Young Black American gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (YB-GBMSM) are more likely to experience socioeconomic instability in comparison to their White or heterosexual counterparts (Ouafik et al., 2022). This disparity can be attributed to the unequal distribution of resources related to their intersectional experiences of racism, heterosexism, and classism, which synergistically converge to undermine health and well-being (Bowleg et al., 2017). For example, lack of financial support from non-sexual orientation affirming parents/caregivers during late adolescence may increase YB-GBMSM’s risk of socioeconomic instability in early adulthood by restricting youth’s access to readily available resources, such as housing (Ecker et al., 2019). Such restrictions precipitate negative outcomes, including homelessness and food insecurity, that carry forward to undermine the young adult’s development and transition to middle adulthood (McCann & Brown, 2019).

Socioeconomic Instability

Socioeconomic instability, i.e., uncontrolled socioeconomic fluctuations faced by an individual, has become recognized as a key contributor to the HIV pandemic worldwide and is an important antecedent of poor health outcomes among YB-GBMSM (Weiser et al., 2009). Specifically, socioeconomic instability has been linked with weight loss and malnutrition, suboptimal virologic response to antiretroviral therapy, and even increased mortality (Calmy et al., 2006; Campa et al., 2005). Despite such risks, few studies have examined how indicators of socioeconomic instability are associated with health disparities among YB-GBMSM. Homelessness, i.e., the state of not having a secure and lasting home, usually leading individuals, or families to reside in insufficient or temporary places like shelters, vehicles, or public spaces, has been implicated as a saliant antecedent to HIV-care disruption (Palar et al., 2015; Rajabiun et al., 2020). Previous studies indicate that YB-GBMSM who experience homelessness have elevated levels of lifetime and current drug use and are more prone to using substances such as crack cocaine, heroin, and injectable drugs compared to their counterparts who have stable housing (Clatts et al., 2005a, 2005b). Additionally, food insecurity, i. e. limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, has been shown to be directly related to HIV-care retention, medication adherence, and viral load suppression (Palar et al., 2015; Rajabiun et al., 2020). Emerging qualitative research conducted among individuals in the United States indicates that insufficient access to food may play a role in engaging in unprotected transactional sex among men, including both those who identify as homosexual and heterosexual (Whittle et al., 2015). In addition to sexual behavior, pathways such as the use of injected drugs can further connect food insecurity to the risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV (Anema et al., 2010; Strike et al., 2012). In addition to their direct health effects, emerging research indicates that homelessness and food insecurity may initiate an indirect cascade of behavioral processes that encourages illicit substance use among YB-GBMSM.

Methamphetamine (meth) Use

YB-GBMSM experiencing socioeconomic instability may be at a heightened risk of substance use, particularly meth use. Rates of meth use among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) are estimated to be up to twenty times higher than the general population (Reback et al., 2012). Although YB-GBMSM have historically reported lower rates of meth use than White GBMSM (Grov et al., 2006), emerging data documents sharp increases in meth use among YB-GBMSM in recent years (Rivera et al., 2021, pp. 2004–2017). Two surveillance studies conducted in New York City and Washington, DC have investigated this topic, and revealed decreasing prevalence of meth use among White GBMSM but increasing prevalence among YB-GBMSM (Rivera et al., 2021). Furthermore, exploratory qualitative studies in Texas (Maiorana et al., 2021), Los Angeles (Cassels et al., 2020), and Atlanta (Hussen et al., 2021), support these findings, documenting increasing salience of meth in community narratives of YB-GBMSM. Living in metropolitan areas may impose financial burdens onto an already disadvantaged population resulting in instabilities concerning their housing and food access. Prior research has demonstrated that Black Americans and sexual minorities are overrepresented in homeless populations (Coady et al., 2007; Gomez et al., 2010; National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2021; Rachlis et al., 2009). Additional, national surveillance data indicates that young adults who identify as both Black and LGBTQ are more than twice as likely to experience homelessness in comparison to their White heterosexual and LGBTQ peers (Page, 2017). Ongoing research suggests that the stress associated with experiencing housing and food insecurity produces significant levels of psychological distress (Green et al., 2012; Hurd et al., 2014). Consequently, individuals experiencing these stressors may use meth to cope with the strain of their circumstances (Hussen et al., 2021; Marshall et al., 2011). Despite a confluence of data pointing to an association between socioeconomic instability and meth use among YB-GBMSM, research in this area is relatively scarce, and the mechanisms linking indicators of socioeconomic instability to meth use among YB-GBMSM remain incompletely understood.

Survival Sex

Survival sex may be a potential mediator of the association between housing and food insecurity and meth use among YB-GBMSM. Survival sex refers to the act of engaging in sexual behaviors in exchange for housing, material goods such as food, or to meet basic needs (Chettiar et al., 2010). While the exchange of money for sexual behaviors is not explicitly excluded from contemporary definitions of survival sex, the term is often reserved for exchanges that do not include monetary compensation, but instead basic survival needs such as food, a place to sleep, or to avoid violence (Chettiar et al., 2010). Lack of access to voluntary and low-threshold services, including affordable housing and shelter options, livable-wage employment opportunities, and food security, are major driving forces behind engaging in survival sex for YB-GBMSM (Aidala et al., 2005; Dank et al., 2015).

Even when trying to access social support services, YB-GBMSM report high rates of service denial, as well as breach of confidentiality and unsafe and discriminatory treatment by staff and other recipients of these services, based on their racial identity, sexual orientation, gender expression, and age (Dennis, 2008). As a result of these disappointing or frustrating experiences with social service systems and providers, many YB-GBMSM turn to survival sex to meet their basic subsistence needs (Dank et al., 2015). As such, we hypothesize that increased exposure to homelessness and food insecurity would predict increased engagement in acts of survival sex.

Significant relationships between survival sex and substance use have been demonstrated in the general population of young adults experiencing homelessness (Chettiar et al., 2010). While current quantitative research on the topic is largely correlational, qualitative narratives of homelessness and survival sex-involved young adults who engage in substance use indicate that they use substances to cope with or escape the harsh, oppressive environment that confronts them and the stress associated with trading sex for goods and services (Johnson & Chamberlain, 2008). In accordance with prior formative qualitative research (Hussen et al., 2021), we hypothesize that increased engagement in survival sex would be associated with increased meth use.

The Current Study

Despite evidence of a positive association between indicators of socioeconomic instability (i. e. homelessness and food insecurity) and meth use among YB-GBMSM, research in this area is scarce. In this study, we test our hypotheses that indicators of socioeconomic instability, including homelessness and food insecurity, would directly, and indirectly, predict increases in meth use, via increased survival sex engagement.

Methods

Recruitment

We conducted in-person recruitment and eligibility screening at a partnering HIV clinic, a substance-use-focused organization offering housing services, and various community events located in the Atlanta metropolitan area. At these venues, study staff approached potential participants, described the study, and then directed them to link to an online eligibility screening survey using either a study device or the participants’ smartphones. We also advertised with paper and electronic flyers; the latter was distributed using social media and on a geosocial networking app frequently used by YB-GBMSM. From either paper or electronic flyers, participants could self-refer to a screening survey. Once eligibility was confirmed, study staff contacted potential participants and scheduled a date and time to conduct the cross-sectional survey study.

Participants

Participants included 100 YB-GBMSM currently experiencing homelessness. For this study, homelessness was defined as either one or more moves in the last six months, self-reported homelessness within the last six months, or endorsing fear or worry about impending homelessness. Additional inclusion criteria included self-reporting as (1) Black/African American race; (2) male gender identity; (3) gay, bisexual, or other non-heterosexual orientation OR report sexual partnerships with cisgender men; and (4) age 18–34 years.

Data collection procedures

All surveys were conducted via Zoom videoconference technology and administered by trained study staff. Team members obtained verbal informed consent at the beginning of each Zoom call. Survey items were shared on a screen and read aloud by study staff to maximize comprehension by the participant. Study staff entered responses, given verbally by participants, into a secure, HIPAA-compliant REDCap online database. Each survey took approximately 45 minutes to complete. Participants received a $50 electronic gift card upon completion of the interview. The Emory University’s Institutional Review Board and Grady Research Oversight Committee approved the study protocol and ethics under protocol number #00117528.

Measures

Meth Use.

Meth use was measured using six items adapted from the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST; WHO ASSIST Working Group, 2002). Items assessed participants’ experiences of meth-related (a) usage, (b) desire, (c) health, social, or financial-related problems, (d) inability to preform duties or tasks that were typically expected from them because of their usage, (e) friend/relative/anyone expressing concern over their usage, and (f) failure to control, cut down, or stop using. Example items include, “has a friend or relative or anyone else ever expressed concern about your use of the following drugs”, and “have you ever tried and failed to control, cut down or stop using the following drugs”. Response options included: 1 (no/never), 2 (yes-in the past 3 months), and 3 (yes, but not in the past 3 months). Items were summed to produce a total meth use sum score where higher scores correspond to higher levels of meth use. Reliability of the measure was good in our sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .84).

Survival Sex Engagement.

Participants were asked to report their engagement in survival sex with casual partners across four indicators of socioeconomic need (Dunkle et al., 2010): “I have had sex with someone who was NOT a regular partner because I needed help...: (1) “paying for things that I couldn’t afford by myself,” (2) “having a place to live,” (3) “paying for groceries, utilities, or other bills,” and (4) “providing for some-one else who depends on me for financial support.” Each statement could be answered on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (False) to 3 (True). Items were summed to produce a total survival sex sum score where higher scores were indicative of greater endorsement of survival sex with a casual partner. Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Food Insecurity.

Participants were asked to complete the six-item Food Security Scale developed by researchers at the National Center for Health Statistics (Blumberg et al., 1999). The scale is comprised of 4 Likert scale questions such as “In the last 12 months, the food that I bought just didn’t last and I didn’t have money to get more” with response options ranging from 0 (Never true) to 2 (Often true) and 2 yes/no questions including “In the last 12 months, did you ever eat less than you felt you should because there wasn’t enough money for food?” Items were summed to produce a total food insecurity sum score where higher scores correspond to higher levels of food insecurity. Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

Homelessness.

Homelessness was measured using a single item (yes/no) asking participants to report if had ever been homeless at any time in the last 12 months.

Age.

Participants self-reported their chronological age in years at the time of the study.

Sexual Orientation.

Participants self-reported their identified sexual orientation. Response options included: (1) gay/homosexual/same gender loving, (2) bisexual, and (3) other/not listed.

Employment Status.

Participants self-reported their current employment status. Response options included: (0) employed/full time, or (1) unemployed.

HIV Status.

Participants self-reported their current HIV status. Response options included: (0) negative/seronegative, or (1) positive/seropositive.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlations were analyzed using SPSS v28. Exploratory hypotheses were tested using mediated path analysis in Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). Although there was no missing data, statistical models were constructed using the full information maximum likelihood estimator to produce unbiased estimated standard errors (Little & Rubin, 2019). The significance of indirect effects was evaluated with bootstrapping analyses with 5,000 bootstrapping resamples to produce 95% confidence intervals (CIs; Bollen & Stine, 1990). These intervals take into account possible non-symmetry in the distribution of estimates, which can bias p-values (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013); we thus relied upon the 95% CIs when determining the significance of indirect effects. This study used comparative fit index (CFI) values greater than or equal to .90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values less than or equal to .08 as being indicative of well-fitting models (Kline, 2015). The chi-square test of model fit (c2) estimates was also reported for completeness.

Results

Participants

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample. Participants’ mean age was 28.40 years (standard deviation (SD) = 4.17 years). The majority of YB-GBMSM who participated in this study identified as gay/homosexual/same gender loving (81%), were living with HIV (80%), had completed some college, technical school, or vocation school (30%), were employed full time (41%), made less than $10,000 annually (34%), and did not have health insurance (49%). 43% of participants reported experiencing homelessness in the last 12 months. 64% of participants reported having experienced at least minimal forms food insecurity in the last 12 months.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | Total (N = 100) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Gay/homosexual/same gender loving (SGL) | 84 |

| Bisexual | 16 |

| Education | |

| 9th-11th grade | 5 |

| High School Diploma or GED | 29 |

| Some college, technical school, or vocational school | 30 |

| Technical or vocational school graduate | 3 |

| Two-year college graduate | 11 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 18 |

| Some graduate school | 1 |

| Master’s degree or above | 3 |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 62 |

| Unemployed | 38 |

| Annual Income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 34 |

| $10,000- $19,999 | 15 |

| $20,000- $29,999 | 15 |

| $30,000- $49,999 | 32 |

| $50,000- $99,999 | 2 |

| Greater than $100,000 | 2 |

| Insurance | |

| Yes - I have my own | 46 |

| Yes - I am covered by my parent/guardian | 5 |

| No | 49 |

| HIV Status | |

| Seropositive | 80 |

| Seronegative | 17 |

| Don't know | 3 |

| Homelessness Status (12 months) | |

| Yes | 43 |

| No | 57 |

| Food Insecurity | |

| 0 | 36 |

| 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 6 |

| 4 | 14 |

| 5 | 21 |

| 6 | 6 |

| 7 | 7 |

Preliminary Analysis

Table 2 provides the bivariate correlations among study variables, including covariates. Study variables were correlated in the predicted direction. Meth use was positively associated with engaging in survival sex (r = .39, p < .05), homelessness (r = .37, p <.05), and age (r = .35, p < .05). Additionally, engaging in survival sex was positively associated with food insecurity (r = .41, p < .01), homelessness (r = .32, p < .01), and living with HIV (r = .24, p < .05).

Table 2.

Two-Tailed Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meth Use | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | Survival Sex Engagement | .39* | 1 | |||||

| 3 | Food Insecurity | .15 | .41** | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Homelessness Status | .37* | .32** | .26** | 1 | |||

| 5 | Age | .35* | .18 | .07 | .04 | 1 | ||

| 6 | Sexual Orientation | −.09 | −.01 | −.11 | .01 | .01 | 1 | |

| 7 | Employment Status | .30 | .13 | .11 | .24* | −.02 | .11 | 1 |

| M | 12.69 | 2.17 | 4.80 | .43 | 28.40 | 1.16 | .38 | |

| SD | 5.12 | 3.56 | 2.47 | .50 | 4.17 | .37 | .49 |

Note. M = mean, SD = standard deviation,

p <.05;

p<.01.

Indirect Effects Model

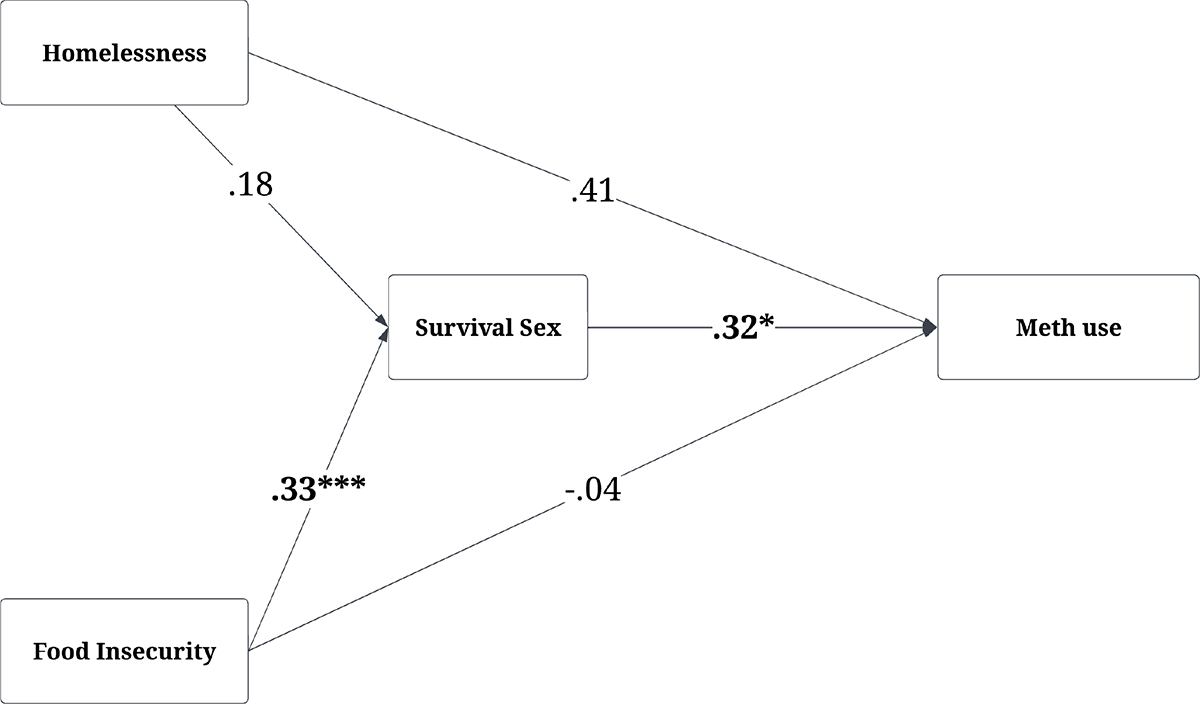

The model fit the data as follows: χ2(5) = .58, p = .99; RMSEA = .00, and CFI = 1.00 (see Figure 1). Food insecurity (b = .47, p < .001, 95% CI = .21, .74) was positively associated with greater endorsement of survival sex with a casual partner. While the p-value for the association between housing insecurity and survival sex was insignificant, results of the CI 95% indicated that the association trended towards significance (b = 1.29, p = .057, 95% CI = .00, 2.69). Increased acts of survival sex (b = .50, p < .05, 95% CI = .01, .97) were positively associated with increased meth use. The indirect effects of food insecurity on meth use via survival sex engagement were significant (bind = .24, 95% CI = .03, .59). The indirect effects of food insecurity on meth use via acts of survival sex were also significant (bind = .25, 95% CI = .03, .61).

Figure 1. Standarized indirect effects model illustrating the mediating effects of survival sex on the associations between homelessness, food insecurity and meth use.

Note. Significant coefficients are bolded; *p < .05, *** p <.001; endogenous correlations and covariates (i.e. age, sexual orientation, employment status, and HIV status) not displayed.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the degree to which indicators of socioeconomic instability, including homelessness and food insecurity, would directly, and indirectly, predict increases in meth use, via increased survival sex engagement. We found that food insecurity was directly associated with increased survival sex engagement but was not directly associated with meth use. Despite the lack of a direct association between indicators of socioeconomic instability and meth use, the results of our indirect effects analysis indicated that food insecurity was indirectly associated with increased in meth use, via increased engagement in survival sex. Our findings suggest that socioeconomic instability and survival sex engagement may be important targets for future meth intervention/prevention programming. The findings reported here shed new light on the contextual mechanisms that link experiences of food insecurity to meth use among YB-GBMSM.

Preliminary analysis results demonstrated positive associations between engaging in survival sex, food insecurity, homelessness, and living with HIV. These findings align with prior research indicating that living with HIV can lead to significant financial burdens (Rajabiun et al., 2020; Weiser et al., 2009). For instance, people living with HIV may experience symptoms and health complications that affect their ability to work resulting in a loss of income or gainful employment (Palar et al., 2015; Rajabiun et al., 2020). Additionally, medical expenses, the cost of antiretroviral medications, and the inability to work due to health issues can result in economic hardship (Palar et al., 2015; Weiser et al., 2009). Engaging in survival sex may be viewed to secure the necessary resources for survival; however, few studies have examined the prevalence or experience of engaging in survival sex while living with HIV. Further research on the complex relationship between living with HIV, indicators of socioeconomic instability, and survival sex is warranted.

Congruent with prior literature, our findings suggest that socioeconomic instabilities, such as food insecurity, cultivate unique areas of vulnerability that constrain individuals’ survival choices and initiate a cascade of processes that undermine YB-GBMSM’s health. While numerous studies have documented strong linkages between homelessness and survival sex engagement (Greene et al., 1999; McMillan et al., 2018; Moton et al., 2022; Riley et al., 2007), a relatively small body of literature has been dedicated to examining the association between food insecurity and survival sex engagement. Our findings align with emerging literature indicating that food insecurity is one of many reasons why individuals may engage in survival sex, which in turn can increase exposure to numerous health outcomes including sexual risk (Curtis & Boe, 2023), nutrition (Van der Sande et al., 2004), and physical and mental health (Almeida-Brasil et al., 2018). For example, YB-GBMSM who are food insecure and engaging in survival sex may experience constraints to their agency in effectively negotiating condom use, leading them to agree to sex without a condom or engage in chemsex (i. e. engaging in sexual activity under the influence of mind-altering substances) for higher pay (Brooks-Gordon & Ebbitt, 2021; Curtis & Boe, 2023). When an individual is experiencing poverty and is dependent upon trading sex for survival, their ability to resist the misuse of illicit substances may be overshadowed by the more immediate need to obtain money, food, or a place to sleep (Lichtenstein, 2005). In addition, an individual’s financial dependence on their partner, either in a relationship or during survival sex, may result in substance use decisions that are dictated by their partner rather than arrived at by mutual agreement (Lichtenstein, 2005).

An extensive body of literature suggest that the socioeconomic stability of individuals engaging in sex trading influences their capacity to control negotiating sex work transactions, including the capacity to refuse unwanted services, negotiate condom use, and avoid violent perpetrators (Drückler et al., 2020; Nowotny et al., 2017). Indeed, Galárraga et al (2014) found that male sex traders were able to get paid higher prices by their clients if they were willing to engage in riskier behaviors, such as meth use, during the exchange as these behaviors are often believed to enhance the experience. As such, meth use may become an occupational health risk that progresses with men’s involvement in survival sex (Chettiar et al., 2010). As men become further entrenched in sex trading, their reliance on substances may intensify. This includes the ritualistic process of engaging a client that is centered around the use of meth. In a high-profile example of this phenomenon, a businessman and political donor, Ed Buck, was convicted in 2021 of supplying and personally injecting two Black GBMSM sex workers, Gemmel Moore and Timothy Dean, with meth as a part of exchange sex, leading to their deaths (Wilson, 2020). During the trial, it was disclosed that Buck had a long history of employing male Black sex workers for similar “party and play” encounters at his West Hollywood apartment, where meth use was a salient component of the sexual encounter (Zaveri, 2019). Dane Brown, a Black GBMSM sex worker who had frequent encounters with Buck, described how Buck injected him with overdoses of meth (Anguiano, 2022). Yet, even after being hospitalized for the first incident, Brown, who was homeless at the time, later returned to Buck’s home due to the tangible supports Buck offered – e. g., housing (Brooks, 2020). In accordance with this real-world anecdote, our results indicate that men experiencing socioeconomic instability, and its related effects, may be more likely to engage in survival sex, which may carry forward to increase their risk of meth use. Furthermore, our findings highlight the need for structural interventions that target YB-GBMSM’s experiences of socioeconomic instability by expanding opportunities in the legitimate economy to meet their financial survival needs to improve their long-term health trajectories.

Limitations

The present study was subject to a few potential methodological weaknesses. A principal limitation of this study was its use of a one question measure of homelessness. Many men may not consider themselves to be strictly “homeless” but may instead experience bouts of greater or lesser homelessness. Future research examining the nuanced presentation of homelessness and housing instability is needed. Furthermore, this study used a nonprobability and cross-sectional sampling strategy, which limits our ability to generalize findings to broader populations or draw causal conclusions. While our analysis examined the degree to which engaging in survival sex forecasted meth use, we acknowledge that a bidirectional association between these factors may exist in that some participants may have been exposed to survival sex because of their pre-existing meth use. Future longitudinal research could shed light on the directionality of this association. The study also implemented a retrospective self-report data collection strategy, which presents a risk for recall and social desirability biases.

Conclusion

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the influence of indicators of socioeconomic instability and survival sex on YB-GBMSM ‘s meth use. As predicted, homelessness and food insecurity were directly associated with increased survival sex engagement, which carried forward to be directly associated with increases in meth use. Findings underscore the role of socioeconomic instability in initiating an indirect cascade of behavioral processes that increase risk for meth use among YB-GBMSM. These insights may be used by prevention scientists and policymakers to enhance intervention programs aimed at addressing meth use among YB-GBMSM, particularly those individuals living with HIV.

Table 3.

Unstandardized results of the indirect effects model illustrating the associations between housing instability, food insecurity, survival sex engagement, and meth use

| 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictor | b | SE | p | Lower | Upper |

|

| ||||||

| Survival Sex Engagement | ||||||

| Food Insecurity | .47*** | .133 | .000 | .208 | .737 | |

| Homelessness Status | 1.29 | .679 | .057 | −.002 | 2.688 | |

| Age | .12 | .068 | .066 | −.009 | .259 | |

| Sexual Orientation | .18 | .675 | .795 | −1.252 | 1.419 | |

| Employment | .19 | .670 | .773 | −1.103 | 1.510 | |

| HIV Status | −1.20** | .451 | .008 | −2.129 | −.347 | |

| Meth(amphetamine) Use | ||||||

| Food Insecurity | −.08 | .444 | .851 | −.933 | .826 | |

| Homelessness Status | 4.48 | 2.340 | .055 | −.606 | 8.364 | |

| Engaging in Survival Sex | .50* | .246 | .041 | .009 | .971 | |

| Age | .18 | .258 | .479 | −.338 | .694 | |

| Sexual Orientation | −.50 | 2.125 | .816 | −4.895 | 3.654 | |

| Employment | 3.21 | 1.957 | .101 | −.635 | 6.986 | |

Note. b = unstandardized beta, SE=standard error, p = p-value,

p <.05;

p <.01;

p<.001, 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals.

Key Considerations.

Socioeconomic instability and methamphetamine use is a major disruptor of young adult Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men living with HIV’s ability to maintain their biopsychosocial health and wellbeing.

Engagement in survival sex is one pathway through which socioeconomic instability promotes methamphetamine use and erodes men’s health.

Engagement in survival sex due to socioeconomic instability may reduce men’s ability to negotiate their sexual safety (e. g. the use of condoms during intercourse).

Our findings highlight the need for structural interventions that target YB-GBMSM’s experiences of socioeconomic instability by expanding opportunities in the legitimate economy to meet their financial survival needs to improve their long-term health trajectories.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under Award Number T32AI157855 and the Emory Center for AIDS Research P30AI050409. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The analysis presented was not disseminated prior to the creation of this article.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no real or perceived vested interest related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, Harre D, & Sumartojo E (2005). Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: Implications for prevention and policy. AIDS and Behavior, 9, 251–265. 10.1007/s10461-005-9000-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Brasil CC, Moodie EE, McLinden T, Hamelin A-M, Walmsley SL, Rourke SB, Wong A, Klein MB, & Cox J (2018). Medication nonadherence, multitablet regimens, and food insecurity are key experiences in the pathway to incomplete HIV suppression. Aids, 32(10), 1323–1332. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anema A, Wood E, Weiser SD, Qi J, Montaner JS, & Kerr T (2010). Hunger and associated harms among injection drug users in an urban Canadian setting. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 5, 1–7. 10.1186/1747-597X-5-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguiano D (2022). Wealthy donor Ed Buck gets 30 years in prison for drugging gay men, two fatally. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/apr/14/ed-buck-sentenced-political-activist-methamphetamine-deaths

- Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, & Briefel R (1999). Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form Economic Research Service, USDA. United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf

- Bollen KA, & Stine R (1990). Direct and Indirect Effects: Classical and Bootstrap Estimates of Variability. Sociological Methodology, 20, 115–140. 10.2307/271084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Del Rio-Gonzalez AM, Holt SL, Perez C, Massie JS, Mandell JE, & Boone C A (2017). Intersectional Epistemologies of Ignorance: How Behavioral and Social Science Research Shapes What We Know, Think We Know, and Don’t Know About U.S. Black Men’s Sexualities. J Sex Res, 54(4–5), 577–603. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1295300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S (2020). Everyday Violence Against Black and Latinx LGBT Communities. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gordon B, & Ebbitt E (2021). The Chemsex ‘Consent Ladder’ in Male Sex Work: Perspectives of Health Providers on Derailment and Empowerment. Social Sciences, 10(2). 10.3390/socsci10020069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calmy A, Pinoges L, Szumilin E, Zachariah R, Ford N, & Ferradini L (2006). Generic fixed-dose combination antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: Multicentric observational cohort. Aids, 20(8), 1163–1169. 10.1097/01.aids.0000226957.79847.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campa A, Zhifang Y, Lai S, Xue L, Phillips JC, Sales S, Page JB, & Baum MK (2005). HIV-related wasting in HIV-infected drug users in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 41(8), 1179–1185. 10.1086/444499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassels S, Meltzer D, Loustalot C, Ragsdale A, Shoptaw S, & Gorbach PM (2020). Geographic mobility, place attachment, and the changing geography of sex among African American and Latinx MSM who use substances in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Health, 97(5), 609–622. 10.1007/s11524-020-00481-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chettiar J, Shannon K, Wood E, Zhang R, & Kerr T (2010). Survival sex work involvement among street-involved youth who use drugs in a Canadian setting. Journal of Public Health, 32(3), 322–327. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, & Yi H (2005a). Club drug use among young men who have sex with men in NYC: a preliminary epidemiological profile. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(9–10), 1317–1330. 10.1081/JA-200066898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, & Yi H (2005b). Drug and sexual risk in four men who have sex with men populations: Evidence for a sustained HIV epidemic in New York City. Journal of Urban Health, 82, i9–i17. 10.1093/jurban/jti019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coady MH, Latka MH, Thiede H, Golub ET, Ouellet L, Hudson SM, Kapadia F, & Garfein RS (2007). Housing status and associated differences in HIV risk behaviors among young injection drug users (IDUs). AIDS and Behavior, 11, 854–863. 10.1007/s10461-007-9248-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MG, & Boe JL (2023). The Lived Experiences of Male Sex Workers: A Global Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Sexes, 4(2), 222–255. 10.3390/sexes4020016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dank M, Yahner J, Madden K, Bañuelos I, Yu L, Ritchie A, Mora M, & Conner BM (2015). Surviving the streets of New York: Experiences of LGBTQ youth, YMSM, and YWSW engaged in survival sex. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/surviving-streets-new-york-experiences-lgbtq-youth-ymsm-and-ywsw-engaged-survival-sex

- Dennis JP (2008). Women are victims, men make choices: The invisibility of men and boys in the global sex trade. Gender Issues, 25(1), 11–25. 10.1007/s12147-008-9051-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drückler S, van Rooijen MS, & de Vries HJ (2020). Substance use and sexual risk behavior among male and transgender women sex workers at the prostitution outreach center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 47(2), 114–121. 10.1097/olq.0000000000001096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Wingood GM, Camp CM, & DiClemente RJ (2010). Economically motivated relationships and transactional sex among unmarried African American and white women: Results from a US national telephone survey. Public Health Reports, 125(4_suppl), 90–100. 10.1177/00333549101250s413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker J, Aubry T, & Sylvestre J (2019). Pathways into homelessness among LGBTQ2S adults. Journal of Homosexuality. 10.1080/00918369.2019.1600902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galárraga O, Sosa-Rubí SG, González A, Badial-Hernández F, Conde-Glez CJ, Juárez-Figueroa L, Bautista-Arredondo S, Kuo C, Operario D, & Mayer KH (2014). The disproportionate burden of HIV and STIs among male sex workers in Mexico City and the rationale for economic incentives to reduce risks. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 19218. 10.7448/ias.17.1.19218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, Thompson SJ, & Barczyk AN (2010). Factors associated with substance use among homeless young adults. Substance Abuse, 31(1), 24–34. 10.1080/08897070903442566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Zebrak KA, Robertson JA, Fothergill KE, & Ensminger ME (2012). Interrelationship of substance use and psychological distress over the life course among a cohort of urban African Americans. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 123(1–3), 239–248. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Ennett ST, & Ringwalt CL (1999). Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1406–1409. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Bimbi DS, Bimbi JE, & Parsons JT (2006). Exploring racial and ethnic differences in recreational drug use among gay and bisexual men in New York City and Los Angeles. Journal of Drug Education, 36(2), 105–123. 10.2190/1G84-ENA1-UAD5-U8VJ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Scharkow M (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927. 10.1177/0956797613480187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2014). Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 50(7), 1910. 10.1037/a0036438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussen SA, Camp DM, Jones MD, Patel SA, Crawford ND, Holland DP, & Cooper HL (2021). Exploring influences on methamphetamine use among Black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Atlanta: A focus group study. International Journal of Drug Policy, 90, 103094. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G, & Chamberlain C (2008). Homelessness and substance abuse: Which comes first? Australian Social Work, 61(4), 342–356. 10.1080/03124070802428191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein B (2005). Domestic violence, sexual ownership, and HIV risk in women in the American deep south. Social Science & Medicine, 60(4), 701–714. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, & Rubin DB (2019). Statistical analysis with missing data (Vol. 793). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Maiorana A, Kegeles SM, Brown S, Williams R, & Arnold EA (2021). Substance use, intimate partner violence, history of incarceration and vulnerability to HIV among young Black men who have sex with men in a Southern US city. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(1), 37–51. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1688395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Wood E, Shoveller JA, Patterson TL, Montaner JSG, & Kerr T (2011). Pathways to HIV risk and vulnerability among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered methamphetamine users: A multi-cohort gender-based analysis. BMC Public Health. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann E, & Brown M (2019). Homelessness among youth who identify as LGBTQ+: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(11–12), 2061–2072. 10.1111/jocn.14818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan K, Worth H, & Rawstorne P (2018). Usage of the terms prostitution, sex work, transactional sex, and survival sex: Their utility in HIV prevention research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(5), 1517–1527. 10.1007/s10508-017-1140-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moton BA, Tawk R, López IA, Malone J, El-Amin Witherspoon S, & Suther SG (2022). Sexual Hookups via Dating Apps: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Experiences of Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in Florida. Florida Public Health Review, 19(1), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus User’s Guide Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2021). The state of homelessness in America. National Alliance to End Homelessness. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness/ [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny KM, Cepeda A, Perdue T, Negi N, & Valdez A (2017). Risk environments and substance use among Mexican female sex work on the US–Mexico border. Journal of Drug Issues, 47(4), 528–542. https://doi.org/10/gbzd42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouafik MR, Buret L, & Scholtes B (2022). Mapping the current knowledge in syndemic research applied to men who have sex with men: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine, 115162. https://doi.org/10/gr3c5k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M (2017). Forgotten youth: Homeless LGBT youth of color and the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act. Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy, 12(2), 17. [Google Scholar]

- Palar K, Kushel M, Frongillo EA, Riley ED, Grede N, Bangsberg D, & Weiser SD (2015). Food insecurity is longitudinally associated with depressive symptoms among homeless and marginally-housed individuals living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 19, 1527–1534. https://doi.org/10/f7mf55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis BS, Wood E, Zhang R, Montaner JS, & Kerr T (2009). High rates of homelessness among a cohort of street-involved youth. Health & Place, 15(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10/dszzk6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajabiun S, Davis-Plourde K, Tinsley M, Quinn EK, Borne D, Maskay MH, Giordano TP, & Cabral HJ (2020). Pathways to housing stability and viral suppression for people living with HIV/AIDS: Findings from the Building a Medical Home for Multiply Diagnosed HIV-positive Homeless Populations initiative. Plos One, 15(10), e0239190. https://doi.org/10/gr3c66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reback CJ, Peck JA, Fletcher JB, Nuno M, & Dierst-Davies R (2012). Lifetime substance use and HIV sexual risk behaviors predict treatment response to contingency management among homeless, substance-dependent MSM. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(2), 166–172. https://doi.org/10/f34g88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley ED, Gandhi M, Bradley Hare C, Cohen J, & Hwang SW (2007). Poverty, unstable housing, and HIV infection among women living in the United States. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 4(4), 181–186. https://doi.org/10/cwp9nb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera AV, Harriman G, Carrillo SA, & Braunstein SL (2021). Trends in methamphetamine use among men who have sex with men in New York City, 2004–2017. AIDS and Behavior, 25(4). https://doi.org/10/gr3dc7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strike C, Rudzinski K, Patterson J, & Millson M (2012). Frequent food insecurity among injection drug users: Correlates and concerns. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1–9. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sande MA, van der Loeff MFS, Aveika AA, Sabally S, Togun T, Sarge-Njie R, Alabi AS, Jaye A, Corrah T, & Whittle HC (2004). Body mass index at time of HIV diagnosis: A strong and independent predictor of survival. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 37(2), 1288–1294. 10.1097/01.qai.0000122708.59121.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles S, Ragland K, Kushel MB, & Frongillo EA (2009). Food insecurity among homeless and marginally housed individuals living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. AIDS and Behavior, 13(5), 841–848. https://doi.org/10/cm69g2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle HJ, Palar K, Napoles T, Hufstedler LL, Ching I, Hecht FM, Frongillo EA, & Weiser SD (2015). Experiences with food insecurity and risky sex among low-income people living with HIV/AIDS in a resource-rich setting. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(1), 20293. 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO ASSIST Working Group. (2002). The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): Development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction, 97(9), 1183–1194. https://doi.org/10/ds8kvm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T (2020). Furtive Blackness: On Blackness and Being. Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, 48, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Zaveri M (2019). 2nd Man Found Dead in Ed Buck’s Home Overdosed on Methamphetamine. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/26/us/ed-buck-methamphetamine-overdose.html