Summary box.

Family planning and comprehensive abortion care education deserve a place in the curricula of all primary healthcare workers as an integral part of reproductive health services.

In many contexts, limitations in health workforce education and continuing professional development leave health workers with gaps in knowledge and skills of family planning and comprehensive abortion care, which have a central role in reproductive health.

Effective learning approaches, such as competency-based learning with learner-centred approach and focus on performance-based and evidence-based assessments, are necessary for improving the quality of health workforce education and learning systems related to family planning and comprehensive abortion care.

In 2022, using a rigorous and consultative methodology, the World Health Organization produced the Family Planning and Comprehensive Abortion Care Toolkit for the primary healthcare workforce that defines the key competencies required for health workers to provide quality family planning and comprehensive abortion care and guidance on how to develop programmes and curricula for their education and lifelong learning.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that health services are only as effective as those responsible for delivering them.1 Access to a qualified health workforce is essential to receiving effective, timely, affordable, equitable and respectful sexual and reproductive health services, including information, which is fundamental to attaining the highest possible level of health and well-being and for the realisation of their human rights.2 A qualified and competent health workforce is critical for strengthening health systems and the delivery of quality primary healthcare, including family planning (FP) and comprehensive abortion care (CAC).2 However, in many countries FP and CAC are being delivered by health workers who have never had the opportunity to learn the competencies needed to provide the full continuum of FP and CAC services.3 4

Existing gaps in health workforce education

Limitations in FP and CAC health workforce education, learning and continuing professional development compromise standards.3 4 In many countries, health workers lack the competencies required to deliver quality FP and CAC services.5–18 Globally, despite overwhelming agreement that medical school curricula should include FP and CAC, training in FP has often been found to be inadequate11 and training in CAC is either altogether missing or significantly limited12 13; especially in low-income countries and countries where abortion is heavily restricted.5–7 12 When abortion care does appear in medical school curricula and postgraduate training, the focus is confined to the legal and ethical aspects of the procedure.13 14 Many barriers to providing FP and CAC education have been identified, including cultural and religious taboos, stigma, unavailability of qualified and willing staff, lack of curriculum time, limited political will and low prioritisation of women’s rights. However, educators recognise the urgent need to teach FP and CAC given their shared commonality and societal impact.15

Inadequate formal education and on-the-job learning can undermine health worker confidence in delivering FP and CAC services13 and permit enduring negative attitudes and behaviours that create barriers to access to FP and CAC services.5 15 A systematic review of health workers’ values and preferences regarding FP concluded that provision may be harmfully affected by bias, and that, to address this gap, improved and standardised education and training were needed globally.16 Similarly, it has been demonstrated that health workers in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia have conservative attitudes towards induced abortion. These attitudes influenced the behaviour and the performance of the health workforce and manifested in a judgemental approach towards women seeking an induced abortion.17

All primary healthcare workers must be fully and adequately educated in FP and CAC interventions to be considered competent.18 19 Improving the quality of health workforce education, learning and continuing professional development using effective learning approaches is necessary for strengthening healthcare systems globally, including those that deliver FP and CAC services.4

WHO defines competencies as: ‘…the abilities of a person to integrate knowledge, skills and attitudes in their performance of tasks in a given context. Competencies are durable, trainable and, through the expression of behaviours, measurable’.20 Competency-based education and learning focus on outcomes, emphasise the learner’s ability to perform, promote greater learner centredness and link the health needs of the population to the competencies required of health workers providing FP and CAC.21–23 Competencies generally specify minimum standards and the conditions within which they should be applied.24 The competencies needed to provide FP and CAC are best embedded in a competency-based education and learning system with competency-based performance assessment.

In 2011, WHO published a guidance document, Sexual and reproductive health—Core competencies in primary care, defining the competencies that primary care providers need to safely deliver SRH services at community level and included FP and CAC.25 These competencies were designed to inform preservice education, management of SRH services, client care and to improve universal access to quality health services. In 2020, as part of formative efforts to update the guidance, an assessment of published literature on how the 2011 WHO SRH—Core competencies in primary care document had been used discovered that the framework presented some important gaps and was not widely adopted. From this process, it was determined that specific FP and CAC competencies for health workers in primary healthcare should be provided to facilitate ease of uptake in a variety of contexts, place greater emphasis on attitudes, behaviours and managing care in restrictive environments, increase focus on people in vulnerable settings, such as adolescents and people with disabilities, and include innovative tools to support integration and implementation of the competencies. The 2022 WHO Family Planning and Comprehensive Abortion Care Toolkit for the primary healthcare workforce or the FP and CAC Toolkit incorporates all these characteristics.26 27

WHO FP and CAC Toolkit

The FP and CAC Toolkit defines the key competencies for health workers in primary healthcare providing quality FP and CAC services, as well as provides guidance for integrating the competencies into educational programmes. The Toolkit was developed based on a rigorous multistage consultative process, including engagement with a wide range of global stakeholders and potential users from different countries and organisations via focus groups, a Delphi process and a Town Hall validation meeting. The toolkit also includes a Programme and Curriculum Development Guide which presents a systematic approach to developing programmes and curricula for the implementation of the FP and CAC competencies, and the theory behind the competency-based education approach.

The FP and CAC competencies

The FP and CAC competencies, which are based on recent evidence and guidelines, set standards for education, learning and performance. They provide a shared language and a benchmark for the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed in FP and CAC services. The competencies are targeted to all professionals involved in the delivery of FP and CAC care, including health workers, managers, policymakers and programme makers, government officials, institutional leaders and educators. The most relevant uses for the FP and CAC competencies are for curriculum development for preservice education and as learning outcomes for the identification of learning needs, curriculum development, professional development, in-service learning, assessment and qualification. Furthermore, the competencies can be used as performance standards for recruitment, job descriptions, performance appraisal, promotion and health workforce optimisation. Managers, educators, supervisors and health workers can use the FP and CAC competencies to identify areas for further improvement. Finally, the FP and CAC competencies can be used to define scopes of practice and for regulating service providers. It is intended to focus on the core functions of the primary healthcare workforce providing FP and CAC services within broader efforts toward achieving universal health coverage.

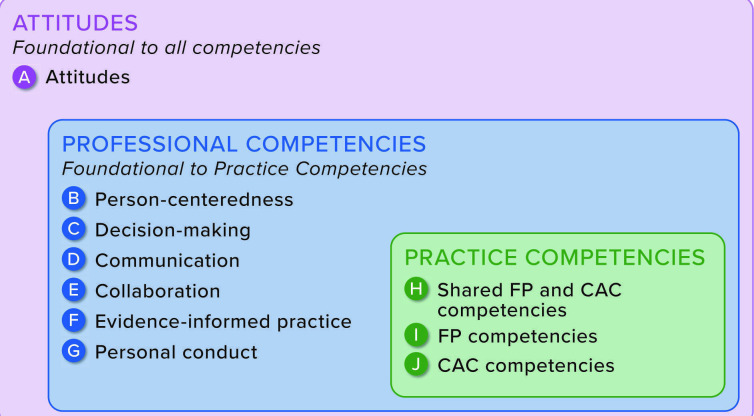

The toolkit describes 57 FP and CAC competencies, which are organised into 10 domains. The 10 domains are grouped into three competency groups: Attitudes, Professional Competencies and Practice Competencies (figure 1). The FP and CAC competencies are presented as a menu, which allows users to select relevant competencies for different groups of health workers, based on their healthcare setting and country context. The order in which domains (and competencies within each domain) are presented is arbitrary, as is the order of the behaviours and items of knowledge listed for each competency.

Figure 1.

Domains of FP and CAC competencies for the primary health care workforce.

Within the first competency group, Attitudes, Domain A presents 12 competencies that refer to the values and beliefs that shape an individual’s behaviour and the performance of tasks. These include, but are not limited to, respect for human rights, and individual choices, behaviours in accordance with professional ethics and standards, accountability and transparency, and sound clinical judgement.26 An individual’s attitudes and values will have a profound impact on the way they perform certain tasks.28 They underpin the motivation, commitment and quality of performance, but there is no agreed methodology to directly measure them, as it is simple to express a set of attitudes and values without true commitment. In the context of FP and CAC service provision, it is important that the expressed behaviours demonstrate the necessary attitudes, for example, a non-judgemental approach to care.

Professional competencies (Domains B–G) are the second group of competencies. They are overarching and apply to all areas of health practice and others. Health workers need to use these Professional Competencies to perform the Practice Competencies (Domains H–J), the third group of competencies which are specific and, in many cases, only performed by FP and CAC occupations. In total, the toolkit lists 23 Professional Competencies and 22 Practice Competencies that are specific to FP and CAC and are required for the performance of technical tasks and are typically outlined in service protocols. All Professional and Practice Competencies are specified in terms of specific behaviours, as well as the areas of knowledge, that are required for competent performance (figure 1).

The competencies are flexible and can be used in conjunction with WHO Abortion care guideline,29 Family planning: a global handbook for providers30 and other guidelines that offer recommendations for the delivery of FP.31 32 They can also be adapted to local policy, regulatory and health systems’ contexts.

Programme and curriculum development guide: an Educational Design Model

The toolkit also offers an Educational Design Model to guide users in translating the FP and CAC competencies into programmes and curricula for formal preservice and in-service education, postgraduate studies and continuing professional development for healthcare workers, table 1.27 The step-by-step guide is specifically targeted to programme and curriculum developers who are preparing or revising formal education and learning programmes for the health workforce. The Model includes six phases—(I) build foundations, (II) plan, (III) construct, (IV) sequence, (V) assess and (VI) implement—and the imbedded steps should be followed in order. For each step, the guide provides a clear and detailed explanation for implementation. For example, in Phase I, the first step calls for the creation of a vision statement. The Educational Design Model provides an example of a possible structure of a vision statement and indicates the information that should be included.27

Table 1.

Educational Design Model

| In the phases 1 and 2, we prepare | ||

| Phase 1: Build foundations | ||

| Step 1: | Create a mission statement | The purpose (what the programme does and why) and its commitments to its learners and broader community. |

| Step 2: | Create a vision statement | High-level goals and hopes for the future, what the institution hopes to achieve if they successfully fulfil their mission. |

| Step 3: | Set core values | Guiding principles, fundamental convictions and ideals – standards which provide a reference point for institutional decision-making. |

| Phase 2: Plan | ||

| Step 4: | Conduct a needs assessment | An in-depth situation analysis of the educational system and the FP and CAC training needs. |

| Step 5: | Facilitate stakeholder dialogue | Involving stakeholders in a meaningful way, to ensure the programme and curriculum meet community needs, to create collegiality between those in health practice and health education, and to develop a sense of community “ownership”. |

| Step 6: | Confirm resource availability | Competency-based education (CBE) requires a specific set of human resources, space/infrastructure, technology, facilities, and learning environments and experiences. |

| In Phases 3, 4 and 5, we develop the curriculum | ||

| Phase 3: Construct | ||

| Step 7: | Adapt and adopt competencies | Choose FP and CAC competencies to be developed at each stage of the programme and curriculum, and adapt their wording so they precisely describe what context-specific competencies (attitudes, skills and knowledge, applied in practice) the programme and curriculum will develop. |

| Step 8: | Determine expected level of proficiency | The level of proficiency at which each competency is expected to be performed once the specified stage of the programme or curriculum is completed. |

| Step 9: | Create learning objectives | Learning objectives provide an educational roadmap to guide both the educator and the learner. They tell learners what they need to learn and provide educators a means of prioritising and structuring content. |

| Step 10: | Determine learning methods | Instructional methods to achieve learning objectives. |

| Phase 4: Sequence | ||

| Step 11: | Structure curriculum content | A detailed curriculum plan is needed to structure the content and its teaching across the duration of study. |

| Step 12: | Allocate time and resources | Operationalizing a curriculum requires specifying the time and materials required for each course and each learner. The time allocated should reflect the subject’s complexity and its contribution to programme and curriculum learning outcomes. |

| Phase 5: Assess | ||

| Step 13: | Create assessments | CBE involves carefully aligning competency-based assessment methods with the learning objectives in a curriculum plan. |

| Step 14: | Determine thresholds for progression or completion | Deciding what a learner needs to achieve before progressing to the next stage, and before successfully completing the programme. |

| In Phase 6, we implement | ||

| Phase 6: Implement | ||

| Step 15: | Build capacity to implement | CBE requires investment in institutional capacity, including strong administrative systems and staff, and educators who are equipped to teach the curriculum and assess learning achievements. |

| Step 16: | Evaluate programme and curriculum | Regular evaluation and revision are good practices for all programmes and curricula. They may also be mandatory steps in accreditation processes. |

CAC, comprehensive abortion care; CBE, competency-based education; FP, family planning.

Throughout the Educational Design Model are signposts for relevant instruments to support the appropriate implementation of a specific step. These include sample questionnaires, detailed overviews, templates and checklists among other supportive tools to guide the user through the Educational Design Model towards complete integration of the FP and CAC competencies into effective curricula for healthcare workers.27

Conclusion

As a reference for standardisation, the FP and CAC Toolkit enables efficient collaboration across organisations and countries and provides a shared language for the competencies required for quality FP and CAC service delivery. This resource represents an important advancement towards strengthening FP and CAC services in primary healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Laurence Codjia, Pascal Zurn, Nigel Lloyd and Marta Jacyniuk-Lloyd for their technical support and advice in developing the FP and CAC Toolkit.

Footnotes

Twitter: @EmboMieke, @bganatra

Funding: This study was funded by UNDP–UNFPA–UNICEF–WHO–World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, a cosponsored programme executed by the WHO.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the WHO.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, et al. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Forum Report. Recife, Brazil. Geneva: Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Souza P, Bailey JV, Stephenson J, et al. Factors influencing contraception choice and use globally: a synthesis of systematic reviews. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2022;27:364–72. 10.1080/13625187.2022.2096215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress – sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher-lancet Commission. The Lancet 2018;391:2642–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subasinghe AK, Deb S, Mazza D. Primary care provider’s knowledge, attitudes and practices of medical abortion: a systematic review. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2021;47:9–16. 10.1136/bmjsrh-2019-200487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beasley AD, Olatunde A, Cahill EP, et al. New gaps and urgent needs in graduate medical education and training in abortion. Acad Med 2023;98:436–9. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson EM, Cowan SK, Higgins JA, et al. Willing but unable: physicians’ referral knowledge as barriers to abortion care. SSM Popul Health 2022;17:101002. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.101002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assefa EM. Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of health providers towards safe abortion provision in Addis Ababa health centers. BMC Womens Health 2019;19:138. 10.1186/s12905-019-0835-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinthuchai N, Rothmanee P, Meevasana V, et al. Survey of knowledge and attitude regarding induced abortion among nurses in a tertiary hospital in Thailand after amendment of the abortion act: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2022;22:454. 10.1186/s12905-022-02064-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uaamnuichai S, Chuchot R, Phutrakool P, et al. Knowledge, moral attitude and practice of nursing students toward abortion. INQUIRY 2023;60:004695802311639. 10.1177/00469580231163994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French V, Steinauer J. Sexual and reproductive health teaching in undergraduate medical education: A narrative review. Intl J Gynecology & Obste 2023;00:1–8. 10.1002/ijgo.14759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ipas and the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations . Most medical students want training in abortion care—but schools don’t provide it. 2020. Available: www.ipas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/MEDTRG-E20.pdf

- 13.International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) . Joint statement of support for the inclusion of contraception and abortion in sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing education for all medical students. n.d. Available: https://www.figo.org/resources/figo-statements/joint-statement-support-inclusion-contraception-abortion-srhr-education

- 14.Hepburn JS, Mohamed IS, Ekman B, et al. Review of the inclusion of SRHR interventions in essential packages of health services in Low- and lower-middle income countries. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2021;29:1985826. 10.1080/26410397.2021.1985826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endler M, Al-Haidari T, Benedetto C, et al. Are sexual and reproductive health and rights taught in medical school? results from a global survey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2022;159:735–42. 10.1002/ijgo.14339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soin KS, Yeh PT, Gaffield ME, et al. Health workers' values and preferences regarding contraceptive methods globally: A systematic review. Contraception 2022;111:61–70. 10.1016/j.contraception.2022.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehnström Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, et al. Health care providers' perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health 2015;15:139. 10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradfield Z, Officer K, Barnes C, et al. Sexual and reproductive health education: midwives' confidence and practices. Women Birth 2022;35:360–6. 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner KL, Pearson E, George A, et al. Values clarification workshops to improve abortion knowledge, attitudes and intentions: a pre-post assessment in 12 countries. Reprod Health 2018;15:40. 10.1186/s12978-018-0480-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . Global Competency and Outcomes Framework for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, et al. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to Competencies. Acad Med 2002;77:361–7. 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank JR, Mungroo R, Ahmad Y, et al. Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach 2010;32:631–7. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ILO Regional office for Asia and the Pacific . Regional SKILLS and Employability Programme in Asia and the Pacific (SKILLS-AP). Making full use of competency standards: a handbook fir governments, employers, workers, and training organizations. Bangkok: ILO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . Sexual and reproductive health core Competencies in primary care: attitudes, knowledge, ethics, human rights, leadership, management, teamwork, community work, education, counselling, clinical settings. World Health Organization; 2011. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44507 [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . Family planning and comprehensive abortion care Toolkit for the primary health care workforce volume 1.Competencies. Geneva. World Health Organization; 2022. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063884 [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . Family planning and comprehensive abortion care Toolkit for the primary health care workforce. volume 2. programme and curriculum development guide.Geneva. World Health Organization; 2022. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063907 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wegs C, Turner K, Randall-David B. Effective training in reproductive health: course design and delivery. Retrieved from Chapel Hill, NC; 2011. Available: https://ipas.azureedge.net/files/EFFREFE12-EffectiveTraininginReproductiveHealthRef.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization . Abortion care guideline. license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. World Health Organization; 2022. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/349316 [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs . Family planning: a global Handbook for providers: evidence-based guidance developed through worldwide collaboration. license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. In: World Health Organization. 2018. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260156 [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization . Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, fifth edition 2015: executive summary. World Health Organization 2015. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/172915 [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization . Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use. In:. 3rd ed. World Health Organization, 2016. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252267 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.