Abstract

Astrocytes respond to traumatic brain injury (TBI) with changes to their molecular make-up and cell biology, which results in changes in astrocyte function. These changes can be adaptive, initiating repair processes in the brain, or detrimental, causing secondary damage including neuronal death or abnormal neuronal activity. The response of astrocytes to TBI is often–but not always–accompanied by the upregulation of intermediate filaments, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin. Because GFAP is often upregulated in the context of nervous system disturbance, reactive astrogliosis is sometimes treated as an “all-or-none” process. However, the extent of astrocytes’ cellular, molecular, and physiological adjustments is not equal for each TBI type or even for each astrocyte within the same injured brain. Additionally, new research highlights that different neurological injuries and diseases result in entirely distinctive and sometimes divergent astrocyte changes. Thus, extrapolating findings on astrocyte biology from one pathological context to another is problematic. We summarize the current knowledge about astrocyte responses specific to TBI and point out open questions that the field should tackle to better understand how astrocytes shape TBI outcomes. We address the astrocyte response to focal vs. diffuse TBI and heterogeneity of reactive astrocytes within the same brain, the role of intermediate filament upregulation, functional changes to astrocyte function including potassium and glutamate homeostasis, blood-brain barrier maintenance and repair, metabolism, and reactive oxygen species detoxification, sex differences, and factors influencing astrocyte proliferation after TBI.

Graphical Abstract

Astrocytes’ response to traumatic brain injury is heterogeneous and affects astrocytes’ homeostatic roles (Created with Biorender).

1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) causes “reactive astrogliosis,” a heterogeneous astrocyte response characterized by molecular, cell biological, and functional changes. Reactive astrogliosis is often accompanied by the upregulation of intermediate filaments, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin; astrocyte hypertrophy, with swelling of main processes and the cell body; and other changes in astrocyte morphology, including the extension of processes toward an injury site. A subset of astrocytes may gain proliferative capacity. Due to the reliability of this response to any type of nervous system disturbance, it was originally thought to be an “all-or-none” process (Sofroniew & Vinters, 2010). However, the extent of astrocytes’ cellular, molecular, and physiological adjustments is not equal for each TBI type or even for each astrocyte within the same injured brain. Instead, astrogliosis comprises myriad graded alterations to gene and protein expression, the secretome, morphology (Sofroniew, 2015a) and function. Responses differ based on injury type (focal or diffuse), severity (mild, moderate, or severe), and distance from the injury site (adjacent to or distant from the focal lesion). For example, focal TBI induces “classic” reactive astrogliosis, with astrocytes directly adjacent to the injury site forming a protective border that seals off injured central nervous system (CNS) areas from areas exposed to tissue damage and blood-borne factors. Removing the proliferating, border-forming astrocytes after focal TBI results in larger lesion sizes and worse functional outcomes (Bush et al., 1999). Astrocytes more distant from a focal lesion also respond by upregulating intermediate filaments, yet proliferate less and their morphology and presumably their molecular makeup do not change as drastically. After mild/diffuse TBI, astrocytes become mildly reactive with upregulation of intermediate filaments in areas where the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is not damaged (Sabetta et al., 2023; Shandra et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2016). In areas with BBB breakdown, astrocytes respond surprisingly differently than they do after focal TBI: they neither upregulate GFAP/vimentin nor proliferate, and instead rapidly lose expression of most astrocyte-typical proteins (Shandra et al., 2019).

Many TBI studies assess GFAP levels but do not comprehensively characterize the different dimensions of the astrocyte response. Recent bulk and single-cell transcriptome studies (Arneson et al., 2018, 2022; Todd et al., 2021; Witcher et al., 2021; Xing et al., 2022) have assessed the molecular changes that astrocytes undergo in some TBI models. Yet, understanding astrocyte (dys)function after TBI is still in its infancy. Little is known about the regulatory processes creating heterogeneous reactive astrocyte subpopulations and the distinct functional changes in each subpopulation. It is also largely unknown how interactions between reactive astrocyte subpopulations and other cells, e.g., neurons or endothelial cells forming the BBB, are modified post-TBI. Astrocytes are necessary for BBB maintenance (Heithoff et al., 2021), Glu/K+ homeostasis (Robel & Sontheimer, 2015), gap junctional coupling, and gliovascular coupling (Biesecker et al., 2016; Newman, 2015; Shepherd & Charpak, 2008) in the healthy adult brain. Data from other pathologies, e.g., epilepsy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, stroke, or Alzheimer disease (Pekny et al., 2015; Sofroniew, 2015b), suggest that astrogliosis can affect these functions. Yet, it is less clear which astrocyte functions are affected by TBI-induced astrogliosis and how they vary. Additionally, astrogliosis can induce an inflammatory response, synaptogenesis, and tissue remodeling/repair through the release of soluble factors. Whether these gains in function are adaptive or maladaptive at different stages after TBI is not fully resolved.

This review summarizes our current knowledge about the astrocyte response to different types of TBI, how brain regions, time after injury, and sex affects this response, and consequences for astrocyte function.

2. Astrocyte response to Focal TBI

2.1. Modeling focal TBI in rodents

Astrocyte responses are best characterized in animal models in which focal TBI is induced. Stab wound injury, controlled cortical impact (CCI), or fluid percussion injury (FPI) are three rodent models that mimic the focal injuries of TBI patients. These injuries are induced by exposing the mouse brain by craniotomy, then “stabbing” the brain tissue with a micro knife or needle or by hitting the exposed brain surface with either an impactor (in CCI) or a fluid column (in FPI). While stab wounds result in a fairly “clean” cut, with focally restricted cell injuries resulting from damage to the cells and blood vessels in the knife/needle path, CCI and FPI can result in larger contusions, with the mechanical impact causing tissue compression, vascular damage, bleeding, edema, and ultimately secondary cell death. All three models induce focal injury—a lesion restricted to a specific brain area—with diffuse elements in FPI only.

2.2. Astrocyte morphology changes in response to focal TBI

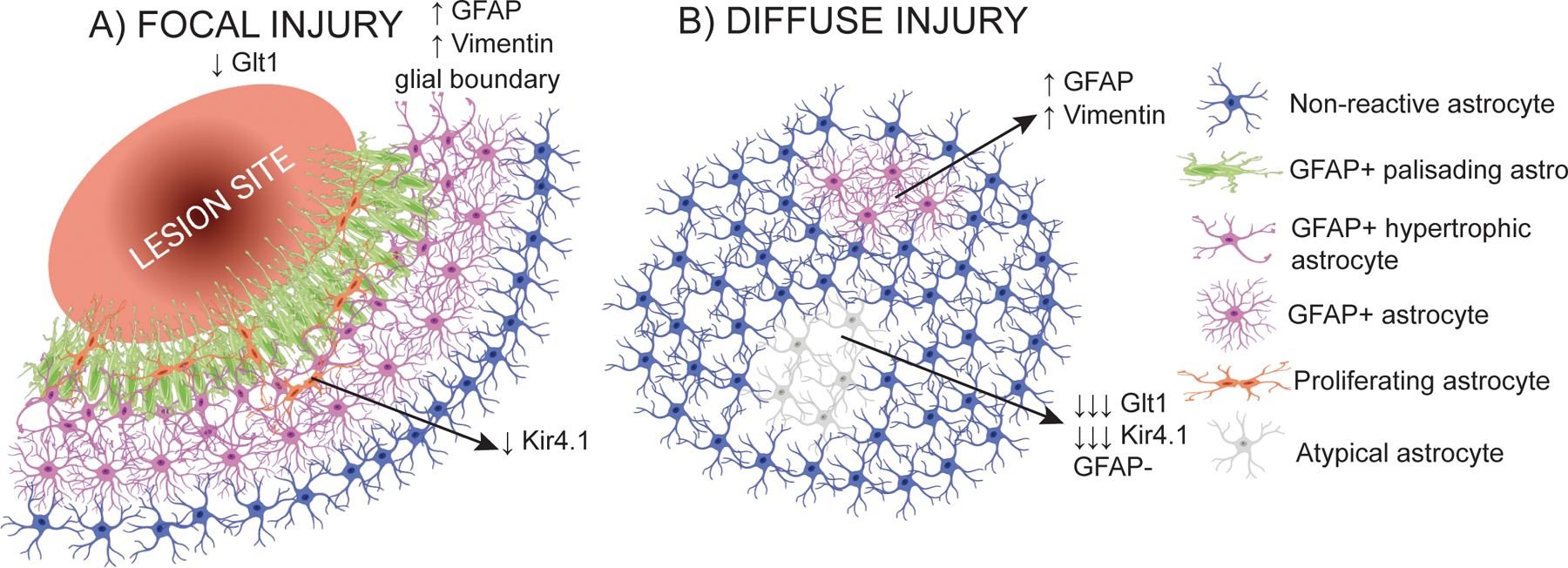

Focal TBI generates several reactive astrocyte phenotypes (Fig. 1A): Astrocytes directly bordering a stab wound injury adopt a palisading phenotype, elongating and extending their main processes toward the injury site (Oberheim et al., 2008; Robel et al., 2011). This palisading response can occur in one layer of astrocytes or extend to several layers of astrocytes, depending on injury severity. Palisading astrocytes, together with other glia, form a border that seals off uninjured brain tissue from injured areas. In serum-containing astrocyte cultures, Cdc42 and other RhoGTPases, as well as APC, integrins, and cadherins affect process elongation and orientation (Etienne-Manneville, 2008; Etienne-Manneville & Hall, 2003). In vivo, the molecular mechanisms regulating process elongation are almost entirely unknown, except for Cdc42, which regulates astrocyte morphology and proliferation after stab wound injury (Bardehle et al., 2013; Robel et al., 2011) and Drebrin, which regulates actin-dependent cytoskeleton rearrangement after stab wound (Schiweck et al., 2021). Notably, astrocytes in culture migrate in contrast to astrocytes in vivo. Astrocytes in vivo do not translocate their cell body or nucleus, even after proliferation. Mother and daughter cells stay close (Bardehle et al., 2013), increasing astrocyte density at the injury border (Frik et al., 2018; Lange Canhos et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Differences in astrocyte response depending on the type of injury. A) Schematic of the astrocyte response to focal injury. Astrocytes form a glial border around the lesion site, characterized by the upregulation of GFAP. Astrocytes closest to the lesion adopt a palisading phenotype and are more likely to proliferate. An overall decrease in Glt1 has been detected in focal injury TBI, but where the astrocytes with decreased Glt1 are located relative to the injury is not clear. B) Schematic of the astrocyte response to diffuse injury. In diffuse injury, no glial border is formed. At least two subtypes of astrocytes response can be found: astrocytes that upregulate GFAP, and astrocytes with an atypical response, in which there is not GFAP upregulation and the expression of astrocytes key proteins and markers decrease. Created with Biorender.

2.3. Astrocytes upregulate intermediate filaments in response to focal TBI

In the 1980s, Mathewson characterized the upregulated intermediate filament GFAP in response to TBI and compared it to upregulated GFAP in cortical gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), the glia limitans, and deeper structures in adult rats after stab wound injury (Mathewson & Berry, 1985). interestingly, except in palisading astrocytes, GFAP upregulation resolves over time in GM, while it persists in the striatum. This persisting GFAP upregulation in astrocytes located behind the glial border is possibly due to the tissue compression caused by enlarged ventricles adjacent to the striatum. In GM, tissue compression is resolved once edema and hematoma resolve. This phenomenon prompted the hypothesis that GFAP upregulation may be required to structurally stabilize the brain tissue, when forces like compression act on it, but that upregulation resolves in the absence of such forces.

In the healthy adult mouse brain, GFAP expression is most prominent in WM astrocytes and in the astrocyte endfeet surrounding large penetrating blood vessels in cortical GM. GFAP is present along blood vessels and within WM tracts—anatomical structures particularly vulnerable to mechanical shear stress and impaired vascular integrity in the uninjured aging brain of GFAP-null mice (Liedtke et al., 1996)—and GFAP-null mice have significantly higher mortality rates and extensive hemorrhaging in the cervical spinal cord after weight drop TBI (Brenner, 2014; Nawashiro et al., 1998), which induces tissue shearing. Yet though these studies point to GFAP’s role in maintaining the structural integrity of brain tissue, whether GFAP-expressing astrocytes in the uninjured brain indeed stabilize the vasculature or WM and the exact function(s) of GFAP upregulation after TBI remain a mystery.

In addition to GFAP, three other intermediate filaments can be upregulated in reactive astrocytes: vimentin, synemin, and nestin (Potokar et al., 2020). However, only vimentin and nestin have been studied in the context of TBI.

Vimentin’s expression patterns often closely follow those of GFAP, as vimentin can form heteropolymers with GFAP. Vimentin can also compensate for the absence of GFAP (Pekny et al., 1999), GFAP KO studies) after focal TBI, forming homopolymers comprising only vimentin. Vimentin provides mechanical support, similar to GFAP, and has been implicated in abnormal vesicle trafficking when it is upregulated post-TBI. When both GFAP and vimentin are knocked out, border formation is impaired after TBI, resulting in worsened outcomes, including extensive bleeding and increased mortality (Pekny et al., 1999)

The intermediate filament nestin, also expressed in adult neural stem cells, is upregulated in the subset of proliferating, reactive astrocytes closest to the injury site after focal laser injury (Sirko et al., 2009). Nestin cannot form homopolymers with itself but interacts with GFAP or vimentin to form filaments.

2.4. Astrocytes proliferate in response to focal TBI

Like neurons, astrocytes are generated during development and age with little turnover or replacement in the healthy mature brain(Ohlig et al., 2021; Schneider et al., 2022). After focal TBI, astrocytes have the capacity to re-enter the cell cycle. This phenomenon is best quantified after stab wound in mouse cortical GM. One day after stab wound, only a few astrocytes proliferate acutely; this number increases to 25% during the first week after stab wound (Frik et al., 2018). Astrocytes stop proliferating during the second week after focal TBI. In total, one third to one half of the astrocytes close to the focal TBI site re-enter the cell cycle (Buffo et al., 2008; Frik et al., 2018; Lange Canhos et al., 2021) after stab wound in cortical GM. In WM, significantly fewer astrocytes proliferate after stab wound (Mattugini et al., 2018) or CCI (Sullivan et al., 2013).

Proliferating astrocytes contribute to the dense glial border surrounding the focal injury (Frik et al., 2018; Lange Canhos et al., 2021), and astrocytes closer to the injury site are more likely to proliferate than distant astrocytes (Lange Canhos et al., 2021; Martín-López et al., 2013) (Fig. 1A). Because newborn astrocytes do not migrate and remain near their mother cells (Bardehle et al., 2013), newborn astrocytes are unlikely to replace cells lost to TBI. Indeed, genetically ablating small numbers of astrocytes does not initiate the proliferation of adjacent astrocytes (Heithoff et al., 2021).

A second stab wound recruits astrocytes that did not initially proliferate, in a monocyte-dependent fashion in addition to a subset of previously proliferating astrocytes (Lange Canhos et al., 2021), which suggests that most astrocytes may have proliferative potential if exposed to the appropriate factor. Whether there is heterogeneity in mechanisms and factors initiating proliferation in some astrocytes but not others is unresolved.

A number of molecular factors have been implicated in regulating proliferation, including Shh signaling (Sirko et al., 2013), Cdc42 (Bardehle et al., 2013), endothelin-1 (Gadea et al., 2008), Galectin 1 and 3 (Sirko et al., 2015), and FGF signaling (Kang et al., 2014).

Not all astrogliosis-causing brain injuries or conditions, e.g., models of massive neuronal death or Alzheimer disease, initiate astrocyte proliferation (Behrendt et al., 2013; Sirko et al., 2013). In a mouse model of chronic astrogliosis, which presents with abnormal astrocyte functions resulting in seizures, astrocytes also do not proliferate (Robel et al., 2009, 2015). Lastly, after mild/diffuse TBI, reactive astrocytes do not proliferate either (Shandra et al., 2019).

One distinguishing factor appears to be the extent of the brain tissue damage. Acute injuries that destroy brain tissue, either by mechanical impact (focal TBI) or oxygen and glucose deprivation (stroke), initiate astrocyte proliferation, while injuries or neurological diseases that do not induce drastic changes to tissue architecture do not initiate astrocyte proliferation. Several lines of evidence implicate blood-borne factors in the astrocyte proliferative response:

Astrocytes with cell soma adjacent to blood vessels preferentially proliferate and increase in number (Frik et al., 2018).

Blood-derived monocytes recruit astrocytes to proliferate after repeated injury (Frik et al., 2018).

Vascular damage is more extensive in conditions with astrocyte proliferation. Thus, perhaps the amount of exposure to blood-borne factors or type of factor determines if proliferation is initiated. After focal TBI or stroke, rapid and massive exposure to blood-borne factors occurs due to the rupture of large or multiple vessels. In contrast, vessel rupture and hemorrhage is rare in mild/diffuse TBI, and exposure to smaller blood-borne factors occurs from BBB damage rather than from ruptured blood vessels (Heithoff et al., 2021).

Astrocyte proliferation is greater in cortical GM than in WM, where vessel densities are lower (Mattugini et al., 2018; Sullivan et al., 2013).

3. Astrocyte response to diffuse TBI

3.1. Modeling diffuse TBI in rodents

The majority of human TBIs exhibit diffuse injury (Abou-Abbass et al., 2016), independent of injury severity, either alone or in combination with focal injury. Diffuse TBI is caused by acceleration-deceleration forces moving brain structures of different masses and densities at different speeds, which leads to tissue shearing, compression, and tension. These mechanical changes affect the cells within the tissue, especially long anatomical structures, e.g., axons and blood vessels, that span multiple cortical layers or brain regions. Mild TBIs/concussions are by definition diffuse only and without focal injury (the presence of a focal injury classifies the TBI as “moderate” or “severe” (Cifu et al., 2009). While no animal model fully recapitulates the complex and heterogeneous biomechanics of human TBI, several animal models mimic diffuse TBI. FPI uses a fluid pressure pulse that hits the exposed dura, inducing both focal and diffuse damage. FPI, even if calibrated to mild TBI, requires a craniotomy, and while the dura stays intact and no tissue loss is obvious, focal changes to the glia surrounding the impact area are clearly visible (Witcher et al., 2021). Thus “mild” TBI is not equivalent when comparing FPI and closed-head TBI models, e.g., the modified Marmarou weight drop (WD) model. The WD or impact-acceleration model mimics diffuse injury. The mouse is placed on a foam pad allowing for head movement and thus acceleration and deceleration of the brain upon impact. There is no clear focal impact area. Mild TBI models can also use a controlled cortical impactor fitted with a rubber tip, which hits the intact skull instead of the exposed brain. In these CCI models, the damage appears to be more locally confined (Bolte et al., 2020) than after WD TBI, when diffuse damage affects both hemispheres and also deeper brain structures.

The modified Marmarou WD model is scalable from mild to severe, and mimics many clinical aspects of TBI, including diffuse axonal injury and loss of consciousness (Marmarou et al., 1994; Nichols et al., 2016; Shandra et al., 2019). The severe impact results in neurological and cognitive deficits, including motor, behavior, learning, and memory impairments, as well as anxiety, and the underlying pathology includes cortical and hippocampal cell death, diffuse traumatic axonal injury, BBB breakdown, and edema (Chandel et al., 2016; Jellinger, 2009). If calibrated to mild injury (characterized by the absence of a focal lesion, neuronal death, and glial border formation), these mice experience sleep disturbances, increased anxiety, and cognitive deficits (Nichols et al., 2016), similar to the symptoms reported by patients with mild TBI.

3.2. Astrocyte changes after mild/diffuse TBI

After mild WD TBI, astrocytes respond: 1. “classically,” by becoming reactive, with GFAP and vimentin upregulation and some hypertrophy, but without elongating their processes; 2. “atypically,” by rapidly losing many of their proteins, including homeostatic proteins (Glt1, Kir4.1, glutamine synthetase), and housekeeping proteins (GAPDH, S100b), notably in the absence of GFAP or other intermediate filament upregulation; or 3. by exhibiting no obvious cell biological changes (Shandra et al., 2019) (Fig. 1B).

The subset of astrocytes that responds classically with upregulation of intermediate filaments approximately double or triple GFAP levels (Sabetta et al., 2023; Shandra et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2016), which is comparatively mild when compared to focal TBI where GFAP levels are higher (Vijayan et al., 1990). These astrocytes become lightly hypertrophic but proteins important for homeostatic functions including Kir4.1 and Glt1 appear unchanged. They also maintain their domain organization and do not elongate their processes as border-forming astrocytes do close to focal injury sites. Instead, their appearance is similar to mildly reactive astrocytes distant from a focal injury site (Shandra et al., 2019). Yet, whether they are indeed similar in their molecular makeup remains to be determined.

Importantly, no matter if GFAP-positive or atypical, astrocytes do not proliferate in response to mild/diffuse TBI, which may be due to the absence of factors that initiate proliferation. While atypical astrocytes are caused by exposure to blood-borne factors (George et al., 2022), the extent of BBB damage appears to substantially shape the astrocyte response. Mild/diffuse TBI mostly results in BBB damage that causes small (≤10kDa) factors to leak, with rare vessel rupture. In contrast, focal TBI results in blood vessel rupture exposing the tissue to large blood-borne factors, e.g., the clotting factor fibrinogen (340kDa), which initiates GFAP expression in astrocytes (Schachtrup et al., 2010). In a mouse model wherein some endothelial cells were genetically ablated to mimic post-TBI vessel rupture in the absence of mechanical impact, both atypical and classical astrocyte responses were rapidly initiated, suggesting that blood-borne factors indeed trigger varied reactive astrocyte subtypes (George et al., 2022). However, which blood-borne factors contributes to which astrocyte response remains a largely open question.

Another hypothesis is that astrocyte-astrocyte contact arrests cell proliferation. If TBI destroyed an astrocyte, neighboring astrocytes may sense the loss and initiate proliferation to replace it. Interestingly, ablating a small number of astrocytes results in limited BBB damage (mostly with extrusion of tracers 10 kDa and below) and a classic reactive response, but no astrocyte proliferation (Díaz-Castro et al., 2023; Heithoff et al., 2021). Thus, the absence of a neighboring astrocyte is not sufficient to initiate proliferation.

The atypical response is restricted to a small subset of astrocytes (i.e., ~6% of the cortical surface area). Yet, given that a single mouse astrocyte domain harbors 3–4 neuronal soma, 200–300 dendrites, and ~100,000 synapses, losing most astrocyte-typical proteins in even a few atypical astrocytes may affect neuronal network function dramatically.

The atypical response highlights the challenges of bulk and single-cell analysis approaches. First, data regarding different astrocyte responses to TBI within the same brain are merged in bulk analysis, which misses or dilutes the responses of small subtypes of astrocytes. For example, ~6% of the cortex is covered by atypical astrocytes, which likely impact neuronal function significantly but are essentially impossible to detect in bulk analyses. Second, single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) detects changes at the transcriptional level, but misses other regulatory processes, including post-translational modifications or the rapid degradation observed in atypical astrocytes. Furthermore, scRNA-seq typically uses certain genes to identify astrocytes (e.g., Slc1a2 (encoding for Glt1) (Arneson et al., 2018) and thus may not capture the reactive astrocyte populations that do not express those genes.

4. Transcriptome and proteome changes

4.1. Transcriptomic regulation of astrocyte changes in injury and disease

Several recent studies have assessed the transcriptome and/or proteome of astrocytes in pathology, and a few have compared different pathologies and CNS regions (Burda et al., 2022; Chai et al., 2017). These comparative studies revealed transcriptomic/proteomic signatures highly specific to both the CNS region and pathological contexts. For example, in spinal cord injury (SCI), lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation, and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), only 2.6% of the astrocyte-specific differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are shared. When comparing six different models of neurological diseases (SCI, epilepsy, LPS-induced inflammation, middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), EAE, glioblastoma), an even smaller number of DEGs were shared, one of them being vimentin. However, 61 “core” transcriptional regulators were shared, including Hif1a, Nfkb1, Myc, Smarca4, Sox11, Notch1, Stat3, and Stat4. The well-explored transcriptional regulators Smarca4 and Stat3 regulated some DEGs in the same direction and others in opposite directions after SCI or LPS exposure. Burda et al.’s study demonstrated that the outcome of transcriptional regulation depends less on the activity of a specific regulator and more on the pathological context (Burda et al., 2022).

While Burda et al.’s study did not include TBI datasets, another study using bulk RNA-seq data from astrocytes one week after severe FPI showed an overlap with only five of the 13 genes (Todd et al., 2021) identified as pan-reactive (Liddelow et al., 2017). That study compared reactive astrogliosis induced by LPS vs. MCAO and identified panels of pan-reactive genes and reactive subsets named A1 for neurotoxic and A2 for neuroprotective. A1 or A2 reactive astrocyte phenotypes have not been fully reproduced in other disease contexts (Escartin et al., 2021) and accordingly, Todd et al., detected only two A1 and one A2 gene as differentially regulated in astrocytes after severe FPI (Todd et al., 2021). Thus, TBI elicits unique transcriptional changes in astrocytes, as previously suspected.

4.2. Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq after FPI

Several studies have assessed transcriptional changes in astrocytes after mild or severe FPI (Arneson et al., 2018, 2022; Todd et al., 2021; Witcher et al., 2021; Xing et al., 2022). One week after severe FPI, bulk RNA-seq of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-sorted astrocytes and microglia demonstrated cell type-specific transcriptional changes in both cell types. Surprisingly, only 55 genes were differentially regulated in astrocytes, while 518 were differentially regulated in microglia (Todd et al., 2021). Similarly, 55 genes were altered in astrocytes one week after mild FPI in a scRNA-seq study (Witcher et al., 2021). Here, genes including GFAP and ApoE were upregulated while DEGs related to growth factor signaling, extracellular matrix remodeling, and astrocytic Notch signaling were downregulated. Assessing astrocyte transcriptional changes at different time points after FPI revealed that most changes occur acutely; fewer genes are differentially expressed one week and one month after FPI (Arneson et al., 2018; Witcher et al., 2021).

scRNA-seq studies after mild FPI demonstrate significant global transcriptomic shifts in astrocytes at an earlier timepoint. Here, 24 hours post injury (hpi), 247 DEGs were detected, and pathways upregulated in astrocytes included those related to energy/metabolism and cell death regulation. Notably, genes involved in oxidative stress and the electron transport chain were downregulated in astrocytes and other cell types at this early time point. The calcium/calmodulin pathways were also differentially regulated. The data further suggested metabolic depression (Arneson et al., 2018, 2022). Interestingly, a week later, genes related to metabolic regulation were “boosted” in microglia, dentate gyrus granule cells, and smooth muscle cells, but not in astrocytes (Arneson et al., 2022). Together, FPI induces early changes to the transcriptome which are moderated at later timepoints.

4.3. Comparing mild vs. severe FPI and different brain regions

A comparison of mild vs. severe FPI revealed only two shared DEGs, GFAP and Igfbp5 (Todd et al., 2021). After severe FPI, DEGs unique to astrocytes were related to immune and defense responses to viruses, while mild FPI increased CEBPB-mediated signaling, indicative of inflammatory gene expression. These data may suggest that mild and severe FPI cause different astrocyte response programs, or they may point to challenges when comparing data collected using different techniques and parameters and/or data processing pipelines. Thus, whether different injury severities indeed lead to different transcriptional programs would require a side-by-side comparison of the astrocyte transcriptome and/or proteome using the same methodology.

A study from the Gotz group revealed differences in GM cells’ injury response under two conditions: stab wound injury to both white and gray matter vs. to GM only (Mattugini et al., 2018). A proteomic analysis showed that only 28.5% of the same proteins were expressed under both conditions. Pathways involved in blood coagulation, fibrinolysis, wound closure, and proliferation were upregulated with and without WM involvement. However, pathways indicative of increased oxidative stress, decreased reducing agents, and actin and cytoskeletal rearrangements were only regulated when the WM was damaged. Furthermore, some proteins were upregulated under one of the conditions and downregulated in the other (Mattugini et al., 2018), similar to Burda et al.’s findings. While this study does not assess the proteome of astrocytes specifically, these results indicate that astrocyte responses to TBI may vary by exact location or affected brain regions. This finding is highly relevant because in human TBI, WM is likely to be affected by focal and diffuse TBI due to the gyrated nature of the cortex. Thus, using models that only injure cortical GM may make translating the findings to the clinic more challenging.

4.5. New directions/conclusions

These recent RNA-seq studies revealed that there are more transcriptional changes in astrocytes one day after TBI than at later time points, when cell biological changes are more obvious. This timing is interesting considering the long-held assumption that astrocytes respond slowly to brain injury, which is mostly based on astrocytes’ morphological changes and the pronounced expression of intermediate filaments such as GFAP. At the same time, early transcriptional changes in astrocytes appear to be largely microglia-independent (Witcher et al., 2021), suggesting that previously held notions about microglia being the first responders to brain injury, initiating the response of other glia, may not be accurate. Intriguingly, at later time points, a larger percentage of transcriptional changes in astrocytes appear to be microglia-dependent, at least after mild FPI (Witcher et al., 2021)This may be due to cytokines released by microglia that contribute to the inflammatory astrocyte response to FPI.

5. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS detoxification

Oxidative stress, which causes secondary injury after TBI, is generated by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant events in the brain. Astrocytes play a key role in detoxifying ROS and thus managing oxidative stress in the brain, yet their contribution post-TBI has not been studied. In resting conditions, neurons produce high levels of ROS because of their high oxidative mitochondrial activity, which is the main source of cellular ROS. Unlike neurons, astrocytes express high levels of several antioxidant enzymes and scavengers, including GST, GSR, and GSH, the most abundant mammalian thiol-containing antioxidant and a critical molecule in oxidative stress protection (Fernandez-Fernandez et al., 2012). Astrocytes and neurons interact to limit oxidative stress in the brain (Iwata-Ichikawa et al., 1999). Astrocytes produce GSH precursors that are taken up by neurons, protecting these cells from oxidative stress (Seib et al., 2011) One important source of oxidative damage in neurons after TBI is iron deposition, caused by hemorrhages or microbleeds. Neurons are more sensitive than astrocytes to iron-induced toxicity (Kress et al., 2002) due to the antioxidant enzymes and mechanisms triggered in astrocytes in response to iron, such as the decrease of ferritin receptors to limit iron uptake. Yet, how astrocytes deal with the oxidative stress associated with bleeds after TBI has not been studied.

Oxidative stress and inflammation are linked and regulate each other. It has been suggested that protein-disulfide isomerase-associated 3 (PDIA3), a member of the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway, is protective in early neurodegeneration (Woehlbier et al., 2016) and deleterious in cancer (Ramos et al., 2015). PDIA3 expression is increased in TBI patient samples and in CCI mice, with the increased expression occurring mostly in astrocytes. Deleting PDIA3 globally alleviated TBI-induced memory impairment and improved motor function, which correlated with ameliorated oxidative stress; decreased inflammation markers, such as IL-6 and TNFα; and reduced neuronal death (Wang et al., 2019). These findings suggest that modulating an astrocytic protein involved in endoplasmic reticulum oxidative stress is sufficient to alleviate TBI consequences in mice.

6. Functional Changes of Astrocytes after TBI

6.1. Astrocyte glutamate and potassium clearance changes after TBI

In the healthy brain, astrocytes are almost exclusively responsible for removing extracellular glutamate and potassium to maintain very low extracellular concentrations (Olsen & Sontheimer, 2008; Zhou & Danbolt, 2013).

Given that glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter, low extracellular glutamate levels are important to maintain a high signal-to-noise ratio during neurotransmission (Danbolt, 2001). Glutamate concentrations above this low baseline level can cause seizures and glutamate excitotoxicity, damaging or killing neurons by excessive glutamate receptor activation and calcium influx into neurons. Excitotoxicity is a major mechanism for secondary neuronal death after TBI (Baracaldo-Santamaría et al., 2022).

To quickly uptake glutamate and potassium and avoid the spread of glutamate into neighboring areas, parenchymal astrocytes possess a highly branched morphology, with their finest processes enwrapping synapses. At these processes they express the potassium channel Kir4.1 and the glutamate transporters Glt-1/Glast, which mediate extracellular glutamate and potassium clearance. TBI changes astrocyte morphology, including the thickening and retraction of primary, secondary, and tertiary processes (Oberheim et al., 2008; Robel et al., 2011), which may contribute to abnormal neuronal function. While Oberheim demonstrated astrocyte morphological changes in models of epilepsy, it has not yet been shown that these differences in morphology cause abnormal neuronal activity.

However, brain glutamate concentrations are increased during the first week after TBI (Piao et al., 2019; Zhuang et al., 2019). Glt1 is reduced within a few hours and for at least one week after focal TBI (Gupta & Prasad, 2013; Piao et al., 2019; Raghavendra Rao et al., 1998). These findings are based on bulk analysis and do not clarify which astrocytes subpopulations (border-forming or distant to the injury site) lose Glt1 (Fig. 1A). It is also not yet known if focal TBI may also initiate atypical astrocytes and if those may be intermingled with other astrocyte responses surrounding the injury site.

This decrease in Glt1 is regulated by the plasma factor thrombin, which binds to the Par1 receptor and also affects expression of Glast. Glast but not Glt1 expression is recovered by pharmacologically antagonizing Par1 (Piao et al., 2019). After diffuse injury, Glt1 (and Kir4.1) decrease in atypical astrocytes within minutes (—(George et al., 2022; Shandra et al., 2019)a loss sustained for ≥6 months. While astrocytic glutamate transporter function has been extensively studied in other pathologies (Campbell et al., 2020; Muñoz-Ballester et al., 2019; Robel et al., 2015), it has not yet been assessed in TBI.(Oberheim et al., 2008; Robel et al., 2011)Neurons release potassium ions (K+) during repolarization of their membrane. An increase in extracellular K+ shifts its equilibrium potential to more positive values, bringing the neuron closer to the firing threshold and rendering the cell more excitable. Astrocytic Kir4.1 is responsible for potassium uptake from the extracellular space. Interestingly, there is an inverse relationship between Kir4.1 expression and the proliferative capacity of astrocytes. Dividing cells have relatively positive resting membrane potentials (−30 to −50mV) compared to differentiated cells (Bordey & Sontheimer, 1997; Sontheimer et al., 1989). During development, astrocyte differentiation and exit from the cell cycle are correlated with a negative shift in resting potential and the upregulation and function of Kir channels. Conversely, re-entering the cell cycle after a stab wound is accompanied by Kir4.1 downregulation, especially in juxtavascular astrocytes (Götz et al., 2021), suggesting that proliferating astrocytes at a focal injury site may have impaired potassium-buffering capacity. Yet, there were no significant changes in resting membrane potential, though Kir4.1 contributes to the very negative resting membrane potential in astrocytes and though proliferating astrocytes in culture have more positive resting membrane potentials.

TBI can lead to morphological changes in astrocytes and a decrease in glutamate transporters and the potassium channel Kir4.1, potentially contributing to neuronal death and abnormal neuronal activity. Yet, the exact interactions between astrocytes and neurons after TBI remain to be resolved.

6.2. Metabolic Functions

TBI outcomes are affected by the severity of the metabolic crisis following impact. This metabolic crisis, characterized by an increase in the lactate/pyruvate ratio, comprises two phases: a ~6-hour hypermetabolic phase, in which glucose consumption, glycolysis, and ATP production are increased, and a hypometabolic phase, in which they are decreased (Hutchinson et al., 2009). The length of this second phase is one of the best predictors of the severity of TBI consequences, both in patients and animal models (Glenn et al., 2003; Marcoux et al., 2008; Vespa et al., 2003). Though the metabolic crisis and TBI response and recovery are clearly linked, cell-specific contributions to the metabolic crisis have not been fully addressed.

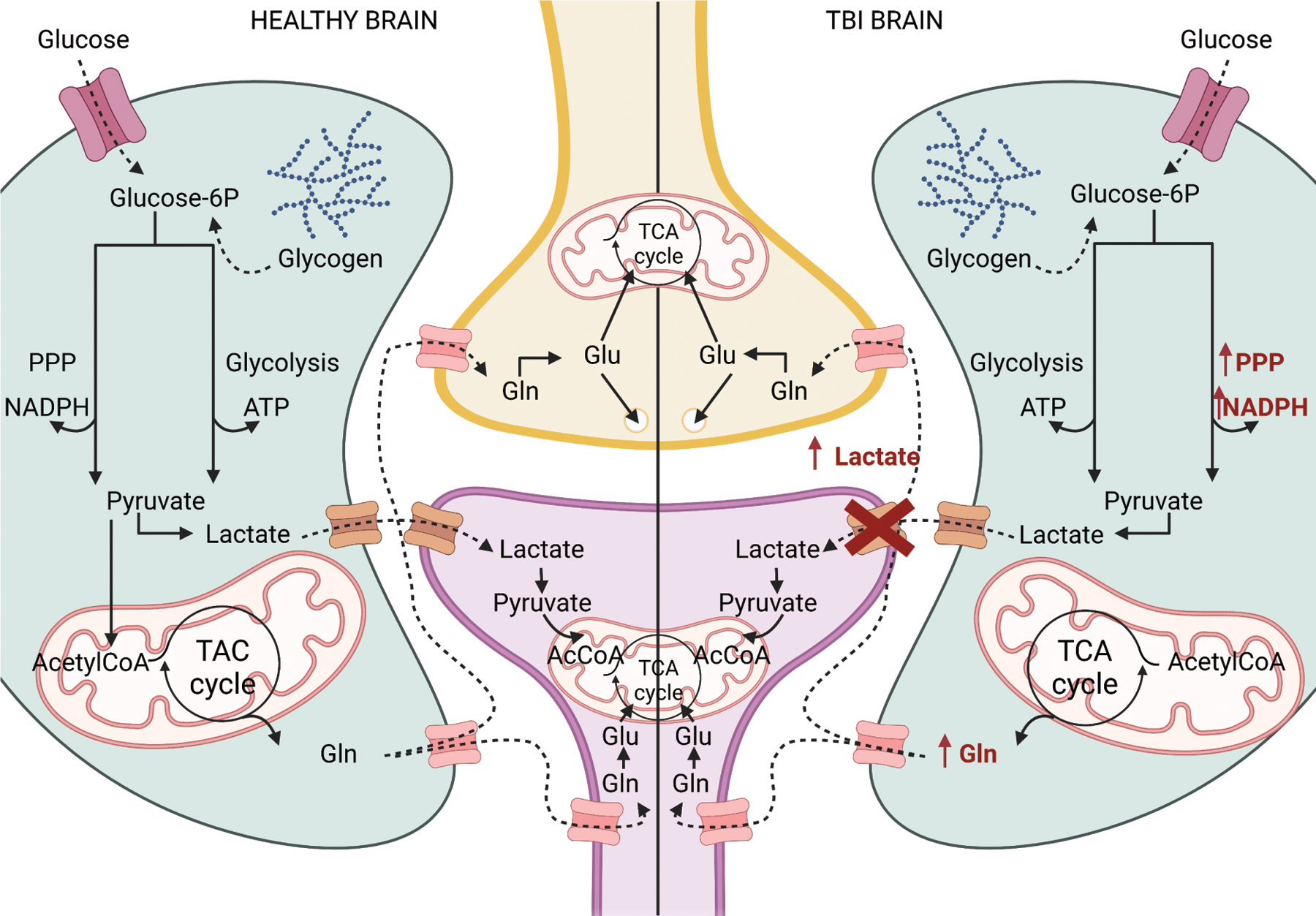

Astrocytes play pivotal roles in energy, neurotransmitter, and amino acid metabolism in the brain. In the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle system, astrocytes take up and convert glucose into pyruvate and then into lactate, which is released into the extracellular space and taken up by neurons for further oxidative degradation. Both cell types are metabolically coupled in the system: neurons depend on astrocytes to maintain the high neuronal energy demand for oxidative phosphorylation, while astrocytes have an aerobic glycolytic profile and can survive even when astrocyte mitochondrial respiration is absent (Supplie et al., 2017). Furthermore, astrocytes but not neurons are able to store glucose as glycogen, which they use to sustain neuronal activity during hypoglycemia or periods of increased energy demand (Suh et al., 2007). Astrocytes are also involved in the glutamine-glutamate cycle, in which glutamate released into the synaptic cleft is taken up by astrocytes, converted into glutamine, and released into the extracellular space, where it is taken up by neurons. Once in the neuron, glutamine can be converted back into glutamate, for packaging into synaptic vesicles, or it can provide the carbon backbone necessary to synthetize intermediaries of the Krebs cycle or other key molecules like the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. If this supply is compromised, neurons are not able to form neurotransmitters as they need.

Many preclinical and clinical studies address brain metabolism changes after TBI. These studies identified alterations in glycolysis rate or pentose phosphate pathway changes, metabolic pathways preferentially occurring in astrocytes (Fig. 2). But these studies did not establish exactly how astrocytes contribute to the metabolic crisis. Using glucose labeled with 13C, a metabolite processed by neurons and astrocytes, and labeled acetate, a metabolite taken up exclusively by astrocytes, Bartnik-Olson et al. established that oxidative metabolism is altered both in neurons and astrocytes after FPI, but astrocytes retain greater capacity for glucose oxidative metabolism (Bartnik-Olson et al., 2010). Astrocytes also increase glutamine production during the hypometabolic phase, and trafficking metabolites between neurons and astrocytes remains functional following the metabolic crisis. The authors proposed that the astrocytes’ metabolic adjustments might serve to maintain or restore oxidative metabolism. In contrast, after WD TBI, astrocytes maintain glucose oxidative metabolism, releasing lactate to the extracellular space. Yet, astrocyte-neuron communication was interrupted and neurons were unable to take up the released lactate, which increased its extracellular levels (Lama et al., 2014). The authors proposed that the increased lactate levels were deleterious to neurons due to changes in pH and that scavenging the excess extracellular lactate may be a potential new therapeutic strategy.

Figure 2.

On the left, a simplified summary of the metabolic coupling between astrocytes and neurons. On the right, a representation of anomalies in astrocyte-neuron metabolic coupling after TBI. In red, the pathways/proteins that are changed after TBI. TCA: tricarboxylic acid cycle, PPP: pentose phosphate pathway, Gln: glutamine, Glu:glutamate, AcCoA: acetylCoA. Created with Biorender.

A significant increase in the pentose phosphate pathway was detected after FPI, CCI, and WD and in patients (Amorini et al., 2016; Bartnik et al., 2005; Dusick et al., 2007; Jalloh et al., 2018). This pathway is preferentially used by astrocytes and is important for biosynthesizing nucleotides and producing NADPH, which provides reducing molecules for redox homeostasis. Thus, astrocytes may provide metabolites to prevent oxidative stress and protect the brain after TBI.

6.3. BBB damage & repair

After injury, astrocytes can both help and hinder BBB repair. They can secrete factors, e.g., matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), that increase BBB permeability (Michinaga & Koyama, 2019) and can also upregulate the expression of molecules suggested to modulate BBB integrity, including Shh (Yue et al., 2020), GDNF, and angiopoietin-1 (Xia et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2002), which has prompted the interpretation that astrocytes repair the BBB. However, most studies ablated the molecules during development, using either full knockouts or conditional deletion in radial glia. Radial glia give rise to astrocytes and neurons, thus Cre lines, such as hGFAP-Cre or nestin-Cre that are sometimes considered astrocyte-specific, recombine subsets of neurons (Malatesta et al., 2003). Neurons also express the BBB-modulating factor Shh (Sirko et al., 2013). It is thus still unresolved whether molecules released specifically by astrocytes are necessary to initiate BBB repair after injury. The use of tamoxifen-inducible astrocyte-specific Cre lines (e.g. Aldh1l1-CreERT2) would enable us to distinguish between cell types.

To further complicate the interpretation of these studies, astrocytes have receptors for these same molecules, and this signaling plays a role in regulating different aspects of the astrocyte response to injury. For example, astrocytes express the Shh receptor Patched, and Shh signaling is required for reactive astrocytes to proliferate after focal injury (Sirko et al., 2013). TGFb, which decreases the expression of tight junction protein occludin by upregulating MMPs, binds to TGFβ receptor 1 on astrocytes and phosphorylates the transcription factor Smad2, which results in GFAP and extracellular matrix molecule upregulation (Schachtrup et al., 2010). Many studies assess BBB integrity indirectly by injecting a tracer into the periphery and then analyzing whether the tracers made it into the brain parenchyma. Other studies assess the leakage of other blood-borne factors, including plasma proteins, immune cells, or erythrocytes, as indirect indicators of BBB dysfunction. Leakage of all of these factors can, to a degree, be contained by the glial border induced by focal TBI, yet reduced leakage may not necessarily represent restored BBB properties, such as tight junction integrity, metabolic barrier integrity, or reduced transcytosis. To distinguish the BBB integrity and border-forming astrocytes, the properties of the BBB have to be assessed directly.

After mild TBI/concussion, microbleeds can persist unrepaired for months in patients (Griffin et al., 2019) and mice (George et al., 2022). One possible explanation for this surprising phenomenon is the atypical response of astrocytes in BBB-damaged areas, where neither tight junctions nor the basement membrane are repaired months after mild WD (George et al., 2022). This lack of repair could be due to the inability of atypical astrocytes (and their astrocyte neighbors) to form a border (likely due to the absence of a clear “lesion” to form a border around) and possibly due to the lack of soluble factors aiding in BBB repair, given that most astrocyte-specific proteins are lost in these cells. Alternatively, atypical astrocytes may release factors (i.e., MMPs) that keep the BBB open. Further research is needed to distinguish which mechanism is at play.

The mechanism by which the BBB is repaired after TBI is not yet resolved–if it is repaired at all. First, it is important to differentiate between vessel repair and BBB repair. There is two-photon imaging evidence showing that ruptured vessels are repaired and re-perfused (George et al., 2022). Yet, to our knowledge, there is no direct evidence that the BBB is restored at vessels affected by TBI. All current evidence is indirect, such as the extent of tracer leakage or changes in the numbers of tight junctional mRNA or proteins, without demonstrating that the proteins are localized to previously damaged vessels and assembled into functional tight junctions. This is important, as in stroke, the BBB is not restored on damaged vessels in the ischemic core, but angiogenesis occurs in the perilesional area followed by the appearance of the tight junction protein claudin-5 but not zona occludens 1 at these newly formed vessels, which hence remain permeable (Yang & Torbey, 2020). Thus, bulk analyses for tight junction proteins alone are not suited to evaluate BBB repair and tightness on damaged or newly formed vessels. Angiogenesis also occurs after TBI. CCI leads to vascular loss at the injury site followed by revascularization within days that continues for 2–3 weeks (Lin et al., 2022; Salehi et al., 2018). Initially, immature non-perfused vessels originating in the perilesional area radiate toward the injury site. Interestingly, an increase in vessel density was also observed in the contralateral site (Salehi et al., 2018). This increase in vascular density correlates with restored blood flow and recovery of motor impairments (Lin et al., 2022). The maturity or integrity of the BBB was not assessed in these studies.

In summary, focal TBI causes vessel rupture with rapid and massive leakage of small and large blood-borne factors. Mild/diffuse TBI causes smaller damage permeant to ≤10kDa factors. This damage is already present minutes after the injury and coincides with an abnormal BBB while vessels otherwise appear largely intact. Tracers continuously leak for months after mild/diffuse TBI (Heithoff et al., 2021). In contrast, focal injury initiates astrocyte border formation, which contributes to restricting leakage of blood-borne factors or tracers to the injury core within weeks after focal TBI (Bush et al., 1999; Watkins et al., 2014). It remains to be resolved whether atypical astrocytes after diffuse TBI are incapable of repairing the BBB, if they actively contribute to the long-lasting damage, or if BBB properties are generally not fully restored on damaged vessels after TBI.

7. Sex-Specific astrocyte responses to TBI

Growing evidence indicates that sex contributes to differences in post-TBI outcomes (Albanese et al., 2017; Biegon, 2021; Mikolić et al., 2021; Sollmann et al., 2018; Spano et al., 2019). Yet, few studies have examined sex differences with respect to astrocytes in general or specifically following TBI. Moreover, studies are often not powered to detect sex differences or do not use statistical analyses that allow sex differences to be detected (Rechlin et al., 2022).

Many studies deduce a lack of astrocyte-related sex-specific differences based on a lack of differences in GFAP staining. However, GFAP is not only an imperfect marker for TBI-induced changes in astrocytes (Escartin et al., 2021; Shandra et al., 2019) but also an unreliable indicator of sex-related differences in astrocyte biology, given that estrogens activate GFAP expression (Luquin et al., 1993). GFAP levels fluctuate through the estrous cycle in the amygdala (Martinez et al., 2006; Stone et al., 1998), hippocampus (Arias et al., 2009; Luquin et al., 1993), and neocortex (Struble et al., 2006). Yet, most studies do not assess or report the estrous cycle stage at the time of the TBI. Differences in GFAP expression after TBI depend on the time after injury and the area of the brain. In one study, females had higher cortical GFAP expression than males after CCI (Jullienne et al., 2018). Another study found contradictory results: males had larger GFAP-covered areas in the cortex, dentate gyrus, and thalamus (Villapol et al., 2017). While the brain region (cortex) and time points were identical in both studies, the speed of CCI and the analyses were not, potentially contributing to the difference. This sex-specific difference disappeared after one week in the dentate gyrus and after one month in the cortex.

Estrogen production in females could explain a slower GFAP increase in females compared to males after TBI when males had higher GFAP levels than females. Yet, treatment with an inhibitor of estrogen synthesis (letrazol) increased GFAP levels in females but not in males (Gölz et al., 2019). Whether estrogen was directly targeting astrocytes or indirectly changing GFAP expression was not addressed in the study.

Serum amyloid A (SAA) was increased in astrocytes early after CCI only in males (Soriano et al., 2020). This protein facilitates immune cell infiltration to the injury sites, contributing to the inflammation process. Thus, the study suggests that the inflammatory response might be differently regulated in males and females.

Female astrocytes in culture are more resistant to oxidative stress than male astrocytes (Liu et al., 2007). This sex-based difference in susceptibility to oxidative stressors disappeared when estradiol synthesis was inhibited, or when cultures were treated with 17-β-estradiol. Some studies found sex differences in the resistance to oxidative stress in the context of TBI. Females express more heme-oxygenase 1 (HO-1)—a known antioxidant enzyme activated by hypoxia, heme, and heat (Sharp et al., 2013)—than males in astrocytes after CCI (Jullienne et al., 2018), suggesting stronger antioxidant signaling in astrocytes in females than in males. Along similar lines, the production of mitochondrial H2O2 one day after CCI is increased in males but not in females (Greco et al., 2020). However, which cell type was contributing to this increase in ROS was not assessed. Finally, protein carbonylation, a known consequence of oxidative stress, increases only in astrocytes and in regions with ependymal cells in males but not females after CCI (Lazarus et al., 2015). Interestingly, not all proteins were equally susceptible to carbonylation: GFAP was one of the proteins with increased carbonylation. All these studies point to more oxidative stress resistance in female than in male astrocytes after TBI. Yet the effects that this greater resistance might have on cell function, brain physiology, and post-TBI outcomes need to be studied.

A recent TBI metabolic study that included males and females analyzed how different metabolic substrates helped to overcome certain aspects of the metabolic crisis related to mitochondrial function (Greco et al., 2020). The type of substrate and the time of administration needed to overcome the metabolic crisis were different between males and females: early lactate and late β-hydroxibutyrate (BHB) improved mitochondrial function in males, while both early and late BHB had deleterious effects on all metabolic measurements in females. These results suggest that 1) the substrates needed to overcome the metabolic crisis and improve TBI outcomes are sex-specific and 2) the pathways and enzymes involved in the metabolic crisis that can process these substrates to meet the metabolic need are different in males and females. However, only glycogen content was quantified as an approximation of astrocyte metabolism. Due to the relevance of the metabolic crisis in TBI recovery and the significant role that astrocytes play in brain metabolism, it is important to address whether there are sex differences in astrocyte metabolism after TBI.

Finally, studies are now finding that molecular mechanisms following TBI may differ between males and females. Yet, many of these studies do not address in which cell type the changes originate. For example, the glucocorticoid receptor gene and protein expression levels are only increased in the hippocampus of females after FPI (Bromberg et al., 2020). The authors suggest that there might be sex-specific changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis after TBI because neurons in the hypothalamus control that function. Yet, besides neurons, glucocorticoid receptors are also expressed in astrocytes, and this study did not determine in which cell type the increase in glucocorticoid receptor was found.

As a summary, while astrocytes might contribute to some of the sex difference outcomes observed in patients and animal models, our knowledge on the mechanisms by which sex-specific changes in astrocytes affect TBI outcomes is still in its infancy.

Conclusions AND PERSPECTIVE

Astrocytes play a vital role in modulating adaptive and maladaptive processes in response to TBI. Traditional markers like GFAP have helped understand astrocyte responses in the past, but new tools and technologies, including Cre lines and viral delivery systems with higher specificity for astrocytes, membrane-tethered calcium-indicators and fluorescent reporters that capture fine processes, glutamate sensors, and spatial transcriptomics now enable deeper exploration of the mechanisms that drive changes in astrocyte cell biology and function. These tools allow for specific manipulation of astrocytes or assessment of astrocyte function at specific time points without affecting other cell types or at single cell resolution, providing unprecedented levels of precision. The field has merely started using these tools to their full potential to determine the exact mechanisms by which astrocytes either help the brain adapt to injury or cause further damage.

Reactive astrogliosis has been demonstrated to have beneficial and harmful consequences. Yet, especially in the context of TBI many questions remain. For example, it is still unclear whether loss of homeostatic functions is an unfortunate side effect of other aspects of reactive astrogliosis (e.g. proliferation resulting in reduced Kir4.1 levels) or if different functional changes can be attributed to different reactive astrocyte subtypes. Astrocytes are key players in many processes that are thought to shape TBI outcomes (oxidative stress, metabolism, BBB integrity), yet the exact mechanisms by which they either help the brain to adapt to injury or cause more damage are not resolved. Finally, little is known about the molecular mechanisms driving sex differences in astrocytes and how they may shape TBI outcomes.

In summary, astrocytes are key players modulating adaptive and maladaptive processes in response to TBI. Identifying the underlying molecular processes that shape differing astrocyte responses after TBI will be crucial to the development of therapeutic strategies limiting or even reversing brain damage.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Magdalena Gotz for her excellent comments on the manuscript and to Wendy Spitzer for editing the manuscript.

Funding Information

The authors were supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01NS105807 and R01NS121145.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Carmen Muñoz-Ballester, Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States.

Stefanie Robel, Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States.

References

- Abou-Abbass H, Bahmad H, Ghandour H, Fares J, Wazzi-Mkahal R, Yacoub B, Darwish H, Mondello S, Harati H, el Sayed MJ, Tamim H, & Kobeissy F (2016). Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of traumatic brain injury in Lebanon: A systematic review. Medicine, 95(47), e5342. 10.1097/MD.0000000000005342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albanese BJ, Boffa JW, Macatee RJ, & Schmidt NB (2017). Anxiety sensitivity mediates gender differences in post-concussive symptoms in a clinical sample. Psychiatry Research, 252, 242–246. 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2017.01.099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorini AM, Lazzarino G, di Pietro V, Signoretti S, Lazzarino G, Belli A, & Tavazzi B (2016). Metabolic, enzymatic and gene involvement in cerebral glucose dysmetabolism after traumatic brain injury. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, 1862(4), 679–687. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias C, Zepeda A, Hernández-Ortega K, Leal-Galicia P, Lojero C, & Camacho-Arroyo I (2009). Sex and estrous cycle-dependent differences in glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity in the adult rat hippocampus. Hormones and Behavior, 55(1), 257–263. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arneson D, Zhang G, Ahn IS, Ying Z, Diamante G, Cely I, Palafox-Sanchez V, Gomez-Pinilla F, & Yang X (2022). Systems spatiotemporal dynamics of traumatic brain injury at single-cell resolution reveals humanin as a therapeutic target. Cell. Mol. Life Sci, 79(9), 480. 10.1007/s00018-022-04495-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arneson D, Zhang G, Ying Z, Zhuang Y, Byun HR, Ahn IS, Gomez-Pinilla F, & Yang X (2018). Single cell molecular alterations reveal target cells and pathways of concussive brain injury. Nat Commun, 9(1), 3894. 10.1038/s41467-018-06222-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baracaldo-Santamaría D, Ariza-Salamanca DF, Corrales-Hernández MG, Pachón-Londoño MJ, Hernandez-Duarte I, & Calderon-Ospina CA (2022). Revisiting Excitotoxicity in Traumatic Brain Injury: From Bench to Bedside. Pharmaceutics, 14(1). 10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS14010152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardehle S, Krüger M, Buggenthin F, Schwausch J, Ninkovic J, Clevers H, Snippert HJ, Theis FJ, Meyer-Luehmann M, Bechmann I, Dimou L, & Götz M (2013). Live imaging of astrocyte responses to acute injury reveals selective juxtavascular proliferation. Nat Neurosci, 16(5), 580–586. 10.1038/nn.3371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartnik BL, Sutton RL, Fukushima M, Harris NG, Hovda DA, & Lee SM (2005). Upregulation of Pentose Phosphate Pathway and Preservation of Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Flux after Experimental Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 22(10), 1052–1065. 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartnik-Olson BL, Oyoyo U, Hovda DA, & Sutton RL (2010). Astrocyte Oxidative Metabolism and Metabolite Trafficking after Fluid Percussion Brain Injury in Adult Rats. J Neurotrauma, 27(12), 2191–2202. 10.1089/neu.2010.1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt G, Baer K, Buffo A, Curtis MA, Faull RL, Rees MI, Götz M, & Dimou L (2013). Dynamic changes in myelin aberrations and oligodendrocyte generation in chronic amyloidosis in mice and men. Glia, 61(2), 273–286. 10.1002/glia.22432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegon A (2021). Considering Biological Sex in Traumatic Brain Injury. In Frontiers in Neurology (Vol. 12, p. 576366). Frontiers Media S.A. 10.3389/fneur.2021.576366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesecker KR, Srienc AI, Shimoda AM, Agarwal A, Bergles DE, Kofuji P, & Newman EA (2016). Glial Cell Calcium Signaling Mediates Capillary Regulation of Blood Flow in the Retina. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(36), 9435–9445. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1782-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte AC, Dutta AB, Hurt ME, Smirnov I, Kovacs MA, McKee CA, Ennerfelt HE, Shapiro D, Nguyen BH, Frost EL, Lammert CR, Kipnis J, & Lukens JR (2020). Meningeal lymphatic dysfunction exacerbates traumatic brain injury pathogenesis. Nature Communications 2020 11:1, 11(1), 1–18. 10.1038/s41467-020-18113-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordey A, & Sontheimer H (1997). Postnatal development of ionic currents in rat hippocampal astrocytes in situ. Journal of Neurophysiology, 78(1), 461–477. 10.1152/JN.1997.78.1.461/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/JNP.JY25F12.JPEG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M (2014). Role of GFAP in CNS injuries. Neuroscience Letters, 565, 7–13. 10.1016/J.NEULET.2014.01.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg CE, Condon AM, Ridgway SW, Krishna G, Garcia-Filion PC, Adelson PD, Rowe RK, & Thomas TC (2020). Sex-Dependent Pathology in the HPA Axis at a Sub-acute Period After Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. Frontiers in Neurology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2020.00946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffo A, Rite I, Tripathi P, Lepier A, Colak D, Horn A-P, Mori T, & Götz M (2008). Origin and progeny of reactive gliosis: A source of multipotent cells in the injured brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(9), 3581–3586. 10.1073/pnas.0709002105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda JE, O’Shea TM, Ao Y, Suresh KB, Wang S, Bernstein AM, Chandra A, Deverasetty S, Kawaguchi R, Kim JH, McCallum S, Rogers A, Wahane S, & Sofroniew M. v. (2022). Divergent transcriptional regulation of astrocyte reactivity across disorders. Nature, 606(7914), 557–564. 10.1038/s41586-022-04739-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush TG, Puvanachandra N, Horner CH, Polito A, Ostenfeld T, Svendsen CN, Mucke L, Johnson MH, & Sofroniew M. v. (1999). Leukocyte infiltration, neuronal degeneration, and neurite outgrowth after ablation of scar-forming, reactive astrocytes in adult transgenic mice. Neuron, 23(2), 297–308. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80781-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SC, Muñoz-Ballester C, Chaunsali L, Mills WA, Yang JH, Sontheimer H, & Robel S (2020). Potassium and glutamate transport is impaired in scar-forming tumor-associated astrocytes. Neurochem Int, 133, 104628. 10.1016/j.neuint.2019.104628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai H, Diaz-Castro B, Shigetomi E, Monte E, Octeau JC, Yu X, Cohn W, Rajendran PS, Vondriska TM, Whitelegge JP, Coppola G, & Khakh BS (2017). Neural Circuit-Specialized Astrocytes: Transcriptomic, Proteomic, Morphological, and Functional Evidence. Neuron, 95(3), 531–549.e9. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel S, Gupta SK, & Medhi B (2016). Epileptogenesis following experimentally induced traumatic brain injury - A systematic review. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 27(3), 329–346. 10.1515/REVNEURO-2015-0050/XML [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifu D, Hurley R, Peterson M, Cornis-Pop M, Rikli PA, Ruff RL, Scott SG, Sigford BJ, Silva KA, Tortorice K, Vanderploeg RD, Withlock W, Bowles A, Cooper D, Drake A, & Engel C (2009). Clinical practice guideline: Management of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 46(6), CP1. 10.1682/JRRD.2009.06.0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC (2001). Glutamate uptake. Progress in Neurobiology, 65(1), 1–105. 10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00067-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Castro B, Robel S, & Mishra A (2023). Astrocyte Endfeet in Brain Function and Pathology: Open Questions. Https://Doi.Org/10.1146/Annurev-Neuro-091922–031205, 46(1). 10.1146/ANNUREV-NEURO-091922-031205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusick JR, Glenn TC, Lee WNP, Vespa PM, Kelly DF, Lee SM, Hovda DA, & Martin NA (2007). Increased pentose phosphate pathway flux after clinical traumatic brain injury: A [1,2–13C2]glucose labeling study in humans. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 27(9), 1593–1602. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escartin C, Galea E, Lakatos A, O’Callaghan JP, Petzold GC, Serrano-Pozo A, Steinhäuser C, Volterra A, Carmignoto G, Agarwal A, Allen NJ, Araque A, Barbeito L, Barzilai A, Bergles DE, Bonvento G, Butt AM, Chen W-T, Cohen-Salmon M, … Verkhratsky A (2021). Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nat Neurosci, 24(3), 312–325. 10.1038/s41593-020-00783-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S (2008). Polarity proteins in glial cell functions. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 18(5), 488–494. 10.1016/J.CONB.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S, & Hall A (2003). Cdc42 regulates GSK-3β and adenomatous polyposis coli to control cell polarity. Nature 2003 421:6924, 421(6924), 753–756. 10.1038/nature01423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Fernandez S, Almeida A, & Bolaños JP (2012). Antioxidant and bioenergetic coupling between neurons and astrocytes. Biochemical Journal, 443(1), 3–11. 10.1042/BJ20111943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frik J, Merl-Pham J, Plesnila N, Mattugini N, Kjell J, Kraska J, Gómez RM, Hauck SM, Sirko S, & Götz M (2018). Cross-talk between monocyte invasion and astrocyte proliferation regulates scarring in brain injury. EMBO Reports, 19(5), e45294. 10.15252/embr.201745294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadea A, Schinelli S, & Gallo V (2008). Endothelin-1 Regulates Astrocyte Proliferation and Reactive Gliosis via a JNK/c-Jun Signaling Pathway. J Neurosci, 28(10), 2394–2408. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5652-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George KK, Heithoff BP, Shandra O, & Robel S (2022). Mild Traumatic Brain Injury/Concussion Initiates an Atypical Astrocyte Response Caused by Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction. J Neurotrauma, 39(1–2), 211–226. 10.1089/neu.2021.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn TC, Kelly DF, Boscardin WJ, McArthur DL, Vespa P, Oertel M, Hovda DA, Bergsneider M, Hillered L, & Martin NA (2003). Energy dysfunction as a predictor of outcome after moderate or severe head injury: Indices of oxygen, glucose, and lactate metabolism. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 23(10), 1239–1250. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000089833.23606.7F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gölz C, Kirchhoff FP, Westerhorstmann J, Schmidt M, Hirnet T, Rune GM, Bender RA, & Schäfer MKE (2019). Sex hormones modulate pathogenic processes in experimental traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurochemistry, 150(2), 173–187. 10.1111/jnc.14678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz S, Bribian A, López-Mascaraque L, Götz M, Grothe B, & Kunz L (2021). Heterogeneity of astrocytes: Electrophysiological properties of juxtavascular astrocytes before and after brain injury. Glia, 69(2), 346–361. 10.1002/glia.23900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco T, Vespa PM, & Prins ML (2020). Alternative substrate metabolism depends on cerebral metabolic state following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol, 329, 113289. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin AD, Turtzo LC, Parikh GY, Tolpygo A, Lodato Z, Moses AD, Nair G, Perl DP, Edwards NA, Dardzinski BJ, Armstrong RC, Ray-Chaudhury A, Mitra PP, & Latour LL (2019). Traumatic microbleeds suggest vascular injury and predict disability in traumatic brain injury. Brain, 142(11), 3550–3564. 10.1093/BRAIN/AWZ290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, & Prasad S (2013). Early down regulation of the glial Kir4.1 and GLT-1 expression in pericontusional cortex of the old male mice subjected to traumatic brain injury. Biogerontology, 14(5), 531–541. 10.1007/S10522-013-9459-Y/FIGURES/4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heithoff BP, George KK, Phares AN, Zuidhoek IA, Munoz-Ballester C, & Robel S (2021). Astrocytes are necessary for blood–brain barrier maintenance in the adult mouse brain. Glia, 69(2), 436–472. 10.1002/GLIA.23908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson PJ, O’Connell MT, Seal A, Nortje J, Timofeev I, Al-Rawi PG, Coles JP, Fryer TD, Menon DK, Pickard JD, & Carpenter KLH (2009). A combined microdialysis and FDG-PET study of glucose metabolism in head injury. Acta Neurochirurgica, 151(1), 51–61. 10.1007/S00701-008-0169-1/TABLES/4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata-Ichikawa E, Kondo Y, Miyazaki I, Asanuma M, & Ogawa N (1999). Glial Cells Protect Neurons Against Oxidative Stress via Transcriptional Up-Regulation of the Glutathione Synthesis. Journal of Neurochemistry, 72(6), 2334–2344. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722334.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalloh I, Helmy A, Howe DJ, Shannon RJ, Grice P, Mason A, Gallagher CN, Murphy MP, Pickard JD, Menon DK, Carpenter TA, Hutchinson PJ, & Carpenter KLH (2018). A comparison of oxidative lactate metabolism in traumatically injured brain and control brain. Journal of Neurotrauma, 35(17), 2025–2035. 10.1089/NEU.2017.5459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA (2009). Recent advances in our understanding of neurodegeneration. Journal of Neural Transmission 2009 116:9, 116(9), 1111–1162. 10.1007/S00702-009-0240-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullienne A, Salehi A, Affeldt B, Baghchechi M, Haddad E, Avitua A, Walsworth M, Enjalric I, Hamer M, Bhakta S, Tang J, Zhang J, Pearce WJ, & Obenaus A (2018). Male and female mice exhibit divergent responses of the cortical vasculature to traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, neu.2017.5547. 10.1089/neu.2017.5547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang W, Balordi F, Su N, Chen L, Fishell G, & Hébert JM (2014). Astrocyte activation is suppressed in both normal and injured brain by FGF signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(29), E2987–E2995. 10.1073/pnas.1320401111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress GJ, Dineley KE, & Reynolds IJ (2002). The Relationship between Intracellular Free Iron and Cell Injury in Cultured Neurons, Astrocytes, and Oligodendrocytes. The Journal of Neuroscience, 22(14), 5848–5855. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05848.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lama S, Auer RN, Tyson R, Gallagher CN, Tomanek B, & Sutherland GR (2014). Lactate Storm Marks Cerebral Metabolism following Brain Trauma. J Biol Chem, 289(29), 20200–20208. 10.1074/jbc.M114.570978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange Canhos L, Chen M, Falk S, Popper B, Straub T, Götz M, & Sirko S (2021). Repetitive injury and absence of monocytes promote astrocyte self-renewal and neurological recovery. Glia, 69(1), 165–181. 10.1002/glia.23893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RC, Buonora JE, Jacobowitz DM, & Mueller GP (2015). Protein carbonylation after traumatic brain injury: cell specificity, regional susceptibility, and gender differences. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 78, 89–100. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, Bennett ML, Münch AE, Chung W-S, Peterson TC, Wilton DK, Frouin A, Napier BA, Panicker N, Kumar M, Buckwalter MS, Rowitch DH, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, … Barres BA (2017). Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature, 541(7638), 481–487. 10.1038/nature21029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, Edelmann W, Bieri PL, Chiu FC, Cowan NJ, Kucherlapati R, & Raine CS (1996). GFAP Is Necessary for the Integrity of CNS White Matter Architecture and Long-Term Maintenance of Myelination. Neuron, 17(4), 607–615. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80194-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Chen L, Jullienne A, Zhang H, Salehi A, Hamer M, C. Holmes T, Obenaus A, & Xu X (2022). Longitudinal dynamics of microvascular recovery after acquired cortical injury. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 10(1), 1–19. 10.1186/S40478-022-01361-4/FIGURES/9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Hurn PD, Roselli CE, & Alkayed NJ (2007). Role of P450 Aromatase in Sex-Specific Astrocytic Cell Death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 27(1), 135–141. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquin S, Naftolin F, & Garcia-Segura LM (1993). Natural fluctuation and gonadal hormone regulation of astrocyte immunoreactivity in dentate gyrus. Journal of Neurobiology, 24(7), 913–924. 10.1002/neu.480240705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta P, Hack MA, Hartfuss E, Kettenmann H, Klinkert W, Kirchhoff F, & Götz M (2003). Neuronal or glial progeny: Regional differences in radial glia fate. Neuron, 37(5), 751–764. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00116-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J, McArthur DA, Miller C, Glenn TC, Villablanca P, Martin NA, Hovda DA, Alger JR, & Vespa PM (2008). Persistent metabolic crisis as measured by elevated cerebral microdialysis lactate-pyruvate ratio predicts chronic frontal lobe brain atrophy after traumatic brain injury*. Critical Care Medicine, 36(10), 2871–2877. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186a4a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou A, Abd-Elfattah Foda MA, van den Brink W, Campbell J, Kita H, & Demetriadou K (1994). A new model of diffuse brain injury in rats. Part I: Pathophysiology and biomechanics. Journal of Neurosurgery, 80(2), 291–300. 10.3171/jns.1994.80.2.0291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FG, Hermel EES, Xavier LL, Viola GG, Riboldi J, Rasia-Filho AA, & Achaval M (2006). Gonadal hormone regulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity in the medial amygdala subnuclei across the estrous cycle and in castrated and treated female rats. Brain Research, 1108(1), 117–126. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-López E, García-Marques J, Núñez-Llaves R, & López-Mascaraque L (2013). Clonal Astrocytic Response to Cortical Injury. PLOS ONE, 8(9), e74039. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson AJ, & Berry M (1985). Observations on the astrocyte response to a cerebral stab wound in adult rats. Brain Research, 327(1), 61–69. 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91499-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattugini N, Merl-Pham J, Petrozziello E, Schindler L, Bernhagen J, Hauck SM, & Götz M (2018). Influence of white matter injury on gray matter reactive gliosis upon stab wound in the adult murine cerebral cortex. Glia, 66(8), 1644–1662. 10.1002/glia.23329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michinaga S, & Koyama Y (2019). Dual Roles of Astrocyte-Derived Factors in Regulation of Blood-Brain Barrier Function after Brain Damage. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(3), 571. 10.3390/ijms20030571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolić A, van Klaveren D, Groeniger JO, Wiegers EJA, Lingsma HF, Zeldovich M, von Steinbüchel N, Maas AIR, Roeters Van Lennep JE, & Polinder S (2021). Differences between Men and Women in Treatment and Outcome after Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 38(2), 235–251. 10.1089/NEU.2020.7228/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/NEU.2020.7228_FIGURE6.JPEG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Ballester C, Santana N, Perez-Jimenez E, Viana R, Artigas F, & Sanz P (2019). In vivo glutamate clearance defects in a mouse model of Lafora disease. Experimental Neurology, 320, 112959. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.112959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawashiro H, Messing A, Azzam N, & Brenner M (1998). Mice lacking GFAP are hypersensitive to traumatic cerebrospinal injury. NeuroReport, 9(8), 1691–1696. 10.1097/00001756-199806010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA (2015). Glial cell regulation of neuronal activity and blood flow in the retina by release of gliotransmitters. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1672), 1–9. 10.1098/RSTB.2014.0195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols JN, Deshane AS, Niedzielko TL, Smith CD, & Floyd CL (2016). Greater neurobehavioral deficits occur in adult mice after repeated, as compared to single, mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). Behavioural Brain Research, 298, 111–124. 10.1016/J.BBR.2015.10.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberheim NA, Tian GF, Han X, Peng W, Takano T, Ransom B, & Nedergaard M (2008). Loss of astrocytic domain organization in the epileptic brain. J Neurosci, 28(13), 3264–3276. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4980-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlig S, ene Clavreul S, Thorwirth M, Simon-Ebert T, Bocchi R, Ulbricht S, Kannayian N, Rossner M, Sirko S, Smialowski P, Fischer-Sternjak J, & Götz M (2021). Molecular diversity of diencephalic astrocytes reveals adult astrogenesis regulated by Smad4. The EMBO Journal, 40(21), e107532. 10.15252/EMBJ.2020107532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen ML, & Sontheimer H (2008). Functional implications for Kir4.1 channels in glial biology: from K+ buffering to cell differentiation. Journal of Neurochemistry, 107(3), 589–601. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05615.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekny M, Johansson CB, Eliasson C, Stakeberg J, Wallén Å, Perlmann T, Lendahl U, Betsholtz C, Berthold C-H, & Frisén J (1999). Abnormal Reaction to Central Nervous System Injury in Mice Lacking Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein and Vimentin. Journal of Cell Biology, 145(3), 503–514. 10.1083/jcb.145.3.503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]