Abstract

Retinopathy of prematurity is a complex neonatal disorder with multiple contributing factors. In this paper we have mounted the evidence in support of the proposal that neonatal sepsis meets all requirements for being a cause of ROP (not a condition, mechanism, or even innocent bystander) by means of initiating the early stages of the pathomechanism of ROP occurrence, systemic inflammation. We use the model of etiological explanation, which distinguishes between two overlapping processes in ROP causation. It can be shown that sepsis can initiate the early stages of the pathomechanism via systemic inflammation (causation process) and that systemic inflammation can contribute to growth factor aberrations and the retinal characteristics of ROP (disease process). The combined combination of these factors with immaturity at birth (as intrinsic risk modifier) and prenatal inflammation (as extrinsic facilitator) seems to provide a cogent functional framework of ROP occurrence. Finally, we have applied the Bradford Hill heuristics to the available evidence. Taken together, the above suggests that neonatal sepsis is a causal initiator of ROP.

Keywords: Prematurity, newborn, sepsis, retinopathy, infection, inflammation

1. Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity is a neonatal disorder of the retina frequently associated with visual limitations in childhood and, in a few cases, blindness. Over the past two decades one of the authors (OD) has worked on the clinical epidemiology of ROP (Chen et al., 2011a; Chen et al., 2010; Dammann, 2010; Dammann et al., 2009; Dammann and Leviton, 2006; Dammann et al., 2021b; Holm et al., 2017; Ingvaldsen et al., 2021; Lee and Dammann, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Morken et al., 2019; Rivera et al., 2017). Since his main interest is in ROP causation and explanation, he has also published in the philosophy of science literature (Dammann, 2017, 2020; Dammann 2021; Dammann et al., 2020; Dammann and Smart, 2019). In this paper, we bring these two lines of research together. Our goal is to mount evidence in support of the overarching hypothesis that oxygen is not the only cause of ROP. More specifically, our main claim is thatneonatal sepsis, particularly late onset sepsis is an oxygen-independent cause of ROP and not simply a clinical risk factor for ROP. An expanding notion of causal factors for ROP will inevitably expand potential interventions targeting oxygen exposure AND interventions focused on neonatal sepsis and the associated systemic inflammatory response with the goal of reducing the disease burden associated with ROP.

In the next section (§2), we will first briefly introduce ROP, neonatal sepsis, the idea of a “risk factor”, and the central hypothesis of this paper. We will then move to the theoretical concepts (§3) of etiological explanation and combined contribution. Those readers who are mainly interested in the biological component of our argument can skip §3 and move on to a more detailed exposition of the main argument, which we support by contrasting the current “standard model of ROP” centered on oxygen (§4) with our suggested causal “infection → inflammation → ROP” model (§5). In §6 we will apply “Hill’s viewpoints”, a standard epidemiological tool for causal inference rooted in explanatory-coherentist reasoning, to the etiologic rationale for the new ROP causal model. The last section (§7) offers a summary and conclusion.

2. Background

2.1. Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a neurovascular disorder of the retina and associated visual structures (Dammann et al., 2022; Hartnett, 2015; Hellstrom et al., 2013) that occurs primarily in two overlapping populations. First, ROP is a disease of extremely premature infants born in high-income countries with state-of-the-art neonatal care. The second high-risk population are moderately preterm (ie. > 32 weeks) newborns born in middle- and low-income countries with more limited resources (Azad et al., 2020; Padhi et al., 2014; Quinn, 2016; Ratra et al., 2017; Shah et al., 2012). In both populations, excessive exposure to exogenous oxygen is considered the main causal driver of ROP occurrence and severity.

In its most severe form, ROP is sight-threatening and may lead to blindness, and effective screening and early intervention are needed to mitigate the most advanced forms of ROP (termed Type 1 ROP). Upon recognition of severe ROP, treatment options (ie. secondary prevention) include laser ablation and intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents (VanderVeen and Cataltepe, 2019). Both interventions are invasive and are not entirely efficacious; thus, primary prevention of ROP (reducing its incidence) remains an important goal. A critical component of primary prevention is identifying all etiological factors (causes) of ROP.

2.2. Neonatal sepsis

Sepsis occurs in up to 1 in 10 newborns worldwide and accounts for 15% of all neonatal deaths (WHO, 2020). In a comprehensive analysis of 26 articles accounting for almost 3 million live births, investigators calculated 2,824 sepsis cases per 100,000 live births with an estimated mortality over 17% (Fleischmann et al., 2021). While the specific clinical and diagnostic criteria required to identify neonatal sepsis remain poorly defined, sepsis is characterized as a “systemic infection that prompts a cascade of often fatal inflammatory immune responses” (Coggins and Glaser, 2022). The high rate of “culture-negative sepsis” in newborns where a causal pathogen is not firmly established further hampers the identification of newborns with sepsis. In fact, for every newborn with pathogen-positive sepsis, as many as 16 neonates will receive antimicrobial therapy without a specific pathogen identified (Klingenberg et al., 2018). The ratio approaches 1:6 when preterm infants are included in the dataset.

Neonatal sepsis is divided into early onset sepsis (EOS) when occurring within the first 72 hours after birth and late onset sepsis (LOS) when occurring between 72 hours and 6 months of life (Hayes et al., 2021). This division is largely driven by variation of pathogen prevalence, mode of transmission, and diagnostic and management decisions. EOS is dominated by group B streptococcus (GBS) transmission from mother to infant for which long-standing guidelines are in place for GBS surveillance among pregnant women and transmission is highly preventable. Among preterm neonates, the risk for EOS (~13%) is considerably higher than in term infants (~0.04 – 0.08%) (Cailes et al., 2018) and sepsis prevalence decreases over time for both preterm and term infants. Both EOS and LOS have been identified as risk factors for ROP (Huang et al., 2019), but the weighted contribution of each sepsis window to ROP risk remains unclear.

We hold that the causal relationship between LOS and ROP, is mediated by the systemic inflammatory response to one or several pathogens and the subsequent multi-organ dysfunction (Dammann and Leviton, 2014). For the time being, we consider the systemic mediators of inflammation during neonatal sepsis, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and free radicals, to be likely mediators between infection and ROP by interfering with normal retinal vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.

2.3. Risk factors, causal inference, and ROP occurrence

ROP is a disease of preterm survivors. Thus, the trend of increased survival among extremely low birth weight infants (< 1,000 g) is likely to beget an increase in the incidence and severity of ROP (Painter et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2015). The growing survival of so-called “micropremies” with gestational ages below 24-weeks at birth in high resource settings coupled with the strong inverse relationship between ROP incidence/severity and gestational age allows for the inference that the population at highest risk for ROP is growing.

The search for causes of illness begins with epidemiological risk factor studies. A host of risk factors for ROP have been identified beyond oxygen, including intrauterine growth restriction (Chu et al., 2020), low birthweight (Lundgren et al., 2014), being small for gestational age (Fortes Filho et al., 2009), surfactant administration (Termote et al., 1994), poor postnatal weight gain (Wallace et al., 2000), ethnicity (Aralikatti et al., 2010), hyperglycemia (Mohamed et al., 2013), sepsis (Tolsma et al., 2011), blood transfusions (Chalmers et al., 2020), and maternal conditions such as the usage of reproductive technologies (Trifonova et al., 2018), chorioamnionitis (Mitra et al., 2014), diagnosis of preeclampsia (Shulman et al., 2017), iron deficiency (Dai et al., 2015) and/or diabetes (Opara et al., 2020), and maternal smoking (Hudalla et al., 2021). Each of these risk factors may drive ROP.

However, most publications refrain from making the leap from risk factors associated with ROP to causes of ROP. For example, in the most comprehensive review of risk factors for ROP to date, Kim and colleagues use the term “cause” to refer to the relationship 1) between ROP and blindness, 2) between ROP examination and morbidity, 3) between missing ROP during screening and its consequences, 4) between the causes of preterm birth and ROP, and 5) between surfactant deficiency and respiratory distress syndrome, but the authors withhold using the term “cause” to describe any relationship between risk factors and ROP (Kim et al., 2018).

The authors (and others) may hesitate to draw this conclusion for several reasons. First, they believe in the monocausal explanation of ROP, and that the sole cause is oxygen. Another reason might be that other risk factors lack a plausible mechanism to connect cause and effect. And yet another reason might be the strong belief that “correlation is not causation” and that non-randomized, observational risk factor studies of ROP lack sufficient grounding to determine cause and effect.

According to the National Cancer Institute1, a “risk factor” is “something than increases the chance of developing a disease”. This definition needs disambiguation in at least one way. Calling any characteristic a “risk factor” requires demonstration that the chance of developing disease is higher among individuals with the risk factor than among individuals without the risk factor. However, this can only be ascertained using statistical approaches because “chance” and “risk” are quantitative concepts, at least in our current context. Risk analyses require large studies that include many individuals with and without the purported risk factor, which earns the moniker “risk factor” only if it is statistically associated with the disease in multivariable models that adjust for confounders.

Technically speaking, a risk factor is “something that is associated with an increased chance of disease” and not “something that increases the chance of developing a disease”. The former is observable in studies and the latter is an inference about the future based on available data. While the NCI definition appears to require a risk factor to increase the likelihood of disease prospectively (the disease has not yet occurred), our definition simply refers to available data from the past (disease has occurred and we can compare its prevalence or incidence among individuals with and without the risk factor).

One additional point is crucial: risk factors are not causes simply because they are first and foremost statistical associations. Theoretical (Hill, 1965) and mathematical (Hernán and Robins, 2006) tools are available to facilitate the move from a statistical risk factor to a causal factor. One of the few definitions of “cause” offered by health scientists is Mervyn Susser’s who defined a cause as “something” that makes a difference in the outcome rather than simply being statistically associated with an outcome (Susser, 1991).

Naturally, the question arises how to distinguish between risk factors that are associated with ROP and factors that are causally involved in its occurrence? Among the methods that are supposed to help distinguish between the two categories is confounder adjustment in multivariable risk analyses, propensity score adjustment or matching, target trial emulation, and Mendelian randomization. Of note, all of these are statistical methods that still rely on associations. The ingredient that reveals an association is causal rather than merely statistical does not come directly from the data, but from the study design (e.g., randomization) and analysis (e.g., rearrangement of observational data as a “target trial”). However, some are not entirely convinced that causal information can be extracted from statistical data; as philosopher of science Nancy Cartwright recognized many years ago, “No causes in, no causes out” (Cartwright, 1994).

The other method familiar to epidemiologists is “explanatory coherence analysis” (ECA). In the most frequently cited method paper on ECA, the author describes the process for evaluating a causal hypotheses from data generated by observational studies (Hill, 1965). In essence, the method suggests nine viewpoints that make causation a better explanation for the observed effect than a mere association. These viewpoints are temporality, strength of association, consistency of association, specificity of association, biological gradient, experiment, plausibility, coherence, and analogy. We will use this method to examine the evidence in support of a causal role for sepsis in ROP occurrence in §6.

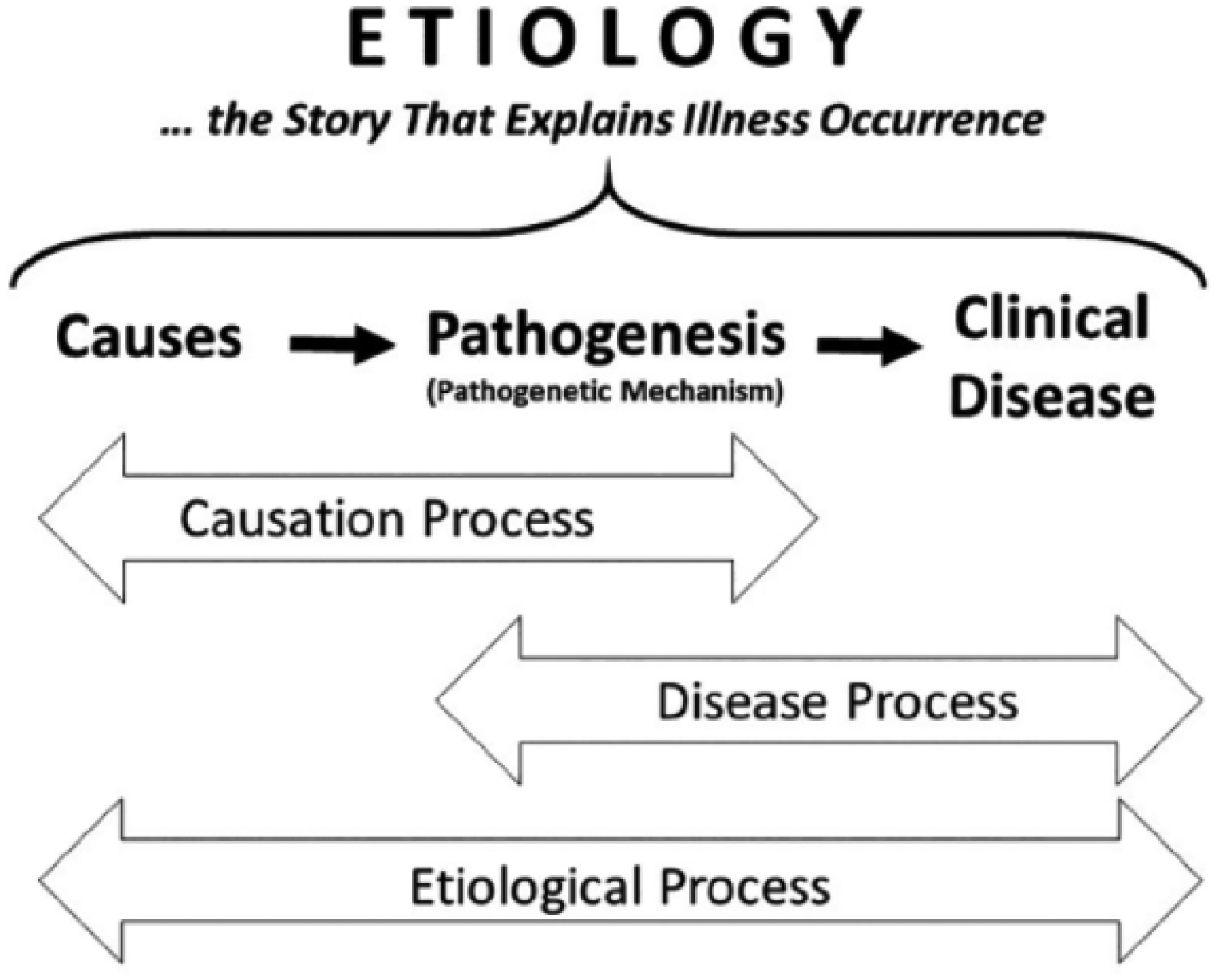

Still, a cause is usually taken to be a factor that induces an effect by means of a mechanism. To explain the occurrence of a disease using both causal and mechanical evidence (Fig. 1) is what we have termed “etiological explanations” (Dammann, 2020), borrowing the term from Salmon (Salmon, 1984), who in turn borrowed it from Wright (Wright, 1976). We will offer more detail about etiological explanations in §3.1.

Figure 1.

The concept of “etiological explanation” holds that the term “etiology” (causal history) includes the entire process of disease occurrence, i.e., the etiological process. The etiological process consists of two overlapping sub-processes, i.e., the causation process and the disease process. While the causation process includes causes and the pathomechanism that connects causes with disease, the disease process includes the (subclinical) pathomechanism and the (clinical) disease from start (very first signs or symptoms) to finish (recovery or death). Reprinted from (Dammann, 2017), with permission.

Indeed, it is important to ask how risk factors contribute to ROP occurrence. What causal function do risk factors have in ROP causation? While all the risk factors for ROP may be associated with ROP in multivariable analyses, they are unlikely to have the same initiating and/or productive function in ROP etiopathogenesis as oxygen. In keeping with the model for etiological explanations, clarifying whether each “risk factor” is a cause (initiator) of ROP or lies in the causal pathway of ROP or is an innocent bystander that happens to be associated with both the causal factor and ROP is critical to differentiating causal factors from risk factors. One way of doing this is to think about what functional role a risk factor might play in the multivariable process leading to ROP. We have called this approach combined contribution (Dammann, 2017) in which risk factors of a disease are categorized by how they functionally contribute to illness occurrence (see § 3.2).

2.4. Etiology of the central hypothesis

The central hypothesis defended in this paper has been a long way coming. The idea that neonatal sepsis might be a cause of ROP is a product of our work on systemic inflammation as a potential mechanism that connects intrauterine infection with neonatal white matter abnormalities (Dammann and Leviton, 1997, 1998). As a conceptual analogy, we first reviewed the information available in 2006 (Dammann and Leviton, 2006) and 2010 (Dammann, 2010) that supported the contention that a similar relationship might exist between perinatal infection, systemic inflammation, and ROP. Based on this rationale, we also suggested that there might be a “pre-phase” of ROP during the prenatal period that influences the occurrence and/or severity of the two postnatal phases of ROP (Dammann et al., 2021b; Hellstrom et al., 2013; Lee and Dammann, 2012).

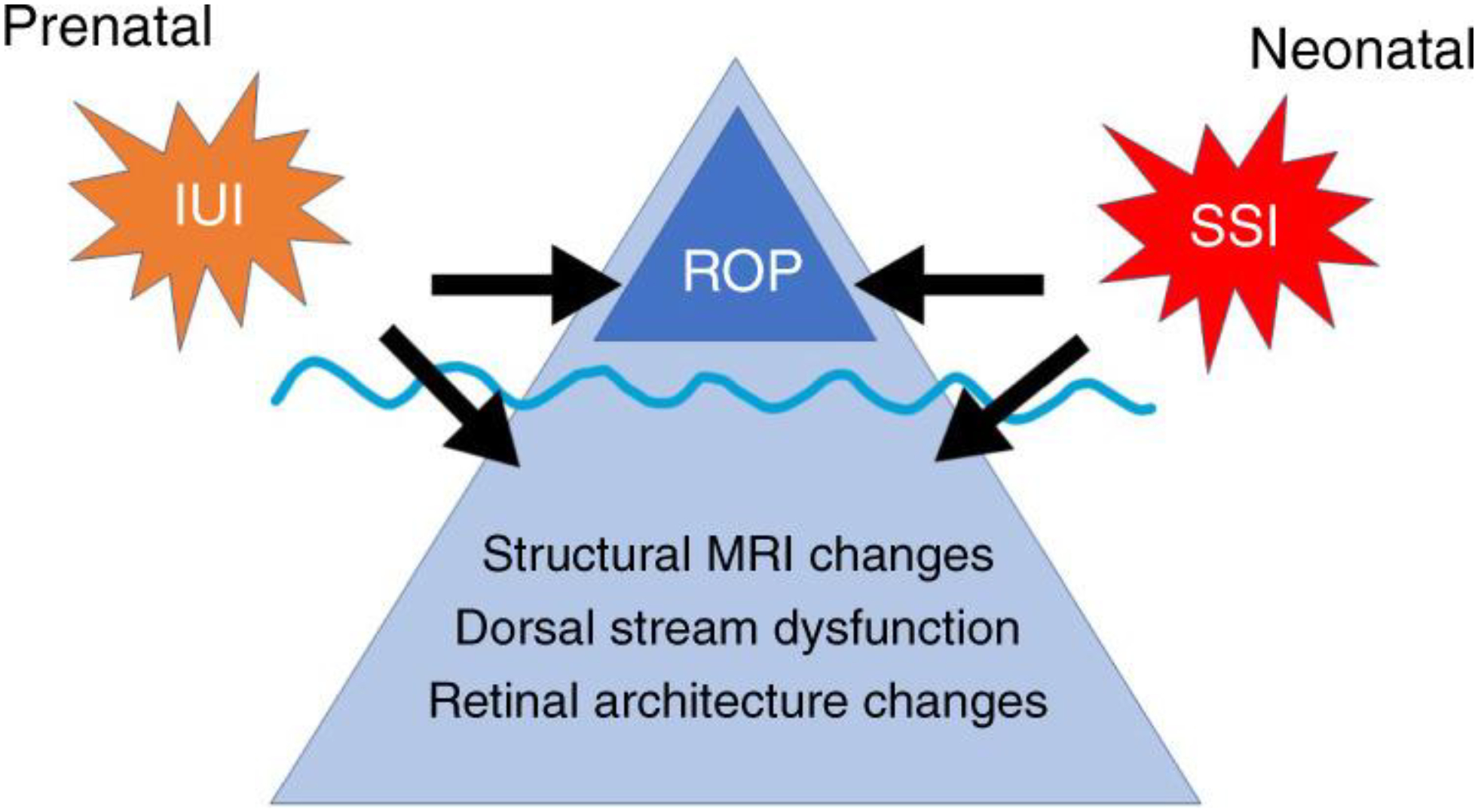

Using this overarching theoretical framework, we then undertook clinical epidemiologic analyses using the data from the ELGAN (Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborn) study (Dammann et al., 2021a) and identified associations between placental infection/inflammation and ROP (Chen et al., 2011a) and between neonatal systemic inflammation and ROP (Holm et al., 2017). As part of that work, we suggested that ROP should not just be considered a disease of the retina but one that also includes choroidal degeneration (Rivera et al., 2017) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The proposal of “visuopathy of prematurity” is that both prenatal intrauterine infection and inflammation (IUI) as well as neonatal sustained systemic inflammation (SSI) may contribute to the etiology of both retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) as well as long-term abnormal visual outcomes (AVO) such as structural changes visible on magnetic resonance images, dorsal stream dysfunction, and retinal architecture changes. Reprinted from (Ingvaldsen et al., 2021); with permission.

Finally, we expanded our framework to include long-term abnormal visual outcomes (AVO) (Ingvaldsen et al., 2021). Our suggestion is that both intrauterine infection and inflammation (IUI) as well as neonatal intermittent or sustained systemic inflammation (ISSI) may contribute to the etiology of both ROP and AVO, such as structural changes visible on magnetic resonance images, dorsal stream dysfunction, and retinal architecture changes (Morken et al., 2019). In order to redirect perinatal researchers’ gaze from “just ROP” to “beyond ROP”, we proposed a new entity termed “visuopathy of prematurity”, which encompasses the pre- and post-natal exposures with both ROP and AVOs (Fig. 2) (Ingvaldsen et al., 2021). A large, multi-center ROP-focused cohort study is needed (and in planning) that will allow us to test this hypothesis in a large dataset of preterm newborns.

We will now briefly introduce causation and causal inference with a focus on etiological explanation and combined contribution.

3. Etiological Explanation and Combined Contribution

3.1. Etiological Explanation

Causation and causal inference are central to disease etiology research (Hernán, 2004; Susser, 1991). Over the past two decades or so, one of us (OD) has divided his time between epidemiologic research (Chen et al., 2011a; Chen et al., 2010; Dammann, 2010; Dammann et al., 2009; Dammann and Leviton, 2006; Dammann et al., 2021b; Holm et al., 2017; Ingvaldsen et al., 2021; Lee and Dammann, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Morken et al., 2019; Rivera et al., 2017) and the philosophy of causation and explanation (Dammann, 2017, 2020; Dammann 2021; Dammann et al., 2020; Dammann and Smart, 2019) with the overarching goal to elucidate the causation of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

Two main aspects of this work are relevant for this paper: first, the “etiological stance” (Dammann, 2017) as the broad structure of etiological explanations (Dammann, 2020), the topic of the remainder of this section. Second, the use of the classic qualitative causal method in epidemiology, the “Hill viewpoints” (Hill, 1965), as a heuristic for causal inference (Dammann, 2018). This causal model is based on the framework of explanatory coherence as championed by Ted Poston (Poston, 2014) and will be applied to the hypothesis that neonatal sepsis is a cause of ROP in the last section of this paper.

From a philosophical viewpoint, causation cannot be proven. Douglas Weed gives three reasons (Weed, 2008). First, an event cannot be witnessed twice, once with and once without the cause. Thus, we cannot directly conclude whether the effect would have occurred in the absence of the cause. Second, available evidence of the cause-effect relationship selects a limited number of choices among all possible causes in a particular causal relationship. Third, causation cannot be witnessed. The purported cause and effect can be measured, but the mechanism linking cause and effect cannot be directly observed.

What kind of support do scientists use to support causal claims? In the laboratory, sound experiments require that all conditions for two experimental groups are identical except for the variable (ie. cause) to be tested. One group is exposed to the cause, the other experiences all of the same conditions except the cause. If the resulting outcome differs between the two groups and the outcome difference is unlikely to have occurred by mere chance, the causal hypothesis is accepted. This is a bit more complicated in human studies (such as risk factor studies of ROP) simply because risk factors cannot be administered experimentally for obvious ethical reasons and the comparison groups are never completely, and sometimes not even remotely identical.

While the randomized controlled trial (RCT) approaches this ideal, inferences must be made to account for natural variation in complex organisms. Randomized trials are considered the gold standard in medicine for two reasons. First, randomization is supposed to render the groups of study participants to be compared statistically similar so that all potential confounders, known and unknown, are distributed evenly across all groups. An ideal RCT yields a causal relationship if the intervention is associated with a statistically significant difference in the effect. Unfortunately, this gold standard is not without its limits. First, investigators select the likelihood of the observed result (or a more extreme one) occurring in the absence of a causal association between the exposure and outcome. This likelihood is often set at 0.05, but it is never zero. In other words, RCTs cannot confirm a “true” causal relationship just because they are randomized.

Second, the intervention process also contributes to the causal interpretability of RCTs. Consider the following thought experiment. A randomized trial where participants randomized into group A are given a new drug and all participants randomized into group B are given a placebo. The result is impressive: 80% of the new drug recipients and only 20% of the placebo recipients experience the measured outcome and this difference reaches statistical significance at p=0.02. Now reconsider the same study with the same group randomization. Now, participants are offered both the new drug and placebo in a concealed manner. By chance, all participants in group A pick the new drug and all participants in group B pick the placebo. The result for each group is identical with 80% in group A and 20% in group B experiencing the measured outcome with the same statistical significance at p=0.02. The only difference between the two scenarios is that the exposure (new drug or placebo) was controlled by the investigator by virtue of being an intervention, while the exposure was self-selected by the blinded participants in the second study. Some appear to consider the first scenario stronger evidence for a causal role of than the second scenario. In general, RCTs are strong evidence in support of causal claims because they are randomized and because the exposure is controlled via intervention (manipulation) (La Caze, 2013).

Prevention of a disease such as ROP requires the ability to explain its etiology (causal origin) and pathogenesis (disease mechanism). In medicine, these terms are not well defined. A simple approach is to view etiology as restricted to the cause under study and the mechanism as the linking events between the cause and the effect. Simply put, flipping the light switch is viewed as the cause of the bulb emitting light and the flow of electricity is viewed as the mechanism. This comes close to what Wesley Salmon called a “causal-mechanical explanation”, in which the occurrence of an event is explained by reference to both causes and mechanisms (Salmon, 1984).

However, the processes leading to human disease are almost always more complex than flipping a light switch. To accommodate such complexity, I have previously developed a process framework of “etiological explanations” (Dammann, 2017, 2020). In brief, the term “etiology” (causal history) includes the entire process of disease occurrence, i.e., the etiological process (Figure 1). The etiological process consists of two overlapping sub-processes, i.e., the causation process and the disease process. The causation process includes initiating causes and the mediating mechanism that connects causes with disease. The disease process includes the subclinical mechanism and the clinical disease from the onset of first signs or symptoms to disease resolution or death. The idea is that interfering with the causation process is the goal of primary prevention while interfering with the disease process is the goal of secondary prevention. While the former prevents the initial causal events, the latter interrupts the full manifestation of the disease. Intervention that targets the adverse consequences of the disease is tertiary prevention. Thus, a robust knowledge of the causation and disease processes of ROP will inform intervention options.

3.2. Combined contribution

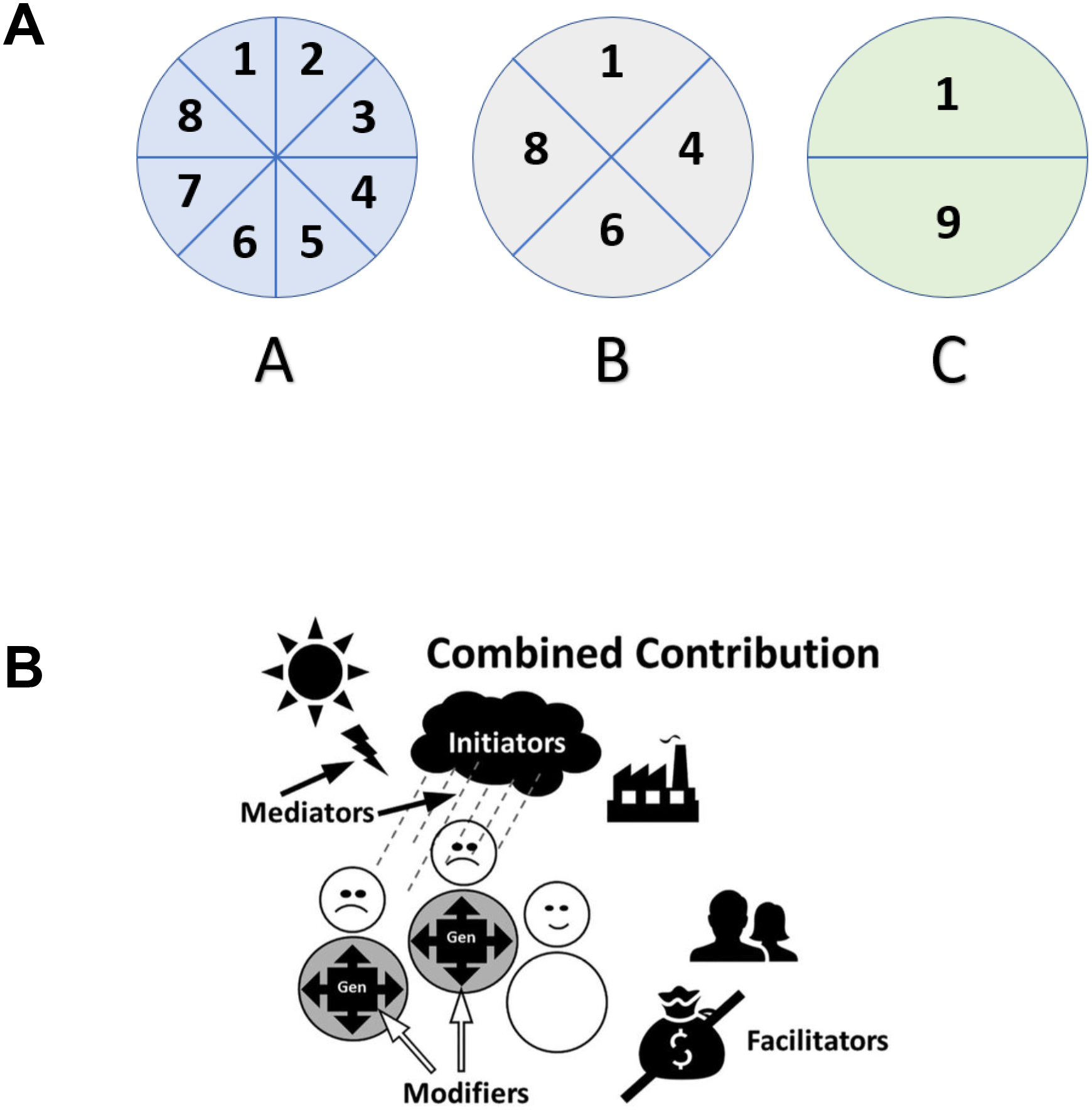

In keeping with John Stuart Mill’s multivariable model of causation (Mill, 1856), and with the view that a “sufficient” cause of any disease includes several “insufficient” component causes (Rothman, 1976)(Fig. 3A), taking a comprehensive and inclusive etiological stance when explaining illness occurrence is likely to be more informative than simply talking about “the cause” of a disease (Dammann, 2017) (Fig. 3B). This approach includes considering combinations of contributing factors as well as stand-alone factors.

Figure 3.

Panel A. Rothman’s sufficient-component cause model (Panel A) posits that all diseases are caused by constellations (A-C) of component causes (1–9) where each constellation is sufficient to cause the disease (Rothman, 1976). Note that all three constellations represent a sufficient cause while only component cause 1 is a necessary cause.

Panel B. “Combined contribution” (Panel B) is a functional extension of Rothmans model. Causal constellations are made up of initiators, mediators, modifiers, and facilitators. See text for explication of visuals. (Reprinted from (Dammann, 2017) with permission)

Rothman’s sufficient-component cause model purports that diseases can have one or more constellations (Fig. 3A, A–C) of component causes (Fig. 3A, 1–9) that are jointly sufficient causes of disease. The model is widely used to visualize how causation is conceptualized in epidemiology using a multivariable view of causation. Further, no single “sufficient causal” constellation is necessary to cause the disease because multiple “sufficient causal” constellations exist. Finally, a component of all “sufficient causal” constellations is considered necessary since the absence of this common component means that all “sufficient causal constellations” are incomplete and the disease will not occur. The use of the word “cause” for both sufficient causes (constellations) and for component causes is an obstacle to using the Rothman model, although both represent different concepts in the causality framework. To distinguish these two levels of causation, the sufficient causal constellations can be referred to as “macro-causes” and the component causes as “micro-causes”.

What the sufficient-component cause model does not specify is how individual component causes contribute to the etiological process. One of us (OD) therefore proposed to consider the combined contribution of several factors with different etiologic and pathogenetic functions (Dammann, 2017). According to this model, component causes can be initiators, mediators, modifiers, and facilitators (Figure 4B). Risk factors can assume one or more of these roles and provide a view of the combined contribution of multiple component causes to the occurrence of disease. Of note, the causal contribution of background conditions is considered a causal factor, albeit some philosophers distinguish between causes and background conditions (Broadbent, 2008).

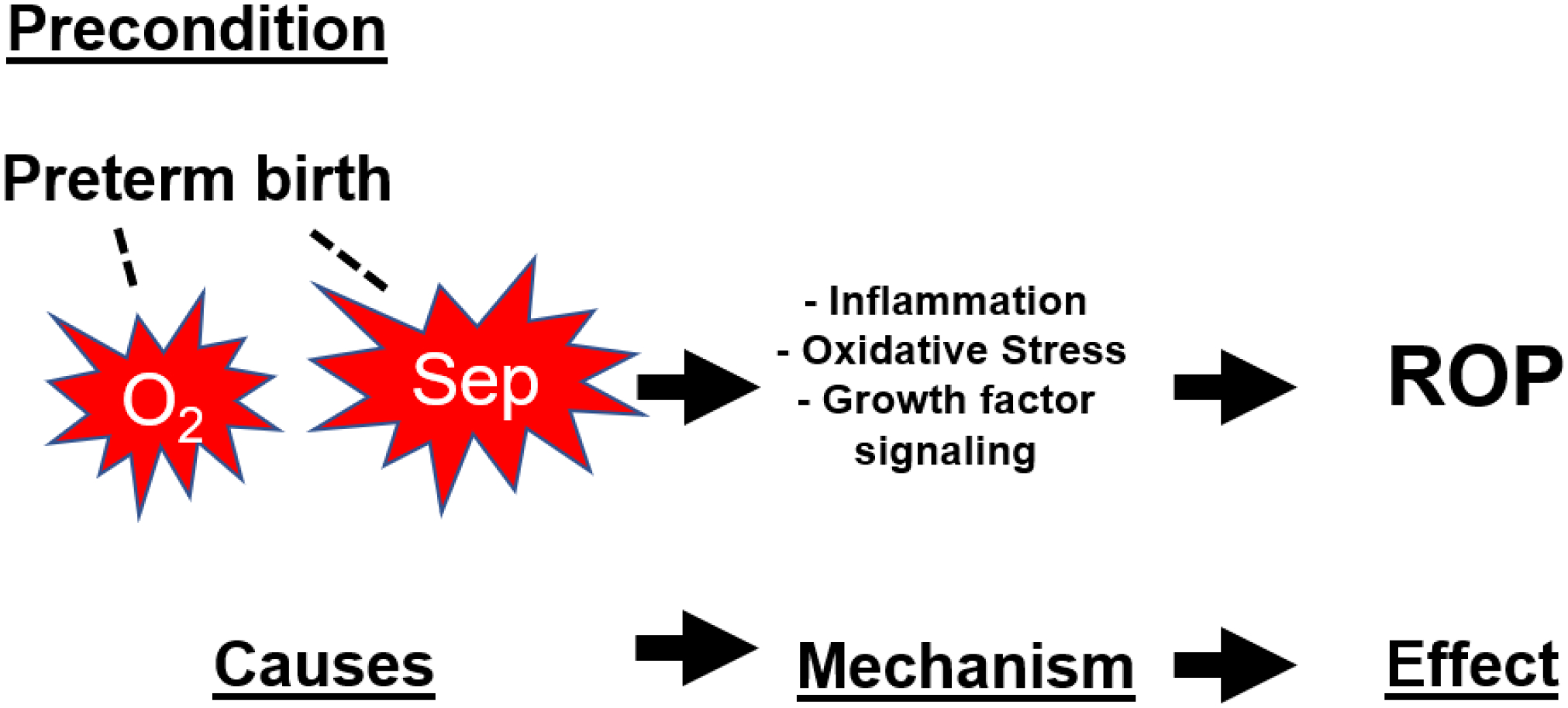

Figure 4.

Etiological explanation for the occurrence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). Preterm birth is a precondition (not a cause) that provides the background before which the etiological process takes place. Associated (dashed line) with preterm birth are the postnatal causes oxygen (O2) and sepsis (Sep) which start the causation process by initiating inflammation/oxidative stress-related growth factor aberrations that represent the pathogenetic mechanism that serves as the biological mediator between cause and effect.

Initiators are component causes that start the etiological process (e.g., the sun, the dark cloud, and the factory in Figure 4B) and are usually referred to as a “root cause” of an event. For our purposes, an initiator is the first step in the etiological process. Currently, exposure to excessive exogenous oxygen is the “initiator” in the standard etiological explanation of ROP. We propose that neonatal sepsis is an “initiator” as well (Fig. 4).

Causal mediators are the mechanisms that connect initiator(s) with the subsequent components of the etiological process. To date, the mechanism (or pathomechanism) of ROP focuses on the oxygen-dependent fluctuations of growth factors, mainly insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which connect oxygen exposure and aberrant vessel formation in the preterm retina (Chen and Smith, 2007; Hartnett, 2015).

Causal modifiers are intrinsic conditions that preexist the “initiator” as a characteristic of an individual (genes in Fig. 3B) and influence the impact of an initiator and/or mechanism. For ROP, developmental immaturity of preterm infants represents an intrinsic condition which makes the retina of preterm infants more vulnerable than the retinas of gestationally older infants (Dammann, 2023).

Causal facilitators are extrinsic conditions that increase or decrease the likelihood of disease occurrence. For ROP, intrauterine exposure to infection that affects the newborn before birth may be considered an extrinsic factor (Dammann et al., 2021b). Similarly, the socioeconomic status of the community or family may be an extrinsic condition that increases or decreases the likelihood of ROP.

We will now move on and apply this conceptual framework to the standard etiological explanation of ROP first with oxygen (§4) and then with neonatal sepsis and inflammation as the causal initiator (§5).

4. The “standard cause” of ROP: Oxygen

4.1. Early observations focused on oxygen

The search for plausible causes of ROP dates back to its discovery in the 1940s. T.L. Terry is frequently quoted as the first author describing what he called “retrolental fibroplasia” (RLF) (Terry, 1942a; Terry, 1942b; Terry, 1944). A decade later some authors continued to ponder “we know nothing about the etiology of the disease and, at present, we have no clue whatsoever to the factor that may cause retrolental fibroplasia” (Blodi and Parke, 1953).

The recognition that the exposure to excessive oxygen played a causal role in ROP surfaced in the early 1950s (Ashton, 1954; Campbell, 1951) with experimental oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) in the kitten supporting these clinical observations (Ashton et al., 1954). In this model, a decrease in oxygen was associated with vessel budding in the retina and into adjacent tissue (Ashton et al., 1954) and intermittent hyperoxia in mice led to pathological signs of RLF, such as retinal folding and detachment (Gyllensten and Hellström, 1952). Neonatologist Bill Silverman retells the fascinating story of early research on RLF in the Scientific American (Silverman, 1977). After V.E. Kinsey and A. Patz received the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award in 19562 “for discovering that excessive oxygen administration is the cause of retinopathy of prematurity in premature babies”, oxygen has held the solo position as the etiologic inducer of ROP in both the laboratory and in clinical epidemiology (Rodriguez et al., 2023).

Dissenting voices surfaced in the early 1980s. Always a critic of simplistic thinking, Bill Silverman referred to the fallacy of assuming that oxygen is the sole cause of ROP when he wrote that “[t]he watertight case in support of ‘hyperoxia is the cause of ROP’ has been leaking for years, the leaks are now so large they can no longer be dismissed” (Silverman, 1982). He doubled down on this position just a few years later with the statement that “[n]othing is so dangerous as an idea – when it’s the only one you have [such as the one that says that] supplemental oxygen is the sole necessary and sufficient cause of all instances of cicatricial retinopathy of prematurity” (Silverman, 1986). In important ways, his warning has gone unheard and our explicit goal is to revisit the possibility that other cause(s) of ROP exist and that sepsis meets the criteria for a causal role in the etiological explanation of ROP.

4.2. Animal models of oxygen-induced retinopathy

The successful development of OIR models in the rat (Ricci, 1990), mouse (Smith et al., 1994), and beagle (McLeod et al., 1996) have cemented the paradigm that exposure to excessive oxygen is the leading cause ROP (Hartnett and Lane, 2013; Higgins, 2019; Saugstad, 2006). In keeping with this reasoning, many past and current preventive efforts have been directed at limiting exposure to exogenous oxygen.

Unfortunately, experimental research models focused on a single cause may yield undesired consequences. As an analogy, consider the introduction of the rat model for neonatal brain injury using hypoxia-ischemia as the causal initiator (Rice et al., 1981). The exclusive focus on hypoxia-ischemia may have diverted investigators’ attention away from other possible causal scenarios. For more than three decades, the idea that perinatal (and even prenatal) infection might induce neonatal brain damage (Gilles et al., 1976; Leviton and Gilles, 1973) remained unexplored in the shadows of “hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy”. Only the recognition of pro-inflammatory cytokines as plausible mechanistic mediators (Dammann and Leviton, 1997; Leviton, 1993) led to the development of experimental models in the rabbit (Debillon et al., 2000) and rat (Cai et al., 2000) that demonstrated the causal potential of infection and inflammation in neonatal brain damage.

We speculate that the exclusive attention given to the OIR model may have delayed investigators from considering other causal paradigms, which have now been developed using lipopolysaccharide in sheep (Loeliger et al., 2011), rats (Hong et al., 2014), and mice (Tremblay et al., 2013) after clinical findings suggested that perinatal infection and systemic inflammation might play a role in ROP as well (Dammann, 2010; Lee and Dammann, 2012).

4.3. The current explanation is centered around oxygen

The standard etiological explanation of ROP refers to a multifactorial sequence of events that begins with preterm birth, which often requires artificial ventilation and oxygen supplementation (Schulzke et al., 2021). Subsequent prolonged administration of exogenous oxygen, maintenance of excessively high oxygen levels, and/or oxygen fluctuations alter the release of angiogenic growth factor patterns for IGF and VEGF (Hartnett and Lane, 2013; Saugstad, 2006). In turn, disturbances in the physiologic quantity and timing of release of angiokines leads to early cessation of retinal vessel growth in phase 1 and a subsequent over-proliferation of vessels in phase 2 of ROP (Chen and Smith, 2007; Hartnett and Penn, 2012). In this etiological explanation, preterm birth is an intrinsic facilitator (precondition) for ROP, exogenous oxygen is the causal initiator, and changes in retinal vascular growth factor patterns play the role of the mediator.

Despite its long history as an etiologic factor in ROP, the clinical association between oxygen and ROP is far from trivial. Oxygen exposure defined by saturation targets (Liu et al., 2022), oxygen fluctuations (McColm et al., 2004), and number of days on oxygen exposure (Estrada et al., 2022), among others, are associated with an increased risk for treatment-requiring ROP. On the other hand, Chen and coworkers failed to identify an association between multiple variables reflecting aggregate oxygen burden and ROP risk beyond the risk associated with low gestational age (Chen et al., 2021).

4.3.1. Preterm birth is a condition for ROP occurrence, not a cause

The current predominant view that low gestational age plays an important role in the etiopathogenesis of ROP is based on decades of evidence pointing to low gestational age as the strongest predictor of ROP (Yu et al., 2022). Indeed, the disease occurs predominantly among infants born at extremely low gestational age (Hong et al., 2021; Quinn et al., 2018), although it still occurs in newborns > 34 wks gestation at birth, which is the initial population that developed RLF (Azad et al., 2020; Padhi et al., 2014; Quinn, 2016; Ratra et al., 2017; Shah et al., 2012).

Low gestational age is considered a risk factor for ROP simply due to the inverse relationship between ROP incidence and gestational age and the observation that preterm infants are at greater risk of ROP than term infants. However, low gestational age in and of itself is actually an indicator of immaturity at birth and immaturity at birth alone is unlikely to be sufficient for ROP or adverse visuomotor outcomes (AVO).

In other words, low GA reflects three entities that are often difficult to distinguish when seeking to understand disease causation: 1) immaturity at birth, 2) causes of preterm birth, and 3) neonatal consequences of preterm birth. Thus, low gestational age is probably better viewed as a background condition for ROP rather than a causal risk factor of ROP. Whether it is an extrinsic (facilitator) or an intrinsic condition (modifier) remains to be clarified. From the perspective of prevention, it is reasonable to assume that that reducing the incidence of preterm birth would lead to less ROP (Kim et al., 2018). However, the preventive mechanism that lowers the incidence of preterm birth would not alter the risk for ROP, rather it would reduce the size of the population at risk.

Further, low gestational age does not cause ROP as many infants born extremely preterm do not develop ROP (Dammann, 2023). In other words, low gestational age is not a necessary component cause for ROP since older infants develop ROP nor is low gestational age a sufficient cause as other components are required for low gestational age infants to develop ROP. Instead, low gestational age is an antecedent of postnatal interventions and events that might be considered causes of ROP (e.g., oxygen exposure and neonatal sepsis; see next sections). In turn, preterm birth is caused by prenatal conditions that might be associated with variable risk for ROP (Lee et al., 2013)

4.3.2. Oxygen is the causal initiator

Among infants born preterm (background condition), excessive exposure to high or volatile oxygen level is viewed as the single causal initiator of the etiological process that culminates in ROP (Rodriguez et al., 2023; Saugstad, 2006). Some authors assert this causal role for oxygen verbatim. For example, Weinberger and colleagues write that “oxygen also induces aberrant physiologic responses that can be damaging in premature infants. For example, vasoconstriction in the retina is an early response to oxygen that can lead to vasoobliteration, neovascularization, and retinal traction (retinopathy of prematurity)” (Weinberger et al., 2002). Claxton and Fruttiger write that “exposure to hyperoxia causes vaso-obliteration of capillaries in the retinal center” (Claxton and Fruttiger, 2003). This notion is not necessarily wrong, but it is clear that oxygen is viewed as the initiator of the causation process, not as a secondary contributor to ROP risk.

4.3.3. Growth factors are the mechanistic mediators

Oxygen saturation controls a functional network of growth factors including insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1alpha), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), placental growth factor-1 (PlGF-1) among many others. This network, in turn, regulates growth and cessation retinal blood vessel (Hartnett and Lane, 2013; Saugstad, 2006). Oxygen-induced growth factor imbalance is seen as the main pathogenetic mechanism of ROP (Chen and Smith, 2007; Hartnett, 2015).

5. Sepsis and ROP: Combined Contribution

There is no question that exposure to excessive and/or fluctuating oxygen levels play a causal role in the natural history of ROP. But why should oxygen be the only cause? We echo the questions that Silverman asked in 1982 (Silverman, 1982): Why does ROP occur in infants who never received supplemental oxygen? Why are there so many infants with prolonged and volatile oxygen exposure who never develop ROP? Why are there still so many infants with ROP after decades of considerable attention to optimal oxygen saturation targets?

Infection was considered an etiologic factor in the natural history of RLF as early as 1951 (Manschot, 1954). However, these inferences were based on limited observations and not on systematic analyses of larger data sets. By the mid 1980’s, neonatal sepsis was recognized as a risk factor for ROP (Gunn et al., 1980). Even at this point in time, sepsis was significantly associated with ROP in infants who received oxygen during resuscitation indicating an impact of sepsis above and beyond oxygen. In one of the earlier trials designed to assess the effect of Vitamin E supplementation on the occurrence of RLF, sepsis was among the significant risk factors for RLF (Hittner et al., 1981). In the National Collaborative Study on Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Premature Infants, infants with a birthweight <1,750g admitted to one of thirteen participating hospitals were recruited (Purohit et al., 1985). Among those discharged alive, the overall percentage of RLF (using the authors’ term) was 11% in 3,025 surviving infants. Sepsis was one of the significant risk factors in a multivariable analysis.

Contemporaneously, Cats and Tan remarked that identifying a difference in sepsis incidence between infants with ROP and without “has evoked little comment” (Cats and Tan, 1985). To some degree, the sentiment remains true. Apart from scattered studies in which the association between sepsis and ROP was one among many findings and two recent meta-analyses (Huang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019), we have not developed a comprehensive framework for defining the relationship between sepsis and ROP, nor have we clarified how sepsis and oxygen may play related roles in ROP etiology. In the remainder of this section, we provide evidence in support of the notion that sepsis is a cause of ROP.

5.1. Sepsis is associated with ROP

When we previously proposed a role for infection and inflammation in ROP and abnormal visual outcomes (AVO) in preterm infants (Dammann, 2010; Dammann and Leviton, 2006; Rivera et al., 2017), our focus was on the hypothesis that prenatal infection and inflammation might modify the risk for ROP (Hellstrom et al., 2013; Lee and Dammann, 2012) and AVO (Ingvaldsen et al., 2021). However, multiple lines of evidence support the hypothesis that postnatal neonatal sepsis might be a risk factor for ROP in addition to oxygen.

The association between neonatal sepsis and ROP is documented in many studies (Huang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Both bacterial and fungal sepsis are strongly linked to ROP in multivariable risk analyses after adjusting for gestational age and oxygen exposure (Bonafiglia et al., 2022; Huncikova et al., 2023; Manzoni et al., 2006; Tolsma et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2019). This suggests that sepsis might represent a “second hit” in addition to oxygen (Chen et al., 2011b), or perhaps trigger the postnatal phases of ROP without oxygen being involved at all.

The notion that sepsis is a “second cause of ROP” is further supported by our finding that oxygen is a stronger risk factor for ROP in infants born at 23–25 weeks gestation, while sepsis is a stronger risk factor among infants born at 28–29 weeks gestation (Chen et al., 2011b). These observations raise important considerations. Although oxygen and sepsis play a role in both phases of ROP, oxygen might exert a stronger influence on Phase 1 ROP (vessel arrest) than sepsis, while sepsis might have more influence on Phase 2 ROP (neovascularization) than oxygen.

Fungal sepsis emerged as a risk factor for ROP in the 1990s (Kremer et al., 1992; Mittal et al., 1998); however, subsequent studies differ considerably regarding cohort definitions and analytic strategies (Giannantonio et al., 2012; Haroon Parupia and Dhanireddy, 2001; Karlowicz et al., 2000; Manzoni et al., 2006; Noyola et al., 2002; Tadesse et al., 2002). One of the first meta-analyses identified a pooled relative risk estimate (odds ratio) of 3.4 (95% C.I. 2.3 – 5) for any ROP and 4.1 (3.1 – 5.4) for severe ROP (Bharwani and Dhanireddy, 2008). The range of odds ratios for all six studies with any ROP as the outcome was 2 – 10, and the range for the seven studies on severe ROP was 3 – 5.3. These data indicate that exposure to Candida sepsis is associated with a minimum 2-fold increase in risk for ROP and severe ROP, which is very unlikely to be due to chance alone.

The timing of sepsis may impart a variable risk for ROP. In some studies, late onset sepsis (LOS, > 72 hours after birth) appears to be a stronger risk factor for ROP than early onset sepsis (EOS, < 72 hours after birth). In one of our own analyses, the risk for severe ROP (zone 1, prethreshold/threshold, and plus disease) was considerably higher in infants with culture-proven late bacteremia (11%, 21%, and 16%, resp.) than in infants without evidence of bacteremia (5%, 11%, 8%) (Tolsma et al., 2011). EOS did not influence the risk for ROP (7%, 17%, 14%) when compared to infants without early bacteremia (8%, 14%, 9%) (Tolsma et al., 2011). In a study that also identified LOS as a risk factor for ROP independent of oxygen and low gestational age, none of the 60 infants with ROP experienced EOS while 3% of those without ROP had a diagnosis of EOS (Manzoni et al., 2006). Finally, a large study comparing 1,597 infants with severe ROP to 10,657 infants with no or mild ROP failed to identify an increase in ROP risk associated with EOS (OR 1.0, 95% C.I. 0.76–1.32) while the exposure to LOS was associated with severe ROP(1.39, 1.26–1.52). The statistical association between LOS and severe ROP persisted after adjusting for confounders including gestational age, but not supplemental oxygen (Goldstein et al., 2019).We consider it plausible to infer that late sepsis preferentially affects the second (neovascular) phase of ROP.

5.2. Combined contribution

According to the model of combined contribution (§3.2) in etiological explanations (§3.1), several factors contribute to ROP synergistically. In this section, we characterize sepsis as the inducing cause, inflammation as the mediator, and growth factor dysregulation as the final common pathway (Fig. 4).

5.2.1. Sepsis as the inducer of ROP

If sepsis can initiate the pathophysiologic process of ROP independent of oxygen, one should expect that (1) preterm infants not exposed to oxygen can develop ROP and (2) exposure to substances mimicking systemic infection such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) should lead to an ROP-like phenotype without oxygen supplementation being involved.

The first contention is supported by early case reports of term infants who developed “fundus changes consistent with retrolental fibroplasia” in the absence of oxygen exposure (Schulman et al., 1980). In an ongoing project using a national neonatal dataset from Norway (2009–19), we identified eight of 228 preterm newborns developed severe ROP despite a total exposure to exogenous oxygen of less than one day (unpublished observation). Despite our own observations and similar evidence from other groups, oxygen has become such a prominent risk factor that published studies rarely include tables that describe oxygen exposure and other pertinent variables.

The second conjecture finds support from animal experiments demonstrating that intraperitoneal injection of LPS during the first five postnatal days leads to systemic inflammation, ROP-like abnormalities (Hong et al., 2014; Tremblay et al., 2013), and reduced retinal function (Tremblay et al., 2013). Systemic administration of LPS increases inflammatory cytokine content in the retinas of neonatal rats (Hong et al., 2014) and induces retinal microglia activation and increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in neonatal mice (Tremblay et al., 2013). Microglia activation appears to be a critical link between systemic infection or sepsis and retinal inflammation. Exposure of primary pig retinal microglia to LPS in vitro increases the secretion of IL-1β and other proinflammatory cytokines into the culture media (Lim et al., 2019). Other models of retinal development provide additional insight. Using the chronically instrumented fetal sheep model, Loeliger and colleagues demonstrated that systemic LPS administration during the late prenatal period does not alter retinal vascularization, blood vessel width, or induce neovascularization (Loeliger et al., 2011). However, the total thickness of the central and peripheral retina was reduced and Ganglion cell number in the inner nuclear layer were reduced when compared to controls (Loeliger et al., 2011). Tampering systemic inflammation limits retinal neovascularization as well. In the neonatal OIR mouse model, pro-inflammatory cytokines are upregulated and microglia are activated in the retina, and treatment with a putative “anti-inflammatory” herbal medicine reduced retinal neovascularization via a HIF-1α-VEGF mediated pathway (Yang et al., 2016).

5.2.2. Inflammation as the initial mediator

These experimental findings (Hong et al., 2014; Tremblay et al., 2013) raise the possibility that inflammation plays a mechanistic role in infection-associated retinal abnormalities associated with preterm birth. In keeping with this hypothesis, Wang and colleagues have offered three possible avenues between sepsis and ROP, all of which involve sepsis-induced inflammatory responses (Wang et al., 2019). First, they refer to pathogenetic work done in diabetic retinopathy (Joussen et al., 2004) that points towards inflammation-induced endothelial damage, vessel obstruction and leakage, and subsequent non-perfusion of retinal areas. Second, they raise the possibility that systemic inflammation induces an oxidative stress response, which in turn activates VEGF-pathways (Ushio–Fukai, 2007) and retinal vasoproliferation. Third, they refer to inflammation-induced upregulation of HIF-1α (Malkov et al., 2021), which controls VEGF expression and is linked to ROP (Sun et al., 2020). Thus, it seems plausible that oxidative stress and systemic inflammation might contribute to ROP either separately or jointly.

When Cats and Tan found sepsis and exchange transfusions to be significantly associated with ROP in the mid 1980’s (Cats and Tan, 1985), they did not consider sepsis regulating oxygen as the main risk factor for ROP. Instead, they thought of sepsis-induced hemolysis and the need for transfusion, another prominent risk factor for ROP (Glaser et al., 2023), as the common pathway to ROP (via oxidative stress) (Chalmers et al., 2020). Quantifying oxidative stress in humans and animal models proves difficult due to the overlapping signaling apparatus and relatively short lifespan of oxygen radicals. Recent evidence from 31 infants with ROP and matched controls demonstrated an imbalance in the antioxidant-to-oxidant ratio that leaned to a pro-oxidant status in cases when compared with controls (Erdal et al., 2023). Animal models lend mechanistic credibility to this hypothesis. Using a neonatal piglet model (Hardy et al., 1994), Chemtob and coworkers found that activation of the cyclooxygenase pathway increases free radical formation in the retinal and choroidal vasculature. Subsequent studies confirmed that reactive oxygen species stimulate the release of thromboxane, a mediator of retinal vasoconstriction implicated in the neovascularization phase of ROP (Chemtob et al., 1995).

Oxidative stress may link both oxygen and sepsis to ROP (Saugstad, 2006). Indeed, an oxidative stress response does not require excess oxygen nor does it necessarily stem from sepsis. Excess oxygen free radical formation can be promoted through multiple enzymes such as xanthine oxidase, NADPH, and endothelial nitric oxide, which are both oxygen-sensitive and induced/activated by inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Again, these relationships suggest that sepsis and oxygen work together in the causal pathway to ROP via free radical formation. In support of this relationship, Seema et al. found that levels of TNF, but not of free radical scavengers, differed between 30 infants with neonatal sepsis and 20 controls (Seema et al., 1999). The view that oxidative stress plays a role in phase 1 ROP (Fevereiro-Martins et al., 2023) while the impact of inflammation might be stronger in phase 2 dovetails with the overarching proposal that hyperoxia might exert a stronger causal effect in gestationally younger infants, while sepsis is a more prominent risk factor in gestationally older infants (Chen et al., 2011b).

In addition to an oxidative stress response, neonatal sepsis elicits intermittent or sustained systemic inflammation (ISSI), which in its worst form is referred to as a “cytokine storm” (Dammann and Leviton, 2014). If ISSI connects sepsis and ROP, systemically elevated markers of inflammation should be associated with an increased risk for ROP. Indeed, multiple studies suggest this is the case. Silveira et al. found median plasma levels of interleukin (IL) −6, −8, and −10 (but not of IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α) elevated on postnatal d1 in eight infants with severe ROP compared to 49 infants who did not develop ROP (Silveira et al., 2011). Sood and colleagues compared inflammatory cytokine levels in whole blood from 877 infants with a birthweight below 1,000g (Sood et al., 2010). They found that IL-6 levels on the first postnatal day were closely tied to ROP presence and stage. IL-6 was significantly higher in infants with mild ROP when compared with preterm infants without ROP and this relationship was strengthened when comparing ROP severity. IL-6 plays a nuanced role in the inflammatory cascade with both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties and directly regulates the synthesis of other acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) (Tanaka et al., 2014). This relationship may explain why CRP levels on postnatal day 3 were able to distinguish was able to identify preterm infants who went on to develop mild ROP (Sood et al., 2010). CRP concentration continued to be elevated across the first 21 days of life in the cohort of infants who developed ROP suggesting that prenatal and postnatal inflammation drive the underlying pathogenesis of ROP. Further, down-regulation of cytokines that regulate T-cell activation and neutrophil recruitment as part of the innate immune response suggest that the immature immune response in preterm infants may predispose them to exaggerated inflammatory responses and/or delayed resolution.

In a small case-control study, Yu and coauthors matched 30 infants with a gestational age <32wks with 62 infants without ROP on gestational age and birthweight. In serum obtained by umbilical cord venipuncture they found levels of IL-7, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, as well as macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and −1β elevated in cases compared to controls (Yu et al., 2014). Since these measurements were sampled from the umbilical cord, the elevated cytokine concentrations are unlikely to be due to oxygen exposure unless the increased cytokine content in the umbilical cord blood increases the need for postnatal supplemental oxygen administration. In our own ELGAN-study cohort (Dammann et al., 2021a), we measured 27 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors on postnatal days 1, 7, 14 (early epoch), and on days 21 and 28 (late epoch) in 1,205 infants < 28wks gestational age who had at least one eye exam (Holm et al., 2017). In the early epoch (days 1–14), infants with persistent elevation of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and IL-8 concentration at two or more study timepoints were at higher risk for ROP. The association between MPO and IL-8 in infants with high risk for ROP persisted into the late study epoch. Other cytokines, including IL-6, serum amyloid A (SAA), and TNF-receptors 1 and 2, were also associated with an increased risk for ROP in the second epoch. Again, these findings support the hypothesis that systemic inflammation plays a more prominent role in stage 2 of ROP etiology than in stage 1. A recent comprehensive analysis of the literature on systemic cytokines and ROP still focuses on oxygen exposure as the root cause and sees cytokine production only as a characteristic of neonatal sepsis, which in turn, is listed as one of multiple neonatal “related disorders” that happen to be associated with systemic inflammation (Wu et al., 2023).

5.2.3. Growth factors as the final common pathway

The hypothesis that neonatal sepsis is a causal risk factor for ROP is further supported by the observation that systemic inflammatory cytokines generated in the context of sepsis may regulate or interfere with the vasculogenic growth factor network that controls retinal vascularization. This link between inflammation and vascular fate within the retina may be viewed as the final molecular pathway to ROP (Pierce et al., 1995; Ramshekar and Hartnett, 2021; Tsai et al., 2022), regardless of the initial event rising from oxygen exposure or sepsis.

The putative regulator of retinal neovascularization in oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) models is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Ramshekar and Hartnett, 2021), and VEGF’s placeholder in vasculogenesis has led to the development of injectable intra-ocular anti-VEGF molecules as a treatment for ROP (Hartnett, 2020). VEGF is regulated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF), which bind to the promoter sequence of the VEGF gene to induce its expression (Penn et al., 2008). Inhibition of the HIF/VEGF pathway by celastrol, a vine plant extract with anti-inflammatory properties, inhibits retinal microglia activation and retinal inflammation, and celastrol reduces retinal neovascularization and promotes vascularization in the mouse OIR model (Zhao et al., 2022). Recombinant thrombomodulin domain 1 (Huang et al., 2021) and melatonin (Xu et al., 2018) appear to exert similar protective effects through their anti-inflammatory properties.

In one of the two papers on LPS-induced retinopathy, VEGF was upregulated in whole retina extracts within 2 days of LPS exposure in mice (Tremblay et al., 2013), but retinal VEGF concentration was not altered in rat pups exposed to early LPS (Hong et al., 2014). Rather, the expression of the anti-angiogenesis molecule thrombospondin (TSP)-1 was increased in rat pup retinas following LPS exposure, which coincided with higher retinal concentrations of IL-1β and IL-12a (Hong et al., 2014). Intravitreal injection of peptidoglycan (PGN, mimicking gram-positive infection) or LPS injection (mimicking gram-negative infection) lead to increased VEGF expression in the retina (Lafreniere et al., 2019). Interestingly, bevacizumab administration had a dramatic effect on retinal cytokine content in PGN-injected eyes but did not alter retinal cytokine content in LPS-injected eyes. As examples, TNF and CXCL1 were reduced by nearly 50% in PGN-injected eyes but were unchanged in LPS-injected eyes. Similar studies examining the effects of gram-positive and gram-negative sepsis on retinal neovascularization and the modifying effects of VEGF blocking compounds in the immature retina have not been performed.

6. Hill’s Viewpoints Applied to Sepsis and ROP

In this section, we subject the available evidence on sepsis as a candidate cause of ROP to Bradford Hill’s nine viewpoints for causal inference (Hill, 1965) that Alfredo Morabia has called the “sui generis” approach to causal inference in epidemiology (Morabia, 2013). Although the Hill heuristics were originally intended to be applied to the results of a single epidemiological study, we apply them here to the cumulative evidence documented in previous sections.

In the 1950s and 60s, the causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer was still a matter of debate. In 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General’s office published a committee report that listed a handful of “criteria for causation” that supported the link between smoking and cancer (United States. Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health., 1964). One year later, medical statistician and epidemiologist Austin Bradford Hill published a lecture on similar causal criteria (he called them “viewpoints”) that, as Hill suggested, cannot prove causation but offer support for a causal hypothesis (Hill, 1965). The paper is among the most influential in the field of epidemiology and remains valuable when considering such causal hypotheses. For example, Hill’s viewpoints were used by multiple investigative teams to evaluate the evidence in support of the hypothesis that Zika virus causes microcephaly (Awadh et al., 2017; Frank et al., 2016; Rasmussen et al., 2016).

Hill’s heuristics draw on the concept of explanatory coherence or “good fit”. One piece of information coheres with others if it fits well with the overarching story. Coherence is strongly context dependent. Although coherence is itself one of the nine individual viewpoints (see §6.8), all nine viewpoints represent a set of factors that can be seen as an explanatory coherence evidence network when brought together with models of explanatory coherence. (Poston, 2014; Thagard, 2006). Each factor supports other factors to jointly support a causal hypothesis (Dammann, 2018). Together with philosophers Ted Poston and Paul Thagard, one of the authors (OD) has previously shown that Hill’s heuristics can be mapped onto other systems of causal explanation (Dammann et al., 2020).

In the present context, Hill’s heuristics can offer support for the hypothesis that neonatal sepsis causes ROP based on the degree to which each viewpiont can be “checked off” against the available evidence connecting neonatal sepsis and ROP. In what follows, we demonstrate how evidence from ROP research supports most of Hill’s nine viewpoints, thereby indicating that causation is a better explanation for the sepsis-ROP relationship than mere statistical association. For each viewpoint we give only a summary of the evidence; much of the supporting detail can be found in the previous sections of this paper.

6.1. Temporality

Temporality is the viewpoint that the purported cause must precede the effect to avoid a wrong causal conclusion in cases where the causal relationship is inverse. Most studies of sepsis as a risk factor of ROP do not address the timing of sepsis in relationship to ROP diagnosis and treatment. However, it is rational to assume that reverse causation is not a viable explanation of the association – ROP is not likely to cause sepsis, other than in the unlikely scenario where the eye exam contributes to a systemic infection.

6.2. Strength of association

Hill proposed that the strength of the association supports causation rather than association alone. The pooled odds ratios for any ROP and severe ROP in one meta-analysis (Wang et al., 2019) were 1.6 and 2.3, respectively, representing a 60% and 130% risk increase for preterm infants who experience sepsis. In another meta-analysis these estimates were 2.2 and 1.9, respectively (Huang et al., 2019). These data (and those summarized in §5.1) can be seen as indicating a strong association.

6.3. Consistency of association

The two available meta-analyses on sepsis as a risk factor for any (severe) ROP refer to 11 (6) (Wang et al., 2019) and 20 (22) (Huang et al., 2019) studies. The majority of these studies show a higher risk of ROP with neonatal sepsis. More recently, an analysis of 118,650 preterm infants identified that ROP was diagnosed in 61.7% of preterm infants who experienced late onset sepsis compared to an incidence of 29% in preterm infants without late onset sepsis (Flannery et al., 2022). We conclude that the association between sepsis and ROP is consistent across many studies.

6.4. Specificity of association

This viewpoint refers to the idea promoted by Robert Koch and Jacob Henle that one bug causes one disease and one disease is caused by one bug. A high degree of specificity would mean that sepsis causes ROP and nothing else and that ROP is caused by sepsis and nothing else. Of course, this level of specificity does not hold in the case of sepsis and ROP, and it probably does not hold for any other cause of complex disease. Thygesen and coworkers have pointed out that multiple authors have criticized this viewpoint and even suggested that it is useless (Thygesen et al., 2005), while Fedak et al. concede that it “may have new and interesting implications in the broader context of data integration” (Fedak et al., 2015). In returning to our case study that smoking causes lung cancer, approximately 20% of lung cancer patients have no previous exposure to cigarette smoke and cigarette smoking is linked to several other diseases (Corrales et al., 2020). We believe that such level of specificity is rare and this viewpoint should be weighted less than other viewpoints.

6.5. Biological gradient

The biological gradient refers to dose-response relationships. Certainly, sepsis principally refers to an inflammatory host response with end organ impairment, which may represent the life-threatening condition known as septic shock or more tempered manifestations. To our knowledge, no studies have attempted to link “severity” of sepsis or number of septic episodes and the risk for ROP. However, we are aware of one analysis based on a national dataset from Germany published as an abstract (in German). The authors found in 12,563 preterm infants (22–28 completed weeks of gestation) that the relative risk for the association between sepsis increases from 1.4 (1.2–1.6) in preterm infants with one sepsis episode to 1.8 (1.2–2.3) if infants had two episodes and further to 4.7 (2.3–9.7) with more than two episodes (Glaser et al., forthcoming). We consider these data strong evidence in support of the notion that a “dose-response” relationship exists between the number of sepsis episodes and the risk for ROP.

6.6. Experiment

Animal models seeking to identify a potential link between sepsis and retinal neovascularization have demonstrated that LPS exposure in rats (Hong et al., 2014) and sheep (Loeliger et al., 2011) lead to ROP-like abnormalities in the retina of the exposed animals. Importantly, LPS-induced retinal vascular abnormalities in these models did not require exposure to exogenous oxygen.

6.7. Plausibility

Much of the plausibility must come by reference to the mechanism that connects sepsis and ROP. Multiple previous papers by us (Dammann, 2010; Lee and Dammann, 2012; Rivera et al., 2017) and others (Fevereiro-Martins et al., 2022) have reviewed the accumulating evidence and mounted the argument that systemic inflammation is a plausible mediator between neonatal sepsis and ROP (see also §5.2.2, above). In tandem with systemic inflammation, oxidative stress appears to play a mechanistic role; the differential or joint role of the two mechanisms in ROP production remains to be clarified.

6.8. Coherence

A causal role for sepsis in ROP is coherent with the larger pool of evidence about ROP. First, sepsis leads to ROP-like retina abnormalities in animal models (Hong et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2019). Second, sepsis is strongly associated with ROP in multiple observational studies (Huang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Third, sepsis generates inflammatory cytokines and immune responses that are likely involved in the pathogenesis of ROP and adverse visual outcomes in preterm infants (Ingvaldsen et al., 2021). The conjecture that ROP is a causal initiator of ROP is finds strong support from a coherent network of multiple lines of explanatory evidence.

6.9. Analogy

Neonatal sepsis is also associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes such as cerebral palsy (Alshaikh et al., 2013) and cognitive abnormalities (Cai et al., 2019) among preterm newborns. The analogy with ROP becomes eminently clear when considering the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of adverse visual outcomes among preterm infants independent of ROP, which led us to postulate a “visuopathy of prematurity” that shares causes (oxygen, sepsis) and mechanisms (oxidative stress, inflammation) with ROP (Ingvaldsen et al., 2021). Another analogy would be that fungal sepsis, in addition to bacterial sepsis, is associated with an increased risk for ROP (see §5.1).

6.10. Conclusion

In sum, all of Hill’s viewpoints (except specificity which may be irrelevant in a world of causal inference post Koch and Henle) support the notion that neonatal sepsis is a cause of ROP and not an innocent bystander. The available evidence suggests that the observed statistical association between sepsis and ROP reflects biological causation.

7. Future Directions and Conclusion

Retinopathy of prematurity is a complex neonatal disorder with multiple contributing risk factors. In this paper, we provide substantial evidence in support of the paradigm that neonatal sepsis is a cause of ROP (not a condition, mechanism, or even innocent bystander) by initiating the early stages of the pathomechanism of ROP – systemic inflammation. We have used the model of etiological explanation to support our hypothesis, which distinguishes between two overlapping processes in ROP causation (Fig. 1).

It can be shown that sepsis can initiate the early stages of the pathomechanism via systemic inflammation (causation process) and that systemic inflammation can contribute to growth factor aberrations and the retinal characteristics of ROP (disease process). The combination of these factors with immaturity at birth (as intrinsic risk modifier) and prenatal inflammation (as extrinsic facilitator) provides a cogent and functional framework of ROP occurrence. Finally, we applied the Bradford Hill heuristics to the available evidence. Taken together, these approaches to the available evidence strongly point to neonatal sepsis as a causal initiator of ROP.

For the sheer complexity of the etiological explanation of ROP, future research requires a large prospective cohort study focused on ROP. Several critical questions remain, including whether prenatal infection/inflammation modifies the oxygen- and sepsis-associated risk for ROP in similar or different ways, and whether oxidative stress and systemic inflammation interact as pathomechanisms for ROP. Moreover, the differential effect of oxygen and sepsis at different post-conceptional ages on the two phases of ROP should be clarified using novel measures of oxygen exposure and retinal diagnosis based on advanced imaging such as optical coherence tomography. Regarding the timing of neonatal sepsis, the relative contribution of early and late onset sepsis deserves further study.

It is our hope that we have provided sufficient rationale to motivate further work on neonatal sepsis as a cause of ROP. These studies are essential to designing strategies that reduce the burden associated with ROP.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Eye Institute (EY029318, EY034969).

We thank Alan Leviton for his comments on an early version of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Alshaikh B, et al. , 2013. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of very low birth weight infants with neonatal sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Perinatology 33, 558–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aralikatti AK, et al. , 2010. Is ethnicity a risk factor for severe retinopathy of prematurity? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 95, F174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton N, 1954. Pathological basis of retrolental fibroplasia. Br J Ophthalmol 38, 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton N, et al. , 1954. Effect of oxygen on developing retinal vessels with particular reference to the problem of retrolental fibroplasia. Br J Ophthalmol 38, 397–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awadh A, et al. , 2017. Does Zika Virus Cause Microcephaly - Applying the Bradford Hill Viewpoints. PLoS Curr 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad R, et al. , 2020. Retinopathy of Prematurity: How to Prevent the Third Epidemics in Developing Countries. Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology 9, 440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharwani SK, Dhanireddy R, 2008. Systemic fungal infection is associated with the development of retinopathy of prematurity in very low birth weight infants: a meta-review. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 28, 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blodi FC, Parke PC, 1953. Retrolental Fibroplasia. The American Journal of Nursing 53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonafiglia E, et al. , 2022. Early and late onset sepsis and retinopathy of prematurity in a cohort of preterm infants. Sci Rep 12, 11675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent A, 2008. The difference between cause and condition. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 108, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Cai S, et al. , 2019. Short- and Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Very Preterm Infants with Neonatal Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, et al. , 2000. Cytokine induction in fetal rat brains and brain injury in neonatal rats after maternal lipopolysaccharide administration. Pediatr Res 47, 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cailes B, et al. , 2018. Epidemiology of UK neonatal infections: the neonIN infection surveillance network. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 103, F547–F553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K, 1951. Intensive oxygen therapy as a possible cause of retrolental fibroplasias: a clinical approach. Med J Austr 2, 48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright N, 1994. No Causes in, No Causes out, Nature’s Capacities and Their Measurement, pp. 39–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cats BP, Tan KE, 1985. Retinopathy of prematurity: review of a four-year period. British Journal of Ophthalmology 69, 500–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers J, et al. , 2020. Effect of red blood cell transfusion on the development of retinopathy of prematurity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob S, et al. , 1995. Peroxide-cyclooxygenase interactions in postasphyxial changes in retinal and choroidal hemodynamics. Journal of Applied Physiology 78, 2039–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Smith LE, 2007. Retinopathy of prematurity. Angiogenesis 10, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JS, et al. , 2021. Quantification of Early Neonatal Oxygen Exposure as a Risk Factor for Retinopathy of Prematurity Requiring Treatment. Ophthalmology Science 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, et al. , 2011a. Placenta Microbiology and Histology and the Risk for Severe Retinopathy of Prematurity. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52, 7052–7058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, et al. , 2011b. Infection, oxygen, and immaturity: interacting risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity. Neonatology 99, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML, et al. , 2010. High or low oxygen saturation and severe retinopathy of prematurity: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 125, e1483–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu A, et al. , 2020. Prenatal intrauterine growth restriction and risk of retinopathy of prematurity. Scientific Reports 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton S, Fruttiger M, 2003. Role of arteries in oxygen induced vaso-obliteration. Experimental Eye Research 77, 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggins SA, Glaser K, 2022. Updates in Late-Onset Sepsis: Risk Assessment, Therapy, and Outcomes. NeoReviews 23, 738–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales L, et al. , 2020. Lung cancer in never smokers: The role of different risk factors other than tobacco smoking. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 148, 102895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai AI, et al. , 2015. Maternal Iron Deficiency Anemia as a Risk Factor for the Development of Retinopathy of Prematurity. Pediatr Neurol 53, 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, 2010. Inflammation and retinopathy of prematurity. Acta Paediatr 99, 975–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, 2017. The Etiological Stance: Explaining Illness Occurrence. Perspect Biol Med 60, 151–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, 2018. Hill’s Heuristics and Explanatory Coherentism in Epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 187, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, 2020. Etiological Explanations: Illness Causation Theory. CRC Press, Boca Raton. [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, 2021. Agent-based models as etio-prognostic explanations. Argumenta. [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, 2023. Does prematurity “per se” cause visual deficits in preterm infants without retinopathy of prematurity? Eye (Lond). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]