Abstract

Objectives

Knowledge of Candida spondylodiscitis is limited to case reports and smaller case series. Controversy remains on the most effective diagnostical and therapeutical steps once Candida is suspected. This systematic review summarized all cases of Candida spondylodiscitis reported to date concerning baseline demographics, symptoms, treatment, and prognostic factors.

Methods

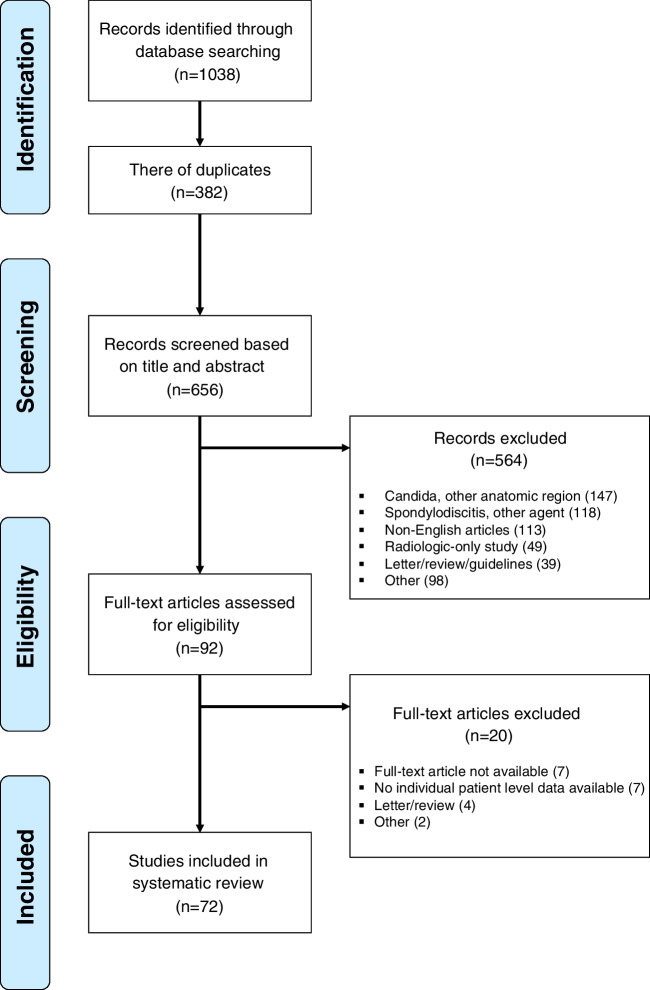

A PRISMA-based search of PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, and OVID Medline was performed from database inception to November 30, 2022. Reported cases of Candida spondylodiscitis were included regardless of Candida strain or spinal levels involved. Based on these criteria, 656 studies were analyzed and 72 included for analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves, Fisher’s exact, and Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests were performed.

Results

In total, 89 patients (67% males) treated for Candida spondylodiscitis were included. Median age was 61 years, 23% were immunocompromised, and 15% IV drug users. Median length of antifungal treatment was six months, and fluconazole (68%) most commonly used. Thirteen percent underwent debridement, 34% discectomy with and 21% without additional instrumentation. Median follow-up was 12 months. The two year survivorship free of death was 80%. The two year survivorship free of revision was 94%. Younger age (p = 0.042) and longer length of antifungal treatment (p = 0.061) were predictive of survival.

Conclusion

Most patients affected by Candida spondylodiscitis were males in their sixties, with one in four being immunocompromised. While one in five patients died within two years of diagnosis, younger age and prolonged antifungal treatment might play a protective role.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00264-023-05989-2.

Keywords: Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Immunosuppression, Spine infection, Drug use

Introduction

Candida albicans is the most common pathogen involved in bloodstream infections [1], with current investigations raising concerns on increasing numbers of multidrug-resistant strains as a potentially new global health threat [2–4]. Despite its importance, limited remains known on spondylodiscitis caused by Candida spp. [5]. Preliminary findings indicate that Candida spondylodiscitis affects high-risk cohorts, including those with prior IV drug abuse, obesity, and diabetes, oftentimes resulting in fatal outcomes [6, 7].

Importantly, diagnostical and therapeutical approaches among this uniquely challenging cohort remain controversial, given limited patient numbers in existing investigations [5]. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, all present investigations are case reports or smaller case series. Moreover, these limited reports on Candida spondylodiscitis have short-term follow-up only [8, 9], while limiting their analysis to certain spinal levels [10], the presence of instrumentation [11, 12], immunosuppressive patients [13], or certain Candida strains [14–16]. This is critical, as it reduces the number of cases in an already limited cohort of patients.

Given its increasing importance, controversial approaches to diagnosis and treatment, and limited patient numbers in existing reports, this review is the first to systematically summarize all cases of Candida spondylodiscitis to date. In addition to analyzing baseline demographics, and identifying potential patients at risk, we aimed to summarize current diagnostical and therapeutic management, together with the outcome and prognostic factors.

Methods

This systematic review was based on PRISMA guidelines [17, 18] and registered in the PROSPERO [19] International prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42022365441). Data collection was performed from October 17, 2022, through November 15, 2022. A re-run prior to the final analysis was performed to include any studies that may have been published during the data collection phase.

We analyzed a total of five databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, and OVID Medline) using the search syntax “albicans” [Title/Abstract] AND (“spondylodiscitis” [Title/Abstract]) with variations depending on the unique syntax of each database (Supplementary Table 1). If available, we also included articles from the “Similar articles”-tools from PubMed to increase the scope of articles screened [20]. Articles that were not available as a full-text English version were excluded unless an English abstract was available yielding sufficient data for analysis.

We included articles reporting microbiology-confirmed cases of Candida spondylodiscitis of any segment of the spine. No restrictions were made based on the year of publication, status of immunocompetency, or length of follow-up. PICO criteria [21] as a mean of evidence-based analysis were followed throughout: we included articles reporting patients with confirmed Candida spondylodiscitis who underwent diagnostic and therapeutic management. No comparator or control group was given and the primary outcome of interest was overall survival (Supplementary Table 2). Articles were excluded if they (1) were non-original articles, (2) were solely reporting osteomyelitis without involvement of the disc, (3) were not involved human subjects, and (4) reported spondylodiscitis caused by other infections agent(s). After removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion eligibility, and if deemed suitable analyzed as a full text.

We collected baseline demographics and information on past history, including age, sex, immunocompetency, presence of IV drug abuse, duration and types of clinical symptoms, previous spinal surgeries, instrumentation status, and affected spinal segment. Comorbidities were analyzed based on the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [22, 23]. In terms of diagnostical workup, we collected data items on CT-guided biopsy prior to initiating antifungal treatment, leukocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as microbiology results. Lastly, we gained data on the treatment regimen including antifungal agents and operative procedures.

Outcome parameters included length of hospital stay (LOS), perioperative complications, number of revisions, final recovery status, and mortality. Partial recovery was defined as continued clinical symptoms or permanent neurologic damage, whereas full recovery was defined as resolution of all initial symptoms at the most recent follow-up.

All results were presented as (1) overall cohort, (2) separated by Candida albicans versus non-albicans, and (3) based on survival at the last follow-up. Categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative values, and continuous variables as median and interquartile ranges. For comparison between groups, we used Fisher’s exact test for binary data to compare frequencies of side effects in two groups and Wilcoxon’s rank sum test to compare continuous data. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Kaplan-Meier survivorship analyses were performed, and differences in survival calculated based on log-rank tests.

Results

After removing 382 duplicates from the initial 1038 studies identified in the search process, 656 articles were analyzed for title and abstract. Following further detailed exclusion criteria, we analyzed 92 articles as full texts, of which 72 were finally included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

The final cohort consisted of 89 patients with a median age of 61 (Table 1, Table 2). Median age-adjusted CCI was 3, 15% had a history of IV drug use, and 23% of patients were immunocompromised. Nearly all patients presented with back or neck pain (99%), whereas fever and weakness were present in 19% only. Symptoms lasted for an average of nine weeks until the final diagnosis was made. Median leukocyte count was 8×109/mL, CRP was 3 mg/dL, and ESR was 65 mm/h. CT-guided biopsy was performed in 53%, with Candida albicans (60%) identified as the most common pathogen. Empiric antibiotic treatment prior to definite diagnosis was administered in 41% of cases. Antifungal monotherapy was given in 58%. The most commonly used antifungal agents included fluconazole (68%), amphotericin B (38%), and echinocandins (26%). The median length of antifungal treatment was six months. Surgical intervention was performed in 68%, including 34% undergoing instrumented discectomy. At a median follow-up of 12 months, 3% developed sepsis, 6% underwent revision, and 12% died of disease. The two year survivorship free of death was 80% (95% CI, 62 to 98%), and the two year survivorship free of revision was 94% (95% CI, 84 to 100%).

Table 1.

Overview of 89 patients with Candida spondylodiscitis identified in 72 studies

| Study | No. of patients | Age (range) | Sex | Spinal level | Candida spp. | Medical therapy | Surgical therapy | Length of treatment, months (range) | Follow-up, months (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaikh et al., 1980 [24] | 1 | 67 | m | L1-L2 | C. albicans | Amphotericin B | None | 1.38 | 4 |

| Hayes et al., 1984 [25] | 1 | 67 | m | L1-L2 | C. tropicalis | None | None | NA | NA |

| Kashimoto et al., 1986 [26] | 1 | 50 | m | T7-T8 | C. tropicalis | None | Debridement | NA | 21 |

| Herzog et al., 1989 [27] | 1 | 88 | m | L4-L5 | C. tropicalis | Ketoconazole, amphotericin B | None | 2.3 | 6 |

| Hennequin et al., 1996 [28] | 2 | 52–61 | 1 m 1 f | 1 T10-T11 1 L3-L4 | 2 C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement | 6 | 17–47 |

| Rieneck et al., 1996 [29] | 1 | 56 | m | L3-L4 | C. albicans | None | None | 6 | NA |

| Munk et al., 1997 [30] | 1 | 67 | m | L2-L3 | C. albicans | Amphotericin B | None | NA | NA |

| Godinho de Matos et al., 1998 [31] | 1 | 45 | m | L5-S1 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | None | NA | NA |

| Rössel et al., 1998 [32] | 1 | 20 | f | T11-T12 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | None | 8.5 | 12 |

| Derkinderen et al., 2000 [33] | 1 | 32 | f | T7-T8 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B, flucytosine | None | 3 | 11 |

| Parry et al., 2001 [34] | 3 | 19–64 | 2 m 1 f | 3 L4-L5 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B, flucytosine | Debridement | 11–13 | 3–8 |

| Sebastiani et al., 2001 [35] | 1 | 67 | m | T8-T9 | C. tropicalis | Fluconazole | None | 3.33 | NA |

| Karlsson et al., 2002 [36] | 1 | 76 | f | L2-L3 | Candida spp. (not specified) | None | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | NA | 36 |

| Tokuyama et al., 2002 [13] | 1 | 44 | f | T12-L1 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, itraconazole | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | NA | NA |

| Torres-Ramos et al., 2004 [37] | 1 | 69 | f | T8-T9 | C. tropicalis | Amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 2.76 | 12 |

| Ugarriza et al., 2004 [38] | 1 | 70 | m | T8-T9 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 4.75 | 36 |

| Chia et al., 2005 [39] | 2 | 50–63 | 2 m | 1 C5-C6 1 T7-T8 | 1 C. albicans 1 C. tropicalis | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 3.75–4.25 | 12 |

| Pemán et al., 2006 [40] | 1 | 62 | m | T5-T6 | C. krusei | Voriconazole, caspofungin | None | 6 | 8 |

| Kroot et al., 2007 [41] | 1 | 28 | m | L5-S1 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | None | NA | NA |

| Yang et al., 2007 [42] | 1 | 79 | m | L2-L3 | Candida spp. (not specified) | None | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | NA | NA |

| Moon et al., 2008 [43] | 1 | 64 | f | C5-C6 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 6.5 | 6 |

| Schilling et al., 2008 [14] | 1 | 58 | m | NA | C. krusei | Fluconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, amphotericin B, caspofungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 13 | 19 |

| Cho et al., 2010 [11] | 1 | 70 | f | L5-S1 | C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 4 | 4 |

| D’Agostino et al., 2010 [44] | 4 | 53–74 | 2 m 2 f | 1 C6-C7 1 T12-L4 1 L1-L2 1 L2-L3 | 3 C. albicans 1 C. glabrata | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | Debridement | 2.07–8.28 | NA |

| Rachapalli et al., 2010 [45] | 1 | 48 | f | T6-T7 | Candida spp. (not specified) | Fluconazole, flucytosine | None | 1.84 | NA |

| Erné et al., 2011 [46] | 1 | 72 | NA | L1-L3 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | NA | 12 |

| Palmisano et al., 2011 [47] | 1 | 48 | f | L3-L4 | C. sake | Fluconazole | None | Ongoing | 25 |

| Werner et al., 2011 [48] | 1 | 40 | f | L3-L4 | C. lusitaniae | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 6 | 24 |

| Chen et al., 2012 [49] | 1 | 59 | m | L3-L5 | C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 1.38 | 3 |

| Grimes et al., 2012 [50] | 1 | 63 | f | L5-S1 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, micafungin | Debridement | 11 | 11 |

| Jorge et al., 2012 [51] | 1 | 73 | m | L5-S1 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 6 | NA |

| Joshi et al., 2012 [52] | 1 | 63 | m | T8-T9 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, caspofungin | None | 6.23 | 6 |

| Theodoros et al., 2012 [53] | 1 | 41 | m | T11-T12 | C. albicans | Caspofungin | None | 1.38 | 10 |

| Chen et al., 2013 [54] | 1 | 41 | m | L3-L4 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | None | 4.5 | 9 |

| Ferrer Civeira et al., 2013 [55] | 1 | 78 | m | L4-L5 | C. tropicalis | Fluconazole | None | NA | NA |

| Lebre et al., 2013 [56] | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Amphotericin B | None | 5 | NA |

| Falakassa et al., 2014 [57] | 1 | 58 | f | T10-T12 | C. glabrata | None | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | NA | NA |

| Iwata et al., 2014 [58] | 3 | 56–72 | 3 m | 1 L2-L3 2 L3-L4 | 3 C. albicans | Voriconazole, fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 0.46–6.44 | 24–92 |

| Oksi et al., 2014 [59] | 1 | 37 | m | L5-S1 | C. dubliniensis | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | None | 7.36 | 3 |

| Savall et al., 2014 [60] | 1 | 22 | m | L1-L2 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | None | 2 | NA |

| Oichi et al., 2015 [16] | 1 | 79 | m | L3-L4 | C. tropicalis | Fluconazole, micafungin | None | NA | 13 |

| Salzer et al., 2015 [61] | 1 | 47 | m | L4-S1 | C. dubliniensis | Fluconazole | None | 3 | NA |

| Zou et al., 2015 [62] | 3 | 56–61 | 2 m 1 f | 1 L3-L4 1 L3-L5 1 L3-S1 | 3 C. albicans | Amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 6–7 | 30–36 |

| Mavrogenis et al., 2016 [63] | 2 | 58–70 | 1 m 1 f | 1 T3-T5 1 T10-T11 | 2 C. albicans | None | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | NA | 0.69–24 |

| Yu et al., 2016 [64] | 1 | 70 | m | L5-S1 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 4 | 12 |

| Lee et al., 2017 [65] | 1 | 66 | f | T11-T12 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 6 | NA |

| Stolberg-Stolberg et al., 2017 [10] | 1 | 60 | m | C4-C6 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, caspofungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 7 | 24 |

| Boyd et al., 2018 [66] | 1 | 71 | f | L5-S1 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement | 12.5 | 12 |

| Che Saidi et al., 2018 [67] | 1 | 67 | f | L2-L3 | C. albicans | None | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | NA | NA |

| Crane et al., 2018 [68] | 1 | 27 | m | T5-T7 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 5 | 48 |

| El Khoury et al., 2018 [69] | 1 | 53 | f | C4-C5 | C. glabrata | Voriconazole, micafungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 6 | 6 |

| Gagliano et al., 2018 [70] | 1 | 66 | m | L3-L4 | C. glabrata | Anidulafungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | NA | NA |

| Khoo et al., 2018 [8] | 1 | 52 | m | L4-L5 | C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole, micafungin | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 6 | 3 |

| Rambo et al., 2018 [71] | 1 | 34 | f | L5-S1 | C. albicans | None | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | NA | 15 |

| Ruiz-Gaitán et al., 2018 [15] | 2 | 42–66 | 2 m | NA | 2 C. auris | Posaconazole, anidulafungin | None | NA | NA |

| Waldon et al., 2018 [72] | 1 | 81 | m | NA | C. glabrata | Anidulafungin | None | 6 | NA |

| Huang et al., 2019 [9] | 1 | 32 | m | C6-C7 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, micafungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 12 | 3 |

| Reaume et al., 2019 [73] | 1 | 46 | f | NA | C. albicans | Anidulafungin | None | NA | 0 |

| Timothy et al., 2019 [74] | 1 | 54 | NA | L3-L4 | C. glabrata | None | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | NA | NA |

| Er et al., 2020 [75] | 1 | 54 | f | T12-L1 | C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole | None | 5 | 5 |

| Overgaauw et al., 2020 [76] | 1 | 78 | m | L4-L5 | C. krusei | Voriconazole, amphotericin B, anidulafungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 9 | 7 |

| Relvas-Silva et al., 2020 [77] | 1 | 66 | f | T8-T9 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B, anidulafungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 12 | 18 |

| Supreeth et al., 2020 [78] | 1 | 50 | m | L4-L5 | C. auris | Caspofungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 1.84 | 6 |

| Upadhyay et al., 2020 [79] | 1 | 61 | m | L4-L5 | C. albicans | Itraconazole, amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 3 | NA |

| Lopes et al., 2021 [80] | 1 | 72 | m | T9-L4 | C. tropicalis | Micafungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 2.76 | NA |

| Moreno-Gomez et al., 2021 [81] | 1 | 47 | m | T8-T9 | C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B | Debridement | 11.5 | 8 |

| von der Höh et al., 2021 [82] | 1 | 73 | m | L3-L4 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 2.63 | NA |

| Wajchenberg et al., 2021 [12] | 1 | 69 | m | L5-S1 | C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole, anidulafungin | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 12 | NA |

| Wang et al., 2021 [83] | 5 | 55–72 | 4 m 1 f | 2 L1-L2 1 L2-L3 1 L3-L4 1 L3-L5 | 5 C. albicans | Fluconazole, amphotericin B, caspofungin | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | NA | 12–20 |

| Yamada et al., 2021 [84] | 1 | 74 | m | L2-L3 | C. albicans | Fluconazole | Debridement, discectomy with instrumentation | 3.5 | 9 |

| Duplan et al., 2022 [85] | 1 | 50 | m | L2-L3 | C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole | Debridement | 9 | NA |

| Wang et al., 2022 [86] | 1 | 62 | f | L4-L5 | C. tropicalis | Amphotericin B | Debridement, discectomy without instrumentation | 12 | 30 |

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and treatment outcome of 89 patients with Candida spondylodiscitis

| Available information | Data not available† | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 61 (50, 68) | 1 (1%) |

| Sex† | 3 (3%) | |

| Female | 28 (33%) | |

| Male | 58 (67%) | |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index* | 3 (1, 5) | 5 (5%) |

| Immunosuppression† | 18 (23%) | 10 (11%) |

| Central venous line† | 14 (18%) | 13 (14%) |

| Previous spinal surgery† | 14 (18%) | 9 (10%) |

| Previous spinal surgery with instrumentation† | 5 (6%) | 9 (10%) |

| IV drug abuse† | 12 (15%) | 9 (10%) |

| Symptom duration until final diagnosis (weeks)* | 9 (4, 17) | 38 (42%) |

| Neck/back pain† | 69 (99%) | 19 (21%) |

| Fever/chills† | 13 (19%) | 21 (23%) |

| Weakness† | 13 (19%) | 21 (23%) |

| Paraplegia† | 3 (4%) | 19 (21%) |

| Leukocyte count (×109/mL)* | 8 (6, 10) | 52 (58%) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL)* | 3 (1, 6) | 54 (60%) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h)* | 65 (42, 96) | 54 (60%) |

| CT-guided biopsy† | 40 (53%) | 14 (15%) |

| Spinal level affected† | 6 (6%) | |

| Cervical | 6 (7%) | |

| Thoracic | 19 (23%) | |

| Thoracolumbar | 4 (5%) | |

| Lumbar | 42 (51%) | |

| Lumbosacral | 12 (14%) | |

| Candida strain† | 1 (1%) | |

| C. albicans | 53 (60%) | |

| C. auris | 3 (3%) | |

| C. dubliniensis | 2 (2%) | |

| C. glabrata | 6 (7%) | |

| C. krusei | 3 (3%) | |

| C. lusitaniae | 1 (1%) | |

| C. parapsilosis | 6 (7%) | |

| C. sake | 1 (1%) | |

| C. tropicalis | 10 (11%) | |

| Candida spp. | 3 (3%) | |

| Administration of empiric antibiotics† | 29 (41%) | 18 (20%) |

| Antifungal monotherapy† | 46 (58%) | 9 (10%) |

| Antifungals† | 9 (10%) | |

| Fluconazole | 54 (68%) | |

| Voriconazole | 6 (8%) | |

| Posaconazole | 3 (4%) | |

| Itraconazole | 2 (3%) | |

| Ketoconazole | 1 (1%) | |

| Amphotericin B | 30 (38%) | |

| Anidulafungin | 7 (9%) | |

| Caspofungin | 7 (9%) | |

| Micafungin | 6 (8%) | |

| Flucytosine | 3 (4%) | |

| Length of antifungal treatment (months)* | 6 (3, 7) | 25 (28%) |

| Surgical treatment regimen† | 4 (4%) | |

| No surgical intervention | 27 (32%) | |

| Isolated debridement | 11 (13%) | |

| Debridement and discectomy with instrumentation | 29 (34%) | |

| Debridement and discectomy without instrumentation | 18 (21%) | |

| Time to surgery since initial clinical presentation (weeks)* | 5 (1, 13) | 71 (79%) |

| Length of stay in hospital (weeks)* | 9 (4, 13) | 64 (71%) |

| Sepsis† | 2 (3%) | 10 (11%) |

| Revision surgery after initial treatment† | 5 (6%) | 10 (11%) |

| Final status† | 14 (15%) | |

| Full recovery | 58 (74%) | |

| Partial recovery | 11 (14%) | |

| Death | 9 (12%) | |

| Follow-up (months)* | 12 (6, 23) | 31 (34%) |

*Values are given as median and interquartile

†Values are given as absolute values and percentages

Among 85 patients with information on the Candida strain, 53 were for Candida albicans (62%) and 32 for Candida non-albicans (38%; Table 3). Both groups did not show statistically significant differences in baseline demographics, prior history, antifungal therapy, and surgical intervention. In contrast, patients with Candida albicans had a significantly higher leukocyte count (p = 0.039) and trended towards significantly increased ESR (p = 0.054) compared to those affected by non-albicans Candida spondylodiscitis. No statistically significant difference was noted in median follow-up, LOS, sepsis, and revision rate, as well as with respect to final recovery status and death. Likewise, the two year survivorship free of death was comparable between albicans (91%; 95% CI, 50 to 100%) non-albicans Candida (82%; 95% CI, 64 to 100%) spondylodiscitis (p = 0.68).

Table 3.

Demographics and outcome stratified by Candida albicans versus non-albicans Candida strain

| Candida albicans (n=53) | Non-albicans (n=32) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 61 (46, 67) | 60.5 (50, 69) | 0.40 |

| Sex† | 0.81 | ||

| Male | 35 (67%) | 22 (71%) | |

| Female | 17 (33%) | 9 (29%) | |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index* | 3 (1, 5) | 3 (1, 6) | 0.66 |

| Previous spinal surgery† | 10 of 48 (21%) | 4 of 31 (13%) | 0.55 |

| Previous spinal surgery with instrumentation† | 2 of 48 (4%) | 3 of 31 (10%) | 0.38 |

| Leukocyte count (×109/mL)* | 9 (6.95, 11.65) | 6.5 (3.96, 8) | 0.039 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL)* | 3.4 (2.18, 5.685) | 1.5 (0.7, 11.8) | 0.28 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h)* | 87 (62, 109) | 51 (41, 66) | 0.054 |

| Spinal level affected† | 0.98 | ||

| Cervical | 4 (8%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Thoracic | 12 (23%) | 6 (21%) | |

| Thoracolumbar | 2 (4%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Lumbar | 26 (50%) | 14 (50%) | |

| Lumbosacral | 8 (15%) | 4 (14%) | |

| Candida strain† | |||

| C. auris | 3 (9%) | ||

| C. dubliniensis | 2 (6%) | ||

| C. glabrata | 6 (19%) | ||

| C. krusei | 3 (9%) | ||

| C. lusitaniae | 1 (3%) | ||

| C. parapsilosis | 6 (19%) | ||

| C. sake | 1 (3%) | ||

| C. tropicalis | 10 (31%) | ||

| Antifungal monotherapy† | 28 of 48 (58%) | 17 of 28 (61%) | 0.99 |

| Antifungal class if monotherapy† | 0.36 | ||

| Azole | 21 (75%) | 10 (59%) | |

| Echinocandin | 2 (7%) | 4 (24%) | |

| Amphotericin B | 5 (18%) | 3 (18%) | |

| Length of antifungal treatment (months)* | 6 (3.22, 8.28) | 5.5 (2.76, 7.36) | 0.51 |

| Surgical intervention† | 38 of 53 (72%) | 18 of 29 (62%) | 0.46 |

| Follow-up (months)* | 12 (8, 24) | 7.5 (5, 19) | 0.13 |

| Length of stay in hospital (weeks)* | 9 (3, 13) | 7.5 (4, 12) | 0.86 |

| Sepsis† | 1 of 50 (2) | 1 of 28 (4%) | 0.67 |

| Revision surgery after initial treatment† | 3 of 50 (6) | 1 of 28 (4%) | 0.64 |

| Final status† | 0.36 | ||

| Full recovery | 37 (77%) | 20 (69%) | |

| Partial recovery | 5 (10%) | 6 (21%) | |

| Death | 6 (13%) | 3 (10%) |

Numbers in bold indicate reaching significance (p-value < 0.05)

*Values are given as median and interquartile

†Values are given as absolute values and percentages

In total, 76 patients had a known survival status at the last follow-up, with 67 surviving and 9 dying by disease (Table 4). Younger age (p = 0.042) and longer length of antifungal therapy (p = 0.061) were predictive of survival, whereas outcome did not differ based on Candida strain (p = 0.74) and affected spinal level (p = 0.44).

Table 4.

Patient demographics stratified by survival following Candida spondylodiscitis

| Survival (n=67) | Death (n=9) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 59 (47, 67) | 67 (62, 72) | 0.042 |

| Sex† | 0.99 | ||

| Male | 43 (65%) | 6 (67%) | |

| Female | 23 (35%) | 3 (33%) | |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index* | 3 (1, 4) | 4 (3, 5.5) | 0.14 |

| Previous spinal surgery† | 51 of 64 (80%) | 9 of 9 (100%) | 0.35 |

| Previous spinal surgery with instrumentation† | 59 of 64 (92%) | 9 of 9 (100%) | 0.99 |

| Leukocyte count (×109/mL)* | 8.2 (6.6, 10.8) | 6.8 (5.6, 8) | 0.37 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL)* | 3.145 (1.5, 6.07) | 1.1 (1.1, 1.1) | 0.28 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h)* | 68 (41, 98) | 51 (51, 51) | 0.61 |

| Spinal level affected† | 0.44 | ||

| Cervical | 6 (9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Thoracic | 15 (23%) | 3 (38%) | |

| Thoracolumbar | 3 (5%) | 1 (13%) | |

| Lumbar | 30 (45%) | 4 (50%) | |

| Lumbosacral | 12 (18%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Candida strain† | 0.74 | ||

| C. auris | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| C. dubliniensis | 2 (9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| C. glabrata | 3 (13%) | 0 (0%) | |

| C. krusei | 2 (9%) | 1 (33%) | |

| C. lusitaniae | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| C. parapsilosis | 6 (26%) | 0 (0%) | |

| C. sake | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| C. tropicalis | 7 (30%) | 2 (67%) | |

| Antifungal monotherapy† | 28 of 63 (44%) | 2 of 7 (29%) | 0.69 |

| Antifungal class if monotherapy† | 0.11 | ||

| Azole | 25 (71%) | 2 (40%) | |

| Echinocandin | 3 (9%) | 2 (40%) | |

| Amphotericin B | 7 (20%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Length of antifungal treatment (months)* | 6 (3.22, 8.5) | 2.695 (2.005, 4.38) | 0.061 |

| Surgical intervention† | 22 of 67 (33%) | 4 of 9 (44%) | 0.48 |

| Follow-up (months)* | 12 (6, 24) | 8 (.69, 13) | 0.15 |

Numbers in bold indicate reaching significance (p-value < 0.05)

*Values are given as median and interquartile

†Values are given as absolute values and percentages

Discussion

Limited remains known on Candida spondylodiscitis outside of case reports and smaller case series. As such, this systematic review analyzed 89 patients treated for spondylodiscitis at a median follow-up of 12 months. Our results demonstrated one in five patients affected by Candida spondylodiscitis to die within two years. Importantly, Candida albicans and non-albicans were similar in their prognosis, whereas younger age and prolonged antifungal treatment were associated with increased survival.

Baseline clinical and demographic factors

Knowledge of baseline demographics among patients affected by Candida spondylodiscitis is important, as it may allow to identify potential patients at risk. First reports date back to the 1970s [87], and Candida spondylodiscitis has since then been associated with immunocompromised patients, and those with other significant comorbidities including diabetes, obesity, or IV drug abuse [88–90]. In this systematic review, we identified most affected patients to be males in their sixties, with one in four demonstrating signs of immunocompromise, and another 15% reporting previous IV drug use. While these findings partially reflect the aforementioned historical literature, one must acknowledge that the majority of patients had no clearly attributable risk factors. Prospective multicentre studies will be necessary to draw final conclusions, based on comparison with spondylodiscitis caused by other pathogens.

Diagnostic challenges of Candida spondylodiscitis

The diagnosis of Candida spondylodiscitis remains challenging, especially as symptom onset is subacute, and oftentimes gradually progressive over weeks to months [91–93]. In fact, 99% of patients had back or neck pain during initial clinical assessment, while less than 20% had systematic signs of infection (fever). Correspondingly, and similar to previous findings, CRP was only mildly elevated [94–96]. Although initial identification of Candida spondylodiscitis may therefore remain difficult, a number of factors distinguish it from a bacterial entity, once the diagnosis of spondylodiscitis is suspected. Foremost, the lumbar spine is more commonly affected (50%) [97], symptom onset is less acute, and Candida spondylodiscitis rarely causes chills [98, 99]. This differentiation is important, as it may allow for an earlier antifungal treatment initiation.

Antifungal treatment and surgical considerations as the mainstay of therapy

Pathogen eradication is the primary goal in treatment of Candida spondylodiscitis, with its success depending on rates of antifungal disc penetration and antimicrobial resistances [76]. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends fluconazole (400 mg; 6 mg/kg daily) for six to 12 months in case of Candida osteomyelitis but does not specify for spondylodiscitis [100]. Although our findings partially reflect current IDSA recommendations on Candida osteomyelitis, treatment still varied significantly among the 89 patients. We believe this heterogeneity to be attributable to possible treatment resistances requiring changes in antifungal medications [101], as well as contradictory recommendations on antifungal length, ranging from a few weeks to over a year [12, 24, 53]. Finally, different approaches on empiric treatment may have been a contributing factor [29, 54, 61]. Despite these discrepancies, antimicrobial therapy remains the most important part of the treatment of spondylodiscitis [5] with surgery only being recommended in cases of spinal instability, a mass effect due to abscess, or neurologic deterioration [10, 102, 103]. We believe the prolongated symptom onset prior to definite antifungal treatment, combined with possible extensive local disease progression, and possibly unclear preoperative diagnosis to explain the high rates of surgery among our patients (68%). Despite an increase in antifungal resistance, large-scale surveys of pathogenic yeasts isolated from blood cultures suggest that clinical consequences may not be expected from this trend [104]. Further, Candida spp. may be subject to a confirmation bias owing to advances in testing susceptibility [105]. Surgical intervention was most commonly pursued if spinal instability was suspected or management solely based on antifungal agents deemed insufficient.

Prognostic factors in Candida spondylodiscitis

The prognosis in Candida spondylodiscitis remained poor, with only 77% achieving full recovery, and 12% dying at a median follow-up of one year. The two year calculated survivorship free of death was even as low as 80%, predicting one in five patients to die within two years of diagnosis. Importantly, Candida strain was not predictive of death, as previously described in periprosthetic joint infections [16, 40]. In contrast, younger age at diagnosis and longer antifungal treatment were predictive of survival, with the latter being a promising alternative for future research. Of note, only 6% of patients were in need of revision surgery. This is important, as spinal revision surgery is known to significantly compromise functional recovery [77, 86, 106].

Limitations

This systematic review had limitations that in return were attributable to the weaknesses of its included studies. Foremost, most articles included five cases or less, limiting the overall number and generalizability. In addition, not all information could be included for every patient. In specific, details on secondary diseases were not provided in the majority of articles, and follow-up defined inconsistently. Additionally, some data such as clinical examination results and laboratory results were inconsistently reported among cases. This may have compromised the generalizability of our results. We have nevertheless included these data points to enhance to informative value of our tables, even when data could not be included in our statistical analysis. Finally, we were not able to provide regression models to precise potential risk and outcome factors, as the high proportion of missing information would have corrupted the analysis.

In conclusion, patients affected by Candida spondylodiscitis tend to be males in their sixties, present with local rather than systematic symptoms, and have a poor short-term prognosis with one in five dying within two years of diagnosis. This first systematic review on Candida spondylodiscitis might help physicians in identifying patients at risk and when providing a prognosis. Consensus meetings will be necessary to determine an optimal future treatment approach.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 29 kb)

Author contribution

Conception and design: DK. Acquisition of data: SJA, DK. Statistical analysis: MRG. Analysis and interpretation of data: SJA, DK, MRG, AB, AK, HCB, OA. Drafting the article: SJA, DK, MRG, AB, AK, HCB, OA. Critically revising the article: SJA, DK, MRG, AB, AK, HCB, OA. Administrative/technical/material support: DK. Study supervision: DK. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: SJA, DK, MRG, AB, AK, HCB, OA.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The authors declare that data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

The authors declare that code for data analysis will be made available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Daniel Karczewski AO Spine - Member 100329581

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Reda NM, Hassan RM, Salem ST, Yousef RHA (2022) Prevalence and species distribution of Candida bloodstream infection in children and adults in two teaching university hospitals in Egypt: first report of Candida kefyr. Infection. 10.1007/s15010-022-01888-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Du H, Bing J, Hu T, Ennis CL, Nobile CJ, Huang G. Candida auris: epidemiology, biology, antifungal resistance, and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008921. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortegiani A, Misseri G, Fasciana T, Giammanco A, Giarratano A, Chowdhary A. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, resistance, and treatment of infections by Candida auris. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:69. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0342-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhodes J, Fisher MC. Global epidemiology of emerging Candida auris. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;52:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skaf GS, Domloj NT, Fehlings MG, Bouclaous CH, Sabbagh AS, Kanafani ZA, Kanj SS. Pyogenic spondylodiscitis: an overview. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimopoulos G, Ntziora F, Rachiotis G, Armaganidis A, Falagas ME. Candida albicans versus non-albicans intensive care unit-acquired bloodstream infections: differences in risk factors and outcome. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:523–529. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181607262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow JK, Golan Y, Ruthazer R, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y, Lichtenberg D, Chawla V, Young J, Hadley S. Factors associated with candidemia caused by non-albicans Candida species versus Candida albicans in the intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1206–1213. doi: 10.1086/529435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoo T, Psevdos G, Wu J. Candida parapsilosis lumbar spondylodiscitis as a cause of chronic back pain. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2018;26:e58–e60. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0000000000000615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S, Kappel AD, Peterson C, Chamiraju P, Rajah GB, Moisi MD. Cervical spondylodiscitis caused by Candida albicans in a non-immunocompromised patient: a case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:151. doi: 10.25259/SNI_240_2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stolberg-Stolberg J, Horn D, Rosslenbroich S, Riesenbeck O, Kampmeier S, Mohr M, Raschke MJ, Hartensuer R. Management of destructive Candida albicans spondylodiscitis of the cervical spine: a systematic analysis of literature illustrated by an unusual case. Eur Spine J. 2017;26:1009–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4827-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho K, Lee SH, Kim ES, Eoh W. Candida parapsilosis spondylodiscitis after lumbar discectomy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;47:295–297. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2010.47.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wajchenberg M, Astur N, Kanas M, Camargo TZS, Wey SB, Martins DE. Candida parapsilosis infection after lumbosacral arthrodesis with a PEEK TLIF interbody fusion device: case report. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo) 2021;56:390–393. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tokuyama T, Nishizawa S, Yokota N, Ohta S, Yokoyama T, Namba H. Surgical strategy for spondylodiscitis due to Candida albicans in an immunocompromised host. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2002;42:314–317. doi: 10.2176/nmc.42.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schilling A, Seibold M, Mansmann V, Gleissner B. Successfully treated Candida krusei infection of the lumbar spine with combined caspofungin/posaconazole therapy. Med Mycol. 2008;46:79–83. doi: 10.1080/13693780701552996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz-Gaitan A, Moret AM, Tasias-Pitarch M, Aleixandre-Lopez AI, Martinez-Morel H, Calabuig E, Salavert-Lleti M, Ramirez P, Lopez-Hontangas JL, Hagen F, Meis JF, Mollar-Maseres J, Peman J. An outbreak due to Candida auris with prolonged colonisation and candidaemia in a tertiary care European hospital. Mycoses. 2018;61:498–505. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oichi T, Sasaki S, Tajiri Y. Spondylodiscitis concurrent with infectious aortic aneurysm caused by Candida tropicalis: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2015;23:251–254. doi: 10.1177/230949901502300230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, Stewart L. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2012;1:2. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammadi S, Kylasa S, Kollias G, Grama A. 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW) IEEE; 2016. Context-specific recommendation system for predicting similar pubmed articles; pp. 1007–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang X, Lin J, Demner-Fushman D. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006;2006:359–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaikh BS, Appelbaum PC, Aber RC (1980) Vertebral disc space infection and osteomyelitis due to Candida albicans in a patient with acute myelomonocytic leukemia. Cancer 45:1025–1028. 10.1002/1097-0142(19800301)45:5<1025::aid-cncr2820450532>3.0.co;2-i [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Hayes WS, Berg RA, Dorfman HD, Freedman MT. Case report 291. Diagnosis: Candida discitis and vertebral osteomyelitis at L1-L2 from hematogenous spread. Skelet Radiol. 1984;12:284–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00349511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashimoto T, Kitagawa H, Kachi H. Candida tropicalis vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis. A case report and discussion on the diagnosis and treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1986;11:57–61. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198601000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herzog W, Perfect J, Roberts L. Intervertebral diskitis due to Candida tropicalis. South Med J. 1989;82:270–273. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198902000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennequin C, Bouree P, Hiesse C, Dupont B, Charpentier B. Spondylodiskitis due to Candida albicans: report of two patients who were successfully treated with fluconazole and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:176–178. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rieneck K, Hansen SE, Karle A, Gutschik E. Microbiologically verified diagnosis of infectious spondylitis using CT-guided fine needle biopsy. APMIS. 1996;104:755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1996.tb04939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munk PL, Lee MJ, Poon PY, O’Connell JX, Coupland DB, Janzen DL, Logan PM, Dvorak MF. Candida osteomyelitis and disc space infection of the lumbar spine. Skelet Radiol. 1997;26:42–46. doi: 10.1007/s002560050189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godinho de Matos I, Do Carmo G, da Luz AM. Spondylodiscitis by Candida albicans. Infection. 1998;26:195–196. doi: 10.1007/BF02771856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossel P, Schonheyder HC, Nielsen H. Fluconazole therapy in Candida albicans spondylodiscitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:527–530. doi: 10.1080/00365549850161601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derkinderen P, Bruneel F, Bouchaud O, Regnier B. Spondylodiscitis and epidural abscess due to Candida albicans. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:72–74. doi: 10.1007/s005860050013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parry MF, Grant B, Yukna M, Adler-Klein D, McLeod GX, Taddonio R, Rosenstein C. Candida osteomyelitis and diskitis after spinal surgery: an outbreak that implicates artificial nail use. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:352–357. doi: 10.1086/318487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebastiani GD, Galas F. Spondylodiscitis due to Candida tropicalis as a cause of inflammatory back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:435–437. doi: 10.1007/s100670170011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsson MK, Hasserius R, Olerud C, Ohlin A. Posterior transpedicular stabilisation of the infected spine. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:522–525. doi: 10.1007/s00402-002-0440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torres-Ramos FM, Botwin K, Shah CP. Candida spondylodiscitis: an unusual case of thoracolumbar pain with review of imaging findings and description of the clinical condition. Pain Physician. 2004;7:257–260. doi: 10.36076/ppj.2004/7/257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ugarriza LF, Cabezudo JM, Lorenzana LM, Rodríguez-Sánchez JA. Candida albicans spondylodiscitis. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:189–192. doi: 10.1080/02688690410001681091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chia SL, Tan BH, Tan CT, Tan SB. Candida spondylodiscitis and epidural abscess: management with shorter courses of anti-fungal therapy in combination with surgical debridement. J Inf Secur. 2005;51:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peman J, Jarque I, Bosch M, Canton E, Salavert M, de Llanos R, Molina A. Spondylodiscitis caused by Candida krusei: case report and susceptibility patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1912–1914. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1912-1914.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroot EJA, Wouters JMWG. An unusual case of infectious spondylodiscitis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1296–1296. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang SC, Fu TS, Chen LH, Niu CC, Lai PL, Chen WJ. Percutaneous endoscopic discectomy and drainage for infectious spondylitis. Int Orthop. 2007;31:367–373. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0188-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moon HH, Kim JH, Moon BG, Kim JS. Cervical spondylodiscitis caused by Candida albicans in non-immunocompromised patient. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008;43:45–47. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2008.43.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D'Agostino C, Scorzolini L, Massetti AP, Carnevalini M, d'Ettorre G, Venditti M, Vullo V, Orsi GB. A seven-year prospective study on spondylodiscitis: epidemiological and microbiological features. Infection. 2010;38:102–107. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rachapalli SM, Malaiya R, Mohd TA, Hughes RA. Successful treatment of Candida discitis with 5-flucytosine and fluconazole. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1543–1544. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.(2011) 6. Deutscher Wirbelsäulenkongress Jahrestagung der Deutschen Wirbelsäulengesellschaft 8. – 10. Dezember 2011, Hamburg. Eur Spine J 20:1979. 10.1007/s00586-011-2033-x

- 47.Palmisano A, Benecchi M, De Filippo M, Maggiore U, Buzio C, Vaglio A. Candida sake as the causative agent of spondylodiscitis in a hemodialysis patient. Spine J. 2011;11:e12–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Werner BC, Hogan MV, Shen FH. Candida lusitaniae discitis after discogram in an immunocompetent patient. Spine J. 2011;11:e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen H, Lin E. MRI images of a patient with spondylodiscitis and epidural abscess after stem cell injections to the spine. IJCRI. 2012;3:62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimes CL, Tan-Kim J, Garfin SR, Nager CW. Sacral colpopexy followed by refractory Candida albicans osteomyelitis and discitis requiring extensive spinal surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:464–468. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256989e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jorge VC, Cardoso C, Noronha C, Simoes J, Riso N, Vaz Riscado M (2012) Fungal spondylodiscitis in a non-immunocompromised patient. BMJ Case Rep 2012. 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Joshi TN. Candida albicans spondylodiscitis in an immunocompetent patient. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:221–222. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.98261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelesidis T, Tsiodras S. Successful treatment of azole-resistant Candida spondylodiscitis with high-dose caspofungin monotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2957–2958. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2121-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C-H, Chen WL, Yen H-C. Candida albicans lumbar spondylodiscitis in an intravenous drug user: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:529. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Civeira MF, Olmos MC, Aparicio AL, Pancorbo AG-E, Villalba M, Gonzalez-Cobos CL, Casado SG, Llorente BP. Candida spondylodiscitis and urinary colonization. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:e207–e208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.08.531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lebre A, Velez J, Rabadão E, Oliveira J, da Cunha JS, Silvestre AM. Infectious spondylodiscitis: a retrospective study of 140 patients. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2014;22:223–228. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0000000000000118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Falakassa J, Hirsch BP, Norton RP, Mendez-Zfass M, Eismont FJ. Case reviews of infections of the spine in patients with a history of solid organ transplantation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E1154–E1158. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iwata A, Ito M, Abumi K, Sudo H, Kotani Y, Shono Y, Minami A. Fungal spinal infection treated with percutaneous posterolateral endoscopic surgery. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2014;75:170–176. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oksi J, Finnila T, Hohenthal U, Rantakokko-Jalava K. Candida dubliniensis spondylodiscitis in an immunocompetent patient. Case report and review of the literature. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2014;3:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Savall F, Dedouit F, Telmon N, Rouge D. Candida albicans spondylodiscitis following an abdominal stab wound: forensic considerations. J Forensic Legal Med. 2014;23:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salzer HJ, Rolling T, Klupp EM, Schmiedel S. Hematogenous dissemination of Candida dubliniensis causing spondylodiscitis and spinal abscess in a HIV-1 and HCV-coinfected patient. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2015;8:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zou MX, Peng AB, Dai ZH, Wang XB, Li J, Lv GH, Deng YW, Wang B. Postoperative initial single fungal discitis progressively spreading to adjacent multiple segments after lumbar discectomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;128:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mavrogenis AF, Igoumenou V, Tsiavos K, Megaloikonomos P, Panagopoulos GN, Vottis C, Giannitsioti E, Papadopoulos A, Soultanis KC. When and how to operate on spondylodiscitis: a report of 13 patients. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s00590-015-1674-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu LD, Feng ZY, Wang XW, Ling ZH, Lin XJ. Fungal spondylodiscitis in a patient recovered from H7N9 virus infection: a case study and a literature review of the differences between Candida and Aspergillus spondylodiscitis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2016;17:874–881. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee J-H, Chough C-K, Choi S-M. Late onset Candida albicans spondylodiscitis following Candidemia: a case report. Taehan Uijinkyun Hakhoe Chi. 2017;22:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boyd B, Pratt T, Mishra K. Fungal lumbosacral osteomyelitis after robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:e46–e48. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.CS CSSZ, Foo CH, Lim HS (2018) A case of pyogenic spondylodiscitis complicated with pseudoaneurysm. 4.8 Spine - ES48:1. https://www.morthoj.org/supplements/2018/index.php. Accessed 25 Sep 2023

- 68.Crane JK (2018) Intrathecal spinal abscesses due to Candida albicans in an immunocompetent man. BMJ Case Rep 2018. 10.1136/bcr-2017-223326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.El Khoury C, Younes P, Hallit R, Okais N, Matta MA. Candida glabrata spondylodiscitis: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2018;12:32S. doi: 10.3855/jidc.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gagliano M, Marchiani C, Bandini G, Bernardi P, Palagano N, Cioni E, Finocchi M, Bellando Randone S, Moggi Pignone A. A rare case of Candida glabrata spondylodiscitis: case report and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;68:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rambo WM., Jr Treatment of lumbar discitis using silicon nitride spinal spacers: A case series and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;43:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waldon K, Chattopadhyay T. Lessons learned from a case of Candida discitis. Age Ageing. 2017;47:156–156. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shallal A, Boapimp P (2019) Candida endocarditis: a diagnostic challenge with a fatal outcome. In: B51 critical care case reports: CardiovasculaR Diseases in the ICU II, p A3540. Conference: American Thoracic Society 2019 International Conference, Dallas TX, 17–22 May 2019. 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2019.199.1_MeetingAbstracts.A3540

- 74.Timothy J, Pal D, Akhunbay-Fudge C, Knights M, Frost A, Derham C, Selvanathan S. Extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF) as a treatment for acute spondylodiscitis: leeds spinal unit experience. J Clin Neurosci. 2019;59:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Er H, Yılmaz NÖ, Sandal E, Şenoğlu M (2020) A case of Candida spondylodiscitis in an immunocompetent patient. Ann Clin Anal Med. 10.4328/ACAM.20103

- 76.Overgaauw AJC, de Leeuw DC, Stoof SP, van Dijk K, Bot JCJ, Hendriks EJ. Case report: Candida krusei spondylitis in an immunocompromised patient. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:739. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05451-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Relvas-Silva M, Pinho AR, Vital L, Leao B, Sousa AN, Carvalho AC, Veludo V. Azole-resistant Candida albicans spondylodiscitis after bariatric surgery: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2020;10:e1900618. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.CC.19.00618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Supreeth S, Al Ghafri KA, Jayachandra RK, Al Balushi ZY. First report of Candida auris spondylodiscitis in Oman: a rare presentation. World Neurosurg. 2020;135:335–338. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Upadhyay A, Bapat M, Patel B, Gujral A. Postoperative fungal discitis in immune-competent patients: A series of five patients. Indian Spine J. 2020;3:243–249. doi: 10.4103/isj.isj_41_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lopes A, Andrade RA, Andrade RG, Zirpoli BBP, Maior ABS, Silva GAL, Andrade M. Candida tropicalis spondylodiscits in an immunocompetent host: a case report and literature review. Arquivos Brasileiros de Neurocirurgia: Brazilian Neurosurgery. 2021;40:e412–e416. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1735800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moreno-Gomez LM, Esteban-Sinovas O, Garcia-Perez D, Garcia-Posadas G, Delgado-Fernandez J, Paredes I. Case report: SARS-CoV-2 infection-are we redeemed? A report of Candida spondylodiscitis as a late complication. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:751101. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.751101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.von der Hoh NH, Pieroh P, Henkelmann J, Branzan D, Volker A, Wiersbicki D, Heyde CE. Spondylodiscitis due to transmitted mycotic aortic aneurysm or infected grafts after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR): a retrospective single-centre experience with short-term outcomes. Eur Spine J. 2021;30:1744–1755. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Z, Truong VT, Shedid D, Newman N, Mc Graw M, Boubez G. One-stage oblique lateral corridor antibiotic-cement reconstruction for Candida spondylodiscitis in patients with major comorbidities: preliminary experience. Neurochirurgie. 2021;67:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamada T, Shindo S, Otani K, Nakai O (2021) Candia albicans lumbar spondylodiscitis contiguous to infected abdominal aortic aneurysm in an intravenous drug user. BMJ Case Rep 14. 10.1136/bcr-2020-241493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Duplan P, Memon MB, Choudhry H, Patterson J. A rare case of Candida parapsilosis lumbar discitis with osteomyelitis. Cureus. 2022;14:e25955. doi: 10.7759/cureus.25955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang C, Zhang L, Zhang H, Xu D, Ma X. Sequential endoscopic and robot-assisted surgical solutions for a rare fungal spondylodiscitis, secondary lumbar spinal stenosis, and subsequent discal pseudocyst causing acute cauda equina syndrome: a case report. BMC Surg. 2022;22:34. doi: 10.1186/s12893-022-01493-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Riffat G, Domenach M, Vignon H, Dorche G. Spondylodiscitis during septicemia caused by Candida albicans. Ann Anesthesiol Fr. 1974;15:223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aguilar GL, Blumenkrantz MS, Egbert PR, McCulley JP (1979) Candida endophthalmitis after intravenous drug abuse. Arch Ophthalmol 97(1):96–100. 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010036008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Fleming L, Ng A, Paden M, Stone P, Kruse D. Fungal osteomyelitis of calcaneus due to Candida albicans: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;51:212–214. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fennelly AM, Slenker AK, Murphy LC, Moussouttas M, DeSimone JA. Candida cerebral abscesses: a case report and review of the literature. Med Mycol. 2013;51:779–784. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2013.789566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tsantes AG, Papadopoulos DV, Vrioni G, Sioutis S, Sapkas G, Benzakour A, Benzakour T, Angelini A, Ruggieri P, Mavrogenis AF, World Association Against Infection In O, Trauma WAIOTSGOB, Joint Infection D (2020) Spinal infections: an update. Microorganisms 8. 10.3390/microorganisms8040476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Jensenius M, Heger B, Dalgard O, Stiris M, Ringertz SH. Serious bacterial and fungal infections in intravenous drug addicts. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1999;119:1759–1762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thurnher MM, Olatunji RB. Infections of the spine and spinal cord. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;136:717–731. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53486-6.00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schneider T, Wildforster U, Diekmann J. PMN granulocyte elastase--an early indicator of postoperative spondylodiscitis? Acta Neurochir. 1995;136:16–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01411430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lin Y, Li F, Chen W, Zeng H, Chen A, Xiong W. Single-level lumbar pyogenic spondylodiscitis treated with mini-open anterior debridement and fusion in combination with posterior percutaneous fixation via a modified anterior lumbar interbody fusion approach. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23:747–753. doi: 10.3171/2015.5.SPINE14876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sheikh AF, Khosravi AD, Goodarzi H, Nashibi R, Teimouri A, Motamedfar A, Ranjbar R, Afzalzadeh S, Cyrus M, Hashemzadeh M. Pathogen identification in suspected cases of pyogenic spondylodiscitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:60. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Robinson Y, Tschoeke SK, Finke T, Kayser R, Ertel W, Heyde CE. Successful treatment of spondylodiscitis using titanium cages: a 3-year follow-up of 22 consecutive patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:660–664. doi: 10.1080/17453670810016687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lohr KM, Barthelemy CR, Schwab JP, Haasler GB (1987) Septic spondylodiscitis in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 14:616–620. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kristine-Lohr/publication/19535577_Septic_spondylodiscitis_in_ankylosing_spondylitis/links/58e2992eaca2722505d162ff/Septic-spondylodiscitis-in-ankylosing-spondylitis.pdf. Accessed 25 Sep 2023 [PubMed]

- 99.Weber M, Gubler J, Fahrer H, Crippa M, Kissling R, Boos N, Gerber H. Spondylodiscitis caused by viridans streptococci: three cases and a review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18:417–421. doi: 10.1007/s100670050130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Schuster MG, Vazquez JA, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE, Sobel JD. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–e50. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thompson GR, 3rd, Wiederhold NP, Vallor AC, Villareal NC, Lewis JS, 2nd, Patterson TF. Development of caspofungin resistance following prolonged therapy for invasive candidiasis secondary to Candida glabrata infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3783–3785. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00473-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23:175–204. doi: 10.1007/pl00011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Strohecker J, Grobovschek M. Spinal epidural abscess: an interdisciplinary emergency. Zentralbl Neurochir. 1986;47:120–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sanglard D, Odds FC. Resistance of Candida species to antifungal agents: molecular mechanisms and clinical consequences. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:73–85. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maubon D, Garnaud C, Calandra T, Sanglard D, Cornet M. Resistance of Candida spp. to antifungal drugs in the ICU: where are we now? Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1241–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tanaka A, Takahashi J, Hirabayashi H, Ogihara N, Mukaiyama K, Shimizu M, Hashidate H, Kato H. A Case of pyogenic spondylodiscitis caused by Campylobacter fetus for which early diagnosis by magnetic resonance imaging was difficult. Asian Spine J. 2012;6:274–278. doi: 10.4184/asj.2012.6.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 29 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data will be made available upon reasonable request.

The authors declare that code for data analysis will be made available upon reasonable request.