ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The co-existence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and interstitial lung diseases (ILD) results in significant morbidity and mortality. So screening for OSA is important for its early diagnosis among ILD patients. The commonly used questionnaires for screening of OSA are Epworth sleep score (ESS) and STOP-BANG. However, the validity of these questionnaires among ILD patients is not well studied. The aim of this study was to assess the utility of these sleep questionnaires in detection of OSA among ILD patients.

Methods:

It was a prospective observational study of one year in a tertiary chest centre in India. We enrolled 41 stable cases of ILD who were subjected to self-reported questionnaires (ESS, STOP-BANG, and Berlin questionnaire). The diagnosis of OSA was done by Level 1 polysomnography. The correlation analysis was done between the sleep questionnaires and AHI. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for all the questionnaires. The cutoff values of STOPBANG and ESS questionnaire were calculated from the ROC analyses. P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results:

OSA was diagnosed in 32 (78%) patients with mean AHI of 21.8 ± 17.6.The mean age was 54.8 ± 8.9 years with majority being female (78%) and mean body mass index (BMI) was 29.7 ± 6.4 kg/m2. The mean ESS and STOPBANG score were 9.2 ± 5.4 and 4.3 ± 1.8, respectively, and 41% patients showed high risk for OSA with Berlin questionnaire. The sensitivity for detection of OSA was highest (96.1%) with ESS and lowest with Berlin questionnaire (40.6%). The receiver operating characteristics (ROC) area under curve for ESS was 0.929 with optimum cutoff point of 4, sensitivity of 96.9%, and specificity of 55.6%, while ROC area under curve for STOPBANG was 0.918 with optimum cutoff point of 3, sensitivity of 81.2% and specificity of 88.9%.The combination of two questionnaires showed sensitivity of >90%. The sensitivity also increased with the increasing severity of OSA. AHI showed positive correlation with ESS (r = 0.618, P < 0.001) and STOPBANG (r = 0.770, P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

The ESS and STOPBANG showed high sensitivity with positive correlation for prediction of OSA in ILD patients. These questionnaires can be used to prioritize the patients for polysomnography (PSG) among ILD patients with suspicion of OSA.

KEY WORDS: ESS and STOPBANG, ILD, OSA, questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is defined as a breathing disorder characterized by recurrent collapse of the pharyngeal airway during sleep, resulting in substantially reduced (hypopnea) or complete cessation (apnea) of airflow despite ongoing breathing efforts.[1] The estimated overall prevalence of symptomatic OSA is between 3 and 8% in men and 1 and 5% in women.[2] Various studies in the last two decade from India reported that the prevalence of OSA was nearly 3–4%.[3,4] It was estimated that nearly 82% of men and 93% of women with moderate-to-severe sleep apnea remain undiagnosed.[5] Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a diversified group of chronic debilitating conditions that result in progressive scarring and fibrosis of lung parenchyma along with dyspnoea, progressive deterioration in exercise tolerance and reduced life expectancy.[6,7] The prevalence and incidence of ILDs are varying across the world according to the genetics, ethnicity, and geographical variation in study population.[8,9] Various studies from India have also shown that the prevalence of ILD is variable with different subtypes. The commonly seen ILDs in India are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), sarcoidosis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP).[10,11,12]

OSA and ILD are chronic breathing disorders and co-existence of both have significant morbidity, mortality, and treatment related complications.[13,14] The sleep-related breathing disorders are frequently seen in ILD patients, however, there is paucity of data from India.[13] Not only the literature on the prevalence of OSA in ILD is limited, there is also paucity of health care facilities due to lack of polysomnography equipment and technicians in India. It is technically not possible to evaluate all the suspected patients with sleep study in India presently.[15]

Therefore, a screening tool of utmost important to evaluate the patients with high or low risk of OSA especially among ILD patients as the co-existence of both diseases result in worse the outcomes. This will also help in identifying those in need of PSG to confirm the severity of OSA for further treatment. A number of screening questionnaires have been developed to aid the diagnosis of OSA. The commonly used are Epworth sleep score (ESS), STOP-BANG, and Berlin questionnaires, which can be easily administered in the outpatient settings. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests varies widely with different study population.[16,17,18,19,20,21] However, there is scarcity of studies on validity of sleep questionnaires among ILD patients. The aim of this study was to assess the utility of various sleep questionnaire in early detection of OSA among ILD patients.

METHOD

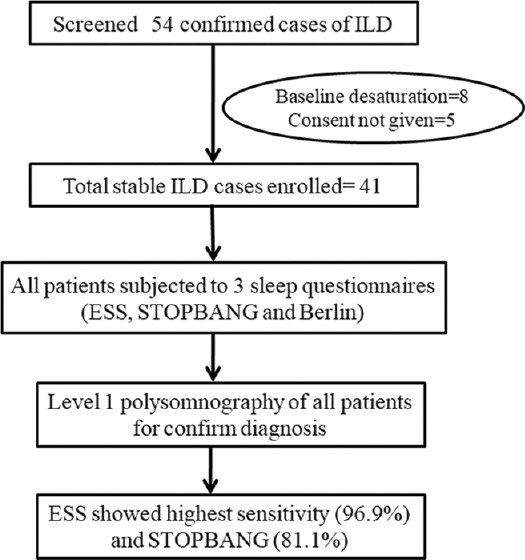

This study was a prospective observational study conducted at a tertiary chest centre of India from April 2018 to March 2019. The study was conducted after the approval of institutional ethics committee. We enrolled diagnosed, stable ILD patients, who maintained Spo2 >94% on room air at the time enrolment. Written consent was taken from all the patients. All enrolled patients were subjected to a self-reported questionnaire (ESS, STOP-BANG and Berlin questionnaires) to assess the sleepiness. The final diagnosis of OSA was done by Level 1 diagnostic polysomnography (PSG) according to American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guideline. After diagnosis of OSA, the severity was defined as per apnea hypopnea index (AHI).[22] The severity was graded as Mild OSA (AHI 5-15/hour), Moderate OSA (AHI 16-30/hour), and Severe OSA (AHI >30/hour). Patient with prior OSA, psychiatric disorder, age less than 18 and cognitive impairment were excluded from study. [Figure 1 shows details of patients screening, enrolment and OSA screening with diagnosis]. The primary aim and objective was to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of ESS, STOPBANG, and Berlin sleep questionnaires in predicting OSA among ILD patients. The secondary objective was to determine the correlation of above sleep questionnaires with AHI obtained by PSG.

Figure 1.

Details of patient screening, enrolment and OSA screening

Epworth sleep score

The ESS is widely used as a subjective measure of a patient’s sleepiness. The test is scored in a scale of 0 to 3 in eight situations, where a score of 0 denotes no chance of dozing while a score of 3 indicates high chance of dozing. The total score is 24. A score of ≥10 indicates high probability of OSA and needs further screening.[23]

STOP BANG questionnaire

It consists of 8 parameters including Snoring, tiredness, observed events, blood pressure, BMI >35 kg/m2, Age >50, neck size >17 inches (Males), >16 inches (Female), Male gender. Risk of OSA is low if 0-2 parameters are present, intermediate if 3-4 parameters are present and high risk if 5-8 parameters are present or 1-2 of 4 STOP questions are present along with male gender or BMI >35 kg/m2 or increased neck circumference.[24]

Berlin questionnaire

Berlin Questionnaire is a simple apnea screening questionnaire to assess the risk (low or high) of sleep disordered breathing. There are 3 scoring categories. Category 1 is positive with 2 or more positive response to questions 1–5. Category 2 is positive with 2 or more positive response to questions 6-9. Category 3 is positive with 1 positive response and/or BMI >30.[25]

Type I polysomnography

Polysomnography was done comprised of at least 7 channels namely Electroencephalogram (EEG), Electrooculography (EOG), Electromyography (EMG), nasal transducer, pulse oximeter, oronasalthermistor and chest, and abdominal effort leads. In PSG, an apnea is defined as the complete cessation of airflow for at least 10 seconds. Whereas hypopnea is defined as reduction in airflow (30%) followed by decrease in oxygen saturation by 4%. The AHI is calculated by dividing the number of apnea and hypopnea events by the number of hours of sleep. On basis of AHI, obstructive sleep apneahypopnea syndrome is defined as apnea hypopnoea index (AHI) >5 with excessive daytime sleepiness.[22]

Statistical analysis

The variables collected were entered in Microsoft Excel (Office 2007 or higher) and analyzed using SPSS (version 20). The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed variables and median (Q1, Q3) for skewed variables. A correlation analysis was done to find out the correlation between the questionnaires with AHI using Pearson’s correlation. The various predictive parameters, i.e., sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of all the questionnaire were calculated. The cut-off values of STOPBANG and ESS questionnaire were calculated from the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. The polysomnographic findings were taken as the gold standard for the diagnosis of OSAS. The P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 41 diagnosed cases of ILD were included in the study. The mean age of study population was 55.5 ± 10 years with majority of patients 30 (73%) being female. The mean BMI was 28.8 ± 6.5 kg/m2. The commonest type of ILD was hypersensitivity pneumonitis 19 (46.3%) followed by sarcoidosis 10 (24.4%). The common HRCT chest findings were ground glass opacities (83%), followed by fibrosis (66%) and traction bronchiectasis (46%). Pulmonary function test showed restrictive pattern along with decreased DLCO in all patients. Among the total cases 20% showed oxygen desaturation of >4% on 6 minute walk test.

On PSG, the OSA was diagnosed in 32 (78%) patients with mean AHI of 21.8 ± 17.6 events/hour. Most of the patients were female (78%). OSA was mild in 15 (46.9%), moderate in 7 (21.9%) and severe in 10 (31.3%) cases. The mean age of ILD with OSA patients was 54.8 ± 8.9 years with mean BMI of 29.7 ± 6.4 kg/m2. The most common type of ILD with OSA was hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The details of demographic and sleep-related parameters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and sleep-related parameters

| Parameters | n=32 |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 54.8±8.9 |

| Male: Female | 7:25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.7±6.4 |

| ATT history n (%) | 5 (16%) |

| Oral steroid treatment n (%) | 32 (94) |

| ESS (Mean) | 9.2±5.4 |

| STOPBANG (Mean) | 4.3±1.8 |

| Berlin (High risk n, %) | 13 (41%) |

| AHI (Mean) | 21.8±17.6 |

The mean score of ESS and STOPBANG were 9.2 ± 5.4 and 4.3 ± 1.8, respectively. High risk of OSA on Berlin questionnaire was seen in 13 (41%) cases. The sensitivity for detection of OSA was highest with ESS (96.9%) at a cut-off value of 4 followed by STOPBANG (81.2%) at a cut-off value of 3 and the least with Berlin questionnaire (40.6%). The specificity was highest for Berlin questionnaire (100%) and least for ESS (55.6%). All the three questionnaires had high positive predictive value with 88.6% to 100%. The negative predictive value was highest for ESS with 88.3% and lowest for Berlin questionnaire with 32.1%. The combination of two questionnaires (ESS and STOPBANG) had sensitivity of >90% for prediction of OSA and specificity of nearly 80%. The various predictive parameters of all three questionnaires in single and in combination are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Predictive parameters of ESS, STOPBANG, and Berlin questionnaires

| Questionnaire | Sensitivity % | Specificity % | PPV % | NPV % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To predict any OSA (AHI ≥5) | ||||

| ESS (cutoff=4) | 96.9 | 55.6 | 88.6 | 88.3 |

| STOPBANG (cutoff=3) | 81.2 | 88.9 | 96.3 | 57.1 |

| Berlin | 40.6 | 100 | 100 | 32.1 |

| ESS + STOPBANG (cutoff=8) | 90.6 | 77.8 | 93.5 | 70 |

The subgroup analysis of various predictive parameters for mild, moderate and severe OSA was done for each questionnaire. At same cut-off value, the sensitivity of ESS increased to 100% for moderate and severe OSA. Similarly, the sensitivity of STOPBANG also increased to 94.1% for moderate and 100% for severe OSA and sensitivity of Berlin questionnaire also increased to 58.8% for moderate and 90% for severe OSA. The increased sensitivity of all questionnaires was associated with decrease in specificity. The various predictive parameters of subgroups on the basis of severity of OSA are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Predictive parameters of questionnaires according to severity of OSA

| Questionnaire | Sensitivity % | Specificity % | PPV % | NPV % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To predict any OSA (AHI ≥5) | ||||

| ESS (cutoff=4) | 96.9 | 55.6 | 88.6 | 88.3 |

| STOPBANG (cutoff=3) | 81.2 | 88.9 | 96.3 | 57.1 |

| Berlin | 40.6 | 100 | 100 | 32.1 |

| To predict moderate OSA (AHI ≥15) | ||||

| ESS (cutoff=4) | 100 | 25 | 48.6 | 100 |

| STOPBANG (cutoff=3) | 94.1 | 33.3 | 61.5 | 83.3 |

| Berlin | 58.8 | 80 | 76.9 | 63.2 |

| To predict severe OSA (AHI ≥30) | ||||

| ESS (cutoff=4) | 100 | 19.4 | 28.6 | 100 |

| STOPBANG (cutoff=3) | 100 | 27.3 | 38.5 | 100 |

| Berlin | 90 | 81.8 | 69.2 | 94.7 |

We calculated the ROC for ESS and STOPBANG questionnaires and compared the two curves. The ROC area under curve was 0.929 for ESS questionnaire with an optimum cutoff point of 4, sensitivity of 96.9%, and specificity of 55.6% [Figure 2a]. The ROC area under curve was 0.918 for STOPBANG questionnaire with an optimum cutoff point of 3, sensitivity of 81.2%, and specificity of 88.9% [Figure 2b]. The comparison of the two ROC curves was not statistically significant, with P value of 0.346 [Figure 2c]. The ROC curve with comparison is shown in Figure 2. We also calculated the correlation of OSA with ESS and STOPBANG questionnaire by Pearson’s correlation. The AHI showed statistically significant positive correlation with ESS questionnaire with r = 0.618 and P < 0.001, and STOPBANG questionnaire with r = 0.770 and P < 0.001. The details of AHI correlation with both sleep questionnaires are in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

(a) ESS questionnaire ROC area under curve of 0.929 with a sensitivity of 96.9% and a specificity of 55.6% on cut-off of 4. (b) STOPBANG questionnaire ROC area under curve of 0.918 with a sensitivity of 81.2% and a specificity of 88.9% on cut-off of 3. (c) Comparison of two sleep questionnaire showing statistically not significant with P value 0.346 on ROC curve

Figure 3.

(a) Correlation of AHI with ESS sleep questionnaire showing positive correlation (r = 0.618, P < 0.001). (b) The correlation of AHI with STOPBANG sleep questionnaire showing positive correlation (r = 0.770, P < 0.001)

DISCUSSION

The present study found that the prevalence of OSA is common in ILD patients. The sleep questionnaires, including ESS, STOPBANG, and Berlin questionnaire, have good sensitivity to predict OSA in ILD patients and have shown positive correlation with AHI. So, these questionnaires are useful to screen OSA among ILD patients in resource limited settings for an early diagnosis. The diagnosis and management of sleep related breathing disorders in ILD patients may help in achieving better outcomes and improvement the quality of life. Different studies from various parts of the world found that OSA is frequently seen in ILD patients. A recent review showed that the overall sleep breathing disorder was seen in 44-72% of ILD patients.[13] Various other studies also found that the frequency of OSA ranges from 61-78% in ILD with most common ILD associated with OSA being IPF.[14,26,27] However, there is a lack of study on OSA amongst ILDs in India. Recently, a study from India showed high frequency of sleep disordered breathing among ILD patients (57%).[28] This study was done with an aim to find the role of various sleep questionnaires to predict OSA in ILD patients in India.

The sleep questionnaires have high predictive value for detecting the risk of OSA and are commonly used to screen for OSA in suspected patients. There are multiple questionnaires for screening of sleep disordered breathing. The commonly used sleep questionnaires are ESS, STOPBANG, and Berlin questionnaire. Various studies from Asia also showed different predictive value of OSA with these questionnaires when used alone or in combination.[16,17,18,19] Mahismita P et al. in a study of Indian population found that ESS had higher sensitivity than STOPBANG and perioperative sleep apnea prediction score (PSAP). They also found that the combination of 3 questionnaires improves the sensitivity of detection up to 95%.[16] Luo J et al.[17] in a Chinese population study found that the STOPPBANG questionnaire had excellent sensitivity in screening OSA with sensitivity of >90%. Similarly Ong TH et al.[18] in a study from Singapore also found that STOPBANG questionnaire had good sensitivity >85% for OSA prediction. While Kim B et al.[19] in a study of Korean patients found that STOPBANG questionnaire had higher sensitivity than Berlin questionnaire, Berlin questionnaire had better specificity than STOPBANG for prediction of OSA. The difference in the values of the risk of OSA may be due to difference in study population, questionnaire cutoff value, ethnicity, and risk of associated diseases. Most of the published studies of sleep questionnaires were done on suspected OSA patients with or without other risk factors. We found a sensitivity of 40-97% and specificity of 56-100% with three mentioned sleep questionnaires. These different predictive values of sleep questionnaires with higher sensitivity of ESS and STOPBANG in the present study may be due to the study population as all of our cases are diagnosed ILD patients.[16,17,18,19,20,21] To the best of our knowledge this is the first study from India in predicting OSA among ILD patients with the help of sleep questionnaire. There is a lack of such study among patients of chronic lung disease. Faria AC et al.[29] in a study used Berlin questionnaire and ESS to predict OSA among chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), and they found that both the questionnaires did not accurately predict OSA in COPD, with a ROC area under the curves of 0.54 and 0.69, respectively.[29]

The different studies used different cutoff values of STOPBANG for prediction of OSA risk. However, most of the studies considered score of ≥3 for high risk of OSA. Our study reported higher sensitivity (81.2%) and specificity (88.9%) of STOPBANG at cutoff value of 3 with ROC area under curve of 0.918 for predicting OSA in ILD patients. The published studies showed variable sensitivity of 65-97% and specificity of 18-65%.[16,17,18,19] The higher value of sensitivity and specificity in the present study may be explained by factors like patient characteristics as all of our patient were already diagnosed cases of ILD. The other factor may be higher BMI as some of studies also used lower BMI cutoff of >30 kg/m2 compared to standard of BMI of >35 kg/m2. There is a lack of health care facilities with polysomnography equipment and technician in our country as per the population size. STOPBANG questionnaire can be used to screen for OSA in ILD patients. The questionnaire will help to prioritize the patients for PSG and help in early diagnosis and treatment in a resource limited set up.

For ESS, we used the cutoff value of 4 for predicting the risk of OSA. We found a sensitivity of 96.9% and a specificity of 55.6% on this cut-off in ILD patients. Various published studies reported a sensitivity of 33-81% and a specificity of 44-75%.[16,20,21,30] The present study had higher sensitivity as compared to other published studies and a similar specificity. The higher sensitivity may be due to different cut-off value, patient profile, language barrier, geographic factors, and ethnicity of study population. We also found higher sensitivity and similar specificity of both ESS and STOPBANG questionnaire to predict OSA in ILD patients. We can apply these questionnaires to rule out the high risk of OSA in ILD patients, however, we need further study with larger population for confirmation of these findings.

Our study reported a sensitivity 40.6% and specificity 100% with Berlin questionnaire. Previous studies showed variable reports with a sensitivity of 71-95% and a specificity of 17-44%.[19,20,21,30] Our study reported higher specificity and lower sensitivity for detection of OSA in ILD patients. Out of three studied questionnaires, we found that ESS and STOPBANG have higher sensitivity with comparable specificity while sensitivity was lower for Berlin questionnaire as compared to the previous studies. This higher sensitivity might be due to different cut-off values and the study population. We chose lower cutoff value to avoid missing any case while screening the OSA among ILD. The combination of two questionnaires (ESS and STOPBANG) showed sensitivity of >90% with specificity of nearly 80%. The sensitivity of all the questionnaires also increased with severity of OSA with up-to 90-100% for severe OSA but the specificity decreased. However larger, multicentre study is required for further confirmation of these findings so that all the ILD patients should at least be screened for OSA with one of the sleep questionnaires.

Both the administered questionnaires showed significant positive correlation with AHI. Similar to our study Ulasli S S et al.[30] in a study found that the AHI showed positive correlation with ESS questionnaire (p < 0.0001, r = 0.173). Mahismita P et al.[16] in a study from India found significant positive correlation of ESS and STOPBANG with AHI (r = 0.39, P < 0.001 and r = 0.34, P = 0.004), respectively. Luo J et al.[17] also found significant correlation between STOPBANG and AHI (r = 0.519, P = 0.000 1). Overall, both the questionnaires have significant positive correlation with AHI and showed higher specificity and comparable sensitivity to predict the OSA in ILD patients.

There are a few limitations to this study. This was a single-centre, study of one year duration and the sample size was less with only 41 patients. So this may not be applicable upon every ILD patients. However, this was a pilot study for clinicians and researchers for further research and validation of sleep questionnaires in ILD patients suspected with OSA. The study included all types of ILDs with unequal distribution in both genders and a wide range of age group. As sleep disorders are not more common in female and affected by age and also the prevalence of OSA is different in various types of ILDs, we are unable to establish which questionnaire may be most effective in prediction of OSA in each subtype of ILDs.

CONCLUSION

OSA is common in ILD patients. The ESS and STOPBANG questionnaires showed high sensitivity and positive correlation with AHI for prediction of OSA in ILD patients. The combination of two questionnaires showed good sensitivity of >90% with specificity of nearly 80%. However, further larger study is needed for confirmation of our findings. We advise screening of all ILD patients with one or combination of questionnaires before PSG for early diagnosis of OSA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, Kuhlmann DC, Mehra R, Ramar K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea:An American academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:479–504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pien GW, Rosen IM, Fields BG. Sleep apnea syndromes:Central and obstructive. In: Grippi MA, editor. Fishman's Textbook of Pulmonary Disease and Disorders. New York: McGraw Hill Medicine; 2015. pp. 3042–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udwadia AF, Doshi AV, Lonkar SG, Singh CI. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep apnea in middle-aged urban Indian men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:168–73. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200302-265OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma SK, Ahluwalia G. Epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:171–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryu JH, Daniels CE, Hartman TE, Yi ES. Diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:976–86. doi: 10.4065/82.8.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collard HR, Pantilat SZ. Dyspnea in interstitial lung disease. Curropin Support Palliat Care. 2008;2:100–4. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282ff6336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duchemann B, Annesi-Maesano I, Jacobe de Naurois C, Sanyal S, Brillet PY, Brauner M, et al. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial lung diseases in a multi-ethnic county of Greater Paris. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1602419. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02419-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:967–72. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Collins BF, Sharma BB, Joshi JM, Talwar D, Katiyar S, et al. Interstitial lung disease in India. Results of a prospective registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:801–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1484OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhooria S, Agarwal R, Sehgal IS, Prasad KT, Garg M, Bal A, et al. Spectrum of interstitial lung diseases at a tertiary center in a developing country:A study of 803 subjects. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar R, Gupta N, Goel N. Spectrum of interstitial lung disease at a tertiary care centre in India. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:218–26. doi: 10.5603/PiAP.2014.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myall K, West A, Kent BD. Sleep and interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019;25:623–8. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pihtili A, Bingol Z, Kiyan E, Cuhadaroglu C, Issever H, Gulbaran Z. Obstructive sleep apnea is common in patients with interstitial lung disease. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:1281–8. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gothi D, Spalgais S. Manual versus automated sleep scoring for diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea. Indian J Sleep Med. 2016;11:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahismita P, Chandra OU, Dipti G, Jain A, Palai S, Sah RB, et al. Utility of combination of sleep questionnaires in predicting obstructive sleep apnea and its correlation with polysomnography. Indian J Sleep Med. 2019;14:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo J, Huang R, Zhong X, Xiao Y, Zhou J. Value of STOPBang questionnaire in screening patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome in sleep disordered breathing clinic. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:1843–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ong TH, Raudha S, Fook-Chong S, Lew N, Hsu AAL. Simplifying STOPBANG:Use of a simple questionnaire to screen for OSAS in an Asian population. Sleep Breath. 2010;14:371–6. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim B, Lee EM, Chung Y-S, Kim W-S, Lee S-A. The utility of three screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea in a sleep clinic setting. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56:684–90. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.3.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayed IHE. Comparison of four sleep questionnaires for screening obstructive sleep apnea. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2012;61:433–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pataka A, Daskalopoulou E, Kalamaras G, Passa KF, Argyropoulou P. Evaluation of five different questionnaires for assessing sleep apnea syndrome in a sleep clinic. Sleep Med. 2014;15:776–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults:recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness:The epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, Chung SA, Vairavanathan S, Islam S, et al. STOP questionnaire:A tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812–21. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mermigkis C, Chapman J, Golish J, Mermigkis D, Budur K, Kopanakis A, et al. Sleep-related breathing disorders in patients with ıdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung. 2007;185:173–8. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mavroudi M, Papakosta D, Kontakiotis T, Domvri K, Kalamaras G, Zarogoulidou V, et al. Sleep disorders and health-related quality of life in patients with interstitial lung disease. Sleep Breath. 2018;22:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utpat K, Gupta A, Desai U, Joshi JM, Bharmal RN. Prevalence and profile of sleep-disordered breathing and obstructive sleep apnea in patients with interstitial lung disease at the pulmonary medicine department of a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai. Lung India. 2020;37:415–20. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_6_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faria AC, da Costa CH, Rufino R. Sleep apnea clinical score, Berlin questionnaire, or Epworth sleepiness scale:Which is the best obstructive sleep apnea predictor in patients with COPD? Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:275–81. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S86479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulasli SS, Gunay E, Koyuncu T, Akar O, Halici B, Ulu S, et al. Predictive value of Berlin Questionnaire and Epworth sleepiness scale for obstructive sleep apnea in a sleep clinic population. Clin Respir J. 2014;8:292–6. doi: 10.1111/crj.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]