Key Teaching Points.

-

•

Phrenic nerve injury is a well-known and feared complication of catheter ablation, where the risk is dependent on the exact anatomical course of the nerve, its relationship to the endocardial border, and its distance to the site of ablation.

-

•

Ablation using pulsed field energy instead of conventional radiofrequency or cryothermal energy might overcome the risk of collateral damage to the phrenic nerve, owing to its nonthermal and relatively myocardium-selective properties. Clinical data from pulmonary vein isolation using pulsed field energy seem to confirm these preclinical findings.

-

•

The advantages of pulsed field energy in pulmonary vein isolation, where it enhances the safety of the procedure, can be extrapolated for the ablation of focal atrial tachycardias with a focus near the phrenic nerve. This overcomes the need for complex procedures where the phrenic nerve had to be protected by balloon inflation in the epicardial space or by creating an iatrogenic pneumothorax.

Introduction

Catheter ablation has become the standard of care in the treatment of recurrent focal atrial tachycardia (FAT), since these patients are poor responders to medical therapy, and since catheter ablation treatment yields high success rates.1 This procedure can routinely be performed with low complication rates. However, if the FAT originates close to the phrenic nerve, injury of this structure, with resultant impairment of diaphragmatic function, is a well-recognized and feared complication of catheter ablation.

Multiple approaches to prevent phrenic nerve injury during ablation of FAT have been described, but these approaches are generally more invasive and therefore more prone to complications, and are not easy to implement in routine daily practice.2, 3, 4, 5 The problem with conventional energy sources used for ablation of FAT, being radiofrequency or cryothermal energy, is that they are thermal and nonselective to cardiac tissue, with the risk of affecting neighboring structures. Pulsed field energy ablation (PFA) is a novel ablation modality that is currently used as an alternative energy source for pulmonary vein isolation in atrial fibrillation to overcome the potential risks and harm done by conventional thermal energy sources. Compared to radiofrequency energy preclinical data, PFA showed similar lesion depth but lower lesion width and a low vulnerability of the phrenic nerve to this type of energy.6,7 In the MANIFEST-PF trial, only transient phrenic nerve palsy was noted, which resolved within 1 day of the intervention.8

We present a patient in whom a FAT originating on the posterolateral wall of the right atrium could not be ablated safely with radiofrequency energy because of the proximity to the phrenic nerve. In a second procedure the patient’s FAT was successfully ablated using PFA. This is the first case report where pulsed field energy was used in this indication, with good clinical outcome.

Case report

A 33-year-old patient had been complaining of palpitations for years. Tachycardia was, however, never documented, and a previous electrophysiological study was negative. Recently, a symptomatic episode of atrial fibrillation was documented, and the patient was put on a treatment with bisoprolol and flecainide and scheduled for a pulmonary vein isolation. The electrophysiology study and electroanatomic mapping (CARTO 3 System version 7.2; Biosense Webster, Irvine, CA) were performed using a QDOT Biosense catheter delivering high-power short-duration radiofrequency energy according to the CLOSE protocol.9 The pulmonary veins were successfully isolated. During the procedure, frequent runs of atrial tachycardia were noted. Mapping of this tachycardia showed a FAT with earliest activation on the posterolateral wall of the right atrium. Ablation of this focus was attempted; however, only 2 cautious applications were delivered, since there was clear capture of the phrenic nerve during pace mapping of the phrenic nerve in the region of earliest activation (Figure 1). Antiarrhythmic drugs were continued.

Figure 1.

Local activation time (LAT) map of the right atrium in a right posterolateral view during tachycardia. The focus of the tachycardia is easily seen, with earliest activation in the area that is marked in red. Black dots mark places where capture of the phrenic nerve was obvious, which is in the same region as ablation should be attempted.

One month after the ablation procedure, the patient was seen for follow-up and appeared to be in atrial tachycardia at 123 beats per minute being highly symptomatic despite medical therapy. The p-wave morphology was suspect of an FAT originating in the lateral right atrium. A redo ablation of the FAT was discussed, but this time we decided to use pulsed field energy to overcome and minimize the risk of potential phrenic nerve injury.

The procedure was performed using the same mapping system. A Biosense SmartTouch catheter (Biosense Webster) was used, which was connected to a pulsed field energy generator (Galaxy Centauri; Galaxy Medical, San Carlos, CA), enabling a focal contact force–guided ablation using pulsed field energy. Isolation of the 4 pulmonary veins was first confirmed. Voltage mapping of the right and left atrium did not show any regions of low potentials. Burst pacing could easily induce an atrial tachycardia with a cycle length of 550 ms. Mapping of the tachycardia confirmed again an FAT in the right atrium with earliest activation in a region where local phrenic nerve capture was obvious. A relatively large region of early fragmented potentials was noted at the location of earliest activation. Ablation was performed with QRS-triggered pulses at an energy output of 25 amperes in a monopolar and biphasic mode. A setting of 25 amperes is the highest energy output setting available, which allows for safe and contiguous lesions.8 Contact force of at least 5 grams was deemed sufficient to allow for adequate electrode-tissue proximity, resulting in efficient energy delivery to the myocardial tissue with broad and contiguous lesions.10 The amount of irrigation was kept constant at 2 mL/min, since cooling of the catheter tip is not required when delivering nonthermal pulsed field energy.

During application of the lesions, the phrenic nerve was often stimulated by the pulse trains of ablation energy. There was frequent transient focal firing of the atrial tachycardia, necessitating a relatively broad region of ablation before the tachycardia eventually stopped firing. Some extra lesions were applied to consolidate the region of fragmented potentials. A total number of 14 applications were delivered (Figure 2).

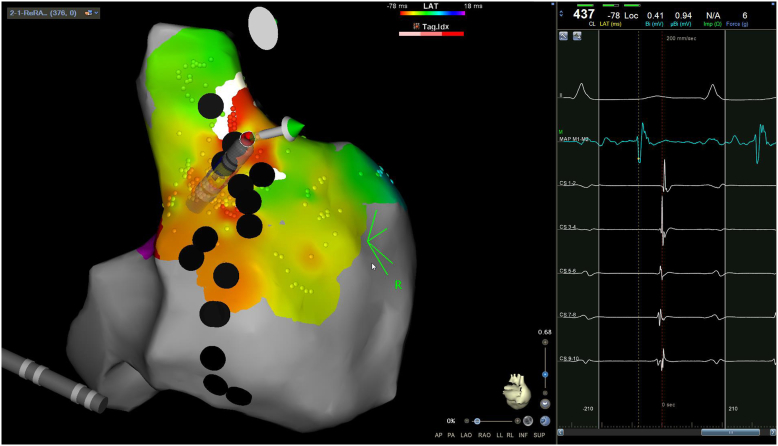

Figure 2.

Local activation time (LAT) map of the same tachycardia during the second procedure, showing the same focus of the atrial tachycardia. At the site of earliest activation a fragmented signal was noted preceding the surface p-wave with 35 ms. The green dots mark the 14 places where ablation with pulsed field energy was performed. Lesion tag size was set at 6 mm, corresponding with lesion diameters of 7.2 ± 1.6 mm seen on histologic examination with the same energy settings.8

At the end of the procedure, phrenic nerve capture was confirmed at the ablated area where the ablated atrial tissue was not entrainable. The tachycardia was noninducible despite aggressive burst pacing at a cycle length of 220 ms in baseline and during infusion of isoprenaline at 2 μg/min. The patient was discharged on the same day of the intervention. Antiarrhythmic drugs were discontinued. During 3 months of follow-up, she experienced no recurrence of palpitations and she remained in sinus rhythm confirmed on 24-hour Holter recording.

Discussion

Pulsed field energy has emerged as a novel energy form for the ablation of atrial fibrillation and will probably gain importance in the near future. Recent clinical data seem to confirm the preclinical data, where less collateral damage is done, especially with regard to nearby structures such as the esophagus or the phrenic nerves.8,11 The use of pulsed field energy for the treatment of FAT, however, is still new, with only 1 case report available describing ablation of a focus within the right atrial appendage.12

This is the first case report where the myocardial tissue–selective properties of pulsed field ablation were directly applicable in a case of FAT with a focus close to the right phrenic nerve. We were able to deliver pulsed field energy with the CE-labeled Galaxy system through a conventional focal contact force catheter.

Our approach seems to be an efficient and safe solution that overcomes the known difficulties of ablating foci within proximity of the phrenic nerve. Up until now, the only way to ablate safely in this region was by protecting the phrenic nerve during the ablation procedure, which has been done by balloon inflation in the epicardial space or by creating an iatrogenic pneumothorax.2, 3, 4, 5 We believe that these kinds of complex procedures will become obsolete once PFA with a focal catheter becomes more available.

Footnotes

Funding Sources: None. Disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.Brugada J., Katritsis D.G., Arbelo E., et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:655–720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah R.L., Perino A., Obafemi O., Lee A., Badhwar N. Intentional pneumothorax avoids collateral damage: dynamic phrenic nerve mobilization through intrathoracic insufflation of carbon dioxide. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2019;5:480–484. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee J.C., Steven D., Roberts-Thomson K.C., Raymond J.M., Stevenson W.G., Tedrow U.B. Atrial tachycardias adjacent to the phrenic nerve: recognition, potential problems, and solutions. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1186–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stark S., Roberts D.K., Tadros T., Longoria J., Krishnan S.C. Protecting the right phrenic nerve during catheter ablation: techniques and anatomical considerations. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2017;3:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K., Fuchigami T., Nabeshima T., Sashinami A., Nakayashiro M. Phrenic nerve protection via packing of gauze into the pericardial space during ablation of cristal atrial tachycardia in a child. Heart Vessels. 2016;31:438–439. doi: 10.1007/s00380-014-0603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Driel V.J.H.M., Neven K., van Wessel H., Vink A., Doevendans P.A.F.M., Wittkampf F.H.M. Low vulnerability of the right phrenic nerve to electroporation ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1838–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekanem E., Reddy V.Y., Schmidt B., et al. Multi-national survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety on the post-approval clinical use of pulsed field ablation (MANIFEST-PF) Europace. 2022;24:1256–1266. doi: 10.1093/europace/euac050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verma A., Neal R., Evans J., et al. Characteristics of pulsed electric field cardiac ablation porcine treatment zones with a focal catheter. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2023;34:99–107. doi: 10.1111/jce.15734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phlips T., Taghji P., el Haddad M., et al. Improving procedural and one-year outcome after contact force-guided pulmonary vein isolation: the role of interlesion distance, ablation index, and contact force variability in the ‘CLOSE’-protocol. Europace. 2018;20:f419–f427. doi: 10.1093/EUROPACE/EUX376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard B., Verma A., Tzou W.S., et al. Effects of electrode-tissue proximity on cardiac lesion formation using pulsed field ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.122.011110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yavin H., Brem E., Zilberman I., et al. Circular multielectrode pulsed field ablation catheter lasso pulsed field ablation: lesion characteristics, durability, and effect on neighboring structures. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2021;14:E009229. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.009229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbanek L., Chen S., Bordignon S., et al. First pulse field ablation of an incessant atrial tachycardia from the right atrial appendage. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2022;65:577–578. doi: 10.1007/s10840-022-01345-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]