Summary

Despite significant progress in unraveling the genetic causes of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), a substantial proportion of individuals with NDDs remain without a genetic diagnosis after microarray and/or exome sequencing. Here, we aimed to assess the power of short-read genome sequencing (GS), complemented with long-read GS, to identify causal variants in participants with NDD from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) BioResource project. Short-read GS was conducted on 692 individuals (489 affected and 203 unaffected relatives) from 465 families. Additionally, long-read GS was performed on five affected individuals who had structural variants (SVs) in technically challenging regions, had complex SVs, or required distal variant phasing. Causal variants were identified in 36% of affected individuals (177/489), and a further 23% (112/489) had a variant of uncertain significance after multiple rounds of re-analysis. Among all reported variants, 88% (333/380) were coding nuclear SNVs or insertions and deletions (indels), and the remainder were SVs, non-coding variants, and mitochondrial variants. Furthermore, long-read GS facilitated the resolution of challenging SVs and invalidated variants of difficult interpretation from short-read GS. This study demonstrates the value of short-read GS, complemented with long-read GS, in investigating the genetic causes of NDDs. GS provides a comprehensive and unbiased method of identifying all types of variants throughout the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes in individuals with NDD.

Keywords: neurodevelopmental disorders, whole-genome sequencing, long-read sequencing, structural variants

We performed short-read whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on 692 individuals from 465 families affected by neurodevelopment disorders and identified causal variants, including structural variants, non-coding variants, and mitochondrial variants, in 36% of affected participants. We also used long-read WGS to resolve intractable variants in five cases.

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) encompass a range of conditions that usually manifest in childhood, including intellectual disability, developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder, epilepsy, and movement disorders, among others. Although individually rare, collectively, NDDs affect millions of people worldwide and present huge challenges for families and healthcare systems.1

These disorders are phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous and are often caused by rare, highly penetrant variants. Over the last decade, exome sequencing (ES) and increasingly genome sequencing (GS) have been widely adopted for the identification of NDD-associated pathogenic (P) and likely pathogenic (LP) variants (collectively referred to as causal variants throughout this manuscript) in more than 900 NDD-associated genes identified to date.2,3 For families with affected children, receiving a genetic diagnosis has many benefits. It often marks the end of a long diagnostic odyssey, can affect clinical management, and allows parents to make more informed subsequent reproductive choices.1,3 The proportion of affected individuals in whom a causal variant is identified by genetic testing is known as the diagnostic yield, and it varies according to many factors. For example, in a recent meta-analysis, the range of diagnostic yield in studies using ES or GS in children with suspected genetic diseases was 24%–68%.4

Causal variants are most commonly coding nuclear single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels), and large copy-number variants (CNVs).5 Additional classes of genetic variation that can cause NDDs include small CNVs (below the resolution of chromosomal microarrays), inversions, translocations, complex structural variants (cxSVs), short tandem repeats (STRs), and variants in the mitochondrial (MT) genome.1 Detecting these classes of variation via short-read sequencing technologies is still challenging, causing an increasing appreciation for the potential role of long-read sequencing.6

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) BioResource conducted a flagship study whereby they performed short-read GS (srGS) on 13,037 individuals to study the genetic basis of rare disorders, including NDDs, in the UK national healthcare system.7 In the present study, we performed a detailed investigation of the 692 NDD-affected individuals from the NIHR BioResource cohort with the following three aims: (1) to use srGS to identify a comprehensive range of causal variants, including those that are often neglected by other methods; (2) to use supplementary long-read GS (lrGS) on a subset to help resolve and interpret variants that were unclear from srGS; and (3) to contribute to the identification of new associations between genes and NDDs. This study was notably successful at achieving all three of these aims. We have contributed to the identification or confirmation of four NDD-associated genes: KMT2B, CACNA1E, WASF1, and GABRA2, which have been published elsewhere.8,9,10,11 In this article, we focus on the first two aims and describe in detail the overall structure and results of the NIHR BioResource NDD study.

Materials and methods

Cohort description

The NDD sub-cohort of the NIHR BioResource project7 comprises 692 individuals, of whom 489 are affected by a NDD and 203 are unaffected relatives. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The study was approved by the East of England Cambridge South national institutional review board (13/EE/0325). The research conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent to participate was obtained so that clinical information could be published.

These individuals belong to 465 families. Our inclusion criteria required evaluation by a tertiary-level pediatric neurologist, who suspected a Mendelian disorder when the differential diagnosis included genes that had not been previously tested (see the supplemental material and methods for full details). 73% (357/489) of the participants have intellectual disability, developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder, a movement disorder or dystonia, and/or seizures (Figure S1). Recruitment of family members into this study varied depending on availability and the suspected mode of inheritance. We sequenced 335 singletons (affected proband only), 67 trios (affected proband and both parents), five quads (affected proband, both parents, and a sibling), and 58 families with another familial structural combination (Table 1). Most individuals had undergone routine genetic testing that had not identified a candidate variant prior to enrollment in this project, resulting in an enrichment for challenging cases.

Table 1.

Diagnostic yield by family structure

| Family structure | Affected individuals (families) |

Reportable variants: 289 individuals (59%) |

No causal variant identified: 200 individuals (41%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P or LP variants: 177 individuals (36%) |

VUSs: 112 individuals (23%) | |||||

| Full contribution: 168 individuals (34%) | Partial contribution: 9 individuals (2%) | |||||

| Total affected individuals: 489 (465 families) | singleton | 335 (335) | 111 (33%) | 8 (2%) | 78 (23%) | 138 (42%) |

| trio | 68 (67)a | 28 (41%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (18%) | 28 (41) | |

| two siblings | 28 (14) | 16 (57%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (14%) | 8 (29%) | |

| cousins | 2 (1) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| proband and parent | 39 (39) | 7 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (36%) | 18 (46%) | |

| proband and grandparent | 2 (1) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | |

| quad | 9 (5) | 4 (45%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (22%) | 2 (22%) | |

| proband, sibling, and parent | 6 (3) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33%) | 4 (67%) | |

GS identified causal variants in 36% of cases; 23% had a reported VUS, and 41% remained unresolved. Partial contribution refers to individuals with a causal variant that partially explains the phenotype. VUS, variant of uncertain significance; LP, likely pathogenic; P, pathogenic.

One trio includes an affected parent.

Short-read GS and identification of causal variants

DNA samples from whole blood underwent srGS. We performed alignment to the human genome of reference (GRCh37) and variant calling to identify multiple types of variants, including SNVs, indels, structural variants (SVs), and STRs (Figure S2), as described in the supplemental material and methods and a previous publication.7 Mobile element insertions (MEIs), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) status, and regions of homozygosity (ROHs) were also characterized.

Candidate rare variants were restricted to known NDD-associated genes (see next section) and discussed in multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs), which included research bioinformatics analysts, clinical scientists, and clinical geneticists. Additional information on the variant annotation and filtering strategies is provided in the supplemental material and methods. Pathogenicity was determined according to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines.12 Variants that were reported to the affected individual’s referring clinicians (also defined in this manuscript as reportable variants) comprised causal (P and LP) variants and variants of uncertain significance (VUSs) that could potentially explain the phenotype at the discretion of the MDT. Variants in genes of uncertain association with specific phenotypes were considered for research, further analysis, and sharing through GeneMatcher.13

Gene-list curation and variant re-analysis

We assembled a list of NDD-associated genes from various sources, including OMIM (https://omim.org), PanelApp14 (which also comprises DDG2P15), and PubMed searches, and then curated the list to ensure that the genes complied with previously described criteria.15 The gene list was updated six times throughout the timeline of the project, and the final version contained 1,545 genes (Table S1).

Initially, we investigated affected individuals by using the gene list available at the time of analysis. Then, we re-analyzed all individuals twice (July 2018 and July 2019) by using revised quality-control (QC) and filtering thresholds, as well as an updated version of the gene list at the time (v.20180117 and v.20180807, respectively). Re-analysis consisted of manual assessment of (1) rare variants in NDD-associated genes that had been added to the gene list since the first analysis, (2) variants reclassified as P or LP in the Human Gene Mutation Database16 or ClinVar17 since the first analysis, and (3) loss-of-function (LOF) SNVs or indels or variants predicted to be damaging (CADD Phred score > 20) in NDD-associated genes but with quality metrics below the strict filters employed for the initial analysis. Candidate variants identified by the last approach were manually inspected in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; v.2.5)18 and recommended for Sanger sequencing confirmation if they were suspected to be real.

Trio analysis

In families where both parents were available (67 trios and 5 quads), joint calling using Platypus variant caller19 was also run with default parameters. Then, we merged variants from both algorithms (Platypus and Isaac Variant Caller) and performed a gene-agnostic identification of candidate variants by mode of inheritance by using in-house filtering scripts described elsewhere.20 Variants were interpreted and reported in NDD-associated genes as described above.

Long-read GS

We performed lrGS with Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) by using the GridION platform for one individual (three runs) and the PromethION platform for four individuals (four runs). Samples were prepared and sequenced as previously described.21 Reads were aligned against the GRCh37 human reference genome, and sensitive detection of SVs was performed with an ensemble algorithm approach, as previously described.21 Additional information on the lrGS methods, algorithms, and versions can be found in the supplemental material and methods. Identification of candidate SVs was performed at the locus of interest, and manual inspection of the alignments was also performed with IGV.18

Results

Diagnostic yield in this NDD cohort achieves 36%

Affected individuals presented with a wide range of NDD phenotypes. The most frequent were intellectual disability (n = 199), seizures (n = 191), movement disorders (n = 78), dystonia (n = 68), and ataxia (n = 41), and many individuals had more than one phenotype (Figure S1). Reportable variants were identified in 59% (289/489) of affected individuals: 36% (177/489) had at least one P or LP variant, and a further 23% (112/489) had at least one VUS (Table 1).

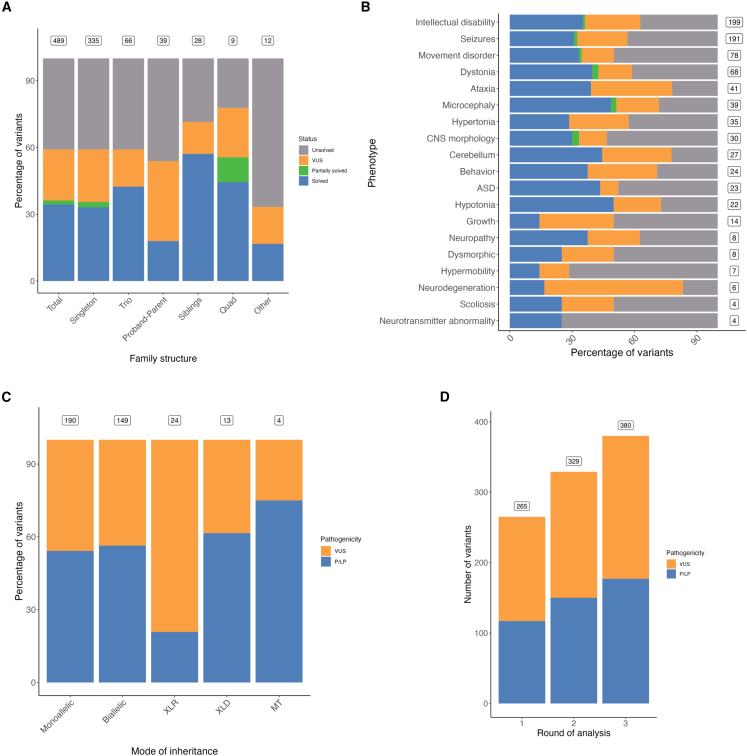

The detection rate of P and LP variants was affected by a series of factors. First, diagnostic yield was higher for trios (41% [28/67]) and pairs of siblings (57% [16/28]) than for probands only (35% [119/335]) (Figure 1A and Table 1). In four families, the reported variants were different among multiple affected individuals (Table S2), supporting previous observations that pathogenic shared variants within the same family should not be assumed.22

Figure 1.

Factors affecting variant discovery and diagnostic yield

(A) Diagnostic yield is affected by the sequenced family structure. Boxes show the number of affected individuals in each class of family structure. Singletons have no sequenced relatives, trios have both parents sequenced, proband parents have one parent sequenced, siblings have one sibling sequenced, and quads have both parents and one sibling sequenced. “Solved” refers to an affected individual with a P or LP variant. “Partially solved” refers to an affected individual with a P or LP variant that only partially explains the phenotype. “VUS” refers to an affected individual with a variant of uncertain significance. “Unsolved” refers to an affected individual with no identified P or LP variants or VUSs.

(B) Diagnostic yield is affected by phenotype. Boxes show the number of affected individuals with each phenotype. These numbers overlap because many individuals have more than one phenotype. ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CNS, central nervous system.

(C) The proportion of identified variants that are P or LP is affected by the mode of inheritance. Boxes show the number of identified variants in each class. XLR, X-linked recessive; XLD, X-linked dominant; MT, mitochondrial; VUS, variant of uncertain significance; P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic.

(D) The number of identified variants that are P or LP is affected by the round of analysis, where new variants were identified in each successive round, demonstrating the value of re-analysis. Boxes show the number of variants identified in each round (cumulative). Round 1 was March 2016 to January 2018, round 2 was July 2018, and round 3 was July 2019.

Additionally, the diagnostic rate varied depending on genetic ancestry (Table S3), phenotype (Figure 1B), and mode of inheritance (Figure 1C). Whereas 34% (111/325) of individuals of European ancestry had identified causal variants, only 3% (7/245) of the variants identified in that group were homozygous. The rate was higher in individuals of South Asian ancestry such that 40% (29/72) of variants were homozygous and 43% (35/82) of individuals had P or LP variants, consistent with previously reported results (Table S3).23

Furthermore, phenotypes with higher diagnostic rates included hypotonia (50% [11/22]; we note that our cohort was enriched for severe hypotonia), microcephaly (49% [19/39]), cerebellum abnormalities (44% [12/27]), and autism spectrum disorder (43% [10/23]), whereas abnormality of growth (14% [2/14]) and hypermobility (14% [1/7]) were lower (Figure 1B). 108 individuals with reportable variants had more than one main phenotype that fell into more than one Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) category (e.g., “abnormality of the nervous system” or “abnormality of the eye,” as shown in Figure S1A; flagged in Table S2 as “compounded_phenotype”), and ten of these had variants in multiple genes, each partially explaining the phenotype.

A wide variety of reportable genes and variants are identified in this cohort

The most frequently reported gene across families in the whole cohort was GNAO1 (MIM: 139311) (n = 7), followed by CACNA1A (MIM: 601011) (n = 6), KCNQ2 (MIM: 602235) (n = 6), STXBP1 (MIM: 602926) (n = 6), and SCN1A (MIM: 182389) (n = 6) (Table S4). In total, we reported 380 variants (358 unique) in 289 individuals from 276 families. 18 variants were common between affected members of the same family, and four variants were present in individuals from different families. The majority of these were SNVs (74% [279/380]), indels (14% [54/380]), and deletions (8% [31/380]). Although duplications, insertions, complex SVs, and ROHs were less frequent, in total they accounted for 4% (16/380) of the reported variants. (Table 2). Although mosaic variants were not systematically called given the coverage, five likely mosaic variants were identified in this cohort after evaluation of allelic balance and visual inspection of candidate variants in IGV: three were SNVs, and two were SVs (Figure S3).

Table 2.

Candidate variants identified by pathogenicity and type

| Type | Total | Pathogenic | Likely pathogenic | VUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNV | 279 | 48 | 84 | 147 |

| Indel | 54 | 23 | 22 | 9 |

| Deletion | 31 | 7 | 16 | 8 |

| Duplication | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Complex SV | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Large insertion | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Inversion | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| ROH | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| STR expansion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SMA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 380 | 79 | 124 | 177 |

Abbreviations: SNV, single-nucleotide variant; SV, structural variant; ROH, region of homozygosity; STR, single tandem repeat; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

The proportion of variants reported as P or LP compared with VUS varied according to variant type. Whereas this proportion was similar for SNVs, 83% of indels (45/54) and 74% of the reported deletions (23/31) were labeled as P or LP (Table 2). Duplications, large insertions, and inversions were all reported as VUSs (n = 11), reflecting the more challenging interpretation of variant effect. One ROH was identified in an individual with Angelman syndrome and deemed to be pathogenic. No STR expansions in known loci or SMA-associated variants were identified in this cohort, which was unsurprising given that most of these individuals had undergone routine genetic testing prior to enrollment in this project.

Re-analysis of the data increases diagnostic yield

The first round of variant analysis took place between March 2016 and January 2018. During this time, the gene list was under active development, and probands were analyzed with the most recent gene list available at the time. We re-analyzed the data twice while considering updated variant annotations, quality filtering strategies, and NDD-associated genes. Re-analysis in July 2018 and July 2019 increased the number of reportable variants from 265 to 329 and then to 380, respectively (Figure 1D), and it substantially increased affected individuals with reportable variants from 42% (208/489) to 59% (289/489) after 18 months.

Re-analysis identified additional reportable variants for a variety of reasons: most were in recently discovered NDD-associated genes (69% [79/115]) or were identified as a result of improvements in the pipeline (28% [32/115]), such as better transcription prioritization, inclusion of MEIs or ROHs, or improved de novo or SV calling. For example, a variant in PNPLA6 (MIM: 603197) (c.2785C>T [GenBank: NM_001166114.2] [p.Arg929Cys] in G008170) was flagged as low quality in the SNV/indel pipeline (minimum overall pass rate of 0.98%), but manual evaluation in IGV suggested that it was real; a compound-heterozygous variant in BRAT1 (MIM: 614506) was reported in one individual after new publications revealed stronger phenotypic evidence; and a deep intronic variant in TSC2 (MIM: 191092) was identified in another individual after it was reported in ClinVar. Additionally, 3.5% (4/115) of variants were in genes that follow an autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance with a previously identified single event, highlighting the importance of analyzing not only recently discovered disease-associated genes but also previously known genes that might harbor missed clinically relevant variants.

GS detects classes of variants that might be missed by other technologies

Variants for which detection by routine diagnostic technologies, such as ES and chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), is often challenging include SVs, rare intronic variants, and MT variants. Here, we describe findings involving these types of variants in this cohort, and we briefly describe ten participants to highlight the value of GS. Additional information for each participant and variant is present in the supplemental information and Table S2.

Regarding SVs, we reported a total of 31 deletions, six duplications, two inversions, three large insertions, four cxSVs, and one ROH. Importantly, 66% (31/47) of them were either smaller than standard CMA resolution (200 kbp with Affymetrix Chromosome Analysis Suite) or not detectable by CMA (e.g., inversions and insertions), underscoring the value of GS in detecting SVs cryptic to this technology. Six SVs occurred in conjunction with a SNV or indel in a known gene that follows an autosomal-recessive mode of inheritance. For example, participant 1 (G013396 in Table S2), an individual with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE), had a combination of an inversion and a missense variant in SPATA5 (MIM: 613940), which is associated with an autosomal-recessive neurodevelopmental disorder that often includes seizures (Figure S4). This example underscores the value of GS in investigating inversions, which are often neglected in genetic analyses.

Six intronic variants identified in this cohort were associated with NDDs: five splice region variants and one deep intronic variant (Table S2). The latter was in tuberous-sclerosis-affected individual who had endured a long diagnostic odyssey (participant 2 [G004131] in Table S2). A heterozygous deep intronic variant in TSC2 (MIM: 191092) was identified in 17% (4/23) of the reads, suggesting mosaicism (Figure S3B), which was later confirmed by Sanger sequencing. This variant was observed during re-analysis, after it was published and submitted to ClinVar as being associated with disease.24

Lastly, four reportable variants were identified in MT genome genes, three of which were deemed to be LP. Variants were called at different levels of heteroplasmy (from 83% to 91%) and homoplasmy, which were estimated from coverage analyses. One example was in participant 3 (G004703 in Table S2), an individual with ataxia, recurrent lactic acidosis, and myopathy. This individual had a missense variant in heteroplasmy (91% in blood) in MT-TL1 (Figure S5). This is one of the most thoroughly studied and best characterized disease-causing MT variants and is associated with, among other phenotypes, MELAS (myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes),25 which is consistent with the individual’s phenotype. The other two LP variants were in MT-ATP6, associated with neurogenic muscle weakness, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa,26 in participant 4 (G013808 in Table S2) and in MT-ND4, associated with Leber hereditary optic neuropathy with or without additional neurological abnormalities, in participant 5 (G012198 in Table S2)27,28,29 (Figures S6 and S7).

Long-read sequencing resolves complex SVs in two individuals

Five individuals with ambiguous results from srGS data were further investigated by ONT lrGS (Table 3). A total of seven runs (three in GridION for one sample and four in PromethION for the remainder) produced an average coverage of 14.6 (±7.5) reads with an average length of 4,243 bp (±4,054) (Figures S8A–S8D). After QC, 62,620 SVs were identified, an average of 26,311 ± 4,532 per individual (Figures S8E and S8F), which is consistent with results of previously reported lrGS studies.30

Table 3.

lrGS was performed on five participants to resolve cxSVs and variant phasing and to facilitate resolutions of technically challenging regions in five individuals

| Individual | Phenotype | srGS finding | Reason for including lrGS | lrGS finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 6 (NGC00375_01) | dystonia, myoclonus, delayed gross motor development, learning and intellectual disability | cxSV involving SGCE | unable to resolve by srGS, highly complex | cxSV involving 37 breakpoints |

| Participant 7 (G012664) | paroxysmal intermittent limping on right leg, bulbar palsy | cxSV involving multiple duplications | unable to resolve by srGS, highly complex | cxSV involving 26 duplicated fragments |

| Participant 8 (G013428) | severe global developmental delay, hypotonia with chorea-like movement disorder, sensorineural hearing impairment, microcephaly, delayed visual maturation with esotropia | inversion at chrX: 41,426,631–41,501,873 (GRCh37) | unable to resolve by srGS or Sanger sequencing | variant not supported by lrGS |

| Participant 9 (G013407) | EIEE | DNM1 missense variant: c.1082G>C (GenBank: NM_004408.4) (p.Arg361Pro) | haplotype phasing | inconclusive |

| Participant 10 (G000973) | early-onset dementia, spastic paraplegia, thin corpus callosum | cxSV involving KIF5C | unable to resolve by srGS, possible complex retrotransposon | retrotransposon insertion at chr5: 25,000,434 (GRCh37) (not complex, unknown effect) |

Individual IDs in parentheses correspond to those in Table S2. EIEE, early infantile epileptic encephalopathy.

Two affected individuals carried complex SVs that were resolved by lrGS. Participant 6 (NGC00375_01 in Table S2), a male with dystonia, learning difficulties, and behavioral problems, had a de novo complex SV disrupting SGCE (MIM: 604149), which is associated with dystonia. srGS had suggested that this was part of a complex SV, but resolution could not be achieved as a result of homology at the breakpoints. lrGS allowed SV characterization and resolved the complex rearrangement, which involved 37 breakpoints between chromosomes 7, 10, and 12 (Figure 2A). The variant was reported as LP.

Figure 2.

Complex structural variants resolved by lrGS

(A and B) Circular layout plot of the complex rearrangement in (A) participant 6 (NGC00375_01), involving 37 breakpoints between chromosomes 7, 10, and 12, and in (B) participant 7 (G012664), involving 26 duplicated fragments from 14 chromosomes. Both plots were generated with Circos31; the outer ring shows the chromosomes (coordinates in mbp), and the inner ring shows the depth coverage of the individual, normalized with 250 unrelated individuals in the cohort. In the scatterplot, deletions are shown in red, and duplications are shown in blue. Breakpoint junction links are shown in black (interchromosomal) and green (intrachromosomal).

(C) Variant phasing performed on participant 8 (G013428) demonstrated the absence of an inversion called in the srGS data. The ideogram for chromosome X highlighting the region involved is at the top, below which are the genes present within this region and the inversion coordinates (in green). A zoomed-in panel for both the start (S) and end (E) of the inversion are shown next for srGS and lrGS data. It is noticeable that both are located within LINE-1 retrotransposon repeats (Rep) and are not supported by lrGS data.

(D) Variant phasing performed on participant 10 (G000973) facilitated the resolution of a complex event involving a retroelement of KIF5C. The ideogram of chromosome 2 is at the top, below which are the KIF5C transcripts and a zoomed-in region with the srGS calls; deletions are shown in red, inversions are in green, and the duplication is in blue. The following two panels show the coverage (Cov) and IGV18 visualization of the short reads and the lrGS alignments. Split reads and discordant pairs are present in the srGS data and absent in the lrGS data, consistent with the retroelement insertion.

Participant 7 (G012664 in Table S2), a male with paroxysmal dyskinesia and bulbar palsy, harbored a complex rearrangement characterized by the presence of duplications across multiple chromosomes, including chromosome X. The variant had been inherited from the unaffected mother, and lrGS revealed 26 duplicated DNA fragments of 24 kb median size (SD ± 12 kb) from 14 different chromosomes (Figure 2B). Although no protein-coding gene was predicted to be disrupted, we could not rule out a possible regulatory effect of this event, and it was classified as a VUS.

Long-read sequencing phases variants and facilitates resolution of technically challenging regions in three individuals

We also used lrGS to perform variant phasing and to investigate SVs in technically challenging regions. Participant 8 (G013428 in Table S2) presented with global developmental delay, hypotonia with movement disorder, sensorineural hearing impairment, microcephaly, and delayed visual maturation with esotropia. An inversion involving CASK (MIM: 300172) was called in the srGS data (Figure 2C), but the variant could not be confirmed by long-range PCR as a result of low sequence complexity. We therefore sought to validate it by using lrGS, and the inversion was not supported by the lrGS data, suggesting that the called inversion was a false positive.

Participant 9 (G013407 in Table S2), a female with EIEE, had a heterozygous missense variant in DNM1 (MIM: 616346), which is associated with epileptic encephalopathy. The variant was absent in the unaffected father, and maternal DNA was unavailable (Figure S9). Given that 80% of de novo variants occur in the paternal allele,32 we performed lrGS to determine the haplotype of the variant. Unfortunately, the closest informative SNV was 7,048 bp from this position, and no reads of this length covered the region (average read length = 6,723 ± 4,695 bp). Therefore, the variant was classified as a VUS.

Lastly, participant 10 (G000973 in Table S2), a female with early onset dementia, spastic paraplegia, and thin corpus callosum, presented with three deletions and two inversions in KIF5C (MIM: 604593). We used lrGS to resolve this event and demonstrated that KIF5C had not been disrupted and that the calls were from a retroelement insertion of a KIF5C transcript highly expressed in the human brain (Figure 2D). Although the insertion did not affect any protein-coding gene, it was classified as a VUS given that reports have shown that retroelements can interfere with gene expression by other mechanisms, such as silencing by transcriptional or RNA interference.33

Discussion

In this study, we describe in detail the structure and outcomes of the NIHR BioResource NDD project. We employed a comprehensive approach that combined srGS and lrGS to identify a broad range of clinically relevant variants associated with NDDs. This strategy identified a high rate of causal variants, including variants often intractable to ES and CMA, throughout the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes (36%). Our diagnostic yield is within the expected range reported by similar studies3,4,34 and 3% higher than the 33% reported in a previous NIHR BioResource study as a result of re-analysis and follow-up studies.7 It is worth noting that the diagnostic yield for NDDs can vary considerably and is influenced by many factors, such as phenotype and recruitment criteria, sequencing technology, mode of inheritance, family members studied, date of analysis, and genetic ancestry. Understanding these factors can help inform recruitment strategies and study design to improve diagnostic yield. For example, we observed a slightly higher diagnostic yield for trios (41%) than for singletons (35%). This is consistent with previous studies emphasizing the importance and value of trio design.3,34 However, recruitment of both biological parents is not always possible, and our relatively high yield in singletons supports including them wherever possible.35

A notable strength of this study is how comprehensively we surveyed multiple types of variants that could be implicated with NDDs. We not only investigated coding nuclear SNVs and indels but also explored SVs, intronic variants, STR expansions, SMA status, and MT variants. However, we did not find any individual with pathogenic STRs or SMA cases, which could be for several reasons: (1) some participants might have undergone STR expansion or SMA testing prior to enrollment, resulting in a reduced likelihood of detecting such variants; (2) these are very rare causes of NDDs, and thus our study might have been underpowered to detect them; or (3) it is possible that these types of variants are identified with lower sensitivity than other classes, or they could be specifically implicated in phenotypes poorly represented within this study.

Interpretation of variants that are not SNVs or indels, such as SVs, can be particularly challenging, despite recent improvements in guidelines for interpreting CNVs.36 Pathogenic intronic and other non-coding variants are rare, and identifying and interpreting them are difficult, especially without supporting transcriptomic data from an appropriate tissue.7,37 Large-scale genome-sequencing cohorts currently underway will help improve our understanding of the distribution, features, and function of non-coding variants, facilitating easier identification of those that are pathogenic.3,7,38,39 Classes of variants that we were unable to investigate in this study include those in repetitive regions that are intractable to detection by srGS, as well as somatic or mosaic variants that generally require higher coverage sequencing for detection.

Interestingly, we identified causal variants in several clinically actionable genes. Five individuals were found to have pathogenic variants in KMT2B (MIM: 606834) and so could be responsive to treatment with deep brain stimulation.8,40 Five other individuals were found to have causal variants in SCN1A (MIM: 182389), at least three of which are predicted to cause LOF; in these cases, treatment with sodium-channel blockers can worsen seizures.41 These examples demonstrate the clinical importance of genetic diagnoses and the value of this study.

Re-analysis of sequencing data notably increased the diagnostic yield, largely because causal variants were identified in genes recently associated with NDD, as has previously been reported.34 This is an important argument for GS or ES over panel sequencing, in which any re-analysis would be limited to previously selected genes. We therefore recommend that similar studies perform regular re-analysis where possible; however, in practice, the decision of whether to re-analyze data for any given cohort, and how frequently to do so, must balance this advantage against the resource required, and it will depend partly on the number of gene-disease associations discovered since the last analysis.

Because we had no cases where both ES and GS had been performed on the same samples, we cannot directly compare these technologies, as other studies have done.23,42 Variants suspected to be cryptic to ES include the deep intronic SNV in participant 2 (G004131), the two inversions, and the three large insertions, whose breakpoints occur in intronic regions. However, using ES to detect variants in GC-rich regions and CNVs (especially small CNVs) is known to be challenging. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that additional variants would have been missed by ES. On the other hand, despite significant reductions in the cost of GS, it remains more costly than ES and is performed at lower depths than ES. This can affect some analyses, such as the detection of SVs and mosaic variants. These previously published considerations should guide selection of the optimal sequencing strategy for a given study.43

The use of lrGS in human genomics has expanded greatly over recent years, largely as a result of technological improvements along with the development of new algorithms for processing and interpreting the data.44 Applications include insights into the biology and consequences of SVs30,45 and the identification of pathogenic variants in rare diseases that are intractable to other methodologies, usually in individual cases.6,21,46,47 Here, we used lrGS to resolve complex SVs that could not be characterized by short reads in two individuals and to validate or phase variants in three additional individuals. Haplotype phasing in participant 9 (G013407) was not possible because of read-length limitation, highlighting the importance of ultra-long reads.46,48 Overall, our results give several examples of the utility of long-read sequencing. In the future, larger-scale, more systematic lrGS studies of NDDs, facilitated by further improvements to technology, algorithms, and pipelines, will yield further insights into the prevalence and biology of previously intractable pathogenic variants.

Our work demonstrates the value of GS in investigating the genetic basis of NDDs and provides insight into the genetic architecture of these disorders. We support the importance of re-analysis and demonstrate that variants cryptic to traditional technologies, such as small SVs, cxSVs, non-coding variants, and MT variants, can be captured by GS, increasing diagnostic yield. Further detailed characterization of genomic variation in large-scale GS studies will be essential for further unveiling the genetic architecture of NDDs in coding and non-coding regions of the human genome.

Consortia

The members of the NIHR BioResource are Stephen Abbs, Lara Abulhoul, Julian Adlard, Munaza Ahmed, Timothy J. Aitman, Hana Alachkar, David J. Allsup, Jeff Almeida-King, Philip Ancliff, Richard Antrobus, Ruth Armstrong, Gavin Arno, Sofie Ashford, William J. Astle, Anthony Attwood, Paul Aurora, Christian Babbs, Chiara Bacchelli, Tamam Bakchoul, Siddharth Banka, Tadbir Bariana, Julian Barwell, Joana Batista, Helen E. Baxendale, Phil L. Beales, David L. Bennett, David R. Bentley, Agnieszka Bierzynska, Tina Biss, Maria A.K. Bitner-Glindzicz, Graeme C. Black, Marta Bleda, Iulia Blesneac, Detlef Bockenhauer, Harm Bogaard, Christian J. Bourne, Sara Boyce, John R. Bradley, Eugene Bragin, Gerome Breen, Paul Brennan, Carole Brewer, Matthew Brown, Andrew C. Browning, Michael J. Browning, Rachel J. Buchan, Matthew S. Buckland, Teofila Bueser, Carmen Bugarin Diz, John Burn, Siobhan O. Burns, Oliver S. Burren, Nigel Burrows, Paul Calleja, Carolyn Campbell, Gerald Carr-White, Keren Carss, Ruth Casey, Mark J. Caulfield, Jenny Chambers, John Chambers, Melanie M.Y. Chan, Calvin Cheah, Floria Cheng, Patrick F. Chinnery, Manali Chitre, Martin T. Christian, Colin Church, Jill Clayton-Smith, Maureen Cleary, Naomi Clements Brod, Gerry Coghlan, Elizabeth Colby, Trevor R.P. Cole, Janine Collins, Peter W. Collins, Camilla Colombo, Cecilia J. Compton, Robin Condliffe, Stuart Cook, H. Terence Cook, Nichola Cooper, Paul A. Corris, Abigail Furnell, Fiona Cunningham, Nicola S. Curry, Antony J. Cutler, Matthew J. Daniels, Mehul Dattani, Louise C. Daugherty, John Davis, Anthony De Soyza, Sri V.V. Deevi, Timothy Dent, Charu Deshpande, Eleanor F. Dewhurst, Peter H. Dixon, Sofia Douzgou, Kate Downes, Anna M. Drazyk, Elizabeth Drewe, Daniel Duarte, Tina Dutt, J. David M. Edgar, Karen Edwards, William Egner, Melanie N. Ekani, Perry Elliott, Wendy N. Erber, Marie Erwood, Maria C. Estiu, Dafydd Gareth Evans, Gillian Evans, Tamara Everington, Mélanie Eyries, Hiva Fassihi, Remi Favier, Jack Findhammer, Debra Fletcher, Frances A. Flinter, R. Andres Floto, Tom Fowler, James Fox, Amy J. Frary, Courtney E. French, Kathleen Freson, Mattia Frontini, Daniel P. Gale, Henning Gall, Vijeya Ganesan, Michael Gattens, Claire Geoghegan, Terence S.A. Gerighty, Ali G. Gharavi, Stefano Ghio, Hossein-Ardeschir Ghofrani, J. Simon R. Gibbs, Kate Gibson, Kimberly C. Gilmour, Barbara Girerd, Nicholas S. Gleadall, Sarah Goddard, David B. Goldstein, Keith Gomez, Pavels Gordins, David Gosal, Stefan Gräf, Jodie Graham, Luigi Grassi, Daniel Greene, Lynn Greenhalgh, Andreas Greinacher, Paolo Gresele, Philip Griffiths, Sofia Grigoriadou, Russell J. Grocock, Detelina Grozeva, Mark Gurnell, Scott Hackett, Charaka Hadinnapola, William M. Hague, Rosie Hague, Matthias Haimel, Matthew Hall, Helen L. Hanson, Eshika Haque, Kirsty Harkness, Andrew R. Harper, Claire L. Harris, Daniel Hart, Ahamad Hassan, Grant Hayman, Alex Henderson, Archana Herwadkar, Jonathan Hoffman, Simon Holden, Rita Horvath, Henry Houlden, Arjan C. Houweling, Luke S. Howard, Fengyuan Hu, Gavin Hudson, Joseph Hughes, Aarnoud P. Huissoon, Marc Humbert, Sean Humphray, Sarah Hunter, Matthew Hurles, Melita Irving, Louise Izatt, Roger James, Sally A. Johnson, Stephen Jolles, Jennifer Jolley, Dragana Josifova, Neringa Jurkute, Tim Karten, Johannes Karten, Mary A. Kasanicki, Hanadi Kazkaz, Rashid Kazmi, Peter Kelleher, Anne M. Kelly, Wilf Kelsall, Carly Kempster, David G. Kiely, Nathalie Kingston, Robert Klima, Nils Koelling, Myrto Kostadima, Gabor Kovacs, Ania Koziell, Roman Kreuzhuber, Taco W. Kuijpers, Ajith Kumar, Dinakantha Kumararatne, Manju A. Kurian, Michael A. Laffan, Fiona Lalloo, Michele Lambert, Hana Lango Allen, Allan Lawrie, D. Mark Layton, Nick Lench, Claire Lentaigne, Tracy Lester, Adam P. Levine, Rachel Linger, Hilary Longhurst, Lorena E. Lorenzo, Eleni Louka, Paul A. Lyons, Rajiv D. Machado, Robert V. MacKenzie Ross, Bella Madan, Eamonn R. Maher, Jesmeen Maimaris, Samantha Malka, Sarah Mangles, Rutendo Mapeta, Kevin J. Marchbank, Stephen Marks, Hugh S. Markus, Hanns-Ulrich Marschall, Andrew Marshall, Jennifer Martin, Mary Mathias, Emma Matthews, Heather Maxwell, Paul McAlinden, Mark I. McCarthy, Harriet McKinney, Aoife McMahon, Stuart Meacham, Adam J. Mead, Ignacio Medina Castello, Karyn Megy, Sarju G. Mehta, Michel Michaelides, Carolyn Millar, Shehla N. Mohammed, Shahin Moledina, David Montani, Anthony T. Moore, Joannella Morales, Nicholas W. Morrell, Monika Mozere, Keith W. Muir, Andrew D. Mumford, Andrea H. Nemeth, William G. Newman, Michael Newnham, Sadia Noorani, Paquita Nurden, Jennifer O’Sullivan, Samya Obaji, Chris Odhams, Steven Okoli, Andrea Olschewski, Horst Olschewski, Kai Ren Ong, S. Helen Oram, Elizabeth Ormondroyd, Willem H. Ouwehand, Claire Palles, Sofia Papadia, Soo-Mi Park, David Parry, Smita Patel, Joan Paterson, Andrew Peacock, Simon H. Pearce, John Peden, Kathelijne Peerlinck, Christopher J. Penkett, Joanna Pepke-Zaba, Romina Petersen, Clarissa Pilkington, Kenneth E.S. Poole, Radhika Prathalingam, Bethan Psaila, Angela Pyle, Richard Quinton, Shamima Rahman, Stuart Rankin, Anupama Rao, F. Lucy Raymond, Paula J. Rayner-Matthews, Christine Rees, Augusto Rendon, Tara Renton, Christopher J. Rhodes, Andrew S.C. Rice, Sylvia Richardson, Alex Richter, Leema Robert, Irene Roberts, Anthony Rogers, Sarah J. Rose, Robert Ross-Russell, Catherine Roughley, Noemi B.A. Roy, Deborah M. Ruddy, Omid Sadeghi-Alavijeh, Moin A. Saleem, Nilesh Samani, Crina Samarghitean, Alba Sanchis-Juan, Ravishankar B. Sargur, Robert N. Sarkany, Simon Satchell, Sinisa Savic, John A. Sayer, Genevieve Sayer, Laura Scelsi, Andrew M. Schaefer, Sol Schulman, Richard Scott, Marie Scully, Claire Searle, Werner Seeger, Arjune Sen, W.A. Carrock Sewell, Denis Seyres, Neil Shah, Olga Shamardina, Susan E. Shapiro, Adam C. Shaw, Patrick J. Short, Keith Sibson, Lucy Side, Ilenia Simeoni, Michael A. Simpson, Matthew C. Sims, Suthesh Sivapalaratnam, Damian Smedley, Katherine R. Smith, Kenneth G.C. Smith, Katie Snape, Nicole Soranzo, Florent Soubrier, Laura Southgate, Olivera Spasic-Boskovic, Simon Staines, Emily Staples, Hannah Stark, Jonathan Stephens, Charles Steward, Kathleen E. Stirrups, Alex Stuckey, Jay Suntharalingam, Emilia M. Swietlik, Petros Syrris, R. Campbell Tait, Kate Talks, Rhea Y.Y. Tan, Katie Tate, John M. Taylor, Jenny C. Taylor, James E. Thaventhiran, Andreas C. Themistocleous, Ellen Thomas, David Thomas, Moira J. Thomas, Patrick Thomas, Kate Thomson, Adrian J. Thrasher, Glen Threadgold, Chantal Thys, Tobias Tilly, Marc Tischkowitz, Catherine Titterton, John A. Todd, Cheng-Hock Toh, Bas Tolhuis, Ian P. Tomlinson, Mark Toshner, Matthew Traylor, Carmen Treacy, Paul Treadaway, Richard Trembath, Salih Tuna, Wojciech Turek, Ernest Turro, Philip Twiss, Tom Vale, Chris Van Geet, Natalie van Zuydam, Maarten Vandekuilen, Anthony M. Vandersteen, Marta Vazquez-Lopez, Julie von Ziegenweidt, Anton Vonk Noordegraaf, Annette Wagner, Quinten Waisfisz, Suellen M. Walker, Neil Walker, Klaudia Walter, James S. Ware, Hugh Watkins, Christopher Watt, Andrew R. Webster, Lucy Wedderburn, Wei Wei, Steven B. Welch, Julie Wessels, Sarah K. Westbury, John-Paul Westwood, John Wharton, Deborah Whitehorn, James Whitworth, Andrew O.M. Wilkie, Martin R. Wilkins, Catherine Williamson, Brian T. Wilson, Edwin K.S. Wong, Nicholas Wood, Yvette Wood, Christopher Geoffrey Woods, Emma R. Woodward, Stephen J. Wort, Austen Worth, Michael Wright, Katherine Yates, Patrick F.K. Yong, Timothy Young, Ping Yu, Patrick Yu-Wai-Man, and Eliska Zlamalova

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants involved in this study and their families. This work was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) for the NIHR BioResource project (RG65966). This work was partly funded by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. This research was supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.-J., K.C., and F.L.R.; data curation, A.S.-J., K.M., L.C.D., and K.C.; formal analysis: A.S.-J. and K.C.; funding acquisition, NIHR and F.L.R.; investigation, A.S.-J., K.M., C.A.R., K.L., C.E.F., D.G., L.C.D., K.C., and F.L.R.; methodology, A.S.-J., K.C., and F.L.R.; project administration, K.S., E.D., and M.E.; resources, A.M.T., S.T.D., A.H.-F., J.V., G.A., M.C., D.J., M.A.K., A.P., J.R., E.R., E.W., E.W., and C.G.W.; software, A.S.-J., C.P., O.S., S.T., and N.G.; supervision, K.C. and F.L.R.; validation, J.S.; visualization, A.S.-J.; writing – original draft, A.S.-J. and K.C.; writing – review & editing, A.S.-J., K.C., and F.L.R.

Declaration of interests

K.J.C. and K.M. are currently employees of AstraZeneca.

Published: August 3, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.07.007.

Contributor Information

F. Lucy Raymond, Email: flr24@cam.ac.uk.

Keren J. Carss, Email: keren.carss@astrazeneca.com.

Web resources

European Genome-Phenome Archive, https://ega-archive.org/

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The genome data generated during this study are available in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA) under accession number EGA: EGAD00001004522 (https://ega-archive.org/datasets/EGAD00001004522).

References

- 1.Boycott K.M., Hartley T., Biesecker L.G., Gibbs R.A., Innes A.M., Riess O., Belmont J., Dunwoodie S.L., Jojic N., Lassmann T., et al. A diagnosis for all rare genetic diseases: the horizon and the next frontiers. Cell. 2019;177:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature. 2017;542:433–438. doi: 10.1038/nature21062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.100000 Genomes Project Pilot Investigators. Smedley D., Smith K.R., Martin A., Thomas E.A., McDonagh E.M., Cipriani V., Ellingford J.M., Arno G., Tucci A., et al. 100,000 Genomes pilot on rare-disease diagnosis in health care - preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:1868–1880. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark M.M., Stark Z., Farnaes L., Tan T.Y., White S.M., Dimmock D., Kingsmore S.F. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genom. Med. 2018;3:16. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0053-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belyeu J.R., Brand H., Wang H., Zhao X., Pedersen B.S., Feusier J., Gupta M., Nicholas T.J., Brown J., Baird L., et al. De novo structural mutation rates and gamete-of-origin biases revealed through genome sequencing of 2,396 families. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021;108:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsuhashi S., Matsumoto N. Long-read sequencing for rare human genetic diseases. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;65:11–19. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turro E., Astle W.J., Megy K., Gräf S., Greene D., Shamardina O., Allen H.L., Sanchis-Juan A., Frontini M., Thys C., et al. Whole-genome sequencing of patients with rare diseases in a national health system. Nature. 2020;583:96–102. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2434-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer E., Carss K.J., Rankin J., Nichols J.M.E., Grozeva D., Joseph A.P., Mencacci N.E., Papandreou A., Ng J., Barral S., et al. Mutations in the histone methyltransferase gene KMT2B cause complex early-onset dystonia. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:223–237. doi: 10.1038/ng.3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helbig K.L., Lauerer R.J., Bahr J.C., Souza I.A., Myers C.T., Uysal B., Schwarz N., Gandini M.A., Huang S., Keren B., et al. De novo pathogenic variants in CACNA1E cause developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with contractures, macrocephaly, and dyskinesias. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;103:666–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito Y., Carss K.J., Duarte S.T., Hartley T., Keren B., Kurian M.A., Marey I., Charles P., Mendonça C., Nava C., et al. De novo truncating mutations in WASF1 cause intellectual disability with seizures. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;103:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchis-Juan A., Hasenahuer M.A., Baker J.A., McTague A., Barwick K., Kurian M.A., Duarte S.T., NIHR BioResource. Carss K.J., Thornton J., Raymond F.L. Structural analysis of pathogenic missense mutations in GABRA2 and identification of a novel de novo variant in the desensitization gate. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1106. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobreira N., Schiettecatte F., Valle D., Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:928–930. doi: 10.1002/humu.22844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin A.R., Williams E., Foulger R.E., Leigh S., Daugherty L.C., Niblock O., Leong I.U.S., Smith K.R., Gerasimenko O., Haraldsdottir E., et al. PanelApp crowdsources expert knowledge to establish consensus diagnostic gene panels. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:1560–1565. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright C.F., Fitzgerald T.W., Jones W.D., Clayton S., McRae J.F., van Kogelenberg M., King D.A., Ambridge K., Barrett D.M., Bayzetinova T., et al. Genetic diagnosis of developmental disorders in the DDD study: a scalable analysis of genome-wide research data. Lancet. 2015;385:1305–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61705-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenson P.D., Ball E.V., Mort M., Phillips A.D., Shiel J.A., Thomas N.S.T., Abeysinghe S., Krawczak M., Cooper D.N. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®): 2003 update. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:577–581. doi: 10.1002/humu.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., Brown G.R., Chao C., Chitipiralla S., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W., et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1062–D1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Wenger A.M., Zehir A., Mesirov J.P. Variant review with the Integrative Genomics Viewer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e31–e34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rimmer A., Phan H., Mathieson I., Iqbal Z., Twigg S.R.F., WGS500 Consortium. Wilkie A.O.M., McVean G., Lunter G. Integrating mapping-assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:912–918. doi: 10.1038/ng.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French C.E., Delon I., Dolling H., Sanchis-Juan A., Shamardina O., Mégy K., Abbs S., Austin T., Bowdin S., Branco R.G., et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals that genetic conditions are frequent in intensively ill children. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:627–636. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05552-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de la Morena-Barrio B., Stephens J., de la Morena-Barrio M.E., Stefanucci L., Padilla J., Miñano A., Gleadall N., García J.L., López-Fernández M.F., Morange P.E., et al. Long-read sequencing identifies the first retrotransposon insertion and resolves structural variants causing antithrombin deficiency. Thromb. Haemost. 2022;122:1369–1378. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1749345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchis-Juan A., Bitsara C., Low K.Y., Carss K.J., French C.E., Spasic-Boskovic O., Jarvis J., Field M., Raymond F.L., Grozeva D. Rare genetic variation in 135 families with family history suggestive of X-linked intellectual disability. Front. Genet. 2019;10:578. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carss K.J., Arno G., Erwood M., Stephens J., Sanchis-Juan A., Hull S., Megy K., Grozeva D., Dewhurst E., Malka S., et al. Comprehensive rare variant analysis via whole-genome sequencing to determine the molecular pathology of inherited retinal disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nellist M., Brouwer R.W.W., Kockx C.E.M., van Veghel-Plandsoen M., Withagen-Hermans C., Prins-Bakker L., Hoogeveen-Westerveld M., Mrsic A., van den Berg M.M.P., Koopmans A.E., et al. Targeted next generation sequencing reveals previously unidentified TSC1 and TSC2 mutations. BMC Med. Genet. 2015;16:10. doi: 10.1186/s12881-015-0155-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman S., Poulton J., Marchington D., Suomalainen A. Decrease of 3243 A→G mtDNA mutation from blood in MELAS syndrome: a longitudinal study. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:238–240. doi: 10.1086/316930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Gallardo E., Emperador S., Solano A., Llobet L., Martín-Navarro A., López-Pérez M.J., Briones P., Pineda M., Artuch R., Barraquer E., et al. Expanding the clinical phenotypes of MT-ATP6 mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:6191–6200. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu-Wai-Man P., Chinnery P.F. In: GeneReviews((R)) Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Pagon R.A., Wallace S.E., Bean L.J.H., Gripp K.W., Mirzaa G.M., Amemiya A., editors. 1993. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami T., Mita S., Tokunaga M., Maeda H., Ueyama H., Kumamoto T., Uchino M., Ando M. Hereditary cerebellar ataxia with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy mitochondrial DNA 11778 mutation. J. Neurol. Sci. 1996;142:111–113. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grazina M.M., Diogo L.M., Garcia P.C., Silva E.D., Garcia T.D., Robalo C.B., Oliveira C.R. Atypical presentation of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy associated to mtDNA 11778G>A point mutation—a case report. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2007;11:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beyter D., Ingimundardottir H., Oddsson A., Eggertsson H.P., Bjornsson E., Jonsson H., Atlason B.A., Kristmundsdottir S., Mehringer S., Hardarson M.T., et al. Long-read sequencing of 3,622 Icelanders provides insight into the role of structural variants in human diseases and other traits. Nat. Genet. 2021;53:779–786. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., Jones S.J., Marra M.A. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acuna-Hidalgo R., Veltman J.A., Hoischen A. New insights into the generation and role of de novo mutations in health and disease. Genome Biol. 2016;17:241. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaer K., Speek M. Retroelements in human disease. Gene. 2013;518:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright C.F., Campbell P., Eberhardt R.Y., Aitken S., Perrett D., Brent S., Danecek P., Gardner E.J., Chundru V.K., Lindsay S.J., et al. Optimising diagnostic yield in highly penetrant genomic disease. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.07.25.22278008. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grozeva D., Carss K., Spasic-Boskovic O., Tejada M.I., Gecz J., Shaw M., Corbett M., Haan E., Thompson E., Friend K., et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing analysis of 1,000 individuals with intellectual disability. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:1197–1204. doi: 10.1002/humu.22901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riggs E.R., Andersen E.F., Cherry A.M., Kantarci S., Kearney H., Patel A., Raca G., Ritter D.I., South S.T., Thorland E.C., et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Genet. Med. 2020;22:245–257. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Short P.J., McRae J.F., Gallone G., Sifrim A., Won H., Geschwind D.H., Wright C.F., Firth H.V., FitzPatrick D.R., Barrett J.C., Hurles M.E. De novo mutations in regulatory elements in neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature. 2018;555:611–616. doi: 10.1038/nature25983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The All of Us Research Program Investigators. Denny J.C., Rutter J.L., Goldstein D.B., Philippakis A., Smoller J.W., Jenkins G., Dishman E. The "All of Us" research program. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:668–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halldorsson B.V., Eggertsson H.P., Moore K.H.S., Hauswedell H., Eiriksson O., Ulfarsson M.O., Palsson G., Hardarson M.T., Oddsson A., Jensson B.O., et al. The sequences of 150,119 genomes in the UK Biobank. Nature. 2022;607:732–740. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04965-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dafsari H.S., Sprute R., Wunderlich G., Daimagüler H.S., Karaca E., Contreras A., Becker K., Schulze-Rhonhof M., Kiening K., Karakulak T., et al. Novel mutations in KMT2B offer pathophysiological insights into childhood-onset progressive dystonia. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;64:803–813. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziobro J., Eschbach K., Sullivan J.E., Knupp K.G. Current treatment strategies and future treatment options for Dravet syndrome. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2018;20:52. doi: 10.1007/s11940-018-0537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowther C., Valkanas E., Giordano J.L., Wang H.Z., Currall B.B., O’Keefe K., Pierce-Hoffman E., Kurtas N.E., Whelan C.W., Hao S.P., et al. Systematic evaluation of genome sequencing for the assessment of fetal structural anomalies. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.12.248526. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavelle T.A., Feng X., Keisler M., Cohen J.T., Neumann P.J., Prichard D., Schroeder B.E., Salyakina D., Espinal P.S., Weidner S.B., Maron J.L. Cost-effectiveness of exome and genome sequencing for children with rare and undiagnosed conditions. Genet. Med. 2022;24:2415–2417. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Logsdon G.A., Vollger M.R., Eichler E.E. Long-read human genome sequencing and its applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020;21:597–614. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-0236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins R.L., Brand H., Karczewski K.J., Zhao X., Alföldi J., Francioli L.C., Khera A.V., Lowther C., Gauthier L.D., Wang H., et al. A structural variation reference for medical and population genetics. Nature. 2020;581:444–451. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2287-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchis-Juan A., Stephens J., French C.E., Gleadall N., Mégy K., Penkett C., Shamardina O., Stirrups K., Delon I., Dewhurst E., et al. Complex structural variants in Mendelian disorders: identification and breakpoint resolution using short- and long-read genome sequencing. Genome Med. 2018;10:95. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0606-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thibodeau M.L., O'Neill K., Dixon K., Reisle C., Mungall K.L., Krzywinski M., Shen Y., Lim H.J., Cheng D., Tse K., et al. Improved structural variant interpretation for hereditary cancer susceptibility using long-read sequencing. Genet. Med. 2020;22:1892–1897. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0880-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jain M., Koren S., Miga K.H., Quick J., Rand A.C., Sasani T.A., Tyson J.R., Beggs A.D., Dilthey A.T., Fiddes I.T., et al. Nanopore sequencing and assembly of a human genome with ultra-long reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The genome data generated during this study are available in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA) under accession number EGA: EGAD00001004522 (https://ega-archive.org/datasets/EGAD00001004522).