Abstract

Background.

Implanted vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), when synchronized with post-stroke motor rehabilitation improves conventional motor rehabilitation training. A non-invasive VNS method known as transcutaneous auricular vagus nerves stimulation (taVNS) has emerged, which may mimic the effects of implanted VNS.

Objective.

To determine whether taVNS paired with motor rehabilitation improves post-stroke motor function, and whether synchronization with movement and amount of stimulation is critical to outcomes.

Methods.

We developed a closed-loop taVNS system for motor rehabilitation called motor activated auricular vagus nerve stimulation (MAAVNS) and conducted a randomized, double-blind, pilot trial investigating the use of MAAVNS to improve upper limb function in 20 stroke survivors. Participants attended 12 rehabilitation sessions over 4-weeks, and were assigned to a group that received either MAAVNS or active unpaired taVNS concurrently with task-specific training. Motor assessments were conducted at baseline, and weekly during rehabilitation training. Stimulation pulses were counted for both groups.

Results.

A total of 16 individuals completed the trial, and both MAAVNS (n = 9) and unpaired taVNS (n = 7) demonstrated improved Fugl-Meyer Assessment upper extremity scores (Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 5.00 ± 1.02, unpaired taVNS: 3.14 ± 0.63). MAAVNS demonstrated greater effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.63) compared to unpaired taVNS (Cohen’s d = 0.30). Furthermore, MAAVNS participants received significantly fewer stimulation pulses (Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 36 070 ± 3205) than the fixed 45 000 pulses unpaired taVNS participants received (P < .05).

Conclusion.

This trial suggests stimulation timing likely matters, and that pairing taVNS with movements may be superior to an unpaired approach. Additionally, MAAVNS effect size is comparable to that of the implanted VNS approach.

Keywords: transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, taVNS, motor rehabilitation, stroke, motor activated auricular vagus nerve stimulation, MAAVNS, tVNS

Introduction

More than 795 000 individuals in the United States have a stroke annually,1 with 85% of these stroke cases resulting in significant deficits in upper extremity function2,3 causing reduced quality of life and long term impairment. The most effective approach to addressing these functional deficits is through therapist administered post-stroke motor rehabilitation training.4,5 Conventional motor rehabilitation involves consistent and repetitive task-related movements, which improve motor learning and help restore motor function.6 Although task-specific training (TST) improves motor function, not all patients receive satisfactory outcomes, and deficits can still remain even with satisfactory outcomes. Thus, adjuncts have been explored to improve motor rehabilitation outcomes, including brain stimulation to potentiate neuroplasticity.7,8

An exciting adjunct to motor rehabilitation is vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), which has been demonstrated to increase neuroplasticity and accelerate the restoration of neural activity in both animal models9,10 and in human clinical trials.11 VNS is an implanted form of neuromodulation that utilizes a cuff electrode to deliver electricity to the vagus nerve, in turn activating neurocircuitry involved in neuroplastic mechanisms underlying motor learning.12,13 Recently, it was demonstrated that VNS, when temporally synchronized with motor rehabilitation training, boosts motor learning.11,14 When applied in the post-stroke rehabilitation setting, this paired-VNS approach nearly doubles the behavioral effects of conventional motor rehabilitation training,15 increasing the effectiveness of motor training alone. Subsequently, VNS became the first neuromodulation approach to be FDA-approved for post-stroke motor rehabilitation with a paradigm that temporally synchronizes VNS with motor repetitions during motor rehabilitation to boost the effects of motor training.

Although VNS is generally safe, risks involved in surgical implantation, as well as high procedural cost ($30 000-$50 000) makes it less appealing and limits its overall uptake by patients. A non-invasive method to stimulate the vagus has recently emerged, known as transcutaneous auricular vagus nerves stimulation (taVNS).16 Modern taVNS was described in 2000,17 and utilizes surface electrodes applied to specific anatomical landmarks in the ear to activate underlying nerves. Several well-controlled mechanistic neuroimaging studies18–22 have demonstrated that taVNS may mimic the afferent effects of cervically implanted VNS, inducing blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal changes in similar brain regions.23,24 taVNS is an exciting, new form of neuromodulation that has many advantages over cervically implanted devices, including cost (<$1000 vs $30 000), noninvasiveness (adhesive electrodes vs surgical implantation), and ability for self-administration with minimal training. However, in head-to-head comparision of taVNS versus implanted VNS suggests taVNS may not be as effective in activating vagus-related biomarkers.25 The underlying mechanism taVNS is still not understood, with considerations like ear target26 and parameters13 that optimally activate vagal afferents and efferents actively being researched.

One question that remains unanswered is whether taVNS can facilitate motor learning in post-stroke motor rehabilitation, in a manner similar to implanted VNS. If so, more patients may have access to the beneficial effects of VNS without surgical implantation. Thus, we conducted a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial investigating (1) the use of a novel closed-loop taVNS system that precisely pairs motor rehabilitation movements with stimulation to improve upper extremity motor function in stroke survivors with unilateral motor deficits, and (2) whether timing of stimulation matters by comparing MAAVNS to an active unpaired taVNS control.

Methods

Study Overview

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, pilot trial exploring the effects of motor activated auricular vagus nerve stimulation (MAAVNS) paired with motor rehabilitation to improve upper limb functional deficits post-stroke. This pilot trial was designed to validate MAAVNS technology and understand it’s effect size and the potential implications of precise timing of stimulation during motor rehabilitation. Chronic stroke participants were randomized to receive either MAAVNS or active unpaired taVNS delivered concurrently for 12 TST motor rehabilitation sessions spread over 4 weeks. All participants signed written informed consent prior to the implementation of study procedures. This study was approved by the MUSC Institutional Review Board (IRB) and is registered on ClinicalTrials.org (NCT04129242).

Participants and Inclusion Criteria

After determining eligibility and interest, and baseline screening measures assessments were conducted, including an in-person motor assessment by an experienced, trained, and licensed occupational therapist to verify motor function that warrants inclusion into the study.

Subjects met the following criteria to participate in this study: 18 to 80 years old with an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke that occurred at least 6 months prior; had completed any prior conventional rehabilitation therapy at least 1 month before enrollment; Unilateral hemiparesis with Fugl-Meyer-Upper Extremity Scale score less than or equal to 58 (The 66-point scale was use for screening, however the 60-point scale was used for all outcome assessment); must have active wrist flexion/extension (approximately 3°) and active abduction/extension of thumb (pinch). The exclusion criteria were: Primary intracerebral hematoma, or subarachnoid hemorrhage; Other concomitant neurological disorders affecting upper extremity motor function; Documented history of dementia before or after stroke; Documented history of uncontrolled depression or psychiatric disorder either before or after stroke which could affect their ability to participate in the experiment; Uncontrolled hypertension despite treatment, specifically SBP/DBP ≥ 180/100 mmHg at baseline; Contraindicated for MRI scanning.

Motor Activated Auricular VNS

We developed a novel neurostimulation system that combines electromyography (EMG) and taVNS to create a closed-loop system used for motor rehabilitation (Figure 1).27 This system, known as MAAVNS, allows for the precise pairing of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) with motor rehabilitation movements (<100 ms), reducing the need for a trained provider to constantly monitor movement and trigger the stimulation manually as is conventionally conducted in the open-loop, invasive VNS for rehabilitation application.15

Figure 1.

Overview of MAAVNS setup and triggering schematic. The closed-loop MAAVNS system uses (A) EMG sensors placed on the anterior deltoid to detect movement. When movement occurs, (B) stimulation is delivered to both left and right ears using adhesive hydrogel electrodes. (C) Therapists can conduct motor rehabilitation training with participants without interacting with the closed-loop automated system. (D) MAAVNS utilizes custom circuitry that detects real-time EMG signals and converts them to stimulation at specific thresholds of amplitude.

This completely analog, closed-loop system detects movement by using surface EMG sensors placed on the anterior and middle deltoid of the participant. After the EMG system detects muscle activity, the EMG signal is sent to an amplifier where it is amplified, and then quickly rectified and integrated into a smooth curve using custom modular circuitry (Digitimer, LTD). This now smoothed EMG signal serves as the “real-time movement detector” and will generate a signal (TTL signal) to activate the electrical nerve stimulator (Digitimer DS7A) when the voltage surpasses a certain “activation threshold” which is pre-set and individualized to each participant. The threshold is set at the first day of therapy and stays stable throughout the treatment course. When movement is detected, the electrical nerve stimulator delivers low levels of electricity (1–3 mA) bilaterally to the left and right ears of participants at 2 specific targets (cymba conchae and tragus) pulsed at 25 Hz for a 5 second train. This stimulation occurs within 100 ms of a detected movement. If movement continues past 5 seconds, the system detects continuous movement and continues to deliver stimulation in 5 second increments until the movement is complete. We have included a video demonstration of the MAAVNS system and entire participant setup in the Supplemental Material.

Unpaired taVNS Control Stimulation and Blinding

To understand whether timing is critical to the therapeutic effects of taVNS, this study employed an unpaired taVNS active condition which delivered active taVNS that was not deliberately paired with movement. Participants randomized to this “unpaired taVNS” group still received identical stimulation parameters (500 μs pulse width, 25 Hz, 2× Perception) as the MAAVNS condition delivered to the same active ear targets with similar train length (5 seconds), however rather than paired with movement, the unpaired taVNS stimulation was delivered tonically for 60 minutes at a 50% duty cycle (5 seconds ON, 5 seconds OFF, 45 000 total pulses).

Both the therapist and the participant were blinded to the group assignment. Research staff connected all participants to the MAAVNS system and conducted baseline EMG calibration in front of the occupational therapist. However, unbeknownst to the participant or therapist, the motiontriggering circuit has been replaced with an automated script that drove stimulation at the pre-specified unpaired taVNS duty cycle. No therapist was trained on, or administered any of the taVNS or EMG methods. Because of the EMG calibration, and that electrodes are placed on active sites (delivering active stimulation) in both groups with identical ear sensation, it is difficult to determine whether closed- or open-loop stimulation is being delivered as only a trained research staff member would know which hardware component controls the randomization.

Task Specific Training

We utilized task specific training (TST) as the therapeutic motor rehabilitation intervention. TST is a is a form of motor rehabilitation that emphasizes intense, targeted motor training of the affected upper limb in post-stroke hemiplegia.5,28–32 TST was administered by 3 trained, experienced, licensed occupational therapists (OT). The distribution of assigned intervention group for each therapist was random, as the randomization was created before the trial began. Therapist 1 delivered therapy for subjects 1 to 5 (2 unpaired and 3 paired), therapist 2 delivered therapy for subjects 6 to 10 (2 unpaired and 3 paired), and therapist 3 delivered therapy for subjects 11 to 20 (6 unpaired and 4 paired).

During TST, subjects repetitively practice ~200 targeted motions of the course of approximately 1 to 1.5 hours. per session by using the affected limb to accomplish functional tasks. Each task was chosen from a task manual through a patient-therapist collaborative standardized task-planning process to assure that each task is motivating to the patient and requires the targeted motions identified by the OT.33 As per TST protocol, the tasks practiced during each session increase in difficulty as subjects gain skill, that is, can complete sets of task practice with ≥80% success rate.

Subjects completed a total of 12 TST sessions (3 sessions/per week for 4 weeks) and received their assigned stimulation condition (MAANVS or unpaired taVNS) during each of those sessions. To assure optimal movement quality during each repetition of a task (ie, to avoid reinforcing movement compensations), the OT made tasks more/less difficult within a session by altering aspects of task performance.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure of this trial was the FuglMeyer Upper Extremity Assessment (FMA-UE).34 The FMA-UE is a 33-item measure of UE impairment; however, the 3 items testing reflex response were not administered because they do not measure a voluntary movement construct.35 Each item is scored on a 3-point rating scale (0 = unable, 1 = partial, and 2 = near normal performance), and item ratings are summed and reported out of 60 points so that larger numbers indicated greater UE motor ability. The secondary outcome was the Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT)36 which is a 15-item measure of UE functional ability. Both the FMA-UE and the WMFT are administered by a blinded therapist (blinded to the condition of stimulation) at baseline, at completion of session 3, 6, 9, and 12, as well as at 2- and 8-week follow up. There were 2 assessors, both of which were therapists in the trial. Therapist 2—assessed subjects 1 to 5 blindly using camera (2 unpaired and 3 paired) and assessed subjects 11 to 20 in person (6 unpaired and 4 paired). Therapist 3—assessed subjects 6 to 10 in person (2 unpaired and 3 paired)

Each subject was scored at each time point by the same therapist (ie, one therapist assessed one subject throughout all timepoints).

Additionally, because this was a pilot trial, and to compare outcomes to other prior implanted and noninvasive VNS trials in stroke recovery, we estimated the Cohen’s d effect size for the FMA-UE in both the MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS groups using methods previously described in Redgrave et al’s37 poststroke pilot study.

Lastly, to compare whether MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS deliver similar amounts of stimulation each session, we collected stimulation pulse data (total number of electrical pulses) of taVNS delivered per session.

Statistical Methods

To investigate the differences in FMA-UE and WMFT scores between MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS groups, a linear mixed-effects (LME) ANOVA was performed to examine the effects of time and stimulation condition. Furthermore, post hoc comparisons were conducted using a 2 sample t-test investigating motor function improvements after session 12 compared to baseline. Additionally, we conducted a 2-sample t-test comparing the mean total number of stimulation pulses delivered per session between MAAVNS and the unpaired taVNS group, as well as the mean total activity repetitions practiced in each session.

Results

This clinical trial began recruitment in Charleston, South Carolina November 5th, 2020, and completed October 5th, 2022, and an overview of trial participant enrollment is presented in Figure 2. Twenty-one participants were screened for eligibility, and 1 participant failed screening due to orthopedic restriction of the upper extremity. A total of 20 participants were enrolled and randomized into either MAAVNS (n = 10) or unpaired taVNS (n = 10) stimulation conditions. Within the MAAVNS group, 1 participant failed to complete the trial and was excluded from any analysis. Within the unpaired taVNS group, 3 participants were excluded from any analysis for the following reasons: (1) failed video recording of baseline assessments, (2) significant life event causing drop out from trial, and (3) mid-trial withdrawal by study occupational therapist due to confounding pain impairments unrelated to stimulation or motor rehabilitation.

Figure 2.

Consort flow diagram.

Participants were well balanced between groups, with similar ages (Mean ± SD, MAAVNS 57.33 ± 8.28 years, unpaired taVNS, 58.71 ± 6.45 years, P = .72) and nonsignificantly different baseline FMA-UE (Mean ± SD, MAAVNS 36.56 ± 7.94, unpaired taVNS, 38.57 ± 10.47, P = .66) and WMFT (Mean ± SD, MAAVNS 42.22 ± 12.49, unpaired taVNS, 44.57 ± 8.36, P = .67) scores. Complete characteristics of participants can be found in Table I.

Table I.

Demographic Information and Clinical Characteristics.

| MAAVNS (n = 9) | Unpaired taVNS (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.33 (8.28) | 58.71 (6.45) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4 (44%) | 5 (71%) |

| Female | 5 (56%) | 2 (29%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 5 (56%) | 4 (57%) |

| African American | 3 (33%) | 3 (43%) |

| Asian, Indian, or other | 1 (1 1%) | 0 |

| Time since stroke, years | 3.22(3.14) | 4.51 (3.93) |

| Handedness | ||

| Right | 9 (100%) | 5 (71%) |

| Left | 0 | 2 (29%) |

| Side of paresis | ||

| Right | 4 (44%) | 4 (57%) |

| Left | 5 (56%) | 3 (43%) |

| FMA-UE baseline score | 36.56 (7.94) | 38.57 (10.47) |

| WMFT baseline score | 42.22(12.49) | 44.57 (8.36) |

Abbreviations: FMA-UE, Fugl-Meyer assessment-upper extremity; WMFT, Wolf motor function test.

Data are n (%) or mean (SD).

Safety, Tolerability, and Stimulation Intensity

Stimulation and rehabilitation were safe, as both MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS groups tolerated the intervention well, with no adverse events reported. Additionally, all attended sessions were completed with no vital sign changes that disrupted therapy.

All participants received bilateral ear stimulation at 2× their perceptual threshold (PT). PTs vary by individual ear sensitivity and were not significantly different by stimulation condition (Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 1.43 ± 0.17, unpaired taVNS 1.74 ± 0.29, P = .35).

Motor Function Outcomes

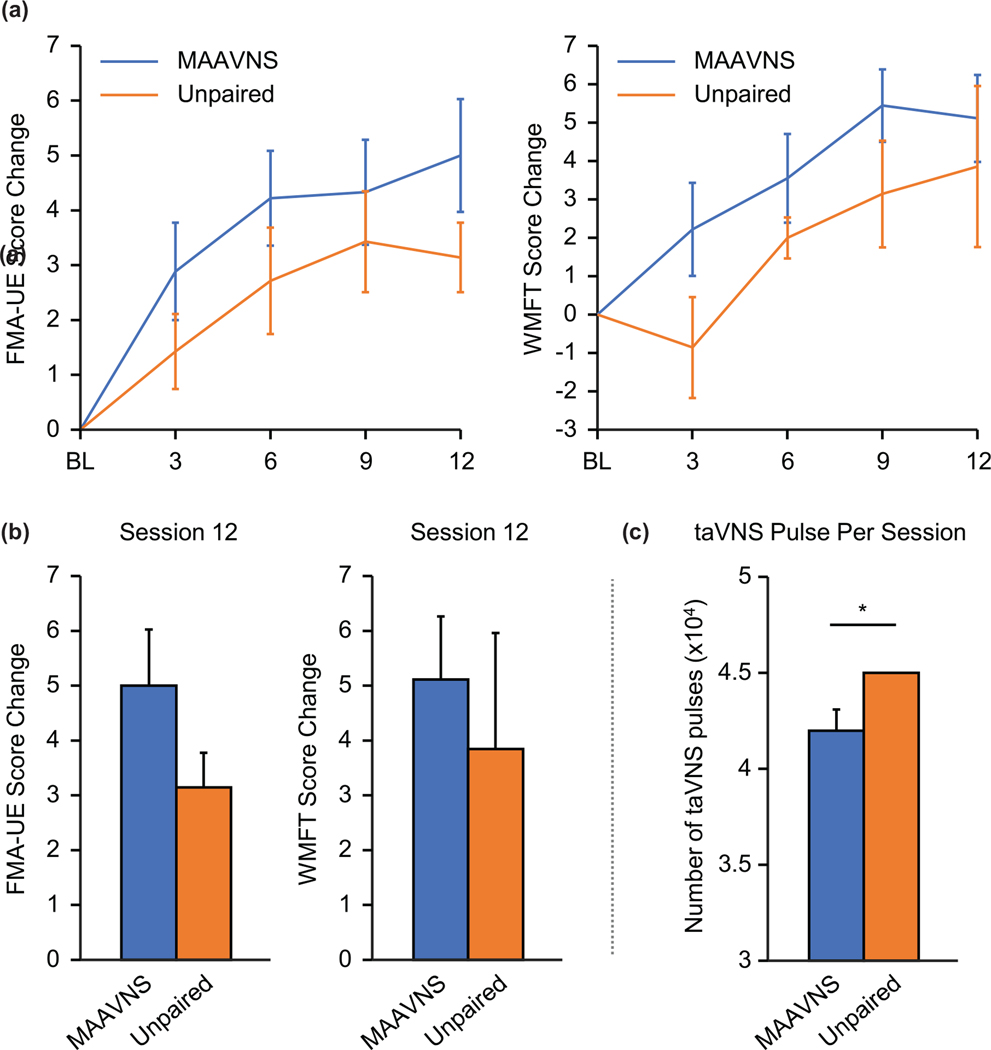

Compared to baseline, both MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS groups demonstrate significant motor function improvement indicated by the FMA-UE (2-way ANOVA: F1,60 = 10.49, P = .002) and the WMFT (F1,60 = 5.10, P = .028) over the course of rehabilitation training (Figure 3A). However, there were no significant difference between stimulation conditions. Although the primary finding is there is no significant difference between groups, post-hoc analysis on the change from baseline to after session 12 suggests MAAVNS may be more effective in improving motor function (FMA-UE: Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 5.00 ± 1.02, unpaired taVNS: 3.14 ± 0.63; WMFT: Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 5.11 ± 1.14, unpaired taVNS: 3.86 ± 2.10; Figure 3B). Furthermore, MAAVNS demonstrated a larger effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.63) compared to the unpaired taVNS group (Cohen’s d = 0.30).

Figure 3.

Overall, MAAVNS may produce more robust effects with less pulses delivered. (A) Primary (Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Upper Extremity, FMA-UE) and secondary (Wolf Motor Function Task, WMFT) motor outcomes of the MAAVNS and Unpaired taVNS are demonstrated. Overall significant effects of time were demonstrated in both MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS groups FMA-UE (2-way ANOVA: F1,60 = 10.49, P = .002) and the WMFT (F1,60 = 5.10, P = .028). (B) From baseline to post-session 12, MAAVNS group demonstrates greater improvement in the mean FMA-UE change scores (Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 5.00 ± 1.02, unpaired taVNS: 3.14 ±0.63). Similar trends appear in the WMFT scores (Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 5.11 ± 1.14, unpaired taVNS: 3.86 ± 2.10). (C) The MAAVNS group received significantly less total electrical stimulation pulses (Mean ± SEM, 36 070 ±3205) than the unpaired taVNS condition which received a fixed 45 000 pulses during each session (P = .03).

Rehabilitation Repetitions and Number of Pulses Delivered

Both MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS groups completed similar number of activity repetitions during each TST session (Mean ± SEM, MAAVNS: 204.71 ± 7.52 reps, unpaired taVNS: 206.06 ± 16.10, P = .94), however the MAAVNS group received significantly less total electrical stimulation pulses (Mean ± SEM, 36 070 ± 3205) than the unpaired taVNS condition which received a fixed 45 000 pulses during each session (P = .03; Figure 3C).

Discussion

We developed a closed-loop system designed to deliver transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) at the same time as repetitive movements occurring during post-stroke motor rehabilitation. This system, called motor activated auricular vagus nerve stimulation (MAAVNS) was then used in a prospective, randomized, double blind trial in individuals with unilateral upper limb functional motor deficits to gather initial effect size and whether timing the stimulation with the trained movement improves outcomes compared to an unintelligent, unpaired taVNS approach. Our findings suggest that pairing stimulation with movement may be benefical in improving timing of stimulation, potentially making a more efficient treatment, as even though the MAAVNS group received significantly less stimulation overall, the effect size of the MAAVNS group was double that of the unpaired taVNS group.

Although our trial did not employ a true sham, our findings demonstrate a trend that closed-loop MAAVNS may outperform active unpaired taVNS in this pilot trial, suggesting timing may be critical to effects. Interestingly, our findings suggest that the improvement of the MAAVNS FMA-UE score is comparable in absolute improvement and effect size to the recently FDA-approved implanted VNS trial—despite MAAVNS receiving two thirds fewer sessions. Our findings demonstrate that 12 sessions of MAAVNS therapy improves group mean (±SD) FMA-UE scores by 5 ± 3.06, with a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.62. The 18 sessions of implanted VNS trial15 reveals group mean (±SD) improvements FMA-UE scores by 5 ± 4.4 with a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.60. In the implanted VNS trial by Dawson and colleagues, they randomized 108 stroke survivors (53 active VNS, 55 control) into the largest VNS rehabilitation trial to date, exploring the effects of 18 sessions of VNS-paired motor rehabilitation. Their findings demonstrate that active implanted VNS, when manually triggered by a therapist during movements, significantly improves motor function compared to sham VNS. Implanted VNS doubles the effects of conventional motor rehabilitation when specifically timed with movement. In light of this trial, our findings are promising, as it suggests that in our small cohort, 12 sessions of MAAVNS therapy, on average, provides a similar mean level of improvement as 18 sessions of implanted VNS.

This trial is what we believe to be a first report of a closed loop motor activated taVNS generated by individualized bio signals to self-administer taVNS, there have been 3 prior small trials utilizing taVNS to boost outcomes of upper limb motor rehabilitation. A small pilot study by Redgrave et al37 administered taVNS to 13 individuals undergoing upper limb motor rehabilitation with promising results. This trial required a therapist to press a button on the taVNS device to turn on and off stimulation during movement, and although their study conducted 18 rehabilitation sessions each with 300 repetitions, rather than our 12 sessions and 200 repetitions per session, the results demonstrate a large improvement FMA-UE (Cohens d = 0.68). Wu and colleagues conducted another trial utilizing taVNS in a 15 consecutive day paradigm, during which taVNS was administered immediately before motor rehabilitation. A total of 21 patients were randomized into either active- or sham-taVNS and findings reveal greater mean improvements in FMA-UE in the active group compared to sham (6.9 vs 3.18).38 Lastly, Capone and colleagues combined taVNS with robotic rehabilitation in 14 patients and demonstrated that active taVNS improved FMA-UE scores by 5.4 points, whereas the sham group improved by 2.8 points.39 Thus, there is growing evidence suggesting that taVNS may be beneficial in upper extremity motor rehabilitation.

There is clear importance in having an individualized, closed loop therapy when considering VNS approaches for rehabilitation post-stroke, as our findings suggest that with less overall stimulation, timed accurately, MAAVNS can provide larger motor function benefit than Unpaired taVNS stimulation. Implanted VNS activates the brain’s primary source of norepinephrine (locus coeruleus) which results in broad downstream neuroplastic cellular effects. Lesioning the LC dissipates the clinical efficacy of VNS and inhibits this noradrenergic-driven neuroplasticity.40–42 VNS is an influencer of neural plasticity and has been paired with various forms of training in animal models to restore deficient or aberrant neural activity.10,43,44,45 Most notably, rats with implanted VNS electrodes were concurrently stimulated while receiving rehabilitative training post-ischemic stroke induction. About 100% of the rats receiving the paired intervention fully recovered forelimb function compared to 22% of rats in the control condition.10,43 Cortical reorganization in the VNS group restored pathologically inactive circuits and these findings demonstrate that VNS and motor training have synergistic impacts on network plasticity and can be combined to rapidly accelerate cortical reorganization in the motor cortex after brain injury. This timing is critical, as Khodaparast et al43 demonstrate that pairing VNS within 70 ms of movement improves outcomes. Hays et al46 demonstrated that not only does the timing need to be synchronized with movement to maximize effects poststroke (within 290 ms), when too much stimulation is delivered (extra VNS), this neuroplastic effect is significantly reduced.

Limitations

Although this pilot trial was not designed or powered to determine efficacy between MAAVNS and unpaired taVNS, a limitation of this study is the small sample size. With 9 participants in the MAAVNS group and 7 in the unpaired taVNS group, we failed to find significant differences between both stimulation groups. Given the prior literature exploring taVNS for post-stroke rehabilitation, it has been demonstrated that adding taVNS to motor rehabilitation alone may provide benefit over the standard of care, however, to determine whether MAAVNS outperforms unpaired taVNS, given the effect sizes, we would need to enroll 97 patients. Furthermore, our study did not utilize a true sham-control condition. Both groups received active stimulation, making it difficult to understand the true impact of these findings. Also, comparing our outcomes to historical data is less than ideal when a rehabilitation trial utilizes a different paradigm, varying total repetitions, rehabilitation approach, and number of sessions. Lastly, we did not control for stroke type, lesion laterality or size of lesion. Due to the heterogeneity of the population, it may be that some individuals may have not responded to therapy due to the extent of brain injury presented.

Conclusions

MAAVNS is a promising new technology that has the potential to be a cost effective, noninvasive, and scalable technology that may provide improvement to stroke survivors with motor function deficits. Future trials should explore extending rehabilitation course from 4- to 6- weeks, as well as employ a true sham control to understand the definitive effects of MAAVNS therapy. Additionally, as a platform technology, MAAVNS should be explored for other motor rehabilitation, such as spinal cord and lower extremity recovery.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this project was provided by: COBRE P20 GM109040 (PI Kautz, Project 4 PI Badran) and COCA (5P50DA046373). SAK was funded in part by IK6RX003075.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: BWB is the named lead inventor of a patent on methods described in this manuscript which has been assigned to the Medical University of South Carolina.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

All other authors have no conflicts to report.

Supplementary material for this article is available on the Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair website along with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153–e639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobkin BH. Strategies for stroke rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(9):528–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang CE, Macdonald JR, Reisman DS, et al. Observation of amounts of movement practice provided during stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(10):1692–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang CE, Strube MJ, Bland MD, et al. Dose response of task-specific upper limb training in people at least 6 months post-stroke: a phase II, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(3):342–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubbard IJ, Parsons MW, Neilson C, Carey LM. Task-specific training: evidence for and translation to clinical practice. Occup Ther Int. 2009;16(3–4):175–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster BR, Celnik PA, Cohen LG. Noninvasive brain stimulation in stroke rehabilitation. NeuroRx. 2006;3(4):474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowak DA, Grefkes C, Ameli M, Fink GR. Interhemispheric competition after stroke: brain stimulation to enhance recovery of function of the affected hand. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23(7):641–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hays SA, Rennaker RL, Kilgard MP. Targeting plasticity with vagus nerve stimulation to treat neurological disease. Prog Brain Res. 2013;207:275–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khodaparast N, Hays SA, Sloan AM, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation during rehabilitative training improves forelimb strength following ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;60:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimberley TJ, Pierce D, Prudente CN, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation paired with upper limb rehabilitation after chronic stroke. Stroke. 2018;49(11):2789–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austelle CW, O’Leary GH, Thompson S, et al. A comprehensive review of vagus nerve stimulation for depression. Neuromodulation. 2021;25:309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson SL, O’Leary GH, Austelle CW, et al. A review of parameter settings for invasive and non-invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) applied in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:709436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson J, Pierce D, Dixit A, et al. Safety, feasibility, and efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation paired with upper-limb rehabilitation after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2016;47(1):143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson J, Liu CY, Francisco GE, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation paired with rehabilitation for upper limb motor function after ischaemic stroke (VNS-REHAB): a randomised, blinded, pivotal, device trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10284):1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badran BW, Alfred BY, Adair D, et al. Laboratory administration of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): technique, targeting, and considerations. J Vis Exp. 2019(143):e58984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ventureyra EC. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for partial onset seizure therapy. Child’s Nerv Syst. 2000;16(2):101–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badran BW, Dowdle LT, Mithoefer OJ, et al. Neurophysiologic effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) via electrical stimulation of the tragus: a concurrent taVNS/fMRI study and review. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(3):492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus T, Hösl K, Kiess O, Schanze A, Kornhuber J, Forster C. BOLD fMRI deactivation of limbic and temporal brain structures and mood enhancing effect by transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation. J Neural Transm. 2007;114(11):1485–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich S, Smith J, Scherzinger C, et al. A novel transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation leads to brainstem and cerebral activations measured by functional MRI/Funktionelle Magnetresonanztomographie zeigt Aktivierungen des Hirnstamms und weiterer zerebraler Strukturen unter transkutaner Vagusnervstimulation. Biomed Eng. 2008;53(3):104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yakunina N, Kim SS, Nam EC. Optimization of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation using functional MRI. Neuromodulation. 2017;20:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frangos E, Ellrich J, Komisaruk BR. Non-invasive access to the vagus nerve central projections via electrical stimulation of the external ear: fMRI evidence in humans. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):624–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomarev M, Denslow S, Nahas Z, Chae J-H, George MS, Bohning DE. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) synchronized BOLD fMRI suggests that VNS in depressed adults has frequency/dose dependent effects. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36(4):219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahas Z, Teneback C, Chae JH, et al. Serial vagus nerve stimulation functional MRI in treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(8):1649–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bucksot JE, Morales Castelan K, Skipton SK, Hays SA. Parametric characterization of the rat Hering-Breuer reflex evoked with implanted and non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation. Exp Neurol. 2020;327:113220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badran BW, Brown JC, Dowdle LT, et al. Tragus or cymba conchae? Investigating the anatomical foundation of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS). Brain Stimul. 2018;11(4):947–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook DN, Thompson S, Stomberg-Firestein S, et al. Design and validation of a closed-loop, motor-activated auricular vagus nerve stimulation (MAAVNS) system for neurorehabilitation. Brain Stimul. 2020;13(3):800–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taub E, Miller NE, Novack TA, et al. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74(4):347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camona C, Wilkins KB, Drogos J, Sullivan JE, Dewald JPA, Yao J. Improving hand function of severely impaired chronic hemiparetic stroke individuals using task-specific training with the ReIn-Hand System: a case series. Front Neurol. 2018;9:923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waddell KJ, Birkenmeier RL, Moore JL, Hornby TG, Lang CE. Feasibility of high-repetition, task-specific training for individuals with upper-extremity paresis. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(4):444–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaefer SY, Patterson CB, Lang CE. Transfer of training between distinct motor tasks after stroke: implications for task-specific approaches to upper-extremity neurorehabilitation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(7):602–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birkenmeier RL, Prager EM, Lang CE. Translating animal doses of task-specific training to people with chronic stroke in 1-hour therapy sessions: a proof-of-concept study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(7):620–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodbury ML, Anderson K, Finetto C, et al. Matching task difficulty to patient ability during task practice improves upper extremity motor skill after stroke: a proof-of-concept study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(11):1863–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. A method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7(1):13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woodbury ML, Velozo CA, Richards LG, Duncan PW, Studenski S, Lai SM. Dimensionality and construct validity of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the upper extremity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(6):715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf SL, Lecraw DE, Barton LA, Jann BB. Forced use of hemiplegic upper extremities to reverse the effect of learned nonuse among chronic stroke and head-injured patients. Exp Neurol. 1989;104(2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redgrave JN, Moore L, Oyekunle T, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation with concurrent upper limb repetitive task practice for poststroke motor recovery: a pilot study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(7):1998–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu D, Ma J, Zhang L, Wang S, Tan B, Jia G. Effect and safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on recovery of upper limb motor function in subacute ischemic stroke patients: a randomized pilot study. Neural Plast. 2020;2020:8841752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farmer AD, Strzelczyk A, Finisguerra A, et al. International consensus based review and recommendations for minimum reporting standards in research on transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (Version 2020). Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:568051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meintzschel F, Ziemann U. Modification of practice-dependent plasticity in human motor cortex by neuromodulators. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(8):1106–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawaki L, Werhahn KJ, Barco R, Kopylev L, Cohen LG. Effect of an alpha(1)-adrenergic blocker on plasticity elicited by motor training. Exp Brain Res. 2003;148(4):504–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krahl SE, Clark KB, Smith DC, Browning RA. Locus coeruleus lesions suppress the seizure-attenuating effects of vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsia. 1998;39(7):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khodaparast N, Hays SA, Sloan AM, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation delivered during motor rehabilitation improves recovery in a rat model of stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;28(7):698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porter BA, Khodaparast N, Fayyaz T, et al. Repeatedly pairing vagus nerve stimulation with a movement reorganizes primary motor cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22(10):2365–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shetake JA, Engineer ND, Vrana WA, Wolf JT, Kilgard MP. Pairing tone trains with vagus nerve stimulation induces temporal plasticity in auditory cortex. Exp Neurol. 2012;233(1):342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hays SA, Khodaparast N, Ruiz A, et al. The timing and amount of vagus nerve stimulation during rehabilitative training affect poststroke recovery of forelimb strength. Neuroreport. 2014;25(9):676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.