Abstract

Background

The noncholera Vibrio spp. which cause vibriosis are abundantly found in our water ecosystem. These bacteria could negatively affect both humans and animals. To date, there is a paucity of information available on the existence and pathogenicity of this particular noncholera Vibrio spp. in Malaysia in comparison to their counterpart, Vibrio cholera.

Methods

In this study, we extracted retrospective data from Malaysian surveillance database. Analysis was carried out using WHONET software focusing noncholera Vibrio spp. including Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio fluvialis, Vibrio alginolyticus, Vibrio hollisae (Grimontia hollisae), Vibrio mimicus, Vibrio metschnikovii, and Vibrio furnissii.

Results

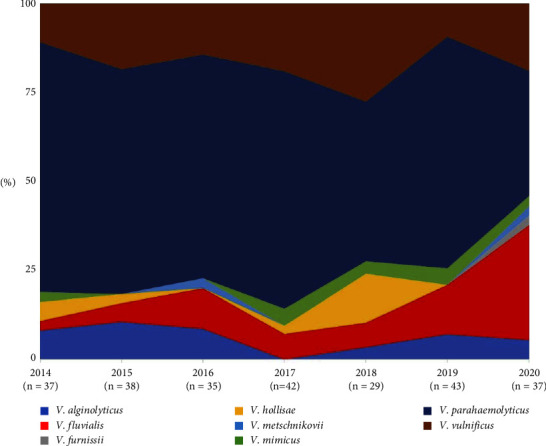

Here, we report the first distribution and prevalence of these species isolated in Malaysia together with the antibiotic sensitivity profile based on the species. We found that V. parahaemolyticus is the predominant species isolated in Malaysia. Noticeably, across the study period, V. fluvialis is becoming more prevalent, as compared to V. parahaemolyticus. In addition, this study also reports the first isolation of pathogenic V. furnissii from stool in Malaysia.

Conclusion

These data represent an important step toward understanding the potential emergence of noncholera Vibrio spp. outbreaks.

1. Introduction

Vibrio spp. are ubiquitous in freshwater, estuarine, and saltwater aquatic milieus [1]. They are curved Gram negative bacilli, oxidase and catalase positive, and are generally sensitive to vibriostatic agents. Their motility is conferred by polar flagella [2]. Vibrio genus consists of about 150 species which can be further categorized into halophilic and nonhalophilic Vibrio spp. based on their sodium requirement. Although nonhalophilic Vibrio spp. in humans usually cause moderate infection, they are also known to cause outbreaks in humans, fish, and other aquatic animals with undesirable economical and public health implications [3, 4].

Human vibriosis can be classified into two major groups: cholera and noncholera. Vibrio cholerae is an important human pathogen responsible for cholera. Cholera is both waterborne and foodborne causing approximately 1.3 to 5 million cases reported annually with the death toll of 21,000–143,000 lives/year [5, 6]. V. cholerae serotypes O1 and O139 are exclusively accountable for cholera epidemics. Upon entry into the human host, V. cholerae adhere to intestinal epithelium followed by secretion and accumulation of cholera toxin (CT), which is responsible for intense watery diarrhea that potentially led to fatality. Virulence genes located in the ToxR regulon within V. cholerae genome are in particular responsible for severe symptoms of cholera [7]. Meanwhile, V. cholerae serotypes non-O1 and non-O139 are responsible for sporadic cholera-like infections, bacteremia, and septicemia [8–10]. The V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 are categorized as noncholera Vibrio cholerae, as well as V. cholerae serotypes O1 and O139 that do not produce cholera toxin [11]. Such serotypes have been associated with clonal outbreak among diarrheal patients in Kolkata [12].

Other Vibrio spp., such as V. mimicus, V. metschnikovii, V. vulnificus, V. alginolyticus, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. furnissii, can also cause illnesses in humans known as vibriosis, which commonly is presented with gastrointestinal infection, wound infections, and septicemia [13]. Certain species such as V. metschnikovii have been isolated from a range of conditions such as septicemia and wound [14, 15]. Differently, cholera epidemics are highly associated with sanitary quality and socioeconomic status (typically transmitted from human to human or contaminated water). However, vibriosis caused by other Vibrio spp. is closely related to the consumption of contaminated shellfish or contaminated water and is independent of the sanitation status [6, 16, 17].

The presence and compositions of Vibrio spp. in aquatic habitats are dynamic and influenced by the geographical factor, climate, and salinity [18]. Therefore, analysis of local clinical and environmental data is necessary to develop an understanding of occurrences of vibriosis as a result of interaction between human health and other domains over time. This article aims to describe the current Vibrio spp. isolated from clinical samples in Malaysia from 2014 to 2020.

2. Materials and Methods

Nation-wide hospital antimicrobial susceptibility data between 2014 and 2020 were retrieved from Malaysia's local surveillance program. These data were catalogued in a downloadable database software developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), known as WHONET. The program converts various types of data from the different laboratory information systems of each hospital into a standardized common code and file format, enabling centralized data monitoring and analysis.

From 2014 to 2020, an average of 42 Malaysian hospitals participated in the WHONET-Malaysia network, contributing laboratory data consistently throughout the year. All antimicrobial tests and respective bacterial identification tests were performed in each hospital's clinical laboratories. This study focused on the available data associated with all noncholera Vibrio spp. reported within these seven surveillance years and their antimicrobial susceptibility profiles. In addition, V. cholerae nonO1/nonO139 was not included in this survey. The WHONET software provides basic statistical analysis of the input hospital data, with a special focus on the analysis of the antimicrobial susceptibility test results.

3. Results

Between 2017 and 2020, a total of 270 noncholera Vibrio spp. were isolated from 261 patients in Malaysia (Table 1). The distribution of samples was predominantly from stool (n = 137, 50.7%) and blood culture (n = 80, 29.6%). Among all, V. parahaemolyticus was the main species identified (n = 156, 57.8%), followed by V. vulnificus (n = 48, 17.8%), V. fluvialis (n = 30, 11.1%), V. alginolyticus (n = 16, 5.9%), and other Vibrio spp., namely, V. hollisae (Grimontia hollisae), V. mimicus, V. metschnikovii, and V. furnissii (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of noncholera Vibrio spp. based on specimen types.

| Organism | Type of specimen, n (%) | Total specimen, n(%) | Patien, t n(%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile | Blood | Ear | Eye | Fluid | Foot | Genital | Pus | Respiratory | Swab | Stool | Tissue | Urine | Unspecified | |||

| V. alginolyticus | 8 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 16 (5.9) | 16 (6.1) | ||||||||

| V. fluvialis | 2 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 30 (11.1) | 30 (11.5) | ||||||||

| V. furnissii | 1 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | |||||||||||||

| V. hollisae | 8 | 8 (3) | 8 (3.1) | |||||||||||||

| V. metschnikovii | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | ||||||||||||

| V. mimicus | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 9 (3.3) | 7 (2.7) | |||||||||

| V. parahaemolyticus | 18 | 2 | 3 | 118 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 156 (57.8) | 154 (59.0) | |||||||

| V. vulnificus | 1 | 35 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 48 (17.8) | 43 (16.5) | |||||

| Total | 3 (1.1) | 80 (29.6) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (2.2) | 137 (50.7) | 10 (3.7) | 5 (1.9) | 14 (5.2) | 270 | 261 |

The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern from our data showed that Vibrio spp. isolated from clinical isolates during the period of the study remained susceptible to the common antibiotic regimes (Table 2). For instance, 91–100% of the isolates were sensitive to ceftazidime, gentamicin, imipenem, and meropenem. Similarly, for ciprofloxacin, 94–100% of the isolates were sensitive, except the V. parahaemolyticus (82%). On the other hand, in the absence of ß-lactamase inhibitor, the sensitivity of V. parahaemolyticus and V. fluvialis towards ampicillin was only 9% and 16%, respectively. In addition, high percentage of resistance was observed in V. parahaemolyticus against cefuroxime (68%) and V. fluvialis towards cefotaxime (50%), respectively.

Table 2.

Sensitivity of noncholera Vibrio spp. against selected antibiotics (% of sensitivity).

| Organism/antibiotics | Ampicillin | Ampicillin/sulbactam | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Cefuroxime | Ceftazidime | Cefotaxime | Cefepime | Imipenem | Meropenem | Amikacin | Gentamicin | Ciprofloxacin | Bactrim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. alginolyticus | 70 | 67 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 100 | 100 | 80 | |

| V. fluvialis | 16 | 86 | 64 | 75 | 100 | 50 | 89 | 90 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 |

| V. furnissii | 100 | 100 | |||||||||||

| V. hollisae | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | ||||

| V. metschnikovii | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | ||||||||

| V. mimicus | 100 | 33 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 78 | ||

| V. parahaemolyticus 1 | 9 | 100 | 96 | 32 | 99 | 91 | 91 | 100 | 100 | 97 | 97 | 82 | 95 |

| V. vulnificus | 89 | 95 | 89 | 90 | 100 | 93 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 94 | 95 |

1Only this organism contains >50 isolates.

Across the 7-year surveillance (2014–2020), the average isolation of noncholera Vibrio was 37.3 cases/year (29–43 cases) (Figure 1). The data revealed that V. parahaemolyticus predominate the landscape of human infection during the period of the study. Surprisingly, V. fluvialis was increasingly isolated from clinical specimens from 3% in 2014 to 32% in 2020. Meanwhile, V. furnissii, V. hollisae, V. metschnikovii, and V. mimicus were not routinely isolated every consecutive year.

Figure 1.

The pattern of noncholera Vibrio isolation between 2014 and 2020.

4. Discussion

V. cholerae is rarely isolated in Malaysia, yet it remains an important threat to human health in many developing countries [19]. Steadily, noncholera Vibrio spp. such as V. fluvialis, V. mimicus, V. metschnikovii, and V. furnissii become emerging causes of human infections often associated with foodborne diarrheal outbreaks. The clinical manifestations depend on the host susceptibility, route of infections, and inoculum size [20, 21]. In this study, it is shown that V. parahaemolyticus was the main causative agent of vibriosis in Malaysia, consistent with the other part of the world [22]. V. parahaemolyticus is an aquatic zoonotic pathogen that not only infects humans but is also a threat to aquaculture animal health. In aquaculture animals, V. parahaemolyticus causes early mortality syndrome (EMS) in shrimps and vibriosis in fishes with a high mortality rate and cause significant economic losses [23, 24]. Following the infection alarm in humans, isolates of V. parahaemolyticus from seafood in Selangor Malaysia have been found and characterized to be resistant to several antibiotics and possess at least one plasmid and positive ToxR genes [25].

In this study, V. fluvialis show an increasing trend during the study period. To date, there is scarce information available on human infections caused by V. fluvialis [26, 27]. V. fluvialis is similar to other noncholera Vibrio spp., they cause mild self-limiting gastrointestinal infections. Oral fluid replacement therapy is the mainstay of symptomatic treatment in mild cases. However, antimicrobial therapy using doxycycline or ciprofloxacin can be initiated in severe or prolonged cases [6]. On the other hand, V. vulnificus infection is associated with a higher mortality rate, especially in high-risk patients with treatment delay [28]. This study also had shown V. vulnificus as the second causative agent of vibriosis human infection in Malaysia. In the US, Brazil, Italy, and India, the species become a healthcare burden with a mortality rate more than 30% [29]. This organism is a zoonotic pathogen that can cause septicemia in fish, where iron in the blood signals the production of toxins that elevate the severity [30]. The acquirement of genes to evade host immune systems and antibiotic resistance are aggravated by uncontrolled usage of antibiotics in the aquaculture sectors [31].

Multidrug-resistantVibrio spp. in the aquatic environment was common in fish farming [32, 33]. In Malaysia, it was reported that up to 80% of the Vibrio isolates from the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia were found to be resistant to one or more classes of antibiotics [34]. However, in this study, the vast majority of the clinical strains from human cases were sensitive to the cephalosporin and carbapenem class of antibiotics. Despite this observation, the retrieved surveillance data from human infections are limited by the number of isolates that were tested, hence may not represent the real clinical epidemiology. In some countries such as Bangladesh, China, and Vietnam, vibriosis is a significant public health problem, of which, outbreaks occur regularly, associated with wet season or summer with high dynamicity [35, 36]. For instance, V. parahaemolyticus serotype O10:K4, which have been frequently associated with outbreak in China, has spread to Thailand, with high sensitivities (89–100%) toward ß-lactam antibiotic such as ampicillin/sulbactam and ceftazidime [37, 38]. Overall, the incidence of noncholera vibriosis in Asia and Southeast Asia is likely to be underreported, as many cases are not diagnosed or notifiable to health authorities [6].

In summary, this study highlights Vibrio parahaemolyticus as a dominant Vibrio spp. causing vibriosis in Malaysia. Further analysis of the clinical significance of other Vibrio species that show emerging trends will require clinical data analysis and further laboratory characterization study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. The authors also would like to thank the laboratory personnel who contributed to the data and this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Ridhuan Mohd Ali, Email: ridhuanali@gmail.com.

Rohaidah Hashim, Email: rohaidah@moh.gov.my.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Disclosure

All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

MH, RH, and MRMA conceptualized and designed the study. MRMA, HFZ, and NANA were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data. MRMA, HFZ, and NANA contributed to methodology. SM and MH prepared the draft. All authors were responsible for revision of the article. All authors approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Osunla C. A., Okoh A. I. Vibrio pathogens: a public health concern in rural water resources in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2017;14(10):p. 1188. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janda J. M. Clinical decisions: detecting vibriosis in the modern era. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter . 2020;42(6):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2020.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deen J., Mengel M. A., Clemens J. D. Epidemiology of cholera. Vaccine . 2020;38:A31–A40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farmer J., Hickman-Brenner F. Prokaryotes . New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2006. The Genera Vibrio and Photobacterium; pp. 508–563. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali M., Nelson A. R., Lopez A. L., Sack D. A. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases . 2015;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832.e0003832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker-Austin C., Oliver J. D., Alam M., et al. Vibrio spp. infections. Nature Reviews Disease Primers . 2018;4(1):1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsiao A., Zhu J. Pathogenicity and virulence regulation of Vibrio cholerae at the interface of host-gut microbiome interactions. Virulence . 2020;11(1):1582–1599. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2020.1845039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramamurthy T., Mutreja A., Weill F. X., Das B., Ghosh A., Nair G. B. Revisiting the global epidemiology of cholera in conjuction with the genomics of Vibrio cholerae. Frontiers in Public Health . 2019;7:203–210. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Restrepo D., Huprikar S. S., VanHorn K., Bottone E. J. O1 and non-O1Vibrio cholerae bacteremia produced by hemolytic strains. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease . 2006;54(2):145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feghali R., Adib S. M. Two cases of vibrio cholera non-O1/non-O139 septicaemia with favourable outcome in Lebanon. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal . 2011;17(08):722–724. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.8.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cdc. Non-choleraVibrio cholerae infections. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/non-01-0139-infections.html#print .

- 12.Chatterjee S., Ghosh K., Raychoudhuri A., et al. Incidence, virulence factors, and clonality among clinical strains of non-O1, non-O139Vibrio cholerae isolates from hospitalized diarrheal patients in Kolkata, India. Journal of Clinical Microbiology . 2009;47(4):1087–1095. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02026-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker-Austin C., Jenkins C., Dadzie J., et al. Genomic epidemiology of domestic and travel-associated Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in the UK, 2008–2018. Food Control . 2020;115 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107244.107244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linde H. J., Kobuch R., Jayasinghe S., et al. Vibrio metschnikovii, a rare cause of wound infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology . 2004;42(10):4909–4911. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4909-4911.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konechnyi Y., Khorkavyi Y., Ivanchuk K., Kobza I., Sękowska A., Korniychuk O. Vibrio metschnikovii: current state of knowledge and discussion of recently identified clinical case. Clinical Case Reports . 2021;9(4):2236–2244. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris J. G., Acheson D. Cholera and other types of vibriosis: a story of human pandemics and oysters on the half shell. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2003;37(2):272–280. doi: 10.1086/375600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Usmani M., Brumfield K. D., Jamal Y., Huq A., Colwell R. R., Jutla A. A review of the environmental trigger and transmission components for prediction of cholera. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease . 2021;6(3):p. 147. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed6030147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vezzulli L., Grande C., Reid P. C., et al. Climate influence on Vibrio and associated human diseases during the past half-century in the coastal North Atlantic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . 2016;113(34):E5062–E5071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609157113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ear E. N. S., Che Azmi N. A., Nik Hashim N. H. H., et al. A rare and unusual cause of vibrio cholerae non-o1, non-o139 causing spontaneous peritonitis in a patient with cirrhosis. Tropical Biomedicine . 2021;38(1):183–186. doi: 10.47665/tb.38.1.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaysner C. A., Angelo DePaola J. Bacteriological Analytical Manual Chapter 9: Vibrio, Adm. U.S . Washington, DC, USA: Food Drug; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araj G. F., Taleb R., El Beayni N. K., Goksu E. Vibrio albensis: an unusual urinary tract infection in a healthy male. Journal of Infection and Public Health . 2019;12(5):712–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang C., Li Y., Jiang M., et al. Outbreak dynamics of foodborne pathogen Vibrio parahaemolyticus over a seventeen year period implies hidden reservoirs. Nat. Microbiol . 2022;7(8):1221–1229. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Schryver P., Defoirdt T., Sorgeloos P. Early mortality Syndrome outbreaks: a microbial management issue in shrimp farming? PLoS Pathogens . 2014;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003919.e1003919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ina-Salwany M. Y., Al-saari N., Mohamad A., et al. Vibriosis in fish: a review on Disease development and prevention. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health . 2019;31(1):3–22. doi: 10.1002/aah.10045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venggadasamy V., Tan L. T. H., Law J. W. F., Ser H. L., Letchumanan V., Pusparajah P. Incidence, antibiotic susceptibility and characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from seafood in selangor, Malaysia. Prog. Microbes Mol. Biol . 2021;4:1–34. doi: 10.36877/pmmb.a0000233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramamurthy T., Chowdhury G., Pazhani G. P., Shinoda S. Vibrio fluvialis: an emerging human pathogen. Frontiers in Microbiology . 2014;5:p. 91. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onohuean H., Agwu E., Nwodo U. U. A global perspective of Vibrio species and associated diseases: three-decade meta-synthesis of research advancement. Environmental Health Insights . 2022;16:p. 14. doi: 10.1177/11786302221099406.117863022210994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yun N. R., Kim D. M. Vibrio vulnificus infection: a persistent threat to public health. Korean Journal of Internal Medicine (English Edition) . 2018;33(6):1070–1078. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heng S. P., Letchumanan V., Deng C. Y., et al. Vibrio vulnificus: an environmental and clinical burden. Frontiers in Microbiology . 2017;8:p. 997. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernández-Cabanyero C., Lee C., Tolosa-Enguis V., et al. Adaptation to host in Vibrio vulnificus, a zoonotic pathogen that causes septicemia in fish and humans. Environmental Microbiology . 2019;21(8):3118–3139. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee L. H., Ab Mutalib N. S., Law J. W. F., Wong S. H., Letchumanan V. Discovery on antibiotic resistance patterns of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Selangor reveals carbapenemase producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in marine and freshwater fish. Frontiers in Microbiology . 2018;9:p. 2513. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maje M. D., Kaptchouang Tchatchouang C. D., Manganyi M. C., Fri J., Ateba C. N. Characterisation of Vibrio species from surface and drinking water sources and assessment of biocontrol potentials of their bacteriophages. International Journal of Microbiology . 2020;2020:15. doi: 10.1155/2020/8863370.8863370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.You G., Lee W. Antibiotic resistance and plasmid profiling of Vibrio spp. in tropical waters of Peninsular Malaysia. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment . 2016;188(3):171–15. doi: 10.1007/s10661-016-5163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amalina N. Z., Santha S., Zulperi D., et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility and plasmid profiling of Vibrio spp. isolated from cultured groupers in Peninsular Malaysia. BMC Microbiology . 2019;19(1):p. 251. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1624-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padovan A., Siboni N., Kaestli M., King W. L., Seymour J. R., Gibb K. Occurrence and dynamics of potentially pathogenic vibrios in the wet-dry tropics of northern Australia. Marine Environmental Research . 2021;169 doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2021.105405.105405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sampaio A., Silva V., Poeta P., Aonofriesei F. Vibrio spp.: life strategies, ecology, and risks in a changing environment. Diversity . 2022;14(2) doi: 10.3390/d14020097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada K., Roobthaisong A., Hearn S. M., et al. Emergence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus serotype O10:K4 in Thailand. Microbiology and Immunology . 2023;67(4):201–203. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y., Lyu B., Zhang X., et al. Vibrio parahaemolyticus O10:K4: an emergent serotype with pandemic virulence traits as predominant clone detected by whole-genome sequence analysis—beijing municipality, China, 2021. China CDC Wkly . 2022;4(22):471–477. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2022.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.