Abstract

Background

The traditional cultural food practices of Indigenous people and adults from racial/ethnic minority groups may be eroded in the current food system where nutrient-poor and ultra-processed foods (UPF) are the most affordable and normative options, and where experiences of racism may promote unhealthy dietary patterns. We quantified absolute and relative gaps in diet quality and UPF intake of a nationally representative sample of adults in Canada by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity, and trends between 2004 and 2015.

Methods

Adults (≥18 years) in the Canadian Community Health Survey-Nutrition self-reported Indigenous status and race/ethnicity and completed a 24-h dietary recall in 2004 (n = 20,880) or 2015 (n = 13,970) to calculate Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) scores from 0 to 100 and proportion of energy from UPF. Absolute and relative dietary gaps were quantified for Indigenous people and six racial/ethnic minority groups relative to White adults and trends between 2004 and 2015.

Results

Adults from all six racial/ethnic minority groups had higher mean HEI-2015 scores (58.7–61.9) than White (56.3) and Indigenous adults (51.9), and lower mean UPF intake (31.0%–41.0%) than White (45.9%) and Indigenous adults (51.9%) in 2015. As a result, absolute gaps in diet quality were positive and gaps in UPF intake were negative among racial/ethnic minority groups—indicating more favourable intakes—while the reverse was found among Indigenous adults. Relative dietary gaps were small. Absolute and relative dietary gaps remained largely stable.

Conclusions

Adults from six racial/ethnic minority groups had higher diet quality and lower UPF intake, whereas Indigenous adults had poorer diet quality and higher UPF intake compared to White adults between 2004 and 2015. Absolute and relative dietary gaps remained largely stable. Findings suggest racial/ethnic minority groups may have retained some healthful aspects of their traditional cultural food practices while highlighting persistent dietary inequities that affect Canada's Indigenous people.

Keywords: Indigenous status, Race, Ethnicity, Diet quality, Ultra-processed food, Adults

Highlights

-

•

Adults from six ethnic minority groups had higher diet quality and lower intake of ultra-processed foods than White adults.

-

•

Indigenous adults had poorer diet quality and higher intake of ultra-processed foods than White adults.

-

•

Absolute and relative dietary gaps remained largely stable over time.

-

•

Broader social structures may buffer the negative effects of racism on the diets of adults from ethnic minority groups.

-

•

Dietary inequities persist among Canada's Indigenous peoples.

1. Introduction

The diet quality of adults in Canada and the United States (US) is poor and intake of ultra-processed foods (UPF) is high (Juul et al., 2022; Moubarac et al., 2017; Olstad et al., 2021; Shan et al., 2019). This is a concern because diet quality and UPF intake are independently associated with increased risk of chronic disease and poor mental health (Brlek & Gregoric, 2022; Lane et al., 2021, 2022). Indigenous adults and adults from racial/ethnic minority groups often have rich cultural food practices founded on consumption of whole foods eaten in communal settings. Many of these practices incorporate nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, grains and protein-based foods. However, these traditional food practices may be eroded in the current food system where nutrient-poor and ultra-processed foods are often the most affordable and normative options, and where experiences of racism may promote unhealthy patterns of consumption.

Racism is a system whereby society ranks individuals based on nationality, phenotypic or ethnic markers of difference, and differentially distributes power, prestige and resources among these groups (Williams et al., 2019). Racism can be experienced in many forms, including internalized, inter-personal, cultural and structural (Williams et al., 2019). However, no matter the form, experiences of racism have been consistently associated with poorer dietary patterns among adults from racial/ethnic minority groups (Rodrigues et al., 2022). Two principal pathways are posited to explain these associations (Rodrigues et al., 2022). First, experiences of racism constrain access to material and social resources that can support maintenance of traditional cultural food practices, such as high-quality jobs, adequate income, stable housing and healthy food environments. Second, racism is a potent source of psychosocial stress which alters satiety mechanisms and promotes overconsumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor and ultra-processed ‘comfort’ foods as a coping mechanism. While the impact of racism on the dietary patterns of Indigenous people has yet to be studied, it is reasonable to expect that experiences of racism may negatively affect their dietary patterns through similar pathways. Moreover, historical and ongoing colonialist practices which have devalued Indigenous ways of being and knowing, displaced Indigenous people from their traditional lands, and limited their opportunities for self-determination may further negatively affect their traditional cultural food practices (Adelson, 2005).

Although experiences of racism have been associated with poorer dietary patterns among individuals from racial/ethnic minority groups (Rodrigues et al., 2022), the dietary patterns of racialized adults are not invariably poorer than those of White adults. For instance, although Black adults in the US consistently have poorer diet quality and higher UPF intake than White adults, Asian adults have higher diet quality than White adults (Juul et al., 2022; Patetta et al., 2019; Rehm et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2019; Tao et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2014, 2015). Estimates among Mexican American/Hispanic and ‘Other’ adults are more variable, with evidence of poorer, similar and even more favourable dietary patterns than White adults. These data may suggest that other social structures partially buffer some of the negative effects of racism on the traditional cultural food practices of adults from some racial/ethnic minority groups. By contrast, Indigenous people do not appear to experience such buffering effects, as they have poorer diet quality and higher UPF intake than non-Indigenous adults in Canada (Batal et al., 2018; Riediger et al., 2022). A better understanding of the patterning of dietary intake by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity, and the evolution of these trends over time, can help to identify adults who require greater support to maintain their traditional cultural food practices.

A small number of nationally representative studies have examined differences and trends in diet quality and UPF intake by race/ethnicity in the US (Juul et al., 2022; Patetta et al., 2019; Rehm et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2019; Tao et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2014, 2015). However, prior studies provided data for just 3–4 racial/ethnic groups and did not quantify intakes among Indigenous people, thereby precluding a more comprehensive accounting of the dietary patterns of adults from multiple cultural groups and trends over time. Moreover, previous studies did not quantify absolute or relative dietary gaps or trends in these gaps. It may be particularly valuable to examine trends in inequities in diet quality and UPF intake by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity in Canada given that many of the structural aspects of Canadian society resemble those in the US (e.g., high-income Liberal democracies, White European ancestry populations, large immigrant populations) whereas others differ markedly (e.g., Canada has an official policy of multiculturalism, has much lower income inequality and provides universal health care). In addition to providing vital nationally representative data for Canada, such studies can enable informal cross-national comparisons that can help to generate hypotheses regarding structural supports that can assist Indigenous and racialized adults to maintain their traditional cultural food practices over time. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to quantify absolute and relative gaps in the diet quality and UPF intake of a nationally representative sample of adults in Canada according to Indigenous status and race/ethnicity, and trends in these gaps between 2004 and 2015.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study used nationally representative, cross-sectional data from the two most recent cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey-Nutrition (CCHS–N) collected in 2004 and 2015 by Statistics Canada (Health Canada, 2006; Statistics Canada, 2017). The CCHS–N collected detailed information on the dietary intake of individuals living in Canada, along with sociodemographic and health-related information. The surveys were designed to be comparable to enable direct comparisons of dietary intake over time, and thus except where indicated, consistent methods were used in both years. The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary deemed this study exempt from ethical approval because it involved analysis of surveys conducted by Statistics Canada.

2.2. Participants and sampling

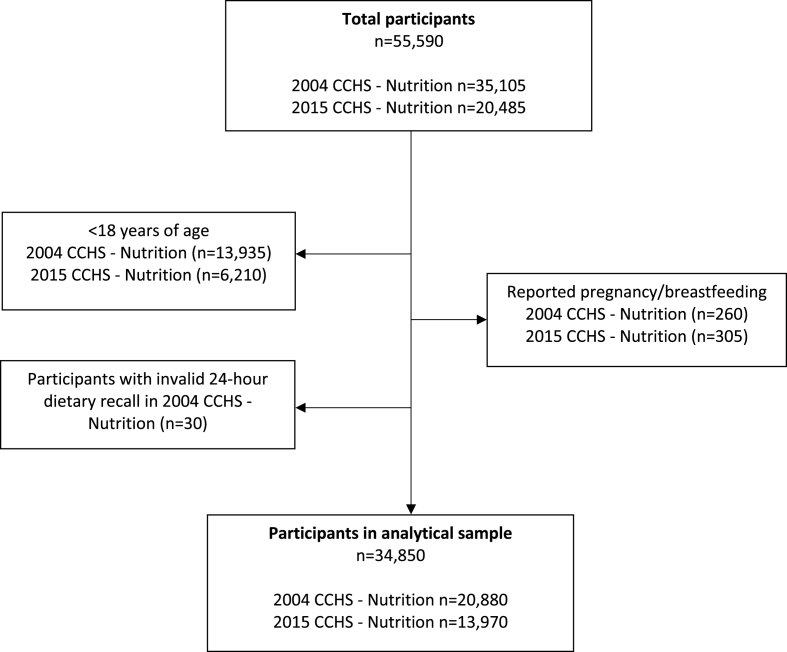

The CCHS–N sampled private dwellings in rural and urban locations in all ten Canadian provinces using multi-stage, stratified, clustered and probabilistic sampling procedures. The surveys captured 98% of the population, excluding individuals in the Canadian Forces and those living in Canada's three northern territories, in institutional settings or on Indigenous reserves. The response rate was 77% in 2004 and 62% in 2015. The current study included data from 34,850 adults ≥18 years of age (n = 20,880 in 2004; n = 13,970 in 2015) who did not report pregnancy/breastfeeding and who provided valid 24-h dietary recall data as determined by Statistics Canada (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant flowchart for the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) – Nutrition 2004 and 2015 (unweighted data).

2.3. Data collection

Data were collected by trained interviewers during in-home interviews, including all days of the week and seasons of the year.

2.3.1. Sociodemographic information

Participants self-reported their age, sex (gender identity was not collected), immigrant status and the length of time since they immigrated to Canada (non-immigrant, <10 years, ≥10 years), their highest level of educational attainment (less than high school, high school diploma, some post-secondary or trade/diploma/certificate, Bachelor's degree, higher than Bachelor's degree) and their total pre-tax annual household income. Statistics Canada imputed annual household income for 24.1% of adult respondents in 2015, and we used Statistics Canada procedures to impute income for 11.4% of adults in 2004 (Yeung & Thomas, 2013). Statistics Canada confirmed that the imputation process preserved 89–94% of all income quintiles. The adequacy of annual household income was calculated by adjusting household income for the low-income cut-off corresponding to each participants' household and community size in the year prior to each survey (Statistics Canada, 2014). Values were then classified into quintiles for each year.

2.3.2. Indigenous status and race/ethnicity

Participants self-reported Indigenous status and race/ethnicity based on the following two questions. First, respondents were asked, “Are you an Aboriginal person, that is, First Nations (Status or Non-status), Metis or Inuk (Inuit)?” If respondents answered “no” to the first question they were then asked, “You may belong to one or more racial or cultural groups on the following list. Are you: White, Chinese, South Asian, Black, Filipino, Latin American, Southeast Asian, Arab, West Asian, Japanese, Korean, or Other?” Responses to these two questions were used to classify respondents as: Indigenous, White, East/Southeast Asian (includes Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean and Southeast Asian), South Asian, Black, Latin American, Middle Eastern (includes Arab and West Asian) and ‘Other’ (participants who self-identified as ‘Other’ or who selected more than one response option).

Race denotes membership in a group based on shared phenotypical characteristics (e.g., skin colour), while ethnicity denotes group membership based on shared culture (e.g., language, customs, beliefs) and/or geographic ancestry (Braveman & Parker Dominguez, 2021). Because the CCHS–N asked respondents to self-report whether they belonged to one or more racial or cultural groups without distinguishing between the two, we refer to racial/ethnic groups throughout this paper. In doing so, we do not intend to suggest that these two constructs have identical implications for dietary intake. We use the term racial/ethnic minority groups to refer to individuals who are not Indigenous or White.

2.3.3. Dietary intake

Participants completed an in-person 24-h dietary recall to report all foods and beverages consumed from midnight to midnight the previous day using the validated Automated Multiple Pass Method (Conway et al., 2003; Moshfegh et al., 2008).

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Diet quality

Nutrient intakes were derived from the Canadian Nutrient File (2004: 2001b version; 2015: 2015 version) (Health Canada, 2015), and these codes were then linked to codes from the US Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (United States Department of Agriculture, 2016) and the US Food Patterns Equivalents Database (United States Department of Agriculture, 2017) to estimate intakes of adequacy (total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein foods, seafood and plant proteins, fatty acids) and moderation components (refined grains, sodium, added sugars, saturated fats) required to calculate Healthy Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015) scores from 0 to 100 (Krebs-Smith et al., 2018; National Cancer Institute, 2017). The HEI-2015 is among the most robust diet quality scores (Miller et al., 2020) and is strongly associated with risk of chronic disease (Reedy et al., 2018). HEI-2015 total and component scores were calculated using the National Cancer Institute's simple HEI scoring algorithm which is a recommended approach for describing mean scores at a population level (National Cancer Institute, 2020).

2.4.2. Proportion of energy from NOVA food groups

The NOVA (a name, not an acronym) classification scheme was used to classify foods and beverages into one of four mutually exclusive groups: 1) unprocessed or minimally processed foods (e.g., fresh, frozen, dried fruits, vegetables, meat, fish, dairy); 2) processed culinary ingredients (e.g., cooking oil, salt); 3) processed foods (e.g., canned fish and vegetables); and 4) UPF (e.g., ready to eat frozen meals, industrially manufactured cakes and cookies) (Monteiro et al., 2019; Polsky et al., 2020). Classifications were based on food item descriptions in the Canadian Nutrient File (Health Canada, 2015). Food items from 2015 were classified first, and identical or similar items from 2004 were automatically classified into the same group. For meals and composite dishes, the underlying ingredients were classified individually if they were not consumed in a fast-food restaurant, otherwise they were categorized as UPF. Finally, the energy content of each food was derived from the Canadian Nutrient File to calculate the proportion of total daily energy (excluding alcohol) consumed from each NOVA food group.

2.4.3. Absolute and relative gaps in diet quality and intake of ultra-processed foods

To calculate absolute gaps, the mean HEI-2015 score and proportion of energy consumed as UPF of the White reference group was subtracted from that of the other groups (Harper et al., 2010). Positive gaps indicate that HEI-2015 scores and UPF intake are higher in Indigenous or racial/ethnic minority groups relative to White adults, while negative values indicate the reverse. Relative dietary gaps were calculated as the ratio of HEI-2015 scores and proportion of energy consumed as UPF among Indigenous and racial/ethnic minority groups to that of the White reference group. Values greater than 1 indicate that HEI-2015 scores and UPF intake are higher in Indigenous or racial/ethnic minority groups relative to White adults, while values below 1 indicate the reverse. When gaps become further away from 0 (absolute) or 1.0 (relative) they are widening. Note that the interpretation of gaps differs for HEI-2015 scores and UPF intake because a higher diet quality is desirable whereas higher UPF intake is not. For example, a negative absolute gap in HEI-2015 scores indicates that racial/ethnic minority groups had less favourable intakes than White adults whereas a negative absolute gap in UPF intake indicates that racial/ethnic minority groups had more favourable intakes than white adults.

2.4.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for participants in 2004 and 2015. Multivariable linear regression models were used to examine HEI-2015 total and component scores and the proportion of energy consumed from each NOVA food group according to Indigenous status and race/ethnicity in 2004 and 2015. Similar analyses were conducted for absolute and relative dietary gaps. Z-scores were used to examine trends over time (Paternoster R et al., 1998). There were no differences by sex and therefore sex-stratified results are not presented.

Analyses were adjusted for age, sex and dietary recall day (weekday, weekend including Friday). This approach is consistent with recommendations in the literature (Kaufman, 2017; Lesko et al., 2022; Nuru-Jeter et al., 2018) and prior analyses (Patetta et al., 2019; Rehm et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2019). We did not adjust for household income and educational attainment as they mediate the effects of Indigenous status and race/ethnicity on diet quality and UPF intake (Howe et al., 2022; Nuru-Jeter et al., 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2022). Adjusting for these indicators misrepresents reality by creating a pseudo population in which all groups have a similar distribution of income and education (Kaufman, 2017; Lesko et al., 2022). Such analyses mask the true state of dietary inequities and strip away the effects of the historical and contemporary social processes that have patterned dietary intake (Howe et al., 2022; Nuru-Jeter et al., 2018). Nevertheless, to better understand the drivers of between-group differences in dietary intake we adjusted for household income adequacy and educational attainment in sensitivity analyses.

Following imputation of household income, missing data were minimal (<1% for all variables) and therefore list-wise deletion was used. Person-specific and bootstrap weights provided by Statistics Canada were used to account for the complex sampling design, to adjust for non-response, and ensure accurate estimation of variance components. Analyses were conducted using RStudio (RStudio Team, Boston, MA) with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

2.4.5. Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine potential drivers of between-group differences in overall diet quality and UPF intake. The first model was adjusted for immigrant status (non-immigrant, <10 years, ≥10 years) (Vang et al., 2017). Models two through four were adjusted for educational attainment and household income adequacy separately and then jointly. A fifth model adjusted for an indicator of dietary intake misreporting, the ratio of total energy intake to total energy expenditure, assuming a low active physical activity level (Huang et al., 2005).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

The weighted sample was evenly split between males and females in both years (Table 1). Participants were on average 46.0 years of age in 2004 and 48.9 years in 2015. The proportion of adults who self-identified as White declined from 83.4% in 2004 to 73.5% in 2015, while the proportion of adults who self-identified as Indigenous or as belonging to a racial/ethnic minority group increased during this period. Mean HEI-2015 scores increased by 5 points, from 54.1 in 2004 to 59.1 in 2015, while the mean proportion of energy from UPF declined slightly from 43.3% in 2004 to 41.9% in 2015.

Table 1.

Characteristics of adults who participated in the Canadian Community Health Survey – Nutrition in 2004 (weighted N = 23,682,000) or 2015 (weighted N = 27,566,000)a.

| Variables | 2004 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age; mean ± SD | 46.0 ± 17.3 | 48.9 ± 17.5 | |

| NOVA food group % of energyb± SD | Unprocessed and minimally processed foods | 39.8 ± 19.0 | 39.6 ± 19.0 |

| Processed culinary ingredients | 7.3 ± 7.4 | 7.2 ± 7.3 | |

| Processed foods | 5.8 ± 8.3 | 7.3 ± 10.5 | |

| Ultra-processed foods | 43.3 ± 20.0 | 41.9 ± 20.3 | |

| HEI–2015 score mean ± SD | Total score | 54.1 ± 12.7 | 59.1 ± 14.0 |

| Sex N (%) | Female | 11,846,000 (50.0) | 13,778,000 (50.0) |

| Male | 11,836,000 (50.0) | 13,788,000 (50.0) | |

| Educational attainment N (%) | Less than high school | 4,645,000 (19.8) | 3,254,000 (11.8) |

| High school diploma | 4,256,000 (18.1) | 7,337,000 (26.7) | |

| Some post-secondary | 10,008,000 (42.6) | 9,259,000 (33.8) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 3,139,000 (13.3) | 5,071,000 (18.5) | |

| Higher than Bachelor's degree | 1,402,000 (5.9) | 2,468,000 (9.0) | |

|

Household income adequacy quintilesc,d N (%) |

First (lowest income level) | 4,009,000 (16.9) | 5,095,000 (18.5) |

| Second | 4,231,000 (17.9) | 5,334,000 (19.4) | |

| Third | 4,889,000 (20.6) | 5,031,000 (18.3) | |

| Fourth | 5,276,000 (22.3) | 6,018,000 (21.8) | |

| Fifth (highest income level) | 5,008,000 (21.1) | 6,085,000 (22.1) | |

|

Indigenous status and race/ethnicitye,f N (%) |

White | 19,761,000 (83.4) | 20,263,000 (73.5) |

| East/South East Asian | 1,375,000 (5.8) | 2,410,000 (8.7) | |

| South Asian | 826,000 (3.5) | 1,230,000 (4.5) | |

| Other | 540,000 (2.3) | 926,000 (3.4) | |

| Black | 433,000 (1.8) | 928,000 (3.4) | |

| Middle Eastern | 313,000 (1.3) | 667,000 (2.4) | |

| Indigenous | 271,000 (1.1) | 748,000 (2.7) | |

| Latin American | 121,000 (0.5) | 352,000 (1.3) | |

|

Immigrant status N (%) |

10 years or more | 3,845,000 (16.2) | 5,549,000 (20.1) |

| Less than10 years | 1,691,000 (7.1) | 1,883,000 (6.8) | |

| Non-immigrant | 18,112,000 (76.5) | 19,985,000 (72.5) | |

|

Day of dietary recall N (%) |

Weekday | 13,811,000 (58.3) | 15,976,000 (58.0) |

| Weekend (includes Fridays) | 9,870,000 (41.7) | 11,590,000 (42.0) | |

HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; SD, Standard Deviation.

Data are weighted to be nationally representative and are rounded in accordance with Statistics Canada's confidentiality policies.

Alcohol was excluded from total daily energy intake.

Household income adequacy was calculated by adjusting total household income for the low-income cut-offs that correspond to the household and community size of each respondent.

In 2004, the income adequacy quintiles were: 0–96.5%, 96.6–153%, 154–224%, 225–322% and >322% of the low-income cut-off. In 2015, the quintiles were: 0–106%, 107–169%, 170–249%, 250–376% and >376% of the low-income cut-off.

Groups are listed in order based on their proportion of the total population in 2004.

Other includes respondents who self-identified as Other or who selected multiple options.

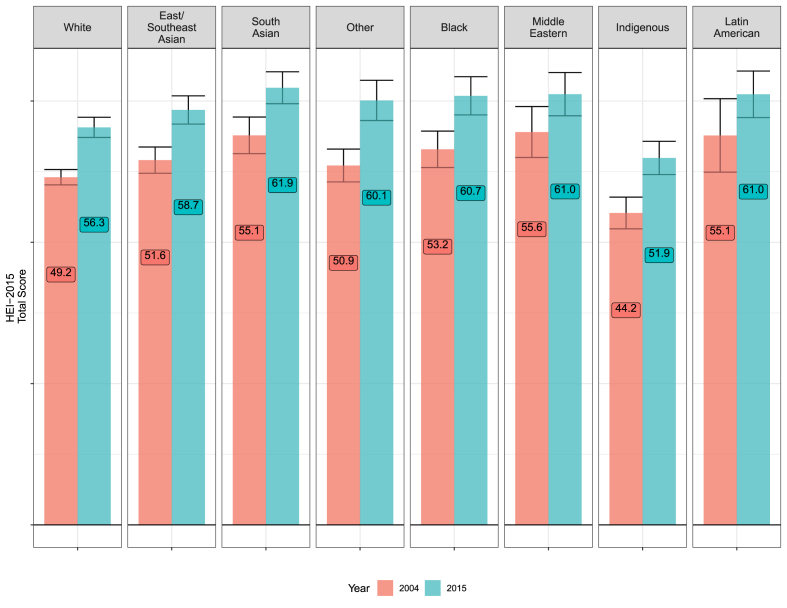

3.2. Diet quality

Mean HEI-2015 total scores ranged from 44.2 (95% CI 41.9, 46.4) among Indigenous adults to 55.6 (95% CI 52.0, 59.2) among Middle Eastern adults in 2004, and from 51.9 (95% CI 49.6, 54.3) among Indigenous adults to 61.9 (95% CI 59.6, 64.1) among South Asian adults in 2015 (Table 2; Fig. 2). Absolute gaps in HEI-2015 scores ranged from −5.1 (95% CI -7.2, −2.9) among Indigenous adults to 6.4 (95% CI 2.8, 10.0) among Middle Eastern adults in 2004, and from −4.3 (95% CI -6.4, −2.2) among Indigenous adults to 5.6 (95% CI 3.7, 7.5) among South Asian adults in 2015 (Table 3). With the exception of ‘Other’ adults in 2004 and Indigenous adults in both years, all absolute gaps were significantly positive, indicating that adults from most racial/ethnic minority groups had consistently higher HEI-2015 scores than White adults. Relative gaps were extremely small, ranging from 0.9 to 1.1.

Table 2.

Trends in Healthy Eating Index-2015 total scores and proportion of energy from ultra-processed foods by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity among adults who participated in the Canadian Community Health Survey – Nutrition in 2004 (weighted N = 23,682,000) or 2015 (weighted N = 27,566,000)a.

| Outcome | Indigenous status and race/ethnicityb,c | 2004 Meand (95% CI) |

2015 Meand (95% CI) |

p trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HEI-2015 Total score (possible range 0–100) |

White | 49.2 (48.1, 50.3) | 56.3 (54.8, 57.7) | <0.001 |

| East/Southeast Asian | 51.6 (49.8, 53.5) | 58.7 (56.7, 60.7) | <0.001 | |

| South Asian | 55.1 (52.5, 57.7) | 61.9 (59.6, 64.1) | <0.001 | |

| Other | 50.9 (48.5, 53.2) | 60.1 (57.2, 62.9) | <0.001 | |

| Black | 53.2 (50.6, 55.7) | 60.7 (58.0, 63.4) | <0.001 | |

| Middle Eastern | 55.6 (52.0, 59.2) | 61.0 (57.9, 64.0) | 0.025 | |

| Indigenous | 44.2 (41.9, 46.4) | 51.9 (49.6, 54.3) | <0.001 | |

| Latin American | 55.1 (49.9, 60.3) | 61.0 (57.7, 64.2) | 0.06 | |

| Ultra-processed foods (% of energy) | White | 53.0 (51.3, 54.7) | 45.9 (43.5, 48.3) | <0.001 |

| East/Southeast Asian | 37.4 (34.7, 40.2) | 32.4 (29.7, 35.1) | 0.01 | |

| South Asian | 37.1 (33.0, 41.2) | 31.0 (27.8, 34.3) | 0.023 | |

| Other | 48.6 (44.3, 52.9) | 35.9 (32.1, 39.6) | <0.001 | |

| Black | 51.1 (46.4, 55.7) | 38.9 (33.6, 44.3) | <0.001 | |

| Middle Eastern | 38.1 (31.8, 44.4) | 34.3 (29.4, 39.1) | 0.35 | |

| Indigenous | 58.2 (55.0, 61.4) | 51.9 (48.2, 55.7) | 0.012 | |

| Latin American | 45.4 (39.5, 51.2) | 41.0 (36.0, 45.9) | 0.259 |

Analyses were conducted for 2004 and 2015 separately using multivariable linear regression models and were adjusted for age, sex, and dietary recall day. Z-scores were used to examine trends between 2004 and 2015.

HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; CI, confidence interval.

Data are weighted to be nationally representative and are rounded in accordance with Statistics Canada's confidentiality policies.

Groups are listed in order based on their proportion of the total population in 2004.

Other includes respondents who self-identified as Other or who selected multiple options.

Within year values are all significantly different from zero (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Trends in Healthy Eating Index-2015 total scores by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity among participants in the Canadian Community Health Survey – Nutrition 2004 and 2015.

Table 3.

Trends in absolute and relative gaps in Healthy Eating Index-2015 total scores and proportion of energy from ultra-processed foods by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity among adults who participated in the Canadian Community Health Survey – Nutrition in 2004 (weighted N = 23,682,000) or 2015 (weighted N = 27,566,000)a.

| Outcome | Indigenous status and race/ethnicityb,c | 2004 Absolute gapsd (95% CI) |

2015 Absolute gapsd (95% CI) |

p trend | 2004 Relative gapsd (95% CI) |

2015 Relative gapsd (95% CI) |

p trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HEI-2015 Total score (possible range 0–100) |

White | Reference | |||||

| East/Southeast Asian | 2.4 (0.8, 4.0)* | 2.5 (0.7, 4.2)* | 0.969 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1)* | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1)* | 0.849 | |

| South Asian | 5.9 (3.5, 8.4)** | 5.6 (3.7, 7.5)** | 0.841 | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2)** | 1.1 (1.1, 1.1)** | 0.549 | |

| Other | 1.7 (−0.5, 3.9) | 3.8 (1.2, 6.4)* | 0.213 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)* | 0.284 | |

| Black | 4.0 (1.5, 6.4)* | 4.5 (2.1, 6.9)** | 0.769 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)* | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)** | 0.984 | |

| Middle Eastern | 6.4 (2.8, 10.0)** | 4.7 (1.9, 7.5)* | 0.465 | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2)** | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1)* | 0.325 | |

| Indigenous | −5.1 (−7.2, −2.9)** | −4.3 (−6.4, −2.2)** | 0.633 | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9)** | 0.9 (0.9, 1.0)** | 0.408 | |

| Latin American |

5.9 (0.8, 11.1)* |

4.7 (1.4, 7.9)* |

0.691 |

1.1 (1.0, 1.2)* |

1.1 (1.0, 1.1)* |

0.565 |

|

| Ultra-processed foods (% of energy) | White | Reference | |||||

| East/Southeast Asian | −15.6 (−17.9, −13.3)** | −13.5 (−15.5, −11.6)** | 0.173 | 0.7 (0.7, 0.8)** | 0.7 (0.7, 0.7)** | 0.834 | |

| South Asian | −15.9 (−19.9, −12.0)** | −14.9 (−17.6, −12.1)** | 0.664 | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8)** | 0.7 (0.6, 0.7)** | 0.528 | |

| Other | −4.4 (−8.6, −0.3)* | −10.1 (−13.6, −6.5)** | 0.043 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0)* | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9)** | 0.012 | |

| Black | −2.0 (−6.5, 2.6) | −7.0 (−11.7, −2.3)* | 0.133 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0)* | 0.087 | |

| Middle Eastern | −14.9 (−21.1, −8.8)** | −11.7 (−16.5, −6.8)** | 0.416 | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8)** | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8)** | 0.789 | |

| Indigenous | 5.2 (2.2, 8.1)** | 6.0 (2.7, 9.4)** | 0.703 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2)** | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2)** | 0.445 | |

| Latin American | −7.7 (−13.3, −2.0)* | −5.0 (−9.3, −0.6)* | 0.459 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0)* | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0)* | 0.644 | |

Analyses were conducted for 2004 and 2015 separately using multivariable linear regression models and were adjusted for age, sex, and dietary recall day. Z-scores were used to examine trends between 2004 and 2015.

HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index-2015; CI, confidence interval.

Data are weighted to be nationally representative and are rounded in accordance with Statistics Canada's confidentiality policies.

Groups are listed in order based on their proportion of the total population in 2004.

Other includes respondents who self-identified as Other or who selected multiple options.

For within-year values * indicates p < 0.05 and ∗∗ indicates p < 0.001 compared to zero (absolute gaps) and 1.0 (relative gaps).

Mean HEI-2015 total scores improved significantly among Indigenous adults and adults from all racial/ethnic groups over time with the exception of Latin American adults (p = 0.06) (Table 2; Fig. 2). As such, all absolute and relative gaps in HEI-2015 total scores remained stable over time (Table 3).

Findings for HEI-2015 components exhibited substantial variability (Supplemental Table S1 and S.2). There were more absolute (mostly positive except for Indigenous adults) and relative (mostly >1.0 except for Indigenous adults) gaps in intakes of total fruits, whole fruits, seafood and plant proteins, sodium and saturated fats compared to other components. For dairy and refined grains, absolute gaps were often negative and relative gaps were often <1.0, indicating more healthful intakes among White adults. Trends over time were mostly stable with some evidence of widening or narrowing gaps for some components.

3.3. Proportion of energy from NOVA food groups

The mean proportion of energy from UPF ranged from 37.1% (95% CI 33.0, 41.2) among South Asian adults to 58.2% (95% CI 55.0, 61.4%) among Indigenous adults in 2004; and from 31.0% (95% CI 27.8, 34.3) among South Asian adults to 51.9% (95% CI 48.2, 55.7) among Indigenous adults in 2015 (Table 2; Fig. 3). Absolute gaps in UPF intake ranged from −15.9% (95% CI -19.9, −12.0) among South Asian adults to 5.2% (95% CI 2.2, 8.1) among Indigenous adults in 2004, and from −14.9% (95% CI -17.6, −12.1) among South Asian adults to 6.0% (95% CI 2.7, 9.4) among Indigenous adults in 2015 (Table 3). Except for Black adults in 2004 and Indigenous adults in both years, all absolute gaps were significantly negative, indicating that adults from most racial/ethnic minority groups had consistently lower UPF intake than White adults. Relative gaps were small, ranging from 0.7 to 1.1.

Fig. 3.

Trends in the proportion of energy from ultra-processed foods by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity among participants in the Canadian Community Health Survey – Nutrition 2004 and 2015.

The proportion of energy consumed as UPF declined over time in all groups except among Middle Eastern and Latin American adults (Table 2; Fig. 3). Absolute and relative gaps in UPF intake remained stable over time for all groups except among ‘Other’ adults where gaps widened over time. This indicates that ‘Other’ adults exhibited a greater decline in UPF intake than the White reference group (Table 3).

Absolute gaps in intakes of unprocessed and minimally processed foods were positive and relative gaps were >1.0 for all groups, except for among Indigenous and Latin American adults (Supplemental Table S1 and S.2). This indicates that most racial/ethnic minority groups had more favourable (i.e., higher) intakes than White adults. There were very few absolute or relative gaps in intakes of processed culinary ingredients, with more gaps observed for processed foods—and these gaps were in varying directions. Trends over time were mostly stable with some evidence of widening or narrowing gaps for some NOVA groups.

3.4. Sensitivity analyses

In models adjusted for immigration status, indicators of socioeconomic position (SEP) and dietary misreporting, the patterning of HEI-2015 scores and UPF intake and in absolute and relative gaps was consistent with the main analyses, as were trends in absolute and relative gaps (Supplemental Table S3, S4 and S5).

4. Discussion

Historical and contemporary policies, practices and norms have contributed to inequitable health outcomes among Indigenous people and adults from many racial/ethnic minority groups in Western nations, although dietary inequities have not yet been well characterized. This study was the first to quantify absolute and relative gaps in the diet quality and UPF intake of a nationally representative sample of adults according to Indigenous status and race/ethnicity and trends over time. Contrary to expectations, individuals from most racial/ethnic minority groups consistently maintained higher mean diet quality and lower mean UPF intake than White adults. By contrast, Indigenous adults had consistently poorer mean diet quality and higher mean UPF intake than all other groups, indicating that Indigenous status is a distinct determinant of dietary inequities in Canada.

With respect to our first objective, absolute gaps in diet quality were mostly positive, indicating that adults from most racial/ethnic minority groups had higher diet quality than White adults. Of the groups examined, Black, South Asian, Latin American and Middle Eastern adults consistently had the highest diet quality, whereas White and Indigenous adults consistently had the lowest. These findings were surprising, as individuals from racial/ethnic minority groups experience racial discrimination which constrains their access to material and social resources required to support a high-quality dietary pattern (e.g., education, income) and increases psychosocial stress (Rodrigues et al., 2022; Siddiqi et al., 2017). Indeed, experiences of racism have been directly associated with poorer diet quality among racial/ethnic minority groups (Rodrigues et al., 2022). However, consistent with our findings, other studies have also found that adults from racial/ethnic minority groups have better health-related risk factor profiles than White and Indigenous adults in Canada (Siddiqi et al., 2017). Nevertheless, although statistically significant, many of the dietary gaps we observed were smaller than the 5 point threshold often considered to indicate clinically meaningful differences in HEI-2015 scores (Kirkpatrick et al., 2018) and all relative gaps were likely too small to be meaningful. Overall, our findings indicate that the diet quality of all adults in Canada is poor regardless of Indigenous status or race/ethnicity, highlighting a need for widespread improvements to food environments to support healthier dietary patterns for all.

The patterning of UPF intake was very similar to the patterning of overall diet quality, with Middle Eastern, East/Southeast Asian and South Asian adults consistently having the most favourable intakes (i.e., lowest) and Indigenous and White adults having the least favourable intakes (i.e., highest), yielding mostly negative absolute gaps. However, the divergence in intakes was much larger for UPF intake, as South Asian adults obtained less than one-third, and Indigenous adults obtained more than one-half, of their energy from UPF. The very high UPF intake of Indigenous people is particularly concerning and is similar to that of Indigenous people living on-reserve in a prior study (Batal et al., 2018). Even 5% increments in UPF consumption have been associated with higher BMI and waist circumference (Martinez-Perez et al., 2021), and therefore the positive absolute gaps in UPF intake between Indigenous and White adults we observed may partially explain the higher rates of obesity among Indigenous adults in Canada (Batal & Decelles, 2019; Batal et al., 2018). By contrast, absolute gaps were negative for racial/ethnic minority groups and many of these gaps exceeded 10%. Increments of 10% in UPF intake have been associated with increased risk of chronic disease and mortality (Lane et al., 2021; Schnabel et al., 2019). Such large gaps could therefore yield a health disadvantage for White adults. Relative gaps were again very small.

With respect to our second objective, a positive finding was that the diet quality and UPF intake of Indigenous adults and adults from most racial/ethnic groups improved between 2004 and 2015, such that absolute and relative gaps remained stable in all but one case (i.e., UPF intake of ‘Other’ adults). Other studies in Canada (Olstad et al., 2021) and the US (Rehm et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2019) have also found that diet quality improved over similar periods. As this is the first study to characterize trends in the diet quality and UPF intake of racial/ethnic minority groups in Canada, there are no prior studies to which we can compare these findings. With respect to Indigenous people, Riediger et al. (Riediger et al., 2022) also found that Indigenous adults had poorer diet quality than non-Indigenous adults in Canada, however they concluded that the diet quality of Indigenous adults was unchanged between 2004 and 2015. Methodological differences likely account for these discrepancies, as they adjusted for indicators of SEP to isolate trends in diet quality independent of SEP, whereas we did not adjust for SEP because SEP mediates associations between Indigenous status and diet quality. Thus, whereas Riediger et al. estimated trends in diet quality in a theoretical scenario where the SEP of Indigenous and non-Indigenous adults was equal, we estimated actual trends in dietary inequities according to Indigenous status in Canada.

Many of the nations from which racial/ethnic minority groups in Canada originate have rich cultural food traditions typified by consumption of home-cooked meals prepared from whole foods such as vegetables, grains and protein-based foods, and eaten in communal settings. To the extent that individuals maintain these dietary practices in Canada, they may maintain a high quality diet that minimizes their consumption of UPF. However, globalization, urbanization, economic development and changing workforce dynamics are driving a global nutrition transition towards lower quality dietary patterns with greater consumption of UPF (Baker et al., 2020). These trends are concerning, as UPF may have distinctly negative implications for human health over and above their often poor nutrient profiles (Scrinis & Monteiro, 2022). Similarly, Indigenous people have a rich cultural heritage founded on consumption of nutrient-rich traditional foods obtained directly from the land, including wild foods such as fish, game, fowl, roots, and berries (Kuhnlein & Receveur, 1996). The dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands has reduced their intake of traditional foods and increased their reliance on UPF, with corresponding negative implications not only for diet-related health, but also for Indigenous food sovereignty, food security, cultural identity, and connections with the land (Batal et al., 2018).

In the current study, the overall diet quality of adults from many racial/ethnic minority groups was similar to, and sometimes higher than the diet quality of groups with the highest SEP (i.e., household income, educational attainment and neighbourhood deprivation) in a prior study based on the same data (Olstad et al., 2021). Moreover, dietary gaps between Indigenous and White adults in the current study were smaller than they were for educational groups in the prior study. These findings suggest that educational attainment may be a more important determinant of dietary inequities in Canada than Indigenous status or race/ethnicity. Indeed, Phelan and Link (Phelan & Link, 2015) maintain that associations between racism and health endure largely because racism is a fundamental cause of SEP and SEP is a fundamental cause of health inequities. In other words, SEP mediates differences in health between White and non-White adults.

Although there was limited evidence of racial/ethnic inequities in diet quality and UPF intake in Canada, this does not mean that racial/ethnic minorities did not experience racial discrimination (Siddiqi et al., 2017), or that these experiences did not diminish their diet quality. Indeed, the dietary patterns of adults from racial/ethnic minority groups may have been even more healthful had they not experienced racial discrimination. Therefore, our findings may suggest that broader structural factors shared by racial/ethnic minority groups in Canada—but not by Indigenous people—assisted them to maintain some of their traditional cultural food practices over time despite experiences of discrimination. However, future studies will be needed to test this hypothesis as we lacked data on social structures and experiences of discrimination and thus it is unclear exactly what our racial/ethnic variable captured. Notably, our findings were unchanged when we adjusted for immigrant status, suggesting that they were not driven by a healthy immigrant effect and highlighting the enduring nature of these more healthful dietary patterns.

Some of our findings contrast with those in the US, where Black adults have poorer diet quality than White adults, and where results among Mexican American/Hispanic and ‘Other’ adults are more equivocal (Juul et al., 2022; Patetta et al., 2019; Rehm et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2019; Tao et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2014, 2015). Moreover, some evidence suggests the diet quality of White adults in the US is improving at a faster rate than among some racial/ethnic minority groups, which may portend a widening of inequities in some cases. Inequities in UPF intake are not as stark, as White and Black adults in the US have similarly high and increasing intakes, whereas Hispanic adults have more stable and lower intakes (Juul et al., 2022).

We posit that some differences in racial/ethnic inequities in dietary intake between Canada and the US could be attributable to greater dietary acculturation in the US, as Canada has an official policy of multiculturalism that actively supports minority groups to maintain their traditional cultural practices (Banting & Kymlicka, 2004). By contrast, the influence of the traditional Mexican diet has been shown to wane relatively quickly among Mexican adults living in the US (Batis et al., 2011). Moreover, Canada does not have the same legacy of overtly discriminatory policies (e.g., Jim Crow laws), maintains more redistributive policies (e.g., universal healthcare), has much less ethnic segregation, and lower income inequality than the US. These and other structural factors may provide more equitable access to the social determinants of health in Canada, thereby partly buffering some of the negative dietary effects of racial discrimination. Differences in the origins of racial/ethnic minority groups in the two countries may also be consequential. Most adults from racial/ethnic minority groups living in Canada are just one or two generations from arrival (Ramraj et al., 2016; Siddiqi et al., 2013; Siddiqi & Nguyen, 2010). This contrasts somewhat with the situation in the US where the majority of African Americans are US-born (Cunningham et al., 2017). Adults from racial/ethnic minority groups in Canada may therefore not have had as much time to acculturate to Western dietary patterns nor been exposed to the same adverse diet-related social exposures as those living in the US. Such cross-national comparisons are valuable as they show that dietary inequities by race/ethnicity are not inevitable—they may be partly mitigated through more equitable policy that reduces the salience of race/ethnicity in procuring health-related resources. Nevertheless, given that diet quality and UPF intake were poor among all groups, it is clear that all adults have also adopted many unhealthy Western dietary practices. As such, it is important to ensure that Indigenous people and racial/ethnic minority communities in Canada have sufficient access to the material and social resources required to maintain their traditional cultural food practices.

Finally, it is also important to consider factors that may adversely affect the dietary patterns of White adults. Recent scholarship has found that the economic prospects of White males have declined during the past two decades, and that perceived status threat is increasing in tandem (King L et al., 2022; Siddiqi et al., 2019). Objective and perceived threats to individuals' position within the social hierarchy can increase psychosocial stress and engender maladaptive coping strategies such as increased intake of unhealthy ‘comfort foods’ (Hill et al., 2022). Racial/ethnic minority communities may also maintain stronger norms of trust, reciprocity and social support than majority populations, which could dampen psychosocial stress and thereby reduce the need for unhealthy food as a coping mechanism (Martin & Martin, 1978).

To our knowledge, this was the first nationally representative analysis of trends in absolute and relative gaps in diet quality and UPF intake according to Indigenous status and race/ethnicity. Our conclusions remained unchanged in multiple sensitivity analyses. Nevertheless, there are limitations to our analyses, as groups were classified in accordance with categories used by Statistics Canada and for which sample sizes were sufficiently large—thereby obscuring substantial intra-group heterogeneity and conflating race with ethnicity. Moreover, our findings are not generalizable to all Indigenous adults, as Indigenous people living on reserves and in Canada's three northern territories were not included. In addition, the HEI-2015 reflects a western perspective of healthy eating that may not match the perspectives of all the groups examined.

A single 24-h dietary recall cannot fully capture usual dietary intake and may underestimate intake of foods that are not consumed daily. However, a single recall can correctly estimate mean dietary intake at a population level, which was consistent with our aims (National Cancer Institute, 2020). All self-reported dietary intake data are subject to misreporting, however misreporting would only affect our findings if it differed by Indigenous status and race/ethnicity and over time, which we do not have reasons to expect. In addition, findings were unchanged when we adjusted for an indicator of dietary misreporting.

5. Conclusion

Adults from six racial/ethnic minority groups had consistently higher diet quality and lower UPF intake than White adults between 2004 and 2015. By contrast, Indigenous adults had consistently poorer diet quality and higher UPF intake than White adults. Absolute and relative dietary gaps remained largely stable over this period. Our findings may suggest that broader social structures in Canada partially buffered some of the negative effects of racial discrimination on the dietary patterns of adults from racial/ethnic minority groups by encouraging them to retain some of the healthful aspects of their traditional cultural food practices. However, they also highlight persistent inequities in the treatment of Canada's Indigenous people that have made it challenging for them to access and consume their traditional foods. Findings from this research can inform transferable policy lessons that other nations can apply to reduce dietary inequities in their own contexts (with appropriate adaptations) and that Canada itself can leverage to better support and protect the traditional cultural food practices of its Indigenous people and of racial/ethnic minority groups.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN 155916; PJT-173367). SN was supported by a Libin Cardiovascular Institute/Cumming School of Medicine Postdoctoral Award. RB and LV are funded by Research Scholar Junior 1 awards from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé. KML is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Emerging Leadership Fellowship (APP1173803). The study funders had no role in study design, in collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in writing the article, or in the decision to submit it for publication.

Authors’ contributions

DLO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data interpretation, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition; SN: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data interpretation, Writing – Review and editing; RB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data interpretation, Writing – Review and editing; JCM and JP: Methodology, Data interpretation, Writing – Review and editing; LV: Data interpretation, Writing – Review and editing, Funding acquisition; KML: Data interpretation, Writing – Review and editing; SHP: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data interpretation, Writing – Review and editing, Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101496.

Contributor Information

Dana Lee Olstad, Email: dana.olstad@ucalgary.ca.

Sara Nejatinamini, Email: sara.nejatinamini@ucalgary.ca.

Rosanne Blanchet, Email: rosanne.blanchet@umontreal.ca.

Jean-Claude Moubarac, Email: jc.moubarac@umontreal.ca.

Jane Polsky, Email: jane.polsky@statcan.gc.ca.

Lana Vanderlee, Email: lana.vanderlee@fsaa.ulaval.ca.

Katherine M. Livingstone, Email: k.livingstone@deakin.edu.au.

Seyed Hosseini Pozveh, Email: seyed.hosseinipozveh@ucalgary.ca.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: Health disparities in aboriginal Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 2):S45–S61. doi: 10.1007/BF03403702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P., Machado P., Santos T., Sievert K., Backholer K., Hadjikakou M., Russell C., Huse O., Bell C., Scrinis G., Worsley A., Friel S., Lawrence M. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obesity Reviews. 2020;21 doi: 10.1111/obr.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banting K., Kymlicka W. 2004. https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/handle/1974/14872/Banting_et_al_2004_Do_Multiculturalism_Policies.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Available:

- Batal M., Decelles S. A scoping review of obesity among indigenous peoples in Canada. J Obes. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/9741090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batal M., Johnson-Down L., Moubarac J.C., Ing A., Fediuk K., Sadik T., Tikhonov C., Chan L., Willows N. Quantifying associations of the dietary share of ultra-processed foods with overall diet quality in First Nations peoples in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario. Public Health Nutrition. 2018;21:103–113. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batis C., Hernandez-Barrera L., Barquera S., Rivera J.A., Popkin B.M. Food acculturation drives dietary differences among Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of Nutrition. 2011;141:1898–1906. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.141473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P., Parker Dominguez T. Abandon "race." focus on racism. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.689462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brlek A., Gregoric M. Diet quality indices and their associations with all-cause mortality, CVD and type 2 diabetes mellitus: An umbrella review. British Journal of Nutrition. 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0007114522003701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway J.M., Ingwersen L.A., Vinyard B.T., Moshfegh A.J. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;77:1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital Signs: Racial Disparities in Age-Specific Mortality Among Blacks or African Americans - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Vol. 66. 2017. pp. 444–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper S., King N.B., Meersman S.C., Reichman M.E., Breen N., Lynch J. Implicit value judgments in the measurement of health inequalities. The Milbank Quarterly. 2010;88:4–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada 2006. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb-dgpsa/pdf/surveill/cchs-guide-escc-eng.pdf Available:

- Health Canada 2015. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/nutrient-data/canadian-nutrient-file-2015-download-files.html Available:

- Hill D., Conner M., Clancy F., Moss R., Wilding S., Bristow M., O'Connor D.B. Stress and eating behaviours in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review. 2022;16:280–304. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2021.1923406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe C.J., Bailey Z.D., Raifman J.R., Jackson J.W. Recommendations for using causal diagrams to study racial health disparities. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2022;191:1981–1989. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T.T., Roberts S.B., Howarth N.C., McCrory M.A. Effect of screening out implausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1205–1217. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul F., Parekh N., Martinez-Steele E., Monteiro C.A., Chang V.W. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2022;115:211–221. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J.S. Statistics, adjusted statistics, and maladjusted statistics. American Journal of Law & Medicine. 2017;43:193–208. doi: 10.1177/0098858817723659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King L., Scheiring G., Nosrati E. Deaths of despair in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology. 2022;48 9.1-9.19. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick S.I., Reedy J., Krebs-Smith S.M., Pannucci T.E., Subar A.F., Wilson M.M., Lerman J.L., Tooze J.A. Applications of the healthy eating Index for surveillance, epidemiology, and intervention research: Considerations and caveats. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2018;118:1603–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs-Smith S.M., Pannucci T.E., Subar A.F., Kirkpatrick S.I., Lerman J.L., Tooze J.A., Wilson M.M., Reedy J. Update of the healthy eating Index: HEI-2015. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2018;118:1591–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein H.V., Receveur O. Dietary change and traditional food systems of indigenous peoples. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1996;16:417–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M.M., Davis J.A., Beattie S., Gomez-Donoso C., Loughman A., O'Neil A., Jacka F., Berk M., Page R., Marx W., Rocks T. Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obesity Reviews. 2021;22 doi: 10.1111/obr.13146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M.M., Gamage E., Travica N., Dissanayaka T., Ashtree D.N., Gauci S., Lotfaliany M., O'Neil A., Jacka F.N., Marx W. Ultra-processed food consumption and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/nu14132568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesko C.R., Fox M.P., Edwards J.K. A framework for descriptive epidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2022;191:2063–2070. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Perez C., San-Cristobal R., Guallar-Castillon P., et al. Use of different food classification systems to assess the association between ultra-processed food consumption and cardiometabolic health in an elderly population with metabolic syndrome (PREDIMED-Plus cohort) Nutrients. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/nu13072471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E.P., Martin J.M. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1978. The Black extended family. [Google Scholar]

- Miller V., Webb P., Micha R., Mozaffarian D., Global Dietary D. Defining diet quality: A synthesis of dietary quality metrics and their validity for the double burden of malnutrition. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2020;4:e352–e370. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro C.A., Cannon G., Levy R.B., Moubarac J.C., Louzada M.L., Rauber F., Khandpur N., Cediel G., Neri D., Martinez-Steele E., Baraldi L.G., Jaime P.C. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition. 2019;22:936–941. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018003762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshfegh A.J., Rhodes D.G., Baer D.J., Murayi T., Clemens J.C., Rumpler W.V., Paul D.R., Sebastian R.S., Kuczynski K.J., Ingwersen L.A., Staples R.C., Cleveland L.E. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;88:324–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moubarac J.C., Batal M., Louzada M.L., Martinez Steele E., Monteiro C.A. Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite. 2017;108:512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute 2017. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/comparing.html Available:

- National Cancer Institute 2020. https://dietassessmentprimer.cancer.gov/approach/table.html Available:

- Nuru-Jeter A.M., Michaels E.K., Thomas M.D., Reeves A.N., Thorpe R.J., Jr., LaVeist T.A. Relative roles of race versus socioeconomic position in studies of health inequalities: A matter of interpretation. Annual Review of Public Health. 2018;39:169–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olstad D.L., Nejatinamini S., Victorino C., Kirkpatrick S.I., Minaker L.M., McLaren L. Socioeconomic inequities in diet quality among a nationally representative sample of adults living in Canada: An analysis of trends between 2004 and 2015. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2021;114:1814–1829. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R., Brame R., Mazerolle P., A P. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology. 1998;36:859–866. [Google Scholar]

- Patetta M.A., Pedraza L.S., Popkin B.M. Improvements in the nutritional quality of US young adults based on food sources and socioeconomic status between 1989-1991 and 2011-2014. Nutrition Journal. 2019;18:32. doi: 10.1186/s12937-019-0460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan J.C., Link B.G. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annual Review of Sociology. 2015;41:311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Polsky J.Y., Moubarac J.C., Garriguet D. Consumption of ultra-processed foods in Canada. Health Reports. 2020;31:3–15. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202001100001-eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramraj C., Shahidi F.V., Darity W., Jr., Kawachi I., Zuberi D., Siddiqi A. Equally inequitable? A cross-national comparative study of racial health inequalities in the United States and Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;161:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy J., Lerman J.L., Krebs-Smith S.M., Kirkpatrick S.I., Pannucci T.E., Wilson M.M., Subar A.F., Kahle L.L., Tooze J.A. Evaluation of the healthy eating index-2015. JAND. 2018;118:1622–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm C.D., Penalvo J.L., Afshin A., Mozaffarian D. Dietary intake among US adults, 1999-2012. JAMA. 2016;315:2542–2553. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger N.D., LaPlante J., Mudryj A., Clair L. Examining differences in diet quality between Canadian indigenous and non-indigenous adults: Results from the 2004 and 2015 Canadian community health survey nutrition surveys. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2022;113:374–384. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00580-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues Y.E., Fanton M., Novossat R.S., Canuto R. Perceived racial discrimination and eating habits: A systematic review and conceptual models. Nutrition Reviews. 2022;80:1769–1786. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuac001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel L., Kesse-Guyot E., Alles B., Touvier M., Srour B., Hercberg S., Buscail C., Julia C. Association between ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of mortality among middle-aged adults in France. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019;179:490–498. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrinis G., Monteiro C. From ultra-processed foods to ultra-processed dietary patterns. Nature Food. 2022;3:671–673. doi: 10.1038/s43016-022-00599-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Z., Rehm C.D., Rogers G., Ruan M., Wang D.D., Hu F.B., Mozaffarian D., Zhang F.F., Bhupathiraju S.N. Trends in dietary carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake and diet quality among US adults, 1999-2016. JAMA. 2019;322:1178–1187. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi A., Nguyen Q.C. A cross-national comparative perspective on racial inequities in health: The USA versus Canada. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2010;64:29–35. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi A., Ornelas I.J., Quinn K., Zuberi D., Nguyen Q.C. Societal context and the production of immigrant status-based health inequalities: A comparative study of the United States and Canada. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2013;34:330–344. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi A., Shahidi F.V., Ramraj C., Williams D.R. Associations between race, discrimination and risk for chronic disease in a population-based sample from Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;194:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi A., Sod-Erdene O., Hamilton D., Cottom T.M., Darity W., Jr. Growing sense of social status threat and concomitant deaths of despair among whites. SSM Popul Health. 2019;9 doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada 2014. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110024101&pickMembers%5B0%5D=2.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2014&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2014&referencePeriods=20140101%2C20140101 Available:

- Statistics Canada 2017. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/reference-guide-understanding-using-data-2015.html Available:

- Tao M.H., Liu J.L., Nguyen U.D.T. Trends in diet quality by race/ethnicity among adults in the United States for 2011-2018. Nutrients. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/nu14194178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture 2016. https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fndds/ Available:

- United States Department of Agriculture 2017. https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fped-overview/ Available:

- Vang Z.M., Sigouin J., Flenon A., Gagnon A. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethnicity and Health. 2017;22:209–241. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1246518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.D., Leung C.W., Li Y., Ding E.L., Chiuve S.E., Hu F.B., Willett W.C. Trends in dietary quality among adults in the United States, 1999 through 2010. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174:1587–1595. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.D., Li Y., Chiuve S.E., Hu F.B., Willett W.C. Improvements in US diet helped reduce disease burden and lower premature deaths, 1999-2012; overall diet remains poor. Health Affairs. 2015;34:1916–1922. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Lawrence J.A., Davis B.A. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung C.W., Thomas S. Household Survey Method Division, Statistics Canada; Ottawa, Ontario: 2013. Income imputation for the Canadian community health survey. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.