Abstract

The ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants emphasizes the need for vaccines providing broad cross-protective immunity. This study was undertaken to assess the ability of Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted monovalent recombinant spike protein (Wuhan, Beta, Gamma) vaccines or a trivalent formulation to protect hamsters against Beta or Delta virus infection. The ability of vaccines to block virus transmission to naïve co-housed animals was also assessed. In naïve hosts, the Beta variant induced higher virus loads than the Delta variant, and conversely the Delta variant caused more severe disease and was more likely to be associated with virus transmission. The trivalent vaccine formulation provided the best protection against both Beta and Delta infection and also completely prevented virus transmission. The next best performing vaccine was the original monovalent Wuhan-based vaccine. Notably, hamsters that received the monovalent Gamma spike vaccine had the highest viral loads and clinical disease of all the vaccine groups, a potential signal of antibody disease-enhancement (ADE). These hamsters were also the most likely to transmit Delta virus to naïve recipients. In murine studies, the Gamma spike vaccine induced the highest total spike protein to RBD IgG ratio and the lowest levels of neutralizing antibody, a context that could predispose to ADE. Overall, the study results confirmed that the current SpikoGen® vaccine based on Wuhan spike protein was still able to protect against clinical disease caused by either the Beta or Delta virus variants but suggested additional protection may be obtained by combining it with extra variant spike proteins to make a multivalent formulation. This study highlights the complexity of optimizing vaccine protection against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants and stresses the need to continue to pursue new and improved COVID-19 vaccines able to provide robust, long-lasting, and broadly cross-protective immunity against constantly evolving SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-Cov-2, Vaccine, Adjuvant, Advax, Pandemic, Coronavirus

INTRODUCTION:

COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus infection represents an ongoing global public health challenge. While vaccines have had positive impact in reducing disease severity, they have met with less success in preventing infection and transmission, particularly by newer immune-escape variants such as Beta, Delta and Omicron strains [1]. This raises the question of how to modify current vaccines to improve their ability to protect against new variants [2]. Another key challenge is the need for vaccines able to block virus transmission. Yet another important question is whether immunity induced by one spike protein might negatively impact disease caused by another virus variant, through processes such as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).

Subunit recombinant protein vaccines have great utility but depend upon adjuvants to improve their immunogenicity [3, 4]. Advax-CpG is a proprietary adjuvant formulation which combines plant-derived delta inulin with a CpG oligonucleotide toll-like receptor (TLR)-9 agonist [5, 6]. Advax-CpG adjuvant enhances B and T cell responses to co-administered antigens and thereby enhances vaccine protection as confirmed in a wide range of disease models [7–10]. Notably, Advax-CpG adjuvant enhanced protection of vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease [11] and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease [12]. SpikoGen® is a recombinant spike protein (rSp) vaccine against COVID-19 that contains Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvant and received a marketing authorization in the Middle East on October 6th, 2021. This approval followed a series of clinical trials that confirmed its ability to reduce symptomatic infection and provide 77.5% efficacy in protecting against severe disease caused by the Delta variant [13–16]. SpikoGen® is based on a rSp extracellular domain (ECD) from the original Wuhan strain formulated with Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvant and was shown to protect against challenge with ancestral Wuhan-Hu-1 like virus strains in ferret [17], hamster [18] and non-human primate [19] studies.

The rapid evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus with emergence of highly transmissible immune-escape variants, means that vaccines based on the original ancestral spike sequence could lose their protective efficacy against such virus variants. There is also the unanswered question of whether loss of serum neutralizing antibody against a new variant in the presence of non-neutralizing anti-spike antibody could lead to ADE, a phenomenon reported with other viral infections.

There is also the question of how best to modify existing vaccines like SpikoGen®, based on the original ancestral spike protein sequence, to maximize their ability to protect against new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Such approaches might include development of monovalent vaccines based on a more recent spike protein variant for use as a heterologous booster, or the addition of newer spike protein variants to the current vaccine based on the ancestral spike protein to create a multivalent vaccine.

In the current studies, we compared the protection provided by Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted monovalent Wuhan, Beta or Gamma spike protein vaccines as compared to a trivalent vaccine containing all three spike proteins. As shown by the study results, initial vaccine immunogenicity studies in mice confirmed the trivalent vaccine prototype provided broad neutralizing immunity against all the vaccine strains plus the Delta variant, closely followed by the original monovalent Wuhan-spike vaccine. At the other extreme, the monovalent Gamma spike protein vaccine provided only weak immunogenicity, with very low neutralizing activity even against a homologous Gamma spike pseudotype virus. Next, the same vaccine prototypes were used to immunize hamsters which were then challenged with either Beta or Delta virus variants. In addition to assessment of vaccine effects on direct infection in challenged animals, the study was designed to assess effects of the vaccine on disease transmission to co-housed vaccine-naïve animals. Overall, all vaccine prototypes protected against viral load and disease severity caused by the Beta virus variant and with the exception of the monovalent Gamma spike vaccine, against viral load and disease severity caused by the heterologous Delta virus variant. This was associated with reduced disease transmission from infected immunized animals to naïve recipients, particularly in those animals that received the trivalent vaccine.

METHODS:

Vaccines and Adjuvant

SpikoGen® vaccine is a recombinant spike protein (Sp) based on an extracellular domain (ECD) construct with modifications to stabilize the protein in a prefusion conformation and with addition of a C-terminal polyhistidine sequence to assist in purification. The rSp was produced in insect cells, as previously described [20]. In this study, the Wuhan, Beta and Gamma rSp comprised lab-grade spike protein ECD antigens expressed in insect cells, in a similar manner to the licensed SpikoGen® vaccine. The sequences used corresponded to amino acids 14 – 1213 of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Wuhan, accession number: NC045512), Beta (B.1.351, GenBank: QWA59538, amino acids 14 – 1210), Gamma (P.1, GenBank: URA61182.1, amino acids 12 – 1213) with the furin cleavage site removed and with a histidine tag to assist in purification. Vaccine antigens and Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvant were provided by Vaxine Pty Ltd, Adelaide, Australia.

Mouse Immunization Protocol

Murine immunogenicity studies were carried out at Flinders University, Australia as approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Flinders University (Project No. BIOMED5114) conducted in accordance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes (2013). Female C57BL/6 (n=5 per group), 8 to 10 weeks old, were immunized intramuscularly (IM) with 2 μg spike protein (Wuhan, Beta or Gamma) or a trivalent combination of all three spike proteins formulated with Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvant (1 mg-10 μg) in the thigh muscle at weeks 0 and 2. Blood samples were collected by cheek vein bleeding 2 weeks after the 2nd immunization. Serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at −20°C prior to use.

Antigen-specific ELISA

Anti-rSp and anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG was determined by ELISA, as previously described [20]. Wuhan, Beta, Gamma, Delta, BA.2 and XBB.1 rSp used in ELISAs were lab-grade recombinant spike ECD proteins supplied by Vaxine. Wuhan RBD protein comprising amino acids Arg 319 - Lys 537 of spike protein with a polyhistidine tag at the C-terminus was expressed in HEK293 cells, as previously described [21]. Beta, Gamma, Delta, BA.2 and XBB.1 RBD proteins were purchased from ACROBiosystems (Newark, Delaware, USA). Briefly, 0.5 μg/ml rSp or RBD in PBS were used to coat 96-well ELISA plates (100 μl/well). After blocking, 100 μl of diluted serum samples were added for 2 h. After washing, biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated Streptavidin (BD Biosciences) for 1 h. After washing, 100 μl of TMB substrate (KPL, SeraCare, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was added and incubated for 10 min before the reaction was stopped with 100 μl 1M phosphoric acid (Sigma-Aldrich). The optical density was measured at 450 nm (OD450 nm) using a VersaMax plate reader and analyzed using SoftMax Pro Software. Average OD450 nm values obtained from negative control wells were subtracted.

SARS-CoV-2 Pseudotype Neutralization (pVNT) Assay

A replication-deficient SARS-CoV-2 pseudotype neutralization titer (pVNT) assay was used to evaluate neutralizing activity of murine sera, as previously described [20]. Briefly, neutralization activity of immune sera was measured with a single round transduction of 293T-hACE2 cells with spike-pseudotyped lentiviral (PsV) particles expressing Wuhan, Beta, Gamma or Delta spike protein. Prior to infecting cells, immune sera were serially diluted and incubated with PsV particle for 1 h at 37°C in a 96-well white tissue culture plate. Then 50 μl of 293T-hACE2 cells were added at 12,500 cells per well. The plates were then cultured at 37°C for 48 h, followed by removal of the culture medium and replacement with 30 μl of Phenol red-free DMEM medium. Then 30 μl of ONE-Glo EX (Promega) reagent was added into each well and the plates incubated at RT for 5 min with shaking at 450 rpm on a ThermoMixer (Eppendorf) before luciferase activity reading on BMG FluoStar plate reader. Neutralization was calculated by reduction in % luciferase units relative to PsV alone group without any serum treatment. Titers providing 50% neutralization of virus were then calculated using Sigmoidal 4PL robust fit regression method in GraphPad Prism Ver. 9.

Hamster Immunization Protocol

All hamsters were held at Colorado State University (CSU) in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International-accredited animal facilities. Animal testing and research received ethical approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (animal protocol #1559). Golden Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) at 6 weeks of age were acquired from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). Hamsters were maintained in a Biosafety Level-2 (BSL-2) animal facility at the Regional Biocontainment Laboratory at CSU during the vaccination period. The hamsters were group-housed and fed a commercial diet with access to water ad libitum. Each hamster was ear notched for animal identification. Hamsters (5 groups of n = 6) were vaccinated IM twice 4 weeks apart. Hamsters were transferred to a BSL-3 animal facility at the Regional Biocontainment Laboratory at CSU prior to live virus challenge. The challenge viruses were obtained from BEI Resources and were B.1.351 (Beta), SARS-CoV-2 hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP01542/2021, BEI NR-55282 and B.1.617.2 (Delta), SARS-CoV-2 hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021, BEI NR-55672. Two weeks after the second vaccine dose each group of 6 animals were split in half, with half (n = 3) challenged with Beta (B.1.351) variant and the other half challenged with the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant. Two days post-challenge each challenged hamster was moved singly to a cage containing a single vaccine-naïve recipient hamster to assess the ability of the vaccine to protect against transmission. The following day (D3 post-challenge) the challenged hamsters were removed from the cages housing recipients and were euthanized and their tissues collected to define viral loads in nasal turbinate and lung and to perform lung histology. After being co-housed for a day with a virus challenged animal, naïve recipient animals were assessed daily for a further 4 days with oropharyngeal viral swabs and then sacrificed (four days post-exposure exposure to inoculated hamsters) to define lung and nasal turbinate viral load to see whether they had become infected.

For the challenges, the hamsters were first lightly anesthetized with a 10:1 mixture of ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine hydrochloride. Each hamster was administered 104 plaque-forming units (pfu) of the relevant virus strain via pipette into the nares (50 μl/nare) for a total volume of 100 μl per hamster. Virus back-titration was performed on Vero cells immediately following inoculation. Hamsters were observed until fully recovered from anesthesia. Oropharyngeal swabs were taken on days 1–3 after challenge (or days 1–4 after co-housing for recipients) to evaluate viral shedding. Swabs were placed in BA-1 medium (Tris-buffered MEM containing 1% BSA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics, then stored at −80 °C until further analysis. Tissues were collected for virus quantification and histopathology. For virus quantitation, approximately 100mg of the right cranial lung lobe and nasal turbinates from each hamster were homogenized in 9 volumes of BA-1/FBS media with antibiotics then frozen to −80 °C for later analysis. The tissue homogenates were briefly centrifuged and virus titers in the clarified fluid was determined by plaque assay. Viral titers of tissue homogenates are expressed as log10 pfu/100 mg. For histopathology, portions of the left and the right medial lung lobes were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for seven days then paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using routine methods for histological examination.

Virus Titration

Plaque assays were used to quantify infectious virus in oropharyngeal swabs and tissue homogenates, as previously described [18]. Briefly, 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared in BA-1 media supplemented with antibiotics. Confluent Vero cell monolayers were grown in 6-well tissue culture plates. The growth media was removed from the cell monolayers and each well was inoculated with 0.1 ml of the appropriate diluted sample. The plates were rocked every 10–15 min for 45 min and then overlaid with 0.5% agarose in MEM/5% FBS without phenol red and incubated for 1 day at 37°C, 5% CO2. A second overlay with neutral red dye was added at 24–30 h and plaques were counted at 48–72 h post-plating. Viral titers are reported as the log10 pfu per swab or gram (g) tissue. Samples were considered negative for infectious virus if viral titers were below the limit of detection (LOD). The theoretical limit of detection was calculated using the following equation:

Where N is the number of replicates per sample at the lowest dilution tested; V is the volume used for viral enumeration (volume inoculated/well in ml). For oropharyngeal swabs the LOD was 10 pfu/swab and for tissues the LOD was 10 pfu/100 mg.

Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT50)

Neutralizing antibody levels were determined by 50% PRNT (PNRT50). Briefly, sera were first heat-inactivated for 30 min at 56 °C in a water bath, then a series of two-fold dilutions in BA-1 media prepared in a 96-well plate starting at a 1:5 dilution. According to the challenge group, an equal volume of the corresponding SARS-CoV-2 virus to the challenge strain (hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP01542/2021 or hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021) was added to the serum dilutions and the sample-virus mixture was gently mixed. The plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, serum-virus mixtures were plated onto Vero plates as described for virus plaque assays. Antibody titers were recorded as the reciprocal of the highest dilution in which >50% of virus was neutralized. All hamsters were tested for the absence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies prior to vaccination.

Histopathology

Histopathology was blindly interpreted by a veterinary pathologist (HBO). H&E-stained lung tissue sections were examined and microphotographed using a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi1 microscope and NIS-Elements F4.60.00 software. The H&E-stained slides were assessed for morphological evidence of inflammatory-mediated pathology in lung and trachea and reduction or absence of pathological features used as an indicator of vaccine-associated protection. Each hamster was assigned a score of 0–5 based on absent, mild, moderate, or severe manifestation, respectively, for each manifestation of pulmonary pathology including overall lesion extent, bronchitis, alveolitis, pneumocyte hyperplasia and vasculitis and then the sum of all scores for each hamster calculated, as previously described [18].

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.3.1 for Windows was used for drawing graphs and statistical analysis (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). PRNT50 titers are presented as geometric mean (GM), the minimum dilution tested for neutralizing antibody was 1:10, and a titer of 5 was used for a negative result to assist statistical analysis. Statistical analyses comparing PRNT50, weight loss, viral load titers and total lung score between groups were performed by one-way ANOVA. For all comparisons, p<0.05 was considered to represent a significant difference. In figures, * = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001 and ****, p < 0.0001.

RESULTS:

Ability of monovalent and trivalent vaccines to induce antibody responses in mice

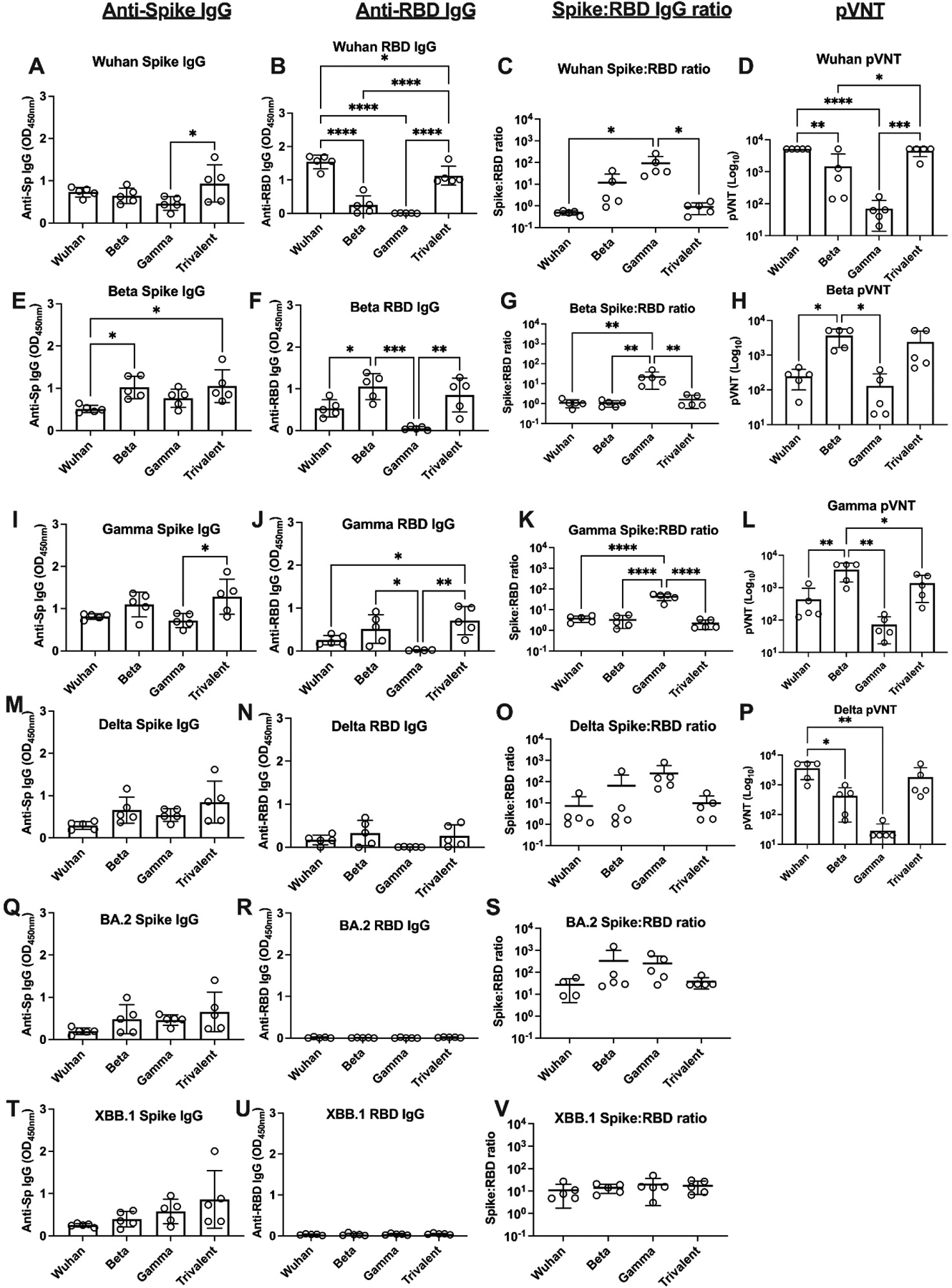

Mice were immunized IM twice at 2-week intervals with Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted monovalent Wuhan, Beta or Gamma or trivalent vaccine containing all three spike proteins. Sera were collected 2 weeks after the 2nd immunization for assessment of whole rSp and RBD-binding IgG against Wuhan, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Omicron BA.2 and XBB.1 variants and for neutralizing antibody by pVNT assay against Wuhan, Beta, Gamma and Delta variants (Figure 1). The Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted trivalent vaccine consistently induced the highest serum rSp IgG levels against all tested variants, including the Delta, Omicron BA.2 and XBB.1 heterologous non-vaccine strains (Fig. 1, 1st column). Interestingly, the monovalent Wuhan vaccine consistently induced amongst the lowest serum rSp IgG levels against all tested variants, although in most cases this difference did not reach the level of statistical significance.

Figure 1: Vaccine immunogenicity in mice.

Mice (n = 5 per group) were immunized IM twice 2 weeks apart with monovalent or trivalent vaccines, as indicated. Sera were collected 2 weeks after the second immunization for immunogenicity assessment. First column shows ELISA results for full spike protein binding IgG for Wuhan, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Omicron BA.2 and XBB.1 variants (mean ± SD). Second column shows ELISA results for RBD binding IgG. Third column shows calculated OD ratio of total spike IgG to RBD binding IgG. Fourth column shows spike protein pseudotyped virus neutralization titers (pVNT) (GMT ± SD). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*; p < 0.05, **; p < 0.01, ***; p < 0.001 and ****; p < 0.0001).

A very different pattern of responses was seen when just RBD binding IgG was assessed, with only Wuhan and trivalent vaccines inducing high levels of IgG against RBDWuhan and only Beta and trivalent vaccines inducing high levels of IgG against RBDBeta and RBDGamma and none of the vaccines inducing significant amounts of IgG against RBDBA.2 and RBDXBB.1 (Fig. 1, 2nd column). Most notably, despite inducing similar levels of anti-rSp IgG against the variants as the other vaccines, the Gamma vaccine failed to induce IgG against the homologous RBDGamma or any other RBD variant.

As anti-RBD IgG mediates ACE2-binding inhibition and thereby correlates with virus neutralization, we next calculated the ratios of whole spike to RBD binding IgG induced by each vaccine against each variant as a measure of the quality of the neutralizing antibody response (Fig. 1, 3rd column). Notably, the Gamma vaccine consistently induced with the highest ratios of whole spike:RBD binding IgG against Gamma and all other variants. Overall, the monovalent Wuhan and the trivalent vaccine were associated with the lowest ratios of whole spike:RBD binding IgG against each of the variants.

Lastly, serum levels of neutralizing antibody against the key variants were assessed using a pVNT assay (Fig. 1, 4th column). Overall, there was a high concordance between the RBD-binding IgG responses and the pattern of pVNT responses against specific variants. The Wuhan and trivalent vaccines gave the highest pVNT responses against the Wuhan and Delta variants, and the Beta and trivalent vaccines gave the highest pVNT responses against the Beta and Gamma variants. Consistent with the low RBD IgG levels, the Gamma vaccine induced negligible levels of serum neutralizing antibody against all variants on the pVNT assays.

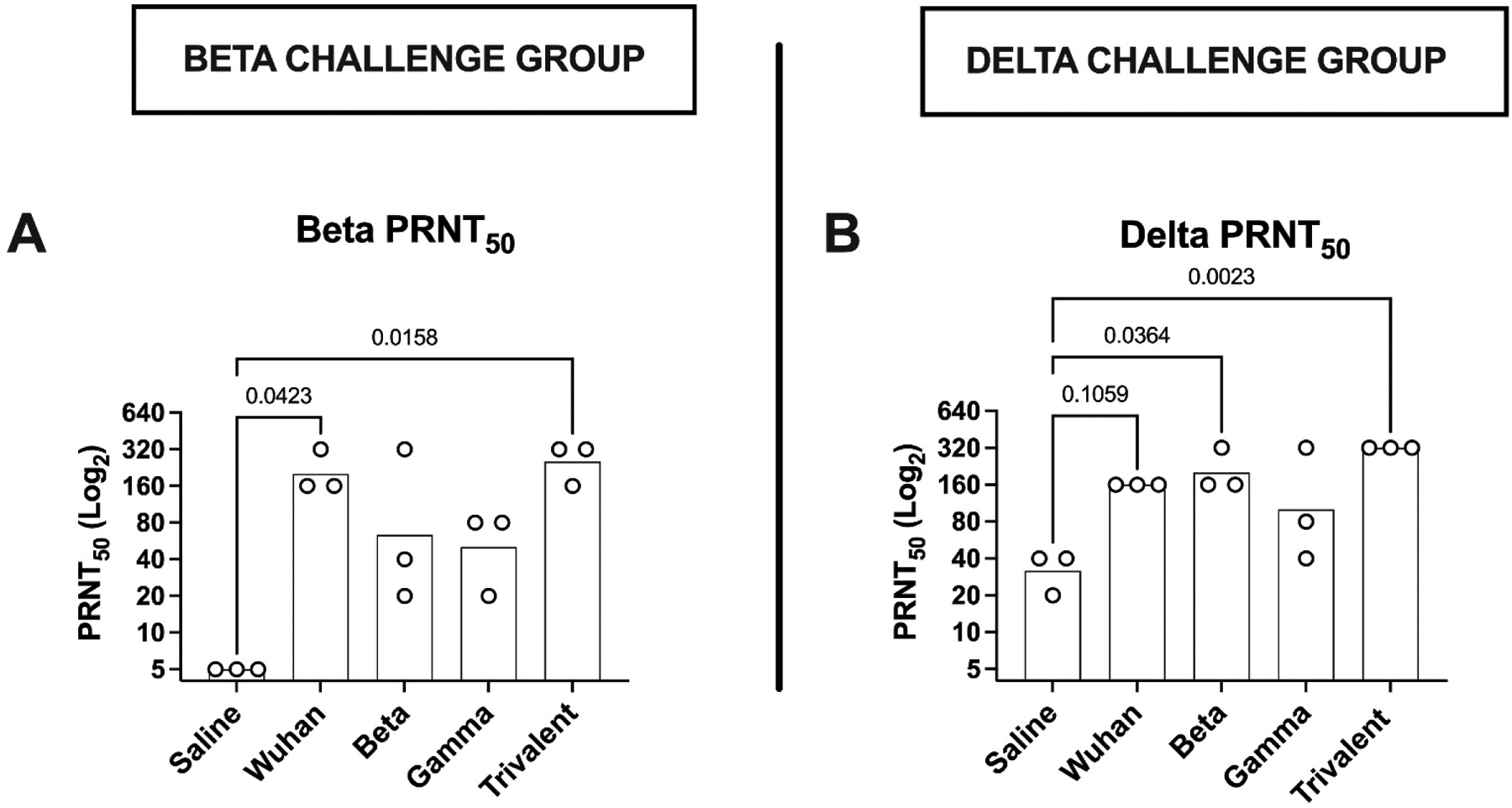

Vaccine immunogenicity in hamsters

As hamsters are more susceptible than wildtype mice to SARS-CoV-2 infection, we next sought to directly compare the efficacy of the monovalent and trivalent vaccines against two different SARS-CoV-2 variants using the hamster challenge model. Hamsters were immunized IM twice at a 4-week interval with Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted Wuhan, Beta or Gamma or trivalent vaccine. The total rSp dose in all cases was kept constant at 3 μg/animal such that the trivalent vaccine contained one third the dose of each specific rSp variant as contained in each monovalent vaccine. Serum neutralizing antibody levels prior to virus challenge were measured by PRNT50 assay against the respective wildtype Beta or Delta viruses used for the challenges.

In the Beta virus challenge group, all immunized animals had detectable Beta PRNT50 levels two weeks after the second vaccine dose, with the trivalent vaccine and the Wuhan vaccine generating the highest, and the Gamma vaccine the lowest, Beta PRNT50 levels (Fig. 2A). For the Delta virus challenge group, the trivalent vaccine generated the highest Delta PRNT50 levels and the Gamma vaccine, the lowest (Fig. 2B). The overall pattern of antibody responses induced by the monovalent and trivalent vaccines in the hamsters mimicked the patterns previously observed in the murine immunogenicity studies.

Figure 2: Vaccine immunogenicity and protection in hamsters.

Hamsters (n = 6 per group) were immunized IM twice at 2-week intervals with monovalent or trivalent vaccine, as indicated. Pre-challenge blood samples were collected 2 weeks after the second immunization for measurement of neutralizing antibody levels by PRNT50 assay. (GMT ± SD) Hamsters allocated to the Beta virus challenge (n=3/group) were assayed for Beta virus PRNT50 (A) and those allocated to the Delta virus challenge group for Delta PRNT50 (B). Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

Hamster Beta and Delta virus challenge model

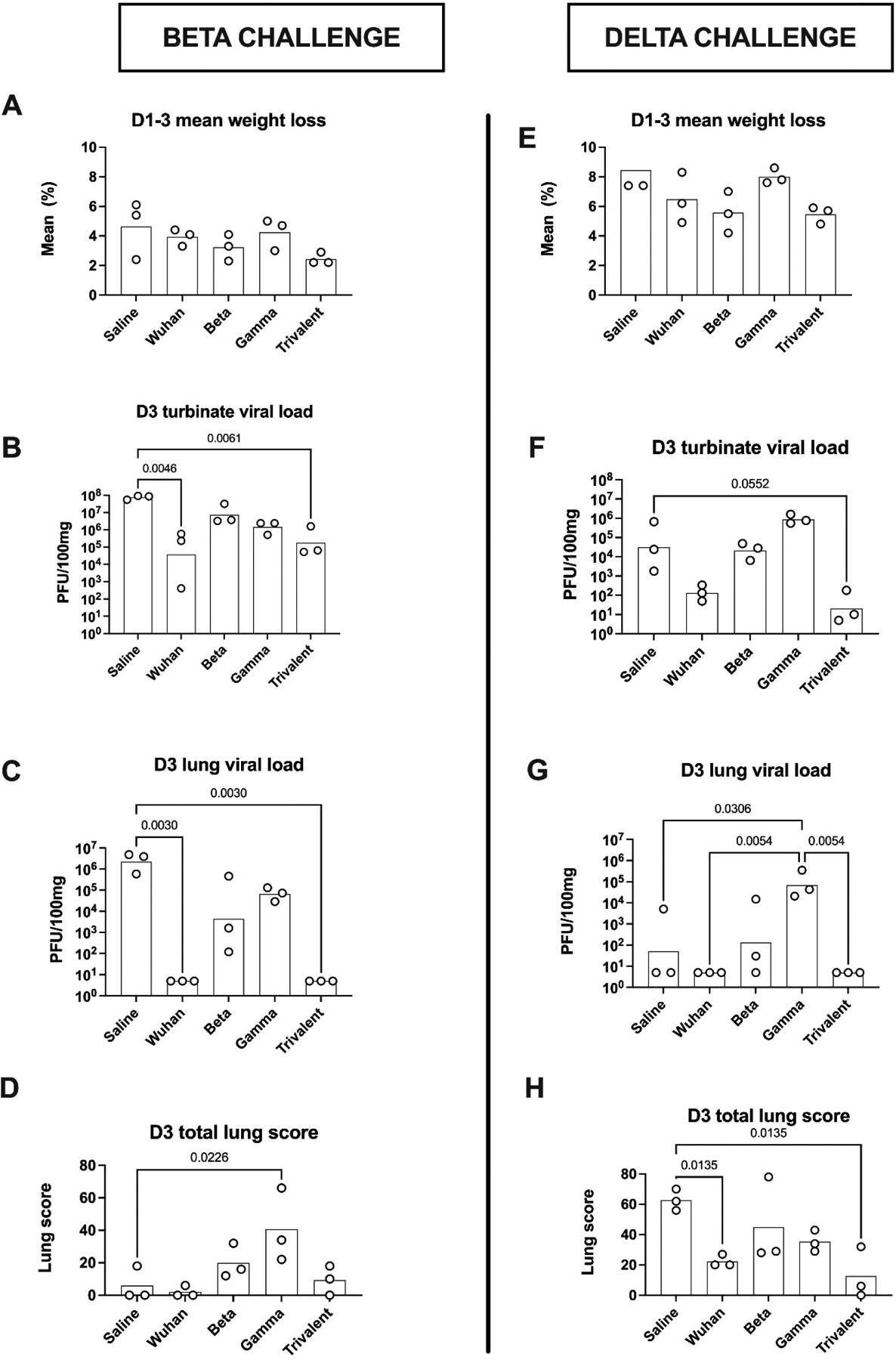

To compare the breadth of COVID-19 protection afforded by the monovalent or trivalent vaccines, hamster models of Beta and Delta virus infection were developed at CSU. Infected control hamsters showed differences in clinical disease in response to infections caused by either Beta or Delta variants. In the naïve control (saline-injected) hamsters the Delta virus caused more severe clinical disease than the Beta virus, with almost twice the mean weight loss when compared to the Beta infected control animals (Fig. 3A & E, 1st bar). Conversely, the Beta virus induced higher virus loads than the Delta virus in D3 nasal turbinate (Fig. 3B & F, 1st bar), D3 lung (Fig. 3C & G, 1st bar) and D1–3 oropharyngeal swabs (Fig. 4, 1st bar). D3 total lung scores were over 6-fold higher in Delta versus Beta infected control animals (Fig. 3D & H, 1st bar), further supporting the impression that the Delta virus induced more severe disease in the hamster model. Hence, in naïve control hamsters the variant associated with the highest viral loads (Beta) was not the one that caused the most severe clinical disease (Delta).

Figure 3. Assessment of clinical disease.

Two weeks after the second immunization hamsters were challenged intranasally with either Beta variant (left column) or Delta variant (right column). Shown are D1-D3 maximal weight loss (mean) (A, E), D3 nasal turbinate virus load (GM) (B, F), D3 lung virus load (GM) (C, G), and D3 total lung scores (mean) (D, H). Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s multiple comparison test comparing all immunized groups to the saline control group, with the exception of Delta challenge D3 lung viral load where all comparisons were made to the Gamma vaccine group.

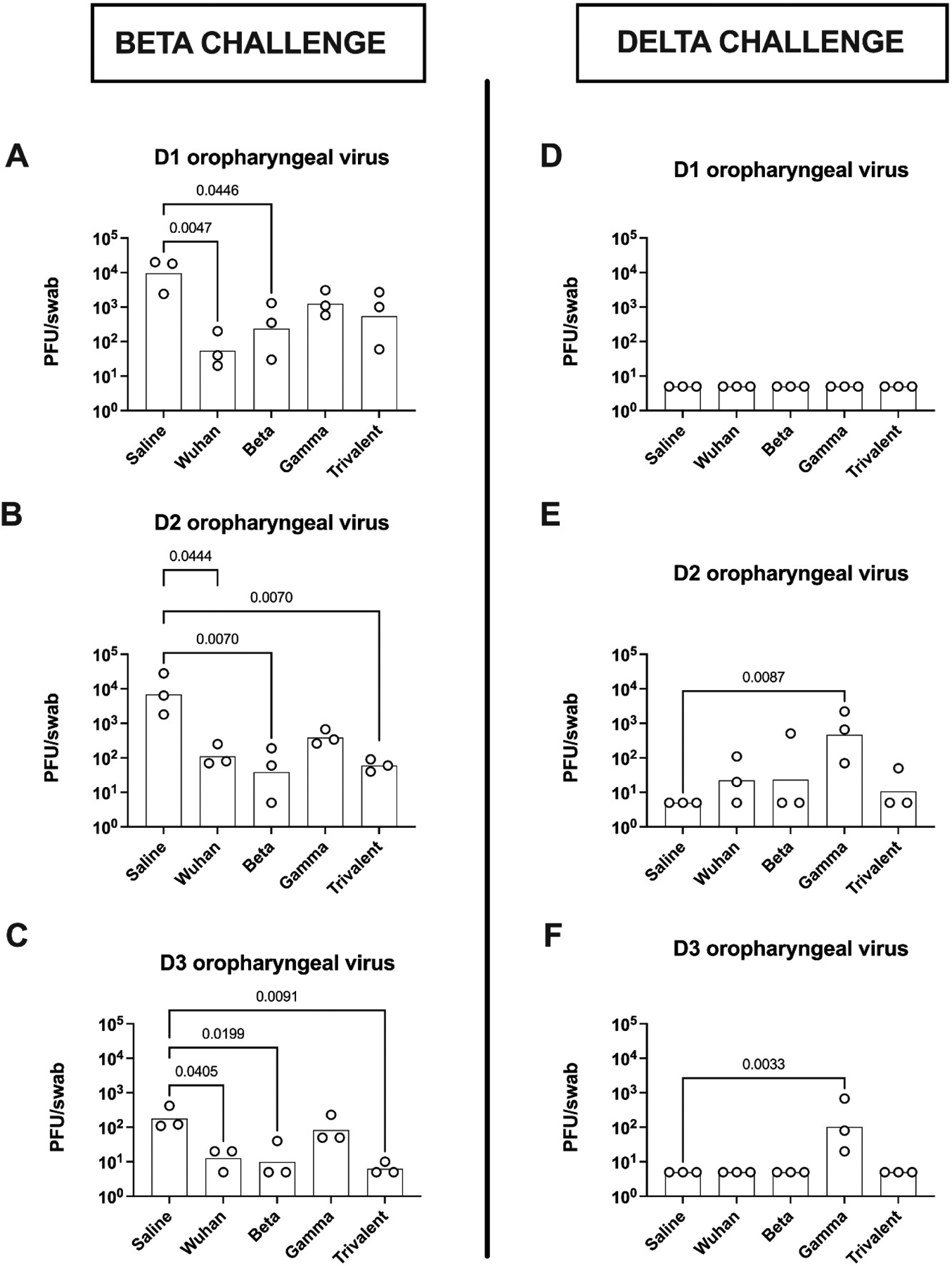

Figure 4. Oropharyngeal virus shedding.

Starting one day post-challenge with either Beta variant (left column) or Delta variant (right column), hamsters had oropharyngeal swabs performed daily for 3 days for assessment of virus load. Statistical analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s multiple comparison test to compare all immunized groups to the saline group.

Vaccine protection against Beta virus challenge

Two weeks after the second vaccine dose, hamsters were challenged intranasally with Beta virus variant, hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP01542/2021. Mean maximal weight loss in response to Beta infection ranged from 4.6% in the saline control group down to 2.0% in the trivalent vaccine group (Fig. 3A). Of the monovalent vaccine groups, the homologous Beta vaccine was associated with the least maximal weight loss (3.3%), followed by the Wuhan vaccine (3.9%) and with the greatest weight loss in the Gamma vaccine group (4.2%).

D3 nasal turbinate load for the Beta virus was high across all groups, consistent with establishment of a successful infection. As compared to the infected control animals, turbinate virus loads were significantly reduced in the Wuhan and trivalent vaccine groups (Fig. 3B). This reduction in viral load in the Wuhan and trivalent vaccine groups was even more striking for D3 lung viral load, with virus being undetectable in these two groups (Fig. 3C). Surprisingly, all animals in the Beta vaccine group (homologous to the challenge virus) had detectable D3 lung virus. Overall, the D3 nasal turbinate were concordant with the D3 lung, virus loads (Table 1).

Table 1.

Virus titers in Beta (A) or Delta (B) virus challenged animals and their naïve co-housed recipients

| A | Beta challenged hamsters | Naive transmission recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal virus shedding | Turb. | Lung | Nasal virus shedding | Turb. | Lung | ||||||

| (pfu/swab) | (pfu/100 mg) | (pfu/100 mg) | Nasal virus shedding (pfu/swab) | (pfu/100 mg) | (pfu/100 mg) | ||||||

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D3 | D3 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D4 | D4 | |

| Saline-1 | 2,400 | 1,800 | 110 | 55,000,000 | 3,900,000 | <10 | 110 | 1,400 | 420 | 110,000 | 96,000 |

| Saline-2 | 20,000 | 28,000 | 120 | 86,000,000 | 580,000 | <10 | 620 | 1,000 | 310 | 94,000 | 250 |

| Saline-3 | 18,000 | 6,400 | 420 | 92,000,000 | 4,800,000 | ||||||

| Wuhan-1 | 200 | 70 | 20 | 230,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Wuhan-2 | 40 | 250 | <10 | 580,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Wuhan-3 | 20 | 80 | 20 | 410 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Beta-1 | 30 | <10 | <10 | 3,300,000 | 120 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Beta-2 | 350 | 60 | 40 | 32,000,000 | 1,600 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Beta-3 | 1,300 | 190 | <10 | 3,700,000 | 460,000 | <10 | <10 | 40 | 520 | 5,800 | <10 |

| Gamma1 | 1,100 | 340 | 50 | 2,400,000 | 29,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Gamma2 | 580 | 260 | 230 | 2,400,000 | 73,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Gamma3 | 3,100 | 670 | 50 | 510,000 | 130,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Tri-1 | 2,700 | 60 | <10 | 1,600,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Tri-2 | 60 | 40 | <10 | 53,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Tri-3 | 1,000 | 90 | <10 | 65,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| B. Delta challenged hamsters | |||||||||||

| Saline-1 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1,800 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 1,100 | 640 | 23,000 | <10 |

| Saline-2 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 670,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Saline-3 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 24,000 | 5,100 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 29,000 | <10 |

| Wuhan-1 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 50 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Wuhan-2 | <10 | 110 | <10 | 130 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 350 | 2,200 | 58,000 | <10 |

| Wuhan-3 | <10 | 20 | <10 | 340 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Beta-1 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 6,500 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Beta-2 | <10 | 510 | <10 | 48,000 | 15,000 | <10 | <10 | 210 | 3,000 | 74,000 | <10 |

| Beta-3 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 28,000 | 30 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Gamma1 | <10 | 70 | 20 | 770,000 | 21,000 | <10 | <10 | 160 | 32 | 11,000 | <10 |

| Gamma2 | <10 | 2,200 | 680 | 1,600,000 | 350,000 | <10 | <10 | 20 | 57 | 1,900 | <10 |

| Gamma3 | <10 | 660 | 80 | 550,000 | 43,000 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Tri-1 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Tri-2 | <10 | <10 | <10 | 180 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| Tri-3 | <10 | 50 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

D3 lung pathology as assessed by total lung scores performed by a blinded pathologist, was lowest for the Wuhan and trivalent vaccine groups, consistent with these groups having the lowest viral loads. Conversely, the Gamma vaccine group showed significantly higher lung scores than even the infected saline control group (Fig 3D).

To assess vaccine effects on nasal viral replication and shedding over time, oropharyngeal swabs were taken daily on D1–3 post challenge (Fig. 4). Oropharyngeal viral load in the control animals was high on D1 and D2 and reduced by ~100-fold on D3, consistent with rapid clearance of SARS-CoV-2 even in naïve hamsters, with most if not all virus cleared by D4–5 in this model (unpublished data). D1 oropharyngeal viral loads were lower in the vaccinated when compared to the saline control animals, with significant reductions at D1 in the Wuhan and Beta vaccine groups, and at D2 and D3 in the Wuhan, Beta and trivalent vaccine groups (Fig. 4 A–C). D1-D3 oropharyngeal viral loads in the Gamma vaccine group, were not significantly different to the saline control group.

Protection against Delta variant infection

Two weeks after the second vaccine dose, hamsters in the Delta challenge group were intranasally infected with hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021 virus. Mean maximum weight loss ranged from 8.4% in the saline control group down to 5.1% in the trivalent vaccine group. Of the monovalent vaccines, the Beta vaccine was associated with the least weight loss (5.6%), as compared to the Wuhan (6.5%) and Gamma (8.0%) vaccine groups (Fig. 3B).

Despite Delta challenged animals having greater weight loss than those challenged with Beta virus, D1–3 oropharyngeal virus swabs in the Delta challenged group, including those from the saline control animals, were largely negative with the exception was the Gamma vaccine group where virus was still detectable on D2 and D3 in oropharyngeal swabs of all, despite being negative even in control animals (Fig. 4 D–F).

Delta virus was still present in the D3 nasal turbinate in most animals (Fig 2F). The trivalent vaccine group had the lowest D3 turbinate virus load followed by the Wuhan vaccine group. The Beta and Gamma vaccine groups had the highest D3 turbinate virus loads, with the Gamma vaccine group having a higher virus load than even the control group. Lung virus loads showed a similar pattern to nasal turbinate virus load with higher D3 lung virus loads in the Gamma vaccine group than even the saline control group. By contrast, no D3 lung virus was detectable in the trivalent and monovalent Wuhan vaccine groups (Fig. 3D).

Relationship between serum neutralizing antibody levels pre-challenge and clinical outcomes

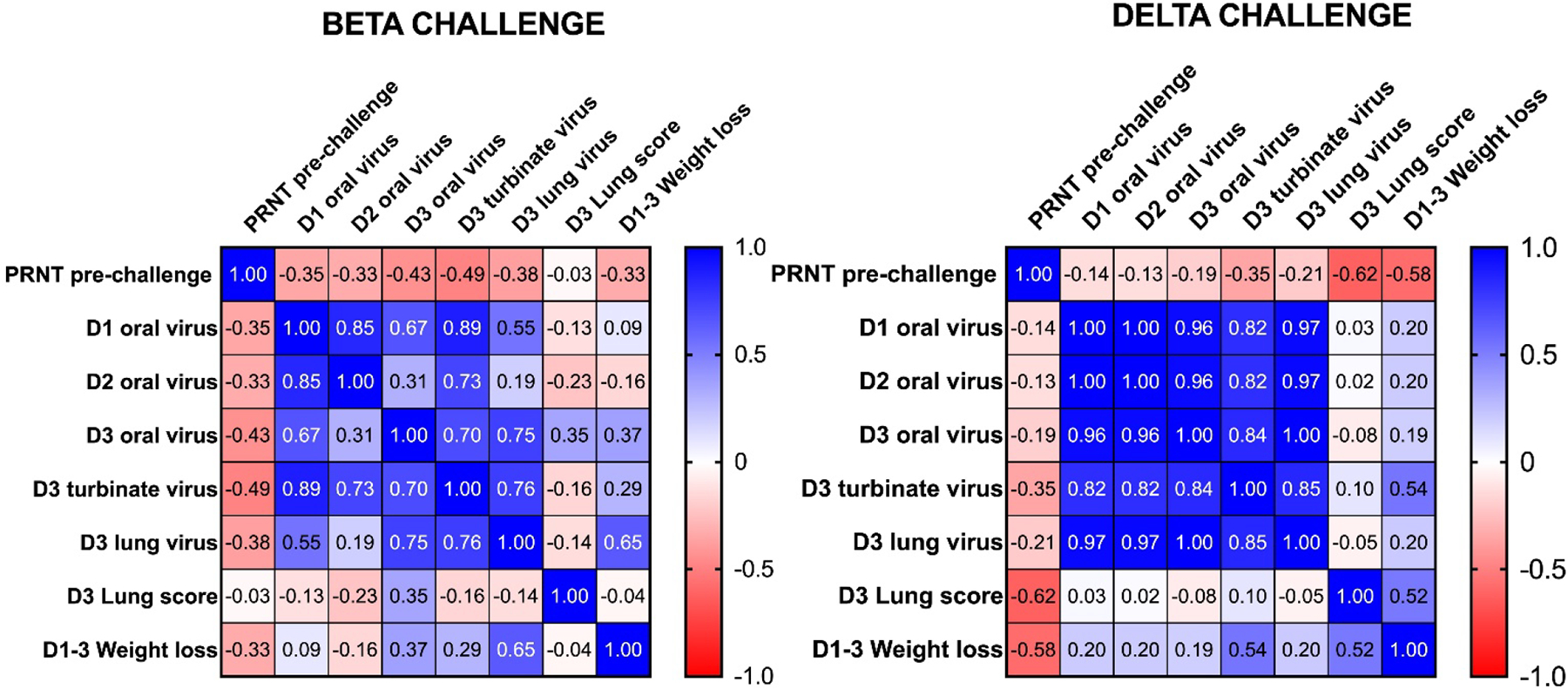

A correlation matrix was generated of Pearson correlation coefficients of PRNT50 levels pre-challenge, and viral loads in D1–3 oropharyngeal swabs, D3 nasal turbinate and D3 lungs, weight loss and lung scores after challenge with either Beta (Fig. 5A) or Delta virus (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Correlations of pre-challenge neutralizing antibody levels and clinical disease in challenged hamsters.

A correlation matrix was generated in Prism of Pearson correlation coefficients for PRNT50 levels pre-challenge and post challenge D1–3 oropharyngeal virus load, D3 turbinate and lung viral load, D3 total lung scores and D1-D3 maximal weight loss for hamsters challenged with either Beta (A) or Delta (B) virus.

For the Beta virus challenges, there were negative correlations between PRNT50 levels and D1–3 oropharyngeal virus loads (r= −0.35, −0.33, and −0.43, respectively), D3 turbinate viral load (−0.49, p= 0.064) and lung viral load (−0.38, p= 0.17) as well as D1–3 mean weight loss (−0.33), although none of these trends reached statistical significance. D1–3 weight loss was significantly correlated with D3 lung viral load (r= 0.65, p= 0.009). Interestingly, there was no correlation between Beta neutralizing antibody levels and total lung scores. Total lung scores also showed little correlation with D3 turbinate, or lung virus loads or weight loss. Hence, pre-challenge Beta neutralizing antibody levels were most closely related to reduced viral loads rather than to reduced disease severity as indicated by weight loss and total lung scores.

For the Delta virus challenged animals, there was a significant negative correlation between Delta neutralizing antibody levels and total lung scores (r = −0.62, p = 0.013) and between neutralizing antibody levels and weight loss (r = −0.58, p = 0.023). Weight loss was positively correlated with D3 turbinate viral load (r = 0.54, p = 0.038) and with D3 total lung score (r = 0.52, p = 0.044). However, there was only a weak nonsignificant trend to a negative correlation between Delta neutralizing antibody and D3 nasal turbinate or lung viral loads. Hence, pre-challenge Delta neutralizing antibody levels were most closely related with reduced disease severity as measured by reduced weight loss and total lung scores rather than reduced viral loads, the opposite of what was seen for the Beta virus.

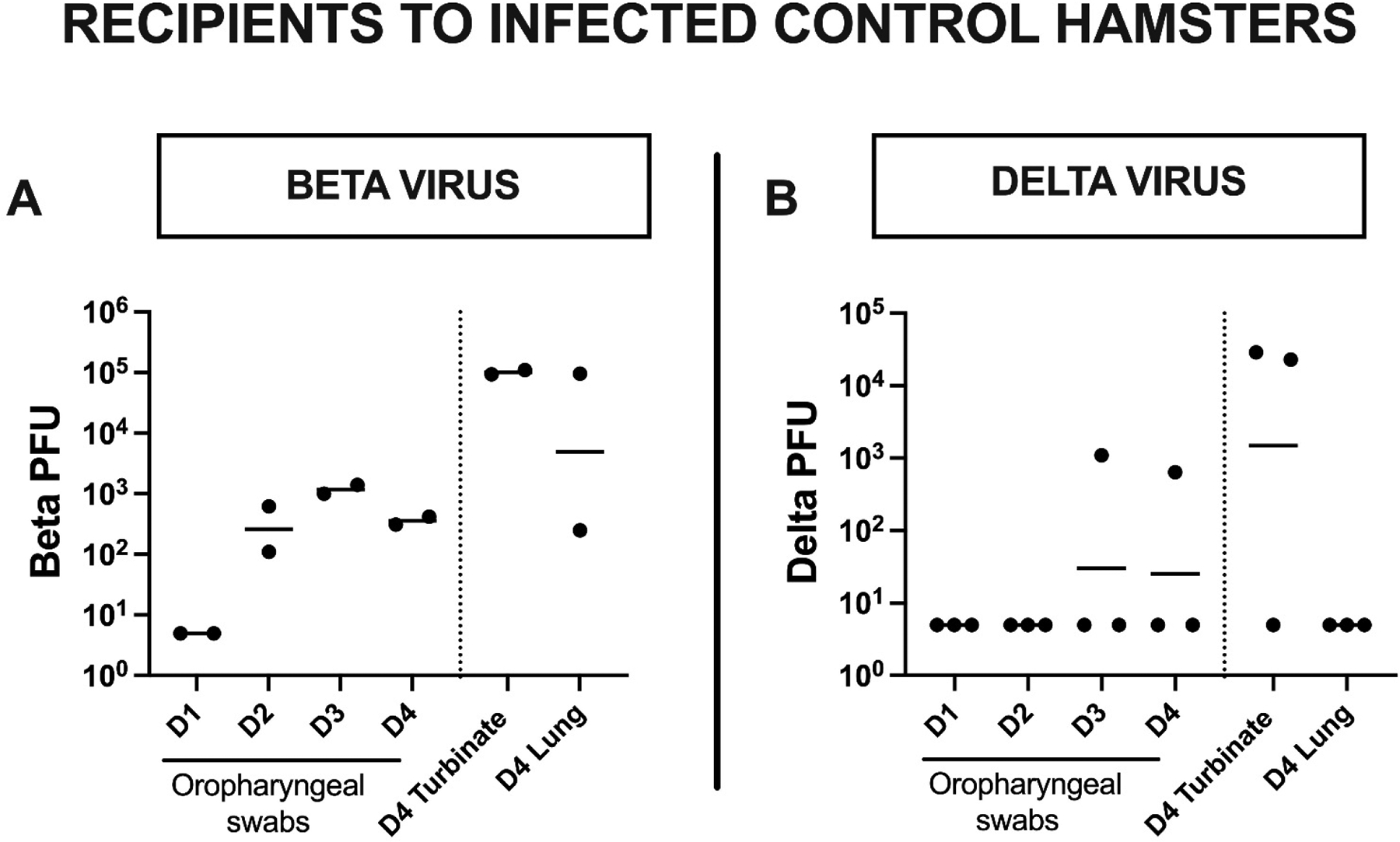

Vaccine effects on virus transmission

Infected hamsters were assessed for their ability to transmit infection to vaccine-naïve recipients into whose cages they were placed on D2 post-infection. Two of two (100 %) Beta virus challenged saline control animals transmitted Beta infection to their recipients as indicated by positive D3 and D4 oropharyngeal swabs and positive nasal turbinate and lung virus at termination on D4 (Fig. 6A). None of the infected animals in the vaccinated groups transmitted Beta infection to their recipients, except for one animal in the Beta vaccine group (Table 1).

Figure 6. Infection of naïve recipients by infected saline-control hamsters.

Two days post-challenge, each infected hamster was placed in a cage containing a single naïve animal (the recipient) for one day to assess for the ability of the infected animal to transmit the infection. Shown are virus loads in D1–4 oropharyngeal swabs, D4 nasal turbinate and D4 lung of each recipient housed with a Beta (A) or Delta (B) virus challenged saline control hamster (the donor).

Two of three (66.6%) Delta virus infected saline control animals transmitted Delta infection to their recipients. Both these Delta infected recipients were positive at termination on D4 for nasal turbinate but not for lung virus and only one had positive D3 and D4 oropharyngeal swabs (Fig. 4B). The trivalent vaccine showed robust protection against Delta virus transmission with no infection being established in any of this group’s recipient animals (Table 1). By contrast, two of three (66.6%) animals in the Gamma vaccine group transmitted Delta infection to their recipients.

DISCUSSION:

SARS-CoV-2 virus infections have continued unabated despite widescale global roll-out of vaccines and declaration of the end of the pandemic phase. Most infections in heavily vaccinated countries necessarily represent vaccine-breakthrough infections, highlighting ongoing problems of vaccine leakiness, rapidly waning immunity, and the difficulties of protecting against multiple vaccine-escape variants [22]. This issue of vaccine-breakthrough variants was highlighted in early South African trials where the Beta variant was prevalent with the AstraZeneca adenovirus vaccine failing to protect against infection [23], even although this vaccine showed efficacy in trials in other countries where other variants such as Alpha were dominant [24]. In mid-2021, the Delta variant rapidly became the dominant global strain. Delta’s spread in countries such as Israel coincided with waning immunity from vaccines administered in early 2021, with minimal residual protection against Delta infection by 6 months post the second mRNA vaccine dose [25]. The early hope that vaccines might help reduce large community outbreaks of Delta was dashed by data showing that peak nasal virus loads of the Delta variant were similar in infected vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals [26]. In late 2021/early 2022 Delta was in turn replaced by Omicron BA.1 and BA.2, highlighting the challenges being faced by vaccine developers in trying to keep up with rapidly evolving immune-escape variants. This emphasizes the importance of developing next-generation COVID-19 vaccines able to broadly protect against infection and transmission of a wide range of SARS-CoV-2 variants.

It remains unclear what might be the best next-generation vaccine strategy to produce broad protection against newly emerging variants. One approach could be to progressively add additional spike protein variants to the original Wuhan-based vaccines, thereby generating a multivalent vaccine, as exemplified by the bivalent mRNA vaccines encoding both Wuhan and BA.5 spike proteins [27]. An alternative approach would be to continue with a monovalent vaccine platform and progressively substitute it with the latest spike protein variant, as exemplified by the planned next season monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5 vaccines. This study thereby sought to compare the effectiveness of SpikoGen®, our original monovalent Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted Wuhan-strain spike protein vaccine, with substituted Beta or Gamma spike protein monovalent versions versus the multivalent strategy using all three spike proteins combined. These vaccines were first assessed for their ability to induce broadly neutralizing antibodies in mice and then for their ability to protect hamsters against challenge with either Beta or Delta virus variants. As an extension of the hamster study, the ability of the vaccines to prevent virus transmission from infected animals to naïve recipients was also assessed. The study thereby allowed a direct comparison of the effectiveness of different monovalent and multivalent vaccine formats against multiple heterologous virus variants, assessing both clinical endpoints but also transmission.

An early key study finding was just how differently the Beta and Delta virus variants behaved when tested in parallel. Infection with the Beta variant was associated with high nasal turbinate viral loads but with low disease severity and transmission, whereas infection with the Delta variant was associated with lower viral loads but more severe disease and more predisposition to vaccine-breakthrough transmissions. This study design thereby provided an ideal opportunity to identify which vaccine format might provide the broadest protection against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants. Notably, the trivalent vaccine containing Wuhan, Beta and Gamma spike proteins with Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvant provided the best protection against both viruses, despite containing only one third the amount of each individual spike protein variant as the monovalent vaccines. In the case of the Beta virus challenge, hamsters that received the trivalent vaccine exhibited the least weight loss and oropharyngeal virus shedding, with undetectable virus in D3 lung and nasal turbinate, low total lung scores and no virus transmission to naïve recipients. In the case of the Delta virus challenge, the trivalent vaccine was again associated with minimal oropharyngeal virus shedding, undetectable virus in D3 lung and nasal turbinate, low lung scores and no transmission to naïve recipients. Interestingly, the next best performing vaccine against both the Beta and Delta variants was the original monovalent Wuhan-based SpikoGen® vaccine. This came as a surprise as the Wuhan spike protein was heterologous to both challenge viruses, whereas the Beta spike protein was homologous to the Beta virus. The hamsters immunized with the homologous monovalent Beta vaccine showed only partial protection when challenged with Beta virus with high nasal turbinate virus loads and positive lung virus in all three animals and with transmission seen to one recipient of this group. Hence, to our surprise the heterologous Wuhan vaccine protected better against the Beta variant, than the homologous Beta vaccine. The Beta vaccine was also less protective than the Wuhan vaccine against Delta infection. This finding was of interest as previously bivalent vaccines comprising Wuhan and Beta spike protein were taken into human clinical trials [28], before being discontinued in favor of the Omicron bivalent formulations.

Overall, the Gamma vaccine was the worst performing and gave minimal protection against either Beta or Delta infection. Gamma vaccinated animals showed high D3 nasal turbinate and lung virus loads and total lung scores. They exhibited the highest D1-D3 oropharyngeal virus shedding and 2 of 3 of the Delta challenged animals transmitted infection to their recipients. The increased severity of infection seen in the Gamma vaccine group could suggest vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease (VAERD) and/or ADE, as has been reported to occur for other coronavirus infections [29]. The possibility of VAERD/ADE occurring in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 virus infected has suggested by some in vitro and preclinical studies [30]. Although it has yet to be clearly confirmed to occur in human infections, a large epidemiological study identified double the risks of death, hospitalization and other adverse sequelae in those experiencing a SARS-CoV-2 re-infection [31], which could thereby represent a potential signal of ADE.

ADE is generally seen in a setting where non-neutralizing antibody, through facilitation of binding and virus internalization by cellular Fc receptors, allows a virus to be taken up by and infect tissues that do not express the normal viral receptor [32]. In dengue infections, Fc-mediated viral entry (FVE) enables the virus to enter and replicate in immune cells, resulting in profound immune disturbances and cytokine storms [33]. Viral entry into immune cells via FVE may also enable virus to interfere with normal antiviral immune functions such as type 1 interferon production or antigen presentation and T and B cell activation [34]. ADE is most likely to be seen when the vaccine antigen has a poor antigenic match to the key neutralizing epitopes on the infecting virus strain. This could describe the Gamma vaccine when considered in relation to a Beta or Delta virus challenge, as the murine studies showed the Gamma vaccine induced Beta and Delta spike protein binding IgG, but not anti-RBD IgG or any neutralizing activity against these strains. This makes it plausible that a form of ADE was responsible for the more severe infections seen in the Gamma immunized hamsters.

A recent study compared the effect of human SARS-CoV-2 convalescent on FVE into FcgRIIa-expressing HEK293 cells versus its virus neutralizing activity [35]. It found there was a functional shift in convalescent plasma antibodies from combined neutralizing and FVE activity against the ancestral strain, to just FVE activity and no neutralization activity against the Beta and Gamma variants. This would support the possibility that ADE could occur with SARS-CoV-2 in specific contexts where non-neutralizing antibody with FVE activity is present but neutralizing antibody is absent. Notably, our data showed that the mice that received the Gamma vaccine had the highest ratio of total spike IgG to anti-RBD IgG for all virus variants. Interestingly, a recent study reported that anti-spike monoclonal antibodies from convalescent COVID-19 patients that target the spike protein N-terminal domain (NTD) can enhance spike protein binding to ACE2 through inducing an RBD-open conformation and can thereby increase the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 virus [36]. This could thereby represent a further form of ADE operating in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Hence, non-neutralizing antibodies could increase SARS-CoV-2 infectivity through multiple ADE mechanisms, including enhancement of ACE2 binding as well as through traditional Fc-mediated mechanisms. VAERD was previously observed in models of SARS coronavirus infection, with animals vaccinated with spike protein vaccines, particularly vaccines containing alum adjuvant, developing exacerbated lung disease highlighted by eosinophilic pneumonitis upon SARS infection [37]. Interestingly, simply re-formulating these SARS spike protein vaccines with Advax-CpG adjuvant was shown to protect against both SARS infection and VAERD [11]. This correlated with an enhanced T cell interferon-gamma recall response, showing that the Advax-CpG adjuvant strengthened the Th1 memory T cell response and prevented the excess Th2 skewing of the immune response to SARS infection associated with VAERD. Notably, we did not see any abnormal eosinophilia in the lungs of the Gamma immunized hamsters, suggesting a different mechanism underlying their VAERD to that seen in SARS.

It was interesting that there was no suggestion of disease enhancement in hamsters that received SpikoGen® vaccine based on the original Wuhan spike protein, despite the SpikoGen® Wuhan-based spike protein being heterologous to both the Beta and Delta challenge viruses. This might reflect be because the Wuhan spike protein is ancestral to both Beta and Delta spike proteins and thereby still shares key epitopes in common with each of them. Advax-CpG adjuvant may also help prevent ADE, as in previous studies of an inactivated Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) vaccine, immune sera of mice immunized with antigen alone or formulated with alum adjuvant exhibited enhanced dengue virus infectivity in an in vitro ADE assay, whereas immune sera of mice immunized with the same JEV antigen with Advax-CpG adjuvant were negative in the ADE assay but still bound and neutralized the heterologous dengue virus [38]. Similarly, immune sera of mice immunized with a Ebola viral-like particle vaccine when formulated with Advax-CpG adjuvant were able to transfer protection against a lethal Ebola infection to naïve mice, whereas immune sera from mice immunized with the same Ebola vaccine formulated with a TLR3 adjuvant failed to transfer protection [39]. A non-human primate study of a replication-defective human cytomegalovirus vaccine candidate which compared Advax, Advax-CpG and lipid nanoparticle (LNP) adjuvants showed the Advax adjuvants promoted both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses whereas the LNP adjuvant promoted primarily CD4 responses and transcriptome analyses of peripheral blood samples showed that the LNP adjuvant upregulated innate immune response genes similar to those induced by viral infection and traditional inflammatory adjuvants whereas the Advax adjuvants did not activate known inflammatory pathway genes and instead upregulated an unusual constellation of genes associated with developmental and metabolic pathways [40]. This supports the idea that Advax adjuvants are working via a unique non-inflammatory mechanism of action. Advax was shown in one study to act as an ‘adjuvant of adjuvants’, potentiating the intrinsic self-adjuvanting activity of an inactivated influenza virus vaccine [40]. The adjuvant of adjuvants property of Advax (delta inulin) was exploited to good effect in the combined Advax-CpG formulations, where synergistic adjuvant effects are obtained by co-formulating delta inulin with a TLR9 active CpG oligonucleotides, translating into enhanced vaccine protection against a broad range of infections and other diseases, including viruses, e.g. influenza [41], bacteria, e.g. mycobacterium tuberculosis [42], parasites, e.g. Onchocerca volvulus [43], as well as pollen allergy [44], Alzheimer’s disease [45] and opioid addiction [46], amongst others.

The study results give additional insights into the impact of COVID-19 vaccines on virus transmission. The nasal turbinate virus load in the donor animal appeared to be the best predictor for virus transmission with neither the level of oropharyngeal virus shedding or lung virus load predicting transmission to naïve recipients. Hence, vaccines able to completely block viral replication in the nasal turbinates might offer the best means to prevent ongoing community spread of SARS-CoV-2 [47]. While studies in animals and humans have shown a good correlation between serum spike antibody levels and protection against severe systemic disease [48–50], mRNA vaccinated individuals with breakthrough Delta infections were shown to have similar peak viral loads to unvaccinated individuals [51, 52], albeit with the possibility of slightly earlier viral clearance [26]. The transmission studies suggest that despite being delivered via intramuscular injection, SpikoGen® vaccine may induce some degree of mucosal immunity, although the extent and mechanism for this still needs to be elucidated. The mechanism whereby the vaccines reduced nasal turbinate virus loads is not known, but mimics findings from SpikoGen® vaccine studies involving homologous Wuhan virus challenges in ferrets [17] and hamsters [18]. Vaccine-induced T cells may play an important role in mucosal protection, and in the absence of neutralizing antibodies systemic or lung-resident memory CD4 and CD8 T cells were shown to provide protection against Beta variant infection [53]. SpikoGen® vaccine has previously been shown to induce a strong CD4 and CD8 T cell memory response with potent in vivo cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity against spike protein-labelled target cells [20]. Other than the issues with the monovalent Gamma vaccine, no safety issues were encountered during the study. This further supports the safety of the platform, with a recent study confirming the reproductive and developmental safety of Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted monovalent and multivalent rSp vaccines, including when combined with an influenza vaccine [54].

This study has a number of limitations. Small hamster group sizes were required to accommodate the large number of groups, with half the animals needing to be challenged with each virus variant. There was unfortunately no opportunity to repeat the hamster challenge study. However, the murine immunogenicity studies were repeated multiple times and consistently confirmed the poor ability of the Gamma vaccine to induce anti-RBD IgG and neutralizing antibody. There was a high consistency in the immunogenicity results of the murine and hamster studies. The immunogenicity and clinical outcomes within each group of challenged hamsters were also highly consistent. Another limitation was that challenges were performed 2 weeks after the second vaccine dose, following the procedure used in other reported hamster studies [55–58]. As serum spike antibody levels are known to rapidly wane [59], it will be important in future studies to also evaluate the durability of protection afforded by the different vaccine approaches. Delayed challenges might be particularly useful to study whether any VAERD/ADE features worsen if additional time is allowed for antibody levels to wane before challenge. A further limitation of this study was the inability to collect T cell data, as T cells appear to play a major role in control of SARS-CoV-2 infection particularly in absence of neutralizing antibody [53].

In conclusion, the study results confirmed that the current SpikoGen® vaccine based on Wuhan spike protein was still able to protect against clinical disease and lung infection caused by either the Beta or Delta virus variants but suggested additional protection may be obtained by adding extra variant spike proteins to make a multivalent formulation. Notably, this was the first study to confirm that Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted spike protein vaccines can prevent SARS-CoV-2transmission to naïve recipients. The higher viral loads and clinical disease seen in the animals that received the Gamma spike vaccine suggest that VAERD/ADE could occur in situations where only non-neutralizing antibody is present against the infecting variant. This study highlights the ongoing complexity of optimizing vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants. It is important that there be continued pursuit of new and improved COVID-19 vaccines that provide robust long-lasting and broadly cross-protective immunity to cover the wide range of evolving SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. At necropsy, portions of the left and the right medial lung lobes were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for seven days then paraffin embedded, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using routine methods for histological examination. Histopathology was blindly interpreted by a veterinary pathologist (HBO). H&E-stained lung tissue sections were examined and microphotographed using a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi1 microscope and NIS-Elements F4.60.00 software. The H&E-stained slides were assessed for morphological evidence of inflammatory-mediated pathology in lung and trachea and reduction or absence of pathological features used as an indicator of vaccine-associated protection. Each hamster was assigned a score of 0–5 based on absent, mild, moderate, or severe manifestation, respectively, for each manifestation of pulmonary pathology including overall lesion extent, bronchitis, alveolitis, pneumocyte hyperplasia and vasculitis and then the sum of all scores for each hamster calculated. Histology of a representative animal from each group is shown at 3 magnifications, with mean lung score (MLS) for the group shown to the right of the figure.

Highlights for review:

Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted monovalent or trivalent recombinant spike protein vaccine protected hamsters against challenges with Beta or Delta viruses

In naïve animals, the Beta variant caused higher virus loads in the upper respiratory tract whereas Delta variant caused greater transmission and more severe disease

The trivalent formulation of Wuhan, Beta and Gamma spike proteins provided the best overall protection, even although it contained only one third of the amount of spike protein for each variant as contained in the monovalent vaccines

Hamsters immunized with Gamma spike vaccine had higher virus loads than unvaccinated infected animals suggesting the possibility of VAERD and/or ADE

The trivalent and Wuhan monovalent vaccines reduced the risk of transmission to naïve co-housed animals

Nasal turbinate virus load correlated best with virus transmission to naïve animals

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Lei Li for assistance in development of the vaccines and the pVNT assays and Anna Antipov for assistance with coordinating the assays and results. This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Contract HHSN272201400053C, HHSN272201800044C, and HHSN272201800024C, and funding from the MTPConnect Biomedical Translation Bridge Program, Vaxine Pty Ltd, Macrovax Trust and a Fast Grant administered by George Mason University. BEI Resources provided the challenge viruses B.1.351 (Beta), SARS-CoV-2 hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP01542/2021, BEI NR-55282 and B.1.617.2 (Delta), SARS-CoV-2 hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021, BEI NR-55672.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COMPETING INTERESTS

NP and YHO are affiliated with Vaxine Pty Ltd which holds the rights to COVAX-19®/SpikoGen® vaccine and Advax™ and CpG55.2™ adjuvants.

REFERENCES:

- [1].Zhang Y, Zhang H, Zhang W. SARS-CoV-2 variants, immune escape, and countermeasures. Front Med. 2022;16:196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zabidi NZ, Liew HL, Farouk IA, Puniyamurti A, Yip AJW, Wijesinghe VN, et al. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Implications on Immune Escape, Vaccination, Therapeutic and Diagnostic Strategies. Viruses. 2023;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pollet J, Chen W-H, Strych U. Recombinant protein vaccines, a proven approach against coronavirus pandemics. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Clark T, Cassidy-Hanley D. Recombinant subunit vaccines: potentials and constraints. Developments in biologicals. 2005;121:153–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Petrovsky N, Cooper PD. Advax™, a novel microcrystalline polysaccharide particle engineered from delta inulin, provides robust adjuvant potency together with tolerability and safety. Vaccine. 2015;33:5920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Thomas S, Abraham A, Baldwin J, Piplani S, Petrovsky N. Artificial Intelligence in Vaccine and Drug Design. Vaccine Design: Springer; 2022. p. 131–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Görander S, Honda-Okubo Y, Bäckström M, Baldwin J, Bergström T, Petrovsky N, et al. A truncated glycoprotein G vaccine formulated with Advax-CpG adjuvant provides protection of mice against genital herpes simplex virus 2 infection. Vaccine. 2021;39:5866–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sakala IG, Honda-Okubo Y, Li L, Baldwin J, Petrovsky N. A M2 protein-based universal influenza vaccine containing Advax-SM adjuvant provides newborn protection via maternal or neonatal immunization. Vaccine. 2021;39:5162–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Honda-Okubo Y, Baldwin J, Petrovsky N. Advax-CpG Adjuvant Provides Antigen Dose-Sparing and Enhanced Immunogenicity for Inactivated Poliomyelitis Virus Vaccines. Pathogens. 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eichinger KM, Kosanovich JL, Gidwani SV, Zomback A, Lipp MA, Perkins TN, et al. Prefusion RSV F immunization elicits Th2-mediated lung pathology in mice when formulated with a Th2 (but not a Th1/Th2-balanced) adjuvant despite complete viral protection. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020:1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Honda-Okubo Y, Barnard D, Ong CH, Peng B-H, Tseng C-TK, Petrovsky N. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus vaccines formulated with delta inulin adjuvants provide enhanced protection while ameliorating lung eosinophilic immunopathology. Journal of virology. 2015;89:2995–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Adney DR, Wang L, Van Doremalen N, Shi W, Zhang Y, Kong W-P, et al. Efficacy of an adjuvanted Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein vaccine in dromedary camels and alpacas. Viruses. 2019;11:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tabarsi P, Anjidani N, Shahpari R, Mardani M, Sabzvari A, Yazdani B, et al. Evaluating the efficacy and safety of SpikoGen(R), an Advax-CpG55.2-adjuvanted severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike protein vaccine: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tabarsi P, Anjidani N, Shahpari R, Mardani M, Sabzvari A, Yazdani B, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SpikoGen(R), an Advax-CpG55.2-adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 spike protein vaccine: a phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial in both seropositive and seronegative populations. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:1263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tabarsi P, Anjidani N, Shahpari R, Roshanzamir K, Fallah N, Andre G, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of SpikoGen(R), an adjuvanted recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein vaccine as a homologous and heterologous booster vaccination: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Immunology. 2022;167:340–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Honda-Okubo Y, Antipov A, Andre G, Barati S, Kafi H, Petrovsky N. Ability of SpikoGen(R), an Advax-CpG adjuvanted recombinant spike protein vaccine, to induce cross-neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Immunology. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li L, Honda-Okubo Y, Huang Y, Jang H, Carlock MA, Baldwin J, et al. Immunisation of ferrets and mice with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein formulated with Advax-SM adjuvant protects against COVID-19 infection. Vaccine. 2021;39:5940–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li L, Honda-Okubo Y, Baldwin J, Bowen R, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Petrovsky N. Covax-19/Spikogen(R) vaccine based on recombinant spike protein extracellular domain with Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvant provides single dose protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters. Vaccine. 2022;40:3182–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Honda-Okubo Y, Li L, Andre G, Leong KH, Howerth EW, Bebin-Blackwell AG, et al. An Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted recombinant spike protein vaccine protects cynomolgus macaques from a homologous SARS-CoV-2 virus challenge. Vaccine. 2023;41:4710–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li L, Honda-Okubo Y, Huang Y, Jang H, Carlock MA, Baldwin J, et al. Immunisation of ferrets and mice with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein formulated with Advax-SM adjuvant protects against COVID-19 infection. Vaccine. 2021;40: 5940–5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Amanat F, Stadlbauer D, Strohmeier S, Nguyen THO, Chromikova V, McMahon M, et al. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat Med. 2020;26:1033–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Akerman A, Milogiannakis V, Jean T, Esneau C, Silva MR, Ison T, et al. Emergence and antibody evasion of BQ, BA.2.75 and SARS-CoV-2 recombinant sub-lineages in the face of maturing antibody breadth at the population level. EBioMedicine. 2023;90:104545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Madhi SA, Baillie V, Cutland CL, Voysey M, Koen AL, Fairlie L, et al. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.351 Variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1885–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu-Raddad LJ, Andrews N, Araos R, Goldberg Y, et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399:924–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Singanayagam A, Hakki S, Dunning J, Madon KJ, Crone MA, Koycheva A, et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:183–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Offit PA. Bivalent Covid-19 Vaccines - A Cautionary Tale. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:481–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chalkias S, Eder F, Essink B, Khetan S, Nestorova B, Feng J, et al. Safety, immunogenicity and antibody persistence of a bivalent Beta-containing booster vaccine against COVID-19: a phase 2/3 trial. Nat Med. 2022;28:2388–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nakayama EE, Shioda T. SARS-CoV-2 Related Antibody-Dependent Enhancement Phenomena In Vitro and In Vivo. Microorganisms. 2023;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ebenig A, Muraleedharan S, Kazmierski J, Todt D, Auste A, Anzaghe M, et al. Vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory pathology in COVID-19 hamsters after T(H)2-biased immunization. Cell Rep. 2022;40:111214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat Med. 2022;28:2398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bournazos S, Gupta A, Ravetch JV. The role of IgG Fc receptors in antibody-dependent enhancement. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:633–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Narayan R, Tripathi S. Intrinsic ADE: The Dark Side of Antibody Dependent Enhancement During Dengue Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:580096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhang L, Feng X, Wang H, He S, Fan H, Liu D. Antibody-dependent enhancement of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection downregulates the levels of interferon-gamma/lambdas in porcine alveolar macrophages in vitro. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10:1150430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wieczorek L, Zemil M, Merbah M, Dussupt V, Kavusak E, Molnar S, et al. Evaluation of Antibody-Dependent Fc-Mediated Viral Entry, as Compared With Neutralization, in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front Immunol. 2022;13:901217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liu Y, Soh WT, Kishikawa JI, Hirose M, Nakayama EE, Li S, et al. An infectivity-enhancing site on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein targeted by antibodies. Cell. 2021;184:3452–66 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Honda-Okubo Y, Barnard D, Ong CH, Peng BH, Tseng CT, Petrovsky N. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus vaccines formulated with delta inulin adjuvants provide enhanced protection while ameliorating lung eosinophilic immunopathology. J Virol. 2015;89:2995–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Komiya T, Honda-Okubo Y, Baldwin J, Petrovsky N. An Advax-Adjuvanted Inactivated Cell-Culture Derived Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine Induces Broadly Neutralising Anti-Flavivirus Antibodies, Robust Cellular Immunity and Provides Single Dose Protection. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Stronsky SM, Cooper CL, Steffens J, Van Tongeren S, Bavari S, Martins KA, et al. Adjuvant selection impacts the correlates of vaccine protection against Ebola infection. Vaccine. 2020;38:4601–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Li H, Monslow MA, Freed DC, Chang D, Li F, Gindy M, et al. Novel adjuvants enhance immune responses elicited by a replication-defective human cytomegalovirus vaccine in nonhuman primates. Vaccine. 2021;39:7446–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Honda-Okubo Y, Bart Tarbet E, Hurst BL, Petrovsky N. An Advax-CpG adjuvanted recombinant H5 hemagglutinin vaccine protects mice against lethal influenza infection. Vaccine. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Counoupas C, Pinto R, Nagalingam G, Britton WJ, Petrovsky N, Triccas JA. Delta inulin-based adjuvants promote the generation of polyfunctional CD4(+) T cell responses and protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ryan NM, Hess JA, Robertson EJ, Tricoche N, Turner C, Davis J, et al. Adjuvanted Fusion Protein Vaccine Induces Durable Immunity to Onchocerca volvulus in Mice and Non-Human Primates. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11:1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tabynov K, Babayeva M, Nurpeisov T, Fomin G, Nurpeisov T, Saltabayeva U, et al. Evaluation of a Novel Adjuvanted Vaccine for Ultrashort Regimen Therapy of Artemisia Pollen-Induced Allergic Bronchial Asthma in a Mouse Model. Front Immunol. 2022;13:828690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hovakimyan A, Zagorski K, Chailyan G, Antonyan T, Melikyan L, Petrushina I, et al. Immunogenicity of MultiTEP platform technology-based Tau vaccine in non-human primates. NPJ Vaccines. 2022;7:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blake S, Bremer PT, Zhou B, Petrovsky N, Smith LC, Hwang CS, et al. Developing Translational Vaccines against Heroin and Fentanyl through Investigation of Adjuvants and Stability. Mol Pharm. 2021;18:228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Rethinking next-generation vaccines for coronaviruses, influenzaviruses, and other respiratory viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31:146–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Earle KA, Ambrosino DM, Fiore-Gartland A, Goldblatt D, Gilbert PB, Siber GR, et al. Evidence for antibody as a protective correlate for COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine. 2021;39:4423–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Garcia-Beltran WF, Lam EC, Astudillo MG, Yang D, Miller TE, Feldman J, et al. COVID-19-neutralizing antibodies predict disease severity and survival. Cell. 2021;184:476–88 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rogers TF, Zhao F, Huang D, Beutler N, Burns A, He WT, et al. Isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science. 2020;369:956–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Acharya CB, Schrom J, Mitchell AM, Coil DA, Marquez C, Rojas S, et al. Viral Load Among Vaccinated and Unvaccinated, Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Persons Infected With the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Brown CM, Vostok J, Johnson H, Burns M, Gharpure R, Sami S, et al. Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 Infections, Including COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Infections, Associated with Large Public Gatherings - Barnstable County, Massachusetts, July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1059–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kingstad-Bakke B, Lee W, Chandrasekar SS, Gasper DJ, Salas-Quinchucua C, Cleven T, et al. Vaccine-induced systemic and mucosal T cell immunity to SARS-CoV-2 viral variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119:e2118312119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sakala IG, Honda-Okubo Y, Petrovsky N. Developmental and reproductive safety of Advax-CpG55.2 adjuvanted COVID-19 and influenza vaccines in mice. Vaccine. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Corbett KS, Edwards DK, Leist SR, Abiona OM, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Gillespie RA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature. 2020;586:567–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gao Q, Bao L, Mao H, Wang L, Xu K, Yang M, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].van Doremalen N, Lambe T, Spencer A, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, Purushotham JN, Port JR, et al. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine prevents SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2020;586:578–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yu J, Tostanoski LH, Peter L, Mercado NB, McMahan K, Mahrokhian SH, et al. DNA vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Science. 2020;369:806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature Medicine. 2021;27:1205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. At necropsy, portions of the left and the right medial lung lobes were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for seven days then paraffin embedded, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using routine methods for histological examination. Histopathology was blindly interpreted by a veterinary pathologist (HBO). H&E-stained lung tissue sections were examined and microphotographed using a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi1 microscope and NIS-Elements F4.60.00 software. The H&E-stained slides were assessed for morphological evidence of inflammatory-mediated pathology in lung and trachea and reduction or absence of pathological features used as an indicator of vaccine-associated protection. Each hamster was assigned a score of 0–5 based on absent, mild, moderate, or severe manifestation, respectively, for each manifestation of pulmonary pathology including overall lesion extent, bronchitis, alveolitis, pneumocyte hyperplasia and vasculitis and then the sum of all scores for each hamster calculated. Histology of a representative animal from each group is shown at 3 magnifications, with mean lung score (MLS) for the group shown to the right of the figure.