve their outcomes. Noninvasive methods, such as VCTE and SWE, can be useful in diagnosis and decision-making although additional studies are needed to validate these techniques in this patient population.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: A.A.H. and T.H. contributed significantly to study concept and design; A.A.H., C.R., E.C., and D.K. contributed significantly to data acquisition; data analysis and interpretation; All authors contributed to drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. T.H. and S.H. provided study supervision.

Article Guarantor: Asif Ali Hitawala

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Ethical Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Consent was obtained from the patient for publication as part of consent for the study “Evaluation of Patients With Liver Disease”, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00001971. Hence, written informed consent was obtained from the patient for their anonymized information to be published in this article

ORCID iD: Asif Ali Hitawala  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2888-0172

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2888-0172

References

- 1.Sarin SK, Kumar A.Noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2006;10:627-651. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2006.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semela D.Systemic disease associated with noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2015;6(4):103-106. doi: 10.1002/cld.505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jerjen R, Nikpour M, Krieg T, Denton CP, Saracino AM.Systemic sclerosis in adults. Part I: clinical features and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(5):937-954. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denton CP, Khanna D.Systemic sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;390: 1685-1699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30933-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graf L, Dobrota R, Jordan S, Wildi LM, Distler O, Maurer B.Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver: a rare vascular complication in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(1): 103-106. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colaci M, Aprile ML, Sambataro D, et al. Systemic sclerosis and idiopathic portal hypertension: report of a case and review of the literature. Life. 2022;12:1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain P, Patel S, Simpson HN, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver in rheumatic disease: cases and review of the literature. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9: 23247096211044617. doi: 10.1177/23247096211044617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaburaki J, Kuramochi S, Fujii T, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15(6):613-616. doi: 10.1007/bf02238554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto A, Matsuda H, Hiramatsu K, et al. A case of idiopathic portal hypertension accompanying multiple hepatic nodular regenerative hyperplasia in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021;14(3):820-826. doi: 10.1007/s12328-021-01348-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartleb M, Gutkowski K, Milkiewicz P.Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: evolving concepts on underdiagnosed cause of portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1400-1409. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i11.1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleiner DE.Noncirrhotic portal hypertension: pathology and nomenclature. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2015;5(5):123-126. doi: 10.1002/cld.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vuppalanchi R, Mathur K, Pyko M, Samala N, Chalasani N.Liver stiffness measurements in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension—the devil is in the details. Hepatology. 2018;68(6):2438-2440. doi: 10.1002/hep.30167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkrief L, Lazareth M, Chevret S, et al. Liver stiffness by transient elastography to detect porto-sinusoidal vascular liver disease with portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2021;74(1):364-378. doi: 10.1002/hep.31688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osman AM, El Shimy A, Abd El, Aziz MM.2D shear wave elastography (SWE) performance versus vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE/fibroscan) in the assessment of liver stiffness in chronic hepatitis. Insights Imaging. 2020; 11:38. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-0839-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]