Abstract

Objectives:

To characterize patient portal use among older adults receiving skilled home health (HH) care.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and Participants:

Older adults (age ≥65 years) who received HH care from a large, academic health system between 2017 to 2022 (n = 8409 HH episodes provided to n = 4878 unique individuals).

Methods:

We captured individual and HH episode characteristics from the electronic health record and identified specific types and dates of portal use for those with an active patient portal. We calculated the proportion of episodes in which patients engaged in specific patient portal activities (eg, viewing test results, managing appointments, sending messages). We used multivariable logistic regression to model the odds of engaging in each activity as a function of patient and episode characteristics, and charted the timing of patient portal activities across the 60-day HH episode.

Results:

The patient portal was used by older adults in more than half (58%) of the episodes examined. Among those using their portal account during an HH episode, 84% viewed test results, 77% managed an existing appointment, 72% managed medications, and 55% sent a message to a provider. Adjusted odds of portal use were higher among HH patients who were married (aOR: 1.77, P < .001), receiving HH post-COVID pandemic (aOR: 2.73, P <.001), and accessing HH following a hospitalization (aOR: 1.30, P <.001) and lower among those who were Black compared with White (aOR: 0.52, P < .001). Portal use, particularly viewing test results and clinical notes and managing existing appointments, was highest during the first 10 days of an HH episode, especially among patients referred following a hospitalization.

Conclusions and Implications:

HH patients use the patient portal to perform care management tasks and access clinical information. Study findings support opportunities to harness the patient portal to bridge information gaps and care coordination during HH care.

Keywords: Home health care, patient portal, home care, MyChart, consumer-facing technology, health information technology

As a growing number of older adults choose to age in place, demand for clinical care in home and community settings is increasing. The Medicare Home Health (HH) benefit is the most used form of home-based clinical care among Medicare enrollees.1 HH delivers skilled nursing, therapy, and other services through visits to the patient’s home across a 60-day care episode. In 2021, 3.0 million Medicare beneficiaries accessed HH care.2

Poor information transfer between HH and other care settings poses a perennial challenge to delivering high-quality HH care. Most HH patients are referred for post-acute care following a hospitalization, yet the HH care team rarely has comprehensive information on what transpired during the hospital stay.3–6 Nor do HH providers have reliable access to comprehensive medical information for patients who are referred from the community (without a preceding hospitalization).3,4,7 As a result, HH providers often rely on informal reporting from patients and their care partners to learn about the patient’s recent medical history, which increases risk for potential errors.5,8

Patient portals are provider-sponsored online applications that allow patients to perform care management tasks including viewing health information and messaging providers. These capabilities could prove particularly valuable during an HH episode, allowing patients to access reliable information regarding their hospital stay and/or medical history and to communicate with other providers before HH discharge. Recent studies find that portal use is increasing.9,10 An estimated 39.5% of adult patients accessed a patient portal in 2020, although use among older adults (age ≥65 years) has lagged behind younger age groups.9 However, no prior work has investigated portal use during an HH episode. The present study aims to fill this literature gap by investigating whether certain groups are more likely to use their portal during HH and what portal activities are completed during HH.

This study leveraged linked electronic health record (EHR) and patient portal (specifically, MyChart) records for patients in a large, academic health system to provide the first information regarding patient portal use during HH. Study objectives included estimating rates of portal use among HH patients, identifying patient and HH episode characteristics associated with portal use, describing what care management activities are performed using the portal during an HH episode, and evaluating whether portal use fluctuates across the course of an HH episode. We hypothesized that those receiving post-acute HH would be more likely to use their portal, given their more recent acute care utilization, and that HH patients would be most likely to use their portal to access clinical notes and make appointments with providers, given prior work indicating information gaps between HH and other providers.

Methods

Data and Sample

Data included EHR and patient portal information for older adults (age ≥65 years) cared for within a large, academic health system. Individuals were included in our analytic sample if they received at least 1 HH episode from the system’s affiliated HH agency with a start of care date between October 3, 2017, and August 3, 2022. We excluded individuals who were not primary care patients within this health system (defined as having 2 or more primary care visits within 2 years with a system-affiliated provider, prior to HH admission). The unit of analysis is the 60-day HH episode; patients can receive multiple successive HH episodes so long as they are recertified by a physician as continuing to meet the HH eligibility requirements. The average patient receives 2 episodes during each spell of HH care.11 The final analytic sample included 8409 HH episodes for 4878 unique individuals. This research meets Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB criteria for exempt human subjects research.

Measures

From EHR data, we captured patient sociodemographic characteristics, dementia status, and HH episode characteristics. Sociodemographic characteristics included patient age, sex, race, and whether the individual was married or partnered. Dementia status was determined based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes noted in the EHR either in claims or the patient problem list, following an approach developed by Grodstein et al.12 HH episode characteristics included whether the episode occurred after outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (defined as admission date after March 15, 2020), whether the episode was preceded by a hospitalization (episodes beginning within 14 days of an acute care or institutional post-acute discharge were considered “post-acute”), and whether it was the first (“index”) episode within the study time frame.

We measured patient portal use based on dates and times of specific portal activities. We created 7 indicators to categorize types of portal activities: (1) viewing test results, (2) managing existing appointments (including viewing, confirming, or canceling the appointment), (3) managing medications (including view medications and requesting prescription renewal), (4) sending messages to a provider, (5) viewing clinical notes, (6) viewing health conditions, and (7) managing billing (including viewing and paying bills). (See Supplementary Table 1 for a list of specific MyChart actions for each activity.)

Statistical Analyses

We comparatively examined characteristics of HH patients who did vs did not use the patient portal during their HH episode, using Pearson chi-square and t tests to determine between-group differences. We then limited the sample to episodes in which the patient portal was used and calculated the proportion of episodes in which patients engaged in each of the 7 specific portal activities. We modeled the odds of engaging in each type of portal activity as a function of patient and episode characteristics using multivariable logistic regression.

Finally, we reported the timing of patient portal use during the episode as a frequency distribution by calculating the percentage of instances of an activity that occurred during each of the 60 days in an HH episode. For example, if 600 total messages were sent during HH and 60 of these were sent on the first day of the HH episode, the day 1 percentage would be 10%. We reported timing of portal activities overall and stratified by whether the episode was post-acute.

Results

The patient portal was used in more than half (58%) of HH episodes incurred by older primary care patients at the academic health system (Supplementary Table 2). HH episodes involving patient portal use were more common among patients who were married or partnered (45% vs 30%, P <.001) and White (68% vs 57%, P < .001) and less often among patients who were Black (25% vs 39%, P < .001). HH episodes involving patient portal use were more common post-COVID pandemic (72% vs 51%, P < .001) and when preceded by a hospitalization (52% vs 45%, P < .001).

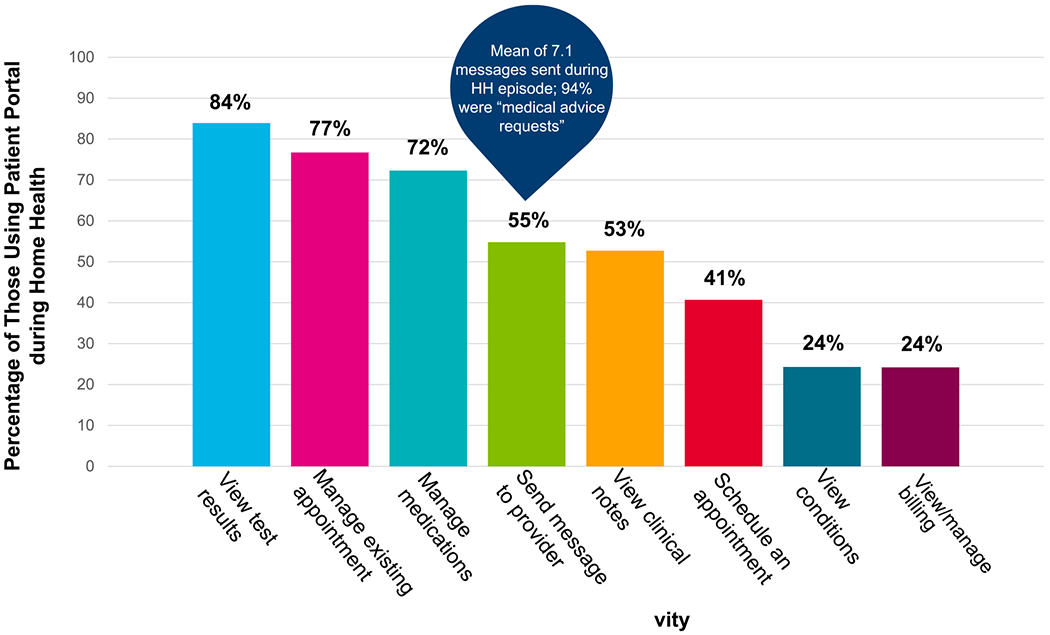

Among HH episodes involving patient portal use, the portal was most often used to view test results (84%), manage existing appointments (77%), manage medications (72%), message providers (55%), view clinical notes (53%), schedule a new appointment (41%), view health conditions (24%), and manage billing (24%) (Figure 1). Of episodes during which at least 1 message was sent to a provider, an average of 7.1 messages were sent during the episode and 94% of messages were categorized as medical advice requests.

Fig. 1.

Types of portal activities among patients during home health care (n = 4889). Data are from 4889 home health episodes for older adults (age ≥65 years) receiving home health care from an academic health system between 2017 and 2022.

Use of the patient portal was greater among HH patients who were married or partnered [adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.77, P < .001], receiving HH post-COVID pandemic (aOR: 2.73, P < .001), following a hospitalization (aOR: 1.30, P < .001), and in their first HH episode (aOR: 1.27, P < .001) (Supplementary Table 3). Compared with White patients, Black patients had significantly lower odds of using the patient portal overall (aOR: 0.52, P < .001), and lower odds of using the portal to view test results (aOR: 0.62, P < .001), message a provider (aOR: 0.57, P < .001), or view clinical notes (aOR: 0.73, P < .001). Although HH episodes occurring post-COVID had significantly higher odds of all types of MyChart use, this relationship was particularly strong for managing existing appointments (aOR: 3.51, P < .001), managing medications (aOR: 2.45, P < .001), and viewing clinical notes (aOR: 3.30, P < .001). Episodes preceded by a hospitalization were associated with higher odds of engaging in all portal activities.

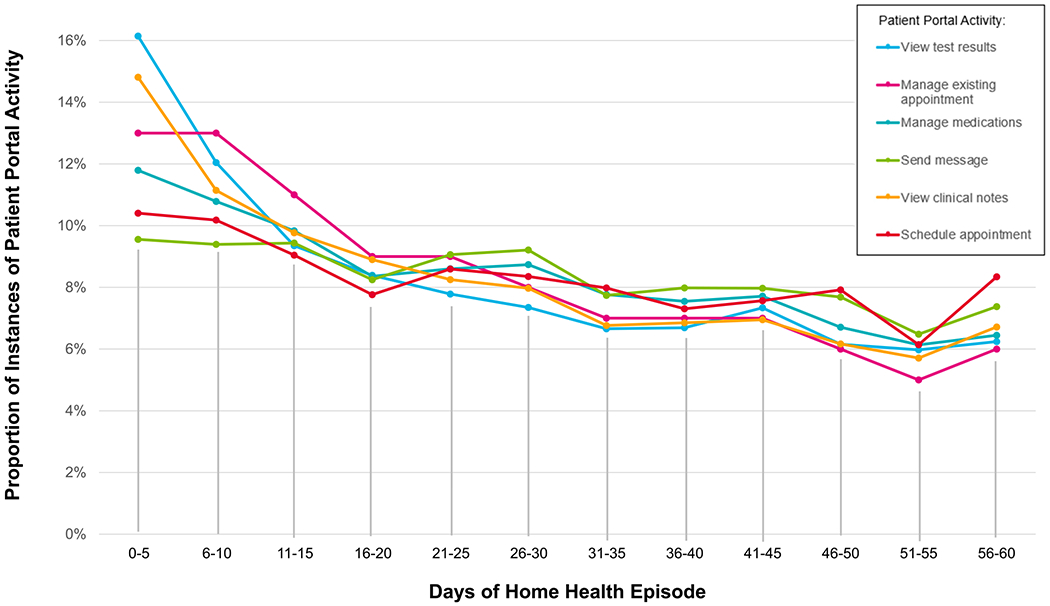

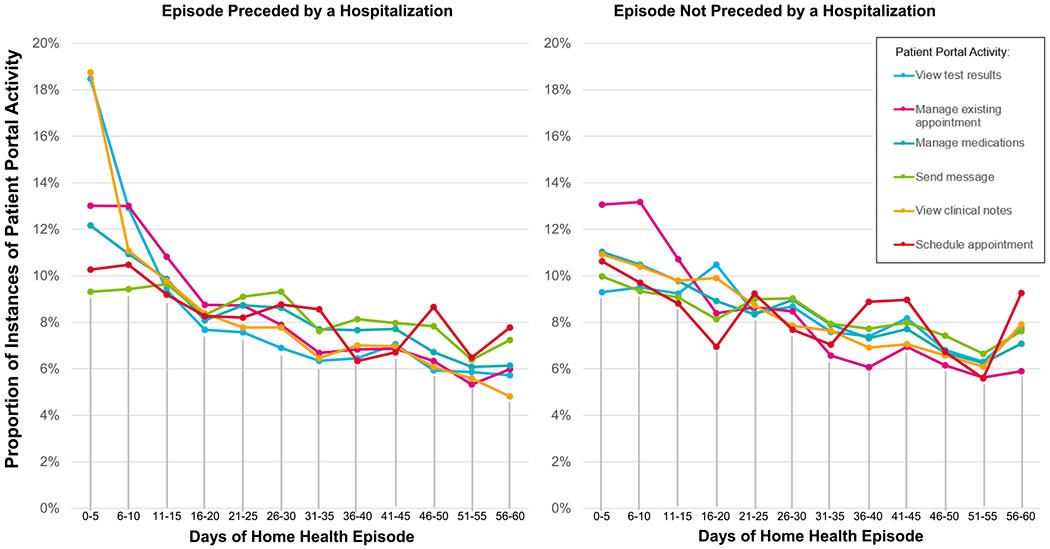

Patient portal use, particularly viewing test results and clinical notes and managing existing appointments, was highest during the first 5 days of an HH episode (Figure 2; see Supplementary Figure 1 for results by individual day of the HH episode). Portal use remains fairly level with a slight decrease from days 11 to 55 and slight increase in the last 5 days of the episode (days 56-60), driven by upticks in scheduling appointments, messaging providers, viewing clinical notes, and managing existing appointments. Trends in patient portal use are broadly similar for HH patients, regardless of whether they enter from the community or following a hospitalization. However, notably higher rates of viewing test results and viewing clinical notes were observed within the first 5 days of HH episodes preceded by a hospitalization (Figure 3). Additionally, notably higher rates of scheduling an appointment and viewing clinical notes were observed within the last 5 days of HH episodes not preceded by a hospitalization.

Fig. 2.

Timing of patient portal use during home health episode (n = 4889). Data are from 4889 home health episodes for older adults (age ≥65 years) receiving home health care from an academic health system between 2017 and 2022.

Fig. 3.

Timing of patient portal use during home health care, comparing those who did vs did not have a preceding hospitalization (n = 4889). Data are from 4889 home health episodes for older adults (age ≥65 years) receiving home health care from an academic health system between 2017 and 2022.

Discussion

This is the first study to describe use of the patient portal within the context of HH care. We found that the patient portal was used in more than half (58%) of HH episodes to facilitate care management—most commonly to view clinical information, manage appointments, and message providers. Rates of portal use were relatively stable throughout the HH episode, with spikes in use during the first 5 days of HH care and just prior to discharge. Findings support the potential feasibility of harnessing patient portals to bridge information gaps during HH care, such as supplementing the hospital discharge summary.

Patient portal use during HH was greater among older adults who were White, married, and during episodes that occurred post-COVID-19 pandemic, were preceded by a hospital stay, and were the first HH episode. Findings align with previous studies that have considered patient portal use in the older adult population overall and found that older adults are more likely to have and use a patient portal account when they are younger, White, and married or partnered.13,14 We also observed racial differences in types of portal use, finding that Black patients were significantly less likely to use their portal to view test results or message their provider as compared to White patients. Observed differences by age and race may reflect differential acceptability and accessibility of virtual modalities for managing health care tasks, stemming from both individual comfort level and preferences as well as neighborhood-level structural factors determining access, such as broadband availability.14–16 However, the overwhelming majority of interventional research to mitigate disparities in portal access and use have targeted individual characteristics, rather than system-level features.17,18 The significant increase in portal use during HH that was observed following the COVID-19 pandemic is notable yet unsurprising given the dramatic shift toward greater use of telehealth and digital modalities of health care communication and delivery during this time.10

Beyond routine care management, there are specific use cases for accessing the patient portal during HH. The first is leveraging the portal as a source of information regarding recent treatments and health care experiences, information that is often missing or incomplete in the referral documentation received by HH staff.3,4 This information is critical in guiding HH care planning decisions related to visit timing and frequency, care pathways, and even medication reconciliation.4 We observed that patient portal use was highest in the first 5 days of the HH episode and that patients receiving HH following a hospital stay had especially high rates of viewing test results and clinical notes at the beginning of the HH episode. These findings indicate that HH patients rely on the patient portal to marshal information regarding their health at the outset of an HH episode; however, it is unclear to what degree patients are sharing this information with the HH care team.

Limitations

The most notable limitation is the reliance on data from a single health system: although the data provided a rich picture of both HH use and patient portal activities, generalizability to other systems and populations may be limited. Additionally, we did not have access to information regarding whether HH patients were simultaneously interacting with providers or accessing health information using other modalities, such as placing phone calls to their physicians or accessing paper copies of their recent hospital records. Finally, family and unpaid caregivers often access older adults’ patient portals.14 A limitation of our data was the inability to reliably determine whether the user was the older adult or a caregiver using the older adult’s log-in credentials.

Conclusions and Implications

Home health patients currently use patient portals to perform care management tasks and access clinical information relevant to their care during HH. Patient portals present a potentially valuable opportunity to bridge the information gap between HH and other care settings.

Supplementary Material

Funding Sources:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R35 AG072310, K01 AG081502).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ankuda CK, Ornstein KA, Leff B, et al. Defining a taxonomy of Medicare-funded home-based clinical care using claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.March 2023 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2023. Accessed July 3, 2023. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Ch8_Mar23_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sockolow PS, Bowles KH, Le NB, et al. There’s a problem with the problem list: incongruence of patient problem information across the home care admission. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sockolow PS, Bowles KH, Wojciechowicz C, Bass EJ. Incorporating home healthcare nurses’ admission information needs to inform data standards. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1278–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones CD, Jones J, Bowles KH, et al. Quality of hospital communication and patient Preparation for home health care: results from a statewide survey of home health care nurses and staff. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:487–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romagnoli KM, Handler SM, Ligons FM, Hochheiser H. Home-care nurses’ perceptions of unmet information needs and communication difficulties of older patients in the immediate post-hospital discharge period. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:324–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgdorf JG, Wolff JL, Chase JA, Arbaje AI. Barriers and facilitators to family caregiver training during home health care: a multisite qualitative analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70:1325–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbaje AI, Hughes A, Werner N, et al. Information management goals and process failures during home visits for middle-aged and older adults receiving skilled home healthcare services after hospital discharge: a multisite, qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:111–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Health information National Trends Survey: Hints Briefs number 45. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/Briefs/HINTS_Brief_45.pdf

- 10.Huang M, Khurana A, Mastorakos G, et al. Patient portal messaging for Asynchronous virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Retrospective analysis. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9:e35187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.March 2022 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). Accessed July 6, 2022. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Mar22_MedPAC_ReportToCongress_Ch8_SEC.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grodstein F, Chang CH, Capuano AW, et al. Identification of dementia in recent Medicare claims data, compared with Rigorous clinical Assessments. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022;77:1272–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakaguchi-Tang DK, Bosold AL, Choi YK, Turner AM. Patient portal use and experience among older adults: systematic review. JMIR Med Inform. 2017;5:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgdorf JG, Fabius CD, Wolff JL. Use of provider-sponsored patient portals among older adults and their family caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71:1177–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okoye SM, Mulcahy JF, Fabius CD, Burgdorf JG, Wolff JL. Neighborhood broadband and use of telehealth among older adults: cross-sectional study of National Survey data linked with Census data. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e26242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam K, Lu AD, Shi Y, Covinsky KE. Assessing telemedicine unreadiness among older adults in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1389–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleason KT, Powell DS, Wec A, et al. Patient portal interventions: a scoping review of functionality, automation used, and therapeutic elements of patient portal interventions. JAMIA Open. 2023;6:ooad077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman LV, Masterson Creber RM, Benda NC, Wright D, Vawdrey DK, Ancker JS. Interventions to increase patient portal use in vulnerable populations: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26:855–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.