Abstract

When mands and problem behavior co-occur within an individual’s repertoire, a functional analysis of precurrent contingencies helps to identify any relation between the two responses, as well as the function of problem behavior. Repetitive behaviors may function similarly to mands and also co-occur with problem behavior; particularly when repetitive behavior is blocked, or when caregivers refrain from participating in repetitive behavior episodes (e.g., the repetitive behavior involves a verbal or physical interaction with a caregiver). The current study presents assessment and treatment results for two participants diagnosed with autism, who demonstrated repetitive speech and problem behavior. Informal observations suggested that problem behavior occurred when an adult failed to emit a specific response to the participant’s repetitive speech. Functional analysis results confirmed the informal observations and suggested that problem behavior functioned as a precurrent response to increase the probability of reinforcement for repetitive speech. We report treatment results and discuss the application of precurrent contingency analyses for problem behavior and repetitive behavior.

Keywords: Functional analysis, Problem behavior, Precurrent contingency, Repetitive behavior

Individualized functional analysis (FA) conditions are sometimes necessary when more traditional test conditions (e.g., attention, demand, tangible, and alone; Iwata et al., 1994b) produce unremarkable results (Rooker et al., 2015; Schlichenmeyer et al., 2013). For example, after initial inconclusive FA results for two children, Bowman et al. (1997) conducted observations on their living unit and observed problem behavior when others failed to comply with their requests. Bowman et al. designed an FA test condition termed a mands analysis wherein adults denied mand compliance to evoke problem behavior. Subsequent to problem behavior, adults complied with mands for 30 s. In the control condition, all participant mands were reinforced (when possible) on a continuous schedule of reinforcement. Results from the FA indicated elevated rates of problem behavior in the test condition and minimal to zero rates of problem behavior in the control condition. These findings suggested that problem behavior functioned to increase the probability of mand compliance (Bowman et al., 1997).

Bowman et al. (1997) and Fisher (2001) concluded that the mands analysis isolated a precurrent and current response relation within a precurrent contingency. Skinner (2014) described a response as precurrent when its effects influence the probability of reinforcement for a subsequent behavior. For example, reviewing a recipe for cookies (precurrent response) increases the likelihood of successfully baking a cookie (current response). With regard to the FA and treatment of problem behavior, Bowman et al. conceptualized the participant’s destructive behavior as a precurrent response that functioned to increase the likelihood of reinforcement in the form of adult compliance with a mand (current response). This probability altering function of problem behavior is observed when the schedule of reinforcement for mands in the mands analysis shifts from extinction to FR1 (during the reinforcement interval subsequent to problem behavior). In sum, the mands analysis represents an FA condition that isolates a precurrent contingency and identifies increased probability of mand compliance as the function of problem behavior.

Mand compliance has recently gained increased recognition as a contingency supporting problem behavior maintenance (e.g., Jeglum et al., 2020; Owen et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2017; Torres-Viso et al., 2018). Rajaraman and Hanley (2021) conducted a review of studies published between 1997 and 2020 that included a mands analysis. The authors identified 22 studies and 65 analyses that described an FA with a test condition similar to the mands analysis condition in Bowman et al. (1997). It is important to note that the analyses informed effective function-based treatments that decreased problem behavior and increased appropriate alternative behavior.

Most research on the FA of precurrent contingencies involves problem behavior and vocal-verbal mands (Ramajaran & Hanley, 2021). Fewer studies describe precurrent contingencies related to behaviors that are not conspicuous mands, but may function similarly as current responses in a precurrent relation with problem behavior. Jeglum et al. (2020) identified a mand compliance function for severe problem behavior demonstrated by a 12-year-old male. The authors reported observations of putative nonvocal mands in the form of signs, pointing, grabbing, and leading others to preferred items, which appeared to co-occur with problem behavior. A test-control FA confirmed the mand compliance function and informed an effective treatment. It is important to note that the study by Jeglum et al. demonstrated that mands in more conspicuous and conventional forms (Thomas et al., 2010) are not a necessary condition to hypothesize a potential mand compliance function. Related to this, Skinner (1957) asserted that although the form of verbal behavior may allow a listener to infer its function as a mand, formal characteristics alone are not sufficient for mand identification (p. 36). Although Jeglum et al. demonstrated one example of a mand compliance function with a unique mand topography, countless other forms of indistinct responses (e.g., movements, gestures, utterances, and other speech episodes) may function similarly to mands and relate to problem behavior within a precurrent contingency.

Hagopian and Toole (2009) described the case of a 10-year-old girl who demonstrated a repetitive behavior that the authors referred to as “body-tensing.” Body-tensing was recorded when teeth clenching accompanied body trembling, or shaking while the girl was lying down (p. 119). A multielement FA suggested that the behavior was likely maintained by automatic reinforcement. One collateral finding from the FA was that aggression was observed most often in conditions that included blocking of body tensing. The authors hypothesized that aggression might have functioned as a precurrent response. That is, aggression increased the probability of reinforcement in the form of escape from blocking and access to the current response, body tensing, which produced reinforcement directly through sensory stimulation (i.e., automatic reinforcement). Nonetheless, the hypothesized precurrent–current response relation between aggression and access to body tensing was not verified within an FA. Kuhn et al. (2009) implemented a blocking analysis to determine the relation between destructive behavior and blocked access to repetitive behavior for a 16-year-old boy. The participant demonstrated repetitive behavior in the form of throwing away objects indiscriminately, and problem behavior occurred when the boy was blocked from throwing objects away. In the blocking analysis, a control condition (A) phase was alternated with a test condition (B) phase in an ABAB reversal design. In the control condition therapists allowed uninterrupted throwing away of objects. In the test condition, therapists denied access to throwing objects away by blocking the attempts. Contingent on problem behavior, therapists allowed the participant to throw away objects. Results showed minimal to zero rates of problem behavior in the control condition and elevated rates of problem behavior in the test condition. Kuhn et al. suggested that the blocking analysis demonstrated a probable precurrent contingency between problem behavior and throwing away objects because problem behavior altered the probability of reinforcement in the form of free (unblocked) access to throwing away objects (p. 358). Overall, identification of other forms of vocal-verbal and nonvocal behaviors that may function as a current response related to problem behavior can help alert clinicians and researchers to a more diverse range of behaviors, and contexts wherein a precurrent contingency analysis can confirm problem behavior function.

In the current investigation, we report data from two cases that describe an FA of precurrent contingencies, and a derived treatment. For each case, we first hypothesized that the participant’s repetitive speech functioned similarly to a mand as a current response to produce a specific vocal response from adults. Further, we hypothesized that problem behavior functioned to increase the probability of reinforcement in the form of a related vocal response to repetitive speech. To investigate these two hypotheses, a test-control FA was designed for each participant using the procedures described by Bowman et al. (1997), further detailed by Fisher (2001), and Rajaraman and Hanley (2021). Then, we examined treatment components aimed at reducing problem behavior and thinning the schedule of reinforcement to promote treatment extension across various people and contexts. It is important to note that our findings are discussed in terms of extending an FA of precurrent contingencies from the relation between problem behavior and conspicuous mands, to the relation between problem behavior and behaviors that may not appear as conventional mands, but may function similarly.

Method

Participants and Setting

The two participants were admitted to an inpatient hospital unit for the assessment and treatment of severe problem behavior. Sandy was a 10-year-old Hispanic female with previous diagnoses of pica, hyperphagia, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and moderate intellectual disability (ID). Her primary topography of problem behavior was self-injurious behavior (SIB). Ryan was a 16-year-old white male with previous diagnoses of ASD, disruptive behavior disorder (not otherwise specified [NOS]), anxiety disorder (NOS), mood disorder (NOS), and mild ID. His primary topography of problem behavior was aggression. Both participants communicated in full sentences with a vocal-verbal repertoire, and reportedly engaged in repetitive speech indiscriminately across most contexts.

All sessions were conducted in a 4.4 m x 4.8 m room with two chairs, a small sofa, and an observation window for therapists to conduct unobtrusive observation of FA and treatment evaluation sessions. Therapists with advanced training and practice in FA and derived treatment procedures conducted all sessions and data collection.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Trained observers recorded each participant’s problem behaviors and repetitive speech on laptop computers. Frequency data on problem behavior, which was converted to rate (responses per minute, or RPM), was collected for both participants. SIB (Sandy) was defined as hitting the head, face, or body with an open or closed hand from 6 in or more, self-pinching, self- biting, self-scratching, self-kicking, hitting wrist forcefully to a surface, and forcefully banging knees together. Aggression (Ryan) was defined as any instance of hitting or kicking others from 6 in or more, scratching, pinching, pulling hair, grabbing, biting, or throwing objects within 2 feet of another person. Repetitive speech was defined as any previously identified statement that was repeated more than once within a session and was unrelated to the current context. Some examples of repetitive speech included “First breakfast, then team, then bath, then bed” (Sandy), or “Are you happy?” (Ryan). Of note, if a listener attempted to redirect the conversation, did not provide any response, or provided a response that was unrelated to the topic of repetitive speech, problem behavior was likely to occur.

A second observer collected data simultaneously, but independently, during 57% of all FA and treatment evaluation sessions for Sandy, and 19% of all FA and treatment evaluation sessions for Ryan. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated using partial interval agreement. Each observation was divided into 10-s intervals, and the smaller number of responses recorded for each interval was divided by the larger number and multiplied by 100% to calculate a percentage agreement. Mean IOA for SIB and repetitive speech for Sandy was 99.12% (range: 95%–100%) and 81.20% (range: 58.06%–95.22%), respectively. For Ryan, mean IOA was 99.67% (range: 96.67%–100%) for aggression, and 94.11% (range: 87.50%–100%) for repetitive speech.

Functional Analysis of Precurrent Contingencies

Prior to the FA of precurrent contingencies, a multielement FA was conducted using procedures described by Iwata et al. (1982/1994a). Multielement FA results were unremarkable for both participants (data available from the first author), which led the behavior therapy teams to conduct further indirect and descriptive assessment. Follow-up assessment included re-review of records, semi-structured interviews with caregivers (parents, teachers, and clinical staff members), and direct observations conducted by clinical staff. Indirect and descriptive assessments indicated that both children often demonstrated repetitive speech that evoked a specific response related to the repetitive speech from caregivers. Caregivers reported that, in the past, failure to respond to repetitive speech, or attempting to redirect to another topic without answering, evoked problem behavior. Problem behavior cessation occurred after the caregiver participated in the repetitive speech episode by responding and attempting to deliver a preferred response. That is, problem behavior was observed when an adult failed to emit a specific response related to the repetitive speech episode. Over time, caregivers emitted a response related to the repetitive speech episode to avoid escalation to problem behavior.

An FA of precurrent contingencies was conducted with each participant to identify the hypothesized precurrent contingency between repetitive speech and problem behavior. Prior to initiating the FA, examples of each participant’s repetitive speech and examples of related responses were gathered from caregivers and staff that were familiar with each participant. Examples were reviewed with behavior therapy team members and data collectors. FA sessions for Sandy were 5 min, whereas sessions for Ryan were 10 min in duration. Test and control conditions were implemented within a multielement design.

Test

During the test condition, a therapist was present in the room with the participant, stood approximately 2–3 feet away, and did not provide any attention. Contingent upon each occurrence of repetitive speech, the therapist responded by redirecting the participant to another topic, responding in a manner inconsistent with the preferred response (e.g., “Let’s talk about something else/we’re going to talk about something else,” “I’m not sure,” “I don’t know”). Contingent upon problem behavior, the therapist responded more specifically to the participant’s repetitive speech, and provided any known preferred responses (e.g. “Yes, I am very happy, Ryan,” “Yes Sandy, first breakfast, then team, then bath, then bed”). Responses to repetitive speech continued for 30 s.

Control

During the control condition, the therapist was present in the room with the participant, stood approximately 2–3 feet away, and did not provide any attention. Contingent upon each instance of repetitive speech, the therapist responded immediately, and in particular, to the repetitive speech. Attention was withheld and no differential consequences were provided for problem behavior.

Treatment Evaluation

An ABAB reversal design was used to evaluate the effects of treatment for each participant’s repetitive speech and problem behavior. Treatment sessions were conducted with the same stimulus conditions as the FA. Treatment components included use of schedule-correlated stimuli arranged within a multiple schedule, differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA), response interruption and redirection (RIRD), and extinction. The practicality of the treatment was enhanced with schedule thinning, and an extension of the treatment effects was demonstrated by introducing treatment across a variety of novel contexts and staff. Session durations throughout the entire treatment evaluation (i.e. treatment and return to baseline phases) were initially 10 min in duration; however, session duration was extended to 20 and later 30 min for Sandy. The procedures for each condition are described below.

Baseline

The first baseline phase of the treatment evaluation for both participants was borrowed from the test condition sessions of the FA to increase efficiency of the evaluation (Scheithauer et al., 2020). Sessions in the second baseline phase followed identical procedures to those described for the test condition of the FA.

Treatment

Two schedule-correlated stimuli (i.e. green and red laminated cards with “Sandy’s Way” or “Ryan’s Way” on the green card (SD), and “Therapist’s Way” on the red card (S∆), attached to a lanyard worn by the therapist) were arranged within a multiple schedule. DRA + extinction contingencies were correlated with the SD. Therefore, the green card signaled that repetitive speech would produce a related response from therapists and, contingent on problem behavior, a response related to repetitive speech would be withheld (i.e., extinction). When the green card was shown to the participant, the therapist vocally stated, “Ok, it’s (Sandy’s Way or Ryan’s Way), we can talk about whatever you want.” During this time, the therapist remained seated in a chair approximately 2–3 feet away from the participant. The therapist provided a response to each instance of the participant’s repetitive speech. That is, an FR1 schedule of reinforcement for repetitive speech was operative during the green signaled component of the multiple schedule.

After each participant demonstrated low and stable rates of problem behavior (i.e., three consecutive sessions at or below an 80% reduction from the average initial baseline rate), when repetitive speech was reinforced on an FR1 schedule, schedule-thinning was initiated by fading-in intervals with contingencies correlated with the S∆ (red card signaling implementation of RIRD + extinction). For example, when the red card was shown to the participant, the therapist vocally stated, “It is my way. Remember, during my way we’ll talk about stuff like the weather, what you have done today, cool things you have seen, or what you are going to do this weekend.” After the therapist showed the participant the card and vocally stated the rule, the therapist positioned themselves approximately 2–3 feet away from the participant in a chair. Contingent on the participant’s repetitive speech, the therapist implemented RIRD by providing a redirective statement such as “I already answered that” or “we’re not going to talk about that,” and then resumed discussing another topic that was not associated with the repetitive speech. Extinction continued to be programmed for problem behavior during the S∆. For Sandy, an initial 1-min S∆ interval was introduced during the first treatment phase. After the return to baseline and then reinstatement of treatment contingencies with the 1-min S∆ interval, a 9 min 30 s S∆ probe was implemented during session 12 to derive an appropriate S∆ duration to inform schedule thinning. Rates of problem behavior during the probe session remained at a clinically significant reduction. Therefore, the S∆ component of the multiple schedule remained active at 9 min 30 s during subsequent treatment sessions. Sessions were later extended to 20 min and finally, 30 min sessions. During Ryan’s treatment, evaluation the initial S∆ component was introduced for 30 s at the beginning of a 10-min session in the first treatment phase, with the SD component active for the remaining 9 min 30s. After a reversal to baseline and then reinstatement of treatment contingencies with a 30s S∆, additional schedule-thinning steps were implemented by increasing the S∆ to the following intervals: 1 min, 2 min, 3 min, 5 min, 7 min, and 9 min. The terminal goal for Ryan was to maintain low rates of problem behavior with a 9-min S∆ followed by a 1-min SD in a 10-min session.

Treatment Extension

Following the completion of schedule thinning for each participant, the behavior therapy teams initiated programming for the extension of treatment effects across novel therapists and contexts. At first for Sandy, the treatment was incorporated into her daily activities when the total session duration was extended to 30 min. These activities included a set schedule that rotated through 10-min intervals of interactive play, independent play, and academic work. During interactive play a bin of toys, including play food, puzzles, and balls was available for Sandy as a source of environmental enrichment. The therapist engaged in the activity with Sandy if she independently and appropriately solicited attention or help from the therapist. During independent play, the S∆ component was active throughout the entire duration of the activity. In addition, a bin of toys that included dolls, watercolor painting books, and a Magna Doodle ®, was available for Sandy to freely access. During academic work, Sandy was seated at a desk and presented with academic tasks. For the first minute of the academic interval, the SD component was active, and the S∆ was active for the subsequent 9 min. Following the extension of treatment effects to Sandy’s daily routine, novel therapists were systematically incorporated.

Ryan’s treatment was systematically introduced across novel staff who served as therapists within the session. Following the addition of novel therapists, the multiple schedule was integrated into an independent leisure interval. That is, during “Ryan’s Way,” he was provided with moderately preferred toys, empirically identified via a paired stimulus preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992), while the therapist engaged in a “busy” activity such as reading a magazine or completing paperwork. This was done to mimic specific situations at home in which a caregiver may be otherwise occupied and serve as a more salient visual stimulus within the environment that the availability of reinforcement for repetitive speech was unavailable (i.e., promote the generalization of treatment by transferring stimulus control to more naturally occurring stimuli within the environment).

Results

Results of the FAs for each participant are presented in Fig. 1. Sandy’s FA indicated elevated rates of SIB on an increasing trend across three test condition sessions (M = 3.0 rpm) in comparison to the control condition (M = 0.07 rpm). Levels of repetitive speech were undifferentiated across both test and control conditions (M = 7.0 rpm). During Ryan’s FA, variable but overall elevated rates of aggression were observed in the test condition (M = 0.63 rpm) in comparison to the control condition (M = 0.00 rpm). Similar to Sandy’s pattern of repetitive speech, Ryan also demonstrated repetitive speech at elevated and undifferentiated rates across both test (M = 3.28 rpm) and control (M = 2.43 rpm) conditions. Overall, results from both participant’s FAs indicated that, in the test condition, therapist noncompliance with emitting a vocal response related to repetitive speech evoked participant problem behavior. Cessation of problem behavior was observed in the test condition for both children when the therapist provided a related response to repetitive speech (FR1 schedule of the related response subsequent to problem behavior). Minimal to no problem behavior was observed in the control conditions where each instance of repetitive speech produced a related vocal response from a therapist (FR1 schedule of the related vocal response contingent on repetitive speech). Therefore, these results suggest a probability altering function of problem behavior involving therapist compliance with emitting a vocal response to repetitive speech.

Fig. 1.

Functional Analysis Results for Sandy (Left Panels) and Ryan (Right Panels). Top panels depict responses per minute of self-injurious behavior (Sandy) and aggression (Ryan). Bottom panels depict responses per minute of repetitive speech

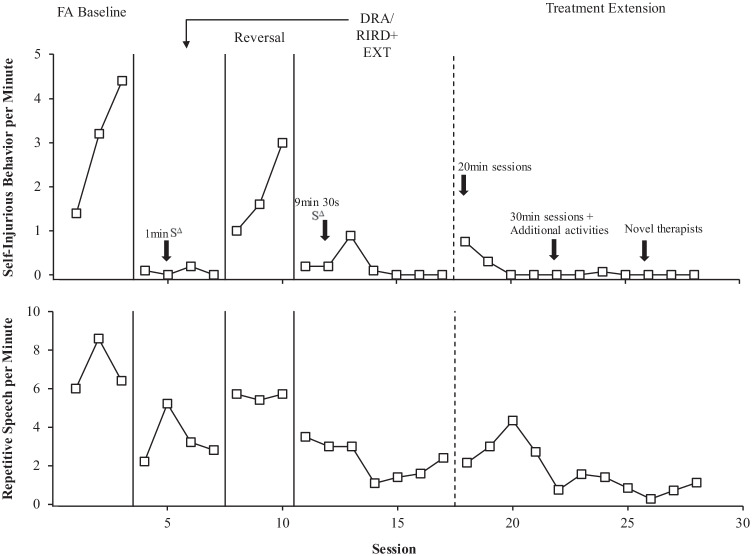

Results of the treatment evaluation for Sandy are presented in Fig. 2. Within the first treatment phase for Sandy, elevated rates of SIB were observed during both the first (M = 3.0 rpm) and second (M = 1.87 rpm) baseline phases. During the first treatment phase for Sandy, rates of SIB averaged 0.07 rpm. After the first treatment phase and a reinstatement of baseline contingencies, there was an immediate increase in SIB (M = 1.87 rpm). Once functional control was demonstrated during the reversal to baseline, the 1-min S∆ and 9-min SD schedule was replicated for 1 session, with SIB occurring at 0.2 rpm, before rapidly thinning the schedule to a 9.5-min S∆. Rates of SIB continued to remain minimal even following the extension of session duration to 20 min (M = 0.23 rpm). Extension of the treatment to novel contexts was initiated at session 22. SIB remained minimal as novel contexts and therapists were introduced.

Fig. 2.

Responses per Minute of Self-Injurious Behavior (Top Panel) and Repetitive Speech (Bottom Panel) during Sandy’s Treatment Evaluation

Sandy’s repetitive speech was elevated during baseline (M = 7.0 and 5.6 rpm). During the first treatment phase, Sandy’s repetitive speech was observed at decreased rates (M = 3.35) in comparison to the FA baseline (M = 7.00). Repetitive speech returned to higher rates when baseline contingencies were implemented for a three session reversal phase (M = 5.6 rpm), and then decreased once again after reinstating treatment and throughout schedule thinning (M = 2.28 rpm). Once treatment session duration was increased to 20 min, increased and variable rates of repetitive speech were observed, but rates remained overall lower than baseline. After increasing session duration to 30 min, incorporating daily scheduled activities, and generalizing the treatment across therapists, rates of repetitive speech remained even lower than previous treatment phases (M = 0.94).

Within the first treatment phase of Ryan’s treatment evaluation (Fig. 3), zero instances of aggression were observed across the entire phase. After the first treatment phase and a return to baseline contingencies, there was an immediate increase in aggression (M = 1.07 rpm). Following the reinstatement of treatment contingencies, the availability of reinforcement was systematically thinned by fading-in the S∆ from 30 s to 9 min of a 10-min session. Prior to the extension of treatment (sessions 19–42), there were few occurrences of aggression (M = 0.04 rpm). During extension of the treatment to novel therapists and contexts at sessions 43 and 49, respectively, the rate of aggression remained at zero, with the exception of one treatment session.

Fig. 3.

Responses per Minute of Aggression (Top Panel) and Repetitive Speech (Bottom Panel) during Ryan’s Treatment Evaluation. Open diamonds depict repetitive speech during the SD component and closed diamonds depict repetitive speech during the SΔ

Ryan’s rates of repetitive speech during the initial baseline and second baseline phases were elevated (M = 3.28 rpm and 3.13 rpm, respectively). Repetitive speech occurred at an average rate of 2.7 rpm during the first three sessions of the initial treatment phase with a continuous schedule of reinforcement for repetitive speech. Following the initial introduction of the S∆ interval, repetitive speech continued to occur at moderate and variable rates. When the schedule was thinned to an S∆ interval of 9 min, the average rate of repetitive speech decreased (M = 0.62 rpm). Data for Ryan’s repetitive speech were collected separately during the S∆ and SD intervals. Ryan engaged in stable rates of repetitive speech throughout the SD interval (M = 2.74 rpm), whereas the rate of repetitive speech within the S∆ interval was zero. Within the second treatment phase, repetitive speech during the SD interval was moderate and variable, even as that schedule component was thinned from 1 min to 5 min (M = 1.93 rpm); however, when the schedule was thinned to 7 min and 9 min, the average rate of repetitive speech decreased more substantially (M = 0.62 rpm). Rates of repetitive speech during the S∆ interval remained low to zero throughout the entirety of the second treatment phase. During extension of treatment across novel therapists and activities, the rate of repetitive speech was high with increased variability during the SD interval, whereas a similar pattern of low to zero responding was observed during the S∆ interval (average 2.62 rpm and 0.12 rpm, respectively).

Discussion

Similar to the procedures outlined by Bowman et al. (1997), development of the FA for repetitive speech and problem behavior relied on observations of the children’s interactions with staff and caregivers on an inpatient unit. Over time, staff learned to respond to the participant’s repetitive speech with a related response. Responding to the participant in a preferred manner allowed staff to avoid escalations to problem behavior. These observations led to the hypothesis that the participant’s problem behavior increased the likelihood of another’s specific vocal response related to repetitive speech. We developed a test condition within which a response to repetitive speech was withheld, which reliably evoked problem behavior for both participants. The response related to repetitive speech was delivered subsequent to problem behavior. In the control condition, where therapists delivered the preferred response contingent on each instance of repetitive speech, no problem behavior occurred. Results of the FA support the hypothesis that repetitive speech functioned similarly to a mand as the current response in a precurrent contingency with problem behavior. In addition, the FA results suggest that problem behavior likely functioned to increase the probability of compliance with providing a response related to repetitive speech. These findings parallel those described in previous studies on the relation between mands and problem behavior (e.g. Bowman et al., 1997; Eluri et al., 2016; Torres-Viso et al., 2018).

These results, along with those described by Jeglum et al. (2020), also suggest that a conspicuous or conventional mand is not a necessary feature to conduct an analysis similar to those described in this study. Rather, the essential feature is an a priori identification of a probable precurrent response (problem behavior) and a typically benign current response (e.g., mand, repetitive behavior) that evokes socially mediated reinforcement in the form of another person’s compliance (Fisher, 2001). Within a test-control FA, Fisher (2001) expounded that if problem behavior functions as a precurrent response to increase the likelihood of reinforcement for a current response, then the current response-problem behavior unit should occur at a consistent and elevated rate in the test condition. On the other hand, problem behavior should be minimal or absent in the control condition where the establishing operation related to the precurrent response is eliminated with an FR1 schedule of reinforcement. This response pattern across the test and control conditions meets Polson and Parson’s (1994, p. 428) requirement of a precurrent contingency due to the probability altering effect of problem behavior on mand compliance in the mands analysis or, in a similar way, problem behavior and caregiver responses to repetitive speech in the current study. That is, problem behavior produces a change in the schedule of reinforcement from extinction to FR1. The feature of a precurrent contingency that distinguishes the current–precurrent response unit from a behavior chain is that the current response (baking a cookie or manding for compliance) may produce reinforcement on its own; the precurrent response functions to alter the probability of reinforcement for the current response (Polson & Parsons, 1994). In addition, some precursor behaviors in the form of conventional or unconventional mands may also function as current responses in a precurrent relation with problem behavior (Heath & Smith, 2019; Fahmie & Iwata, 2011).

FA test and return to baseline conditions indicated an increasing trend and highly variable rates of problem behavior for Sandy and Ryan, respectively. A stable and efficient pattern of responding would be a more expected pattern with a fixed time duration for reinforcement delivery (Fisher, 2001, p. 179). This interpretive limitation could be minimized in future studies by examining within session data to determine if problem behavior occurred in a burst and then abated, or if it persisted during the reinforcement interval. Although the former does not compromise any support for a precurrent relation, the latter suggests that alternative sources of reinforcement for problem behavior may exist.

The intervention in the current study included DRA, extinction, and compound schedules of reinforcement to promote schedule thinning. These components are consistent with the literature on the treatment of problem behavior and precurrent contingencies related to mand compliance (Rajaraman & Hanley, 2021; Owen et al., 2020). Owen et al. (2020) reported successful implementation of compound schedules of reinforcement in the form of chained and multiple schedules as part of schedule thinning to enhance generality and practicality of treatments for mand compliance. Owen et al.’s larger scale report outlining schedule-thinning strategies adds a substantial layer of practical findings to the literature on treatment for problem behavior identified as part of a precurrent contingency (p. 16). In the current investigation, treatment evaluation began with DRA + extinction procedures, with reinforcement for repetitive speech occurring on a continuous schedule of reinforcement. Schedule thinning was initiated with a multiple schedule of DRA + extinction, and RIRD + extinction. Sandy’s multiple schedule included an alternating 9-min, 30-s S∆ interval alternating with 30 s of the SD component within a 30-min session. For Ryan, the S∆ interval was faded-in to a 9-min interval that alternated with 1 min of the SD component during a 10-min session. For both participants, the multiple schedules were incorporated into a daily schedule of activities with a more flexible implementation of the multiple schedule in natural contexts. For example, Sandy’s daily activity schedule included alternating periods of interactive and independent play. During the interactive play interval, the SD component was active since it would be appropriate to interact in a preferred manner. During the independent play interval, the S∆ component was active, signaling to Sandy that preferred responses to repetitive speech were unavailable.

Despite the prevalence of compound schedule use in the treatment of problem behavior, some literature suggests that high rates of the alternative response may continue with implementation of a multiple schedule (Hanley et al., 2001; Fisher et al., 2014). Excessive responding across components (SD and S∆) may interfere with discriminated responding and stimulus control over the alternative response. Demonstrating procedures that produce discriminated responding and stimulus control over problem behavior and alternative behavior seems critical for dissemination of procedures to transfer treatment effects across contexts and prevent relapse (Greer et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2020). The introduction of an S∆ interval in the current study included extinction for repetitive speech and problem behavior, as well as RIRD to interrupt repetitive speech and prompt compliance with a therapist directed interaction. Context-specific RIRD has been shown to decrease vocal stereotypy and increase contextually appropriate speech (Steinhauser et al., 2021). Therefore, RIRD was included during the S∆ to enhance extinction and promote contextually relevant speech as a replacement for repetitive speech. For Ryan, effectiveness of the multiple schedule was demonstrated by the minimal occurrences of repetitive speech observed during the S∆ interval in the latter stages of treatment. Ryan’s data indicate a rapid discrimination across the schedule components. Clinically, this was a notable outcome and indicated the effectiveness of the procedures. Unfortunately, because the specific cause for the nearly immediate discrimination is unclear, this may be considered a limitation in the procedures that should be explored in future investigations. An additional limitation is that data for repetitive speech across schedule components is exclusive to Ryan’s treatment evaluation. Repetitive speech data were not collected separately when each schedule component was active for Sandy. Sandy’s IOA data for repetitive speech were also low in some sessions. The low IOA was likely a result of the topography of Sandy’s repetitive speech. At times, Sandy’s repetitive speech occurred in the form of statements in rapid succession. Therefore, future investigations should include data collection procedures that capture responding across schedule components for all participants, as well as individualized measurement systems (e.g., partial interval rather than frequency) for behaviors such as repetitive speech, which pose challenges in detecting their onset and offset. Furthermore, monitoring the rate of any alternative speech may add further support to the benefits of the RIRD procedure.

Another limitation of the current study is the lack of data on differentiated responding across multiple schedule components prior to the introduction of RIRD. It is possible that the schedule correlated stimuli and associated contingencies were enough to produce stimulus control over responding across the multiple schedule components (i.e., DRA for appropriate behavior and extinction for problem behavior during the SD component and extinction for both responses during the S∆ component). Therefore, future researchers may consider introducing multiple schedule components without RIRD, measuring responding across components, and then systematically adding the RIRD component, if needed, in order to produce differentiated responding and alternative speech.

The results of this study suggest that a conspicuous mand is not a necessary feature to conduct an FA of precurrent contingencies related to problem behavior. The repetitive speech in the current study functioned similarly to a mand because it produced a highly specific form of interaction from a listener. From a broader clinical perspective, the repetitive speech may be categorized as an insistence on sameness (IS), higher order restricted repetitive behavior (Bishop et al., 2013). Thus, the FA of precurrent contingencies implemented in the current study suggests that the response–response relations in a precurrent contingency may play a role in maladaptive child and caregiver relations beyond excessive mands and problem behavior. Similar analyses conducted with more gross motor repetitive behaviors that also function similarly to mands, such as those described in Hagopian and Toole (2009), and Kuhn et al. (2009), may add to the generality of the procedures.

The absence of problem behavior in the control condition suggested that problem behavior could be avoided altogether if repetitive speech continued to be reinforced on a continuous schedule of reinforcement. From a clinical perspective, it is possible that many caregivers adopt the strategy of continuous reinforcement for repetitive behavior as a method to avoid problem behavior escalation. Moreover, the threat of problem behavior escalation may govern a caregiver’s hesitation to block a child’s repetitive opening and closing of doors, turning on and off of faucets and light switches or, as was the case in the current investigation, the caregiver’s participation in a stereotypic back-and-forth verbal exchange. Continuous reinforcement of child behavior is not practical for caregivers and requires intervention. Intervention is even more urgent when problem behavior occurs as a consequence for caregiver’s noncompliance with the dense schedule of reinforcement for child behavior. In the clinical psychology and psychiatry literature, avoidance of disruptive behavior through reinforcement and participation in repetitive behaviors is referred to as accommodation (Koller et al., 2021; Strohmeier et al., 2020). When accommodation is prevalent in a caregiver’s repertoire, problem behavior may occur at minimal rates and be difficult to detect. In the absence of a function-informed intervention, it is understandable that caregivers demonstrate accommodation as an avoidance-maintained response to prevent behavior escalation. Nonetheless, behavioral practitioners may be alerted to an opportunity for implementation of an FA of precurrent contingencies, and a derived intervention, when problem behavior is reported along with the observation of caregivers allowing unrestricted, and maladaptive, child engagement in repetitive behaviors, or caregiver participation in the repetitive behavior episode.

The procedures outlined in this investigation are not proposed as a new variant of FA. Rather, the current study suggests that an FA may be one context for revealing precurrent contingencies related to problem behavior. The FA of precurrent contingency procedures may be relevant whether the current response that produces reinforcement is in the form of a mand, repetitive behavior, or any other response that is reinforced at excessive rates in order to avoid problem behavior escalation.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures described herein involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards and IRB guidelines of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of all participants.

Consent for Publication

No personal identifiable information has been included within this study.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

• A functional analysis of precurrent contingencies can help identify a probability altering function of problem behavior.

• Precurrent contingencies may support the relation between problem behavior and caregiver involvement in repetitive speech.

• Treatment involving compound schedules of reinforcement can reduce problem behavior that functions to increase probability of reinforcement related to repetitive speech.

• Clinicians may consider a functional analysis of precurrent contingencies when caregivers demonstrate avoidance-maintained accommodation of repetitive behaviors.

This research was conducted at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Neurobehavioral Unit, Baltimore, Maryland.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bishop SL, Hus V, Duncan A, Huerta M, Gotham K, Pickles A, Kreiger A, Buja A, Lund S, Lord C. Subcategories of restricted and repetitive behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(6):1287–1297. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1671-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman LG, Fisher WW, Thompson RH, Piazza CC. On the relation of mands and the function of destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30(2):251–265. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eluri Z, Andrade I, Trevino N, Mahmoud E. Assessment and treatment of problem behavior maintained by mand compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49(2):383–387. doi: 10.1002/jaba.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmie TA, Iwata BA. Topographical and functional properties of precursors to severe problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44(4):993–997. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(2):491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW. Functional analysis of precurrent contingencies between mands and destructive behavior. Behavior Analyst Today. 2001;2(3):176. doi: 10.1037/h0099937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Greer BD, Querim AC, DeRosa N. Decreasing excessive functional communication responses while treating destructive behavior using response restriction. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35(11):2614–2623. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Fuhrman AM, Greer BD, Mitteer DR, Piazza CC. Mitigating resurgence of destructive behavior using the discriminative stimuli of a multiple schedule. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2020;113(1):263–277. doi: 10.1002/jeab.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer BD, Fisher WW, Briggs AM, Lichtblau KR, Phillips LA, Mitteer DR. Using schedule-correlated stimuli during functional communication training to promote the rapid transfer of treatment effects. Behavioral Development. 2019;24(2):100. doi: 10.1037/bdb0000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Toole LM. Effects of response blocking and competing stimuli on stereotypic behavior. Behavioral Interventions: Theory & Practice in Residential & Community-Based Clinical Programs. 2009;24(2):117–125. doi: 10.1002/bin.278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, Thompson RH. Reinforcement schedule thinning following treatment with functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34(1):17–38. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath H, Jr, Smith RG. Precursor behavior and functional analysis: A brief review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52(3):804–810. doi: 10.1002/jaba.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K.E., & Richman, G. S. (1994a). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 197–209. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Iwata BA, Pace GM, Dorsey MF, Zarcone JR, Vollmer TR, Smith RG, Rodgers TA, Lerman DC, Shore BA, Willis KD. The functions of self-injurious behavior: An experimental-epidemiological analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27(2):215–240. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeglum S, Schmidt JD, Hallgren M, Vetter J, Goetzel A. Assessment and treatment of challenging behavior maintained by a nonvocal mands function. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13(4):972–977. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00486-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller, J., David, T., Bar, N., & Lebowitz, E. R. (2021). The role of family accommodation of RRBs in disruptive behavior among children with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders 49(9), 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kuhn DE, Hardesty SL, Sweeney NM. Assessment and treatment of excessive straightening and destructive behavior in an adolescent diagnosed with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42(2):355–360. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen TM, Fisher WW, Akers JS, Sullivan WE, Falcomata TS, Greer BD, Roane HS, Zangrillo AN. Treating destructive behavior reinforced by increased caregiver compliance with the participant's mands. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(3):1494–1513. doi: 10.1002/jaba.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson DA, Parsons JA. Precurrent contingencies: Behavior reinforced by altering reinforcement probability for other behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1994;61(3):427–439. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1994.61-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman A, Hanley GP. Mand compliance as a contingency controlling problem behavior: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54(1):103–121. doi: 10.1002/jaba.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooker GW, DeLeon IG, Borrero CS, Frank-Crawford MA, Roscoe EM. Reducing ambiguity in the functional assessment of problem behavior. Behavioral Interventions. 2015;30(1):1–35. doi: 10.1002/bin.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheithauer M, Schebell SM, Mevers JL, Martin CP, Noell G, Suiter KC, Call NA. A comparison of sources of baseline data for treatments of problem behavior following a functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(1):102–120. doi: 10.1002/jaba.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichenmeyer KJ, Roscoe EM, Rooker GW, Wheeler EE, Dube WV. Idiosyncratic variables that affect functional analysis outcomes: A review (2001–2010) Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46(1):339–348. doi: 10.1002/jaba.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JD, Bednar MK, Willse LV, Goetzel AL, Concepcion A, Pincus SM, Hardesty SL, Bowman LG. Evaluating treatments for functionally equivalent problem behavior maintained by adult compliance with mands during interactive play. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2017;26(2):169–187. doi: 10.1007/s10864-016-9264-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (2014). Contingencies of reinforcement. Atheorical analysis. (Vol. 3). BF Skinner Foundation. (Original work published 1969).

- Steinhauser HM, Ahearn WH, Foster RA, Jacobs M, Doggett CG, Goad MS. Examining stereotypy in naturalistic contexts: Differential reinforcement and context-specific redirection. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54(4):1420–1436. doi: 10.1002/jaba.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier CW, Schmidt JD, Furlow CM. Family accommodation and severe problem behavior: Considering family-based interventions to expand function-based treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020;59(8):914–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BR, Lafasakis M, Sturmey P. The effects of prompting, fading, and differential reinforcement on vocal mands in non-verbal preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Behavioral Interventions: Theory & Practice in Residential & Community-Based Clinical Programs. 2010;25(2):157–168. doi: 10.1002/bin.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Viso M, Strohmeier CW, Zarcone JR. Functional analysis and treatment of problem behavior related to mands for rearrangement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2018;51(1):158–165. doi: 10.1002/jaba.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]