Abstract

Endoscopic adenoidectomy with powered instruments,a challenge in resource-constraint developing countries, has been on the rise. To evaluate conventional curettage as compared to endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy in the successful management of adenoid enlargement. A randomized controlled double-blinded study among children undergoing adenoidectomywas done. Primary outcomes were assessed by pre- and postoperative evaluation with a symptoms questionnaire and fiberoptic nasal endoscopy. There were 71 children aged 3–15 years, majority having grade III adenoids. Conventional adenoidectomy was done by the surgeon who was blinded to preoperative adenoid status. Patients were randomized to two groups, 35in conventional curettage where no further on-table intervention was done. Check endoscopyof the remaining 36 patients, formingthe second group, revealed residual grade III adenoidsin 5.6%. They underwentcompletion adenoidectomyendoscopically. By the 12th postoperative week, nasal endoscopy noted that 39.3% had grade I/II and 8.8% had grade I in the conventional and endoscopic groups respectively. Thoughstatistically significant, all pre-op symptoms settled except sleep-related ones which persisted in both groups (25% versus 14.7) with no complications in either group. Relief of all symptoms other than sleep-related ones, was achieved despite residual adenoids being up to grade II in both conventional and endoscopic group. This suggests non-obstructive causes in a subset of these patients. Conventional adenoid curettage is comparable to endoscopic adenoidectomy by cold method among children aged three and above. Complete adenoidclearance for achieving ‘anatomical success’ appears not to be necessary for ‘clinical success’.

Keywords: Anatomical and clinical success, Conventional adenoidectomy, Endoscopic adenoidectomy

Introduction

Adenoidectomy, the removal of enlarged and obstructive or infected adenoids, has come a long way since its first description of ‘conventional curettage adenoidectomy (CCA)by Wilhelm Meyer in 1868 [1]. CCA was considered the surgical technique for adenoidectomy, which is done in isolation or along with tonsillectomy, until the past two decades. Since the advent of endoscopes, CCA is on the decline primarily due to the concern that as it is not being done under direct visionthere is incomplete removal of adenoids, persistence of infective or obstructive symptoms and recurrence, as well as risk of nasopharyngeal injury.

The prevalence of post-operative adenoid recurrence has been reported to be 2.1% in a recent retrospective case–control study among 1246 patients who underwent adenoidectomy with or without tonsillectomy. Adenoidectomy in all patients in this study was done by curettage under indirect vision using a mirror. The authors noted that risk factors of postoperative recurrence wereage of less than 2 years, allergy, recurrent middle ear infections/tonsillitis and primary surgeon being junior [3]. Regarding rate of revision adenoidectomy,two meta-analysis revealed that using different surgical techniques like curettage, suction cautery, microdebridement and coblation did not significantly affect revision rates in children [4, 5]. Recurrence rate in the latter study was 1.9% and was not related to age at initial surgeryorsurgeries in different settings (single center vs multicenter,population or country-based (non-United States vs United States) [5]. A retrospective study of four different adenoidectomy techniques over 10 years revealed that the percentages of revision adenoidectomy were most for micro-debridor (1.42%) and least for curette (0.03%) [6]. These observations suggest that the recurrence of adenoid tissue requiring revision adenoidectomy is uncommon and not generally related to the instrument used for its initial removal.

There has been a plethora of articles advocating the benefits of endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy with or without powered instruments. In a randomized single-blind study, significant on-table grade III residual adenoids were noted in the conventional group, unlike grade II which was present in both groups [7]. Similarly, near-total removal of adenoids was noted in powered instruments [8–11]. Regarding post operative pain, there has been variable reports. Comparative studies of conventional and endoscopic powered (microdebrider) adenoidectomy did not reveal significant differences [7, 9], significantly lesser in the curettage group as compared to coblator group [8] andlower in the radiofrequency group as compared tothe curettage group [8, 12]. Considering blood loss, it was noted more inmicro-debridor group than conventionalwhilecoblator group revealed a reduction in the mean blood loss [9, 10] .

A landmark article analyzing 15,734 patients in the National Tonsil Surgery Register in Sweden reported that when comparing dissection with hemostasis, secondary post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage was higher in all hot hemostasis and techniques (2.8 times higher following hot hemostasis, 3.2 times higher with incoblation and 4.3 times higher with diathermy scissors). It was also reported that the risk for 'return to theatre' following hemorrhage was higher for all hot techniques except for coblation [13]. Besides, longer duration of surgical time was noted in most of the studies with powered instruments [8, 9, 12]. A meta-analysis of available seven randomized controlled trials of endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy versus conventional curettage adenoidectomy revealed that EAA has advantages over CCA with regard to total operative time, blood loss, and complications [5].

However, these newer techniques with advanced instrumentation are often unavailable in resource-constrained developing countries. CCA continues to be a necessityforthis most common elective otolaryngologicalprocedure globally. This raises a concern forpracticingOtolaryngologistsregarding their inability to give the new possible standard of care for their patients [14]. Additionaly, considering ongoing ENTpostgraduate training, adenotonsillectomy is one of the first elective ENT surgical procedures that a trainee is exposed to, the objective being that by the end of the first year of training he/she can do this procedure confidently under supervision. Traditionally, adenoidectomy is taught by CCA. Using powered instruments in the early aspects of postgraduate training isan additional procedural challenge to the supervising surgeon as well asfor patient-related ethical concerns.

Ironically, to date, there is no data regarding the size of adenoids requiring conservative treatment or surgical removal, limits of complete clearance and possible regrowth or regression. Complete surgical clearance of adenoids (anatomical success), considering its immunological role in the young or extent of adenoids necessary to be removed for being symptom-free ('clinical success')is still debatable. This study was thus undertaken.

Methods

This study aimed to determine if endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy is superior to conventional curettage adenoidectomy, to ensure a symptom-free outcome. It was adouble-blind randomized controlled study conducted over 20 monthsin the department of a tertiary academic medical center. It was cleared by Institutional Review Board (IRB), Ethics Committee and was registered in the national CTRI registry (No. CTRI/2017/08/009458). Prior informed and written consent/assent were obtained duly from the participants and/ or their parents.

The inclusion criteria were all patients between 3 and 15 years attending the ENT outpatient department with complaints of snoring, sleeping with mouth open, mouth-breathing, nasal congestion, postnasal drainage or purulent anterior rhinorrhea, and nasal airway obstruction with or without sore throat and difficulty in swallowing, undergoing adenoidectomy or adenotonsillectomy. The exclusion criteria were nasal obstruction secondary to the severely deviated nasal septum or enlarged bilateral inferior turbinates, acute infection with fever and facial pain associated with congenital anatomical malformations, medical comorbidities, and patients who were on steroidal nasal sprays.

The outcome measures taken were:

Pre- and postoperative questionnaires in 6th and 12th week in both the groups for symptoms.

Intraoperative endoscopic assessment of adenoid remnants following conventional adenoidectomy

Postoperative 12th week endoscopic evaluation of adenoid remnant in both the study groups.

Patients were recruited in consecutive sequences and were randomized into two groups, in blocks of 20, using the internet-based software www.randomizer.org. Group A included conventional curettage adenoidectomy while Group B included endoscopic-assisted adenoidectomy.

A detailed symptom-related questionnaire was directed to patients and parents (or guardians) preoperatively, and also at 6th and 12th-week post-operative reviews. A pre-operative assessment on the table with grading of adenoids was done in all recruited patients by the supervising senior surgeon using a 0° rigid endoscope, based on the percentage of adenoid tissue that cause the blockage of posterior choana: Grade I –< 25%; Grade II obstructs > 25% to 50%; Grade III – > 50% to 75%; Grade IV – > 75% to 100% [15].

All the patients first underwent adenoidectomy by curettage, the operating surgeon being blinded to the preoperative endoscopic findings. The patients who were in group A had this conventional surgery alone and no further on-table endoscopy/curettage was done. In group B, a check endoscopy was done after the conventional curettage to document on-table immediate adenoid grading. Patients having adenoids more than grade II had completed adenoidectomy under endoscopic assistance.

All the patients (groups A and B) were then followed up at 6 weeks and 12 weeks with questionnaires. Repeat endoscopy was done in both groups at 12 weeks (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT

Results

Data analysis was done using Student's paired t-test for pre- and post-op comparison in each arm. Chi-squared test for comparison between the two arms. There were 71 patients in this study with ages ranging from three to 15 years. Among them,35 underwent conventional curettage adenoidectomy (group A) and 36 underwent endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy (group B). There were in total nine dropouts from the study, seven in conventional (group A) and two in endoscopic (group B), (Fig. 1). The baseline parameters are given in Table 1 and the two groups were comparable.

Table 1.

Baselinecharacteristics

| Parameter | Conventional | Endoscopic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 8.9 (SD2.9) | 9.1 (SD3.1) |

| 2 | Sex (M F) | 12:23 | 16:20 |

| 3 | Baseline Sleep Problem | 35/35 (100%) | 36/36 |

| 4 | Baseline School related | 6/35 (17%) | 7/36 (19%) |

| 5 | Ear Problems | 11/35 (31%) | 9/36 (25%) |

| 6 | Nose Problems | 22/35 (63%) | 18/36 (50%) |

| 7 | Grade of Adenoids | ||

| Grade-I | 4/35 (11%) | 2/36 (6%) | |

| Grade-II | 9/35 (26%) | 16/36 (44%) | |

| Grade-III | 21/35 (60%) | 17/36 (47%) | |

| Grade-IV | 1/35 (3%) | 1/36 (3%) |

All the patients in our study had sleep-related complaints, which were most common in adenoid enlargement affecting 56.3% of the patients, closely followed by nasal complaints. The least common complaints were personal life-related complaints, affecting 18.3%. Pre-operative endoscopy showed grade III adenoid enlargement (53.5%), followed by grade II, and grade I. Grade IV enlargement was noted in the least number of patients (Table 1).

Following conventional adenoidectomy, group B intra-operatively check endoscopy revealed 26 (66.7%)patients with no residual adenoids while eight patients (22.2%) had grade I and two patients (5.6%)had grade III residual tissue. Completion adenoidectomy was done among those more than grade II in this group. By the 12th postoperative week, fiberoptic endoscopy revealed residual adenoid tissue in 11 patients (39.3%) and three patients (8.8%) in the conventional and endoscopic assisted group respectively (Fig. 1). This was statistically significant (p-value = 0.03, Table 2). Among the patients having residual adenoid tissue at 12 weeks, in the conventional group, seven patients had grade I and four had grade II with none having grade III or more while in the endoscopic assisted group all three with grade I.

Table 2.

Grade of adenoids at 12 weeks post-operative

| Allocation | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Endoscopic | ||||

| Follow up Grade(16) | 0 | Count | 17 | 31 | 48 |

| % within Allocation | 60.7% | 91.2% | 77.4% | ||

| 1 | Count | 7 | 3 | 10 | |

| % within Allocation | 25.0% | 8.8% | 16.1% | ||

| 2 | Count | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| % within Allocation | 14.3% | 0.0% | 6.5% | ||

| Total | Count | 28 | 34 | 62 | |

| % within Allocation | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| P Value = 0.003 | |||||

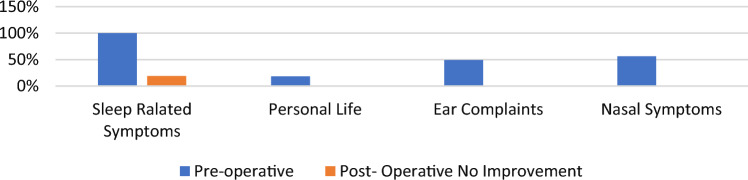

All symptoms except the sleep-related ones showed improvement in both groups post-operatively (Table 3). On analyzing it was noted that at 6th postoperative week, persistent sleep-related symptoms were noted in eight patients (22.6%)of conventional and in only one (2.8%) patient of endoscopy assisted group (Fig. 2). This was statistically significant. By 12th postoperative week, no improvement was noted in nine patients (25%) and five patients (14.7%) of conventional and endoscopy-assisted groups respectively. This was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Primary outcome symptoms

| Improvement in Parameters | Conventional | Endoscopic | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sleep symptoms—6th week | 24/31 | 35/36 | 0.02 |

| Sleep symptoms—12th week** | 21/28 | 29/34 | 0.35 | |

| 2 | School Symptoms—6th week | 4/31 | 8/36 | 0.36 |

| School Symptoms—12th week* | 4/28 | 8/34 | 0.52 | |

| 3 | Ear Symptoms—6th week | 10/31 | 9/36 | 0.59 |

| Ear Symptoms—12th week* | 10/28 | 8/34 | 0.40 | |

| 4 | Nasal Symptoms—6th week | 19/31 | 18/36 | 0.46 |

| Nasal symptoms—12th week* | 18/28 | 17/34 | 0.31 |

*All patients had postoperative full recovery of symptoms. **Sleep symptoms persisted in both the groups

Fig. 2.

Symptoms incidence—preoperatively and post operatively

Discussion

Since the advent of nasal endoscope, conventional blind curettage adenoidectomy has been debated as the former has the advantage of being done under direct vision with reduced risk of nasopharyngeal injury and incomplete removal of adenoid tissue [2, 7]. However, there are conflicting reports between conventional and endoscopic powered adenoidectomy with no significant difference in postop pain or complications [8, 9, 12]. Greater blood loss was reported in the micro-debridor group than in conventional and acoblator group revealed reduction in the mean blood loss [9, 10]. Besides, a meta-analysis of available seven randomized controlled trials ofendoscopic assisted adenoidectomy versus conventional curettage adenoidectomy, revealed that former had advantages over latter with regard to total operative time, blood loss, and complications [5].

Our study of 71 patients undergoing conventional versus endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy revealed that all the patients had sleep-related complaints, which were most common (56.3%), closely followed by nasal symptoms. This was similar to a report with consecutive admissions of 1735 for adenoidectomy and/or tonsillectomy among patients aged 4 years to 197 months where a majority of patients (61.4%) had sleep-disordered breathing or sleep apnea [16]. There were no complications in our study of children who were three and more years of age. Age, medical history, and physical condition are revealed to be major statistically significant risk factors for a serious critical event [17]. It has been suggested that children three years old and younger be managed in tertiary care centers by anesthesiologists with pediatric training [18]. Besides, prolonged use of general anesthetics has been reported with increased risk of perioperative complications among children less than three years old with obstructive sleep apnea and other comorbidities. A warning weighing the risk versus benefits of proceeding with surgical procedures among these patients has also been issued by FDA [19].

In our patient series following the conventional method, as evidenced by on-table endoscopy, though immediate intra-operative findings residual adenoids of more than grade II were noted in around 5.6% they regressed to grade I or II as evidenced by 12th postoperative week endoscopy. Unlike ours, adenoid regrowth following coblation was around 13.3% [20]. Majority of our patients had grade III adenoid enlargement preoperatively. By the 12th post-operative week, it was noted none more than grade II in either group. Both the groups had total recovery of all preoperative symptoms except sleep-related (25% versus 14.7%), the difference being statistically not significant. Similar to our study, a recent prospective post-adenoidectomy study questionnaire for quality of life OSA-18 from post-op day one to 90 days revealed no statistically significant differences between the three techniques (conventional 'blind' curettage, video-assisted with microdebrider and video-assisted with coblator), supporting that conventional blind curettage technique, besides having the shortest duration, it is yet to be surpassed in relief of clinical symptomatology [21]. Recent studies also revealed that in the case of grade 1 V adenoid enlargement residual tissue in the nasal choana among children undergoing conventional adenoidectomy occurs due inability of the curette to reach these regions [22]. Post-curettage visualization of the choana to be considered among those more than grade III adenoid enlargement.

Conclusion

This randomized controlled study revealed that sleep-related symptoms in adenoid hypertrophy can persist following adenoidectomy by either conventional or endoscopic assisted methods. Relief of all other symptoms of adenoid hypertrophy was achieved despite grade I or II residual adenoids suggesting ‘anatomical success’ is not necessary for ‘clinical success’. It also suggests surgical intervention to consider for those children with more than grade II adenoid enlargement. Conservatitove curettage adenoidectomy is comparable to endoscopic assisted non-powered adenoidectomy in children above three years of age in terms of ‘clinical success’ and can still be considered the standard of care, especially in resource-strained countries. However, if endoscopes are available, an adenoid curette to be applied under vision, for precise efficient adenoidectomy including for postgraduate training.

Acknowledgements

To the department of ENT of PIMS and the Research committee of our institution.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical Approval

This study was passed through the Institutional Ethical Committee before initiating and was approved. All ethical standards were followed till the completion of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thornval A. Wilhelm Meyer and the adenoids. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;90(3):383–386. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1969.00770030385023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robb PJ. The adenoid and adenoidectomy. In: Watkinson J, Clarke R, editors. Scott-Brown's otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery. 8. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2019. pp. 285–2904. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawal J, Dadi HI, Sanni R, Shofoluwe NA. Prevalence of revision adenoidectomy in a tertiary otorhinolaryngology centre in Nigeria. J West AfrColl Surg. 2021;11(1):23–28. doi: 10.4103/jwas.jwas_61_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CH, Hsu WC, Ko JY, Yeh TH, Lin MT, Kang KT. Revision adenoidectomy in children: a meta-analysis. Rhinology. 2019;57(6):411–419. doi: 10.4193/Rhin19.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L, Shan Y, Wang S, Cai C, Zhang H. Endoscopic assisted adenoidectomy versus conventional curettage adenoidectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Springerplus. 2016;11(5):426. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhandari N, Don DM, Koempel JA. The incidence of revision adenoidectomy: a comparison of four surgical techniques over a 10-year period. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97(6):E5–E9. doi: 10.1177/014556131809700601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadia J, Dabholkar Y. Comparison of conventional curettage adenoidectomy versus endoscopic powered adenoidectomy: a randomised single-blind study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl 2):1044–1049. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-02122-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hapalia VB, Panchal AJ, Kumar R, Kapadia PB, Bhiryani MA, Verma RB, Parmar ND. Pediatric adenoidectomy: a comparative study between cold curettage and coblation technique. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl 2):1163–1168. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-02247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juneja R, Meher R, Raj A, Rathore P, Wadhwa V, Arora N. Endoscopic assisted powered adenoidectomy versus conventional adenoidectomy - a randomised controlled trial. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;133(4):289–293. doi: 10.1017/S0022215119000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bidaye R, Vaid N, Desarda K. Comparative analysis of conventional cold curettage versus endoscopic assisted coblation adenoidectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;133(4):294–299. doi: 10.1017/S0022215119000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di RienzoBusinco L, Angelone AM, Mattei A, Ventura L, Lauriello M. Paediatric adenoidectomy: endoscopic coblation technique compared to cold curettage. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32(2):124–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elzayat S, Elsherif H, Aouf M. Trans-oral endoscopic assisted radio-frequency for adenoid ablation; a randomized prospective comparative clinical study. AurisNasus Larynx. 2021;48(4):710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Söderman AC, Odhagen E, Ericsson E, Hemlin C, Hultcrantz E, Sunnergren O, Stalfors J. Post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage rates are related to technique for dissection and for haemostasis. An analysis of 15734 patients in the National Tonsil Surgery Register in Sweden. ClinOtolaryngol. 2015;40(3):248–254. doi: 10.1111/coa.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabriel OT, Oyebanji O. A review and outcome of adenoidectomy performed in resource limited settings. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;71(Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12070-014-0789-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassano P, Gelardi M, Cassano M, Fiorella ML, Fiorella R. Adenoid tissue rhinopharyngeal obstruction grading based on fiber-endoscopic findings: a novel approach to therapeutic management. Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol. 2003;67(12):1303–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habre W, Disma N, Virag K. Incidence of severe critical events in paediatric anaesthesia (APRICOT): a prospective multicentre observational study in 261 hospitals in Europe. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:412–425. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murat I, Constant I, Maud’huy H. Perioperative anaesthetic morbidity in children: a database of 24,165 anaesthetics over a 30-month period. PaediatrAnaesth. 2004;14(2):158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGuire SR, Doyle NM. Update on the safety of anesthesia in young children presenting for adenotonsillectomy. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;7(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Aziz M, Nassar A, Nashed R, et al. The benefits of endoscopic look after curettage adenoidectomy. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2020;36:26. doi: 10.1186/s43163-020-00027-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SY, Lee W-H, Rhee C-S, Lee CH, Kim J-W. Regrowth of the adenoids after coblation adenoidectomy: cephalometric analysis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(10):2567–2572. doi: 10.1002/lary.23984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreira MS, Mangussi-Gomes J, Ximendes R, Evangelista AR, Miranda EL, Garcia LB, Stamm AC. Comparison of three different adenoidectomy techniques in children - has the conventional technique been surpassed? Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol. 2018;104:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das AT, Prakash SB, Priyadarshini V. Combined conventional and endoscopic microdebrider-assisted adenoidectomy: a tertiary centre experience. J ClinDiagn Res. 2017;11(2):MC05–MC07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24682.9394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]