Abstract

The molecular mechanisms underlying diversity in animal behavior are not well understood. A major experimental challenge is determining the contribution of genetic variants that affect neuronal gene expression to differences in behavioral traits. The neuroendocrine TGF-beta ligand, DAF-7, regulates diverse behavioral responses of Caenorhabditis elegans to bacterial food and pathogens. The dynamic neuron-specific expression of daf-7 is modulated by environmental and endogenous bacteria-derived cues. Here, we investigated natural variation in the expression of daf-7 from the ASJ pair of chemosensory neurons and identified common variants in gap-2, encoding a GTPase-Activating Protein homologous to mammalian SynGAP proteins, which modify daf-7 expression cell-non-autonomously and promote exploratory foraging behavior in a DAF-7-dependent manner. Our data connect natural variation in neuron-specific gene expression to differences in behavior and suggest that genetic variation in neuroendocrine signaling pathways mediating host-microbe interactions may give rise to diversity in animal behavior.

Introduction

The molecular characterization of natural variants that affect behavioral traits provides a starting point to understand the cellular and organismal mechanisms driving differences in behavior (1–3). How variation in gene expression might be manifest in differences in behavior has been relatively unexplored in part because the relationship between neuronal gene expression and behavioral states is not well understood. Activity-dependent neuronal transcription has been shown to have pivotal roles in the development and plasticity of neural circuits, but less is known about how changes in gene expression play a role in shaping behavioral states (4). Moreover, whereas variation in levels of gene expression have been readily quantified on a genome-wide scale across evolutionarily diverse organisms in many tissues, including the nervous system, mechanistically bridging changes in levels of gene expression to differences in phenotypic traits has continued to be a major challenge (5–8).

Here, we focused on the characterization of natural variation in the neuron-specific expression levels of a single gene, daf-7, encoding at TGF-beta-related neuroendocrine ligand that regulates diverse aspects of C. elegans physiology (9–14). Neuronal expression of daf-7 is dependent on multiple endogenous and environmental cues (9, 15–18). We have characterized the chemosensory signal transduction pathways involved in the regulation of dynamic daf-7 expression in the ASJ neurons (15, 19). Recently, we characterized how the dynamic expression of DAF-7 in the ASJ neurons functions in a feedback loop that regulates the duration of exploratory roaming behavior in a two-state foraging behavior of C. elegans (20). In the present study, we sought to characterize natural variation in daf-7 ASJ expression in order to test the hypothesis that changes in daf-7 neuroendocrine gene expression could be a determinant of natural variation in behavior of C. elegans, with the anticipation that we might mechanistically connect the variants causing differences in daf-7 expression to differences in DAF-7-dependent behavioral traits

Results

Natural variation in daf-7 expression levels in the ASJ pair of neurons

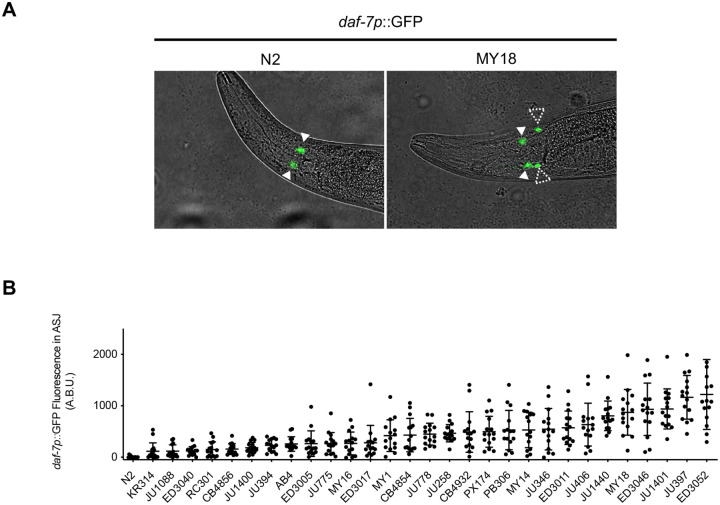

We surveyed a set of wild strains of C. elegans for relative levels of daf-7 expression in the ASJ neurons while feeding on the standard laboratory bacterial food Escherichia coli OP50. Previously, we found that for the laboratory wild-type strain N2 from Bristol, England, hermaphrodites do not exhibit detectable daf-7 expression in ASJ neurons when feeding on E. coli OP50, but we have observed dynamic daf-7 ASJ expression under different conditions, including the observation of daf-7 ASJ expression in N2 hermaphrodites exposed to P. aeruginosa PA14 (15) and in N2 males feeding on E. coli OP50 (16). A genome-wide analysis of whole-animal gene expression levels across wild strains showed variation in daf-7 expression (8). We observed a wide range of expression levels of daf-7 in the ASJ neurons among wild strains sampled, with N2 exhibiting the lowest (undetectable) level of daf-7 ASJ expression (Figs. 1a, b). Our survey was conducted using strains generated from a cross of an integrated transgenic multicopy fluorescent reporter under the control of the daf-7 promoter (derived from the N2 strain) into each wild strain background. Our experimental approach thus precluded the observation of variation in daf-7 expression due to local cis-acting loci because the reporter only had the regulatory regions of the N2 daf-7 gene.

Fig. 1. Natural variation in daf-7 gene expression from the ASJ neurons in wild strains of C. elegans.

(A) daf-7p::GFP expression pattern in N2 (left) and MY18 (right) genetic backgrounds. Filled triangles indicate the ASI neurons; dashed triangles indicate the ASJ neurons. Scale bar, 100μm. (B) Maximum fluorescence values of daf-7p::GFP in the ASJ neurons in the genetic background of indicated wild strains. Each dot represents an individual animal, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

Identification of natural variants in gap-2 modulating daf-7 expression in the ASJ neurons

To define a molecular basis of natural variation in daf-7 ASJ expression, we focused on differences in daf-7 ASJ expression between N2 and MY18, a strain isolated from Münster, Germany. We generated 123 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) from multiple crosses between the N2- and MY18-derived strains (Fig. 2a) and quantified levels of daf-7 ASJ expression in each RIL strain (Fig. 2b). RIL sequencing of MY18 was used to identify 5,716 variants that differed between the two parent strains (N2 and MY18), and a linkage mapping pointed to a broad quantitative trait locus (QTL) on chromosome X that contributed 11.5% of the observed differences in daf-7 ASJ expression (Fig. 2c). In parallel, starting with an MY18-derived strain, we carried out multiple backcrosses with N2, selecting at each generation for the expression of daf-7 ASJ expression, yielding near-isogenic lines (NILs) in the N2 genetic background defining a 447 kb interval on chromosome X: 9,513,008—X: 9,960,248 containing an MY18-derived locus that conferred increased daf-7 ASJ expression in adult hermaphrodites feeding on E. coli OP50 (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. Identification of a genomic locus on chromosome X that affects daf-7 expression in the ASJ neurons.

(A) Diagram for constructing Recombinant Inbred Lines with strains derived from N2 and MY18 backgrounds. (B) Maximum fluorescence values daf-7p::GFP in the ASJ neurons of 123 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) and parental strains derived from N2 and MY18. The color of the bar represents the genotype at the QTL on chromosome X. (C) Linkage mapping results for daf-7p::GFP expression in the ASJ neurons. X-axis tick marks denote every 5 Mb. Significant QTL is denoted by a red triangle at the peak marker, and blue shading shows 95% confidence interval around the peak marker. The 5% genome-wide error rate LOD threshold is represented as a dashed horizontal line. LOD, log of the odds ratio. (D) Maximum fluorescence values daf-7p::GFP in the ASJ neurons of Near-Isogenic Lines (NILs). Each dot represents an individual animal, and error bars indicate standard deviations. ****p<0.0001 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test compared to N2.

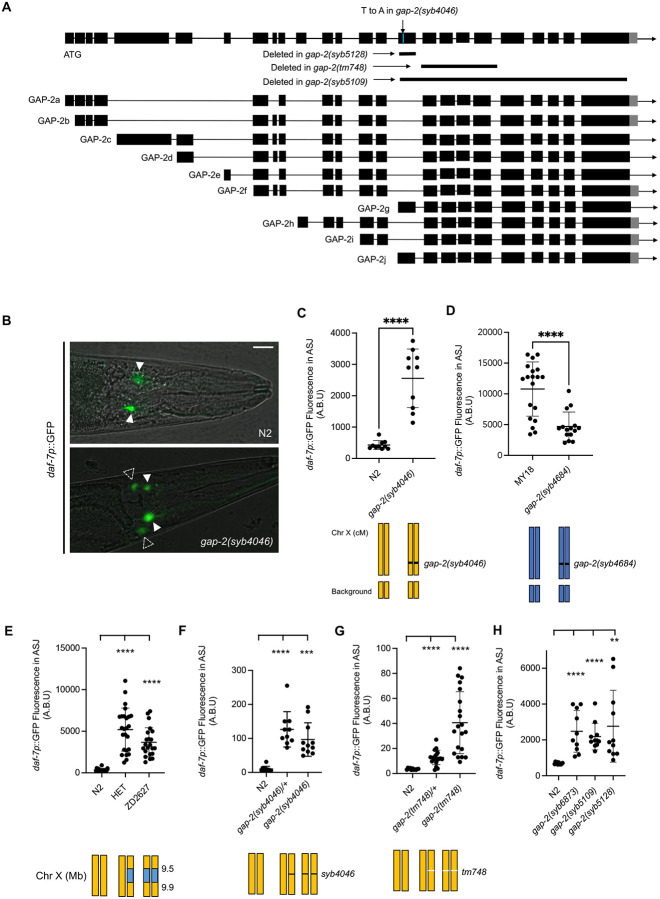

To identify the specific nucleotide differences contributing to the differential daf-7 ASJ expression between the N2 and MY18 strains, we adopted a candidate variant approach, examining nucleotide differences predicted to cause coding changes in the 18 genes present in the narrowed interval on chromosome X. One of these genes was gap-2, encoding a conserved Ras GTPase-Activating-Protein (RasGAP) homologous to the SynGAP family. We identified a candidate variant present in MY18 that was predicted to affect an exon specific to two of the alternatively spliced isoforms of gap-2, gap-2g and gap-2j, and cause a putative substitution of a threonine in place of the serine at position 64 of GAP-2g and GAP-2j. First, we observed that a strain carrying the gap-2(tm748) deletion allele in the N2 background exhibited upregulated daf-7 ASJ expression in adult hermaphrodite animals feeding on E. coli OP50 (Fig. 3g), leading us to evaluate the effect of the 64T variant in the N2 background. We observed that a strain carrying the gap-2(syb4046) allele, which had been engineered to carry the S64T change in the g/j isoforms of gap-2 in the N2 genetic background, exhibited increased daf-7 ASJ expression on E. coli OP50 (Fig. 3b, c). Conversely, when we examined the effect of engineering the 64S reciprocal change into the MY18 genetic background, we observed that daf-7 ASJ expression decreased compared to what was observed in the MY18 strain (Fig. 3d). These data established that the S64T change in GAP-2g/j isoforms caused increased daf-7 ASJ expression. We observed that the gap-2(syb4046) allele causes a dominant phenotype (Fig. 3f), where the gap-2(tm748) heterozygote conferred an intermediate level of daf-7 ASJ expression compared to the wild-type or gap-2(tm748) homozygous strains (Fig. 3g).

Fig. 3. Natural variants in gap-2 modulate daf-7 expression in the ASJ neurons.

(A) Genomic organization of multiple splice isoforms of gap-2. Deletion alleles of gap-2 and the syb4046 allele in the N2 background are depicted. (B) Representative images of daf-7p::GFP expression in N2 and gap-2(syb4046). Filled triangles indicate the ASI neurons; dashed triangles indicate the ASJ neurons. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C-H) Maximum fluorescence values daf-7p::GFP in the ASJ neurons of indicated strains. HET is heterozygous of N2 and near isogenic line, ZD2627. Each dot represents an individual animal, and error bars indicate standard deviations. ****p<0.0001 and **p<0.01 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test. Each genotype was compared to N2.

Based on the putative alteration of specifically gap-2g and gap-2j isoforms by the 64T variants, we examined whether other variants present in the affected exon specific to gap-2g and gap-2j isoforms might also influence daf-7 ASJ expression. We found that 24 wild strains harbor a variant that causes a putative S11L change (Table 1b). To test the functional consequences of the S11L substitution in GAP-2, we generated the gap-2(syb6873) allele, in which the 11L variant was engineered in the N2 genetic background and observed that the 11L variant also conferred increased daf-7 ASJ expression to a degree comparable to what was conferred by the 64T variant (Fig. 3h).

Table 1b.

Strains that carry GAP-2(L11)

| Strains with L11 |

|---|

| ECA369, JU258, JU2838, JU3166, JU3167, JU3169, MY1, NIC2021, NIC2076, NIC252, NIC266, NIC267, NIC268, NIC269, NIC274, NIC276, QG2813, QG2832, QG2837, QG2841, QG2846, QG4228, WN2063, XZ1735 |

gap-2 natural variants cause differences in a foraging behavioral trait

Having established that two gap-2 variants promoted daf-7 ASJ expression, we sought to connect these variants that alter gene expression to corresponding daf-7-dependent behavioral traits. C. elegans exhibits a two-state foraging behavior that alternates between an exploratory roaming state and an exploitative dwelling state on bacterial food (21, 22). A natural variant in exp-1 (23) and a laboratory-derived mutation in npr-1 (24) have been previously shown to modify the proportion of time that animals spend in the roaming and dwelling states. daf-7 mutants have been shown to spend an increased proportion of time in the dwelling state compared to the N2 wild-type strain (25, 26). Recently, we have shown that the expression of daf-7 in the ASJ neurons is part of a dynamic gene expression feedback loop that promotes increased duration of the roaming state (20).

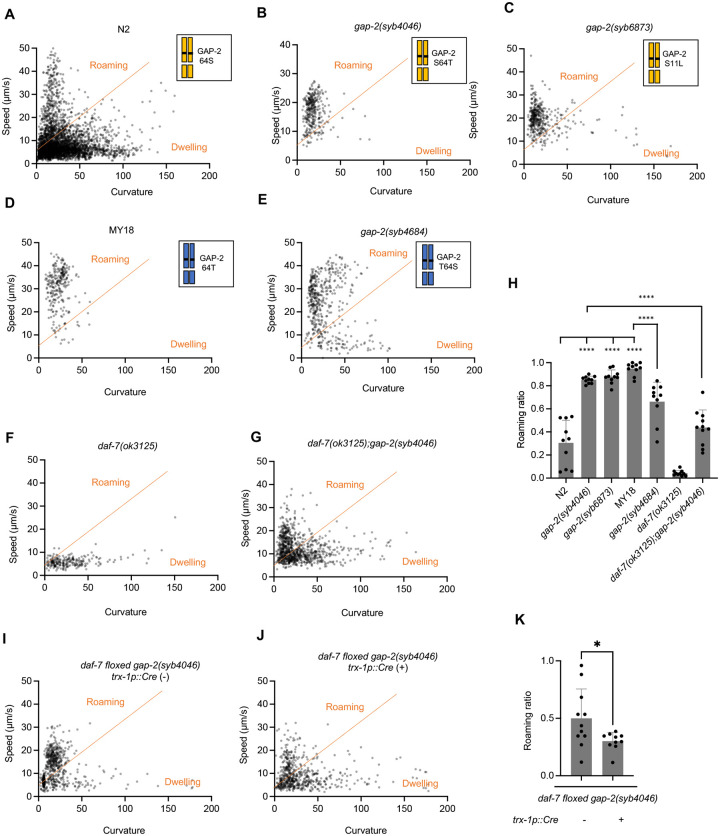

We observed that the MY18 strain exhibited a marked increase in the proportion of time spent in the roaming state relative to the N2 strain (Fig. 4a, d and h). The ancestral 215F allele of npr-1 is known to contribute to increased roaming behavior when compared to the N2 strain that carries a laboratory-derived 215V mutation in npr-1 (24, 27, 28). To examine the effect of the 64T gap-2 variant on foraging behavior, we observed the strain carrying the gap-2(syb4046) S64T allele in the N2 genetic background and found this strain spent an increased proportion of time in the roaming state relative to the N2 strain (Fig. 4a, b and h). In addition, we observed that the strain carrying the gap-2(syb4684) T64S allele in the MY18 genetic background spent a decreased proportion of time in the roaming state (Fig. 4d, e and h). These data establish that the 64T variant in gap-2 promotes an increase in the proportion of time that the animal is in the roaming state relative to the dwelling state when compared with the 64S allele of gap-2 in the N2 or MY18 genetic backgrounds. We also observed that the strain carrying the gap-2 allele with the S11L variant, gap-2(syb6873), in the N2 genetic background also increased the proportion of time that animals spent in the roaming state, to a degree comparable to what was observed for the 64T variant in the N2 background (Fig. 4a, c and h). These data identify two distinct variants acting on the same exon specific to gap-2g and gap-2j isoforms having comparable effects on daf-7 ASJ expression and foraging behavior.

Fig. 4. gap-2 variants affect foraging behavior.

(A-G, I, J) Scatter plot of speed and curvature of each indicated strain. Each dot represents average speed and body curvature during 10 seconds. The orange line was determined on total N2 data and used for analyses of all the strains. Chromosome diagrams indicate gap-2 allele and genetic background (Yellow: N2, Blue: MY18). (H) Roaming ratio of N2, gap-2(syb4046), gap-2(syb6873), MY18, gap-2(syb4684), daf-7(ok3125) and daf-7(ok3125); gap-2(syb4046). Each dot represents average roaming ratio of one animal. ****p<0.0001 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test. (K) Roaming ratio of daf-7 floxed gap-2(syb4046) with or without Ptrx-1::Cre transgene expression. Each dot represents average roaming ratio of one animal. *p<0.05 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test.

gap-2 variants cause differences in foraging behavior by modifying daf-7 neuroendocrine gene expression

To determine whether the gap-2 variants modified roaming behavior by their effects on daf-7 ASJ expression, we first examined the roaming and dwelling behavior of the strain carrying the T64 gap-2 variant and a loss-of-function daf-7 allele in the N2 genetic background. We observed that this gap-2(syb4046); daf-7(ok3125) double mutant exhibited diminished roaming behavior compared with a strain carrying only the gap-2(syb4046) allele in the N2 background (Fig. 4f, g and h). Next, we examined the roaming behavior of a strain carrying the gap-2(syb4046) allele and a floxed daf-7 locus, with and without a transgene expressing Cre under an ASJ-specific (trx-1p) promoter. We observed a diminished proportion of roaming behavior in the animals carrying a selective knockout of daf-7 from the ASJ neurons (Fig. 4i, j and k). These data suggest that the effect of the gap-2(syb4046) variant on daf-7 ASJ expression contributes to the foraging behavior trait difference between the N2 and MY18 strains, although the partial suppression of the increased roaming conferred by the gap-2(syb4046) variant suggests that the variant might also act through DAF-7-independent mechanisms to promote roaming behavior.

gap-2 variants act cell-non-autonomously to modulate neuroendocrine gene expression and foraging behavior

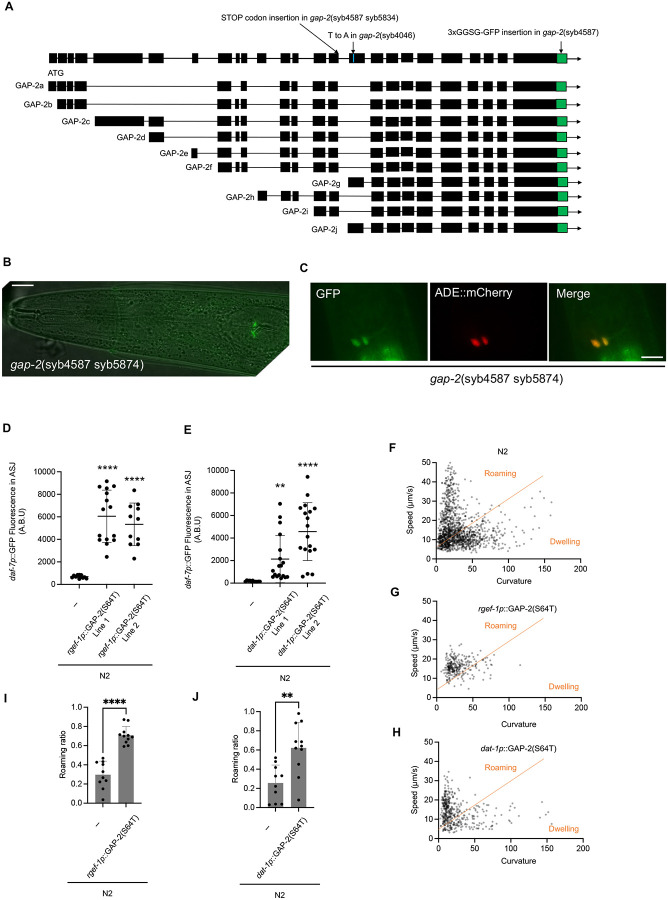

To determine the site-of-action where gap-2 variants modify neuroendocrine gene expression and foraging behavior, we first defined the expression pattern of gap-2 by GFP-tagging endogenous GAP-2 at its C-terminus. We observed expression in multiple cells of the nervous system and vulval cells (Supplemental movie 1a, b), consistent with prior reports of the tissue expression pattern of gap-2 (29). To determine the cells in which the g- and j- isoforms of gap-2 were expressed, we inserted a stop codon in the exon preceding the first exon of the g- and j- isoforms, which was expected to cause only translation of GFP-tagged G- and J- isoforms of GAP-2 (Fig. 5a, b). This strain exhibited GFP expression in a restricted set of cells, including presumptive expression in the ADE neuron pair based on cell location and morphology. We confirmed expression of the putative G- and J- isoforms of GFP-tagged GAP-2 in the ADE neuron pair through colocalization with the expression of the dat-1p::mCherry transgene that is expressed in the ADE neuron pair (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5. Natural variants in gap-2 act in the ADE pair of neurons was sufficient to modulate daf-7 ASJ expression and foraging behavior.

(A) Diagram of the gap-2 genomic locus with C-terminal GFP tagging and stop codon insertion engineered to facilitate the determination of expression pattern. (B) GFP tagged GAP-2g/j isoform expression of the gap-2(syb4587 syb5834) strain. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Colocalization of GAP-2g/j isoform and dat-1p::mCherry reporter. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Maximum fluorescence values daf-7p::GFP in the ASJ neurons of pan-neuronal GAP-2(64T) expressing transgenic strains. Each dot represents an individual animal, and error bars indicate standard deviations. ****p<0.0001 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test. Each genotype was compared to WT. (E) Maximum fluorescence values daf7-p::GFP in the ASJ neurons of ADE neuronal GAP-2(64T) expressing transgenic strains. Each dot represents an individual animal, and error bars indicate standard deviations. ****p<0.0001 and **p<0.01 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test. Each genotype was compared to WT. (F-H) Scatter plot of speed and curvature of each indicated strain. Each dot represents average speed and body curvature during 10 seconds. Orange line has been determined on total N2 data and used for analysis of all the strains. (I) Roaming ratios of pan- neuronal GAP-2(S64T) expressing transgenic strains. Each dot represents an individual animal, and error bars indicate standard deviations. ****p<0.0001 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test. (J) Roaming ratios of ADE neuronal GAP-2(S64T) expressing transgenic strain. Each dot represents an individual animal, and error bars indicate standard deviations. ****p<0.0001 as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test.

We used the expression pattern information to determine the neurons in which expression of the T64 variant of GAP-2 was sufficient to confer increased daf-7 ASJ expression and roaming behavior. Because the 64T variant causes a dominant effect on daf-7 expression, we used a transgene expressing the gap-2 g-isoform cDNA carrying the 64T variant under the control of the pan-neuronal rgef-1 promoter in the N2 genetic background. We also expressed the gap-2 g-isoform cDNA carrying the 64T variant under the control of the ADE neuronal dat-1 promoter in the N2 background. We observed that the expression of the 64T GAP-2 sequence under the control of both pan-neuronal and ADE neuronal promoters, in the N2 genetic background, conferred daf-7 ASJ expression (Fig 5d, e) and an increased proportion of time spent in the roaming state (Fig. 5i, j). These data suggested that expression of the GAP-2 variant in the ADE neurons was sufficient to act cell-non-autonomously to alter the expression of daf-7 from the ASJ neurons and to modify foraging behavior.

Prevalence and geographical distribution of gap-2 variants

The 64T gap-2 variant is present in 48 out of 550 isotype reference strains in the Caenorhabditis Natural Diversity Resource (30), whereas the 11L gap-2 variant is found in 24 of these strains. We also identified two additional rare variants, ENN39E and P19S, which are also predicted to affect the g and j isoforms of gap-2. We examined the geographic origins of these 72 wild strains and observed enrichment for the T64 allele in Africa and Europe (Supplementary Fig S1a). We found that the 11L and ENN39E variants have also been observed in divergent strains from the Hawaiian Islands. Because daf-7 expression is affected by the bacterial diet, we investigated enrichment in specific natural substrates and found that the T64 allele more often found in strains isolated from compost as compared strains isolated from rotting fruit or leaf litter (Supplementary Fig S1b).

Discussion

Our data illustrate how changes in neuronal gene expression caused by natural variants underlie the mechanism by which the variants can exert differential effects on behavioral traits. In particular, we show that natural variants cause differences in behavior by cell-non-autonomously modulating expression levels of a neuroendocrine regulatory ligand in two neurons of C. elegans. The systematic analysis of gene expression as a quantitative trait has been generally conducted on a genome-wide scale enabled by RNA-seq-based methodology (32). Our focus on the expression of a single gene enabled us to use a transgenic fluorescent reporter to examine levels of neuron-specific expression in live animals and facilitated subsequent mapping and molecular characterization. Moreover, daf-7 expression has been previously demonstrated to exhibit dynamic neuron-specific expression and have key functional roles in diverse physiological processes (5, 8–18). Roles for neuromodulators in shaping circuits that govern behavior have been implicated from genetic studies, and our data suggest that variants causing differences in expression levels of genes that encode neuromodulators represent candidate variants that cause differences in behavior.

GAP-2 is one of three GTPase-Activating Proteins in the C. elegans genome that stimulate the LET-60 Ras GTPase to reduce EGF growth factor signaling (29, 33). GAP-2 is orthologous to Disabled 2 interactive protein (DAB2IP), a member of the SynGAP family of GAPs, which has been implicated in a range of disease states (34, 35). The similar dominant effects on daf-7 ASJ expression for both of the 64T and 11L natural variants as compared to the recessive effects of a deletion of gap-2 suggest that 64T and 11L variants confer reduced GAP-2 activity. We speculate that the 64T and 11L GAP-2G and/or GAP-2J isoforms act as dominant-negative proteins that might bind to LET-60 but not activate the GTPase and compete with wild-type GAP-2. Both let-60(n1046) gain-of-function and let-60(n2021) reduction-of-function alleles exhibit pronounced locomotory phenotypes in the presence of bacterial food (36), precluding the analysis of genetic interactions between gap-2 and let-60, but the presence of locomotory defects is consistent with gap-2 affecting Ras signaling in the ADE neurons to alter foraging behavior. Our data also illustrate how the presence of multiple alternatively spliced transcripts of gap-2 might facilitate the emergence of genetic variants that exert effects in a restricted set of neurons. Whereas GAP-2 appears to be widely expressed in the nervous system and in other tissues, the GAP-2g and/or GAP-2j isoforms exhibit restricted expression in the ADE pair of sensory neurons, and two variants, both 64T and 11L, affect an exon specific to these two isoforms.

The neuron-specific expression of daf-7 is modulated by multiple bacteria-derived cues, including environmental and internal food cues (20) and secondary metabolites produced by pathogenic bacteria (15), and DAF-7 signaling contributes to exploratory behaviors, including lawn avoidance (15), mate-searching (16), and roaming behavior (20). The genetic variants in gap-2 that we have identified that modulate daf-7 expression from the ASJ neurons and promote roaming behavior are found in many strains throughout the C. elegans species, suggesting that the variants may confer a fitness advantage in diverse bacterial environments. The enrichment of these gap-2 variants in strains isolated from compost relative to strains isolated from rotting fruit or leaf litter substrates could be because C. elegans isolated from compost are more commonly found as dauer larvae (37). We speculate that animals carrying gap-2 variants might gain advantage in compost environments where increased exploratory behavior might be beneficial in acquiring nutrients. Our data suggest that diversity in behavioral traits associated with host interactions with microbes (38) can emerge from variants affecting the regulation of neuronal gene expression that is modulated by bacteria-derived food and pathogen cues.

Supplementary Material

Table 1a.

Strains that carry GAP-2(T64)

| Strains with T64 |

|---|

| DL200, JU1213, JU1242, JU1400, JU1530, JU1666, JU1808, JU2001, JU2106, JU2131, JU2250, JU2478, JU2534, JU2566, JU2570, JU2575, JU2576, JU310, JU311, JU3128, JU3132, JU3140, JU3144, JU323, JU3795, JU440, JU792, JU847, MY16, MY18, MY2147, MY2453, MY2573, MY2741, MY772, MY795, NIC1, NIC1049, NIC1107, NIC166, NIC1698, NIC277, NIC3, NIC501, WN2064, WN2066, WN2086, WN2117 |

Acknowledgments

We thank Bob Horvitz and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), for strains. We thank the Caenorhabditis Natural Diversity Resource, which is funded by the NSF Capacity grant (2224885), and WormBase for critical genomic and natural variation data. We thank members of the Kim lab for discussions.

Funding:

NIH grant R35GM141794.

Funding Statement

NIH grant R35GM141794.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References

- 1.Niepoth N, Bendesky A. How Natural Genetic Variation Shapes Behavior. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2020;21:437–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-111219-080427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoekstra HE, Robinson GE. Behavioral genetics and genomics: Mendel’s peas, mice, and bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(30):e2122154119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2122154119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bubac CM, Miller JM, Coltman DW. The genetic basis of animal behavioural diversity in natural populations. Mol Ecol. 2020;29(11):1957–1971. doi: 10.1111/mec.15461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yap EL, Greenberg ME. Activity-Regulated Transcription: Bridging the Gap between Neural Activity and Behavior. Neuron. 2018;100(2):330–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill MS, Vande Zande P, Wittkopp PJ. Molecular and evolutionary processes generating variation in gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2021;22(4):203–215. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00304-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GTEx Consortium; Laboratory, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC)—Analysis Working Group; Statistical Methods groups—Analysis Working Group; Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues [published correction appears in Nature. 2017 Dec 20;:]. Nature. 2017;550(7675):204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Klein N, Tsai EA, Vochteloo M, et al. Brain expression quantitative trait locus and network analyses reveal downstream effects and putative drivers for brain-related diseases. Nat Genet. 2023;55(3):377–388. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01300-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang G, Roberto NM, Lee D, Hahnel SR, Andersen EC. The impact of species-wide gene expression variation on Caenorhabditis elegans complex traits. Nat Commun. 2022. Jun 16;13(1):3462. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31208-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golden JW, Riddle DL. A pheromone influences larval development in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1982;218(4572):578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.6896933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan KM, Sarafi-Reinach TR, Horne JG, Saffer AM, Sengupta P. The DAF-7 TGF-beta signaling pathway regulates chemosensory receptor gene expression in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002. Dec 1;16(23):3061–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1027702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bono M, Tobin DM, Davis MW, Avery L, Bargmann CI. Social feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans is induced by neurons that detect aversive stimuli. Nature. 2002;419(6910):899–903. doi: 10.1038/nature01169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw WM, Luo S, Landis J, Ashraf J, Murphy CT. The C. elegans TGF-beta Dauer pathway regulates longevity via insulin signaling. Curr Biol. 2007;17(19):1635–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milward K, Busch KE, Murphy RJ, de Bono M, Olofsson B. Neuronal and molecular substrates for optimal foraging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(51):20672–20677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106134109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greer ER, Pérez CL, Van Gilst MR, Lee BH, Ashrafi K. Neural and molecular dissection of a C. elegans sensory circuit that regulates fat and feeding. Cell Metab. 2008;8(2):118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meisel JD, Panda O, Mahanti P, Schroeder FC, Kim DH. Chemosensation of bacterial secondary metabolites modulates neuroendocrine signaling and behavior of C. elegans. Cell. 2014;159(2):267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilbert ZA, Kim DH. Sexually dimorphic control of gene expression in sensory neurons regulates decision-making behavior in C. elegans. Elife. 2017;6:e21166. Published 2017 Jan 24. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher M, Kim DH. Age-Dependent Neuroendocrine Signaling from Sensory Neurons Modulates the Effect of Dietary Restriction on Longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(1):e1006544. Published 2017 Jan 20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang HC, Paek J, Kim DH. Natural polymorphisms in C. elegans HECW-1 E3 ligase affect pathogen avoidance behaviour. Nature. 2011;480(7378):525–529. Published 2011 Nov 16. doi: 10.1038/nature10643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park J, Meisel JD, Kim DH. Immediate activation of chemosensory neuron gene expression by bacterial metabolites is selectively induced by distinct cyclic GMP-dependent pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(8):e1008505. Published 2020 Aug 10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boor SA, Meisel JD, Kim DH. Genetic Analysis of Bacterial Food Perception and its Influence on Foraging Behavior in C. elegans. BioRxiv. Preprint posted online July 15, 2023. doi: 10.1101/2023.07.15.549072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiwara M, Sengupta P, McIntire SL. Regulation of body size and behavioral state of C. elegans by sensory perception and the EGL-4 cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron. 2002;36(6):1091–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01093-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben Arous J, Laffont S, Chatenay D. Molecular and sensory basis of a food related two-state behavior in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2009. Oct 23;4(10):e7584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendesky A, Pitts J, Rockman MV, et al. Long-range regulatory polymorphisms affecting a GABA receptor constitute a quantitative trait locus (QTL) for social behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(12):e1003157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Bono M, Bargmann CI. Natural variation in a neuropeptide Y receptor homolog modifies social behavior and food response in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;94(5):679–689. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81609-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ben Arous J, Laffont S, Chatenay D. Molecular and sensory basis of a food related two-state behavior in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2009. Oct 23;4(10):e7584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flavell SW, Pokala N, Macosko EZ, Albrecht DR, Larsch J, Bargmann CI. Serotonin and the neuropeptide PDF initiate and extend opposing behavioral states in C. elegans. Cell. 2013;154(5):1023–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung BH, Arellano-Carbajal F, Rybicki I, de Bono M. Soluble guanylate cyclases act in neurons exposed to the body fluid to promote C. elegans aggregation behavior. Curr Biol. 2004;14(12):1105–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray JM, Karow DS, Lu H, et al. Oxygen sensation and social feeding mediated by a C. elegans guanylate cyclase homologue. Nature. 2004;430(6997):317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature02714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashizaki S, Iino Y, Yamamoto M. Characterization of the C. elegans gap-2 gene encoding a novel Ras-GTPase activating protein and its possible role in larval development. Genes Cells. 1998;3(3):189–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook DE, Zdraljevic S, Roberts JP, Andersen EC. CeNDR, the Caenorhabditis elegans natural diversity resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D650–D657. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw8934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Achaz G. Testing for neutrality in samples with sequencing errors. Genetics. 2008. Jul;179(3):1409–24. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.082198. Epub 2008 Jun 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang G, Roberto NM, Lee D, Hahnel SR, Andersen EC. The impact of species-wide gene expression variation on Caenorhabditis elegans complex traits. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3462. Published 2022 Jun 16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31208-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gyurkó MD, Csermely P, Sőti C, Steták A. Distinct roles of the RasGAP family proteins in C. elegans associative learning and memory. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15084. Published 2015 Oct 15. doi: 10.1038/srep15084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klose A, Ahmadian MR, Schuelke M, et al. Selective disactivation of neurofibromin GAP activity in neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(8):1261–1268. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.8.1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gretarsdottir S, Baas AF, Thorleifsson G, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a sequence variant within the DAB2IP gene conferring susceptibility to abdominal aortic aneurysm. Nat Genet. 2010;42(8):692–697. doi: 10.1038/ng.622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamakawa M, Uozumi T, Ueda N, Iino Y, Hirotsu T. A role for Ras in inhibiting circular foraging behavior as revealed by a new method for time and cell-specific RNAi. BMC Biol. 2015. Jan 21;13:6. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0114-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Félix MA, Braendle C. The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2010;20(22):R965–R969. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim DH, Flavell SW. Host-microbe interactions and the behavior of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurogenet. 2020;34(3–4):500–509. doi: 10.1080/01677063.2020.1802724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brady SC, Zdraljevic S, Bisaga KW, et al. A Novel Gene Underlies Bleomycin-Response Variation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2019;212(4):1453–1468. doi: 10.1534/genetics.119.302286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bloom JS, Ehrenreich IM, Loo WT, Lite TL, Kruglyak L. Finding the sources of missing heritability in a yeast cross. Nature. 2013;494(7436):234–237. doi: 10.1038/nature11867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.