Abstract

Background

The frequent interactions of rodents with humans make them a common source of zoonotic infections. Brandt's vole is the dominant rodent species of the typical steppe in Inner Mongolia, and it is also an important pest in grassland.

Objectives:

To obtain an initial unbiased measure of the microbial diversity and abundance in the blood and intestinal tracts and to detect the pathogens carried by wild Brandt's voles in Hulun Buir, Inner Mongolia.

Methods

Twenty wild adult Brandt's voles were trapped using live cages, and 12 intestinal samples were collected for metagenomic analysis and 8 blood samples were collected for meta‐transcriptomic analysis. We compared the sequencing data with pathogenic microbiota databases to analyse the phylogenetic characteristics of zoonotic pathogens carried by wild voles.

Results

A total of 122 phyla, 79 classes, 168 orders, 382 families and 1693 genera of bacteria and a total of 32 families of DNA and RNA viruses in Brandt's voles were characterized. We found that each sample carried more than 10 pathogens, whereas some pathogens that were low in abundance were still at risk of transmission to humans.

Conclusion

This study improves our understanding of the viral and bacterial diversity in wild Brandt's voles and highlights the multiple viral and bacterial pathogens carried by this rodent. These findings may serve as a basis for developing strategies targeting rodent population control in Hulun Buir and provide a better approach to the surveillance of pathogenic microorganisms in wildlife.

Keywords: Brandt's voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii), bacterial pathogens, microbial diversity, viral pathogens, zoonotic diseases

Our research revealed the viral and bacterial diversity in wild Brandt's voles. The characterization and distinctive lineage of some rodent‐specific viruses (Cytomegalovirus, PestVs and Lentiviruses) and rodent‐borne bacteria (Leptospira interrogans and Vibrio cholerae) indicates that wild Brandt's voles may harbor a diversity of viruses and bacteria, some of which may have zoonotic potential. We must carry out surveillance and eradication in areas with high rodent density to prevent zoonotic pathogens spillover.

1. INTRODUCTION

Infectious diseases that originate in animals and infect humans account for the majority of recurrent and emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), which are widely considered to be one of the greatest challenges for public health (Han et al., 2015; He et al., 2022; Woolhouse & Gowtage‐Sequeria, 2005). Characterization of pathogen transmission events from wildlife to humans remains an important scientific challenge hampered by pathogen detection limitations in wild species (Johnson et al., 2020). Zoonotic disease spillover events are difficult to detect, especially if the disease spectrum includes mild or nonspecific symptoms or is limited by a lack of human‐to‐human transmission. To date, investigations of zoonotic disease outbreaks have mostly been passive, with surveillance efforts targeting specific host ranges and diseases (Woolhouse & Gowtage‐Sequeria, 2005).

The order Rodentia is the largest group of mammalian species, accounting for 43% of the global mammal biodiversity (Dorothée et al., 2002), with 2277 extant rodent species in 33 families (Meerburg et al., 2009). Due to their high diversity, worldwide distribution and most often close to human settlements, rodents are known to be reservoir hosts for 66 zoonoses and play major roles in pathogen transmission and spread through various ways (Han et al., 2015; Meerburg et al., 2009). In addition, rodents have close contact with arthropods (e.g. fleas, ticks and mites), wildlife and domestic animals and are a critical link in the transmission of various zoonotic pathogens between animals and humans (Cutler et al., 2010; ; He et al., 2022; Phan et al., 2011). Among the most important diseases in terms of public health, salmonellosis, plague, leptospirosis, bartonellosis, haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and tick‐borne relapsing fever are all caused by rodent‐borne pathogens (Bordes et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018; Li et al., 2016; Milholland et al., 2018; Shimi et al., 1979; Wu et al., 2018).

The intestinal microbiome is a multicomponent consortium of bacteria, archaea, fungi, protozoa and viruses that inhabit the intestines of all mammals (Carding et al., 2017), and a multitude of pathogens may be directly or indirectly transmitted to other animals or humans through vertical and faecal–oral routes. In recent years, interest in the gut microbiota has increased due to evidence of the influence of the gut microbiome on animal health and the development of various diseases and pathological conditions in animals and humans (Wang et al., 2019). Multiple infections by bacterial pathogens have been detected in tissue samples from rodents in Austria, such as Leptospira spp., Borrelia afzelii, Rickettsia spp. and different Bartonella species, which all have zoonotic potential (Schmidt et al., 2014). In addition, there is increasing evidence that many bacteria, including known pathogens, can survive in blood, and that bloodsucking arthropod vectors facilitated the transmission of these pathogens from one animal to another within specific reservoir communities and between different reservoirs (Nikkari et al., 2001; Potgieter et al., 2015; Ries et al., 1998). Therefore, the presence of intestinal and blood pathogens in wild animals may be associated with various infectious and noninfectious diseases, which have a high spillover risk from animals to humans once humans come into contact with diseased animals.

Brandt's vole (Lasiopodomys brandtii) is the dominant rodent species of the typical steppe in Inner Mongolia, and it is also an important pest in grassland (Zhang & He, 2013). Brandt's vole is a widespread species living in different habitats, allowing constant adaptation to environmental changes, contact with parasites and the transmission of rodent‐borne pathogens (Zhong et al., 1985). In particular, the high density of Brandt's voles near livestock and drinking water creates conditions for the transmission of parasites and pathogens between animals and humans (Zhong et al., 1985). Studies have shown that Brandt's vole is the main host of vole plague (Yersinia pestis), which has been periodically prevalent in Inner Mongolia (Li & Zhang, 1998). The most abundant bacterial phyla in the ceca of Brandt's voles are Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, accounting for approximately 91% of the bacterial population detected by 16S rRNA sequencing (Bo et al., 2019; Xu & Zhang, 2021), and rodent⁃borne Bartonella has also been isolated from tissues and blood (Ma et al., 2018). Accelerating environmental change and human activities leading to increased risks of EIDs suggests that joint efforts for surveillance, early detection, prevention and response to EIDs are needed.

In this study, we collected wild rodents in Inner Mongolia for metagenomic and meta‐transcriptomic analyses to reveal an overview of the bacterial and viral communities in intestinal and blood samples, then detected whether these wild rodents carried the pathogenic microbes that could causing the EIDs in humans. Moreover, we aimed to characterize the presence and phylogenetic position of potentially zoonotic pathogens and discuss the potential impact they may have in regard of public health issues.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study area and animal samples

The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is located in northern China (37°24′–53°23′N, 97°12′–126°04′E) with the predominant rodent species is Brandt's vole (Jiang et al., 2013). Animals were captured from the grassland of New Baerhu Left Banner, Hulun Buir region of Inner Mongolia (118°46′E, 48°43′N), China. Twenty wild adult Brandt's voles were trapped using live cages in the wet season between September and October 2021. Captured animals were humanely euthanized and blood and intestinal samples were collected in biosafety laboratory of Inner Mongolia Center for Disease Control and Research. Eight blood samples (more than 1.5 mL) were collected in 5 mL EDTAK2 blood‐collecting tube, and 12 intestinal content samples were collected in a cryogenic vial and temporarily stored in liquid nitrogen before being transported to the laboratory and stored at −80°C. All the procedures regarding this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Inner Mongolia Center for Disease Control and Research (Supporting Section).

2.2. Whole‐genome DNA and RNA extraction

Total DNA was extracted from ∼250 mg of intestinal samples using the QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Kit (Qiagen) (Bramble et al., 2021), and total RNA was extracted from blood serum using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) (Wu et al., 2021) following manufacturer's protocol and quantified by a NanoPhotometer NP80 (IMPLEN). DNA and RNA were stored at −20°C prior to sequencing and then submitted to the Novogene for metagenomic sequencing and meta‐transcriptomic sequencing.

2.3. Library construction

Ribosomal RNA was removed from total RNA to obtain mRNA, which was broken into 250–300 bp short fragments using divalent cations in NEB fragmentation buffer. The first‐strand cDNA was synthesized using the segmented RNA and oligonucleotide as primers. To convert first‐strand cDNA into dsDNA, the cDNA was incubated in the presence of Klenow fragment (NEB) (Wu et al., 2021).

A total amount of 1 μg DNA per sample was used as input material for the DNA sample preparations. Sequencing libraries were generated using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB) following the manufacturer's recommendations, and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. In brief, the DNA sample was fragmented by sonication to a size of 350 bp, and then DNA fragments were end‐polished, A‐tailed and ligated with the full‐length adaptor for Illumina sequencing with further PCR amplification. Finally, PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system), and libraries were analysed for size distribution by an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantified using real‐time PCR (Yin et al., 2022).

2.4. Sequencing, metagenomic analysis and meta‐transcriptomic analysis

Raw Data were obtained from the Illumina HiSeq PE150 metagenomic sequencing platform using Readfq (https://github.com/cjfields/readfq), and the reads of host origin were filtered using Bowtie 2.2.4 software (http://bowtiebio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml) (Karlsson et al., 2012, Yin et al., 2022). MEGAHIT software (v1.0.4‐beta) was used to assemble the Clean Data, then the assembled scaftigs were interrupted at the N connection, and the scaftigs without N were maintained (Feng et al., 2015). The scaftigs (>500 bp) assembled from both single were all predicted the open reading frame (ORF) by MetaGeneMark (V2.10, http://topaz.gatech.edu/GeneMark/) software, and those with lengths shorter than 100 nucleotide (nt) were filtered from the predicted result with default parameters (Karlsson et al., 2013). The Clean Data of each sample were mapped to the initial gene catalogue to obtain the number of contigs to which genes were mapped in each sample (Oh et al., 2014). DIAMOND software (V0.9.9, https://github.com/bbuchfink/diamond/) was used to align the contigs to the sequences of bacteria, fungi, archaea and viruses in BLAST, which were all extracted from the NR database (Version: 2021‐06‐01, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) of NCBI (Buchfink et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2018). The taxonomy of the aligned contigs with the best BLAST scores (BLASTp, E value ≤1e−5) from all lanes was parsed and exported with MEGAN 4 (Metagenome Analyzer) to ensure the species annotation information of sequences (Huson et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011).

Sequence reads from meta‐transcriptome were assembled using the software Trinity (v.2.4.0), and the resulting contigs were aligned to NCBI NR to identify any viral‐like sequences (Wu et al., 2021). The taxonomic identity is consistent with metagenome analysis described before. To estimate the abundance of the virus in each sample, contigs were assigned to each viral taxon at the level family and were normalized by the total number of sequencing contigs (Yang et al., 2011).

2.5. Pathogen detection and phylogenetic analysis

Pathogen detection was performed using next‐generation sequencing to compare the nt sequences in the samples with pathogenic microbiota databases created by Gene‐Plus Company, which include the NCBI RefSeq database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq), FDA‐ARGOS reference genome database (Sichtig et al., 2019), Reference Viral Databases (https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18776.2) (Bigot et al., 2020) and Eukaryotic Pathogen Database (Aurrecoechea et al., 2013), and all of these pathogen databases are used by hospitals to detect and identify pathogens that cause disease in humans. nt Sequences of genomes and amino acid sequences (aa) of ORFs were deduced by comparing sequences with this pathogenic microbiota databases. Therefore, pathogen detection identified viral and bacterial pathogens in our samples using the BLAST method (MEGA 6.0) was used to align the nt and the deduced aa sequences using the MUSCLE package and default parameters. The best substitution model was evaluated using the Model Selection package. We used neighbour‐joining to process the phylogenetic analyses with 1,000 bootstrap replicates (Tamura et al., 2013).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Metagenomic analysis of the intestinal microbiome

A total of 216 GB of nt data (85995.69 M Clean Data, with a mean effectiveness of 99.88%) was obtained. Reads were classified as bacteria, viruses, eukaryotes, prokaryotes and those with no significant similarity to any aa sequence in the MicroNR database, leading to 1561,345 reads were best matched with bacterial and viral protein sequences in the NR database (∼52.65% of the total gene number). All of reads were assembled to 1046,717 contigs and estimated the abundance of bacteria and virus (Table S1).

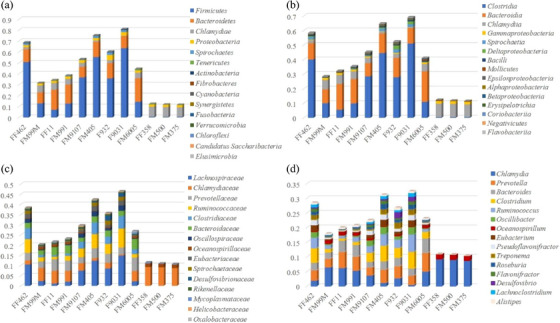

A wide range of bacterial groups were covered by these contigs (1045,801/1046,717 and 99.91%, Table S1). Bacteria‐associated reads were assigned to 122 phyla, 79 classes, 168 orders, 382 families and 1693 genera. While variables between individuals, the 15 most abundant bacterial phyla were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Chlamydiae, Proteobacteria, Spirochaetes, Tenericutes, Actinobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Cyanobacteria, Synergistetes, Fusobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Chloroflexi, Candidatus Saccharibacteria and Elusimicrobia in 9 samples (Figure 1). The other three samples showed low nt and aa sequence identity with known bacteria, and the top five abundant phyla were Chlamydiae, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Tenericutes and Actinobacteria. Additionally, Clostridia and Bacteroidia were the two most abundant classes in nine samples, whereas Chlamydia and Gammaproteobacteria were the two most abundant classes in the other three samples. However, when analysing bacteria at the family and genus taxonomic levels, we observed broader differences among study samples.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the diversity and abundance of the identified bacteria classified by phylum (A), class (B), family (C) and genus (D).

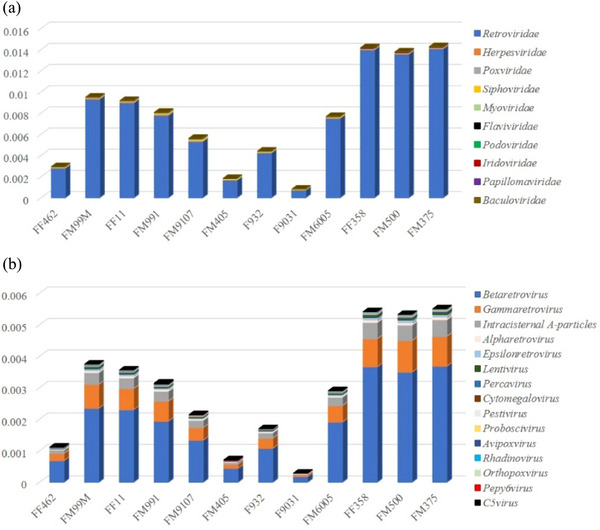

Virus‐associated contigs (916/1046,717 and 0.09%, Table S1) were assigned to 21 families of double‐stranded (ds) DNA viruses, retro‐transcribing viruses, single‐stranded (ss) DNA viruses and ssRNA viruses, which included 75 genera. Viral reads from the families Retroviridae, Herpesviridae, Poxviridae, Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, Flaviviridae, Podoviridae, Iridoviridae, Papillomaviridae, Baculoviridae, Mimiviridae, Ascoviridae, Microviridae, Reoviridae, Picornaviridae, Marseilleviridae, Alloherpesviridae, Polydnaviridae, Nudiviridae, Filoviridae and Phycodnaviridae were identified in this study. The relative abundances of the top 15 viral families and genera in the samples were calculated by relative sequence reads and are shown in Figure 2. There was no significant difference among samples when assessing viruses at the family and genus taxonomic levels.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of the diversity and abundance of the identified DNA viruses classified by viral family (A) and viral genus (B).

3.2. Meta‐transcriptomic analysis of the blood virome

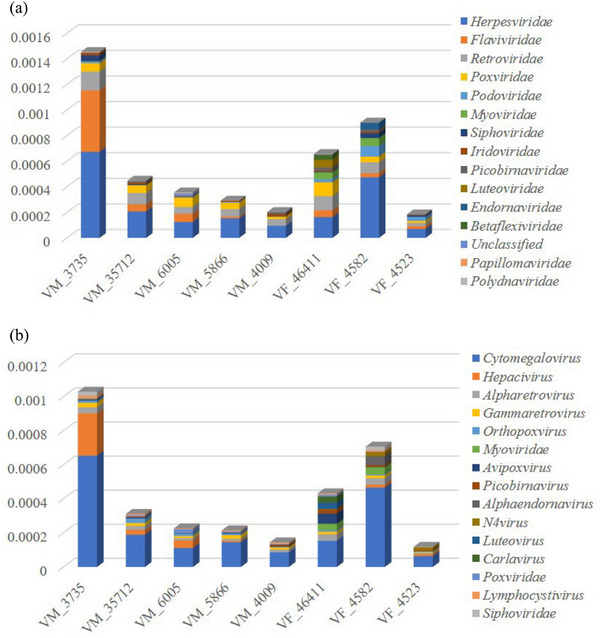

To determine whether viral RNA was present in each sample, an rRNA‐excluded RNA library was constructed and processed for NGS‐based meta‐transcriptomic analysis. A total of 57.23 GB of nt data was obtained. Reads that were classified as bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes and reads with no significant homology to any aa sequence in the NCBI NR database were removed. The remaining 35331 contigs (4.07% of total contigs) were used to identify best‐matched hits with viral proteins available in the NCBI NR database (Table S2). To analyse the composition of the virome in the blood, virus‐associated reads were classified into a group of unclassified RNA viruses and 25 known families of dsRNA viruses, reverse‐transcribing viruses, ssRNA viruses, dsDNA viruses and ssDNA viruses, which included 52 genera (Table S2). Viral contigs from the families Herpesviridae, Flaviviridae, Retroviridae, Poxviridae, Podoviridae, Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, Iridoviridae, Picobirnaviridae, Luteoviridae, Endornaviridae, Betaflexiviridae, Papillomaviridae, Polydnaviridae, Leviviridae, Filoviridae, Adenoviridae, Picornaviridae, Partitiviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Mimiviridae, Ascoviridae, Baculoviridae, Totiviridae and Alloherpesviridae were identified in this study. The contigs for each viral family in each sample were normalized by the viral genome size and the proportion of total viral contigs, and the relative abundances of the top 15 viral families and genera are shown in Figure 3. Based on the virome data provided by these meta‐transcriptomes, the prevalence and diversity of viruses in families including pathogens that are known to cause human and animal infection were then confirmed by phylogenetic analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Overview of the diversity and abundance of the virome classified by family (A) and genus (B) in each blood sample.

3.3. Phylogenetic characteristics of zoonotic pathogens

We used the BLAST method to compare the metagenomic sequencing data to pathogenic microbiota databases created by Gene‐Plus Company, and preliminarily identified pathogenic microbes from the intestinal and blood sample sequences (according to the confidence values). Phylogenetic analysis was performed to identify the genetic distance between pathogenic microorganisms and human pathogens. Our result uncovered those zoonotic pathogens existed widely in the intestinal tract rather than in the blood. The number of detected pathogens by Gene‐Plus Company is listed in Table 1, and pathogenic bacteria and viruses from the genera Vibrio (Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio harveyi), Yersinia (Yersinia enterocolitica, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia kristensenii), Rickettsia (Rickettsia felis and Rickettsia canadensis), Leptospira (Leptospira interrogans, Leptospira noguchii and Leptospira fainei), Bartonella (Bartonella grahamii, Bartonella rochalimae, Bartonella clarridgeiae and Bartonella tribocorum), Orientia (Orientia tsutsugamushi), Nocardia (Nocardia asteroids and Nocardia nova), Legionella (Legionella drancourtii), Gammaretrovirus, Pestivirus, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Lentivirus were detected in most of the samples. In addition, sequences of identified pathogens belonging to Vibrio, Leptospira, Pestivirus, CMV and Lentivirus, which are zoonotic pathogens that are known to cause human and animal infection, were selected to construct phylogenetic trees using the neighbour‐joining method to analyse the genetic distance between rodents and human pathogens.

TABLE 1.

Pathogens identified in intestinal and blood samples from Brandt's voles.

| Sample ID | No. detected microbiome | No. pathogens |

|---|---|---|

| FF11 | 2775 | 44 |

| FF358 | 108 | 12 |

| FF462 | 4700 | 61 |

| F932 | 4491 | 63 |

| F9031 | 4955 | 64 |

| FM375 | 248 | 32 |

| FM6005 | 3597 | 60 |

| FM991 | 3234 | 54 |

| FM9107 | 4437 | 58 |

| FM405 | 4944 | 74 |

| FF99M | 2786 | 51 |

| FM500 | 109 | 17 |

| VM_3735 | 206 | 5 |

| VM_35712 | 201 | 3 |

| VM_6005 | 184 | 5 |

| VM_5866 | 181 | 4 |

| VM_4009 | 182 | 5 |

| VM_46411 | 260 | 5 |

| VF_4582 | 229 | 5 |

| VF_4523 | 197 | 5 |

3.4. Herpesviridae, cytomegalovirus (CMV)

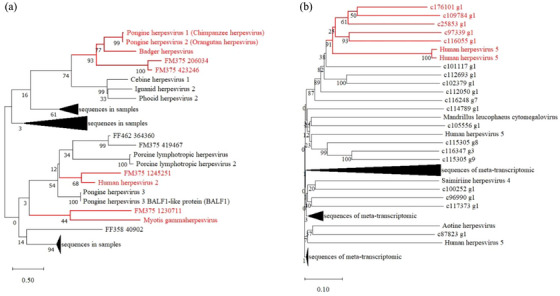

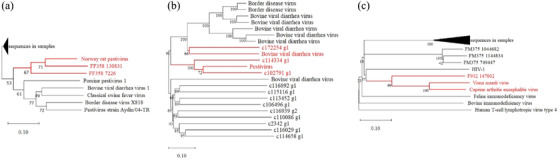

A total of 8 of 12 rodent intestinal samples (66.67%) and all of the blood samples (100%) were positive for cytomegalovirus (CMV) of the family Herpesviridae. Twenty‐eight assembled contigs in metagenomic sequencing were BLASTed to 11 herpesviruses, and the phylogenetic tree showed high sequence similarities (68%–93% aa identities) with chimpanzee herpesvirus, orangutan herpesvirus, badger herpesvirus and human herpesvirus but low similarity (only 44% aa identities) with myotis gammaherpesvirus (Figure 4A). Forty‐six assembled contigs in meta‐transcriptomic sequencing were BLASTed to seven herpesviruses, and the phylogenetic tree showed 91% aa identity to human herpesvirus 5 (Figure 4B, Table S2).

FIGURE 4.

Neighbour‐joining phylogenetic tree of Cytomegalovirus sequences identified in intestinal samples (A) and blood samples (B) of Brandt's voles.

3.5. Flaviviridae, pestiviruses (PestVs)

A total of 3 of 12 rodent intestinal samples (25%) and all of the blood samples (100%) were positive for pestiviruses (PestVs) of the family Flaviviridae. Seventeen assembled contigs in metagenomic sequencing were BLASTed to six PestV complete genome coding sequences (CDs), and the phylogenetic tree showed 71% aa identity to Norway rat pestivirus from artiodactylid hosts (Figure 5A). Twelve contigs in meta‐transcriptomic sequencing were BLASTed to nine PestV CDs, and the phylogenetic tree showed 66–72% aa identities with Bovine viral diarrhoea virus and Pestivirus (Figure 5B, Table S2).

FIGURE 5.

Neighbour‐joining phylogenetic tree of Pestiviruses (A and B) and Lentivirus virus (C) sequences identified in Brandt's voles.

3.6. Retroviridae, lentiviruses

A total of 4 of 12 rodent intestinal samples (33.33%) and none of the blood samples contained Lentiviruses of the family Retroviridae. Eight reads were BLASTed to five Lentivirus CDs, and the phylogenetic tree showed 99% aa identity with Visna maedi virus and Caprine arthritis encephalitis virus (Figure 5C).

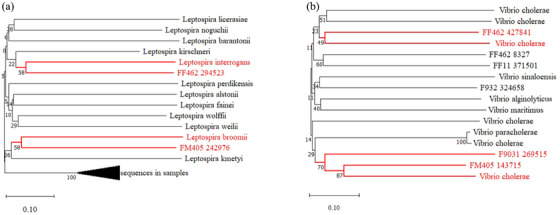

3.7. Leptospira, leptospira interrogans

Only intestinal samples tested positive for bacterial pathogens, and the Leptospira genus was detected in 7 of 12 intestinal samples (58.33%), of which only 4 individuals (33.33%) were positive for Leptospira interrogans. Twenty‐six contigs were compared to the Leptospira genus in the NR database, of which six were compared to L. interrogans, which causes the zoonotic disease known as Leptospirosis (Adler, 2015). We used these identified sequences of L. interrogans to construct the phylogenetic tree with other species of the Leptospira genus, and only some of these identified sequences showed 99% aa identity to L. interrogans (Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Neighbour‐joining phylogenetic tree of Leptospira interrogans (A) and Vibrio cholerae (B) sequences identified in Brandteq voles.

3.8. Vibrio, Vibrio cholerae

The Vibrio genus was detected in 9 of 12 (75%) intestinal samples, of which 5 individuals (41.67%) displayed the presence of Vibrio cholerae. A total of 1618 contigs were compared to the Vibrio genus in the NR database, of which 6 were compared to V. cholerae, which causes the disease known as cholera. Cholera is characterized by severe watery diarrhoea caused by toxigenic V. cholerae, which colonizes the small intestine and produces an enterotoxin, cholera toxin (Group, 1980). We used these identified sequences of V. cholerae to construct the phylogenetic tree with other species of Vibrio, and only some of these identified sequences showed high sequence similarities (49%–87% aa identities) with V. cholerae (Figure 6B).

4. DISCUSSION

Wild animals that are caught or bred are reservoirs of emerging pathogens and surveying the pathogen diversity in such potential reservoir species is a priority. In this study, we characterized bacteria and viruses in the intestinal and blood samples of Brandt's voles, identified zoonotic pathogens capable of causing disease in humans and explored the phylogenetic relationships of several viruses and bacteria of interest for human health.

The viral families we detected in Herpesviridae, Flaviviridae, Retroviridae, Poxviridae, Podoviridae, Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, Iridoviridae, Papillomaviridae, Baculoviridae, Mimiviridae and Ascoviridae were distributed in both intestinal and blood samples, which is partially different from other rodent metagenomics or virome studies. Phan et al. identified the mammalian virus families Circoviridae, Picobirnaviridae and Coronaviridae in faecal samples from wild mice and voles, which were not detected in our intestinal samples (Phan et al., 2011). In addition, Flaviviruses showed geographical preference and tended to be frequently detected in provinces in the north, west and middle of China (Wu et al., 2018), and our results also found Flaviviruses in wild voles in Inner Mongolia. The viral families targeted by the Global Virome Project include 16 families of RNA viruses known to infect humans, namely Arenaviridae, Astroviridae, Bunyaviridae, Caliciviridae, Coronaviridae, Filoviridae, Flaviviridae, Hepeviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Picobirnaviridae, Picornaviridae, Reoviridae, Retroviridae, Rhabdoviridae and Togaviridae, and an additional 8 families of DNA viruses that cause known zoonoses (Adenoviridae, Anelloviridae, Hepadnaviridae, Herpesviridae, Papillomaviridae, Parvoviridae, Polyomaviridae and Poxviridae), for a total to 24 viral families (Carroll et al., 2018). In this study, we detected 10 viral families that could infect humans or potentially cause disease in wild Brandt's voles, and some viral sequences had high similarity to known human viruses, which infect human and are transmitted by the faecal–oral or blood routes (Bergner et al., 2019). Therefore, the identification of diverse viruses and even pathogen‐related viruses in wild rodents indicates that the risk of EIDs originating from wildlife in different regions should not be underestimated. Furthermore, unclassified viruses were observed in each sample, and these sequences distantly related to known viral sequences were of unknown taxonomic origin, which suggests that rodent viruses need further study.

In addition to rodent‐specific viruses, rodent‐borne bacteria also cause a large number of zoonotic diseases (Choi et al., 2016). According to The List of Human Infections of Pathogenic Microorganisms issued by the Chinese Ministry of Health, there are more than 150 species of bacteria that can cause human infectious diseases, and rodents are often reservoirs of these bacterial pathogens. Furthermore, Brandt's voles can play key roles as major hosts in the transmission of Y. pestis (Fan et al., 2014). We identified 122 phyla of bacteria in the Brandt's vole and found a large number of pathogenic bacteria in intestinal samples, including Bartonella spp., Rickettsia spp., Yersinia spp., Orientia tsutsugamushi L. interrogans, Nocardia nova and V. cholerae. All surrounding environments can be contaminated by these pathogenic bacteria and animal pathogens can be transmitted by the respiratory or oral–faecal routes. Therefore, the close contact between humans and rodents seems to promote suitable conditions for the transmission of these pathogens. In China, Brandt's vole is the dominant native species in Hulun Buir, Inno Mongolia and is ecologically closely associated with humans and other animals This species is considered a pest, particularly during population outbreaks, which cause serious damage to pasture, and act as a reservoir and means of spread for Y. pestis (the causative agent of bubonic plague) (Zhang et al., 2003). As a result, it is necessary to monitor pathogenic microorganisms of wild rodents in Inner Mongolia for the prevention of zoonoses and the prevention and control of EIDs. In addition to identifying pathogens causing diseases that have already emerged, virome and zoonotic bacterial surveillance provide abundant data to help elucidate the distribution and richness of microorganisms carried by wildlife organisms (He et al., 2022).

In this study, we compared intestinal microbiota sequences with pathogenic microbiota databases and found that each sample contained more than 10 species of pathogens that could be potentially transmitted to humans. CMV is a common virus that infects people of all ages (Kenneson & Cannon, 2007), and the sequences detected in Brandt's voles showed high similarity to chimpanzee herpesvirus, orangutan herpesvirus, badger herpesvirus and human herpesvirus, with a high risk of transmission to humans and other mammals through contact with those pathogenic rodents. PestVs are a group of viruses of the genus Pestivirus of the family Flaviviridae that can infect a wide variety of artiodactylous hosts, and recent reports revealed that rodents could also act as natural hosts of PestVs (Wu et al., 2018). In this study, Norway rat pestivirus and bovine viral diarrhoea virus showed high similarity to our results, and the genotype of PestVs detected in this research needs to be further confirmed by RT‐PCR (reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction). Lentiviruses cause chronic diseases affecting the lungs, nervous, hematopoietic and immune systems of humans and animals (Haase, 1986). The prototypic lentiviruses are Visna maedi virus, with its Icelandic name derived from the prominent symptoms of the neurological and pulmonary diseases they cause in sheep (Preziuso et al., 2003), and Caprine arthritis encephalitis virus, which has been isolated from goat milk and is transmitted most efficiently to kids through both milk and colostrum (Liu et al., 2022). The natural grassland in Inner Mongolia is an important breeding ground for cattle and sheep, and Visna maedi virus and Caprine arthritis encephalitis virus have been detected in Brandt's vole, suggesting that there might be cross‐transmission of Lentiviruses and could be potentially transmitted to local livestock and residents. Regarding bacterial zoonoses, various bacterial pathogens in the gastrointestinal tracts of Brandt's voles were detected, including V. cholerae and L. interrogans. Cholera is a major health threat in nations with low socioeconomic status and is widely acknowledged as one of the most important water‐borne pathogens (Faruque et al., 1998), whereas leptospirosis is an emerging disease of global importance with variation in the severity of symptoms (Bharti et al., 2003). Outbreaks of these diseases are often associated with agricultural work or leisure activities involving exposure to contaminated surface water (Desai et al., 2009). Our results indicated that the Brandt's voles are the host of L. interrogans and V. cholerae. Therefore, V. cholerae and L. interrogans detected in Brandt's voles are most likely to be transmitted to livestock or humans through the environment or contaminated surface water. Although there is high similar of genome between the pathogens detected in wild voles and pathogens infected human, it is still difficult to accurately define the cross‐transmission between these pathogens. The bacteria and virome composition in animals are alike in both healthy and pathogenic (Du et al., 2016), because many viruses revealed by metagenomic and meta‐transcriptomic analyses in our study showed limited identity with known viruses. Therefore, continuous epidemiological surveillance and molecular studies are critical for an understanding of adverse effects as well as the control and prevention of the transfer of rodent pathogens to people and other animals.

In conclusion, this study provides an overview of the microbial community and diversity in Brandt's vole, and the presence of a large number of diverse RNA and DNA viruses with high prevalence and abundance highlights that rodents can tolerate multiple pathogenic viruses, as researches previously described in bats (Wu et al., 2012). Moreover, these findings greatly improve our knowledge of zoonotic pathogens in wildlife, and we must carry out surveillance and eradication in areas with high rodent density to prevent pathogens spillover. Predicting the risk of zoonotic pathogens jump from rodents into humans is tricky, as these spillovers take place in a complex ecological and human socio‐economic environment. Therefore, continued efforts in zoonotic pathogen surveillance among wildlife hosts will reveal greater diversity of viral and bacterial lineages and may enhance our ability to develop strategies to control zoonotic diseases.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; writing—original draft: Yongman Guo. Investigation: Zhengrun Li. Investigation: Shike Dong. Resources: Xiaoyan Si. Resources: Na Ta. Resources: Hanwei Liang. Project administration; writing—review and editing: Lei Xu.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Rodents were captured and treated in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Regulations for the Administration of Laboratory Animals (Decree No. 2 of the State Science and Technology Commission of the People's Republic of China, 1988), and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Inner Mongolia Center for Disease Control and Research.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

SuppTableS2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Novogenen for sequencing and providing specific experimental procedures of the library construction, and Springer Nature Author Services for professional language editing services.

Guo, Y. , Li, Z. , Dong, S. , Si, X. , Ta, N. , Liang, H. , & Xu, L. (2023). Multiple infections of zoonotic pathogens in wild Brandt's voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii). Veterinary Medicine and Science, 9, 2201–2211. 10.1002/vms3.1214

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Raw sequencing data were generated at Novogene. Derived data supporting the results of this study has been uploaded for review.

REFERENCES

- Adler, B. (2015). Leptospira and leptospirosis. Current topics in microbiology and immunology (Vol. 387, pp. 1–293). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-662-45059-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurrecoechea, C. , Barreto, A. , Brestelli, J. , Brunk, B. P. , Cade, S. , Doherty, R. , Fischer, S. , Gajria, B. , Gao, X. , Gingle, A. , Grant, G. , Harb, O. S. , Heiges, M. , Hu, S. , Iodice, J. , Kissinge, J. C. , Kraemer, E. T. , Li, W. , Pinney, D. F. , … Warrenfeltz, S. (2013). EuPathDB: A portal to eukaryotic pathogen databases. Nucleic Acids Research, 41, 685–691. 10.1093/nar/gks1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergner, L. M. , Orton, R. J. , Filipe, A. , Shaw, A. E. , Becker, D. J. , Tello, C. , Biek, R. , & Streicker, D. G. (2019). Using noninvasive metagenomics to characterize viral communities from wildlife. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(1), 128–143. 10.1111/1755-0998.12946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, A. R. , Nally, J. E. , Ricaldi, J. N. , Matthias, M. A. , Diaz, M. M. , Lovett, M. A. , Levett, P. N. , Gilman, R. H. , Willig, M. R. , Gotuzzo, E. , & Vinetz, J. M. (2003). Leptospirosis: A zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 3(12), 757–771. 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00830-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigot, T. , Temmam, S. , Pérot, P. , & Eloit, M. (2020). RVDB‐prot, a reference viral protein database and its HMM profiles. F1000Research, 8, 530–542. 10.12688/f1000research.18776.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo, T. B. , Zhang, X. Y. , Wen, J. , Deng, K. , & Wang, D. H. (2019). The microbiota‐gut‐brain interaction in regulating host metabolic adaptation to cold in male Brandt's voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii). The ISME Journal, 13(12), 3037–3053. 10.1038/s41396-019-0492-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordes, F. , Blasdell, K. , & Morand, S. (2015). Transmission ecology of rodent‐borne diseases: New frontiers. Integrative Zoology, 10(5), 424–435. 10.1111/1749-4877.12149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramble, M. S. , Vashist, N. , Ko, A. , Priya, S. , Musasa, C. , Mathieu, A. , Spencer, D. , Kasendue, M. L. , Dilufwasayo, P. M. , Karume, K. , Nsibu, J. , Manya, H. , Uy, M. N. A. , Colwell, B. , Boivin, M. , Mayambu, J. P. B. , Okitundu, D. , Droit, A. , Ngoyi, D. M. , … Vilain, E. (2021). The gut microbiome in konzo. Nature Communications, 12, 5371. 10.1038/s41467-021-25694-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink, B. , Xie, C. , Huson, D. H. , & Methods, N. (2015). Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nature Methods, 12, 59–60. 10.1038/nmeth.3176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carding, S. R. , Davis, N. , & Hoyles, L. (2017). Review article: The human intestinal virome in health and disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 46(9), 800–815. 10.1111/apt.14280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, D. , Daszak, P. , Wolfe, N. D. , Gao, G. F. , Morel, C. M. , Morzaria, S. , Pablos‐Mendez, A. , Tomori, O. , & Mazet, J. A. K. (2018). The global virome project. Science, 359(6378), 872–874. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29472471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E. , Pyzocha, N. J. , & Maurer, D. M. (2016). Tick‐borne illnesses. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 15(2), 98–104. 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, S. J. , Fooks, A. R. , & van der Poel, W. H. M. (2010). Public health threat of new, reemerging, and neglected zoonoses in the industrialized world. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 1–7. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/16/1/08‐1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S. , van Treeck, U. , Lierz, M. , Espelage, W. , Zota, L. , Sarbu, A. , Czerwinski, M. , Sadkowska‐Todys, M. , Avdicová, M. , Reetz, J. , Luge, E. , Guerra, B. , Nöckler, K. , & Jansen, A. (2009). Resurgence of field fever in a temperate country: An epidemic of Leptospirosis among seasonal strawberry harvesters in Germany in 2007. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 48(6), 691–697. 10.1086/597036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorothée, H. , Ole, M. , Sibbald, M. J. J. B. , Kai, A. , Stanhope, M. J. , François, C. , de Jong, W. W. , & Douzery, E. J. P. (2002). Rodent phylogeny and a timescale for the evolution of glires: Evidence from an extensive taxon sampling using three nuclear genes. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 19(7), 1053–1065. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, J. , Lu, L. , Liu, F. , Su, H. , Dong, J. , Sun, L. , Zhu, Y. , Ren, X. , Yang, F. , Guo, F. , Liu, Q. , Wu, Z. , & Jin, Q. (2016). Distribution and characteristics of rodent picornaviruses in China. Scientic Report, 6, 34381. 10.1038/srep34381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M. , Li, J. , Wei, R. , Mi, J. , Zhang, Z. , & Zhao, G. (2014). Epidemiological investigation of animal plague in Microtus brandti plague foci in China‐discovery of Mongolian gerbil plague. Chinese Journal of Endemiology, 33(5), 4. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4255.2014.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque, S. M. , Albert, M. J. , & Mekalanos, J. J. (1998). Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae . Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 62(4), 1301–1314. 10.1002/1092-2172/98/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q. , Liang, S. , Jia, H. , Stadlmayr, A. , Tang, L. , Lan, Z. , Zhang, D. , Xia, H. , Xu, X. , & Jie, Z. (2015). Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma‐carcinoma sequence. Nature Communications, 6, 53–41. 10.1055/s-0035-1551729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group, W. S. W. (1980). Cholera and other vibrio‐associated diarrhoeas. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 58(3), 353–374. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2395916/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase, A. T. (1986). Pathogenesis of lentivirus infections. Nature, 332(10), 130–136. 10.1038/322130a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. A. , Schmidt, J. P. , Bowden, S. E. , & Drake, J. M. (2015). Rodent reservoirs of future zoonotic diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(22), 7039–7044. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26038558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, W. T. , Hou, X. , Zhao, J. , Sun, J. , He, H. , Si, W. , Wang, J. , Jiang, Z. , Yan, Z. , Xing, G. , Lu, M. , Suchard, M. A. , Ji, X. , Gong, W. , He, B. , Li, J. , Lemey, P. , Guo, D. , Tu, C. , … Su, S. (2022). Virome characterization of game animals in China reveals a spectrum of emerging pathogens. Cell, 185(7), 1117–1129. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X. , Wang, X. , Fan, G. , Li, F. , Wu, W. , Wang, Z. , Fu, M. , Wei, X. , Ma, S. , & Ma, X. (2022). Metagenomic analysis of viromes in tissues of wild Qinghai vole from the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Scientific Reports, 12(17), 239–252. 10.1038/s41598-022-22134-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson, D. H. , Mitra, S. , Ruscheweyh, H. J. , Weber, N. , & Schuster, S. C. (2011). Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Research, 21(9), 1552–1560. http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.120618.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G. , Liu, J. , Xu, L. , Yu, G. , He, H. , & Zhang, Z. (2013). Climate warming increases biodiversity of small rodents by favoring rare or less abundant species in a grassland ecosystem. Integrative Zoology, 8(2), 162–174. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23731812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M. Z. , Hao, G. F. , Wang, J. , Juan, L. I. , Han, D. , Zhang, S. , & Tian, L. (2018). Investigation on natural infection of rodent‐borne pathogens in rodent populations in Urad port area, Inner Mongolia, China in 2015. Chinese Journal of Vector Biology and Control, 29(3), 296–297. http://epub.cnki.net/kns/oldnavi/n_CNKIPub.aspx?naviid=59&BaseID=ZMSK&NaviLink= [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. K. , Hitchens, P. L. , Pandit, P. S. , Rushmore, J. , Evans, T. S. , Young, C. C. W. , & Doyle, M. M. (2020). Global shifts in mammalian population trends reveal key predictors of virus spillover risk. Proceedings of the Royal Society. Biological sciences, 287(1924), 2736. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32259475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, F. H. , Fåk, F. , Nookaew, I. , Tremaroli, V. , Fagerberg, B. , Petranovic, D. , Backhed, F. , & Nielsen, J. (2012). Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nature Communications, 3(4), 1245–1352. 10.1038/ncomms2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, F. H. , Tremaroli, V. , Nookaew, I. , Bergstroem, G. , Behre, C. J. , Fagerberg, B. , Nielsen, J. , & Baeckhed, F. (2013). Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature, 498(7452), 99–103. 10.1038/nature12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneson, A. , & Cannon, M. J. (2007). Review and meta‐analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Reviews in Medical Virology, 17(4), 253–276. 10.1002/rmv.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, K. , Lin, X. , Huang, K. , Zhang, B. , Shi, M. , Guo, W. , Wang, M. , Wang, W. , Xing, J. , Li, M. , Hong, W. , Holmes, E. C. , & Zhang, Y. (2016). Identification of novel and diverse rotaviruses in rodents and insectivores, and evidence of cross‐species transmission into humans. Virology, 494, 168–177. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27115729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , & Zhang, Y. (1998). Epidemic periodicity and dynamic forecast of plague of Microtus brandti . Chinese Journal of Control of Endemic Diseases, 13(4), 193–194. 10.1002/CNKI:SUN. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. , Mulon, P. Y. , & Sula, M. J. M. (2022). Pathology in practice. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 260(4), 411–413. 10.2460/javma.20.12.0718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. , Li, D. , Chen, Z. , & Liu, Q. (2018). Epidemiological characteristics of rodent‐borne Bartonella. Disease surveilance, 33(1), 7–14. 10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2018.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meerburg, B. G. , Singleton, G. R. , & Kijlstra, A. (2009). Rodent‐borne diseases and their risks for public health. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 35(3), 221–270. 10.1080/10408410902989837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milholland, M. T. , Castro‐Arellano, I. , Suzán, G. , Garcia‐Peña, G. E. , Lee, T. E. Jr. , Rohde, R. E. , Aguirre, A. A. , & Mills, J. N. (2018). Global diversity and distribution of Hantaviruses and their hosts. EcoHealth, 15, 163–208. 10.1007/s10393-017-1305-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkari, S. , McLaughlin, I. J. , Bi, W. , Dodge, D. E. , & Relman, D. A. (2001). Does blood of healthy subjects contain bacterial ribosomal DNA? Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 39(5), 1956–1959. 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1956-1959.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J. , Byrd, A. L. , Deming, C. , Conlan, S. , Kong, H. H. , & Segre, J. A. (2014). Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature, 514, 59–64. 10.1038/nature13786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T. G. , Kapusinszky, B. , Wang, C. , Rose, R. K. , Lipton, H. L. , & Delwart, E. L. (2011). The fecal viral flora of wild rodents. PLoS Pathogens, 7(9), e1002218. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21909269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter, M. , Bester, J. , Kell, D. B. , Pretorius, E. , & Danchin, A. (2015). The dormant blood microbiome in chronic, inflammatory diseases. Fems Microbiology Reviews, 39(4), 567–591. 10.1093/femsre/fuv013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preziuso, S. , Sanna, E. , Sanna, M. P. , Loddo, C. , & Renzoni, G. (2003). Association of Maedi Visna virus with Brucella ovis infection in rams. European Journal of Histochemistry: EJH, 47(2), 151–158. 10.4081/821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries, M. , Deeg, K. H. , & Hümmer, H. (1998). Persistence of Yersinia antigens in peripheral blood cells from patients with Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 infection with or without reactive arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatology, 41(5), 855–862. 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<855::AID‐ART12>3.0.CO;2‐J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S. , Essbauer, S. S. , Mayer‐Scholl, A. , Poppert, S. , Schmidt‐Chanasit, J. , Klempa, B. , Henning, K. , Schares, G. , Groschup, M. H. , Spitzenberger, F. , Richter, D. , Heckel, G. , & Ulrich, R. G. (2014). Multiple infections of rodents with zoonotic pathogens in Austria. Vector‐Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 14(7), 467–475. 10.1089/vbz.2013.1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimi, A. , Keyhani, M. , & Hedayati, K. (1979). Studies on salmonellosis in the house mouse, Mus musculus . Lab Animal, 13(1), 33–34. 10.1258/002367779781071258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sichtig, H. , Minogue, T. , Yan, Y. , Stefan, C. , Hall, A. , Tallon, L. , Sadzewicz, L. , Nadendla, S. , Klimke, W. , Hatcher, E. , Shumway, M. , Aldea, D. L. , Allen, J. , Koehler, J. , Slezak, T. , Lovell, S. , Schoepp, R. , & Scherf, U. (2019). FDA‐ARGOS is a database with public quality‐controlled reference genomes for diagnostic use and regulatory science. Nature Communications, 10(1), 3313–3322. 10.1038/s41467-019-11306-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K. , Stecher, G. , Peterson, D. , Filipski, A. , & Kumar, S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30(12), 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Li, Q. , & Ren, J. (2019). Microbiota‐immune interaction in the pathogenesis of gut‐derived infection. Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 1873–1887. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31456801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse, M. E. J. , & Gowtage‐Sequeria, S. (2005). Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 11(12), 1842–1847. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/11/12/05‐0997_article [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z. , Han, Y. , Liu, B. , Li, H. , Zhu, G. , Latinne, A. , Dong, J. , Sun, L. , Su, H. , Liu, L. , Du, J. , Zhou, S. , Chen, M. , Kritiyakan, A. , Jittapalapong, S. , Chaisiri, K. , Buchy, P. , Duong, V. , Yang, J. , … Jin, Q. (2021). Decoding the RNA viromes in rodent lungs provides new insight into the origin and evolutionary patterns of rodent‐borne pathogens in Mainland Southeast Asia. Microbiome, 9(18), 1–19. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-17323/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z. , Liu, B. , Du, J. , Zhang, J. , Lu, L. , Zhu, G. , Han, Y. , Su, H. , Yang, L. , Zhang, S. , Liu, Q. , & Jin, Q. (2018). Discovery of diverse rodent and bat pestiviruses with distinct genomic and phylogenetic characteristics in several Chinese provinces. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 2562–2569. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z. , Lu, L. , Du, J. , Yang, L. , Ren, X. , Liu, B. , Jiang, J. , Yang, J. , Dong, J. , Sun, L. , Zhu, Y. , Li, Y. , Zheng, D. , Zhang, C. , Su, H. , Zheng, Y. , Zhou, H. , Zhu, G. , Li, H. , … Jin, Q. (2018). Comparative analysis of rodent and small mammal viromes to better understand the wildlife origin of emerging infectious diseases. Microbiome, 6(1), 178–189. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30285857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z. , Ren, X. , Yang, L. , Hu, Y. , Yang, J. , He, G. , Zhang, J. , Dong, J. , Sun, L. , Du, J. , Liu, L. , Xue, Y. , Wang, J. , Yang, F. , Zhang, S. , & Jin, Q. (2012). Virome analysis for identification of novel mammalian viruses in bat species from Chinese provinces. Journal of Virology, 86(20), 10999–11012. 10.1128/JVI.01394-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X. , & Zhang, Z. (2021). Sex‐ and age‐specific variation of gut microbiota in Brandt's voles. PeerJ, 9, e11434. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34164232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. , Yang, F. , Ren, L. , Xiong, Z. , Wu, Z. , Dong, J. , Sun, L. , Zhang, T. , Hu, Y. , & Du, J. (2011). Unbiased parallel detection of viral pathogens in clinical samples by use of a metagenomic approach. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 49(10), 3463–3469. 10.1128/JCM.00273-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H. , Wan, D. , & Chen, H. (2022). Metagenomic analysis of viral diversity and a novel astroviruse of forest rodent. Virology Journal, 19, 138–149. 10.1186/s12985-022-01847-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. , & He, H. (2013). Parasite‐mediated selection of major histocompatibility complex variability in wild Brandt's voles (Lasiopodomys brandtii) from Inner Mongolia, China. BMC Evolution Biology, 13, 149–162. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471‐2148/13/149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , Pech, R. , Davis, S. , Shi, D. , & Zhong, W. (2003). Extrinsic and intrinsic factors determine the eruptive dynamics of Brandt's voles Microtus brandti in Inner Mongolia, China. Oikos, 100(2), 299–310. 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.11810.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W. , Zhou, Q. , & Sun, C. (1985). The basic characteristics of the rodent pests on the pasture in Inner Mongolia and its ecological strategies of controlling. Acta Theriologica Sinica, 5(4), 241–249. 10.16829/j.slxb.1985.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

SuppTableS2

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequencing data were generated at Novogene. Derived data supporting the results of this study has been uploaded for review.