Summary

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) have an increased fracture risk. Exploring biomarkers for early bone loss detection is of great interest.

Methods

Pre-planned substudy of the ARNEO-trial (NCT03080116): a double blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial performed in high-risk PCa patients without bone metastases between March 2019 and April 2021. Patients were 1:1 randomised to treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (degarelix) + androgen receptor signalling inhibitor (ARSI; apalutamide) versus degarelix + matching placebo for 12 weeks prior to prostatectomy. Before and following ADT, serum and 24-h urinary samples were collected. Primary endpoints were changes in calcium-phosphate homeostasis and bone biomarkers.

Findings

Of the 89 randomised patients, 43 in the degarelix + apalutamide and 44 patients in the degarelix + placebo group were included in this substudy. Serum corrected calcium levels increased similarly in both treatment arms (mean difference +0.04 mmol/L, 95% confidence interval, 0.02; 0.06), and parathyroid hormone and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels decreased. Bone resorption markers increased, and stable calcium isotope ratios reflecting net bone mineral balance decreased in serum and urine similarly in both groups.

Interpretation

This exploratory substudy suggests that 12 weeks of ADT in non-metastatic PCa patients results in early bone loss. Additional treatment with ARSI does not seem to more negatively influence bone loss in the early phase. Future studies should address if these early biomarkers are able to predict fracture risk, and can be implemented in clinical practice for follow-up of bone health in PCa patients under ADT.

Funding

Research Foundation Flanders; KU Leuven; University-Hospitals-Leuven.

Keywords: Androgen deprivation therapy, Androgen receptor signalling inhibitor, Bone turnover marker, Prostate cancer, Stable calcium isotope

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The Medline database was searched through Pubmed up to February 24, 2023, for publications using various combinations of the following terms: “prostate cancer”, “androgen deprivation therapy”, “degarelix”, “androgen receptor inhibitor”, “androgen receptor signalling inhibitor”, “apalutamide”, “sex steroid”, “bone”, “bone turnover”, “bone turnover marker”, “stable calcium isotopes”, “osteoporosis”, “bone mineral density”, “dual x-ray absorptiometry”, and “fracture”. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) increases fracture risk in prostate cancer (PCa) patients. However, bone health in PCa patients is often neglected in clinical practice, and assessing fracture risk is not always straightforward, with changes in bone density only occurring after 6–12 months of ADT resulting in a possible missed window of early bone treatment opportunity. Moreover, addition of potent androgen receptor signalling inhibitors (ARSI) might increase fracture risk, but data on these drugs are scarce. Early changes of non-invasive biomarkers of bone and mineral homeostasis in PCa patients treated with combined ADT and ARSI have not been investigated yet. Moreover, markers of bone formation and bone resorption do not reflect the net bone mineral balance.

Added value of this study

In this pre-planned substudy, we showed that bone loss occurs already after 12 weeks of ADT in PCa patients. The setting of absence of bone metastases, and combination of sex steroid deprivation (degarelix) with or without direct androgen receptor inhibition (apalutamide), provided direct pathophysiological insights into the role of androgen receptor signalling in bone and mineral balance. We showed a large decrease in stable calcium isotope ratio in both serum and urine after treatment reflecting the early net negative bone mineral balance.

Implications of all the available evidence

ADT results in bone loss as early as after 12 weeks in non-metastasised PCa patients. These findings emphasise the importance of bone-health-awareness in PCa patients as early as ADT is started. Addition of ARSI does not lead to more bone loss in the early phase compared to degarelix alone as evidenced by a similar decrease in stable calcium isotope ratios, reflecting the net negative bone mineral balance. Future studies should address if rapid changes in these non-invasive biomarkers are able to predict fracture risk and can be implemented in clinical practice for early screening and follow-up of bone health in PCa patients under drugs interfering with androgen signalling.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most frequent cancer among men worldwide, with more than 1.4 million new cases diagnosed in 2020, accounting for 14.1% of all cancers in men.1 One of the cornerstones of PCa treatment is androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), widely used in clinical practice in metastatic, but also in locally advanced disease.2 Usually, hypogonadism is attained chemically by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-agonists or -antagonists. More recently, newer agents directly targeting androgen receptor signalling have been introduced both in combination with chemical castration as in monotherapy.3 Moreover, the use of these newer agents in the neo-adjuvant setting has gained increasing interest in the past years.4

PCa patients receiving ADT are at increased risk of osteoporotic fractures.5 PCa patients treated with a GnRH-agonist have about 50% and 30% increased risk of vertebral and hip fracture compared to non-ADT-treated patients, respectively.6 Compared to non-PCa controls, PCa patients under ADT have an increased risk of any fracture of 40% and hip fracture of 38%.7 Androgen receptor signalling inhibitors (ARSI) such as apalutamide, darolutamide and enzalutamide may increase risk of falls and fractures in combination with or compared to GnRH-therapy alone. However, data on bone health of these newer drugs remain limited.8, 9, 10 Importantly, fractures inversely correlate with overall survival in PCa patients; overall mortality risk increases with 38% in PCa patients experiencing a fracture.11

Guidelines from both urological and endocrinological societies advice routine screening for bone health in PCa patients treated with ADT.2,12,13 Dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) should be performed before start of long-term ADT and regularly during treatment. In addition to DXA, fracture risk assessment score (FRAX) can help identify patients at greater fracture risk and guide treatment.14,15 However, despite increasing prevalence of screening over the past years, actual compliance to bone health-screening according to the guidelines remains rather low in clinical practice. A report from a large healthcare insurance database showed that only one out of four PCa patients initiating ADT received DXA around start of ADT.16 As a result, only a minority of patients receives adequate and timely treatment in case of poor bone health.17

A major drawback of evaluating bone health in PCa patients with DXA is the fact that, due to the sensitivity, changes in bone mineral density (BMD) only occur as early as 6–12 months after initiation of ADT.18,19 Consequently, the delay in changes in BMD may potentially result in a missed window of early treatment opportunity. Early treatment is especially important because bone loss secondary to ADT is shown to be most pronounced in the first year.18 Therefore, exploring biomarkers which can reliably detect early bone loss are of great interest.

The aim of this exploratory substudy was to investigate if we could detect bone loss already at an early time point with biomarkers in serum or urine which have potential for implementation in screening and follow-up of bone health of PCa patients in clinical practice. We explored the use of stable calcium isotope ratios which, in contrast to conventional serum markers of bone formation and resorption, give information about the net bone mineral balance (BMB). Additionally, we aimed to explore differential effects of monotherapy with GnRH-antagonist or combination treatment with apalutamide on early changes in bone and mineral homeostasis.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was performed as a pre-planned substudy on changes in biomarkers of bone and mineral homeostasis in patients who were included in the ARNEO (ARN-509 NEOadjuvant) trial (NCT03080116), an investigator-initiated, single centre (University Hospitals Leuven), randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial.20,21 Patients were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to degarelix (GnRH-antagonist: 240-80-80 mg) + apalutamide (ARSI: 240 mg/d) versus degarelix (240-80-80 mg) + matching placebo for 12 weeks (3 cycles of 4 weeks). Detailed description of patient eligibility, and inclusion and exclusion criteria have been published previously and are provided as Supplementary material.21 In brief, PCa patients with high-risk disease that were amenable to radical prostatectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection were screened. Patients had no signs of metastatic disease on bone scintigraphy and cross-sectional pelvic MRI and/or CT-scan prior to inclusion. Morning blood sample and 24-h urinary collection were obtained prior to start of medical therapy and after 12 weeks. At baseline visit patients were asked to fill in a calcium intake questionnaire, estimating daily dietary calcium intake. Medical history of the patients was reviewed for presence of fractures, diabetes mellitus and current drug use. Chronic disease score was calculated.22 Of the 89 patients randomly assigned to the 2 treatment arms (degarelix + apalutamide: n = 45 and degarelix + matching placebo: n = 44) in the main trial, 2 patients were additionally excluded in this substudy (Fig. 1). One patient developed a serious adverse event (drug-induced interstitial lung disease) and did not continue 12 weeks of ADT, and another patient had biochemical diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism at baseline.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram. ∗ Excluded: Not meeting inclusion criteria ARNEO trial (n = 24) (low-risk or favorable intermediate-risk PCa (n = 7), medications influencing PSA levels (n = 5), cM1 disease on conventional imaging (n = 5), history of prior malignancy within 5y prior to randomization (n = 3), ECOG >1 (n = 2), contraindication for MRI (n = 1), previous surgical treatment of the prostate (n = 1)), refused to participate (n = 12), preferred radiotherapy as local treatment (n = 11), informed consent withdrawn (n = 1). ∗∗ Severe adverse advent for which the patient did not complete 12 weeks of hormonal treatment. ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, PHP = primary hyperparathyroidism.

Biochemical analysis

Sex steroids and related biochemistry

Total testosterone, androstenedione, and oestradiol were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).23,24 Values of testosterone and oestradiol below the lower limit of quantification (LOQ) of 2.5 ng/dL and 2.5 ng/L, respectively, were reported as the LOQ. Sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and prolactin were measured using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) (COBAS 8000, Roche Diagnostics). Values of LH and FSH below the lower limit of detection (LOD) of 0.3 IU/L were reported as the LOD. Free testosterone and free oestradiol were calculated using the Vermeulen formula.25 Creatinine, albumin, and urea were determined using a colorimetric method (COBAS 8000, Roche Diagnostics). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-EPI formula.26 Male laboratory reference ranges are provided in Supplementary Table S5.

Calcium-phosphate homeostasis

Calcium and phosphate in serum and urine were measured using a colorimetric method (COBAS 8000, Roche Diagnostics). Calcium was corrected for albumin using the following formula: calciumserum+0.8∗(4-albumin). Fractional calcium excretion (FE calcium) was calculated using the following formula (creatinineserum∗calciumurine)/(creatinineurine∗calciumserum). Fractional phosphate excretion (FE phosphate) was calculated similarly. 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OHD), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2D3), and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (24,25-(OH)2D3) were measured by LC-MS/MS.27,28 Vitamin D-binding protein (DBP) was measured by single radial immunodiffusion.29 Free vitamin D levels were calculated using the Vermeulen formula.25 Parathyroid hormone (PTH) 1–84 was measured using ECLIA (COBAS 8000, Roche Diagnostics). Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) was measured by Liaison automate (Diasorin, Saluggia, Italy).

Bone turnover and mineral balance

C-terminal telopeptide of collagen (CTx), tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRAcP5b), intact procollagen type I N-propeptide (PINP), and bone alkaline phosphate (BAP) were determined with the IDS iSYS platform (Boldon, UK). Measurement of sclerostin was performed by enzyme-linked immune-assay (TECO medical, Sissach, Switzerland). Stable calcium isotope measurements (ratio δ44/42Ca) in serum and urine were performed on a MC-ICP-MS (Neptune plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at the mass spectrometer facilities of the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany.30,31 Stable calcium isotope ratios (δ44/42Ca) were corrected for calcium supplement intake (n = 2).31,32

Ethics

This study was in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and was approved by the local ethical review board of the University Hospitals Leuven (S63579). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Statistical analysis

The primary aim of this exploratory substudy was to investigate differences in calcium-phosphate homeostasis and bone biomarkers after 12 weeks of treatment compared to baseline values. As secondary aim differences between both treatment arms after 12 weeks were explored. The sample size was fixed due to dependency of patients included in the parent trial.4 Based on our previous study where a mean difference of 0.14 mmol ± 0.11 in serum calcium levels was observed after a median time of 13 weeks of ADT33; to achieve a power of 90% with a level of significance of 5%, at least 10 number of pairs needed to be included. Missing data were due to sample availability, and were excluded from analysis. Continuous data are represented as median [interquartile range] in Table 1 and mean [95% CI] elsewhere. Proportions are shown as % (n). Differences before and after treatment were evaluated by repeated measurement two-way ANOVA or mixed-effects analysis in case of missing values followed by Fishers Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Differences were expressed as estimated (Least Squares) mean differences [95% CI]. Correlations were explored using Pearson correlation. Given the exploratory nature of the study, no adjustment for multiple testing was performed. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v9.5.0 (La Jolla, USA).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the substudy.

| degarelix + placebo | degarelix + apalutamide | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 44 | 43 |

| Age (y) | 67.38 [62.76–70.35] | 66.91 [61.48–70.84] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.79 [24.63–28.54] | 26.76 [24.64–29.89] |

| Ca intake (mg/day) | 765.0 [540.0–1024.0] | 675.0 [472.5–900.0] |

| Smoking | ||

| Never | 29.5 (13) | 27.9 (12) |

| Active | 52.3 (23) | 55.8 (24) |

| Unknown | 18.2 (8) | 16.3 (7) |

| All fractures (>6 mo) | 18.2 (8) | 16.3 (7) |

| Therapy for bone health | ||

| Antiresorptive drugs | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Calcium supplement | 2.3 (1) | 2.3 (1) |

| Vitamin D supplement | 0 (0) | 2.3 (1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11.4 (5) | 9.3 (4) |

| Chronic Disease Score | ||

| 0 | 36.4 (16) | 37.2 (16) |

| 1–3 | 20.5 (9) | 32.6 (14) |

| 4 or more | 43.2 (19) | 30.2 (13) |

Continuous data are represented as median [interquartile range]. Proportions are visualised as percentage (absolute number). BMI = body mass index.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of patients in both treatment arms are shown in Table 1. Patients had similar age and body mass index (BMI). None of the patients suffered from a recent (<6 months) fracture, and history of previous fractures was similar in both groups. None of the patients was on antiresorptive treatment and supplementation of calcium and vitamin D was low. Median calcium intake was <1000 mg/day in both groups.

Sex steroids levels and related biochemistry

Testosterone and oestradiol levels decreased after 12 weeks of treatment into castrate range (Fig. 2). Free sex steroid levels also decreased. There was no difference in total and free levels of testosterone and oestradiol between the 2 treatment arms (Supplementary Table S1). LH and FSH levels decreased in both groups (Supplementary Table S1). There was evidence of effect for SHBG between groups with SHBG seaming to increase in the degarelix + apalutamide group whilst remaining unchanged in the degarelix + matching placebo group (Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Sex steroid levels before and after ADT. Data are visualized as mean 95% CI. Black filled dots: degarelix + matching placebo (n = 44), green open dots: degarelix + apalutamide (n = 43).

Calcium-phosphate homeostasis

As shown in Fig. 3, serum albumin-corrected calcium levels increased under ADT (+0.04 mmol/L 95% CI [0.02; 0.06] for both treatment groups), along with increased urinary calcium and FE calcium. Serum phosphate levels increased, FE phosphate decreased and FGF23 levels remained unchanged. PTH and 1,25-(OH)2D3 decreased, DBP increased, while 25-(OH)D levels remained unaltered. The majority of patients had normal 25-(OH)D levels of >20 μg/L. There were no differences in calcium-phosphate homeostasis between the 2 treatment arms after treatment and renal function (serum creatinine, eGFR or urea) did not change (Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 3.

Calcium-phosphate homeostasis before and after ADT. Data are visualized as mean 95% CI. Black filled dots: degarelix + matching placebo (n = 44), green open dots: degarelix + apalutamide (n = 43). Calciumalbcor = albumin-corrected calcium, UCalcium = 24 h urinary calcium, FE = fractional excretion, PTH = parathyroid hormone, FGF23 = fibroblast growth factor 23, 25-(OH)D = 25-hydroxy vitamin D, 1,25-(OH)2D3 = 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, 24, 25-(OH)2D3 = 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, DBP = vitamin D binding protein.

Bone turnover and mineral balance

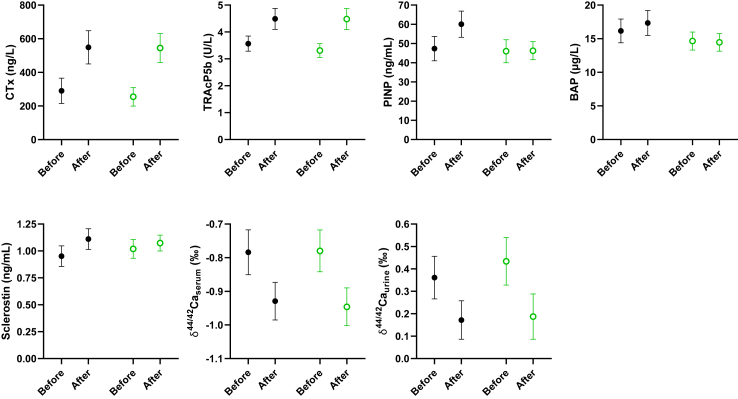

Serum bone resorption markers CTx and TRAcP5b increased (Fig. 4). There were no differences in bone resorption markers between the 2 treatment arms (Supplementary Table S3). Bone formation marker PINP increased in the degarelix + matching placebo group, resulting in an estimated difference between the 2 treatment arms of 14.01 ng/mL 95% CI [5.68; 22.34] after treatment (Supplementary Table S3). BAP was higher in the degarelix + matching placebo group after treatment compared to the degarelix + apalutamide group as well (Supplementary Table S3). Sclerostin levels were not different between both groups after treatment (Supplementary Table S3). The stable calcium isotope ratio (δ44/42Ca) decreased in serum with 20% and in urine with over 50% (Fig. 4). The stable calcium isotope ratio after treatment in serum and urine was similar in both treatment arms, suggestive for a similar net negative BMB in both groups (Supplementary Table S3). Correlations between the different bone turnover markers and stable calcium isotope ratios are shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S4.

Fig. 4.

Bone turnover and mineral balance before and after ADT. Data are visualized as mean 95% CI. Black filled dots: degarelix + matching placebo (n = 44), green open dots: degarelix + apalutamide (n = 43). CTx = C-terminal telopeptide of collagen, TRAcP5b = tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b, PINP = procollagen type I N-propeptide, BAP = bone alkaline phosphatase, δ44/42Caserum = stable calcium isotope ratio serum, δ44/42Caurine = stable calcium isotope ratio urine.

Fig. 5.

Correlation between bone markers after ADT. Pearson correlation with 95% CI. Black filled dots: degarelix + matching placebo (n = 44), green open dots: degarelix + apalutamide (n = 43). CTx = C-terminal telopeptide of collagen, TRAcP5b = tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b, PINP = procollagen type I N-propeptide, δ44/42Caserum = stable calcium isotope ratio serum, δ44/42Caurine = stable calcium isotope ratio urine, FE = fractional excretion.

Discussion

The unique setting of this study, in male patients with high-risk localised PCa prior to and 12 weeks after 2 modalities of medically interfering with androgen signalling, provides pathophysiological insights into direct androgen action on the male skeleton. These exploratory findings show that bone loss occurs already very early after the start of ADT. The negative BMB is demonstrated by a decrease in stable calcium isotope ratios in serum and urine. Additionally, bone resorption markers increase, as well as serum calcium levels and urinary calcium excretion.

Our findings of PTH-independent increase of serum calcium levels and urinary calcium excretion are consistent with early accelerated bone loss in postmenopausal women.34 The increase in serum calcium results in decreased PTH, which in its turn will lead to lower renal conversion of 25-(OH)D into active 1,25-(OH)2D3 (Fig. 6). This mechanism occurs even in the presence of a low calcium intake. These findings are also in accordance with our study in a small cohort of hypersexual men treated with anti-androgen cyproterone acetate (less potent and specific compared to apalutamide) for a median time of 13 weeks.33

Fig. 6.

Schematic overview of the pathophysiology of early ADT-induced bone loss. Early sex steroid deficiency, mainly oestrogen deficiency, induced by treatment with degarelix results in increased bone resorption followed by increased bone formation. The early hypogonadal bone loss leads to calcium efflux from the bone and results in increased serum calcium levels with secondary decreased PTH and 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels and increased urinary calcium excretion. Serum bone turnover markers (both resorption and formation) are increased. The stable calcium isotope ratio, representing the net mineral balance, is decreased both in serum and urine. In the group additionally receiving apalutamide, the increase in serum bone resorption markers is not accompanied by an increase in bone formation markers, which could suggest a delay in the coupling of bone resorption and formation. The mineral balance as expressed by the stable calcium isotope ratio decreases similarly, suggestive for a similar early bone loss in both groups. AR = androgen receptor, ER = oestrogen receptor, CTx = C-terminal telopeptide of collagen, TRAcP5b = tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b, PINP = procollagen type I N-propeptide, BAP = bone alkaline phosphatase, δ44/42Ca = stable calcium isotope ratio, PTH = parathyroid hormone, 1,25-(OH)2D3 = 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3. Created with BioRender.com.

The adult human skeleton is constantly being remodelled (bone turnover) with bone resorption followed by formation (Fig. 6).35 The coupling between bone resorption and formation takes place in bone remodelling units consisting of both osteoclasts (resorption) and osteoblasts (formation). In humans, bone resorption takes about 3 weeks, while bone formation takes up to 3 months. CTx and TRAcP5b are markers reflecting bone resorption, while PINP and BAP reflect bone formation. Bone turnover markers have been used widely, both in research and in clinical practice, mainly in the setting of postmenopausal osteoporosis.35 However, none of these markers provide information about net bone loss. In early postmenopausal osteoporosis, due to oestrogen deficiency, bone turnover increases with a greater number of bone remodelling units, resulting in a remodelling imbalance and bone loss.36 Several elegant trials confirmed that oestrogens are the dominant sex steroids regulating bone resorption in sex steroid deprived-men as well.37,38

In the setting of PCa patients under ADT, increase of both bone resorption and formation markers have been reported after 6 months, with further increase after 12 months.18,39 Importantly, these studies were conducted using GnRH-agonists, while here degarelix is used, which does not result in an initial flare of sex steroid levels.40,41 There are no head-to-head studies evaluating difference in early changes of bone turnover after GnRH-agonist versus -antagonist treatment. A small study showed that degarelix monotherapy results in a similar increase in bone turnover markers after 6 and 12 months, and decline in BMD after 12 months.42 Here, we show increase of bone resorption markers CTx and TRAcP5b already after 12 weeks. In contrast, bone formation marker PINP only increased in the matching placebo group after 12 weeks. Effects of ARSI on changes in bone turnover have not been extensively investigated yet. Different studies with older anti-androgens flutamide and bicalutamide alone or in combination with conventional castration confirm increase in bone resorption markers, but are conflicting concerning bone formation markers with some showing increase while others show no change.19,43, 44, 45, 46 BAP increased after 1 year of enzalutamide monotherapy.47 In the SPARTAN trial apalutamide appeared to further increase fracture risk in PCa patients receiving long-term ADT (11.7% vs. 6.5%),48 suggesting an additional role for extragonadal androgens. Inhibition of extragonadal sex steroid signalling is also believed to contribute to the increased fracture risk in postmenopausal women with breast cancer under aromatase inhibitors.49 Conversely, the lower level of bone formation markers at 12 weeks in our study could also reflect a difference in coupling kinetics and thus a delay in bone formation without effect on net bone loss in the long-term.

In contrast to the previously discussed biomarkers of bone formation and bone resorption, stable calcium isotope ratios (δ44/42Ca) provide information on the net BMB.30 In brief, calcium is composed of different stable, naturally occurring isotopes ranging from atomic mass 40 to 48. Following principles of kinetic isotope fractionation, when calcium is incorporated into the bone, preferentially lighter isotopes become enriched, resulting in increasing 44Ca/42Ca ratios (expressed as δ44/42Ca) in serum and urine. Consequently, in situations where bone formation exceeds bone resorption (positive BMB) the δ44/42Ca will increase, while in situations of a negative BMB the δ44/42Ca will decrease. The serum isotope ratio is positively correlated with T-score on DXA scan in postmenopausal women, and also tibial BMD by peripheral quantitative computed tomography in children and young adults.30,32 The calcium isotope ratio before treatment in the PCa patients in this study indicates that calcium absorption and resorption are balanced.32 After 12 weeks of ADT a large decrease in stable calcium isotope ratio is observed, both in serum and urine. Additionally, there is a moderate and strong correlation between δ44/42Caurine and bone resorption marker CTx and fractional calcium excretion after treatment, respectively. Despite discrepancy in changes in bone formation markers between the 2 treatment arms, no differences in δ44/42Ca were observed, suggesting that addition of ARSI to chemical castration does not result in a more negative BMB in the early phase of treatment. Future studies should address if the stable calcium isotope ratios correlate with DXA measurements in PCa patients, assess cut-offs for bone treatment, and evaluate if the stable calcium isotopes represent a biomarker that can be used to predict fracture risk. Additionally, the potential of stable calcium isotopes as biomarker for the early diagnosis of bone metastases deserves exploration.

Our study is not free from limitations. We show changes in different markers at 12 weeks, but do not have any information at later timepoints, nor do we have information on DXA or fracture incidence. Dietary calcium intake was low, and although the majority had 25-OH vitamin D levels >20 μg/L some patients were vitamin D-deficient at start of ADT. Additionally, this is an exploratory substudy of a phase 2 study and the findings warrant confirmation in future trials. Our study has several strengths. We show changes in bone and mineral homeostasis in non-metastatic PCa patients with state-of-the-art non-invasive measurements and techniques in both serum and urine. The setting of absence of bone metastases, and combination of sex steroid deprivation with or without direct androgen receptor inhibition provides direct pathophysiological insights into sex steroid action on bone homeostasis and mineral balance. We show differences already occurring at a very early timepoint, as early as at the end of one remodelling cycle, showing the importance of bone-health-awareness in PCa patients under ADT and potent ARSI, increasingly used also in the neo-adjuvant setting.

This exploratory substudy shows that ADT results in bone loss as early as after 3 months in non-metastasized PCa patients, suggested by PTH-independent increase of serum calcium levels and urinary calcium excretion, and increased bone resorption markers. We show a large decrease in stable calcium isotope ratios both in serum and urine, reflecting the early negative BMB. Addition of ARSI does not seem to lead to more bone loss in the early treatment phase compared to chemical castration alone. These findings emphasize the importance of bone-health-awareness in PCa patients as early as ADT is started. Future studies should address if these non-invasive biomarkers are able to predict fracture risk and can be implemented in clinical practice for early screening and follow-up of bone health in PCa patients treated with ADT.

Contributors

Study concept and design: DV, FC, SJ and BD. Funding: DV, FC, SJ and BD. Sample collection and processing: KD, LD and DS. Measurements of bone turnover markers: EC. Measurements and interpretation of δ44/42Ca: AE. Statistical analysis and figures: KD, DV, FC and BD. Verification underlying data and first draft of manuscript: KD and BD. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KD, GD, NN, LA, WD, LD, DS, AE, EC, DV, FC, SJ and BD. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The individual-level data used in this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical approval. Data set will be made available upon request through contact with the corresponding author. For sharing of data within a scientific collaboration any proposal should be directed to the corresponding author. Data will only be shared in accordance with legal frameworks, and when the integrity of the individual study participant can be guaranteed. This will be decided by the corresponding author on a case-by-case basis.

Declaration of interests

LA participated on advisory boards for Galapagos/Gilead, Simple Pharma and Merck. LA receives a Senior Clinical Investigator Fellowship from Flanders Research Foundation (FWO 1800923N). AE is founder of the Osteolabs GmbH, Kiel, Germany. EC received consulting fees from DiaSorin, IDS, Fujirebio, Nittobo, bioMérieux and Werfen. SJ received consulting fees and support for attending meetings, honoraria for lectures and participated in monitoring and advisory boards of Ipsen, Bayer, Astellas, Janssen and Ferring.

Acknowledgements

KD receives a PhD fellowship Fundamental Research from Flanders Research Foundation (FWO 1196522N). SJ received support from Janssen and Ferring for the study drugs. This work was funded by FWO research grant (G099518N), by KOOR grant University Hospitals Leuven (S63579) and by KU Leuven grant (C14/19/100).

We thank the clinical trial nurses of the department of Urology of the University Hospitals Leuven for their logistic support. We thank Annouschka Laenen for the statistical advice and support provided.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104817.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mottet N., van den Bergh R.C.N., Briers E., et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2021;79(2):243–262. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitsiades N., Kaochar S. Androgen receptor signaling inhibitors: post-chemotherapy, pre-chemotherapy and now in castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;28(8):T19–T38. doi: 10.1530/ERC-21-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devos G., Devlies W., De Meerleer G., et al. Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy before radical prostatectomy in high-risk prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18(12):739–762. doi: 10.1038/s41585-021-00514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahinian V.B., Kuo Y.F., Freeman J.L., Goodwin J.S. Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(2):154–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith M.R., Lee W.C., Brandman J., Wang Q., Botteman M., Pashos C.L. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and fracture risk: a claims-based cohort study of men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7897–7903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.6908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallander M., Axelsson K.F., Lundh D., Lorentzon M. Patients with prostate cancer and androgen deprivation therapy have increased risk of fractures-a study from the fractures and fall injuries in the elderly cohort (FRAILCO) Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(1):115–125. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4722-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussain A., Tripathi A., Pieczonka C., et al. Bone health effects of androgen-deprivation therapy and androgen receptor inhibitors in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;24(2):290–300. doi: 10.1038/s41391-020-00296-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myint Z.W., Momo H.D., Otto D.E., Yan D., Wang P., Kolesar J.M. Evaluation of fall and fracture risk among men with prostate cancer treated with androgen receptor inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouleftour W., Boussoualim K., Sotton S., et al. Second-generation hormonotherapy in prostate cancer and bone microenvironment. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;28(8):T39–T49. doi: 10.1530/ERC-21-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao Y.H., Moore D.F., Shih W., Lin Y., Jang T.L., Lu-Yao G.L. Fracture after androgen deprivation therapy among men with a high baseline risk of skeletal complications. BJU Int. 2013;111(5):745–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watts N.B., Adler R.A., Bilezikian J.P., et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802–1822. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cianferotti L., Bertoldo F., Carini M., et al. The prevention of fragility fractures in patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer: a position statement by the international osteoporosis foundation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(43):75646–75663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/index.aspx

- 15.Ye C., Morin S.N., Lix L.M., et al. Performance of FRAX in men with prostate cancer: a registry-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2023;38(5):659–664. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J., Aprikian A.G., Vanhuyse M., Dragomir A. Contemporary population-based analysis of bone mineral density testing in men initiating androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(10):1374–1381. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt A., Khan M.A., Gujja S., Govindarajan R. Utilization of bone densitometry for prediction and administration of bisphosphonates to prevent osteoporosis in patients with prostate cancer without bone metastases receiving antiandrogen therapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2015;7:13–18. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S74116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenspan S.L., Coates P., Sereika S.M., Nelson J.B., Trump D.L., Resnick N.M. Bone loss after initiation of androgen deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(12):6410–6417. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura T., Koike Y., Aikawa K., et al. Short-term impact of androgen deprivation therapy on bone strength in castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2019;26(10):980–984. doi: 10.1111/iju.14077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tosco L., Laenen A., Gevaert T., et al. Neoadjuvant degarelix with or without apalutamide followed by radical prostatectomy for intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer: ARNEO, a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):354. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4275-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devos G., Tosco L., Baldewijns M., et al. ARNEO: a randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant degarelix with or without apalutamide prior to radical prostatectomy for high-risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2022;83(6):508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Von Korff M., Wagner E.H., Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90016-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antonio L., Pauwels S., Laurent M.R., et al. Free testosterone reflects metabolic as well as ovarian disturbances in subfertile oligomenorrheic women. Int J Endocrinol. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/7956951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauwels S., Antonio L., Jans I., et al. Sensitive routine liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for serum estradiol and estrone without derivatization. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013;405(26):8569–8577. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vermeulen A., Verdonck L., Kaufman J.M. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(10):3666–3672. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H., et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casetta B., Jans I., Billen J., Vanderschueren D., Bouillon R. Development of a method for the quantification of 1alpha,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 in serum by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry without derivatization. Eur J Mass Spectrom (Chichester) 2010;16(1):81–89. doi: 10.1255/ejms.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cools M., Goemaere S., Baetens D., et al. Calcium and bone homeostasis in heterozygous carriers of CYP24A1 mutations: a cross-sectional study. Bone. 2015;81:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouillon R., Vandoren G., Van Baelen H., De Moor P. Immunochemical measurement of the vitamin D-binding protein in rat serum. Endocrinology. 1978;102(6):1710–1715. doi: 10.1210/endo-102-6-1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenhauer A., Müller M., Heuser A., et al. Calcium isotope ratios in blood and urine: a new biomarker for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Bone Rep. 2019;10 doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2019.100200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shroff R., Lalayiannis A.D., Fewtrell M., et al. Naturally occurring stable calcium isotope ratios are a novel biomarker of bone calcium balance in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022;102(3):613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shroff R., Fewtrell M., Heuser A., et al. Naturally occurring stable calcium isotope ratios in body compartments provide a novel biomarker of bone mineral balance in children and young adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36(1):133–142. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalil R., Antonio L., Laurent M.R., et al. Early effects of androgen deprivation on bone and mineral homeostasis in adult men: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183(2):181–189. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riggs B.L., Khosla S., Melton L.J. Sex steroids and the construction and conservation of the adult skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(3):279–302. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schini M., Vilaca T., Gossiel F., Salam S., Eastell R. Bone turnover markers: basic biology to clinical applications. Endocr Rev. 2022;44(3):417–473. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnac031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almeida M., Laurent M.R., Dubois V., et al. Estrogens and androgens in skeletal physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(1):135–187. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finkelstein J.S., Lee H., Leder B.Z., et al. Gonadal steroid-dependent effects on bone turnover and bone mineral density in men. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(3):1114–1125. doi: 10.1172/JCI84137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falahati-Nini A., Riggs B.L., Atkinson E.J., O'Fallon W.M., Eastell R., Khosla S. Relative contributions of testosterone and estrogen in regulating bone resorption and formation in normal elderly men. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(12):1553–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI10942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilton E.J., Ghasem-Zadeh A., Gianatti E., et al. Structural decay of bone microarchitecture in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):E456–E463. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huhtaniemi I., Nikula H., Rannikko S. Pituitary-testicular function of prostatic cancer patients during treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist analog. I. Circulating hormone levels. J Androl. 1987;8(6):355–362. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.1987.tb00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broqua P., Riviere P.J., Conn P.M., Rivier J.E., Aubert M.L., Junien J.L. Pharmacological profile of a new, potent, and long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist: degarelix. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301(1):95–102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palumbo C., Dalla Volta A., Zamboni S., et al. Effect of degarelix administration on bone health in prostate cancer patients without bone metastases. The Blade Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(12):3398–3407. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.García-Fontana B., Morales-Santana S., Varsavsky M., et al. Sclerostin serum levels in prostate cancer patients and their relationship with sex steroids. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(2):645–651. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith M.R., Goode M., Zietman A.L., McGovern F.J., Lee H., Finkelstein J.S. Bicalutamide monotherapy versus leuprolide monotherapy for prostate cancer: effects on bone mineral density and body composition. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2546–2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamada Y., Takahashi S., Fujimura T., et al. The effect of combined androgen blockade on bone turnover and bone mineral density in men with prostate cancer. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(3):321–327. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishizaki F., Hara N., Takizawa I., et al. Deficiency in androgens and upregulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 are involved in high bone turnover in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2012;22(3-4):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tombal B., Borre M., Rathenborg P., et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of enzalutamide monotherapy in hormone-naïve prostate cancer: 1- and 2-year open-label follow-up results. Eur Urol. 2015;68(5):787–794. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith M.R., Saad F., Chowdhury S., et al. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1408–1418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramchand S.K., Cheung Y.M., Yeo B., Grossmann M. The effects of adjuvant endocrine therapy on bone health in women with breast cancer. J Endocrinol. 2019;241(3):R111–R124. doi: 10.1530/JOE-19-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.