Abstract

The increase in the number of stroke patients in China brain has led to the decline in quality of life and the burden of family economic conditions. This study explored the relationship between stroke and physical activity (PA) in middle-aged and elderly Chinese after controlling Demography, health status and lifestyle variables, providing a new basis for the prevention and treatment of stroke in the elderly. The data is from the 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal study. Five thousand seventy people over 50 years old with complete information on PA, stroke, Demography, health status and lifestyle were included in the analysis. SPSS 27.0 software was used to conduct Z test, logistic regression analysis and linear hierarchical regression analysis on the collected data.

The results showed that high-level physical exercise was significantly negatively correlated with stroke (P < .05). After adjusting Demographics characteristics (gender, registered residence type, education level, age, widowhood or not), health status characteristics and living habits (arthritis, bad mood, asthma, hyperlipidemia, disability, memory disease, health self-evaluation, hypertension, smoking, depression), There was still statistical significance (P < .05) between PA and stroke. This study concludes that middle-aged and elderly people with high PA have a lower risk of stroke. In the process of preventing and improving stroke symptoms in the elderly, it is important to maintain high PA while also paying attention to health management and a healthy lifestyle.

Keywords: middle-aged and elderly people, physical activity, relationship, stroke

1. Introduction

In the past 10 years, China’s economy has developed at a high speed, the level of medical and health care has been significantly improved, and health education has been gradually strengthened, but it is disappointing that the incidence of stroke has not been reduced.[1] The incidence of stroke in China ranks first in the world. In 2020, the number of stroke patients in China increased by 2.5 million, and about 1.5 million stroke patients died.[2] Stroke may lead to permanent physical dysfunction, such as hemiplegia, language impairment, vision and hearing impairment.[3] Stroke patients may need long-term care from others, which may have a serious impact on their quality of life.[4] Stroke may lead to the increase of long-term medical expenses, which will put pressure on the economic status of families and individuals.[5–7] Research shows that one of the important reasons for the rise of stroke prevalence is due to the growing population and aging.[8] Risk factors of stroke also include metabolic factors (hypertension, body mass index, high blood sugar, etc), behavioral factors (smoking, bad eating habits, lack of physical activity [PA], etc) and environmental risks (air pollution, etc.).[9–12] Many risks of stroke can be changed. Regular PA is beneficial to reduce the risk of premature death and cardiovascular disease.[13] A study concluded that moderate and high levels of PA were associated with a reduced risk of total stroke, ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke.[14] Another study showed that high and medium levels of PA have beneficial effects on cardiovascular health, which can reduce the risk of stroke by 30% and 20% in men and women.[15] A study has shown that PA can improve cardiovascular adaptability, improve vascular elasticity, promote blood circulation, lower blood pressure and heart rate, and thus reduce the incidence of stroke.[16] A study shows that PA can reduce the inflammatory reaction in the body, which is closely related to atherosclerosis and stroke.[17] A study shows that PA can reduce the inflammatory reaction in the body, which is closely related to atherosclerosis and stroke.[18] However, there is limited research evidence on the relationship between PA and stroke risk, and the scientific quality of each study varies. Therefore, it is necessary to further explore the relationship between PA and stroke risk. Moreover, there is relatively little research on the impact of demographic variables, health status, and lifestyle variables on the relationship between PA and stroke. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze the correlation between stroke risk and PA in middle-aged and elderly people, and the correlation between stroke risk and PA in middle-aged and elderly people after controlling for demographic variables, health status, and lifestyle variables.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and data

At Peking University in China, a big interdisciplinary survey project known as China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) is being conducted.[19] The goal of the study is to gather information on demographic traits, physical and mental health, personal and family economic status, medical services, and insurance of middle-aged and elderly people in China who are 45 years of age and older in order to analyze the aging of the population there and advance interdisciplinary aging research. CHARLS employs the multi-stage probability scale proportional sampling technique, which includes sampling at the county (district), village (resident), home, and individual levels. In our research, CHARLS 2018 data were used. All of the information obtained during CHARLS is stored in the CHARLS database at Peking University in China. All information is available at http://charls.pku.edu.cn. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Anshan Normal University, China.

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Demographic, health and lifestyle variables.

The participants Demography, health status and lifestyle variables were obtained through the self-made scale. Demography variables include gender (male or female), age (50–59 years old, 60–69 years old, 70–79 years old, 80–89 years old, and 90 years old and above), registered residence type (urban or rural), education level (lower than high school or higher education) and widowhood (yes or no). The variables of health status include whether there is arthritis, hypertension, disability, asthma, self-assessed health status (good or bad), memory difficulties (yes or no), diabetes (yes or no), hyperlipidemia (yes or no), depression (yes or no) and negative emotions (yes or no). Lifestyle variables include walking ability (good or bad) and smoking (yes or no).

2.2.2. Physical activities.

According to the survey, middle-aged and elderly people often engage in manual labor-intensive activities, including farming, mining, and handling large items. Sweeping the floor, practicing Tai Chi, and taking walks are several examples of low intensity sports activities. Then calculate the duration and days of physical exercise for each participant for at least 10 minutes. The time division for each PA is as follows: 0.5 hours, > 0.5 hours but 2 hours, > 2 hours but 4 hours, and > 4 hours. The International PA Questionnaire is used to determine PA levels.[20,21]

2.2.3. Stroke.

A questionnaire survey was conducted to investigate whether participants had been diagnosed with stroke through brain CT in the past year.

2.3. Statistical analysis

First, describe statistically each of the mentioned variables. Finding stroke and PA risk variables using multivariate logistic regression analysis. A multi-level linear regression analysis was carried out using the likelihood of stroke as the dependent variable and the level of PA as the independent variable to assess the correlation between PA and stroke likelihood. Model 1 was used to derive the P values for PA and stroke. Model 2 uses Model 1 to predict demographic factors such registered resident status, educational attainment, gender, age, and widowhood. Based on Model 2, Model 3 predicts health and lifestyle factors (such as smoking, unfavorable emotions, asthma, hypertension, disability, and arthritis) as well as self-rated health, hyperlipidemia, and depression. For all statistical analyses, P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristic

A total of 5070 middle-aged and elderly people over the age of 50 were included in this study. There were 2502 males (49.3%) and 2568 females (50.7%). There was no significant difference in gender (P = .345). In terms of stroke symptoms, the proportion of middle-aged and elderly people with stroke was 6.4%. The proportion of middle-aged and elderly people with high PA was 47.4%, and the proportion of middle-aged and elderly people with low PA was 52.6%. There was no significant difference in PA between them (P = .276). The proportion of middle-aged and elderly participants aged 50 to 59, 60 to 69, 70 to 79, 80 to 89, 90, and above was 5.4% (276), 18.2% (924), 38.2% (1935), 31.8% (1611), and 6.4% (324), respectively. In terms of household registration types, rural household accounts accounted for 77.3% (4919 people), and urban household accounts accounted for 22.7% (1151 people). In terms of education level, high school and above accounted for 18.5% (934 people), and junior high school and below accounted for 81.5% (4127 people). The number of widowed participants accounted for 11.8% (599). The proportion of participants with good self-rated health status was 24.5% (1241). The number of participants with disabilities accounted for 3.6% (185). In terms of chronic diseases, participants with hypertension accounted for 11.9% (601), participants with diabetes accounted for 6.7% (339), participants with asthma accounted for 1.7% (88), and participants with arthritis accounted for 7.0% (357). Participants with smoking habits accounted for 25.8% (1307), 1.0% (51), 2.5% (127), 34.7% (1760), and 78.3 (3972) were able to walk for 1 kilometer. Except for gender and PA, there were significant differences in Z test results among other variables of participants (P < .05) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of middle-aged and elderly participants of the CHARLS in 2018.

| Number of participants | % | Z | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 2502 | 49.3% | ||

| Female | 2568 | 50.7% | 0.927 | .354 | |

| Age (yr) | 50–59 | 276 | 5.4% | ||

| 60–69 | 924 | 18.2% | |||

| 70–79 | 1935 | 38.2% | |||

| 80–89 | 1611 | 31.8% | |||

| ≥90 | 324 | 6.4% | −62.103 | .000 | |

| Location of residence | City | 1151 | 22.7% | ||

| Rural | 3919 | 77.3% | 38.874 | .000 | |

| Degree of education | Junior high school and below | 4127 | 81.4% | ||

| High school and above | 934 | 18.6% | −44.717 | .000 | |

| Widowed | Yes | 599 | 11.8% | ||

| No | 4471 | 88.2% | 54.379 | .000 | |

| Self-rated health status | Good | 1241 | 24.5% | ||

| Bad | 3829 | 75.5% | 36.346 | .000 | |

| Physical disability | Yes | 185 | 3.6% | ||

| No | 4885 | 96.4% | 66.008 | .000 | |

| Hypertension | Yes | 601 | 11.9% | ||

| No | 4469 | 88.1% | 54.323 | .000 | |

| Diabetes | Yes | 339 | 6.7% | ||

| No | 4431 | 93.3% | 61.682 | .000 | |

| Stroke | Yes | 332 | 6.4% | ||

| No | 4747 | 93.6% | 62.131 | .000 | |

| Bad mood | Yes | 51 | 1.0% | ||

| No | 5019 | 99.0% | 69.750 | .000 | |

| Memory disease | Yes | 127 | 2.5% | ||

| No | 4939 | 97.5% | 67.607 | .000 | |

| Arthritis | Yes | 357 | 7.0% | ||

| No | 4707 | 93.0% | 61.128 | .000 | |

| Asthma | Yes | 88 | 1.7% | ||

| No | 4976 | 98.3% | 68.689 | .000 | |

| Smoke | Yes | 1307 | 25.8% | ||

| No | 3763 | 74.2% | 3.680 | .000 | |

| Walk one kilometer | Yes | 3972 | 78.3% | ||

| No | 1098 | 21.7% | 34.492 | .000 | |

| Depression | Yes | 1760 | 34.7% | .000 | |

| No | 3370 | 65.3% | −40.363 | ||

| Physical activity | High | 2404 | 47.4% | ||

| Low | 2666 | 52.6% | 21.768 | .276 | |

CHARLS = China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study.

Figure 1.

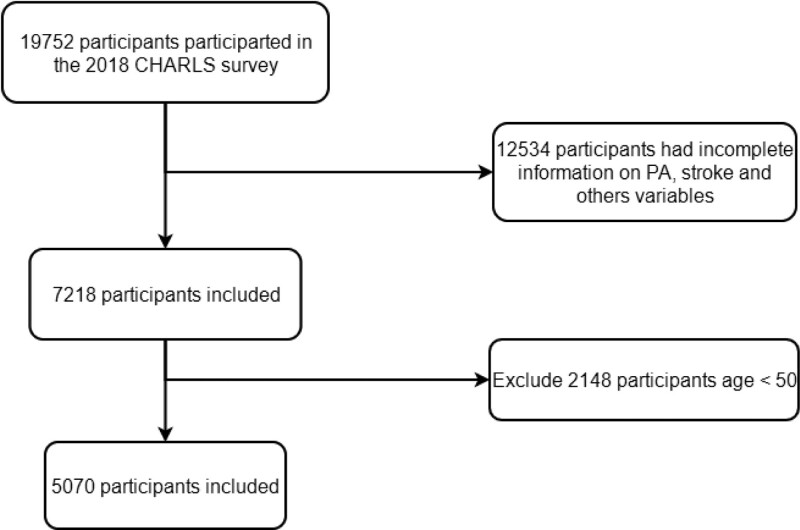

The 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which had 7552 participants overall, removed 12,534 individuals due to missing data on stroke, physical activity, and other factors, leaving just 7218 participants. Because they were under 50 years old, 2148 persons were left out of the 8861 group. Finally, the study’s final 5070 participants were included.

3.2. Analysis of influencing factors of PA

Age, disability, diabetes, stroke, bad mood, memory disease, arthritis, smoking, walking 1 kilometer, depression, and PA of participants were statistically significant (P < .05). As age increases, the PA level of middle-aged and elderly people decreases. In terms of health status, participants with disabilities, stroke, diabetes and arthritis had low levels of PA. In terms of mental health and PA, participants with poor emotions and depression have lower levels of PA. In terms of lifestyle habits, participants with smoking habits and the ability to walk 1 kilometer had lower levels of PA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Influencing factors of physical activity among middle-aged and elderly participants in CHARLS in 2018.

| Physical activity | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| High | Gender | −.120 | .067 | 3.261 | .071 | .887 | .778 | 1.010 |

| Age (yr) | −.351 | .138 | 6.423 | .011 | .704 | .537 | .924 | |

| Location of residence | −.007 | .084 | .007 | .931 | .993 | .843 | 1.170 | |

| Degree of education | −.160 | .084 | 3.604 | .058 | .852 | .723 | 1.005 | |

| Widowed | −.095 | .105 | .824 | .364 | .909 | .741 | 1.116 | |

| Self-rated health status | .086 | .075 | 1.301 | .254 | 1.090 | .940 | 1.263 | |

| Physical disability | −.684 | .185 | 13.686 | .000 | .504 | .351 | .725 | |

| Hypertension | −.190 | .105 | 3.286 | .070 | .827 | .673 | 1.016 | |

| Diabetes | −4.296 | .455 | 89.268 | .000 | .014 | .006 | .033 | |

| Stroke | −.804 | .152 | 28.155 | .000 | .447 | .332 | .602 | |

| Bad mood | −.701 | .350 | 4.010 | .045 | .496 | .250 | .985 | |

| Memory disease | −.485 | .244 | 3.937 | .047 | .616 | .382 | .994 | |

| Arthritis | .338 | .125 | 7.358 | .007 | 1.402 | 1.098 | 1.791 | |

| Asthma | −.037 | .258 | .021 | .886 | .964 | .581 | 1.598 | |

| Smoke | .309 | .076 | 16.592 | .000 | 1.363 | 1.174 | 1.581 | |

| Walk one kilometer | .600 | .086 | 48.622 | .000 | 1.822 | 1.539 | 2.156 | |

| Depression | −1.720 | .074 | 535.262 | .000 | .179 | .155 | .207 | |

CHARLS = China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

3.3. Analysis of influencing factors of stroke

There were significant differences between participants education level, self-rated health status, disability, hyperlipidemia, memory disease, arthritis, asthma, walking for 1 kilometer, and PA and stroke (P < .05). The lower the level of education, the higher the risk of stroke. In terms of health status, the middle-aged and elderly people with worse self-rated health status are more likely to suffer from stroke; Middle-aged and elderly participants with disabilities, hypertension, memory diseases, arthritis and asthma are more likely to suffer from stroke. Middle-aged and elderly people with poor walking ability and low level of PA are more likely to suffer from stroke (Table 3).

Table 3.

Influencing factors of stroke among middle-aged and elderly participants in CHARLS in 2018.

| Stroke | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Ye | Gender | −.048 | .128 | .141 | .707 | .953 | .741 | 1.225 |

| Age (yr) | .470 | .353 | 1.778 | .182 | 1.600 | .802 | 3.195 | |

| Location of residence | .185 | .160 | 1.340 | .247 | 1.203 | .880 | 1.644 | |

| Degree of education | −.358 | .159 | 5.088 | .024 | .699 | .513 | .954 | |

| Widowed | .305 | .182 | 2.799 | .094 | 1.356 | .949 | 1.938 | |

| Self-rated health status | −1.399 | .250 | 31.410 | .000 | .247 | .151 | .403 | |

| Physical disability | 1.351 | .203 | 44.264 | .000 | 3.862 | 2.594 | 5.750 | |

| Hypertension | .232 | .165 | 1.973 | .000 | 2.939 | 1.786 | 3.206 | |

| Diabetes | −.001 | .205 | .000 | .994 | .999 | .669 | 1.491 | |

| Bad mood | −.802 | .561 | 2.039 | .153 | .449 | .149 | 1.348 | |

| Memory disease | 1.606 | .221 | 52.574 | .000 | 4.981 | 3.227 | 7.687 | |

| Arthritis | .453 | .203 | 4.996 | .025 | 1.573 | 1.057 | 2.340 | |

| Asthma | .953 | .323 | 8.698 | .003 | 2.593 | 1.377 | 4.883 | |

| Smoke | .273 | .141 | 3.740 | .053 | 1.314 | .996 | 1.732 | |

| Walk one kilometer | −.706 | .137 | 26.588 | .000 | .494 | .378 | .646 | |

| Depression | −.018 | .141 | .016 | .899 | .982 | .745 | 1.295 | |

| Physical activity | −.766 | .150 | 26.085 | .000 | .465 | .346 | .624 | |

CHARLS = China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

3.4. Linear hierarchical regression model of Stroke and PA level of participants

Model 1 shows that there is statistical significance between the amount of PA and stroke (P < .05). Model 2 adjusts the Demography characteristic variables (gender, household registration type, education level, age, widowhood or not) on the basis of the amount of PA, and the results also have statistical significance (P < .05). After adjusting the health status characteristics and lifestyle habits (arthritis, emotional distress, asthma, disability, memory disorders, health self-assessment, hypertension, smoking, depression) on the basis of Model 2, Model 3 still showed statistical significance (P < .05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Linear hierarchical regression model of stroke and physical activity level of participants.

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Variation statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F variation | P value | ||||

| 1 | .117* | .014 | .014 | 70.660 | .000 |

| 2 | .128† | .016 | .015 | 13.908 | .000 |

| 3 | .297‡ | .088 | .085 | 25.650 | .000 |

Predicted variable: physical activity

Predicted variables: physical activity, gender, household registration type, education level, age, widowhood.

Predicted variables: physical activity, household registration type, education level, gender, age, widowhood, arthritis, poor mood, asthma, disability, memory disease, self-assessment of health, hypertension, smoking, depression.

4. Discussion

This study used a logistic regression model and a linear stratified regression model to analyze the relationship between stroke and PA levels in middle-aged and elderly people over 50 years old (P < .05), After adjusting Demography characteristics (gender, age, household registration type, education level, widowhood) and health status characteristics and living habits (arthritis, bad mood, asthma, hyperlipidemia, disability, memory disease, health self-assessment, hypertension, smoking, depression), there was still statistical significance (P < .05). Overall, our research results show that the proportion of stroke among middle-aged and elderly people over 50 years old is 6.4%; 47.4% of middle-aged and elderly people over 50 years old have high levels of PA, while 52.6% have low levels. The number of stroke cases in middle-aged and elderly people with high levels of PA is significantly lower than that with low levels of PA, indicating an inverse relationship between high PA and stroke subtypes in the elderly. This result is supported by a previous study conducted by CJ MacDonald et al[22] They included women who did not have cardiovascular disease or cancer at baseline. The results were 94,169 women with an average age of 51.2 years, and 592 stroke patients were found during an average follow-up period of 16.2 years. The study concluded that there was an inverse relationship between PA and all stroke subtypes. Hu Frank B et al[23] conducted a study to analyze the relationship between PA and women’s total stroke and stroke subtype risk. A total of 72,488 female nurses, aged between 40 and 65 years, were enrolled in the study. No cardiovascular disease or cancer was diagnosed at baseline. Main outcome measures stroke events after baseline, and the level of PA measured by metabolic equivalent task. It was found that brisk or stride walking was associated with a lower risk of total ischemic stroke than average or random walking. These data suggest that PA, including moderate intensity exercise, such as walking, can significantly reduce the risk of total stroke and ischemic stroke. The study concluded that in today’s society, the prevalence of stroke and the proportion of low PA are both high and increasing, and PA as a separate or additional therapy plays an important role in the treatment of stroke. This is consistent with the conclusion of this study. This study also believes that high PA is important for the prevention of stroke in middle-aged and elderly people. People should improve their awareness of PA and adhere to physical exercise.

In addition, our survey shows that the low level of PA is positively correlated with stroke, which means that the middle-aged and elderly people with low level of PA are more likely to have stroke. M Pang et al[24] have shown that aerobic exercise for 20 to 40 minutes and 3 to 5 days a week can help to enhance the aerobic fitness ability, walking speed and walking endurance of patients with mild to moderate stroke, and is considered to have low cardiovascular risk after appropriate screening and evaluation. M saltychev et al[25] studied that aerobic exercise can indeed improve the aerobic capacity of stroke survivors. The research showed that aerobic training can improve the aerobic capacity of stroke survivors and support the conventional suggestions of poststroke training. Yang HX et al[26] analyzed the effects of Tai Chi, Qigong, and modern exercise therapy on lower limb motor function in stroke patients. One hundred five stroke patients were divided into a control group (n = 35), a Qigong group (n = 36), and a Tai Chi group (n = 38). The results showed that compared with the control group, Tai Chi and Qigong had a more significant effect on improving lower limb motor function in stroke patients. Li Shuzhen et al.[27] Conducted a systematic evaluation to analyze the impact of Tai Chi exercise on balance function in stroke patients. Seven studies were included, with a total of 629 participants. Compared with conventional rehabilitation training, Tai Chi exercise and Tai Chi gait training have a positive impact on the Berg balance scale index. The conclusion is that Tai Chi exercise can improve the balance function of stroke patients, and its effect is superior to conventional rehabilitation training. However, more large-scale and carefully designed experiments are needed to confirm the superiority of Tai Chi exercise. Different forms of PA can have different effects on improving the physical health of stroke patients. Therefore, when formulating exercise prescription for elderly stroke patients, we should combine the health status of elderly stroke patients to formulate exercise prescription content suitable for their physical characteristics and high exercise intensity. Such exercise prescription is both safe and effective for the treatment of elderly stroke.

Several possible mechanisms of the relationship between PA and stroke have been proposed and tested. Impaired endothelial vasodilation is one of the risk factors for stroke.[28] PA can improve oxidative stress, reduce inflammation, and improve insulin resistance to improve vascular endothelial function, thereby reducing the risk of stroke.[29] Appropriate PA can improve or repair the damaged endothelial vasodilation function and reduce the risk of stroke.[30] Arteriosclerosis should also be considered as one of the risk factors for stroke in the elderly, as the increase in arteriosclerosis in the elderly leads to a decrease in arterial compliance and buffering ability against blood pressure.[31] Hypertension is an important component of various risk factors for cerebral infarction. Hypertension and arteriosclerosis can lead to an increase in pressure and flow velocity within the blood vessels, causing significant shear forces on the vessel wall, causing damage to the vascular intima, and also leading to vascular remodeling, including thickening of the intima, middle layer, and outer membrane, leading to increased stiffness and resistance of the vessel wall, and poor blood flow.[32] Hypertension and arteriosclerosis can make coagulation factors and platelets in the blood more prone to aggregation, leading to thrombosis and changes in brain structure, such as cerebral aneurysms and microaneurysms, which may increase the risk of stroke.[33] Appropriate PA can improve the symptoms of arteriosclerosis in the middle-aged and elderly, restore the arteries of the elderly to normal function, and then reduce the risk of stroke in the middle-aged and elderly.[34]Appropriate PA can improve or repair the function of the sympathetic nervous system, thereby restoring the body’s control over the normal function of the cardiovascular system, keeping the body’s heart rate and blood pressure within the normal range, and reducing the risk of stroke in the elderly.[35] The abnormal glucose metabolism and islet function of human body will increase the risk of stroke,[36] while physical exercise will improve the glucose metabolism and islet function of human body.[37] Physical exercise can further improve the regulation function of human body on blood pressure by improving the glucose metabolism and islet function, thereby reducing the risk of stroke.[38] PA can reduce the level of inflammation, reduce the damage of inflammation to blood vessels, improve antioxidant capacity, reduce the damage of oxidative stress to blood vessels, and reduce the risk of stroke.[39] PA can improve blood lipid metabolism, reduce cholesterol and triglyceride levels, reduce the formation of vascular plaque, enhance vascular elasticity, reduce the occurrence of vasoconstriction and sclerosis, and reduce the risk of stroke.[40] Therefore, PA can reduce the risk of stroke through a variety of mechanisms, including improving vascular endothelial function, reducing blood pressure, reducing the level of inflammation, improving antioxidant capacity, improving blood lipid metabolism and enhancing vascular elasticity, which provides an important reference for the treatment of stroke caused by different causes.

The results of our model also quantify the impact of demographic variables on the relationship between stroke and PA. Aging is one of the risk factors for stroke and low PA in the elderly.[41] Considering the influence of gender and age, this study found that with the increase of age, the risk of stroke in the middle-aged and elderly people became higher and higher, but the level of PA became lower and lower. A previous study found that the number of women who died of stroke was lower than that of men, but the age-specific incidence of women and men was similar under the age of 55. The incidence of men aged 55 to 75 was higher, and tended to be stable over the age of 75.[42] With the growth of age, the blood vessels of the human body gradually age and may be damaged. Such aging and damage may lead to vascular stenosis or hardening, affect the flow of blood, and the ability of the human body to control blood pressure and blood sugar may be weakened, and these problems will increase the risk of stroke.[43] Therefore, in order to reduce the risk of stroke, the elderly should pay attention to healthy diet, maintain proper exercise, control blood pressure, blood lipids and blood sugar, avoid smoking and excessive drinking, conduct regular health examination, and treat problems in time.

The results of this study found that middle-aged and elderly people with low educational level, poor health status (self-rated poor health status, disability, hyperlipidemia, memory disorders, arthritis, asthma), and poor walking ability are more likely to suffer from stroke. People with lower levels of education may be less knowledgeable about healthy lifestyles, such as healthy eating and regular exercise.[44] They may not be aware of the impact of risk factors such as unhealthy lifestyles on stroke. Low education level may affect people’s acquisition and understanding of knowledge about chronic disease management, such as hypertension, diabetes and high cholesterol.[44,45] These diseases are all associated with an increased risk of stroke.[37–40] People with lower levels of education may not know how to recognize the symptoms of stroke, or may not know how to seek immediate medical help, which can lead to delays in stroke and increase the risk of serious consequences. In many cases, people with lower levels of education may have difficulty accessing and understanding medical services, knowing how to obtain health insurance, or not knowing how to obtain necessary medical information. This is consistent with the conclusions of previous studies, which found that hypertension, diabetes, Hypercholesterolemia, heart disease and other diseases are the main risk factors of stroke.[46] Moreover, unhealthy lifestyle habits such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, lack of exercise, and unhealthy diet may increase the risk of stroke.[47] Other studies have found that long-term mental stress and depression may affect vascular health and increase the risk of stroke, but no significant association between negative emotions and depression and stroke was observed in this study. We should avoid these risk factors to reduce the risk of stroke, and it is recommended to provide health management plans for the elderly to prevent stroke. A previous study, similar to this 1, found a significant correlation between walking ability and stroke.[48] Walking is an important PA that can help burn calories, reduce weight, and improve cardiovascular function.[48] If elderly people have poor walking ability, they may lack sufficient exercise, which may increase the risk of obesity and other health problems, such as hypertension, heart disease, and high cholesterol, all of which are risk factors for stroke.[49] Poor walking ability may reflect more serious vascular problems, such as Arteriosclerosis, stenosis or thrombosis, which may lead to decreased blood flow and increased risk of stroke.[50] The poor walking ability of elderly people indicates a decrease in their cognitive function, which is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and may also increase the risk of stroke.[51] Therefore, for elderly people with poor walking ability, doctors may suggest taking more proactive measures to improve their health, such as increasing PA, managing blood pressure and cholesterol, and conducting cognitive training.

5. Conclusion and limitations

The level of PA among middle-aged and elderly people is closely related to their stroke status, but research on PA and stroke status among middle-aged and elderly people in China is currently in its infancy. In this study, middle-aged and elderly people with high levels of PA had a significantly lower risk of stroke compared to those with low levels of PA. At the same time, middle-aged and elderly people with low educational level, poor self-evaluation of health status, disabilities, hyperlipidemia, memory disorders, arthritis, asthma, and walking 1 kilometer difference are more likely to suffer from stroke symptoms. This study helps to better understand the relationship between stroke symptoms and PA in middle-aged and elderly people, and provides a new basis for formulating scientific and effective Exercise prescription to prevent and treat stroke symptoms in middle-aged and elderly people.

Some limitations have also affected our research. First, after adjusting the population characteristics and variables related to physical and mental health, this study only revealed the relationship between PA and stroke. It also establishes a relationship between PA levels and stroke. We found that the potential mechanism of sports activities affecting stroke includes improving damaged endothelial and cardiac function, arteriosclerosis and sympathetic nervous system dysfunction. In future research, it is necessary to further explore whether there is information about other potential mechanisms by which PA affects stroke. Secondly, we have proved that there is a correlation between the level of PA and stroke in the middle-aged and elderly in China. We need to expand the sample size of the survey, and further explore the relationship between sports activities and stroke in China, in order to determine the validity of this research conclusion, because there may be regional differences in the correlation between sports activities and stroke. Third, the participants in this study did not include the middle-aged and elderly people outside China. It is necessary to further explore the ethnic and regional differences in the relationship between sports activities and stroke among the middle-aged and elderly people in other countries and China.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants in CHARLS team for their time and effort devoted to the project.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xin Jiang.

Data curation: Xin Jiang.

Funding acquisition: Xin Jiang.

Investigation: Yaqun Zhang, Xin Jiang.

Methodology: Yaqun Zhang, Xin Jiang.

Software: Xin Jiang.

Writing – original draft: Yaqun Zhang, Xin Jiang.

Writing – review & editing: Yaqun Zhang, Xin Jiang.

Abbreviations:

- CHARLS

- China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- PA

- physical activity

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This study was supported by the 2023 Basic Research Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (JYTQN2023426), the 2024 Liaoning Provincial Economic and Social Development Research Project (2024lslqnkt-043), and the 2023 Anshan City Philosophy and Social Science Research Project (as20232041).

How to cite this article: Zhang Y, Jiang X. The relationship between physical activity and stroke in middle-aged and elderly people after controlling demography variables, health status and lifestyle variables. Medicine 2023;102:50(e36646).

References

- [1].Chan SH, Pan Y, Xu Y, et al. Life satisfaction of 511 elderly Chinese stroke survivors: moderating roles of social functioning and depression in a quality of life model. Clin Rehabil. 2020;35:269215520956908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Honglian W, Mingcan W, Qingfen T, et al. Risk factors for stroke in a population of central China: A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2022;101:e31946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mayman NA, Tuhrim S, Jette N, et al. Sex differences in post-stroke depression in the elderly. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30:105948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zheng X, Wang H, Bian X. Clinical correlation analysis of complications in elderly patients with sequelae of stroke with different barthel index in Tianjin emergency department. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [5].Schfer SK, Fleischmann R, Sarnowski BV, et al. Relationship between trajectories of post-stroke disability and self-rated health (neuro adapt): protocol for a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2021:e049944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Su CC, Yang YHK, Lai CC, et al. Comparative safety of antipsychotic medications in elderly stroke survivors: a nationwide claim data and stroke registry linkage cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;139(S1):159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tan J, Ramazanu S, Liaw SY, et al. Effectiveness of public education campaigns for stroke symptom recognition and response in non-elderly adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;31:106207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Huang J, Liu L, Yu-Ling C, et al. Relationship between body mass index and ischaemic stroke in Chinese elderly hypertensive patients. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nair S, Chen S, Gupta D, et al. Higher BMI confers a long-term functional status advantage in elderly New Zealand European Stroke Patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30:105711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim Y, Krause T, Lee S, et al. Population-wide trends in age-specific utilization of endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2021;52(Suppl_1):226. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lekoubou A, Wu EY, Bishu KG, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and prognosis of mortality among elderly stroke patients with convulsive status epilepticus in the United States. J Neurol Sci. 2022;440:120342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Woodford S, Avolio A, Butlin M. Noninvasive measurements of normal values of stroke volume and total peripheral resistance in an elderly population accounting for age and sex differences. J Hypertens. 2021;39(Supplement 1):e280. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Amidei CB, Trevisan C, Dotto M, et al. Association of physical activity trajectories with major cardiovascular diseases in elderly people. Heart. 2022;108: 360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Martins JC, Aguiar LT, Nadeau S, et al. Measurement properties of self-report physical activity assessment tools in stroke: a protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jayawardana KS, Gary C, Heidi J, et al. Comparing the physical activity of stroke survivors in high-income countries and low to middle-income countries. Physiother Res Int. 2022;6:e1918.DOI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Luisa SM, Siscovick DS, Psaty BM, et al. Physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Circulation. 2019;133:147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sai SA, Mohanraj KG. Knowledge, awareness, prevalence and frequency of daily physical activity and its association with stroke in young adult population. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2020;11(SPL3):507–13. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yuan J, Ding Y, Zhao W. The application effect of quantitative physical exercise combined with personalized nutrition intervention in pregnant women with diabetes. Integrated Tradit Chin Western Med Nurs. 2022;8:103–5. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhao Y, Strauss J, Chen X, et al. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Wave 4 User’s Guide, National School of Development, Peking University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Van d PHP, Tudor-Locke C, Marshall AL, et al. Reliability and validity of the international physical activity questionnaire for assessing walking. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2010;81:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Macfarlane D, Chan A, Cerin E. Examining the validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, long form (IPAQ-LC). Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].MacDonald CJ, Madika AL, Gomes R, et al. Physical activity and stroke among women - a non-linear relationship. Prev Med. 2021;150:106485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hu Frank B. Physical activity and risk of stroke in women. JAMA. 2010;283:2961–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pang M, Charlesworth S, Lau R, et al. Using aerobic exercise to improve health outcomes and quality of life in stroke: evidence-based exercise prescription recommendations. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Saltychev M, Sjogren M, Barlund E, et al. Do aerobic exercises really improve aerobic capacity of stroke survivors? A systematic review and metaanalysis. Euro J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;2:233–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yang HX, Liu XL. The effect of Tai Chi and Baduanjin on motor function and surface electromyography of lower limbs in stroke patients with hemiplegia. Chin Rehabilitation Theory Pract. 2019;25:101–6. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shuzhen L, Zheng G, Wang Y, et al. Effect of tai chi exercise on balance function of patients with stroke:a systematic review. Rehabilitation Med. 2016;26:57. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Thanassoulis G, Lyass A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Relations of exercise blood pressure response to cardiovascular risk factors and vascular function in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2012;125:2836–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tzemos N, Lim PO, Mackenzie IS, et al. Exaggerated exercise blood pressure response and future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17:837–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ozkor MA, Hayek SS, Rahman AM, et al. Contribution of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor to exerciseinduced vasodilation in health and hypercholesterolemia. Vasc Med. 2015;20:14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kim D, Ha JW. Hypertensive response to exercise: mechanisms and clinical implication. Clin Hypertension. 2016;22:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Borges JP, Mendes F, Rangel M, et al. Exercise training improves microvascular function in patients with Chagas heart disease: data from the PEACH study. Microvasc Res. 2021;134(Suppl. 1):e104106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Morris JH., Oliver T, Thilo K, et al. Physical activity participation in community dwelling stroke survivors: synergy and dissonance between motivation and capability a qualitative study. Physiotherapy. 2017;103:311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Honda H, Igaki M, Komatsu M, et al. Stair climbing–descending exercise following meals improves 24-hour glucose excursions in people with type 2 diabetes. J Phys Fitness Sports Med. 2021;10:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhong C, Voutsinas J, Willey J, et al. Physical activity, hormone therapy use, and stroke risk among women in the California teachers study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2020;54:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Aguiar LT, Nadeau S, Britto RR, et al. Effects of aerobic training on physical activity in people with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Neuro Rehabilitation. 2020;46:391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hall C, Heck JE, Sandler DP, et al. Occupational and leisure-time physical activity differentially predict 6-year incidence of stroke and transient ischemic attack in women. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2018;45:267–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Olsson OA, Persson HC, Alt Murphy M, et al. Early prediction of physical activity level 1 year after stroke: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Preston E, Dean CM, Ada L, et al. Promoting physical activity after stroke via self-management: a feasibility study. Taylor & Francis;2017:e1304876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ezeugwu VE, Manns PJ. Sleep duration, sedentary behavior, physical activity, and quality of life after inpatient stroke rehabilitation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:2004–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hatakeyama K, Seposo X. Heatstroke-related ambulance dispatch risk before and during COVID-19 pandemic: subgroup analysis by age, severity, and incident place. Sci Total Environ. 2022;821:e153310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Feigin VL, Nguyen G, Cercy K, et al. Global, regional, and country-specific lifetime risks of stroke, 1990 and 2016. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kansagra AP, Goyal MS, Hamilton S, et al. Stroke imaging utilization according to age and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology. 2021;300:E342–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rist PM, Buring JE, Kase CS, et al. healthy lifestyle and functional outcomes from stroke in women. Am J Med. 2016;129:715–724.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dharma KK., Parellangi. Use of mobile-stroke risk scale and lifestyle guidance promote healthy lifestyles and decrease stroke risk factors. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7:401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Larsson SC, Akesson A, Wolk A. Primary prevention of stroke by a healthy lifestyle in a high-risk group. Neurology. 2015;84:2224–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jonsson AC, Delavaran H, Lovkvist H, et al. Secondary prevention and lifestyle indices after stroke in a long-term perspective. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;138:227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mudge S, Stott NS. Outcome measures to assess walking ability following stroke: a systematic review of the literature. Physiotherapy. 2007;93:189–200. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kuys S, Brauer S, Ada L. Routine physiotherapy does not induce a cardiorespiratory training effect post-stroke, regardless of walking ability. Physiother Res Int. 2010;11:219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Langhammer B, Lindmark B, Stanghelle JK. Baseline walking ability as an indicator of overall walking ability and ADL at 3, 6, and 12 months after acute stroke. Eur J Physiother. 2021;24:311–9. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Murata S, Takegami M, Ogata S, et al. Joint effect of cognitive decline and walking ability on incidence of wandering behavior in older adults with dementia: a cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]