Abstract

The antifungal activity of the drug micafungin, a cyclic lipopeptide that interacts with membrane proteins, may involve inhibition of fungal mitochondria. In humans, mitochondria are spared by the inability of micafungin to cross the cytoplasmic membrane. Using isolated mitochondria, we find that micafungin initiates the uptake of salts, causing rapid swelling and rupture of mitochondria with release of cytochrome c. The inner membrane anion channel (IMAC) is altered by micafungin to transfer both cations and anions. We propose that binding of anionic micafungin to IMAC attracts cations into the ion pore for the rapid transfer of ion pairs.

Keywords: Inner mitochondrial anion channel, mitochondrial transport, mitochondrial respiratory chain complex, ion channel, anion transport, micafungin, cyclic lipopeptides

1. INTRODUCTION

Micafungin and caspofungin are semi-synthetic cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs) of the echinocandin type. As antifungals, all of the echinocandins bind to and inhibit, with micromolar affinity, a fungal glucan synthase that is anchored in the fungal cell cytoplasmic membrane and is vital for synthesis of the fungal cell wall (Garcia-Effron et al., 2009; Kurtz and Douglas, 1997). Micafungin and caspofungin are primarily used to treat hospital-acquired Candida and Aspergillus infections (Kofla and Ruhnke, 2011; Morris and Villmann, 2006). Several reports show that inhibition of mitochondrial function in fungal cells may be part of the antifungal effect of micafungin and caspofungin secondary to their inhibition of glucan synthase (Chamilos et al., 2006; Dagley et al., 2011; Garcia-Rubio et al., 2021; Shingu-Vazquez and Traven, 2011; Shirazi and Kontoyiannis, 2015; Shirazi et al., 2015). In 2016, we published a study showing that micafungin and caspofungin strongly altered the activities of two proton-pumping electron transfer complexes in mitochondria when the drugs were applied at low micromolar concentrations to isolated rat mitochondria (Shirey et al., 2016). When applied to isolated mitochondria, both micafungin and caspofungin strongly inhibited heart and liver complex III (IC50 = 3-10 μM), likely by preventing the up and down motion of its Fe-S subunit (Shirey et al., 2016). Of particular interest was that caspofungin, which has cationic substituents in its headgroup, strongly inhibited the activity of CIV (IC50 = 10-17 μM), while anionic micafungin stimulated complex IV activity nearly three-fold (EC50 = 12-16 μM). We have proposed that caspofungin inhibits the exit of pumped protons while micafungin enhances proton uptake (Shirey et al., 2016). It should be noted that in animals and humans, administration of micafungin and caspofungin does not lead to mitochondrial dysfunction (Koch et al., 2015; Shirey et al., 2016) perhaps because these CLPs only leak across the cytoplasmic membrane of fungal cells, and then only after the tough fungal cell wall has been compromised (Hasim and Coleman, 2019).

In this study we show that micafungin, but not caspofungin, has an additional and dramatic effect on the inner membrane anion channel (IMAC), the principal anion conducting pore of the inner membrane of mammalian mitochondria (Garlid and Beavis, 1986; Selwyn et al., 1979). We describe how this micafungin-induced alteration in mitochondria may contribute to the reported ability of micafungin to trigger apoptosis in Candida (Shirazi and Kontoyiannis, 2015). The study also extends our previous work (described above) defining the capabilities of CLPs to modify the activities of membrane proteins. (Background on IMAC is presented below.)

The study uses isolated mitochondria because micafungin and caspofungin do not normally cross the cytoplasmic membrane to access mitochondria, nor do salts and other experimental reagents used to control the osmotic and ionic environment of the mitochondria during experiments. Using isolated mitochondria also allows us to use the well-validated, simple technique of visible light scattering to obtain the kinetics and extent of mitochondrial swelling (Beavis et al., 1985) and the relative rates of ion transfer across the inner mitochondrial membrane (Garlid and Beavis, 1985).

Echinocandin CLPs and their interactions with membranes and membrane proteins.

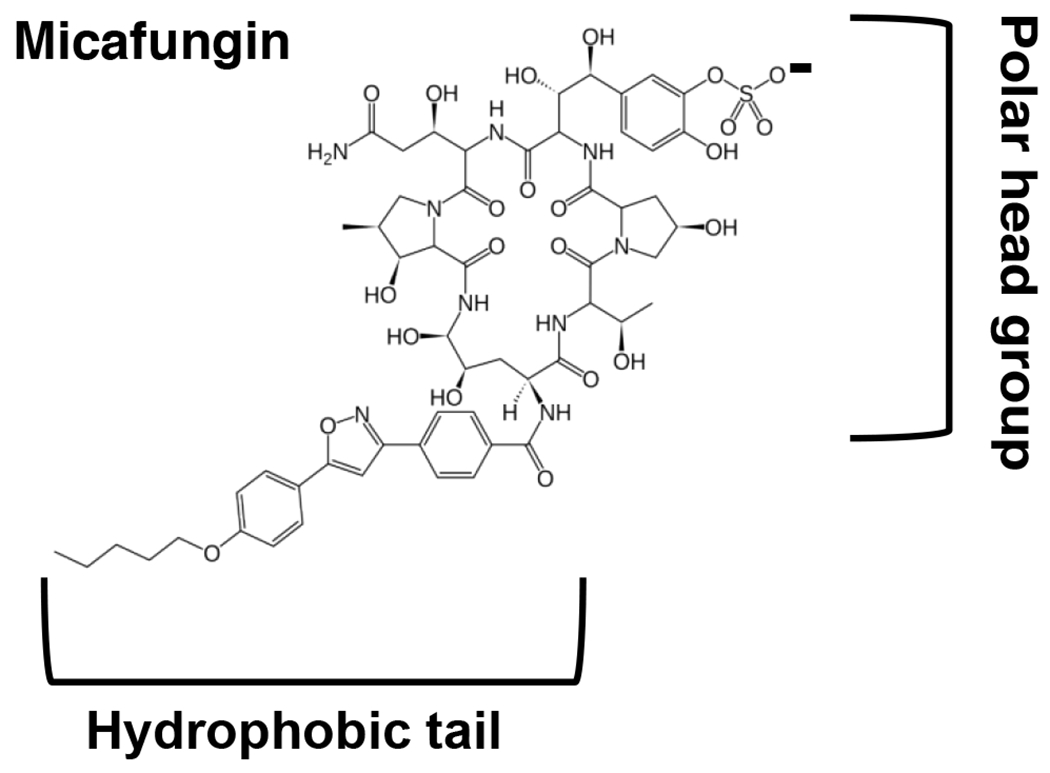

Naturally echinocandin CLPs are secondary compounds synthesized and released by filamentous ascomycetes (Huttel, 2021). Both micafungin (Figure 1) and caspofungin are semisynthetic derivatives of natural echinocandins that were created by pharmaceutical companies to minimize hemolytic activity (Fujie, 2007; Szymanski et al., 2022). Like all CLPs, the echinocandin CLPs are linear amphipathic molecules with a cyclic amino acid headgroup attached to a hydrophobic tail. The mostly noncanonical amino acid residues of the micafungin headgroup contain numerous groups capable of forming hydrogen bonds, including nine hydroxyl groups (Fig. 1). In addition, the hydroxy-tyrosine of micafungin contains a sulfate group, making the headgroup anionic at neutral pH (Fujie, 2007). The ionic form of micafungin, supplied as sodium micafungin, is soluble in water. In its solvated form, micafungin can approach the outer membrane (OMM) of isolated mitochondria. Water solvated micafungin may also diffuse into the inter-membrane space, via porin, to approach the outer leaflet of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM). From solution, the hydrophobic tail of the CLP reversibly partitions into the OMM and the outer leaflet of the IMM (Ko et al., 1994; Shirey et al., 2016). However, the hydrophilic and anionic nature of the micafungin headgroup will inhibit it from spontaneous flipping across the IMM; it cannot access the inner leaflet of the IMM or the mitochondrial matrix. With its hydrophobic tail inserted into a membrane bilayer leaflet, the hydrophilic amino acid headgroup of micafungin extends several angstroms above the surface of the membrane (Ko et al., 1994). As micafungin diffuses laterally within the lipid bilayers of the IMM or the OMM, it can bind to integral membrane protein in two different ways. The hydrophobic tail of micafungin can associate with the transmembrane surface of an integral membrane protein in the same manner as a fatty acid tail of a phospholipid. Simultaneously, the cyclic amino acid headgroup of micafungin may form hydrogen bonds and ion pairs with suitable residues located on the surface of the region of protein immediately above the surface of the membrane. One or several copies of micafungin likely bind to every accessible integral membrane protein or protein complex in mitochondria under our experimental conditions. In fact, our previous study (Shirey et al., 2016), plus this report, indicate that micafungin does alter the activity of more than one mitochondrial membrane protein, but far fewer than the total. Moreover, the mechanisms by which micafungin alters membrane protein activity varies in each case (Shirey et al., 2016). These results lead to the following conclusion: micafungin (or caspofungin) may alter protein activity if one or more of the micafungin-protein interactions (e.g. hydrogen bonds or ion pairs) alters the ability of a key protein residue(s) to perform a function necessary for protein activity. By chance, most micafungin-protein interactions formed in the mitochondria will not interfere with key residues vital for protein activity, and thus most micafungin-protein interactions will be silent.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of micafungin.

Background on the inner membrane anion channel of mitochondria.

In this study, we use mitochondria isolated from rat tissues and from Candida to demonstrate a powerful, novel effect of micafungin on the inner membrane anion channel (IMAC), an anion transfer activity discovered over three decades ago (Garlid and Beavis, 1986; Selwyn et al., 1979). The channel is voltage gated (Borecky et al., 1997; Misak et al., 2013) such that with a normal membrane potential it is mostly closed, but it flickers. With a low membrane potential, the channel is more open. Using well-characterized light scattering assays to measure ion transfer via mitochondrial swelling (Beavis et al., 1985; Garlid and Beavis, 1985), Beavis and colleagues have determined that IMAC transfers a wide variety of anions, but at different rates (Beavis, 1992; Beavis and Garlid, 1987, 1988; Beavis and Vercesi, 1992). The channel is inhibited by matrix Mg2+, as well as by increasing matrix pH (Beavis, 1992; Beavis and Garlid, 1987; Beavis and Powers, 1989). In contrast to the wealth of information about its activity, much about IMAC remains unknown, such as its physical identity. The most recent proposal is that IMAC is a mitochondrially located chloride intracellular channel termed CLIC5 (Mackova et al., 2018). In terms of function, IMAC has been postulated to attenuate mitochondrial swelling by working in concert with the K+/H+ antiporter to export anions and associated water as matrix [Mg2+] drops with the increase in matrix volume (Beavis, 1992; Beavis and Powers, 2004; Garlid and Beavis, 1986). More recent studies with cultured cardiomyocytes suggest that IMAC can open to allow the release of superoxide, perhaps to alleviate oxidative stress in situations such as cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (Akar et al., 2005; Aon et al., 2007; Aon et al., 2003; Biary et al., 2011).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials.

Horse heart cytochrome c was purchased from Lee Biosolutions. L-ascorbic acid, N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-phenylenediamine (TMPD), L-glutamic acid monosodium salt monohydrate, L-malic acid, antimycin A, 5,5’-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DNTB), acetyl CoA, oxaloacetic acid, tributyltin chloride (TBT), quinine hydrochloride dihydrate, cyclosporin A, sodium cholate and the Mg2+ ionophore A23187 were purchased from Sigma. Sodium micafungin (as Mycamine, Astellas) and caspofungin acetate (as Cancidas, Merck) were purchased from the University of Mississippi Medical Center Pharmacy. Aliquots of micafungin and caspofungin were prepared as 10 mM solutions in nanopure water and stored at −80°C; only freshly thawed CLPs were used in experiments. All other chemicals were of the highest grade required.

2.2. Isolation of intact mitochondria from the livers of Sprague-Dawley rats was performed using published methods (O’Toole et al., 2010; Shirey et al., 2016). Briefly, livers were washed with 20-30 ml of 220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose and 5 mM Mops pH 7.4 (MSM). The liver was minced thoroughly with a razor blade and gently homogenized in MSM supplemented with 1 mM EDTA and 2 mg/ml BSA using a 30 mL Teflon-glass homogenizer in which the diameter of the pestle was reduced by 1.0 mm using a lathe. Cellular debris was removed from the homogenate by centrifugation (700 X g, 10 min, 4°C), mitochondria were pelleted (5000 X g, 10 min, 4°C), and washed three to four times in 1 mL MSM buffer by gentle resuspension and then pelleting as above. The final pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of MSM buffer. This procedure produced 20-30 mg mitochondrial protein per liver with a respiratory control ratio (RCR) between 6-10 when assayed with 40 mM glutamate, 10 mM malate and 2 mM ADP in a buffer containing 50 mM Mops, 5 mM KH2PO4, 100 mM KCl and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4 (Shirey et al., 2016). Intact mitochondria from Candida albicans cells were prepared by a published protocol (Cavalheiro et al., 2004).

2.3. Swelling of isolated mitochondria was measured by monitoring the well-known decrease in light scattering that accompanies swelling by following a decrease in absorbance at 540 nm (Beavis et al., 1985; Schonfeld et al., 2000) in a Hitachi U-3000 spectrophotometer in an assay volume of 2 mL. The amount of mitochondria used and the composition of the composition of the assay solution are reported in the figure legends. The reactions were incubated for 5 min before the addition of micafungin or other agents being tested. The absorbance tracings of swelling assays that are shown in the figures are representative of assays that were replicated three or more times with essentially identical results.

2.4. Rupture of the inner mitochondrial membrane of rat liver mitochondria by swelling was measured by the release of citrate synthase activity into solution. Intact rat liver mitochondria (0.5 mg), suspended in 2 mL of 100 mM KCl, 5 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM EGTA and 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, were incubated with or without 25 μM micafungin for five minutes at 25C and then centrifuged at 16,200 x g for ten minutes to pellet the mitochondrial membranes. Citrate synthase activity in the supernatants was measured at 25C in a total volume of 2 mL by preparing reaction mixtures in a 6 well plate containing 200 mL supernatant, 1 mM 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DNTB), 0.3 mM acetyl CoA and 1% sodium cholate. The reactions were initiated by adding oxaloacetate to 0.5 mM. The production of citrate releases CoA-SH, which, in a coupled reaction, reduces DNTB to 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid (TNB). The increase in [TNB] was measured by monitoring an increase in absorbance at 412 nm (E=13.6 mM−1cm−1) using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader. The total citrate synthase activity present in the amount of rat liver mitochondria that corresponds to 200 μL of supernatant (0.05 mg mitochondrial protein) was measured in the same way. (The sodium cholate in the reaction mix opens the unswollen intact mitochondria of the control sample, releasing citrate synthase.)

2.5. Spectroscopic identification of soluble cytochrome c released from mitochondria.

Intact rat liver or Candida mitochondria (3.4 mg) were resuspended in 2 mL of 50 mM MOPS, 5 mM KH2PO4, 100 mM KCl and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4. Micafungin was added to a final concentration of 200 μM, the suspensions were incubated at 25°C for 5 minutes and then centrifuged at 16,200 X g for 10 min. Reduced minus oxidized spectra of the supernatants were obtained using a Hitachi U-3000 split-beam optical spectrophotometer after adding a few grains of sodium dithionite to the sample cuvette and a few crystals of potassium ferricyanide to the reference cuvette. Reduced soluble cytochrome c absorbs at 550 nm.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Micafungin induces the release of cytochrome c from intact mitochondria.

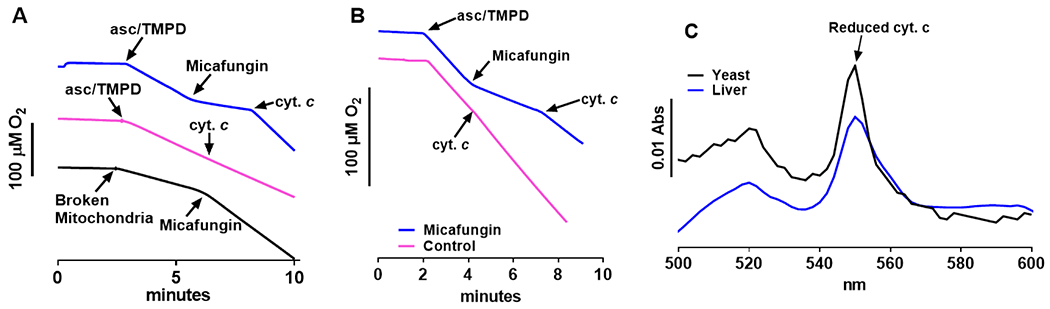

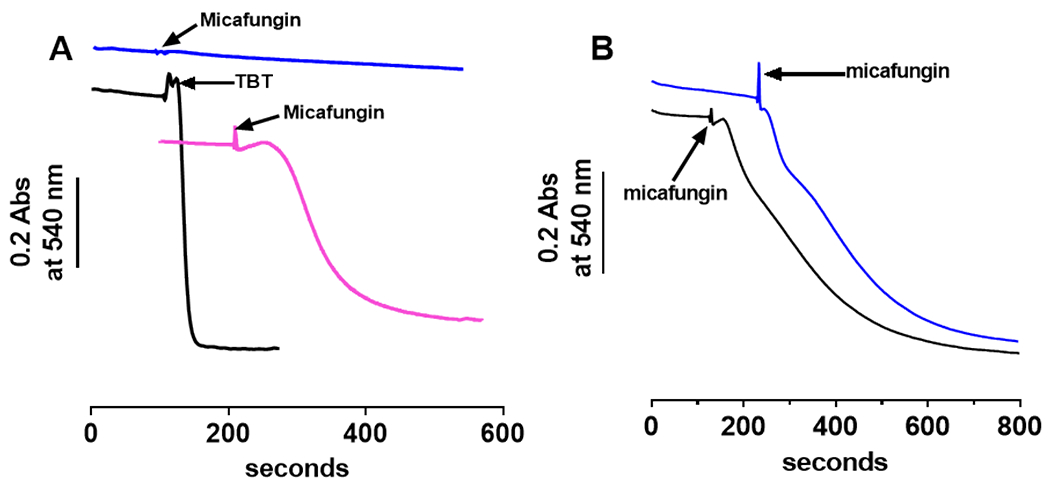

We first observed the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c upon the addition of micafungin during assays of complex IV activity using ascorbate and the electron mediator N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD) to re-reduce soluble cytochrome c in the IMS of isolated, intact rat mitochondria (Fig. 2A). In isolated, broken mitochondria, where the inner membrane is opened so that micafungin has access to both the outer and inner leaflets of the IMM, micafungin stimulates the activity of complex IV (Fig. 2A black trace) (Shirey et al., 2016). In intact isolated mitochondria, however, where micafungin can only insert into the outer leaflet of the IMM, we observed strong inhibition of CIV activity shortly after micafungin was added (Fig. 2A, blue trace), essentially within the response time of the oxygen electrode system. However, CIV activity was completely restored by the subsequent addition of a small amount of exogenous horse heart cytochrome c (Fig. 2A, blue tracing). This indicated that complex IV itself was not inhibited by micafungin, rather the CLP appeared to have created a path for the release of endogenous (rat) cytochrome c and for the entrance of exogenous (horse) cytochrome c. The pink tracing of Fig. 2A indicates that the OMM of the mitochondria was impermeable to exogenous cytochrome c prior to the addition of micafungin. Similar results were obtained using intact mitochondria isolated from the yeast Candida albicans (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that the effect of micafungin was not restricted to mammalian mitochondria. We confirmed that micafungin caused the release of soluble cytochrome c from rat liver and Candida mitochondria using optical spectroscopy (Fig. 2C). Using assays similar to the blue tracings of Figs. 2A and 2B, we found that micafungin also released cytochrome c from intact mitochondria isolated from rat heart and rat skeletal muscle (Fig. S1). The percentage of CIV activity that is lost upon the addition micafungin to intact mitochondria isolated from the various rat tissues and from Candida cells provides an estimate of the percentage of soluble cytochrome c released: 75% from rat liver mitochondria (calculated from Fig. 2A, blue trace) 82% from rat skeletal muscle mitochondria (from Fig. S1), 85% from rat heart mitochondria (from Fig. S1) and 70% from Candida albicans mitochondria (from Fig. 2B, blue trace). Results presented below indicate that the opening of the outer membrane is essentially complete, therefore the remaining cytochrome c is apparently bound to the surface of the IMM at the ionic strength of this experiment.

Figure 2.

Micafungin causes the release of soluble cytochrome c from intact mitochondria. (A) Rates of O2 consumption by complex IV were measured at 25°C using an Oroboros FluoRespirometer in 2 mL of 50 mM MOPS, 5 mM KH2PO4, 100 mM KCl and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4. In the blue tracing of panel A, 0.7 mg of intact rat liver mitochondria were present at time zero. CIV activity was initiated by the reduction of endogenous cytochrome c with 3 mM ascorbate and 0.3 mM TMPD. The addition of 25 μM micafungin inhibited CIV activity, which was then restored by the addition of 7 μM horse heart cytochrome c. The pink tracing is identical to the blue tracing except that no micafungin was added. The addition of 7 μM horse cytochrome c has no effect indicating that the outer membrane of the mitochondria is intact. The black tracing was obtained using 0.7 mg of broken rat liver mitochondria (prepared as in Shirey et al (13)), where micafungin has access to both sides of the IMM. Ascorbate, TMPD and 25 μM horse heart cytochrome c were present from time zero and CIV O2 consumption was initiated by the addition of mitochondria. The addition of 25 μM micafungin stimulates CIV activity, as previously seen (13). (B) The assays of panel B were performed and labeled as explained for the blue and pink tracings of panel A, except that intact Candida mitochondria were used. (C) Reduced minus oxidized optical spectra were used to confirm that cytochrome c was released by treating intact rat liver (blue) or Candida (black) mitochondria with micafungin (see Methods). The α peak of reduced cytochrome c appears at 550 nm and the β peak at 520 nm.

3.2. Cytochrome c is released via large amplitude matrix swelling induced by micafungin.

We considered three mechanisms by which micafungin could cause the release of cytochrome c from the IMS of intact mitochondria. First, since some CLPs are surfactants, we must address the evidence that shows that micafungin is not a surfactant capable of releasing cytochrome c. This evidence is presented in section 4.7.

A second possibility is that the binding of micafungin could activate the Bax and Bak proteins of the outer membrane to form a channel that releases cytochrome c from the IMS (Garrido et al., 2006; Gogvadze et al., 2006). However, Candida albicans does not synthesize Bax or Bak (Oettinghaus et al., 2011) but Candida mitochondria do release cytochrome c in response to micafungin (Fig. 2). Hence, an outer membrane channel composed of Bax or Bak is not required for micafungin-stimulated cytochrome c release.

A third mechanism for the release of cytochrome c is large scale swelling of the mitochondrial matrix that ruptures the OMM and perhaps the IMM as well. In this study, the rate and extent of mitochondrial swelling has been followed as a decrease in light scattering (an apparent decrease in absorbance) at wavelengths that avoid large absorbances by cytochromes (540 nm in our assays). The light scattering technique to monitor mitochondrial volume has been extensively characterized and validated, starting some 68 years ago (Tedeschi and Harris, 1955). As mitochondria swell, cristae unfold and the larger, water-filled matrix contains fewer structures that scatter light (Beavis et al., 1985; Hackenbrock, 1966). The influx of water into the matrix that causes swelling is driven by the uptake of ions and other solutes. In fact, the rate of swelling is directly proportional to the rate of ion uptake in appropriately designed ion transport experiments (Beavis and Garlid, 1987; Garlid and Beavis, 1985).

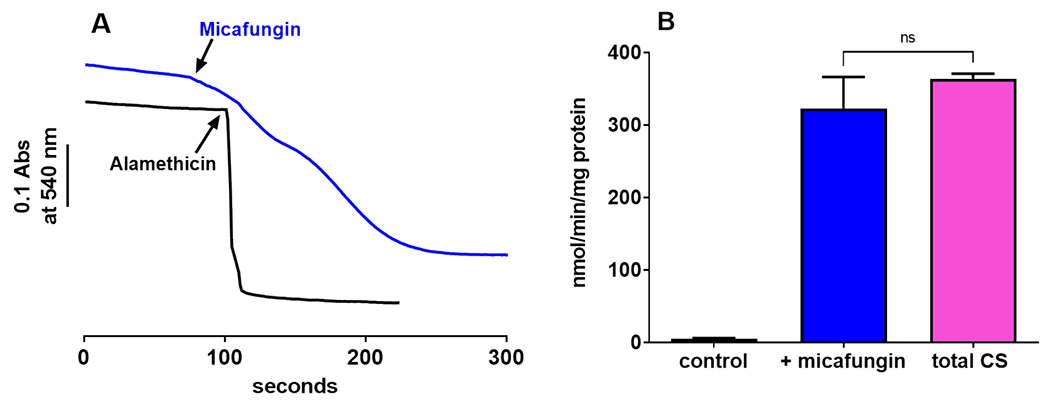

Maximum amplitude swelling of isolated mitochondria can be observed by adding the peptide alamethicin to form 18Å pores in the IMM (Li et al., 2008; Qian et al., 2008). These pores allow solutes and water to flow into the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 3A). Soluble cytochrome c is released from the IMS as the cristae of the IMM unfold and the expanding IMM causes the OMM to rupture (Li et al., 2008). Figure 3A shows that 25 μM micafungin induces mitochondrial swelling to the same extent as alamethicin, although the rate of swelling, i.e. the rate of water influx, is slower. In fact, ‘micafungin-induced mitochondrial swelling’ (hereafter referred to as MIMS) ruptures both the outer and inner membranes of mitochondria, since MIMS leads to the near complete release of citrate synthase, an enzyme of the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 3B). Note that the release of citrate synthase also confirms that the light scattering assay for mitochondrial swelling is actually measuring mitochondrial swelling.

Figure 3.

(A) Measurements of mitochondrial light scattering show that 25 μM micafungin (blue trace) and 20 μg/ml alamethicin (black trace) induced large scale swelling of intact rat liver mitochondria (0.7 mg) suspended in 100 mM KCl, 5 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM EGTA and 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.4. (B) Evidence for the rupture of rat liver IMM during caused by MIMS is indicated by the release of the matrix enzyme citrate synthase, measured as described in Methods. The control and ‘+micafungin’ columns indicate the citrate synthase activity released after five minutes in the absence or presence of 25 μM micafungin, while the total CS column shows the entire citrate synthase activity present in an equivalent amount of intact mitochondria (n=3-4; error as SEM; ns=not significant).

Swelling via MIMS is complete, i.e. swelling proceeds to the point at which both the outer and the inner mitochondrial membranes rupture, releasing the soluble contents of the IMS and the matrix. The kinetics of cytochrome c release are consistent with rupture of the outer membrane due to MIMS. At 140 nmol micafungin per mg total protein, the elapsed time between the addition of micafungin and the beginning of cytochrome c release is 60 seconds (taken from the analysis of O2 consumption tracings similar to the blue tracings of Fig. 2), while the time between the addition of micafungin and beginning of swelling is 30 seconds (taken from data similar to the blue tracing of Fig. 3A) (Both experiments were performed in the same buffer using the same amount of mitochondria.) Hence, the initiation of MIMS precedes the loss of cytochrome c.

3.3. Micafungin binds reversibly to a component of the inner mitochondrial membrane to induce swelling.

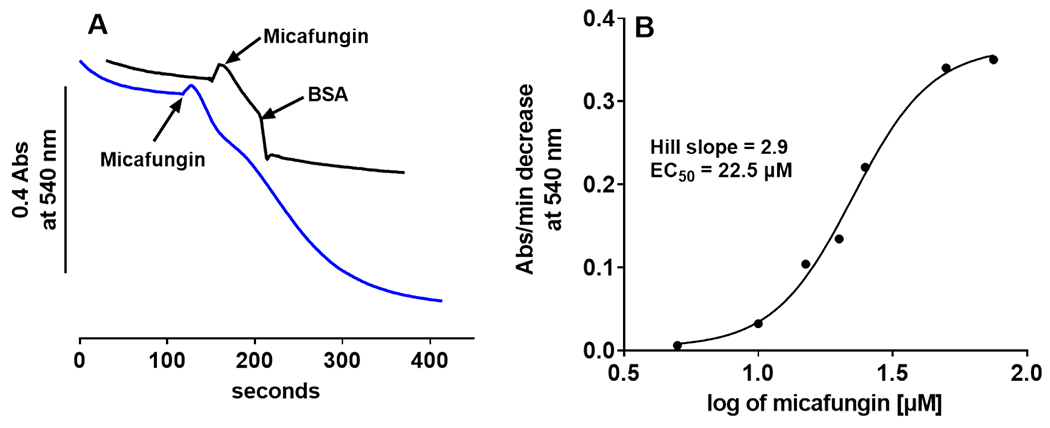

Micafungin binds to complexes III and IV of mitochondria to alter their activities, and an important part of the binding interaction is binding of the hydrophobic tail on the transmembrane surface of these integral membrane complexes (Shirey et al., 2016). Micafungin can be removed from complexes III and IV, with full reversal of activity changes, by adding bovine serum albumin (BSA) to bind the hydrophobic tail of the CLP (Shirey et al., 2016). Similarly, Fig. 4A shows that MIMS can be halted by the addition of BSA, indicating that the binding of micafungin is reversible and that continuous binding of micafungin to some component is required for MIMS. It is important to recognize that BSA, a protein with a molecular weight of 66.5 kDa, cannot approach the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) of intact mitochondria. The BSA remains outside of the outer membrane of the organelle. Therefore, in addition to revealing the reversible binding of micafungin to a protein component in the IMM, the reversal of MIMS by exogenous BSA also demonstrates the reversibility of the partitioning of micafungin between aqueous solution and the lipid bilayer of the IMM as well as the diffusion of micafungin through mitochondrial porin in the outer membrane of mitochondria.

Figure 4.

(A) Micafungin (25 μM)-induced swelling of 0.6 mg rat liver mitochondria suspended in 100 mM KCl, 5 mM KH2PO4, 1mM EGTA, 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.4 at 25°C (blue tracing) can be halted by the addition of bovine serum albumin to 1 mg/ml (black tracing). (B) The initial rate of swelling (measured as in panel A, blue tracing) vs. the log of the concentration of micafungin shows that micafungin binding is cooperative (Hill slope of 2.9) with an EC50 of 22.5 μM.

Given this reversibility, the strength of micafungin binding was characterized by plotting the rate of MIMS as a function of log [micafungin] (Fig. 4B). An EC50 of approximately 20 μM was determined, which is similar to the IC50 and EC50 values previously obtained for the binding of echinocandin CLPs to complexes III and IV (Shirey et al., 2016). Another similarity of the experiment of Fig. 4B to our previous studies is a Hill coefficient greater than 1.0, which indicates cooperative binding of micafungin to the target of MIMS. We have previously proposed (Shirey et al., 2016) that cooperative binding by the echinocandin CLPs arises from a situation where the displacement of a phospholipid molecule (with two fatty acid tails) by one CLP molecule (with one hydrophobic tail) leaves one fatty acid/hydrophobic tail binding site open, thus facilitating the binding of a second CLP. Overall, the binding experiments suggest that the target of micafungin to induce MIMS is an integral membrane protein in the IMM and that multiple copies of micafungin bind to the protein responsible for MIMS.

3.4. Micafungin does not induce formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP).

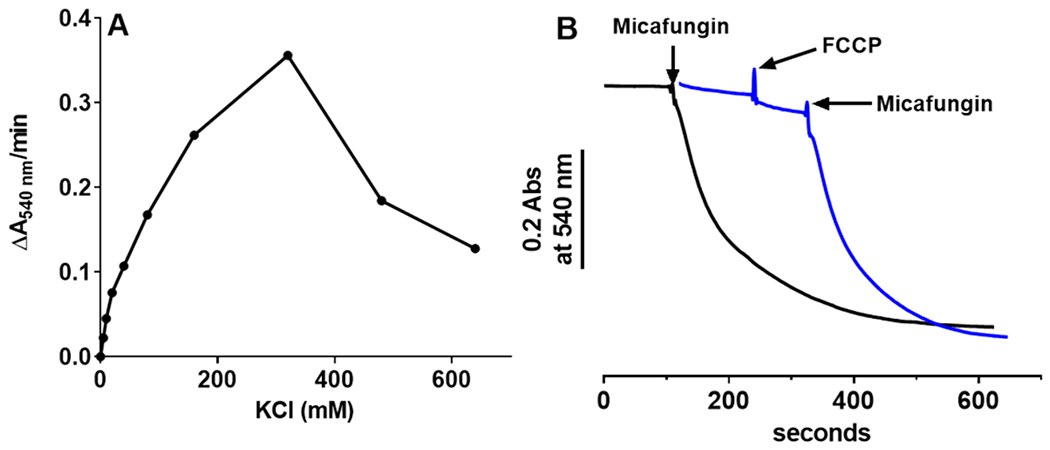

A well-known protein channel of the IMM that is capable of causing large amplitude swelling is the MPTP, which is normally activated under conditions of mitochondrial or cellular dysfunction (Halestrap and Pasdois, 2009; Nowikovsky et al., 2009; Webster, 2012). Upon opening, MPTP transfers molecules of up to 1500 Daltons in molecular weight (Bernardi, 2013). MPTP can be activated (opened) by Ca2+ (Bernardi, 2013; Izzo et al., 2016) and by tributyltin (Nishikimi et al., 2001) (Fig. 5A&B). In a low salt medium (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose and 5 mM MOPS, pH 7.4), large amplitude swelling of isolated rat liver mitochondria was observed with the addition of 0.5 μM tributyltin (Fig. 5A, black trace) or upon the addition of 200 μM Ca2+ (Fig. S2). Under these same low salt conditions, 25 μM micafungin fails to induce large amplitude swelling suggesting that micafungin does not cause swelling by activating MPTP (Fig. 5A, blue trace). Cyclosporine A (CsA) binds to the matrix protein cyclophilin D, a structural component of MPTP, to prevent the formation of MPTP (Sharov et al., 2007), as demonstrated in our mitochondria Fig. S2. Micafungin-induced mitochondrial swelling in 100 mM KCl, however, is not prevented by the presence of CsA (Fig. 5B). The result further indicates that the opening of MPTP does not cause MIMS.

Figure 5.

Micafungin-induced mitochondrial swelling (MIMS) is distinct from the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) since MIMS requires salt and MIMS is not inhibited by cyclosporine A. (A) When 0.4 mg intact, rat liver mitochondria are suspended in salt-free MSM buffer (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose and 10 mM MOPS pH 7.4) 0.5 μM tributyltin (TBT) induces rapid mitochondrial swelling (black tracing) by opening the MPTP (56). In MSM buffer without salt, 25 μM micafungin does not induce rapid swelling (blue tracing), but the CLP does induce swelling in MSM when 120 mM KCl is included (pink tracing). (B) Swelling induced by 25 μM micafungin in a buffer containing 0.3 mg rat liver mitochondria, 50 mM MOPS, 5 mM KH2PO4, 100 mM KCl and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4 (blue tracing) is not inhibited by the inclusion of 1 μM cyclosporine A prior to the addition of micafungin (black tracing). (A control for the inhibitory action of cyclosporine in our mitochondria is shown in Fig. S2.)

3.5. Micafungin induced swelling appears to be energetically driven and rate-limited by anion import into the matrix.

When intact mitochondria were suspended in a largely salt-free medium (220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose and 5 mM MOPS at pH 7.4) micafungin did not induce swelling (Fig. 5A, blue tracing). With the addition of 120 mM KCl to this medium, however, micafungin did induce mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 5A, pink tracing). In fact, the rate of MIMS increases with KCl concentration up to ~300 mM KCl (Fig. 6A). This dependence of the rate of swelling on the concentration of KCl indicates that influx of either K+ or Cl−, or both, and especially the water associated with these ions, cause MIMS. The concentration of K+ in the matrix of these freshly isolated mitochondria is close to the amount added in this experiment, ~120 mM (Rossi and Azzone, 1969). However, the concentration of Cl− in the matrix is low (Jahn et al., 2015). Hence, when the outside concentration of Cl− exceeds 4 mM, there exists a chemical potential for Cl− transfer into the matrix. The presence of a normal membrane potential (the electrical potential) would significantly offset this chemical potential and thus oppose the entry of Cl−. However, the addition of micafungin in the presence of a salt also leads to immediate collapse of the ΔΨ consistent with the fact that micafungin also inhibits complex III and halts mitochondrial electron transfer (Shirey et al., 2016). In fact, neither a pre-existing membrane potential nor electron transfer is required for MIMS (Fig. 6B). We conclude that the chemical potential for Cl− uptake drives MIMS when KCl is the salt present. It is likely that the chemical potential for the other anions used in this study likewise provide the driving force for swelling when these anions are paired with K+.

Figure 6.

(A) The rate of MIMS vs the concentration of KCl. Intact rat liver mitochondria (0.4 mg) were suspended in a buffer of 5 mM KH2PO4, 1mM EGTA and 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, plus KCl as indicated. MIMS was initiated by the addition of 25 μM micafungin. (B) Neither the initial rate nor the extent of MIMS (measured as in panel A plus 100 mM KCl; 25 μM micafungin added where indicated) depends upon a membrane potential, as shown by nearly equal rates of swelling in the presence of 1 μM of the uncoupler FCCP (blue tracing; swelling rate of 0.237±0.031 ΔA540nm/min) and in the absence of FCCP (black tracing; swelling rate of 0.252±0.017 ΔA540nm/min).

3.6. Micafungin-induced swelling requires an ionic interaction between the headgroup of micafungin and a component of the IMM.

The headgroup of micafungin is anionic due to the sulfonated hydroxy-tyrosine in its six amino acid-headgroup (Fig. 1). The echinocandin termed caspofungin is highly similar in structure to micafungin, but caspofungin is cationic rather than anionic (Shirey et al., 2016). The addition of caspofungin does not cause large scale mitochondrial swelling (Fig. S3), suggesting that the interaction of the anionic headgroup of micafungin with a protein(s) of the IMM is involved in the induction of MIMS. The effect of high concentrations of KCl on the rate of MIMS supports this conclusion. Above 300 mM KCl the rate of MIMS slows (Fig. 6A), likely because high concentrations of KCl disrupt the ionic interaction of the micafungin headgroup with its target protein in the IMM.

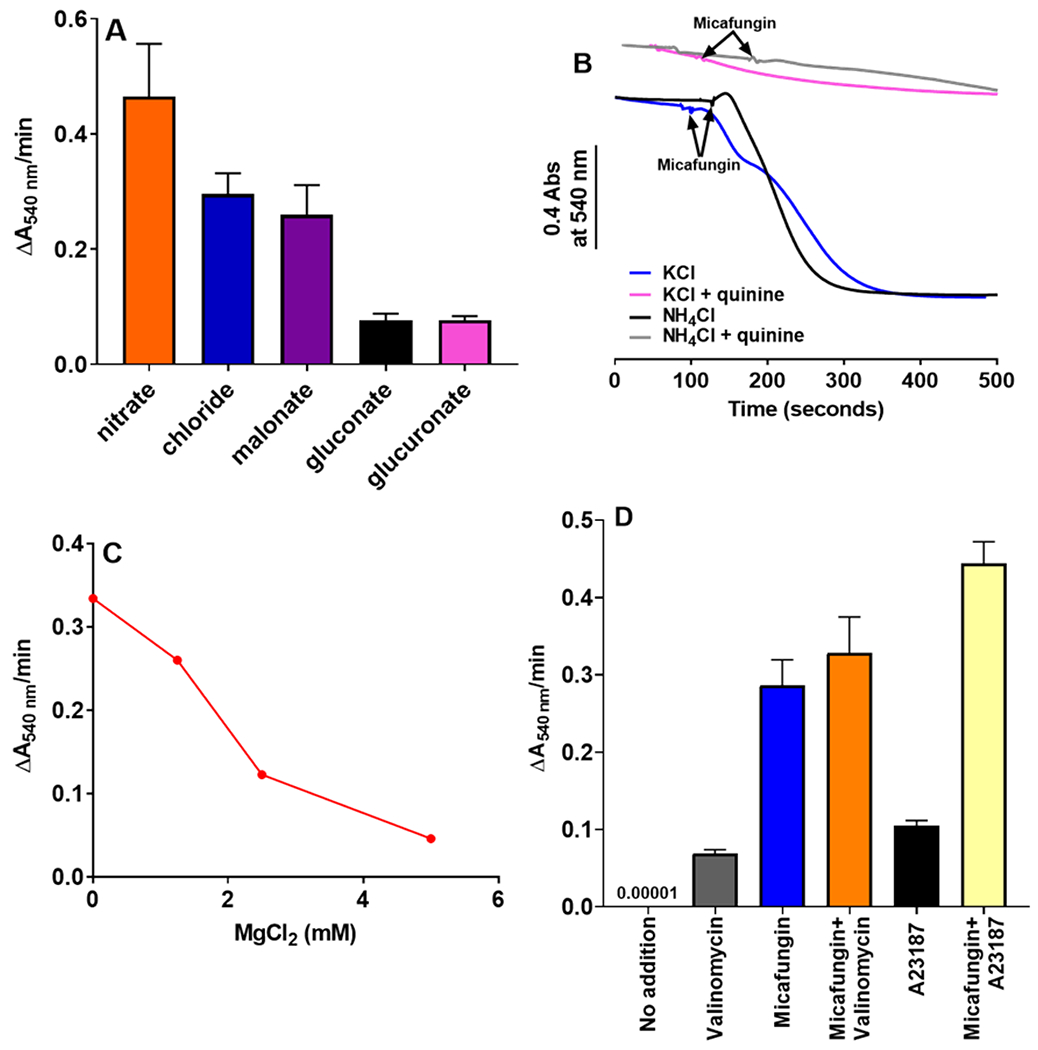

3.7. The inner membrane anion channel (IMAC) transfers anions during MIMS.

IMAC is not specific for Cl−, rather the activated channel is capable of transferring a wide variety of inorganic and organic anions across the inner membrane (Beavis and Garlid, 1987; Schonfeld et al., 2001; Schonfeld et al., 2000). The rates of anion transfer differ. Some anions, such as nitrate and Cl are transferred rapidly by IMAC, while others, such as gluconate and glucoronate, are transferred only at slow rates (Garlid and Beavis, 1986; Schönfeld et al., 2003). The rates of transfer of five anions by IMAC proceed in the following order: NO3− > Cl− malonate > gluconate > glucuronate (Beavis and Garlid, 1987). We find that the rate of MIMS generates an identical order of preference for these anions (Fig. 7A). The result provides a strong indication that IMAC is responsible for anion transfer during MIMS.

Figure 7.

(A) Comparing the initial rates of rat liver mitochondrial swelling induced by 25 μM micafungin in buffers containing 0.4 mg mitochondria, 5 mM KH2PO4, 1mM EGTA, 50 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, plus 100 mM of one of the following salts: potassium chloride, potassium gluconate, sodium nitrate, sodium malonate or sodium glucoronate. Error bars are SEM with an n=2-5. (B) Traces of micafungin-induced mitochondrial swelling, performed as in panel A, using either 100 mM KCl or 100 mM NH4Cl as the salt plus 500 μM quinine as indicated. (C) Swelling of rat liver mitochondria (0.5 mg) induced by 25 μM micafungin is inhibited by mM concentrations of MgCl2. (D) The initial rates of swelling by rat liver mitochondria (0.4 mg) in a buffer containing 55 mM KCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 1 μM cyclosporine A, and 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.4. The additions indicated, used to initiate swelling, were 2 μM valinomycin, 25 μM micafungin and 4.75 μM A23187. Error bars are SEM with an n=2-5.

The tertiary amine quinine inhibits IMAC with an IC50 of approximately 250 μM (Garlid and Beavis, 1986). Using KCl as the salt, MIMS is strongly inhibited by 500 μM quinine (Fig. 7B, blue vs pink tracings)). Since quinine also inhibits cation transporters of the IMM, such as the K+/H+ exchanger (Garlid et al., 1986), we tested MIMS for quinine sensitivity of IMAC more selectively by using ammonium chloride as the salt. Ammonium equilibrates across the IMM via passive diffusion of its deprotonated form, NH3 (Brierley et al., 1970), thereby bypassing protein transporters. MIMS in the presence of NH4Cl is rapid, but it is still strongly inhibited by 500 μM quinine (Fig. 7B, black vs gray tracings). We concluded that quinine inhibits anion transfer across the membrane, rather than cation transfer, consistent with the function of IMAC as the anion transporter.

IMAC activity is inhibited by increased Mg2+ levels in both the IMS and matrix compartments (Beavis and Powers, 1989). The binding of Mg2+ from the IMS side of the IMM inhibits IMAC with an IC50 of approximately 0.5 mM in rat liver mitochondria (Beavis and Powers, 1989). We found that millimolar concentrations of Mg2+ added to the outside of intact rat liver mitochondria strongly inhibited MIMS (Fig. 7C) consistent with the involvement of IMAC.

The activity of IMAC is also strongly controlled by Mg2+ that binds to the channel from the matrix (Beavis and Powers, 1989; Schonfeld et al., 2004). Matrix Mg2+ inhibits IMAC with an IC50 about 10-fold less than external Mg2+ (Beavis and Powers, 1989). The concentration of Mg2+ in the matrix can be lowered by adding the lipophilic Mg2+ chelator A23187 to intact mitochondria, along with EDTA to sequester the metal upon exit (Beavis and Powers, 1989). Using 55 mM KCl, we found that the rate of MIMS is increased by 50% when this procedure is used to deplete matrix Mg2+ (Fig. 7D, blue vs yellow). Again, the result is consistent with the action of IMAC during MIMS.

3.8. Micafungin speeds both anion and cation transfer across the IMM.

As detailed above, IMAC transfers the anion of the required salt during MIMS. Hence, when KCl is the available salt, IMAC transfers Cl− but the pathway for K+ transfer during MIMS remains to be defined. Known pathways for K+ across the IMM in mammalian mitochondria include three or more K+ channels (Laskowski et al., 2016; Szewczyk et al., 2009) plus a K+/H+ antiporter (Brierley et al., 1984; Hashimi et al., 2013). Both K+ and Cl− must be transferred across the IMM at equal rates during continuous ion-dependent swelling. If not, a membrane potential will rapidly form, inhibit further ion transfer and stop swelling.

Intact rat liver mitochondria lacking a membrane potential show a negligible rate of swelling when they are suspended in a hypotonic buffer containing 55 mM KCl (Fig. 7D, ‘no addition’) (Beavis and Garlid, 1987), a concentration of KCl at which there exists a significant chemical potential for the uptake of Cl− (Jahn et al., 2015). The addition of the potassium ionophore valinomycin provides a pathway for the rapid transfer of K+ across the IMM (Moore and Pressman, 1964), initiates swelling (Fig. 7D, gray bar), as previously shown by Beavis et al (Beavis and Garlid, 1987) using similar reaction conditions. This indicates that IMAC is capable of Cl− transfer in these mitochondria, but only when a charge-neutralizing cation is transferred at the same time. In agreement with Beavis (Beavis and Garlid, 1987), the absence of mitochondrial swelling without an exogenous K+ transfer agent, such as valinomycin, indicates that the K+ channels and the K+/H+ antiporter of the IMM do not perform significant import of K+ into the matrix under these conditions.

When micafungin is added to isolated rat liver mitochondria, rather than valinomycin, the initial rate of swelling increases four-fold in comparison to the rate seen with valinomycin (Fig. 7D, blue vs gray). Treatment with both micafungin and valinomycin has essentially the same effect as treatment with micafungin alone (Fig. 7D, orange). Since the rate of swelling with KCl as the salt is proportional to the rate of Cl− and K+ transfer, the data of Fig. 7D indicate that micafungin strongly enhances the transfer of both Cl− and K+ across the IMM, a result that we evaluate in Discussion. When coupled with our previous conclusion that Cl− is being transferred through IMAC during MIMS, the finding that micafungin increases the rate of Cl− transfer strongly argues that micafungin has a direct effect on IMAC.

3.9. The effects of micafungin and matrix Mg2+ levels on ion transfer are distinct.

Previous work has shown that the swelling of isolated mitochondria in the presence of potassium salts can be initiated by lowering the concentration of Mg2+ in the matrix (Beavis and Garlid, 1987; Schonfeld et al., 2002). Lowered matrix Mg2+ levels increase the activity of both IMAC (Beavis, 1992) and the K+/H+ antiporter of the IMM (Nakashima and Garlid, 1982), opening pathways for both K+ as well as Cl− and other anions. Treatment of our rat liver mitochondria with A23187/EDTA lowered the concentration of Mg2+ in the matrix and initiated swelling in the presence of 55 mM KCl (Fig. 7D, black), in agreement with Beavis and Garlid (Beavis and Garlid, 1987). The addition of micafungin, along with the depletion of matrix Mg2+, increased the initial rate of swelling (i.e. the rate of K+ and Cl− uptake, by more than four-fold led to (Fig. 7D, black vs. yellow) In fact, the rates of swelling with only micafungin (Fig. 7D, blue) and with only Mg2+ depletion (Fig. 7D, black) are additive (Fig. 7D, yellow), suggesting that the effects of micafungin and Mg2+ depletion are separable. This is consistent with IMAC topology in mitochondria, in that micafungin has access to the outer (IMS) region of IMAC while matrix Mg2+ depletion alters the activity of IMAC from its inner (matrix) region. Assuming that the effects of Mg2+ depletion and micafungin on IMAC-dependent mitochondrial swelling are separable and distinct, the stimulation of IMAC by micafungin is due to a process other than the depletion of matrix Mg2+.

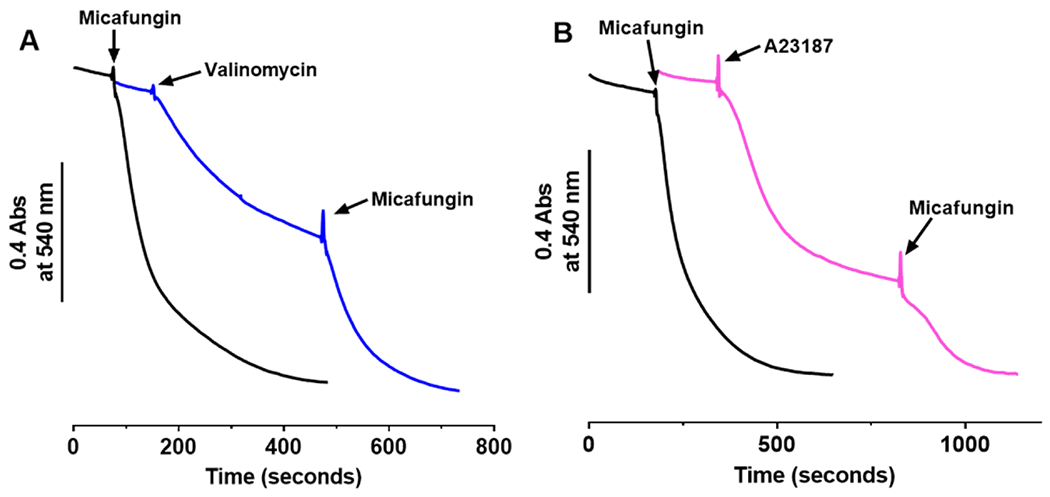

3.10. Micafungin appears to increase the conductivity for chloride through IMAC.

Previous studies have shown that the swelling of mitochondria with KCl plus valinomycin slows before the complete rupture of all of the mitochondria, as measured by the extent of release of matrix enzymes (Schonfeld et al., 2002). The endpoint of valinomycin-induced KCl-dependent swelling in the absence of micafungin is indicated as an approach to a plateau in a swelling experiment of Fig. 8A (blue trace). As described above, the driving force for IMAC-dependent mitochondrial swelling in the presence of KCl is the chemical potential for Cl− across the IMM. However, the other factor that limits the rate of swelling in the presence of KCl is the permeability or conductivity of IMAC for Cl−. (The presence of valinomycin provides high conductivity for K+, making it highly unlikely that the rate of K+ transfer could limit the rate of swelling.) When micafungin was added at the point where valinomycin-induced KCl-driven swelling begins to plateau, the rate of swelling increased again and swelling proceeded to the end point seen in the presence of micafungin alone (Fig. 8A), i.e. to complete mitochondrial rupture. This resumption of swelling upon the addition of micafungin in Fig. 8 (blue trace) indicates that there is still sufficient driving force from the chemical potential of Cl− to drive swelling. We can conclude, then, the plateau in swelling in the absence of micafungin occurs when the driving force for Cl− uptake through IMAC reaches equilibrium with the resistance for Cl− transport through IMAC. That micafungin re-establishes Cl− transfer at this point indicates that micafungin lowers the resistance for Cl− transfer, i.e. micafungin increases the conductivity for Cl− transfer by IMAC.

Figure 8.

In buffer containing 0.4 mg mitochondria, 55 mM KCl, 1 μM cyclosporine A, 2.5 mM EDTA, and 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.4, mitochondrial swelling in the presence of 2 μM valinomycin (A) or 4.75 μM A23187 (B, pink) begins to plateau before complete mitochondrial rupture but swelling resumes upon the addition of 25 μM micafungin. Traces of mitochondrial swelling induced by only 25 μM micafungin are shown in black.

The same conclusion was reached in the experiment of Fig. 8B, in which the activation of IMAC by the depletion of matrix Mg2+ (by the ionophore A23187) was used to initiate swelling of rat liver mitochondria. An approach to a plateau is seen in the magenta trace, apparently as the driving force of the chloride chemical potential begins to be opposed by the resistance for chloride transfer through IMAC. Micafungin then reduces this resistance to Cl− transfer so that swelling proceeds to complete rupture. Apparently, micafungin increases the conductivity for Cl− through IMAC to a greater extent than does the stimulation of IMAC activity by matrix Mg2+ depletion.

4. DISCUSSION

In sections 4.1–4.5 below, we discuss key findings established by our data and develop a hypothesis of the mechanism of MIMS. Section 4.6 presents our arguments against an alternative hypothesis, that micafungin causes MIMS independently of IMAC. The significance of the study is discussed in section 4.7.

4.1. Micafungin induces the rapid transfer of salts across the IMM.

The addition of micromolar concentrations of the CLP micafungin to mitochondria isolated from rat livers, rat hearts (Fig. S1) as well as from Candida, results in rapid, large-scale mitochondrial swelling that ruptures both the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes. The influx of water during this micafungin-induced mitochondrial swelling (MIMS) is driven by the uptake of various salts (e.g. KCl) across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM). While MIMS is as complete as swelling caused by the formation of water-filled pores, e.g. alamethicin or the membrane permeability transition pore, MIMS results from ion transfer through a protein ion channel. The energy for MIMS is supplied by the chemical potential for anion uptake.

4.2. The inner membrane anion channel (IMAC) is involved in MIMS.

The specificity of anion uptake, the rates of MIMS with different anions and the sensitivity of MIMS to Mg2+ and quinine identifies the inner membrane anion channel (IMAC) as the entity that transfers anions during MIMS. An unusual feature of IMAC is its capability to transfer some large, non-physiological anions, such as ferrocyanide (molar mass ~212) (Beavis and Garlid, 1987). Indeed, potassium ferrocyanide supports MIMS (Fig. S4A), consistent with the involvement of IMAC.

4.3. Micafungin reprograms IMAC to transfer both anions and cations.

Mitochondrial swelling in the presence of KCl is very slow unless rapid K+ transfer is made possible by adding valinomycin (Fig. 7D). This indicates that neither the K+ channels nor the K+/H+ antiporter of the IMM, in their normal state, are capable of supporting the rapid rates of K+ transfer required for MIMS. We could postulate that, in addition to altering IMAC, micafungin also reprograms a K+ channel or changes the activity of the K+/H+ exchanger in order to speed K+ transport. However, we have found that Na+ sustains MIMS as well as K+ (Fig. S4B). This would require that sodium channels or the Na+/H+ exchangers are also modified by micafungin. Clearly the simplest proposal is that MIMS requires only the modification of IMAC by micafungin and that IMAC transfers both anions and cations during MIMS.

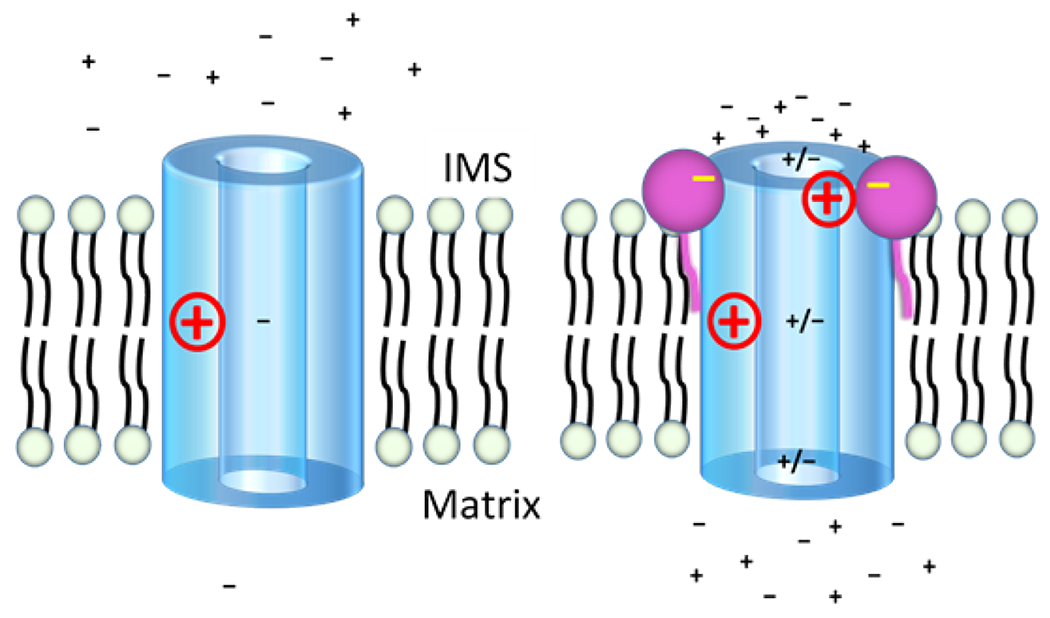

How might micafungin physically alter IMAC so that it is capable of transferring cations along with anions? For one thing, IMAC doesn’t have that far to go. Unmodified IMAC is not strongly selective for anions vs cations; the permeability ratio of Panion/PK+ varies from 3.2 to 4.3 depending upon the anion being transferred (Misak et al., 2013). An important clue comes from the finding that between cationic caspofungin and anionic micafungin, only the latter alters the function of IMAC (Fig. S3), even though both CLPs have a similar headgroup structure (Shirey et al., 2016). Apparently, an electrostatic interaction involving the negatively charged sulfonate of the micafungin headgroup is key for MIMS. As discussed in Introduction and section 3.3, it seems probable that multiple molecules of micafungin surround the region of IMAC that extends into the IMS. Hence, the ability of anionic micafungin to lower the Panion/PK+, Na+ value to 1 may simply result from the electrostatic attraction of cations to the mouth of the pore (Fig. 9). Electrostatic attraction has been proven to alter ion channel activity; Brelidze et al (Brelidze et al., 2003) demonstrated that a ring of acidic residues at the entry to the pore of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel doubled its conductance.

Figure 9.

A proposed model for how micafungin stimulates both cation and anion transfer through inner membrane anion channel (IMAC) of mitochondria. While the structure of IMAC remains unknown, IMAC is depicted as a cylinder with a wide pore because the channel transfers ions with a wide range of sizes. A positive charge halfway through the pore indicates an electropositive filter (such as a lysine side chain) that many anion channels employ to limit cation transfer. Since MIMS does not respond to the presence or absence of an initial membrane potential (see text), no potential is indicated. The left panel shows IMAC in the absence of micafungin as an anion channel of low conductance. The right panel posits that the addition of micafungin allows several micafungin molecules (only two are shown) to bind around the IMS entry of the pore of IMAC. The negative charges of the bound micafungin molecules attract mobile cations to the pore entry, the mobile cations attract mobile anions and a resulting increase in the local concentration of ions allows formation of cation/anion pairs that avoid rejection by electropositive filters as they transit the IMAC pore. The micafungin molecule on the right is shown to be neutralizing a positive side chain near the IMS mouth of the pore, as may be the case if a CLIC5 protein is IMAC (see text). This would also allow an increase in the concentration of cations near the pore entry. The net direction (into the matrix) and the energy for ion transfer is provided by the chemical potential for anions.

4.4. Micafungin causes increased conductance of both anions and cations.

The results presented in section 3.8 demonstrate that micafungin increases the conductivity of Cl− through IMAC. In addition to the increase in conductivity, both cations and anions must be transferred through IMAC at equal rates during MIMS. If, for example, K+ was transferred through IMAC more slowly than Cl− during MIMS, we would expect that the rate of swelling would increase upon the addition of the K+ ionophore valinomycin, since the ionophore would speed K+ transfer to the maximum rate allowed by Cl− conductance. However, the data of Fig. 7D show that valinomycin does not significantly increase the rate of MIMS. We conclude that when IMAC is altered by micafungin, K+ flows as fast as Cl− through the ion channel.

We postulate that the increased rate of anion and cation transfer through micafungin-altered IMAC results from the passage of the ions through IMAC as anion-cation pairs (Fig. 9). An increased local concentration of cation at the pore entry should promote cation-anion pairing and the neutrality of ion pairs will make cation transfer less sensitive to electropositive, cation-repulsing filters that are often present in anion channel pores (Corry and Chung, 2006; Fahlke, 2001; Keramidas et al., 2004). The size flexibility of IMAC (Beavis, 1992; Beavis and Garlid, 1987; Misak et al., 2013) argues against narrow structural filters within the ion pore that would restrict the passage of most cation-anion pairs on the basis of increased size. For example, unmodified IMAC transports the octahedral, tetravalent ferrocyanide (FeC6N6) anion, with a MW ~212, at 62% of the rate that it transfers the single atom, monovalent chloride ion (MW ~35.5) (Beavis and Garlid, 1987).

4.5. An electrostatic alteration of IMAC by micafungin is consistent with the proposal (Mackova et al., 2018) that IMAC is a CLIC5 channel.

“Chloride intracellular channel” (CLIC) proteins have the remarkable feature of existing as soluble, globular proteins that can insert into membranes to form anion channels (Littler et al., 2010; Singh, 2010; Warton et al., 2002). They are highly conserved in vertebrates and present in both the cytoplasm and organelles of cells. A CLIC5 protein present in mammalian IMM (Fernandez-Salas et al., 1999; Ponnalagu and Singh, 2017) has been proposed by Mackova et al (Mackova et al., 2018) to be IMAC. While a high-resolution structure of a CLIC protein in its membrane channel form is yet unavailable, Singh (Singh, 2010) used existing data to produce a structural model of CLIC channels, i.e. after the soluble protein inserts into the membrane. The model predicts a homo-tetramer of membrane-inserted CLIC proteins, with four identical alpha helices, one from each monomer, forming an ion pore. If mitochondrial CLIC5 is IMAC, the Singh model (Singh, 2010), plus the amino acid sequence of mitochondrial CLIC5 (Fernandez-Salas et al., 1999), predict that a ring of four arginine residues will be present at the opening of the IMAC ion pore exposed to the IMS, assuming that mitochondrial CLIC5 inserts from the matrix, as expected. Hence, an additional role for micafungin may be to electrostatically neutralize the arginine sidechains that normally repel the entry of cations (Fig. 9).

4.6. Could micafungin cause MIMS in the absence of IMAC?

The entire group of CLPs have been found to have widely variant capabilities and actions (Balleza et al., 2019; Geudens and Martins, 2018). Of relevance to this study is that some CLPs have detergent-like activity and can open membranes (Heerklotz and Seelig, 2007; Oftedal et al., 2012), while others enter membranes to form ion pores (Maget-Dana & Peypoux, 1994). Although micafungin has never been reported to have either of these activities, we still must address why we are not proposing that micafungin, acting alone, might act as a detergent to release mitochondrial proteins into solution or to form an ion pore in the membranes that leads to mitochondrial swelling and then the release of mitochondrial proteins.

One observation and three experiments argue against the ability of micafungin to function as a membrane detergent in order to release cytochrome c and citrate synthase in our experiments. First, upon the addition of 25 μM micafungin to isolated mitochondria in the presence of KCl and other selected salts, mitochondrial swelling begins quickly and proceeds rapidly. Micafungin would have to be a strong detergent to have such a rapid effect. However, as a drug for humans, micafungin has been deliberately engineered to have minimal ability to disrupt the cytoplasmic membrane of red blood cells, i.e. micafungin is designed to have minimum detergent activity (Fujie, 2007). Second, data presented in Fig. 5A indicate that micafungin lacks strong detergent activity. When tributyltin opens the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, the rapid influx of sucrose, mannitol, MOPS draws water rapidly into the matrix. This causes rapid, large-scale swelling, seen by the ~0.4A decrease in light scattering. However, when 25 μM micafungin is added to the same mitochondria, suspended in the same MSM buffer, no rapid swelling takes place. Apparently, micafungin is not opening the mitochondrial membranes, as would a strong detergent, in order to allow the influx of water, sucrose and mannitol. Third and fourth are two independent liposome experiments. Concentrations of micafungin and similar echinocandin CLPs up to 150 μM are unable to effect the release of Rb+ (Kurtz et al., 1994) or the entry of K+ or H+ into liposomes (Shirey et al., 2016) in the presence of high ion gradients across the liposome membranes. A strong, or even mild, detergent would rapidly open the liposomes to allow ion leak.

In addition to surfactant properties, some CLPs form ion pores (Maget-Dana and Peypoux, 1994). We have shown that MIMS involves the rapid uptake of anion-cation pairs. If micafungin alone formed such an anion-cation pore in membranes, it would have to be the most active CLP ion pore yet discovered. Even so, what data argues against the possibility that micafungin can form an ion pore with all of the characteristics that we have detailed for micafungin-altered IMAC? We present three separate arguments. One, we have shown that 100 mM NaCl is as effective in supporting MIMS as is 100 mM KCl (Fig. S4B). The bloodstream of animals and humans contains NaCl at concentrations greater than 100 mM. If micafungin alone were to form a membrane pore that rapidly transferred NaCl across the cytoplasmic membrane, micafungin should be highly toxic to animals and humans, since the concentrations of micafungin used therapeutically are similar to those used in these experiments. Yet micafungin is in wide clinical use and is well-tolerated in animals (Koch et al., 2015) and humans (Kofla and Ruhnke, 2011), which, in part, we attribute to the fact that IMAC is not present in cytoplasmic membranes of animals. Two, for a CLP to form a pore in a membrane, both the tail and the headgroup of the CLP must enter the membrane as multiple copies of the CLP organize to form a transmembrane pore (Balleza et al., 2019; Ines and Dhouha, 2015; Maget-Dana and Peypoux, 1994). For example, fluorescence analyses of a tyrosine present in the headgroup of the pore-forming CLP iturin A indicates that the cyclic amino acid headgroup of iturin A is present within the hydrophobic region of the membrane (Harnois et al., 1989). However, a similar analysis of the tyrosine located in the amino acid headgroup of the echinocandin CLP cilofungin, which is structurally similar to micafungin, indicates that the heavily hydroxylated headgroups of the echinocandin CLPs stand above the membrane surface, in a hydrophilic environment, and do not enter the membrane (Ko et al., 1994). The homologous tyrosine of micafungin is sulfonated (Fig. 1), and therefore carries a full negative charge pH 7.4, an additional feature that should prevent its headgroup from entering the lipid bilayer. Since the headgroup of micafungin does not enter the membrane, it cannot form a transmembrane ion pore. Three, if we assume that the IMAC inhibitor quinine does not also inhibit an ion pore constructed of only micafungin monomers, then nothing should prevent rapid ion transfer and mitochondrial swelling when micafungin is added in the presence of KCl and quinine. In contrast, rapid ion transfer and mitochondrial swelling is prevented by quinine (Fig. 7B), indicating that IMAC is involved. We conclude that micafungin alone is highly unlikely to promote MIMS by acting as a detergent or an ion pore.

4.7. Significance of the findings.

Several reports indicate that mitochondrial toxicity plays a role in the ability of micafungin and caspofungin to kill Candida cells (Chamilos et al., 2006; Dagley et al., 2011; Garcia-Rubio et al., 2021; Shingu-Vazquez and Traven, 2011). There exists the possibility that MIMS plays a role in the antifungal activity of micafungin, based upon the following. The intracellular release of cytochrome c by MIMS (as demonstrated for isolated mitochondria of Candida in this manuscript) should initiate mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in Candida (Seong and Lee, 2018). In fact, micafungin has been demonstrated to cause mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (Shirazi and Kontoyiannis, 2015; Shirazi et al., 2015). An unknown is how micafungin would get inside Candida cells to access their mitochondria. However, unlike human cells, Candida cells depend on a strong cell wall to maintain the integrity of their cytoplasmic membranes (Hasim and Coleman, 2019). Subsequent to micafungin’s inhibition of glucan synthase and weakening the fungal cell wall, it is possible that micafungin leaks across the osmotically fragile cytoplasmic membrane to access Candida mitochondria.

This study also reinforces the concept that non-surfactant CLPs are a largely untapped resource for developing modifiers of membrane protein activity. Including this report of micafungin modification of IMAC activity, micafungin has been demonstrated to have four strong effects on specific membrane proteins other than its inhibition of fungal glucan synthase. Micafungin inhibits complex III of isolated mitochondria with an IC50 of 5-8 μM. We have proposed that the hydrophobic tail of micafungin binds to the transmembrane surface of the cytochrome b protein of complex III, while the amino acid headgroup binds to the Fe-S protein atop cytochrome b, immediately above the membrane surface (Shirey et al., 2016). The anchoring of the Fe-S protein to cytochrome b by micafungin would restrict the up and down motion of the Fe-S protein that is required for complex III activity. A similar tethering activity may explain the ability of micafungin to prevent the entry of dengue virus into Vero cells (Chen et al., 2021). Chen et al (Chen et al., 2021) present evidence that micafungin binds to an envelope protein of the dengue virus that is necessary for transfer of the virus across the plasma membrane. Micafungin may prevent the release of the virus into the cytoplasm if its hydrophobic tail inserts into the plasma/endosome membrane while the CLP headgroup remains bound to the virus envelope protein. Finally, low micromolar concentrations of micafungin strongly stimulate the activity of complex IV in isolated IMM, probably by increasing the process of proton uptake via its negative charge (Shirey et al., 2016). In this study, our proposed mechanism for MIMS also depends upon the negative charge of the micafungin headgroup (Fig. 9).

Finally, future studies of micafungin-induced mitochondrial swelling may help to confirm the identity of IMAC, as well as its presence in various species and in different tissues. The swelling assay is simple once mitochondria have been isolated, far simpler than inhibitor and patch clamping studies that have already been extensively employed (Beavis, 1992; Borecky et al., 1997; Mackova et al., 2018; Misak et al., 2013; Ponnalagu and Singh, 2017). For example, using MIMS with the large number of yeast mutants lacking various mitochondrial proteins may be useful in identifying the protein components of IMAC.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The addition of the cyclic lipopeptide micafungin to mitochondria isolated from rats and Candida causes the rapid release of cytochrome c and matrix enzymes.

Micafungin induces rapid mitochondrial swelling with the rupture of both membranes of the organelle.

Swelling ensues as micafungin increases the activity of the inner mitochondrial anion channel (IMAC).

Micafungin apparently participates in an electrostatic interaction that causes IMAC to transfer both anions and cations as ion pairs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs. Romain Harmancey, Somjade J. Songcharoen, and Bernadette Grayson (all at the University of Mississippi Medical Center) for their help in supplying rat tissues. We thank Drs. John Cleary and Kayla R. Stover for supplying micafungin. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM121334. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CLP

cyclic lipopeptide

- EC50

half-maximal stimulatory concentration in a dose–response plot

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- MSM

buffer containing 220 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 5 mM Mops pH 7.4

- IMAC

inner membrane ion channel

- CIII

complex III of the mitochondrial electron transport chain

- CIV

complex IV of the mitochondrial electron transport chain

- MIMS

micafungin induced mitochondrial swelling

- TMPD

N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-phenylenediamine (TMPD)

- DTNB

5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- TBT

tributyltin chloride

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akar FG, Aon MA, Tomaselli GF, O’Rourke B, 2005. The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J Clin Invest 115, 3527–3535, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16284648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Maack C, O’Rourke B, 2007. Sequential opening of mitochondrial ion channels as a function of glutathione redox thiol status. J Biol Chem 282, 21889–21900, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17540766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Marban E, O’Rourke B, 2003. Synchronized whole cell oscillations in mitochondrial metabolism triggered by a local release of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 278, 44735–44744, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12930841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balleza D, Alessandrini A, Beltran Garcia MJ, 2019. Role of Lipid Composition, Physicochemical Interactions, and Membrane Mechanics in the Molecular Actions of Microbial Cyclic Lipopeptides. J Membr Biol 252, 131–157, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31098678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beavis AD, 1992. Properties of the inner membrane anion channel in intact mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr 24, 77–90, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1380509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beavis AD, Brannan RD, Garlid KD, 1985. Swelling and contraction of the mitochondrial matrix. I. A structural interpretation of the relationship between light scattering and matrix volume. J Biol Chem 260, 13424–13433, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4055741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beavis AD, Garlid KD, 1987. The mitochondrial inner membrane anion channel. Regulation by divalent cations and protons. J Biol Chem 262, 15085–15093, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2444594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beavis AD, Garlid KD, 1988. Inhibition of the mitochondrial inner membrane anion channel by dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. Evidence for a specific transport pathway. J Biol Chem 263, 7574–7580, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2453508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beavis AD, Powers M, 2004. Temperature dependence of the mitochondrial inner membrane anion channel: the relationship between temperature and inhibition by magnesium. J Biol Chem 279, 4045–4050, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14615482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beavis AD, Powers MF, 1989. On the regulation of the mitochondrial inner membrane anion channel by magnesium and protons. J Biol Chem 264, 17148–17155, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2477365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beavis AD, Vercesi AE, 1992. Anion uniport in plant mitochondria is mediated by a Mg(2+)-insensitive inner membrane anion channel. J Biol Chem 267, 3079–3087, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1371111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardi P, 2013. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: a mystery solved? Front Physiol 4, 95, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23675351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biary N, Xie C, Kauffman J, Akar FG, 2011. Biophysical properties and functional consequences of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release in intact myocardium. J Physiol 589, 5167–5179, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21825030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borecky J, Jezek P, Siemeni D, 1997. 108-pS Channel in Brown Fat Mitochondria Might Be Identical to the Inner Membrane Anion Channel. J. Biol. Chem 272, 19282–19289, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brelidze TI, Niu X, Magleby KL, 2003. A ring of eight conserved negatively charged amino acids doubles the conductance of BK channels and prevents inward rectification. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9027–9022, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brierley GP, Jurkowitz M, Scott KM, Merola AJ, 1970. Ion transport by heart mitochondria. XX. Factors affecting passive osmotic swelling of isolated mitochondria. J Biol Chem 245, 5404–5411, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5469174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brierley GP, Jurkowitz MS, Farooqui T, Jung DW, 1984. K+/H+ antiport in heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem 259, 14672–14678, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6438102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavalheiro RA, Fortes F, Borecky J, Faustinoni VC, Schreiber AZ, Vercesi AE, 2004. Respiration, oxidative phosphorylation, and uncoupling protein in Candida albicans. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res 37, 1455–1461, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP, 2006. Inhibition of Candida parapsilosis mitochondrial respiratory pathways enhances susceptibility to caspofungin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 50, 744–747, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16436735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen YC, Lu JW, Yeh CT, Lin TY, Liu FC, Ho YJ, 2021. Micafungin Inhibits Dengue Virus Infection through the Disruption of Virus Binding, Entry, and Stability. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 14, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33917182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corry B, Chung SH, 2006. Mechanisms of valence selectivity in biological ion channels. Cell Mol Life Sci 63, 301–315, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16389453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dagley MJ, Gentle IE, Beilharz TH, Pettolino FA, Djordjevic JT, Lo TL, Uwamahoro N, Rupasinghe T, Tull DL, McConville M, Beaurepaire C, Nantel A, Lithgow T, Mitchell AP, Traven A, 2011. Cell wall integrity is linked to mitochondria and phospholipid homeostasis in Candida albicans through the activity of the post-transcriptional regulator Ccr4-Pop2. Molecular microbiology 79, 968–989, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21299651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fahlke C, 2001. Ion permeation and selectivity in ClC-type chloride channels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280, F748–757, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11292616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez-Salas E, Sagar M, Cheng C, Yuspa SH, Weinberg WC, 1999. p53 and tumor necrosis factor alpha regulate the expression of a mitochondrial chloride channel protein. J Biol Chem 274, 36488–36497, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10593946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujie A, 2007. Discovery of micafungin (FK463): A novel antifungal drug derived from a natural product lead. Pure Appl. Chem 79, 603–614, [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Effron G, Lee S, Park S, Cleary JD, Perlin DS, 2009. Effect of Candida glabrata FKS1 and FKS2 mutations on echinocandin sensitivity and kinetics of 1,3-b-D-glucan synthase: implication for the existing susceptibility breakpoint. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 53, 3690–3699, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19546367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Rubio R, Jimenez-Ortigosa C, DeGregorio L, Quinteros C, Shor E, Perlin DS, 2021. Multifactorial Role of Mitochondria in Echinocandin Tolerance Revealed by Transcriptome Analysis of Drug-Tolerant Cells. mBio 12, e0195921, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34372698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garlid KD, Beavis AD, 1985. Swelling and contraction of the mitochondrial matrix. II. Quantitative application of the light scattering technique to solute transport across the inner membrane. J Biol Chem 260, 13434–13441, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4055742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garlid KD, Beavis AD, 1986. Evidence for the existence of an inner membrane anion channel in mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 853, 187–204, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2441746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garlid KD, DiResta DJ, Beavis AD, Martin WH, 1986. On the mechanism by which dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and quinine inhibit K+ transport in rat liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem 261, 1529–1535, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3944099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE, Didelot C, Kroemer G, 2006. Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 13, 1423–1433, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16676004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geudens N, Martins JC, 2018. Cyclic Lipodepsipeptides From Pseudomonas spp. - Biological Swiss-Army Knives. Front Microbiol 9, 1867, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30158910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, 2006. Multiple pathways of cytochrome c release from mitochondria in apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1757, 639–647, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16678785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hackenbrock CR, 1966. Ultrastructural Bases for Metabolically Linked Mechanical Activity in Mitochondria I. Reversible Ultrastructural Changes with Change in Metaboloically Steady State in Isolated Liver Mitochondria. J. Cell Biol 30, 269–297, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halestrap AP, Pasdois P, 2009. The role of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in heart disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787, 1402–1415, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19168026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harnois I, Maget-Dana R, Ptak M, 1989. Methylation of the antifungal lipopeptide iturin A modifies its interaction with lipids. Biochimie 71, 111–116, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashimi H, McDonald L, Stribrna E, Lukes J, 2013. Trypanosome Letm1 protein is essential for mitochondrial potassium homeostasis. J Biol Chem 288, 26914–26925, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23893410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasim S, Coleman JJ, 2019. Targeting the fungal cell wall: current therapies and implications for development of alternative antifungal agents. Future Med. Chem 11, 869–883, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heerklotz H, Seelig J, 2007. Leakage and lysis of lipid membranes induced by the Lipopeptide surfactin. Eur Biophys J 36, 305–314, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17051366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huttel W, 2021. Echinocandins: structural diversity, biosynthesis, and development of antimycotics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105, 55–66, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33270153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ines M, Dhouha G, 2015. Lipopeptide surfactants: Production, recovery and pore forming capacity. Peptides 71, 100–112, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26189973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Izzo V, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Sica V, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, 2016. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition: New Findings and Persisting Uncertainties. Trends Cell Biol 26, 655–667, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27161573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jahn SC, Rowland-Faux L, Stacpoole PW, James MO, 2015. Chloride concentrations in human hepatic cytosol and mitochondria are a function of age. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 459, 463–468, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25748576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keramidas A, Moorhouse AJ, Schofield PR, Barry PH, 2004. Ligand-gated ion channels: mechanisms underlying ion selectivity. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 86, 161–204, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15288758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ko YT, Ludescher RD, Frost DJ, Wasserman BP, 1994. Use of cilofungin as direct fluorescent probe for monitoring antifungal drug-membrane interaction. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 38, 1378–1385, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koch C, Uhle F, Wolff M, Arens C, Schulte A, Li L, Niemann B, Henrich M, Rohrbach S, Weigand MA, Lichtenstern C, 2015. Cardiac effects of echinocandins after central venous administration in adult rats. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 59, 1612–1619, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25547351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kofla G, Ruhnke M, 2011. Pharmacology and metabolism of anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin in the treatment of invasive candidosis: Review of the literature. European journal of medical research 16, 159–166, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurtz MB, Douglas C, Marrinan J, Nollstadt K, Onishi J, Dreikorn S, Milligan J, Mandala S, Thompson J, Balkovec JM, et al. , 1994. Increased antifungal activity of L-733,560, a water-soluble, semisynthetic pneumocandin, is due to enhanced inhibition of cell wall synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 38, 2750–2757, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7695257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurtz MB, Douglas CM, 1997. Lipopeptide inhibitors of fungal glucan synthase. J. Med. Vet. Mycol 35, 79–86, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laskowski M, Augustynek B, Kulawiak B, Koprowski P, Bednarczyk P, Jarmuszkiewicz W, Szewczyk A, 2016. What do we not know about mitochondrial potassium channels? Biochim Biophys Acta 1857, 1247–1257, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26951942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li T, Brustovetsky T, Antonsson B, Brustovetsky N, 2008. Oligomeric BAX induces mitochondrial permeability transition and complete cytochrome c release without oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777, 1409–1421, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18771651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Littler DR, Harrop SJ, Goodchild SC, Phang JM, Mynott AV, Jiang L, Valenzuela SM, Mazzanti M, Brown LJ, Breit SN, Curmi PM, 2010. The enigma of the CLIC proteins: Ion channels, redox proteins, enzymes, scaffolding proteins? FEBS Lett 584, 2093–2101, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20085760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mackova K, Misak A, Tomaskova Z, 2018. Lifting the Fog over Mitochondrial Chloride Channels, Ion Channels in Health and Sickness

- 54.Maget-Dana R, Peypoux F, 1994. Iturins, a special class of pore-forming lipopeptides: biological and physiochemical properties. Toxicology 87, 151–174, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Misak A, Grman M, Malekova L, Novotova M, Markova J, Krizanova O, Ondrias K, Tomaskova Z, 2013. Mitochondrial chloride channels: electrophysiological characterization and pH induction of channel pore dilation. Eur Biophys J 42, 709–720, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23903554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore C, Pressman BC, 1964. Mechanism of action of valinomycin on mitochondria. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 15, 562–567, [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morris MI, Villmann M, 2006. Echinocandins in the management of invasive fungal infections, Part 2. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists 63, 1813–1820, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16990627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakashima R, Garlid KD, 1982. Quinine inhibition of Na+ and K+ transport provides evidence for two cation/H+ exchangers in rat liver mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem 257, 9252–9254, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishikimi A, Kira Y, Kasahara E, Sato E, Kanno T, K U, Inoue M, 2001. Tributyltin interacts with mitochondria and induces cytochrome c release. Biochem J. 356, 621–626, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nowikovsky K, Schweyen RJ, Bernardi P, 2009. Pathophysiology of mitochondrial volume homeostasis: potassium transport and permeability transition. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787, 345–350, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19007745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Toole JF, Patel HV, Naples CJ, Fujioka H, Hoppel CL, 2010. Decreased cytochrome c mediates an age-related decline of oxidative phosphorylation in rat kidney mitochondria. Biochem J 427, 105–112, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20100174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oettinghaus B, Frank S, Scorrano L, 2011. Tonight, the same old, deadly programme: BH3-only proteins, mitochondria and yeast. EMBO J 30, 2754–2756, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21772325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oftedal L, Myhren L, Jokela J, Gausdal G, Sivonen K, Doskeland SO, Herfindal L, 2012. The lipopeptide toxins anabaenolysin A and B target biological membranes in a cholesterol-dependent manner. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818, 3000–3009, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22842546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]