Abstract

Background

We sought to evaluate changes in ITE scores and associations with clinical work during the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesized that residents saw a decrease in clinical encounters during the pandemic and that this would be associated with smaller gains in ITE score.

Methods

We compared ITE score changes with data on patient notes for three classes of pediatric residents at four residency programs: one not exposed to the pandemic during their intern year who entered residency in 2018, one partially exposed to Covid-19 in March of their intern year (2019-2020), and one that was fully exposed to the pandemic, starting residency in June of 2020.

Results

ITE scores on average improved from the PGY1 to PGY2 year in the “no covid” and “partial covid” cohorts. The “full covid” cohort had little to no improvement, on average. The total number of patient encounters was not associated with a change in ITE scores from PGY1 to PGY2. There was a small but statistically significant association between change in ITE score and number of inpatient H+P notes.

Discussion

A drop in ITE scores occurred in pediatric residents who entered residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. This change was largely unrelated to clinical encounter number changes.

Keywords: in training exam, COVID-19, education, pediatric residency

Introduction

To achieve certification in General Pediatrics, graduates of pediatric residency programs must pass the American Board of Pediatrics certifying examination.1 The In-Training Examination (ITE) is a standardized test utilized to assess resident knowledge and monitor individualized progress in knowledge acquisition during training, and ITE scores have been shown to be predictive of board passage.2 Changes in the educational environment of residency programs during the COVID-19 pandemic may have had effects on numerous aspects of training, including an associated decrease in first time test takers pediatric boards pass rate (91% in 2018 to 81% in 2021).3 At our own institutions, we anecdotally noted a decrease in pediatric ITE scores. This decrease was observed across content subsections and residency classes but was most pronounced for the post-graduate year-2 (PGY) class who began residency in July of 2020, shortly after the start of the pandemic. Identifying changes in residency training that led to decreased ITE scores may help residency programs address learning environment gaps and better position residents to pass their ABP certification exam.

Historically, factors associated with higher scores on the residency ITE have included performance on prior knowledge-based examinations,4 independent reading, and conference attendance.5, 6 Prior studies in surgical and anesthesiology programs have not found correlations between clinical case volume and examination scores.7, 8 One recent study of internal medicine and pediatric residents at a large academic hospital found a positive association between patient encounters in the second year of training and an increase in ITE score; however, this association was not seen for first year residents or for any of the pediatric-specific cohort.9 A study in pediatric residents found that the number of inpatient admissions, but not conference attendance or outpatient encounters, was correlated with an increase in ITE scores.10 Recent literature has also begun to explore resident physician burnout in multiple types of programs (orthopedic surgery, emergency medicine) as a factor in ITE performance, with mixed results.11, 12

We sought to better characterize changes in ITE scores and possible associations with clinical encounter numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic across four geographically diverse academic pediatric residency programs in North Carolina, Michigan, Arkansas, and California. All programs are medium sized with between 14-25 residents per year (Supplementary Table 1). We hypothesized that residents experienced a decrease in clinical encounters during the pandemic and that the number of clinical encounters would be associated with the change in ITE score between a resident’s first and second years.

Methods

We utilized the EPICTM electronic medical record (EMR) at each of the four pediatric residency programs to obtain data on patient notes as a proxy for patient encounters for three classes of general pediatric residents. We focused on three class years - one that was not affected by the pandemic during their intern year (“No COVID” or “NC” – entered residency in 2018), one that was partially affected by COVID-19 in March of their intern year (“Partial COVID” or “PC” – 2019) and one that was fully affected by the pandemic, starting in June of their intern year (“Full COVID” or “FC” – 2020). To standardize across programs, we included only residents in the general pediatric residencies at each site and excluded those in combined medicine/pediatrics or combined pediatric/subspecialty residency programs.

Reports were run through EPICTM to capture proxies for clinical encounters. Inpatient history and physical (H+P) notes and progress notes were used as a proxy for inpatient encounters. General pediatric outpatient clinic notes were utilized as a proxy for outpatient encounters and included all encounter types (well child checks, acute care visits, and follow-up visits for both new and established patients). Due to separate EMRs, any resident encounters that occurred at community hospitals were not included in the analysis. This accounted for 25% or less of clinical experience depending on the program. Individual ITE scores from July in the PGY-1 and PGY-2 years and pre-residency United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 CK scores, or Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination (COMLEX) scores, were obtained from each program. COMLEX scores were converted to Step 2 CK scores using percentile matching.13 Because of a known strong correlation between prior test scores and future test performance, we chose to focus on individual changes in ITE score between the first and second year of residency as opposed to absolute ITE scores3, 12, 14 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3). Overall, we aimed to explore the association of ITE score change with number of patient encounters, represented by number of total inpatient, total outpatient, H+P, and progress notes.

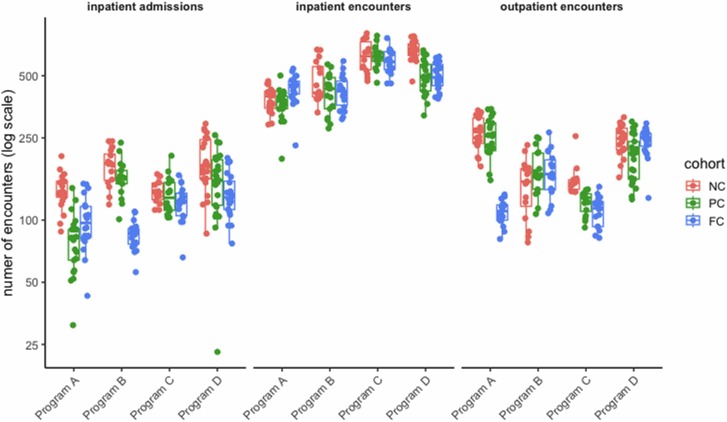

Fig. 2.

Number of patient encounters per resident by encounter type, program and cohort. Note log scale on y-axis.

This study was deemed exempt by each programs’ Institutional Review Board. (UNC -IRB 22-0362, University of Michigan -IRB HUM00216927, UAMS/ACH - IRB 274331, UCI/CHOC-IRB 220334).

Statistical analyses were performed using R (v4.1.1, Vienna, Austria). Association between ITE score and Step 2 CK scores was analyzed with a linear mixed model, treating cohort, program and individual resident as random effects and Step 2 CK score as a fixed effect. Association between ITE score change from first to second year and cohorts was analyzed with a linear mixed model, treating program as a random effect and Step 2 CK score and cohort as fixed effects. Differences between cohorts were estimated as linear contrasts in the resulting model using the emmeans package (v1.7.2), without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Confidence intervals for pairwise comparisons were constructed using the method of Kenward and Roger, as implemented in the pbkrtest package (v0.5.1). Association between ITE score change and number of patient encounters was analyzed with a linear mixed model, treating Step 2 CK score and program as random effects and number of patient encounters as a fixed effect (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2). The latter quantity was scaled to have mean zero and unit variance prior to model fitting, so that effect sizes are interpreted as (point difference in ITE score) per (1 standard deviation difference in number of patient encounters). All mixed models were fit using the lme4 package (v1.1-27.1), and confidence intervals for regression coefficients computed via the likelihood profile method.

Results

Our total cohort included 231 residents across the four programs, with class size ranging from 14 to 25 (Supplementary Table 1). Across programs and cohorts, Step 2 CK scores were positively correlated with ITE scores in both the PGY1 and PGY2 year (β = 0.73 ITE score points per Step 2 CK score point; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.63 - 0.83). However, Step 2 CK scores were not correlated with change in individual ITE score from the PGY1 to PGY2 year (β = 0.08 point increment in ITE score per Step 2 CK score point; 95% CI -0.06 - 0.23) (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure 2)

The differences in ITE score between first and second year varied across cohorts ( Figure 1). ITE scores on average improved from the PGY1 to PGY2 year in the NC (+12.2 points; 95% CI 6.1 - 18.3 points) and PC (+18.2 points; 95% CI 12.1 - 24.3 points) cohorts. The FC cohort had little to no improvement in ITE scores from PGY1 to PGY2 (-0.5 points; 95% CI -6.6 - 5.6 points). The estimated mean difference between the FC cohort and the NC and PC cohort ITE score changes was 12.7 points (95% CI 7.0 - 18.5 points) and 18.7 points (95% CI 13.0 - 24.4 points), respectively.

Fig. 1.

ITE score change between PGY1 and PGY2 year by program and cohort.

The number of patient encounters seen at the programs also differed by cohort, and the pattern was not uniform across programs, with some programs seeing a decline in inpatient encounters and others in outpatient encounters during the pandemic ( Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4).

After controlling for Step 2 CK score, the total number of patient encounters was not associated with a change in ITE scores from PGY1 to PGY2 (β = 1.8 point increment in ITE score per 1 SD change in number of patient encounters; 95%CI -0.8 - 4.3). There was a statistically significant association between change in ITE score and number of inpatient H+Ps (β = 2.3 point increment in ITE score per 1 SD change in number of inpatient H+P notes; 95% CI 0.1 - 4.8). This association was not observed with any of the other note types ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of number of patient encounters on ITE score change.

| covariate | estimate | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| all encounters | 1.84 | 1.33 | (-0.8, 4.35) |

| inpatient encounters | 0.67 | 1.36 | (-1.88, 3.26) |

| inpatient H&Ps | 2.35 | 1.20 | (0.07, 4.82) |

| outpatient encounters | 2.56 | 1.31 | (-0.32, 5.06) |

Discussion

Our study sought to examine the relationship between ITE scores and clinical encounters in pediatric residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Residents who matriculated during the COVID-19 pandemic did statistically worse than their colleagues from the prior two classes when comparing the change in their ITE scores even when controlling for prior test taking ability with Step 2 CK scores. This relationship was seen across the programs studied. There was variability in clinical encounter numbers seen across programs, with some programs seeing declines in numbers in certain clinical settings. H+P notes, our proxy for inpatient admission numbers, showed a small statistical correlation with change in ITE score. Overall, there are likely numerous other factors that contributed to ITE score change that were not examined in our study.

Clinical exposure, which in our study was measured by number of patient encounters, was not significantly associated with ITE score improvement. Prior studies have found mixed results when looking at the relationship of clinical experience and ITE scores, with some finding a positive association10 and others finding a lack of association,7, 8, 14 or an association only for certain class years.9 We suspect this mixed relationship is due to the complexity and variability of patient encounters, with some providing more learning than others. This is also likely why inpatient admissions, perhaps the most representative of novel patient encounters, was marginally associated with change in ITE scores in our resident group, mirroring a prior study that found that inpatient admissions was associated with change in ITE scores.10 The programs in the study reported a change in pattern of admissions during the pandemic, with decreased respiratory viruses and increased mental health admissions.

Although our study focused on patient encounters, many factors likely affected the learning environment of pediatric residencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gruppen et al (2019) proposed a learning environment conceptual frame work with the following elements: material, personal, social, and organizational.15 Numerous elements of the conceptual framework of the learning environment15 were affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Within the material dimension, didactic educational sessions changed across the nation as restrictions to in-person gatherings were mandated in many states. The programs in the study all shifted lectures to a virtual format initially. A study of the efficacy of resident virtual didactics has not been done, although a study of medical students suggested a virtual format did not change exam scores.16 The psychosocial dimension of the learning environment was also altered during the pandemic. In the personal realm, resident study habits may have shifted during the pandemic. Studying outside of work has had mixed effect on ITE scores in prior studies5, 17, 18 , 19 If residents studied less during the pandemic, this may have contributed to their decreased scores.

From a social perspective of the learning environment, relationships with others and sense of community were significantly altered. Globally, healthcare professional burnout increased during the pandemic.20 Burnout has been previously associated with worse performance on the ITE, although the causal direction in this relationship is unknown.11, 21 Pervasive burnout during the pandemic may negatively contribute to the work environment in numerous, immeasurable ways.

One of the limitations of our study is that we were unable to measure conference attendance or engagement, which likely changed during the pandemic and is a factor that has been previously associated with ITE scores.5, 6 The programs in the study had various challenges with tracking conference attendance during the pandemic, and we were unable to consistently compare conference attendance across programs or time. Although we looked at total clinical numbers, we did not have information surrounding complexity of patients or diagnoses a resident encountered, and how this varied across the pandemic years. The programs anecdotally reported a change in type of admissions with decreased respiratory and increased mental health admissions. They also reported a decline in ambulatory experiences during March through June of 2020. We were not able to quantify this pattern. Additionally, by using note reports from the EMR, we did not capture all of the clinical encounters for residents, including encounters without documentation, encounters where another provider documented, or encounters occurring in a different EMR. We also were unable to evaluate hospital census which may also have contributed to change in volume of patient encounters and overall clinical learning environment. In addition, the ITE was created to allow for individualized self-assessment information for a resident and their program, not for summed or aggregated analysis of a total cohort. Where we could, our analyses examined differences and associations within individuals rather than across aggregated cohorts. Finally, while our programs represented geographic diversity, all were medium-sized residency programs. Very small or very large programs may have had differing experiences.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated decreased clinical encounter numbers as well as decreased change in ITE score from the PGY1 to PGY2 year, most notable in the intern class fully affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a small but statistically significant association between number of inpatient H&Ps and change in ITE score, but total clinical encounter numbers were not associated with change in ITE score. Other factors that may have contributed to knowledge gaps not evaluated by our data include changes in conference format, changes in studying habits, and pervasive burnout. As residency programs work to recover from the pandemic, it will be crucial to continue to study the effects of this time on trainees and their ability to rebuild and recover from the pandemic. Program leadership should continue active work on mitigating deleterious effects of the pandemic, as our study suggests clinical encounter numbers are not fully responsible for the notable changes in test scores.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest, competing interests, or corporate sponsors.

Funding

The authors received no funding or grant support for this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.acap.2023.05.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Apply for General Peds Exam | American Board of Pediatrics. Accessed December 10, 2022. 〈https://www.abp.org/content/general-pediatrics-certifying-examination〉

- 2.Althouse L.A., McGuinness G.A. The In-Training Examination: An Analysis of Its Predictive Value on Performance on the General Pediatrics Certification Examination. J Pediatr. 2008;153(3):425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Exam Pass Rates | The American Board of Pediatrics. Accessed October 12, 2022. 〈https://www.abp.org/content/exam-pass-rates〉

- 4.Velez D.R. Prospective Factors that Predict American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination Performance: A Systematic Review. Am Surg. 2021;87(12):1867–1878. doi: 10.1177/00031348211058626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald F.S., Zeger S.L., Kolars J.C. Factors Associated with Medical Knowledge Acquisition During Internal Medicine Residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):962–968. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald F.S., Zeger S.L., Kolars J.C. Associations of Conference Attendance With Internal Medicine In-Training Examination Scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):449–453. doi: 10.4065/83.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGahan B.G., Hatef J., Gibbs D., et al. Correlation Between Neurosurgical Residency Written Board Scores and Case Logs. World Neurosurg. 2021;155:e236–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesicka A., Baker K.H. In-Training Examination scores do not correlate with clinical experience during the first year of clinical training in anesthesiology: A retrospective educational observational pilot study. J Clin Anesth. 2021;68 doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCoy C.P., Stenerson M.B., Halvorsen A.J., Homme J.H., McDonald F.S. Association of Volume of Patient Encounters with Residents’ In-Training Examination Performance. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1035–1041. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chase L.H., Highbaugh-Battle A.P., Buchter S. Residency Factors That Influence Pediatric In-Training Examination Score Improvement. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(4):210–214. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2011-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss E.J., Markus D.H., Kingery M.T., Zuckerman J., Egol K.A. Orthopaedic Resident Burnout Is Associated with Poor In-Training Examination Performance. J Bone Jt Surg. 2019;101(19) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanyo L.Z., Goyal D.G., Dhaliwal R.S., et al. Emergency Medicine Resident Burnout and Examination Performance. AEM Educ Train. 2020;5(3) doi: 10.1002/aet2.10527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnum S., Craig B., Wang X., et al. A Concordance Study of COMLEX-USA and USMLE Scores. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(1):53–59. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-21-00499.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frederick R.C., Hafner J.W., Schaefer T.J., Aldag J.C. Outcome measures for emergency medicine residency graduates: do measures of academic and clinical performance during residency training correlate with American Board of Emergency Medicine test performance? Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(Suppl 2):S59–S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruppen L.D., Irby D.M., Durning S.J., Maggio L.A. Conceptualizing Learning Environments in the Health Professions. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):969. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronenfeld J.P., Ryon E.L., Kronenfeld D.S., et al. Medical Student Education During COVID-19: Electronic Education Does Not Decrease Examination Scores. Am Surg. 2021;87(12):1946–1952. doi: 10.1177/0003134820983194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imran J.B., Madni T.D., Taveras L.R., et al. Assessment of general surgery resident study habits and use of the TrueLearn question bank for American Board of Surgery In-Training exam preparation. Am J Surg. 2019;218(3):653–657. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J.J., Kim D.Y., Kaji A.H., et al. Reading Habits of General Surgery Residents and Association With American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination Performance. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(9):882–889. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green I., Weaver A., Kircher S., et al. Impact of Question Bank Use for In-Training Examination Preparation by OBGYN Residents – A Multicenter Study. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(3):775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgantini L.A., Naha U., Wang H., et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PloS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smeds M.R., Thrush C.R., McDaniel F.K., et al. Relationships between study habits, burnout, and general surgery resident performance on the American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination. J Surg Res. 2017;217:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material