Abstract

The expression of biosynthetic genes in bacterial hosts can enable access to high-value compounds, for which appropriate molecular genetic tools are essential. Therefore, we developed a toolbox of modular vectors, which facilitate chromosomal gene integration and expression in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. To this end, we designed an integrative sequence, allowing customisation regarding the modes of integration (random, at attTn7, or into the 16S rRNA gene), promoters, antibiotic resistance markers as well as fluorescent proteins and enzymes as transcription reporters. We thus established a toolbox of vectors carrying integrative sequences, designated as pYT series, of which we present 27 ready-to-use variants along with a set of strains equipped with unique ‘landing pads’ for directing a pYT interposon into one specific copy of the 16S rRNA gene. We used genes of the well-described violacein biosynthesis as reporter to showcase random Tn5-based chromosomal integration leading to constitutive expression and production of violacein and deoxyviolacein. Deoxyviolacein was likewise produced after gene integration into the 16S rRNA gene of rrn operons. Integration in the attTn7 site was used to characterise the suitability of different inducible promoters and successive strain development for the metabolically challenging production of mono-rhamnolipids. Finally, to establish arcyriaflavin A production in P. putida for the first time, we compared different integration and expression modes, revealing integration at attTn7 and expression with NagR/PnagAa to be most suitable. In summary, the new toolbox can be utilised for the rapid generation of various types of P. putida expression and production strains.

Keywords: toolbox, chromosomal gene integration, synthetic biology, Pseudomonas putida, carbazoles, glycolipids

Customisation of gene expression cassettes enabled the production of deoxyviolacein, mono-rhamnolipids and arcyriaflavin A in Pseudomonas putida KT2440.

Introduction

Natural products represent a rich source for valuable chemical compounds. Heterologous expression of the respective biosynthetic genes is one key technology for studying the intriguing biochemical synthesis pathways or bioactivities of these natural products.

Aside from many other microbes (Ke and Yoshikuni 2020), the Gram-negative soil bacterium Pseudomonas putida has been established as a remarkable host for natural product biosynthesis (Loeschcke and Thies 2020, Weimer et al. 2020). While a truly wide range of applications has been reported, production of rhamnolipids and aromatic building blocks are counted to the most prominent ones (Loeschcke and Thies 2020, Schwanemann et al. 2020, Weimer et al. 2020). The bacterium's potential in this regard is linked to specific advantageous features, including simple cultivation, a versatile metabolism but low background of intrinsic natural products and a remarkable xenobiotic tolerance (Thorwall et al. 2020, Bitzenhofer et al. 2021). The strain KT2440 is, in addition, HV1 certified (Kampers, Volkers and Martins dos Santos 2019).

The rising number of studies in the field has shown that the cloning and expression strategy is decisive for the effectivity in the construction of expression strains. The previously common gene expression from plasmids typically requires the use of antibiotics and can come with growth defects and issues in the reproducibility of results (Mi et al. 2016, Cook et al. 2018). Therefore, integrative vectors, which are applicable in P. putida, have been built and multiple distinct tools targeting different integration sites have been established (Loeschcke and Thies 2020, Martin-Pascual et al. 2021). Here, the chosen site of integration might be a crucial factor to yield effective production strains. In previous studies, transposon integration at random chromosomal positions (Fu et al. 2008, Nikel and de Lorenzo 2013, Martínez-García et al. 2014, Domröse et al. 2017, Gemperlein et al. 2017, Thompson et al. 2020) or at the attTn7 site (Choi and Schweizer 2006, Zobel et al. 2015, Hernandez-Arranz et al. 2019, Bator et al. 2020), as well as gene integration at specific integration sites, which is realised by recombineering and rendered especially effective, e.g. by recombinases like RecET and aided by SacB, I-SceI or Cas9 (Elmore et al. 2017, Choi and Lee 2020, 2020, Cook et al. 2021), have emerged as particularly relevant. Among others, the ribosomal RNA encoding regions, have been identified as especially suitable for the integration and expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (Domröse et al. 2019, Otto et al. 2019, Nazareno, Acharya and Dumenyo 2021).

Modular concepts can facilitate effectivity in cloning procedures and minimise the effort for testing different strain construction strategies. Hence, the development of modular systems, which allow a standardised combination of DNA elements, represents a central aspect of the methodology in the field of Synthetic Biology and Biotechnology (Nora et al. 2019). The modularity of such systems can bring about full flexibility for the compilation of functional DNA ‘parts’, allowing re-usage of constructs and their effective usability upon exchange among researchers. The key concept implies that a variation of one component creates a new construct, but leaves the structure unimpaired in its changeability with regard to the same component or other components, thus retaining the construct's amenability to further changes.

In this sense, the design principles of the BioBrick standards were developed (Knight 2003), which have since accelerated research advances. Among others, the SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture) plasmid series in particular is widely applied by the Pseudomonas research community (Martínez-García et al. 2020, Schuster and Reisch 2021, Valenzuela-Ortega and French 2021). In this context, target sequence independent cloning methods emerged that facilitated the effective cloning of parts in the desired sequence. The use of type IIS restriction enzymes represents one option to introduce standard coupling sequences of DNA parts for effective gene cluster cloning from multiple parts (Engler, Kandzia and Marillonnet 2008, van Dolleweerd et al. 2018, Valenzuela-Ortega and French 2021). These endonucleases catalyse DNA hydrolysis adjacent to their recognition site and can thus generate freely defined overhangs at the ends of DNA fragments, which can be employed as couplers (Yan et al. 2018). Moreover, ligation-independent methods, like commercially available In-Fusion® cloning, which are based on the annealing of complementary ends of DNA fragments, likewise enables the assembly of individual parts with standard coupling sequences (Bird et al. 2014). In addition, yeast-mediated recombineering, which is also independent of endonuclease recognition sequences, has proven to be useful for the assembly of plasmid constructs carrying larger gene clusters (Montiel et al. 2015, Weihmann et al. 2020, Alam et al. 2021).

For P. putida in particular, a series of plasmids with standardised architecture have been established (Calero, Jensen and Nielsen 2016, Martínez-García et al. 2020). In addition, we report here a toolkit for the effective standardised and ligase-independent assembly as well as chromosomal integration of larger gene clusters via a mode of choice and their expression, which can be useful for production strain construction.

We aimed to construct a designated set of vectors as a versatile toolbox for the effective construction of P. putida expression strains, which facilitates standardised cloning procedures and offers different chromosomal integration methods (transposons Tn5 or Tn7, and rrn interposon). Applications are demonstrated by establishing different biosyntheses: we employed the well-described violacein biosynthesis, which has been commonly used as reporter pathway before, for the validation of constitutive expression via Tn5-mediated integration aiming to exploit strong host promoters, and expression via specifically targeted rrn interposon integration. For metabolically challenging rhamnolipid biosynthesis, tight control of expression has been described as crucial for strain stability, hence it appeared most suitable to validate inducible expression modules introduced by Tn7 integrative elements. Finally, we used arcyriaflavin A biosynthesis, which has not been introduced in P. putida before, to compare all three integration and expression modes to identify the most suitable procedure for this case. We thus present the construction of strains constitutively producing violaceins, optimisation of a rhamnolipid expression module and first-time construction of an arcyriaflavin A producing strain.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains and standard cultivation media

Escherichia coli strains DH5α (Grant et al. 1990) and S17-1 (Simon, Priefer and Pühler 1983) as well as P. putida KT2440 (Bagdasarian et al. 1981, Nelson et al. 2002) and derived strains (all P. putida strains used for expression studies are listed in Table S6) were cultivated in LB (lysogeny broth) medium (10 g L−1 tryptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 10 g L−1 NaCl, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) or in TB medium (Terrific broth, modified, Carl-Roth Karlsruhe, Germany: 12 g L−1 Casein, enzymatically digested, 24 g L−1 yeast extract, 9.4 g L−1 dipotassium phosphate, 2.2 g L−1 monopotassium phosphate, 4 mL L−1 glycerol). LB agar plates were prepared with 15 g L−1 Agar-Agar, Kobe I, Carl Roth®, Karlsruhe, Germany. If appropriate, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations [μg mL−1]: ampicillin (Ap), 100 (E. coli); kanamycin (Km), 50 (E. coli) or 25 (P. putida); streptomycin (Sm), 25 (E. coli); chloramphenicol (Cm), 25 (E. coli); gentamicin, 4 (E. coli) or 25 (P. putida); tetracycline, 10 (E. coli) or 50 (P. putida). Irgasan (25 μg mL−1) was exclusively supplemented to agar plates after conjugation. E. coli was cultivated at 37°C, P. putida at 30°C. If not specified otherwise, cell densities given as OD (optical density) refer to measurements of liquid cultures in a Spectrophotometer (Genesys 20, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using 1 mL samples in cuvettes with 1 cm path length.

General molecular genetic methods

Standard molecular genetic methods were basically conducted as described previously (Green and Sambrook 2012). After amplification in E. coli DH5α, plasmid DNA was isolated with the innuPREP Plasmid Mini Kit (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany). The DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Quiagen® GmbH, Hilden, Germany) was used to isolate genomic DNA of bacterial strains. We utilised restriction endonuclease enzymes and phosphatase FastAP (ThermoFisher Scientific GmbH, Walkham, USA), as well as I-SceI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, US) according to the instructions given by manufacturers. The innuPREP DOUBLEpure Kit (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) was used to purify DNA fragments. Commercial services were employed for the synthesis of oligonucleotide primers as well as the sequences ‘pYT_core’ and ‘16S landing site’, and moreover for sequencing of cloned vectors (Eurofins Genomics GmbH, Ebersberg, Germany). All used plasmids and oligonucleotides are listed in Tables S4 and S5.

Design of random DNA sequences

The YT_core sequence was generated in silico and obtained by gene synthesis. To create random DNA sequences as coupling regions for assembly cloning in pYT vectors, we used the Random DNA Sequence generator of the Sequence Manipulation Suite (Stothard 2000). In addition, we excluded canonical RBS sequences and used prediction tools to exclude promoters [BPROM, (Solovyev and Salamov 2011)], and terminators [ARNold (Naville et al. 2011)], that could interfere with gene expression. Sequences with start or stop codons were excluded or they were removed manually. The recognition sites of restriction endonucleases (I-PpoI, PI-SceI, AsiSI, EcoRI, I-SceI, MauBI, I-CeuI, SalI, PI-PspI, MluI, NcoI, XhoI, SacI, KpnI) were likewise excluded. Finally, the generated sequences were compared via BLASTN with the entire NCBI database and to each other to exclude similarity to known sequences to prevent unwanted recombination events.

Yeast recombinational cloning and in vitro cloning procedures

Specific cloning procedures for the construction of the ready-to-use pYT vector and strain sets (Table 1) are detailed in the supplementary material. In brief, yeast recombinational cloning was used for multiple cloning steps including the construction of the three basic vectors pYTRW010K_0 × 5, pYTRW020K_0Ti1, pYTSK00K_0 × 7 (as detailed in Fig. S2), and subsequently for the integration of biosynthesis, marker or reporter modules into these. To this end, pYT vectors were linearised by restriction endonuclease digestion with I-SceI (biosynthesis modules), MauBI (reporters) or SalI (markers), depending on the modules to be cloned, followed by dephosphorylation with FastAP. Respective DNA inserts were obtained by PCR, during which ca. 30 bp suitable homology arms were added (see Table S5). Promoter elements and rhamnolipid biosynthetic genes rhlAB were introduced in one reaction at the I-SceI site of the vector and therefore designed to overlap with each other. Preparation of competent cells of uracil auxotrophic Saccharomyces cerevisiae VL6-48 (ATCC® MYA-3666, LGC Standards GmbH, Wesel, Germany) (Kouprina et al. 1998, Noskov et al. 2002) and vector assembly by recombinational cloning was performed in the yeast cells as described before (Gietz and Schiestl 2007, Domröse et al. 2017, Weihmann et al. 2020). Yeast cultures were grown in 1 mL of SD-Ura medium to isolate assembled plasmids with the innuPREP Plasmid Mini-Kit according to the corresponding manual—with exception of cell lysis, which was performed by incubation of the cells with 200 U mL−1Arthrobacter luteus Lyticase (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) in the kit's resuspension buffer at 37°C for 2–5 h). For various cloning steps, including the integration of vio or reb biosynthetic genes, a promoter, reporters or markers in pYT vectors, the in vitro In-Fusion® HD cloning kit (Takara Bio. Inc., Kusatsu, Japan) was used, which facilitates the ligase-free assembly based on the annealing of complementary single-stranded 5' overhangs, which are generated by a 3' exonuclease. To this end, pYT vectors were linearised by digestion with the endonuclease I-SceI (or other nucleases as appropriate) and the DNA inserts were amplified by PCR using primers with 20 bp overhangs to other fragments or the linear pYT vector. The parts were combined for the assembly reaction as defined by the manufacturer. All PCR templates are summarised in Table S4.

Table 1.

Ready-to-use pYT vector and strain sets.

| pYT vector toolbox | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | Backbone resistance | Integrating resistance marker | Transcription reporter | Integration elements | Reference/GenBank ID |

| pYTRW10K_0 × 5 | KmR | - | - | Tn5 | This study/ON366562 |

| pYTRW07K_0G5 | KmR | GmR | - | Tn5 | This study/ON366565 |

| pYTRW08K_0C5 | KmR | CmR | - | Tn5 | This study/ON366564 |

| pYTRW09K_0T5 | KmR | TcR | - | Tn5 | This study/ON366563 |

| pYTRW11K_0S5 | KmR | SmR | - | Tn5 | This study/ON366561 |

| pYTRW13K_3G5 | KmR | GmR | mCherry | Tn5 | This study/ON366560 |

| pYTRW14K_7G5 | KmR | GmR | LacZ | Tn5 | This study/ON366559 |

| pYTRW15K_2G5 | KmR | GmR | mTagBFP2 | Tn5 | This study/ON366558 |

| pYTRW16K_1G5 | KmR | GmR | eYFP | Tn5 | This study/ON366557 |

| pYTRW17K_6G5 | KmR | GmR | PE-H | Tn5 | This study/ON366556 |

| pYTRW18K_3T5 | KmR | TcR | mCherry | Tn5 | This study/ON366555 |

| pYTRW20K_0Ti1 | KmR | TcR | - | LP-L/R | This study/ON366554 |

| pYTRW28K_0Ti1 | KmR | TcR | - | LP-L/R_SacB | This study/ON366549 |

| pYTRW21K_1Ti1 | KmR | TcR | eYFP | LP-L/R | This study/ON366553 |

| pYTRW26K_1Ti1 | KmR | TcR | eYFP | LP-L/R_SacB | This study/ON366551 |

| pYTRW22K_7Ti1 | KmR | TcR | LacZ | LP-L/R | This study/ON366552 |

| pYTRW27K_7Ti1 | KmR | TcR | LacZ | LP-L/R_SacB | This study/ON366550 |

| pYTSK00K_0 × 7 | KmR | - | - | Tn7 | This study/ON366548 |

| pYTSK01K_0G7 | KmR | GmR | - | Tn7 | Tiso et al. 2020/MT522186 |

| pYTSK02A_0G7 | ApR | GmR | - | Tn7 | This study/ON366547 |

| pYTSK31K_1G7 | KmR | GmR | eYFP | Tn7 | This study/ON366546 |

| pYTSK54K_7G7 | KmR | GmR | LacZ | Tn7 | This study/ON366545 |

| pYTSK55K_2G7 | KmR | GmR | mTagBFP2 | Tn7 | This study/ON366544 |

| pYTSK56K_3G7 | KmR | GmR | mCherry | Tn7 | This study/ON366543 |

| pYTSK58K_6G7 | KmR | GmR | PE-H | Tn7 | This study/ON366542 |

| pYTSK65K_8G7 | KmR | GmR | GUS | Tn7 | This study/ON366541 |

| pYTNB01K_1G7 | KmR | GmR | NagR/PnagAa-eYFP | Tn7 | This study/ON366566 |

| pSEVA512S-16S-pad | Vector carries the landing pad with GmR and homology arms to 16S genes | This study/ON366567 | |||

| Strains for pYT application | |||||

| Strain | Resistance | Characteristics | Reference | ||

| P. putida RW16SA | GmR | carries landing pad for pYT interposon in 16S gene of rrnA | This study | ||

| P. putida RW16SB | GmR | carries landing pad for pYT interposon in 16S gene of rrnB | This study | ||

| P. putida RW16SC | GmR | carries landing pad for pYT interposon in 16S gene of rrnC | This study | ||

| P. putida RW16SD | GmR | carries landing pad for pYT interposon in 16S gene of rrnD | This study | ||

| P. putida RW16SE | GmR | carries landing pad for pYT interposon in 16S gene of rrnE | This study | ||

| P. putida RW16SF | GmR | carries landing pad for pYT interposon in 16S gene of rrnF | This study | ||

| P. putida RW16SG | GmR | carries landing pad for pYT interposon in 16S gene of rrnG | This study | ||

Plasmid transfer and genomic integration in P. putida

Bacterial conjugation was used to transfer vectors to the P. putida KT2440 wild type or derivatives thereof. For standard mating, E. coli S17-1 was first transformed with the respective vector. The donor was then incubated together with the P. putida recipient for 5–16 h at 30°C in 200 μL of LB medium on a cellulose acetate membrane on LB-agar. The mixture was finally plated on LB-agar (supplemented with Irg and an appropriate antibiotic depending on the used construct) and incubated at 30°C overnight. After transfer of constructs for Tn5-based genomic integration in P. putida KT2440, clones carrying the transposon were selected with different antibiotics depending on the pYT marker. Clones expressing biosynthetic genes or reporter genes were selected on LB-agar based on specific phenotypes. For clones, which were further characterised in terms of metabolite production, loss of the KmR backbone resistance was verified by plating on accordingly supplemented agar to exclude spontaneous plasmid co-integration. For rrn integration, seven P. putida strains were constructed, each possessing an appropriate landing pad in one of the seven 16S genes. The landing pad cassette was obtained from commercial gene synthesis services, cloned into pSEVA512S and the resulting plasmid pSEVA512S-16S-pad was transferred to P. putida KT2440. Clones were selected on LB-agar with Gm/Irg, followed by replica-plating on Gm (landing pad marker) and Tc (vector backbone marker) to identify double crossover variants. PCR analyses with forward primers binding in the upstream region of individual rrn operons and a reverse primer binding in the GmR-conveying aacC1 gene, followed by sequencing of PCR products, identified seven strains (RW16-A to RW16S-G) with correct integration in the seven different 16S genes (see details in Fig. S3). For gene integration at the landing pads, appropriate pYT vectors were transferred to these strains via conjugation. Either, the conjugation mix was transferred in liquid LB medium containing Tc and 250 g L−1 sucrose for 2 days before a sample was plated on LB selection medium (Tc/Irg) containing 250 g L−1 sucrose to directly obtain single colonies resulting from a double crossover event. Alternatively, cells were plated and incubated on selection medium (Tc/Irg), before several single colonies were re-streaked on antibiotic-containing LB-agar and incubated overnight. For SacB-based counter-selection, single colonies from these plates were then streaked on YT agar plates (10 g L−1 yeast extract, 20 g L−1 tryptone, 250 g L−1 sucrose, and 36 g L−1 agar) containing 25% (w/V) sucrose and incubated for 2 days. Resulting colonies (about 10–100) were screened for Km (vector backbone marker) and Gm (landing pad marker) sensitivity (Elmore et al. 2017). Successful integration of the gene cluster was corroborated by PCR using forward primers, which bind in the upstream regions of rrn operons and reverse primers in the introduced biosynthetic vio genes. Successful integration of the Tn7 transposon into the attTn7 site was confirmed by colony PCR using previously established primers, which are designed to bind to the glmS region and Tn7 ends (Choi et al. 2005).

Detection of hydrolytic enzyme reporter activity

For qualitative detection of β-galactosidase (LacZ) or β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity in P. putida clones, strains were incubated on LB-agar supplemented with 40 mg L-1 X-Gal (5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-3-d-galactopyranoside; Sigma-Aldrich) or with 75 mg L-1 X-Gluc (5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-3-d-glucuronide; Sigma-Aldrich) (Horwitz et al. 1964, Frampton, Restaino and Blaszko 1988). Polyester hydrolase activity (PE-H) was detected on LB-agar containing 8.8 mL L−1 Impranil® DLN-SD (COVESTRO, Leverkusen, Germany) (Molitor et al. 2020). If appropriate, sodium salicylate in a final concentration of 5 mM and antibiotics were supplemented. For the quantitative determination of LacZ, GUS and PE-H activity in P. putida, assays with chromogenic substrates ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranosid) (Miller 1972, Weihmann et al. 2020), pNPG (p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronosid) (Cui et al. 2016) and pNP ester (here p-nitrophenyl-β-d-octanoat) (Bollinger et al. 2020) were used. For the ONPG assay, cell extracts were prepared following previously established protocols (Miller 1972, Weihmann et al. 2020) by mixing 10 μL samples of P. putida cultures with 390 μL of diluted Z-buffer; 25 μL chloroform and 25 μL Z-buffer were added, and the mix was incubated for 3 min at 30°C. For the ONPG assay, 400 μL ONPG substrate solution (0.8 mg L−1 in diluted Z-buffer) were added to the cell extract. The mixture was incubated for 2 min at 30°C. Afterwards, 400 μL stop solution (1 M Na2CO3) was added and cell debris was removed by centrifugation (22°C, 15 min, 3000 g). The o-nitrophenol absorption of the samples was finally measured at 420 nm in the microplate reader TECAN Infinite M1000 PRO (Tecan Deutschland GmbH, Crailsheim, Germany). To calculate β-galactosidase activities as Miller units, cell densities of the bacterial cultures (measured at 580 nm in the same device), were taken into account. To prepare the pNPG and pNPO assays, the cells were diluted 1:10 and pellets (1 min, 18 000 g) were suspended in 100 mM PBS (pH 6.8) or 100 mM KPi (pH 7.2) buffer containing 0.1 mg mL−1 polymixin B (incubation: 1 h, 37°C). For the pNPG assay, 50 μL substrate solution (PBS buffer containing 0.5 g L−1 pNPG (0.793 mM)) was added to 50 μL of the whole cell extract in a microtiter plate (incubation: 2 min, 37°C). The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL of stop solution (1 M Na2CO3). For the pNPO assay, 180 μL substrate solution (100 mM KPi-buffer containing 20 mM pNPO) was added to 20 μL of the whole cell extract in a microtiter plate. The p-nitrophenol absorption of samples at 410 nm was measured in the microplate reader, allowing calculation of β-glucuronidase and esterase activities in U mL−1. These were divided by the corresponding cell densities, also measured with the TECAN Infinite M1000 PRO at 580 nm.

Detection of fluorescence reporters

For qualitative detection of fluorescence reporters in P. putida, corresponding strains were streaked on LB-agar supplemented with salicylate (5 mM final concentration), if necessary, and incubated at 30°C overnight. Subsequently, fluorescence of eYFP and mCherry was documented on a Blue/Green LED transilluminator (Nippon Genetics Europe GmbH; 430–530 nm) and of mTagBFP2 on the CAMAG TLC® Visualizer 2 (CAMAG AG & Co. GmbH 366 nm).

For the determination of in vivo fluorescence intensity in the context of reporter validation, samples of P. putida expression cultures were pelleted (1 mL, 1 min, 18 000 g) and washed three times in 1 mL Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM; pH 8; 1 min; 18 000 g). For fluorescence measurements in a TECAN Infinite M1000 PRO, 200 μL of this suspension were transferred to microtiter plates (Greiner Bio-One International GmbH; MTP 96-well). The excitation and emission wavelengths were matched to the fluorescence reporters mTagBFP2 (λmaxEx = 399 nm, λmaxEm = 454 nm) (Subach et al. 2011), eYFP (λmaxEx = 513 nm; λmaxEm = 527 nm) (Spiess et al. 2005) and mCherry (λmaxEx = 587 nm; λmaxEm = 610 nm) (Shaner et al. 2004). In addition, the measured fluorescence intensities were divided by the corresponding cell densities, also measured with the TECAN Infinite M1000 PRO at 580 nm. In the context of rhamnolipid production, fluorescence of P. putida was measured in cultures grown in Flowerplates® (m2p-labs GmbH; Flowerplate® MTP-B) in a BioLector® I (m2p-labs GmbH) equipped with an eYFP filter module (λEx = 508 nm; λEm = 532 nm) and BioLection 2 software. For cell density normalisation of fluorescence, the biomass (measured as scattered light at 620 nm by the same instrument) was used.

Expression of violacein biosynthetic genes and product analysis

Precultures of P. putida strains carrying vio biosynthetic genes were inoculated in 0.8 mL TB medium and incubated overnight in FlowerPlates® at 30°C under constant shaking at 1400 rpm in a ThermoMixer® C (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). These cultures were used to inoculate main cultures in 0.8 mL TB to OD750 nm = 0.05 as starting cell density in FlowerPlates®. After shaking incubation (1400 rpm) of cultures at 30°C in a ThermoMixer® C or in a Biolector System (m2p-labs GmbH), cells from 500 μL culture were harvested for analysis of violacein production. Cell samples were extracted with 0.5 mL ethanol (p.a.) and crude extracts were cleared by centrifugation. For a qualitative determination of the composition of violaceins, 10 μL samples were subjected to HPLC-PDA analysis using an AccucoreTM C18 Column (50 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 μm particle size, 80 Å pores) equipped with a guard column filled with the same material (Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH, Walkham, USA) and previously developed methods (Sánchez et al. 2006, Lee et al. 2013, Domröse et al. 2017). The column oven temperature was set to 30°C, and the flow rate to 1 mL min−1. The mobile phase was composed of dH2O with 0.1% (V/V) formic acid (A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% (V/V) formic acid (B) and applied for gradient elution as previously described (Domröse et al. 2017). Peaks obtained in chromatograms (recorded at 600 nm) were evaluated regarding the retention times and PDA spectra, using previously published data for reference (Sánchez et al. 2006, Lee et al. 2013, Domröse et al. 2017) (violacein, 5.9 min, λmax = 374, 571 nm; deoxyviolacein, 6.3 min, λmax = 372, 562 nm; prodeoxyviolacein, 5.6 min, λmax = 418, 610 nm). To estimate violacein concentrations in crude extracts, the absorption at 575 nm was measured with a Spectrophotometer (Genesys 20, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using 1 mL 1:10 diluted samples. Accumulation of the typical violacein/deoxyviolacein mixture or (almost) exclusively deoxyviolacein was evaluated using the molar extinction coefficients of violacein (ε575 [M−1 cm−1] = 25 400) and deoxyviolacein (ε575 [M−1 cm−1] = 15 700), respectively (Rodrigues et al. 2012).

Expression of rhamnolipid biosynthetic genes and product analysis

Precultures of P. putida strains carrying rhamnolipid biosynthetic genes were prepared in 1 mL LB medium in FlowerPlates® at 30°C shaking at 1200 rpm in a ThermoMixer® C (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Main cultures in sterile 48-well FlowerPlates® were inoculated to an OD580 nm = 0.05 in 1.2 mL LB medium supplemented with 10 g L−1 glucose and appropriate antibiotics. They were incubated in a BioLector I system at 30°C shaking at 1200 rpm. If appropriate, inducers were added after 3.5 h to a final concentration of 10 mM (l-arabinose or l-rhamnose), 2 mM (sodium salicylate or d-mannitol), or 0.5 μM (anhydrotetracycline). After 24 h, 500 μL samples of the culture broth (cell-free) were taken, and 500 μL acetonitrile were added. After incubation at 4°C overnight and subsequent centrifugation (2 min, 11 000 g), the samples were filtrated (Phenex RC syringe filters, 0.2 μm, Ø 4 mm (Phenomenex, Torrance, USA). To determine rhamnolipid and HAA concentrations, 5 μL samples were subjected to HPLC-CAD analyses using previously developed methods (Behrens et al. 2016, Tiso et al. 2016). We employed a NUCLEODUR C18 Gravity column (150 × 4.6 mm, 3 μm particle size, 110 Å pores; Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany), a column oven temperature of 40°C, a flow rate of 1 mL min−1, and a mobile phase of acetonitrile (A) and ultra-pure water with 0.2% (V/V) formic acid (B), which were applied for gradient elution as previously described. The stated amounts of rhamnolipids represent the sum of all detectable congeners, which were quantified in samples using chromatographically purified compounds as references as previously described (Behrens et al. 2016) The main congeners showed signals at retention times of 9.4 min (C10-C10) and 7.1 min (Rha-C10-C10).

Expression of arcyriaflavin A biosynthetic genes and product analysis

Precultures were prepared for P. putida strains with rebODCP genes in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 10 mL LB medium and incubated at 30°C and 130 rpm for 16 h. Main cultures were inoculated from precultures in 10 mL LB medium to an optical density of OD580 nm = 0.05 using 100 mL flasks. Cells were cultivated at 30°C and 130 rpm for 4 h and were then supplemented with 1 mM l-trytophan (stock prepared in dH2O). Additionally, expression of arcyriaflavin A genes was induced with 2 mM sodium salicylate (stock prepared in 70% (V/V) EtOH) in the strain carrying the respective expression cassette in the attTn7 site. Cells were harvested after a total incubation time of 48 h by centrifugation for 15 min at 5000 rpm and 4°C. Arcyriaflavin A was extracted from the cell pellet with 1 mL ethanol (p.a.) and crude extracts were analysed by HPLC-PDA as described above for the other indolocarbazole (deoxy)violacein (Domröse et al. 2017). The arcyriaflavin A signal was assigned by comparative evaluation of retention times and PDA spectra (6.7 min, λmax = 282, 316 nm) with a reference (purity ≥98% (HPLC); Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, United Kingdom) (Fig. S6). Based on a calibration curve (0 to 0.33 mg mL−1), arcyriaflavin A titres were thus calculated from peaks areas obtained in the chromatograms recorded at 316 nm.

Analysis of rhl transcript levels

Pseudomonas putida cell material equivalent to OD580 nm = 2 in 1 mL was harvested after 6 h of cultivation by centrifugation. Total RNA isolation, DNase treatment, RT-qPCR as well as the data quality control (Bustin et al. 2009) and evaluation were performed as previously described (Tiso et al. 2020) using the primers PA-rhlB_fw RT and PA-rhlB_rv RT (Kõressaar et al. 2018). Copy numbers of rhlB transcript per OD were approximated based on the initially extracted total RNA from cells equivalent to OD580 nm = 2 in 1 mL. Quality control and calibration are shown in Fig. S7.

Results

Conceptualisation of the modular yTREX toolbox

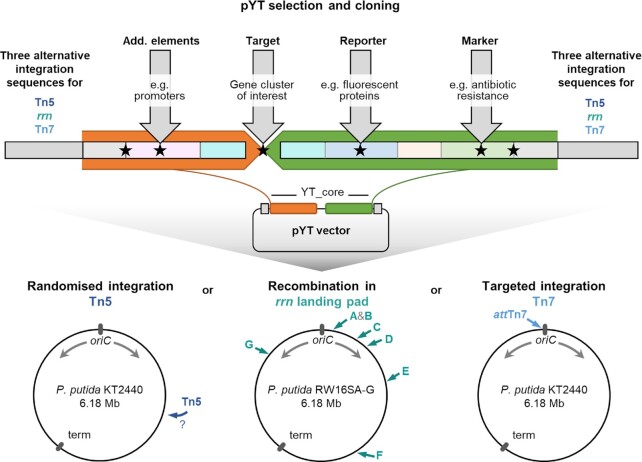

The production of valuable compounds can be implemented in microbial hosts by heterologous gene expression, for which the use of effective cloning technologies and chromosomal integration of expression cassettes represent key success factors. We therefore set out to construct a fully modular toolbox for the chromosomal integration of target genes or gene clusters in P. putida KT2440. We designed a DNA cassette that would chromosomally integrate in three different modes and allow addition or exchange of individual elements like target genes, promoters, transcription reporters or resistance markers via designated standard procedures (Fig. 1). To facilitate yeast recombineering and conjugational transfer from Escherichia coli to the host bacterium, we chose the integrative sequence to be carried in the yTREX vector backbone, which is equipped with respective genetic elements (Domröse et al. 2017). We denoted the toolbox as pYT vector series (YT for yTREX toolbox).

Figure 1.

Concept of the modular pYT vector series. First, a suitable vector from an existing library can be selected. Relevant elements defining the integrative YT_core sequence are depicted schematically. Details are given in Fig. S1. Orange and green regions denote sequences framing the gene cluster of interest, which is to be expressed. Vectors with different resistance markers, reporter genes and chromosomal integration modes are available. If necessary, adaptations for other required vector features can be made via standardised procedures. The integration of target genes of interest can be realised via conventional, ligase-independent or yeast recombinational cloning; positions of homing endonuclease recognition sites are indicated by black asterisks. Cloned vectors facilitate generation of expression strains via integration at different genomic positions (marked in the schematic representations of P. putida KT2440 chromosomes): Three vector series are available enabling random Tn5 transposition, recombination-based integration at pre-installed landing pads in one of the 16S rRNA-encoding genes of P. putida KT2440 rrn operons (denoted with A to G), and targeted transposon Tn7 integration at the attTn7 site.

Three chromosomal integration modes: The integrative sequence was defined by flanking elements that would convey chromosomal integration with the help of transposons or an interposon for both, untargeted or site-specific integration in genomic loci via transposition or homologous recombination (Fig. 1). The first option is the random transposon Tn5, which uses a ‘cut and paste’ mechanism and has evolved to low frequency genomic integration (Reznikoff 2008). This transposon requires only one tnp gene as well as the OE-L and OE-R (‘left’ and ‘right’ outer ends) for effective functioning. It therefore typically facilitates very robust gene delivery and can yield strains, in which target genes integrate downstream of a chromosomal promoter and biosynthesis is thus readily implemented (Martínez-García et al. 2014, Domröse et al. 2017, Nazareno, Acharya and Dumenyo 2021). The identification of such clones among all clones obtained after random transposition is dependent on effective screening methods like the use of transcription reporters that provide an easily detectable readout.

Previously, the use of transposon Tn5 led us to the identification of the P. putida ribosomal RNA (rRNA)-encoding genes (also: rrn operons or rDNA) as exceptionally suitable chromosomal loci for gene cluster integration and expression (Domröse et al. 2019). We therefore further aimed to facilitate direct rrn targeting via homologous recombination as a second option. The rRNA is encoded in seven rrn operons in P. putida KT2440, denoted with A, B, C, D, E, F, and G (Nelson et al. 2002, Belda et al. 2016). We chose to facilitate specific integration in one of these seven 16S rRNA genes, which are the first genes downstream of the respective rrn promoters, followed by 23S and 5S rRNA genes. Since the seven 16S gene sequences are 99.93–100% identical, targeting of a specific copy is ensured by pre-installation of unique sequences as ‘landing pads’ in each 16S gene.

The third option is the site-specific chromosomal integration of genes with the help of the Tn7 transposase (Peters and Craig 2001). The transposon Tn7, encoded by the genes tnsABCD and defined by the transposon outer ends integrates with high efficiency into the bacterial chromosome. Here, partner proteins direct integration into the attTn7 site. In P. putida KT2440 and many other bacteria, this site is located near the chromosomal origin of replication, so the genetic information is present at least in duplicate at most times of bacterial growth due to ongoing DNA replication (Slager and Veening 2016). The transposon Tn7 has been used in many studies for the fast generation of stable expression strains, for example, to allow comparison of promoter strengths or biosensor modules independent of chromosomal positioning effects (Choi et al. 2005, Choi and Schweizer 2006, Damron et al. 2013, Zobel et al. 2015).

The transposon-based options are in principle applicable in a variety of host bacteria since Tn5 integrates randomly and the attTn7 site occurs (mostly only once) in the genome of most bacteria because it is defined by being located adjacent to the essential glmS (glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase) gene (Peters and Craig 2001). These three integration modes define three different basic vectors of the pYT series.

Modular adaptability of the integrative sequence: The pYT vector series shall facilitate delivery of chosen genetic modules into the bacterial chromosome and is hence designed for straightforward adaptability. Within the borders of the integrating sequence, all elements of the cassette, which we denoted as YT_core, can be freely chosen or exchanged. This modularity is granted by restriction endonuclease and homing endonuclease recognition sequences that define ‘slots’, which are framed by randomised sequences (Fig. 1). Elements like target genes, transcription reporters or resistance markers can thus be inserted at these designated positions via restriction and ligation or via assembly of complementary strands in yeast recombinational cloning or methods like In-Fusion® cloning, for which the framing sequences next to the ‘slots’ are utilised as standardised recombination sites. This shall allow straightforward primer design for appropriate insert amplification and thus easy adaptation to the specific experimental requirements of various research questions: The central recognition site of homing endonuclease I-SceI facilitates vector linearisation for the integration of a gene cluster of interest at the cluster integration site (CIS, see Fig. S1 for details). By linearisation with AsiSI or PI-SceI, additional elements like promoters can be added upstream of the target genes. Hydrolysis at the sites for MauBI or I-CeuI enables the addition of a transcription reporter, linearisation at the sites for SalI or PI-PspI the inclusion of a resistance marker gene. We additionally included a set of common restriction sites as multiple cutter region (MluI, NcoI, XhoI, SacI, KpnI, and EcoRI). These endonuclease recognition sites do not occur within the majority of here used transcription reporter or resistance marker genes (encoding eYFP, mCherry, mTagBFP2, LacZ, GUS, PE-H, GmR, TcR, SmR, CmR, see Table S1). This allows cloning or an exchange of a resistance marker in a construct, in which a reporter has already been introduced, and vice versa in most cases. The homing endonuclease sites were additionally included to allow cloning or an exchange of elements in constructs already carrying larger target gene clusters, which may contain restriction sites within their sequences, or if new reporter or marker genes will be used, which contain such sites. Finally, the site for homing endonuclease I-PpoI allows transfer of fully ‘loaded’ YT_core cassettes between the three different vector types for integration via Tn5, Tn7 or into rrn genes.

Construction and validation of the pYT toolbox modules

Based on the vector designs conveying the three integration modes, three basic vectors were constructed. To this end, the YT_core sequence (Fig. S1), which was obtained as a gene synthesis fragment, was assembled with respective flanking sequences into the backbone of the yTREX vector, which replicates in E. coli with pMB1 ori to a mid copy number (Domröse et al. 2017). Cloning procedures are summarised in Fig. S2. In brief, pYT vectors conveying Tn5 transposition were equipped with the tnp gene and OE sequences of transposon Tn5. To facilitate integration in a 16S gene, we first introduced synthetic landing pad sequences in the P. putida KT2440 genome 630 bp downstream of the 16S promoter P1 (Domröse et al. 2019) by recombination, thus generating P. putida strains RW16SA, -B, -C, -D, -E, -F, and -G (carrying the landing pad in the 16S rRNA gene of the rrn operons A, B, C, D, E, F, or G, respectively) (Figure S3). In respective pYT vectors for gene integration at this position, 500 bp sequences homologous to landing pad sequences were added on each end of the YT_core. Vectors for gene delivery to attTn7 were equipped with the tnsABCD genes and OE sequences of transposon Tn7.

Making use of the standardised YT_core cloning slots for ligase-free module insertion (Fig. S1), different marker and reporter genes were cloned in the vectors (Table S2).

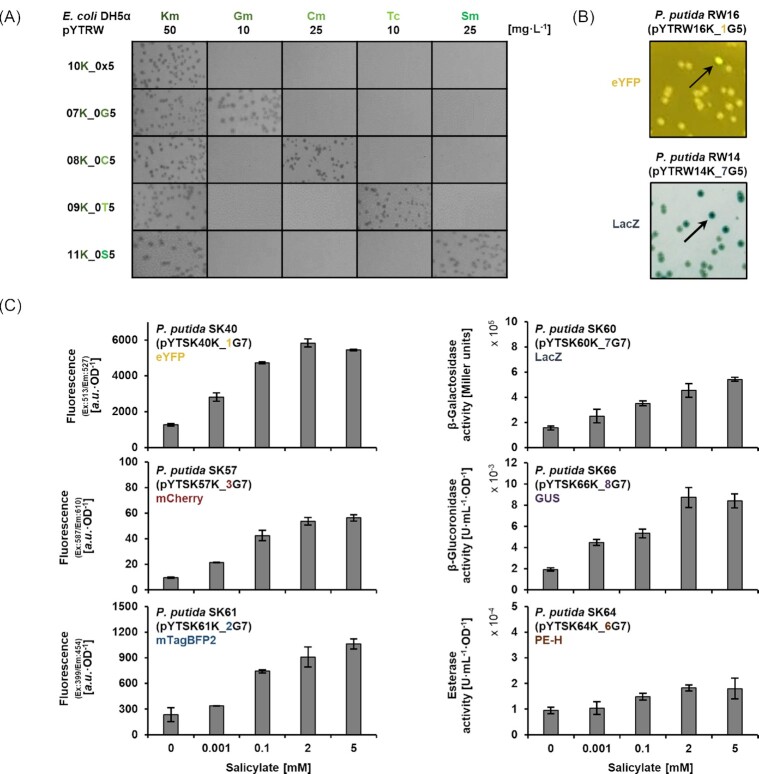

We verified the functionality of the chosen resistance marker genes, which were cloned together with the respective promoters to convey GmR, CmR, TcR, and SmR (Sutcliffe 1979, Prentki and Krisch 1984, Antoine and Locht 1992, Schweizer 1993) (Fig. 2A). The selection marker KmR was additionally included in the plasmid backbone to be used for the selection of E. coli clones which are grown for plasmid amplification to ensure they really maintain the replicative plasmid and not only carry the transposon or interposon in the chromosome. Further, we tested the applicability of selected reporter genes (eYFP and lacZ) to facilitate identification of expressing clones after Tn5 transposition (Fig. 2B). Further evaluation was performed using the fluorescent proteins eYFP, mCherry, and mTagBFP2, as well as the enzymes β-galactosidase (LacZ), β-glucuronidase (GUS), and polyester hydrolase (PE-H) (Miller 1972; Jefferson, Burgess and Hirsh 1986, Shaner et al. 2004, Spiess et al. 2005, Subach et al. 2011, Bollinger et al. 2020), after Tn7 transposition. In addition to qualitative evaluation of reporter expression after integration at attTn7 (Fig. S4), we validated the suitability of the established reporters for providing a quantitative read-out. To this end, the previously established nagR-PnagAa-PA_rhlAB cassette (consisting of mono-rhamnolipid biosynthetic genes under control of a salicylate-inducible promoter (Tiso et al. 2020)), was cloned in the I-SceI site of vectors, which were additionally equipped with different reporter genes. After integration into the P. putida KT2440 chromosome, a differential read-out over a wide range of inducer concentrations could be verified (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Functional validation of pYT marker and reporter modules. (A) Selective growth of E. coli DH5α cells after transformation with pYT vectors carrying different resistance markers. Marker gene indicating characters in vector names are highlighted. (B) Phenotypes of P. putida cells after random transposon Tn5 integration of pYT cassettes with different transcription reporters. Arrows indicate exemplary expressing clones. (C) Reporter signal quantified after differential salicylate induction of P. putida strains after integration of pYT cassettes at the attTn7 site. Reporter gene indicating characters in vector names are highlighted. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments with error bars indicating the corresponding standard deviations.

Therefore, a collection of 27 pYT vectors along with landing pad carrying strains for rrn integration was established as ready-to-use and easily expandable toolbox (Table 1). The cloning procedures are detailed in the supplementary information. All vectors and strains can be obtained from the authors upon request. The sequences were deposited at NCBI GenBank. The applied vector nomenclature, which includes the initials of the creator as well as a unique number and further indicates the plasmid backbone resistance (e.g. K for KmR), the reporter (e.g. 1 for eYFP), the marker (e.g. G for GmR) and the integration mode (e.g. 5 for Tn5) is explained in Table S3.

Constitutive expression of vio genes by Tn5 transposition and rrn-integration

The transposon Tn5 has been successfully used for integration and expression of multiple genes in various hosts including P. putida (de Lorenzo et al. 1998, Nikel and de Lorenzo 2013, Martínez-García et al. 2014, Domröse et al. 2017). To verify functionality of transposon Tn5 elements in the new vector setup of our present study, we used the well-described vio genes encoding the biosynthesis of violacein and deoxyviolacein. Accumulation of these violet pigments served as easy-to-detect reporter for expression tool development for P. putida before (Domröse et al. 2017, Choi et al. 2018). In our own previous work, random Tn5 transposition facilitated the integration of vio genes downstream of chromosomal promoters leading to metabolite production in a fraction of clones (Domröse et al. 2017). We therefore sought to benchmark the new setup against those previous findings on strain construction and violacein production.

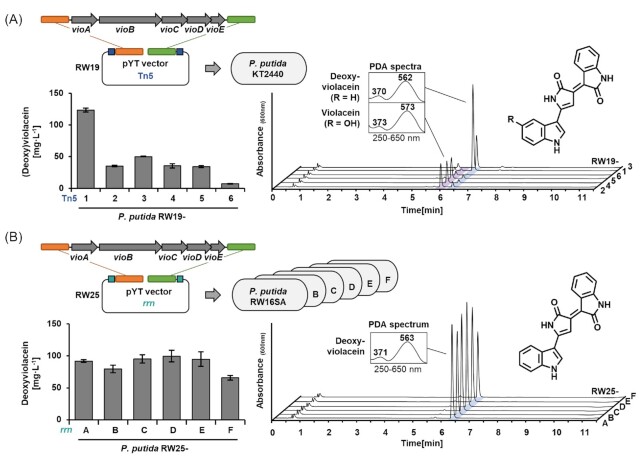

We selected the vector pYTRW09K_0T5, which carries TcR as integrating resistance marker. The genes vioA, vioB, vioC, vioD, vioE (7.3 kb) from Chromobacterium violaceum ATCC 12472 were PCR-amplified adding homologous cloning overhangs and assembled into the vector, which was linearised with I-SceI, by In-Fusion® cloning generating vector pYTRW19K_0T5_vioABCDE.

The vector was transferred into P. putida KT2440 by conjugation to insert vio genes in the chromosome via Tn5 transposition. Plating on Tc-containing agar plates yielded hundreds of clones, as we expected from previous work with the Tn5 transposon in the host (Domröse et al. 2017, 2019). Among these, about 15% exhibited a violet-blueish colour. Six selected clones designated as RW19-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, and -6 produced violacein and deoxyviolacein at titres between 10 and 123 mg L−1, as determined by established spectrophotometry and HPLC-PDA analysis (Domröse et al. 2017) (Fig. 3A). The (almost) exclusive production of deoxyviolacein in two clones was traced back to nucleotide deletions in the vioD-encoded oxygenase (Fig. S5). The titres are in the same range as previously obtained with the yTREX tool (Domröse et al. 2017). Therefore, the transposon Tn5 version of the pYT vector series is functional and suitable for rapid generation of recombinant expression strains.

Figure 3.

Violacein and deoxyviolacein production of P. putida after pYT-mediated vio gene integration via Tn5 transposition or into rrn operons. (A) Cloning scheme of pYT construct as well as product titres and corresponding HPLC-PDA analyses obtained after random transposon Tn5 integration of the vioABCDE gene cluster. (B) Cloning scheme of pYT construct as well as product titres and corresponding HPLC-PDA analyses obtained after interposon integration of vioABCDE into the landing pads within rrn operons of P. putida RW16SA-F. Biosynthesis of (deoxy)violacein was verified by HPLC-PDA analyses of extracts. PDA spectra of product peaks in chromatograms (recorded at 600 nm) are shown. Titres were estimated by spectrophotometrical measurements. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments with error bars indicating the corresponding standard deviations.

Targeted gene integration at defined positions was addressed as next step. The integration of biosynthetic genes in the P. putida rDNA was previously shown to promote high-level constitutive gene expression, especially in rrnA, rrnC, and rrnD (Domröse et al. 2019). To verify functionality of the pYT interposon elements for gene integration into P. putida rrn genes with pre-installed landing pads (see Fig. 2; Fig. S3), we again used the vio genes of C. violaceum. To assess the benefit of levansucrase-encoding sacB as counter selection marker (Gay et al. 1985), we cloned the genes vioABCDE in the I-SceI site of vector pYTRW21K_1Ti1 (without the sacB gene), yielding pYTRW24K_1Ti1, and also generated the analogous pYTRW25K_1Ti1 (with the sacB gene). Both vectors were equipped with the TcR integrating resistance marker.

The vectors were transferred into the landing pad-carrying P. putida RW16SA, -B, -C, -D, -E, -F, and -G by conjugation. After transfer of pYTRW024K_1Ti1 (without the sacB gene), plating on Tc-containing agar plates yielded several clones, among which, however, almost all tested clones showed resistance against Tc and Gm, which indicated single crossover integration. After transfer of pYTRW25K_1Ti1 (with the sacB gene), only 5–15 clones were obtained on Tc- and sucrose-containing agar plates. These showed a typical colour-phenotype of vio-expressing colonies. Further, they exhibited only resistance to Tc, but sensitivity to Gm, indicating a double crossover event that led to the intended deletion of the resistance cassette GmR at the landing pad. Finally, PCR analyses and sequencing confirmed that six strains carrying the vio genes in the 16S gene of rrnA, rrnB, rrnC, rrnD, rrnE, or rrnF could be obtained as expected. These were denoted as P. putida RW25-A, -B, -C, -D, -E, and -F. Despite several attempts, we were not able to integrate the vio genes in the rrn operon G. Notably, this rrn operon is in contrast to all others located on the (-) strand (Domröse et al. 2019). However, we have no hypothesis as to why gene cluster integration into this landing pad was unsuccessful, after the installation of the landing pad posed no difficulties.

The six strains produced deoxyviolacein at titres between 66 and 100 mg L−1, as determined spectrophotometrically and by HPLC-PDA analysis Fig. 3B. The production of deoxyviolacein was again caused by nucleotide deletions in the vioD-encoded oxygenase (Fig. S5). Since the vioD sequence on plasmids was intact, the deletions must have taken place during or after chromosomal integration. The specific occurrence of mutations in vioD—presumably upon expressions—suggests a distinct toxicity of violacein, which is not exerted by deoxyviolacein. Higher antibacterial activity of violacein compared to deoxyviolacein has been observed before (Wang et al. 2012). Since the MIC (minimal inhibitory concentration) of violacein has been described to be in the range of 18.5 mg L−1 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) (Subramaniam, Ravi and Sivasubramanian 2014) and 28.7 mg L−1 (E. coli) (Priya, Srinivasa and Mariappan 2018), growth of P. putida may be impaired at higher production titres. While the compound has previously been successfully produced in several heterologous hosts including P. putida (Fang et al. 2015, Domröse et al. 2017, Zhang et al. 2017, Choi et al. 2021), genetic instability of some E. coli and P. putida production strains was noted in this context (Sarovich and Pemberton 2007, Philip, Sarovich and Pemberton 2009, Domröse et al. 2017).

Taken together, our results suggest that violacein production is problematic, but the host P. putida is suitable for the constitutive and stable production of deoxyviolacein. Interestingly, the previously described clean deletion of vioD led to much lower titres of deoxyviolacein (10 and 21 mg L−1) (Domröse et al. 2017) compared to the here presented results, which might suggest a beneficial effect of partial gene deletion. The deoxyviolacein titres, which were obtained after use of the rDNA interposon, being in the range of the best producers after transposon Tn5 integration, corroborates the suitability of the rrn loci for gene integration and expression. Moreover, the tendencies of production-to-rrn operon correlation were similar to previous observations: While previously reported tendencies of lower production after integration in rrnB, rrnE, and rrnF (Domröse et al. 2019) are partly matched by violacein titres (rrnE does not match), the integration into rrnA, rrnC and rrnD, which previously led to highest pig gene expression and prodigiosin production (Domröse et al. 2019), was also especially suitable for violacein production. Therefore, the rDNA interposon version of the pYT vector series is functional and suitable for the generation of recombinant expression strains.

Optimisation of rhl expression modules at the attTn7 site

In previous studies, the transposon Tn7 has been applied to introduce genes reliably into the genome of different organisms. The introduction of genes in one defined chromosomal position is particularly suitable for comparative studies of expression modules (e.g. varying the promoter, the RBS, the biosynthetic or accessory genes). For rhamnolipids, the specific expression mode has already been shown to be important in the optimisation of production strains and can contribute to increasing production stability without loss of titres (Tiso et al. 2020, Sathesh-Prabu et al. 2021). We hence chose to apply our toolbox for the integration and expression of rhl genes encoding biosynthesis of rhamnolipids at the attTn7 site.

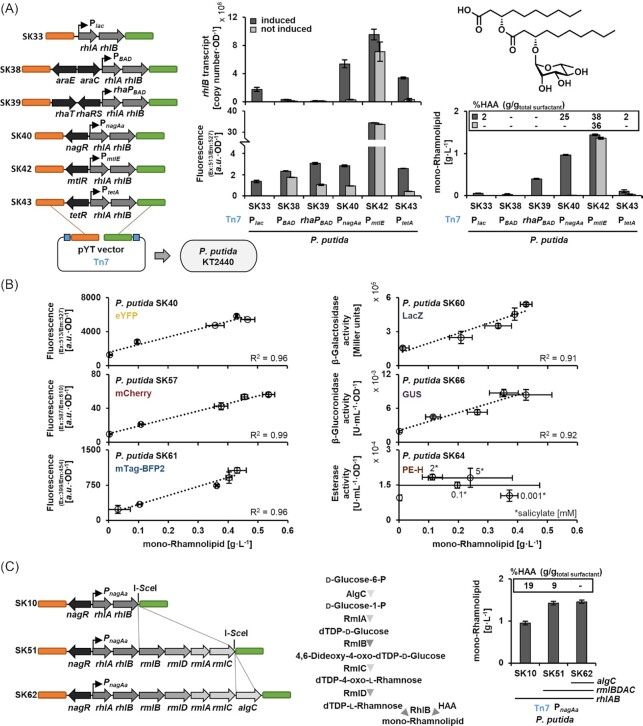

To compare different regulatory elements to drive the expression of the rhamnolipid biosynthetic genes rhlA and rhlB of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, they were assembled into pYT vectors along with a constitutive or one of five inducible promoters: Plac, araC-PBAD, rhaRS-rhaPBAD, nagR-PnagAa, mtlR-PmtlE, tetR-PtetA. The E. coli Plac of the lactose-inducible operon without its repressor gene lacI was chosen as constitutive expression system (de Lorenzo et al. 1993). The araC-PBAD module from E. coli was used to facilitate l-arabinose-inducible expression (Calero, Jensen and Nielsen 2016). The E. coli rhaRS-P rhaPBAD module was chosen for l-rhamnose-inducible expression (Calero, Jensen and Nielsen 2016). For these systems, the transporter genes araE and rhaT were additionally included under the control of the Ptac promoter to improve the transport of the inducers l-arabinose and l-rhamnose, respectively, into the cells (Calero, Jensen and Nielsen 2016). The PtetAfrom E. coli was used for anhydrotetracycline-inducible expression (Chai et al. 2012). The mtlR-PmtlE module from Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5 was chosen as d-mannitol-inducible system (Hoffmann and Altenbuchner 2015) and the nagR-PnagAa from Comamonas testosteroni for salicylate-inducible expression (Verhoef et al. 2010). All templates used for PCR amplification of the named elements are summarised in Table S4. The expression system modules and the genes rhlA and rhlB were assembled in the I-SceI-linearised vector pYTSK01K_0G7, which provides GmR as integrating marker, via in vivo recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae VL6-48. The BCD2 (BiCistronic Design) element, which consists of two Shine-Dalgarno sequences and a small leader peptide (Mutalik et al. 2013), was employed for translation initiation of rhlA and utilised as standardised cloning linkage between biosynthetic genes and expression system modules; accordingly, the respective sequence was integrated into corresponding oligonucleotide primers (Table S5). The resulting vectors (pYTSK03,08,09,10,12,13K_0G7) were subsequently equipped with the eYFP reporter gene (Aymoz et al. 2016), generating vectors pYTSK33,38,39,40,42,43K_1G7 which carry the promoters Plac, araC-PBAD, rhaRS-rhaPBAD, nagR-PnagAa, mtlR-PmtlE, and tetR-PTetA, respectively (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of different attTn7-integrated expression modules for rhamnolipid production in P. putida. (A) Cloning schemes of pYT constructs as well as rhlB transcript levels, eYFP reporter fluorescence, and titres of mono-rhamnolipids obtained after Tn7 integration and expression of rhlAB with different promoters. The fraction (g/g) of HAA per total surfactant, i.e. the sum of mono-rhamnolipids and HAA, is shown as inset. The commonly dominant C10-C10 mono-rhamnolipid congener is depicted. (B) Correlation of reporter signals (i.e. fluorescence or enzyme activity) and mono-rhamnolipid titres depending on different salicylate inducer concentrations in strains carrying rhlAB and reporter genes under control of nagR-PnagAa. Increasing salicylate concentrations (0, 0.001, 0.1, 2, and 5 mM) correspond to increasing mono-rhamnolipid titres with the exception of the PE-H-expressing strain (where salicylate concentrations are indicated for each data point). (C) Titre of mono-rhamnolipids and HAA fraction upon biosynthetic module expansion with rmlBDAC and algC genes for improved supply of the precursor dTDP-l-rhamnose to reduce HAA accumulation. Biosynthetic products were quantified by HPLC-CAD analyses. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments with error bars indicating the corresponding standard deviations.

The vectors were transferred into P. putida by conjugation resulting in high numbers of Gm-resistant clones. Integration of the recombinant transposon at the attTn7 site was verified by colony PCR using previously established primers (Choi et al. 2005) in all respective strains P. putida SK33, SK38, SK39, SK40 (Tiso et al. 2020), SK42, and SK43.

We comparatively assessed the performance of the strains with different expression system modules on the levels of transcription and expression as well as production. First, the transcription and expression levels of the biosynthetic operon rhlAB and downstream encoded eYFP reporter were determined by RT-qPCR as transcript copies of rhlB as well as via eYFP fluorescence (Fig. 4A). Stronger expression of rhlAB genes seemed to be accompanied by likewise higher eYFP fluorescence after 24 h, most prominently in case of the d-mannitol-inducible mtlR-PmtlE system (SK42), followed by the group of araC-PBAD, nagR-PnagAa and tetR-PtetA (SK38, SK40, and SK43). Finally, Plac showed weakest expression. Our findings of an overall correlation of the eYFP reporter fluorescence with rhlB transcript levels indicate the usefulness of the reporter. However, it should be noted, that both were determined as end point measurements: thus, putative dynamic underlying processes remain undiscovered. For example, the araC-PBAD and rhaRS-rhaPBAD-driven systems (SK38 and 39) yielded a fluorescence comparable to nagR-PnagAa, and tetR-PTetA (SK40 and SK43) despite a lower initial expression. Both parameters are generally influenced by different factors including posttranslational oxygen-dependent maturation of eYFP required for fluorescence, which can take significant time during fast bacterial growth (Drepper et al. 2007, 2010). Furthermore, RT-qPCR depicts an equilibrium of transcript levels at a given time and values are thus not only indicative of transcription strength but also result from previously discussed RNA degradation mechanisms (Pearson, Pesci and Iglewski 1997) that have not been fully elucidated for the natively adopted rhlAB operon from P. aeruginosa until now. Therefore, a correlation of reporter fluorescence and transcript levels should be interpreted cautiously.

Constitutive strong expression can be problematic for the stability of rhamnolipid production (Tiso et al. 2020). For a promoter system similar to the very strong mtlR-PmtlE (from the related Pseudomonas fluorescens DSM50106), a high basal expression in P. putida KT2440 has already been reported (Hoffmann and Altenbuchner 2015). We therefore also analysed expression under non-inducing conditions revealing a very high basal expression without addition of the inducer d-mannitol for strain SK42. Hence, the respective promoter system may not be attractive for production purposes.

To assess the promoters’ suitability for production, the supernatants of all cultures were analysed with regard to the achieved titres of mono-rhamnolipids and their aglycon precursor 3-(3-hydroxyalkanoyloxy) alkanoic acid (HAA), which typically accumulates as unwanted side product due to incomplete conversion, by established HPLC-CAD analysis (Tiso et al. 2020). Strains with Plac, araC-PBAD, and tetR-PTetA (SK33, SK38, and SK43) showed only low mono-rhamnolipid titres (ca. 0.02-0.1 g L−1), presumably because the expression of rhlAB is too weak. On the other hand, in the stronger nagR-PnagAa-based (SK40) and mtlR-PmtlE-based (SK42) expression strains, high mono-rhamnolipid titres of ca. 1 and 1.4 g L−1, respectively, were found. However, a large amount of the aglycon HAA (25%–38% (g/gtotal surfactant)) accumulated, especially in strain SK42 with mtlR-PmtlE. This may be due to a limited availability of the precursor dTDP-l-rhamnose, which is generated from the central carbon metabolism in P. putida, at times of strong expression. In summary, the salicylate-inducible promoter nagR-PnagAa facilitated strong gene expression with relatively low background without induction as well as relatively high mono-rhamnolipid production with lower levels of the aglycon intermediate, so we chose this promoter system for further studies.

To further elucidate the usefulness of the transcription reporters in our toolbox collection, we next analysed how the salicylate-induced production of rhamnolipids correlates with the output of different transcriptional reporters (eYFP, mCherry, mTagBFP2, LacZ, GUS, PE-H; see Fig. 2) at different induction strength. To this end, the respective pYT vectors were cloned by yeast-mediated recombineering of reporter genes into pYTSK10_0G7 (Tiso et al. 2020) and the P. putida strains SK57, SK61, SK60, SK66, and SK64 were constructed. Expression was induced during cultivation with different salicylate concentrations (0.001-5 mM), reporter fluorescence and enzyme activities were determined after 24 h and correlated with the mono-rhamnolipid titres for each inducer concentration (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, despite potential influences of chromophore maturation dynamics in GFP variants (Drepper et al. 2007, 2010) or the amplifying effect in enzyme-based assays (Iyer et al. 2001), the reporter signals (with the exception of PE-H) correlated remarkably well with the mono-rhamnolipid titres (R2 = 0.92–0.99). Only the PE-H activity does not correlate with product levels, which might be related to the enzyme's influence on the P. putida metabolism or even rhamnolipid stability. Our results indicate that tracking the expression of the rhlAB operon via transcriptional reporters could in principle provide an indication of mono-rhamnolipids production. However, the determination of the rhamnolipid titres should not solely be based on reporter readout; nevertheless, the use of transcriptional reporters is certainly a powerful tool to indicate expression levels and, in the presented case as well as in previous studies (Weihmann et al. 2020), it may serve to estimate product titres.

To finally showcase the utilisation and recycling of homing endonuclease site I-SceI for successive addition of expression modules, we chose to expand the rhl expression cassette by dTDP-l-rhamnose biosynthetic genes to reduce accumulation of the aglycon HAA and thus optimise nagR-PnagAa-based mono-rhamnolipid production (Fig. 4C). To this end, the P. aeruginosa genes encoding for the enzymes RmlA, B, C, and D and the phosphoglucomutase AlgC, which are required for the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to dTDP-l-rhamnose, were cloned downstream of the rhlAB genes in vector pYTSK10_0G7. In line with the toolbox concept of modularity, we could make use of the I-SceI site, which was not destroyed but recycled in the previous cloning step of rhl genes, multiple times. The resulting vectors pYTSK51_0G7 and pYTSK62_0G7 were used to generate strains P. putida SK51 (additionally equipped with rml genes) and SK62 (additionally equipped with rml genes and algC), respectively. These strains showed a reduced HAA level upon coexpression of rml genes and even complete conversion of HAA to mono-rhamnolipid upon additional algC coexpression, respectively, with a mono-rhamnolipid titre of 1.45 g L−1. Thus, a qualitative improvement in the production of mono-rhamnolipids by expression of associated genes could be achieved.

The here presented maximal titres of mono-rhamnolipids match previously reported levels, which were obtained under similar cultivation conditions with especially strong constitutive promoters (Tiso et al. 2020). However, the amount of unconverted HAA was massively decreased with the approach presented here. Since the delivery of reactants through the additional expression of heterologous genes has proven useful for an optimisation of biosynthetic flux and product titres in particular for P. putida and rhamnolipid biosynthesis but also beyond that (Cabrera-Valladares et al. 2006, Zhang et al. 2012, Sánchez-Pascuala et al. 2019, Troost et al. 2019), the demonstrated method of homing endonuclease I-SceI utilisation and recycling of the site can be helpful for various applications. Occurrence of this nuclease recognition site in biosynthetic genes is highly unlikely, so it can be used, recycled, and re-used for modular extensions multiple times. In summary, our toolbox facilitated the construction of different mono-rhamnolipid production strains, the identification of a most suitable promoter, evaluation of diverse transcription reporters, and the quantitative and qualitative optimisation of production.

Comparison of integration and expression modes for reb gene expression

Since the pYT series was proven applicable for all three integration modes (Tn5, rrn, Tn7), we aimed to challenge our toolbox with the expression of biosynthetic genes of a compound which has not been produced in P. putida before, and to investigate how different modes of expression affect production. For this purpose, the biosynthetic genes of the indolocarbazole arcyriaflavin A, which occurs in the rebeccamycin pathway (Sánchez et al. 2002, 2005), were chosen.

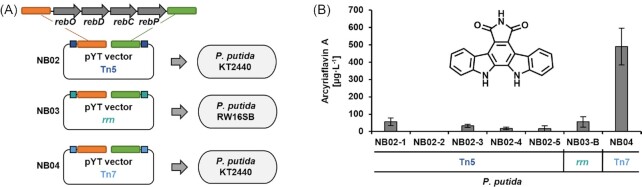

The genes rebO, rebD, rebC, and rebP (7.4 kb) derived from the actinomycete Lentzea aerocolonigenes (ATCC 39243) (Bush et al. 1987, Sánchez et al. 2006) were integrated via In-Fusion® cloning into the I-SceI-linearised pYT vectors pYTRW18K_3T5 and pYTRW26K_1Ti1 for Tn5 transposition and integration into the 16S rRNA genes, respectively. As nagR-PnagAa was favourable for rhamnolipid production, we equipped vector pYTSK31K_1G7, which carries Tn7 elements, with this expression system module using the AsiSI site of the YT_core sequence (Fig. S1). In the resulting vector pYTNB01K_1G7, the promoter is placed upstream of the I-SceI site, therefore allowing integration of a gene cluster here with suitable homology arms to the upstream and downstream sequences (CIS_up/dn). Hence, the same PCR product used for reb gene integration in the other two pYT vectors, could now be used for this third version (Fig. 5A). The resulting vectors pYTNB02K_3T5, pYTNB03K_1Ti1, and pYTNB04K_1G7 were transferred into the P. putida KT2440 wild type or strains RW-16SA-G carrying the landing pad in 16S rRNA genes by conjugation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of different gene integration and expression modes for the production of arcyriaflavin A in P. putida. (A) Cloning schemes of pYT constructs facilitating different integration and expression modes of the arcyriaflavin A biosynthetic genes rebODCP in P. putida. (B) Arcyriaflavin A titres quantified by HPLC-PDA analyses of crude cell extracts using commercial arcyriaflavin A as reference. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments with error bars indicating the corresponding standard deviations.

Interestingly, the implementation of a constitutive rebODCP gene expression by Tn5 transposition was more difficult than for violacein production. Here, conjugational transfer of pYTNB02K_3T5 had to be performed several times to obtain 100 to 200 clones. In contrast to the identification of strains readily expressing violacein biosynthetic genes after random transposition downstream of a chromosomal promoter, the expression of reb genes could not be visually detected by the formation of a colored biosynthetic product. Therefore, the clones obtained after conjugation were first analysed for mCherry reporter fluorescence under a Blue/Green transilluminator (λ = 450-530 nm). The mCherry fluorescence results from expression of the respective gene, which is located downstream of the reb genes as reporter for complete transcription of the rebODCP cluster. Based on the fluorescence signal, five clones (designated as P. putida KT2440 NB02-1,-2,-3,-4,-5) were finally selected for production studies. Moreover, with the rrn interposon, no double crossover integration could be identified in multiple attempts although counter selection using SacB was implemented, so that a clone with single crossover (in the 16S gene of rrnB; P. putida NB03-B) was selected for production studies. In contrast, a high number of clones with gene integration at attTn7 was obtained without difficulties, providing strain NB04.

Production of arcyriaflavin A was verified in all expression strains after cultivation in liquid medium (and induction with salicylate after an initial growth period in case of the NB04 strain carrying rebODCP under nagR-PnagAa control at the attTn7 site) by HPLC-PDA analysis using a commercial reference for comparison (Fig. S6). Compared with the other indolocarbazole, deoxyviolacein, which could be produced with high titres in Tn5- and rrn-based strains (more than 100 mg L−1), a constitutive expression in analogously constructed strains was apparently less appropriate for arcyriaflavin A production (titres of about 60 μg L−1) (Fig. 5B). The difficulties encountered in the construction of these two strains as well as their low production titres suggest that the constitutive production of arcyriaflavin A in P. putida is unfavourable. It is already known that arcyriaflavin A derivatives can act as antimicrobial compounds (Sánchez, Méndez and Salas 2006, Schmidt, Reddy and Knölker 2012). This is also supported by the fact that the production titre with the inducible system is eightfold higher. The calculated titre of about 500 μg L−1 (approximately 0.25 mg L−1 day−1) is comparable to concentrations of arcyriaflavin derivatives already achieved in E. coli (Hyun et al. 2003, Casini et al. 2018).

Thus, integration into the attTn7 site under control of the salicylate-inducible promoter nagR-PnagAa was found to be most suitable for the production of arcyriaflavin A. At present, the titres of the two l-tryptophan-derived indolocarbazoles deoxyviolacein and arcyriaflavin A cannot be expected to be in a comparable range since the oxidase RebO has a clear preference for 7-chloro-l-tryptophan, which is the native substrate of the rebeccamycin pathway (Nishizawa, Aldrich and Sherman 2005). However, results obtained for deoxyviolacein production indicate that P. putida should be metabolically equipped for future optimisation towards higher arcyriaflavin A titres. In summary, the construction of the different arcyriaflavin A production strains again demonstrated the usefulness of the toolbox presented in this work, in that standardised procedures facilitated comparative evaluation of different integration and expression modes without requiring a new cloning strategy for each case.

In conclusion, the presented ready-to-use series of pYT vectors enabled the efficient construction of secondary metabolite producing P. putida strains by transfer and activation of heterologous gene clusters. Its modular architecture allowed standardisation of experimental workflows and the straightforward construction of different strains in parallel, facilitating the selection of the most promising ones.

The toolbox described here complements the available set of tools for the transfer and genomic integration of genes for the construction of P. putida expression strains (Loeschcke and Thies 2020, Martin-Pascual et al. 2021). These comprise highly effective tools applying random transposition (Fu et al. 2008, Martínez-García et al. 2014, Domröse et al. 2017), or site-specific integration realised via transposase-, integrase- or recombination-based strategies to construct stable and controllable expression strains (Hernandez-Arranz et al. 2019, Bator et al. 2020, Choi and Lee 2020, Zhang et al. 2020, Cook et al. 2021). In contrast to the named specific toolsets, the yTREX toolbox, combines the utilisation of three different favorable modes of genomic integration for biosynthesis gene clusters (Loeschcke and Thies 2020) with a fully modular design, which allows effective ligase-independent vector assembly (Domröse et al. 2017). The latter facilitates rapid construction of different strains and the exchange of modules between the toolbox vectors, thereby matching the current developments in synthetic Pseudomonas strain engineering towards standardised and modular genetic tools (de Lorenzo and Schmidt 2018, Martin-Pascual et al. 2021). Straightforward parallel cloning of different transposon or interposon constructs can be especially useful in recombinant production strain development. As illustrated here and in previous studies, the most promising locus for gene integration and mode of expression for a metabolic pathway cannot always be predicted beforehand (Domröse et al. 2015, Gießelmann et al. 2019, Tiso et al. 2020), so that only a comparative evaluation may help. In principle, the presented toolbox should be applicable with Gram-negative hosts other than P. putida for which protocols for conjugational transfer, Tn7 and Tn5 transposition are well established. The latter has been elegantly employed for the integration of landing pads to enable subsequent specific recombinational integration of biosynthetic gene clusters in diverse γ-Proteobacteria in an effective manner (Wang et al. 2019). The rrn integrative variant requires, of course, also the equipment of the target strain with landing pads. Notably, considering the high degree of conservation of 16S rRNA-encoding genes, the constructs used here to deliver landing pads to P. putida KT2440 should also be applicable in other Pseudomonas (Otto et al. 2019) and most probably in other Proteobacteria as well.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Sabrina Linden and Esther Knieps-Grünhagen for technical support.

Notes

equally contributed

Contributor Information

Robin Weihmann, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany; Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany.

Sonja Kubicki, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany; Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany.

Nora Lisa Bitzenhofer, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany.

Andreas Domröse, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany.

Isabel Bator, Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany; iAMB - Institute of Applied Microbiology, ABBt - Aachen Biology and Biotechnology, RWTH Aachen University, 52074 Aachen, Germany.

Lisa-Marie Kirschen, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany.

Franziska Kofler, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany.

Aileen Funk, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany.

Till Tiso, Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany; iAMB - Institute of Applied Microbiology, ABBt - Aachen Biology and Biotechnology, RWTH Aachen University, 52074 Aachen, Germany.

Lars M Blank, Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany; iAMB - Institute of Applied Microbiology, ABBt - Aachen Biology and Biotechnology, RWTH Aachen University, 52074 Aachen, Germany.

Karl-Erich Jaeger, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany; Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany; Institute of Bio-and Geosciences IBG 1: Biotechnology, Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany.

Thomas Drepper, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany; Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany.

Stephan Thies, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany; Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany.

Anita Loeschcke, Institute of Molecular Enzyme Technology, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf at Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52428 Jülich, Germany; Bioeconomy Science Center (BioSC), Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425 Jülich, Germany.

Conflicts of interest statement

None declared

Funding

RW, SK, IB and TT obtained grants from the Bioeconomy Science Center which is financially supported by the Ministry of Culture and Science within the framework of the NRW Strategieprojekt BioSC (No. 313/323‐400‐002 13). The Ministry for Culture and Science funded a scholarship for AD within the CLIB Graduate Cluster Biotechnology. This work was further supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research via the projects NO-STRESS (031B0852B, to NLB, ST, AL and KEJ), LipoBiocat (031B0837A, to ST and KEJ), and GlycoX (161B0866A, to ST, AL and KEJ). TT and LMB have been partially funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany´s Excellence Strategy—Exzellenzcluster 2186 „The Fuel Science Center‘ ID: 390919832.

References

- Alam K, Hao J, Zhang Yet al. Synthetic biology-inspired strategies and tools for engineering of microbial natural product biosynthetic pathways. Biotechnol Adv. 2021;49:107759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine R, Locht C.. Isolation and molecular characterization of a novel broad-host-range plasmid from Bordetella bronchiseptica with sequence similarities to plasmids from Gram-positive organisms. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1785–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aymoz D, Wosika V, Durandau Eet al. Real-time quantification of protein expression at the single-cell level via dynamic protein synthesis translocation reporters. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]