Abstract

Background

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris (PV) share similar pathophysiology with venous thromboembolism (VTE) involving platelet activation, immune dysregulation, and systemic inflammation. Nevertheless, their associations have not been well established.

Methods and Results

To examine the risk of incident VTE among patients with BP or PV, we performed a nationwide cohort study using Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database and enrolled 12 162 adults with BP or PV and 12 162 controls. A Cox regression model considering stabilized inverse probability weighting was used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) for incident VTE associated with BP or PV. To consolidate the findings, a meta‐analysis that incorporated results from the present cohort study with previous literature was also conducted. Compared with controls, patients with BP or PV had an increased risk for incident VTE (HR, 1.87 [95% CI, 1.55–2.26]; P<0.001). The incidence of VTE was 6.47 and 2.20 per 1000 person‐years in the BP and PV cohorts, respectively. The risk for incident VTE significantly increased among patients with BP (HR, 1.85 [95% CI, 1.52–2.24]; P<0.001) and PV (HR, 1.99 [95% CI, 1.02–3.91]; P=0.04). In the meta‐analysis of 8 studies including ours, BP and PV were associated with an increased risk for incident VTE (pooled relative risk, 2.17 [95% CI, 1.82–2.62]; P<0.001).

Conclusions

BP and PV are associated with an increased risk for VTE. Preventive approaches and cardiovascular evaluation should be considered particularly for patients with BP or PV with concomitant risk factors such as hospitalization or immobilization.

Keywords: bullous pemphigoid, cohort study, meta‐analysis, pemphigus vulgaris, systematic review, venous thromboembolism

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Big Data and Data Standards, Meta Analysis, Embolism, Thrombosis

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BP

bullous pemphigoid

- IPW

inverse probability weighting

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

- PV

pemphigus vulgaris

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

This nationwide cohort study including 24 324 subjects demonstrated that patients with bullous pemphigoid or pemphigus vulgaris had a 1.76‐fold risk for incident venous thromboembolism.

The association remained significant in age‐ and sex‐stratified analyses.

The increased risk of venous thromboembolismin associated with bullous pemphigoid or pemphigus vulgaris was confirmed by a meta‐analysis that incorporated data from this cohort with previous literature.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Evidence from our study suggests an increased risk of incident venous thromboembolism among patients with bullous pemphigoid or pemphigus vulgaris.

Imperative vascular examination and prompt anticoagulation may benefit such patients presenting symptoms suggestive of venous thromboembolism.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) and pemphigus vulgaris (PV) are the 2 most common autoimmune bullous dermatoses predominantly affecting the elderly. 1 , 2 , 3 The pathophysiology of BP and PV is mediated by autoantibodies against structural proteins of cell junctions, causing blisters and erosions on patients' skin or mucous membranes. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 An elevated risk of cardiovascular comorbidities and related mortality has been reported in patients with BP or PV. 8 , 9 , 10

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), comprising deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a global health burden associated with serious morbidity and mortality. 11 , 12 Discoveries of immune alterations and vascular inflammation involved in the thrombogenic mechanism have advanced our knowledge of VTE pathogenesis. 13 , 14 , 15 Several chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders have been reported as risk factors for VTE. 16 , 17 , 18 BP and PV share similar mechanisms with VTE involving immune dysregulation, activation of complement cascade, and systemic inflammation. 19 , 20 , 21 Several case reports have presented the coexistence of BP or PV with VTE. 22 , 23 , 24 Previous epidemiological studies have also explored the association of BP or PV with VTE, but a sustained debate remains. Some studies demonstrated an increased risk of VTE in patients with BP or PV, 25 , 26 whereas others showed contradictory results. 27 , 28 Moreover, most existing studies were from Western countries, thereby limiting their generalizability to other countries or races. Therefore, data from Asian populations are required and a comprehensive meta‐analysis is warranted to synthesize the overall effect estimates incorporating different populations.

Herein, we first conducted a nationwide retrospective cohort study to investigate whether patients with BP or PV had an increased risk developing VTE. To consolidate our findings, a systematic review and meta‐analysis encompassing the present cohort study and previous studies was subsequently performed.

Methods

The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) is managed and supervised by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan. This data set can be used only in the Health and Welfare Data Science Center. Researchers interested in analyzing this data set have to formally request access through the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan (website: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/cp‐2516‐59203‐113.html). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the anonymized data encrypted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Data Source

We performed a nationwide retrospective cohort study using the Taiwan's NHIRD, which contains health care data of ≈23.6 million individuals, representing the entire Taiwanese population. 29 , 30 The NHIRD has been widely used in published epidemiological studies. 30 , 31 , 32 Diagnostic and procedure codes were derived from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM, before 2016) and Tenth Revision (ICD‐10‐CM, after 2016) codes. A data subset of NHIRD, the Catastrophic Illness Dataset, was applied to ascertain the diagnosis of PV. A brief introduction to the Catastrophic Illness Dataset and the reason for using this data set are provided in Data S1. The Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital approved this study (REC No: IRB107‐152‐C).

Study Population

The study population comprised all patients aged ≥20 years who received a new diagnosis of BP or PV from dermatologists between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2017. A diagnosis of BP was defined as a diagnosis confirmed at least 3 times in an outpatient department within 1 year or a discharge diagnosis of ICD‐9‐CM code 694.5 and ICD‐10‐CM code L12. These diagnostic codes have been validated with a high positive predictive value of 98%. 33 , 34 Patients with a diagnosis of PV were identified through the catastrophic illness registry using ICD‐9‐CM code 694.4 and ICD‐10‐CM code L10.0‐L10.9. Patients who received a diagnosis of BP or PV before 2001 were excluded to ensure that newly diagnosed patients were recruited.

The exposed cohort comprised all patients with BP or PV, whereas the unexposed cohort comprised patients without BP or PV. Among the unexposed cohort, we excluded patients with diagnoses of other bullous disorders (ICD‐9 codes: 694.0–694.3, 694.6, 694.8, 694.9; ICD‐10 codes: L11, L13, L14). Each patient in the exposed cohort was individually matched with 1 control subject in the unexposed cohort by age and sex. The index date for patients with BP was the date when the first BP diagnosis was made, whereas the index date for patients with PV was the date of the application for the catastrophic illness certificate. The index date for patients in the unexposed cohort was assigned as the same date as the matched patient. Study subjects with a history of VTE before the index date were excluded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was any incident event of VTE, including DVT (ICD‐9‐CM codes: 453.2, 453.4, 453.5, 453.7, 453.8, 453.9; ICD‐10‐CM codes: I82.2, I82.4, I82.5, I82.60, I82.62, I82.89, I82.9) and PE (ICD‐9‐CM code: 415.1; ICD‐10‐CM code: I26). The diagnostic accuracy of the aforementioned codes has been validated, with high positive predictive value found (94%). 35 An outcome event was defined as a diagnosis made either in the outpatient or inpatient department after the index date. We also conducted individual outcome analyses considering any incident event of DVT and PE. All enrollees were followed from the index date until the occurrence of VTE, death, or December 31, 2018 (the last date of our database), whichever came first. In the individual outcome analysis, patients were followed up until that outcome was observed; that is, patients were not censored if the other outcome occurred earlier.

Covariates and Confounders

We obtained baseline data of subjects from reimbursement claims of NHIRD. Preexisting comorbidities and baseline medication use (Tables S1 and S2), considered potential confounders, were chosen based on previous studies. 36 Preexisting comorbidities were defined as diagnoses on discharge or diagnoses confirmed at least twice in the outpatient services within the year before the index date, using the ICD‐9‐CM, ICD‐10‐CM, and procedure codes. We quantified enrollees' overall systemic health status using the Charlson Comorbidity Index according to preexisting comorbidities. 37 Medication use at baseline was defined as a drug prescribed for at least 30 days within the year before the index date. Monthly income levels were evaluated based on income‐related National Health Insurance premiums.

Subgroup and Stratified Analyses

The exposed cohort was divided into 2 subgroups: a BP cohort comprising only patients with BP and a PV cohort comprising only patients with PV. Additionally, age‐ and sex‐stratified subanalyses were performed. To investigate the effect of cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities on VTE risks associated with the exposed and unexposed cohorts, 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 we conducted stratified analyses for patients with and without comorbidities such as hypertension, atrial fibrillation, stroke, heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and varicose veins. For each comorbidity, we compared the risk of VTE between the exposed and unexposed cohorts in 2 strata: patients with and without that specific comorbidity.

Statistical Analysis

We applied a propensity score‐based approach, stabilized inverse probability weighting (IPW), to mitigate potential selection bias and to balance systematic differences in baseline characteristics between the study cohorts. 42 Standardized mean difference was used to examine the difference in baseline characteristics between the exposed and unexposed cohorts, with a value of <0.1 indicating a negligible difference. A univariable Cox regression model considering IPW was applied to estimate cumulative incidences and hazard ratios (HRs) for each outcome. The cumulative incidence curves were illustrated using Kaplan–Meier methods. If any covariate was imbalanced between the study cohorts after stabilized IPW, we added that covariate into the regression model for additional adjustment to test the robustness of our primary analyses. A 2‐sided probability value of <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses in the cohort study were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis

We conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis to examine the risk of incident VTE among patients with BP or PV and incorporated data from the present study with previous literature. The MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases were searched for relevant publications from their individual inception to October 20, 2022. We included observational studies that reported risk estimates of VTE in patients with BP or PV compared with controls without BP/PV, including cohort, case–control, or cross‐sectional studies. No restrictions on language or geographic locations were imposed. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale was applied to assess the risk of bias of included studies. 43

The Review Manager version 5.4.1 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) was used to conduct random‐effects meta‐analyses. Data were presented as pooled relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs. 44 A P value of <0.05 was deemed significant. We quantified between‐study heterogeneity by I2 statistics, with an I2 of >50% indicating at least moderate heterogeneity. 45 Predefined subgroup meta‐analyses based on BP or PV, study design, and geographic locations were performed to determine if certain study‐level factors may affect the pooled results. The detailed methodology regarding meta‐analysis was provided in Data S2 and Table S3.

Results

Results of the Cohort Study

We originally recruited 24 324 study subjects (12 162 adults with BP or PV and 12 162 controls) from the NHIRD. After applying the stabilized IPW, the exposed cohort comprised 12 021 patients with BP or PV, whereas the unexposed cohort comprised 13 043 control subjects. All the baseline characteristics, except for stroke, dementia, and antipsychotics use, were balanced between the study cohorts after stabilized IPW (Table 1). The baseline characteristics of study cohorts before stabilized IPW are provided in Table S4. The overall mean length of follow‐up was 4.5 years.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population After Stabilized Inverse Probability Weighting

| Characteristics* | With BP or PV (n=12 021) | Without BP or PV (n=13 043) | SMD† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), y | 74.4 (15.62) | 75.5 (15.93) | 0.0672 |

| Sex, % | |||

| Male | 52.57 | 52.11 | 0.0092 |

| Female | 47.43 | 47.89 | 0.0092 |

| Income level (New Taiwan Dollar), % | |||

| Financially dependent | 32.95 | 34.43 | 0.0313 |

| 15 840–24 999 | 41.42 | 40.73 | 0.0140 |

| 25 000–39 999 | 9.87 | 9.24 | 0.0214 |

| ≥40 000 | 15.76 | 15.60 | 0.0044 |

| Mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (SD) | 1.41 (1.53) | 1.57 (1.81) | 0.0955 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||

| Hypertension | 51.52 | 53.17 | 0.0330 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.78 | 4.99 | 0.0591 |

| Stroke | 26.98 | 31.58 | 0.1012 |

| Heart failure | 7.09 | 8.09 | 0.0378 |

| Coronary artery disease | 14.82 | 16.11 | 0.0357 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 16.19 | 19.24 | 0.0799 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6.13 | 7.25 | 0.0448 |

| Cirrhosis | 1.16 | 1.24 | 0.0073 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 15.51 | 15.75 | 0.0066 |

| Fracture of lower limbs | 3.18 | 3.74 | 0.0306 |

| Gout | 5.86 | 5.67 | 0.0082 |

| Malignancy | 6.81 | 6.59 | 0.0088 |

| Pregnancy | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.0074 |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 1.33 | 1.58 | 0.0209 |

| Dementia | 14.77 | 20.39 | 0.1480 |

| Epilepsy | 2.46 | 4.23 | 0.0986 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.0094 |

| Anxiety | 8.20 | 9.27 | 0.0379 |

| Depression | 6.85 | 8.33 | 0.0559 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.0064 |

| Autoimmune disease | 2.73 | 2.83 | 0.0061 |

| Diabetes | 25.62 | 28.36 | 0.0618 |

| Varicose veins | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.0626 |

| Baseline medication use, % | |||

| Hormone therapies | 1.13 | 1.09 | 0.0038 |

| Statins | 14.19 | 14.05 | 0.0040 |

| Antiplatelets | 31.38 | 32.25 | 0.0187 |

| Warfarin | 1.31 | 1.52 | 0.0178 |

| Dabigatran | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.0252 |

| Rivaroxaban | 0.36 | 0.59 | 0.0335 |

| Apixaban | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.0027 |

| Edoxaban | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.0082 |

| Antipsychotics | 11.12 | 14.87 | 0.1117 |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors | 6.13 | 7.63 | 0.0593 |

BP indicates bullous pemphigoid; PV, pemphigus vulgaris; and SMD, standardized mean difference.

All covariates listed were used to calculate the propensity score for inverse probability weighting.

A standardized mean difference of <0.1 indicates a negligible difference.

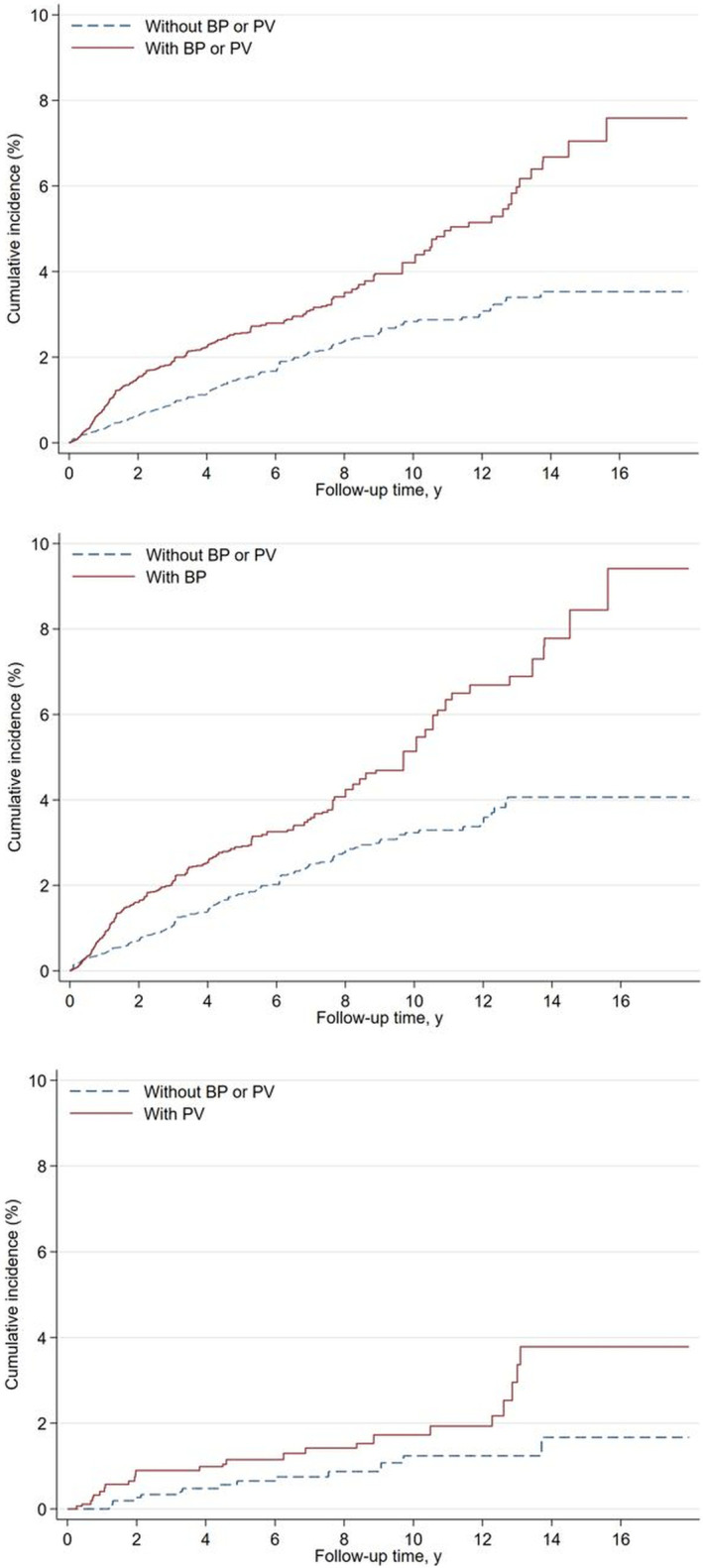

Overall, patients with BP or PV were at an increased risk for incident VTE compared with controls (HR, 1.87 [95% CI, 1.55–2.26]; P<0.001; Table 2). When divided by subgroups, 240 patients in the BP cohort and 24 patients in the PV cohort developed VTE. The incidence of VTE was 6.47 and 2.20 per 1000 person‐years in the BP and PV cohorts, respectively. The risk for incident VTE was significantly increased among patients with BP (HR, 1.85 [95% CI, 1.52–2.24]; P<0.001) and PV (HR, 1.99 [95% CI, 1.02–3.91]; P=0.04). The cumulative incidence curves are presented in Figure 1. Regarding the individual outcome analyses (Table 2), patients with BP or PV were at a significantly higher risk for incident DVT (HR, 2.09 [95% CI, 1.68–2.61]; P<0.001) but not for incident PE (HR, 1.39 [95% CI, 0.99–1.97]; P=0.061). The results of sensitivity analyses by additional adjustment for stroke, dementia, and antipsychotic use were similar to our primary analysis (Table S5).

Table 2.

Risk of Venous Thromboembolism Among Patients With Bullous Pemphigoid or Pemphigus Vulgaris

| Outcomes/comparison | Exposed cohort | Unexposed cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Events | IR* | n | Events | IR* | HR† (95% CI) | P value | |

| Venous thromboembolism | ||||||||

| Overall cohort vs unexposed cohort | 12 021 | 264 | 5.42 | 13 043 | 183 | 2.85 | 1.87 (1.55–2.26) | <0.001 |

| BP cohort vs unexposed cohort | 10 572 | 240 | 6.47 | 11 569 | 178 | 3.41 | 1.85 (1.52–2.24) | <0.001 |

| PV cohort vs unexposed cohort | 1439 | 24 | 2.20 | 1438 | 13 | 1.10 | 1.99 (1.02–3.91) | 0.04 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | ||||||||

| Overall cohort vs unexposed cohort | 12 021 | 209 | 4.28 | 13 043 | 129 | 2.01 | 2.09 (1.68–2.61) | <0.001 |

| BP cohort vs unexposed cohort | 10 572 | 187 | 5.03 | 11 569 | 124 | 2.37 | 2.08 (1.66–2.61) | <0.001 |

| PV cohort vs unexposed cohort | 1439 | 22 | 1.98 | 1438 | 13 | 1.10 | 1.80 (0.91–3.57) | 0.093 |

| Pulmonary embolism | ||||||||

| Overall cohort vs unexposed cohort | 12 021 | 68 | 1.37 | 13 043 | 62 | 0.96 | 1.39 (0.99–1.97) | 0.061 |

| BP cohort vs unexposed cohort | 10 572 | 63 | 1.68 | 11 569 | 63 | 1.19 | 1.36 (0.96–1.93) | 0.083 |

| PV cohort vs unexposed cohort | 1439 | 4 | 0.34 | 1438 | 0 | 0 | NA | |

BP indicates bullous pemphigoid; PV, pemphigus vulgaris; HR, hazard ratio; IR, incidence rate; and NA, not applicable.

Incidence rate per 1000 person‐years.

The HRs were calculated using a univariable Cox regression model with inverse probability weighting and using the corresponding unexposed cohort (patients without BP or PV) as the reference.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence curves for venous thromboembolism in the overall, bullous pemphigoid, and pemphigus vulgaris cohorts.

BP indicates bullous pemphigoid; and PV, pemphigus vulgaris.

In the age‐ and sex‐stratified analyses, the increased risks for incident VTE associated with BP or PV remained significant across all age and sex subgroups (Table 3; see Table S6). In the analyses stratified by various cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities, a similar trend of higher VTE risk in patients with BP or PV was still observed in each comorbidity stratum, though some did not reach statistical significance; this could be due to the reduced sample size/event number after dividing patients into different comorbidity subgroups, especially those with certain comorbidities (eg, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, varicose veins) (Table S6).

Table 3.

Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With Bullous Pemphigoid or Pemphigus Vulgaris Compared With Controls, Stratified by Age and Sex

| Outcomes | Venous thromboembolism | Deep vein thrombosis | Pulmonary embolism | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR* | 95% CI | P value | HR* | 95% CI | P value | HR* | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | |||||||||

| <65 y | 1.95 | 1.21–3.14 | 0.006 | 2.05 | 1.19–3.52 | 0.010 | 1.62 | 0.59–4.44 | 0.345 |

| ≥65 y | 1.99 | 1.62–2.45 | <0.001 | 2.30 | 1.81–2.93 | <0.001 | 1.42 | 0.99–2.06 | 0.060 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 2.05 | 1.57–2.67 | <0.001 | 2.46 | 1.82–3.34 | <0.001 | 1.09 | 0.64–1.85 | 0.760 |

| Female | 1.66 | 1.27–2.17 | <0.001 | 1.73 | 1.25–2.38 | 0.001 | 1.58 | 1.01–2.47 | 0.046 |

HR indicates hazard ratio.

The HRs were calculated using a univariable Cox regression model with inverse probability weighting and using the unexposed cohort (patients without bullous pemphigoid or pemphigus vulgaris) as the reference.

Results of the Meta‐Analysis

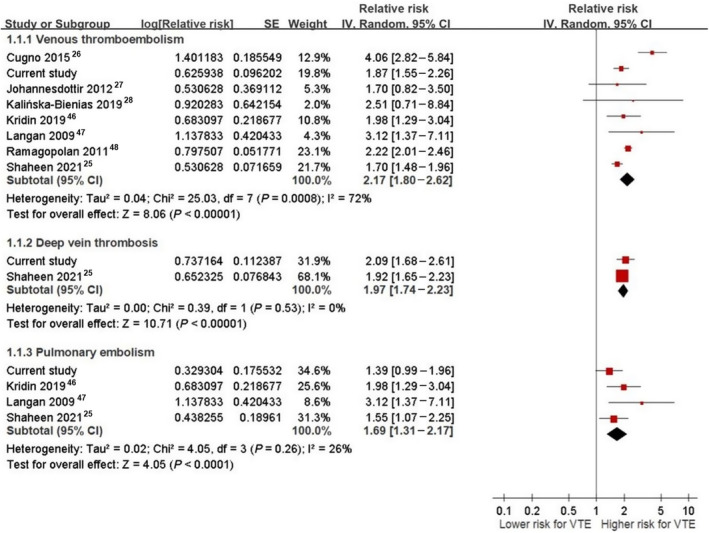

After including the present cohort study, a total of 8 studies 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 46 , 47 , 48 with 61 600 subjects were eligible for a meta‐analysis. As illustrated in Figure 2, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 46 , 47 , 48 our meta‐analysis indicated that patients with BP or PV were at an increased risk for incident VTE (pooled RR, 2.17 [95% CI, 1.80–2.62]; I2=72%), DVT (pooled RR, 1.97 [95% CI, 1.74–2.23]; I2=0%), and PE (pooled RR, 1.69 [95% CI, 1.31–2.17]; I2=26%) when compared with controls. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses flow diagram, summary of risk of bias assessment, and characteristics of included studies are respectively provided in Figures S1 and S2 and Table S7. Subgroup meta‐analyses generated similar results and revealed that study design might be a potential effect modifier to influence the pooled RR (see Figures S3 through S5).

Figure 2. Forest plots of the meta‐analysis.

The meta‐analysis illustrated a significant association of bullous pemphigoid or pemphigus vulgaris with venous thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. IV indicates inverse variance; and VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest cohort and most comprehensive study examining current evidence regarding the risk of incident VTE among patients with BP or PV. Our nationwide cohort study illustrated a 1.76‐fold HR of developing VTE among patients with BP or PV when compared with controls. The increased risk for incident VTE associated with BP or PV remained significant on stratification by age and sex. The pooled results from meta‐analysis further confirmed the significant association of BP or PV with incident VTE.

Although the exact mechanism was not fully elucidated, previous studies have provided mechanistic clues to support our findings. First, activation of coagulation cascades has been observed in patients with BP and PV. 49 Serum markers for both thrombin formation (plasma prothrombin fragments F1+2) and fibrin degradation (D‐dimer) were significantly higher among patients with BP than controls. 20 , 50 Skin tissue factor, an initiator of coagulation, was also expressed in patients with BP. 50 Second, multiple proinflammatory cytokines were found to be increased in patients with BP and PV, suggesting that BP and PV are autoimmune diseases with systemic inflammation. 51 , 52 , 53 It is believed that type 2 inflammation triggers the formation of autoantibodies in BP. 54 The levels of interleukin (IL)‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐13 were reportedly elevated in the serum, blister fluid, and skin biopsy specimens among patients with BP. 55 These cytokines may also involve the pathogenesis of VTE. 56 Serum levels of soluble E‐selectin and vascular endothelial growth factor in BP were associated with those of circulating autoantibodies, which supported the interaction between activated endothelial inflammatory and immune reactions. 57 , 58 Eosinophils in BP and PV are also believed to involve in coagulation activation at skin levels. 59 Third, antiphospholipid antibodies have been detected in patients with BP and PV. 60 , 61 Antiphospholipid antibodies comprised a heterogeneous group of antibodies that could produce a prothrombotic state and are related to thrombotic events. 61 Future research is warranted to clarify the underlying mechanisms between inflammation, immune dysregulation, and coagulation.

A cross‐sectional study reported associations of BP with VTE (odds ratio [OR], 1.64 [95% CI, 1.47–1.83]) and PV with VTE (OR, 1.96 [95% CI, 1.68–2.28]). 25 However, the authors could not elucidate the temporal relationship. Two case–control studies reported that BP might not be a risk factor of VTE. 27 , 28 Several cohort studies have also investigated the risk of VTE among patients with BP or PV. 26 , 46 , 47 , 48 However, these studies mainly focused on people in Western countries, with a resultant lack of generalizability. Our nationwide cohort analysis used data from an Asian population to complement this topic with the largest sample size to date. Recently, a retrospective cohort study suggested BP as a risk factor for VTE (HR, 2.02 [95% CI, 1.01–4.06]). 62 In comparison to that study, we additionally investigated the VTE risk among patients with PV. Moreover, we conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis to compile all the available data. The findings from our study provided comprehensive real‐world evidence regarding the risk of VTE among patients with BP and PV and also extended the generalizability based on previous literature.

A previous meta‐analysis from 2018 has evaluated the association of BP with VTE. 63 Nevertheless, this analysis enrolled only 4 studies from Europe. Because recent studies have provided additional new data, our meta‐analysis enrolled more studies across different populations (one from the United States, one from Israel, and our nationwide cohort study from Taiwan) to provide better generalizability.

The substantial heterogeneity in our meta‐analysis may be partially explained by the study design of included studies. The pooled RR from cohort studies was higher than that from case–control and cross‐sectional studies. Although the heterogeneity was still high in the subanalysis regarding cohort studies, the conclusion from these studies was consistent. Further investigations with individual patient data may be instrumental in providing in‐depth analyses.

The risk for PE among patients with BP or PV was not significant in our cohort study, which might be attributed to the low incidence of PE in the exposed cohort. However, when the estimates were pooled together in the meta‐analysis (Figure 2), a significant association of BP or PV with PE was indicated. This finding may emphasize the value of meta‐analysis to provide sufficient statistical power.

The main strength of this study is that we not only conducted a population‐based cohort study but also incorporated it into the existing literature to strengthen the evidence. However, the results need to be interpreted in context with its limitations. First, NHIRD used in our cohort analysis lacks data on body mass index, smoking history, physical activity, lifestyle, and laboratory data. Given the application of stabilized IPW to minimize potential confounding effects, residual confounders might have still existed. Second, the diagnoses of BP, PV, and VTE were mainly based on ICD codes. Although the codes have been reportedly validated with high positive predictive values, misclassification bias was inevitable. Third, the present study did not include the increasingly prescribed immune checkpoint inhibitors, which might be considered as potential confounders, 64 because these medications were not reimbursed by Taiwan's National Health Insurance program until 2019. Fourth, a novel treatment for pemphigoid diseases, rituximab, was not studied because the National Health Insurance program did not cover this drug during the study period. As case reports have discussed the potential effect of rituximab on VTE, 10 , 65 further studies are needed to focus on the impact of rituximab on VTE risk among patients with BP and PV.

Conclusions

In conclusion, BP and PV are associated with increased risk for VTE based on real‐world evidence from this cohort study and meta‐analysis. Preventive approaches and cardiovascular evaluation should be considered particularly for patients with BP or PV and concomitant risk factors, such as hospitalization or immobilization. Prompt anticoagulation and multidisciplinary care could be considered in patients with BP or PV presenting symptoms suggestive of VTE, such as unexplained dyspnea, chest pain, or leg swelling. Based on its significant morbidity, the risk of VTE among patients with BP and PV should deserve more public health concern.

Sources of Funding

This study received a grant from the Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital (TCRD108‐21). The funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting of the article, decision to submit for publication, or approval of the article for publication.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Yu‐Ru Kou (Institute of Physiology, School of Medicine, National Yang‐Ming Chiao‐Tung University, Taiwan; Department of Medical Research, Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Taiwan) for his comments. The authors also thank the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, for maintaining and processing the data within the database, and the Health and Welfare Data Science Center of Tzu Chi University for facilitating data extraction.

This article was sent to Yen‐Hung Lin, MD, PhD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.029740

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

See Editorial by Chih‐Hsin Hsu and Chao‐Kai Hsu.

Contributor Information

Huei‐Kai Huang, Email: drhkhuang@gmail.com.

Ching‐Chi Chi, Email: chingchi@cgmh.org.tw.

References

- 1. Kayani M, Aslam AM. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris. BMJ. 2017;357:j2169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Narla S, Silverberg JI. Associations of pemphigus or pemphigoid with autoimmune disorders in US adult inpatients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:586–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu CY, Wu CY, Lin YH, Chang YT. Statins did not reduce the mortality risk in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a population‐based cohort study. Dermatol Sin. 2021;39:153–154. doi: 10.4103/ds.ds_14_21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet. 2013;381:320–332. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61140-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Egami S, Yamagami J, Amagai M. Autoimmune bullous skin diseases, pemphigus and pemphigoid. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:1031–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Endo M, Watanabe Y, Yamamoto M, Igari S, Kikuchi N, Yamamoto T. Erythrodermic bullous pemphigoid. Dermatol Sin. 2021;39:61–62. doi: 10.4103/ds.ds_45_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin JD, Hung SJ. Radiation‐induced bullous pemphigoid in a patient with Kaposi's sarcoma. Dermatol Sin. 2021;39:159–160. doi: 10.4103/ds.ds_23_21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rokni AM, Ayasse M, Ahmed A, Guggina L, Kantor RW, Silverberg JI. Association of autoimmune blistering disease, and specifically, pemphigus vulgaris, with cardiovascular disease and its risk factors: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;315:207–213. doi: 10.1007/s00403-022-02346-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen WC, Chiang HY, Chen PS, Lin YT, Kuo CC, Wu PY. Risk of all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, and cancer mortality in patients with bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:167–175. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu K‐J, Wei K‐C. Venous thromboembolism in a case with pemphigus vulgaris after infusion of rituximab plus systemic glucocorticoids and azathioprine: a possible adverse effect of rituximab? Dermatol Sin. 2021;39:103–104. doi: 10.4103/ds.ds_7_21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tritschler T, Kraaijpoel N, Le Gal G, Wells PS. Venous thromboembolism: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018;320:1583–1594. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wolberg AS, Rosendaal FR, Weitz JI, Jaffer IH, Agnelli G, Baglin T, Mackman N. Venous thrombosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15006. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colling ME, Tourdot BE, Kanthi Y. Inflammation, infection and venous thromboembolism. Circ Res. 2021;128:2017–2036. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.121.318225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cushman M, Barnes GD, Creager MA, Diaz JA, Henke PK, Machlus KR, Nieman MT, Wolberg AS. Venous thromboembolism research priorities: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Circulation. 2020;142:e85–e94. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stark K, Massberg S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:666–682. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00552-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ogdie A, Kay McGill N, Shin DB, Takeshita J, Jon Love T, Noe MH, Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Choi HK, Mehta NN, Gelfand JM. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a general population‐based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3608–3614. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zöller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with autoimmune disorders: a nationwide follow‐up study from Sweden. Lancet. 2012;379:244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61306-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen TL, Lee LL, Huang HK, Wang JH, Chen LY, Tsai HR, Loh CH, Chi CC. Association of psoriasis with incident venous thromboembolism and peripheral vascular disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:59–67. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cugno M, Tedeschi A, Asero R, Meroni PL, Marzano AV. Skin autoimmunity and blood coagulation. Autoimmunity. 2010;43:189–194. doi: 10.3109/08916930903293086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marzano AV, Tedeschi A, Fanoni D, Bonanni E, Venegoni L, Berti E, Cugno M. Activation of blood coagulation in bullous pemphigoid: role of eosinophils, and local and systemic implications. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:266–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;11:175–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marchalik R, Reserva J, Plummer MA, Braniecki M. Pemphigus vegetans with coexistent herpes simplex infection and deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015210143. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leshem YA, Atzmony L, Dudkiewicz I, Hodak E, Mimouni D. Venous thromboembolism in patients with pemphigus: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ashraf O, Sharif H. Pulmonary embolism in pemphigus vulgaris, the need for judicious immunotherapy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2005;55:306–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaheen MS, Silverberg JI. Association of inflammatory skin diseases with venous thromboembolism in US adults. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313:281–289. doi: 10.1007/s00403-020-02099-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cugno M, Marzano AV, Bucciarelli P, Balice Y, Cianchini G, Quaglino P, Calzavara Pinton P, Caproni M, Alaibac M, De Simone C, et al. Increased risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with bullous pemphigoid. The INVENTEP (INcidence of VENous ThromboEmbolism in bullous Pemphigoid) study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:193–199. doi: 10.1160/th15-04-0309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johannesdottir SA, Schmidt M, Horváth‐Puhó E, Sørensen HT. Autoimmune skin and connective tissue diseases and risk of venous thromboembolism: a population‐based case‐control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:815–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04666.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kalińska‐Bienias A, Kowalczyk E, Jagielski P, Bienias P, Kowalewski C, Woźniak K. The association between neurological diseases, malignancies and cardiovascular comorbidities among patients with bullous pemphigoid: case‐control study in a specialized Polish center. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019;28:637–642. doi: 10.17219/acem/90922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsieh CY, Su CC, Shao SC, Sung SF, Lin SJ, Kao Yang YH, Lai EC. Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:349–358. doi: 10.2147/clep.S196293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hsing AW, Ioannidis JP. Nationwide population science: lessons from the Taiwan ational Health Insurance Research Database. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1527–1529. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ting HC, Ma SH, Tai YH, Dai YX, Chang YT, Chen TJ, Chen MH. Association between alopecia areata and retinal diseases: a nationwide population‐based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;87:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang SH, Wang J, Lin YS, Tung TH, Chi CC. Increased risk for incident thyroid diseases in people with psoriatic disease: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu CY, Wu CY, Li CP, Chou YJ, Lin YH, Chang YT. Association between dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors and risk of bullous pemphigoid in patients with type 2 diabetes: a population‐based cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;171:108546. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu CY, Wu CY, Li CP, Lin YH, Chang YT. Association of Immunosuppressants with mortality of patients with bullous pemphigoid: a nationwide population‐based cohort study. Dermatology. 2022;238:378–385. doi: 10.1159/000516632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ng KJ, Lee YK, Huang MY, Hsu CY, Su YC. Risks of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:206–213. doi: 10.1111/jth.12805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goldhaber SZ. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Anderson FA Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107:I9–I16. doi: 10.1161/01.Cir.0000078469.07362.E6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Børvik T, Brækkan SK, Enga K, Schirmer H, Brodin EE, Melbye H, Hansen JB. COPD and risk of venous thromboembolism and mortality in a general population. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:473–481. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00402-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chang SL, Huang YL, Lee MC, Hu S, Hsiao YC, Chang SW, Chang CJ, Chen PC. Association of varicose veins with incident venous thromboembolism and peripheral artery disease. JAMA. 2018;319:807–817. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ageno W, Becattini C, Brighton T, Selby R, Kamphuisen PW. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism: a meta‐analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:93–102. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.709204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Desai RJ, Franklin JM. Alternative approaches for confounding adjustment in observational studies using weighting based on the propensity score: a primer for practitioners. BMJ. 2019;367:l5657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wells G, Shea BJ, O'Connell D, Robertson J. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta‐analysis. Accessed October 10, 2022. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 44. JPT H, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane; 2022. Accessed October 10, 2022. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 45. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kridin K, Kridin M, Amber KT, Shalom G, Comaneshter D, Batat E, Cohen AD. The risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with pemphigus: a population‐based large‐scale longitudinal study. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1559. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Langan SM, Hubbard R, Fleming K, West J. A population‐based study of acute medical conditions associated with bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1149–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ramagopalan SV, Wotton CJ, Handel AE, Yeates D, Goldacre MJ. Risk of venous thromboembolism in people admitted to hospital with selected immune‐mediated diseases: record‐linkage study. BMC Med. 2011;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cugno M, Tedeschi A, Borghi A, Bucciarelli P, Asero R, Venegoni L, Griffini S, Grovetti E, Berti E, Marzano AV. Activation of blood coagulation in two prototypic autoimmune skin diseases: a possible link with thrombotic risk. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marzano AV, Tedeschi A, Berti E, Fanoni D, Crosti C, Cugno M. Activation of coagulation in bullous pemphigoid and other eosinophil‐related inflammatory skin diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;165:44–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04391.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Timoteo RP, da Silva MV, Miguel CB, Silva DA, Catarino JD, Rodrigues Junior V, Sales‐Campos H, Freire Oliveira CJ. Th1/Th17‐related cytokines and chemokines and their implications in the pathogenesis of pemphigus vulgaris. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:7151285. doi: 10.1155/2017/7151285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Echigo T, Hasegawa M, Shimada Y, Inaoki M, Takehara K, Sato S. Both Th1 and Th2 chemokines are elevated in sera of patients with autoimmune blistering diseases. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;298:38–45. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0661-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sun CC, Wu J, Wong TT, Wang LF, Chuan MT. High levels of interleukin‐8, soluble CD4 and soluble CD8 in bullous pemphigoid blister fluid. The relationship between local cytokine production and lesional T‐cell activities. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1235–1240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03894.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang L, Chen Z, Wang L, Luo X. Bullous pemphigoid: the role of type 2 inflammation in its pathogenesis and the prospect of targeted therapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1115083. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1115083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kowalski EH, Kneibner D, Kridin K, Amber KT. Serum and blister fluid levels of cytokines and chemokines in pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Najem MY, Couturaud F, Lemarié CA. Cytokine and chemokine regulation of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1009–1019. doi: 10.1111/jth.14759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bieber K, Ernst AL, Tukaj S, Holtsche MM, Schmidt E, Zillikens D, Ludwig RJ, Kasperkiewicz M. Analysis of serum markers of cellular immune activation in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:1248–1252. doi: 10.1111/exd.13382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. D'Auria L, Cordiali Fei P, Pietravalle M, Ferraro C, Mastroianni A, Bonifati C, Giacalone B, Ameglio F. The serum levels of sE‐selectin are increased in patients with bullous pemphigoid or pemphigus vulgaris. Correlation with the number of skin lesions and recovery after corsticosteroid therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:59–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.1768185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tedeschi A, Marzano AV, Lorini M, Balice Y, Cugno M. Eosinophil cationic protein levels parallel coagulation activation in the blister fluid of patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:813–817. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Echigo T, Hasegawa M, Inaoki M, Yamazaki M, Sato S, Takehara K. Antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with autoimmune blistering disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sagi L, Baum S, Barzilai O, Ram M, Bizzaro N, SanMarco M, Shoenfeld Y, Sherer Y. Novel antiphospholipid antibodies in autoimmune bullous diseases. Hum Antibodies. 2014;23:27–30. doi: 10.3233/hab-140280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen TL, Lee LL, Huang HK, Chen LY, Loh CH, Chi CC. Association of risk of incident venous thromboembolism with atopic dermatitis and treatment with Janus kinase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1254–1261. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ungprasert P, Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:22–26. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_827_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moik F, Chan WE, Wiedemann S, Hoeller C, Tuchmann F, Aretin MB, Fuereder T, Zöchbauer‐Müller S, Preusser M, Pabinger I, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of venous and arterial thromboembolism in immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Blood. 2021;137:1669–1678. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Garabet L, Holme PA, Darne B, Khelif A, Tvedt THA, Michel M, Ghanima W. The risk of thromboembolism associated with treatment of ITP with rituximab: adverse event reported in two randomized controlled trials. Blood. 2019;134:4892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-126974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huang YH, Kuo CF, Chen YH, Yang YW. Incidence, mortality, and causes of death of patients with pemphigus in Taiwan: a nationwide population‐based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:92–97. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hsu YC, Lin JT, Chen TT, Wu MS, Wu CY. Long‐term risk of recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis: a 10‐year nationwide cohort study. Hepatology. 2012;56:698–705. doi: 10.1002/hep.25684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Seo HJ, Kim SY, Lee YJ, Jang BH, Park JE, Sheen SS, Hahn SK. A newly developed tool for classifying study designs in systematic reviews of interventions and exposures showed substantial reliability and validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;70:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ohn J, Eun SJ, Kim DY, Park HS, Cho S, Yoon HS. Misclassification of study designs in the dermatology literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Symons MJ, Moore DT. Hazard rate ratio and prospective epidemiological studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:893–899. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00443-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cummings P. The relative merits of risk ratios and odds ratios. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:438–445. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.