Abstract

Objective:

This narrative review discusses several studies that demonstrated the effect of self-care acupressure, especially on maternal-health problems in antenatal, labor, and postpartum times, as well as the mechanism of acupressure, the points used, and treatment strategies to support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) program in the health sector.

Methods:

PubMed and Google Scholar were searched for randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews/meta-analyses from the date of their inception to February 2022.

Results:

The 14 studies that were included showed the possibility that acupressure could have a positive impact on maternal health. This self-care can be the main alternative in overcoming the gap in solving health problems in the world.

Conclusions:

Self-care acupressure at various acupoints has been shown to be feasible to reduce problems during antenatal, labor, and postpartum times. Additional research on the use of acupressure during pregnancy and cross-sectional collaboration to increase the awareness of acupressure techniques are needed.

Keywords: acupressure, maternal health, self-care, Sustainable Development Goals

INTRODUCTION

The United Nations (UN) has planned a global action to be achieved by 2030. The action is a program called Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which has 17 scopes to end poverty, inequality, and protect the environment.1 With respect to health, the UN has planned SDG 3: “Ensuring a Healthy Life and Promoting Well-Being for All Ages,” which is a goal that has a broad scope and is connected to other SDG scopes.2 SDG 3 also emphasizes universal health coverage in the context of efforts for equitable distribution of health throughout the world. This article focuses on parts 3.7, and 3.8 of SDG 3. These parts are designed to ensure sexual- and reproductive-health care services along with universal health coverage, including protection from financial risk; access to quality essential health-care services; and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all people.3

Sexual and reproductive health and rights emphasize 5 important aspects in the Global Reproductive Health Strategy, including improving antenatal, delivery, postpartum, and newborn care; providing high-quality services for family planning, including infertility services; eliminating unsafe abortion; combating sexually transmitted infectious, and promoting sexual health.4 In 2017, it was estimated that 810 women in the world died every day due to complications related to pregnancy and childbirth.5 In developing countries, such as Indonesia, the maternal mortality rate in 2015 reached 305 per 100,000 live births.6 Most of the causes of this high maternal-mortality rate can actually be prevented and arise due to low resources.5

The main obstacle to SDG 3 in the world is the uneven distribution of health workers, infrastructure, geographical locations, and technology. One of the efforts to overcome this problem is to foster self-care for the community. Self-care interventions are among the most-promising and exciting new approaches to improving health and well-being, both from a health-systems perspective and for people who might use these interventions. Self-care is the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and to cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health-care provider.7

One of the options for self-care is acupressure, a technique of applying pressure to acupoints, using a fingertip or device with a duration of 2–3 minutes per acupoint.8 In the area of sexual and reproductive health, there are many studies on acupressure as a therapy that treats symptoms. This therapy tends to be safe and noninvasive, and can be applied easily by the general public.9

It is necessary to distinguish between acupressure and acupuncture. Acupressure is a noninvasive alternative therapy with similar therapeutic principles as acupuncture, but without needle insertions.10

Melzack and Wall introduced the Gate Control Theory to explain the mechanism of action of acupressure.11 Pressure on the acupuncture points induces brain stimulation 4 times faster than pain stimulation. The continuous impulses will cause the nerve gates to close and increase the body's pain threshold. Acupressure also activates small myelinated nerves in the muscles and transmits this stimulation to higher nerve levels. The biochemical mechanisms of acupressure lead to complex neurohormonal responses, causing an increase in cortisol production and inducing a relaxation response. In addition, there is also modulation of physiologic responses by increasing transmission of endorphins and serotonin to the brain and specific organs. Myelinated neural fibers are activated and stimulate the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, causing release of b-endorphins from the hypothalamus into the spinal fluid and the pituitary gland, and into the blood, respectively, by activating an acupuncture point. Thus, the analgesic and sedative effect of b-endorphins facilitates normal respiratory function of the patient.11

Acupressure can also enhance physical performance and overcome fatigue by mediating nitric oxide (NO)–signaling, which is known to improve local microcirculation via cyclic guanosine monophosphate.12

Acupressure has been shown to be a feasible form of self-care therapy. This is in line with the SDG 3 to be achieved in 2030, which focuses on self-care. This literature review discusses the benefits of self-care acupressure, especially for maternal health in antenatal, labor, and postpartum times.

METHODS

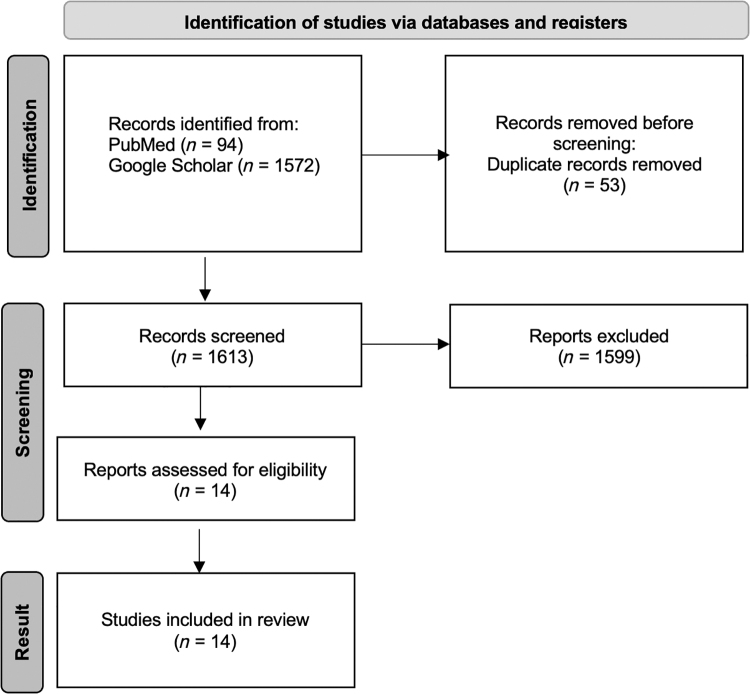

PubMed and Google Scholar were searched, from the date of their inception to February 2022, for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews/meta-analyses. The search was limited to studies published in English using the key terms acupressure, hyperemesis gravidarum, low back pain, pain relief in labor, mood disorder, preeclampsia, breastfeeding, and post-partum hemorrhage. Animal studies and articles about acupressure in pregnancy that did not involve evidence-based medicine were excluded. Figure 1 shows the search strategy scheme.

FIG. 1.

Search strategy scheme.

RESULTS

The literature search described in the Methods section yielded 1613 studies in the initial search. After screening, 14 studies met the inclusion criteria for this literature review. However, for postpartum hemorrhage, the study chosen was about acupuncture because there were no studies related to acupressure on postpartum hemorrhage. In theory, a similar effect can also be achieved by applying pressure to the same acupuncture points. Table 1 provides details on the 14 included studies.

Table 1.

Summary of the 14 Included Studies

| 1st author, year& ref. | Treatment | Intervention protocol | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal problems | ||||

| Nausea & vomiting | ||||

| Mobarakabadi et al., 202013 |

Acupressure Placebo Control |

Acupressure from Sea-Band® bracelets for 3-d Acupoint: PC-6 |

Acupressure vs. placebo vs. control Nausea frequency: SMD: −4.80 ± 4.21 vs. −2.31 ± 2.51 vs. 0.70 ± 1.40 Nausea duration: SMD: −82.68 ± 141.61 vs. −46.92 ± 104.00 vs. −11.00 ± 64.00 Nausea severity: SMD: −13.10 ± 13.90 vs. −6.71 ± 6.31 vs. 1.20 ± 4.40 Vomiting frequency: SMD: −1.62 ± 2.42 vs. −1.24 ± 1.82 vs. −0.23 ± 0.67 |

PC-6 acupressure was superior to placebo & control. |

| Tara et al., 202014 |

Acupressure Sham Medication |

Acupressure was applied 4 × /d for 4 d; each treatment was 10 min. Acupoint: PC-6 |

Rhodes Index Acupressure group had more-significant differences in severity outcomes than sham & medication groups (P < 0.001) |

PC-6 acupressure was superior to sham & medication. |

| Adlan et al., 201710 |

Acupressure Control |

Wristbands were worn for 12 hr/d for 3 d Acupoint: PC-6 |

Acupressure vs. control PUQE scoring system d 3: 4.40 ± 1.63 vs. 7.10 ± 1.61; P < 0.001 Hospital LOS (d): 2.83 ± 0.62 vs. 3.88 ± 0.87; P < 0.001 |

PC-6 acupressure on inpatients lowered PUQE scores significantly & reduced hospital LOS more than control. |

| Low-back pain | ||||

| Li et al., 202119 |

Acupressure Massage Physical therapy Usual care |

Acupoints: BL-40, GB-30, BL-57, BL-25, GB-34, BL-60, BL-54, BL-37 & BL-23 |

Acupressure vs. massage SMD: −1.92; 95% CI: −3.09, −0.76; P = 0.001 Acupressure vs. physical therapy SMD: −0.88; 95% CI, −1.10, −0.65; P < 0.00001 Acupressure vs. usual care SMD: −0.32; 95% CI, −0.61 to −0.02; P = 0.04 |

Acupressure was an effective treatment for LBP |

| Mood disorders | ||||

| Yeung et al., 201822 |

Acupressure Sleep-hygiene education |

Subjects were taught to practice self-administered acupressure daily (∼ 12–20 min) every night for 30 min for 4 wk or advised to follow sleep-hygiene education. Acupoints: GV-20, GB-20, PC-6, HT-7, CV-12 & KI-1 |

ISI score: Effect size = 0.56; P = 0.03 | Self-administered acupressure, taught in a short training course, reduced insomnia. |

| Lin et al., 202223 |

Acupressure Sham control Standard control |

RCTs or single-group trials compared acupressure with control methods or with baselines in people with depression. Acupoints: ST-36, SP-6 & HT-7 |

SMD for depression: −0.58; 95% CI: -0.85, −0.32; P < 0.0001 SMD for anxiety: −0.67; 95% CI: −0.99, −0.36; P < 0.0001 |

Evidence of acupressure for mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms was significant. |

| Preeclampsia | ||||

| Lin et al., 201625 |

Acupressure Sham |

Acupressure was applied & held for 5 sec. and then released for 1 sec. This hold–release pattern was repeated 30 × in 3 min. Acupoint: LR-3 |

Significant difference in SBP and DBP between the experimental & control groups immediately & 15 & 30 min after acupressure (P < 0.05) | Acupressure on the LR-3 lowered BP in hypertensive patients and may be included in nursing-care plans for hypertension. However, additional studies are needed to determine the optimal dosage, frequency, and long-term effects of this therapy |

| Mardiyanti, 201726 |

Acupressure Control |

Acupressure was performed on intervention group for 15–30 min. No Intervention was given to the control group. Acupoints: LR-2 & LR-3 |

Significant difference in the intervention group P = 0.000; < α 0.05 for the systole (MD: −11.33 ± 8,165) & P = 0.003 < α 0.05 for the diastole (MD: −6.67 ± 8.281) |

Acupressure at LR-3 & LR-2 reduced BP of pregnant mothers with preeclampsia; & is recommended as a nonpharmacologic therapy to reduce BP |

| Labor problems | ||||

| Pain | ||||

| Turkmen et al., 202029 |

Acupressure Control |

Acupressure was applied to SP-6 in the experimental group, and the SP-6 point of the control group was touched during each contraction at the active & transitional stages of labor |

Labor pain: 7.17 + 0.89 vs. 7.66 + 0.71; P = 0.002 |

Acupressure on SP-6 had a positive effect on pregnant women's labor experience, reduced labor pain & shortened the 1st stage of labor, compared to touch on SP-6. |

| Chen et al., 202032 |

Acupressure + standard procedures Sham + standard procedures Standard procedures alone |

Acupressure + standard procedures for labor management significantly reduced pain sensation, compared with sham acupressure + standard procedures & with standard procedures alone. Acupoints: SP-6 & LI-4 |

Immediate analgesic effect of acupressure persisted for at least 60 min (all P < 0.01). Compared with untreated control groups, the acupressure group had shorter labor, especially the 1st stage (SMD: −0.76; 95% CI: −1.10, −0.43; P < 0.001; I2 = 74%) & 2nd stage (SMD: −0.37; 95% CI = −0.59, −0.18; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%) |

Moderate evidence indicated that acupressure may have promising effects on labor pain and duration. |

| Postpartum problems | ||||

| Postpartum hemorrhage | ||||

| López-Garrido et al., 201533 | Verum acupuncture Sham |

The umbilical cord was clamped; the abdominal area was disinfected with antiseptic & an acupuncture needle was placed in CV-6. After the midwife removed the placenta & measured the time, the acupuncture needle was removed & the abdominal area was completely sterilized Acupoint: CV-6 |

Placental expulsion time Verum acupuncture: 5.23 ± 1.99 min Sham: 15.21 ± 7.01 min |

Acupuncture decreased time to placental expulsion and induced contractions of the uterus. Reduction of the 3rd stage of labor may reduce risk of postpartum hemorrhage. |

| Liu et al., 200834 |

EA + medication Medication only | EA was applied for 30 min with sparse–dense waves at 2/100 Hz, combined with medication (500 mL of 0.5% glucose added with 2.5 units of i.v. oxytocin). Acupoint: LI-4 |

Total effective rate EA + medication: 134 (97.10%) Medication only: 97 (70.30%) Apgar score 1 min after birth EA + medication: 9.86 ± 0.57 Medication only: 9.70 ± 1.02 |

EA at LI-4 + medication was superior to medication alone for intensifying uterine contractions. |

| Breastfeeding | ||||

| Sulymbona et al., 202038 |

Acupressure Control |

Acupressure was performed 3 times/wk for 3 wks. No intervention was given to the control group. Acupoints: CV-18, ST-17 & S-I1 |

Significant difference on volume of breast milk between intervention on last visit of intervention (MD: 489.74 ± 42.68) & control group (MD: 297.85 ± 90.25) | Acupressure at CV-18, ST-17 & SI-1 3 × /wk for 3 weeks increased breast-milk production in postpartum mothers. |

| Hajian et al., 202139 |

Acupressure Acupuncture Massage |

This was a systematic review of RCTs, clinical studies, both randomized & nonrandomized, either retrospective or prospective & review articles on the effect of acupuncture, acupressure, & massage techniques on breast engorgement & breast-milk volume. Acupoints: GB-21, LI-4, S-I1, ST-17 & CV-18 |

Acupressure + oxytocin massage vs. controlSMD: 282.31+ (282.31 + 15.35 vs. 218.08 + 36.62) Acupressure vs. compress on breast hyperemia (Kamali Moradzade et al. study, 201337) Right breast SMD: 5.94 ± 2.48 vs. 8.53 ± 2.48, respectively Left breast SMD: 5.5 ± 2.3 vs. 7.79 ± 3.95, respectively |

Acupressure & acupuncture decreased breast engorgement & breast pain in lactating mothers. |

SMD, standardized mean difference; d, day(s); min, minute(s); hr, hour(s); PUQE: Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis; LOS, length of stay; CI, confidence interval; LBP, low-back pain; wk, wk(s); ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; sec, seconds; SBP, systolic blood pressure, DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BP, blood pressure; MD, mean difference; EA, electroacupuncture; i.v., intravenous.

DISCUSSION

Acupressure for Antenatal Problems

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are the most-common problems in pregnancy. Approximately 50%–80% of women reported this happening between 6 and 12 weeks of pregnancy. Twenty percent of cases can persist until the twentieth week of pregnancy.13–15 Some women experience frequent and severe nausea, known as hyperemesis gravidarum.14

Pressure stimulation at PC-6 is effective for treating nausea and vomiting. PC-6 is located on the anterior aspect of the forearm, between the 2 tendons, 3.1 fingerbreadths proximal to the wrist.10,16

Mobarakabadi et al., recruited 75 pregnant women with a gestational age of under 20 weeks who experienced mild and moderate nausea and vomiting.13 The study compared the effect of PC-6 acupressure using a Sea-Band® bracelet versus placebo and a control condition. After 3 days of the intervention, there was a significant reduction in the frequency, duration, and severity of nausea and also in the frequency of vomiting (all P < 0.001).13

Another trial on 90 women with singleton pregnancies that were earlier than 12 weeks was conducted by Tara et al, in 2020.14 The patients were randomized into 3 groups of (1) PC-6 acupressure, (2) sham acupressure, and (3) medication with vitamin B6 and metoclopramide. PC-6 acupressure was applied for 10 minutes 4 times per day. A Rhodes Index was used to measure nausea, retching, and vomiting frequency; distress from nausea, retching, and vomiting; and the amount of vomiting. After the intervention, there was significantly different severity outcomes in the 3 groups.14

In 2017, Adlan et al. conducted a trial that included 120 women with singleton pregnancies, who were randomized into 2 groups.10 In the intervention group, acupressure was applied, using a wristband placed on PC-6 for 12 hours per day for a total 3 days. The researchers concluded that pressing PC-6 reduced the symptoms of nausea and vomiting and the value of ketonuria in the treatment group, compared to the placebo group.10

Low-back pain in pregnancy

Low-back pain (LBP) in pregnant women is one of the main complaints experienced during pregnancy. It is estimated that more than 50% of pregnant women experience LBP. Despite its prevalence, it is considered to be a normal phenomenon experienced in pregnancy.17 The exact cause of LBP in pregnancy is difficult to understand because LBP is considered to be multifactorial and is associated with biomechanical, vascular, and hormonal changes.18

Acupressure is one of the nonpharmacologic options for treating LBP. Acupoints used to treat LBP are BL-40, GB-30, BL-57, BL-25, GB-34, BL-60, BL-54, BL-37, and BL-23. In a 2021 study,19 acupressure was superior to tu'ina massage on response rate (relative risk [RR]: 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.16, 1.35; P < 0.00001) and in the standardized mean difference (SMD) for pain reduction (SMD: −1.92; 95% CI: −3.09, −0.76; P = 0.001). Likewise, acupressure was superior to physical therapy (SMD: −0.88; 95% CI: −1.10, −0.65; P < 0.00001) and to usual care (SMD: −0.32; 95% CI: −0.61, −0.02; P = 0.04] for pain reduction. The patients' Oswestry Disability Index scoring was improved significantly by acupressure, compared with usual care (SMD: −0.55; 95% CI: −0.84, −0.25; P = 0.0003). The combination of acupressure with either manual acupuncture or electroacupuncture (EA) produced significant improvements over adjuvant therapies alone in RR (RR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.26; P < 0.00001), pain reduction, and Japanese Orthopaedic Association score.19

Mood disorder

Pregnancy conditions accompanied by mental-health problems and other problems can harm a mother and her child. In addition, other problems faced during the antenatal time—such as a stigma in society, a feeling of inadequacy, low self-efficacy, and negative perceptions—will influence mothers to come to health facilities.20 Mental-health problems, including prenatal stress, can affect infant health indirectly. This condition also affects development by increasing the risk of adverse birth outcomes, which are, in turn, associated with substantial developmental and health consequences.21

Pharmacotherapies, such as benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines, are associated with abuse and dependence, and have uncertain efficacy with long-term use. Some studies indicated that acupressure on HT-7 improved patients' sleep quality and increased their melatonin levels.

A study with acupuncture produced good results for treating mood disorders. In theory, the same effect should occur with acupressure, although no studies have been completed with the points used in acupuncture research. CV-12 needling in healthy subjects was mentioned in a study with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). There are mechanisms for modulating the limbic–prefrontal functional network that overlap with the functional circuits associated with emotional and cognitive regulation. Needle insertion in PC-6 has been shown to reduce heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) in healthy subjects (cited in a study by Lin et al. on acupressure), suggesting a sympathoinhibitory effect.22

A study of EA in GV-20 and SP-6 in chronically stressed rats increased the binding site of 5-HT1A receptors in the hippocampus of depressed rats and significantly increased the activities of 5-HT. This study also showed significant increases in serum levels of norepinephrine and dopamine. Furthermore, Lin et al. noted, in an acupressure study, that acupuncture at GV-20 and Ex-HN-3 combined with 5-HT reuptake inhibitors in older adults with depression significantly increased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels.23 Acupuncture points used included GV-20, GB-20, PC-6, HT-7, CV-12, and KI-1 at a frequency of 40–60 times per minute for 1–2 minutes.

The majority of studies used more than 3 acupoints, but the commonest acupoints used for treating depression are ST-36, SP-6, and HT-7, with 30–45 minutes per session and 2–40-week durations.23 However, SP-6 is secondary segmentation related to the uterus. Caution is necessary when using SP-6 in women at 36 weeks of gestation or less.

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is defined as a severe pregnancy-associated disease with the occurrence of hypertension and proteinuria at 20 weeks' gestation in a previously healthy pregnant woman and is associated with high maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality worldwide. High blood pressure (BP) in pregnant woman is one of the risk factors for preeclampsia.24 In a trial conducted by Lin et al., acupressure lowered SBP and diastolic BP in patients with hypertension.25 Acupressure was applied at LR-3, which is located on the dorsum of the foot in the distal hollow at the junction of the first and second metatarsal bone. The pressure was applied for 3 minutes.25

Another trial on acupressure for treating BP was conducted by Mardiyanti et al.26 This trial tested the effectiveness of Jin Shin Jyutsu (JSJ) massage and acupressure at LR-3 and LR-2 for reducing BP of pregnant mothers with preeclampsia. JSJ is a gentle noninvasive form of energy practice that utilizes 26 sets of key locations, called Safety Energy Locks, to promote the body's self-healing mechanism. The exact mechanism is not yet known.

A study by Millspaugh et al. in 2021 showed that JSJ was a viable option for reducing stress.27 Pressure at LR-2 and LR-3 stimulated the sensory nerve cells around the acupoints, which produced endorphin through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. This endorphin hormone induces a sense of calm and comfort that contributes to the change of BP.

A functional magnetic resonance imaging study in healthy adults showed that stimulating LR-3 and LR-2 with acupuncture produced deactivation of the limbic–paralimbic neocortical network, suggesting that acupressure on that acupoints might also work in the same way.28 Another trial found that acupressure at LR-3 and LR-2 combined with JSJ massage effectively reduced BP in pregnant mothers with preeclampsia.26

Acupressure For Labor Induction and Pain Management

Labor pain occurs from uterine contractions, cervical dilatation, and tension in the vaginal area and pelvic floor. Labor pain can cause stress and fear, and have a negative effect on the health of the mother, fetus, and newborn if the pain is left untreated. The stress and fear caused by excessive labor pain can cause peripheral vasoconstriction, reducing blood flow to the placenta, leading to negative fetal health. Even worse, labor pain can lead to a longer time to delivery with resultant health risk to the fetus.29

In addition, the fear and anxiety during birth may reduce a pregnant women's self-confidence, causing her to lose control, and also cause tension in the pelvic muscles. This tension causes resistance to the pushing forces applied by the uterus and the laboring woman. Thus, labor pain induces more pain, prolongs labor time is, and endangers the health of the fetus.29

Although evidence supports the efficacy of pharmacologic methods of treatment, potential adverse effects have also been identified. For example, parenteral opioids may lead to neonatal respiratory depression, hemoglobin desaturation, uterine hyperactivity, and an abnormal fetal HR. Inhalational analgesics can cause nausea, vomiting, mask phobia, and drowsiness. Systematic reviews have indicated that women receiving epidural analgesia were more likely to experience hypotension, motor blockade, intrapartum fever, and urinary retention.29

Evidence suggests that acupuncture and acupressure may be effective for managing pain in labor and birth, and may help to reduce rates of medical intervention, and the associated morbidity and mortality reported in reviews of maternity services. The evidence for acupuncture and acupressure has focused on assessing the efficacy of the interventions on pain relief and the supportive role of these interventions for women during labor. Acupressure for induction techniques may be practiced lightly starting at 37 weeks.29,According to Levett et al., antenatal education on—and the use of—complementary medicine techniques during labor, including acupressure, visualization, and relaxation, can manage pain effectively, increase personal control for women during labor, and reduce medical interventions including epidural use and cesarean section.30,31

The mechanism by which acupressure reduces labor pain may be related to reduction in adrenaline and noradrenaline release, and to vasodilation, which, in turn, results in oxytocin and endorphin release. In addition to the direct pain-relieving effects of endorphins and oxytocin, the improved contractions from increased oxytocin release can improve the efficacy of uterine contractions and shorten the duration of labor.

Points used are SP-6 and LI-4. It has been reported that SP-6 has a specific effect of increasing the strength of uterine contractions and shortening length of the first stage of labor, while LI-4 is a pain reliever.32 SP-6 plays a role in stimulating release of oxytocin from the pituitary gland, so its effect will be seen in the decreased requirement for synthetic oxytocin and length of labor. Natural oxytocin is known to have a relaxing effect, therefore pain scores are also affected, while LI-4 is known to have an effect on natural opioid release. The effect may be best reflected in pain scores (subjectively), or in reduction of epidural analgesia or other conventional analgesia (objectively).32

Acupressure for Postpartum Problems

Postpartum hemorrhage

According to American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, postpartum hemorrhage is defined as a loss of blood >1000 mL with signs and symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after delivery, regardless of the route of delivery. This event is the cause of one-fourth of maternal deaths worldwide. Definitive management of postpartum hemorrhage can become another obstacle if there are inadequate facilities and infrastructure, such as in a vast country with an uneven distribution of health access. In accordance with the target of SDGs 3, which emphasizes self-care, acupressure can be one of the nonpharmacologic prevention efforts for curbing postpartum hemorrhage.

López-Garrido et al., conducted an RCT of 76 puerperal women who had normal spontaneous births.33 These patients were divided into 2 groups: (1) verum acupuncture and (2) sham acupuncture. The researchers evaluated the influence of acupuncture on the third stage of labor. The acupoint used in this trial was CV-6, and manual acupuncture was used. Stimulation on CV-6 was effective for decreasing placental expulsion time and induced uterus contraction. Thus, the reduction in the length of the third stage of labor might reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage.33

Another RCT, conducted by Liu et al., recruited 276 purpuerants who were having difficult labor.34 The women were divided randomly into 2 groups: (1) medication + intravenous oxytocin and (2) medication + acupuncture. In the second group, acupuncture was given at bilateral LI-4, located in the middle of the second metacarpal bone on the radial side of the hand. The researchers concluded that stimulation at LI-4 was effective for promoting uterine contractions and shortening labor, avoiding complications. Acupuncture + medication was more effective and safe for both the mothers and their newborns.34

These several studies have reported acupuncture being effective for inducing uterine contractions. In theory, a similar effect can also be achieved by applying pressure to the same acupuncture points. Thus, acupressure may be a therapeutic option for preventing postpartum hemorrhage. Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of acupressure for inducing uterine contractions, as studies on acupuncture for this condition have not yet been conducted.

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is a vital part of providing every child with the healthiest start in life. This practice can benefit the infant and the mother. Breastfeeding is also the first baby vaccine and the best source of nutrition.35

A systematic review on the effects of acupressure, acupuncture, and massage techniques on symptoms of breast engorgement and breast milk volume by Hajian et al.36 included a study in Iran by Kamali Moradzade et al.37 that reported that there was a significant decrease in mean of breast hyperemia scores in an acupressure versus a hot/cold compress group. The mean difference between before and after the interventions showed significant differences in both groups (P < 0.001). The differences were shown in the patients' right breasts (5.94 ± 2.48 versus 8.53 ± 2.48, respectively) and left breasts (5.5 ± 2.3 versus 7.79 ± 3.95, respectively) in acupressure and compress groups.37

Acupressure also can increase the production of breast milk. Breast milk is considered to be the most important food for newborns and is highly recommended for them exclusively in the first 6 months of their lives. One of the reasons a mother stops breastfeeding her baby is inadequate breast milk. A study conducted by Sulymbona et al.,38 found that acupressure can increase breast milk production in postpartum mothers. The study included 70 postpartum mothers, 35 in an intervention group and 35 in a control group. The points used in this study were CV-17, ST-18 and SI-1. Acupressure on these acupoints stimulates beta-endorphin in the brain and spinal cord. Endorphins are useful for reducing pain, affecting memory and mood, which can then increase the prolactin hormone.38

Risks of Acupressure in Pregnancy

Although acupressure tends to be safe to do, there are still risks with this therapy. The most-common risk is soreness and bruising at the acupoints after therapy, whereas an uncommon—but serious—risk in patients with serious cardiac problems could be a drop in BP leading to undesirable effects. Acupressure should be avoided after meals, alcohol consumption, or after taking narcotics. One should not perform acupressure on skin that is inflamed, injured, or scarred, or that has a rash.39,40

Acupressure in pregnancy, especially at points such as LI-4 and SP-6, needs special attention due to inducing in premature induction of labor if performed too soon.20,23

CONCLUSIONS

Self-care is a reasonable approach for supporting SDG 3; and can be done by anyone, anywhere, and at any time. Acupressure is a potential self-care technique that has shown some promise for use during antenatal, labor, and postpartum times. Additional research on the use of acupressure during pregnancy and cross-sectional collaboration to increase awareness of acupressure techniques are needed.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No financial conflicts of interest exist.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was provided for this project.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wass V. The Astana declaration 2018. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(6):321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guégan JF, Suzán G, Kati-Coulibaly S, et al. Sustainable Development Goal #3, “health and well-being,” and the need for more integrative thinking. Veterinaria Mexico. 2018;5(2).1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston RB. Arsenic and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: Arsenic research and global sustainability In: Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Arsenic in the Environment, New York, September 25–27, 2015:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organisation. Reproductive Health Strategy: To Accelerate Progress Towards the Attainment of International Development Goals and Targets. Department of Reproductive Health and Research, WHO, Geneva. 2004; Online document at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68754/WHO_RHR_04.8.pdf;sequence=1 Accessed June 3, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organisation (WHO). Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division: Executive Summary. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Widgery D, Health statistics. Sci Culture. 1988;27(4):146–147. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO Guideline on Self-Care Interventions for Health and Well-Being. 2021. Online document at: www.apa.org/monitor/jan08/recommended. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- 8. Murphy SL, Harris RE, Keshavarzi NR, et al. Self-administered acupressure for chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Pain Med. 2019;20(12):2588–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen MC, Yang LY, Chen KM, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on using acupressure to promote the health of older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2020;39(10):1144–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adlan AS, Chooi KY, Mat Adenan NA. Acupressure as adjuvant treatment for the inpatient management of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(4):662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Melzack R, Wall PD, Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150(3699):971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mehta P, Dhapte V, Kadam S, et al. Contemporary acupressure therapy: Adroit cure for painless recovery of therapeutic ailments. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017;7(2):251–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mobarakabadi SS, Shahbazzadegan S, Ozgoli G. The effect of P6 acupressure on nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Adv Integr Med. 2020;7(2):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tara F, Bahrami-Taghanaki H, Amini Ghalandarabad M, et al. The effect of acupressure on the severity of nausea, vomiting, and retching in pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Med Res. 2020;27(4):252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Magfirah M, Fatma S, Idwar I. The effectiveness of acupressure therapy and aromatherapy of lemon on the ability of coping and emesis gravidarum in trimester I pregnant women at Langsa City Community Health Centre, Aceh, Indonesia. Maced J Med Sci. 2020;8(E):188–192. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan MWC, Wu XY, Wu JCY, et al. Safety of acupuncture: Overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep.2017;7(1):3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sehmbi H, D'Souza R, Bhatia A. Low back pain in pregnancy: Investigations, management, and role of neuraxial analgesia and anaesthesia. A systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017;82(5):417–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manyozo SD, Nesto T, Bonongwe P, et al. Low back pain during pregnancy: Prevalence, risk factors and association with daily activities among pregnant women in urban Blantyre, Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2019;31(1):71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li T, Li X, Huang F, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of acupressure on low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid-Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:8862399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bayrampour H, Hapsari AP, Pavlovic J. Barriers to addressing perinatal mental health issues in midwifery settings. Midwifery. 2018;59:47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coussons-Read ME. Effects of prenatal stress on pregnancy and human development: Mechanisms and pathways. Obstet Med. 2013;6(2):52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yeung WF, Ho FYY, Chung KF, et al. Self-administered acupressure for insomnia disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2018;27(2):220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin J, Chen T, He J, et al. Impacts of acupressure treatment on depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):169–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giannakou K, Evangelou E, Papatheodorou SI. Genetic and non-genetic risk factors for pre-eclampsia: Umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(6):720–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin G-H, Chang W-C, Chen K-J, et al. Effectiveness of acupressure on the Taichong acupoint in lowering blood pressure in patients with hypertension: A randomized clinical trial. Evid-Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1549658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mardiyanti I, Anggasari Y.. Effectiveness of JSJ (Jin Shin Jyutsu) massage and acupressure at points of LR 3 (Taichong) and LR 2 (Xingjiang) in reducing blood pressure of pregnant mothers with preeclampsia. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium of Public Health-ISOPH. Surabaya, Indonesia, November 11–12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Millspaugh J, Errico C, Mortimer S, et al. Jin Shin Jyutsu® self-help reduces nurse stress: A randomized controlled study. J Holist Nurs. 2021;39(1):4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee MY, Lee BH, Kim HY, et al. Bidirectional role of acupuncture in the treatment of drug addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;126:382–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Türkmen H, Çeber Turfan E. The effect of acupressure on labor pain and the duration of labor when applied to the SP6 point: Randomized clinical trial. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020;17(1):e12256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levett KM, Smith CA, Bensoussan A, et al. Complementary therapies for labour and birth study: A randomised controlled trial of antenatal integrative medicine for pain management in labour. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e010691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levett KM, Smith CA, Dahlen HG, et al. Acupuncture and acupressure for pain management in labour and birth: A critical narrative review of current systematic review evidence. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(3):523–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen Y, Xiang X-Y, Chin KHR. Acupressure for labor pain management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2021;39(4):243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. López-Garrido B, García-Gonzalo J, Patrón-Rodriguez C, et al. Influence of acupuncture on the third stage of labor: A randomized controlled trial. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2015;60(2):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu J, Han Y, Zhang N, et al. The safety of electroacupuncture at Hegu (LI 4) plus oxytocin for hastening uterine contraction of puerperants—a randomized controlled clinical observation. J Tradit Chin. Med. 2008;28(3):163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organisation. Global Breastfeeding Collective—Executive Summary Nurturing the Health and Wealth of Nations: The investment Case for Breastfeeding. November 2, 2017. Online document at: www.who.int/publications/m/item/nurturing-the-health-and-wealth-of-nations-the-investment-case-for-breastfeeding Accessed June 3, 2023.

- 36. Hajian H, Soltani M, Seyd Mohammadkhani M, et al. Breast engorgement and increased breast milk volume in lactating mothers: A review. Int J Pediatr. 2021;9(2):12939–12950. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kamali Moradzade M, Ahmadi M, Heshmat R, et al. Comparing the effect of acupressure and intermittent compress [sic] on the severity of breast hyperemia in lactating women. Q Horizon Med Sci. 2013;18(4):155–160. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sulymbona N, As'ad S, Khuzaimah A, et al. The effect of acupressure therapy on the improvement of breast milk production in postpartum mothers. Enferm Clin. 2020;30:(suppl2):615–618. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cunningham M. Acupressure Fundamentals: A 20 Point Self Healing Program. Flagstaff: AZ: Acu-Ki® Institute; 2012. Online document at: https://stress-away.com/Acuprressurefundamentals.pdf.pdf Accessed June 3, 2023.

- 40. Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(3):194–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]