Abstract

Objective

To explore the experiences, needs and preferences of a group of parents regarding the parenting support received during prenatal and well-child care in the Portuguese National Health Service.

Design and setting

We undertook descriptive-interpretive qualitative research running multiple focus groups in Porto, Northern Portugal.

Participants, data collection and analysis

Purposive sampling was used between April and November 2018. Focus groups were conducted with 11 parents of a 0–3 years old with well-child visits done in primary care units. Thematic analysis was performed in a broadly inductive coding strategy and findings are reported in accordance with Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines.

Results

Three main themes were identified to describe parents’ experience when participating in their children’s healthcare: (1) logistics/delivery matter, including accessibility, organisation and provision of healthcare activities, unit setting and available equipment; (2) prenatal and well-child care: a relational place to communicate, with parents valuing a tripartite space for the baby, the family and the parent himself, where an available and caring health provider plays a major role and (3) parenting is challenging and looks for support, based on key points for providers to watch for and ask about, carefully explained and consensual among health providers.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into parents’ needs and healthcare practices that affect the parenting experience. To meet parents’ preferences, sensitive health providers should guarantee a relational place to communicate and person-centredness, accounting for the whole family system to support healthy parenting collaboratively. Future studies are warranted to further strengthen the knowledge in the field of a population-based approach for parenting support.

Keywords: primary care, qualitative research, community child health, preventive medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Parents were encouraged to speak about their deepest concerns and needs as experiential experts who have undergone being a parent in Portuguese National Health Service.

We involved multiple researchers with different professional and academic backgrounds in data collection and analysis, who maintained regular reflective discussions challenging preconceptions and interpretations.

Our mothers and fathers experienced different healthcare services (primary care, hospital, private practice) and had children of different ages, which allowed researchers to have a broader perspective of the parenting support experience.

Although this study was not designed to achieve data saturation as it was a qualitative study to inform the ‘Crescer em Grande!’ (CeG!) project, one of the main goals was to explore how parents experienced parenting support in healthcare, both positively and negatively, to find what they commonly valued, providing new insights, increasing its understanding and drive practical actions (as in CeG!).

Despite our intention to recruit a diverse sample, all participants had higher education, most had one only child and all children were healthy, which could limit the transferability of findings.

Introduction

Support for parenting is recognised as a family necessity and right, given the well-known importance of parenting in child development1 2 and the high level of demand of this task.3 4 This has implications for the well-being of each element of the family and the family system itself—a relevant elementary unit of societies’ organisation and emotional support5 6 in an increasingly changing world.

Therefore, parenting support should be a worldwide priority raising awareness of positive parenting among providers working with children and parents,7 especially in the early years, considering its relevance in shaping children’s future.8–10 From all community sectors where it can be carried out, healthcare plays a particular role given its reach to pregnant women, families and young children.11 Also, health providers are identified by parents as a valued and credible source for helping parents on parenting.12–14

Nevertheless, not all parents receive the recognised support needed when they feel overwhelmed, stressed or in making everyday decisions.15 16 Some report that important age-appropriate education topics (eg, discipline, toilet training) are not discussed with their child’s doctor.17 Parents seem to share a universal desire to improve their parenting skills and want more information18 and guidance from providers who know their child and situation.16 Furthermore, a significant proportion of parents underestimate the critical importance of the early years.12 19 When aware of this, the majority finds this notion both motivating and frightening to varying degrees.16

Over recent decades, global institutions and national guidelines have emphasised that child healthcare services should work in a child and family-centred approach which actively engages parents in care and interventions, where appropriate (eg, Council of Europe guidelines on child-friendly healthcare20). However, few have guidance for providers on how to support parents in the parenting role or even recognise its importance. More recently, research strongly suggests that families need to be supported in providing nurturing care for children to achieve their full potential.21 The newly developed Nurturing Care Framework stresses the importance of strengthening mainly health services, so they address the components of nurturing care (eg, responsive caregiving) in an integrated way,22 already recognised as essential to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals.23–25

In Portugal, recommendations on child healthcare also highlight a practice oriented towards family and psychosocial needs of children that must include preparation to parenting since pregnancy and throughout child development. It guides providers on how to assure a relation of trust with parents, which constitutes a model for the parental relationship with the child. As such, it advocates on planning interventions where health providers can support parenting and facilitate parent–child relations.26–28

While there is a good evidence mainly on targeted parenting interventions for parents or children with specific needs,29 30 there remains a paucity of literature on how to scale up and reach parents at large, reducing inequity in the provision of parenting support. To this end, we developed a universal family-centred parenting intervention based on the Touchpoints model31 32—‘Crescer em Grande!’ (CeG!) (‘Grow Big!’)—to support the transition process to parenthood and early infancy.33 We believe that the Touchpoints model with its developmental and relational framework enables the practice of parenting support in preventive and universal care plans to assist and empower each family, reinforcing their competence, well-being and the quality of their relationships that promote healthier child development. The CeG! intervention was thus designed to be implemented in a real-world setting, reaching pregnant women, families and young children, in a non-stigmatising context, as part of routine care, alongside well known and reliable family health providers—a set of characteristics gathered up in primary care (PC) services. The first step in succeeding a universal and systemic parenting support intervention delivered by PC providers calls for understanding the circumstances and views of each of those involved. Hence, we ran multiple focus groups to obtain feedback from parents, family physicians and nurses to inform the CeG! intervention—content, organisation and design on how it can be better delivered—to reach an improved final version. This study aims to explore the views and experiences, needs and preferences of a group of parents regarding the parenting support received during prenatal and well-child care in the Portuguese National Health Service (NHS).

Methods

The reporting of this study follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines.34

Study design and setting

Descriptive-interpretive qualitative research35 using focus groups was conducted to gain an insight into the experiences of parents with children under 3 years old when participating in their prenatal and well-child visits in the NHS. The study was performed in Porto, the second-largest city in the country, located in Northern Portugal. This region has great territorial diversity, with rural and urban areas side by side.

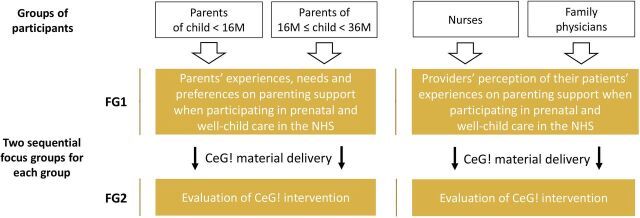

Parents’ focus groups are part of an overall multiple focus group study (figure 1) carried out with the different adult actors from prenatal and well-child visits of PC (parents, family physicians and nurses). Separate focus groups for parents and health providers were conducted so that participants had shared experiences of parenting and caregiving and would feel able to speak freely. Hence, two sequential focus groups (FG1 and FG2) were organised with each group as part of the wider study for the evaluation and final design of the CeG! intervention.33 This study reports results from the parents’ focus groups. Remaining findings will be presented elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the overall multiple focus group qualitative study. CeG!, Crescer em Grande!; FG, focus group; M, months; NHS, National Health Service.

Healthcare system in Portugal

Portugal has an NHS characterised as being universal and free, with health services delivered by health centres groups (including PC units) and hospital establishments. The first deliver primary healthcare to local communities; the latter provide mainly secondary healthcare.

Prenatal care is carried out together by primary and secondary care units: if no risk factors exist, it is performed in the PC units until about 36 weeks of pregnancy; after that, pregnant women begin their follow-up at the local hospital until delivery. After hospital discharge, the baby and mother resume healthcare in their local PC unit.27 28

Portugal also has private outpatient care and hospitals mainly focused on providing medical care to the health subsystems (special professional health schemes) and private health insurance schemes beneficiaries. Citizens can use the private practice only or along with the public health practice.

Research team

The research team was composed of six members (one man (CM) and five women), including three family physicians (FF, JV and CM) and three psychologists (MRX, HSR and FTdL), all with clinical experience with children and families. Three are parents themselves (FF, CM and JV). Four had training and experience in qualitative study designs (FF, MRX, HSR and FTdL). MRX and CM are faculty professors and researchers; FF is a PhD student and the principal investigator.

Prior to the study, based on existing knowledge, academic background and researchers’ experience, the research team’s vision was that parenting is challenging, and even families without evident psychosocial risk may experience difficulties in the parental task. Everyone working with children and families is integral to the childcare system and can support parenting. Part of the delivered parenting support should be universal and continuous, and the PC is a promising setting for that end, taking advantage of routine pre and postnatal visits.

Sampling and recruitment

We looked for participants (18 years or older) living in Northern Portugal who shared the experience of being parents while users of well-child visits in PC units, with at least one child under 3 years old. To gain multiple perspectives and thus richness of data, purposeful sampling concerning parents’ gender, diversity in number and age of children and residence location (corresponding to different PC units) was sought for. Potential participants were identified from the researchers’ social and professional network and recruited via one of the researchers (FF and MRX) who directly presented the study (by phone or face to face) or via an invitation letter (email) with a study information summary, clarifying all the doubts. Each contacted parent could also identify and suggest eligible participants from people they knew.

Parents with children of different ages were separated in two groups, as literature shows there are distinct parenting challenges throughout child development:4 less than 16 months for one group; between 16 months and 3 years old for the other (figure 1). We planned to include 5–8 participants per focus group as it seemed appropriate and manageable to generate a good discussion.

Data collection

Four focus groups were conducted between April and November 2018. The discussions were held at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa—Porto, in a quiet and comfortable room, with beverages and a light meal available. Before beginning each FG1, written informed consent and permission to audiorecord the focus group (to be deleted after anonymous transcription) were obtained. Parents also completed a sociodemographic questionnaire (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2022-066627supp001.pdf (84.4KB, pdf)

Two researchers (FF with qualitative training and MRX, an experienced facilitator) conducted the focus groups following a standardised protocol developed for the study.36 37 The researchers were known to a few participants but were not involved in their child’s care or their own. A third researcher was present to take field notes (HSR or SM).

Two semistructured topic guides were developed for FG1 and FG2, considering the previously described conceptual framework of the study, its specific objectives, and the professional experience of the researchers in supporting children, parents and families (box 1). The questions were developed to be non-prescriptive and open-ended; probes and follow-up questions were used to deepen responses. Previously to starting the focus groups, the sociodemographic questionnaire was tested, and guides were examined in a peer consultation (faculty researchers and masters students). Minor changes were deemed necessary, and there was good acceptance regarding clarity and ease of questionnaire completion, adequacy of the characteristics of the guides, and focus on the study objectives. Accordingly with relevant data collected at the first FG1, little adjustments were made in the FG2 topic guide to better focus the research questions.

Box 1. Overview of topic guides for parents’ focus groups*.

Parenting: parents’ meanings, valuable aspects and challenges

A practical example of a couple in love who waits for the birth of their first baby: What would you tell them about the experience of parenting that is starting? What has been most satisfying? And most demanding?

How is your family routine? What are the challenges? Where do you find support?

Value of prenatal and well-child visits in primary care

How was/is your experience in prenatal and well-child visits? What did you value the most?

What evaluation do you make of the practices that occur during these visits?

Role of primary care providers in parenting support

What role do family physicians and nurses play in your performance as a parent?

What do providers need to know about parents to support them better in parenting?

*Questions related to the aims of this study.

Each FG1 started with researchers summarising their personal motivations and goals, and carefully explaining the study purpose. Confidentiality and ‘no right or wrong answers’ was ensured. To feel at ease and minimise bias during the discussion process, non-judgemental listening was maintained, and comprehensible language was used. At the end of the focus groups, all participants were offered the opportunity to later add, via email, any comment or new idea to their shared experience; however, none made additional comments. The focus groups’ duration ranged approximately from 70 to 125 min (mean=108).

Data analysis

Four researchers (FF, FTdL, HSR and MRX) completed a broadly inductive thematic analysis,38 39 also informed by the study’s conceptual framework, and professional and academic background of analysts. Three of them were at the focus group meetings. All discussions were verbatim transcribed, and confidentiality was ensured using ID codes (FF). After setting up the material for analysis, each researcher (FF, FTdL, HSR and MRX) read all the transcripts at least once before beginning the entire coding/analysis process. Field notes were used to contextualise the data and inform interpretation. Close examination of the entire data set involved breaking down the data into smaller segments, tagging and naming them according to the content they present. Transcripts were coded over a lengthy period by FF, HSR and FTdL, who individually and sequentially reviewed different transcripts. Each coder systematically met with MRX (an experienced qualitative researcher) to check the interpretation of the emerging codes, eliminating redundancy and overlap. Any coding questions and differences that arose were analysed, discussed and resolved by consensus, trying out different variations to capture the meaning of parents’ experiences. The code structure was carefully revised and restructured several times after each switch to the new coder. After coding, the entire text was reread, and the coding frames were evaluated and refined, grouped under subthemes and themes with increasingly broader content (FF). Regular reflective meetings were held to discuss the interpretation of identified themes (FF and MRX).

During this iterative process, researchers maintained a reflective attitude of continuous questioning and writing, frequently reviewed the data from different participants’ perspectives and remained vigilant about their own. The final organisation and coherence of themes were reviewed by an independent researcher familiar with the phenomenon under study and by all analysts to examine the data analysis process and certify that codes and themes were correctly derived from the data.

Related to the concept of data richness, our aim was not to recruit participants until no new relevant knowledge was being obtained (data saturation) as these focus groups were mainly intended to bring Portuguese specific information to the CeG! intervention, considering our resources and time constraints.

Analysis was performed in Portuguese using NVivo V.1.5.1, and quotes were later translated into English by a bilingual speaker. Attention was given to ensure data validity in the translation of dialect and colloquialisms.

Patient and public involvement

Parents were not involved in the study design. However, some were also part of the peer meeting (faculty researchers and masters students) where the questionnaire and topic guides were reviewed. Peers were invited to reflect on the questions to be asked. Furthermore, participants involved in the multiple focus group study, their shared experiences, needs and preferences informed the development of the CeG! intervention. Findings from this study will be shared with participants via email through the published manuscripts.

Results

Of the approximately 30 people invited, 11 Portuguese parents of at least 1 child aged between 2 and 32 months were included in the study. Reasons for non-participation were as follows: schedule mismatch (the majority), acute disease of self or child (n=2) and not reachable (n=2). All recruited parents participated in both sequential focus groups (FG1+FG2) except one mother who missed FG2 due to personal constraints. The majority were parents of an only child, and one was a mother of two twin girls. There were no single parents, and two participants were themselves a couple. All participants had higher education, were employed and reported favourable economic conditions. They lived in various counties in northern Portugal, corresponding to different PC units. Regarding their youngest child, all participants took a childbirth course and stated their youngest was healthy. Complementary characteristics of participants are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the study participants

| Participants | N=11 (8 mothers, 3 fathers) |

| Age (years), n | mean 35 (range 30–42) |

| Under 34 | 5 |

| 35–40 | 5 |

| Above 40 | 1 |

| Residence county, n | |

| Gondomar | 4 |

| Porto | 4 |

| Braga | 1 |

| Maia | 1 |

| Matosinhos | 1 |

| No of children, n | |

| 1 | 8 |

| 2 | 3 |

| Youngest child age (months), n | N=12 (3 girls, 9 boys) |

| Under 12 | 4 |

| 12–23 | 4 |

| 24–36 | 4 |

| Prenatal care (youngest child), n | |

| NHS (primary care + hospital) | 7 |

| NHS (hospital) | 1 |

| NHS + private practice | 2 |

| Private practice | 2 |

| Well-child care (youngest child), n | |

| NHS (primary care) | 1 |

| NHS (primary care + hospital) | 2 |

| NHS (primary care) + private practice | 9 |

NHS, National Health Service.

Thematic analysis generated three specific themes: (1) logistics/delivery matter, with three subthemes: accessibility; organisation and provision of healthcare activities; unit setting and available equipment; (2) prenatal and well-child care: a relational place to communicate, with three subthemes: valued characteristics; tripartite space: baby, family and I; caring health provider, ‘the best thing that happened to me!’ and (3) parenting is challenging and looks for support, with three subthemes: key points for providers to watch for and ask about; ‘everyone’s got an opinion’; ‘explain us because we understand!’. Each is elaborated below, including illustrative quotes from participants taken directly from transcriptions, identified by a code number followed by the youngest child’s age (months). Complementary data extracts are presented in a supplemental table, by theme and subtheme (online supplemental file 2).

bmjopen-2022-066627supp002.pdf (131.1KB, pdf)

Theme 1. Logistics/delivery matter

The participants underlined how important it was to find diverse primary healthcare activities with specific organisational characteristics and adequate resources, mainly their accessibility. These aspects hold such relevance that, when lacking, motivated some participants to find a doctor in private practice.

Accessibility

Parents favoured easy access to the healthcare team (nurse and doctor) along the parenting path, which seems particularly relevant when problems or unsettling questions arise. In those situations—particularly in acute illness in children—the majority stressed the importance of doctors being reachable at any distance, anytime, by phone or email. Thereby, their problems can be assessed without always having to go outside. This reality was difficult to obtain in public healthcare, becoming a source of turmoil and sometimes a reason to turn to private practice. Parents reported that private paediatricians usually give them their own contact.

I thought: ‘I can call, but the front desk won’t pass the call to the family physician. Or I can send an email, and he'll eventually answer, but it’s…’ (…) the feeling that we can’t access the doctor directly unless you go there in person, can give us some restlessness. (mother5_14_14)

However, there were two cases where the PC nurse provided her personal contact, which proved very reassuring for parents. It allowed them to get the help they wanted when they needed it and enabled a gateway to the healthcare team.

The PC nurse gave me her personal contact; from then on whenever I had doubts, whenever I needed something: ‘Nurse, I need help’, and she helped me. (mother1_2)

Organisation and provision of healthcare activities

Considering the services delivered by PC, several parents treasured various proposals available pre and postnatally. How the healthcare was organised in different activities exceeded their expectations, some of which they did not even know existed. The childbirth course—held in groups for the pregnant couple, free of charge and organised by nurses—was described as one of the most significant in the transition to parenthood.

Yes, it exceeded [PC experience]! It was exceeded by the family physician, by the nurses, and childbirth course, which we also did. The gymnastics class that I had no idea they also have. And now the baby massage in the postpartum. Also visiting us at home. (mother5_14_14)

Parents also appreciated the team’s initiative, flexibility and coordination in scheduling healthcare encounters during pregnancy or after the baby is born, either at the units or home (eg, childbirth course, home visit). However, participants showed being aware of other parents’ not-so-good experiences with different PC teams.

The nurse came to my house… and even suggested: ‘Would you like me to have a look at the crib?’ ‘If you can, I'd really appreciate it’. (…) these are small situations that reinforce us psychologically. When I hear about negative [PC] experiences, it is this appropriate follow-up that I feel sorry for not all of us having access to. Why did it happen with my healthcare team then, and why doesn't it happen with the whole of the National Health Service with everyone? (mother4_28)

Indeed, some parents did not have this kind of follow-up, regretting that. One mother expressed feelings of abandonment and insecurity when the interconnectedness of care between public healthcare institutions (hospital and PC unit) failed, and right/proper follow-up was not guaranteed.

The baby was 1 month old—‘How do I introduce food?… I’m still having difficulties with breastfeeding; what do I do?’ (…) I wanted to leave with a list of: ‘You will have an appointment at 2 months, at 3, and so on; you will continue to be monitored here’, or someone could’ve asked me, ‘Do you want to continue to be followed here in the hospital’s maternity or you rather be monitored in the PC or do you prefer doing it in the private practice?’ And in the hospital’s maternity, I felt: ‘Ok, this phase is over for them here. (…) If I don't fit in anywhere else, I have no idea if the baby will be growing accordingly…’ (mother 8_8)

Regarding clinical visits, several parents found the duration to be short and insufficient for what they needed. Contrary to what the majority described as their experience, some valued the simultaneous presence of the family physician and nurse at well-child visits for reducing the time spent at the PC unit and optimising proper interaction with professionals. They argued that this avoids waiting between separate appointments, repeated clinical procedures and replicated information. Furthermore, some participants also favoured more frequent visits than those scheduled in the National Child and Youth Health Programme, underlining the need to monitor their children’s development more often and closely. Two mothers reported they had to look for a private paediatrician when they felt well-child visits were insufficient between 2 and 4 months old.

Unit setting and available equipment

Parents described their preference for a quiet, non-overcrowded environment while waiting for their appointments. Some did not have that experience at public healthcare units. They want to avoid dealing with long delays, which seem more difficult to tolerate in a packed room. Particularly in the case of children’s acute illness, parents reported that they were afraid to wait so long in such conditions, fearing that the baby would get worse.

At the PC unit, I could only go with a scheduled visit, right? There are always lots of people waiting. (mother8_8)

[The private office] Quieter also. (mother2_10)

Participants also discussed the importance of providers having adequate equipment for their work, underlying how its shortage—especially in prenatal care—limited professional performance and affected parents’ tranquillity given the uncertainty of their unborn baby’s health. Parents valued higher numbers of routine ultrasounds performed in the private practice during follow-up visits as a way of frequently seeing their baby. In turn, a portable fetal Doppler is usually used in PC visits to assess the baby’s heart rate, allowing parents to listen to the baby’s heartbeat. Some parents reported that the Doppler device was in poor condition, so they could barely hear anything.

Compared to my pregnant friends who were doing ultrasounds [in private practice], we see less, as far as I understand. They see; we can’t see anything. We always hope everything is Ok, don't we? We feel this insecurity when our friends say, ‘I saw something’ and we didn’t; the family physician asks us if everything is Ok. We believe that it is! [laughs] And we only do those 3 spaced ultrasounds, right? (mother2_10)

Theme 2. Prenatal and well-child care: a relational place to communicate

Parents reported expectations of how prenatal and child healthcare should offer personalised moments of sharing and support, with available time and space for each element of their family system, where health providers are called to play a decisive role. Relationships and fluid communication interaction between parents and providers were valued.

Valued characteristics

Parents described several positive and negative healthcare experiences, some in a rather emotional way, demonstrating that words, gestures or silences are meaningful and maintained in vivid memories. They specifically advocated the time of clinical visits as a space that should allow for a relationship to arise (rather than indifference) and a privileged place to dialogue without feeling the constant pressure of time. They want to feel secure, comforted and at ease to share what worries them to get the support they need and expect.

There [nurse triage at hospital], I had always the space to talk and ask questions. They also asked questions, and we communicated a lot. (…) I was also followed by a private obstetrician because my husband and I had this space to talk. My husband went, we talked, we asked questions, and we were there for quite some time because we had this communication, we had this opportunity to speak because in the hospital we didn’t. (mother1_2)

Then I started going to the hospital [for standard maternal care at the end of pregnancy] where we don't even have any relation, right? (…) and we feel a little bit like… we have to be there just because. They don't know who we are, don't make an effort, and don't even have time because they're 3 hours late… (mother2_10)

Tripartite space: baby, family and I

From the participants’ statements, it became clear that clinical visits need to account for three distinct domains, which must emerge with their own singular space and time. Parents pointed out there must be a space to talk about their baby, a space to talk about their family, but also a space to talk about themselves—‘I as a parent, I as a person’—in their singularity. They want to speak not only about their performance as parents, their experiences and challenges, but also about the person that exists beyond the parenting role. They do not want to feel like just another patient. Most parents could not feel that uniqueness, although they attempted to understand why this happened.

I think because they see it so often, they don't understand, I don’t know… As for me, I was confident, everything was going well, but a bit of detail was missing. You want to know about other things that perhaps because she [family physician] has always known me and knows that I'm confident, she does it always in a hurry. Being pregnant is normal for her, and she monitors 300 pregnant women, so… [laughs] I think it lacked a bit of ‘Ok, but in this situation, you're a different person’. It’s the first time, it’s a totally new situation that I was comfortable with, but I missed that care… I think she didn't think so because… I don’t know, it’s all so normal for her. (mother2_10)

Having more opportunities to talk about the family and themselves in the PC was one of the strengths recognised by several parents who attended both public and private practice.

I like going there [PC unit]. I feel that it’s a little bit more… It’s not only to see if the baby is Ok. (…) I think the family physician is super important for what involves the family. It is inevitable that with the family physician—I feel it more from the PC nurse—but even with the family physician, I end up talking about myself, the father, or our relationship more than with the paediatrician. I don’t talk much about myself with the paediatrician.’ (mother2_10)

Caring health provider, ‘the best thing that happened to me!’

Although participants described the presence of several family members as essential at the beginning of their parenting experience, they ascribed a particular and pivotal role to doctors and nurses in supporting good parenting.

It’s funny because when I came home from maternity, I found myself having difficulty breastfeeding (…). Where I got that support was with the nurse at the PC unit. (…) It was the best thing that happened to me! Even having my family close by—my mother by my side supporting me, my husband who also helps a lot with these matters, and my sisters—the nurse was the best thing that came into my life! (mother1_2)

Not everyone shared this enthusiasm about healthcare, and many participants had had negative experiences somewhere along the way. When speaking of those, they identified what they did not like to find—opposites of the qualities valued in the positive experiences. Parents ended up talking about what they commonly valued and they clarified how they expected to find a reliable professional who would listen, show interest and welcome each person. They expected openness and sensitivity, allowing them to share doubts, even the most peculiar, without fearing humiliation, guilt or censorship.

I think that what is lacking the health providers—not what is lacking, but what they should have—is time or availability, it depends on how we want to see it. But I think it’s being available above all. And before being available, showing interest in understanding, in getting to know that person. (mother3_15)

Paediatricians want to hear questions related to the child and not stupid questions. [laughs] Stupid. The first time we went to the paediatrician (…) the first question my wife asked, he replied, ‘I’m not going to answer that because I don't have time.’ And we just stared at him. ‘Alright, with your child you have to do this, this, and if you need anything else, let me know.’ Ok… short and direct. (father1_9)

At the same time, parents mentioned they do not expect validation of all they do but instead help in making decisions and alerting them when something needs to be in the child’s best interest. They emphasised how the idea of ‘the door is open for whatever you may need’ (mother3_15) reassures them along the way. This supportive role was considered essential by parents but understood as rare to find. Some acknowledged that it depends on the provider’s personality and attitude in wanting to understand what parents need: a ‘you either have it, or you don’t’. This made parents feel fortunate when finding an involved and caring professional.

Theme 3. Parenting is challenging and looks for support

Participants were clear and agreed that parenting is challenging and involves the family. They welcomed more support and timely work with the healthcare team, mainly regarding the child’s behaviour and peri-neonatal issues. In a world full of opinions, parents requested less discrepancy between the providers’ orientations and were grateful for respective updated and clear explanations.

Key points for providers to watch for and ask about

Parents claimed ‘there is no recipe’ (mother2_10) that can be transmitted but highlighted the need for guidance and support—showing it and observing it together—on parenting challenges and on family development, a role they expect health providers to fulfil. They stated that being pregnant and raising a child is not always rosy; people have fears and difficulties, which providers should know how to watch for in routine visits. Many are related to child’s behaviour, which concerns parents and are among the most complex to manage, as exemplified by mother3_15: ‘How will I handle the child’s behaviour?’. Despite recognising its importance, parents underlined that the doctor is not usually contacted to address these issues.

Weighing and measuring, Ok, gives you references of the child’s development, but it’s a little bit reductive, isn't it, of the experience not only of how the child is developing because it involves more than growing and gaining weight, but also of how that family is being built. Parenting is not just fireworks! And sometimes it’s difficult, difficulties come up, and I think they [health providers] also have to know how to help in these matters. (mother3_15)

Even though all participants attended childbirth courses and identified them as very significant in their knowledge, anticipation and preparation for essential areas of their newborn’s life (eg, childbirth, breastfeeding, baby’s routines), they reported that living the reality was quite different, with ‘a real baby that has no batteries, has a weight…’ (mother4_28). The experience of childbirth and the baby’s early times was described as tough moments of great demand and constant adaptation for which some parents hoped to be better prepared.

I wasn't expecting that the beginning would - at least for me - be so complicated. Because everything was very complicated. The birth, the breastfeeding… I cried for a month straight. (…) And I did all the childbirth classes anyway. I did everything anyway. I wasn't at all prepared. (mother7_27)

The main challenges experienced by parents in the first months of the baby’s life were dealing with sleeping, crying, new routines, return to work and childcare choices, and feeding their child. All mothers described breastfeeding as one of the most challenging and striking tasks in parenting, which puts them in a sensitive situation when they are particularly fragile, as breastfeeding is the responsibility of mothers.

Breastfeeding was a drama from the very start because I had a lot of difficulties and couldn’t do it. Now it’s better, but it’s still not 100%. It’s all-new! And I already knew this, but for me, it is complicated! That’s how I feel!’(mother1_2)

At some point, all participants described having felt ‘a huge pressure’ (father2_26) from health providers to breastfeed, ‘‘You have to breastfeed’, and was always that: ‘You have to breastfeed’’ (mother6_16), which worsen feelings of incompetence and guilt already present when facing breastfeeding difficulties. However, they also emphasised the importance of health providers in achieving successful breastfeeding. The timely availability and initiative to sensitively assist and guide one feed until success was considered determinant to unlock the breastfeeding process. Some parents did not receive the necessary support, so they believe that breastfeeding difficulties can be avoided, suggesting how to overcome the problem:

Maybe we—as new mothers—we need more support with breastfeeding. Ok, there are those breastfeeding groups, but it needs to be scheduled. From the day the baby is born, that person is responsible for that mother and will frequently do an assessment, or the mother will go daily or so, because it is not easy. (mother8_8)

‘Everyone’s got an opinion’

Parents were adamant regarding their parenting issues: ‘everyone’s got an opinion’ (father3_27), professionals and non-professionals. Regardless of the topic, they expressed that people (including family) often intensely defend their views without effective listening and temperance. This became more critical with health providers since parents complained about multiple and inconsistent opinions. Discrepancy quickly becomes a source of doubt and anxiety for parents who later do not know which path to choose and end up questioning their performance/competence.

At the PC unit, they advised me on a certain plan. But because I was left with doubts about the baby’s general wellbeing, I started going to the private sector. And that paediatrician told me: ‘Look, this vaccine should’ve been given already.’ And I was like… (…) I got different information, and I was having doubts. Am I doing the right thing? Am I doing the wrong thing? Am I harming him? (mother8_8)

One mother described the challenges of choosing a different option, consequently encountering negative attitudes from providers who had suggested something else.

The nurse, furious, comes and says: ‘But that’s not what we agreed on.’ (…) I replied: ‘But I just talked with the paediatrician, and we decided on something else. We will do it differently’. And she wouldn't accept it. In hospitals, doctors and nurses have their own very strong opinions. It is like when you’re trying to see a movie and someone comes by your ear talking about one thing and then comes another, and another! (…) Very difficult! (mother5_14_14)

‘Explain us because we understand!’

Parents valued and asked for providers' explanations and timely clarification of their doubts instead of just being advised on what to do. Providing information in advance and when appropriate to the family and circumstances gave greater tranquillity and confidence to face the challenges, which enabled informed decision-making.

When a paediatrician came (…) and said: ‘Look, using the cup increases the chance of her not accepting the breast; over the course of a full feed, the breast milk has different properties and, so, it is good that babies get it from the beginning till the end.’ Explain us because we understand! And so, we decided: ‘Let’s do it this way.’ (mother5_14_14)

Most participants stated that they got much information from the childbirth course, which supported them in getting prepared mainly for childbirth and the first months of the baby’s life. Some parents (particularly of older children) also underlined that they appreciate the explanation of the child’s typical development to better understand their children’s behaviour and the expected development for each age. So, they asked for more information than they currently receive and valued that from the healthcare team more highly than any other source of information.

(…) but offer a guidance for us to know (…) to try to understand what is normal, what isn’t [child’s behaviour], what we can at least try to do. I think that’s useful. (father3_27)

The majority enjoyed being given leaflets as they found them informative and reassuring. However, parents want them if previously discussed with the health providers. Some noted that leaflets’ information they do not understand and raise doubts could provoke feelings of anxiety and fear in parents. Despite having the necessity of being informed, several participants felt overwhelmed with so much information available nowadays, which blurred the line between valuable and undesirable information, making it harder to manage decision-making:

We don't know which way we should turn because we were flooded with an incredible amount of information. (father3_27)

Discussion

There is no single definition of parenting support as it is founded on a complex and wide-ranging phenomenon, but it can be described as ‘the provision of information and services aimed at strengthening parents’ knowledge, confidence and skills to help achieve the best outcomes for children and families’.40 Qualitative research, in its characteristics, brings specific advantages that allow exploring the subject.

This study contributed to a deeper understanding of parenting support needs from parents’ own experiences while using the NHS. As far as we know, it is the first to provide qualitative insight into what parents have found helpful or lacking in the support available during pre and postnatal care in Portugal. We found that parents value several characteristics of services and healthcare encounters, specific providers’ attitudes, and pertinent issues on parenting guidance, whose domains sometimes overlap. These findings point to the complex emotions and cognitions parents experience while raising their child and the individualised support needed.

The relational space of each healthcare encounter was assumed as the background where all the support and care occur. Parents consider it decisive for the success of the assistance provided. Having a ‘space to talk’ specifically in clinical visits was mentioned multiple times and described intensely in both positive and negative vivid examples. The desired confidence, comfort and non-judgement, the expected time, interest and availability, all characteristics recurrently reported,41–43 seem to take shape into what the space where care takes place must be. It also underlines which gestures, stances and behaviours health providers should intentionally choose to be adequate to that end. Despite different healthcare services available (hospital, PC unit, private practice), the distinct fields (prenatal and well-child care) and their independent exploration during focus groups, parents eloquently guided us to a common thread in parenting support, regardless of the healthcare system fragmentation. It is based on this relational space of good communication in which they value sharing—being listened to and having the opportunity to ask questions—support and preparation for the upcoming challenge. International studies have also identified these relational features as essential for the success of the experience of care and users' satisfaction and dignity.44–47

Consistent with previous research,42 we found that healthcare encounters should consider the needs of the entire family system, and that parents reject routine visits being limited to observing the baby’s or mother’s physical health. They argue that child development is ‘more than growing and gaining weight’, and as such, it is also necessary to monitor ‘how that family is being built’. This is particularly important in a rapidly changing modern world often embedded in a culture of excellence, where parents frequently miss support networks48 49 and previous experiences in childhood issues.50 Parents’ preferences are related to making room for each element of the system, including themselves, where their challenges and vulnerabilities are witnessed and ‘detail’ matters, allowing them to feel their uniqueness. This is aligned with the premise of a two-generational approach in which services planned to promote children’s development will be more effective when accompanied by parent-based services that foster positive effects on parenting.51

To this end, participants attribute health providers a relevant role with whom they had both adverse and positive experiences now imprinted on their minds. They lean on their sensitive and reassuring support along the parenting journey.13 41 52 They value their knowledge and prefer to resort to it, but they ask for individually tailored information—a core element of person-centred care—matching their needs, preferences and circumstances.47 53–55 Consistent with current research, they rely on their practical support41 46—through showing and observing things together—and clarified guidance consensual among professionals.56–58 Otherwise, it can become a source of anxiety and hinder the decision process. Indeed, as Brazelton noted: ‘If we, as supportive providers, can offer the necessary information and modelling for the parents to understand their young child’s development and to enhance it, we can play a crucial role towards the success of the family system’.59 Parents also have something to say about the most challenging things that providers should watch for and ask about in the transition to parenthood and the baby’s first months. The highlighted topics were in line with previous studies18 41 60–62 and are mainly related to breastfeeding and adapting to the baby’s early times, where parents usually felt insufficiently prepared for the new routines and the demanding multiple parental tasks. Behavioural topics were emphasised as ‘what concerns parents’, but there is a feeling that it is ‘no man’s land’. It seems there is no tradition of doing such talking during well-child care48 and ‘it does not justify’ calling the doctor because of such issues. However, parents voiced how they welcome parenting and behavioural care addressed in routine visits, as noted elsewhere,48 52 63 64 pointing out that access to parenting support throughout the child’s development is lacking.65 66

Particularly regarding the experience in PC, some parents were delighted with and even surprised about some available activities they were unaware of. Critically, they expressed concerns about not all Portuguese parents having this appropriate care, so they want the same quality of services available everywhere. Others felt that the NHS assistance was often insufficient and fragmented with poorly articulated institutions, so they looked for an alternative in private practice. Practical and structural barriers were indeed pointed out as relevant, especially in times of crisis when parents seek support and lack access to the healthcare team—such accessibility to PC is a well-known cornerstone to ensure equity in strong and sustainable health systems.67–69 Moreover, it seems a loss of opportunity not to take advantage of such stressor points as they are well-identified crucial moments to engage parents in support.70 Participants valued various modes of access (telephone, online, face to face) if timely matched. A practical, flexible and well-organised prenatal and postnatal care with a wide range of activities related to parenting, which assumes the initiative and happens in a quiet environment, was thus appreciated. A smaller spacing between well-child visits was desired by some parents whose healthcare experience seemed not to meet their needs, bringing insecurity and anxiety.

Lacking adequate equipment in PC was also an apparent obstacle to good performance of providers and even to parents’ tranquillity in the prenatal period. The impossibility of hearing the baby’s heartbeat through fetal Doppler was perceived to impact parents, on top of not having access to ultrasound in routine visits, as usually happens in private practice in Portugal. Such need for reassurance of the baby’s well-being is well-identified in antenatal ultrasound scan studies.71

This work presents rich data to guide providing the help parents say they want, which can improve prenatal and well-child care quality, system elements’ relations and overall well-being for healthier family functioning. The protective effect that positive parent–child relationship has on child’s development and performance in the future is well known.4 9 We believe that, of the multiple factors affecting this relationship, increasing parental confidence and satisfaction, and diminishing stress with the parenting role can be achieved when the parents’ needs are met. To reach it, clinical visits are pivotal opportunities, so it must be possible for parents to live them openly. Otherwise, they will leave a scheduled moment with a health provider without it being used to promote parental competence and empowerment, eventually jeopardising parents’ mental health—one of the major threats to early childhood development.22 In addition, this can also change their behaviour, as parents already reported that the fear of feeling judged makes it difficult to ask for help and support for their child if needed.12 72 Therefore, parenting support strategies should focus on overcoming identified barriers, privileging a good relational place to communicate and involving health providers to better comprehend the processes underlying parenting.

Strengths and limitations

Facilitators encouraged parents to speak about their deepest concerns and needs as experiential experts who have undergone being a parent in NHS services. Both had clinical experience working with families (a family physician and a clinical psychologist), which increased sensitivity to the phenomenon and allowed a favourable environment for parents' sharing. This was supported by practically total adherence to FG2, the long duration of focus groups and participants’ willingness to keep sharing beyond its ending. Although, despite using a semistructured topic guide to ensure open questions, the leading facilitator’s practice on prenatal and well-child care might have influenced how probes were used.

Another strength was also the variability of researchers (different professional and academic perspectives) involved in the analysis. Reflective discussions challenging preconceptions and interpretations were maintained. At the same time, each researcher maintained a reflective attitude on how their experiences and backgrounds have impacted on shaping their accounts.35 73 As it cannot be excluded the influence of investigator subjectivity, we outlined the researchers' backgrounds and the team’s beliefs to enhance the reader’s ability to evaluate the interpretation.

In addition to investigator triangulation, facilitators collected data from another four focus groups with family physicians and nurses, during the same period, as part of the wider qualitative study. Despite not being this study’s object of analysis, it allowed facilitators to spend prolonged time collecting data from different sources, which helped to gain insights into the research topic from multiple perspectives. At the same time, participation in two focus groups allowed parents to add any missing ideas and facilitators to clarify and deepen previous participants’ views. However, we could not conduct a participant-checking analysis. Still, to enhance the accuracy of our qualitative account, we used, as a final strategy, a peer debriefing by an ‘outside’ qualitative researcher also familiar with the central phenomenon being studied.73

Limitations of our study include the fact that it was not designed to achieve data saturation as it was a qualitative study to inform the CeG! project. We decided on broad inclusion criteria, yet our sample was not heterogeneous regarding socioeconomic status, other types of families (eg, single parent) and the number of children. Although data provided nicely detailed descriptions to generate and justify the results, a larger and diverse sample may have contributed to adding other perspectives. Moreover, few participants were known of the facilitators, and although there was an effort to frame the questions and structure the interview skilfully, it may have introduced desirability bias. Also, translating the verbatim to English may have risked a loss of meanings/concepts, given that the interviews were conducted in Portuguese.

Conclusion

Our findings provide evidence that parenting support is an essential but often neglected component of NHS prenatal and well-child care, according to a group of Portuguese parents of children under 3 years old. Participants described a relational place to communicate, person-centredness/uniqueness and accounting for the family system as fundamental to a good clinical visit. While parents believe there are ‘no parenting recipes’, they emphasised that accessible and caring health providers play a decisive role in supporting and clarifying concerns, having availability to listen and collaboratively observe and offer practical support. Parents highlighted the need for providers' consensual information because positions are sometimes multiple and extreme, entangling the decision-making process. The priorities identified here should be used to guide future parenting support research and clinical and educational initiatives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the parents who gave up their time participating in the focus groups and shared their experiences. The authors would also like to thank: Mariana Negrão, PhD, for the overall critical revision of the data analysis and quality appraisal; peer meeting elements, for the review of research instruments; Sara Moutinho, for supporting in the field notes; Patrícia Antunes, for participants’ quotes translation; Diana Bordalo, MD, for support in English revision; Ana Teresa Brito, PhD, and Bárbara Antunes, PhD, for assisting with manuscript final revision and English language readability appraisal, and Miguel Julião, MD, PhD, for his constant and unwavering support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @mgfamiliarnet

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. Supplementary Table has been graphically updated.

Contributors: Our study was coordinated and designed by FF with input from MRX and CM. FF and MRX conducted the focus groups. HSR contributed to data collection. Analysis was performed by FF, MRX, FTdL and HSR. JV assisted with literature review allowing the interpretation of data. The manuscript was drafted by FF with support from MRX. FF was responsible for incorporating important feedback into the manuscript and is the guarantor for this study. All authors provided critical input and revisions before approving the final version.

Funding: FF has a grant funded by national funds of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education (Portugal)—FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) grant: reference PD/BD/132860/2017, with an additional extension due to COVID pandemic: reference COVID/BD/151821/2020. The Nestlé Company (Portugal) sponsored the printing of the CeG! leaflets, as an unrestricted grant (grant number N/A). This article was supported by National Funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020).

Disclaimer: Funding sources had no role in the design or content of this study, its execution, data analyses or decision to submitted results.

Competing interests: FF is the author responsible for creating the project ‘Crescer em Grande!’; MRX is also involved in the development of CeG! and is member of the Administrative Board of the Fundação Brazelton/Gomes-Pedro para as Ciências do Bebé e da Família (Brazelton/Gomes-Pedro Foundation for the Sciences of Baby and Family), Portugal. FF and MRX are certified trainers in the Touchpoints Approach by Brazelton Touchpoints Center, Boston, USA.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Requests to access anonymised transcripts (in Portuguese) should be directed to the corresponding author (FF).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study approval was obtained by The Ethics Committee Centro Hospitalar São João/Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto (2017/11/27).

References

- 1. Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR. The importance of parenting during early childhood for school-age development. Dev Neuropsychol 2003;24:559–91. 10.1080/87565641.2003.9651911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bornstein MH. Handbook of parenting. In: Handbook of parenting: volume I: children and parenting. Third Edition: Taylor & Francis, 2019. 10.4324/9780429440847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Division of B . Parenting matters: supporting parents of children ages 0-8. Copyright 2016 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US), 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanders MR, Turner KMT. The importance of parenting in influencing the lives of children. In: Sanders MR, Morawska A, eds. Handbook of parenting and child development across the lifespan. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018: 3–26. 10.1007/978-3-319-94598-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. OECD . Doing better for families. 2011. 10.1787/9789264098732-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richardson D, Unicef OoRI . Key findings on families, family policy and the sustainable development goals. Synthesis report. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Council of Europe CoM . Recommendation Rec (2006) 19 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on policy to support positive parenting Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 13 December 2006 at the 983rd meeting ofthe Ministers’ Deputies. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012;129:e232–46. 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet 2017;389:77–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Scientific Council on the Developing C . Connecting the brain to the rest of the body: early childhood development and lifelong health are deeply intertwined. working paper 15: national scientific Council on the developing child. available from: center on the developing child at Harvard University. 50 church Street 4TH floor, Cambridge, MA 02138. Tel: 617-496-0578; Fax: 617-496-1229; E-mail: Developingchild@Harvard.Edu. 2020. Available: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/national-scientific-council-on-the-developing-child/

- 11. Richter LM, Daelmans B, Lombardi J, et al. Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet 2017;389:103–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31698-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beaver K, Knibbs S, Hobden S, et al. State of the nation: understanding public attitudes to the early years: UK. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rossiter C, Fowler C, Hesson A, et al. Australian parents' use of universal child and family health services: a consumer survey. Health Soc Care Community 2019;27:472–82. 10.1111/hsc.12667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kinsner K, Parlakian R, Sanchez GR, et al. Millennial connections: findings from ZERO TO THREE’s 2018 parent survey, executive summary. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Y, Sanders M, Feng W, et al. Using Epidemiological data to identify needs for child-rearing support among Chinese parents: a cross-sectional survey of parents of children aged 6 to 35 months in 15 Chinese cities. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1470. 10.1186/s12889-019-7635-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zero to Three . Tuning in: parents of young children tell us what they think, know and need. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halfon N, Inkelas M, Abrams M, et al. Quality of preventive health care for young children: strategies for improvement: the commonwealth fund. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Devolin M, Phelps D, Duhaney T, et al. Information and support needs among parents of young children in a region of Canada: a cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nurs 2013;30:193–201. 10.1111/phn.12002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. IPSOS . Understanding public attitudes to early childhood, key findings: royal foundation centre for early childhood. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Council of Europe CoM . Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child-friendly healthcare. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, et al. Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet 2017;389:91–102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization . Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential [The Spanish version is published by PAHO]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. Available: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/55218 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clark H, Coll-Seck AM, Banerjee A, et al. A future for the world’s children? A WHO-UNICEF-Lancet Commission. The Lancet 2020;395:605–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32540-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Black MM, Behrman JR, Daelmans B, et al. The principles of Nurturing care promote human capital and mitigate Adversities from Preconception through adolescence. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e004436. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanders MR, Divan G, Singhal M, et al. Scaling up parenting interventions is critical for attaining the sustainable development goals. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2022;53:941–52. 10.1007/s10578-021-01171-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Portugal. Direcção-Geral da Saúde DdSdPeSM . Promoção da saúde mental na gravidez e primeira infância: manual de orientação para profissionais de saúde. Lisboa: Direcção-Geral da Saúde DdSdPeSM, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Portugal. Direção-Geral da Saúde . In: Programa Nacional de Saúde Infantil e Juvenil. Lisboa: Direção-Geral da Saúde, 2013: 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Portugal. Direção-Geral da Saúde . In: Programa Nacional para a Vigilância da Gravidez de Baixo Risco. Lisboa: Direção-Geral da Saúde, 2015: 5–103. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jeong J, Franchett EE, Ramos de Oliveira CV, et al. Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003602. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barlow J, Coren E. The effectiveness of parenting programs: a review of Campbell reviews. Res Soc Work Pract 2017;28:99–102. 10.1177/1049731517725184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brazelton TB, Sparrow J. Nurturing children and families - building on the legacy of T. Berry Brazelton. Sussex: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sparrow J. Newborn behavior, parent-infant interaction, and developmental change processes: research roots of developmental, relational, and systems-theory-based practice. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 2013;26:180–5. 10.1111/jcap.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fareleira F, Xavier MR, Velte J, et al. Parenting, child development and primary Care-'Crescer em Grande!' intervention (Ceg!) based on the Touchpoints approach: a cluster-randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2021;11:e042043. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Elliott R, Timulak L. In: Essentials of descriptive-interpretive qualitative research: a generic approach. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2021. 10.1037/0000224-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bader GERCA. Focus groups: a step-by-step guide. San Diego, CA: The Bader Group, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krueger R. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Los Angeles: Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes AC, eds. Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise, 1st edn. Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ireland ,. Developing a national model of parenting support services: report on the findings of the public consultation. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hennessy M, Byrne M, Laws R, et al. They just need to come down a little bit to your level: A qualitative study of parents' views and experiences of early life interventions to promote healthy growth and associated Behaviours. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3605. 10.3390/ijerph17103605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nooteboom LA, Kuiper CHZ, Mulder E, et al. Correction: What do parents expect in the 21st century? A qualitative analysis of integrated youth care. Int J Integr Care 2020;20:17. 10.5334/ijic.5613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koschmann KS, Peden-McAlpine CJ, Chesney M, et al. Urban, low-income, African American parents' experiences and expectations of well-child care. J Pediatr Nurs 2021;60:24–30. 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jacobson N. A Taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2009;9:3. 10.1186/1472-698X-9-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karim RM, Abdullah MS, Rahman AM, et al. Identifying role of perceived quality and satisfaction on the utilization status of the community clinic services. BANGLADESH context. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:204. 10.1186/s12913-016-1461-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gilworth G, Milton S, Chater A, et al. Parents' expectations and experiences of the 6-week baby check: a qualitative study in primary care. BJGP Open 2020;4:bjgpopen20X101110. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines . Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2021, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Martins SP. Perceções de pais e profissionais de saúde dos apoios à parentalidade positiva. Um estudo das dimensões e determinantes das necessidades de apoio [Tese de doutoramento]. Universidade do Minho. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ulferts H. Why parenting matters for children in the 21st century. 2020. 10.1787/129a1a59-en [DOI]

- 50. Teti DM, Cole PM, Cabrera N, et al. Supporting parents: how six decades of parenting research can inform policy and best practice [social policy report 2017;30:1-34]. Social Policy Report 2017;30:1–34. 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2017.tb00090.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shonkoff JP, Fisher PA. Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Dev Psychopathol 2013;25:1635–53. 10.1017/S0954579413000813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moniz MH, O’Connell LK, Kauffman AD, et al. Perinatal preparation for effective parenting behaviors: A nationally representative survey of patient attitudes and preferences. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:298–305. 10.1007/s10995-015-1829-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision-making and Interpersonal behavior: evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:319–41. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information: exploring patients' preferences. JAMA 2009;302:195–7. 10.1001/jama.2009.984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jager M, de Zeeuw J, Tullius J, et al. Patient perspectives to inform a health literacy educational program: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:4300. 10.3390/ijerph16214300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hauck YL, Graham-Smith C, McInerney J, et al. Western Australian women’s perceptions of conflicting advice around breast feeding. Midwifery 2011;27:e156–62. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mattern E, Lohmann S, Ayerle GM. Experiences and wishes of women regarding systemic aspects of Midwifery care in Germany: a qualitative study with focus groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:389. 10.1186/s12884-017-1552-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Olander EK, Aquino MRJR, Chhoa C, et al. Women’s views of continuity of information provided during and after pregnancy: A qualitative interview study. Health Soc Care Community 2019;27:1214–23. 10.1111/hsc.12764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brazelton TB. How to help parents of young children: the Touchpoints model. J Perinatol 1999;19:S6–7. 10.1038/sj.jp.7200248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. das Neves Carvalho JM, Ribeiro Fonseca Gaspar MF, Ramos Cardoso AM. Challenges of motherhood in the voice of Primiparous mothers: initial difficulties. Invest Educ Enferm 2017;35:285–94. 10.17533/udea.iee.v35n3a05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McCarter D, MacLeod CE. What do women want? looking beyond patient satisfaction. Nurs Womens Health 2019;23:478–84. 10.1016/j.nwh.2019.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nan Y, Zhang J, Nisar A, et al. Professional support during the postpartum period: Primiparous mothers' views on professional services and their expectations, and barriers to utilizing professional help. BMC Preg Child 2020;20:402. 10.1186/s12884-020-03087-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Riley AR, Walker BL, Wilson AC, et al. Parents' consumer preferences for early childhood behavioral intervention in primary care. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2019;40:669–78. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Larson JJ, Lynch S, Tarver LB, et al. Do parents expect Pediatricians to pay attention to behavioral health. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2015;54:888–93. 10.1177/0009922815569199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sanders MR, Kirby JN. A public-health approach to improving parenting and promoting children’s well-being. Child Dev Perspect 2014;8:250–7. 10.1111/cdep.12086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Butler J, Gregg L, Calam R, et al. Parents' perceptions and experiences of parenting programmes: A systematic review and Metasynthesis of the qualitative literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2020;23:176–204. 10.1007/s10567-019-00307-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012:432892. 10.6064/2012/432892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. White F. Primary health care and public health: foundations of universal health systems. Med Princ Pract 2015;24:103–16. 10.1159/000370197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Corscadden L, Levesque JF, Lewis V, et al. Factors associated with multiple barriers to access to primary care: an international analysis. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:28. 10.1186/s12939-018-0740-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Geraghty R. Development of a National model of parenting support services - literature review: Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Moncrieff G, Finlayson K, Cordey S, et al. First and second trimester ultrasound in pregnancy: A systematic review and Metasynthesis of the views and experiences of pregnant women, partners, and health workers. PLoS ONE 2021;16:e0261096. 10.1371/journal.pone.0261096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ablewhite J, Kendrick D, Watson M, et al. The other side of the story - maternal perceptions of safety advice and information: a qualitative approach. Child Care Health Dev 2015;41:1106–13. 10.1111/cch.12224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Creswell JW. 30 essential skills for the qualitative. Researcher: SAGE Publications, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-066627supp001.pdf (84.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-066627supp002.pdf (131.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Requests to access anonymised transcripts (in Portuguese) should be directed to the corresponding author (FF).