Abstract

Background

To utilize EQ-5D in economic evaluations, a societal-based value set is needed. To date, no value sets exist for any EQ-5D instrument in Pakistan. Previous EQ-5D studies conducted in Pakistan ‘borrowed’ health preferences developed in other countries. However, for a value set to be valid for Pakistani population, it should represent the preferences of the Pakistani population, and culture and living standards of Pakistan.

Objective

The aim of this study was to derive a Pakistani EQ-5D-3L value set.

Methods

A moderately representative sample aged 18 years and over was recruited from the Pakistani general population. A multi-stage stratified quota method with respect to ethnicity, gender, age and religion was utilized. Two elicitation techniques, the composite time trade-off (cTTO) and discrete choice experiments (DCE) were applied. Interviews were undertaken by trained interviewers using computer-assisted face-to-face interviews with the EuroQol Portable Valuation Technology (EQ-PVT) platform. To estimate the value set, a hybrid regression model combining cTTO and DCE data was used.

Results

A total of 289 respondents who completed the interviews were included for the analysis. The hybrid model correcting for heteroskedasticity without a constant was selected as the final model for the value set. It is shown that being unable to do usual activities (level 3) was assigned the largest weight, followed by mobility level 3, self-care level 3, pain/discomfort level 3 and anxiety/depression level 3. The worst health state was assigned the value − 0.171 in the final model.

Conclusions

A Pakistani country-specific EQ-5D-3L value set is now available. The availability of this value set may help promote and facilitate health economic evaluations and health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) research in Pakistan.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Pakistan did not have an EQ-5D value set. |

| An EQ-5D-3L value set was derived from a moderately representative sample of the Pakistani general population. Data were collected using a rigorous quality control procedure which led to logical and significant models. |

| This Pakistani EQ-5D-3L value set is now becoming available and will be used by health-economic evaluations and health-related quality-of-life studies in Pakistan that use EQ-5D. |

Introduction

The EQ-5D-3L is one of the most widely used preference-based health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) measures worldwide [1]. It was the first of the family of instruments developed by the EuroQol Group [1, 2]. Since its development, it has been translated into more than 150 languages and in various modes of administration. As the multi-attribute utility instrument (MAUI) preferred by most published pharmacoeconomic guidelines, it has been used all over the world to inform resource allocation decisions in economic evaluations [2, 3], and has been accepted as a valid and responsive tool in multiple disease areas, conditions and cultural contexts [4, 5].

The EQ-5D-3L consists of five domains describing health in terms of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each domain has three response levels describing the severity of the health problems from no problems, moderate problems to extreme problems, which defines a total of 243 health states [6]. To assist its role in economic evaluations, health state utilities that range from 0 (equivalent to death) to 1 (equal to full health) are needed to quantify the quality-of-life measures. To this end, valuation studies around world have been conducted to derive the 0–1 utility scale. To date, at least 38 value sets have been developed and on-going (www.euroqol.org).

Pakistan is the world’s fifth-most populous country with almost 242 million people, and has the world’s second-largest Muslim population [7]. Despite the high burden of disease and resource constraints, there is a limited use of patient-centred evidence to inform medical decision-making and/or resource allocation [8]. To date, health outcome measurement in Pakistan has relied almost exclusively on clinical endpoints. Hence, including patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures in decision-making is one step further towards patient autonomy, engagement and dignity within the healthcare system [6]. To improve healthcare resource allocation and patient access, understanding of the public health preferences should play a significant role in priority setting and allocation of the scarce resources [4]. During recent years, an increasing awareness regarding the importance of pharmacoeconomics in Pakistan has been witnessed, which has highlighted the need to conduct high-quality economic evaluations to support and inform pricing and reimbursement decisions and to develop preference-based measures in different disease states [5]. Pakistan intends to employ cost-effectiveness analysis for new and existing medical interventions. The Pakistani government also encourages studies and health decision-making based on cost utility analysis [6].

To date, no value sets exist for either the EQ-5D-3L or the EQ-5D-5L in Pakistan. Previous EQ-5D studies conducted in Pakistan ‘borrowed’ health preferences developed either in Thailand or from the UK [9, 10]. However, for a value set to be valid for Pakistan it should represent the culture and living standards of Pakistan. For this reason, a pilot study was conducted which reported the feasibility of the preference elicitation methods in Pakistani population for the EQ-5D-3L valuations, namely, the time trade-off (TTO) and the discrete choice experiments (DCE) [11]. Based on the confirmation of feasibility of the EQ-5D-3L, the main objective of this study was to conduct a valuation task subsequently to derive a national value set so that calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) from a societal and Pakistani perspective.

Methods

Study Design

This study implemented the standardized EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol developed by EuroQol using the EQ-Portable Valuation Technology (EQ-PVT) [12]. Details of the study design were reported by Malik et al. [11], in which the descriptions of the pilot feasibility study that precedes this EQ-5D-3L valuation study were provided. Two preference elicitation methods were used, including the composite time-trade-off (cTTO) and discrete choice experiments (DCE). In the DCE task, respondents are presented with two EQ-5D-3L health states (State A and State B), and choose the health state they consider to be the best. The cTTO method is more complex. Respondents are presented with two different lives: 10 years in some EQ-5D-3L health state (Life B) and a number of years in full health, smaller than or equal to 10 years (Life A). Respondents choose which life they consider to be the best, and depending on their answer, the number of years in full health is subsequently varied. The cTTO task ends when respondents indicate they are indifferent between Life A and Life B, and a value is inferred from the number of life years in full health are traded. If respondents indicate they would prefer to die (0 years in full health in Life A), they are presented with a lead-time TTO task (LT-TTO), where Life A and Life B are preceded by an extra 10 years in full health (e.g. 10 years in full health in Life A versus 10 years in full health, followed by 10 years in some EQ-5D-3L state in Life B). The procedure of the LT-TTO task is then similar to the regular TTO task. Details of the DCE method [13] and the description of iteration process of cTTO method is available elsewhere [12, 14].

For cTTO, 28 health states being valued, grouped into 3 blocks with 10 health states in each block. The most severe health state, ‘33333’ (the most severe health problems defined by all EQ-5D-3L domains) was included and valued in all three blocks. For DCE, 60 pairs of health states grouped in 6 blocks were used.

All related documents including the interview guides, survey instructions and the EQ-PVT platform were translated into Urdu, the official language of Pakistan. The translation was done by a professional translator commissioned by the EuroQol Office and reviewed by the study team members. The ethics approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee at the Hamdard University (HREC, HUIC-091).

Respondents and Recruitment

A moderately representative sample was recruited from the Pakistani general population. A multi-stage stratified quota sampling approach was used on the basis of respondents’ ethnicity, age, gender and religion beliefs. Adults aged 18 years and older who were able to complete the interviews were included as respondents. Those who reported to have severe mental and/or physical illnesses at the time of survey were excluded. Chan KKW et al. (2020) explored the sample size and prediction accuracy of EQ-5D-3L values and reported that the effect of sample size and threshold for the minimum number of respondents is 300–500 [15]. Moreover, Hansen et al. [16] reported that, keeping in view the cost, the expected gain in prediction accuracy from increasing sample sizes beyond 300–500 respondents is minimal and that the choice of model can compensate for a smaller sample size. Taking this into contemplation, a total of 300 participants were recruited from the three cities using population proportionate to size sampling (PPS) to allocate this sample among the five major ethnic groups of Pakistan. The total sample of 300 participants was distributed among these ethnicities according to their proportion. We considered those cities which have higher density of these ethnic groups, such as Punjabi participants from Lahore, Kashmiri and Pashtun’s participants from Islamabad, and Karachi as the area for Sindhi and Baluchi ethnic communities. Moreover, PPS was also used to allocate quota for each demographic characteristic including gender, age and religion. Data collections were conducted in the three most populous and diverse cities of Pakistan including Islamabad (Capital), Lahore (Punjab) and Karachi (Sindh). Three interviewers who were trained by experts from the EuroQol Research Foundation recruited respondents and conducted the interviews in these cities. Recruitment used several strategies, for example, the networks of the interviewers, promoting via social media, posting flyers in local markets, pharmacies and respondents’ recommendations of other potential respondents. Interviews were performed between February 2019 and August 2019.

Data Quality Control

During the data collection, performance of the interviewers and the quality of data were checked continuously by the quality assurance officers from the EuroQol Research Foundation. Low-quality interviews and/or responses were identified as follows: (1) the lead-time time trade-off (LT-TTO) was not explained by the interviewers; (2) not enough time was spent on explaining the task, using the wheelchair examples—180 s was used as a lower limit; (3) the ten cTTO health states were valued in less than 5 min; and (4) inconsistency was spotted in the cTTO ratings (e.g. if the value for the worst state ‘33333’ was not the lowest value. Data collected by interviewers that met any of these criteria in at least 40% of their interviews were discarded, as they were of suspicious quality. Details of the quality control protocol can be found in the publication by Ramos-Goni et al. [17].

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were first performed to examine the respondents’ demographic information and other general characteristics. Findings were reported using the mean values, standard deviations and percentages/frequencies.

Several models were used to estimate the cTTO data. In these models, the cTTO value, on a scale between 1 and − 1, was used as the dependent variable. Ten dummy variables were constructed representing the presence of a certain level of problems on a dimension in the health states that are valued, coded as regular dummies. These dummies equal 1 if the respective level of problems is present on the respective dimension. For example, MO3 represents mobility problems at level 3, described as ‘confined to bed’. If the health state to be valued has mobility problems described as ‘confined to bed’, MO3 will equal 1, and 0 otherwise. For example, for health state 21322, the variables MO2, UA3, PD2 and AD2 equal 1, and all other variables (MO2, SC2, SC3, UA2, PD3 and PD3) equal 0, as the health state to be valued is not described by those health problems. The first of the estimated models was a random intercept model, which takes into account the nested structure of the data, that is, that responses were nested in respondents, which may cause correlation between responses within respondents. Second, a random intercept Tobit model was estimated. Tobit models account for censoring that may be present in the observed data. In the case of the cTTO, respondents cannot assign values lower than − 1 to a health state, due to the way in which the cTTO task was constructed. However, some respondents may actually be willing to assign an even lower value to some health states, which is then not reflected in the data. To this end, the Tobit model accounted for this censoring of the data at − 1. Third, as responses vary over the severity of health states, with more variation in responses present for more severe health states, the valuation data is likely to be subject to heteroskedasticity as the error term is not constant over the health domains. To account for this heteroskedasticity, we model the variance of the error term as a function of the ten dummy variables that were included as the dependent variables. Lastly, we estimated a Tobit model that corrected both for heteroskedasticity and for the censored nature of the data.

For the DCE data, we estimated a conditional logit model and a probit model. The dependent variable was a binary variable, with 1 indicating the alternative chosen in the paired comparison and 0 otherwise. Both of these models produce values on a latent scale ranging from 0 to some positive value. Therefore, they cannot be used directly to compute QALYs. The DCE data is therefore needed to be anchored onto the 0–1 scale, i.e. the cTTO data, to produce utilities scaled on the 1 (full health) and 0 (dead) QALY scale. This is done via a hybrid modelling strategy [16] in which a joint likelihood function was estimated for the cTTO and DCE data combined. Hybrid models account for the censoring and the heteroskedasticity, and the combination of both cTTO data were used.

All hybrid and cTTO-only models were estimated with and without a constant. All models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). The final value set was selected based on the logical consistency, significance of the coefficients of the models, model fit criteria such as Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and, mean absolute error (MAE). The MAE was computed both as a MAE over all responses, and as a comparison of the mean observed and predicted values for the 28 health states included in the cTTO health state design.

Results

Respondents

In total, 289 respondents were included in the final data analysis. We excluded 11 respondents that were interviewed for practice sessions. The mean age was 34.05 years (SD 12.27 years), 51.2% were female, 47.1% were married, 62.6% had at least a Bachelor’s degree and 4.2% were unemployed. The majority of the respondents were Punjabis (67.5%), and were Urdu speakers (61.5%). Details can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

General characteristics of respondents (N = 289)

| General characteristics | N | % | Representation according to % population of Pakistan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| < 21 years | 28 | 9.7 | 41.6% |

| 21–50 years | 229 | 79.2 | 55.0% |

| > 50 years | 32 | 11.1 | 3.4% |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 141 | 48.8 | 50.8% |

| Female | 148 | 51.2 | 49.2% |

| Religion | |||

| Muslim | 275 | 95.2 | 96.5% |

| Hindu | 3 | 1.0 | 1.7% |

| Christian | 11 | 3.8 | 1.3% |

| Education | – | ||

| Technical diploma | 44 | 15.2 | |

| Primary | 16 | 5.5 | |

| Matric | 5 | 1.7 | |

| Intermediate | 43 | 14.9 | |

| Bachelors | 96 | 33.2 | |

| Masters | 71 | 24.6 | |

| Ph.D. | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Literacy | |||

| Literate | 289 | 100 % | 62.3% literacy rate |

| Total household income | Rs 41,545.00 average monthly household income | ||

| Rs 10,000–20,000 | 39 | 13.5 | |

| Rs 21,000–50,000 | 57 | 19.7 | |

| Rs 51,000–100,000 | 68 | 23.5 | |

| Rs 101,000–150,000 | 52 | 18.0 | |

| Rs 151,000–300,000 | 33 | 11.4 | |

| Rs 301,000–500,000 | 18 | 6.2 | |

| > Rs 500,000 | 16 | 5.5 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 | 2.1 | |

| Employment status | 47.9% Employment to population ratio | ||

| Unemployed | 12 | 4.2 | |

| Government job | 46 | 15.9 | |

| Private job | 102 | 35.3 | |

| Businessman | 5 | 1.7 | |

| Retired | 4 | 1.4 | |

| Student | 69 | 23.9 | |

| Housewife | 34 | 11.8 | |

| Other | 17 | 5.9 | |

| Current marital status | – | ||

| Single | 133 | 46.0 | |

| Married | 136 | 47.1 | |

| Divorced | 9 | 3.1 | |

| Widowed | 11 | 3.8 | |

| City | |||

| Islamabad (Federal Capital) | 100 | 34.4 | 0.51% |

| Lahore (Punjab) | 97 | 33.4 | 5.81% |

| Karachi (Sindh) | 96 | 32.2 | 7.31% |

| Dwelling | |||

| Rural | 49 | 17.0 | 63.5% |

| Urban | 240 | 83.0 | 36.5% |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Punjabi | 145 | 50 | 49.7% |

| Sindhi | 62 | 21.5 | 21.6% |

| Baluchi | 16 | 5.6 | 5.7% |

| Pakhtoon | 52 | 18 | 18% |

| Kashmiri | 14 | 4.9 | 5% |

| Primary language spoken | |||

| Urdu | 180 | 62.3 | 8% |

| Punjabi | 86 | 29.8 | 48% |

| Sindhi | 6 | 2.1 | 10% |

| Pashtu | 6 | 2.1 | 8% |

| Balochi | 3 | 1.0 | 1% |

| Kashmiri | 4 | 1.4 | 1% |

| Other | 4 | 1.4 | 2% |

| Family system | – | ||

| Separate | 170 | 58.8 | |

| Joint family system | 119 | 41.2 |

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 2020

Valuation Data

The means for each health state valued using cTTO are reported in Appendix 1. Four respondents did not trade off any life years for any health state, and were considered non-traders, but were kept in the modelling sample.

The modelling results are reported in Tables 2 (cTTO models), 3 (DCE models) and 4 (hybrid models). The coefficients were monotonically ordered and significant, except for some of the level 2 problems in some of the models. Usual activities level 3 (indicated as UA3) was assigned the largest weight in all estimated models, followed by mobility level 3, self-care level 3, pain/discomfort level 3 and anxiety/depression level 3, depending on the model. For level 2 problems estimates, self-care received the largest weight, followed by either mobility or usual activities, depending on the model. The random intercept model and random intercept Tobit models for the cTTO data, as well as the conditional logit and probit models for the DCE data and the standard hybrid model, produced insignificant parameter estimates for at least one of the level-dimension dummy variables, suggesting that these were assigned a small weight by the respondents. However, when correcting for heteroskedasticity, this issue was resolved, and significant parameter estimates were found.

Table 2.

cTTO modelling results

| cTTO | Random intercept | Random intercept tobit | Heteroskedastic | Heteroskedastic, no constant | Heteroskedastic Tobit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility level 2 (MO2) | 0.013 (0.014) | 0.010 (0.014) | 0.065 (0.007)** | 0.055 (0.006)** | 0.066 (0.006)** |

| Mobility level 3 (MO3) | 0.311 (0.013)** | 0.315 (0.014)** | 0.259 (0.014)** | 0.255 (0.014)** | 0.260 (0.015)** |

| Self-care level 2 (SC2) | 0.068 (0.012)** | 0.068 (0.013)** | 0.057 (0.007)** | 0.054 (0.007)** | 0.057 (0.007)** |

| Self-care level 3 (SC3) | 0.310 (0.013)** | 0.316 (0.013)** | 0.221 (0.010)** | 0.220 (0.010)** | 0.219 (0.011)** |

| Usual activities level 2 (UA2) | 0.025 (0.013) | 0.023 (0.014) | 0.054 (0.007)** | 0.043 (0.006)** | 0.054 (0.006)** |

| Usual activities level 3 (UA3) | 0.343 (0.013)** | 0.348 (0.013)** | 0.278 (0.014)** | 0.273 (0.014)** | 0.280 (0.015)** |

| Pain/discomfort level 2 (PD2) | 0.023 (0.013) | 0.021 (0.013) | 0.052 (0.007)** | 0.041 (0.006)** | 0.052 (0.006)** |

| Pain/discomfort level 3 (PD3) | 0.254 (0.013)** | 0.257 (0.013)** | 0.204 (0.013)** | 0.197 (0.013)** | 0.204 (0.014)** |

| Anxiety/depression level 2 (AD2) | 0.012 (0.013) | 0.010 (0.014) | 0.051 (0.007)** | 0.041 (0.006)** | 0.051 (0.006)** |

| Anxiety/depression level 3 (AD3) | 0.243 (0.013)** | 0.246 (0.013)** | 0.206 (0.013)** | 0.202 (0.013)** | 0.207 (0.014)** |

| Constant | − 0.037 (0.017)* | − 0.037 (0.017* | − 0.022 (0.006)** | − 0.021 (0.006)** | |

| n | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 |

| N | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 |

| Censored cTTO observations | 0 | 107 | 0 | 0 | 107 |

| AIC | 907.73 | 1381.68 | − 27.97 | − 18.18 | 171.65 |

| BIC | 985.33 | 1459.28 | 103.35 | 107.17 | 302.96 |

| MAE (all obs) | 0.205 | 0.207 | 0.205 | 0.206 | 0.205 |

| MAE (28 states) | 0.081 | 0.085 | 0.038 | 0.039 | 0.039 |

N number of respondents that completed cTTO, respectively, n total number of responses, AIC Aikake information criterion, BIC Bayesian information criterion, MAE mean absolute error. MAE is calculated based on all responses, and as a comparison between the mean and predicted value for the 28 health states included in the cTTO health state design

*Significant at 0.05, ** significant at 0.01 (values in brackets are standard errors)

Table 3.

DCE modelling results

| DCE | Conditional logit | Probit |

|---|---|---|

| MO2 | 0.369 (0.110)** | 0.164 (0.059)** |

| MO3 | 3.260 (0.163)** | 1.769 (0.083)** |

| SC2 | 0.637 (0.099)** | 0.336 (0.056)** |

| SC3 | 2.563 (0.138)** | 1.402 (0.075)** |

| UA2 | 0.404 (0.097)** | 0.233 (0.055)** |

| UA3 | 3.414 (0.164)** | 1.876 (0.082)** |

| PD2 | 0.130 (0.098) | 0.074 (0.053) |

| PD3 | 2.520 (0.145)** | 1.375 (0.072)** |

| AD2 | 0.221 (0.104)* | 0.127 (0.058)* |

| AD3 | 2.032 (0.124)** | 1.131 (0.068)** |

| n | 2890 | 2890 |

| N | 289 | 289 |

| AIC | 1929.87 | 1946.15 |

| BIC | 1996.49 | 2005.84 |

N number of respondents that completed DCE, n total number of responses, AIC Aikake information criterion, BIC Bayesian information criterion.

*Significant at 0.05, ** significant at 0.01(values in brackets are standard errors)

Table 4.

Final selected hybrid modelling results

| Hybrid models | Hybrid | Hybrid, no constant | Hybrid tobit | Hybrid, heteroskedastic | Hybrid, Heteroskedastic, no constant (final model) | Hybrid heteroskedastic tobit | Hybrid heteroskedastic Tobit, no constant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MO2 | 0.034 (0.009)** | 0.033 (0.009)** | 0.032 (0.009)** | 0.053 (0.005)** | 0.049 (0.005)** | 0.054 (0.005)** | 0.050 (0.005)** |

| MO3 | 0.323 (0.009)** | 0.321 (0.009)** | 0.325 (0.009)** | 0.282 (0.007)** | 0.279 (0.007)** | 0.284 (0.008)** | 0.280 (0.008)** |

| SC2 | 0.060 (0.008)** | 0.055 (0.008)** | 0.056 (0.008)** | 0.058 (0.005)** | 0.057 (0.005)** | 0.058 (0.005)** | 0.057 (0.005)** |

| SC3 | 0.275 (0.008)** | 0.267 (0.008)** | 0.271 (0.008)** | 0.219 (0.007)** | 0.217 (0.007)** | 0.219 (0.007)** | 0.217 (0.007)** |

| UA2 | 0.041 (0.008)** | 0.038 (0.008)** | 0.038 (0.008)** | 0.045 (0.005)** | 0.040 (0.005)** | 0.045 (0.005)** | 0.040 (0.005)** |

| UA3 | 0.352 (0.009)** | 0.342 (0.008)** | 0.347 (0.008)** | 0.285 (0.008)** | 0.280 (0.007)** | 0.286 (0.008)** | 0.281 (0.008)** |

| PD2 | 0.018 (0.008)* | 0.007 (0.008) | 0.005 (0.008) | 0.041 (0.005)** | 0.035 (0.005)** | 0.041 (0.005)** | 0.036 (0.004)** |

| PD3 | 0.255 (0.008)** | 0.245 (0.008)** | 0.248 (0.008)** | 0.219 (0.007)** | 0.214 (0.006)** | 0.220 (0.007)** | 0.215 (0.007)** |

| AD2 | 0.025 (0.009)** | 0.010 (0.008) | 0.009 (0.008) | 0.043 (0.005)** | 0.036 (0.005)** | 0.043 (0.005)** | 0.037 (0.005)** |

| AD3 | 0.218 (0.008)** | 0.209 (0.007)** | 0.211 (0.008)** | 0.185 (0.007)** | 0.181 (0.006)** | 0.185 (0.007)** | 0.182 (0.007)** |

| Constant | − 0.030 (0.006)** | − 0.012 (0.004)** | − 0.012 (0.004) | ||||

| n (cTTO) | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 |

| n (DCE) | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 | 2890 |

| N (cTTO) | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 |

| N (DCE) | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 | 289 |

| Censored cTTO observations | 0 | 0 | 107 | 0 | 0 | 107 | 107 |

| AIC | 3413.73 | 3439.69 | 3904.35 | 1918.91 | 1928.04 | 2118.69 | 2127.97 |

| BIC | 3500.34 | 3519.64 | 3984.30 | 2072.14 | 2074.61 | 2271.92 | 2274.54 |

| MAE (all obs) | 0.204 | 0.202 | 0.205 | 0.205 | 0.204 | 0.205 | 0.204 |

| MAE (28 states) | 0.073 | 0.076 | 0.077 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.039 | 0.041 |

AIC Aikake information criterion, BIC Bayesian information criterion, MAE mean absolute error. MAE is calculated based on all responses, and as a comparison between the mean and predicted value for the 28 health states included in the cTTO health state design

*Significant at 0.05, ** significant at 0.01. (Values in brackets are standard errors) N indicates the number of respondents that completed cTTO or DCE, n indicates the total number of responses

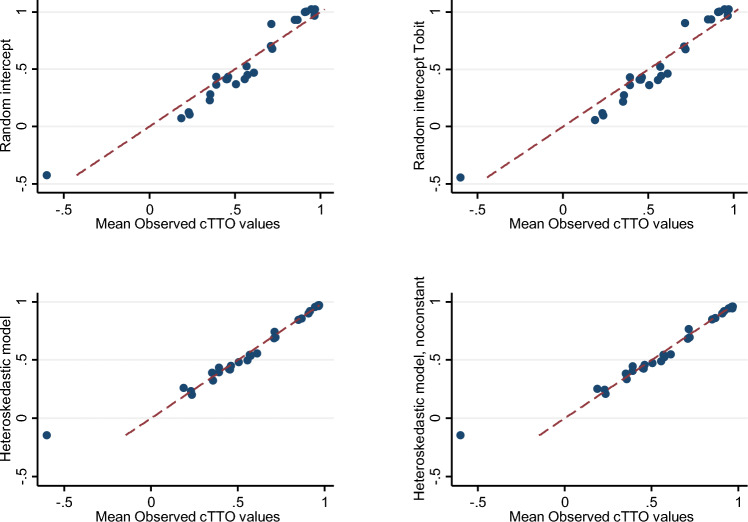

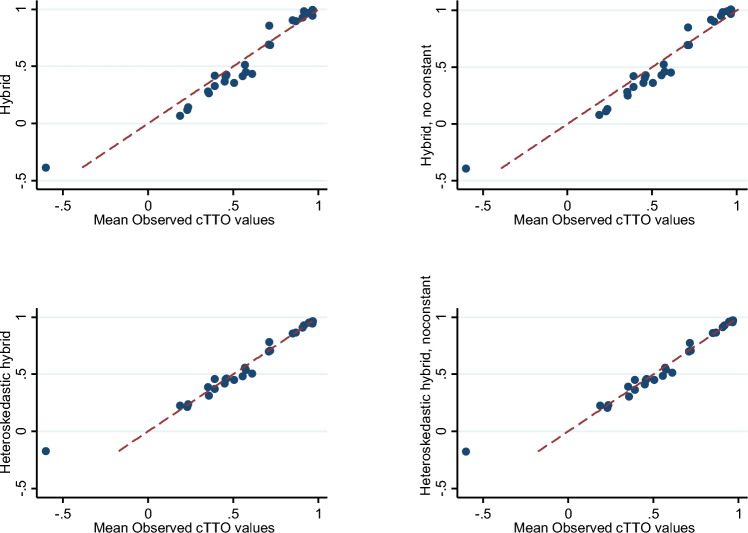

The MAE for the observed means for the 28 health states valued in the cTTO task was substantially higher in models that did not correct for heteroskedasticity, compared with those models that did. Figures 1 and 2 plot the mean observed cTTO values (horizontal axis) versus the predicted values for the cTTO models (Fig. 1) and the hybrid models (Fig. 2). The dashed line was the reference for when they would be equal. What can be seen from Fig. 1, is that the cTTO model correcting for heteroskedasticity predicted the mean values for most health states very well, except for health state 33333, the worst health state. The models that do not correct for heteroskedasticity (e.g. the random intercept model and the Tobit model) predict the mean for 33333 much better, but performs much poorer for all other health states. A similar observation can be made for the hybrid models in Fig. 2, where models correcting for heteroskedasticity predict the mean observed cTTO values very well, but not for 33333, and vice versa for the models that do not correct for heteroskedasticity. This leads to much lower MAEs for models correcting for heteroskedasticity, which suggests a better model fit.

Fig. 1.

Predicted versus mean observed cTTO values for cTTO models

Fig. 2.

Predicted versus mean observed values for hybrid models

Therefore, the hybrid model correcting for heteroskedasticity, without a constant, was selected as the final model for the value set. The value set can then be represented mathematically as:

Based on this study, each health state is then assigned a value between − 0.171 (the worst health state 33333) and 1 (the best health state 11111), with 1.23% of all values being negative (the full value set can be seen in Appendix 2). For example, health state 12312 could then be assigned the value of 0.628.

Discussion

The present study aimed to derive a Pakistani EQ-5D-3L value set. There were 289 respondents who completed the cTTO and DCE tasks as preference elicitation techniques in the EQ-PVT platform. The hybrid model correcting for heteroskedasticity was selected as the final model to represent the value set for Pakistan, ranged between −0.1791 (the worst health state 33333) and 1 (the best health state 11111).

This valuation study of the EQ-5D-3L in Pakistan was conducted following the prior feasibility assessment [11]. A similar approach has been adopted in other countries where a feasibility study was first performed preceding the formal valuation [18, 19]. This EQ-5D-3L value set was developed based on societal preferences obtained from a national representative sample in Pakistan, a country with a large Muslim population and unique cultural aspects. Based on this study, clinicians or researchers in Pakistan are now able to compute Pakistan-specific health state utilities to address their HRQoL measurement needs.

The value for the worst health state ‘33333’ in Pakistani population is − 0.171, which is higher than other EQ-5D-3L value sets in a Muslim majority country such as Tunisia, but lower than 0.131 in Malaysia [20]. Mobility is the dimension in Tunisia and Malaysia that received the largest weight, and in Pakistani population, mobility is the second most weighted. However, Pakistani consider usual activities as the dimension that received the largest weight, but this dimension is considered among the least important in the other two countries.

In terms of modelling used herein, a hybrid model correcting for heteroskedasticity was selected as the final model to represent the value set for Pakistan. This model predicted the mean values for all health states very well, but not for the worst health state 33333. This is due to the fact that the observed mean for 33333 was much lower in relation to the other health states, indicating that respondents are much more willing to give up life years to avoid this health state compared with other health states. The hybrid model we selected was correcting for heteroskedasticity, which ensured that the values for all health states were predicted well, except the worst health state 33333. The alternative was to choose a model that could better estimate the value for health state 33333, but the tradeoff would be worsened predictions for all other health state values. In reality, state 33333 rarely occurs in patients, hence, the model that better represents all other health states was preferred and selected. In comparison to results reported elsewhere, where weights for different health domains varied by country and by statistical models used [21–28]. These differences may very well reflect the country-specific population health preferences, but may also manifest the sociodemographic influences [27] and the possible statistical modelling design artefacts [24]. These differences validate the fact that value sets borrowed from other countries may bias the estimated health outcomes and the need of country-specific value sets. Note that no neighbouring countries of Pakistan (e.g. India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Afghanistan) have their EQ-5D-3L value set; therefore, it is difficult to draw a comparison.

The design of this study led to the use of the EQ-PVT platform developed by the EuroQol Research Foundation. Although effective for the current setting, the EQ-PVT platform is subject to the limitation that it is unable to allow randomization in the blocks of cTTO and DCE, thus each interviewer was assigned specific sequence to ensure equivalence of number of blocks being valued by the respondents. At the same time, the EQ-PVT allowed the current study to be carried out with great flexibility and agility given the circumstances of collecting data in the three cities in Pakistan.

A limitation of the present study must be acknowledged. First, our sample is older, more literate, have higher education and is more urban than the Pakistani general population. To obtain a sample that is highly representative of the general population is challenging, especially respondents who lived in rural areas and those who are illiterate. Future EQ-5D valuation studies in Pakistan, such as for the EQ-5D-5L or EQ-5D-Y, should aim for a more representative sample.

Conclusions

The EQ-5D-3L Pakistani value set was developed on the basis of a hybrid model correcting for heteroskedasticity without constant. The most severe level of problems associated with usual activities followed by mobility were key drivers for the health state utilities in Pakistan. The availability of a Pakistani-specific value set may help promote the uptake of the EQ-5D-3L in health economics evaluations and resource allocation decisions.

Appendix 1: The observed means for each health state valued using cTTO

| Health state | Mean cTTO | Standard error | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11112 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| 11121 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| 11122 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.94 |

| 11211 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| 11313 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.65 |

| 12111 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| 12212 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| 12331 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.57 |

| 13133 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| 13221 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.75 |

| 21111 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| 21133 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.63 |

| 21211 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.93 |

| 21323 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.51 |

| 21332 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| 22121 | 0.85 | 0.01 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| 22222 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.68 | 0.75 |

| 22233 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| 23112 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| 23323 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.30 |

| 31131 | 0.61 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.66 |

| 31223 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.52 |

| 32113 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| 32232 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| 32322 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.43 |

| 33232 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.30 |

| 33311 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| 33333 | − 0.60 | 0.02 | − 0.65 | − 0.55 |

Appendix 2: EQ-5D-3L value set for Pakistan

Table: Value set Pakistan

| State | Value | State | Value | State | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11111 | 1 | 21111 | 0.951 | 31111 | 0.721 |

| 11112 | 0.964 | 21112 | 0.915 | 31112 | 0.685 |

| 11113 | 0.819 | 21113 | 0.770 | 31113 | 0.540 |

| 11121 | 0.965 | 21121 | 0.916 | 31121 | 0.686 |

| 11122 | 0.929 | 21122 | 0.880 | 31122 | 0.650 |

| 11123 | 0.784 | 21123 | 0.735 | 31123 | 0.505 |

| 11131 | 0.786 | 21131 | 0.737 | 31131 | 0.507 |

| 11132 | 0.750 | 21132 | 0.701 | 31132 | 0.471 |

| 11133 | 0.605 | 21133 | 0.556 | 31133 | 0.326 |

| 11211 | 0.960 | 21211 | 0.911 | 31211 | 0.681 |

| 11212 | 0.924 | 21212 | 0.875 | 31212 | 0.645 |

| 11213 | 0.779 | 21213 | 0.730 | 31213 | 0.500 |

| 11221 | 0.925 | 21221 | 0.876 | 31221 | 0.646 |

| 11222 | 0.889 | 21222 | 0.840 | 31222 | 0.610 |

| 11223 | 0.744 | 21223 | 0.695 | 31223 | 0.465 |

| 11231 | 0.746 | 21231 | 0.697 | 31231 | 0.467 |

| 11232 | 0.710 | 21232 | 0.661 | 31232 | 0.431 |

| 11233 | 0.565 | 21233 | 0.516 | 31233 | 0.286 |

| 11311 | 0.720 | 21311 | 0.671 | 31311 | 0.441 |

| 11312 | 0.684 | 21312 | 0.635 | 31312 | 0.405 |

| 11313 | 0.539 | 21313 | 0.490 | 31313 | 0.260 |

| 11321 | 0.685 | 21321 | 0.636 | 31321 | 0.406 |

| 11322 | 0.649 | 21322 | 0.600 | 31322 | 0.370 |

| 11323 | 0.504 | 21323 | 0.455 | 31323 | 0.225 |

| 11331 | 0.506 | 21331 | 0.457 | 31331 | 0.227 |

| 11332 | 0.470 | 21332 | 0.421 | 31332 | 0.191 |

| 11333 | 0.325 | 21333 | 0.276 | 31333 | 0.046 |

| 12111 | 0.943 | 22111 | 0.894 | 32111 | 0.664 |

| 12112 | 0.907 | 22112 | 0.858 | 32112 | 0.628 |

| 12113 | 0.762 | 22113 | 0.713 | 32113 | 0.483 |

| 12121 | 0.908 | 22121 | 0.859 | 32121 | 0.629 |

| 12122 | 0.872 | 22122 | 0.823 | 32122 | 0.593 |

| 12123 | 0.727 | 22123 | 0.678 | 32123 | 0.448 |

| 12131 | 0.729 | 22131 | 0.680 | 32131 | 0.450 |

| 12132 | 0.693 | 22132 | 0.644 | 32132 | 0.414 |

| 12133 | 0.548 | 22133 | 0.499 | 32133 | 0.269 |

| 12211 | 0.903 | 22211 | 0.854 | 32211 | 0.624 |

| 12212 | 0.867 | 22212 | 0.818 | 32212 | 0.588 |

| 12213 | 0.722 | 22213 | 0.673 | 32213 | 0.443 |

| 12221 | 0.868 | 22221 | 0.819 | 32221 | 0.589 |

| 12222 | 0.832 | 22222 | 0.783 | 32222 | 0.553 |

| 12223 | 0.687 | 22223 | 0.638 | 32223 | 0.408 |

| 12231 | 0.689 | 22231 | 0.640 | 32231 | 0.410 |

| 12232 | 0.653 | 22232 | 0.604 | 32232 | 0.374 |

| 12233 | 0.508 | 22233 | 0.459 | 32233 | 0.229 |

| 12311 | 0.663 | 22311 | 0.614 | 32311 | 0.384 |

| 12312 | 0.627 | 22312 | 0.578 | 32312 | 0.348 |

| 12313 | 0.482 | 22313 | 0.433 | 32313 | 0.203 |

| 12321 | 0.628 | 22321 | 0.579 | 32321 | 0.349 |

| 12322 | 0.592 | 22322 | 0.543 | 32322 | 0.313 |

| 12323 | 0.447 | 22323 | 0.398 | 32323 | 0.168 |

| 12331 | 0.449 | 22331 | 0.400 | 32331 | 0.170 |

| 12332 | 0.413 | 22332 | 0.364 | 32332 | 0.134 |

| 12333 | 0.268 | 22333 | 0.219 | 32333 | -0.011 |

| 13111 | 0.783 | 23111 | 0.734 | 33111 | 0.504 |

| 13112 | 0.747 | 23112 | 0.698 | 33112 | 0.468 |

| 13113 | 0.602 | 23113 | 0.553 | 33113 | 0.323 |

| 13121 | 0.748 | 23121 | 0.699 | 33121 | 0.469 |

| 13122 | 0.712 | 23122 | 0.663 | 33122 | 0.433 |

| 13123 | 0.567 | 23123 | 0.518 | 33123 | 0.288 |

| 13131 | 0.569 | 23131 | 0.520 | 33131 | 0.290 |

| 13132 | 0.533 | 23132 | 0.484 | 33132 | 0.254 |

| 13133 | 0.388 | 23133 | 0.339 | 33133 | 0.109 |

| 13211 | 0.743 | 23211 | 0.694 | 33211 | 0.464 |

| 13212 | 0.707 | 23212 | 0.658 | 33212 | 0.428 |

| 13213 | 0.562 | 23213 | 0.513 | 33213 | 0.283 |

| 13221 | 0.708 | 23221 | 0.659 | 33221 | 0.429 |

| 13222 | 0.672 | 23222 | 0.623 | 33222 | 0.393 |

| 13223 | 0.527 | 23223 | 0.478 | 33223 | 0.248 |

| 13231 | 0.529 | 23231 | 0.480 | 33231 | 0.250 |

| 13232 | 0.493 | 23232 | 0.444 | 33232 | 0.214 |

| 13233 | 0.348 | 23233 | 0.299 | 33233 | 0.069 |

| 13311 | 0.503 | 23311 | 0.454 | 33311 | 0.224 |

| 13312 | 0.467 | 23312 | 0.418 | 33312 | 0.188 |

| 13313 | 0.322 | 23313 | 0.273 | 33313 | 0.043 |

| 13321 | 0.468 | 23321 | 0.419 | 33321 | 0.189 |

| 13322 | 0.432 | 23322 | 0.383 | 33322 | 0.153 |

| 13323 | 0.287 | 23323 | 0.238 | 33323 | 0.008 |

| 13331 | 0.289 | 23331 | 0.240 | 33331 | 0.010 |

| 13332 | 0.253 | 23332 | 0.204 | 33332 | − 0.026 |

| 13333 | 0.108 | 23333 | 0.059 | 33333 | − 0.171 |

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The following authors are members of the EuroQol Research Foundation (the copyright holders of EQ-5D-5L): NYG, BR and FDP. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Funding

We acknowledge the study was funded by EuroQol group grant number EQ project 20180660. However, the publication of study results was not contingent on the sponsor’s approval or censorship of the manuscript.

Authors contributions

NYG and MM contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was completed by MM and AH. Quality Control check was done by FDP. Analysis was performed by BR & FDP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MM, NYG, BR and FDP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Research Committee [Hamdard University Health Research Ethics Committee (no: HREC, HUIC-091/2019 )].

Consent to participate

All respondents provided written informed consent prior to the study.

Consent for publication

All respondents provided written informed consent for publication.

Code availability

Not Applicable

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are avail-able from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy-Martin M, Slaap B, Herdman M, van Reenen M, Kennedy-Martin T, Greiner W, Busschbach J, Boye KS. Which multi-attribute utility instruments are recommended for use in cost-utility analysis? A review of national health technology assessment (HTA) guidelines. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(8):1245–1257. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01195-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rencz F, Gulácsi L, Drummond M, Golicki D, Prevolnik Rupel V, Simon J, Stolk EA, Brodszky V, Baji P, Závada J, Petrova G, Rotar A, Péntek M. EQ-5D in Central and Eastern Europe: 2000–2015. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(11):2693–2710. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur G, et al. Criteria used for priority-setting for public health resource allocation in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35(6):474–483. doi: 10.1017/S0266462319000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarn Y-H, et al. Health-care systems and pharmacoeconomic research in Asia-Pacific region. Value Health. 2008;11:S137–S155. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik MA, Iqbal SP, Abrejo F. Nature, scope and use of economic evaluation of healthcare programmes: with special reference to Pakistan. JPMA. 2017;67(5):773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehman GU, Shi H. ABO and Rh (D) blood groups distribution in Pakistan: a systematic review. Forensic Res Criminol Int J. 2020;8:237–244. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaikh BT, et al. Resource allocation in Pakistan's health sector: a critical appraisal and a path toward the Millennium Development Goals. World Health Popul. 2013;14(3):22–31. doi: 10.12927/whp.2013.23438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pattanaphesaj J, et al. The EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Thailand. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(5):551–558. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2018.1494574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devlin NJ, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5 D-5 L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7–22. doi: 10.1002/hec.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malik M, et al. A pilot study of valuation methods of the EQ-5D and the impact of literacy, cultural and religious factors on preferences. Value Health Reg Issues. 2022;30:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stolk E, Ludwig K, Rand K, van Hout B, Ramos-Goñi JM. Overview, update, and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2019;22(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stolk EA, et al. Discrete choice modeling for the quantification of health states: the case of the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2010;13(8):1005–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen BM, et al. Introducing the composite time trade-off: a test of feasibility and face validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(Suppl 1):S5–13. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan KKW, Pullenayegum EM. The theoretical relationship between sample size and expected predictive precision for EQ-5D valuation studies: a mathematical exploration and simulation study. Med Decis Mak. 2020;40:339–347. doi: 10.1177/0272989x20915452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen TM, Stavem K, Rand K. Sample size and model prediction accuracy in EQ-5D-5L valuations studies: expected out-of-sample accuracy based on resampling with different sample sizes and alternative model specifications. MDM Policy Pract. 2022;7(1):23814683221083839. doi: 10.1177/23814683221083839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos-Goñi JM, et al. Quality control process for EQ-5D-5L valuation studies. Value Health. 2017;20(3):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos-Goñi JM, et al. Valuation and modeling of EQ-5D-5L health states using a hybrid approach. Medical care. 2017;55(7):e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Omelyanovskiy V, et al. Valuation of the EQ-5D-3L in Russia. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(7):1997–2007. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02804-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khabibullina A, Gerry CJ. Valuing health states in Russia: a first feasibility study. Value Health Reg Issues. 2019;19:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yusof FA, Goh A, Azmi S. Estimating an EQ-5D value set for Malaysia using time trade-off and visual analogue scale methods. Value Health. 2012;15(1 Suppl):S85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chemli J, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life using a hybrid approach: Tunisian value set for the EQ-5D-3L. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(5):1445–1455. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02730-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leidl R, Reitmeir P. An experience-based value set for the EQ-5D-5L in Germany. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1150–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo N, et al. Valuation of EQ-5D-3L health states in Singapore: modeling of time trade-off values for 80 empirically observed health states. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(5):495–507. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prevolnik Rupel V, Srakar A, Rand K. Valuation of EQ-5D-3l health states in Slovenia: VAS based and TTO based value sets. Zdr Varst. 2020;59(1):8–17. doi: 10.2478/sjph-2020-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rencz F, et al. Parallel valuation of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L by time trade-off in Hungary. Value Health. 2020;23(9):1235–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhuo L, et al. Time trade-off value set for EQ-5D-3L based on a nationally representative Chinese population survey. Value Health. 2018;21(11):1330–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.04.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Z, et al. Selecting health states for EQ-5D-3L valuation studies: statistical considerations matter. Value Health. 2018;21(4):456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are avail-able from the corresponding author on reasonable request.