Abstract

Background

The Medicare Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) program reimburses 90-day care episodes post-hospitalization. COPD is a leading cause of early readmissions making it a target for value-based payment reform.

Objective

Evaluate the financial impact of a COPD BPCI program.

Design, Participants, Interventions

A single-site retrospective observational study evaluated the impact of an evidence-based transitions of care program on episode costs and readmission rates, comparing patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations who received versus those who did not receive the intervention.

Main Measures

Mean episode costs and readmissions.

Key Results

Between October 2015 and September 2018, 132 received and 161 did not receive the program, respectively. Mean episode costs were below target for six out of eleven quarters for the intervention group, as opposed to only one out of twelve quarters for the control group. Overall, there were non-significant mean savings of $2551 (95% CI: − $811 to $5795) in episode costs relative to target costs for the intervention group, though results varied by index admission diagnosis-related group (DRG); there were additional costs of $4184 per episode for the least-complicated cohort (DRG 192), but savings of $1897 and $1753 for the most complicated index admissions (DRGs 191 and 190, respectively). A significant mean decrease of 0.24 readmissions per episode was observed in 90-day readmission rates for intervention relative to control. Readmissions and hospital discharges to skilled nursing facilities were factors of higher costs (mean increases of $9098 and $17,095 per episode respectively).

Conclusions

Our COPD BPCI program had a non-significant cost-saving effect, although sample size limited study power. The differential impact of the intervention by DRG suggests that targeting interventions to more clinically complex patients could increase the financial impact of the program. Further evaluations are needed to determine if our BPCI program decreased care variation and improved quality of care.

Primary Source of Funding

This research was supported by NIH NIA grant #5T35AG029795-12.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08249-6.

KEY WORDS: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, readmissions, quality of health care, bundled Payment Care Initiative, medicare

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 16 million Americans have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).1 Among individuals hospitalized for acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD), only one-third of patients receive care in accordance with guidelines from the American College of Physicians and the American College of Chest Physicians.2 Furthermore, approximately 20% of Medicare patients hospitalized for AECOPD are readmitted within 30 days post-discharge.3 Large geographic variations in this readmission rate led the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to classify many of these readmissions as preventable.4 Therefore, in 2014, CMS identified COPD as a condition with potential cost-savings and added this diagnosis to conditions assessed for financial penalties in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP).5 In addition, CMS pursued efforts to innovate care through the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) program.6 BPCI aims to increase the quality and value of care by stipulating that Medicare will reimburse for care episodes rather than individual fee-for-service claims,6 such that hospitals bear all post-acute care costs, regardless of where care is provided.

To address the HRRP penalty, in 2014, The University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) launched a pilot 30-day readmissions reduction program for patients admitted with AECOPD.7 When UCM began participating in model 2 of BPCI for COPD in 2015,8 the UCM COPD readmissions reduction program was extended from 30 to 90 days to align with BPCI episode duration and improve care coordination. This 3-year BPCI program sought to provide evidence-based transitions of care interventions including the inpatient and outpatient settings using an interprofessional team-based approach including9,10 advanced practice nurse(s) (APN) providing in-hospital consults and post-discharge follow-up ambulatory visits to standardize guideline-recommended care, nurse care manager(s) providing 48-h post-discharge care transition phone calls, pharmacy-led medication reconciliation,11,12 teach-to-goal inhaler education,13–15 and a “Meds to Beds” program providing prescribed medications prior to discharge (see Appendix A for more intervention details).16,17 The study objective was to evaluate effectiveness of the UCM COPD BPCI program at bringing episodic costs of care below the CMS-defined target price and at decreasing readmission rates relative to rates for patients during the same period who did not receive the program.

METHODS

Study Design and Subjects

This was a retrospective observational study evaluating the impact of the UCM COPD BPCI program on episode costs compared to CMS-determined target costs. The primary outcome was costs per episode, with a secondary outcome of readmission rates at 30, 60, and 90 days. A BPCI episode is defined as the index hospitalization through the 90-day post-discharge period for a given patient. Total episode costs are those billed to Medicare via Part A and B insurance claims within episodes, including claims for index hospital admissions, post-acute care, related outpatient services, and readmissions.8 Episode costs were evaluated relative to the CMS-determined target cost for each episode. Target costs are calculated quarterly per diagnosis-related group (DRG) by applying a 3% discount to 3 years of historical claims data, risk-adjusted using the hierarchical condition category framework.18 The population of interest was patients with CMS-determined COPD BPCI episodes with index hospitalizations of DRGs 190, 191, and 192 (COPD with major complication/comorbidity [MCC], COPD with complication/comorbidity [CC], COPD without CC/MCC, respectively).19 The asthma/bronchitis DRGs (202 and 203) were excluded from our study as the intervention focused on patients with hospitalizations for AECOPD.4 The study period was the UCM COPD BPCI program period from October 2015 to September 2018.20 This project was formally determined to be quality improvement, not human subjects research, and was therefore not overseen by the Institutional Review Board, per institutional policy.

Patients were identified for enrollment into the program daily (Monday through Friday) via electronic health record (EHR) screens of admitted patients performed by a non-clinical team member to identify inpatients likely admitted with AECOPD. This process included looking for qualifying symptoms or medications used to treat AECOPD among patients with diagnosed COPD. The clinical program APN(s) reviewed the screening list for inclusion in the program if their clinical assessment confirmed that the patient was admitted with or likely admitted with AECOPD. Upon completing the initial consult, the APN entered the patient into the EHR’s COPD registry. The intention was to treat all patients admitted for AECOPD; however, program delivery was limited by APN availability and screening process sensitivity. APN availability limitations were due to one of two factors. First, our inpatient consult program was limited to Monday through Friday, such that some patients admitted around the weekend may not have been able to be seen. Second, there were intermittent periods when there was no APN on the service (due to departures). With regard to screening process sensitivity, due to a lack of pathognomonic factors related to acute exacerbations of COPD, real-time identification of patients relied on clinical indicators. This process was imprecise such that some individuals were not identified during the screening process. The intervention and control populations were CMS-determined COPD BPCI patients who received or did not receive the program, as determined by presence/absence of APN inpatient consult notes, respectively. Because the two groups were not randomized, there is potential selection bias; as a robustness check, we performed an analysis comparing the intervention period (2015Q4–2018Q3) to a historical control period (2013Q4–2014Q3). Hereafter, “control group” refers to the contemporaneous comparison cohort while “historical control period” refers to the cohort in the control year.

Data Sources

The data sources, CMS episode- and claims-level data and internal administrative data, were joined on full name since no single unique identifier existed across datasets. Unique patients with the same name (determined by encrypted beneficiary ID [Medicare] or MRN [internal]) were excluded. The Medicare dataset includes total payments for all care during the episode and target costs for each episode; costs were not adjusted for inflation. The internal administrative data included demographics, smoking status, prescribed medications, length of stay (LOS), and procedures performed during index admission, lab values from index and readmissions, admitting diagnosis, discharge diagnosis, and time to readmission.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp; College Station, TX). All the analyses were exploratory due to potential existence of selection bias between the groups and at episode level by assuming independence in costs between episodes. Comparisons between groups utilized Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test for continuous data and Fisher’s exact or the chi-squared test for categorical data. To adjust for potential confounders, logistic, linear, and zero-inflated Poisson regressions were performed for binary, continuous, and count (i.e., number of readmissions) outcomes, respectively; independent variables were checked for multicollinearity. Potential confounding variables were preselected based on factors with a plausible relationship to the outcome variables and based on the limitations of our available datasets. Although it would have been ideal to include patient-level clinical history such as prior COPD exacerbations or hospitalization, these data were not available to us without performing a chart review, which was deemed to be infeasible for this analysis. Due to skewed cost data, the mean difference in costs and the linear regression model were bootstrapped, each with 20,000 replications, to estimate a 95% confidence interval (CI).21 All two-sided p-values < 0.05 were determined to be statistically significant. See Appendix B for more details.

RESULTS

There were 132 COPD episodes (101 unique patients) in the intervention group (received intervention), and 161 COPD episodes (144 unique patients) in the control group (did not receive intervention). The episode-level demographics were not significantly different in age, gender, or index DRG between the control and intervention groups. The groups were statistically different in race, smoking status, index admission year, and proportion of weekend stays (Table 1). We therefore adjusted for potential confounding effects of race, smoking status, and linear monthly time trends in our regression models.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics (n = episode level)

| Control | Intervention | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 161 | n = 132 | ||

| Median age at admission (year) | 70 | 73 | 0.2* |

| Race, n (%) | < 0.01† | ||

| Black | 126 (78.26) | 120 (90.91) | |

| Other‖ | 3 (1.86) | 2 (1.52) | |

| White | 32 (19.88) | 10 (7.58) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.7‡ | ||

| Female | 105 (65.22) | 83 (62.88) | |

| Index DRG, n (%) | 0.6† | ||

| 192 | 21 (13.04) | 17 (12.88) | |

| 191 | 73 (45.34) | 52 (39.39) | |

| 190 | 67 (41.61) | 63 (47.73) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | < 0.01† | ||

| Never | 17 (10.56) | 3 (2.27) | |

| Quit | 103 (63.98) | 98 (74.24) | |

| Yes (current) | 31 (19.25) | 29 (21.97) | |

| Not asked | 10 (6.21) | 2 (1.52) | |

| Year, n (%) | < 0.01† | ||

| 2015Q4 | 10 (6.21) | 15 (11.36) | |

| 2016 | 59 (36.65) | 55 (41.67) | |

| 2017 | 67 (41.61) | 24 (18.18) | |

| 2018 Q1–Q3 | 25 (15.53) | 38 (28.79) | |

| Weekend stay, n (%) | < 0.05§ | ||

| No | 153 (95.03) | 131 (99.24) | |

| Yes | 8 (4.97) | 1 (0.76) | |

P-value calculations were performed using *Wilcoxon rank-sum test, †Fisher’s exact test, ‡chi-squared test, and §1-sided Fisher’s exact test. ‖Race category of “Other” includes Asian, Hispanic, Other, and Unknown. ¶DRG codes: 192 is COPD W/O CC/MCC; 191 is COPD W CC; 190 is COPD W MCC

Cost Outcomes

The total episode costs were below total target costs for 6/11 versus 1/12 quarters for the intervention versus control groups (Table 2; Fig. 1). Median episode costs were below target every quarter for the intervention group versus 10/12 quarters for the control group. Overall, the control group had $2550.71 higher mean cost difference (net episode payment minus target cost) than the intervention group. The 95% confidence interval (by bootstrapping mean cost difference) was − $810.71 to $5795.14. In a bootstrapped linear regression model (Table 3), significant predictors of the difference between net episode payment and target cost were discharged home with home health (HH) or to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) and more readmissions (all of which correlated with fewer savings relative to target). Discharge to SNF was associated with a mean increase in episode cost of $17,095 relative to self-care; home health was associated with an increase of $2380 per episode. Each readmission was associated with a mean increased cost of $9098. For the reference index DRG of 192 (least complicated cohort), the intervention added a non-significant average cost of $4184 per episode relative to control episodes. However, relative to control episodes with DRGs of 191 or 190 (more clinically complex hospital courses), the intervention saved on average $1897 and $1753 per episode for index admissions with DRGs of 191 or 190, respectively.

Table 2.

Episode Costs Relative to Target Cost, By Quarter

| Quarter | Control | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean episode costΔ ($) | Median episode costΔ ($) | Episodes (n) | Mean episode costΔ ($) | Median episode costΔ ($) | Episodes (n) | |

| 2015Q4 | 1824.78 | − 3061.55 | 10 | − 1106.89 | − 3722.38 | 15 |

| 2016Q1 | 4406.32 | − 2970.84 | 18 | − 2444.01 | − 6156.50 | 13 |

| 2016Q2 | 3557.89 | − 2764.76 | 21 | − 2496.23 | − 6651.26 | 4 |

| 2016Q3 | 3273.93 | − 8573.30 | 11 | − 1932.50 | − 7348.57 | 17 |

| 2016Q4 | 1446.23 | 479.93 | 9 | − 55.79 | − 6520.07 | 21 |

| 2017Q1 | 5627.08 | − 1725.71 | 25 | 0 | ||

| 2017Q2 | 298.90 | − 4937.07 | 23 | − 7048.47 | − 7661.11 | 4 |

| 2017Q3 | 1577.21 | − 1788.45 | 13 | 2388.46 | − 6916.96 | 11 |

| 2017Q4 | − 2167.45 | − 7693.62 | 6 | 4362.69 | − 2529.74 | 9 |

| 2018Q1 | 756.77 | − 1037.46 | 11 | 2508.43 | − 2748.06 | 12 |

| 2018Q2 | 327.70 | − 802.68 | 7 | 3405.71 | − 5766.68 | 13 |

| 2018Q3 | 10,305.08 | 7204.44 | 7 | 1568.20 | − 723.56 | 13 |

Mean and median differences between net episode payment and target cost, by quarter. Cost delta is the episode cost minus the target cost. A negative value reflects an episode cost below target (black); a positive value reflects an episode cost above target (red). Episode costs are those billed to Medicare within a patient’s 90-day care episode, including claims for the index admission, post-acute care and related services, and any readmissions. Target cost is calculated by CMS on a DRG- and quarterly basis by applying a 3% discount to 3 years of historical claims data, risk-adjusted using the hierarchical condition category framework

Figure 1.

Episode costs by quarter. Legend: median (1A) and mean (1B) episode costs for AECOPD relative to BPCI target costs by quarter. Episode costs are those billed to Medicare within a patient’s 90-day care episode, including claims for the index admission, post-acute care and related services, and any readmissions. The target cost, calculated by CMS on a DRG- and quarterly basis, is shown as a weighted average based on the number of episodes in each DRG so as to show only one target line for each group per quarter. 1C shows the cost delta (mean episode cost minus the target cost) by quarter for the control and BPCI (intervention) groups.

Table 3.

Regression Analyses

| 90-day readmit count | Episode target delta | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 0.77 (0.25, 2.40) | 4183.87 (− 67, 9389) |

| Month | 49.88 (− 61, 158) | |

| Readmissions | 9098.24† (7142, 11,812) | |

| Index DRG | ||

| 190 (with MCC) | 861.47 (− 2587, 4539) | |

| 191 (with CC) | 104.76 (− 2910, 3235) | |

| Interactions | ||

| Intervention x DRG 190 | − 5936.64* (− 12,185, − 261) | |

| Intervention x DRG 191 | − 6080.75* (− 12,227, − 415) | |

| Intervention x Readmissions | 1069.18 (− 2335, 4215) | |

| Age at admit | − 66.52 (− 177, 43) | |

| Race | ||

| Other | − 1473.15 (− 7296, 5832) | |

| White | 2680.72 (− 838, 6437) | |

| Female | 505.16 (− 1808, 2957) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Not asked | − 4704.04 (− 12,009, 2674) | |

| Quit | − 1298.83 (− 5765, 2736) | |

| Yes (current) | − 2612.38 (− 7421, 1897) | |

| 1st post-discharge setting | ||

| HH | 2380.40* (112, 4670) | |

| Other | 2225.20 (− 3558, 9022) | |

| SNF | 17,094.88† (12,163, 22,192) | |

| Weekend stay | 4761.02 (− 1880, 12,284) | |

| N | 293 | 293 |

Regressions of various outcomes to adjust for potential confounders

*p < 0.05, †p < 0.01; 95% confidence intervals are in parentheses

90-day readmit count: a zero-inflated Poisson regression was used for the total number of readmissions each episode within a 90-day post-index-discharge period; the coefficient is an incidence rate ratio, i.e., a value of 1 implies no effect

Episode target delta: a linear regression was used to estimate those coefficients. A coefficient value of 0 implies no effect. Episode target delta is calculated in dollars as (net episode payment minus target amount) for each episode

95% confidence intervals for episode target delta were estimated using bootstrapping with 20,000 replications (bias corrected and accelerated method); confidence intervals for 90-day readmit count are robust to heteroskedasticity

The reference groups are control group, index DRG of 192, Black, male, never-smoker, and first post-discharge setting of self-care

Interaction terms (denoted by “x”) with intervention/control group were included for index DRG, and for number of Readmissions for the episode target delta regression, because the intervention could conceivably affect the outcomes in consideration differently depending on clinical severity (which DRG is a proxy for) and number of readmissions. Interactions were also analyzed for intervention/control group with first post-discharge setting and with smoking status but were non-significant and are not shown. A month term was included to look for time trends independent of the intervention. Readmissions is the total number of readmissions per episode

When comparing our historical control period to the intervention period, there was not a significant difference in episode costs relative to target costs (see Appendix C). Similar to the main analysis, readmissions and hospital discharges to SNFs were associated with higher episode costs. DRG was not an effect modifier of the intervention’s impact on episode cost in the secondary analysis.

Clinical Outcomes (Table 4)

Table 4.

Clinical Outcomes

| Control | Intervention | 95% CI of IRR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 161 | n = 132 | |||

| LOS (days) | 0.92, 1.23a | |||

| Min | 0 | 0 | ||

| Median | 3 | 3 | ||

| Max | 15 | 17 | ||

| First post-discharge setting, n (%) | 0.1b | |||

| HH | 38 (23.6) | 47 (35.61) | ||

| Other | 3 (1.86) | 3 (2.27) | ||

| SNF | 19 (11.8) | 18 (13.64) | ||

| Self-care | 101 (62.73) | 64 (48.48) | ||

| # Readmissions, n events (mean # per episode) | ||||

| 0–90 days | 122 (0.76) | 68 (0.52) | 0.46, 0.99a | |

| 0–30 days | 43 (0.27) | 25 (0.19) | 0.41, 1.21a | |

| 31–60 days | 42 (0.26) | 24 (0.18) | 0.41, 1.19a | |

| 61–90 days | 37 (0.24) | 19 (0.14) | 0.33, 1.18a | |

IRR, incidence rate ratio

Clinical outcomes of the control and intervention groups. n’s are on the episode level. HH is home health, SNF is skilled nursing facility, and other includes hospice, inpatient psychiatry, and long-term care. Number of readmissions is the total number of all-cause readmissions within each time period (inclusive), where days is the number of days from the index discharge date. 95% confidence interval of IRRs (intervention compared to control) and p-value calculations were performed using (a) univariate negative binomial regressions and (b) Fisher’s exact test

The median length of index hospital stay for both the intervention and control groups was 3 days. Overall, there was not a difference in post-discharge setting. However, there was a 51% higher rate of discharge to home with HH services for the intervention versus control group. The mean number of all-cause readmissions per episode (hereafter, “readmission rate”) within 90 days of index discharge was 0.52 versus 0.76 for the intervention versus control group, respectively (95% CI of incidence rate ratio (IRR): 0.46, 0.99). The intervention group demonstrated a significant decrease of 0.24 readmissions per episode. The 0–30-, 31–60-, and 61–90-day readmission rates were 0.08, 0.08, and 0.09 lower, respectively, for the intervention versus control group (95% CI of IRR: 0.41–1.21, 0.41–1.19, 0.33–1.18, respectively). When comparing the intervention period to the historical control period, 90-day readmission rates were non-significantly lower by 0.12; 0–30-day readmission rates were 0.09 lower in the intervention period, while 31–60- and 61–90-day readmission rates were similar across periods (95% CI of IRR: 0.43–1.17, 0.57–1.79, 0.46–1.65, respectively).

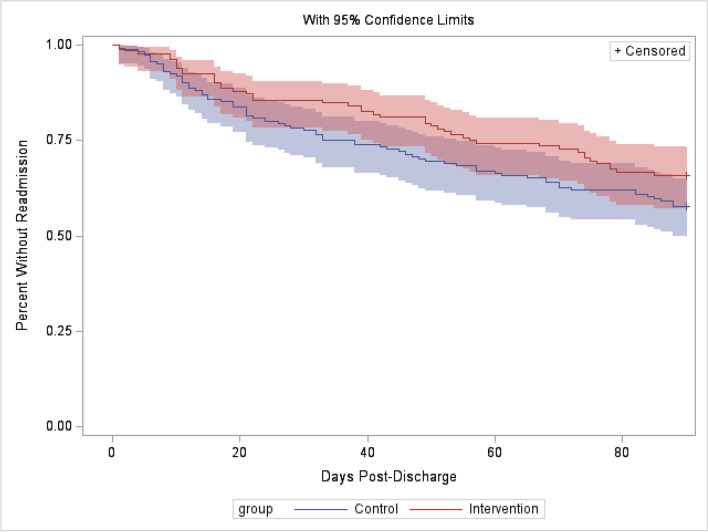

We also performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to first readmission for the control and intervention groups, in which the first readmission within an episode was considered a failure event (Fig. 2). While a log-rank test showed no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.1), the intervention group curve is persistently above the control group curve, although 95% CIs are overlapping.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of time to first readmission. Legend: a Kaplan–Meier analysis of readmissions within the control and intervention group episodes, where the first readmission after index discharge constituted a failure event.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first multi-year study of an entire COPD BPCI program. With respect to cost outcomes, overall, we did not find a statistically significant change in episode cost relative to target cost with the implementation of the UCM COPD program. The mean savings among intervention group episodes during the study period do represent absolute net savings to our hospital system. Episode costs were maintained below target significantly more often for the intervention group than for the control group. In addition, we found that index DRG was an effect modifier for the cost impact of the intervention: while the intervention increased episode costs for index admissions with the reference DRG of 192, it saved approximately $2000 per episode relative to control episodes for index admissions with DRGs of 190 and 191. Although these differences were not statistically significant within our small sample, the effect sizes are promising. These findings suggest that by targeting the intervention to more complex episodes, the impact of the program could be increased. Ongoing efforts exist to develop effective predictive models for identifying high-risk patients with the most potential to benefit from readmission reduction interventions.22 In our additional analysis comparing the intervention period to the historical control period, we found similar cost results and qualitatively similar 90-day readmission results, although the decrease in readmissions was non-significant.

The most significant cost drivers were being discharged to SNFs and number of readmissions within episodes. In terms of readmissions, the intervention group demonstrated a significant decrease of about a quarter of a readmission per episode. This reduction was sustained across the 0–30-, 31–60-, and 61–90-day periods, suggesting a long-lasting treatment effect rather than simply a delay of readmission. We also observed an increased number of episodes discharged to HH among the intervention group.

Our finding that readmissions are a significant driver of overall episode cost raises the question of what proportion of COPD readmissions are actually preventable, and whether hospitals participating in BPCI can be held responsible for that prevention.23–25 One review that quantified what percent of readmissions were deemed avoidable found a median of 27%.26 Multiple studies have found that readmission rates are more closely correlated with case mix and the socioeconomic mix of a hospital’s patient population than with hospital quality, and that teaching and safety-net hospitals are therefore more likely to have higher baseline readmission rates, as well as to face disproportionate penalties.27–30 In fact, in 2019, the HRRP began to adjust penalties for safety net hospitals by benchmarking performance against hospitals with similar proportions of patients dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid;5 perhaps a similar approach is needed for BPCI. The goal of bundled care payment structures is to create more integration across post-acute care processes overall, but if unpreventable readmissions are preventing BPCI participants from realizing savings, they may disincentivize participants from investing at all in improving the value or coordination of post-acute care.

Our results are similar to those described in an analysis of a COPD BPCI intervention at the University of Alabama Birmingham hospital.4 That study did not have a sufficiently large sample size to detect a clinically significant decrease in readmission rates; the authors note that with the numbers of patients admitted to most tertiary care centers for AECOPD, it would be difficult for any single center to demonstrate a significant improvement in either readmission rates or costs.31 At a national level, it is not clear whether BPCI can be unequivocally successful for chronic diseases such as COPD. Although BPCI has been shown to reduce Medicare payments for total joint replacements, a study of BPCI participant vs. matched control hospitals for the five most common medical BPCI conditions (COPD, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, sepsis, and acute myocardial infarction) found no significant change in Medicare payments.32 It is possible that for medical rather than surgical episodes, controlling costs above the median-priced episode is much more difficult due to the unpredictability and clinical complexity of the conditions. Furthermore, in a study of AECOPD care quality across US hospitals, changes in care quality were not associated with implementation of CMS’ HRRP penalty.33

Limitations of our study include lack of randomization. The lack of randomization was due to a system-level effort to provide evidence-based transition of care interventions to all patients identified as being hospitalized for AECOPD with the aim of reducing recurrent acute care utilization for the entire population. Randomization was not a logistically feasible option in this regard. Another theoretical concern of randomizing patients is an ethical concern related to intentionally providing some patients with evidence-based interventions and not others. However, it is important to note that a study using randomization to test transition of care interventions for patients with COPD published after our BPCI program found higher 6-month revisit rates for the intervention, indicating that equipoise can exist in these situations.34 An additional limitation is in regard to inconsistent staffing of the program by the APN, as is common in real-world clinical interventions. For instance, in 2016Q2, there was only inpatient coverage (inpatient consults) and no ambulatory visits due to temporary staffing changes, and in 2017Q1 there was no APN available due to another temporary staffing change. A historical control period analysis done to address these concerns did not alter the directionality of our main findings. While reassuring that this secondary analysis did not alter the findings, it is important to note an additional limitation related to this approach, namely that validity of these findings could be affected by ecologic effects from implementation of CMS’ HRRP beyond the BPCI intervention. One potential systemic bias is that higher health care (especially inpatient) utilization may have made enrollment into the UCM COPD program more likely, due to problem lists clearly identifying COPD as a prior diagnosis. COPD lacks a pathognomonic identifier such as an abnormal laboratory value or vital sign and is therefore, known to be under- and over-diagnosed, often without guideline-recommended spirometry. This could have led to a higher proportion of patients with greater acuity or fewer resources in the intervention group. However, we found no significant difference in DRG breakdown between the intervention and control groups; furthermore, we mitigated this limitation by controlling for selected confounders using regressions. We note that this selection bias would attenuate rather than contribute to our finding that the intervention group had lower costs on average than the control group. Second, due to limited patient-level clinical data beyond demographics within our available datasets, we did not include a measure of comorbidity burden, nor of clinical history such as past COPD exacerbations. This limitation is lessened by the fact that we compared costs on an episode-level to a target price that is DRG-specific; DRGs are stratified by clinical severity, and the target prices therefore already adjust somewhat for clinical complexity. Third, while we have total inpatient and outpatient costs for each episode, our data sources did not include costs of running the intervention itself; therefore, we could not perform a return on investment analysis of the intervention. With the exception of a dedicated APN team member (who could bill for care and partially recover salary costs), most of the intervention components utilized existing hospital resources and were considered part of usual care. Another important limitation is that this study focused on the CMS BPCI program related to patient episode costs and whether the program was below or above target. Program-related costs were not included in the analysis. It is important to note that in providing the clinical care through the program additional costs were incurred by the health system. Future work should include a full cost-effectiveness analysis and a chart review to capture more patient-level clinical descriptors. Finally, given the COVID-19 pandemic occurred after the study period, it will be critical for future research to evaluate the effect the pandemic had on existing COPD transition of care programs.

Overall, for participants of the UCM COPD program, median episode costs remained below the CMS target price, and mean episode cost differences were $2551 lower for the intervention versus control group, although non-significantly. The cost impact of the intervention was stratified by DRG, suggesting a way to target the intervention in the future to maximize its impact. We found that 90-day readmissions, a primary driver of costs, decreased significantly by 0.24 readmissions per episode. Future work includes conducting full cost-effectiveness analyses, and incorporating more clinical data obtained through chart review.

Conflict of Interest

This research was supported in part by the NIH NIA grant #5T35AG029795-12. The authors of this document assume responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of information and the statements in the document are solely those of the authors. VG Press has research support from National Heart Lung and Blood Association (R01HL146644), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS027804), and the American Lung Association. VG Press also discloses consultant fees from Vizient Inc. and Humana. None of the other authors have any disclosures.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the COPD Program advanced practice nurses. We also thank the Center for Transformative Care for their support of our BPCI program and for data assistance. Finally, we thank Mary Akel for her administrative assistance.

Author Contribution

AW and VGP conceptualized this study, assisted with data collection and analyses, and interpreted the data, as well as drafted and revised the manuscript. TK, SC, RK, and SRW helped design of the study, interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript. WW assisted in data cleaning and data analyses, assisted with data interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. AG contributed to data interpretation as well as critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. They agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

AW was supported in part by the NIH NIA grant #5T35AG029795-12. The funder played no role in the collection, design, or reporting of data for this work. These data were collected independently from any funding source.

Data Availability

Since the data used in this manuscript are highly granular and contains potentially sensitive patient information, public sharing of the data would breach the University of Chicago’s IRB protocol requirements. Interested researchers may contact Valerie Press via email at vpress@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu for data requests.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations.

We previously presented these findings at our institution, the University of Chicago, as a poster at the 2019 Janet Rowley Department of Medicine Research Day, the Sixth Annual Research Symposium and Poster Session by the Center for Chronic Disease Research and Policy, and the 2018 UCM Quality Fair. We have also presented the work as a poster for the 2020 American Thoracic Society Annual Meeting and as an oral presentation at the 2020 Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Conference.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.CDC - COPD Home Page - Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Published January 29, 2019. Accessed July 9, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/copd/index.html

- 2.Lindenauer PK, Pekow P, Gao S, Crawford AS, Gutierrez B, Benjamin EM. Quality of care for patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):894–903. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah T, Press VG, Huisingh-Scheetz M, White SR. COPD Readmissions: Addressing COPD in the Era of Value-based Health Care. CHEST. 2016;150(4):916–926. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Iyer AS, et al. Results of a Medicare Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Readmissions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(5):643–648. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-775BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CMS. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed April 16, 2019 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html

- 6.CMS. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information | Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. Accessed April 15, 2019 https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/

- 7.Press VG, Au DH, Bourbeau J, et al. Reducing Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Hospital Readmissions. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:2161–170. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201811-755WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CMS. BPCI Model 2: Retrospective Acute & Post Acute Care Episode. CMS Innovation Center. Accessed October 27, 2020 https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bpci-model-2

- 9.P Lindenauer, Au D, Chang W, LaBrin J, Mularski R, Press V. COPD Implementation Guide. Accessed December 19, 2020 https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/globalassets/clinical-topics/clinical-pdf/shm_chronic_obstructive_pulmonary_disease_program_guide.pdf

- 10.2021 GOLD Reports. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. Accessed March 14, 2021 https://goldcopd.org/2021-gold-reports/

- 11.Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-Based Medication Reconciliation Practices: A Systematic Review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057–1069. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller SK, Kripalani S, Stein J, et al. A Toolkit to Disseminate Best Practices in Inpatient Medication Reconciliation: Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39 (8) AP1-AP3 10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39051-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored Education May Reduce Health Literacy Disparities in Asthma Self-Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(8):980–986. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1291OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Press VG, Arora VM, Shah LM, et al. Misuse of respiratory inhalers in hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):635–642. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1624-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Press VG, Arora VM, Trela KC, et al. Effectiveness of Interventions to Teach Metered-Dose and Diskus Inhaler Techniques A Randomized Trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):816–824. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-603OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lash DB, Mack A, Jolliff J, Plunkett J, Joson JL. Meds-to-Beds: The impact of a bedside medication delivery program on 30-day readmissions. JACCP J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019;2(6):674–680. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zillich AJ, Jaynes HA, Davis HB, et al. Evaluation of a “Meds-to-Beds” program on 30-day hospital readmissions. JACCP J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3(3):577–585. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feemster LC, Au DH. Penalizing hospitals for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(6):634–639. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1541PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diagnosis Related Group (DRG). Accessed August 16, 2019. https://hmsa.com/portal/provider/zav_pel.fh.DIA.650.htm

- 20.CMS. BPCI Advanced. CMS Innovation Center. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bpci-advanced

- 21.Desgagné A, Castilloux AM, Angers JF, Le Lorier J. The Use of the Bootstrap Statistical Method for the Pharmacoeconomic Cost Analysis of Skewed Data. PharmacoEconomics. 1998;13(5):487–497. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199813050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Press VG. Is It Time to Move on from Identifying Risk Factors for 30-Day Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Readmission? A Call for Risk Prediction Tools. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(7):801–803. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-246ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Press VG, Myers LC, Feemster LC. Preventing COPD Readmissions Under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program How Far Have We Come? Chest. 2021 Mar;159(3): 996–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Rinne ST, Press VG. Moving the Bar on Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Readmissions before and after the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program: Myth or Reality? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(4):423–425. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202001-010ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Press VG, Miller BJ. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and COPD: More Answers. More Questions. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):252–253. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2011;183(7):E391–402. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah T, Churpek MM, Coca Perraillon M, Konetzka RT. Understanding Why Patients With COPD Get Readmitted: A Large National Study to Delineate the Medicare Population for the Readmissions Penalty Expansion. Chest. 2015;147(5):1219–1226. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-Day Readmissions — Truth and Consequences. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1366–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of Hospitals Receiving Penalties Under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.94856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic status and readmissions: evidence from an urban teaching hospital. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(5):778–785. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Press VG, Konetzka RT, White SR. Insights about the economic impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions post implementation of the hospital readmission reduction program. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(2):138–146. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Evaluation of Medicare’s Bundled Payments Initiative for Medical Conditions. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1801569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rojas JC, Chokkara S, Zhu M, Lindenauer PK, Press VG. Care Quality for Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in the Readmission Penalty Era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(1):29–37. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202203-0496OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Chung S, et al. Effect of a Hospital-Initiated Program Combining Transitional Care and Long-term Self-management Support on Outcomes of Patients Hospitalized With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;322(14):1371–1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Since the data used in this manuscript are highly granular and contains potentially sensitive patient information, public sharing of the data would breach the University of Chicago’s IRB protocol requirements. Interested researchers may contact Valerie Press via email at vpress@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu for data requests.