Abstract

Influenza A virus (IAV) continues to pose a pandemic threat to public health, resulting a high mortality rate annually and during pandemic years. Posttranslational modification of viral protein plays a substantial role in regulating IAV infection. Here, based on immunoprecipitation (IP)-based mass spectrometry (MS) and purified virus-coupled MS, a total of 89 phosphorylation sites distributed among 10 encoded viral proteins of IAV were identified, including 60 novel phosphorylation sites. Additionally, for the first time, we provide evidence that PB2 can also be acetylated at site K187. Notably, the PB2 S181 phosphorylation site was consistently identified in both IP-based MS and purified virus-based MS. Both S181 and K187 are exposed on the surface of the PB2 protein and are highly conserved in various IAV strains, suggesting their fundamental importance in the IAV life cycle. Bioinformatic analysis results demonstrated that S181E/A and K187Q/R mimic mutations do not significantly alter the PB2 protein structure. While continuous phosphorylation mimicked by the PB2 S181E mutation substantially decreases viral fitness in mice, PB2 K187Q mimetic acetylation slightly enhances viral virulence in mice. Mechanistically, PB2 S181E substantially impairs viral polymerase activity and viral replication, remarkably dampens protein stability and nuclear accumulation of PB2, and significantly weakens IAV-induced inflammatory responses. Therefore, our study further enriches the database of phosphorylation and acetylation sites of influenza viral proteins, laying a foundation for subsequent mechanistic studies. Meanwhile, the unraveled antiviral effect of PB2 S181E mimetic phosphorylation may provide a new target for the subsequent study of antiviral drugs.

Keywords: H5N1 influenza virus, PB2, Phosphorylation, Acetylation, Viral fitness, Mice

Highlights

-

•

Sixty novel phosphorylation sites were identified on IAV proteins.

-

•

PB2 K187 is found to be acetylated for the first time.

-

•

PB2 S181E mimetic phosphorylation significantly decreases viral fitness in mice.

-

•

PB2 S181E substantially impairs viral polymerase activity and PB2 nuclear accumulation.

-

•

PB2 K187Q mimetic acetylation slightly enhances viral pathogenicity in mice.

1. Introduction

Influenza A virus (IAV) is an enveloped virus with a single-stranded negative-sense RNA genome. Currently, IAV continues to pose a public threat owing to its rapid evolution, the emergence of drug-resistant strains, and the limited efficacy of the vaccine. Among the various subtypes of IAV, the H5 subtype avian influenza viruses (AIVs) have caused numerous fatalities. Although these viruses have not yet gained airborne transmission ability among humans, some H5 viruses can efficiently transmit among ferrets after gaining a few amino acid mutations, highlighting the potential pandemic risk posed by AIVs (Imai et al., 2012). More recently, certain H5N1 variants capable of speading among minks and seals have raised significant concerns about their potential for efficient transmission among humans and wild animals (Agüero et al., 2023; Puryear et al., 2023). The development of novel influenza therapeutics targeting viral factors that regulate viral infection presents a promising approach to combat IAV infection. However, the current understanding of how viral factors participate in different steps of the IAV life cycle is still insufficient.

Phosphorylation and acetylation are actively involved in versatile cellular and physiological processes, including transcription, chemotaxis, metabolism, cell signal transduction, stress response, proteolysis, autophagy, differentiation and neuronal development (Zhang et al., 2021; Shvedunova and Akhtar, 2022). Recent advancements in mass spectrometry (MS) approaches have enabled the extensive study of phosphorylation and acetylation of viral proteins in different viruses (Keating and Striker, 2012; Dawson et al., 2020a; Boergeling et al., 2021). For IAV, increasing evidence has demonstrated that these posttranslational modifications play a pivotal role in regulating the viral life cycle. For example, phosphorylation of IAV proteins affects the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of M1 (Whittaker et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2023b), NP (Zheng W. et al., 2015; Li et al., 2018; Cui et al., 2019) and NEP proteins (Reuther et al., 2014), regulates viral transcription and replication (Mondal et al., 2015; Turrell et al., 2015; Dawson et al., 2020b; Patil et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023a), and virus assembly and budding (Mecate-Zambrano et al., 2020). Acetylation sites, including K31, K103 and K229 of NP (Chen et al., 2017; Giese et al., 2017), K19 and K664 of PA (Chen et al., 2019; Hatakeyama et al., 2022), E2 of PA-X (Oishi et al., 2018), and K108 of NS1 (Ma et al., 2020) also substantially affect viral replication. However, despite accumulating studies have reported the crucial role of phosphorylation and acetylation in regulating the biological functions of viral NP, NS1, M1, M2, PB1 and PA proteins, associated data regarding the PB2 protein are quite scarce. Unraveling the role of phosphorylation and acetylation in the biological function of the PB2 protein may provide clues for the design of novel antiviral strategies, as targeting multifunctional PB2 might provide the opportunity to block infection at various stages of virus replication.

In this study, using IP-based MS and purified virus-coupled MS methods, 89 phosphorylation sites distributed among PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M1, M2, NS1, NEP, PB1-F2 and PA-X were successfully identified in the H5N1 virus A/chicken/Jiangsu/k0402/2010 (CK10 strain). In addition to 29 previously-identified phosphorylation sites, 60 novel phosphorylation sites were identified. Among them, a total of eight phosphorylation sites were identified on the PB2 protein. Notably, 10 phosphorylation sites, including PB2 S181, were consistently identified by different approaches. More importantly, for the first time, we found that the PB2 protein can also be acetylated at the key site of PB2, K187. By analyzing phosphorylation/dephosphorylation-mimetic mutations of PB2 S181, and acetylation/deacetylation-mimetic mutations of PB2 K187, we systematically explored the roles and related mechanisms of phosphorylation and acetylation of these sites in shaping the biological characteristics and virulence of the CK10 virus in mice.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Viruses and cells

The H5N1 AIVs CK10 strain was isolated in live poultry markets in 2010 (Hu et al., 2013) and propagated once in 9-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) embryonated chicken eggs for seed virus. Canine MDCK, human HEK 293T, and avian DF-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated in a 37 °C in a 6% CO2 incubator. The eight-plasmid reverse genetic system of the CK10 virus was constructed previously (Hu et al., 2013). The wild type virus (rPB2-WT) and the mutant viruses rPB2-S181A, rPB2-S181E and rPB2-K187Q were generated based on a previously established strategy (Hu et al., 2013). The PB2-derived plasmids were sequenced to verify the presence of the introduced mutations and the absence of unwanted mutations based on the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Preparation of samples for mass spectrometry (MS)

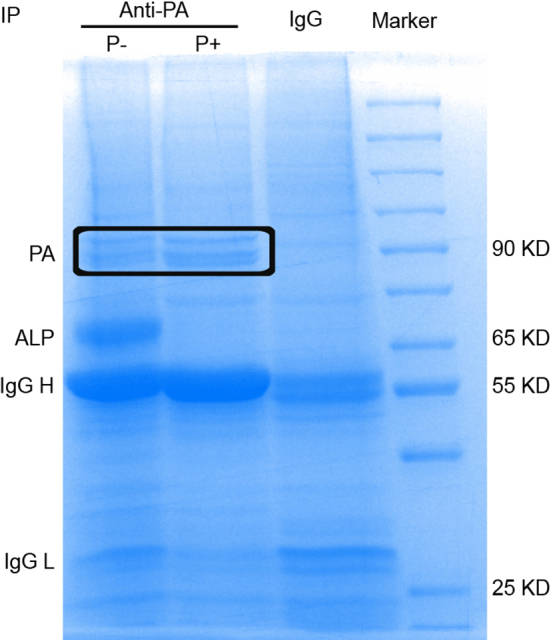

For immunoprecipitation (IP) samples, a total of 3 × 106 HEK 293T cells were transfected with 12 μg of pcDNA-PA-Flag plasmid in which the PA protein was fused with a Flag tag. After 24 h, cells were infected with the CK10 virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2. After 8 h, cells were then lysed in 700 μL RIPA lysis buffer (150 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris pH 7.5, 0.5% w/v sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% w/v SDS, 1% w/v Ipegal 630, 2 mmol/L EDTA). More specifically, RIPA in the control (IgG group) and phosphorylation groups (P+) contained cOmplete™ Mini protease inhibitor (Invitrogen) and phosphatase inhibitor PhosSTOP™ (Invitrogen), while RIPA in the dephosphorylation group (P-) only included the cOmplete™ Mini protease inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. S1). Lysates were sonicated and then cleared via centrifugation at 4 °C (13400 ×g, 10 min). Lysates were incubated with the mouse Flag-tagged antibody and the immune-complexes were captured on Dynabeads Protein A (Invitrogen, CA, USA) for 3 h. Immunoprecipitations were washed five times with RIPA lysis buffer containing 500 mmol/L NaCl and finally in RIPA lysis buffer without BSA. The sample was then subjected to SDT buffer (4% SDS, 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, pH 7.6) for lysis. Protein was quantified by a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). A total of 20 μg of the protein from each sample was mixed with 5 × SDS protein loading buffer and denatured for 5 min. Proteins were then separated on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel. Protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue R-250. Bands circled with boxes were cut for further MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1).

MS was also performed on the purified viral samples inoculated in MDCK cells or embryonated chicken eggs. For MDCK cells, cells were infected with CK10 virus at an MOI of 4 and were then collected at 36 h. To remove the cellular debris and other impurities, the medium was clarified by low-speed centrifugation at 2000 ×g for 30 min, and then 18 000 ×g for 30 min at 4 °C. For further concentration, samples were then layered onto a cushion of 30% sucrose in NTC (100 mmol/L NaCl, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 5 mmol/L CaCl2) and pelleted by ultracentrifugation (112 000 ×g for 90 min at 4 °C in a 32Ti rotor) (Beckman Coulter, Brea, California, USA). Pellets were resuspended in NTC and spun through a 30%–60% sucrose gradient in NTC (209 000 ×g for 150 min at 4 °C in a 41Ti rotor) (Beckman Coulter) to produce the visible band of virus which was drawn off with a needle. To remove sucrose, samples were pelleted through NTC and then centrifuged at 154 000 ×g for 60 min at 4 °C in a 41Ti rotor. Samples were then resuspended in a small volume of NTC. A similar method was used to purify virus collected from infected eggs. Purified viral samples and IP samples were frozen at −80 °C prior to MS analysis.

2.3. LC-MS/MS

Protein digestion was performed by trypsin. The digested peptides of each sample were then desalted on C18 cartridges (Empore™ SPE Cartridges C18, bed I.D. 7 mm, Volume 3 mL) (Invitrogen), concentrated by vacuum centrifugation and reconstituted in 40 μL of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. IMAC enrichment of the phosphopeptides was carried out using a High-SelectTM Fe-NTA Phosphopeptides Enrichment Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After lyophilization, the phosphopeptide peptides were resuspended in 20 μL of loading buffer with 0.1% formic acid.

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) that was coupled to EASY-nLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 120 min. The peptides were then loaded onto a reversed-phase trap column (Thermo Fisher Scientific Acclaim PepMap100, 100 μm × 2 cm, NanoViper C18) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to a C18-reversed phase analytical column (Thermo Fisher Scientific Easy Column, 10 cm long, 75 μm inner diameter, 3 μm resin) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in buffer A with 0.1% formic acid and separated with a linear gradient of buffer B (84% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min controlled by IntelliFlow technology. The MS was operated in positive ion mode. MS data was acquired using a data-dependent top10 method dynamically choosing the most abundant precursor ions from the survey scan (300–1800 m/z) for HCD fragmentation. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to 3e6, and the maximum injection time was set to 10 ms. The dynamic exclusion duration was 40.0 s. Survey scans were acquired at a resolution of 70,000 at m/z 200, and resolution for HCD spectra was set to 17 500 at m/z 200, and the isolation width was 2 m/z. The normalized collision energy was 30 eV, and the underfill ratio, which specifies the minimum percentage of the target value likely to be reached at maximum fill time was defined as 0.1%. The instrument was run with peptide recognition mode enabled. Finally, the MS raw data for each sample were combined and searched using the MaxQuant software for identification and quantitation analysis.

2.4. Amino acid conservation analysis

Amino acid conservation analysis was performed on the sequence available in the NCBI Influenza Virus Resource database. PhyloSuite (https://github.com/dongzhang0725/PhyloSuite/releases) was used for multiple sequence alignment and Jalview (https://www.jalview.org/) was used for the final site conservation analysis.

2.5. Surface accessibility analysis

Surface accessibility analysis of PB2 S181 and PB2 K187 was determined using NetSurfP-3.0 software (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/NetSurfP-3.0/). The calculated relative surface area (RSA) of each residue >25% was scored as accessible.

2.6. Structural modeling of S181 and K187 in the PB2 protein and assembled polymerase complex

For structural modeling of S181 and K187 in the PB2 protein, the amino acid residues at 181 and 187 were mapped onto a ribbon diagram of the structure of PB2 by SWISS-MODEL (SWISS-MODEL.ExPASy.org) using PyMOL software. To understand the position of PB2 S181 and K187 in the assembled polymerase complex, the crystal structures of the polymerase were predicted using SWISS-MODEL (ProMod3 3.3.0). The PDB: 8h69.1 Cryo-EM structure of influenza RNA polymerase was served as the template.

2.7. Determination of the effect of PB2 S181A/E and PB2 K187Q/R mutations on PB2 structure

Protein structure analysis was carried out as described previously (Cazals and Tetley, 2019). Briefly, the wild-type and mutant protein sequences were uploaded into the RoseTTAFold server for protein structure prediction. The predicted structures of the wild-type and mutant proteins were then downloaded into PyMOL software (https://pymol.org/2/) for alignment analysis. A root mean square deviation (RMSD) < 1, indicates that PB2 mimic mutations do not significantly alter the structure of the PB2 protein.

2.8. Stability analysis of the PB2 protein

Human HEK 293T cells were seeded in 35 mm dishes and transfected when they reached approximately 60% confluence. Each dish was transfected with 1 μg of the wild-type or the mutant pcDNA3.1-PB2 expression plasmid using polyfect transfection reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). After 24 h, the cell supernatant was discarded, and 100 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX) was added to each dish. After 0 h of CHX treatment, samples were collected at 1 h intervals thereafter until 4 h. A total of 20 μL of the cleavage product was used for Western blotting analysis.

2.9. Western blotting

Samples were mixed with 5 μL of SDS loading buffer and denatured at 96 °C for 5 min. After separation by 8% SDS-PAGE, samples were then transprinted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and transferred at 150 V for 1 h. After transprinting, samples were then blocked with 5% skim milk (dissolved in TBST containing 0.05% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with rabbit derived PB2, PA, NP and PB1 polyclonal antibodies (GeneTex, San Antonio, USA) at 4 °C overnight. After that, the membranes were then washed 5 times with TBST for 5 min each and subsequently incubated with sheep anti-rabbit HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation with the secondary antibody, membranes were then washed 5 times with TBST for 5 min. Finally, the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ECL) was used to examine of the protein expression.

2.10. Determination of the viral polymerase activity

Human HEK 293T cells were seeded in 24-well cell culture plates for transfection experiments. Then, cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of pcDNA3.1-PA, pcDNA3.1-PB1, pcDNA3.1-NP, wild-type or mutant pcDNA3.1-PB2, firefly luciferase reporter plasmid p-Lucif and 20 ng of the internal reference plasmid pRL-TK using polyfect transfection reagent (Invitrogen). After 24 h, the cell supernatant was discarded and cells were then lysed using the Dual-GLO® Luciferase Assay System Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The fluorescence intensity of the samples was examined on a Promega GloMax multi detection unit using Luciferase assay reagent II (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. Relative luciferase activity presented as the ratio of firefly luciferase/Renilla luciferase was shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments.

2.11. Growth curves of the recombinant viruses

MDCK and DF1 cells seeded into 6-well plates reached 90 % confluence were infected with CK10 virus at an MOI 0.01. After adsorptions at 37 °C for 1 h, the medium was discarded and washed three times with PBS to remove unabsorbed virions and supplemented with 1.5 mL of serum-free, antibiotic-free DMEM. A total of 65 μL of the culture supernatant was collected at 12 h intervals after infection and continued until 72 h. Viral titers were calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (Labarre and Lowy, 2001) and expressed as 50% of the tissue culture infective dose (TCID50).

2.12. Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA)

For IFA, MDCK or DF1 cells grown in 24-well plates were infected with 2 MOI of the CK10 virus. At the indicated time points, cells were fixed with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min and then saturated with in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, and were then incubated with rabbit derived PB2, PB1, PA or NP antibody (GeneTex) overnight at 4 °C. Then, the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with Alexa-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen, CA, USA). After incubation with the secondary antibody, the cellular nucleus was stained with DAPI (4,6-diamino-2-phenyl indole) for 10 min. Cells were observed using a Leica TCS SP-E microscope. Nuclear accumulation of PB2 protein was determined as the ratio of cells showing green fluorescence in the nucleus to the total number of cells counted. For the IFA analysis of the pathology section samples, the upper part of the left mouse lung was fixed in 10% formalin and sliced after pruning, dehydration and embedding. The monoclonal antibody against NP (generated by our lab) was used as the primary antibody.

2.13. Mouse experiment

To evaluate the role of the PB2 S181A/E or PB2 K187Q mutation in the pathogenicity of H5N1 virus in mice, groups of five 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were intranasally (i.n.) inoculated with serial dilutions of viruses (101.0∼105.0 EID50). Animals were monitored daily for mortality over a period of 14 days as previously described (Hu et al., 2015). Animals showing severe disease signs or losing more than 25% of their initial weight were euthanized and recorded as having died on the following day. The mouse 50% lethal dose (MLD50) was calculated using the Reed and Muench method (Labarre and Lowy, 2001).

To investigate viral replication in vivo, groups of six 6-week-old female BALB/c mice were i.n. infected with 105.0 EID50 of the viruses. Three mice from each group were euthanized and the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and brain were collected at days 3 and 5 p.i. for virus titration in eggs. In addition, another group of collected lung tissues was used for determination of cytokine gene expression, histopathological analysis and detection of the NP antigen.

2.14. Histopathological examination of the mouse lung

Histopathological examination was performed as previously described (Sun et al., 2011). Briefly, at day 3 and 5 p.i., the left lung was collected and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and processed for paraffin embedding. Then the tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed for histopathological changes. Images were captured with a Zeiss Axioplan 2IE epifluorescence microscope. Lesion severity in mouse lung was scored according to the following standards: 0, no visible changes; 1, very mild lesions: alveolar capillaries were slightly dilated and congested; few edema fluid was seen in the alveoli and mild alveolar hemorrhage; 2, mild lesions: alveolar capillaries were slightly dilated and congested; moderate edema fluid was seen in the alveoli; mild hemorrhage in perivascular, bronchus, alveolar tube, alveolar sac and alveolar; few lymphocytes infiltration in perivascular, bronchial and alveoli; 3, moderate lesions: alveolar capillaries were dilated and congested; severe edema fluid was seen in the alveoli; hemorrhage in perivascular, bronchus, alveolar tube, alveolar sac and alveolar; moderate epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and inflammatory cells infiltration in perivascular, bronchial and alveoli; 4, severe lesions: alveolar capillaries were dilated and congested; the alveoli were filled with edema fluid; hemorrhage in perivascular, bronchus, alveolar tube, alveolar sac and alveolar; a large number of epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and inflammatory cells infiltration in perivascular, bronchial and alveoli.

2.15. Determination of cytokine expression in mouse lung

To determine cytokine expression, total RNA of the mouse lung was collected using TRIzol (Vazyme) and treated with DNase I (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription reactions were performed with the SYBR Premix ExTaq Kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and qRT-PCRs were performed in triplicate using the ABI Prism 7900 system (Applied Biosystems, CA, US). β-actin mRNA was measured as an endogenous cytoplasmic control. Data were analyzed by normalizing against β-actin using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The specific primer sequences for the cytokines have been listed in Supplementary Table S2.

2.16. Statistical analysis

Results were shown as the mean ± SD. All graphs were performed in Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical analyses were performed using the independent-samples t-test based on SPSS statistics software. For all analyses, P < 0.05 (∗), P < 0.01 (∗∗), P < 0.001 (∗∗∗) or P < 0.0001 (∗∗∗∗) was considered as statistically significant between two groups.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of the phosphorylation and acetylation patterns in viral proteins by LC-MS/MS

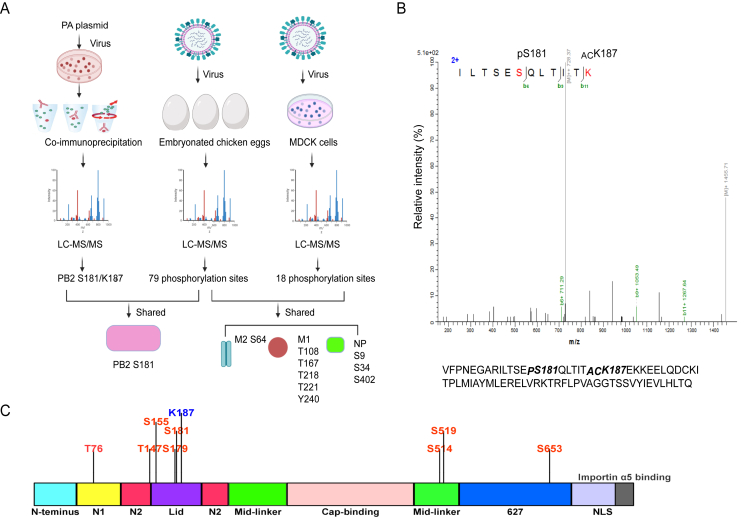

The highly pathogenic H5N1 virus (CK10 strain) was used to systematically identify the phosphorylation and acetylation sites of the viral proteins via IP-based MS and purified virus-coupled MS methods (Fig. 1A). To our great surprise, in the IP-based MS experiment using PA as the targeted protein, no phosphorylation or acetylation sites were detected. However, phosphorylation at S181 and acetylation at K187 of the PB2 protein were detected (Fig. 1B). For the chicken embryo-derived viral samples, a total of 79 phosphorylation sites distributed among eight main encoded proteins were identified, including those on PB1, PB2, PA, NP, M1, M2, NS1 and NEP of IAV, as well as on the accessory proteins PB1-F2 and PA-X (Table 1). In addition, 53 phosphorylation sites were newly identified, including PB2 S181. For the MDCK-derived viral samples, 18 phosphorylation sites located in 7 viral proteins were identified (Table 2), including 11 novel sites. Interestingly, NP S9/S34/S402, M2 S64 and M1 T108/T167/T218/T221/Y240 were also detected in the chicken embryo-derived viral samples (Fig. 1A). Since data concerning phosphorylation and acetylation of the PB2 protein are rare, we focused our analysis on this subunit. A total of 8 phosphorylation sites (T76, T147, S155, S179, S181, S514, S519, S653) and one acetylation site (K187) were identified on PB2 protein (Table 1, Fig. 1A). To the best of our knowledge, currently, none of the acetylation sites have been found on the PB2 protein. Of note, the newly identified phosphorylation site PB2 S181 overlapped between IP-based MS and the chicken egg derived virus-coupled MS method. Then, the potential impact of phosphorylation at each site was proposed based on PB2 structures. As shown in Fig. 1C, these sites were all located in the important area of the PB2 protein. For example, T76 was in the N1-linker domain, T147 was in the N2-linker domain, S514 and S519 were in the middle-linker domain, and S653 was in 627 domains. Others, including S181, K187, S155 and S179 were all located in the Lid domain of the PB2 protein, suggesting that these sites may be involved in protecting the PB1 core domain, and the template and primer channel of PB1 (Elshina and Te Velthuis, 2021). For the subsequent study, we therefore placed high priority on PB2 S181 and PB2 K187.

Fig. 1.

Identification of the PB2 S181 phosphorylation site and K187 acetylation site using IP-based MS and purified virus-coupled MS. A The flow chart for identification of phosphorylation and acetylation sites that located in the H5N1 virus CK10 strain. For the IP samples, a total of 3 × 106 HEK 293T cells were transfected with 12 μg of pcDNA-PA plasmid. After 24 h, cells were infected with 2 MOI of the CK10 virus. After 8 h, cells were lysed for preparation of IP sample using PA as the primary antibody. In addition, MS was also performed on the purified viral samples inoculated in MDCK cells and embryonated chicken eggs. For MDCK cells, cells were infected with CK10 virus at an MOI of 4. B MS analysis results revealed the phosphorylation of PB2 S181 and acetylation of PB2 K187. “P” means the phosphorylation site, while “AC” stands for the acetylation site. C Function analysis of the PB2 phosphorylation sites and PB2 acetylation site K187.

Table 1.

Identified phosphorylation sites of the viral protein from egg-derived viral samples.

| Protein | Identified phosphorylation sites |

|---|---|

| PB1 | Y467, T469, S478a, S673, S678 |

| PB2 | T76, T147, S155, S179, S181, S514, S519, S653 |

| PA | S60, S225, S280, S395, S405 |

| NP | S9, Y10, T15, S34, S69, Y78, S84, S165, S297, T367, T378, T390, S402, S413, T424, T430, T433, S450, S457 |

| M1 | T108, S120, T121, T167, T169, S183, T184, T185, S195, S196, T218, T221, S225, S226, T240 |

| M2 | S2, S64, T65, S71, S82 |

| NEP | S3, T5, S8, S24, S37, S44, S57 |

| NS1 | S2, T9, T49, S64, T65, S71, S73, T81, S82, S130, T186, T192, T220, S223 |

| PB1-F2 | S35 |

Font bold means the phosphorylation sites have been previously reported.

Table 2.

Identified phosphorylation sites of the viral protein from MDCK-derived viral sample.

| Protein | Identified phosphorylation sites |

|---|---|

| PB1 | T201, T204 |

| PA | T173, T177 |

| NP | S9a, S34, Y97, T188、S402 |

| M1 | T108, T167, T218, T221, Y240 |

| M2 | S64 |

| PA-X | T97, T98 |

| PB1-F2 | Y42 |

Font bold means the phosphorylation sites have been previously reported.

3.2. Mutation of the conserved PB2 S181 and PB2 K187 residues does not obviously alter protein structure

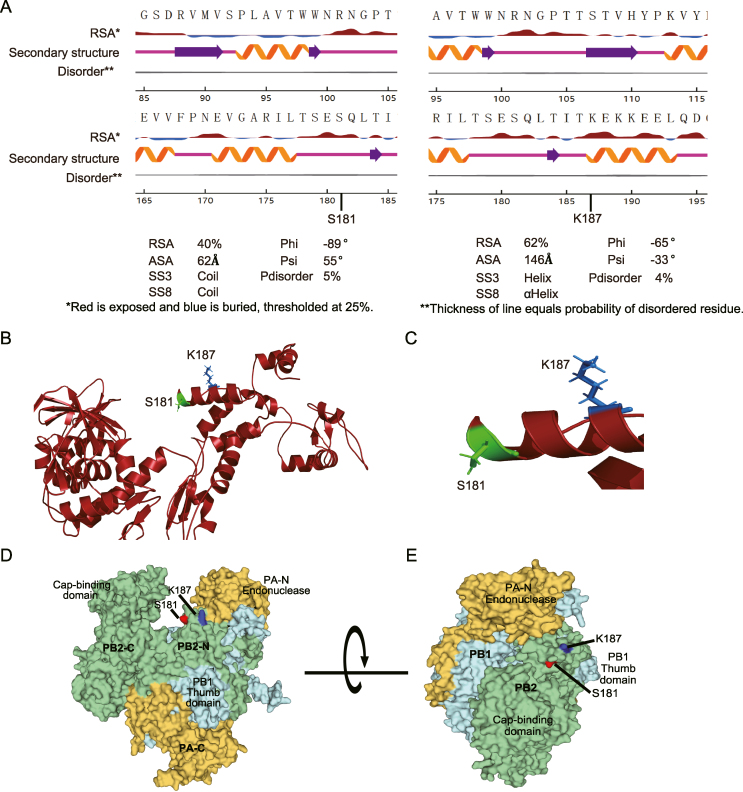

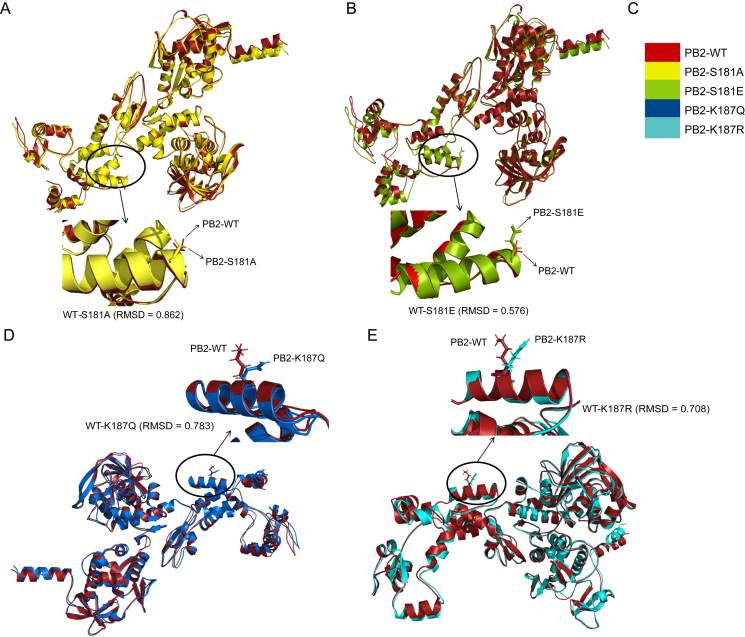

To investigate the conservation of the phosphorylation site PB2 S181 and acetylation site PB2 K187, IAV sequences from H1N1, H3N2, H5, H7N9 and H9N2 subtype viruses were downloaded from the NCBI Influenza Virus Resource database. Multiple sequence alignment analysis results showed that both PB2 S181 (Table 3) and PB2 K187 (Table 4) are highly conserved among various subtypes of IAV, suggesting their fundamental roles in the viral life cycle. To assess whether PB2 S181 and K187 located on the surface the of the PB2 protein, we then analyzed the surface accessibility of these two sites. NetSurfP 3.0 was used to predict the RSA value of these two sites. As a result, the RSA values of PB2 S181 and K187 was 40% and 62%, respectively (Fig. 2A), suggesting that they were both exposed on the surface of the PB2 protein. Since highly accessible residues may be dynamically modified, we hypothesized that PB2 S181 and PB2 K187 may play an important role in regulating IAV infection. Consistent with the RSA value, the three-dimensional (3D) structure analysis of the PB2 protein also revealed that both PB2 S181 and K187 are positioned in obviously accessible locations (Fig. 2B–C). In addition, the sites PB2 S181 and PB2 K187 were close to the PA endonuclease and PB1 thumb domains (Fig. 2D–E), suggesting their potential roles in regulating viral replication. To evaluate the effect of the PB2 S181A/E and K187R/Q mimic mutations on PB2 structure, the structures of the wild-type protein and the mutant PB2 proteins were predicted by RoseTTAFold and PyMOL software (Cazals and Tetley, 2019). As a result, all the mutant proteins could correctly match the wild-type protein, and the RMSD values after matching were all less than 1 (Fig. 3), suggesting that the PB2 S181A/E and K187R/Q mimic modification mutations do not significantly alter the structure of the PB2 protein.

Table 3.

Conservation of PB2 protein phosphorylation site S181 in IAV.

| Subtype | Host | Number of strains | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5 | Any | 5216 | 99.87% |

| Human | 254 | 100% | |

| Avian | 4645 | 99.85% | |

| H9N2 | Any | 2201 | 99.41% |

| Human | 15 | 100% | |

| Avian | 2138 | 99.63% | |

| H3N2 | Any | 23949 | 99.766% |

| Human | 20926 | 99.852% | |

| Avian | 375 | 96.3% | |

| H7N9 | Any | 852 | 99.9% |

| Human | 125 | 99.2% | |

| Avian | 693 | 100% | |

| H1N1 | Any | 18880 | 99.878% |

| Human | 15023 | 99.953% | |

| Avian | 628 | 100% |

Table 4.

Conservation of PB2 protein acetylation site K187 in IAV.

| Subtype | Host | Number of strains | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5 | Any | 5216 | 96.45% |

| Human | 254 | 98.4% | |

| Avian | 4645 | 96.10% | |

| H9N2 | Any | 2201 | 99.41% |

| Human | 15 | 97.68% | |

| Avian | 2138 | 97.66% | |

| H3N2 | Any | 23949 | 99.758% |

| Human | 20926 | 99.885% | |

| Avian | 375 | 96.5% | |

| H7N9 | Any | 852 | 99.9% |

| Human | 125 | 100% | |

| Avian | 693 | 99.3% | |

| H1N1 | Any | 18880 | 97.823% |

| Human | 15023 | 99.794% | |

| Avian | 628 | 97.6% |

Fig. 2.

PB2 S181 and PB2 K187 are exposed on the surface of the PB2 protein. A The surface accessibility analysis of PB2 S181 and K187 using NetSurfP 3.0. The first line plot shows the amino acid letter. The relative surface area (RSA) is shown by a filled curve, threshold at 25% (red exposed, blue buried). The secondary structure is as annotated as Q3 and shows the symbols as a-helix (screw), beta-sheet (arrows), coil (line). The disorder is a grey line in which its thickness is equal to the probability of it being a disordered region. Reported accuracy on test datasets for predicted protein features: relative surface area (RSA), accessible surface area (ASA), secondary structure (SS8 and SS3), protein disorder, and Phi and Psi torsion angles. B The overall 3D-structure analysis of the PB2 protein by SWISS-MODEL (SWISS-MODEL.expasy.org) using the PyMOL software. The position of S181 in PB2 was shown in green, the location of K187 in PB2 was shown in blue. C Enlarged 3D-structure of the PB2 protein indicating the specific location of S181 and K187 in PB2. D–F Determine the position of PB2 S181 and K187 in the assembled polymerase complex. The crystal structures of the polymerase were predicted using SWISS-MODEL Homology Modeling (ProMod3 3.3.0). The PDB: 8h69.1 Cryo-EM structure of influenza RNA polymerase was served as the template.

Fig. 3.

The root mean square deviation (RMSD) analysis between the wild-type PB2 and the mutant PB2 protein. The wild-type and the mutant protein sequences were uploaded into the RoseTTAFold server for protein structure prediction. The predicted structures of the wild-type and the mutant proteins were then downloaded into PyMOL software for alignment analysis. The RMSD <1, means PB2 mimic-modification mutations do not significantly alter the structure of the PB2 protein. A Alignment of the PB2-WT and the mutant PB2-S181A protein. B Alignment of the PB2-WT and the mutant PB2-S181E protein. C Color gradation for each PB2 protein. D Alignment of the PB2-WT and the mutant PB2-K187Q protein. E Alignment of the PB2-WT and the mutant PB2-S181R protein.

3.3. PB2 S181A/E and K187R/Q mutations decrease the stability of the PB2 protein

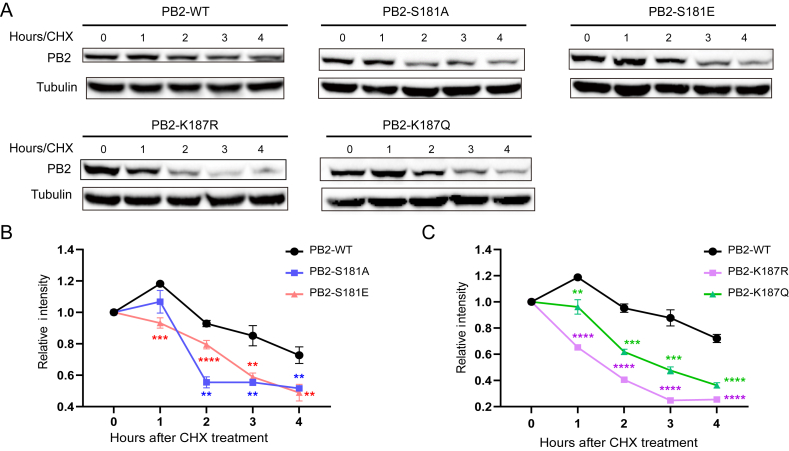

Phosphorylation and acetylation are well known to regulate protein functions, including viral proteins. One effect of these modifications is to regulate protein stability (Zecha et al., 2022). To assess whether PB2 S181A/E and PB2 K187R/Q mimic mutations affect PB2 protein stability, we collected protein samples at different time points after treatment with cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of protein synthesis. As a result, the degradation rate of the wild-type PB2 protein (PB2-WT) was relative slower than that of the mutant proteins (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the degradation rate mediated by continuous phosphorylation mimicked by PB2 S181E mutation was quite similar to that of constant dephosphorylation mimicked by the PB2 S181A mutation (Fig. 4A and B). By contrast, the PB2-K187R mimetic-acetylation mutated protein was degraded more rapidly than the PB2-K187Q mimetic-deacetylation mutant protein (Fig. 4A and C). Therefore, these data suggested that the PB2 S181A/E and PB2 K187R/Q mimic mutations reduced the stability of the PB2 protein, and PB2-K187R mimetic-acetylation showed a more obvious effect.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q/R mimic mutation on PB2 protein stability. Human HEK 293T cells were transfected with 1 μg of wild-type or mutant pcDNA3.1-PB2 expression plasmid. After 24 h, 100 μg/mL of the CHX was added to each dish. After 0 h of CHX treatment, samples were collected at 1 h intervals thereafter until 4 h. Samples were then collected for Western bolting analysis. A Western bolting results of the PB2 protein expression after treat with the CHX. B Relative intensity of the PB2-WT and PB2-S181 E/A mutant protein from panel A. C Relative intensity of the PB2-WT and PB2-S187Q/R mutant protein from panel A. For 4B and 4C, data was shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. For each replicate, PB2 protein levels were normalized to tubulin protein levels.

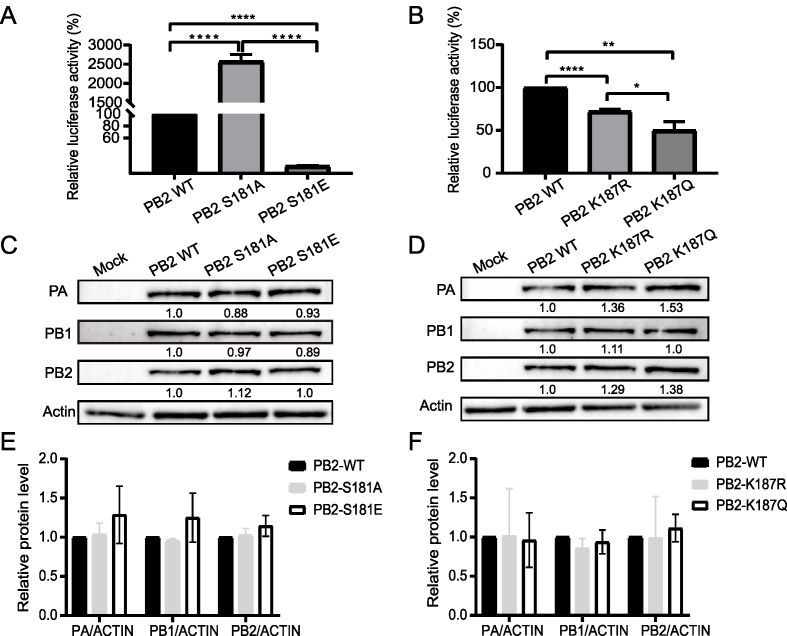

3.4. PB2 S181E attenuates viral polymerase activity and viral replication in mammalian cells

PB2 is a key component of the viral polymerase complex. We then determined whether PB2 S181A/E and K187R/Q mimic mutations affect viral polymerase activity. Compared with the wild-type PB2 protein (PB2-WT), the PB2 S181E phosphorylation mimic mutation markedly attenuated viral polymerase activity, while PB2 S181A dephosphorylation mimic mutation significantly enhanced polymerase activity (Fig. 5A). Both the PB2-K187Q acetylation mimic mutation and the PB2-K187R deacetylation mimic mutation significantly reduced the polymerase activity of PB2-WT to 50% and 72%, respectively (Fig. 5B). Meanwhile, we noticed that PB2 S181A/E or PB2 K187Q/R mimic mutations had no significant effect on the expression of PB2, PA and PB1 proteins in a minigenome assay (Fig. 5C–F), suggesting that other factors may contribute to their altered polymerase activity.

Fig. 5.

Impact of PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q/R mimic mutation on viral polymerase activity. A–B Effect of PB2-S181E/A (A) and PB2-S187Q/R (B) mimic mutation on viral polymerase activities by mini-genome assay. 293T cells were transfected in triplicate with luciferase reporter plasmid p-Luci and internal control plasmid Renilla pRL-TK, together with plasmids expressing PB2, PB1, PA, and NP from CK10 virus or the indicated PB2 mutants. At 24 h p.t., cell lysates were used to measure firefly and Renilla luciferase activities. Values are shown as the means ± SD of the three independent experiments and are standardized to those of PB2-WT (100%). C Determine the expression of viral proteins in panel A by WB. D Determine the expression of viral proteins in panel B by WB. E Calculating the relative expression of the viral proteins in panel C. F Calculation of the relative expression of the viral proteins in panel D. Values in panel E and F are shown as the means ± SD of the three independent experiments and are standardized to those of PB2-WT (1.0).

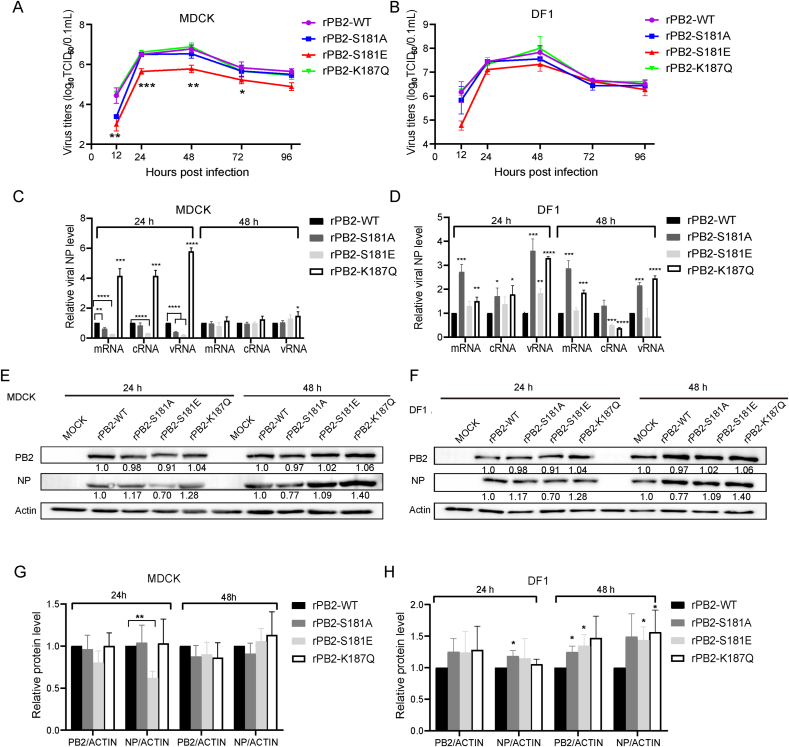

To further investigate the biological relevance of phosphorylation at PB2 S181 and acetylation at PB2 K187, we constructed recombinant CK10 viruses expressing PB2 S181 substitution mutants that mimic constant dephosphorylation (rPB2-S181A) and constitutive phosphorylation (rPB2-S181E), as well as acetylation mimic mutation (rPB2-K187Q) and deacetylation mimic mutation (rPB2-K187R). While the rPB2-S181A, rPB2-S181E and rPB2-K187Q mutants could be rescued, the rPB2-K187R recombinant virus failed to yield virus despite multiple attempts, suggesting that the loss of acetylation on PB2-K187 could not recover the production of infectious virus. All the rescued viruses were then analyzed by a multicycle replication assay in MDCK and DF1 cells. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, in MDCK cells, viral titers of rPB2-S181E were significantly lower than those of rPB2-WT virus at multiple time points, while its viral titers were comparable to those of rPB2-WT virus in avian DF1 cells. By contrast, rPB2-S181A, rPB2-K187Q and rPB2-WT viruses exhibited roughly similar replication kinetics in both MDCK and DF1 cells. Interestingly, when determining the NP mRNA/cRNA/vRNA levels in MDCK cellular precipitation, we noticed that PB2 S181A/E mimic mutations significantly decreased NP mRNA and vRNA levels at 24 h p.i. (Fig. 6C). By contrast, at this time point, the PB2 K187Q mutation significantly enhanced the abundance of all three kinds of NP RNAs. However, only the PB2 S181E phosphorylation mimic mutation significantly attenuated NP protein expression (Fig. 6E and G). As for in DF1 cells, both PB2 S181A and PB2 K187Q mimic mutations significantly increased the amount of three kinds of NP RNAs at 24 h p.i., and markedly enhanced NP mRNA and vRNA levels at 48 h p.i. (Fig. 6D). Correspondingly, in DF1 cells, PB2 S181A significantly elevated the expression of NP (at 24 h p.i.) and PB2 proteins (at 48 h p.i.), and PB2 K187Q obviously enhanced NP expression at 48 h p.i (Fig. 6F and H). Taken together, these results clearly suggested that the PB2 S181E phosphorylation mimic mutation significantly inhibited viral polymerase activity and viral replication in mammalian cells, suggesting that PB2 pS181 may be important for virus replication in mammals.

Fig. 6.

Impact of PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q/R mimic mutation on viral replication in vitro. Cells were inoculated at an MOI of 0.01. Data was shown as the mean ± SD of three independent infections. A–B Effect of PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q mimic mutation on viral replication in MDCK cells (A) and DF-1 cells (B). Virus titers were determined as TCID50 in MDCK cells at the indicated time points. C–D Effect of PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q mimic mutation on NP mRNA/cRNA/vRNA expression in MDCK cells (C), and DF-1 cells (D). E–F Effect of PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q mimic mutation on NP and PB2 protein expression in MDCK cells (E), and DF-1 cells (F). G Calculatiion of the relative expression of the viral proteins in panel E. H Calculating the relative expression of the viral proteins in panel F.

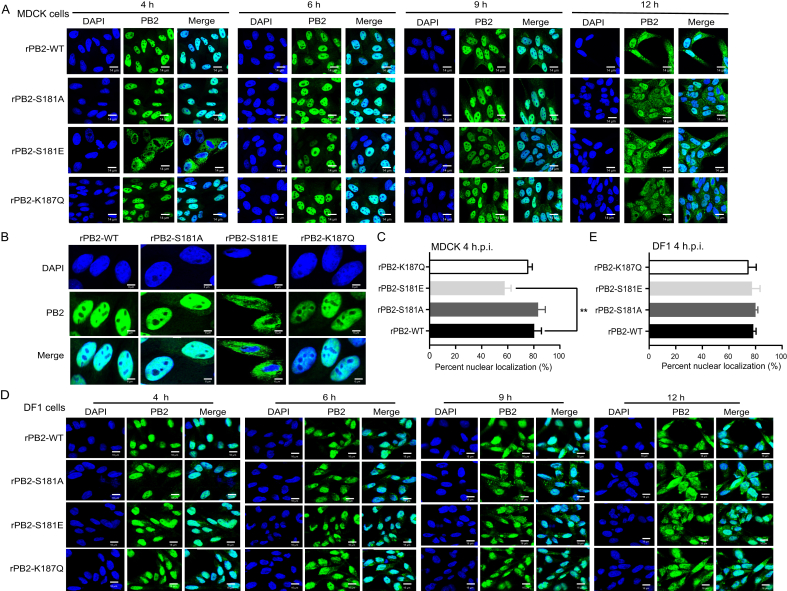

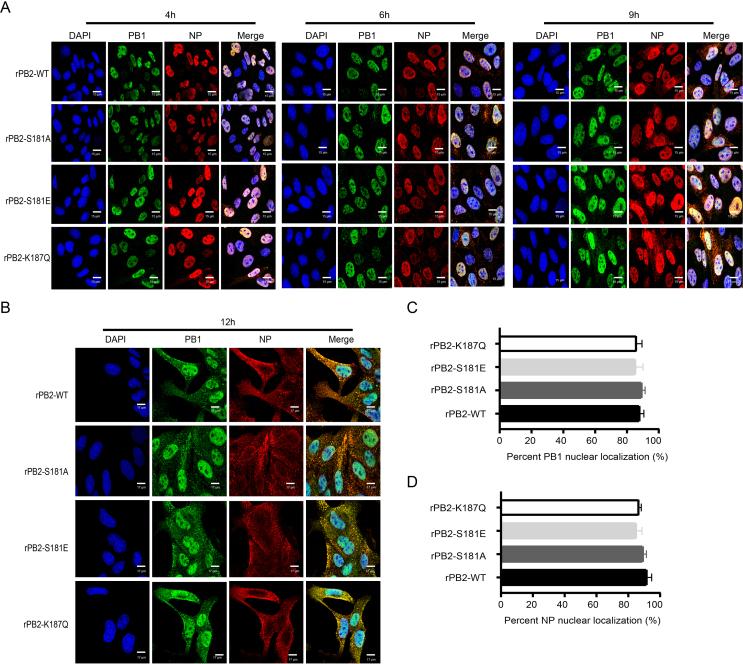

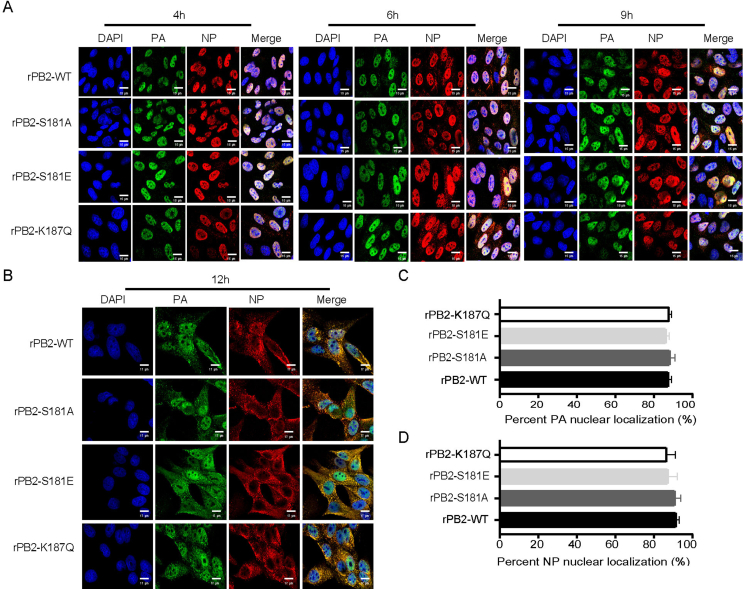

3.5. PB2 S181E inhibits PB2 nuclear accumulation in mammalian cells

The replication assay revealed that PB2 S181E phospho-residues regulate the infectious cycle in MDCK cells. Previous studies have shown that nuclear transportation of viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes is essential for the transcription and replication of IAV (Esparza et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2022). Therefore, we first assessed whether mutations at these sites affect PB2 nuclear accumulation in MDCK cells. Using IFA, we observed distinct difference in PB2 nuclear accumulation between the wild-type virus rPB2-WT and the mutant rPB2-S181E virus. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, during the early detection period, the rPB2-WT and the mutant rPB2-S181E virus clearly varied in PB2 nuclear accumulation. Specifically, rPB2-WT exhibited a faster transportation of the PB2 protein from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, particularly at 4 h p.i.. At this time point, PB2 protein was detected in the nucleus of 70.3% of the rPB2-WT-infected cells, whereas only 36.3% of the rPB2-S181E-infected cells showed PB2 nuclear localization (Fig. 7C). However, after 9 h p.i., the PB2 proteins of these two viruses exhibited comparable abilities to accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. 7A). In stark contrast, rPB2-S181A and rPB2-S187Q viruses showed no obvious differences compared with the wild-type rPB2-WT virus. Of note, PB2 S181E had no impact on the nuclear accumulation of the PB1, PA and NP proteins in MDCK cells (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Fig. S3). We then investigated whether mutations at these sites affect PB2 nuclear accumulation in DF1 cells. However, we found that substitutions at these sites had no obvious effect on PB2 nuclear transportation (Fig. 7D–E). Therefore, these results clearly revealed that mimicking constitutive phosphorylation of PB2 S181 disables virus replication by impairing the nuclear import of the PB2 protein in MDCK cells.

Fig. 7.

Influence of PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q mimic mutation on PB2 nuclear accumulation in MDCK and DF1 cells. MDCK or DF1 cells were infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 2, cell cultures were then fixed and processed for immunofluorescence observation at indicated time points. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. A At 4 h, 6 h, 9 h and 12 h p.i., MDCK cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence observation. Scale bar, 14 μm. B At 4 h p.i., MDCK cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence observation. Scale bar, 6 μm. C At 4 h p.i., the PB2 nuclear accumulation in MDCK-infected cells was determined as the ratio of cells showing green fluorescence in the nucleus to the total number of cells counted (n = 200). D At 4 h, 6 h, 9 h, and 12 h p.i., DF1 cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence observation. Scale bar, 16 μm. E At 4 h p.i., the PB2 nuclear accumulation in DF1-infected cells was determined as the ratio of cells showing green fluorescence in the nucleus to the total number of cells counted (n = 200). Values shown are the means of the results of three independent experiments SDs. ∗, P < 0.05 compared with the result for rPB2-WT virus-infected cells.

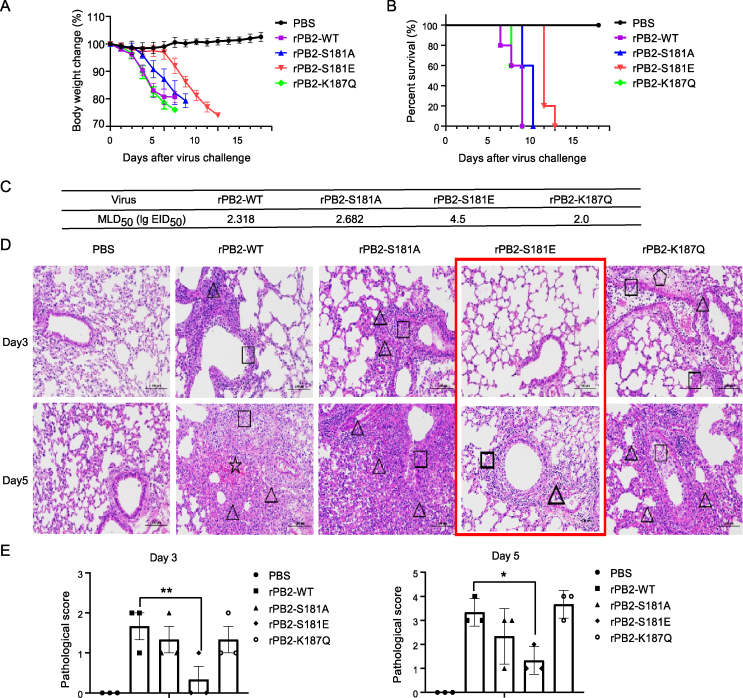

3.6. PB2 S181E decreases viral virulence and the inflammatory response in mice

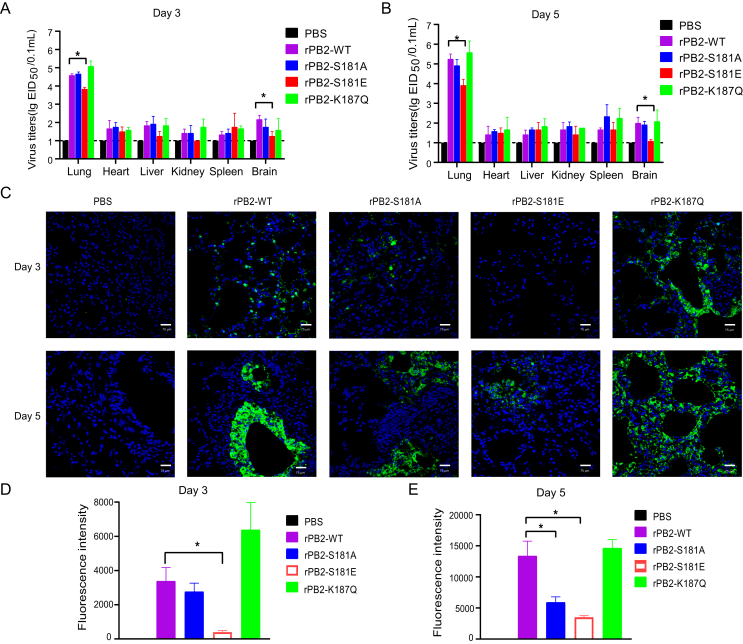

The PB2 gene is one of the important determinants of influenza viral fitness in different hosts. Thus, we next sought to address whether PB2-S181A/E and K187Q mimic mutations affect viral virulence in mice. Mice challenged with the rPB2-WT and the mutant virus all began to lose weight at day 2 post infection (p.i.) (Fig. 8A). Notably, mice infected with the rPB2 S181E mutant virus showed slower weigh loss than those of infected with other viruses. After a 14-day observation period, all virus-infected mice died, while the rPB2 S181E mutant virus infected mice had a longer mean death time (MDT) (Fig. 8B). The MLD50 value indicated that both the PB2-S181E and PB2-S181A mutations decreased viral virulence, with PB2-S181E showed a pronounced decrease (Fig. 8C). By contrast, the PB2-K187Q mutation slightly enhances viral pathogenicity in mice. Consistent with these results, the histopathological analysis results also showed that the PB2-S181E phosphorylation mimic mutation markedly alleviated lung injury in the infected mice both on day 3 and 5 p.i (Fig. 8D and E). The viral load in mouse organs and viral NP fluorescence intensity in mouse lung pathology sections were also determined (Fig. 9). The results showed that the PB2-S181E mutation also significantly restrained viral replication in vivo. More specifically, virus titers in the lungs and brains of mice infected with the rPB2-S181E mutant virus were significantly lower than those of the wild-type rPB2-WT virus both on day 3 and 5 p.i. (Fig. 9A and B). Moreover, the rPB2-S181E virus could not be recovered from the kidneys of rPB2-S181E-infected group on day 3 p.i.. Accompany by this, the fluorescence of the viral NP protein in the mouse lung was significantly weakened in the rPB2-S181E group at day 3 and 5 p.i, and in the rPB2-S181A group at day 5 p.i. (Fig. 9C–E). Altogether, these data clearly revealed that the PB2-S181E phosphorylation mimic mutation significantly inhibits viral replication and virulence in mice.

Fig. 8.

Effect of PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q mimic mutation on viral virulence in mice. A Body weight change of the infected mice challenged with 105.0 EID50 of the CK10 virus. Body weight was presented as percentage of the weight on the day of inoculation (day 0). Mice were humanely killed when they lost >25% of their initial body weight. B Survival rate of the infected mice. Mice were infected with the indicated virus and were observed for 14 days. C MLD50 value of the recombinant and parental viruses. D Histopathology in the mouse lung-infected with the indicated virus in a dose of 105.0 EID50.☆, lung congestion and hemorrhage; □, necrotic detached cells were seen in the bronchiolar lumen; △, lymphocyte infiltration in pulmonary alveoli bronchiolar lumen and around blood vessel;  , pulmonary edema. E Scores of the histopathological changes in the mouse lung on day 3 and 5 p.i..

, pulmonary edema. E Scores of the histopathological changes in the mouse lung on day 3 and 5 p.i..

Fig. 9.

Viral replication in mouse organs. Groups of mice were infected with the indicated recombinant virus. A-B Three mice of each group that infected with 105.0 EID50 of the viruses were euthanized on day 3 and 5 p.i. for determination of viral load in mice organs; C Mouse lung was collected for detection of the NP antigen expression using IFA. Scale bar, 75 μm. D-E The immunofluorescent intensity of the NP antigen from panel C was calculated, day 3 p.i. (D) and day 5 p.i. (E).

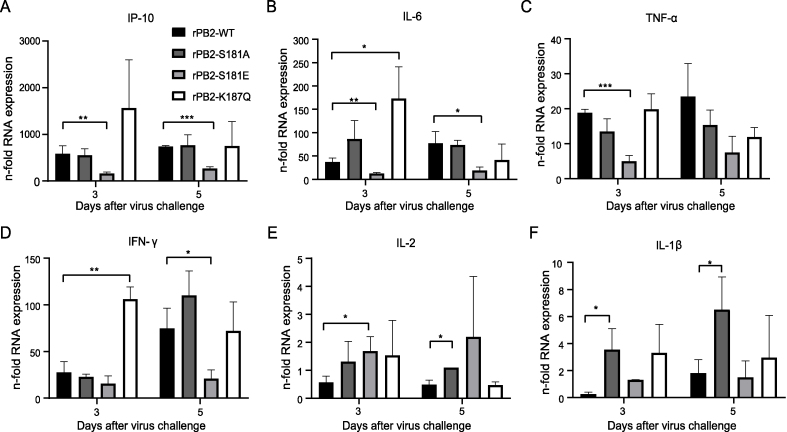

To comprehensively explore the specific impact of phosphorylation and acetylation on viral properties, we then hypothesized whether the PB2 S181A/E and K187Q mimic mutations influence the virus-stimulated innate immune response. The expression of six representative cytokine genes in lungs of mice infected with the indicated recombinant virus was assessed. We found that the PB2-S181E phosphorylation mimic mutation dampens the expression of IP-10, IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ in mouse lung (Fig. 10A–D), while elevating the expression level of IL-2 (Fig. 10E). The PB2 S181A dephosphorylation mutation significantly enhanced the expression of IL-2 and IL-1β (Fig. 10E and F), while the PB2-K187Q acetylation mimic mutation markedly increased IL-6 and IFN-γ expression (Fig. 10B and D). Therefore, these results revealed that the PB2 S181A/E and K187Q mimic mutations play a role in regulating virus-induced inflammatory responses.

Fig. 10.

Impact of the PB2-S181E/A and PB2-S187Q mimic mutation on innate immune response in mouse lung. Groups of mice were infected with the indicated recombinant virus at a dose of 105.0 EID50. Three mice of each group were euthanized on day 3 and 5 p.i. for determination of cytokine responses in mouse lung. The expression of cytokines in mouse lung was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Values were shown as the mean ± SD of three samples.

4. Discussion

Phosphorylation and acetylation of the viral protein play substantial roles in the influenza virus life cycle (Hutchinson et al., 2012; Dawson et al., 2020a, 2020b). The PB2 protein, as an important component of the viral RNP complex, is actively involved in regulating viral fitness in various hosts (Subbarao et al., 1993; Hatta et al., 2001; Long et al., 2016). Current studies concerning the phosphorylation and acetylation of the influenza virus-encoded proteins have mainly focused on viral NP, M1 and NS1 proteins (Dawson et al., 2020a). However, data associated with phosphorylation and acetylation on PB2 protein remain scarce. MS allows for the systemic detection of the PTM patterns of viral proteins. Here, we extensively mapped the phosphorylation patterns throughout the proteomes of IAV and paid close attention to the polymerase subunit PB2 protein. By IP-coupled MS and virion-based MS approaches, 60 novel phosphorylation sites were successfully identified on the H5N1 virus (Table 1, Table 2). Among them, PB2 S181 was consistently identified by both IP-based MS and purified virus-coupled MS methods (Fig. 1A). More importantly, we identified K187 as the first acetylation site located in PB2 protein. By detailed analysis, we uncovered that mimicking the phosphorylation of PB2 S181 markedly attenuates viral replication and viral fitness in mice, while PB2 K181Q mimic acetylation slightly elevates viral virulence in mice.

Despite previous reports of PA protein phosphorylation (Perales et al., 2000; Hutchinson et al., 2012), we failed to detect phosphorylation sites in this protein by IP-coupled MS using PA as the primary antibody. However, we identified the phosphorylation of PB2 S181 in this sample. It is worth mentioning that in the IP-coupled MS method, 293T cells were first transfected with the PA plasmid, followed by infection with the CK10 virus. Moreover, the PB2 S181 phosphorylation site was also detected in the egg-derived viral samples. Therefore, we surmised that PB2 S181 may play an important role in interactions between PA and PB2during IAV infection. Interestingly, by the purified virus-based MS method, for PA protein, five phosphorylation sites (S60, S225, S280, S395, S405) were identified from the egg-derived viral samples, and two phosphorylation sites (T173, T177) were detected in MDCK-derived viral samples (Table 1, Table 2). Therefore, the failure to detect phosphorylated PA protein in the IP-coupled MS method implies that only phosphorylated PA proteins can be packaged into progeny virions. However, this could simply due to a random failure to detect the relevant phosphopeptides in the analyzed samples.

Previously, using virion-based MS, Hutchinson et al. identified 39 phosphorylation sites on 10 viral proteins of the A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus strain (Hutchinson et al., 2012). In this study, based on MDCK cells and chicken embryonated egg-derived viral samples, 89 phosphorylation sites distributed among 10 proteins of the H5N1 virus were successfully identified (Table 1, Table 2). Among them, 10 phosphorylation sites (PB2 S181, M2 S64, M1 T108/T167/T218/T221/Y240, NP S9/S34/S402) were repeatedly detected by different methods in our study (Fig. 1A), indicating their important roles in virus infection. Of particular interest, 29 phosphorylation sites were also previously identified, including PB1 (S478, S673, S678) (Dawson et al., 2020b), PA (S225, S395) (Hutchinson et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2023a), NP (S9, Y10, Y78, S165, T188, S297, T378, S402, S457) (Hutchinson et al., 2012; Mondal et al., 2015; Zheng W.N. et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2019), M1 (T108, T121, T169, S195, S196, S225, S226, Y240) (Hutchinson et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2023b), M2 (S64, T65, S82) (Holsinger et al., 1995; Hutchinson et al., 2012), NEP S24 (Hutchinson et al., 2012; Reuther et al., 2014), NS1 T49 (Kathum et al., 2016), and PB1-F2 (S35, Y42) (Mitzner et al., 2009). The small accessory protein PB1-F2 is also a phosphorylation protein, and the phosphorylation site S35 can efficiently inhibit virus induced-cellular apoptosis during IAV infection (Mitzner et al., 2009). In this study, we also identified PB1-F2 S35 as the phosphorylation site, and another phosphorylation site, Y42, close to S35 (Table 2). We hypothesized that PB1-F2 S35 may also be involved in regulating apoptosis during H5N1 virus infection, while we still need to verify this assumption in future studies. Most importantly, we identified for the first time the occurrence of phosphorylation on another accessory protein, located at sites T97 and T98 of PA-X (Table 2). In addition, the M1 T108 that was repeatedly identified in our study has been previously reported to be essential for virus replication and contributes to M1 polymerization and nuclear localization (Hutchinson et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2023b).

A previous study showed that PB2 is a phosphoprotein, and residue S742 is the phosphorylation site (Hutchinson et al., 2012). In this study, eight phosphorylation sites (T76, T147, S155, S179, S181, S514, S519, S653) and 1 acetylation site (K187) on the PB2 protein were identified (Table 1, Fig. 1A). Notably, the PB2 S181 phosphorylation event was detected in both IP-derived virus samples and chicken embryo-derived virus samples (Fig. 1A, Table 1). In addition, as far as we know, there are no relevant data concerning the acetylation of the PB2 protein. Through functional analysis, we hypothesized that the phosphorylation of PB2 S653 could contribute to the regulation of host adaptation of IAV (Elshina and Te Velthuis, 2021), while PB2 S181 and K187, which are located in the lid domain, might participate in protecting the core domain and the template and primer channel of the PB1 protein (Elshina and Te Velthuis, 2021) (Fig. 1C). Consistent with this finding, we found that the PB2 S181E phosphorylation mimic mutation plays a substantial role in attenuating viral replication both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 6, Fig. 8). The influenza virus polymerase transcribes and replicates the viral genome. The proper timing and balance of polymerase activity is crucial for successful replication. Usually, genome replication is controlled in part by phosphorylation of NP, which regulates assembly of the replication machinery. Here, we provide clear evidence that phosphorylation of PB2 S181E directly disabled polymerase activity and contributed to the subsequent attenuated viral replication.

Surprisingly, patterns of phosphorylation were quite different between viruses grown in MDCK cells and viruses derived from chicken embryonated eggs (Table 1, Table 2), indicating that the hosts in which they were grown are important in determining phosphorylation patterns. From this, it is reasonable to surmise that the phosphorylation sites reported in this study will generally be unique among different hosts. However, due to the stochastic nature of phosphorylation detection by MS, this difference may be attributed to sampling differences rather than differences in phosphorylation patterns. It is established that PB2 E627K is a classical host-adaptive mutation that improves the activity of avian adapted IAV polymerases in mammalian cells (Subbarao et al., 1993; Liu et al., 2023). Here, we found that the PB2-S181E mimic-phosphorylation mutation significantly restrains viral replication in mammalian cells (Fig. 6), suggesting that PB2-pS181 may correlate with viral host tropism. It has been shown that phosphorylation of IAV-encoded proteins can be involved in the regulation of various aspects of viral replication. For example, phosphorylation of M1 Y132 is essential for efficient viral genome incorporation during assembly (Mecate-Zambrano et al., 2020), while mimicking constitutive phosphorylation at PB1 T223 or PB1 S478 inhibits productive RNP formation and disrupts RNA synthesis (Dawson et al., 2020b). In this study, we found that the PB2-S181E mutation significantly reduced protein stability (Fig. 4A and B), attenuated viral polymerase activity (Fig. 5A), and inhibited the nuclear transport of PB2 protein (Fig. 7) in mammalian cells, indicating that the PB2-S181E mutation may be involved in regulating viral replication in mice by affecting these biological properties.

Phosphorylation and acetylation of IAV-encoded proteins can regulate viral replication and pathogenicity in mice (Mecate-Zambrano et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2021). In this study, the PB2-S181E mimic-phosphorylation mutation attenuated the highly pathogenic virus to moderate virulence (MLD50 from 2.318 lg EID50 to 4.5 lg EID50) (Fig. 8C). In addition, the PB2-S181E mutation significantly delayed weight loss and death of the infected mice (Fig. 8A and B), attenuated mouse lung injury (Fig. 8D and E), and restrained viral replication in mice (Fig. 9). By contrast, the PB2 K187Q mimic acetylation mutation slightly enhances viral pathogenicity in mice while has no obvious effect on viral replication in vivo. This suggests that although PB2 K187 acetylation is readily detected in virions, constitutive phosphorylation of this residue is not optimal for viral growth. Interestingly, rapid body weight loss in mice infected with the rPB2-S181E virus was observed starting at day 6 p.i.. Considering that viral replication and lung injury gradually increased in rPB2-S181E virus-infected mice from day 3 to day 5 p.i., we speculated that the sudden weight loss at day 6 p.i. may be a true reflection of the disease process. However, we also cannot exclude the possibility that reverse mutation might have occurred during virus replication in mice. In addition, the PB2-S181E mutation significantly inhibited the expression of IP-10, IL-6, TNF-α and IFN- γ in the mouse lung (Fig. 10A–D), while PB2-K187Q elevated IL-6 and IFN-γ expression (Fig. 10B and D), indicating that PB2 S181 phosphorylation and K187 acetylation are involved in regulating virus-induced innate immune response. However, the specific molecular mechanism accounting for their difference in regulating the response remains to be studied. Previous studies have shown that dephosphorylation of NS1 at Y73 and S83 and phosphorylation of NS1 at T48 decreased the expression of key cytokines of innate immune responses, such as IFN-β, IRF, RIG-I, and ISG56 (Zheng et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2019). Our results further demonstrated that phosphorylation of the IAV-encoded protein may be involved in regulating the innate immune response profile during virus infection.

Our study reveals that constitutive phosphorylation at PB2 S181 plays a more crucial role in the regulation of viral pathogenicity and the biological function of PB2, whereas the phospho-ablative mutant was more well tolerated. This indicates that balanced phosphorylation at this position is important for normal polymerase function. Interestingly, we found that both the PB2-S181A dephosphorylation mutation and PB2-K187Q acetylation mutation reduce PB2 protein stability, and enhance the expression of certain inflammation-related cytokines in the mouse lung. However, the PB2-S181A dephosphorylation mutation slightly attenuates viral replication and pathogenicity in mice, while the PB2-K187Q acetylation mutation mildly enhances viral virulence in mice. Surprisingly, the increased polymerase activity of PB2 S181A does not affect viral production in MDCK cells. Meanwhile, we found that the PB2 S181A mutation markedly downregulated the abundance of NP vRNA/mRNA in MDCK cells (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the PB2-K187Q acetylation mutation also had no effect on viral production in MDCK cells. However, PB2-K187Q decreased viral polymerase activity in 293T cells while increasing NP cRNA/vRNA/mRNA levels in MDCK cells. Quite similar with this, in DF1 cells, PB2 S181A and PB2-K187Q also significantly enhanced NP cRNA/vRNA/mRNA levels and viral protein expression, whereas they had no effect on viral production. Therefore, we speculated that PB2 S181A and PB2-K187Q may be also involved in regulating other steps of the viral life cycle, such as cRNA stabilization, genome packaging, vRNP assembly and transportation, virus budding or viral particle release. However, we also cannot rule out the possibility that the sensitivity of the TCID50 method is much lower than that of WB and qRT-PCR assay. Furthermore, both modified sites lay within the PB2-PA interaction site, and it is also quite interesting to investigate whether efficient polymerase dimerization is dependent on the phosphorylated/acetylated state. Of note, we failed to rescue the rPB2-K187R recombinant virus, suggesting that deacetylation of K187 may be detrimental to the formation of virions. Considering that the cap-binding PB2 protein has key functions in viral transcription and replication (Stevaert and Naesens, 2016; Lo et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2022), loss of acetylation of PB2 K187 may impede important steps of the IAV life cycle and finally result in the failure of virus recovery. It is worth noting that a recent study identified that PB2 K187 is ubiquitinated (Günl et al., 2023). Furthermore, since both PB2 S181 and PB2 K187 are located in close proximity, it is highly possible that phosphorylation may affect acetylation or vice versa. Therefore, further studies systematically dissecting the relevance of ubiquitination, phosphorylation and acetylation to the biological function of these modified sites may gain deeper knowledge of viral replication mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This work represents one of the few studies characterizing the posttranslational modifications of IAV PB2 by generating recombinant viruses carrying mutant phenotype. It highlights the importance of functionally characterizing modifications of viral proteins to attain a detailed understanding of viral replication. It also provides systemic phosphorylation patterns throughout the proteomes of IAV, including 89 phosphorylation sites distributed among eight main encoded proteins as well as in the accessory proteins PB1-F2 and PA-X. Notably, the PB2 S181E mimetic phosphorylation led to significantly decreased viral fitness in mice probably through impairing viral polymerase activity, stability and nuclear-accumulation of PB2 protein. More importantly, for the first time, we successfully identified the first PB2 acetylation site (K187) and proved its role in slightly enhancing viral virulence in mice. Therefore, our study demonstrated that phosphorylation directly regulates viral polymerase activity, and provides a framework for further study of phosphorylation events in virus life cycle.

Data availability

All the data generated during the current study are included in the manuscript.

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China. The protocols for animal experiments were approved by the Jiangsu Administrative Committee for Laboratory Animals (SYXK-SU-2021-0026), and complied with the guidelines of Jiangsu laboratory animal welfare and ethics of Jiangsu Administrative Committee of Laboratory Animals. All experiments involving live viruses and animals were housed in negative-pressure isolators with HEPA filters in a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) animal facilities in accordance with the institutional biosafety manual.

Author contributions

Jiao Hu: conceptualization, writing original draft, writing-review and editing. Zixiong Zeng: data curation, methodology, writing-original draft. Xia Chen and Manyu Zhang: data curation, methodology. Zenglei Hu and Min Gu: methodology, visualization. Xiaoquan Wang and Ruyi Gao: data curation, methodology. Shunlin Hu, Yu Chen, Xiaowen Liu and Daxin Peng: methodology. Xiufan Liu: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing-review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072832, 32372976), by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2021YFD1800202), by Jiangsu Province Agricultural Science & Technology Independent Innovation Funds [CX (21)3141], by the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX22_3553 and KYCX21_3277), by the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-40) and a Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2023.12.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

References

- Agüero M., Monne I., Sánchez A., Zecchin B., Fusaro A., Ruano M.J., Del Valle Arrojo M., Fernández-Antonio R., Souto A.M., Tordable P., Cañás J., Bonfante F., Giussani E., Terregino C., Orejas J.J. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in farmed minks, Spain, October 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023;28 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.3.2300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boergeling Y., Brunotte L., Ludwig S. Dynamic phospho-modification of viral proteins as a crucial regulatory layer of influenza A virus replication and innate immune responses. Biol. Chem. 2021;402:1493–1504. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2021-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazals F., Tetley R. Characterizing molecular flexibility by combining least root mean square deviation measures. Proteins. 2019;87:380–389. doi: 10.1002/prot.25658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Qian Y.J., Chen X., Ruan Z.Y., Ye Y.T., Chen H.J., Babiuk L.A., Jung Y.S., Dai J.J. HDAC6 restricts influenza A virus by deacetylation of the RNA polymerase PA subunit. J. Virol. 2019;93, e01896-18 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01896-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wang C.M., Luo J., Su W., Li M., Zhao N., Lyu W.T., Attaran H., He Y.P., Ding H., He H.X. Histone deacetylase 1 plays an acetylation-independent role in influenza A virus replication. Front. Immunol. 2017;8, 1757 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Shao J., Ying Z., Du Y., Yu Y. Approaches for discovery of small-molecular antivirals targeting to influenza A virus PB2 subunit. Drug Discov. Today. 2022;27:1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Tao J., Li B., Shi Y., Liu H. The tyrosine 73 and serine 83 dephosphorylation of H1N1 swine influenza virus NS1 protein attenuates virus replication and induces high levels of beta interferon. Virol. J. 2019;16:152. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., Zheng W., Li M., Bai X., Yang W., Li J., Fan W., Gao G.F., Sun L., Liu W. Phosphorylation status of tyrosine 78 residue regulates the nuclear export and ubiquitination of influenza A virus nucleoprotein. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1816. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A.R., Wilson G.M., Coon J.J., Mehle A. Post-translation regulation of influenza virus replication. Annu Rev Virol. 2020;7:167–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-010320-070410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A.R., Wilson G.M., Freiberger E.C., Mondal A., Coon J.J., Mehle A. Phosphorylation controls RNA binding and transcription by the influenza virus polymerase. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elshina E., Te Velthuis A.J.W. The influenza virus RNA polymerase as an innate immune agonist and antagonist. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021;78:7237–7256. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03957-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza M., Bhat P., Fontoura B.M. Viral-host interactions during splicing and nuclear export of influenza virus mRNAs. Curr Opin Virol. 2022;55 doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2022.101254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günl F., Krischuns T., Schreiber J., Henschel L., Wahrenburg M., Drexler H., Leidel S., Cojocaru V., Seebohm G., Mellmann A., Schwemmle M., Ludwig S., Brunotte L. The ubiquitination landscape of the influenza A virus polymerase. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:787. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36389-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese S., Ciminski K., Bolte H., Moreira E.A., Lakdawala S., Hu Z.H., David Q., Kolesnikova L., Gotz V., Zhao Y.X., Dengjel J., Chin Y.E., Xu K., Schwemmle M. Role of influenza A virus NP acetylation on viral growth and replication. Nat. Commun. 2017;8, 1259 doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01112-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama D., Shoji M., Ogata S., Masuda T., Nakano M., Komatsu T., Saitoh A., Makiyama K., Tsuneishi H., Miyatake A., Takahira M., Nishikawa E., Ohkubo A., Noda T., Kawaoka Y., Ohtsuki S., Kuzuhara T. Acetylation of the influenza A virus polymerase subunit PA in the N-terminal domain positively regulates its endonuclease activity. FEBS J. 2022;289:231–245. doi: 10.1111/febs.16123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M., Gao P., Halfmann P., Kawaoka Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science. 2001;293:1840–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1062882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsinger L.J., Shaughnessy M.A., Micko A., Pinto L.H., Lamb R.A. Analysis of the posttranslational modifications of the influenza virus M2 protein. J. Virol. 1995;69:1219–1225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1219-1225.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Hu Z., Song Q., Gu M., Liu X., Wang X., Hu S., Chen C., Liu H., Liu W., Chen S., Peng D. The PA-gene-mediated lethal dissemination and excessive innate immune response contribute to the high virulence of H5N1 avian influenza virus in mice. J. Virol. 2013;87:2660–2672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02891-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Mo Y., Wang X., Gu M., Hu Z., Zhong L., Wu Q., Hao X., Hu S., Liu W., Liu H., Liu X., Liu X. PA-X decreases the pathogenicity of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A virus in avian species by inhibiting virus replication and host response. J. Virol. 2015;89:4126–4142. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02132-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson E.C., Denham E.M., Thomas B., Trudgian D.C., Hester S.S., Ridlova G., York A., Turrell L., Fodor E. Mapping the phosphoproteome of influenza A and B viruses by mass spectrometry. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M., Watanabe T., Hatta M., Das S.C., Ozawa M., Shinya K., Zhong G., Hanson A., Katsura H., Watanabe S., Li C., Kawakami E., Yamada S., Kiso M., Suzuki Y., Maher E.A., Neumann G., Kawaoka Y. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature. 2012;486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathum O.A., Schrader T., Anhlan D., Nordhoff C., Liedmann S., Pande A., Mellmann A., Ehrhardt C., Wixler V., Ludwig S. Phosphorylation of influenza A virus NS1 protein at threonine 49 suppresses its interferon antagonistic activity. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:784–791. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating J.A., Striker R. Phosphorylation events during viral infections provide potential therapeutic targets. Rev. Med. Virol. 2012;22:166–181. doi: 10.1002/rmv.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarre D.D., Lowy R.J. Improvements in methods for calculating virus titer estimates from TCID50 and plaque assays. J. Virol Methods. 2001;96:107–126. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(01)00316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Sun L., Zheng W., Madina M., Li J., Bi Y., Wang H., Liu W., Luo T.R. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of threonine 188 in nucleoprotein is crucial for the replication of influenza A virus. Virology. 2018;520:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Guo Y., Zheng H., Ji Z., Cai M., Gao R., Zhang P., Liu X., Xu X., Wang X., Liu X. Enhanced pathogenicity and transmissibility of H9N2 avian influenza virus in mammals by hemagglutinin mutations combined with PB2-627K. Virol. Sin. 2023;38:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Madhugiri R., Saul V.V., Bacher S., Kracht M., Pleschka S., Schmitz M.L. Phosphorylation of the PA subunit of influenza polymerase at Y393 prevents binding of the 5'-termini of RNA and polymerase function. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:7042. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-34285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Weber A., Linne U., Shehata M., Pleschka S., Kracht M., Schmitz M.L. Phosphorylation of influenza A virus matrix protein 1 at threonine 108 controls its multimerization state and functional association with the STRIPAK complex. mBio. 2023;14 doi: 10.1128/mbio.03231-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C.Y., Tang Y.S., Shaw P.C. Structure and function of influenza virus ribonucleoprotein. Subcell. Biochem. 2018;88:95–128. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8456-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J.S., Giotis E.S., Moncorge O., Frise R., Mistry B., James J., Morisson M., Iqbal M., Vignal A., Skinner M.A., Barclay W.S. Species difference in ANP32A underlies influenza A virus polymerase host restriction. Nature. 2016;529:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature16474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.J., Wu R.J., Xu G.L., Cheng Y.Q., Wang Z.F., Wang H.A., Yan Y.X., Li J.X., Sun J.H. Vet Res. 51, 20. 2020. (Acetylation at K108 of the NS1 Protein Is Important for the Replication and Virulence of Influenza Virus). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecate-Zambrano A., Sukumar S., Seebohm G., Ciminski K., Schreiber A., Anhlan D., Greune L., Wixler L., Grothe S., Stein N.C., Schmidt M.A., Langer K., Schwemmle M., Shi T., Ludwig S., Boergeling Y. Discrete spatio-temporal regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation directs influenza A virus M1 protein towards its function in virion assembly. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzner D., Dudek S.E., Studtrucker N., Anhlan D., Mazur I., Wissing J., Jansch L., Wixler L., Bruns K., Sharma A., Wray V., Henklein P., Ludwig S., Schubert U. Phosphorylation of the influenza A virus protein PB1-F2 by PKC is crucial for apoptosis promoting functions in monocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1502–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal A., Potts G.K., Dawson A.R., Coon J.J., Mehle A. Phosphorylation at the homotypic interface regulates nucleoprotein oligomerization and assembly of the influenza virus replication machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K., Yamayoshi S., Kozuka-Hata H., Oyama M., Kawaoka Y. N-terminal acetylation by NatB is required for the shutoff activity of influenza A virus PA-X. Cell Rep. 2018;24:851–860. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A., Anhlan D., Ferrando V., Mecate-Zambrano A., Mellmann A., Wixler V., Boergeling Y., Ludwig S. Phosphorylation of influenza A virus NS1 at serine 205 mediates its viral polymerase-enhancing function. J. Virol. 2021;95, e02369-20 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02369-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales B., Sanz-Ezquerro J.J., Gastaminza P., Ortega J., Santaren J.F., Ortin J., Nieto A. The replication activity of influenza virus polymerase is linked to the capacity of the PA subunit to induce proteolysis. J. Virol. 2000;74:1307–1312. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1307-1312.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puryear W., Sawatzki K., Hill N., Foss A., Stone J.J., Doughty L., Walk D., Gilbert K., Murray M., Cox E., Patel P., Mertz Z., Ellis S., Taylor J., Fauquier D., Smith A., Digiovanni R.A., Jr., Van De Guchte A., Gonzalez-Reiche A.S., Khalil Z., Van Bakel H., Torchetti M.K., Lantz K., Lenoch J.B., Runstadler J. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus outbreak in new england seals, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023;29:786–791. doi: 10.3201/eid2904.221538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther P., Giese S., Gotz V., Riegger D., Schwemmle M. Phosphorylation of highly conserved serine residues in the influenza A virus nuclear export protein NEP plays a minor role in viral growth in human cells and mice. J. Virol. 2014;88:7668–7673. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00854-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shvedunova M., Akhtar A. Modulation of cellular processes by histone and non-histone protein acetylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022;23:329–349. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00441-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevaert A., Naesens L. The influenza virus polymerase complex: an update on its structure, functions, and significance for antiviral drug design. Med. Res. Rev. 2016;36:1127–1173. doi: 10.1002/med.21401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao E.K., London W., Murphy B.R. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol. 1993;67:1761–1764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1761-1764.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Qin K., Wang J., Pu J., Tang Q., Hu Y., Bi Y., Zhao X., Yang H., Shu Y., Liu J. High genetic compatibility and increased pathogenicity of reassortants derived from avian H9N2 and pandemic H1N1/2009 influenza viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:4164–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019109108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrell L., Hutchinson E.C., Vreede F.T., Fodor E. Regulation of influenza A virus nucleoprotein oligomerization by phosphorylation. J. Virol. 2015;89:1452–1455. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02332-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Qu R., Zong Y., Qin C., Liu L., Gao X., Sun H., Sun Y., Chang K.C., Zhang R., Liu J., Pu J. Enhanced stability of M1 protein mediated by a phospho-resistant mutation promotes the replication of prevailing avian influenza virus in mammals. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zhao Z., Bi Y., Sun L., Liu X., Liu W. Tyrosine 132 phosphorylation of influenza A virus M1 protein is crucial for virus replication by controlling the nuclear import of M1. J. Virol. 2013;87:6182–6191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03024-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A., Dam S., Saul V.V., Kuznetsova I., Muller C., Fritz-Wolf K., Becker K., Linne U., Gu H., Stokes M.P., Pleschka S., Kracht M., Schmitz M.L. Phosphoproteome analysis of cells infected with adapted and nonadapted influenza A virus reveals novel pro- and antiviral signaling networks. J. Virol. 2019;93, e00528-19 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00528-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]