Abstract

Emerging non-Western studies indicate new patterns in the functionality of nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) warranting further investigation in different cultures. The current study aims to investigate the function (etiology and underlying mechanism) of NSSI among a sample of university students in Tehran, Iran, using the Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS). The ISAS was administered to 63 students who self-injured (52.4% female; M age = 22.15). An exploratory factor analysis using the Bayesian estimation method was conducted. A three-factor model of NSSI functions emerged including an intrapersonal factor representing within-self functions (e.g., self-punishment); a social identification factor consisting of functions establishing a sense of self/identity (e.g., peer bonding); and a communication factor representing an influencing/communicating functionality (e.g., marking distress). Intrapersonal and social identification factors were associated with greater severity of NSSI method and increased anxiety. Findings support the use of the ISAS among an Iranian sample and revealed additional patterns beyond the commonly referenced two-factor model (intrapersonal and interpersonal functions) in a culturally novel sample. The results are situated within the sample’s sociocultural context.

Keywords: Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), function, inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS), university students, Iran

Introduction

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to deliberate damage to one’s own body tissue without conscious suicidal intent and for reasons that are not socially sanctioned (Nock & Favazza, 2009), and has been identified in the DSM-5, Section III as a disorder requiring further research (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Methods of NSSI have been categorized into clinically minor forms (e.g., self-hitting, biting, and inserting object under nail or skin) and moderate/severe forms (e.g., cutting, burning, scratching, erasing, carving into skin; Singhal et al., 2021). The most common methods of NSSI are cutting, scratching, burning, self-hitting, head-banging, and biting. These are common among community populations with a prevalence of 8%–26% of adolescents and 4.5%–22% of young adults who report lifetime NSSI engagement (Swannell et al., 2014). While NSSI is documented to be more commonly reported among female adolescents and young adults in Western samples, these gender differences have not been consistently found in studies, especially those focusing on non-Western samples (Gholamrezaei et al., 2016).

Although NSSI is recognized in the DSM-5 as a separate diagnosis (DSM-5, 2013), it also has been associated with a number of mental health difficulties such as depression and anxiety (e.g., Gholamrezaei et al., 2016). Additionally, while by definition NSSI is the act of self-injury without suicidal intent (Nock & Favazza, 2009), studies have found that there is an association between suicidality and NSSI engagement whereby NSSI engagement is associated with a seven-fold increase in suicide attempts. Evidence also shows that the presence of certain mental health disorders (e.g., depression) in combination with NSSI engagement is associated with a higher likelihood of suicidalideation than either of these risk factors independently (Kiekens et al., 2018). Furthermore, evidence shows that individuals who engage in multiple methods of NSSI (e.g., cutting, burning, scratching) are more likely to attempt suicide (Ammerman et al., 2018).

Though the prevalence of NSSI is alarming and there seem to be factors such as gender and ethnicity impacting its use (Gholamrezaei et al., 2016), the functions or reasons why individuals engage in the behaviour have mostly been examined in Western contexts where the functions of NSSI have been found to be primarily focused on intrapersonal emotion regulatory functions (e.g., Klonsky et al., 2015). Historically, Nock and Prinstein’s (2004) four-factor function model (FFM) has been one of the most widely supported models of NSSI function, albeit almost exclusively within Western contexts. In this model, functions of NSSI vary along two dimensions of reinforcements: intrapersonal versus interpersonal and negative (i.e., following the removal of an aversive stimulus) versus positive (i.e., following the presentation of a favorable stimulus; Nock & Prinstein, 2004).

Furthermore, research examining the functions of NSSI has primarily used two different instruments; the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (FASM; Lloyd et al., 1997) and the Inventory of Statements About Self-injury (ISAS; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009). Several studies conducting a confirmatory factor analysis using the FASM supported the use of the FFM (e.g., Izadi-Mazidi et al., 2019), while other studies did not support the full FFM or found different functionalities. For instance, Dahlström et al. (2015) differentiated between intrapersonal and interpersonal functions but did not support the positive/negative dimension in the intrapersonal functions of NSSI. Instead, they suggested a four-function model of NSSI which include: social influence, automatic functions, peer identification (i.e., positive interpersonal), and avoiding demands (i.e., negative interpersonal). Similarly, in a study conducted with adolescents in Hong Kong, You et al. (2013) found a three-factor model including affect regulation, social influence, and social avoidance; with negative and positive intrapersonal functions collapsing into one factor of affect regulation. In fact, the FASM has been challenged regarding detecting the intrapersonal negative factor as there are only two items tapping into this function (Klonsky et al., 2015).

Other researchers have used the Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS) to determine the functionality of NSSI. Developed by Klonsky and Glenn (2009), the ISAS assesses 13 different functions of NSSI in two dimensions of intrapersonal and interpersonal. The intrapersonal dimension includes affect regulation, anti-dissociation, anti-suicide, marking distress, and self-punishment functions; the interpersonal dimension includes autonomy, interpersonal boundaries, interpersonal influence, peer bonding, revenge, self-care, sensation-seeking, and toughness. Pérez et al. (2020) examined the factorial model of the ISAS in a Spanish adult sample whereby results supported the two-factor model, but found that the self-care factor loaded onto the intrapersonal factor rather than the interpersonal factor. Similarly, in a sample of Norwegian university students, Vigfusdottir et al.’s (2020) results supported the two-factor model, but the self-care factor loaded onto the intrapersonal factor and the marking distress factor loaded onto the interpersonal factor (rather than intrapersonal as per Klonsky & Glenn, 2009). Thus, though the two–factor model has been validated in a number of samples, there are still nuances and differences that need to be further explicated, particularly in non-Western populations.

In an attempt to clarify the inconsistencies in the functions of NSSI demonstrated by the FASM and the ISAS, Klonsky et al. (2015) examined the factor structure of NSSI functions in a large clinical sample using both the ISAS and FASM. They concluded that a two-factor framework of intrapersonal and interpersonal domains had clinically significant implications for each set of functions, and that it should inform the conceptualization, assessment, and treatment of self-injury. Specifically, research among Western samples has revealed that people who self-injure for intrapersonal reasons, for example to regulate emotions or self-punish, might need more intensive care as intrapersonal function is associated with hopelessness, depressive symptoms, and posttraumatic stress symptoms (e.g., Klonsky et al., 2015; Singhal et al., 2021). Thus, establishing the functionality of NSSI may suggest different clinical presentations, and therefore, interventions.

Although studies have demonstrated commonalities among the functional models from various Western samples, studies in non-Western countries suggest important divergence (e.g., Gholamrezaei et al., 2016). For instance, You et al. (2013) argue that cultural values such as collectivism can explain the high need to be part of a group, which may in turn contribute to a need to self-injure to establish a sense of belonging. They found that using NSSI “to feel more a part of a group” was the most endorsed item while “to punish oneself” had low endorsement. This finding suggests that in collectivistic societies, the interpersonal functionality of NSSI might have a greater importance. Furthermore, it has been suggested that cultural differences in samples may play an important role in the inconsistencies in results (Gholamrezaei et al., 2016).

The emergence of different patterns in the functionality of NSSI in non-Western samples warrants further investigation in different cultural contexts. Thus, the present study aimed to assess functions of NSSI among a sample of university students with a history of lifetime NSSI in Tehran, Iran. To date, there have been very few studies on the functions of NSSI in Iran despite a rather high prevalence among its youth (Gholamrezaei et al., 2017). In a sample of 3966 adolescents in Iran, Nemati et al. (2020) found a significant relationship between family psychosocial function (e.g., communication, interactions, positive emotional relationship) and NSSI experience, whereby poor psychosocial functioning of the family was associated with an increased likelihood of NSSI engagement. Additionally, a study conducted by Rezaei et al. (2021) assessing the factor structure of the ISAS in an adolescent population in Iran found support for the two-factor model of the ISAS (intrapersonal and interpersonal factors). Similarly, Izadi-Mazidi et al. (2019) assessing the factor analysis of the FASM among Iranian adolescents engaging in NSSI supported the structural validity of the FASM and the two dimensions of reinforcement presented in the FFM. However, contrary to other non-Western studies (e.g., You et al., 2013), Izadi-Mazidi et al. (2019) found that interpersonal functions were not as prevalent as intrapersonal functions, highlighting the importance of examining NSSI functions in Iran, given potential divergence of results. To date functions of NSSI have only been examined in adolescent samples and given the important developmental changes associated with the period of emerging adulthood, there is a need to examine NSSI functions in young adult samples.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to provide a culturally nuanced understanding of the functionality of NSSI in a sample of university students in Iran.

Hypotheses

Based on the existing literature in the West and the limited research in non-Western contexts, it was hypothesized that a two-factor model of intrapersonal and interpersonal functions would best represent functions of NSSI among an Iranian sample. Given previous literature demonstrating associations with NSSI and mental health difficulties as well as suicidality, the second objective was to examine the relationship between NSSI functions with severity of NSSI behavior as well as psychological symptoms of suicidality, depressive symptoms, and anxiety. Due to inconsistency regarding the importance of interpersonal functions of NSSI in collectivistic cultures (e.g., Izadi-Mazidi et al., 2019; Rezaei et al., 2021; You et al., 2013), no specific hypothesis was proposed with regards to this objective. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study, investigating functions of NSSI among university students in Iran.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample of the present study consisted of 63 students (52.4% female; M age = 22.15, SD = 2.75) with a history of lifetime NSSI who were enrolled in a large public university in Tehran. This sample was derived from a larger sample of 554 university students (57.2% female) that were part of a general study of stress and coping in university students. Participants for the larger sample were recruited in classrooms across departments and faculties. Participation was voluntary and study packages were anonymized to protect the confidentiality of students (see Gholamrezaei et al., 2017). The present study’s sample consists of a subset of students who endorsed the screening question of “have you ever self-injured (e.g., cutting, head banging) without any suicidal intent, which led to bleeding, bruising, or any mark” and agreed to participate in the follow up study on NSSI. The screening question was preceded by a clear definition of NSSI (i.e., Self-injury is defined as behaviors that lead to body tissue damage without wanting to die. Behaviors such as cutting or head banging that result in bleeding, bruising, or any mark without any suicidal intent). All materials and procedures were approved by the ethics board of the university, and an information sheet indicating available on-campus and community mental health resources was provided to all the contacted students.

Measures

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Scale

This scale was developed in Farsi to measure prevalence and characteristics of NSSI and was a close adaptation of the How I Deal with Stress measure (HIDS; Heath & Ross, 2007) and Section I of the Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009). Questions regarding methods of NSSI, emotions felt after NSSI engagement, age of onset, and NSSI frequency, were adapted from the HIDS. Some other characteristics including presence of pain, desire to stop NSSI, and NSSI engagement in presence of others were adapted from the ISAS, Section I. After adaptation, the questionnaire was translated to Farsi and back translated to English followed by a clinical review to ensure the linguistic and face validity. Students who reported engaging in one or multiple methods of self-hitting, punching, biting, and/or banging were categorized in the low severe NSSI method subgroup and students who indicated engagement in cutting, scratching, and/or burning categorized into moderate/severe NSSI method subgroup. This definition of NSSI severity is based on potential tissue damage and has been previously used in the NSSI literature (e.g., Singhal et al., 2021).

Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS-Section II; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009)

The second section of ISAS consists of 39 items rated on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = not relevant to 2 = very relevant), assessing 13 functions of NSSI which fall into two categories of intrapersonal and interpersonal functions. The intrapersonal function category consists of affect regulation, anti-dissociation, anti-suicide, marking distress, and self-punishment; the interpersonal function category consists of autonomy, interpersonal boundaries, interpersonal influence, peer bonding, revenge, self-care, sensation seeking, and toughness.

Previous studies support structural and construct validity of the ISAS functions (e.g., Vigfusdottir et al., 2020). Klonsky and Glenn (2009) found internal consistencies of .88 and .80 for the interpersonal and intrapersonal subscales, respectively. For this study, the instrument was translated and back translated to Farsi and was examined by three clinical psychologists and an expert in Farsi language to evaluate its validity. Two items from the interpersonal subscale (item 2: “creating a boundary between myself and others” and item 33: “pushing my limits in a manner akin to skydiving or other extreme activities”) and one item from the intrapersonal subscale (item 32: “putting a stop to suicidal thoughts”) were asked to be removed from the questionnaire for approval by the ethics and research departmental committees of the university. The reasons given for removing these items were (1) the item was not culturally appropriate and (2) there was potential harm related to the item.

The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001)

This instrument consists of four items with different response scales. The first item assesses lifetime suicide ideation/plan/attempts (“have you ever thought about or attempted to kill yourself?“) and is followed by a six-choice categorical response of “Never” to “I have attempted to kill myself and hoped to really die”. The second item evaluates the frequency of 12-month suicidal ideation (“how often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year?“) and is followed by a five-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = very often). The third item evaluates the threat of suicide attempt (“have you ever told someone that you were going to commit suicide, or that you might do it?“) followed by a five-choice categorical response of “No” to “Yes, more than once, and really wanted to do it”. Finally, the fourth item assesses likelihood of future suicidal behaviours (“how likely is it that you will attempt suicide someday?“) and is followed by a seven-point Likert scale (0 = never to 6 = very likely). Osman et al. (2001) suggest that this scoring system provides a robust measurement of a general suicide risk. The SBQ-R has demonstrated strong construct validity and internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .82 in a young Iranian sample (Amini-Tehrani et al., 2020). In the present study, internal consistency was strong (Cronbach’s α = .85).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

This instrument consists of 21 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (0 = did not apply to me at all to 3 = applied to me very much or most of the time), and is composed of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress subscales. It aims to evaluate negative affectivity over the previous week. The Farsi version of the DASS-21 is widely used and has shown strong internal consistency (anxiety, α = .88; depression, α = .92; and stress, α = .82), and high four-week test-retest reliability (r = .72). In the present study, internal consistency was strong (Cronbach’s α = .93).

Data Analysis

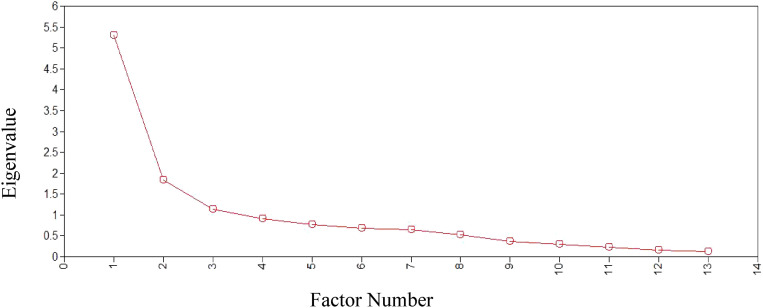

An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on the 13-function levels of ISAS using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). No restrictions were imposed on the parameters of the model, given the limited prior research. The EFA was conducted using the Bayesian estimation method and GEOMIN rotation, recommended when Bayesian estimation is used, with a minimal factor loading of .40. Bayesian factor analysis does not rely on a multivariate normal distribution and large-sample theory; and it performs better with small sample sizes (Heerwegh, 2014). Moreover, compared to Maximum Likelihood, the Bayesian analysis also allows the estimation of models that are more complex. In the present study, models with one to four factors were investigated, and the optimal model was selected based on (a) interpretability, (b) the size of eigenvalues, (c) scree plot (see Figure 1) and (d) the lowest number of factors resulting in a non-significant Posterior Predictive p value (PPP) usinchi-square. In Mplus, a PPP value close to .5 suggests an excellent model fit; however, there is no established PPP value for whether a fit is acceptable.

Figure 1.

Scree plot for the exploratory factor analysis of the 13 ISAS functions.

Post hoc analyses, including t-tests and Pearson correlations, were conducted to examine the relationship between the mean scores of the emergent factors and NSSI severity, other NSSI characteristics, suicidality, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Mean scores of the emergent factors were computed by Mplus using 20 imputations from the Bayesian posterior distribution (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). The descriptive properties of the demographic and clinical variables, post-hoc analyses, as well as internal consistencies (using coefficient alpha) were conducted using SPSS.

Sample Size Justification

Bayesian statistics were used as they are beneficial in clinical studies that rely on smaller sample sizes (Heerwegh, 2014), with a minimum recommend sample size of 50 (although based on certain considerations EFAs can yield good quality results for samples below 50; de Winter et al., 2009). EFA parameters which should be accounted for when determining the sample size include the number of factors of the estimated solution and the number of variables. Specifically, it is recommended to have a low factor number and high number of variables which does not exceed the sample size (de Winter et al., 2009; Kyriazos, 2018). The current study fulfills both these requirements, thus strengthening support for using a smaller sample size. Additionally, small sample sizes of 50 and below were demonstrated in other studies using exploratory factor analysis (e.g., Merica et al., 2023; Tantrarungroj et al., 2022). Therefore, since the sample size for the current study exceeds the minimum requirement of 50, despite its limitations, it is considered acceptable.

Results

Primary Analysis

The mean age of onset of NSSI engagement was 13.7 (SD = 5.15) with a mode of 15. Regarding NSSI methods used, 57% of the participants (n = 36) indicated engaging in severe methods of NSSI and 43% (n = 27) indicated engaging in only minor forms of NSSI. Almost 70% of the participants indicated engaging in multiple methods of NSSI, endorsing punching against a wall the most, followed by self-hitting and cutting.

The mean total score for ISAS, Section II, was 6.68 (SD = 4.25) which was substantially lower compared to the mean reported by Klonsky and Glenn (2009) (ISAS total mean = 14.3, SD = 13.3). The mean score of intrapersonal functions was .68 (SD = .37) and the mean of interpersonal functions was .42 (SD = .34) with no gender differences. Both means were lower compared to those reported in the Klonsky and Glenn’s (2009) study (M = 1.7, SD = 1.4 and M = .7, SD = 1.0; respectively). The most frequently endorsed items were “calming myself” followed by “reducing anxiety, frustration, anger, or other overwhelming emotions”, “punishing myself”, and “signifying the emotional distress I’m experiencing”. The least frequently endorsed items were “fitting in with others” followed by “bonding with peers”, “entertaining myself or others by doing something extreme”, and “making sure I am still alive when I don’t feel real”. Consistent with Klonsky and Glenn (2009), the most endorsed functions were affect regulation (M = .96, SD = .54) and self-punishment (M = .74, SD = .6) and the least endorsed function was peer bonding (M = .21, SD = .34). Table 1 provides information about correlations among the 13 functions of NSSI.

Table 1.

Correlations Among 13 ISAS Functions.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Affect regulation | - | ||||||||||||

| 2.Interpersonal boundaries | .15 | - | |||||||||||

| 3.Self-punishment | .13 | .24 | - | ||||||||||

| 4.Self-care | .27* | .47** | .42** | - | |||||||||

| 5.Anti-dissociation | .15 | .61** | .39** | .71** | - | ||||||||

| 6.Anti-suicide | .12 | .19 | .25 | .50** | .42** | - | |||||||

| 7.Sensation seeking | .18 | .38 | .21 | .40** | .30* | .22 | - | ||||||

| 8.Peer bonding | −.07 | .51** | .17 | .54** | .48** | .28* | .41** | - | |||||

| 9.Interpersonal influence | .18 | .19 | .18 | .25* | .08 | .02 | .27* | .38** | - | ||||

| 10.Toughness | .17 | .64** | .23 | .56** | .59** | .45** | .51** | .62** | .16 | - | |||

| 11.Marking distress | .35* | .44** | .32* | .40** | .24 | .27** | .42** | .33** | .55** | .50** | - | ||

| 12.Revenge | .20 | .25* | .22 | .30** | .14 | .01 | .55** | .39** | .76** | .20 | .54** | - | |

| 13.Autonomy | .16 | .50** | .25* | .47** | .44** | .38** | .37** | .52** | .30* | .70** | .37** | .32* | - |

Note.Pearson Correlation, N = 63.

*p < .05, **<.01.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

The optimal solution included a three-factor model with a nonsignificant Posterior Predictive p value (p = .2; 95% CI: −20.71–57.12) and eigenvalues of 5.3, 1.83, and 1.14; with all remaining eigenvalues less than 1.00. All the ISAS functions, except Affect Regulation, significantly loaded onto the three factors with a factor loading above .4 (see Table 2). Affect Regulation was excluded from the factor model as the item did not significantly load onto any of the factors and thus was not retained. The first factor was named intrapersonal and included within-self functions concerning regulating inner experiences. The second function was referred to as social identification including NSSI functions about situating self/identity within social contexts. The third factor was named communication and consisted of NSSI functions to influence or communicate to someone else. Further, as illustrated in the table, marking distress significantly loaded on to both social identification (.40) and communication (.46). The GEOMIN factor correlation between intrapersonal and social identification factors was .59 (p < .05), between intrapersonal and communication factors was .17, and between social identification and communication factors was .29. Internal consistencies calculated by Cronbach alpha were .74 for intrapersonal factor, .83 for social identification factor, and .82 for communication factor. There were no gender differences across the emergent factor mean scores.

Table 2.

GEOMIN Rotated Factor Loadings of 13 ISAS Functions.

| ISAS functions | M (SD) | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Social Identification | Communication | ||

| Affect regulation | .97 (.54) | .09 | .04 | .07 |

| Self-punishment | .71 (.60) | .44* | −.03 | .13 |

| Self-care | .51 (.52) | .84* | .00 | .09 |

| Anti-dissociation | .49 (.59) | .76* | .12 | −.03 |

| Anti-suicide | .53 (.63) | .43* | .23 | −.14 |

| Interpersonal boundaries | .39 (.50) | .22 | .54* | .01 |

| Sensation seeking | .38 (.53) | .00 | .46* | .39 |

| Peer bonding | .21 (.34) | .20 | .48* | .20 |

| Toughness | .45 (.49) | .01 | .97* | −.03 |

| Autonomy | .40 (.49) | .03 | .68* | .06 |

| Interpersonal influence | .51 (.52) | .00 | .00 | .82* |

| Marking distress | .64 (.59) | .00 | .40* | .46* |

| Revenge | .50 (.54) | .01 | .00 | .94* |

*p < .05.

Post Hoc Analyses

Post hoc t test analyses revealed that students engaging in moderate/severe forms of NSSI had significantly higher scores in intrapersonal and social identification factors compared to participants who engaged in minor forms of NSSI [t (57) = 2.12, p < .05 and t (57) = 2.4, p < .05; respectively]. We also examined the relations between feeling calm, happy, guilty, and shame after NSSI engagement and factor mean scores. Students who reported feeling calm after NSSI engagement had higher scores in the intrapersonal factor [t (59) = 2.04, p < .05]; and students who reported feeling happy after NSSI engagement had higher scores in the communication factor [t (57) = 2.03, p < .05]. No difference was found regarding feelings of guilt and shame, or other characteristics of NSSI including feeling pain and self-injuring when alone.

As shown in Table 3, intrapersonal and social identification factors exhibited a significant correlation with anxiety. Depressive symptoms correlated significantly with all factors; whereas, no significant correlation was found between the emergent factors and suicide risk. A negative and significant correlation was found between social identification and NSSI onset.

Table 3.

Relations of Emergent Factors with NSSI Characteristics, Suicidality, Depressive, and Anxiety Symptoms.

| Intrapersonal | Social Identification | Communication | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime NSSI frequency | .24 | .15 | .10 |

| NSSI onset | −.09 | −.30* | −.21 |

| Depression | .30* | .33** | .28* |

| Anxiety | .44** | .36** | .20 |

| Suicide risk | .01 | .04 | −.01 |

Note. Pearson Correlation.

*p < .05, **<.01.

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the underlying factor structure of NSSI functions among a sample of Iranian university students who self-injured using the ISAS. Our analyses support a three-factor model comprising of intrapersonal, social identification, and communication functions. Contrary to our hypothesis, findings revealed a three-function model. This is one of the first studies suggesting a three-function model using the ISAS.

In our three-factor model, intrapersonal function (factor 1) consisted of the four ISAS functions of self-punishment, anti-dissociation, anti-suicide, and self-care. This factor aligns with the intrapersonal function indicated in previous studies (Klonsky et al., 2015; Nock & Prinstein, 2004; Pérez et al., 2020). However, there are several differences with respect to previous research. First, consistent with previous studies (e.g., Pérez et al., 2020; Vigfusdottir et al., 2020), our results provided evidence that self-care fits better as an intrapersonal factor rather than a social function. Self-care, as a function of NSSI, was defined as “self-injuring to create a physical wound that one can care for more easily than one’s emotional distress” (Klonsky & Glenn, 2009). Although Klonsky and Glenn (2009) originally theorized self-care as a self-focused function, self-care loaded slightly higher on the social function in their analysis. Second point of divergence is the lack of loading of affect regulation on any of the factors. Consistent with previous research (You et al., 2013), affect regulation had the highest mean with 92% of the sample endorsing affect regulation as a function of NSSI. Despite the high level of endorsement, affect regulation did not correlate with other ISAS functions except for a small correlation with self-care and marking distress. We speculate that the lack of factor loading of affect regulation could be an indicator of a separate factor structure; alone it was too distinct to load on any of the factors but was not strong enough to be a separate factor. Future research is needed to clarify this finding.

The present analyses revealed two other factors—social identification (factor 2) and communication (factor 3) which were not correlated, suggesting two distinct constructs. The social identification factor consisted of five functions of interpersonal boundaries, peer bonding, sensation seeking, toughness, and autonomy. In fact, the social identification factor primarily represents that an individual would engages in NSSI to establish a sense of “self” in relation to “others” including self-injuring to set psychological barriers between self and others, to connect to peers, or to demonstrate toughness or autonomy. Evidence from qualitative studies on adolescents’ self-harm suggest an identification functionality of NSSI in which the individual self-injures to redefine their identity in social contexts (e.g., Stänicke et al., 2018). Although the social identification functionality of NSSI has not been previously identified in the context of the ISAS, the close relations between self-injury and identity has been a consistent discourse in the literature (e.g., Breton, 2018). Additionally, it is important to situate this result within the sociocultural context of the study sample. Youth in Iran hold both collectivistic family-oriented values as well as individualistic ambitions. Given the globalization of communication such as the media, Iranian society has undergone decades of identity crisis attempting to adhere to both Western and traditional values at the same time (Alishahi et al., 2019), this is particularly true for university students in large urban centers. Previous studies (i.e., Izadi-Mazidi et al., 2019; Rezaei et al., 2021) which found 2-factor models consistent with the interpersonal/intrapersonal were limited to the adolescent developmental period. However, identity formation may be particularly relevant in the emerging adulthood period. In this way, emerging adults in universities in Iran experience unique challenges in forming their identities as they begin to navigate through the discrepancy between the traditional family values and individualistic aspirations. Thus, the social identification factor may reflect the significance of the challenge of identity formation among emerging adults in Iran, manifesting through self-injury (Alishahi et al., 2019; Stänicke et al., 2018).

Our third factor, communication, consisted of interpersonal influence, marking distress, and revenge. This factor indicates a functionality of communicating emotional pain through NSSI by influencing someone, taking revenge, and/or communicating to others the emotional pain through physical marks. Although marking distress is suggested as an intrapersonal function (Klonsky & Glenn, 2009), a communication aspect could easily be conceptualized from this function as it contains a desire to signal inner distress or an attempt to create an external picture of an internal world (Straker, 2006). Furthermore, marking distress significantly loaded on to both social identification (.40) and communication (.46) as it has in similar studies examining the psychometric properties of the measure in different populations (Vigfusdottir et al., 2020). The communication factor had a higher loading than the social identification which held only the minimum required factor loading (.40). It was attributed to the communication factor as it has a higher factor loading and it has been conceptualized as being a way to communicate to other’s one’s pain. (Straker, 2006). We can also situate the communication functionality within the sociocultural context with reference to the broader self-harming behaviours in Iran. For instance, self-immolation is a method of suicide in some parts of Iran. Self-immolation is usually chosen due to its communication functionality including sending a threat, taking revenge, voicing the suffering, and/or expressing a deep protest to familial or socio-political circumstances (Mansourian et al., 2019). Considering the close relationship between suicidal behaviours and NSSI (e.g., Klonsky et al., 2015), emergence of a communication functionality of NSSI within our sample appears to be culturally relevant.

Surprisingly, we only found a significant correlation between intrapersonal and social identification factors. Additionally, intrapersonal and social identification factors were associated with greater severity in NSSI, and higher symptoms of anxiety compared to the communication factor. Some theories, such as attachment and relational theories, suggest that these emergent factors demonstrate a close intersectionality among “affect”, “self”, and “others” (Straker, 2006). Exploring theories outside of the learning theories of NSSI, there is a focus on the role of body, or more specifically skin, in the functionality of NSSI. Within current societies, skin has an important influence on shaping different aspects of identity. Skin is a boundary between inside and outside, self and others, which makes it an important site for forming a sense of self/identity and communicating to others when words fail (Breton, 2018). Therefore, results suggest that self-injuring the body not only has intrapersonal functionality, but also serves in constructing a sense of self in relation to others and a way influencing the outside world.

In sum, our results highlight the importance of identity development and communication functionality of NSSI, as well as regulation of internal experiences in an Iranian sample. Findings support the existing evidence indicating that the ISAS is a useful instrument in investigating the factor structure of NSSI functions and reveal patterns that have cultural relevance However, these findings should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. First, this study is based on self-report questionnaires, developed in the West, without qualitative or clinical confirmation. In fact, compared to previous research (Klonsky & Glenn, 2009), our participants endorsed fewer functions on the ISAS suggesting that other functions not listed might be at play. Therefore, further research could use multiple methods to provide a more nuanced understanding of NSSI functions. Second, the cross-sectional design does not allow for causal inferences. Third, as mentioned in the method section, three items from the inventory were omitted. The significance of the omission impact on the results remain unclear. Further studies can clarify this issue. Finally, we were unable to run an item-level analysis on the ISAS factor structure due to limited sample size.

Despite these limitations, our results indicate that the ISAS could be a useful instrument within Iranian young adult samples in assessing the functionality of NSSI in both research and clinical contexts. This study also revealed a new pathway in factor structure of the ISAS in an Iranian young adult sample and contributed to the NSSI research literature by contextualizing the functionality of NSSI based on a non-Western sample. Being the first study investigating functions of NSSI among Iranian university students, our findings also provided important new information on how NSSI can manifest among this population.

Author Biographies

Maryam Gholamrezaei, Ph.D. Dr. Gholamrezaei holds a PhD. in Counselling Psychology from McGill University and is a registered clinical and counselling psychologist working with adults and couples. She has published multiple manuscripts in the area of self-injury and cross-cultural differences of university students’ experiences.

Nancy Heath, Ph.D. Dr. Heath is a Distinguished James McGill Professor at McGill University. She has been an international leader in non-suicidal self-injury for more than 20 years.

Guillaume Elgbeili, MSc. Mr. Elgbeili is a statistician working at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute since 2013. He has worked in diverse areas such as prenatal and maternal stress as well as self-injury in university students.

Liane Pereira, Ph.D. Dr. Pereira is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Central Washington University. Her research interests are in the area of youth mental health, school-based mental health, child and adolescent development, inequities in health and education.

Leili Panagh, Ph.D. Dr. Panagh is an Associate Professor in Family Research Institute at Shahid Beheshti University whose work focuses on enhancing young adults' mental health and well-being.

Laurianne Bastien, M.A. Ms. Bastien is a PhD candidate at McGill University’s Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology whose research area focuses on the development of educational programs to enhance students’ mental health resilience.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is supported by This research was realized with the support of the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Société et culture (FRQSC), (514) 873-1298.

Ethical Considerations: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Shahid Beheshti University, McGill University’s Research Ethics Board, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual adult participants included in the study.

ORCID iD

Laurianne Bastien https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4379-6024

References

- Alishahi A., Refiei M., Souchelmaei H. S. (2019). The prospect of identity crisis in the age of globalization. Global Media Journal, 17(32), 1–4. Retrieved from. https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/scholarly-journals/prospect-identity-crisis-age-globalization/docview/2250567181/se-2?accountid=12339 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Amini-Tehrani M., Nasiri M., Jalali T., Sadeghi R., Ghotbi A., Zamanian H. (2020). Validation and psychometric properties of suicide behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R) in Iran. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 101856. 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman B. A., Jacobucci R., Kleiman E. M., Uyeji L. L., McCloskey M. S. (2018). The relationship between nonsuicidal self‐injury age of onset and severity of self‐harm. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(1), 31–37. 10.1111/sltb.12330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton D. (2018). Understanding Skin-cutting in adolescence: Sacrificing a part to save the whole. Body and Society, 24(2), 1357034X1876017. https://doi.org/10.11771357034X18760175 [Google Scholar]

- Dahlström Ö., Zetterqvist M., Lundh L. G., Svedin C. G. (2015). Functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses in a large community sample of adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 302–313. 10.1037/pas0000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Winter J. C. F., Dodou D., Wieringa P. A. (2009). Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44(2), 147–181. 10.1080/00273170902794206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholamrezaei M., De Stefano J., Heath N. L. (2017). Nonsuicidal self‐injury across cultures and ethnic and racial minorities: A review. International Journal of Psychology, 52(4), 316–326. 10.1002/ijop.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholamrezaei M., Heath N., Panaghi L. (2016). Non-suicidal self-injury in a sample of university students in tehran, Iran: Prevalence, characteristics and risk factors. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 10(2), 136–149. 10.1080/17542863.2016.1265999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heath N. L., Ross S. (2007). How i deal with stress. McGill University. (unpublished instrument). [Google Scholar]

- Heerwegh D. (2014). Small sample Bayesian factor analysis. In Phuse. Retrieved from. https://www.lexjansen.com/phuse/2014/sp/SP03.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Izadi-Mazidi M., Yaghubi H., Mohammadkhani P., Hassanabadi H. (2019). Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Factor analysis of functional assessment of self-mutilation among adolescents. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 14(3), 184–191. 10.18502/ijps.v14i3.1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiekens G., Hasking P., Boyes M., Claes L., Mortier P., Auerbach R. P., Bruffaerts R. (2018). The associations between non-suicidal self-injury and first onset suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 171–179. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky E. D., Glenn C. R. (2009). Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(3), 215–219. 10.1007/s10862-008-9107-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky E. D., Glenn C. R., Styer D. M., Olino T. M., Washburn J. J. (2015). The functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: Converging evidence for a two-factor structure. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 44–53. 10.1186/s13034-015-0073-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazos T. A. (2018). Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology, 9(08), 2207–2230. 10.4236/psych.2018.98126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd E. E., Kelley M. L., Hope T. (1997). Self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents: Descriptive characteristics and provisional prevalence rates. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond P. F., Lovibond S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansourian M., Taghdisi M. H., Khosravi B., Ziapour A., Özdenk G. D. (2019). A study of Kurdish women’s tragic self-immolation in Iran: A qualitative study. Burns, 45(7), 1715–1722. 10.1016/j.burns.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merica C. B., Egan C. A., Webster C. A., Mindrila D., Karp G. G., Paul D. R., Rose S. (2023). Measuring physical education teacher socialization with respect to comprehensive school physical activity programming. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 1, 1–13. 10.1123/jtpe.2022-0165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nemati H., Sahebihagh M. H., Mahmoodi M., Ghiasi A., Ebrahimi H., Atri S. B., Mohammadpoorasl A. (2020). Non-suicidal self-injury and its relationship with family psychological function and perceived social support among Iranian high school students. Journal of Research in Health Sciences, 20(1), e00469. 10.34172/jrhs.2020.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock M. K., Favazza A. R. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. In Nock M. K. (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Nock M. K., Prinstein M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A., Bagge C. L., Gutierrez P. M., Konick L. C., Kopper B. A., Barrios F. X. (2001). The suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment, 8(4), 443–454. 10.1177/107319110100800409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez S., García‐Alandete J., Cañabate M., Marco J. H. (2020). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Inventory of Statements about Self‐injury in a Spanish clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 102–117. 10.1002/jclp.22844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei O., Athar M. E., Ebrahimi A., Jazi E. A., Karimi S., Ataie S., Storch E. A. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 8(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s40479-021-00168-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal N., Bhola P., Reddi V. S. K., Bhaskarapillai B., Joseph S. (2021). Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) among emerging adults: Sub-group profiles and their clinical relevance. Psychiatry Research, 300(2), 113877. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stänicke L. I., Haavind H., Gullestad S. E. (2018). How do young people understand their own self-harm? A meta-synthesis of adolescents’ subjective experience of self-harm. Adolescent Research Review, 3(2), 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Straker G. (2006). Signing with a scar: Understanding self-harm. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 16(1), 93–112. 10.2513/s10481885pd1601_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell S. V., Martin G. E., Page A., Hasking P., St John N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self‐injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273–303. 10.1111/sltb.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantrarungroj T., Saipanish R., Lotrakul M., Kusalaruk P., Wisajun P. (2022). Psychometric properties and factor analysis of family accommodation scale for obsessive compulsive disorder-interviewer-rated-Thai version (FAS-T). Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1607–1615. 10.2147/PRBM.S358251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigfusdottir J., Dale K. Y., Gratz K. L., Klonsky E. D., Jonsbu E., Høidal R. (2020). The psychometric properties and clinical utility of the Norwegian versions of the deliberate self-harm inventory and the inventory of statements about self-injury. Current Psychology, 41(10), 1–11. 10.1007/s12144-020-01189-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- You J., Lin M. P., Leung F. (2013). Functions of nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese community adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36(4), 737–745. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]