Key Points

Question

Does adding treatment with a high-frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation device to a standard postoperative pharmacologic analgesia regimen decrease opioid use among patients following cesarean delivery?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 134 individuals who underwent a cesarean delivery, those treated with the functional device used 47% less opioid medication while an inpatient and were prescribed fewer opioids at discharge than those who received treatment with the sham device.

Meaning

These findings suggest that use of a high-frequency electrical stimulation device as part of a multimodal analgesic protocol after cesarean delivery decreases opioid use throughout the postoperative recovery period without compromising pain control.

Abstract

Importance

Improved strategies are needed to decrease opioid use after cesarean delivery but still adequately control postoperative pain. Although transcutaneous electrical stimulation devices have proven effective for pain control after other surgical procedures, they have not been tested as part of a multimodal analgesic protocol after cesarean delivery, the most common surgical procedure in the United States.

Objective

To determine whether treatment with a noninvasive high-frequency electrical stimulation device decreases opioid use and pain after cesarean delivery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

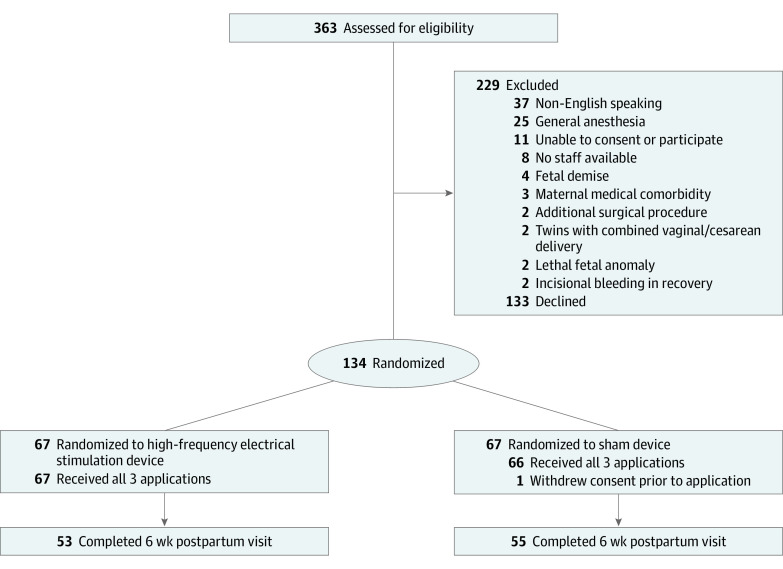

This triple-blind, sham-controlled randomized clinical trial was conducted from April 18, 2022, to January 31, 2023, in the labor and delivery unit at a single tertiary academic medical center in Ohio. Individuals were eligible for the study if they had a singleton or twin gestation and underwent a cesarean delivery. Of 267 people eligible for the study, 134 (50%) were included.

Intervention

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to a high-frequency (20 000 Hz) electrical stimulation device group or to an identical-appearing sham device group and received 3 applications at the incision site in the first 20 to 30 hours postoperatively.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was inpatient postoperative opioid use, measured in morphine milligram equivalents (MME). Secondary outcomes included pain scores, measured with the Brief Pain Inventory questionnaire (scale, 0-10, with 0 representing no pain), MME prescribed at discharge, and receipt of additional opioid prescriptions in the postpartum period. Normally distributed data were assessed using t tests; otherwise via Mann-Whitney or χ2 tests as appropriate. Analyses were completed following intention-to-treat principles.

Results

Of 134 postpartum individuals who underwent a cesarean delivery (mean [SD] age, 30.5 [4.6] years; mean [SD] gestational age at delivery, 38 weeks 6 days [8 days]), 67 were randomly assigned to the functional device group and 67 to the sham device group. Most were multiparous, had prepregnancy body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) higher than 30, were privately insured, and received spinal anesthesia. One participant in the sham device group withdrew consent prior to treatment. Individuals assigned to the functional device used significantly less opioid medication prior to discharge (median [IQR], 19.75 [0-52.50] MME) than patients in the sham device group (median [IQR], 37.50 [7.50-67.50] MME; P = .046) and reported similar rates of moderate to severe pain (85% vs 91%; relative risk [RR], 0.77 [95% CI, 0.55-1.29]; P = .43) and mean pain scores (3.59 [95% CI, 3.21-3.98] vs 4.46 [95% CI, 4.01-4.92]; P = .004). Participants in the functional device group were prescribed fewer MME at discharge (median [IQR], 82.50 [0-90.00] MME vs 90.00 [75.00-90.00] MME; P < .001). They were also more likely to be discharged without an opioid prescription (25% vs 10%; RR, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.08-2.13]; P = .03) compared with the sham device group. No treatment-related adverse events occurred in either group.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial of postoperative patients following cesarean delivery, use of a high-frequency electrical stimulation device as part of a multimodal analgesia protocol decreased opioid use in the immediate postoperative period and opioids prescribed at discharge. These findings suggest that the use of this device may be a helpful adjunct to decrease opioid use without compromising pain control after cesarean delivery.

This triple-blind randomized clinical trial assesses opioid medications dispensed and pain control following treatment with a high-frequency electrical stimulation device vs an identical-appearing sham device incorporated into the standard analgesic protocol for postoperative patients after cesarean delivery.

Introduction

Cesarean delivery is the most commonly performed major surgical procedure in the United States (US),1,2 and systemic opioids are almost universally used for postcesarean analgesia.3 More than 80% of individuals take at least 1 opioid medication for pain after cesarean, and 3%-6% of individuals who use opioids for acute pain after surgery develop chronic use, defined as continued use at 90 days postoperatively.4,5 Pain thresholds and analgesic requirements vary among patients, but most individuals are given prescriptions at discharge for at least 10 more opioid tablets than needed.4,6 The consequence of overprescribing opioids to this degree for 1.2 million cesarean deliveries annually is at least 12 million unused opioid tablets.7 Those unused tablets often go unguarded or are not disposed of properly, providing an important reservoir of opioids that may be misused, diverted, or accidentally ingested, contributing to the opioid crisis.6,8,9,10 Growing recognition of the role that postcesarean opioid prescribing plays in the opioid crisis has led to a search for alternative methods to control postoperative pain.3,11

Health care professionals today struggle to balance the need for adequate control of acute pain after surgery with the desire to limit opioid use and avoid overprescribing, development of dependence, and diversion.3,5,12,13 The use of multimodal analgesia to control postoperative pain can decrease opioid requirements.3,14,15,16 Multimodal analgesia protocols typically emphasize use of scheduled nonopioid analgesics (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen), with opioid analgesics as needed for breakthrough pain.3,14,17,18 However, the use of nonpharmacologic treatments and novel devices remain underexplored for postcesarean pain control.18,19

Electrical nerve stimulation represents a promising adjunctive therapy.20,21 Originally used for chronic pain, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has been shown to reduce acute pain and opioid requirements postoperatively in several settings, although most previously studied devices deliver current at a relatively low (≤100 Hz) frequency20,22,23 TrueRelief is a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared bioelectronic device for postsurgical pain management that delivers pulsed-direct electrical current at a frequency of 20 000 Hz transcutaneously via stainless steel probes and may reduce pain by targeting sensory neurons and inhibiting the release of neuroinflammatory mediators.24,25 Efficacy of this device for pain control after cesarean delivery remains underexplored, but we hypothesized that it may represent an important adjunct to improve pain control while reducing opioid use.

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether the addition of a noninvasive bioelectronic treatment to a multimodal postcesarean analgesic regimen reduces inpatient postcesarean opioid consumption compared with use of a sham device.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We conducted this triple-blind, sham-controlled randomized clinical trial at a single academic medical center with approximately 5000 infant deliveries per year. Individuals were eligible for the study if they had a singleton or twin gestation between 22 and 42 gestational weeks and underwent a cesarean delivery, whether scheduled or unscheduled. Exclusion criteria included a known history of opioid use disorder, general anesthesia, allergy or contraindication to opioids, allergy or contraindication to both acetaminophen and ibuprofen, additional significant surgical procedures prior to randomization, twin gestation with combined vaginal and cesarean delivery, fetal or neonatal death prior to randomization, primary language other than English, participation in another intervention study that influenced the primary outcome, or inability to participate in the noninvasive bioelectronic treatment as assessed by the research staff (D.D.M., B.K., and J.R.). Screening and enrollment were limited by research personnel availability due to the need to complete all 3 applications. The study protocol (Supplement 1) was approved by The Ohio State University (OSU) Institutional Review Board prior to the start of enrollment. All participants provided written informed consent prior to or immediately following cesarean delivery. We followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline for the reporting of this clinical trial.

Randomization and Blinding

During their admission for delivery, eligible patients were approached by trained research personnel (D.D.M., B.K., and J.R.) to discuss the trial and informed consent. After completion of cesarean delivery, individuals were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the high-frequency (20 000 Hz) electrical stimulation device or an identical-appearing sham device via the simple urn method.26,27 Individuals in both groups received scheduled nonopioid analgesics and as needed opioid analgesics postoperatively, as is standard care at OSU Wexner Medical Center. The devices were numbered, and randomization assignments (numbers corresponding to functional or sham device) were placed in sealed, numbered opaque envelopes, which were kept in a locked cabinet and only accessible by trained research staff. The next sequential envelope was opened by trained research personnel (D.D.M., B.K., J.R., and K.R.) prior to the first application. Two identical-appearing devices were supplied by the manufacturer, one a functioning high-frequency electrical stimulation device and the other a sham device. The sham device appeared and functioned identically to the active device, including identical power activation, vibration, and sensation, but did not emit any current. This was a triple-blind study, as patients, clinicians, and research personnel were blinded to the patient’s treatment assignment group (functional vs sham device), and the devices were indistinguishable.

Procedures

Application of the functional or sham device occurred a total of 3 times beginning on postoperative day 0. The first application was accomplished as soon as was practical following cesarean delivery and no more than 2 hours after arrival in the recovery area. The second application occurred 12 (acceptable range 10-14) hours after the first application. The third and final application occurred 12 (acceptable range 10-14) hours after the second application. The range for the second and third applications was intended to avoid waking the patient when sleeping or interrupting clinical care. Aside from device application, participants received usual inpatient care postoperatively, including standard scheduled nonopioid medications and as needed opioid pain medications at the discretion of the clinical team.

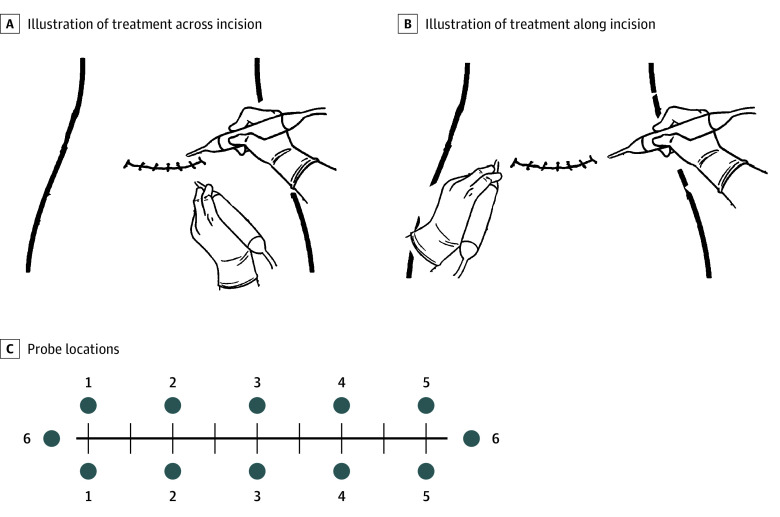

Each application lasted a total of 12 minutes. The probes were placed perpendicular to the skin line approximately 1 inch (to convert to centimeters, multiply by 2.54) from the abdominal skin incision (Figure 1). The probes were initially placed with 1 probe superior to and 1 inferior to the incision, then lifted and moved to a new location every 2 minutes, moving longitudinally along the length of the incision. For the final 2 minutes, one probe was placed at each lateral edge of the incision (Figure 2). All applications were performed by trained clinical research personnel (D.D.M., B.K., J.R., and K.R.).

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

CONSORT indicates Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Figure 2. Procedure for Application of the TrueRelief High-Frequency Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Device.

A, For treatment across the incision, probes were placed on opposite sides of the surgical incision, just beyond the sutures, with an interprobe distance of 0.5 to 1 inch (to convert to centimeters, multiply by 2.54). Treatment was applied for 2 minutes at each probe placement. B, For treatment along the incision, probes were placed on opposite ends of the surgical incision, just beyond the ends of the incision, and treatment was applied for 2 minutes. C, For each treatment, probes were placed at 6 different locations (shown as blue numbered circles), and treatment was applied for 2 minutes at each location. For ease of visualization, illustrations show the probe tips at less than 90 degrees to the treatment area surface. For maximum efficacy during treatments, the probe tips were kept perpendicular to the treatment surface. Illustrations provided by TrueRelief, LLC.

On postoperative day 2, participants completed the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), a pain severity questionnaire. The BPI includes self-assessment of pain scores in the previous 24 hours using a numerical scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing no pain and 10 the worst pain imaginable.28,29 The type and number of opioid pills prescribed at discharge were at the discretion of the discharging physician. It is standard of care at OSU Wexner Medical Center to use an individualized opioid prescription protocol, which includes shared decision-making informed by inpatient morphine milligram equivalent (MME) requirements to determine the number of opioid pills prescribed at discharge.30 Trained, blinded research staff members (D.D.M., B.K., and J.R.) abstracted information from electronic medical records, including demographic information, medical and obstetric history, and outcome data. At 6 weeks postpartum, the electronic health record and the state prescription drug monitoring program, an electronic database that tracks controlled substance prescriptions, were reviewed to obtain the number of additional opioid prescriptions and the results of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), scored on a scale of 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating increased risk and severity of depression, that was completed during the postpartum visit.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the total postoperative opioid intake through hospital discharge. All opioid doses were converted to equianalgesic doses of morphine sulfate MME using standard ratios.31 Secondary outcomes included moderate to severe pain (defined as BPI score >4) within the past 24 hours and mean pain score in the previous 24 hours on postoperative day 2 assessed via the BPI numeric scale from 0 to 10; MME prescribed at discharge; additional opioid prescriptions within 6 weeks postpartum (verified by review of the state prescription drug monitoring program); device-related adverse events; and wound complications. Although we initially planned to assess the number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge, we present the data herein as MME prescribed to allow for a more accurate comparison regardless of strength or formulation of opioid pill, as prescribing patterns varied between health care professionals.

Statistical Analysis

Review of inpatient postoperative data from OSU Wexner Medical Center showed that from postoperative day 0 to 2 after cesarean delivery, individuals consumed a mean (SD) of 42 (15) MME. We calculated that a total sample size of 134 (67 individuals per group) has 90% power to detect at least 20% reduction in the primary outcome with a 2-sided type 1 error of 5%. Recruitment was stopped when the target number of participants was reached.

Analyses were completed following intention-to-treat principles, with participants included in the treatment group to which they were randomly assigned regardless of the completion of the treatment. The statistical analysis plan is available in Supplement 1. Briefly, the data were assessed for normality, and if this assumption was met, a t test was used; if data were not normally distributed despite log transformation, a Mann-Whitney U test was used. A t test was used for normally distributed, continuous, secondary outcomes. For categorical secondary outcomes, a χ2 test was performed. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Means and median differences (MDs) are reported where appropriate. For categorical data, relative risks (RRs) are presented with 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were performed as 2-sided tests with a significance threshold of P < .05 or 95% CI excluding 1. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata, version 2015, release 14 (StataCorp).

Results

From April 18, 2022, to January 31, 2023, 363 individuals were screened for eligibility. Of the 267 eligible people, 134 (50%; mean [SD] age, 30.5 [4.6] years; mean [SD] gestational age at delivery, 38 weeks 6 days [8 days]) were randomly assigned: 67 to the functional device and 67 to the identical-appearing sham device (Table 1 and Figure 2). One patient in the sham device group withdrew consent after randomization before any application was completed. Thirty-four (51%) individuals in both groups were discharged home on postoperative day 2, whereas the other individuals remained as inpatients until postoperative day 3 (30 [45%]) or beyond (3 [4%]). Twenty-six (19%) individuals did not attend their 6-week postpartum visit and thus did not complete an EPDS screen.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population, by Group.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Functional device (n = 67) | Sham device (n = 67) | |

| Demographic and pregnancy characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 30.5 (4.9) | 31.4 (4.8) |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 45 (68) | 44 (66) |

| Government assisted | 21 (31) | 22 (33) |

| Self-pay or uninsured | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Medical history | ||

| Depression or anxiety disorder | 13 (20) | 8 (12) |

| Chronic hypertension | 8 (12) | 7 (10) |

| Pregestational diabetes | 3 (5) | 4 (6) |

| Chronic pain disorder | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Nulliparous | 17 (25) | 12 (18) |

| Twin gestation | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| History of PTB | 11 (16) | 12 (18) |

| History of prior CD | 29 (43) | 39 (58) |

| Prepregnancy BMI>30 | 36 (54) | 37 (55) |

| Delivery characteristics | ||

| Gestational age at delivery, mean (SD) | 38 wk 5 d (7 d) | 39 wk 1 d (10 d) |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks | 11 (16) | 10 (15) |

| HDP | 8 (12) | 6 (9) |

| Type of labor | ||

| No labor | 46 (69) | 43 (64) |

| Spontaneous or augmented | 6 (9) | 3 (5) |

| Induced | 15 (22) | 21 (31) |

| Type of anesthesia | ||

| Spinal | 52 (78) | 56 (83) |

| Epidural | 15 (22) | 11 (17) |

| Type of skin incision | ||

| Low transverse | 66 (99) | 66 (99) |

| Vertical | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Tubal ligation or salpingectomy | 14 (21) | 12 (18) |

| EBL, median (IQR), mL | 500 (350-600) | 500 (327-700) |

| Magnesium sulfate infusion | 6 (9) | 5 (7) |

| Blood transfusion | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Infant characteristics | ||

| Total No. | 69a | 67 |

| NICU admission | 15 (22) | 8 (12) |

| Breastfeeding at hospital discharge | 59 (86) | 57 (85) |

Abbreviations: CD, cesarean delivery; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); EBL, estimated blood loss; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia); NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PTB, preterm birth.

Included 2 sets of twins.

Individuals who were assigned to the functional device used significantly less opioid medication in the postpartum period before hospital discharge compared with individuals who were assigned to the sham device (median [IQR], 19.75 [0-52.50] MME vs 37.50 MME [7.50-67.50]; P = .046; MD, 17.75 MME; Table 2). On postoperative day 2, patients in both groups reported similar rates of moderate to severe pain (BPI score >4) within the past 24 hours (85% vs 91%; RR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.55-1.29]; P = .43). Patients in the sham device group reported a mean pain score of 4.46 (95% CI, 4.01-4.92) using the BPI scale compared with 3.59 (95% CI, 3.21-3.98; P = .004) in the functional device group (MD, 0.87) (Table 2). The difference in pain scores did not reach the minimum clinically important difference of 2 points.32

Table 2. Postoperative Outcomes, by Study Group.

| Outcome | Functional device (n = 67) | Sham device (n = 67) | MD or RR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] or mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Primary | ||||

| Total inpatient oral opioids consumed, MME | 19.75 [0-52.50] | 37.50 [7.50-67.50] | 17.75 | .046 |

| Secondary | ||||

| Moderate to severe pain (BPI score >4) in past 24 h, No. (%)b | 57 (85) | 61 (91) | 0.77 (0.55-1.29) | .43 |

| Mean pain score in past 24 hb | 3.59 (3.21-3.98) | 4.46 (4.01-4.92) | 0.87 | .004 |

| Oral opioid prescribed at discharge, MME | 82.50 (0-90.00) | 90.00 (75.00-90.00) | 7.5 | <.001 |

| Patients with no opioid prescription dispensed at discharge, No. (%) | 17 (25) | 7 (10) | 1.58 (1.08-2.13) | .03 |

| Opioid refill after discharge, No. (%) | 1 (1.5) | 7 (10.4) | 0.24 (0.04-0.92) | .07 |

| LOS, d | 2.58 (2.41-2.76) | 2.69 (2.43-2.94) | −0.10 | .50 |

| Wound separation or infection, No. (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | NA | .05 |

| Positive EPDS score 2-6 wk, No. (%)c | 7 (10) | 4 (6) | 1.32 (0.72-1.97) | .36 |

Abbreviations: BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; LOS, length of hospital stay; MME, morphine milligram equivalents; MD, mean or median difference; NA, not applicable; RR, relative risk.

The t test was used for comparing means of continuous variables; Mann-Whitney U test, for medians of continuous variables; and the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables.

Pain was assessed using the BPI, which includes rating mean pain in the previous 24 hours using a numerical scale from 0-10, with 0 representing no pain and 10 the worst pain imaginable.

EPDS, scored on a scale of 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating increased risk and severity of depression. A positive score was defined as greater than or equal to 12.

At discharge, individuals assigned to the functional device were prescribed significantly fewer oral opioids (median [IQR], 82.50 [0-90.00] MME) compared with the sham device group (median [IQR], 90.00 [75.00-90.00] MME; P < .001), with a median difference of 7.5 MME and were more likely to be discharged without an opioid prescription (25% vs 10%; RR, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.08-2.13]; P = .03). There were no significant differences between the groups in length of hospital stay, rate of wound infection or separation, or rate of positive EPDS scores (≥ 12) at 6 weeks postpartum. No treatment-related adverse effects occurred in either group, and all participants who received treatments completed all 3 treatments with the device or sham device.

Discussion

In this triple-blind randomized clinical trial, participants who received transcutaneous treatment with a high-frequency electrical stimulation device after cesarean delivery used approximately 47% fewer opioid analgesics in the hospital and had pain scores similar to those who were assigned to a sham device. Participants who received treatment with the functional device were also prescribed fewer MME at discharge.

Transcutaneous electrical stimulation devices have shown promise as adjuncts for postoperative pain control in other settings, but most previously studied devices emit current at much lower frequencies than the device used in our study.20,33 A study by Elboim-Gabyzon et al22demonstrated lower pain scores and improved mobility among patients treated with a 100-Hz TENS device after surgical fixation of hip fractures. After coronary artery bypass surgery, patients who received TENS treatment at 100 Hz had lower pain scores, lower opioid requirements, and improved pulmonary function in the first 72 hours after surgery.34 In addition to lower opioid analgesic requirements and similar pain scores, TENS treatment has few adverse effects and may be associated with improved postoperative mobility, decreased nausea and vomiting, and improved pulmonary function.20,35

Despite evidence for benefit after other common surgical procedures, evidence for the use of electrical stimulation devices after cesarean delivery is lacking. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation devices were first used in the 1970s, and several studies on their use after cesarean delivery were published in the 1980s with mixed results.36,37 In retrospective studies, Smith et al36 and Hollinger37 demonstrated lower pain scores among patients treated with TENS devices at frequencies of 85 and 100 Hz, respectively. In a randomized trial of 35 patients,38 Davies found lower pain scores and analgesic use among patients who received general anesthesia and active TENS treatment at 25 Hz compared with placebo, but no benefit in the group of patients who received epidural anesthesia. Interpretation of these studies is limited by their small sample size, lack of randomization or blinding, and changes in anesthetic care for cesarean delivery since their publication.

In the decades since the 1980s, few studies have been published on TENS use after cesarean delivery. Kayman-Kose et al39 performed a randomized clinical trial in Turkey of treatment with a TENS device or sham device after cesarean delivery. The TENS group had lower pain scores and lower analgesic requirements postoperatively, but the study included only patients who received general anesthesia, limiting its applicability in the US where the majority of cesarean deliveries are performed using neuraxial anesthesia. A Cochrane review published in 202040 on complementary and alternative therapies for postcesarean pain management rated the quality of evidence regarding the use of TENS after cesarean delivery as very low and identified only 2 published articles including a total of 92 participants that were of sufficient quality for inclusion in the review.40

Since publication of the Cochrane review, Kurata et al41 performed a randomized placebo-controlled trial of a TENS device for postcesarean pain but found no differences in analgesic use or pain scores between the groups. We believe that the differences in the results of that study and our study may be attributable to key method and technology differences. Notably, the device used in the study by Kurata et al41 administered current at a frequency several orders of magnitude lower than the device used in the present study (120 vs 20 000 Hz) and required placement of adhesive electrode pads. Previous studies have demonstrated improved efficacy with higher frequency TENS devices compared with lower frequencies.42 In the active treatment group in the study by Kurata et al,41 each participant self-titrated device amplitude to their comfort level and could turn off the TENS device whenever they desired. Participants in the placebo group were connected to a TENS device that did not have any power source and thus was easily distinguished from the active device by study staff and participants. In our study, we used a high-frequency device administered by trained research staff at a uniform amplitude. Unlike lower frequency devices, current at a frequency of 20 000 Hz, as used in this study, cannot typically be felt except as vibration. We used an identical sham device with power that vibrated at the same frequency as the active device to maintain blinding.

Our study demonstrates the efficacy of treatment with a high-frequency electrical stimulation device for postcesarean pain in a contemporary US population receiving multimodal analgesia in accordance with current guidelines.3,14,15,18 The use of a high-frequency electrical stimulation device may offer a safe, noninvasive strategy to reduce postcesarean opioid use and thus avoid the dangers of opioid adverse effects, overprescribing, diversion, and development of dependence. With 1.2 million cesarean deliveries annually and the development of chronic opioid dependence following surgery estimated at 3% to 6%, approximately 36 000 to 72 000 individuals in the US each year develop dependence after cesarean delivery.1,2,4,5 Effective methods of opioid use reduction thus remain a public health priority.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study include the use of an identical sham device to administer treatments, thus ensuring blinding of participants, health care professionals, and research staff to the group assignment until study completion. The treatment groups were well matched with regard to demographic and obstetric characteristics. Treatments were administered by trained research staff in a uniform fashion, and all participants except 1 received all planned treatments. We integrated treatments into the usual postoperative care regimen and did not change any other aspect of postoperative analgesic care.

Limitations of our study include that actual opioid use in the sham device group was lower than the baseline estimate we used in our sample size calculation. This lower use likely reflects a general focus on decreasing opioid use at OSU Wexner Medical Center as well as nationally.43 Nevertheless, our study showed a 53% decrease in inpatient postoperative MME use in the active device group. The opioids prescribed at discharge differed by a median of 7.5 MME, which equates to approximately 1 fewer 5-mg oxycodone tablet per individual treated with the functional device. If applied nationally, this would represent 1.2 million fewer opioid tablets dispensed annually and available for diversion, mishandling, or development of dependence. Additionally, 25% of participants in the functional device group, compared with only 10% in the sham device group, were prescribed no opioid pills at discharge. While it will be helpful to include assessments of actual opioid use after discharge (ie, pill counts) in future studies, this finding demonstrates sustained benefits in opioid use reduction beyond the period of active treatment, with similar pain scores. Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of the intervention will be important in future studies, considering both direct and indirect costs of opioid use and dependence, which have been estimated to exceed $8 billion annually in the Medicaid system alone.44

Generalizability is limited by the inclusion of English-speaking participants only, and testing the intervention in more diverse populations will be important in future studies. Our study included only 2 patients who underwent cesarean delivery via a vertical midline skin incision; thus, our ability to evaluate efficacy of the device with vertical midline incisions, as opposed to low transverse skin incisions, was limited. In this study, device applications, which were labor intensive and dependent on staff availability, were performed by trained research staff.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical trial of postoperative patients following cesarean delivery, the use of a high-frequency electrical stimulation device as part of a multimodal analgesic protocol decreased inpatient opioid use by approximately 47%, with similar pain scores, and was associated with fewer MME prescribed at discharge compared with a sham device. Future studies focused on integrating device use into routine care and in other settings are needed to confirm the feasibility and generalizability of these findings.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Dinis J, Soto E, Pedroza C, Chauhan SP, Blackwell S, Sibai B. Nonopioid versus opioid analgesia after hospital discharge following cesarean delivery: a randomized equivalence trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(5):488.e1-488.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of operating room procedures during inpatient stays in U.S. hospitals, 2018. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb281-Operating-Room-Procedures-During-Hospitalization-2018.jsp [PubMed]

- 3.Carvalho B, Butwick AJ. Postcesarean delivery analgesia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017;31(1):69-79. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, Zuckerwise LC, Young JL, Richardson MG. Postdischarge Opioid Use After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):36-41. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, et al. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):29-35. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Vital Statistics System, Natality on CDC WONDER Online Database: about natality records 2016-2021. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://wonder.cdc.gov/natality-expanded-current.html

- 8.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies–tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063-2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241-248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peahl AF, Dalton VK, Montgomery JR, Lai YL, Hu HM, Waljee JF. Rates of new persistent opioid use after vaginal or cesarean birth among US women. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197863. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt P, Berger MB, Day L, Swenson CW. Home opioid use following cesarean delivery: How many opioid tablets should obstetricians prescribe? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(4):723-729. doi: 10.1111/jog.13579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemmill A, Kiang MV, Alexander MJ. Trends in pregnancy-associated mortality involving opioids in the United States, 2007-2016. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):115-116. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL. Postoperative multimodal analgesia pain management with nonopioid analgesics and techniques: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):691-697. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson RD, Caughey AB, Wood SL, et al. Guidelines for antenatal and preoperative care in cesarean delivery: enhanced recovery after surgery society recommendations (part 1). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(6):523.e1-523.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corso E, Hind D, Beever D, et al. Enhanced recovery after elective caesarean: a rapid review of clinical protocols, and an umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1265-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyon A, Solomon MJ, Harrison JD. A qualitative study assessing the barriers to implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery. World J Surg. 2014;38(6):1374-1380. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2441-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bollag L, Lim G, Sultan P, et al. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology: consensus statement and recommendations for enhanced recovery after cesarean. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(5):1362-1377. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton CD, Carvalho B. Optimal Pain Management after cesarean delivery. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35(1):107-124. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson MI. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) as an adjunct for pain management in perioperative settings: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(10):1013-1027. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1364158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro Nuñez C, Pacheco Carrasco M. Transcutaneous electric stimulation (TENS) to reduce pain after cesarean section. Article in Spanish. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2000;68:60-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elboim-Gabyzon M, Andrawus Najjar S, Shtarker H. Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on acute postoperative pain intensity and mobility after hip fracture: A double-blinded, randomized trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1841-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilfeld BM, Plunkett A, Vijjeswarapu AM, et al. ; PAINfRE Investigators . Percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation (neuromodulation) for postoperative pain: a randomized, sham-controlled pilot study. Anesthesiology. 2021;135(1):95-110. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H, Datta-Chaudhuri T, George SJ, et al. High-frequency electrical stimulation attenuates neuronal release of inflammatory mediators and ameliorates neuropathic pain. Bioelectron Med. 2022;8(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s42234-022-00098-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) Premarket notification for K202186. 2021. Accessed September 17, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K202186

- 26.Carroll D, Tramèr M, McQuay H, Nye B, Moore A. Randomization is important in studies with pain outcomes: systematic review of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in acute postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77(6):798-803. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.6.798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberger WF. Randomization in Clinical Trials. Wiley; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poquet N, Lin C. The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). J Physiother. 2016;62(1):52. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150(6):782-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prescription after cesarean trial . ClinicalTrials Identifier: NCT04296396. Updated March 24, 2023. Accessed August 1, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04296396

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/providers/prescribing/pdf/calculating-total-daily-dose.pdf

- 32.Mathias SD, Crosby RD, Qian Y, Jiang Q, Dansey R, Chung K. Estimating minimally important differences for the worst pain rating of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(2):72-78. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Ljunggreen AE. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can reduce postoperative analgesic consumption: a meta-analysis with assessment of optimal treatment parameters for postoperative pain. Eur J Pain. 2003;7(2):181-188. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jahangirifard A, Razavi M, Ahmadi ZH, Forozeshfard M. Effect of TENS on postoperative pain and pulmonary function in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Pain Manag Nurs. 2018;19(4):408-414. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson MI, Paley CA, Howe TE, Sluka KA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for acute pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(6):CD006142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith CM, Guralnick MS, Gelfand MM, Jeans ME. The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on post-cesarean pain. Pain. 1986;27(2):181-193. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90209-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollinger JL. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation after cesarean birth. Phys Ther. 1986;66(1):36-38. doi: 10.1093/ptj/66.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies JR. Ineffective transcutaneous nerve stimulation following epidural anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1982;37(4):453-454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1982.tb01159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kayman-Kose S, Arioz DT, Toktas H, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain control after vaginal delivery and cesarean section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(15):1572-1575. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.870549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zimpel SA, Torloni MR, Porfírio GJM, et al. Complementary and alternative therapies for post-caesarean pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurata NB, Ghatnekar RJ, Mercer E, Chin JM, Kaneshiro B, Yamasato KS. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for post-cesarean birth pain control: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(2):174-180. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima LEA, Lima ASdO, Rocha CM, et al. High and low frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in post-cesarean pain intensity. Fisioterapia e Pesquisa. 2014;21(3):243-248. doi: 10.590/1809-2950/65021032014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badreldin N, Ditosto JD, Holder K, Beestrum M, Yee LM. Interventions to reduce inpatient and discharge opioid prescribing for postpartum patients: a systematic review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2023;68(2):187-204. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leslie DL, Ba DM, Agbese E, Xing X, Liu G. The economic burden of the opioid epidemic on states: the case of Medicaid. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(13)(suppl):S243-S249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement